Legal Research on May 4th Session 1

Unannotated Secondary Research

May 4, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Legal Research on May 4th Session 1, 1982. 8e593e2c-e192-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1044d0c2-68ed-4456-a34b-f6dcfaf54f7d/legal-research-on-may-4th-session-1. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

S/AJW

57m Seam, ,4]: ’C/

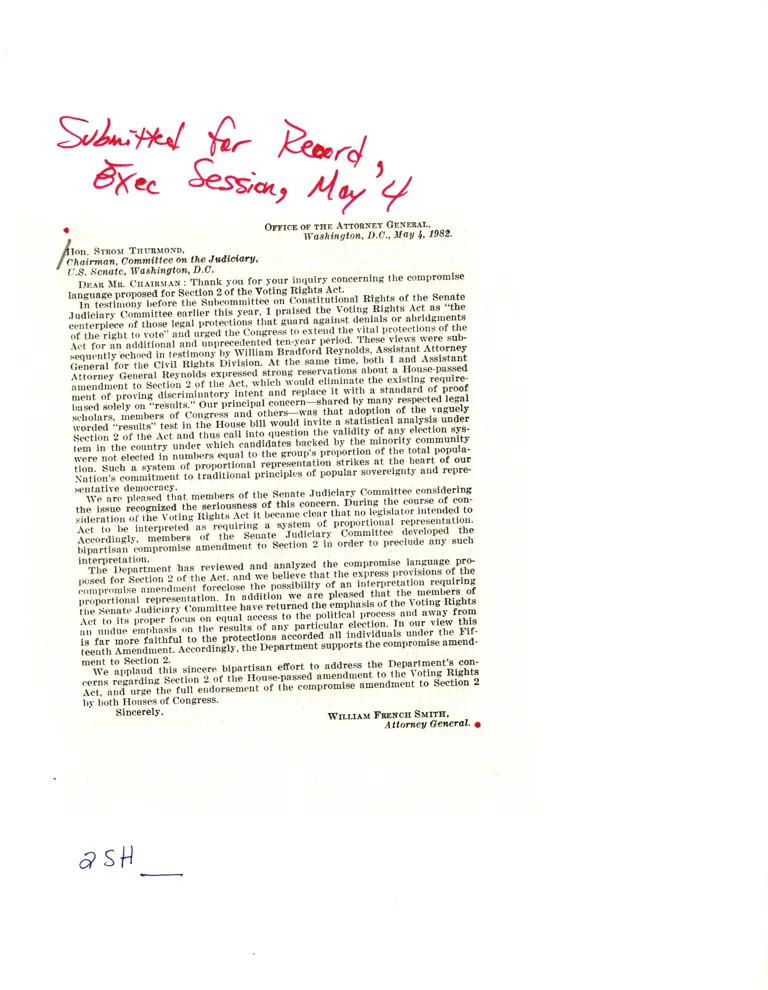

OFFICE or THE ArroaNEY GENERAL,

Washington, D.C., May 4, 1982.

ion. STROM THUBMOND,

Chairman, Committee on the Judiciary,

US. Senate, Washington, D.C'.

DEAR MR. CHAIRMAN: Thank you for your inquiry concerning the compromise

language proposed for Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.

In testimony before the Subcommittee on Constitutional Rights of the Senate

Judiciary Committee earlier this year, I praised the Voting Rights Act as “the

centerpiece of those legal protections that guard against denials or abridgments

of the right to vote” and urged the Congress to extend the vital protections of the

Act for an additional and unprecedented ten-year period. These views were sub-

sequently echoed in testimony by William Bradford Reynolds, Assistant Attorney

General for the Civil Rights Division. At the same time, both I and Assistant

Attorney General Reynolds expressed strong reservations about a House-passed

amendment to Section 2 of the Act, which would eliminate the existing require-

ment of proving discriminatory intent and replace it with a standard of proof

based solely on “results.” Our principal concern—shared by many respected legal

scholars, members of Congress and others—was that adoption of the vaguely

worded “results" test in the House bill would invite a statistical analysis under

Section 2 of the Act and thus call into question the validity of any election sys

tem in the country under which candidates backed by the minority community

were not elected in numbers equal to the group's proportion of the total popula-

tion. Such a system of proportional representation strikes at the heart of our

Nation's commitment to traditional principles of popular sovereignty and repre-

sentative democracy.

“'e are pleased that members of the Senate Judiciary Committee considering

the issue recognized the seriousness of this concern. During the course of con-

sideration of the Voting Rights Act it became clear that no legislator intended to

Act to be interpreted as requiring a system of proportional representation.

Accordingly, members of the Senate Judiciary Committee developed the

bipartisan compromise amendment to Section 2 in order to preclude any such

interpretation.

The Department has reviewed and analyzed the compromise language pro-

posed for Section 2 of the Act. and we believe that the express provisions of the

compromise amendment foreclose the possibiilty of an interpretation requiring

proportional representation. In addition we are pleased that the members of

the Senate Judiciary Committee have returned the emphasis of the Voting Rights

Act to its proper focus on equal access to the political process and away from

an undue emphasis on the results of any particular election. In our view this

is far more faithful to the protections accorded all individuals under the Fif-

teenth Amendment. Accordingly, the Department supports the compromise amend-

ment to Section 2.

We applaud this sincere bipartisan efiort to address the Department's con-

cerns regarding Section 2 of the House-passed amendment to the Voting Rights

Act, and urge the full endorsement of the compromise amendment to Section 2

by both Houses of Congress.

Sincerely,

WILLIAM FRENCH SMITH,

Attorney General. .

asH