Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. Brown Opinion

Public Court Documents

March 7, 1968

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. Brown Opinion, 1968. b53764f5-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/07a09362-9351-4d4a-a43b-1405bb012c45/commonwealth-of-pennsylvania-v-brown-opinion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

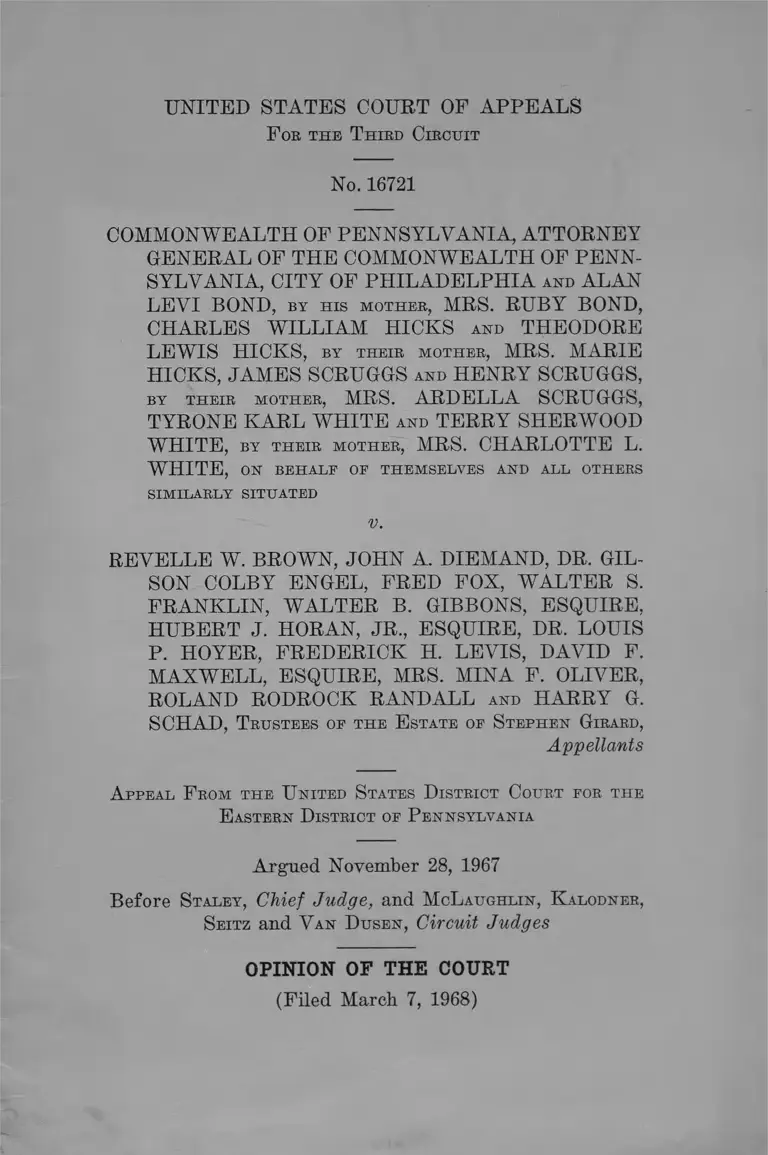

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

F oe t h e T h ird C ir c u it

No. 16721

COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA, ATTORNEY

GENERAL OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF PENN

SYLVANIA, CITY OF PHILADELPHIA and ALAN

LEVI BOND, b y h is m o t h e r , MRS. RUBY BOND,

CHARLES WILLIAM HICKS and THEODORE

LEWIS HICKS, BY THEIR MOTHER, MRS. MARIE

HICKS, JAMES SCRUGGS and HENRY SCRUGGS,

BY t h e ir m o t h e r , MRS. ARDELLA SCRUGGS,

TYRONE KARL WHITE and TERRY SHERWOOD

WHITE, by t h e ir m o t h e r , MRS. CHARLOTTE L.

WHITE, ON be h alf of th em selves and a l l others

SIMILARLY SITUATED

V.

REVELLE W. BROWN, JOHN A. DIEMAND, DR. GIL

SON COLBY ENGEL, FRED FOX, WALTER S.

FRANKLIN, WALTER B. GIBBONS, ESQUIRE,

HUBERT J. HORAN, JR., ESQUIRE, DR. LOUIS

P. HOYER, FREDERICK H. LEVIS, DAVID F.

MAXWELL, ESQUIRE, MRS. MINA F. OLIVER,

ROLAND RODROCK RANDALL and HARRY G.

SCHAD, T rustees of t h e E state of S t e p h e n G irard ,

Appellants

A ppea l F rom t h e U nited S tates D istrict C ourt for t h e

E astern D istrict of P e n n sy lv an ia

Argued November 28, 1967

Before S ta le y , Chief Judge, and M cL a u g h lin , K alodner ,

S eitz and V an D u s e n , Circuit Judges

OPINION OF THE COURT

(Filed March 7, 1968)

2

By M cL a u g h l in , Circuit Judge.

The problem here arises from the will of Stephen

Girard, a Philadelphia, Pennsylvania resident who died in

1831. In his will, dated 1830, he laid down his fundamental

thesis that he had “ been for a long time impressed with the

importance of educating the poor, and of placing them by

the early cultivation of their minds and the development

of their moral principles, above the many temptations, to

which, through poverty and ignorance they are exposed;

* * Continuing, he said “ * * * I am particularly de

sirous to provide for such a number of poor male white or

phan children, as can be trained in one institution, a better

education as well as a more comfortable maintenance than

they usually receive from the application of public funds.”

He coupled this with his statement of heartfelt interest in

the welfare of Philadelphia and his desire to improve it in

its Delaware River neighborhood for the benefit of the health

of its citizens and so that the eastern part of the city would

correspond better with the interior. So inter alia he left the

valuable residue and remainder of his real and personal

property to “ The Mayor, Aldermen and citizens of Phila

delphia, their successors and assigns in trust to and for the

several uses intents and purposes hereinafter mentioned

and declared * * The will went into considerable par

ticulars regarding the Girard Philadelphia and Kentucky

property. Concerning a personal estate bequest of two

million dollars for the College the will outlined at length

where it would be located and in great detail the exact con

struction of the College and outbuildings, etc. The will also

gave five hundred thousand dollars to Philadelphia for

various public improvements. The Commonwealth of Penn

sylvania was bequeathed three hundred thousand dollars

for internal improvement by canal navigation. This last

bequest was conditioned upon the Commonwealth passing

certain laws helpful to the testator’s contemplated improve

ment of Philadelphia and for the desired objectives of

3

Girard College. All the suggested assisting legislation was

enacted by the Commonwealth in due course.

Mr. Girard stated specifically in his will:

“ In relation to the organization of the college and

its appendages, I leave, necessarily, many details to the

Mayor, Aldermen and citizens of Philadelphia and their

successors; and I do so, with the more confidence, as,

from the nature of my bequests and the benefit to re

sult from them, I trust that my fellow citizens of Phila

delphia, will observe and evince especial care and

anxiety in selecting members of their City Councils,

and other agents * * V ’

He provided that the College accounts be kept sepa

rately so that they could be examined by a committee of the

Pennsylvania legislature and that an account of same be

rendered annually to said legislature together with a report

of the state of the College. Philadelphia accepted the be

quests and by ordinance set up a plan to administer the

College by a Trusts Board. In 1833 a building committee

of the City Council was appointed, a president of the Col

lege was chosen under an ordinance created for that pur

pose and the cornerstone of the main building laid. Con

struction was concluded in 1847 and the College opened the

first of the following year. Down to 1869 the City Council

operated the College directly, first by way of the trustees

until 1851 when the latter offices were abolished, and the

Council again took over direct management. In 1869 the

Commonwealth enacted a law which gave Philadelphia a

local Board of Trusts to take over the control of Girard

College. From that date the Board of City Trusts remained

in charge of the College until 1958. Broadly summing up

the Commonwealth and City’s intimate association with

Girard College the District Court, with full justification in

the record, found as fact that:

“ Beginning in 1831 and continuing to date, the

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and the City of Phi la-

4

delphia, by the enactment of statutes and ordinances,

by the use and supervision of public officials, appointed

by legislative and judicial bodies, by rendering services

and providing tax exemptions, perpetual existence and

exemption from tort liability, have given aid, assistance,

direction and involvement to the construction, mainte

nance, operation and policies of Girard College.”

It is important to note in this sequence that Philadel

phia has made a consistently brilliant showing through the

years in its management of the funds and real property

from the Girard estate for the College. The money bequest

amounted to six million dollars. This was increased to

ninety million dollars plus by 1959. The various estate

properties given the City for the College were not allocated

any book value by the estate. These have insurable value

at this time of $42,000,000.

In 1954 two applicants requested admission to the Col

lege. They were fully qualified but were refused because

they were Negroes. They brought their cause to the United

States Supreme Court which held in that suit, titled Penn

sylvania, et al. v. Board of Directors of the City of Phila

delphia, 353 U.S. 230, 231 (1958):

“ The Board which operates Girard College is an

agency of the State of Pennsylvania. Therefore, even

though the Board was acting as a trustee, its refusal

to admit Foust and Felder to the college because they

were Negroes was discrimination by the State. Such

discrimination is forbidden by the Fourteenth Amend

ment. Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483.

Accordingly, the judgment of the Supreme Court of

Pennsylvania is reversed and the cause is remanded

for further proceedings not inconsistent with this

opinion. ’ ’

The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania on remand took

none of the plainly indicated proceedings called for by

the United States Supreme Court. It simply remanded

the litigation to the Orphans’ Court of Philadelphia

5

County.1 That court, without notice or opportunity for

the plaintiffs to do anything and with no request from the

City or other source whatsoever, on its own initiative ousted

Philadelphia as trustee and installed in place of the City

Board, persons of its own choosing. There is disagree

ment between the parties with respect to the method used

for the selection of the new trustees. But it is conceded by

appellants regarding prior notification by the Orphans’

Court to its choices that, “ Certainly no court would ap

point an individual to a position of such responsibility with

out first affording him an opportunity to refuse.” The

record does show clearly that one of the court trustees tes

tified that he was telephoned by one of the Orphans’ Court

judges prior to the appointments order being filed and told

that the court had appointed its own trustees of which

he was one. It is also in the record that the new trustees,

as stated by one of them, were sworn in by at least one of

the Orphans’ Court judges and that included in their oath

was “ * * * that we would undertake to manage the will

of Stephen Girard in accordance with the way it was writ

ten.” The said trustee, referring to that part of the oath,

further mentioned ‘ ‘ That is what we all assumed anyhow. ’ ’

We think the foregoing factual narrative demonstrates

that the Orphans’ Court of Philadelphia County has been

substantially involved with the supervision of the Girard

Estate.

The Philadelphia City Trustees took no appeal from

their ouster. The children plaintiffs did. The Pennsyl

vania Supreme Court found that the Orphans ’ Court action

1 As rightly found by the District Court:

“ In 1959, after the decision of the United States Supreme Court in

Pennsylvania v. Board of Directors, 353 U.S. 230 (1957), the Legislature

of Pennsylvania enacted a statute granting the Orphans’ Court the power

and the duty to appoint substitute trustees for the property of minors,

when a previous trustee which was a political subdivision is removed ‘in

the public interest,’ and authorized a substitute trustee to invest such

property of minors committed to their custody. The Act also contained

other enabling legislation, without which the present defendants would

be unable to carry out their duties. Act of November 19, 1959, P.L. 1526

(Exh. P-51 (1 0 )) . The Legislature Journal of the Senate of the Com

monwealth of Pennsylvania shows that this statute was passed specifically

as enabling legislation in aid of Girard College (Exh. P-51 (1 0 ) ) .”

6

was not inconsistent with the mandate of the United States

Supreme Court or the Fourteenth Amendment or the

Girard will. Application for certiorari was denied by the

United States Supreme Court, 357 U.S. 570 (1958).

The present litigation was instituted in the United

States District Court for the Eastern District of Penn

sylvania. The trial judge originally passed solely upon

the question of whether Girard College was within the

jurisdiction of the Pennsylvania Public Accommodations

Act of June 11, 1935, P.L. 297, as amended by the Act of

June 24, 1939, P.L. 872. The Court held it was within

Sections (a) and (c) of the Act and not within the proviso

of Section (d). This Court reversed that finding and re

turned the suit to the District Court for trial on the merits

of Count 1 of the complaint which charges that “ The refu

sal of the trustees of Girard College to admit applicants

without regard to race violates the Constitution of the

United States of America and applicable Federal statutes.”

Appellants argue that they have not violated the equal

protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment by deny

ing admission to individuals because of their color. In

support of this they cite some Pennsylvania decisions in

cluding the State Supreme Court Girard College opinion

on the remand of the United States Supreme Court to that

State Court “ for further proceedings not inconsistent with

this opinion.” What the State Court did was turn the

matter over to its Orphans’ Court which eliminated the

City as trustee and installed its own group, sworn to up

hold the literal language of the Girard will, a move.effec

tively continuing the very segregation which had been con

demned by the United States Supreme Court. True, the

latter had denied the application for certiorari. Times

without number that Court has plainly ruled that there is

no inference permissible from its denial of application

for certiorari, favorable or unfavorable to either side of a

litigation. Certainly in the whole muddy situation flowing

from the State excision of the City Board, thereby taking

7

away the linchpin of the Girard will, the then existing state

litigation picture did not bring into the necessary sharp

focus, the set piece maneuver which had completely circum

vented the Supreme Court’s directive. We, however, as

above seen, do have all of that amazing effort to maintain

Girard’s discriminatory status before us in its true perspec

tive.

Even in the above short resume of the conception,

creation and functioning of Girard College, the close, in

dispensable relationship between the College, the City of

Philadelphia and the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in

tended by Mr. Girard, meticulously set out in his will and

faithfully followed for one hundred and twenty-seven years

is self evident.2 The ironic result of the removal of the

City Trustees is that Pennsylvania’s involvement with

Girard College is far more powerful than was provided

for by Mr. Girard. The Commonwealth’s Orphans’ Court,

through its assumed power of appointment and reappoint

ment of the Trustees, is significantly concerned with the

current administration of the college.

On the whole vital Commonwealth and City relation

ship to Girard College shown we must agree with Judge

Lord in the District Court, that the facts in Evans v.

Newton, 382 TJ.S. 296, 301, 302 (1966) are fairly comparable

to those in this appeal and that the decision of the Supreme

Court therein governs the issue before us. In Evans a

tract of land was willed to the Mayor and City Council of

Macon, Georgia, as a park for white people, to be con

trolled by a white Board of Managers. The city desegre

gated the park and the managers thereafter sued the city

and the trustees of the residuary beneficiaries, asking for

the city’s removal as trustee and the appointment of private

trustees to enforce the racial limitations of the will. The

2 So that there will be no possible cause for confusion, we note that the

general topic of the sanctity of wills is not before us. Our total concern in

this cause to which our decision is confined is a will in which the testator has

deliberately and specially involved the State in the designated use of his testa

mentary property.

8

Court accepted the city’s resignation and appointed three

new trustees. The State Supreme Court upheld the terms

of the will and the appointment of the new trustees. The

United States Supreme Court reversed. Mr. Justice

Douglas for the Court in the opinion said as to the park in

issue:

‘ ‘ The momentum it acquired as a public facility is cer

tainly not dissipated ipso facto by the appointment of

‘ private’ trustees. So far as this record shows, there

has been no change in municipal maintenance and con

cern over this facility. Whether these public character

istics will in time be dissipated is wholly conjectural.

If the municipality remains entwined in the manage

ment or control of the park, it remains subject to the

restraints of the Fourteenth Amendment * * *.

# # #

“ Under the circumstances of this case, we cannot

but conclude that the public character of this park re

quires that it he treated as a public institution subject

to the command of the Fourteenth Amendment, regard

less of who now has title a ruler state law. We may

fairly assume that had the Georgia courts been of the

view that even in private hands the park may not he

operated for the public on a segregated basis, the resig

nation would not have been approved and private

trustees appointed. We put the matter that way be

cause on this record we cannot say that the transfer of

title per se disentangled the park from segregation

under the municipal regime that long controlled it. ’ ’

We think also that the Supreme Court’s landmark de

cision in Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1, 20 (1948) surely

points to the affirmance of the instant judgment in accord

ance with the justice which must be done in this case. The

state courts in Shelley had enforced restrictive real estate

agreements. The Court by Chief Justice Vinson held:

9

“ We hold that in granting judicial enforcement of

the restrictive agreements in these cases, the States

have denied petitioners the equal protection of the laws

and that, therefore, the action of the state courts can

not stand. We have noted that freedom from discrimi

nation by the States in the enjoyment of property

rights was among the basic objectives sought to be

effectuated by the framers of the Fourteenth Amend

ment. That such discrimination has occurred in these

cases is clear. Because of the race or color of these

petitioners they have been denied rights of ownership

or occnpancy enjoyed as a matter of course by other

citizens of different race or color.

* * *

“ The historical context in which the Fourteenth

Amendment became a part of the Constitution should

not be forgotten. Whatever else the framers sought

to achieve, it is clear that the matter of primary con

cern was the establishment of equality in the enjoyment

of basic civil and political rights and the preservation

of those rights from discriminatory action on the part

of the States based on considerations of race or color.”

See also Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249 (1953) and

Sweet Briar Institute v. Button, 12 Race Rel. L. Rep. 85

(W.D. Va., 1967), rev’d per curiam, 387 U.S. 423, decision

on the merits, Civil No. 66-C-10-L (W.D. Va., filed July 14,

1967). In Sweet Briar the trustees of the Institute sought

to enjoin enforcement by the state attorney general of a

racial restriction contained in the will establishing and

funding the college. On motion of the defendant, the three

judge Court abstained until such time as the college carried

its prior case through the state courts. The Supreme Court

reversed, stressing strongly, Section 202 of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 200a-l (1964), and ordered the

District Court to determine the case on the merits. On re

mand, that Court entered a permanent injunction against

10

enforcement of the racial restriction by the State of Vir

ginia, holding that:

“ The State cannot require compliance with the testa

mentary restriction because that would constitute State

action barred by the Fourteenth Amendment. This

was the express holding in the Girard Case.”

F.Supp. (W.D. Va., 1967).

Girard’s definitive position in this period of more than

ever being operated by an agency of the state does not

simply emanate from the momentum of the Commonwealth

and City legitimate participation in the establishment of

Girard and its institutional life from its beginning to the

present moment. It is in addition, as we hold, the obvious

net consequence of the displacement of the City Board by

the Commonwealth’s agent and the filling of the Girard

Trusteeships with persons selected by the Commonwealth

and committed to upholding the letter of the will. Those

radical changes pushed the College right back into its old

and ugly unconstitutional position. Had the City Trustees

been left undisturbed it is inconceivable that this bitter dis

pute before us would not have been long ago lawfully and

justly terminated. It is inconceivable that those City Trus

tees would not have with goodwill opened the College to all

qualified children. Given everything we know of Mr.

Girard, it is inconceivable that in this changed world he

would not be quietly happy that his cherished project had

raised its sights with the times and joyfully recognized that

all human beings are created equal.

We do not consider the move of the state court in dis

posing of the City Trustees and installing its own appointees

to be a non obvious involvement of the State as mentioned

in the test outlined in Burton v. Wilmington Parking Au

thority, 365 U.S. 715, 722 (1961). The action in this in

stance and its motivation are to put it mildly, conspicuous.

And what happened to Girard does “ * * # significantly en

courage and involve the State in private discriminations.”

Reitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369, 381 (1967). As the Court

11

there said by Mr. Justice White, “ We have been presented

with no persuasive considerations indicating that this judg

ment should be overturned. ’ ’

The judgment of the District Court will be affirmed.

K alodnek , Circuit Judge, concurring in the result.

I would affirm the Decree of the District Court on the

ground that the removal in 1957 of the Board of Directors of

City Trusts as trustee of the Stephen Girard Estate by the

Orphans ’ Court, and its appointment of substituted indivi

dual trustees, for the avowed purpose of carrying out the

racial exclusionary clause of Girard’s Will, contravened the

Fourteenth Amendment of the United States under the doc

trine of Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948) and its

progeny.1

The Fourteenth Amendment is contravened under the

Shelley doctrine, where there is “ active intervention of the

state courts, supported by the full panoply of state power ’ ’ 2

in the furtherance of enforcement of restrictions denying

citizens their civil rights because of their race, color or

creed.

In the instant case, the Orphans’ Court had two alter

native courses of action following the ruling of the Supreme

Court of the United States in Pennsylvania v. Board of

Directors of City Trusts, 353 U.S. 230 (1957), that the

Board’s denial of admission to Girard College of negro male

orphans pursuant to the racial exclusionary clause of

Stephen Girard’s Will constituted state action in violation

of the Fourteenth Amendment.__________________________

1 Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249 (1953).

2 Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 at page 19. A t page 14 of Shelley the

Court said:

“That the action of state courts and judicial officers in their official

capacities is to be regarded as action of the State within the meaning of

the Fourteenth Amendment, is a proposition which has long been estab

lished by decisions of this Court. . . . In E x Parte Virginia, 100 U.S. 339,

347 (1880), the Court observed: ‘A State acts by its legislative, its execu

tive, or. its judicial authorities. It can act in no other way.’ ”

12

The Orphans ’ Court could have pursued the alternative

of directing the Board of Directors of City Trusts to admit

negro orphans to Girard College. Instead, it sua sponte

pursued the alternative course of removing the Board and

appointing individual private trustees in its stead so as to

permit continuance of the discriminatory admission policy

dictated by Girard’s Will.3

That the alternative action taken by the Orphans ’ Court

was for the avowed purpose of giving effect to the racial

exclusionary clause of Girard’s Will is explicitly spelled out

in the Orphans’ Court opinion accompanying its Decree of

September 11, 1957 which removed the Board of Directors

of City Trusts as trustee of the Girard Estate, “ effective

upon the appointment of a substituted trustee by this

court.” 4

In this opinion, Girard’s Estate, 7 Pa. Fiduc. Rep. 555,

(1957), the Orphans’ Court said at pages 557-558:

“ The Supreme Court of the United States has

ruled, as a matter of federal constitutional law, that

the Board of Directors of City Trusts of the City of

Philadelphia is an agency of the State of Pennsylvania

and consequently forbidden by the Fourteenth Amend

ment from operating, even as a trustee of private funds,

an establishment which excludes all but “ poor white

male orphans.”

# # #

“ The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, which is the

final arbiter of our state law, has unequivocally stated

that if, for any reason, the Board of Directors of City

Trusts of the City of Philadelphia cannot continue to

3 The Orphans’ Court in pursuing this alternative course acted in con

formity with the holding of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, in Girard Will

Case, 386 Pa. 548, 566 (1956) that should the Supreme Court of the United

States hold, as it later did, that the Board of Directors of City Trusts could

not carry out the exclusionary policy of Girard’s Will, that the Orphans’ Court

could then appoint another trustee who could do so.

4 The Orphans’ Court Decree of October 4, 1957, substituting thirteen

private citizens as Trustees of the Stephen Girard Estate, is reported at 7 Pa.

Fiduc. Rep. 606.

13

administer the trust in. accordance with testator’s direc

tions, it becomes the duty of this court to remove it as

trustee and to appoint a substituted trustee which can

lawfully administer the trust in the manner prescribed

by the testator.

* # *

“ In order to harmonize the opinions of the United

States Supreme Court and the Supreme Court of Penn

sylvania, we hold: (1) that the primary purpose of the

testator to benefit “ poor white male orphans,” only,

must prevail; and (2) that the disqualification of the

Board as trustee of this estate by the United States

Supreme Court requires us to remove it from the ad

ministration of the trust and to appoint a substituted

trustee, not so disqualified.” (emphasis supplied)

The Supreme Court of the United States has recently

ruled that in examining the constitutionality of a state act

the reviewing court (1) must consider the act “ in terms of

its ‘ immediate objective’, its ‘ ultimate effect’ and its ‘ his

torical context and the conditions existing prior to its en

actment’ ” ,5 6 and, (2) must “ assess the potential impact of

official action in determining whether the State has signi

ficantly involved itself with invidious discriminations” .6

The stated rule is, of course, applicable to the action

of a state court.

Applying the principles above stated to the instant

case, I am of the opinion that the Orphans ’ Court ‘ ‘ signifi

cantly involved itself with invidious discriminations” when

it removed the Board of Directors of City Trusts and ap

pointed individual trustees of the Estate of Stephen Girard

for the express purpose of effectuating the racial exclu

sionary clause in Girard’s Will, and thereby brought itself

within the ambit of the Shelley doctrine.

As the Shelley case said at page 18:

5 Reitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369 (1967) at page 373.

6 Id. at page 380.

14

“ . . . it has never been suggested that state court

action is immunized from the operation of those pro

visions [14th Amendment] simply because the action is

that of the judicial branch of the state government.”

For the reasons stated I would confine the scope of our

affirmance of the District Court’s Decree to the ground as

signed at the outset of this concurring opinion.

Van Dusekt, Circuit Jridge, concurring:

I concur in the result reached by the majority opinion,

but respectfully dissent from much of the language used.

Specifically, I disagree with the implication from the

statements that the state courts in 1957 installed their own

group of trustees “ sworn to uphold the literal language

of the Girard will” (and similar phrases). Such charac

terizations given to the actions of the Pennsylvania courts

by the majority opinion seem to me unnecessary to the

proper decision in this appeal. There is no necessary basis

in this record to so criticize either the able Pennsylvania

judges, who have so conscientiously handled the litigation

arising from the Girard Trust, or the distinguished and

dedicated trustees, who have contributed unselfishly so

much to this important charitable enterprise, acting’ under

the advice of their able counsel, for many years. This

appeal is being decided on the basis of the present decisions

of the United States Supreme Court in a field where the

“ federal role” is more “ pervasive” and “ intense” today

than it was several years ago. United States v. Price, 383

U.S. 787, 806 (1966). Recent decisions of the Supreme

Court, particularly in light of forceful dissents by Mr.

Justice Harlan, make clear that the Fourteenth Amend

ment does not now permit the discriminatory operation of

a charity like Girard College if the operation of that dis

crimination receives support from certain types of “ state

action. ’ ’

15

Of the forms or types of “ state action” in aid of dis

crimination that the Supreme Court has held render the

discrimination unconstitutional, that in Reitman v. Mulkey,

387 U.S. 369 (1967), seems most clearly apposite to the

facts of this case.

The decision of the United States Supreme Court in

1957 (353 U.S. 230) settled the question of whether the

discrimination at Girard College was then unconstitutional

state action. The same discrimination exists today and

this appeal asks whether the unconstitutionality also re

mains because prohibited state action supports the discrim

ination. The answer is yes. When the Orphans’ Court, on

its own motion and without formal hearing, removed the

Board of Directors of City Trusts and appointed “ private”

trustees in their place, such affirmative state action con

stituted the “ encouragement” of discrimination held to

violate the Fourteenth Amendment in Reitman v. Mulkey,

swpra, at 376. The state did not make itself merely neutral.

Just as the California court did in Reitman v. Mulkey, this

court can examine the constitutionality of such state action

“ in terms of its ‘ immediate objective,’ its ‘ ultimate effect’

and its ‘historical context and the conditions existing prior

to its enactment,’ ” 387 U.S. at 373. Cf. Burton v. Wil

mington Pkg. Auth., 365 U.S. 715, 722 (1961). The record

of the discrimination at Girard College after the 1957

United States Supreme Court decision makes it clear that

the further “ state actions” of the Pennsylvania courts did

not “ cure” the unconstitutionality, but perpetuated it by

affirmatively encouraging continued discrimination. With

hindsight it is clear that no reason exists for the deviation

from Girard’s will to appointing private trustees, except

for its allowing compliance with the “ white orphans” pro

vision. And it is likewise an inescapable conclusion that

the substitution of trustees in 1957 encouraged compliance

with the “ white” provision that has lasted for over 10

years. The state action that continues today in the Or

phans’ Court-trustee relationship is the “ encouragement”

16

of discrimination first given by the original appointment

of the individual trustees.

Even clearer state action of “ encouragement” is found

in the statute passed by the Pennsylvania Legislature after

the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania approved the substitu

tion of private trustees. The Act of November 19, 1959,

P.L. 1526, authorized ex post facto the Orphans’ Courts’

actions, and further implemented the change-over by fully

empowering the new private trustees to serve in place of

the Board of City Trusts as guardians of the boys attend

ing Girard College and to set up a common trust fund for

their property. The same Act also repealed several prior

laws passed to aid Girard College. Such affirmative legis

lative action, as an attempt to render a state neutral with

respect to otherwise unconstitutional discrimination, makes

Reitman v. Mulkey still more apposite.

When Stephen Girard deliberately and pointedly chose

to involve the State in the “ private” charitable conduct

of his school (as was decided at 353 U.S. 230), he ran the

risk that Philadelphia might not accept the trust, or might

be unable to administer it, or might be subsequently unable

to act because the federal constitution was changed (as

occurred when the Fourteenth Amendment was passed).

It is in this unique situation of a testator ’s deliberate pro

vision for a major role for the state in his charitable

scheme, that the action of the state courts rises to the level

of unconstitutional state action. The charitable scheme

chosen by Girard might as easily have become invalid due

to a change in the rule against perpetuities or some other

limitation imposed by society on the unlimited rights of

private property at death. See Commonwealth of Pennsyl

vania v. Broivn, 260 F. Supp. 323, 357 (E.D. Pa. 1966).

A True Copy:

Teste :

Clerk of the United States Court of Appeals

lor the Third Circuit.