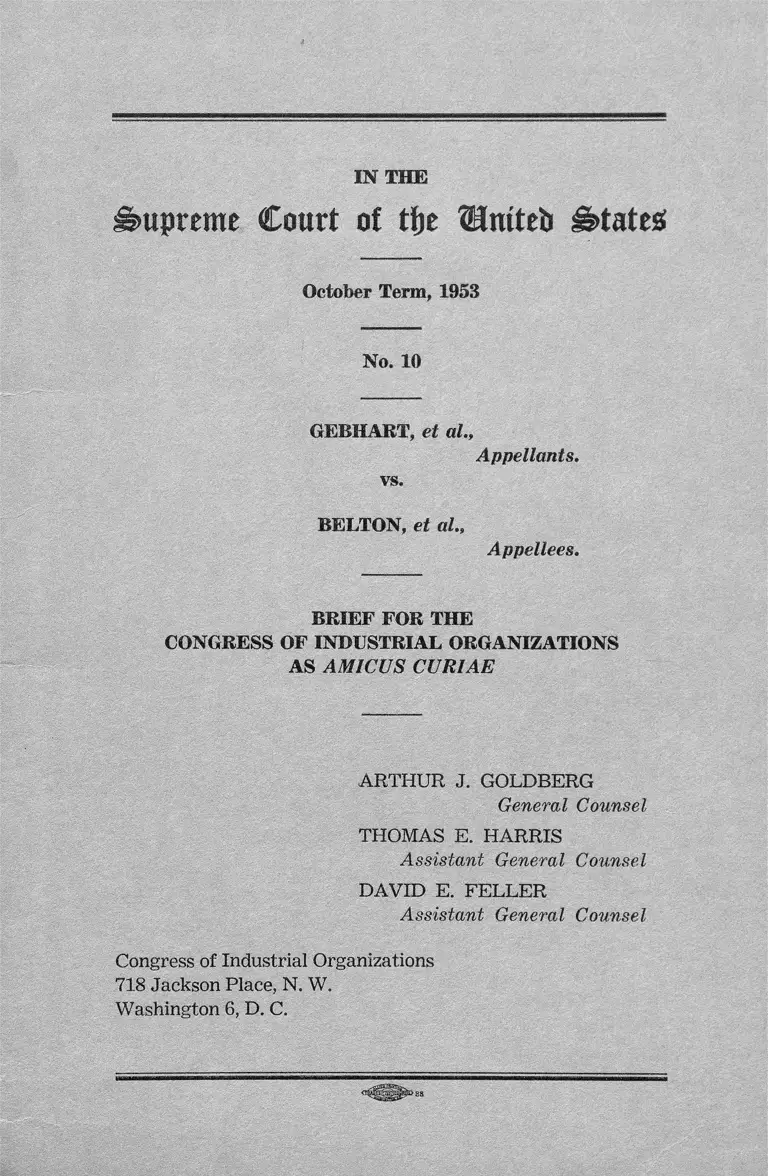

Gebhart v. Belton Brief for the Congress of Industrial Organizations as Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1953

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Gebhart v. Belton Brief for the Congress of Industrial Organizations as Amicus Curiae, 1953. 47910ef2-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0b600e19-983f-471f-a6ff-77b5c377eb54/gebhart-v-belton-brief-for-the-congress-of-industrial-organizations-as-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

Supreme Court of tje Urnteb States?

October Term, 1953

No. 10

GERHART, et al.,

Appellants.

vs.

BELTON, et al.,

Appellees.

BRIEF FOR THE

CONGRESS OF INDUSTRIAL ORGANIZATIONS

AS AMICUS CURIAE

ARTHUR J. GOLDBERG

General Counsel

THOMAS E. HARRIS

Assistant General Counsel

DAVID E. FELLER

Assistant General Counsel

Congress of Industrial Organizations

718 Jackson Place, N. W.

Washington 6, D. C.

•88

IN THE

Supreme Court of tfje Umteb States:

October Term, 1953

No. 10

GERHART, et al.,

Appellants.

vs.

BELTON, et al.,

Appellees.

BRIEF FOR THE

CONGRESS OF INDUSTRIAL ORGANIZATIONS

AS AMICUS CURIAE

THE INTEREST OF THE CIO

This Brief amicus curiae is submitted by the Congress of

Industrial Organizations with the consent of the parties.

The CIO is dedicated to the protection of our democratic

system of government, and, hence of the civil rights of all

Americans. Therefore, it supports the elimination of racial

segregation and discrimination from every phase of American

life.

The CIO’s interest in the specific issues before the Court

in this case is two-fold.

First, racial segregation in the public schools directly af

fects the millions of CIO members whose children attend these

schools. The CIO is convinced that school segregation is

harmful to the Negro children who are thus treated as in

ferior, to the white children in whom attitudes of racial hos

tility and discrimination are thus engendered and encouraged

at an early age, and to the community as a whole. School

2

segregation is a weakening and divisive force in American

life. At the CIO’s International Convention in November of

this year, the delegates unanimously declared their opposi

tion to school segregation, and their support for the position

taken by the plaintiffs in these cases.

Secondly, the outcome of these cases will have indirect ef

fects of great importance to the CIO. The CIO is endeavor

ing to practice non-segregation and non-discrimination in the

everyday conduct of its union business. This effort has re

peatedly been obstructed by statutes, ordinances, and regula

tions which require segregation in public meeting halls, pub

lic dining places, toilet facilities, etc. These laws seek to re

quire CIO unions to maintain “equal but separate” facilities

even in their own buildings, despite our membership’s repudia

tion of segregation in any form. Since the constitutionality

of these laws rests on basically the same line of reasoning

which is put forward to justify school segregation, the de

cision of this Court in these school cases will, in all probability,

have far-reaching implications as to the validity of these other

segregation laws.

More broadly, school segregation, and the general pat

tern of government enforced segregation of which it is a part,

fosters an atmosphere of inter-racial hostility which makes it

more difficult for the CIO to carry out its own non-segregation

policy. Further, this atmosphere of inter-racial hostility is

used by anti-labor employers in opposing CIO organizing

drives: invariably these employers stress the CIO’s opposition

to segregation and discrimination.

THE QUESTION DISCUSSED

In prior briefs amicus curiae, last year in Brown v. Board

of Education of Topeka, and earlier in other school segrega

tion cases, the CIO argued that segregation in public schools

on the basis of race violates the Fourteenth Amendment per

se. That is still our view, and we wholeheartedly subscribe to

the arguments in support of it advanced by counsel for the

appellants in Nos. 1, 2, and 4, and for the respondents in No.

10. Instead of repeating those arguments, however, we have

concluded that it would be most helpful to the Court for us

3

to confine our discussion to one particular issue on which the

CIO has a certain amount of special experience and expert

knowledge.

That issue, set out in paragraph 4 of the Court’s Order of

June 8, 1953, is what the Court should do if it concludes that

segregation in the public schools violates the Fourteenth

Amendment, i. e., whether the Court should order segregation

terminated “forthwith” or permit “gradual adjustment.”

This issue is very similar to the problem which the CIO and

its affiliated unions have repeatedly faced as to how best to

put into effect the non-segregation and non-discrimination

policies of the national organizations in localities where segre

gation and discrimination have theretofore prevailed. It is

our experience in the handling of this problem that we wish

to lay before the Court.

ARGUMENT

NON-SEGREGATION COULD BE EFFECTUATED WITH

LESS DISTURBANCE BY A “FORTHWITH” DECREE

THAN BY “GRADUAL ADJUSTMENT.”

This memorandum seeks to summarize for the Court the

experience and conclusions of unions and employers as to the

best way to effectuate non-discrimination or non-segregation

policies, and specifically as to how “forthwith” enforcement

compares with “gradual adjustment.” The bulk of this ex

perience, both union and employer, relates to the institution

or enforcement of a policy of non-discrimination and non

segregation in employment. The unions have, however, also

had some experience with respect to desegregation in other

fields, such as use of meeting halls and other union facilities.

As will be seen, all of this experience, union and employer,

reinforces this central point: if a union or an employer wants

to put into effect a policy of non-discrimination or non-segre

gation, it should do it “forthwith,” firmly and decisively, and

should avoid “gradual adjustment” or any other formula of

indefinite postponement. If the policy of non-discrimination

or non-segregation is put into effect concurrently with its an

nouncement, and if it is enforced with firmness and decisive

4

ness, there is every likelihood that the policy will be generally

accepted and that any substantial degree of inter-racial fric

tion will be avoided. The bulk of the people in any communi

ty or plant or office are influenced in their attitudes on racial

discrimination by the current practice in the community or

plant or office. If the practice is changed, and if the change be

made unequivocally, they accept the new practice and their at

titudes come to reflect it. Thus traditional Southern attitudes

on racial segregation largely mirror, according to our ex

perience, simply the prevailing practices, rather than deeply

or strongly held individual convictions. Once the practice is

changed, beliefs as to what the practice should be will change

too.

Conversely, “gradual adjustment” to a new policy of non

segregation or non-discrimination is apt to work less well.

Long drawn out discussion of a contemplated ultimate end of

segregation or discrimination may serve only to exacerbate

racial tensions. Division along racial lines may harden and

people may be led to take more extreme and adamant stands

than they would have if the issue had been disposed of prompt

ly, once and for all. For example, in a plant where Negro

workers have customarily been excluded from certain types

of jobs it may prove extremely difficult to persuade the

white workers, through a program of education and discus

sion, that the time has come to end this discrimination. Such

a program may serve only to accentuate inter-racial tension

by keeping the issue alive and in suspension. On the other

hand, if the union and employer firmly announce that hence

forth there will be no job discrimination, the new policy will,

in our experience, be accepted by the workers with little fric

tion, and the issue will be disposed of once and for all.

We do not mean that education and discussion do not serve

a purpose in this field; they do. But they should accompany

the effective implementation of a policy of non-discrimination

and non-segregation. Absent such effective implementation,

endless discussion and the indefinite postponements of “grad

ual adjustment” may serve only to freeze or accentuate at

titudes. If no fixed terminal date for segregation is set, its

proponents will regard the issue as really still open, and the

5

controversy is likely only to become more intense with the

passage of time.

Our experience suggests, we think, one further point:

The CIO and its unions have put non-segregation and non

discrimination policies into effect in all parts of the country.

No major strife has resulted within these organizations—and

they are voluntary organizations, whose officers are elected

by the membership and whose very existence depends upon the

continued good will of the membership. If the non-segregation

policies of these voluntary organizations, when promptly and

firmly implemented, can win such acceptance, then, a fortiori,

a definitive decree of the highest Court of the land will receive

general acceptance.

I

UNION EXPERIENCE

We have stated the conclusions which the CIO has reached

as to the best procedure to follow in putting into effect a policy

of non-discrimination or non-segregation. These conclusions

rest on a very considerable body of experience. The CIO and

its affiliated unions have some hundreds of thousands of mem

bers in Southern communities where racial segregation and

discrimination, except for the changes the CIO has effected,

permeate all aspects of life. It and its affiliates have other

hundreds of thousands of members in border communities,

or others, where some degree of segregation and discrimina

tion is prevalent.

Yet the CIO has from its beginning stood out against these

community prejudices. The CIO Constitution dedicates our

organizations “to bring about the effective organization of the

workingmen and women of America regardless of race, creed,

color or nationality” and “to protect and extend our demo

cratic constitutions and civil rights and liberties, and thus

to perpetuate the cherished traditions of our democracy.”

Similar provisions are found in the constitutions of the inter

national unions affiliated with the CIO. Accordingly the CIO

and its affiliated unions have, from their inceptions, opposed

discrimination in any form based on race or color.

6

The meetings of the CIO and its affiliates are never segre

gated, although, in many areas where we operate ours are the

only unsegregated meetings held in the community. Negro

members belong to the same local unions and have the same

rights as white members. Local union officers are elected

without regard to color. Scores of Negroes now hold local

union offices, or participate in collective bargaining as mem

bers of union negotiating committees. There are local unions

that have Negro presidents.

The CIO conducts educational institutes at various places

in the south for southern workers—white and Negro; male

and female. These educational classes are entirely non-seg-

regated. So also are the political meetings held from time

to time by the CIO’s Political Action Committee.

As discussed in more detail later, there is now no segre

gation in the use of CIO facilities, such as meeting halls, rest

rooms, drinking fountains, etc. Where the CIO and its unions

have their way, there is likewise no segregation in the use

of plant eating places, locker rooms, rest rooms, etc. Some

times, however, state laws or local ordinances require seg

regation in the use of these facilities, and employers usually

comply with laws, unlike the CIO which disregards them as

unconstitutional.

Many of the collective bargaining agreements which the

CIO and its affiliates have negotiated specifically forbid dis

crimination on account of race in hiring, promotion, or any

term or condition of employment; and whether or not the

contracts contain such specific provisions we see to it that

they are administered in a non-discriminatory manner.

We do not assert that this insistence by the CIO and its

unions on no segregation and no discrimination on account of

race has not sometimes been the subject of friction within the

unions. Nor do we say that it has not sometimes made the

CIO’s organizing task more difficult in some communities.

There has been some friction: Our unions have had to expel

a few members and have even suspended the charter of an

occasional local union for refusal to abide by these principles,

likewise, anti-union employers have repeatedly cited our

anti-discrimination policies in opposing organizing campaigns

7

of CIO unions, and their opposition has sometimes been suc

cessful.

We do assert, however, that there has been no major strife

or difficulty or division within CIO unions or locals on this is

sue. We are confident, moreover, that the unequivocal stand

taken by the CIO and its affiliated unions in opposition to seg

regation or discrimination, and their refusal to temporize on

this issue, has resulted in more rapid acceptance of this policy

by locals in the South, and in less friction with regard to it,

than would have been the case had we followed a program of

gradual adjustment to local mores.

We will set forth, with a minimum of comment, some of

the experiences of the CIO and its unions on this subject.

At the outset we wish to call to the Court’s attention

the experience of the United Automobile, Aircraft and Ag

ricultural Implement Workers of America, CIO, on this sub

ject. The following quotation is from an article by Brendan

Sexton, Educational Director of the UAW, entitled “The In

tervention of the Union in the Plant,” appearing in The Jour

nal of Social Issues. Volume 9, No. 1, pages 8-10. Italics

have been added.

“Where the problem of ‘up-grading’ has created conflict,

the union has been divided regarding the attitude it

should take towards the recalcitrant group of workers.

One group has advocated a ‘soft’ educational approach,

another a ‘hard’ course of action. Those who favor edu

cation have argued that the abrupt introduction of Ne

groes into cohesive work groups can only produce aggra

vations, incite suspicions and provoke wildcat strikes

and/or slowdowns. Those who argue for ‘action’ insist

that an informal work group should not be allowed to

constitute itself, on the basis of its own sentiments or

prejudices, the arbiter of a man’s right to a job. The

job is the man’s right and the work group must bend to

that broader democratic rule; the individual seeking that

job should not have to bend to the wishes of the work

group. But more than demonstration of principle is in

volved, the action partisans would argue. Tactically, the

approach is also correct, for the union and the company

are also claimants to a man’s loyalty, and by invoking the

authority of the union and management, the work group

can psychologically accept these wider claims. In some

8

instances, this dispute has been complicated by two

groups of extremists; on the one hand, the Communists

and their supporters have espoused action largely for

disruptive purposes; on the other hand, advocates of ‘do-

nothingism’ argue for education as a blind to postpone

change. Apart from these extraneous motivations, the

issue remains as a real moral and tactical dilemma.

“The writer knows of no objective tests of either ap

proach. In practice, the union has found that the great

est progress has been achieved where the action method

has been used, followed by educational techniques. In

those instances, the educational materials have served

as a convenient and psychologically necessary rational

ization to make acceptable the fact that his behavior has

been changed by external sanction— the authority of

the union.

“There are many drawbacks to the use of ‘group dis

cussion’ as a technique of effecting change in a work

plant. Actually we doubt that minority individuals would

win many jobs or promotion if unions had put the ques

tion to a vote in the work group. Lazy prejudices are

hard to change when the group is allowed to feel that

that being accepted by it is a privilege. The question

arises, too, what is the locus of democratic opinion? Who

should be permitted to vote on such a question? Should

it be the workers in the specific department where the

job is open, the general job classification to which the

workers are assigned, the local union of which they are

members?

“In the UAW, as in many other unions, the basic issue

is decided at international union conventions. And resolu

tions establishing a non-discrimination policy received

all but unanimous support. Since this was accepted as

basic union policy, all sub-units of the union are expected

to carry out this policy. . . .

“. . . Sometimes great resistance develops when such a

policy is imposed. In such instances both the action and

education techniques must be applied judiciously. In

an area in which prejudices are strong, however, pro

longed discussion may only serve to generate and re

inforce resistance to the application of the union policy.”

In the passage of his article just quoted, Mr. Sexton sums

up the conclusions which have been reached by the UAW-CIO,

one of the country’s largest unions, on how a union can best

go about implementing a non-discrimination policy. Else-*

9

where in this article Mr. Sexton summarizes some of the ex

periences which led his union to this conclusion. Typical of

these experiences is the following, described on page 9 of

Mr. Sexton’s article:

“Members of Local 988 of the UAW-CIO, at the plant of

the International Harvester Corporation in Memphis, Ten

nessee, struck against the upgrading of a Negro into a

semi-skilled job in which Negroes had hitherto not been

employed. A good deal of education on the desirability

of eliminating discrimination had been carried on in this

local. In all likelihood this program was as effective as

any union education program in any similar local. More

over this local union had seemed to be more advanced in

its attitudes than many other ‘Southern’ locals in the

UAW. It had elected Negroes as local union officers and

bargaining committeemen and had, on at least two oc

casions, sent Negroes as delegates to international union

conventions. Nevertheless, when a Negro was promoted

to a welding job, the workers at the plant struck to en

force an informal ban against the admission of Negroes

into this classification.

“The union neither debated nor discussed the question

with the workers affected. It sent to the local union

an order adopted by the international executive board,

signed by Walter Reuther, which ‘instructed’ all workers

to return to their jobs. The order called upon the author

ity, of the constitution which had been adopted at the in

ternational union’s convention. As a result of the order,

the strike was called off. The Negro worker was up

graded and there has been no recurrence of trouble at this

plant.”

The experiences of the United Steelworkers of America,

CIO, another of the country’s largest unions, have been simi

lar. The greatest aggregation of heavy industry in the South

is found in and around Birmingham, Alabama. The mines

and mills of the area—coal, iron, and steel—are all unionized,

with tens of thousands of steelworkers and iron miners be

longing to the United Steelworkers of America.

Despite a prevalent community pattern of segregation and

discrimination, the Steelworker’s locals have been unsegre

gated from their inception. White and Negro members be

long to the same local unions, attend meetings together, and

10

elect their local union officers without regard to the color of

their skins. In the administration of collective bargaining

agreements, the local union officers and the staff representa

tives of the International—some of whom, like some of the

local union officers, are Negroes—are scrupulous to see that

there is no discrimination in hiring, advancement, or any

term or condition of employment on account of race.

In past years there was undeniably some friction in the

Birmingham area over these union policies of no discrimina

tion and no segregation. The union, nevertheless, adhered

to these policies firmly and unequivocally, while at the same

time undertaking to persuade its members of their soundness

and justice. As part of the latter effort, the late Philip Mur

ray, then President of the CIO and of the United Steelwork

ers of America, on one occasion addressed a mass meeting

of thousands of persons in the Birmingham ball park.

The international unions’ firm adherence to its policies,

coupled contemporaneously with discussion and explanation,

has won general acceptance for those policies among the mem

bership in the Birmingham area. They are no longer a source

of friction or difficulty. Relations between white and Negro

workers in the local unions and in the plants are now general

ly excellent. Indeed a few months ago the largest steel mill in

the area was shut down when thousands of white workers

joined a small number of Negro workers in protesting cer

tain work conditions of the latter.

The experience of the Steelworkers’ Union with regard to

race segregation has not, incidentally, been confined to the

South. In 1947 the Gary, Indiana, schools started admitting

Negroes to elementary and high school classes theretofore re

served for whites, and hundreds of the white students, many

of them children of steelworkers, declared a “holiday” from

classes. The Steelworker’s Union went into action in sup

port of the school authorities. The District Director, Joseph

Germano, explained to a meeting at the union hall the policies

of the union against discrimination or segregation, and the

meeting voted to suspend from the union members whose

children remained away from school. The children went back

11

to school. (This incident was reported in The New York

Times for September 8, 1947.)

The following quotation relates to one of our smaller

unions, the United Packinghouse Workers, CIO. It is from

John Hope H, “The Self-Survey of the Packinghouse Union,”

in The Journal of Social Issues, Vol. 9, No. 1, p. 35:

“An effort of a dissident white minority to stymie the

desegregation of plant facilities, as required by the mas

ter contract of 1952, in a Southern branch plant of a

major chain packer was defeated when the local officers

who had courageously abided by their contractual obliga

tions were re-elected over a lily-white slate of candidates

who had sought to retire them from office purely on the

race issue. In another Southern plant a brief protest of

white women against, newly hired Negro women using the

some locker room was followed by their acceptance, and

later by the insistence of white women that procrastina

tion in the desegregation of the men’s locker room be

ended. Both are now integrated and no unfavorable

consequences are apparent.”

These illustrations could be multiplied indefinitely.

We shall, however, cite but one further instance from the

CIO’s experience; an instance which relates not to segregation

or discrimination on the job, but to segregation in union

meeting halls, eating places, toilets, etc.

We have already mentioned that various state and local

ordinances purport to require separate and segregated facili

ties. The existence of these laws, and uncertainty as whether

they should be complied with, occasioned a certain amount

of friction and confusion in CIO State and local councils for

some years.

However, in April 1950, the General Counsel of the CIO

advised its state and local councils that all such laws and

ordinances were, in his opinion, unconstitutional, and that,

in line with general CIO policy, “Therefore, no segregation

in the use of facilities in buildings or office space under the

control of CIO Industrial Union Councils should be permitted,

and there should be no signs indicating such segregation.”

This policy, once clearly laid down, received complete ac

ceptance. There is now no segregation in the use of any CIO

12

council facility—and there has been not the slightest friction

or difficulty about it.

AFL and independent unions seem to have reached the

same conclusions that we have: That a union policy against

discrimination or segregation can be implemented without

substantial strife or difficulty, if such a policy is unequivocally

enunciated and unhesitatingly enforced.

For example, the Indianapolis News, for June 24 and 25,

1953, carries a story about a wildcat strike among a minority

of Indianapolis railway operators against the proposed hiring

of Negro drivers. It reports that the secretary-treasurer

of the local union, a local of the Amalgamated Association of

Street, Electric Railway & Motor Coach Employees of Amer

ica, AFL, declared that “Our International Union prohibits

any kind of discrimination,” and ordered the strikers to

return to work, on pain of suspension from the union. The

newspaper account further relates that the strikers returned

to work, and gave assurances that there would be no repeti

tion of the walk-out.

The United Mine Workers (Independent) has followed the

same policy, and with the same results. Here is a quotation

from Herbert R. Northrup, “Organized Labor and the Negro,”

New York, 1946, p. 166, emphasis added:

“It must be re-emphasized at this point that the UMW

has an enviable record of practicing, as well as preaching,

racial equality in its organization ever since it began to

function. It is true that there have been instances of

discrimination against Negroes in particular locals, both

in the North and in the South. But the officials of the

national union have never, to the writer’s knowledge,

condoned such action, and have not hesitated to chas

tise individual locals for failing to live up to the letter

of the non-discrimination policy. Moreover, the UMW

has always conducted both its organizing campaigns and

its day-to-day union affairs without prejudice to any

race.”

We close this enumeration of union experiences and view

points on how best to effectuate an anti-discrimination, anti

segregation, policy with a quotation from Hugo Ernst, Presi

dent, Hotel and Restaurant Employees & Bartenders Inter

13

national Union, AFL, which appears in that Union’s publica

tion, The Catering Industry Employee, for July 1952:

“I wish to speak out in the strongest possible terms con

cerning the question of our local unions and the admis

sion of non-Caucasian members.

“This article is prompted by a newspaper clipping which

was sent me the other day by a West Coast friend. It

was from the front page of a daily paper, and it set forth

the sorry details of a lawsuit filed against one of our

local unions by an employer and three bartenders who

work for him.

“The suit was filed because, although the employer was

willing and ready to sign a union contract, and his work

ers were willing and ready to join the union, the union

would not sign the contract and would not accept these

bartenders as members. The bartenders are all three

Negroes.

“By far the most damaging part of this story lies, not

in the unfavorable publicity of that front-page story, but

in the fact that there are still, in 1952, members of our

International Union who will thus attack the principles

of fair play on which every strong union must be built.

“Our International Constitution is explicit on this matter

of discrimination. Section 11, Article XI states:

“ ‘No Local may reject a person prior to applying for

membership; nor may any Local reject any applicant by

reason of race, religion or color.’

“Nothing could be plainer than that.

“Nobody can be denied membership in our union because

he is a Negro, or because he is an Oriental, or an Indian

or because he is a Catholic or a Jew or a Protestant or

a Moslem or a Buddhist.

“If he is employed at the trade he is eligible for member

ship in the Local Union established to represent persons

in his craft—and that’s that!

“Indeed, it is necessary for me to declare in the plainest

possible terms that I will have no choice, whenever such

situations are brought to my attention, but to place the

guilty local union under trusteeship wherever it persists

in flaunting our constitution on this point.”

II

EMPLOYER EXPERIENCE

The views of employers who have sought to carry out a

policy of non-discrimination, on how best to implement such

14

a policy, largely agree, we believe, with the unions’ conclu

sions on this subject. We wish particularly to call attention

to the testimony on this subject of Ivan L. Willis, Vice Presi

dent in Charge of Industrial Relations, International Har

vester Company, given at Hearings on “Discrimination and

Full Utilization of Manpower Resources”, before the Subcom

mittee on Labor and Labor-Management Relations of the

Senate Committee on Labor and Public Welfare, 82nd Con

gress, 2nd Session, pp. 84-85. The quotation is long, but,

we believe, well worth the Court’s consideration:

“In carrying out our nondiscrimination policy, our ap

proach is about this.

“First, we do something about the problem, rather than

just talk about it.

“Second, we take our actions at as rapid a pace as cir

cumstances permit, and, once taken, we do not retreat.

“Third, we try to keep everyone involved as well in

formed as possible, all the time.

“To illustrate this approach, let me take the example

of a new factory located in a Southern city. In this

particular city there are state laws in effect which re

quire separate drinking fountains, separate toilet facili

ties, separate eating facilities, and so forth. Obviously,

we have to comply with state laws, and we do.

“But, beyond that, many questions arise. The first ques

tion is, of course, ‘Are we going to hire Negroes at all?’

Our answer is ‘Yes’.

“The second question then may be: ‘If we do hire Negroes,

are we going to segregate them, in the sense that we will

simply have all-Negro departments?’

“Our answer is ‘No’. We do not favor all-Negro or all-

white departments.

“The third question is: ‘Shall we start out that way, or

shall we start in conformity with local customs and try

to make a change later?’

“Our answer was: ‘We are going to start on an unsegre

gated basis’.

“The next question is: ‘How can we do that?’

“Our answer—for now we are coming to the root of the

problem—was more complicated. We said: ‘First, we will

have to make sure that all our managerial people, our

foremen, and supervisors thoroughly understand our

policy and the reasons behind it, so that they will be able

and willing to do a good job in its application.’

15

“Second, we said, ‘Everybody must know our policy’. So,

as men came to the hiring office to apply for work in the

new plant, they were all told what our policy was.

“I might insert there, Senator, when we first started em

ploying people at that plant, we permitted all applicants

regardless of their race or color to come into a common

waiting room. That was our first departure perhaps from

the customary practice in that area where it was nor

mally the practice to have white employees come into

one room for interviews and the Negroes be either hired

at the gate or to come into a separate room.

“They were told that they might find themselves working

next to a Negro employee and were given the oppor

tunity at that time to decide whether that would be dis

tasteful to them. Surprisingly few withdrew at that

point. Next, in the orientation classes for new employees,

all employees were taken together, with no segregation.

Finally, their job assignments were made on the same

basis. As time has passed and they have gained expe

rience, their promotion and upgrading to better jobs

have been carried out on the basis of seniority and

ability.

“We have had very few evidences of resentment or bad

feeling as a result of our policy. A few times, in this

southern plant, there have been incidents, principally

arising in cases where a Negro employee was being up

graded. These have not been too serious in nature and

have been met successfully, through the joint efforts of

the company and the labor union involved, which was

the UAW-CIO.

“As a consequence of our experience, we feel perfectly

sure that progress can be made, with proper planning

and execution of policy. We know that more progress

will be made in the future. We have every reason to be

quite satisfied with the development of our Negro em

ployees, in productivity and in other ways.

“In the introduction of Negro employees into some of

our offices, as distinguished from the manufacturing

shops, we have followed essentially the same procedures.

First, we have thoroughly discussed all phases of the

change with supervisory people. Next, we have had

similar discussions with the employees already on the

rolls. In practice, we have not met any difficulty which

I would consider to be a real problem. In general, things

have gone smoothly, and the Negro men and women

have fitted in quite well with the rest of the group.

16

“As a result of our total experience, I think all of us are

convinced that there is nothing insuperable about the

problem of integrating minority groups into industry, in

any area of the United States. We recognize that prog

ress may be faster in some places than in others, but we

do see progress all along the line.”

If the views set forth in this testimony are compared with

those of Brendan Sexton, UAW Educational Director, quoted

supra, p. 7, it will be seen that here is one subject on

which the views of the company and the union coincide to

a remarkable degree. They are in full agreement that the

best way to effectuate a policy against racial discrimination

or segregation is to announce it firmly and carry it out un

equivocally, instead of attempting to depart gradually from

local customs.

These views likewise find support in the conclusions of the

New York State War Council Committee on Discrimination

in Employment. In a pamphlet issued in 1942, entitled “How

Management Can Integrate Negroes in War Industries”, the

Council stated:

“Introduction of the Negro Worker. Necessity for Firm

ness and a Real Desire to Integrate Negroes.

“All persons who have dealt with the problem, including

the personnel managers and government officials inter

viewed, agree that nothing is so important as a firm posi

tion on the part of management. Once this position has

been stated in terms of Executive Order 8802 and the

laws of the State of New York and a recalcitrant white

worker still refuses to work with colored persons, man

agement can only transfer the worker or ask for his

resignation. This will seldom or never be necessary if

the situation is clearly explained. Of all the companies

interviewed only one found it necessary to allow a person

to resign.”

Finally, we respectfully call attention to certain conclu

sions which resulted from a study conducted by the New York

State School of Industrial and Labor Relations, at Cornell

University. Its Research Bulletin No. 6, February 1950, on

“Negroes in the Work Group”, states:

“Certain conclusions may be reasonably inferred from

the data obtained from this study. Again it must be

17

noted that this is a selected study of a few firms, all of

which had a good record for employing Negroes.

“ (1) A Firm and Unequivocal Stand

“Employers who decide to hire Negroes for the first time

or to hire additional Negroes in new capacities should

adopt a firm attitude in this matter. The employer must

be resolute in his intentions to enforce this policy re

gardless of any real or illusory objections that may be

raised by people in the organization.

“By adhering to a determined attitude to make the pro

gram work, any obstacles that may be raised will be

smoothed over or adjusted. Employers earnest in their

determination to integrate the Negro will soon find their

subordinates as well as their employees following their

views.”

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated, we respectfully suggest to the Court,

that if it concludes, as we think it should, that segregation

in public schools violates the Fourteenth Amendment, it would

be preferable for it to implement this conclusion by directing

the cessation of segregation “forthwith” rather than by “grad

ual adjustment”.

Respectfully submitted,

ARTHUR J. GOLDBERG

General Counsel

THOMAS E. HARRIS

Assistant General Counsel

DAVID E. FELLER

Assistant General Counsel

Congress of Industrial Organizations

718 Jackson Place, N. W.

Washington 6, D. C.