Patterson v. The American Tobacco Company Opinion

Public Court Documents

May 7, 1975 - February 23, 1976

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Patterson v. The American Tobacco Company Opinion, 1975. 152653dd-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0896c91e-d3ec-42cf-92d8-4fcad29c5740/patterson-v-the-american-tobacco-company-opinion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

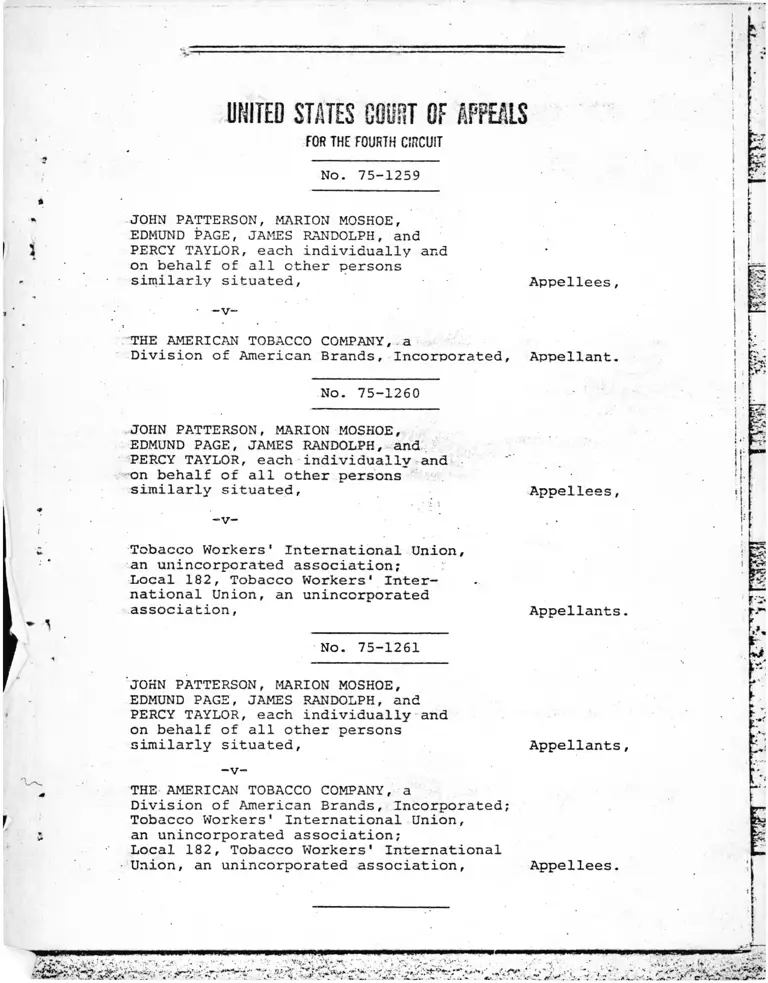

UNITED STATES GOilITT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 75-1259

JOHN PATTERSON, MARION MOSHOE,

EDMUND PAGE, JAMES RANDOLPH, and

PERCY TAYLOR, each individually and

on behalf of all other persons

similarly situated, Appellees,

THE AMERICAN TOBACCO COMPANY, a

Division of American Brands, Incorporated, Appellant.

No. 75-1260

JOHN PATTERSON, MARION MOSHOE,

EDMUND PAGE, JAMES RANDOLPH, and

PERCY TAYLOR, each individually and

on behalf of all other persons

similarly situated, Appellees,

-v-

Tobacco Workers' International Union,

an unincorporated association;

Local 182, Tobacco Workers* Inter

national Union, an unincorporated

association, Appellants

No. 75-1261

JOHN PATTERSON, MARION MOSHOE,

EDMUND PAGE, JAMES RANDOLPH, and PERCY TAYLOR, each individually and

on behalf of all other persons

similarly situated, Appellants

-v-

THE AMERICAN TOBACCO COMPANY, a

Division of American Brands, Incorporated;Tobacco Workers' International Union,

an unincorporated association;

Local 182, Tobacco Workers' International

Union, an unincorporated association, Appellees.

EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITYCOMMISSION, Appellee,

-v-

Local 18 2, Tobacco Workers'International Union (AFL-CIO), Appellant.

No. 75-1263

EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITYCOMMISSION, Appellee,

-v-

AMERICAN BRANDS, INC., d/b/aAmerican Tobacco Company, Inc., Appellant.

Appeals from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Virginia, at Richmond. Albert V.

Bryan, Jr., District Judge.

(Argued May 7, 1975. Decided Feb. 23, 1976

Before WINTER, BUTZNER, and WIDENER, Circuit Judges.

Henry L. Marsh, III; (S. W. Tucker; John W. Scott, Jr.;

Randall G. Johnson; Hill, Tucker and Marsh; Jack Greenberg;

Elaine R. Jones; Barry L. Goldstein; and Morris J. Bailer

on brief) for John Patterson, et al.; Henry T. Wickham

(John F. Kay, Jr.; Kenneth V. Farino; Mays, Valentine,

Davenport and Moore; Chadbourne, Parke, Whiteside and

Wolff; Paul G. Pennoyer, Jr.; Arnold Henson; Bernard W.

McCarthy; and Bernard J. Dushman on brief) for The Ameri

can Tobacco Company and American Brands, Incorporated;

(cont.)

Herbert L. Segal (Irwin H. Cutler, Jr.; Walter Lapp

Sales; Segal, Isenberg, Sales and Stewart; Jay J. Levit

Stallard and Levit; and James F. Carroll on brief for

Tobacco Workers' International Union and Local 182);

Margaret C. Poles, Attorney, Equal Employment Oppor

tunity Commission, (Julia P. Cooper, General Counsel;

Joseph T. Eddins, Associate General Counsel; and

Beatrice'Rosenberg and Charles L. Reischel, Attorneys,

on brief) for the Equal Employment Opportunity .Commis

sion.

BUTZNER, Circuit Judge:

These appeals and cross appeals question certain

provisions of a judgment entered in consolidated actions

brought by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and

several black employees of the American Tobacco Co. against

the company, the Tobacco Workers International Union, and

its Local 182. The case concerns the application of Title

VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 [42 U.S.C. § 2000e et

seq.] and 42 U.S.C. § 1981 to redress race and sex discrim-

1

ination in working conditions. Following is a summary of

the district court's decision and our disposition of the

assignments of error:

I. The district court defined the class of black

employees as those, whether currently employed or not, who

-worked on or after July 2, 1965, the date Title VII became

effective. It found no discrimination in hiring but ruled

that the company and the labor organizations had engaged in

unlawful employment practices by racial discrimination in

the promotion of employees. It ordered American to institute

company-wide seniority, eliminate certain lines of progression

1. 42 U.S.C. § 2000e2 prohibits both employers and

labor organizations from engaging in employment

practices that discriminate on the basis of race

or sex.

42 U.S.C. § 1981 assures all persons the same

right to make and enforce contracts as is enjoyed by

white citizens.

-4-

from lower to higher paying jobs, post definite job descrip

tions, grant back pay, and adjust pensions and profit

sharing plans in amounts to be determined at a subsequent

hearing. The court also ordered that white incumbents be

bumped from jobs for which senior black employees were

qualified.

Neither party has assigned error to the court's

finding of no discrimination in hiring. We find no error in

the designation of the class. We affirm the finding of

discrimination in promotions and approve the relief ordered

by the court, except for provisions of the judgment dealing

with company-wide seniority and bumping.

II. The district court ruled that the EEOC was

empowered to bring suit to eliminate discrimination against

women, although the initial charge dealt only with discrimi

nation against men. It defined the class of aggrieved women

in terms similar to those used to describe the class of

black employees. The court found discrimination in pro

motions but not in hiring, and it ordered relief similar to

that afforded black employees.

On these issues we affirm the district court,

modifying only its grant of relief.

III. The district court found discrimination in

the selection of supervisors and ordered the company to

prepare written job descriptions and objective criteria

-5-

;

i-

Vs

f .

r

* ,Av * * * ■ i - . u . . - '• - •»*> . - . j f •• *

J

for appointments. It also ordered preferential hiring of

blacks and women to fill supervisory vacancies.

We affirm these aspects of the court's judgment

except for those dealing with preferential- hiring.

IV. The district court held that the actions were

timely filed, that the statute of limitations for an action

brought under § 1981 is five years, and that the statute is

not tolled by filing a charge with the EEOC. It also held

that back pay for discrimination against women should accrue

from two years before the charge was filed.

Except for the application of the five-year

statute of limitations and the accrual of liability for the

women's back pay, we affirm these rulings. The proper

limitation, we hold, is two years, and.the accrual date for

back pay must be reexamined in light of EEOC v. General

Electric Co., ____F.2d ____, No. 74-1974 (4th Cir. 1975),

which was decided after the district court wrote its opinion.

I

American operates three facilities in Richmond,

Virginia. The "Virginia Branch" makes cigarettes; the

"Richmond Branch" makes pipe tobacco; and the "Richmond

Office" keeps accounts and records for both branches.

Approximately 250 of the 1,280 employees at both branches

are black, and in the Richmond office 13 of the 62 employees

are black. In each branch the prefabrication department

blends and prepares tobacco before sending it to the fabrication

-6-

department, which manufactures the finished products. Workers

in prefabrication generally earn less than those in fabrication,

and .most employees at the Richmond branch make less than

those at the Virginia branch.

Before 1963 the union and the company overtly

segregated employees by race with respect to job assignments,

cafeterias, restrooms, lockers, and plant entrances. White

employees were represented by Local 182 of the Tobacco

Workers International Union, while black employees were re

presented by Local 216. Blacks were generally assigned to

positions in the prefabrication departments. The higher

paying jobs in fabrication were largely reserved for white

employees. Each department had its own seniority roster, on

which promotions depended. Employees could not transfer

from one department to another without forfeiting their

seniority. •

In September 1963 the black union was assimilated

by the white Local 182 to comply with an executive order

relating to the government's purchase of supplies. Simul

taneously, the company abolished departmental seniority, but

it continued to maintain separate rosters at the two branches.

The 1963 changes did not eliminate racial discrimination

from the company's promotion practices. The district court

found that until 1968 the company utilized a system of

unwritten qualifications which denied black employees access

to the higher paying jobs at the Virginia branch. For

certain positions an employee had to be familiar with the

duties of the new job in the opinion of his supervisor.

Also, he had to work a minimum number of hours on a temporary

basis to qualify as an operator of a making or packing

machine. Consequently, black employees not working in

proximity to the higher paying jobs had limited opportunity

to qualify, regardless of their seniority. Combined with

static employment in the tobacco industry, this system

allowed little advancement of black employees from jobs in

prefabrication to those in fabrication. Indeed, from 1963

to 1968 there was an increase of only four blacks in the

fabrication department at the Virginia branch.

The Richmond branch had no qualification restric

tions on promotions. Instead, supervisors canvassed employees,

seeking the senior worker willing to fill a vacancy. There

were, however, no written job descriptions. This system

provided slight opportunity for black employees to move from

prefabrication to fabrication, and from 1963 to 1968, there

was an increase of only six black employees in the latter

department. As of 1968, only three of the 26 machine operators

were black.

In January 1968 the company discontinued its

qualifications system. Instead, it posted vacancies and

promoted the senior employee who bid for the job. The district

court found that this innovation was "facially fair and

neutral" but ordered that it be implemented by posting

written job descriptions. Furthermore, the district court

found that access to certain jobs was barred to black

employees by lines of progression and the maintenance of

separate seniority rosters for each branch.

Although the company and the union have taken

steps in recent years to correct some of the inequalities of

the past, the lines of progression, the lack of definite

written job descriptions, and barriers to transfer between

the branches remain impediments to fair and neutral employ

ment practices. Much must still be done to eradicate any

taint of racial discrimination at the plant. The most

recent figures available indicate that as of the end of

1973, more than 80 percent of all the employees in the

Virginia branch's prefabrication department were black,

while in the fabrication department only-about 14 percent

were black. At the Richmond branch, black employees'

penetration into the fabrication department was greater,

with blacks comprising more than 38 percent of the workforce.

But the lower paying prefabrication department remained

almost completely segregated; 92 percent of its employees

were black. These figures provide ample support for the

district court's findings that "[t]raditionally, at both

branches there have been more blacks in the prefabrication

• department than whites, and more whites in the fabrication

department than blacks."

The company emphasizes that from July 2, 1964, to

March 1, 1974, 25 percent of all employees promoted and 20

percent of those advanced to operate automatic machinery at

the Virginia branch were black. Also, since the initiation

in January 1968 of the posting and bidding procedure, 51.5

percent of the successful bidders have been black. These

gross figures, however, include promotions in both prefabri

cation and fabrication departments, and, while laudable,

they do not address the crucial issue of the case— the entry

of black employees into the historically white fabrication

department. Apart from the fact that many of these pro

motions were made after charges were filed with the EEOC,

the company's reliance on the overall promotion rate in both

departments misses the mark because blacks have always been

promoted in the historically black prefabrication department.

Moreover, as late as 1973, of the approximately 200 hourly-

paid, non-craft job classifications at Virginia, 18 had never

been held by whites and 10 had never been held by blacks.

Even more rigid segregation characterized the Richmond

branch; of the approximately 43 hourly—paid, non—craft job

classifications, 21 had never been held by whites and nine

had never been held by blacks.

We conclude, therefore, that the record amply

supports the district court’s finding that after the effective

date'of Title VII the company and the union discriminated in

the promotional policies of their bargaining agreements and

practices. Tested by familiar standards, the court's findings

2

must be sustained.

We next consider the assignments of error that

challenge the relief ordered by the district court. The

directive that definite job descriptions must be provided in

order to implement a fair method of promotion was clearly

warranted. Cf^ Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Machine Co.,

457 F.2d 1377 (4th Cir. 1972).

In those jobs that were filled according to lines

of progression, an employee had to work, in the first job

before proceeding to the next, and so on up to the highest

job in the line. Most of these jobs were in the fabrication

departments. Since black employees had been largely excluded

from the fabrication departments, they held few jobs in most

of these lines and could not advance despite their seniority.

In this respect, the lines of progression perpetuated the

effects of past discrimination in a manner similar to the

formerly segregated departmental seniority rosters. On the

2. Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 52(a) pro

vides in part that "[fjindings of fact [by the court] shall not be set aside unless clearly

erroneous . . . "

- 11-

basis of its evaluation of conflicting expert testimony, the

district court held that only three of the nine lines are

3

ju-stified by business necessity. For the others, alternative

means such as on-the-job training are available to provide

competent workers.

Addressing the discrimination caused by lines of

progression, we pointed out in Robinson v. Lorillard Corp.,

444 F.2d 791, 799 (4th Cir. 1971), that the vagaries of

chance inherent in this promotion system might bar a qualified

worker from advancement for years, although he could learn

to perform the job competently in a relatively short time.

To deal with such situations, we formulated the following

standard for ascertaining whether a condition of employment

-was justified by business necessity:

”[T]he applicable test is not merely

whether there exists a business purpose

for adhering to a challenged practice.

The test is whether there exists an

overriding legitimate business purpose such that the practice is necessary to

the safe and efficient operation of the

business. Thus, the business purpose

must be sufficiently compelling to over

ride any racial impact; the challenged

practice must effectively carry out the

business purpose it is alleged to serve;

and there must be available no acceptable

alternative policies or practices which

would better accomplish the business pur

pose advanced, or accomplish it equally

well with a lesser differential racial

impact." 444 F.2d at 798.

3. The three positions for which lines of progression

can be maintained are adjuster, overhaul adjuster,

and adjuster prefabrication.

-12-

* *

l i

!*t

lt

i»ii

j

Measured by this test, the district court's elimination'

of the six lines of progression was correct.

The district court also ordered a single seniority

roster for the Virginia and Richmond branches to enable

employees in each branch to bid for posted jobs in 'the

other. The order is designed to correct the present effect

of past discrimination, which denied black employees entry

into the higher paying jobs of the fabrication departments,

particularly at the Virginia branch. For example, under the

present method of job assignments, a black employee hired in

1955 at the Richmond branch prefabrication department has no

realistic opportunity to secure a higher paying job in the

formerly white Virginia fabrication department because he

cannot transfer his company seniority to the Virginia branch.

If he seeks a new job there, he must forfeit his seniority

and start as a new hire.

The district court correctly found that the denial

of transfer between the branches without retention of

company seniority perpetuates the effect of past discrimination.

We believe, however, that the relief ordered by the district

judge is broader than necessary. Title VII does not require

the company or the union to forego the benefits of separate,

nondiscriminatory seniority rosters. "Application of the

Act normally involves two steps. First, identification of

the employees who are victims of discrimination, and second,

prescription of a remedy to correct the violation disclosed

-13-

The Act does not require the applicationby the first step,

of the remedy to employees who are not subject to discrim

ination." United States v. Chesapeake and Ohio Ry., 471

F.2d 532, 593 (4th Cir. 1972). The only employees who

suffered discrimination were blacks who could not obtain

jobs in the fabrication departments because of their race.

Consequently, they are the only employees who should be

allowed to transfer under the posting and bidding system

from one branch to' the fabrication department in the other

branch on the basis of their company seniority. Black

employees need not be allowed to transfer with company

seniority to jobs in prefabrication, because the^ were

never barred from these jobs in the first place. Similarly,

white employees seeking transfers are not entitled to utilize

company seniority, because they were never barred from fabrica

tion departments. Finally, no employee hired after the

cessation of discrimination in job assignments need be allowed

to transfer with seniority intact. See, e.g., Russell v.

American Tobacco Company, ____F.2d ____, No. 74-1650 (4th

Cir. 1975); Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791 (4th

Cir. 1971); Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc., 279 F.Supp. 505

(E.D. Va. 1968).

The company and the union assert that this case is

distinguishable from departmental seniority cases like

Robinson because the Richmond and Virginia branches are in

different locations. They emphasize that the branches make

i

\

I

\

-14-

j $

.1 &

r

!

different products, have different managements, hire separately,

•and are some distance apart. For these reasons, they argue,

the case falls within 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(h), which provides

that:

"Notwithstanding any other provision of

this subchapter, it shall not be an un

lawful employment practice for an employer

to apply different standards of compensa

tion, or different terms, conditions, or

privileges of employment pursuant to a

bona fide seniority or merit system . . .

or to employees who work in different loca

tions, provided that such differences are

not the result of an intention to discrimi

nate because of race, color, religion, sex,

or national origin . . . . "

Noting that neither the Act nor the regulations

define the statutory term "employees who work in different

. locations," we recently construed § 2000e-2(h) in Russell

v. American Tobacco Co., ____F.2d ____, No. 74-1650

(4th Cir. 1975) . We pointed out that the labor market

is the most important factor in determining whether a

company's employees work in different locations. A company

operating two or more of its plants with employees who are

from the same geographic area and who are unskilled or

possess the same skills can assign an applicant to an entry

level position in either plant. Therefore, employees the

company hired from the same labor market would not generally

fall within the statutory class of "employees who work in

different locations." £ ' :

M-15-

On the other hand, even though a company's plants

are in the same city, as they are here, their proximity does

not conclusively show that they are in the same location.

If one plant requires labor possessing skills different from

those of workers at another plant, the company cannot draw

from the same labor market to man its plants. Under these

circumstances, employees would work at different locations,

even though they reside and work in the same geographic

area.

American hires employees for both branches from

the same labor market. The branches are only a few city

blocks apart. There are entry level jobs at both places

that require neither particular skills nor experience, and

jobs in fabrication can be filled just as well by trans

ferees as by persons hired off the street.

Other facts support the district court's finding

that these plants are not in different locations. The same

bargaining agreement covers employees at both plants, and

the company has contractually reserved the right to shift

employees from one plant to the other without depriving them

of seniority. The Richmond office, located in a building at

the Virginia branch, serves both branches, and the Virginia

branch ships the Richmond branch's products.

There is another reason why the exemption granted

in § 2000e-2(h) is not available to American. As we noted

-16-

V it

in Russell, supra, slip op. at 10, that section contains a

proviso that restricts its application to situations where

differences in the conditions of employment "are not the

result of an intention to discriminate." Past intentional

segregation that is perpetuated by a company’s seniority

system precludes it from claiming that its system is bona

fide within the meaning of § 2000e-2 (h.) , Robinson v. Lorillard

Corp., 444 F.2d 791 (4th Cir. 1971). Similarly, "where

present differences in working conditions are remnants of

past intentional discrimination, the proviso of § 2000e-2(h)

bars a company from defending its employment practices on

the ground that its employees work in different locations."

Russell v. American Tobacco Co., ____ F.2d ____, ____, No.

74-1650 (4th Cir. 1975), slip op. at 11.

We therefore affirm the district court on this

issue but note that on remand it should vacate the provision

of its judgment requiring a single seniority roster for both

branches. It should substitute an order allowing those

black employees who formerly could not obtain jobs in the

fabrication departments because of discrimination to utilize

their company seniority to bid for such jobs in the fabrica

tion department of either branch. Of course, an employee

who transfers must have the capacity to perform the job

after receiving a reasonable amount of training.

-17-

r-ffvI

&

Milll

Title VII nor its legislative history requires bumping in

this case.

Relief under § 1981 is limited to correcting

racial discrimination. See Delavigne v. Delavigne, No.

75-2203, ____ F.2d ____ (4th Cir. 1976); Willingham v. Macon

Telegraph Publishing Co., 482 F.2d 535, 537 n. 1 (5th Cir.

1973). But apart from this, Title VII and § 1981 provide

complementary remedies for employment discrimination, Johnson

v. Railway Express Agency, Inc., 421 U.S. 454, 459-60 (1975).

Although the legislative history of Title VII cannot support

a decision that bumping relief is unavailable under § 1981,

the pragmatic considerations we advance apply with equal

force to the § 1981 claim. Moreover, "in fashioning a

substantive body of law under § 1981 the courts should, in

an effort to avoid undesirable substantive law conflicts,

look to the principles of law created under Title VII for

direction." Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works of International

Harvester Co., 502 F.2d 1309, 1316 (7th Cir. 1974). For

these reasons, we hold that bumping relief is not available

to American's black employees under § 1981.

On remand, therefore, the district court should

modify its decree to eliminate bumping, but it should take

steps to assure that back pay will be computed to include

compensation for the entire time that a minority employee is

i denied a promotion for which he or she is qualified by

I

A*

)

continuing jurisdiction over the case and make periodic back

pay awards until the workers are promoted to the jobs their

seniority and qualifications merit. Or perhaps counsel and

the court can devise some other convenient method of taking

all the effects of past discrimination into account. In any

event, the compensation must include, as the district court

properly noted, increments for pensions and profit sharing.

Compensatory pay and adjustment of benefits provide

monetary relief for discrimination against minority employees

but do not afford the satisfaction that comes from being

promoted to a more responsible job. Nevertheless, such an

intangible benefit does not justify injunctive relief mandating

bumping. Weighed against a minority employee's sense of

achievement are the harm that demotion will cause to incumbents

who have done no wrong and the disruption of the company's

business that bumping entails. The survey of employees

referred to in footnote 8, supra, indicates that 39 minority

employees are seeking jobs held by 8 white men and 31 other

minority employees. This survey, however, does not prove

that the employees seeking different jobs were motivated

even in part by non-monetary factors, for it was conducted on

the assumption that bumping was the only way they could

receive better pay and fringe benefits. Since full monetary

compensation and the removal of barriers to promotion provide

adequate relief to minority employees without disruption to

other employees and management, we conclude that neither

-25-

I

economy and making persons whole for injuries suffered

through past discrimination." 422 U.S. at 421.

To satisfy these objectives, back pay must be i

allowed an employee from the time he is unlawfully denied a

promotion, subject to the applicable statute of limitations,

un._il he actually receives it. Some employees who have been

victims of discrimination will be unable to move immediately )

into jobs to which their seniority and ability entitle them.

The back pay award should be fashioned to compensate them

until they can obtain a job commensurate with their status.

This may be accomplished by allowing back pay for a period

commencing at the time the employee was unlawfully denied a

position until the date of judgment, subject to the applicable

statute of limitations. This compensation should be supple

mented by an award equal to the estimated present value of

lost earnings that are reasonably likely to occur between

the date of judgment and the time when the employee can

assume his new position. See Bush v. Lone Star Steel Co.,

373 F.Supp. 526, 538 (E.D. Tex. 1974); United States v.

United States Steel Corp., 371 F.Supp. 1045, 1060 n. 38

10

(N.D. Ala. 1973). Alternatively, the court may exercise

This measure of compensation is analogous to that awarded in an ordinary tort case, where compensation

is assessed for one's loss of earnings whether the loss

occurs before or after the judgment is entered. The

analogy is apt because a statutory action attacking

discrimination is fundamentally for the redress of a tort. See Curtis v. Loether, 415 U.S. 189, 195

is no reason to suppose that this process will soon abate.

Bumping could mean that employers and workers would likely

have their businesses and their working lives rearranged by

court decrees from time to time, as various unlawful employment

practices are identified. See generally Note, Title VII,

Seniority Discrimination, and the Incumbent Negro, 80 Harv.

L. Rev.. 1260, 1274-75 (1967).

V • Finally, although Congress did not intend the Act

i '

to be used as a vehicle for displacing incumbents, it did

not leave the victims of discrimination without a remedy.

Section 2000e-5(g) expressly authorizes a district court to

: award them back pay. While an employee who has been unlawfully

denied a promotion must await a vacancy before advancing, he

[ need not prove that a vacancy exists in order to qualify for

back pay. Hairston v. McLean Trucking Co., 520 F.2d 226

I (4th Cir. 1975); Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791

(4th Cir. 1971).

In Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 408

i (1975), the Court explained the standards a district court

should follow in awarding back pay to employees who "havei '*

lost the opportunity to earn wages because an employer has

f

| engaged in an unlawful discriminatory employment practice."

The Court said that the back pay provision must be applied|

{ in a manner that is "consonant with the twin statutoryI

objectives" of "eradicating discrimination throughout thei ;

* -23-

>■»

t

are not responsible for wrongdoing, undoubtedly would

. encounter more resistance than deferring their future

expectancies. As this case illustrates, bumping is an

unsettling process. Its domino effect adversely affects

employees who have done no wrong and who, indeed, may have

8been the victims of discrimination.

The effects of bumping are exacerbated by another

aspect of Title VII. The Act does not provide a definitive

catalogue of unlawful employment practices. Congress placed

this responsibility on the EEOC and, ultimately, the courts.

It soon became obvious that overt discrimination is not the

. 9only obstacle to equal employment opportunity. As a result

of litigation, many practices, procedures, or tests neutral

on their face, and even neutral in terms of intent" have

been exposed as discriminatory and condemned. See Griggs v.

Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, 430 (1971); United States v.

Dillon Supply Co., 429 F.2d 800, 804 (4th Cir. 1970). There

As part of its compliance with the district court1s decree, American conducted a canvass of its employees

to determine the effect of bumping. The results of

that survey are contained in a report filed with this

court to supplement the record. The report showed that

40 employees requested jobs to which their plant-wide

seniority would entitle them. One of these has already

obtained the job he requested. The others would bump

eight white male employees and 31 minority employees

out of the jobs they now occupy. We stayed the provision

of the decree that required bumping pending this appeal.

See generally Introduction, The Second Decade of

Title VII: Refinement of the Remedies, 16 Wm. & Mary L Rev. 433, 436-37 (1975).

- 22-

Since the Act should not be applied retroactively,

it is, of course, much easier to justify the retention of

incumbents who obtained their positions before the ei.fective

date of the Act than the retention of those who were unlaw

fully preferred after this date. Nevertheless, neither

Congress not the EEOC nor the courts have drawn a distinction

between pre-Act and post-Act incumbents. The reasons for

applying the Act uniformly are largely pragmatic. The

enactment of Title VII was the result of many concessions,

including the unequivocal assertion by proponents of the

legislation that it was not intended to be used to displace

7incumbent workers. A primary goal of Title VII is to

induce voluntary compliance by employers and unions. Section

2000e-5; see EEOC v. Hickey-Mitchell Co., 507 F.2d 944, 948

(8th Cir. 1974). Demoting employees, especially those who

6. This principle is established by the legislative

history. Senators Clark and Case, two of the bill's sponsors, circulated an interpretative memorandum

stating that Title VII's operation was "prospective and not retrospective . . . (T)he employer's obligation

would be simply to fill future vacancies on a non-

discriminatory basis." 110 Cong. Rec. 6992 (daily ed.

April 8, 1964), quoted in Quarles v. Philip Morris,

Inc., 279 F.Supp. 505, 516 (E.D. Va. 1968).

7. The Clark-Case memorandum, note 6 supra, states

that an employer "would not be obliged--or, indeed,

permitted— to fire whites in order to hire Negroes, or

to prefer Negroes for future vacancies, or, once

Negroes are hired, to give them special seniority

rights at the expense of white workers hired earlier."

110 Cong. Rec. 6992 (daily ed. April 8, 1964).

- 21-

■

. ...,.fV> ~-r

{has accepted this interpretation. Equally important, when

Congress was considering the 1972 amendments to Title VII,

5

it approvingly noted Papermakers' construction of the Act.

These precedents cannot be satisfactorily distin

guished on the ground that bumping would be required only

when the proof discloses a static industry that has few

vacancies. The difference between static and dynamic indus

tries is not always readily ascertainable because employment

opportunities fluctuate for many reasons over long and short

periods. Requiring bumping for static industries while

denying it in dynamic industries would introduce into the

i'k

.administration of the Act countless variables for which

Congress has made no provision.

4

4. E.g,, EEOC v. Detroit Edison Co., 515 F.2d 301

(6th Cir. 1975); United States v. N. L. Industries, Inc., 479 F.2d 354 (8th Cir. 1973); United States v.

Chesapeake & Ohio Ry., 471 F.2d 582 (4th Cir. 1972);

United States v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 446 F.2d

652 (2d Cir. 1971).

5. The section-by-section analysis of the Housebill states that "it was assumed that the present

case law as developed by the courts would continue

to govern the applicability and construction of

Title VII." Legislative History of Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, Government Printing

Office (1972) at 1844. Papermakers, of course, was

a prominent part of that case law.~

iTJ

branch and May 12, 1966, in the Virginia branch. Employment

in both branches decreased from 1953 to 1973 by approxi

mately 1300 workers.

One of the early questions about the construction

of Title VII was whether "present consequences of past

discrimination [are] covered by the act." Quarles v. Philip

Morris, Inc., 279 F.Supp. 505, 510 (E.D. Va.-1968). The

generally accepted answer is a qualified "yes": employers

and unions using pre-Act discriminatory practices to bar

employees from filling post-Act vacancies violate the Act.

Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791 (4th Cir. 1971);

Quarles, supra. On the other hand, Title VII has not been

construed to impose a duty to demote incumbents. In Local

189, United Papermakers and Paperworkers v. United States,

416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969), the court rejected the contention

that "allowing junior whites to continue in their jobs

constitutes an act of discrimination." Judge Wisdom, writing

for the court, said:

"The Act should be construed to prohibit

the future awarding of vacant jobs on the

basis of a seniority system that 'locks in'

prior racial classification. White incumbent workers should not be bumped out of

their present positions by Negroes with

greater plant seniority; plant seniority

should be asserted only with respect to new job openings. This solution accords

with the purpose and history of the legis

lation." 416 F.2d at 988.

Every appellate court to whom the issue has been presented

-19-

■>¥ -

The company and the union also assign error to the

part of the district court's order that allowed senior black

and female employees to bump junior employees from preferred

jobs. The court ordered immediate company—wide posting and

bidding on each non-supervisory job in the Richmond 'and

Virginia branches. The only qualifications for advancement

were to be seniority and a willingness to learn the job. To

.facilitate the bidding, the court ordered that job descrip

tions be posted. It further provided that employees who

were displaced by senior black or female workers, and

therefore had to move to lower paying jobs, must be paid as

much as they were in their former jobs. The court explained

the reason for this provision of its decree as follows:

"The present system of posting and bidding adopted in 1968 is fair, although it needs,

in the Court's view, further implementation.

As indicated in the findings of fact, how

ever, black and female employees in the Richmond Branch and the Virginia Branch have

been locked in their jobs as a result

of prior discriminatory practices. This is

because of the static condition of the tobacco industry generally, and American in

particular, and the advent of automation,

both of which have limited opportunities

for upward movement of present employees and for new hiring." (Appendix at 37-38.)

The court's description of the lack of employment opportunities

is well supported by the evidence. No new employees were

hired to fill jobs under jurisdiction of the union from

September 12, 1955, through June 12, 1964, in the Richmond

- 18 -

£

t> •I .} We affirm the district court's award of relief

against both the local and the International, except as

noted in Part II. The local acquiesced without protest in

the lines of progression. Not until 1968 did it negotiate

for the removal of the qualification.requirements for pro

motion. In 1968, 1971, and 1974, it proposed a company-wide

seniority system that would have allowed transfers between

’* branches. When the company declined, the union settled for

assurances of indemnity that would protect its treasury

against the claims of its members.

A union may not bargain away minority employees'

rights to equal treatment, see Robinson v. Lorillard Corp.,

444 F.2d 791, 799 (4th Cir. 1971), and, indeed, it must

"negotiate actively for nondiscriminatory treatment" of its

minority workers. Macklin v. Spector Freight Systems, Inc.,

478 F.2d 979, 989 (D.C. Cir. 1973); see also United States

v. N. L. Industries, Inc., 479 F.2d 354, 379 (8th Cir.

1973). The Supreme Court has recently emphasized the duty a

union owes to its minority members by pointing out that one

of the purposes of a back pay award is to spur unions, as

well as employers, to evaluate employment practices and

eliminate unlawful discrimination. Albemarle Paper Co. v.

Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 417-18 (1975). Tested by these principles,

the district court's imposition of liability on both the

local and the International was warranted by the law and the

i

( facts.

Nor can we accept the International's argument

that it should not be held liable because it was not respon-

* sible for the contracts negotiated by the local. The

evidence disclosed that a vice president of the Interna

tional acted as an "advisor" to the local, playing an active

role as the president's deputy in the 1971 and 1974 negotiations

for bargaining argeements. Moreover, the constitution of

the International provides:

"It shall be the principal duty of the

Local Union to secure satisfactory col

lective bargaining and working agreements

showing an adequate minimum wage and fair

working conditions for workers who have

become affiliated with the TWIU, provided,

however, that no collective bargaining and

working agreement shall be consummated

until first submitted to the general presi

dent who may approve or reject any proposed

agreement, and no such agreement can be

executed without the approval of the gen

eral president or his deputy."

The district court was not obliged to accept representations

of the vice president that contradicted the plain meaning of

this provision. The court properly concluded that the

International's approval of the bargaining agreement pursuant

to this provision made it jointly responsible with the

local. Cases dealing with an international union's exonera

tion of Liability to an employer are inapposite where its

duties to members of its local unions are at issue.

II

The EEOC's complaint contains allegations of

discrimination against women employees. The company contends

that the commission lacked authority to press this claim

-28-

because no female employee filed a charge. On the contrary,

the company points out, the only charge of sex discrimination

filed by a male employee. The district court overruled

the company's motion to dismiss this aspect of the case,

holding that the commission could institute the suit if its

investigation of the male employee's complaint disclosed

discrimination against women.

We affirm the district court. We recently decided

this issue adversely to the company's position in EEOC v.

General Electric Co., ____ F.2d ____, No. 74-1974 (4th Cir.

1975). The company's argument does not persuade us to

depart from the conclusions reached in that case.

On the merits of the claim of sex discrimination,

we uphold the district court's finding of liability. Because

the company's discrimination against women bears many similarities

to its discrimination against black employees, we need not

recite the evidence in detail. It is sufficient to note

that for many years the company overtly segregated jobs by

sex, discriminating against women, as the district court

found, "with respect to wage structure, departments, seniority

and hiring." Even after these practices were nominally

eliminated in 1963, their discriminatory effect was perpetuated

by- lack of definite job descriptions, lines of progression,

and obstacles to transfers. The court found that as recently

11. see Part IV infra for a discussion of the statute

of limitations with respect to this issue.

-29-

as 1973, 23 of the approximately 200 non-craft, hourly-paid

jobs at the Virginia branch had not been held by women, and

six had not been held by men. At the Richmond branch, 32 of

the 43 non-craft, hourly-paid jobs had not been held by

women, and six had not been held by men. The company has

not demonstrated that these segregated positions cannot be

filled by persons of the opposite sex. The court also found

that from 1967 through 1972 women had a lower mean income

than men with comparable seniority.

Again, the district court's findings are supported

by the evidence and cannot be set aside as clearly erroneous.

The relief the court afforded women is essentially the same

as the relief it granted black employees. Accordingly, we

approve the relief for women employees, subject, however, to

the same modifications of the court's decree that we mentioned

in Part I. This relief, however, can be granted only against

the company. The complaint against the union for sex discrim

ination must be dismissed for reasons we' will next discuss.

The commission's complaint names the company and

Local 182 as defendants. The commission acknowledged that s

it had not attempted to conciliate the charges with the

union before filing suit. While the suit was pending, it

made an offer to conciliate, which the union accepted. In

the course of discussion with the union, however, the

commission's representative conceded that he had no authority

to settle the suit. Understandably, the conciliation efforts

-30-

uf

were unsuccessful. The district court, viewing the lapse as

technical, held that the belated offer to conciliate and its

acceptance substantially complied with the Act.

The Act requires, however, that after receiving a

charge and before bringing a suit the commission must take

four steps: serve the charge on the employer and labor

organization, investigate the charge, determine that reason

able cause exists to believe the charge is true, and endeavor

to eliminate alleged unlawful employment practices "by in- 1

formal methods of conference, conciliation, and persuasion."

The 1972 amendments to Title VII empowered the commission to

sue if it is unable to secure an acceptable conciliation

13agreement. This provision of the Act has been construed

to create an express condition on the commission's power to

sue. Consequently, a suit brought by the commission before

|

iI

I

:

\j

|

i

»

Ii

attempting conciliation is premature. EEOC v. Hickey-

Mitchell Co., 507 F.2d 944, 947-48 (8th Cir. 1974); EEOC v.

E. I. DuPont de Nemours & Co., 373 F.Supp. 1321, 1333-34 (D.

Del. 1974); EEOC v. Westvaco Corp., 372 F.Supp. 985, 991-93

14

(D. Md. 1974) .

12. 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(b).

13. 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(f)(1).

14. We have held that the commission's failure to attempt

conciliation is not a jurisdictional bar to an employee's

action, because the employee cannot be charged with the

commission's failure to execute its statutory duties.

Russell v. American Tobacco Co., ____ F. 2d ____, ____,

No. 74-1650 (4th Cir. 1975); Johnson v. Seaboard Air

Line R.R., 405 F.2d 645 (4th Cir. 1968). These cases,

however, are inapposite where the commission's power

to sue is in question.

-31-

. V,.V • > / b ■ ' * V ■' ' *■: : ■

i .. . • : - . v ■ - ■ - : t < ' V *■’ ■ . .. . v ■:_ I V . • i •" f . - jfi * «y* W •' ■ • • - . . • • * .

‘- :4 <

*vV

i

We recently emphasized that the commission's

statutory duty to attempt conciliation is among its most

15

essential functions. It is particularly important for the

commission to attempt conciliation with a union when investi

gation discloses that provisions of a bargaining agreement

concerning seniority and job assignments are causing the alleged

unfair employment practices. Then the employees who enjoy

majority status are frequently more directly affected than

their employer by changes that will advance minority employees.

In such cases, the success of conciliation often hinges on the

union's response.

We do- not rule out the possibility that exceptional

circumstances may excuse a failure to attempt conciliation, but

that is not the case here. The union's willingness to negotiate

even after suit was brought tends to negate any suggestion that

timely conciliation of the sex discrimination charges would have

been unsuccessful. When it became apparent that the commission's

representative lacked authority to settle the case, the possi

bility of conciliation was dealt a severe blow by the very

circumstances Congress sought to avoid— commencement of a civil

action before attempting conciliation. Accordingly, we conclude

that the district court should have dismissed the part of the

commission's complaint which alleges that Local 182 caused the

company to discriminate unlawfully on the basis of sex.

15. EEOC v. Raymond Metal Products Co.,

_, No. 75-1007 (4th Cir. 1976).

-32-

F. 2d

m i - v

4> vTV *I

I

ftI

j' 111t •The district court also found that the company hadi

.< engaged in race and sex discrimination in appointing supervisors.

The evidence supports this finding. At both the Richmond• l

and Virginia branches, the entry level position for supervisory

personnel is assistant foreman. The company fills about 34

percent of the vacancies in this position by promoting

hourly employees; it fills the balance by hiring new applicants.

With no formal, objective, written standards for appointment,

the company relies in part on recommendations from the

union, which also lacks objective standards. Until 1963 the

company appointed only white males to supervisory posts, and

the enactment of Title VII failed to effect any immediate

change in this policy. At the Richmond branch, the first

black supervisor was appointed in 1966 and the second in

1971. As of June 1, 1973, there were only three, constitut

ing 9.6 percent of the supervisory force of 31. In 1967 the

company named its first female supervisor at the Richmond

branch. By 1973 two (6 percent) of the 31 supervisors were

women. At the Virginia branch, a black employee was promoted

to assistant foreman in 1963. In the next decade four more

were appointed, so that by 1973 7.24 percent of the 69

supervisors were black. The first female was not appointed

as a supervisor at this branch until 1972. Two more were

appointed by June 1, 1973.

Before the trial of the case, neither a black

employee nor a woman had ever been appointed to a supervisory

-33-r

• *tIposition at the Richmond office. The court noted, however,

|

that a vacancy existed, and the company proffered additional

evidence that as of November 1, 1974, the Richmond office

had one black supervisor and one white female supervisor on

a staff of eight.

The district court enjoined the company from

"implementing, maintaining, or giving effect to any criteria

utilized for the selection of supervisory personnel which is

designed to or has the effect of discriminating against

black or female candidates for supervisory positions." It

ordered the company to post job descriptions for these

positions and to devise objective criteria for selecting new

appointees. The propriety of these provisions of the court's

decree is well settled. See Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing

ii

r(>i

t

rI

i

Machine Co., 457 F.2d 1377, 1383 (4th Cir. 1972); Rowe v.

General Motors Corp., 457.F.2d 348, 358-59 (5th Cir. 1972).

We think, however, that on.remand the court's decree should

be enlarged to require the union to publish objective

criteria for making its recommendations for supervisory

appointments.

Finally, the district court ordered that vacancies

in the assistant foreman, foreman, and office supervisory

positions must be filled with qualified blacks and women,

except when none can be found, until the percentage of

blacks and women equals the percentage of these classes of

workers in the Richmond Standard Metropolitan Statistical

-34-

Area (SMSA). The company's attack on this provision of the

decree is two-pronged. First, it contends that Title VII

*

) condemns preferential hiring, especially when, as here, the

i

)

4

\

1 ,I*

!*

(1{t

j

ii

preferences are absolute. It relies primarily on § 703 (j)

of the Act, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(j), which provides in part:

"Nothing contained in this subchapter shall

be interpreted to require any employer . • .

to grant preferential treatment to any indi

vidual or to any group because of the race

. . . [or] sex . . . of such individual or

group on account of an imbalance which may

exist with respect to the total number or

percentage of persons of any race . . . [or]

sex . . . employed . . . in comparison with

the total number or percentage of persons of

such race . . . [or] sex . . . in anycommunity . . . or in the available work

force in any community. . . . "

This section plainly bans the use of preferential hiring to

change a company's racial imbalance that cannot be attributed

to unlawful discrimination. In Griggs v. Duke Power Co.,

401 U.S. 424, 430-31 (1971), the Court said:

"Congress did not intend by Title VII, how

ever, to guarantee a job to every person re

gardless of qualifications. In short, the

Act does not command that any person be hired

simply because he was formerly the subject of discrimination, or because he is a member of

a minority group. Discriminatory preference

for any group, minority or majority, is precisely and only what Congress has proscribed.

What is required by Congress is the removal

of artificial, arbitrary, and unnecessary

barriers to employment when the barriers op

erate invidiously to discriminate on the basis

of racial or other impermissible classification."

Uniformly, however, Title VII has been construed

to authorize district courts to grant preferential relief as

-35-

v -V- s > v ■ " j -*0

Rios v. Enterprise

I .

a remedy for unlawful discrimination. Rios v. Enterprise

Association Steamfitters Local 638 of U.A., 501 F.2d 622,

628-31 (2d Cir. 1974); United States v. N. L. Industries,

Inc., 479 F.2d 354, 377 (8th Cir. 1973); Southern Illinois

Builders Association v. Ogilvie, 471 F .2d 680, 683-86 (7th

Cir. 1972); United States v. Ironworkers Local 86, 443 F.2d

544, 552-53 (9th Cir. 1971); United States v. International

Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, Local No. 38, 428 F .2d

144, 149-51 (6th Cir. 1970); Local 53 of International Ass'n

of Heat & Frost I. & A. Workers v. Vogler, 407 F.2d 1047,

1053-54 (5th Cir. 1969). This construction of the Act is in

harmony with other cases which authorize preferential relief

from unlawful employment discrimination in situations where

Title VII is not applicable. Associated General Contractors

of Massachusetts, Inc. v. Altshuler, 490 F.2d 9, 16-18 (1st

Cir. 1973); Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d 315, 330 (8th Cir.

1971); Contractors Association of Eastern Pennsylvania v.

Secretary of Labor, 442 F.2d 159, 172, 176-77 (3d Cir.

1971). In all, eight circuits have approved some form of

temporary preferential relief for discriminatory employment

practices. See Sape, The Use of Numerical Quotas to Achieve

Integration in Employment, 16 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 481, 499

(1975)• No court of appeals has ruled to the contrary,

although there have been dissents.

*J

a case

We have not previously ruled on the issue, but in

involving the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and the

thirteenth and fourteenth amendments, we declined to impose

quotas where the district court concluded that adequate

relief could be obtained without their use. See Harper v.

Kloster, 486 F.2d 1134, 1136 (4th Cir. 1973). In view of

the substantial precedent sanctioning preferential relief

for unlawful discrimination, we reject the company's argu

ment that Title VII forbids the remedy ordered by the

district court. We recognize, however, that cases which

approve such remedies caution that the necessity for prefer

ential treatment should be carefully scrutinized and that

such relief should be required only when there is a compelling

need for it. See Associated General Contractors of Massachu

setts, Inc. v. Altshuler, 490 F.2d 9, 17 (1st Cir. 1973).

This brings us to the company's second reason for vacating

the decree's provision for preferential appointment of

supervisors.

The company argues that its appointment of black

and female employees to supervisory positions already

exceeds the ratio that preferential relief would require.

Its argument rests on two premises. One, its conduct before

the effective date of Title VII does not provide a proper

base to measure its compliance with the Act; instead, it

must be judged by the manner in which it filled vacancies

-37-

after this date. Two, the district court erroneously

considered the number of blacks and women in the Richmond

SMSA workforce as a whole to ascertain a ratio of acceptable

performance, instead of using only the blacks and women in

the Richmond SMSA supervisory workforce.

We believe these premises are well founded. Title

16

VII is not retroactive. It does not provide a remedy for

discrimination which occurred before it became effective in

1965. Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791, 795 (4th

Cir. 1971). At the Virginia branch 51 of the supervisors

were appointed before Title VII prohibited discrimination in

their selection. They should not be counted in determining

whether preferential hiring is required now. Between 1965

and 1973 the company appointed 18 assistant foremen, the

entry level position for supervisors. Of that number, five

(27.5 percent) were black and three (16.6 percent) were

women. At the Richmond branch, 22 of the supervisors were

appointed before Title VII became effective and nine afterwards.

Of the nine, three (33.3 percent) were black and two (22

percent) were women. At the Richmond office, the evidence

is not as clear. It has six entry level supervisory positions,

which at the date of trial were filled by five white males

with one vacancy. The district court found that four of the

six positions had been filled after 1965. Subsequently, the

16. The legislative history of Title VII indicates

that it is not intended to be retroactive. See note 6

supra.

-38'-

H

i

i

■>*

i

' 4

3

ii

i

i

i

%

tArt*

*iI

1x

J

*

*

e

? . ' • I , • ' y . , . ( ■ . r : , : .. . .v ̂ ‘ V ■ . ^__ J *'■ ' , y V

f .

company proffered evidence that it has promoted one black

employee and one female to supervisory positions, constituting

for each classification 16.6 percent of the appointments

17

since 1965.

The record discloses that 6.8 percent of the

blacks and 1.5 percent of the women in the Richmond SMSA are

placed in a category that includes supervisory personnel.

Those percentages furnish a more realistic measure of the

company's conduct than the gross percentage of blacks and

women in the whole workforce, including unskilled labor.

See Harper v. Mayor, 359 F.Supp. 1187, 1193 n.5 (D. Md.),

aff'd sub nom. Harper v. Kloster, 486 F.2d 1134 (4th Cir.

1973).

The fact that the company's appointments since

1965 exceed the ratio of qualified blacks and women in the

workforce does not exonerate the company for the violations

of the Act which the district court found. The tardy appoint

ments of blacks and women to supervisory positions long

after the passage of Title VII and the present lack of

published job descriptions and objective selection procedures

17. The district court declined to reopen the record to

consider this proffer. Under the ratio <;°urtused for comparative purposes, the evidence had but

slight probative effect. Its import, however, is

magnified by acceptance of the company s premise t Tts performance since 1965 is what must be examined in

determining whether it has violated the Act. 0* remand

the court should reexamine the situation at the Richmond

office.

-39-

r - \ ipppf! p . /■■■-■ g p f p p jppgjjg j I Ip

fully justify the injunctive relief the district court

ordered. We believe, however, that the rate at which the

company currently appoints blacks and women to supervisory

positions is sufficient to show that^there is no compelling

need for the imposition of a quota. But see Karst &

Horowitz,'Affirmative Action and Equal Protection, 60 Va. L.

Rev. 955 (1974).

IV

The company contends that the charge filed with

the EEOC on January 3, 1969, was not timely because there

were no discriminatory practices at either branch after

January 15, 1968. It argues that for this reason the action

should be dismissed for failure to meet the jurisdictional

requirement of a timely charge. The district court,

however, found that the discrimination was of a continuing

18 We do not mean to suggest that the company may use

its percentage of black and female supervisors as a

defense to future charges of discrimination against blacks and women. It must consider each application on

its merits. If the company discriminates against a

black or a woman, it can be called to account for

violating Title VII, regardless of the percentage of

blacks and women among its supervisors.

19 Before the 1972 amendments to Title VII, a charge

had to be filed with the EEOC within 90 days of the

alleged unlawful employment practice. 42 U.S.c.

§ 2000e-5(d) (1964). In 1972, this period was changed

to 180 days. 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(e).

-40-

1

*\

V

i

'•’A

- * • /

’4-1549

nature and properly held that the charge was timely.

Williams v. Norfolk i Western ?.y. , ____ ~. 2c ____, Nc

(4th Cir. 1975', ; llar^lin v. Freight ?ys:«s. Ir.c. ,

478 F. 2d 979 , 994 (D.C. Cir. 1973); s£e Johnson v. Railway

F.xprcss Agency, Inc. , 421 U.S. 454, 467 n.13 (1975) (dictum) .

The district court ruled that the filing of the

charge in 1969 did not toll the statute of limitations for

the § 1981 action which was filed in 1973. The Supreme

Court recently confirmed the district court s correct

understanding of the law. Johnson v. Railway Express Agency,

Inc., 421 U.S. 454 (1975).

The district court applied the Virginia five-year

statute of limitations to the § 1981 action. We have ruled,

however, that the state's two-year statute applies to § 1982

actions. Allen v. Gifford, 462 F.2d 615 (4th Cir. 1972).

Doth § 1981 and § 1982 were enacted to redress infringements

of closely related civil rights. We conclude, therefore,

that the same two-year statute should apply to § 1981 actions.

Accord, Revere v. Tidewater Telephone Co., No. 73-1390 (4th

Cir., October 2, 1973)(unpublished opinion applying the two-

year statute to a § 1981 action); cf. Almond v. Kent, 459

F.2d 200 (4th Cir. 1972). Accordingly, on remand, the two-

year statute of limitations should be applied to the § 1981

claim. Of course, the point has little practical significance

in this case in view of the fact that the § 1981 action was

not tolled by the filing of the charge' with the EEOC.

The district court ruled that back pay for sex

discrimination should accrue from April 8, 1967, two years

before the charge was filed with the EEOC. The two-year

period mentioned bv the district judge conforms with the

20 'statute. However, this charge did not allege discrim

ination against women. Instead, this type of discrimination

21

was initially disclosed by the EEOC's investigation.

Dealing with similar circumstances, we held in EEOC v.

General Electric Co., ____F.2d _____, No. 74-1974, slip op.

at 34-36 (4th Cir. 1975), that in the absence of countervailing

equities a trial court should limit back pay to two years

before the employer received notice of the results of the

investigation. On remand the district court should reconsider

its decree in light of this case.

The judgment is affirmed in part and modified in

part, and the case is remanded for further proceedings con

sistent with this opinion.

fit•?\

j

■ y

t

*

h

?. -

20. 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g)

21. See Part II supra.

-42-

' H <vv/**», - fi'*?**

. r

WIDENER, Circuit Judge, concurring and dissenting,

I concur in large part with the opinion of the

court for the reasons stated in the opinion. I differ, how

ever, in some respects, and as to those I respectfully drs-

sent.

SO far as the opinion is based on BEOCjr^General

,.,v r i - -1 9 7 5 ) I dissent for„ ,, Mn 74-1974 (4tn Cir. »Electric Company, No. v

the^reasons set forth in my dissent in that case, our judg

ment in which is not yet final. I should say. however, that

v, +- oingpr one than General Electric this case may be a somewhat closer one tn ----

because here, at least, sex discrimination was the subject

o£ the EEOC complaint, while in GH^era^lectrio it was not.

This case points up the importance of retiring the EEOC to

comply with its own regulations as well as the statute. The

onion here is excused from liability f o r discrimination on

account.of sox because the statute was not complied with.

Tht< IVll,,,„ i':!|vf in 1 ly emphasized and held is that ". . -a

suit brought by the commission before attempting conciliation

is premature," p. 31, because ". . .the commission*s statu

tory duty to attempt conciliation is among its most essen

tial functions." p.32. Despite the fact that both the com

pany and the union were deprived of the first conciliation

step as set forth in 29 CFR § 1601.19a, as well as the statu

tory benefits of conciliation attempts, the company is held

to liability, while the union is not, although the

liability was caused by the collective bargaining agreement

.

-43-

signed by both the company and the union. Thus, I dissent

not only from the finding against the company, but also

from the disparate treatment awarded the company and the

union on facts which are indistinguishable.

While the subject of collective bargaining agree

ments is at hand, I should say I have grave reservations

about considering evidence in this type case of the respec-

p

. . tive positions taken by the company and the union in nego

tiations leading up to collective bargaining agreements when

«

the agreement results in unlawful discrimination. This is

tantamount to allowing a good faith defense disapproved by

us in Moody v. Albemarle Paper Company, 474 F2 134 (4th Cir.

1973). (Modified on other grounds, 422 US 405 (1975).

The district court had only this to say about dam

ages :

"The formulation of the method of calculation

and distribution of the back pay award and

adjustment to the pension and profit-sharing

plans will be complex— sufficiently so as to

tax the ingenuity and good faith of counsel.

In this regard counsel are directed to confer

with a view to agreeing on a plan of calcu

lation and distribution of the back pay award

‘ for submission to the Court--and, indeed, toI

\

■ -44-

1i

J

\.3

1

.

s

ii

m \ • -..' y . ? - •. * •• • . . * •

explore the possibility of settling the

monetary aspects of the case." App. p.

- 42.

With the opinion of the district court in mind, it is seen

that the method of computing damages was not considered by

that court and is not properly before this court, McGowan

v. Gillenwater, 429 F2 586 (4th Cir. 1970), so the detailed

discussion of that subject is a dictum. If the district

court, in ascertaining damages, adopts standards with

which either side is in disagreement, either is at per

fect liberty to appeal the award. Taking up the matter

now, and especially its treatment in detail, when the mat

ter is so complex" as to "tax the ingenuity and good faith

of counsel, and upon no record, is too great a departure

from what I conceive to be the proper rule of courts ex

pressing opinions only with reference to existing contro

versies. There is no controversy at this time between the

Parties about this matter, and an expression of opinion I

think beyond the legitimate function of an appellate court.

I express no opinion as to the correctness of the dictum.

We hold that the imposition of quotas for super

visory positions is error because the "rate at which the

company currently appoints blacks and women to super

visory positions is sufficient to show that there is no

V t -

'■

-45-

*

t