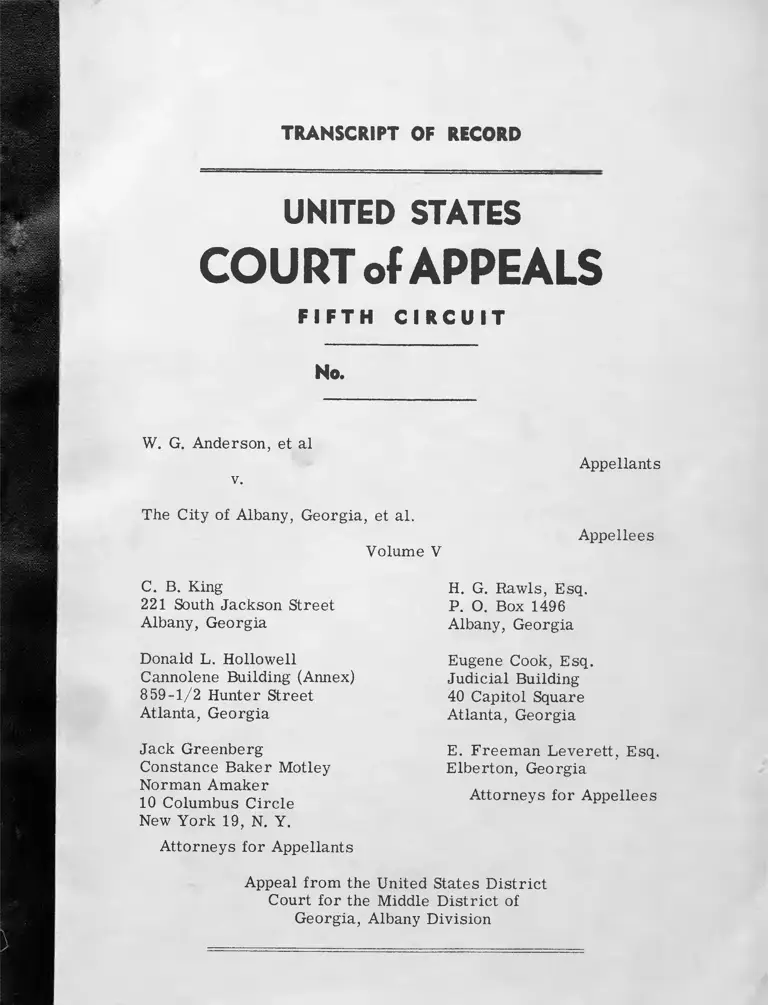

Anderson v. City of Albany, GA Transcript of Record Vol. V

Public Court Documents

August 30, 1962 - September 21, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Anderson v. City of Albany, GA Transcript of Record Vol. V, 1962. 8cf2b451-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0f9877c5-c048-450b-bd5c-5dd495dd6743/anderson-v-city-of-albany-ga-transcript-of-record-vol-v. Accessed March 01, 2026.

Copied!

TRANSCRIPT OF RECORD

UNITED STATES

COURT of APPEALS

F I F T H C I R C U I T

No.

W. G. Anderson, et al

v.

The City of Albany, Georgia, et al.

Volume V

Appellants

Appellees

C. B. King

221 South Jackson Street

Albany, Georgia

Donald L. Hollowell

Cannolene Building (Annex)

859-1/2 Hunter Street

Atlanta, Georgia

Jack Greenberg

Constance Baker Motley

Norman Amaker

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

Attorneys for Appellants

H. G. Rawls, Esq.

P. O. Box 1496

Albany, Georgia

Eugene Cook, Esq.

Judicial Building

40 Capitol Square

Atlanta, Georgia

E. Freeman Leverett, Esq.

Elberton, Georgia

Attorneys for Appellees

Appeal from the United States District

Court for the Middle District of

Georgia, Albany Division

I N D E X

(Volume V)

Page

HEARING ON MOTION FOR PRELIMINARY

INJUNCTION, NOS. 730, 731 ---------------------------- IB

Consolidation of Cases -------------------------- IB

Defendants' Motion to Dismiss-- ----------------- 13B

Correspondence: Court and Counsel -------------- 14b

Rulings on Motions -------------- ----•------------ 22B

Testimony of Mayor Asa D. Kelley, Jr.

(Adverse Examination)

Direct Examination-------- 24b

Cross Examination-------------------------- 60B

Redirect Examination----------- 80B

Recross Examination-------------- ---------- 92B

Redirect Examination ----------------------- 93B

Recross Examination------------------------- 943

Testimony of Mr. Ollie Luton

Direct Examination -------------------------- 96B

Cross Examination------------------------- 101B

Redirect Examination-- --------- 101B

Testimony of Dr. W. G. Anderson

(Recalled)

Direct Examination ---- --------------------- 102B

Cross Examination--------------------------- 112B

Redirect Examination ------------ -— -------- 143B

Recross Examination ------------------------ 151B

Testimony of Miss Ola Mae Quarterman

Direct Examination--------- ---------------- 155B

Cross Examination-------------------------- 159B

Testimony of Miss Patricia Ann Gaines

Direct Examination I63B

(Volume V - continued)

Page

Testimony of Mr. Charles Jones

Direct Examination ------------------------- 167B

Cross Examination -------------------------- I69B

Testimony of Miss Osie LeVernette Wilson

Direct Examination ------------------------- I78B

Cross Examination-------------------------- I83B

Testimony of Dr. W. G, Anderson

Recross Examination ------------------------- 186b

Plaintiffs' Exhibits Introduced------------- ---- 1883

Future Setting of Hearing----------- ------------- I96B

NOTICE OF DISMISSAL ----------------------------------- I98B-A

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730,731 IB

ALBANY, GEORGIA

2:00 P.M ., AUGUST 30, 1962

THE COURT: I call for hearing at this

time Civil Action No. 730 and Civil Action No.

7 3 1, which will be heard jointly, concurrently.

Will counsel who represent Plaintiffs in these

two cases identify themselves for the record at

this time?

* * * * * * * *

(Introduction of Counsel)

Mr. Rawls:

Your Honor, in connection with the consoli

dation of the cases for the purpose of trial,

counsel for the Defendant would like to suggest

that all three of the cases be consolidated

together, inasmuch as our complaint in 727 is

identical to our cross-action in #7 3 1; and we

think it would be entirely consistent, since

Your Honor has already indicated that you

intend to consolidate 730 and 7 3 1, to also

consolidate them with #727.

I believe that would be in keeping also

with the motion which was filed by counsel for

the Plaintiffs in these other two cases during

the progress of the trial of #727- A written

motion was filed to consolidate all three cases.

I think that motion was verbally withdrawn but,

after all, it Is the original motion which was

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730, 731 2b

filed in this case. And as I stated, our

position in our cross-action in #731 is identical

and almost verbatim the same thing setup by way

of cause of action by the Plaintiffs In #727;

and the judgment in #731 could completely elimi

nate whatever questions might be presented in

#727.

MRS. MOTLEY: May it please the Court, I

would like to have the record clarified with

respect to our objection to the consolidation

of 730 and 731 which are now before the Court.

Your Honor may recall that Mr. King, Attorney

for the Plaintiffs, corresponded with Your Honor

prior to this hearing, Indicating our desire

to have 730 heard separately on our motion for

preliminary Injunction.

Now, we feel that the consolidation of

730 with 731 prejudices our right to a prompt

hearing and determination of our motion in 730.

As Your Honor knows, we filed 730 on July 25 of

this year5; and when we filed the complaint, we

filed with It a motion for preliminary injunc

tion. It Is our understanding that when such a

motion is filed we are entitled to as prompt a

hearing as the Court can give in that case.

We feel that the facts In that case are

not really In dispute. Your Honor may recall

that on the trial of 72-7, the Mayor testified

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction* Nos.730*751

that he had received the petition from the Albany

Movement* requesting desegregation of the public

facilities listed therein; that no action had

been taken by the City* and he suggested to the

petitioners that they go to the Federal Court.

So that, there is no dispute as to the

facts in 730. Moreover* the law with respect

to public facilities* as Your Honor knows*is

well settled by many decisions of the United

States Supreme Court and the Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit. So, there's no doubt as

to the law applicable to those undisputed facts.

Now* when you have a case where the facts

are not In dispute and the law is settled* there

is no discretion to deny a preliminary injunction;

and to consolidate that case with #7 3 1* or at

this point with #727* would obviously prejudice

the rights of these Plaintiffs to a preliminary

injunction In that case. And for that reason we

do not think that this Is a proper case for proper

exercise of this Court's discretion under Rule 42

about consolidating cases* as it will clearly

prejudice our right to preliminary Injunction

with respect to public facilities* which we seek

to have desegregated in #730. And so* with respect

to that* we would like for the record to show

that we request this Court to separately hear

and determine our motion for preliminary Injunc

tion in #730.

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730*731

4b

THE COURT: Well, as I indicated in my

correspondence with counsel at the time that I

set these matters down for hearing at this time,

it is the Court's view that the two actions,

730 and 73 1, spring out of the same set of

circumstances and the same overall situation,

and in large degree even involve the same parties,

though, of course, not Identical in all respects.

I "believe there is one Plaintiff In one case

who is not a plaintiff in another case; but

other than that, the cases spring out of the

same general set of circumstances and involve

the same general situation; and In a good many

instances Involve the same sort of evidence and

the same sort of presentation.

Acting under the authority vested in the

Court under Rule 42, It was my thought and it

is still my thought that bo expedite and save

costs and save time, which is the purpose of the

Rule, it is appropriate that 730 and 731 be

consolidated for the purpose of trial, for the

purpose of hearing, and save us all a lot of

time; and I don't believe, if it delays at all,

that it will very greatly delay a decision in

any of the cases. But that is the Court's view

and that's what we will do.

Now also, the Court does recall at one

stage of the proceedings In Civil Action 727,

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730,731

Counsel for the Defendants In that case, who are

counsel for the Plaintiffs In this case, suggest

ed that 727 be consolidated with 730 and 7 3 1;

and we were on the verge of doing that when

counsel withdrew the request orally. I believe

the statement was that she did not want to insist

upon it. At any rate, we did not do that at that

time. But the Court made the observation at that

time that we might later feel that it would be

wise to consolidate all three for the purpose of

hearing to accomplish the general purposes

envisioned by the adoption of Rule 42.

I had wondered whether either side might

suggest today that, since we have taken a lot of

testimony in 727 and the case is not yet decided

by the Court, I had wondered whether counsel for

either side might at this time suggest that,

for purpose of further hearing, that case be

consolidated with 730 and 731.. In order to avoid

the necessity of the introduction of a great deal

of evidence in these cases which has already been

covered In 727.j because by doing that, the record

in #727 could be used as the record In these

cases also.

I had decided In my own mind that If nobody

suggested it, I was going to raise the question

myself. Now that it has been suggested by

counsel for the Defendants in these cases and

6b

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730,731

since I have announced my intention to consoli

date 730 and 731 for the purpose of hearing, I

wonder If counsel for the Plaintiffs in 730 and

731 might now concur in the suggestion that 727

be consolidated, in order that all of the evi

dence introduced there might come into consider

ation In these two cases?

MRS. MOTLEY: In reply to that, sir, I

would like first to clarify the record as to

what we sought by way of consolidation in 7 2 7.

At that time you may recall that we had filed a

motion to consolidate but I amended the motion

In effect by saying that what we sought was

consolidation of our motion for preliminary

injunction in 730 and 731 with the hearing that

was then going on. Again, the purpose of that

was to protect our rights to an early hearing

and determination of those motions.

But the Court was of the .view that these

cases or those cases should have been consoli

dated with 727 for the purpose of trial, which

would have necessitated a delay until the

Defendants had answered in 730 and 731. It

was at that time that I said that we did not

desire a consolidation of these cases for the

purpose of trial, that we desired it for the

purpose of motion for preliminary injunction

in 730 and 731} and the Court ruled that that

would not be consolidated for the purpose of

7B

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730,731

hearing the motion for preliminary injunction

in 730 and 731. That's the way I understood the

Court to rule; that you were overruling our

request for a consolidation of the motions for

preliminary injunction in 730 and 731 and insist

ing upon consolidation of the three cases for trial.

Now, with respect to testimony which has

already been adduced as to 727, I think that that

testimony is only relevant to our case 731, in

which we seek to enjoin interference with peace

ful picketing. We object to the placing of

that testimony In 730, because 730 is a very

simple action for desegregation of public

facilities and it's quite aside from the right

to picket and to demonstrate against segregation,

which are separate rights flowing from the First

Amendment to the Constitution and protecting

against state interference by the due process

clause of the l4th Amendment.

But the case involving the public facilities

is a simple case involving the equal protection

clause of the l4th Amendment. There Is no doubt

as to the law in that area but there certainly

is considerable doubt as to what is peaceful

picketing and what is a demonstration protected

by the First Amendment to the Constitution and

the l4th Amendment to the Constitution.

8b

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730,731

So that, we object to the placing of the

testimony in 727 in 730 because it would becloud

a simple and clear Issue on which this Court can

promptly rule.

THE COURT: Well, at the time the Court

makes a decision in the case the Court will make

every effort to avoid being influenced in the

decision of any one of those cases by any evidence

which is In the record which is not pertinent to

that case, and the Court will make every effort

to do that. But I do think that it would greatly

expedite this proceeding and will probably result

in an earlier decision of all of the matters

if the record In 727 is consolidated with 730

for the purpose of hearing, if the record in

that case, all evidence Introduced In that case,

could be considered as having been introduced in

these cases, and such parts as may not be per

tinent to consideration of one case or the other,

the Court will attempt to exclude that from its

consideration at the time.

MR. HOLLOWELL: Your Honor, may we have

just a second?

THE COURT: Yes...........

MRS, MOTLEY: What we would like to do at

this point is move for a continuance of the

hearing in #731 and proceed now with the hearing

on our motion for preliminary injunction In 730

9B

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730,731

for the same reasons which we gave before, because

we think that 730 is a simple case involving the

equal protection clause of the l4th Amendment,

in which there is no dispute as to the facts

and the law is well settled and we are entitled

to a preliminary injunction in it.

THE COURT: All right, I overrule the

motion and we will proceed with the hearing of

the three cases 727, 730 and 731 being consoli

dated for the purpose of hearing, but not con

solidated for the purpose of decision. By that

I mean to make it clear that the Court may,

after the conclusion of the hearing, decide one

case at one time, another at another time and

another at another time or may decide all three

at one time.

But for the purpose of hearing the cases

are consolidated.

Now, I notice in Civil Action No. 730 —

MR. HOLLOWELL: Pardon me, if I might Your

Honor: Counsel Is not clear, at least I am not,

as to the distinction which the Court might be

making in the use of terms when the Court says

"hearing"? Is the Court referring to the hear

ing on the motions for preliminary injunction?

In 731 an answer has been filed; In 730, no

answer has been filed. We presume that the

hearing would be on the motions for preliminary

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos,730.,731

10B

injunction but I am not clear in my own mind as

to what the ultimate decision of the Court has

been in connection with this matter?

THE COURT: I shall try to make it clear:

There is a motion for preliminary injunction

in Civil Action 730. There is a motion for

preliminary Injunction In Civil Action 731.

There is a question of preliminary injunction

remaining undecided,, the record still being open.,

in Civil Action No. 727. So., we will now proceed

with the hearing with regard to the motions for

preliminary injunction in all three cases.

MR, RAWLS: Now, if Your Honor pleases,

I think under the rules a motion that we have

filed in 730, or motions rather, being a motion

to dismiss and a motion for more specific and

definite allegations, would take precedence over

any other motion.

THE COURT: Yes, I was coming to that next

as soon as we got the question about procedure

out of the way.

MRS. MOTLEY: May it please the Court, I am

sorry to have to be up again, but we do have

another motion we would like to make with

respect to these cases. We would like to move

the Court for an order dismissing #731 pursuant

to the provisions of Rule 4l.

113

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos,730,731

THE COURT: Well, that is the case, I

believe, 731 in which the Defendants have filed

a cross-action, is it not?

MR. RAWLS: Yes, Your Honor.

MRS. MOTLEY: That's right.

MR. RAWLS: Of course, we object to the

granting of the motion of Plaintiffs In that

case to dismiss, on the ground that our cross

action might go out with that dismissal; and

we don't think they have a right to dismiss it

and prejudice our rights.

THE COURT; In other words, the Defendants

object to the dismissal of that action?

MR. RAWLS: Yes sir.

MRS. MOTLEY: Well, we think, as Your Honor

has already pointed out, that crossaction has

really been tried before this Court, the cross

action in 731 has been substantially tried here,

and I can’t think of any further testimony that

we could put on. The only thing we were .going

to do with respect to 731 was to put In the

record those arrests that were made for what we

considered peaceful picketing and peaceful

attempt to use the library and so forth. That

is a matter of record here in the Recorder's

Court or ’whatever the Court is, and this Court

has heard the evidence in that case and I think

to try that case would certainly be a 'waste of

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730,731

1.2B

this Court's time and expense, because there Is

no further evidence for either side to be put

in on this question.

THE COURT: Of course, what the parties

might offer in evidence is something that the

Court cannot know and, since the Defendants,

who have filed a crossaction, are objecting

to the dismissal of the case, of course, the

Court overrules the motion to dismiss.

Now, in Civil Action 730* the Court notes

that the Defendants in that case have filed

certain motions and It would be appropriate at

this time to take up and dispose of those motions

before we go further.

MR, RAWLS: Now, If Your Honor please,

these motions invoke rather technical legal

points and I have asked my two young associates

with Your Honor1s indulgence to go into as much

detail as the Court will permit in presenting

our legal theories on the motions.

MRS, MOTLEY: In order to save time, Your

Honor, I would like to say this: We are willing

to give them a more definite statement, every

thing they have asked for we are willing to give

them; so, they don't have to argue that.

MR. RAWLS: If Your Honor please, we

prefer to conduct our side of the case according

to our own views. I will ask Mr. Burt to submit

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction,, Nos.730, 731

our presentation.

It has been called to my attention, if

Your Honor pleases, that the Plaintiffs are in

default as to our crossaction in 731 and we

move the Court to enter a default judgment in

that case. The rules gave them twenty (20) days

I believe to file an answer to our crossaction

and none has been filed; and we have presented

and filed with the Clerk the affidavit required

under the Rules and we ask the Court to direct

the Clerk to mark that case in default.

MR. LEYERETT: May it please the Court,

the case has already been marked in default

pursuant to the rules and we are asking at this

time for a judgment on our crossaction in 731*

for the purpose of the record.

THE COURT: All right, go ahead. I will

rule later on that motion.

MR. BURT: May It please the Court,

in #730 the Defendants have filed a motion to

dismiss and I would like to present this motion

at this time.

* * *

(Argument on defendants' motion to dismiss)

All right, now, Is there any further argument

in connection with the motion from the Defendants,

in connection with support of your motion?

i4b

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction* Nos.730*731

MR. BURT: No sir* that completes our motion*

Your Honor please.

THE COURT: All right* I will hear from

counsel for Plaintiffs.

MRS. MOTLEY: May it please the Court* I don’t

know whether the argument is part of the record in this

case but before I proceed to answer the motion to djsirdss

here* I want the record to show that the Defendants in

730 were permitted to argue for more than two hours on

a motion to dismiss.

* * *

(Further argument on motion to dismiss)

THE COURT: Allright* I'll let you have my

views on your motion when we reconvene in the morning

for further proceedings. We will take a recess now until

tomorrow morning at 9 3̂0.

5:05 P. M.* AUGUST 30, 1962: HEARING RECESSED

9:30 A.M .* AUGUST 31, 1962:

MR. RAWLS: Your Honor pleases* at the close

of the session yesterday afternoon* counsel for the

Plaintiffs took occasion to state into the record the

length of time which was consumed by my associate* Mr.

Burt* in reading what vie regarded as applicable prin

ciples of law In connection with our motion to dismiss

and for a more definite statement.

In the 45 years that I have been at the Bar

that’s the first time a situation like that has developed

and I don't know the connotation; I don’t know why

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730^731

15B

that had to be stated into the record. But since it

has been stated, I desire to state a matter into the

record.

On August l4, 1962, Attorney C. B. King addressed

a letter to Your Honor, a copy of which was sent to

Attorney Motley and Attorney Hollowell, which I desire

to read into the record:

"Honorable J. Robert Elliott, United States District

Judge For the Middle District of Georgia, Columbus,

Georgia: Re: Civil Action No. 730, Temporary Injunction

sought for desegregation of public facilities in the

City of Albany. Dear Judge Elliott:

"Your attention is called to the above subject case

now pending in the Albany Division.

"Though I recognize that your Court schedule is

perhaps congested, I am yet interested at this time, if

at all possible, In a determination by the Court of

the earliest possible time at which a hearing on said

case might be had. My principal concern, in this

matter, addresses itself to the facilities case, No.

730, and not to Civil Action No. 7 3 1.

"Please advise this office of the earliest possible

date on which the Court will be able to hear said

matter.

"With every good wish, I am, Very truly yours,

C. B. King", copies to Mr. G. H. Rawls, Attorney at

law; copy to Mrs. Constance Baker Motley, Attorney at

Law; and copy to Mr. Donald L. Hollowell, Attorney at

law."

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730,731

i6b

In response to that letter, on August 17* Your

Honor addressed this letter to all counsel of record,

addressed to all counsel of record: C. B. King, 221

S. Jackson Street, Albany, Georgia; Mr. Donald L.

Ho Howell, 859 i Hunter St. N. W., Atlanta, Georgia.

Mr. Jack Greenberg, 10 Columbus Circle, New York,

N.Y.j Mrs. Constance Baker Motley, 10 Columbus Circle,

Newr York, New York; Mr. William M. Kunstler, 156 Fifth

Avenue, New York, N. Y.; Mr. Clarence B. Jones, 500

Fifth Avenue, New York, N. Y., Mr. H. G. Rawls,

P. 0. Box 1496, Albany, Georgia; Mr. Eugene Cook,

Judicial Building, 40 Capitol Square, Atlanta, Ga.;

Mr. E. Freeman Leverett, Elberton, Georgia; Mr. Jesse

W. Walters, Perry, Walters & Langstaff, Albany, Georgia;

:"Re: W. G. Anderson et al v. City of Albany"

MRS. MOTLEY: Excuse me, Mr. Rawls, excuse me,

Your Honor: In order to save time, we are agreeable

that all of those letters go Into the record, Your Honor.

We think they ought to be In there if that's what he

desires, rather than reading them into the record.

We agree that they ought to be in there and we think

they ought to be made a part of the record in this case.

THE COURT: Well, apparently he intends to

have some comment to make about them. You may go ahead,

Mr. Rawls.

MR. RAWLS: "Mr. Jesse W. Walters, Perry,

Walters & Langstaff, Albany, Georgia. Re: W. G.

Anderson, et. al. v. City of Albany, et. al., Civil

i?B

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730,731

Action No. 730, Albany Division; W. G. Anderson, et. al.

v. City of Albany, et. al., Civil Action No. 731*

Albany Division. Gentlemen:

"I now wish to inform counsel concerning the

earliest time at which the above identified matters can

be heard. Next week, that is the week of August 20, is

out of the question because the court is otherwise

obligated.

"For the first 3'k days of the week of August 27 we

will be engaged in disposing of the criminal arraign

ment calendar and holding pre-trial conferences in

connection with the civil cases to be tried at the

regular term for the Columbus Division of this court.

The last pre-trial conference Is set for 10:00 a. m.

on Thursday, August 30. That matter will be concluded

in time for me to be in Albany by 2:00 p. m. on that

date, August 30, and it would be possible for us to

begin the hearing on these matters at that time and

we could devote the remainder of that day and all day

Friday, August 3-1* to them.

"The regular term of the Columbus Division of

this court convenes on Tuesday, September 4. Monday,

September 3* is Labor Day. It is anticipated that the

Columbus term of court will require three weeks. This

means that If we were unable to complete the trial of

these matters on August 30 and 31 as above mentioned, it

would be necessary that we recess the hearing until

sometime during the week of September 24 and resume it

i8b

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction* Nos.730,731

"at that time. The court will be in Albany the .first par

of that week for the purpose of conducting pre-trial

conferences in connection with civil cases to be tried

at the regular Albany term of Court which convenes on

Monday* October 1. These pre-trial conferences in

Albany will probably not require more than 1 or l|-

days* and that means that we would have about 3 -̂ or

4 days available for the trial of these matters at that

time and could doubtless conclude them before it became

necessary for us to convene the regular term of the

court at Albany on Monday of the following week.

"An answer has not yet been filed in Civil Action

No. 730* but I anticipate that when an answer is filed

it will be apparent that Civil Action No. 730 and Civil

Action No. 731 should be consolidated and tried together

and It is my intention that this shall be done. I men

tion this now because this will certain affect the time

required for the trial of the cases. Counsel for the

parties in the respective cases know better than the

court does how many witnesses will be used and how much

evidence will be presented and you* therefore* probably

have a better idea about the time which will be required

to try these cases than does the court.

"What I suggest and request Is that counsel for

Plaintiffs and Defendants confer among yourselves and

decide whether you think It best to begin the trial of

these matters at 2:00 P. m. on August 30 and go as far

as we can with the hope of being able to conclude them*

Hearing on Motion for Preliminary Injunction* Nos.730*731

"or whether it would be better to take them up during

the week of September 24* when we could conclude them

with knowledge that it would not be necessaryto recess

the hearing. I wish to make it clear that I have no

objection to beginning the hearing on August 30* even

though it does necessitate recessing it for completion

on a later date. The court is willing to accommodate

itself to the wishes of counsel insofar as possible,

may be that some of counsel have conflicts which will

make it impossible to consider any of the dates which

I have suggested. If that develops* then I suppose

the only thing we can do is put the matters down for

hearing during the regular course of the term for the

Albany Division which convenes on October 1* and that

is normally what I would do In a situation of this type

but I have In mind* as counsel for the parties doubtles

have* that It is entirely possible that an earlier

hearing on these matters might contribute something

to calming the troubled waters which are known by all

of us to exist. It is for this reason that I am sug

gesting the earliest possible dates instead of waiting

until the regular Albany term.

After counsel have conferred please let me hear

from you at your earliest convenience."

Now* if Your Honor pleases* responsive to that

letter* which Is dated August 17* on August 18* without

conferring with me and* as far as I know* any other

2 OB

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary injunction, Nos.730,731

"attorney representing the other side of these cases,

Attorney King wrote this letter:

"Honorable J. Robert Elliott, Judge, United States

District Court, For the Middle District of Georgia,

Columbus, Georgia. Re: W. G. Anderson, et. al. v. City

of Albany, et. al., Civil Action No. 730, Albany Division

W. G. Anderson, et. al. v. City of Albany, et. al.

Civil Action No. 731, Albany Division.

Dear Judge:

"Thank you for your letter of August 17, 1962.

Responsive to same please know that counsel for plain

tiffs acknowledge the obviously congested schedule

under which Your Honor is presently burdened. However,

out of our concern for fulfilling what we believe to be

an appropriate demand of the public Interest, as well as

the right of the plaintiffs to a speedy hearing and

determination on their motion for a preliminary Injunction

pursuant to Rule 65 of the Federal Rules of Civil Proced

ure, we are respectfully Insisting upon a hearing and

determination on the motion for a preliminary Injunction

in Civil Action No. 730 dealing with the desegregation

of public facilities, at 2:00 P.M. on August 30, 1962.

"As was previously indicated, counsel for

plaintiffs would not, on the above date, be seeking

a hearing on the motion for a preliminary Injunction

In the picketing complaint, Civil Action No. 731, but

would seek a hearing thereon at a.time subsequent."

21B

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730,731

"Now, if Your Honor pleases, that was stated

after Your Honor had stated that you intended to

consolidate the two cases ana that, as I say, without

any consultation at all with other counsel, as far

as I know, and I know not with me; and as far as I

have been able to learn with any other counsel connected

with the case or any other party connected with the

case. And he concludes the letter like this:

"If the Court's thinking in this matter is at

variance with that of counsel, we respectfully request

to be Immediately advised in order that we may proceed

to seek to secure the right of plaintiffs to a prompt

hearing and determination on their motion for a pre

liminary injunction in Civil Action No. 730, by applying

to the Chief Judge of the District, or Chief Judge of

the Circuit for the appointment of another Judge whose

court calendar is less incumbered. Respectfully yours,

C. B. King, of counsel. Copy, Honorable Elbert P. Tuttle,

Honorable W. A. Bootle, Mr. H. G. Rawls, Attorney at Law,

Mr. Donald L. Hollowell, Attorney at Law, Mrs. Constance

Baker Motley, Attorney at Law."

Now, If Your Honor pleases, that may or may not

be an effort at intimidation. It sounds to me like it's

an attempt to intimidate somebody and I hope he's not

undertaking to intimidate this Court. I wanted the record

to show that, in response to the remark that counsel

made concerning the length of time that we consumed

22B

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730,731

without any interference in presenting what we regarded

were the pertinent legal principles involved on our

side of the case.

THE COURT: All right.

MR. KING: If Your Honor pleases, responding

to counsel, to the comments of counsel, opposing counsel,

I would first of all like to address myself to the Court

and make It eminently clear that, notwithstanding the

unsavory construction imposed upon his letter by

opposing counsel, counsel had no intention of Intimidating

or doing any other thing that might even import an

inference of insulting the dignity of this Court.

THE COURT: Well, whatever -- I think nothing

further need be said along this line. Whatever the

Intention might have been, the tone of the letter

and the fact that copies were sent to the Chief Judge

of the Fifth Circuit and the Chief Judge of this

District, whatever the intention may have been, I can

assure counsel for Plaintiffs and counsel for the

Defendants that this Court is not Intimidated, nor can

this Court be intimidated.

Now, at this time I want to comment on the motion

which was heard on yesterday. At this time I sustain

the Defendant's motion to strike the City of Albany

as a party Defendant in Civil Action No. 730, and the

City of Albany is eliminated as a party Defendant.

I am going to defer ray ruling on Defendants ’

motion for entry of judgment on their cross-action

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730^731

23B

in Civil Action No. 731 for later decision.

I am going to defer a ruling on Defendants'

motion to strike Count Five of the complaint in Civil

Action No. 730 for later decision.

I am also going to defer a ruling on Defendants’

motion to dismiss Civil Action No. 730 for later

decision.

The reason I do that is because counsel for both

Plaintiffs and Defendants cited and read from in some

instances some cases with which the Court is not

familiar to the extent of having read them. I would

prefer to have the benefit of a complete reading of

some of those cases myself, rather than relying just

upon the excerpts that were read by counsel.

For that reason, desiring to give a more complete

study than I have been able to do in the short time

that I have had since the motions were filed, I want

to defer a ruling on those motions, and I am deferring

ruling on those motions until a later time.

Now, of course, at that point we might simply

recess this matter until I made a ruling but I do not

wish to do that. We will proceed with the hearing on

these cases subject to my subsequent ruling on the

motions to which I have referred.

Counsel for the Plaintiffs may now proceed.

MRS. MOTLEY: May it please the Court, yesterday

in my argument I overlooked the Defendants' motion for

a default judgment. I had Intended to comment at that

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730,731 24b

time on it. I had intended to point out that the

crossclaim in 731 is identical with the affirmative

complaint in 727. We filed an answer in 727 after the

crossclaim was filed and we, as you know, tried to

consolidate those cases; and it was our Intention that

the answer filed in 727 would be the answer to the

cross-claim, as it was identical; and it would certainly

burden the record to file two answers saying the same

thing. So that, we would move the Court for leave to

consider the answer filed In #727, if the Court con

siders an answer to that crossclaim necessary, in that

case. I don't think it's necessary, as I say, because

we had filed an answer in the other case which was the

same thing; and if the answer Is technically necessary,

then, we would ask the Court to consider the answer

in 727 as the answer to the cross-claim.

My first witness today is Mayor Kelley, Your

Honor.

MAYOR ASA D, KELLEY, JR,

a party Defendant, called as

adverse party by Plaintiffs,

being first duly sworn,

testified on

ADVERSE EXAMINATION

BY MRS. MOTLEY:

Q Would you please state your full name for the

record, sir?

A

Q

A

Asa D. Kelley, Jr.

Are you the Mayor of the City of Albany?

I am the elected Mayor of Albany.

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730,731

25B

Q How long have you been the Mayor of the City of

Albany?

A Since January of i960.

0. Then, you were the Mayor of Albany in November,

1961, were you not?

A I was.

Q Do you recall that in November, 1961, Dr.

Anderson, who is the President of the Albany Movement,

presented you with a petition regarding desegregation of

public facilities in the City of Albany?

A Dr. Anderson from time to time has presented

several petitions. I do not recall the exact dates of any

of them but I think it is a fair statement to say that during

the month of November, of '6l a petition was presented.

Q Regarding public facilities in the City of Albany?

A Yes, as a matter of fact, my recollection is that

the demand was for desegregation of all facilities, all

public facilities; and it also Included the library, which

is controlled by a board of trustees,* the hospital, which

is controlled by a hospital authority; and they sought

municipal employment in all areas with emphasis and priority

on the police force and utilities. And in that connection

I think at that time or shortly thereafter, applications

were made by some 2 or 3 members of the Negro community -

Chief Pritchett can give you the exact dates, I don't know -

and none of these applicants have passed the examination.

As a matter of fact, the scores, I think, were less than

35 or 40 for each one of them.

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730,731 26b

In addition, Dr. Anderson wanted jury representa

tion. Of course, we have no control over the petty of

grand juries in the Superior or City Court of Albany.

That’s a matter exclusively - which addresses itself

exclusively to the respective courts.

And then, he also wanted job opportunities in

privately owned facilities catering to the Negro trade.

It has always been the policy of the City not to Interfere

with private business, if at all possible to avoid such

interferencej and, of course, the City has no jurisdiction

over how and In what manner a privately owned business is

operated,’ but that is a matter which, in my judgment,

addresses itself to the owner or proprietor of the facility.

I have a copy of this November 17 demand, which

apparently comes from W. G. Anderson, Chairman and M. S.

Page, Secretary, of the Albany Movement; but he purports to

represent the Youth Council, the Ministerial Alliance, the

Criterion Club, the Federated Women’s Clubs, the Student

Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, the Negro Voter League,

and the Naacp.

MRS. MOTLEY: May it please the Court, this is

a certified copy of the petition presented In the other

case and I suppose we can have It re-marked for this

case.

THE COURT: Suppose, Mr. Clerk, since it is

in evidence in the other case, that you leave the

designation which was placed on it in that case;

in other words, make some Indication about the case,

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730,731

the case number, when you identify it for this purpose

to distinguish it from its evidentiary value In the

other case.

MR. RAWLS: Your Honor, she states this is a

certified copy; I wonder by whom?

MRS. MOTLEY: Well, I believe it’s the Clerk,

Mr. Cowart, the Clerk of the Court.

THE COURT: Oh, I misunderstood counsel's

statement. This is not the same Instrument —

MRS. MOTLEY: Yes It is.

THE COURT: It Is the same instrument that

was Introduced in the other case?

MRS, MOTLEY: That's right, and we asked the

Clerk to copy it and has identification on It but I

suppose It should

this case.

be marked in 730, as an exhibit in

THE COURT: Well, let me see it, just a

minute. I'm not sure that I understand. . .Well,

it's a different piece of paper; In other words, this

Is a certified copy?

MRS. MOTLEY: Yes.

THE COURT:

introduced?

Of another paper which was

MRS. MOTLEY: Yes, that's right.

THE COURT: It's not the same piece of paper?

MS. MOTLEY: No sir.

THE COURT: Well, there can't be any confusion,

I thought it was the same paper

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730,731

28b

Q Mrs. Motley: Mayor Kelley, I would like to

show you PLAINTIFFS' EXHIBIT No. 1 for identification, and

ask you if this is the same petition which you have in your

hand or a copy of it?

A It appears to be the same, yes.

Q Now, directing your attention to this petition,

Mayor Kelley, I would like to ask you, do you have any

publicly owned parks in the City of Albany,

A We do have.

Q What are the names of those parks?

A We have Tift Park, Tallullah Massey, Carver

Park, and numerous smaller parks which are used primarily

for neighborhood gatherings and small groups of people

interested in athletics, the number of which I do not know;

but there are many such parks throughout the City of Albany,

both for use - used by both the Negroes and the whites.

Q Under whose jurisdiction are the public parks

in the City of Albany?

A Under our form of government which Is known as

a city manager form of government, the City Manager Is

charged with the responsibility of the operation of all

of the facilities of the City, Including the parks, and

excluding the water, gas and light department, which is

managed by another person. The person responsible to Mr.

Roos, the City Manager, insofar as recreation is concerned,

is Mr. Rod Blalock. The maintenance of the parks Is carried

out by Mr. Wills.

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730,731 29B

Q Is there a recreation committee of the Board of

City Commissioners?

A There Is a committee, the title of which I believe

is Parks and Recreation Committee.

Q Who is the chairman of that Committee?

A I think that Mr. Mott, Commissioner Mott, is

the Chairman. I ’m not sure. I know that Commissioner

Collins, Mayor Pro-Tern Collins was chairman last year but

I revised the committee assignments In January of this year

and I don’t recall; but I think that It's Commissioner Mott

from the Second Ward.

Q Now, what’s the function of that Committee?

A The function of any City Commissioner, including

the Mayor and the Mayor Pro-Tem, is simply to formulate

policy and to communicate that policy to the City Manager,

who has the responsibility of operating the City in accord

ance with the policy established by the Commission.

Q So that, the function of this Recreation

Committee of the Board of City Commissioners, of which

you are a member as the Mayor and the Mayor Pro-Tem is

also a member, Is to determine the recreation policy of the

City of Albany?

A And to make recommendations to the City Commission

for the adoption of an over-all policy. The Committee itself

has no authority to establish a policy but simply to

Investigate and to determine, from talking to people involved

and witnesses, the best policy to be adopted by the City

Commission. A recommendation is then made to the City

30B

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730^731

Commission and the City Commission as a whole either adopts

or rejects the recommendation of the committee. And the same

is true of any other facet of the City government.

Q What is the policy of the Board of City

Commissioners with respect to these parks, as relates

to their use by Negro and white citizens of the City of

Albany?

A We have, I suppose, one of the finest zoos

anywhere in the South and a playgrourd area, which to

my knowledge or as far as I know, has never been segregated.

The Negroes and whites have always been free to go to the

zoos in that area, to visit there and look at the animals

and what not.

The policy, insofar as the mechanical rides

is concerned, is that the Negroes may, if they wish to

pay the price, ride on the rides, I do not know whether

they have utilized them. I haven’t been to the parks

recently. We have many picnic tables and areas which

are used for cooking.

We have established a policy of permitting the

concessionaire the authority to assign these tables. They

are assigned on the basis of the number of people, whether

or not children are involved, and the period of time the

people making application for the tables want to use them.

These facilities have been used by both Negro and white on

the basis of assignment by the Concessionaire based on the

items I ’ve just outlined.

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730,731

313

We also have a swimming pool at Tift Park,* we

have one at Carver Park for the Negroes. I am informed

and believe that no Negro person has ever asked to be sold

a ticket at the ticket counter at the white pool. There

have been Negroes present at the park but none have actually

requested that a ticket be sold at the ticket counter,

according to my best Information.

Any other areas you would like for me to cover

on this?

Q, Well, let's find out first whether you have a

written policy of the Board of Commissioners regarding the

use of Tift Park by Negroes and whites?

A There Is no ordinance, to my knoivledge, on the

books relative to the use of recreational facilities by

Negroes and whites.

Q Is there a resolution of the Board of City

Commissioners regarding this policy?

A If there is, I'm not aware of it.

Q Are you aware of any written policy regarding

Tift Park or any other part in the City of Albany?

A I am not.

Q Now, with respect to the swimming pool in Tift

Park, Is it your testimony that Negroes are permitted to use

that pool?

A That Is not my testimony. My testimony is that

no Negro has ever tried to purchase a ticket to be used for

admission to the pool at Tift Park.

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730,731

32B

Q All right, now let me ask you, what is the

policy with regard to the use of that pool by Negroes?

A What is the policy?

Q Yes?

A I don’t know that the City Commission has ever

formulated any policy by resolution or ordinance. However,

in my judgment, because of custom and because of longstanding

agreement between all of the citizens in the community, the

white pool or pool for whites at Tift Park would be used

exclusively by whites and the one at Carver Park would be

used exclusively by the Negroes.

Q, All right, so it’s your testimony that in the

City of Albany, there is a custom, you say, on the part

of the citizens of the City that Tift Park pool is limited

to whites and Carver Park pool is limited to Negroes, Is

that it?

A Yes, that's true, and it has been true since

the pools were constructed. And the same is true of the

Teen Center. We have a teen center at Carver Park for the

Negroes and we have a teen center at Tift Park for the

whites; and the same is true for many other facilities.

Q, What other facilities?

A Pardon?

Q What other facilities?

A Recreational facilities. They use Carver Park,

The Negroes do, the white use Tift Park, but there are

other parks in the City being used by the Negroes.

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730,731

333

Q, Do you know when Carver Park was built for

Negroes?

A I do not know when the park was built. I know

that the Teen Center was dedicated during the administration

of Mr. Bill McAfee, which was some five years ago. But

now, when the Carver Park Itself was actually developed and

the pool put In, I just simply do not recall.

Q In addition to the pool and the teen center,

do you know of any other facilities at Carver Park?

A To my knowledge, no, because I have not actually

observed any other facilities except, of course, the swings

and the ordinary playground equipment, and the hobby shop,

which is located in the teen center, In the rear of the

teen center, and which has been used quite extensively by

the Negro community, as has the hobby shop at Tift Park

which has been used quite extensively by the white community,

both children and adults.

Q, Now, the trains which you have in Tift Park,

do you know whether they have trains of that kind In Carver

Park?

A I have never seen any there. Nor do I recall any

request by any person who owned such equipment for permission

to operate at Carver Park. I'm sure that If a person who

owned such equipment would want to place It at Carver Park,

the City would be glad to grant them permission to do so;

of course, subject to the regulations established by the

City Manager as a result of policy established by the City

Commission, insofar as it relates, say, to the price of

Hearing on Motion for Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730,731

34b

the ride. The City Commission has established the price

of the rides to be what we think is low enough to encourage

children to ride the rides. But if anyone wants permission

to operate such equipment at Carver Park, I'm certain that

the City Commission would be glad to give them permission.

Q Let me ask you this, these rides in Tift Park,

is this an operation by private person?

A By a private person, yes.

Q What's the name of the private person out there?

A I do not recall. It's under a contractual

arrangement. As a matter of fact, I just signed the

contract about two weeks, two or three weeks ago, but I

just simply do not recall the name of the lessee.

Under the terms of this agreement he is to

operate the rides and carry liability insurance and charge

so much for the rides, and the City charges him, I think,

an amount which is just about equivalent to the use of the

electricity that he would use in the operation, some nominal

amount, the idea of the City being to encourage operators

to supply and provide these facilities. Of course, the City

has no funds with which to purchase this equipment and .

operate it itself.

0, Is there anything in that contractual arrangement

which requires the lessee to permit all citizens, that is

colored and white, Negro and white, of the city of Albany

to use that facility?

MR. RAWLS: If Your Honor pleases, we submit

that the contract itself would be the highest and best

35B

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730,731

evidence and we object to that question as the contract

is made a matter of written record in the City Clerk’s

office.

THE COURT: Is it readily available?

MR. RAWLS: Yes sir, it's readily available.

THE COURT: Well, I think the objection is

good on the basis as stated, the contract would be the

highest and best evidence; if it's readily available,

let’s get it.

MRS. MOTLEY: All right, we’ll get the contract,

Your Honor.

Q Let me ask you this, have you discussed with the

lessee of the trains the policy with respect to the use of

those trains by Negro and white citizens in the light of all

of the activities by the Albany Movement?

A I don’t recall ever having any discussion with

the lessee, except when I take my children out to the park.

Q What about the swimming pool, is that operated

by a private lessee?

A No.

Q. In Tift Park?

A The tickets are sold by a lessee, it is my

understanding, but the pool Itself Is operated by the City.

Q Now, has there ever been any discussion at the

meetings of the Board of City Commissioners regarding the

use of that pool in Tift Park by Negroes?

MR, RAWLS: Now, if your Honor pleases,

that’s a rather sweeping question. I imagine it would

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730,731

36B

be difficult for the Mayor to remember every discussion

that’s been had by the members of the City Commission;

and it is true also, and this is the ground of my

objection, that whatever discussion might have been

had would not be the policy of the City, but whatever

resolution is passed and put on the minutes of the

Board would establish the policy. In other words,

there are three commissioners or two commissioners

and the Mayor who could talk all day about something.

That would be possible and yet that would not establish

the policy for the City. The proper way to establish

what the fixed policy of the City is, which can't do

anything at all, as Your Honor knows, being a corpora

tion except by formal action, either by resolution or

ordinance,* and, of course, the minutes of the City

Commission are open, public records, and certified

extracts or certification of those records would be

the highest evidence of whatever the policy was.

THE COURT: The question was, has there ever

been any discussion; and I think that that question can

be answered without going into what the discussion was.

The question so far is only as to whether there has

ever been any discussion.

Now, I agree with counsel that only what has

been decided by resolution or formal action of one kind

or another, only that would be evidence of what the

City's position is. But the question so far is, has

there here been any discussion, and I think that

37B

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction* Nos.730,731

question can be answered. I overrule the objection.

A The Witness: Yes, there has been some discussion.

Q Mrs. Motley: All right, when did this discussion

take place?

A I don't recall.

Q Has it been within the last three months?

A I'm sure that there has been some discussion

relative to the matter within the last three months.

MR. RAWLS: Now if Your Honor pleases, we

object to this as being illegal, irrelevant and imma

terial, because whatever discussion, as I pointed out

In my previous objection, might have been had would not

have any binding effect until confirmation was had by

a formal passing of a resolution or an ordinance

formulating It. So, the time when or where any dis

cussion was had would be illegal, irrelevant and

Immaterial.

THE COURT: Well, it's possibly technicalljr

so but I overrule the objection, because the question

is simply, first, has there been any discussion; and,

second, when has the discussion taken place. You see,

she Is not attempting to go into what the discussion

was. Of course, only formal action would be admissi

ble as far as establishing the policy. But she's simply

asking him, has it been discussed and If so when.

I'll allow the question. I overrule the objection.

MRS. MOTLEY: I believe the question was

answered?

THE COURT: I think it was.

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730,731

38B

Q Mrs. Motley: As a result of that discussion,

did the Board of City Commissioners take any action?

MR. RAWLS: Now if Your Honor pleases,

objection is good to that question, on the ground that

if they did take any action, it would be available by

certified copy of the minutes of the City Commission.

THE COURT: She's asking him did they

take any official action. I don't believe she used

the 'word "official".

MRS, MOTLEY: Well, that’s what I meant, I ’m

sorry.

THE COURT: Yes. You’re asking him, did

the City take any official action as a result of this

discussion?

MRS. MOTLEY: Yes.

MR. RANTS: Now, if Your Honor pleases,

there would be strictly higher and better evidence

because that would of necessity have to be by resolution

or ordinance.

THE COURT: I agree when we reach that point

but we haven’t reached that point. The question now

is, did the City take any official action, and that’s

a proper questionj and I overrule the objection.

The question is, did the City take any official action?

A The Witness: Yes sir, I understand the question,

Your Honor. I was just trying to recall. There has been so

much going on In the past nine months as a result of all of

this activity I just simply can’t recall. But I can say this

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730,731

39B

that I do know - now, whether this was done by resolution

or by - I know it was not by ordinance - but whether any

resolution was adopted, I don't know; but it was the feeling

of the Commission —

MR. RAWLS: Now, I object to that, if Your

Honor pleases.

The Witness: All right.

MR. RAWLS: The Mayor can't legally state

what the feeling of the Commission was,

THE COURT: Yes, I think we ought to limit

ourselves and I have already indicated what my view

about that is; and Mrs. Motley has not asked him to

relate anything of an official nature as yet; if she

does, I think a copy of the ordinance or the resolu

tion itself would be the best evidence of it. So, if

any official action was taken, I believe you stated

that you can't recall?

A The Witness: I do not recall.

THE COURT: Well, he can't recall whether any

official action was taken or not.

Q Mrs. Motley: All right, If any official action

was taken, it would be reflected in the minutes of the Board

of City Commissioners, would it not?

A It would.

Q Now, you have another park In the City of Albany,

I believe you stated, Tallulah-Massey Park?

A Yes.

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730,731

40B

Q, Is that for Negroes or whites?

A There is no ordinance or resolution of the

Commission specifying whether It's for Negroes or whites.

Because of geographical location and because of custom and

tradition, it's been used predominantly by white.

Q, Do you know when that park was opened?

A Again, I don’t recall the date. It’s been there

for several years.

Q Do you know what facilities they have there?

A Swimming pool, picnic table - tables, and the

usual playground equipment. It’s about in the same category

as Carver Park, with the exception of the Teen Center. We

do not have a teen center at Tallulah Massey.

Q Did you say you have a swimming pool there?

A Yes, there’s a swimming pool there.

Q, Now, I believe you said by "custom and tradition"

this park has been used by whites, is that right?

A Predominantly, yes.

Q, When you say "predominantly", what do you mean?

A I mean that some Negroes may use the park, I don’t

know. I don’t know whether they do or they don’t. I do

know that there is no resolution or ordinance requiring or

prohibiting Negroes from going to Tallulah-Massey Park.

Q Now, let me ask you this: in the light of that

tradition and custom, did the Board of City Commissioners

ever discuss that custom and tradition with relation to the

petition which you identified a while ago as Plaintiffs’

Exhibit No. 1 ?

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730,731

4 IB

A The City Commission has discussed the request

relative to parks, which, of course, Includes recreational

facilities; yes, they've discussed it.

Q, And was any action taken by the Board of City

Commissioners following that discussion?

MR, RAWLS: Now, if Your Honor pleases,

I object to that because if there had been any binding

action taken, it would have to be in writing; as a

matter of law, any binding action - she asked him If

any action was taken- as a matter of law, this is a

corporation and can only act in regular or called

session with a quorum of the Board present and can

act only by resolution or ordinance in writing, which

would have to be entered on the minutes of the Board.

So now, in answer to the question she submitted, it

could only come from the minutes of the Commission.

THE COURT; Well, she’s simply asking him,

was any official action taken. That’s all she’s asking

him at this point, and I overrule the objection.

A The Witness: I do not recall any resolution

being passed relative to the parks. There may have been.

I don’t recall it though.

Q Mrs. Motley: All right, but if there was

action taken by the City Commissioners following a dis

cussion regarding the parks and Plaintiffs’ Exhibit #1,

which is a demand by the Albany Movement for desegregation

of those parks, it would be reflected in the minutes of the

Board of City Commissioners, would It not?

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730,731

42B

MR. RAWLS: Now, if Your Honor pleases,

she's asking the Mayor a legal question. That’s a

matter of law, official action by the Board of City

Commissioners, and it would have to be a matter of law.

THE COURT: She's asking him If they did

take any official action, would it be reflected in

the minutes of the City Commission.

MR. RAWLS: And the answer to that question

Is foreclosed by the law. It's a matter of law, that

any official action by the Board of City Commissioners

would of necessity have to reflect Itself in the official

minutes of that Board.

THE COURT: She's entitled to know whether

they did what the law requires. She’s entitled to an

answer to that question. I overrule the objection.

A The Witness: Yes.

Q Mrs. Motley: Now, the playgrounds which you'

referred to a while ago, do you know how many there are In

number, approximately?

A I do not. I can get the information. There are

a great number throughout the City though, very small

parks, used by neighborhood children largely.

Q Do these neighborhood parks have any facilities

on them, such as swings or benches?

A Most of them do, yes.

Q Now, does the City Commission furnish any

equipment or uniforms for the use of the children in any

of the three major parks or these smaller playgrounds?

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730,731

43B

A To a limited extent, yes.

Q What equipment or uniforms do you furnish?

A Again, I can't answer specifically, I Just

don't know. I know that I ’ve signed checks for some

football uniforms, some football helmets, and maybe some

baseball equipment. I Just don't know. I do know that

we furnish some, yes.

Q Who would know about that?

A Mr. Roos may have the figures available. If not,

then Mr. Rod Blalock, who is in charge of Recreation and

Parks.

Q Now, going back to the playgrounds which we

discussed a moment ago, are there any of those playgrounds,

other than Carver Park, located in Negro communities?

A I'm sure there are some; I don't know where they are.

0. Who would know about that?

A Mr. Blalock can give you the exact location of all

of them.

Q I would like to direct your attention again to

Plaintiffs' Exhibit #1, which Is the petition of the Albany

Movement, and you will note that they ask for desegregation

of the library, is that right?

A Yes.

Q And you say the libraries In the City of Albany

are under whose Jurisdiction?

A A board of trustees and the board Is appointed

by the City Commission.

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730,731

44b

Q How many libraries do you have in the City of

Albany?

A Under the jurisdiction of the trustees of the

library board?

Q Yes sir?

A There are two, one which was just recently

completed at a cost in excess of $25,000, which was con

structed primarily for the use of the Negro community and

located in the area which would make it more accessible to

the Negro community.

Q, What's the name of that library?

A I do not know. It was just opened by formal

dedication this year.

Q What's the other library that you have in the

City of Albany?

A The Carnegie Library.

Q And that's under the jurisdiction of this board?

A Yes.

Q And that’s limited to whites, isn’t It?

A There Is no ordinance or resolution relative

to the use of the library by Negroes or whites.

Q All right, what about policy and custom? You

know that only whites have been permitted to use that

library, don’t you, as a matter of policy and custom?

A As a matter of custom and tradition, that's

true.

Q Now, has the Board of City Commissioners ever

discussed this custom In the light of the petition of the

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730,731

45B

Albany Movement, Plaintiff’s Exhibit #1, that the library

facilities be desegregated?

A Yes, It’s been discussed,

Q Did the Board of City Commissioners take any

action following that discussion?

A The Chief of Police requested that the library —

MR. RAWLS; Now, Your Honor pleases, that

answer is not responsive and I object to it. She

asked him the question whether or not the Board of

City Commissioners had taken any action following that

discussion.

THE COURT; The question Is, did the Board

of City Commissioners take any official action in

consequence of such discussion?

A The Witness: The City of Albany or the City

Commission at a meeting discussed the problem, and It was

decided —

MR. RAWLS: Now if Your Honor pleases, I

object to what the City Commission decided because,

as has been pointed out many times, the official

minutes would be the proper way to prove that.

THE COURT; The question is, did the City

Commission take any official action? That's the

question. Did they or didn't they take any official

action?

A The Witness: I simply do not recall whether

there was any official action insofar as the City Commission

is concerned because I just do not know, insofar as a

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730,731

46b

resolution or ordinance is concerned.

Q Mrs. Motley; In other words, you're saying that

they may have discussed it but nothing may appear In the

minutes, is that It?

A I'm sure that it was discussed, yes.

MR, RAWLS: That's exactly why the law

requires a finding of the City Commission and it would

have to be a public record. That question illustrates

that point. What the Mayor may remember or the Mayor

Pro-Tem or some other member of the City Commission

may remember would be too fallible, which would be a

matter of proof, I mean verbal proof; whereas, the

law requires that official action of the City govern

ment be as a matter of law in writing and not what

somebody remembers about it,

THE COURT; Yes, the witness, as I understand

his testimony, is saying that they did discuss It

but he cannot recall whether any formal action was

taken —

The Witness: That's true.

THE COURT; — in the manner that the Com

mission acts, which is by ordinance or resolution.

The Witness: That's true.

THE COURT; He cannot remember whether they

did or not. If they did, would the minutes of the

Commissioners reflect it, If they did take any action,

would they, any official action?

The Witness: Yes sir.

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730,731

47B

Q Mrs. Motley: Mayor Kelley, have you read the

complaint in this case?

A Which one?

Q This case involving the public facilities, No. 730?

A Yes, I have read it, not as a lawyer would read

it, but as a lay person would read it.

Q, Do you recall that the complaint seeks to have

this court enjoin the enforcement of certain ordinances of

the City of Albany?

A Yes.

Q Do you recall what those ordinances were?

A I do not.

Q, Do you know whether — I would like to shoxv you

PLAINTIFFS’ EXHIBIT No. 2 for identification, which Is a

certified copy of certain ordinances of the City of Albany

and ask you whether you are familiar with those ordinances?

A Yes, I am generally familiar with these

ordinances, I do not recall whether this ordinance is

in the language of the Code or not. I was familiar with

Chapter 22, I believe, of the Code. I do not recall

ever having seen a copy of Plaintiffs’ Exhibit #2 as such,

unless it has been incorporated in the Code.

Q Now, let me ask you about PLAINTIFFS’ EXHIBIT #3,

which is another ordinance: Are you familiar with that

ordinance?

A I am.

Q Now, with respect to these ordinances, I would

like to ask you whether whether the Board of City Com-

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730,731

48b

missioners ever discussed these ordinances with reference

to the petition of the Albany Movement, Plaintiffs" Exhibit

#1, as relates to buses and bus stations?

THE COURT; Before we go any further with

that, let me see those just a minute.

MRS, MOTLEY; Yes sir (handing up ordinances

P-2 and P~3 to the Court) . . .

THE COURT; All right.

A The Witness; I do not understand your question

insofar as you have related it to Plaintiffs’ Exhibit #1,

would you explain that?

Q Mrs. Motley; Yes, would you look at

Plaintiffs* Exhibit No. 1, a copy of which I understand

you have in your hand -

A Yes.

Q, The first Item among those listed by the Albany

Movement as principal targets of desegregation is bus

stations, is It not, No. 1?

A Yes, that's true.

Q And then, No. 6 is city busses, is that right?

A Yes.

Q Now, Plaintiffs’ Exhibit #2, which you’ve just

read, has to do with passenger busses operated In the City

of Albany, does it not?

A It does.

Q Now, my question is, whether the Board of City

Commissioners has ever discussed this ordinance with relation

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730,731

to this demand by the Albany Movement for desegregation of

City busses?

A Yes.

Q Was any official action taken by the Board of

City Commissioners following that discussion?

A No, if you mean by official action the adoption

of a resolution or an ordinance?

Q. That’s right?

A No.

Q Now, let me direct your attention to Section 2

of Plaintiffs’ Exhibit #2, which has to do with taxicabs

in the City of Albany?

A Yes.

Q Has the City Commission ever discussed that

ordinance?

A The City Commission has discussed the ordinance

relative to the use of taxicabs, yes.

Q Has that been within the last three months?

A Yes.

0, Was any action taken by the City Commissioners

following that discussion?

A No official action.

Q Now, let me direct your attention to Section 3

of Plaintiffs1 Exhibit #2, which has to do with

theaters or places of amusement in the City of Albany,

and ask you whether the City Commission has discussed

that ordinance within the last three months?

A It has been discussed.

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730,731

Q It has?

A Yes.

Q, Now, following that discussion did the Board of

City Commissioners take any official action?

A No.

Q, Now, I will direct the same question to Section

4, which again has to do with separate lines in front of

theatres, I believe, and ask you whether the City Com

mission has discussed Section 4 in the last three months?

A It has.

Q, Has any official action been taken by the City

Commissioners following that discussion?

A No official action has been taken.

Q What about section 5, which has to do with the

penalty Imposed for violation of these ordinances: has that

ever been discussed by the City Commission within the last

three months?

A I have no recollection of any discussion relative

to the penalty.

Q Now, what about Plaintiffs' Exhibit #3, which is

another ordinance having to do with taxicabs and licensed

vehicles? Has the City Commission discussed that ordinance

within the last three months?

A It has been discussed, yes.

Q Has any official action been taken by the City

following that discussion?

A No, there’s been no occasion to cause any action

to be taken insofar as the taxicabs are concerned.

Hearing on Motion For Preliminary Injunction, Nos.730,731

Q, Now, directing your attention again to Plaintiffs '

Exhibit #1, which is the petition of the Albany Movement, I

would like to ask you whether the City Commission has dis-

cussed the train station in the City of Albany, which the

Albany Movement’s petition requests be desegregated?

A It has been discussed but I would like to point

out that the City of Albany has no Jurisdiction over the

train facilities.

Q, Weil, have they discussed the petition's demand

that they be segregated?

A It has been discussed generally in the light of

the Interstate Commerce Commission's ruling in November,

yes.

Q, Was any action taken by the City Commission

following the discussion of the ICC ruling?

A No action was necessary. There's no ordinance on

the books relative to the train station, as I recall it.

Q Well, hasn't it been customary for Negroes and