School District No. 20, Charleston, South Carolina v. Brown Brief of School District Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1963

21 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. School District No. 20, Charleston, South Carolina v. Brown Brief of School District Appellants, 1963. 9f485449-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0fb4adff-c521-4d28-a618-0894f9f25840/school-district-no-20-charleston-south-carolina-v-brown-brief-of-school-district-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

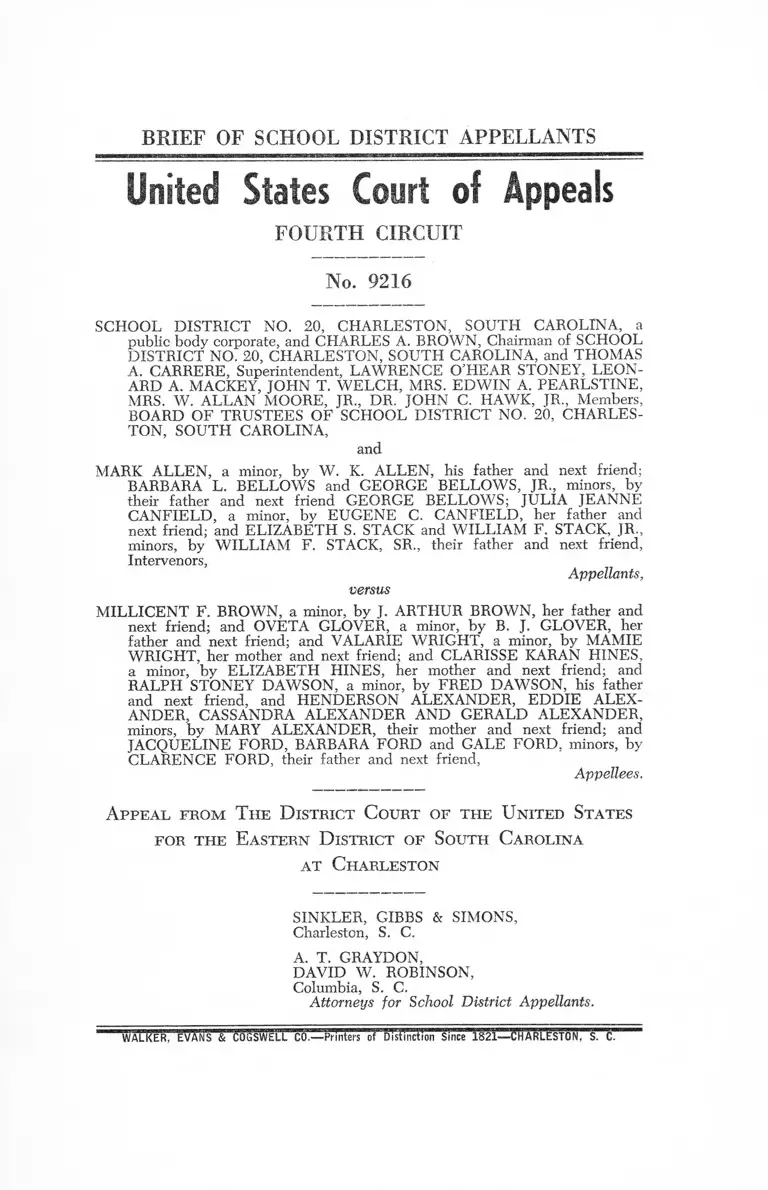

BRIEF OF SCHOOL DISTRICT APPELLANTS

United States Court of Appeals

FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 9216

SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 20, CHARLESTON, SOUTH CAROLINA, a

public body corporate, and CHARLES A. BROWN, Chairman of SCHOOL

DISTRICT NO. 20, CHARLESTON, SOUTH CAROLINA, and THOMAS

A. CARRERE, Superintendent, LAWRENCE O'HEAR STGNEY, LEON

ARD A. MACKEY, JOHN T. WELCH, MRS. EDWIN A. PEARLSTINE,

MRS. W. ALLAN MOORE, JR., DR. JOHN C. HAWK, JR., Members,

BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 20, CHARLES

TON, SOUTH CAROLINA,

and

MARK ALLEN, a minor, by W. K. ALLEN, his father and next friend;

BARBARA L. BELLOWS and GEORGE BELLOWS, JR., minors, by

their father and next friend GEORGE BELLOWS; JULIA JEANNE

CANFIELD, a minor, bv EUGENE C. CANFIELD, her father and

next friend; and ELIZABETH S. STACK and WILLIAM F. STACK, JR.,

minors, by WILLIAM F. STACK, SR., their father and next friend,

Intervenors,

Appellants,

versus

MILLICENT F. BROWN, a minor, by J. ARTHUR BROWN, her father and

next friend; and OVETA GLOVER, a minor, by B, J. GLOVER, her

father and next friend; and VALARIE WRIGHT, a minor, by MAMIE

WRIGHT, her mother and next friend; and CLARISSE KARAN HINES,

a minor, by ELIZABETH HINES, her mother and next friend; and

RALPH STONEY DAWSON, a minor, by FRED DAWSON, his father

and next friend, and HENDERSON ALEXANDER, EDDIE ALEX

ANDER, CASSANDRA ALEXANDER AND GERALD ALEXANDER,

minors, by MARY ALEXANDER, their mother and next friend; and

JACQUELINE FORD, BARBARA FORD and GALE FORD, minors, by

CLARENCE FORD, their father and next friend,

Appellees.

A p p e a l f r o m T h e D is t r ic t C o u r t o f t h e U n it e d St a t e s

f o r t h e E a s t e r n D is t r ic t o f So u t h C a r o l in a

a t C h a r l e s t o n

SINKLER, GIBBS & SIMONS,

Charleston, S. C.

A. T. GRAYDON,

DAVID W. ROBINSON,

Columbia, S. C.

Attorneys for School District Appellants.

W Al T<Er" ' iiEVANS i"& doGSWELL."'CO.— pVmt“ “ ''of' 1 mlslVn,”t!o7i“ lsince'"lS2X—"dFHARLESTON. S. C.

INDEX

P a g e

Statement of the Case_____________________________________ 1

Statement of Questions Involved___ ______________________ 4

Statement of Facts__________________________________ 4

Argument:

Question No. 1_______________________•____ ___________ 7

Question No. 2______________ 9

Question No. 3________________________________________15

Question No. 4__________________________ 16

TABLE OF CASES

P a g e

Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp. 776 (1955) _______________ 17

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294 (1955),

75 S. Ct. 753; 99 L. Ed. 1083 _________ _____________ 14, 16

Brunson v. Board of Trustees of School District No. 1

of Clarendon County, 4 Cir. 311 F. 2d 107, 109

(1962) __________________________________________________11

Burford v. Sun Oil Co., 319 U. S. 315, 63 S. Ct. 1098,

87 L. Ed. 1424 ___________ 11

Carson v. Warlick, 238 F. 2d 724, cert. den. 353 U. S.

910, 77 S. Ct. 665, 1 L. Ed. 2d 664 (1956) _________ 14,16

Jeffers v. Whitley, 309 F. 2d 621 (1962) ______________11,15

McNeese v. Board of Education, 373 U. S. 668, 83

S. Ct. 1433, 10 L. Ed. 2d 622 (June 3, 1963) ______ 11,13

Peterson v. City of Greenville, 373 U. S. 244, 83 S. Ct.

1119, L. Ed. 2 d _________________________________________ 16

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 68 S. Ct. 836, 92 L. Ed.

2d 1161 _________________________________________________16

U. S. v. Cruickshank, 92 U. S. 542 ______ __________________ 16

BRIEF OF SCHOOL DISTRICT APPELLANTS

United States Court of Appeals

FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 9216

SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 20, CHARLESTON, SOUTH CAROLINA, a

public body corporate, and CHARLES A. BROWN, Chairman of SCHOOL

DISTRICT NO. 20, CHARLESTON, SOUTH CAROLINA, and THOMAS

A. CARRERE, Superintendent, LAWRENCE O’HEAR STONEY, LEON

ARD A. MACKEY, JOHN T. WELCH, MRS. EDWIN A. PEARLSTINE,

MRS. W. ALLAN MOORE, JR., DR. JOHN C. HAWK, JR., Members,

BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 20, CHARLES

TON, SOUTH CAROLINA,

and

MARK ALLEN, a minor, by W . K. ALLEN, his father and next friend;

BARBARA L. BELLOWS and GEORGE BELLOWS, JR., minors, by

their father and next friend GEORGE BELLOWS; JULIA JEANNE

CANFIELD, a minor, by EUGENE C. CANFIELD, her father and

next friend; and ELIZABETH S. STACK and WILLIAM F. STACK, ]R „

minors, by WILLIAM F. STACK, SR., their father and next friend,

Intervenors,

Appellants,

versus

MILLICENT F. BROWN, a minor, by J. ARTHUR BROWN, her father and

next friend; and OVETA GLOVER, a minor, by B. J. GLOVER, her

father and next friend; and VALARIE WRIGHT, a minor, by MAMIE

WRIGHT, her mother and next friend; and CLARISSE KARAN HINES,

a minor, by ELIZABETH HINES, her mother and next friend; and

RALPH STONEY DAWSON, a minor, by FRED DAWSON, his father

and next friend, and HENDERSON ALEXANDER, EDDIE ALEX

ANDER, CASSANDRA ALEXANDER AND GERALD ALEXANDER,

minors, by MARY ALEXANDER, their mother and next friend; and

JACQUELINE FORD, BARBARA FORD and GALE FORD, minors, by

CLARENCE FORD, their father and next friend,

Appellees.

A p p e a l f r o m T h e D is t r ic t C o u r t o f t h e U n it e d St a t e s

f o r t h e E a s t e r n D is t r ic t o f So u t h C a r o l in a

a t C h a r l e s t o n

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This is a suit which was commenced by appellees who are

or were minor Negro school pupils enrolled in the Charleston

City Schools. The Complaint by its prayer sought to enjoin

( 1 )

the Charleston District No. 20 School Board from operating

a compulsory bi-racial school system in Charleston County

and asked the Court to direct the presentation of a plan for

desegregation by the School Board. (Ap., pp. 8-9).

The district involved encompasses the City of Charleston

and the defendant School Board has denied that there is

compulsory segregation of the races in the schools of the dis

trict. As to the particular Negro appellees, the School Board

averred that the procedures set out by Statute and the rules

of the School Board have not been followed by several ap

pellees and that four appellees who applied in 1961 had been

denied the right of transfer on non-racial grounds after proper

hearings.

As a further defense the School Board alleged certain ethnic

differences between the white and negro races which make

the education of the two races on a fully integrated basis de

structive of the educational system in the district. The School

Board asserted this position in its Answer ( Ap., pp. 15-19)

and again in its Petition for Amendment and/or Vacation of

the Order of the District Court (Ap., pp. 301-308).

The intervention of certain white pupils was permitted,

and the intervenors filed an Answer setting out the same gen

eral allegations as to ethnic differences between the races and

relied on that defense alone. The testimony in this regard

was presented by the intervenors and the School Board’s posi

tion ( stated in the Motion to Amend the District Court’s

Order) is substantially the same as that of the intervenors

with reference to that issue. No separate brief will be filed

by the School Board on that issue and the Court’s attention

is directed to the brief of intervenors.

Lengthy and exhaustive testimony was taken, principally

2 School D ist. No . 20 & M ark Allen , et a l , A ppellants, v ,

M illicent F. Brow n , et a l , A ppellees 3

on the ethnic issue, in hearings conducted in Columbia on

August 5 and 6, 1983.

The appellees’ case was based on the deposition of Thomas

A. Carrere, Superintendent of the School District involved

( Ap., pp. 34-46); certain interrogatories and answers (Ap., pp.

47-57); and the testimony at the trial of Mr. Carrere (Ap.,

pp. 71-84), and of the chairman of the Board of School Dis

trict No. 20 (Ap., pp. 84-85) and of the Supervisor of negro

schools for the District ( Ap., pp. 85-91).

The portion of the record relating to the administrative

procedures issue is contained in pages 92-100 of the Appendix

and on pages 248-276 of the Appendix. That testimony and

the records will be reviewed under Point 2.

On August 22, 1963, District Judge Martin issued an Order

directing the enrollment of 11 of the appellees “at the white

school, where a white child would normally attend . . . ”

The Order restrained the Board from refusing admission, as

signment or transfer of other negro children on the basis of

color for the year 1964-65, enjoined the Board from “futile,

burdensome or discriminatory administrative procedures” and

set out specific administrative procedures to be followed. The

Order also allowed the Board to file a school desegregation

plan but provided for the Court-ordered plan to remain in

effect until such a plan is presented and approved.

The School Board defendants moved to amend and/or va

cate Judge Martin’s Order, and the grounds for the appeal

by these appellants ( School District No. 20, its Board of Trus

tees and its Superintendent) are set out on pages 297-301 of

the Appendix. An exception relating to the administrative

directions contained in the order is set out in paragraph 14

of Part III of the Petition (Ap., p. 308).

The petition was refused by Judge Martin on September

5, 1963, and the appeal to this Court followed.

STATEMENT OF THE QUESTIONS INVOLVED

1. Was the procedure provided by the South Carolina

Statutes for transfer of pupils, and the rules promulgated

pursuant thereto by the Charleston County Board of Educa

tion, adequate?

2. Were the procedures properly followed by the Board

of Trustees of School District No. 20 and the Charleston

County Board of Education?

3. Even if the procedure under the statutes and rules were

found inadequate or if the same were not properly followed

by school authorities, did the District Judge err in specifying

and promulgating administrative rules for the operation of

the schools?

4. Was there any basis for findings by the District Court

that the schools were operated on a basis of compulsory segre

gation enforced by the School Board?

STATEMENT OF FACTS

No negro child has ever presented himself for initial enroll

ment at the first grade level in a school other than one at

tended by negro children in the City of Charleston (Ap. 51

and 100). Prior to the applications of the plaintiffs in this

suit, the first of which were in the fall of 1960, no negro stu

dents had ever applied for transfer to a school other than

one attended by negro children.

In October of 1960, several negro pupils, including most

of the plaintiffs in this suit, filed applications for transfer to

schools up to that time attended only by white children. The

Trustees of the School Board replied promptly to these ap

4 School D ist. N o . 20 & M ark Allen , et a l , A ppellants, v .

M illicent F. Brow n , et a l , A ppellees 5

plications for transfer, advising that the time for applying

for transfer under the Board’s regulations had passed and that

the requested assignments could not be considered. The rules

and administrative procedures under which these transfer ap

plications were denied (Ap. 248) require filing of such appli

cations four months in advance of the opening of school, and

since the 1980-196.1 school year had already started, these

applications were not timely. The applicants processed their

applications pursuant to the rules and administrative pro

cedures and pursuant to South Carolina law (Ap. 313 et seq.)

by appeal to the County Board of Education from the School

Board’s denial. The School Board filed a return to the appeal

and the County Board of Education held a hearing and af

firmed the School Board’s action. The County Board of Educa

tion held that the four-months rule was a reasonable one and

that there had been no abuse of discretion in its application.

Reproduced in the Appendix, beginning at p. 251 and ending

at the middle of p. 258, are the 1960 proceedings with respect

to three Ford children; similar proceedings were separately

had with respect to all the other 1960 applicants and sub

stantially similar disposition made of their applications.

Nothing further was done following the County Board of

Education’s dismissal of the 1960 petitions for transfer. The

1960 proceedings involved the Alexander, Dawson, Ford,

Glover, Hines, Wright, Toomer and Seabrook children.

In 1961, a different Brown child but the same Dawson,

Glover, Hines, Wright and Seabrook children applied for

transfer, this time early in May and more than four months

prior to the opening of the schools for the 1961-1962 year.

All these children were given a hearing by the defendant School

Board. Prior to the hearing, the Board conducted a thorough

investigation into each child’s record, background and per

sonality, considering all available pupil records and interview-

mg the school Principal in each case, as well as their teachers

wherever possible. On the basis of such investigation and

hearing the Board concluded as to each applicant that it was

to his or her best interests educationally to remain in the

school from which transfer was being sought.

The negro children appealed the Board’s determination to

the County Board of Education and upon a hearing de novo

that body concluded that the School Board’s action was predi

cated upon the welfare and interests of the child for whom

transfer was sought and that the propriety of the School Board’s

denial of such transfer was abundantly supported by the rec

ord.

Reproduced in the Appendix, beginning at p. 258 and end

ing on p. 273, are the 1961 proceedings with respect to the

Wright child; similar proceedings were separately had with

respect to the Brown, Dawson, Hines and Seabrook children

and substantially similar disposition was made of their appli

cations. The Glover child did not appeal to the County Board

of Education from the defendant School Board’s denial of her

transfer application.

The plaintiffs in this suit accordingly comprise: (1 ) Milli-

cent Brown, Valarie Wright, Clarisse Hines and Ralph Stoney

Dawson, all of whom completed the South Carolina statutory

administrative procedures under the defendant School Board’s

rules and administrative procedure; (2 ) the Alexander and

Ford children, who did not participate in the 1961 transfer

applications following denial of their 1960 applications on the

ground of the four-months rule; and (3 ) Oveta Glover, who

only partially completed the South Carolina statutory adminis

trative procedures.

The Toomer and Seabrook children did not join in the

suit and subsequent to the filing of the suit the plaintiff Valarie

6 School D ist. N o . 20 & M ark Allen , et a l , A ppellants, v .

M illicent F. Brow n , et a l , A ppellees 7

Wright and one of the five Alexander children, Henderson

Alexander, ceased to attend the Charleston schools.

A factual summary of the administrative procedure in this

case is contained in the discussion of Question 2 below.

ARGUMENT

1. The Statutory procedure and rules promulgated by

School District No. 20 were adequate.

Whether the statutes and rules were adequate is not to be

determined by the results obtained under those rules but by

the statutory enactments and rules themselves. Improper ad

ministration of the procedure would not invalidate the rules

if they are adequate when properly administered.

If the hearings held pursuant to the rules had resulted in

the admission of one or more negroes to Charleston’s white

schools, then there would be no complaint by appellees about

the procedure. But that was not the case, and the District

Judge has held the rules and regulations inadequate because

“they fail to establish a right of choice, to a child or his

parents, at the time of enrollment and the announcement of

such right of choice made known to the parents of pre

school children.” (Ap., p. 291).

But the District Judge found that “No formal application

has been made by any negro child to enter a white school at

the first grade level.” All of the appellees had petitioned for

transfer to a white school.

What the District Judge has done is to find that the rules

and regulations are inadequate because the School Board failed

to grant the requests of appellees for transfer.

The Statute (Section 21-230 ( 9 ) ) provides that school trus

tees shall “Transfer any pupil from one school to another so

8 School D ist. No . 20 & Mark Allen , et a l , A ppellants, v .

as to promote the best interests of education, and determine

the school within its district in which any pupil shall enroll.”

(Ap„ p. 313).

Sections 21-247—21.247.6 provide a remedy for a parent who

does not agree with the action of the Board of Trustees of

the School District upon an application for transfer. (Ap., pp.

314-315) That procedure, in summary, is as follows:

(a ) An appeal to the County Board of Education by peti

tion;

(b ) Separate hearings de novo by the County Board of

Education;

(c ) An appeal to the Court of Common Pleas upon the

record below from any order of the County Board

of Education;

(d ) An appeal to the Supreme Court of the State.

The rules and administrative procedures adopted by the

School Trustees provided for: (Ap., pp. 248-250)

(a ) Written applications for a request for transfer to be

filed four months before the opening of the schools concerned;

(b ) Reasons for the transfer set out in the application;

(c ) Standards for the Board to follow in passing on such

applications including “scholarship attained, age, culture, daily

companions and associates, intelligence, whether the educa

tion of applicant and his standing in class better fits him to

the school in which he has been enrolled or the one men

tioned in the application, and such further facts and standards

as may be in the public interest for the promotion of educa

tion and to protect the health, morals, and general welfare

of the community.”

M illicent F. Brow n , et a l , A ppellees 9

(d ) Written notice of the Board’s public hearing;

(e ) A public hearing;

( f ) Right of appeal to the County Board of Education

and the Courts.

No mention of race is made in the statutes or the rules. If

pupils are to be given the unquestioned right to transfer upon

application, the orderly administration of the schools would

end.

The District Judge has not specified wherein the statutes

and rules are inadequate, and we assert that the procedure

is entirely reasonable and adequate. The lack of positive

provisions promoting “free choice” in no wise shows that the

rules are inadequate.

The statute and rules were there for the use of any parent;

clearly they are not inadequate as a matter of law.

2. The procedures were properly followed by the School

Board in this case.

The exact procedures set out by the statutes and rules and

regulations of the School Board were followed in this case.

The 1960 application for transfers to white schools, all of

which were filed in October on behalf of 12 of the appellees,

were all rejected because the 1960-1961 term was underway;

the rule provided for the submission of applications four

months before the opening of school. Eight of these ap

plicants took no further administrative steps although the Dis

trict Judge found that their applications would have been

denied had they pursued the administrative relief.

The primary purpose of a school system is education, and

in order for there to be any reasonable chance of conveying

an education to the pupils, a system is necessary—even im

perative. Overcrowded conditions and disruption of orderly

educational processes is destruction of education itself.

There was no contention on the trial (and there can be

no good faith contention) that the Board acted improperly in

rejecting the applications for transfer in the middle of the

school year. The District Judge recognized the danger and

impracticability of wholesale transfers in 1963-1964. The Dis

trict Judge recognized by his Order the impropriety of in

term transfers.

These denials were therefore entirely proper.

W e come, therefore, to the applications for transfer which

were filed in May, 1961. The four applications with which

this appeal is concerned were filed as required and the fol

lowing is the chronology of the handling of these applications.

1. May 1st: Applications for transfer filed.

2. May 5th: Receipt of application acknowledged by

School Board.

3. July 12th: Hearing set before School Board for July

19th.

4. July 19th: Hearing held.

5. July 29th: Denial of transfers recommended by Spe

cial Committee of the School Board as not

being in “best interests” of children in de

tailed report on each child. ( Ap. pp 260-

267).

6. July 31st: Petition for transfer denied by School Board.

7. August 10th: Petitions filed with County Board of

Education.

10 School D ist . No . 20 & M ark Allen , et a l , A ppellants, v .

M illicent F. Brow n , et a l , A ppellees 11

8. August 29th: Return filed by School Board asking

that petition to County Board be dis

missed.

9. January 18th, 1962: Appeals dismissed by the County

Board of Education after hear

ing de novo.

The various applications have been handled in exact ac

cordance with the statutory directives and procedures and

there is nothing in the pleadings or in any of the record which

indicates that race was the factor, or even a factor, which

motivated the denials of these transfers.

The various applications were handled on an individual

basis, for the rights are individual, and nothing in this record

would indicate a better or preferable method of treatment.

In Brunson v. Board of Trustees of School District No. 1

of Clarendon County, 4 Cir. 311 F. 2d 107, 109 (1962) the

Court said:

“As we stated in Jeffers [v. Whitley, 4 Cir. 309 F. 2d 621

(1962)], we have held that rights under the Fourteenth

Amendment are individual and are to be individually asserted

only after individual exhauston of any reasonable state reme

dies which may be available ®

The “state remedies” referred to in Brunson are, of course,

administrative and procedural, Burford v. Sun Oil Co. 319 U. S.

315, 63 S. Ct. 1098, 87 L. Ed. 1424, and not rights given by

state law in state litigation, McNeese v. Board of Education,

373 U. S. 668, 83 S. Ct. 1433, 10 L. Ed. 2d 622 ( June 3, 1963).

The facts in the instant case distinguish it from Jeffers v.

Whitley, 4 Cir. 309 F. 2d 621 (1962).

Here the administrative remedies, as administered, cannot

be called “ unnegotiable obstacle courses;” there has been no

“invariable denial of interracial transfer requests;” they cannot

be said to accord only “freedom of choice at the first grade

level, without any right of choice thereafter;” and in the ad

ministrative hearings held by the Board of Trustees and the

County Board of Education there has been no “general disre

gard by the School Board of the constitutional rights of negro

pupils who do not wish to attend schools populated exclusively

by members of their race.”

Charleston children attend schools with other children of

their own race in the absence of applications to attend specific

schools. It is clear that the Board was warranted in conclud

ing that such voluntary attendance did not conflict with their

constitutional rights. A voluntary separation of the races in

schools “is uncondemned by any provision of the Constitution,”

Jeffers v. Whitley, supra, at p. 627 of 309 F. 2d, and failure

to apply to attend a specific school reasonably indicates satis

faction with the Board’s school “assignment” practice.

The court recognized in Jeffers v. Whitley, supra, at p. 628

of 309 F. 2d, that administrative remedies “have a place in a

voluntary system of racial separation,” and that in such a

system “a school official might still deny a particular request

upon grounds thought not to undermine the voluntary nature

of the system.” “In that event,” the court said, “it would be

appropriate for the state to provide the applicant effective

means of administrative review, and failure to pursue an ade

quate administrative remedy might foreclose judicial interven

tion.”

Although the court found in Jeffers that the School Board

had been “obstinate in refusing to recognize the constitutional

rights of Negro applicants,” it held that the plaintiffs were

not entitled to an order “requiring the School Board to effect

a general intermixture of the races in the schools.”

12 School D ist. No . 20 & M ark A llen , et a l , Appellants, v .

M illicent F. Brow n , et a l , A ppellees 13

The applications here involved were handled by the Board

of Trustees and by the County Board of Education on the

basis of the educational best interests of the respective ap

plicants, as found by the Boards from the showing made, and

not on the basis of their race. They were all transfer applica

tions, and no circumstances appeared which negatived the

usual conclusion that it is educationally in the best interest

of a school child to continue in the class of which he or she

has become a part.

It is respectfully submitted that the evidence does not show

compulsive segregation, like that found in Jeffers; on the con

trary, there is here a total absence of evidence of “official

coercion or compulsion.”

Hence, the question presented to the Court is whether the

rejections of the transfer applications by the Board were sus

tained by, or were unwarranted under,, the evidence adduced

before it, and not whether they were assigned to schools in

violation of their constitutional rights. In other words, the

case made before the Court is not a Fourteenth Amendment

case at all, but presents only the issue whether the transfer

applications of those who petitioned the County Board of

Education to review the action of Board of Trustees were

properly handled.

McNeese v. Board of Trustees, etc., supra does not support

a contention that school children and their parents may ignore

the rules of the Board of Trustees relating to school assign

ments.

What McNeese held, and all that it held, was that a Federal

Court should not fail to act upon a claim arising under the

Fourteenth Amendment because state law also afforded a

right to relief maintainable in state court litigation; the Court

added that the administrative remedy relied on was not suf

14 School D ist. No . 20 & M ark A llen , et a l , A ppellants, v .

ficiently adequate to warrant the Court to follow the self-

restraint principle, since the petitioners there did not have an

absolute right to invoke the administrative procedure provided

by state law.

What the late lamented judge John J. Parker said in Carson v.

Warlick, 238 F. 2d 724, cert. den. 353 U. S. 910, 77 S. Ct.

665, 1 L. Ed. 2d 664 (1956) puts this case in the proper

perspective:

“Somebody must enroll the pupils in the schools. They

cannot enroll themselves; and we can think of no one

better qualified to undertake the task than the officials

of the schools and the school boards having; the schools

in charge. It is to be presumed that these will obey the

law, observe the standards prescribed by the legislature,

and avoid the discrimination on account of race which

the Constitution forbids. Not until they have been ap

plied to and have failed to give relief should the courts

be asked to interfere in school administration. As said by

the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education, 349

U. S. 294, 299, 75 S. Ct. 753, 656, 99 L. Ed. 1083:

‘School authorities have the primary responsibility

for elucidating, assessing and solving these problems.

Courts will have to consider whether the action

of school authorities constitutes good faith imple

mentation of the governing constitutional priciples.’ ”

In the instant case all the plaintiffs are concerned with trans

fer applications and no initial assignments are involved, but

in any situation, whether transfer or assignment, obviously

some administrative action by school officials must necessarily

be involved, otherwise chaos would result in the school system

from whimsical and uncontrolled assignments and transfers.

M illicent F. Brow n , et a l , A ppellees 15

The factual investigation required for determination in this

case is whether or not the school officials have been refusing

the transfer of pupils on the basis of race. Such an investiga

tion was made in Jeffers v. Whitley, supra, in which this Court

held that the North Carolina Pupil Placement Act, previously

approved by it, was in that particular instance being uncon

stitutionally administered so as to result in discrimination and

inadequate remedy. It appeared in that case that the schools

of Caswell County, North Carolina, had been compulsively

administered so as to result in segregation, and that the ad

ministrative process had been used consistently and solely to

prevent freedom of choice. Certainly no such proof is present

in this case, where the plaintiffs have proved no more than a

voluntarily segregated school system and where they have

not sought to establish in any particular whatsoever, an in

adequate or discriminatory handling of the administrative pro

cess.

The defendant School Board’s proof establishes a prompt

and full hearing and an impartial and thorough investigation

of the transfer applications, with no intimation of any racial

overtones in any way affecting the final administrative determ

ination.

3. Even if the procedure and rules were deemed inade

quate, the District Judge erred in specifying and promulgat

ing rules for the operation of the schools.

While it is the position of the School Board, as set out

above, that the procedures and rules were adequate ( Ques

tion 1) and were properly administered (Question 2 ), the

inadequacy of the statutes and rules or the improper ad

ministration of adequate statutes and rules is no basis for the

District Court to take over the administration of the Charles

ton County School System.

In the sixth paragraph of that Court’s Order (Ap. p. 294-

295) the District Judge set out and decreed the specific ad

ministrative procedure and even went so far as to prescribe

the notice to be given, the time for such notices to be mailed

to parents of pupils. The Court even provided that variances

from the methods prescribed must be done only with that

Court’s approval.

The United States Courts are the proper forum for the

supervision of desegregation of schools which are within its area,

and the propriety of using the United States District Courts

for that purpose has been recognized by the Supreme Court

in the Brown decision and subsequent cases involving de-

segration of public schools.

But this does not mean that the courts are to take over the

school system and prescribe administrative procedures. For

this is a function of school boards, and as Judge Parker said

in Carson v. Warlick, supra'.

“We can think of no one better qualified to undertake the

task than officials of the schools and the school boards hav

ing the schools in charge.”

4. Was there any basis for findings by the District Court

that the schools were operated on a basis of compulsory

segregation enforced by the School Board?

The Fourteenth Amendment applies only to state action.

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3; U. S. v. Cruickshank, 92 U. S.

542; Peterson v. City of Greenville, 373 U. S. 244, 83 S. Ct. 119,

L, Ed. 2d; Shelley v. Kraemer, 344 U. S. 1, 68 S. Ct. 836, 92

L. Ed. 1161.

Therefore, even though racial segregation existed, the record

must show that it was compulsorily maintained and enforced

by the Board. See Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S.

16 School D ist . N o . 20 & M ark Allen , et a l , A ppellants, v .

M illicent F. Brow n , et a l , A ppellees 17

294 (1955); 75 S, Ct. 753, 99 L. Ed. 1083; Briggs v. Elliott,

132 F. Supp. 776 (1955).

There is no evidence in the record of racial discrimination

by the Board. The 1960 transfer requests of the plaintiffs

were refused on grounds relating solely to the timeliness of

the requests and the adverse effect of a mid-year transfer on

the pupils. There is no evidence that race was a factor. Of

the four 1961 transfer applicants who exhausted the adminis

trative procedures, two would have continued in the same

negro schools if all pupils in the district had then been re

assigned to schools on a purely geographical basis and a third

graduated in 1962. There is no evidence that race was a

factor in the refusal to reassign the fourth, or that the Board’s

decision was unreasonable.

There is absolutely no evidence to support the findings of

the District Court that the transfer requests of these plaintiffs

who failed to exhaust their administrative procedures would

have been denied ultimately.

In each case the plaintiffs were given prompt and impartial

hearings and determinations were based upon their individual

educational best interests.

No initial assignments were made by the Board to segre

gated schools. Each parent picked a school for his child on

the first day of his first school year. The school to be attend

ed was not in any way controlled by the Board or by official

pre-school clinics or enrollment procedures.

No Negro parents ever sought to enter their pupils in white

schools before the transfer attempts of these plaintiffs.

The Board’s rules and the placement law had been uni

formly applied by the Board. Plaintiffs’ transfer requests were

the first received by the Board after the new rules were

18 School D ist. N o . 20 & M ark A llen , et a l , A ppellants, v .

adopted in 1959. There is no evidence that transfer requests

from white pupils would have been handled differently.

On the basis of the foregoing, we respectfully submit that

the administrative procedures followed by the appellant School

Board were entirely adequate and reasonably implemented

by the School Board without racial motivation, and that there

is no basis in the record for the District Court’s finding that

the Charleston schools have been operated on the basis of

compulsory segregation, and lastly, that the District Court

had no authority to specify and promulgate rules for the op

eration of the Charleston schools, and that the Order Below

should accordingly be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

SINKLER, GIBBS & SIMONS

DAVID W. ROBINSON

A. T. GRAYDON

Attorneys for Appellant School Board.