Bakke v. Regents Brief of Amius Curiae for the National Urban League and Others

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1976

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bakke v. Regents Brief of Amius Curiae for the National Urban League and Others, 1976. fca5b153-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0869d670-3042-431a-bb8b-7ecc32c1d920/bakke-v-regents-brief-of-amius-curiae-for-the-national-urban-league-and-others. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

i (

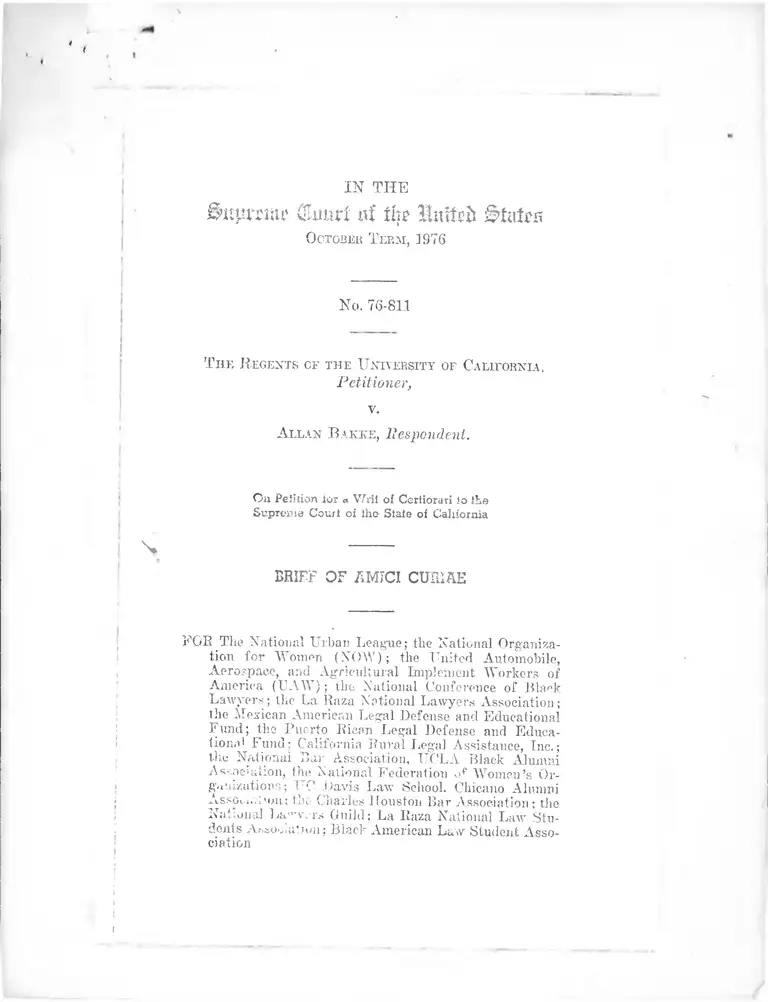

IN THE

8upraiu» Olimri' i\i tip United S tate

October T erm , 1976

No. 76-811

T h e R egents of th e U niversity of California ,

Petitioner,

v.

Allan B akke , Respondent.

On Peiition for a Writ of Certiorari io ihe

Supreme Court of Ihe Staie of California

%

BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE

BOB The National Urban League; the National Organiza

tion for Women (NOW); the United Automobile,

Aerospace, and Agricultural Implement Workers of

America (UAW); the National Conference of Black

Lawyers; the La Baza National Lawyers Association;

the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational

Fund; the Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Educa

tional Fund; California Rural Legal Assistance, Inc.;

the National Bur Association, UCLA Black Alumni

Association, the National Federation of Women’s Or

ganizations; UO Davis Law School. Chicano Alumni

AssocmPon: the Charles Houston Bar Association; the

National Lawyers Guild; La Raza National Law Stu

dents Association; Black American Law Student Asso

ciation

i

<

IN THE

(Emtrl nf tlj£ UttttTfc States

O ctober Term, 1976

No. 76-811

T h e R egents of t h e U niversity of California,

Petitioner,

v.

Allan B ak k e , Respondent.

On Petition for a W iil of Certiorari lo ihe

Supreme Court of the Stale of California

BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE

FOR The National Urban League; the National Organiza

tion for Women (NOW); the United Automobile,

Aerospace, and Agricultural Implement Workers of

America (UAW); the National Conference of Black

Lawyers; the La. Raza National Lawyers Association;

the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational

Fund; the Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Educa

tional Fund; California Rural Legal Assistance, Inc. ;

the National Bar Association, UCLA Black Alumni

Association, the National Federation of Women’s Or

ganizations; UC Davis Law School, Chicano Alumni

Association; the Charles Houston Bar Association; the

National Lawyers Guild; La Raza National Law Stu

dents Association; Black American Law Student Asso

ciation

E mma Coleman J ones

King Hall

Davis, California 95616

(916) 752-2758

(Other counsel

P eter D. B oos

Mexican American Legal

Defense and Educational

Fund

145 Ninth Street

San Francisco, California 94103

(415) 864-6000

listed inside front cover)

<■•361

I

S tephen I. S chlossberg

United Auto Workers

1125 15th Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 296-7484

F rank J . Ochoa, J r.

La liaza National Lawyers Assoc.

809 8th Street

Sacramento, California 95814

(916) 446-4911

T omas Olmos

Michele W ashington

Western Center for

Law & Poverty

1709 West 8th Street, Suite 600

Los Angeles, California 90017

(213) 483-1491

L ennox H inds

126 West 119th Street

New York, N.Y. 10027

Of Counsel:

J oseph L. R a uh , J r.

1001 Connecticut Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

S tephen P. B erzon

1520 New Hampshire Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

A lbert H. Meyerhoff

R alph S antiago A bascal

California Rural Legal

Assistance, Inc.

115 Sansome Street, Suite 900

San Francisco, California 94104

(415) 421-3405

Charles R. L awrence III

University of San Francisco

School of Law

San Francisco, California 94117

(415) 666-6986

J eanne Miner

National Lawyers Guild

853 Broadway

New York, N.Y. 10003

(212) 260-1360

B lack A merican

L aw S tudent A ssociation

i

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

I nterest oe A mici Curiae ...................................................... 2

I. Introduction .................................................... 6

II. As a result of Bakke’s lack of standing to sue,

no case or controversy exists herein as required

by Article III .................................................. 7

A. The Requirements of Article I I I ................ 7

B. The Facts of This Case Do Not Comport With

the Article III Requirement ...................... 9

1. The Application Process ........................ 9

2. The Bakke Applications.......................... H

C. The “ Stipulation” by the University Is an

Effort to Fabricate Jurisdiction in This

Court ........................................................... 23

111. Because the issue on the merits is so important

to the entire nation, this case should not he dis

posed of on the merits on the basis of such a

sketchy record............. 29

A. A Fully Developed Record Is Essential To a

Reasoned and Principled Judgment in This

Case ............................................................. 29

B. The Record ................................................ 23

1. The Evidence Presented by the University 23

2. The Evidence Not Presented by the Uni

versity .................................................... 23

Conclusion ................................................................................. 27

A ppendix A ................................................................ 2a

A ppendix B ................................................................ 9a

11

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CaseS: Page

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Corp.,

— U.S. — (January 11, 1977) (Slip. Opp. at E538-

^42) .................................................................... g

Associated General Contractors of Mass., Inc v Alt

shuler, 490 F.2d 9, cert, den., 416 U.S. 957 (1st Cir.

1973) ................................................................. 20 24

Bakke v. Board of Regents of the University of Cali

fornia, 18 Cal. 3d 34 (1976) ..................... 22 26

Brown v-Board of-Education, ,347- U.S. 483 (1954)’!.. ’ 6

Contractors Assn, of Eastern Penn. v. Secretary of

Labor, 442 F.2d 159 (3rd Cir., 1971), cert. den.

404 U.S. 845 (1971) ............................. 24

BeFunis v. Odegaard, 416 U.S. 312 (1974) . . . 1 9 ' 2 4 25

Flast v. Cohen, 392 U.S. 83, 99 (1968).......... ’ ’ 7

Hatch v. Reardon, 204 U.S. 152, 160 (1907) . .'.’.’.’ ’ ’ ’ 7

Jackson v. Pasadena City School District, 59 Cal. 2d

876 (1963) ......................................... 2g

Kahn v. Shevin, 416 U.S. 351 (1974) . . . . . . ............... ' 04

Lau v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563 (1974) .......... 25 26

Lehon v. City of Atlanta, 242 U.S. 53 (1916)............. ’ 7

Lord v Veazie, 49 U.S. (8 How.), 251, 255 (1850) ’.’.’ 18

Massachusetts v. Pamten, 389 U.S. 560, 561 (1968) 94

Morales v. State of New York, 396 U.S. 102, 104-06

(1969) ................. 29

Muskrat v. United States, 219 U.S. 346 (1911)............ ]8

Naim v. Naim, 350 U.S. 891 (1956) . . 21

Newsoin v. Smyth. 365 U.S. 604, 604-05 (1961).............. 9i

Poe v. Ullman, 367 U.S. 497 (1961) ........... . ............ o2

Rescue Army v. Municipal Court, 331 U.S. 549* (1947) 21

Richardson v. Ramirez, 418 U.S. 24, 36 (1974) .......... 1(3

Schlesinger v. Reservists to Stop the War 418 US

208 (1974) ..........................~..............J ]8

Sierra Club v. Morton, 405 U.S. 727, 734-735 (1972)’. ' 8

Simon v. Eastern Kentuckv Welfare Rights Organiza-

_ tion, — U.S. —, 96 S.Ct. 1917..................... 8 13 94

Smith v. Mississippi, 373 U.S. 238 (1963)............... ’ ' ’ 21

Swift & Co. v. Hocking Valiev Ry. Co., 243 U S ”282

289(1917) ...................14

United States v. Richardson, 418 U.S. 166 (1974)’...' . 8,18

Table of Authorities Continued iii

Page

Wainwright v. City of New Orleans, 392 U.S. 598

(1967) ................................................................. 21

AVarth v. Seldin, 422 U.S. 490 (1975) ...................8,13,18

Washington v. Davis, — U.S. —, 96 S.Ct. 2040 (1976) 25

R egulation :

Executive Order No. 11246, 30 Eed. Reg. 12319 (Sept.

24, 1965) .............................................................. 20

Miscellaneous :

Bickel, Alexander, T he L east D angerous B ranch ; The

Supreme Court at the Bar of Politics, Bobbs-Mer-

rill, 1962, 169-82 ......................................... _......... 20

California Assembly, Spec. Subcomm. on Bilingual-

Bicultural Education, “ Toward Meaningful and

Equal Educational Opportunity: Report of Hear

ings on Bilingual-Bicultural Education (July,

1976) ........................................................... .. .. 26

Educational Testing Service, Law School Validity

Study Service, 21 (1973) .................................. '. 26

Feitz, “ The MCAT and Success in Medical School”,

Sess. #■’ 9.03, Div. of Educ. Meas. and Research,

AAMC (rnimeo) .................................................. 25

Frankfurter, A Note on Advisory Opinions, 37 Harv.

L. R ev. 1002, 1006, n. 12 (1924) ......... ................ 7

Griswold, Some Observations on the DeFunis Case, 75

Colum. L. R ev. 512, 514-515 (1975) ..................... 26

Pollack, “ DeFunis Est Non Disputandum”, 75 Colum.

L. R ev. 495, 509 (1975) ....................................... 20

Simon, Performance of Medical Students Admitted

Via Regular and Admissions-Variance Routes, 50

J. Med. E d. 237 (March, 1975) ........................... 25

!

t

2

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE 1

The National Urban League, Inc., is a charitable

and educational organization organized as a not-for-

profit corporation under the laws of the State of New

York. For more than 65 years, the League and its

predecessors have addressed themselves to the prob

lems of disadvantaged minorities in the United States

by improving the working conditions of blacks and

other minorities, by fostering better race relations

and increased understanding among all persons, and

by implementing programs approved by the League’s

interracial board of trustees.

The NOW Legal Defense and Educational Fund

is the litigation and education affiliate of the National

Organization for Women. NOW is a national mem

bership organization of women and men organized

to bring women into full and equal participation in

every aspect of American society. The organization

has a membership of approximately 30,000 with over

five hundred chapters throughout the United States.

Many of its members are university women faculty

and students.

The UAW is the largest industrial union in the

world, representing approximately a million and a

half workers and their families. Including wives and

children, UAW represents more than UA million per

sons throughout the United States and Canada. The

UAW, which is deeply committed to equal opportunity

1 Letters of consent from counsel for the petitioners and the

respondents have been filed with the Clerk of the Court.

3

and anti-discrimination, does much more than bar

gain for its members. I t is by mandate of its Consti

tution and tradition deeply involved in the larger issues

of the quality of life and the improvement of demo

cratic institutions. The question presented by this case

vitally affects the UAW and its members.

The National Conference of Black Lawyers, through

its national office, local chapters, cooperating at

torneys and the law student organization, has (1 )

carried on a program of litigation, including defense

of affirmative suits on community issues; (2) moni

tored governmental activity that affects the blac'

community, including judicial appointments, and the

work of the legislative, executive, judicial and adminis

trative branches of government; and (3) served the

black bar through lawyer referral, job placement, con

tinuing legal education programs, defense of advo

cates facing judicial and bar sanctions, and watchdog

activity on law &enool admissions and curriculum.

La Baza National Lawyers Association is a nation

wide group of attorneys of Mexiean-American heri

tage The Association is committed to working for the

movement toward equality of Mexican Americans in

American society. To achieve this end, the Association

is committed to increase the admission of Mexican-

Americans to law schools and the legal profession in

order that the legal needs of Mexican-Americans can

be represented to the fullest in the courts of our nation.

The National Lawyers Guild is an organization

founded in 1937 with over 5,000 members. I t works to

maintain and protect civil rights and civil liberties.

I

4

IJ.C. Davis Law School, Chicano Alumni Association

is a group of Chicano graduates of the Martin Luther

King, Jr. School of Law at U.C. Davis. The Associa

tion’s goals are twofold: (1) To operate as a forum for

communication for Chicano law graduates in order

that they can work for the social betterment of the

Chicano people; and, (2) to maintain communication

with Chicano law students at the Davis Law School in

order to assist the students in the areas of admis

sion, retention and graduation.

The U.C.L.A. Black Alumni Association is com

posed of graduates of the U.C.L.A. special admissions

program who are interested in the continuing vitality

of the special admissions programs as one vehicle of

assuring representation of minorities in the Univer

sity’s graduate schools. In conjunction with the Uni

versity, this Association has a continuing interest in

maintaining such programs.

The Mexican American Legal Defense and Educa

tional Fund is a privately funded civil rights law firm

dedicated to insuring that the civil rights of Mexican

Americans are properly protected; a major thrust of

their effort has been in the area of education, includ

ing higher education, for which they have established

a Task Force of prominent Mexican Americans to ad

vise them. They filed an amicus brief in the instant

case when it was pending in the California Supreme

Court.

The Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Educational

Fund is a privately funded civil rights law firm dedi

cated to insuring that the civil rights of persons of

Puerto Rican ancestry are fully protected. They have

been greatly involved in education litigation on behalf

of Puerto Rican students.

5

National Bar Association, Inc., was formally orga

nized in 1925. I t consists of jurists, lawyers, legal

scholars and students whose purpose and programs

have sought to combat the effects of racial discrimina

tion and to advance the realization of the goal of first

class citizenship for all Americans. The membership

of the Association has successfully advanced the in

terests of minority citizens in the areas of housing,

employment, education, voting, and protection of the

rights of criminal defendants.

La Baza National Law Students Association is a

nationwide group of Chicano and Latino law students

organized for the following purposes: 1 ) to recruit

Chicanos and Latinos to attend law schools; 2) to as

sist in the retention of Chicano and Latino law stu

dents once they are admitted to law school; and 3) to

promote the provision of legal services to Chicano

and Latino communities throughout the nation.

Charles Houston Bar Association is an association

principally comprised of Black attorneys in North

ern California. I t is an affiliate of the National Bar

Association, a nationwide association of Black attor

neys and students. Charles Houston Bar Association

has been actively involved in promoting and protect

ing the civil rights of all minorities. I t includes among

its members, judges, attorneys and law professors, and

has a close relationship with minority student associ

ations.

California Rural Legal Assistance, Inc., is an oi-

ganization funded under the Legal Services Corpora

tion Act to provide legal assistance to low-income in

dividuals. A high proportion of its clients are mem

bers of racial minority groups, and a good deal of its

/

6

efforts have been directed toward combatting the ef

fects of facial discrimination against these clients in

many segments of American society.

BALSA was founded in 1968 in NY and has 7,000

Black law students among its membership. Its purpose

is to articulate and promote goals of Black American

law students, encourage professional competence and

instill in the Black attorney and law student a greater

awareness of and commitment to the needs of the Black

community.

I.

INTRODUCTION

Whether the Constitution will permit the use of

affirmative efforts by institutions of higher education

to overcome historical discrimination and segregation

of racial minorities is an issue of vital importance,

both to amici, and to the American society at large.

The Court’s resolution of the issue presented in this

case may determine the future course of integration

efforts not only in the medical profession, but in other

professions and the educational avenues leading to

them. Such a decision will have a dramatic and long

term impact on civil rights and race relations for fu

ture decades in this country. The resolution of this

issue may in many ways approach in importance the

landmark decision, Brown v. Board of Education 347

U.S. 483 (1954).

Although desirous that this important issue be

finally resolved, amici strongly urge that a decision not

be rendered in the case at bar. I t is essential that this

issue may be resolved in a case where a spirited conflict

between the parties has resulted in a fully developed

7

record upon which to base such an important decision.

The crux of amici’s position is that instead petitioners

have attempted, to “ stipulate” to this Court s jurisdic

tion in order that they can seek an advisory opinion on

this critical issue in a case with a sparse record and

without the presence of a case or controversy as man

dated by Article I I I of the United States Constitution.

An issue of this magnitude simply cannot be resolved

in a case which severely lacks “ that concrete adteise-

ness which sharpens the presentation of issues upon

which the Court so largely depends for illumination of

difficult constitutional questions” . Flast v. Colien, 392

U.S. 83, 99 (1968).

II.

AS A RESULT OF BAKKE'S LACK OF STANDING TO SUE, NO

CASE OR CONTROVERSY EXISTS HEREIN AS REQUIRED BY

ARTICLE III

A. The Requirements of Article III.

In a formulation of the rule directly applicable to

the facts of this case, this Court in T1 last v. Cohen,

supra, at 99 stated the requirement of standing as a

constitutional prerequisite to federal jurisdiction:

The fundamental aspect of standing focuses on

the party seeking to get his complaint before a fed

eral court and not on the issues he wishes to have

adjudicated.2

2 As Mr. Justice Frankfurter stated:

One must oneself be made a victim of a law (Lclion v. City

of Atlanta, 242 U.S. 53 (1916)) or belong to the class ‘for

whose sake the constitutional protection is given’ (Hatch v.

Reardon, 204 U.S. 152, 1G0 (1907)) to be able to invoke

the Constitution before the Court. Frankfurter, A Note on

Advisory Opinions, 37 Harv. L. Rev. 1002, 1006, N. 12 (1924).

8

Last term this Court reiterated this rule as follows:

• : • The standing question in its Art. I l l aspect

“ is whether the plaintiff has 'alleged such per

sonal stake in the outcome of the controversy’ as

to warrant his invocation of federal court juris

diction and to justify exercise of the court’s reme

dial powers on his behalf.” Worth v. Seldin, 422

U.S. 490, 498-499 (1975) (emphasis in original).

In sum, when a plaintiff’s standing is brought into

issue the relevant inquiry is whether, assuming

justiciability of the claim, the plaintiff has shown

an injury to himself that is likely to be redressed

by a favorable decision. Absent such a showing,

exercise of its power by a federal court would be

gratuitous and thus inconsistent with the Art. I l l

limitation. Simon v. Eastern Kentucky W It 0

U .S .----- , ----- , 96 S.Ct. 3917,----- , (1976)'!

Accord Sierra Club v. Morton, 405 U.S. 727, 734-

35 (1972) ; United States v. Richardson, 418 U S

166, 174 (1974).3

This causation requirement is not met by the facts of

this case. This Court’s jurisdiction can only be exer

cised if it is shown, first, that Bakke suffered a “ spe

cific harm” to himself as “ the consequence” of the

Task Force program at U.S. Medical School, Wartli

\. Seldin, supra, at 505 (1975). No such showing has

or could be made. To the contrary, as strongly sup

ported by the evidence in the record and as specifically

stated in the trial court’s findings, “ plaintiff would not

ha\ e been accepted for admission to the class entering

the Davis Medical School . . . [in 1973 and 1974] even

8 Just this week, the Court once again reaffirmed the Warth-Simon

principle that an “ actionable causal relationship” must be demon

strated between the challenged conduct and the asserted injury.

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Corp.,___ US ___ 1

(January 11, 1977) (Slip. Opp. at B538-B542). ’

9

if there had been no special admissions program.”

(Pet, for Cert., Ajrp. F. p. 116a.)

B. The Facts of This Case Do Noi Compori with ihe Ariicle III

Requirement.

Mr. Bakke applied to the Davis Medical School in

1973 and 1974. In each of these years, he was not se

lected for any of the 84 regular admission positions

available.4 It is his contention that he wquld have been

admitted had (lie 16 Task Force positions been opened

and available to regular applicants. In short, this

proposition is premised on the belief that his applica

tion was among the top 16 regular applicants not ad

mitted. The evidence in the record reveals Bakke’s

premise to be totally without foundation.

1. The application process.

In order to understand why it is relatively, easy to

make such an assertion, it is necessary to realize that

all applicants were given a “ Benchmark score” which

was the primary tool for comparing candidates. This

Benchmark score was a composite of many factors in

cluding scores on the MCAT examination, grade point

average, and evaluations flowing from various inter

views. Testimony indicates that with only minor excep

tions, not relevant to Bakke, an applicant with a

higher Benchmark score was admitted over one in the

same batch with a lower score (CIV 63-64). This was

true, only with respect to those applications which

4 In 1973, there were in fact 85 regular admission positions and

15 Task Force positions. This recently discovered fact was not

reflected in the trial court record. See n. —, infra.

5“ Ct ” References are to the Clerk’s Transcript filed in the

California Supreme Court.

|

10

were considered within the same period of time be

cause it was tiie practice to evaluate the applications in

“ batches” (CT. 63-64). In the first month in which

acceptances were made, applications then on file would

be evaluated in order to send out early offers.

After a sampling of acceptances were received,

which would indicate an acceptance rate adequate to

fill the number of spaces still available, all of the pre

viously received applications which were competitive

but had not prompted offers would be compared with

recently received applications and a second round of

offers would go forth to fill the remaining slots. The

applications thus on file in January would be evaluated

against each other. The applicants with the highest

Benchmark scores receive offers. The applications on

file during successive rounds would likewise be evalu

ated and offers would go to those with the highest

Benchmark scores. Thus, the two determinative factors

in the decision-making process were the Benchmark

score that the applicant was given and the time when

the application was considered. At the conclusion of

this process, the remaining students, who were numer

ically close to admission, were placed on an alternate

list. Inclusion on the alternates list was not based on

strict numerical rankings. The Dean of Admission had

discretion to admit persons who would bring special

skills. I t should be noted that the Dean in neither year

exercised his discretion to place Bakke on the alternate

list (CT. 64). This then is the basic framework from

which the Dean of Admission in uncontroverted testi

mony and the trial court, on the basis of such testi

mony, was able to determine that Mr. Bakke would not

have been admitted even in the absence of the Task

Force program.

11

2. The Balcke applications.

Bakke’s 1973 application, his first, was not received

until “ quite late”, and was thus prejudiced by the fact

that a substantial number of the positions had already

been filled (CT. 6-1). Earlier applicants, regular as

well as Task Force, had been accepted for admission

prior to consideration of Bakke’s application (CT.

54, 181). Thus, his application was competing for an

otherwise more limited number of remaining positions

against a larger number of competitors. Mr. Bakke’s

1973 Benchmark score was 468. As the Dean of Ad

mission stated, “ [i]n filling the 100 spaces in the class

no applicants with ratings below 470 were admitted

after Mr. Bakke’s evaluation was completed”. (CT

69).

Assuming that none of the Task Force admittees

had been able to meet the regular admission standards

and that all 16 positions were available, the Dean of

Admissions has unequivocally stated that Bakke would

nevertheless have been denied admission:

“ Indeed, Plaintiff would not even have been

among the 16 who would have been selected assum

ing that all of the places reserved under the spe

cial admissions program had been open following

Plaintiffs’ evaluation. Almost every applicant of

fered a place in the class after the middle of May

attends the medical school. There were 15 appli

cants at 469 ahead of Mr. Bakke and he would not

have been among the top applicants at 468 because

he was not a 468 put on the alternates list as he

had no special qualifications or new information

upgrading his score.”

(CT. 70).

Indeed there were twenty students in 1973 who like

Bakke had 468, some of whom were jdaced on the al-

i

12

ternates list due to special qualifications (CT. 70)

t thus is certain that at least 16 persons had priority

over Mr Bakke in 1973 and, thus, as the trial court

ound, the demise of the Task Force program would

not have resulted in his admission.

-,n^he e7 dence is even str°nger regarding Bakke’s

1974 application. His 1974 Benchmark score was 549

out of 600. The record shows that there were a total of

20 applicants on the alternates list who would have

een selected for any additional positions. Once again,

Bakke was not on the alternates list in 1974. Further

more there were an additional 12 applicants, not on

the alternates list, with numerical ratings above

Bakke s 549 (CT. 71). Thus, there were at least 32

applicants who were ahead of Bakke for the 16 pos

sible positions. As the Dean of Admission stated, in

dld 110t even “ come close to admission”( C l . <1).

An additional factor which would have operated against

T<Wke ®aP-?+hCatl0n f the dof,nite Possibility that some of the Task

1 orce admittees would have been able to gain admission under the

reguiar admissions process. While there are no numerical ratings

of Task Force admittees available, the record does disclose that the

oveiall grade point average of such admittees ranged un to 3 76

grade point averages ranging up to 3.45 and science grade point

averages rangmg up to 3.89 (CT. 178. 223). Bakke’s scores were

" and 3‘4̂ respectively. (CT. 115). Thus, in both 1973 and 1974

paTsedThat of B I?1'06 aPpl!,cant8 whose 8Tades equalled and sur-

Pa).' d tha? ,of Bakke and who could have met certain of the non-

a t te thmC1FinniiS1 I"11,0’1 S I 01’8 makhlg their «PPlications more lhactne. 1 mally, it should be noted that in 1973 Bakke was

emed admission at 10 other Medical Schools to which he applied

(Bowman-Gray, University of South Dakota, University of Gin-

U C L A San °F atG- Georgetown University, Mayo,

tt’ • an. Brancisco> Stanford and his undergraduate alma

mater, University of Minnesota) (CT. 48-49).

13

In conclusion, the uncontrovertecl evidence strongly

supports the finding of the trial court that the Task

Force program had no effect on Bakke’s application in

that lie would have been denied admission regardless

of the program’s existence.

As in Warth, where the facts failed to show that the

restrictive zoning practices resulted in plaintiffs’ ex

clusion, here the record is equally devoid of any facts

showing that the Task Force program resulted in

Bakke’s exclusion from the Davis Medical School No

showing is possible that “ but for” the Task Force pro

gram, Bakke would have been admitted. In short, no

“ casual relationship” exists on these facts. Wartli

supra, 422 U.S. at 407.

Bakke is simply not within the class of persons

affected by the policy he seeks to challenge. The parties

seek a “ gratuitous” decision of complex and vitally

important issues in this case “ inconsistent with the

Article I I I limitation”. Simon, supra,___ U S ____

96 S.Ct. 1917.

C. The 'Stipulation" By the University is an Effort to Fabricate

Jurisdiction in This Court.

_ Under the standards of Article III , as has been pre

viously shown, Bakke does not have sufficient standing

to prosecute this litigation in the federal courts. The

University, in its rush to obtain a judgment from this

Court, recognized this fatal flaw after the California

Supreme Court filed its opinion. At the time of its

Petition for Rehearing in the California Supreme

Court, the University sought to correct it. What it did,

in essence, was to “ stipulate” to this Court’s jurisdic

tion in order to obtain the advisory opinion they seek.

Such a “ stipulation” was a pure fabrication of the

(

14

facts, contrary to the University’s insistent position

up to that date, and contrary to the trial court’s find

ings; 7 further it is ineffectual under this Court’s con

sistent rulings that parties cannot stipulate to juris

diction Swift & Co. v. Hocking Valley By. Co., 24:;

U.S. 282, 2S9 (1917).

The California Supreme Court in its September

16th Order remanded to the trial court the issue of

whether Bakke would have been admitted to the Davis

Medical School in the absence of the Task Force pro-

7 The Petitioners make reference to an aside by the trial court in

its initial Notice of Intended Decision that there was “ at least a

possibility that [Bakke] might have been admitted” absent the

Task Force program. (Pet. for Cert, at II, n. 4) The Court then

went on to find specifically to the contrary. (Id., at 116a). Subse

quently, after further briefing and argument, the trial court spoke

with even greater finality in its Addendum to Notice of Intended

Decision:

The Court has again reviewed the evidence on this issue and

finds that even if 16 positions had not been reserved for mi

nority students in each of the two years in question, plaintiff

still would not have been admitted in either year. Had the

evidence shown that plaintiff would have been admitted if

the 16 positions had not been reserved, the court would have

ordered him admitted. (Id., at I lia ) .

And the court after discussing the record in detail concluded

subsequently in its Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law that:

Plaintiff would not have been accepted for admission to the

1973 class even if there had been no special admissions pro

gram; * * * Plaintiff would not have been accepted for ad

mission to the class entering Davis Medical School in 1974

even if there had been no special admission program (Id., at

116a-117a).

Dr. Lowery’s Memo to II.E.W., referred to at n.4 of the Petition

for Certiorari, merely bemoans the fact that a “ lack of available

space” exists in the Medical School and had “ additional places'

existed, Bakke may have been admitted. This in no way contradict*

the trial court’s findings that given the existing space limitation*

Mr. Bakke would not have been admitted even if the 16 slot*

had become available.

15

gram, shifting the burden to the University to estab

lish that Bakke would not have been so admitted. The

court did not intimate in any way, however, that the

uncontroverted and substantial evidence presented by

the University at the trial level was insufficient; it

merely stated that this evidence must be evaluated in

light of the different burden (18 Cal. 3d at 64).8

The University subsequently attached a “ stipula

tion” to its Petition for Rehearing, which purported

to concede that the University could not meet this

burden.7 The Petition, relying upon this “ stipulation”

urged the court to remand to the trial court to order

Bakke admitted to the Medical School. The California

Supreme Court on the basis of the stipulation so

ordered.

The logical question flowing from the stipulations is

why the University contrary to its insistence that Mr.

Bakke would not have been admitted even in the

absence of the task force program essentially reversed

its position at such a late date. (See pp. —, supra.)

The answer to this question is that the University

realized that the record, in the absence of tbe stipula

tion, clearly showed a lack of jurisdiction in this Court

to decide an issue that it clearly wished addressed: as

the University said in urging the Court to order Bakke

admitted:

I t is far more important for the University to

obtain the most authoritative decision possible on

8 An analogue to the present ease would be a woman not pregnant

seeking to invalidate an abortion law in federal court and, although

conclusive evidence showed her not to be pregnant, the state (being

desirous of an advisory opinion) “ stipulating” that it was unable

to prove that fact in order to simulate a case or controversy.

16

the legality of its admissions process than to argiv

over whether Mr. Bakke would or would not havi

been admitted in the absence of the special ad

missions program. A remand to tbe trial court foi

determination of that factual issue might delay

and perhaps prevent review of the constitution;!

issue by the United States Supreme Court. Peti

tion for Rehearing, 11-12 (emphasis added).9

Admission of Mr. Bakke to the Medical School cor

tainly would not have “ prevented review” by thi

Court. By asking for this relief in the stipulation, ii

is clear that it was not admission that the Universit'

feared. Rather, it was ultimate success on remand t

the trial court with regard to Bakke’s admissibility

which the University wished to avoid. I t was precise!

their success which would have made apparent

Bakke’slack of Article I I I standing and thereby “ pre

vent” the review that the University so eagerly seek?

In other words, the University essentially gave up ar

air tight case in order to confer “ jurisdiction” on thi?

Court so that it could achieve its goal of obtaining “ tin

most authoritative decision possible” . (Ibid .)10

9 No problem arose until the University sought an opinion fron

this Court, for in California the same standing strictures are lie

applicable. However, as Justice Rehnquist, writing for the majoril;

in Richardson v. Ramirez, 418 U.S. 24, 36 (1974), observed: “ Whil

the Supreme Court of California may choose tG adjudicate a eon

troversy simply because of its public importance, and the desir

ability of a statewide decision, we are limited by the case-or-conti1"

versy requirements of Article III to adjudication of actual elk

putesbetween adverse parties” .

10 indeed there are indications predating the filing of this actioi

that the University’s primary aim was to ‘‘set the stage” for:

judicial determination of the validity of its Task Force program

In the summer of 1973, following his first denial, Mr. Ball

entered into an exchange of correspondence with the Admission-

However resourceful this attempt, a common

thread in this Court’s past and recent decisions has

been the view that the Court is not empowered to

Office of the Davis Medical School. In the first of three letters,

between Bakke and Assistant to the Dean of Admissions, Peter C.

Storandt, Storandt expressed sympathy for Bakke’s position. Fur

ther, he urged that Bakke “ review carefully” the Washington Su

preme Court’s opinion in DeFunis, sent him a summary of the

opinion, urged that he contact two professors known to be knowl

edgeable in medical jurisprudence (CT. 264-65), recommended

that he contact an attorney and concluded with the “ hope that . . ■

you will consider your next actions soon” (CT. 265).

Two weeks later, Bakke met with Storandt at the Davis Medical

School (CT. 268); and 5 days later Bakke wrote to Storandt as

follows:

Thank you for taking time to meet with me last Friday after

noon. Our discussion was very helpful to me in considering

possible courses of action. I appreciate your professional in

terest in the question of the moral and legal propriety^ of

quotas and preferential admissions policies; even more im

pressive to me was your real concern about the effect of ad

mission policies on each individual applicant.

You already know, from our meeting and previous correspond

ence, that my first concern is to be allowed to study medicine,

and that challenging the concept of racial quotas is secondary.

Although medical school admission is important to me person

ally, clarification and resolution of the quota issue is unques

tionably a more significant goal because of its direct impact

on all applicants (CT. 268; App. A)

Bakke’s letter then went on to outline his alternative litigation

strategies (CT. 268-69) consisting of “ Plan A ” and “ Plan B ” .

Storandt promptly replied. After remarking that, “ the eventual

result of your next actions will be of significance to many present

and future medical school applicants” (CT. 266), he went on to

suggest the use of “ Plan B ” over “ Plan A ” :

I am unclear about the basis for a suit under your Plan A.

Without the thrust of a current application for admission at

Stanford, I wonder on what basis you could develop a case as

plaintiff; if successful, what would the practical result of

your suit amount to? With this reservation in mind, in addi

tion to my sympathy with the financial exigencies you cite,

I prefer vour Plan B, with the proviso that you press the

suit—even if admitted—at the institution of your choice. And

!

i

18

decide important social issues merely because a part

wishes a decision. Lord v. Veazie, 49 U.S. (8 How.

251, 255 (1850) ; Muskrat v. United States, 219 U.S

346 (1911), United States v. Richardson, 418 U.S. 1(

(1974) (misuse of funds by the Central Inteiligeiii

Agency) ; Schlesinger v. Reservists to Stop the Wo

418 U.S. 208 (1974) (violation of incompatabilit

clause of Article I, § 6 cl. 2 of the Constitution) ; Wart

v. Set din, 422 U.S. 490 (1974) (constitutionality of r<

strictive zoning ordinances) ; while the last three cast

cited highlighted burning issues that great numboi

of persons had and have an interest in, that fact alou-

without more, was deemed insufficient to invoke tlii

Court’s jurisdiction.

This is not the first time that a party has attempte

by stipulation to circumvent this Court’s evaluate

of the true facts. However, as Justice Frankfurter ex

plained:

Even where the parties to the litigation have stipr

lated as to the ‘facts’ this Court will disregar

the stipulation—if the stipulation obviously Tor-

closes real questions of law. United States v. Felt

& Co., 334 U.S. 624, 640 (1948).

The rationale for looking behind a stipulation of fa-

that fails to correspond to real facts was further ex

plicated by Justice Frankfurter:

if this Court had to treat as the starting poii

for the determination of constitutional issues

spurious finding of ‘fact’ contradicted by an a-

judicated finding between the very parties to tl

there Stanford appears to have a challengeable prononnecnu'i

If you are simultaneously admitted at Davis under El’

[Early Decision Program], you would have the security -

starting here in twelve more months (CT. 266).

19

instant controversy, constitutional adjudication

would become a verbal game. Id., at 639.

In sum, it is just a “ verbal game” which the Uni

versity is playing with this stipulation. Thet facts and

the University’s own assertions up to the date of the

stipulation belie its validity. The University’s effort

to confer jurisdiction on this court should properly

be rejected.

I II .

BECAUSE THE ISSUE ON THE MERITS IS SO IMPORTANT TO

THE ENTIRE NATION. THIS CASE SHOULD NOT BE DISPOSED

OF ON THE MERITS ON THE BASIS OF SUCH A SKEiCHY

RECORD

A. A Fully Developed Record Is Essential to a Reasoned and

Principled Judgment in This Case.

The record in this case is so deficient that this Court

should decline to reach the merits. A decision on the

merits should not be made on such an important issue

on such a poor record. Rather, the Court should va

cate the decision below and remand for the taking of

further evidence. DeFunis v. Odegaard, 416 U.S. 312,

320 (1974) ; Morales v. State of New York, 396 U.S.

102, 104-06 (1969) (Order vacating and remanding for

taking of further evidence because of the “ absence of

a record that squarely and necessarily presents the

issue and fully illuminates the factual context in which

the question arises. . . . ” id., at 106.

Concededly, the substantive issue raised by the par

ties is vitally important. The numerosity of amici

and their participation at such an early stage in this

Court attest to that. A decision on the merits could

also have substantial bearing on employment practices.

t

20

See, e.g., Executive Order 11246, 30 Fed. Reg. 123]

(Sept. 24, 1965), as amended; Associated Gcn’l Co,

tractors of Mass., Inc. v. Altshuler, 490 E.2d 9, cer

den., 416 TT.S. 957 (1st Cir. 1973).

Petitioners are not engaging in hyperbole when the

characterize the issue as “ perhaps the most importai:

equal protection issue of the decade” . (Pet. for Cert

12.) I t is even more than that because of what it m;r

portent for the decades ahead, for both minorities air

the majority of our nation.

We do not propose that this case is not worthy of

certiorari because it lacks significance, but rather, pre

cisely because the issue is so very significant both tin

needs and interests of all affected persons as well a>

sound jurisprudential principles militate that the

Court closely examine the record to best insure that

this is the case to decide this issue. As Dean Pollack has

said, “ [t]he more important the issues, the more

strictly the Court must monitor the exercise of its awe

some discretion” . DcFunis Est Non Disputandum, 75

C oltjm. L . R ev. 495, 509 (1 9 7 5 ).

This Court’s power rests, not on the militia that it

can command, for it commands none. Rather, it rests

upon the soundness of its reasoning and the shared

belief of those who do and those who do not prevail

that reasoning is well-grounded in a fully developed

case. In the words of the late Professor Alexander

Bickel, the “ well-tempered case”, is the one which best

insures public and professional acceptance of this

Court’s awesome role of final constitutional arbiter.

The Least Dangerous Branch; The Supreme Court at

the Bar of Politics, Bobbs-Merrill, 1962 169-82; see

also, id., at 124, 197-98. The substantive issue in the

■

I

21

instant case is the paradigm of the prudent wisdom

embodied in the need for the “ well-tempered case” .

Frequently, this Court has declined to grant certio

rari because a record was not “ sufficiently clear and

specific to permit decision of the important constitu

tional questions involved. . .” Massachusetts v. Pain-

ten, 889 U.S. 560, 561 (1968). The Court declines its

W rit where a record is “ too opaque”, Wainwright v.

City of New Orleans, 392 U.S. 598 H967) (concur

ring opinion of Harlan, J .) or because “ the facts

necessary for evaluation of the dispositive constitu

tional issues in [the] case are not adequately presented

by the record”, id., at 599 (concurring opinion of For-

tas and Marshall, J .J .) . Accord, Naim v. Naim, 350

U.S. 891 (1956); Newsom v. Smyth, 365 U.S. 604,

604-05 (1961); Smith v. Mississippi, 373 U.S. 238

(1963).

The Court has broadly explained that the basis for

its rules of caution:

lie in all that goes to make up the unique place

and character, in our scheme, of judicial review

L of governmental action for constitutionality. They

are found in the delicacy of that function, parti

cularly in view of possible consequences for others

also stemming from constitutional roots [and] the

comparative finality of those consequences . . .

Rescue Army v. Municipal Court, 331 U.S. 549, 571

(1947) (emphasis added).

I

In the instant case, the “ others” are the disadvan

taged minorities who risk jeopardy of their rights on

an inadequate record, minorities who have not parti

cipated in the litigation. The University, at best, bears

only a limited risk because the intense competition for

places in the Medical School will insure that qualified

!

22

minority applicants will be replaced by other qualified

applicants.

We are not unmindful of the “ very real disadvan

tages, for the assurance of rights, which deferring de

cision very often entails.” Id., at 571. Lest there be any

doubt, we do not urge the Court to avoid the merits in

this case for the purpose of delay or deferral. Many

other similar cases are now on their way to this Court.

Rather, because of the extreme importance of the sub

stantive issues, we urge that the Court choose the

“ fully developed case” for disposition because:

a contrary policy, of accelerated decision, might

do equal or greater harm to the security of pri

vate rights. . . . For premature and relativelv ab

stract decision, which such a policy would be'most

likely to promote, have their part too in rendering

rights uncertain and insecure. Id., at 572."

The applicability of these rules: can be deter

mined only by an exercise of judgment relative to

the particular presentation, though relative also

to the policy generally, and to the degree in which

the specific factors rendering it applicable are ex

emplified in the particular case. It is largely

question of enough or not enough, the sort of thing

precisionists abhor but constitutional adjudication

nevertheless constantly requires. Id., at 574 (em

phasis added) Accord, Poe v. Ullman, 367 U.S.

497, 508-09 (1964). The following examination of

the record demonstrates that, given the impor

tance of this case, there is just “ not enough.”

Ihe rush to judgment in the instant ease encompassed both

the parties: the ease was tried on a paper record tantamount to

summary judgment, 18 Cal. 3d at 39; and the California Supreme

Court exercised its rarely used power to transfer a cause to it.

“ prior to a decision by the Court of Appeal, because of the im

portance of the issues involved” . Id.

23

B. The Record.

1. The Evidence presented hy the University.

The only affirmative proof presented by the Univer

sity in its defense and in support of its request for a

declaratory judgment was one eleven-page declaration

by the Chairman of the Admissions Committee, Dr.

Lowry (CT. 61-72). Apart from discussion of Mr.

Bakke’s personal situation, the declaration merely

makes a series of conclusionary statements. Xo other

evidence was presented since the University stipulated

that the case could he decided on the basis of this decla

ration and the paper evidence generated by Mr. Bakke.

2. The Evidence not presented hy the University.12

The California Supreme Court’s decision turned

directly upon: (1 ) its perceived rule of law that:

“ [a.Jbsent a finding of past discrimination—and thus

the need for remedial measures to compensate for . . .

prior discriminatory practices . . ., the preferential

treatment of minorities . . . is invalid on the ground

that it deprives a member of the majority of a benefit

because of his race”, 18 Cal. 3d at 57-58.

12 The following discussion relates only to some of the Univer

sity’s most glaring evidentiary omissions. Not only is the record

barren of facts, but recent discoveries point to at least one rather

important misstatement of fact. The record states that in 1974,

there were sixteen Task Force Admittees, while recent revelations

indicate that in fact there were fifteen. This error is neither harm

less nor insignificant since it appears that the sixteenth “ slot” was

returned to regular admissions for the Task Force felt that there

was need for a more qualified admittee. Letter of Dr. S. Gray,

App. B, infra.) This substantially undercuts the finding of the

Court below that the program is “ a form of an educational quota

system” (18 Cal. 3d at 62) reflecting a “ rigid proportionality”

(id. n. 33).

/

24

and, (2) the absence of not only such a finding, but j

deed, “ no evidence in the record to indicate that tl

University lias discriminated against minority apai

cants in the past”. Id,, at 59. Based on a record si]',

on this crucial point, the California Supreme Con

concluded that it “ must presume that the Universit

has not engaged in past discriminatory conduct”. /,

at 60 (emphasis added). Thus, upon this thin reed <

piesumption, the Task Force program was held j]

Aalid. In short, the Court’s decision “ depends upo

unalleged and unknown facts”. Simon v. Eastern Kn

tuchy WHO, supra, 96 S.Ct. at 1927, n. 25.

While we take strong exception to this holding o:

the California Supreme Court, see, e.g., Associate

(yen. Contractors of Mass. v. Altshuler, 490 F.2d 9 (k

Cir. 1973), cert, denied, 416 U.S. 957 (1974) ; Contrae

tors Assn, of Eastern Penn. v. Secretary of Labor 44:

F.2d 159 (3rd Cir. 1971), cert, denied, 404 U .S ' 84.'

(1971) ; cf., Kahn v. She via, 416 U.S. 351 (1974)', tin

only prudent position by a university set upon present-

ing all possible defenses would have been to offer evi

deuce of past discrimination, given the long line of

cases supporting affirmative action programs llowiir

from such a finding.

One obvious evidentiary discrepancy in this record

relates to the Medical School Admissions Test

(AXCAT). The lack of evidence on this point is striking

m light of the guidance given by Justice Douglas on

this very point in his dissent in Pe Pa n is v. Odeaaard

416 U.S. 312, 327-37 (1974). While the view of one

Justice of this Court is not controlling sound trial

strategy would warrant that the tactic should he at

tempted. I t was not just a passing thought of Justice

Douglas. Nearly all of his 28-jiage dissent is devoted

L

25

to the issue and it concludes with the belief that the

matter should be remanded for the taking of evidence

on the point. Thus, the point here is not whether or

not the MCAT will ultimately be found the be racially

biased, but the fact that the record is silent on this

important issue.

In dictum, the court below dismissed pleas by amici

to follow the course of action urged by Justice Douglas

in Do. Funis. The court believed that in spite of the

racially disproportionate impact of the MCAT, its use

is not unconstitutional, relying on Washington v.

Davis,----- U .S .------ , 96 S.Ct. 2040 (1976). The latter

case is inapposite. Washington cannot be read to say

that a university is barred from compensating for an

uncontroverted degree of bias in a test instrument

which it, because of circumstances, is forced to rely

upon in part. Yet, if the record had been fully devel

oped, such fact could have been shown. Since the Uni

versity receives federal funds, it is subject to Title

V I of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 TJ.S.C. § 2000d

(CT. 24, 278) and its implementing regulations, 45

C.F.R. §80; discriminatory effect, irrespective of dis

criminatory purpose, would impose an obligation on

the University to demonstrate, the validity of the

MCAT. Lau v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563, 568 (1974).13

13 A recent study on the relationship between the MCAT and

siiceess in medical school by the Association of American Medical

Colleges has found that Blacks who had successfully completed

the first two years of medical school had lower MCAT averages

than whites who had flunked out. Robert II. Feitz, The MCAT

and Success in Medical School, Sess. #9.03, Div. of Education

Measurement and Research, AAMC (mimeo). See also, Simon,

et al., Performance of Medical Students Admitted Via Regular

And Admissions— Variance Routes, 50 J. Med. Ed. 237 (Mar.

1975). Thus, there is evidence available to prove that the MCAT

>

26

In addition to the absence of evidence of discrimina

tion against minority applicants on the part of the

Medical School itself, the record is devoid of evidence

to prove that the State of California, through its edu

cational system, has discriminated against minority

students in numerous ways that have deprived them of

an equal opportunity to gain admission to medical

school. See, e.g., Jackson v. Pasadena City School Din-

trxet, 59 Cal. 2d 876 (1963) (segregation) Lau v. Nich

ols, 414 U.S. 563 (1974) (language), California Assem

bly, Special Subcomm. On Bilingual-Bicultural Edu

cation, “ Toward Meaningful And Equal Educational

Opportunity: Report of Hearings on Bilingual-Bi

cultural Education” (July, 1976). Closely related is

the absence of any evidence relating to the omnipresent

influence of racial discrimination that mars this Na

tion’s history.

Another serious defect in the record relates to the

“ compelling state interest” test and its “ less onerous

measures Blacks as “ less qualified” than some whites, when they

are in fact “ better qualified” .

This evidence, never before the trial court or California Supreme

Court, puts into serious doubt the very question at issue before it:

whether the Special Admissions Program at U.C. Davis Medical

School “ offends the constitutional rights of better qualified appli

cants denied admission . . . . ” 18 Cal. 3d at 38, (emphasis added).

In addition, there is substantial reason to doubt the predictive

value of the MCAT as applied to all applicants. “ The highest cor

relation recorded for MCAT scores with medical school grades at

Harvard was 0.22, and an average correlation of 0.15 [at other

schools] supports the conclusion that the MCAT is unable to dis

criminate meaningfully among . . . pre-medical students” . Whittieo.

The President’s Column: The Medical School Dilemma, 61 -T.

N at’l Med. A 174, 185 (March, 1969). Similarly, correlations of

combined I,SAT (Daw School Admissions Test) and undergraduate

grade point averages, among ninety-nine law schools studied, nuts

from 0.2 to 0.7, with the median being 0.43. Educational Testin'!

Service, Law School Validity Study Service, 21 (1973).

See also, Griswold, Some Observations On the DeFunis Case,

75 Colum. L. Key. 512, 514-15 (1975).

fc»

27

alternative” counterweight. The University has harsh

criticism for the California Supreme Court s clearly

fanciful speculation’ ” regarding the efficacy of its

self-hypothesized alternatives (Pet., 39, 16-17). The

criticism is deserved but more deserved is criticism

of the total absence of any evidence on these critically

determinative points. For example, the University

sought, in part, to establish as a compelling state in

terest the greater rapport that, minority doctors would

have with minority patients and the fact that an in

crease in the number of minority doctors may help to

meet the crisis now existing in a minoiity community

seriously lacking adequate medical case. 18 Cal. 3rd at

53. But, “ the record contains no evidence to justify”

this proposition. Id. Of course, it is easier for a court

to dismiss an assertion which is unsupported by the

“ flesh” of an evidentiary basis.

Another example of the paucity of the record is the

fact that “ the only evidence in the present record on”

the unavailability of alternative means is the admis

sion committee chairman’s statement that, ‘in the judg

ment of the faculty of the Davis Medical School, the

special admissions pvogvam is the only method wheieby

the school can produce a diverse student body . . . ”

18 Cal. 3rd at 89 (Tobriner, J., dissenting) (emphasis

in original). This was an issue deserving extensive

evidentiary devel opment.

CONCLUSION

The importance of the substantive issues in this case

extends far beyond the parties because of the role of

the basic policy at issue in overcoming the historical

consequences of exclusion. The interests of the “ major

ity” are inextricably hound to, and congruent with, the

interests of the “ minorities” because of this nation’s

ineluctable movement to racial harmony and peace.

This Court’s long-standing commitment to further this

/

28

development would be ill-served by addressing tb

merits in light of the crucial Article I I I defect and ,

record so wanting in the necessary elements for tb

exercise of this Court’s plenary power.

Respectfully submitted,

E mma Coleman J ones

Acting Professor

UC Davis School of Law

Davis, California 9561G

(916) 752-2758

S tephen I. S ciilossberg

United Auto Workers

1125 15th Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 296-7484

F rank J . Ochoa, J r.

La Eaza National Lawyers Assoc.

809 8th Street

Sacramento, California 95S14

(916) 44G-4911

T omas Olmos

Michele W ashington

Western. Center for

Law & Poverty

1709 West 8th Street, Suite GOO

Los Angeles, California 90017

(213) 483-1491

L ennox H inds

12G West 119th Street

New York, N.Y. 10027

Of Counsel:

J oseph L. R auh , J r.

1001 Connecticut Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 2003G

S tephen P. B erzon

1520 New Hampshire Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

P eter D. P oos

Mexican American Legal

Defense and Educational

Fund

145 Ninth Street

San Francisco, California 94101

(415) 8G4-G000

A lbert H . Meyerhoff

R alph S antiago A bascal

California Rural Legal

Assistance, Inc.

115 Sansome Street, Suite 900

San Francisco, California 94101

(415) 421-3405

Charles R. Lawrence III

University of San Francisco

School of Law

San Francisco, California 94117

(415) GGG-G986

J eanne Miner

National Lawyers Ouild

853 Broadway

New York, N.Y. 10003

(212) 2G0-13G0

Bi .ack A merican

Law S tudent A ssociation

/

la

APPENDIX A

July 18,1973

Mr. Allan P. Bakke

1083 Lily Avenue

Sunnyvale, California 940S6

Dear Allan:

Thank you for your thoughtful letter of July 1. I must

ap„ ,og t for not answering your original eommunmaUon

of May 30 sooner, it arrived amidst the preparations foi

our second commencement, the start of the summer quart

for continuing students, and a compheated aria> of m -

agement changes within the medical school s admimstra

tion.

Your first letter involves us both in a situation that is

i aU-ifnl for im as for you. Yrou did indeed fareperhaps as painful loi us as 101 >uu.

well with our Admissions Committee and were rated

deliberations among the top ten percent of our 2 oOO aph-

cants in the 1972-73 season. We can admit hi one!tan

dred students, however, and thus are faced with the d

tressing task of turning aside the applications of *0™

markahly able and well-qualified mdiyiduais, including,

this year, yourself. We do select a small group of altei na

tive candidates and name individuals from that group to

positions in the class made vacant by withdrawals, if any

The regulations of the University of California do not

permit ns to enroll students in the medical school on any

other basis than full-time, however, so that even your sug

gestions for adjacent enrollment cannot he enacted.

5 Your dilemma—our dilemma, really-seems in your mind

to center on your present age and the Poss'ble t ̂ ri“ en

influence this factor may have m our consideration of >(

application. I can only say that older applicants have suc

cessfully entered and worked in our curriculum and that

your very considerable talents can and will override any

questions of age in our final determinations.

2a

I think the real issue is what to do now. I have two sir

gestions, one related to your own candidacy here, the otli.

addressed to the matters raised in your second letter. Fir>

I would like you to apply a second time to Davis, und

the Early Decision Plan. We are participating in I!

AMCAS system this year and to apply as an EDP cam!

date you need only so indicate on the appropriate AMCA

form and agree to apply only to Davis until a decision

reached, no later than October first. The advantages ar

early and thorough evaluation and interview with a eo

respondingly prompt decision either to offer you a pla,'

or to defer your application for later consideration as

regular applicant. In the event that our decision is the hr

tei, you might consider taking my other suggestion whic

is then to pursue your research into admissions policl

based on quota-oriented minority recruiting. The reasn

that I suggest this coordination of activities is that if or.

decision is to deter your application for admission, y<v

may then ask AMCAS to send it elsewhere as well. You

interest in admission thus would become more generalize

and your investigation more pointed.

I am enclosing a page that describes the basic approa.

used by the medical school at Davis in evaluating appl

cants who have “ minority’’status. I don’t know whetln

you would consider our procedure to have the overtones'

a quota or not, certainly its design has been to avoid an

such designation, but the fact remains that most applicant

to such a program are members of ethnic minority group

It might be of interest to you to review carefully the cm

rent suit against the University of Washington School '

Law by a man who is now a second year student there la;

who was originally rejected and brought suit on the ver

grounds you outlined in your letter. While the case is o'

appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court at this time, the imnif

diate practical result two years ago was a lower coin"!

3a

ordered admission for the plaintiff. The case, De Funis vs.

Odegaard, can be researched in a law library at your con

venience: a summary is enclosed. I might further urge that

you correspond with Prof. Robert Joling, a member'of the

faculty at the University of Arizona College of Medicine

interested in medical jurisprudence. An attorney, Joling

can give you perhaps the best indication of the current

legal thinking on these matters as they pertain to medical

schools. Associate Dean Martin S. Begun of the New York

University School of Medicine can also assist in your re

search.

I hoPe that tliese thoughts will be helpful, and that you

will consider your next actions soon. I am enclosing an

application request card for your use, should you decide to

make a second shot at Davis.

Sincerely,

P eter C. S toraxdt

Assistant to the Dean

Student Affairs/Admissions

t

4a

Sunnyvale, California 94086

1088 Lily Avenue

August 7, 1973

Peter C. Storandt

Office of Student Affairs

University of California, Davis

Davis, California 95G16

Dear Mr. Storandt:

Thank you for taking time to meet with me last Friday

afternoon. Our discussion was very helpful to me in con

sidering possible courses of action. T appreciate your pro

fessional interest in the question of the moral and legal

propriety of quotas and preferential admissions policies:

even more impressive to me was your real concern about

the effect of admission policies on each individual appli

cant.

You already know, from our meeting and previous cor

respondencc, that my first concern is to be allowed to study

medicine, and that challenging the concept of racial quota-

is secondary. Although medical school admission is impor

tant to me personally, clarification and resolution of th

quota issue is unquestionably a more significant goal be

cause of its direct impact on all applicants.

The plan of action I select should be designed to accom

plish two purposes—to secure admission for me and t

help answer the legal questions about admissions practice

which show racial preference.

Two action sequences which appear to have some pro.-

pect of satisfying both requirements are outlined below.

Plan A

1. Apply to Davis under the Early Decision Program.

5a

2. If admitted, I would retain standing to sue Stanford

and UCSF in order to officially pose the legal ques

tions involved. With my admission assured, I could

proceed directly to a filing of pleadings, bypassing

the possible compromise of admitting me to avoid

the inconveniences of legal proceedings. Hopefully,

I would he able to obtain legal or financial assistance

to sustain these proceedings.

Plan B

1. Apply to Davis under the Early Decision Program.

2. Confront Stanford in August or September, 1973,

attempting to secure immediate admission as an al

ternative to a legal challenge of their admitted racial

quota.

3. If admitted to Stanford, then sue Davis and UCSF.

If also admitted to Davis, sue only UCSF.

Stanford is chosen for this confrontation because of

their greater apparent vulnerability. Stanford states cate

gorically that they have set aside 12 places in their entering

class for racial minorities.

Two principles I wish to satisfy in choosing my course

are these:

1. Do nothing to jeopardize my chances for admission to

Davis under the E.D.P.

2. Avoid actions which you, Mr. Storandt, personally or

professionally oppose. My reason for this is that

you have been so responsive, concerned, and helpful

to me.

Plan B has one potential advantage over plan A. It con

tains the possibility, probably remote, of my entering med

ical school this fall, saving a full year over any other ad-

i

6a

missions possibilities. Because my veterans’ educational

benefits eligibility expires in September, 1970, admission

this year would also be a great financial help.

Mr. Storandt, do you have any comments on these pos

sible actions? Are there any different procedures you would

suggest? Would Davis prefer not to be involved in any

legal action I might undertake, or would such involvement

be welcomed as a means of clarifying the legal questions

involved ?

Although they may not be relevant to the legality of pref

erential minority admissions, I would like to learn the an

swers to several questions. They relate to how well those

selected under “ minority” admissions programs perform.

1. Do they require special tutoring?

2. Do they take longer to complete medical school and

therefore use more resources?

3. Do they perform adequately on national evaluation

examinations?

Are statistics like these available as public records, and

if so, where can one obtain them?

If it is more convenient to phone than to write, should

you have any comments or answers for me, you may reach

me any day after 4:30 PAL at my home (408) 246-33o(i. 1

will be happy to accept charges for any such call.

Again, thank you for the considerable time and effort

you have spent listening to my inquiries, informing, and

advising me. If you are in tbe Sunnyvale area and would

like to visit us, Judy and I would be happy to have you.

Sincerely yours,

/ s / A llan P. B akke

Allan P. Bakke

7a

August 15, 1973

Mr. Allan P. Bakke

1088 Lily Avenue

Sunnyvale, California 94086

Dear Allan:

Thank you for your good letter. It seems to me that you

have carefully arranged your thinking about this matter

and that the eventual result of your next actions will be of

significance to many present and future medical school

applicants.

1 am unclear about the basis for a suit under your Plan

A. Without the thrust of a current application for admis

sion at Stanford, I wonder on what basis you could develop

a case as plaintiff; if successful, what would the practical

result of your suit amount to? With this reservation in

mind, in addition to my sympathy with the financial exig

encies you cite, I prefer your Plan B, with the proviso that

you press the suit—even if admitted—at the institution of

your choice. And there Stanford appears to have a chal

lengeable pronouncement. If yon are simultaneously ad

mitted at Davis under EDP, you would have the security

of starting here in twelve more months.

Your questions about the actual academic performance

of those admitted under “ minority” admissions programs

have been asked frequently, as you might imagine, and have

received attention in many circles, I would suggest re

searching these issues in the Journal of Medical Education,

where an extensive bibliography has accumulated in the

last few years. At Davis, such students have not required

“ official” tutoring, although they and many of their class

mates have organized an impressive series of study ses

sions during the year. A few of them—perhaps ten percent

—have taken longer than four years to complete the M.D.

degree (but not more than one year longer). Their per

formance on the first part of the National Board of Med-

t

8a

ical Examiners’ test series lias been mixed—half of tho

current third year class “ minority” students failed to

qualify as passing the first time they took the examination;

all of our “ minority” students have passed the appropriate

levels of the test by the time of their graduation. Part two,

based on the clinical years of a medical education, seems

to pose no such problems for these students.

I am sure that you can recognize the need for careful

evaluation of these facts and opinions. 1 will be interests

to learn of your view of them, particularly after you hav

been able to read some studies done on a national and

regional basis. Is there a medical library reasonably clost

to you that you could use in working up your research 011

this subject?

With best wishes,

Sincerely,

P eter C. S torandt

Assistant to the Dean

Student Affairs/Admissions

9 a

APPENDIX B

U niversity oe California, D avis

division of the sciences

BASIC TO MEDICINE

DEPARTMENT of HUMAN PHYSIOLOGY

SCHOOL OF MEDICINE

DAVIS, CALIFORNIA 95616

January 4, 1977

Editor

The Sacramento Dee

21 st and Q Streets

Sacramento, CA 95813

Dear Sir:

The article entitled, “ U.C. Davis Suit Has National lm-

nact” bv N.Y. Times News Service writer Gene I. Maeiolt

(Sacramento Bee, Jan. 2, 1977) contains a number of inac

curacies and misconceptions which have repeatec y ap

peared in news accounts of the special admissions program

at UCD Medical School, as well as m the public record o

the Balike case. One of the most flagrant misstatements o

fact which has recurred is that UCD has had a strict quota

of 16% of the places reserved for minority students out of

1 00 available in each freshman class. The special ad-

missions program as it was originally authorized by the

medical school faculty in 1970, set 16% as a goal toward

which the admissions committee was to work m admitting

disadvantaged students. The difference between a goal and

a o t t a may seem to he a minor academic point to the pub

lic hut it most assuredly is not an insignificant one. It is

actually one of the crucial points on which the judicial de

cision in the Balike case was based. Not only was it the

intent of the faculty that 16% be a goal, but m practice the

admissions committee has viewed it as a goal, since two o

frooiimpn classes, one of which was the class for which

l

j

10a

15 students by way

rogram was specif-

i minorities. In the

program, no mention

Bakke sought admission, enrolled o

of the special program.

Another misconception is that t