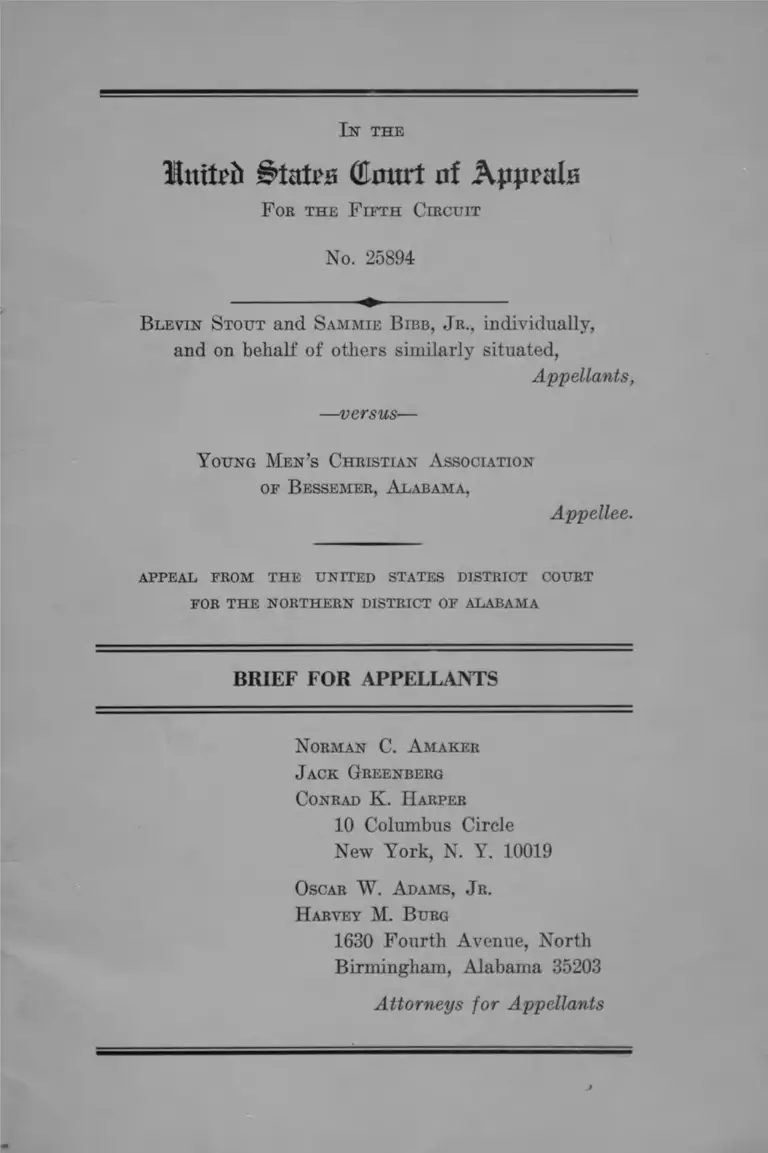

Stout v. Young Men's Christian Association of Bessemer Alabama Brief of Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1968

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Stout v. Young Men's Christian Association of Bessemer Alabama Brief of Appellants, 1968. 1aa2af41-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0cfbe528-286b-4f54-8b4e-e413405b65a4/stout-v-young-mens-christian-association-of-bessemer-alabama-brief-of-appellants. Accessed January 29, 2026.

Copied!

I n the

Imtri* (Emtrt at Ajiyrals

F ok the F ifth Circuit

No. 25894

B l e v in Stout and Sammie B ibb, J r., individually,

and on behalf o f others similarly situated,

Appellants,

—versus—

Y oung Men ’s Christian A ssociation

of B essemer, Alabama,

Appellee.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Norman C. A maker

J ack Greenberg

Conrad K. H arper

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

Oscar W . A dams, Jr.

Harvey M. B urg

1630 Fourth Avenue, North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

Statement .............................................................................. 1

Specification of Error ........................................................ 5

A rgument :

The Bessemer YMCA is a place of public accom

modation under Title II of the 1964 Civil Rights

Act because (a) it provides lodging to transients

and (b) it serves food to the public for consumption

on the premises ....................................... 5

A. Lodging .................................................................. 5

B. Food ........................................................................ 10

C. The authority of Nesmith v. YMCA of Raleigh,

North Carolina ....................................................... 13

Conclusion............................................................................... 15

Table of A uthorities

Cases:

Adams v. Fazzio Real Estate Co., 268 F. Supp. 630

(E. D. La. 1967) aff’d, No. 24825 (5th Cir., May

28, 1968) ............................................................................ 13

Adler v. Northern Hotel Co., 80 F. Supp. 776 (N. D.

111. 1948), rev’d, 180 F. 2d 742 (7th Cir. 1950) ........... 6

Asseltyne v. Fay Hotel, 22 Minn. 91, 23 N. W. 2d 357

(1946)

PAGE

6

ii

Beale v. Posey, 72 Ala. 323 (1882) ................................... 6

Bolton v. State, 220 Ga. 632, 140 S. E. 2d 866 (1965) .... 11

Codogan v. Fox, 266 F. Supp. 866 (M. D. Fla. 1967) .... 12

Evans v. Laurel Links, Inc., 261 F. Supp. 474 (E. D.

Va. 1966) ......................................................................... 11,12

Foster v. State, 84 Ala. 451, 4 So. 833 (1888) ............... 6, 7

Gregory v. Meyer, 376 F. 2d 509 (5th Cir. 1967) ........... 12

Hamm v. Rock Hill, 379 U. S. 306 (1964) ..... ............. 11,12

Heart of Atlanta Motel v. United States, 379 U. S.

241 (1964) ......................................................................... 5

Holstein v. Phillips & Sims, 146 N. C. 366, 59 S. E. 1037

(1907) ............................................................................. 6

Katzenbach v. McClung, 379 U. S. 294 (1964) ............. 12

Kyles v. Paul, 263 F. Supp. 412 (E. D. Ark. 1967),

aff’d No. 18,824 (8th Cir., May 3, 1968) ..... ......... ..... 13

Meaeham v. Galloway, 102 Tenn. 415, 52 S. W. 859

(1899) ..... 6

Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, Inc., No. 24,259 (5tli

Cir. en banc, April 8, 1968) reversing 391 F. 2d 86

(5th Cir. 1967) .......................................................... .....12,13

Nesmith v. YMCA of Raleigh, North Carolina, 273 F.

Supp. 502 (E. D. N. C. 1967), rev’d, No. 11.931 (4th

Cir. June 7, 1968) ............. 10,11,13,14,15

PAGE

Ill

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprise, Inc., 256 F. Supp.

941 (D. S. C. 1966), rev’d, 377 F. 2d 433 (4th Cir.

1967) .................................................................................. 12

Pettit v. Thomas, 103 Ark. 593, 148 S. W. 501 (1912) .. 6

Pinkney v. Meloy, 241 F. Supp. 943 (N. D. Fla., 1965) .. 13

Statutes :

Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 78 Stat.

PAGE

243, 42 U. S. C. §2000a et seq................... 2, 5,10,12,13,14

42 U. S. C. §1981 .............................................................. 2

Other Authorities:

43 C. J. S. Innkeepers §3 (1945) ................................... 8

Hearings on Miscellaneous Proposals Regarding the

Civil Rights of Persons Within the Jurisdiction of

the United States Before a Subcommittee of the

House Committee on the Judiciary, 88th Cong., 1st

Sess., ser. 4, p. 2 (1963) ............................................... 7,9

Hearings on S. 1732 Before the Senate Committee

on Commerce, 88th Cong., 1st Sess., ser. 26

(1963) ...................................................................... 8,9,10,12

H. R. 7152, S. 1731, S. 1732, 88th Cong., 1st Sess.

(1963) ................................................................................ 11

H. Zworensteyn, Fundamentals of Hotel Law (1963) .... 7

I n the

l&nxttb States (Emtrt of Appeals

F or the F ifth Circuit

No. 25894

B levin Stout and Sammie B ibb, J r., individually,

and on behalf o f others similarly situated,

Appellants,

—versus—

Y oung Men ’s Christian A ssociation

of B essemer, A labama,

Appellee.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement

On November 21, 1966, appellants, Blevin Stout and

Sannnie Bibb, Jr., Negro citizens of Jefferson County,

Alabama, instituted a class action in the United States

District Court for the Northern District of Alabama against

the Young Men’s Christian Association of Bessemer, Ala

bama, Inc. (R. 1, 56). The appellants claimed that the

Y. M. C. A. was depriving them, and Negro citizens simi

2

larly situated, of rights, privileges and immunities secured

by (a) the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution; (b)

the Commerce Clause of the Constitution; (c) Title II of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, providing for injunctive relief

against discrimination in places of public accommoda

tions; and (d) 42 U. S. C. Section 1981, providing for the

equal rights of citizens and all persons within the juris

diction of the United States (R. 1, 2). The complaint al

leged that the Y. M. C. A. pursued a policy of racial dis

crimination in the operation of its facilities, services and

accommodations (R. 4). Plaintiffs prayed for injunctive

relief (R. 5).

On January 5, 1967, the Y. M. C. A. answered the com

plaint (R. 7). After a trial without a jury, the district

court, on December 13, 1967, held that the activities of

the Y. M. C. A. do not affect commerce within the contem

plation of the Civil Rights statutes, and that the Y. M. C. A.

is not a place of public accommodation (R. 15), and dis

missed the complaint with prejudice (R, 15, 16). On De

cember 20, 1967, the findings of fact, conclusions of law and

judgment were amended by striking therefrom the words

“ with prejudice” (R. 18). The appellants filed notice of

appeal to this Court on January 10, 1968 (R. 19).

The Y. M. C. A. is a tax exempt, non-profit corporation

(R. 114). Over 50% of its funds are derived from the

Jefferson County Community Chest, a county-wide solicita

tion of the general public (R. 44, 45). Membership in the

Y. M. C. A. is open to the general public (R. 78, 124, 128).

Of approximately 3,000 membership applications in 1966,

all were accepted except four dormitory applications which

were rejected (R. 102).

3

The Y. M. C. A.’s building located at 1815 Fourth Avenue,

North, Bessemer, Alabama (R. 78, 90), live blocks from

TJ. S. Highway 11 (R. 88), contains forty-six rooms for

rent (R. 47). When rooms are available, lodging is pro

vided to individuals for one night (R. 46, 105). Since the

dormitory membership fee is set on a weekly basis, persons

staying for only one night are not charged a dormitory

membership fee and have no membership privileges (R.

104). Although persons staying for only one night are

supposed to fill out an application (R. 53), Stephen Cotton,

a white Harvard College student temporarily living in

Birmingham, Alabama, testified that he rented a room for

one night on December 7, 1965, without being required to

fill out any membership application or other forms (R.

35). He was given a receipt which stated that the charge

of $1.50 included a membership fee of $.50 (R. 64). Per

sons renting a room for one night are not asked where they

are from or if they are members of any Y. M. C. A. before

being rented lodging (R. 53, 59). They are rented a room

without the prior approval of the Y. M. C. A.’s Board of

Directors (R. 59). During the year 1965, the Y. M. C. A.’s

records show that six individuals stayed at the Y. M. C. A.

less than one week, and in 1966 there were five such in

dividuals (R. 51).

In the basement of the Y. M. C. A .’s building is a dining

room exclusively engaged in selling food for consumption

on the premises (R. 71, 85). This dining room can accom

modate 75 to 80 people comfortably (R. 116). Food is

cooked on the premises (R. 117). The dining room is run

by a caterer employed by the Y. M. C. A. (R. 116). Dinner

is served to church and civic groups two or three nights

each week (R. 117, 124). These groups are not members

4

of the Y. M. C. A. (R. 123). Any group wishing to meet

there regularly must obtain the prior approval of the

Y. M. C. A.’s Board of Directors (R. 116, 124). If the

facilities are available, however, the caterer may serve any

group she chooses on a single occasion (R. 116, 124). Use

of these facilities by any Negro group would under any

circumstances require the prior approval of the Board of

Directors (R. 118, 123, 124). No Negro group has ever

used these dining facilities (R. 111).

Groups using the dining facilities pay the caterer (R. 71,

85). The Y. M. C. A. receives ten cents for each plate

served (R. 117). As the Y. M. C. A. furnishes the equip

ment, lights, gas and maintenance for the dining room,

the dining room operation is not self-supporting (R. 117).

The deficit from this operation is not kept separately in

the Y. M. C. A.’s accounts (R. 117). Once each year for

the past several years, the Lions Club served a supper

in this dining room to which the general public was invited

(R. 49). This tradition has now been discontinued (R. 49).

The Y. M. C. A. does not advertise on radio or television

or in newspapers (R. 84) or by signs on highways (R. 51).

However, the Y. M. C. A. does benefit from the national

publicity of the National Council of Y. M. C. A.’s (R. 98),

of which the Bessemer Y. M. C. A. is a member (R. 84, 97).

In addition, the Bessemer Y. M. C. A. is listed in the Official

Roster of Y. M. C. A .’s published by the National Council

and sold to the general public (R. 53).

On November 17, 1965, appellants Blevin Stout and

Sammie Bibb, Jr., went to the Y. M. C. A. at Bessemer

and asked to rent a room (R. 24, 29). They also inquired

about membership applications (R. 24, 29) and about dining

facilities for organizations (R. 24, 29). The district court

5

found as a fact that Blevin Stout and Sammie Bibb, Jr.

were denied membership and the use of the Y. M. C. A.’s

facilities, because they are Negroes (R. 14), but the court

held the Y. M. C. A. was not subject to Title II because it

allegedly did not accommodate transients or open its facili

ties to the public (R. 15).

Specification of Error

The court below erred in failing to find that the Young

Men’s Christian Association of Bessemer, Alabama, Inc.,

is a place of public accommodation as defined in Title II

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 243, 42 U. S. C.

Sections 2000a et seq., and in failing to issue an injunc

tion requiring desegregation.

A R G U M E N T

The Bessemer YMCA is a place of public accommoda

tion under Title II of the 1964 Civil Rights Act because

(a) it provides lodging to transients and (b ) it serves

food to the public for consumption on the premises.

A. Lodging

The section of Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

which states that any establishment which provides lodg

ing to transient guests is a place of public accommodation,

was viewed by the court in Heart of Atlanta Motel v.

United States, 379 U. S. 241, 249 (1964) as applying to a

motel which admitted coverage under §201 (a) and which

had refused lodging to transient Negroes. Based on the

legislative history regarding this section, the meaning of

the term “ transient guest” at common law, and the express

6

words of the statute itself, it is clear that the Y. M. C. A. of

Bessemer is an establishment which provides lodging to

transient guests.

At common law, a distinction is made between a transient

guest or simply a guest on the one hand, and a lodger on

the other. An individual whose stay is temporary is a

guest, while an individual who intends to remain indefi

nitely or permanently, without any present purpose of

going to any other place, is a lodger. Adler v. Northern

Hotel Co., 80 F. Supp. 776 (N. D. 111. 1948), rev’d on other

grounds, 180 F. 2d 742 (7th Cir. 1950); 43 C. J. S. Inn

keepers §3, 1140, 1143 (1945). The length of an individu

al’s stay, the existence of a special contract for a room,

and the existence of a home elsewhere are material cir

cumstances in determining whether an individual is a guest

or a lodger, but these circumstances are not controlling.

43 C. J. S. Innkeepers §3, 1138 (1945). An individual may

be a transient guest, although he has stayed at an establish

ment for one week or longer, Asseltyne v. Fay Hotel, 22

Minn. 91, 23 N. W. 2d 357 (1946); Pettit v. Thomas, 103

Ark. 593, 148 S. W. 501 (1912); Meacham v. Galloway, 102

Tenn. 415, 52 S. W. 859 (1899); 43 C. J. S. Innkeepers §3,

1138 (1945); even though he is paying a weekly, monthly,

or other reduced rate, Pettit v. Thomas, supra; Holstein v.

Phillips & Sims, 146 N. C. 366, 59 S. E. 1037 (1907); Beale

v. Posey, 72 Ala. 323 (1882); 43 C. J. S. Innkeepers §3,

1138 (1945); and even though he is not a traveler but re

sides in the immediate vicinity, Beale v. Posey, supra; 43

C. J. S. Innkeepers §3, 1140 (1945). A single establish

ment may be both a boarding house in respect to permanent

residents and an inn in respect to transient guests. Adler

v. Northern Hotel Co., supra; Foster v. State, 84 Ala. 451,

4 So. 833 (1888); see also H. Zworensteyn, Fundamentals

of Hotel Law, 16, 34-35 (1963).

The term “ transient guest” was used by the authors of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964 with the intent that it have a

meaning at least as broad as its meaning at common law.

Attorney General Kennedy defined the “ transient guest”

test in a document prepared at the request of the House

Judiciary Committee:

The “ transient guest” requirement exempts estab

lishments, like apartment houses, which provide per

manent residential housing. For example, apartments

rented on month-to-month tenancies automatically re

newed each month unless specifically terminated, are

exempted. The question of coverage would be deter

mined by the actualities of the arrangement. The ques

tion whether an establishment caters to “ transient

guests” would be a question of Federal, not State local

law. Hearings on Miscellaneous Proposals Regarding

the Civil Rights of Persons Within the Jurisdiction of

the United States Before a Subcommittee of the House

Committee on the Judiciary, 88th Cong., 1st Sess.,

ser. 4, p. 2 at 1402 (1963) (hereinafter cited as House

Civil Rights Hearings).

Before the Senate Commerce Committee, Assistant At

torney General Marshall was asked by Senator Morton how

long a person had to stay at a hotel or rooming house to

cease being a transient guest:

Mr. Marshall. I think, Senator, I wouldn’t be able

to cover all possible situations with a definition of it,

but I think places generally either furnish rooms or

apartments to permanent residents or they hold them

7

8

selves out to people that come for maybe a week at a

time or maybe in the case of a summer establishment,

for the summer.

But I think that in almost every case you could tell

the difference between a place that rents from month

to month with the intention of the people that rent

from it of staying there and a place that caters to

people that move in and out. Hearings on 8 . 1732 Be

fore the Senate Committee on Commerce, 88th Cong.,

1st Sess., ser. 26 at 213 (1963) (hereinafter cited as

Senate Civil Rights Hearings).

The Y. M. C. A. at Bessemer is neither an establishment

merely providing permanent residential housing nor a

social club. It is apparent from the legislative history

that the language—“ any establishment which provides

lodging to transient guests”—was intended to embrace this

Y. M. C. A. Aside from one or two retired individuals who

make their home permanently at the Y. M. C. A. (R. 51), the

Y. M. C. A.’s residents are primarily men who work in Bes

semer and have a home in some other place (R. 58). They

go home each weekend (R. 58). They do not intend to stay

at the Y. M. C. A. indefinitely or permanently, without any

present intention of going elsewhere, but to remain only

as long as their employment in Bessemer lasts (R. 58).

At common law and under the meaning intended by Con

gress, these individuals are transient guests and not per

manent residents. That the Y. M. C. A. categorizes these

men as permanent residents and defines a transient as an in

dividual who stays less than one week (R, 57, 58) is imma

terial. The transient guest requirement was intended to

exempt establishments providing permanent residential

9

housing and was never intended to exempt establishments

simply because guests usually remain longer than one week.

The district court erred in construing “transient guest” to

mean travelers who remain at an establishment less than

one week.

Assuming arguendo that the district court’s definition of

transient guest is correct, the undisputed facts show that

the Y. M. C. A. provides lodging to transient guests (R. 13).

But because rooms are rented to such transients only occa

sionally and because “ as far as the evidence reveals, all

of these so-called transients were residents of the State of

Alabama” (R. 13), the lower court erroneously concluded

that the Y. M. C. A. is not a place of public accommodation

(R. 15). An establishment providing lodging to transient

guests was intended to be covered whether the guests are

from within the state or from without, and whether or not

transient guests in large numbers are accommodated.

Senate Civil Rights Hearings at 66, 170 (testimony of

Attorney General Kennedy).

A requirement that a “ substantial” part of an establish

ment’s business be in interstate commerce was intentionally

omitted. House Civil Rights Hearings at 1386 (testimony

of Attorney General Kennedy). In testimony before the

House Judiciary Committee and the Senate Commerce

Committee, Attorney General Kennedy affirmed that the

provision on lodgings was intended to cover small as well

as large establishments and that the size of a business was

not a criterion for coverage. Id. at 1384; Senate Civil

Rights Hearings at 24. It was decided not to set some arbi

trary standard because discrimination by many small

establishments imposes a cumulative burden on interstate

commerce, Senate Civil Rights Hearings at 24 (testimony

10

of Attorney General Kennedy), and because it makes little

sense to prohibit a large and not a small establishment

from discriminating, Id. at 59.

There is no basis in the legislative history for the tests

imposed by the district court in determining whether the

Y. M. C. A. provides lodging to transient guests within the

meaning of Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The

statutory language was intended to be absolute, in order

that virtually all persons operating establishments provid

ing public accommodations would know they were covered.

Senate Civil Rights Hearings at 24 (testimony of Attorney

General Kennedy) and at 210 (testimony of Assistant At

torney General Marshall). On the basis of the undisputed

fact that the Y. M. C. A. occasionally rents rooms to tran

sient guests, that the Y. M. C. A. is listed in a directory cir

culated throughout the United States, and that Y. M. C. A .’s

customarily provide lodging to transient guests (R. 112),

the Y. M. C. A. is a place of public accommodation.

B. Food

It is not disputed that there is an eating place exclusively

engaged in selling food for consumption on the premises

located within the Y. M. C. A .’s building (R. 12). The dis

trict court found that the Y. M. C. A. did not operate this

eating place (R. 12). There is no support for this finding

in the record. The Y. M. C. A. employs a caterer to pur

chase and prepare the food sold (R. 116). The Y. M. C. A.

absorbs the deficit from this operation in its general budget

(R. 117). This factor was regarded by the Fourth Circuit

as significant in finding that the Raleigh Y. M. C. A. was

a single establishment. Nesmith v. Y. M. C. A. of Raleigh,

N. C., 273 F. Supp. 502 (E. D. N. C. 1967), rev’d, No. 11,931

11

(4th Cir. June 7, 1968) (slip op. 5). The caterer is not free

to serve any group she chooses, but must obtain the Board

of Directors’ prior approval before serving any group on

a regular basis (R. 116, 124) or before serving a Negro

group under any circumstances (R. 118, 123).

The original civil rights bill required that an eating place

serve interstate travelers to a substantial degree; this re

quirement was later omitted by substituting the current

provision that an offer to serve interstate travelers would

affect commerce, H. R. 7152, S. 1731, S. 1732, 88th Cong.,

1st Sess. (1963). That this offer is made only to groups

and not to individuals is immaterial. An offer to serve the

general public, whether in groups or as individuals, under

circumstances which make it reasonable to assume that

some interstate travelers will accept the offer has been

treated as an offer to serve interstate travelers, where, as

here, there is no inquiry made as to the customers’ origin.

Hamm. v. Rock Hill, 379 U. S. 306 (1964); Evans v. Laurel

Links, Inc., 261 F. Supp. 474 (E. D. Ya. 1966); Bolton v.

State, 220 Ga. 632, 140 S. E. 2d 866 (1965). In Evans v.

Laurel Links, Inc. the court held that where a lunch counter

on a golf course offered to serve the general public and

players occasionally came from Washington, D. C., to par

ticipate in tournaments, it was reasonable to assume that

some interstate travelers would accept the lunch counter’s

offer. In serving groups such as the Rotary Club, The

Kiwanis Club, and The Industrial Management Club (R.

116), which customarily provide guest speakers at lunch

eons and which customarily hold their luncheons or dinners

out to members from all over the United States, the

Y. M. C. A. is offering to serve interstate travelers. That

interstate travelers are in fact actually served without

12

inquiry as to their origin is evidenced by the fact that

Stephen Cotton, a Harvard College student temporarily

residing in Birmingham, was served without question at a

Lions Club dinner (R. 39-40). The fact that the Y. M. C. A.

does not formally advertise its eating place does not pre

clude finding an offer to serve interstate travelers. Codogan

v. Fox, 266 F. Supp. 866 (M. D. Fla. 1967). The Y. M. C. A .’s

location five blocks from an interstate highway (R. 88) is

also material to coverage under Title II. Gregory v. Meyer,

376 F. 2d 509 (5th Cir. 1967) (3 blocks from federal high

way) ; Evans v. Laurel Links, Inc., supra (4 blocks from

State highway and 5 miles from nearest II. S. highway);

see also Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, Inc., No. 24,259

(5th Cir. en banc, April 8, 1968).

In addition, a substantial portion of the food served at

the Y. M. C. A. has moved in commerce. It is settled that

substantial means “more than minimal” . Gregory v. Meyer,

376 F. 2d 509, 511 n. 1 (5th Cir. 1967); Newman v. Piggie

Park Enterprise, Inc., 256 F. Supp. 941 (D. S. C. 1966),

rev’d on other grounds, 377 F. 2d 433 (4th Cir. 1967) (18%

is substantial); Codogan v. Fox, 266 F. Supp. 866 (M. D.

Fla. 1967); Senate Civil Bights Hearings at 24 (testimony

of Attorney General Kennedy). The Supreme Court has

recognized that Congress intended to cover retail store

lunch counters, Hamm v. Rock Hill, 379 IJ. S. 306, 310

(1964) and that Congress was especially concerned with

the effect on commerce of racial discrimination in restau

rants, Katzenbachv. McClung, 379 U. S. 294, 299-301 (1964).

In view of this recognized congressional policy, food served

in the Y. M. C. A. must be deemed to have affected com

merce.

This Court may take judicial notice that coffee, tea and

bread ingredients originate without the State of Alabama.

13

Adams v. Fazzio Real Estate Co., 268 F. Supp. 630, 639

n. 18 (E. D. La. 1967) aff’d, No. 24825 (5th Cir., May

28, 1968); Kyles v. Paul, 263 F. Supp. 412 (E. D. Ark.

1967), aff’d, No. 18,824 (8th Cir., May 3, 1968) (petition

pending for rehearing en banc). As the only beverages

served in the Y. M. C. A .’s eating place are coffee and tea

and as the dinners consist of the regular plate (R. 117),

more than a minimal amount of the food served at the

Y. M. C. A. has undoubtedly moved in interstate commerce.

Thus the Y. M. C. A. is subject to Title II because it pro

vides lodging for transients and serves and offers to serve

food, a substantial portion of which has moved in com

merce, to interstate travelers.

Since the YMCA is a place of public accommodation

on all of the above grounds, it is a place of public accom

modation as to all services rendered within its physical

confines. Nesmith v. YMCA of Raleigh, North Carolina,

No. 11,931 (4th Cir., June 7, 1968); Pinkney v. Meloy, 241

F. Supp. 943 (N. D. Fla., 1965).

C. The authority of Nesmith v. YMCA of Raleigh,

North Carolina

This court has made it clear that Title II of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 is to be liberally construed so as to

effectuate its purpose of eradicating racial discrimination

in public accommodation. Miller v. Amusement Enter

prises, Inc., No. 24259 (5th Cir., en bam, April 8, 1968)

(slip op. 13) reversing 391 F. 2d 86 (5th Cir., 1967); Fazzio

Real Estate Co., Inc. v. Adams, No. 24825 (5th Cir., May

28, 1968). The only authority cited by the district court

in the instant case for its conclusion that the activities of

the YMCA do not affect commerce and are not open to

the public was Nesmith v. YMCA of Raleigh, N. C., 273

14

F. Supp. 520 (E. D. N. C., 1967) (R. 15). But the Nesmith

district court recently has been reversed by the Fourth

Circuit (No. 11,931, June 7, 1968).

Appellants urge that the application of standards set out

in the Fourth Circuit Nesmith decision makes it incon-

trovertibly clear that the Bessemer YMCA is covered by

Title II. For example, the district court found as a fact

that some 53% or 54% of the income of the Bessemer

YMCA is derived from the United Appeal (R. 12). In de

termining that the Raleigh YMCA was not a private club,

the Fourth Circuit put heavy reliance upon the fact that

more than 20% of the operating funds of the athletic

building was provided by the United Fund. Nesmith v.

YMCA of Raleigh, N. C., supra, slip op. 11.

The district court impliedly put some reliance upon the

fact that the facilities of the Bessemer YMCA are allegedly

not open to the public (R. 15). Support for the district

court’s conclusion is apparently contained in its finding of

fact that a person wishing to become a member of the

YMCA must file an application, which application is pur

portedly reviewed by a committee and the board of direc

tors (R, 13). Yet the record is clear, and the district

court found as a fact, that Steven Cotton, a white student,

was rented a room for $1.50 and that he attended a Lions

Club oyster supper—all with no hint that the YMCA made

any effort to bar him as a non-member (R. 14, 36-37). As

an indicium of how little membership in the YMCA meant

for a person who was white, Mr. Cotton was given a

receipt at the time he paid his $1.50, which receipt indi

cated that 50 ̂ was for membership.

15

In rejecting the contention that the Raleigh YMCA was

a private club in light of its requirements for applications

and review by a membership committee, the Fourth Cir

cuit significantly noted that it was “ admitted that there

are no prescribed or regularly used qualifications for

membership” and the court went on to conclude that, “ The

YMCA, with no limits on its membership and with no

standards for admissibility, is simply too obviously un-

selective in its membership policies to be adjudicated a

private club.” (Nesmith v. YMCA of Raleigh, North Caro

lina, supra, slip op. 10-11). We submit that the district

court’s reliance in the instant case upon the Nesmith dis

trict court was clearly misplaced in light of the disposi

tion made by the Fourth Circuit.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, we respectfully submit

that the judgment of the district court should be re

versed.

Respectfully submitted,

Norman C. A maker

J ack Greenberg

Conrad K. Harper

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

Oscar W. A dams, Jr.

H arvey M. B urg

1630 Fourth Avenue, North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Attorneys for Appellants

RECORD PRESS — N. Y. C. 38