Clemons v. Hillsboro, OH Board of Education Brief for Appellants (No. 12,494)

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1955

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Clemons v. Hillsboro, OH Board of Education Brief for Appellants (No. 12,494), 1955. 88bfcdc2-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/10928b10-0bd1-423b-9458-34cd9472e952/clemons-v-hillsboro-oh-board-of-education-brief-for-appellants-no-12-494. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

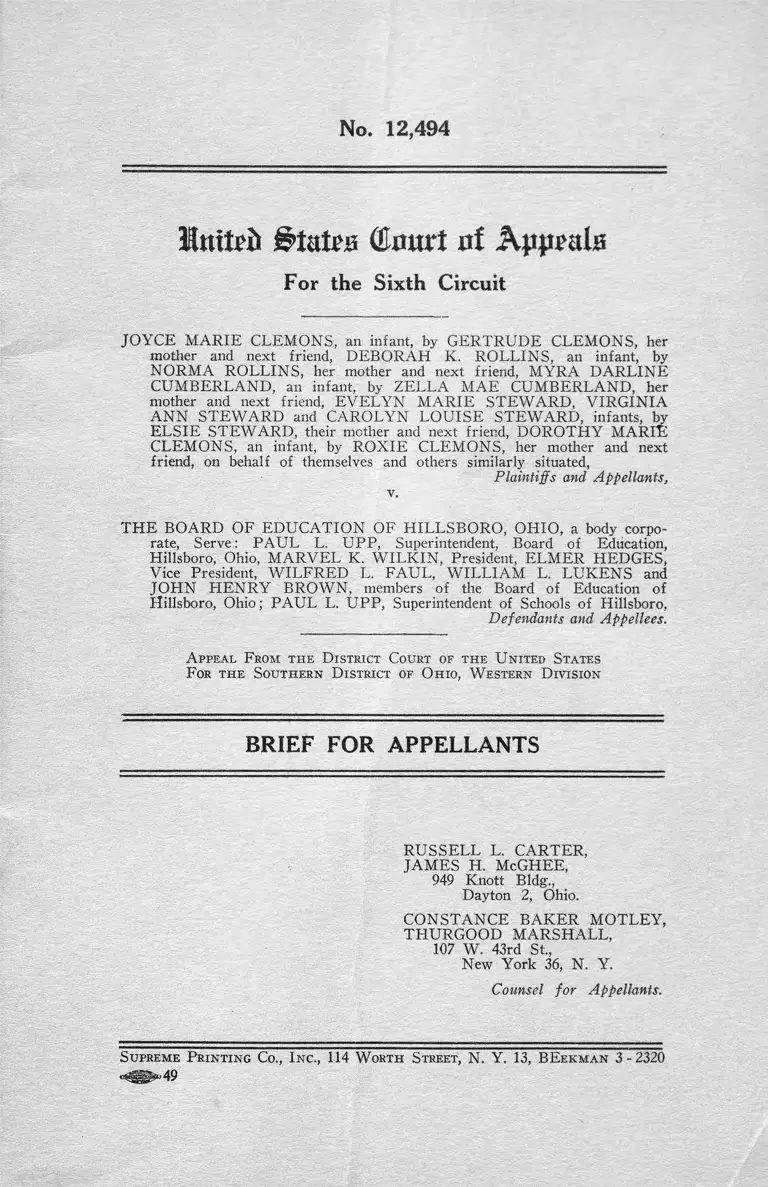

No. 12,494

In itib States (Eiutrt at Appmia

For the Sixth Circuit

JOYCE MARIE CLEMONS, an infant, by GERTRUDE CLEMONS, her

mother and next friend, DEBORAH K. ROLLINS, an infant, by

NORMA ROLLINS, her mother and next friend, MYRA DARLINE

CUMBERLAND, an infant, by ZELLA MAE CUMBERLAND, her

mother and next friend, EVELYN MARIE STEWARD, VIRGINIA

ANN STEWARD and CAROLYN LOUISE STEWARD, infants, by

ELSIE STEWARD, their mother and next friend, DOROTHY MARIE

CLEMONS, an infant, by ROXIE CLEMONS, her mother and next

friend, on behalf of themselves and others similarly situated,

Plaintiffs and Appellants,

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF HILLSBORO, OHIO, a body corpo

rate, Serve: PAUL L. UPP, Superintendent. Board of Education,

Hillsboro, Ohio, MARVEL K. WILKIN, President, ELMER HEDGES,

Vice President, WILFRED L, FAUL, WILLIAM L. LUKENS and

JOHN HENRY BROWN, members of the Board of Education of

Hillsboro, Ohio; PAUL L. UPP, Superintendent of Schools of Hillsboro,

Defendants and Appellees.

A ppeal From the D istrict Court oe the U nited States

For the Southern D istrict of O hio, W estern D ivision

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

RUSSELL L, CARTER,

JAMES H, McGHEE,

949 Knott Bldg.,

Dayton 2, Ohio.

CONSTANCE BAKER MOTLEY,

THURGOOD MARSHALL,

107 W. 43rd St.,

New York 36, N. Y.

Counsel for Appellants.

Supreme Printing Co., Inc., 114 W orth Street, N. Y . 13, BEekman 3-2320

1

Statement of Question Involved

I. Did the court below abuse its discretion in refusing to

grant a permanent injunction enjoining appellees from

enforcing a policy of racial segregation in the elementary

schools and from requiring infant appellants to withdraw

from Washington and Webster Schools and enroll in the

Lincoln School, solely because of their race and color?

Court below refused a permanent injunction for the

reasons set forth in its opinion.

Appellants contend that the answer to the above

question should be in the affirmative.

TABLE OF CONTENTS OF APPENDIX

PAGE

Docket Entries ............................................................... la

Complaint ........................................................ 3a

Motion for Preliminary Injunction . , ..................... 10a

Hearing on Motion for Preliminary Injunction . . . . 12a

TESTIMONY

P l a in t if f s ’ W itn esses

Roald P. Campbell:

D irect.................................................................... 19a

Cross ................................................................ 24a

Marvel K. Wilkins:

Cross ................................................................. 25a

Redirect .............................................................. 30a

Paul Lyman Upp:

Cross .................................................................... 31a

Redirect..................... 44a

Recross ............................................................. 47a

James Dudley Hapner:

D irect........................... 48a

Order Continuing Proceeding on Motion for Pre

liminary Injunction .................................................... 60a

Answer ...................................................... 61a

Order Setting Trial D a te .......................................... . 63a

Stipulation of Facts ........................................................ 65a

I l l

IV

PAGE

Testimony on Trial .......................................................... 70a

P l a in t if f s ’ W itnesses

Marvel K. Wilkins:

Direct .............................................................. 74a

Cross ................................................................ 89a

Redirect .......................................................... 93a

Paul Lyman Upp:

Direct .............................................................. 98a

Cross ............................................... 110a

Redirect............................................................ 111a

(Recalled)

Direct ................................................................. 126a

Helen Ash.:

D irect................................................................ 116a

Roald F. Campbell:

Direct ................................................................. 117a

Cross ................................................................... 120a

D e f e n d a n t s ’ W itn ess

Elmer Hedges:

Direct ...................................... 122a

Decision of Druffel, D. J ................................................ 139a

Final Order ...................................................................... 145a

V

TABLE OF CONTENTS OF BRIEF

PAGE'

Statement of Question In volved ................................. i

Statement of the F a c ts ................................................. 1

Argument:

I. Did the court below abuse its discretion in refus

ing to grant a permanent injunction enjoining

appellees from enforcing a policy of racial seg

regation in the elementary schools and from

requiring infant appellants to withdraw from

Washington and Webster Schools and enroll

in Lincoln School, solely because of their race

and color?

Court below refused a permanent injunction

for the reasons set forth in its opinion.

Appellants contend that the answer to the

above question should be in the affirmative . . . . 8

1. Equity is bound by the law. Because equity

is bound to follow the law, it cannot refuse

to enjoin the acts of public officials which

are unauthorized by law and which are vio

lative of constitutional rights ...................... 8

2. The considerations which form the basis for

application of the equitable doctrine of bal

ance of convenience are not present in cases

involving illegal or unconstitutional action

on the part of public officials coupled with

irreparable in ju ry ........................................... 14

3. The court below gave consideration and

weight to matters beyond judicial cog

nizance and refused to give consideration

and weight to matters properly before the

court 17

VI

4. The District Court’s conclusion that appel

lees are acting in good faith is not sup

ported by the re co rd ..................................... 19

Relief . . ............................................................................ 21

Table of Cases

Allard v. Board of Education, 101 0. S. 469, 129

N. E. 718 (1920) ................................................ 11

American Smelting & Refining Co. v. Godfrey, 158

Fed. 225 (C. A. 8,1907), cert. den. 207 U. S. 597 . . . 15

Beck v. Wings Field Inc., 122 F. (2d) 114 (C. A. 3,

(1941) .......................................................................... 13

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 (1954) ...................... 9n

Briggs v. Elliot, 347 IT. S. 483 (1954) ...................... 9n

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U. S.

483 (1954) ............................................... 8 ,9n ,10,ll,15 ,16

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 (1917 )................... 18

Buscaglia v. District Court of San Juan, 145 F. (2d)

274 (C. A. 1st, 1944), cert. den. 323 U. S. 793

(1945) .......................................................................... 14,15

City of Birmingham v. Monk, 185 F. 2d 859 (C. A. 5,

1951), cert. den. 341 U. S. 940 (1951) .................... 18

Clark v. Board of Directors, 24 Iowa 266 (1868) . . . . 11

Davis v. County School Board, 347 U. S. 483 (1954) 9

Dawson v. Mayor of City of Baltimore and Lonesome

v. Maxwell, - — F. ( 2 d ) ------ (0. A. 4, March

14, 1955) ...................................................... 18

Ex parte Endo, 323 U. S. 283 (1944)........................... 18

Ex parte Farmers’ Loan & Trust Co., 129 U. S. 206

(1889) ..................... 13

Federal Power Commission v. Panhandle E. P. L.

Co., 337 U. S. 498 (1949) ......................................... 12

PAGE

PAGE

Gebhart v. Belton, 347 U. S. 483 (1954) ................... 9

Harris Stanley Coal & Land Co. v. Chesapeake 0.

Ry. Co., 154 F. 2d 450 (C. A. 6, 1946), cert. den.

329 U. S. 761 (1946) ...............................................13,15,17

Harrison v. Dickey Clay Mfg. Co., 289 IJ. S. 334

(1933) ........................................... ............................... 15

Heeht Co. v. Bowles, 321 U. S. 321 (1944) ................ 13

Hedges v. Dixon County, 150 U. S. 182 (1893) . . . . . . 12

Hill v. Darger, 8 F. Supp. 189 (S. D. Cal. 1934),

aff’d 76 F. (2d) 198 (C. A. 9, 1935) ..................... 12

Jones v. Board of Education, 90 Okla. 233, 217 Pac.

400 (1923) ....................................................................

Jones v. Newlon, 81 Colo. 25, 253 Pac. 386 (1927) .. .

Maguire, et al. v. Thomson, 15 How. (U. S.) 281

(1853) ..........................................................................

Morgan v. Commonwealth of Virginia, 328 U. S. 373

(1946) ..........................................................................

National Ben. Life Ins. Co. v. Shaw-Walker Co., I l l

F. 2d 497 (C. A. D. C., 1940), cert, den. 311 U. S.

673 (1940) .............., .................................................. 13

Pearson v. Murray, 169 Md. 478, 182 All. 590 (1936)

Pedersen v. Pedersen, 107 F. (2d) 227 (C. A. D. C.,

1939) ............................................................................

People ex rel. Workman v. Board of Education, 18

Mich. 400 (1869) ........................................................

Rowland v. New York Stable Manure Co., 88 N. J.

Eq. 168, 101 Atl. 521 (1917) ..................................... 14

State Board of Tax Commissioners v. Belt R. &

Stock Yard Co., 191 Ind. 282, 30 N. E. 6 4 1 .......... 15

State ex rel. Gibson v. Board of Education, 2 Ohio

Cir. Ct. Rep. 557 (1887) ........................................... 10,11

Steiner, et al. v. Simmons, et al., I l l Atl. (2d) 574

(Del. 1955), rev’g 108 Atl. 2d 173

11

13

11

11

11

12

18

18

V l l l

Weir v. Day, 35 O. S. 143 (1873) ................................. 11

Welton v. 40 East Oak St. Bldg., 70 F. (2d) 377

(C. A. 7,1934), cert. den. Chicago Title & Trust Co.

v. Welton, 293 U. S. 590 (1934) ............................... 14

West Edmond Hunton Line Unit v. Stanolind Oil &

Gas Co., 193 F. 2d 818 (C. A. 10th, 1952), cert. den.

343 U. S. 920 (1952) ................................................. 13

Westminster School District v. Mendez, 161 F. (2d)

744 (C. A. 9, 1947) .................................................... 11

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 (1886) ................ 11,18

Youngstown Sheet and Tube Co. v. Sawyer,-103 F.

Supp. 569 (1952) ......................................................... 14,15

Youngstown Sheet and Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 343 U. S.

579 (1952 )............................................................ . 12,15

Statute

Ohio Law 1887, p. 3 4 .................................................... 10n

Other Authorities

28 American Jurisprudence, § 5 4 ................................. 15

28 American Jurisprudence, § 55 ................................. 15

28 American Jurisprudence, § 58 ................................ 14

Pomeroy, Equity Jurisprudence, § 1966 .................... 15

Cleveland Plain Dealer, Sunday, August 15,1954 . . . 18

PAGE,

1ST THE

IntteiJ States CUintrt nf Appeal#

For the Sixth Circuit

No. 12,494

------------ -----------o-----------------------

J oyce M arie C l e m o n s , an infant, by G ertrude C l e m o n s ,

her mother and next friend, D eborah K. K o l l in s , an

infant, by N o rm a R o llin s , her mother and next friend,

M y r a D a r lin e C u m b e r l a n d , an infant, by Z e l la M ae

C u m b e r l a n d , her mother and next friend, E v e l y n M arie

S te w a rd , V ir g in ia A n n S tew ard and C a r o l y n L ouise

S te w a rd , infants, by E lsie S te w a rd , their mother and

next friend, D o ro th y M arie C l e m o n s , an infant, by R oxie

C l e m o n s , her mother and next friend, on behalf of them

selves and others similarly situated,

Plaintiffs and Appellants,

v.

T h e B oard op E d u ca tio n op H illsboro , O h io , a body cor

porate, Serve: P a u l L. U p p , Superintendent, Board of

Education, Hillsboro, Ohio, M arvel K. W i l k in , President,

E l m e r H edges, Vice President, W ilfred L . F a u l , W il l ia m

L. L u k e n s and J o h n H e n r y B r o w n , members of the

Board of Education of Hillsboro, Ohio; P a u l L. U p p ,

Superintendent of Schools of Hillsboro,

Defendants and Appellees.

A p p e a l F rom t h e D istr ict C o u rt op t h e U n ited S tates

F or t h e S o u t h e r n D istr ict op O h io , W este rn D iv isio n

--------------------------------------------------------- o — -— - — --------------- —

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement of the Facts

This is an appeal from an order of the United States

District Court for the Southern District of Ohio, Western

Division, denying a permanent injunction which would have

2

enjoined appellees from enforcing a policy of racial segre

gation in the public schools of Hillsboro, Ohio, and from

requiring infant appellants to withdraw from the Webster

and Washington Schools, solely because of their race and

color, and from requiring infant appellants to attend Lincoln

elementary school or any other school in Hillsboro which is

attended exclusively by Negro children.

The Complaint in this case was filed on the 21st day of

September 1954 (3a) along with a motion for a preliminary

injunction (10a).

A hearing on the motion for a preliminary injunction

was held on the 29th day of September 1954 (12a-56a).

Following the hearing on the motion for a preliminary

injunction, the court below, by order entered October 1,

1954, continued further proceeding thereon until two weeks

after the United States Supreme Court decides upon the

formulation of decrees in the School Segregation Cases,

Brown, et al. v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, presently

pending before it (60a).

On the 6th day of October 1954, appellants filed a notice

of appeal to this Court from said order, docketed their

appeal on November 3, 1954, and filed their brief and

appendix on appeal on November 24, 1954. Joyce Marie

Clemons, etc., et al. v. Board of Education of Hillsboro, etc.,

et al, No. 12,367.

On November 24, 1954 appellants filed a petition for

writ of mandamus, in the alternative, praying an order

directing the court below to proceed to a final determination

of appellants’ motion for preliminary injunction. A rule

to show cause issued from this Court to the court below on

December 10, 1954 directing the lower court to show cause

why it should not be required to proceed to trial. On Decem

ber 13, 1954 the court below filed its response to the show

cause order stating that an order had been entered that day

setting this case for trial on the 29th day of December 1954.

3

On the 14th day of December 1954 this Court entered an

order dismissing the petition for writ of mandamus as moot.

On the 28th day of February 1955 the appeal of appel

lants referred to in paragraph 5, supra, was dismissed as

moot by order of this Court in view of a stipulation of the

parties.

On December 28, 1954 the parties stipulated and agreed

in the court below that, the following facts were not in dis

pute (65a) :

1. The infant plaintiffs in this action are Negro chil

dren residing in the City of Hillsboro, Ohio and are

eligible to enroll in and attend the elementary schools

of that City which are under the jurisdiction and con

trol of the defendants.

2. There are three elementary schools in the City

of Hillsboro, comprising the Hillsboro City School Dis

trict. The names of these schools are Washington,

Webster and Lincoln.

3. The Lincoln School has long been maintained as

an elementary school for the exclusive attendance of

Negro children.

4. For approximately fifteen years prior to Septem

ber 7, 1954 no Negro pupil had attended either the

Webster or Washington Schools.

5. On September 7, 1954 three of the infant plain

tiffs and 29 other Negro pupils were registered in the

Webster School. On the same date four of the infant

plaintiffs and 4 other Negro pupils were registered in

the Washington School.

6. The infant plaintiffs were assigned seats in regu

lar classrooms in the schools in which they had regis

tered on September 7, 1954, on September 8, 1954.

Infant plaintiff Joyce Marie Clemons was assigned

a seat in a sixth grade classroom in Webster School.

Infant plaintiff Deborah K. Rollins was assigned a

seat in a first grade classroom in Webster School.

Infant plaintiff Myra Darline Cumberland was as

signed a seat in a first grade classroom in the Webster

School.

Infant plaintiff Evelyn Marie Steward was assigned

a seat in a fifth grade classroom in the Washington

School.

Infant plaintiff Virginia Ann Steward was assigned

a seat in a fourth grade classroom in Washington

School.

Infant plaintiff Carolyne Louise Steward was as

signed a seat in a second grade classroom in Washing

ton School.

Infant plaintiff Dorothy Marie Clemons was assigned

a seat in a second grade classroom in the Washington

School.

7. Infant plaintiffs continued in attendance at the

schools in which they had enrolled until September 17,

1954.

8. For several years prior to September 7, 1954, the

Washington and Webster Schools were overcrowded.

In view of this, plans for expanding both of these

schools were adopted several years ago and are pres

ently being executed. The Webster School is to be re

built in its entirety and the Washington School is to

have an addition.

9. The total elementary school enrollment at the

opening of school in September 1954 was 899, whereas

at the opening of school in September 1953 the total

elementary enrollment was 928.

10. The average number of pupils per room in the

Washington School on September 8,1954 when the four

infant plaintiffs and other Negro children similarly

situated were enrolled was 35.4.

5

11. The average number of pupils per room in the

Webster School on September 8, 1954 when the three

infant plaintiffs and other Negro children similarly

situated were enrolled was 38.

12. On September 8, 1954, seventeen Negro children

were enrolled in the Lincoln School which has a total

of four classrooms, only two of which are in use as

regular classrooms.

13. There are two full-time Negro teachers assigned

to the Lincoln School who teach all six elementary

grades in two rooms.

14. There are twelve regular elementary classrooms

in Washington School and twelve in Webster School.

One teacher is assigned to each room and teaches one

grade in the room.

15. The Lincoln School Zone is divided into two

parts— a northeast section which is adjacent to Lincoln

and a southeast section which is approximately nine

blocks southeast of Lincoln.

16. Three of the infant plaintiffs live in the southeast

section. In order to reach the Lincoln School these

plaintiffs must pass by the Washington School.

17. A total of 593 white children living in the School

District are transported daily from outside the City

limits for the purpose of attending elementary school

in Hillsboro. None of these pupils is assigned to the

Lincoln School. A total of 177 is assigned to Webster

and a total of 166 is assigned to Washington.

18. No Negro children attending elementary school

in Hillsboro are transported into the City.

19. The school zone lines apply only to children liv

ing within the City limits.

6

20. There is one high school in the City of Hillsboro

which is attended by both Negro and white students.

21. The segregation of pupils in grades 7-8 was dis

continued by the Board of Education in Hillsboro in

1951.

22. On August 9, 1954 the Board of Education

adopted a resolution which reads as follows:

“ That the Hillsboro City Board of Education go

on record supporting the integration program, for

children of Lincoln School, of Supt. Upp on comple

tion of Washington and Webster School buildings.”

In addition to those facts stipulated and agreed to, the

following facts were established upon the preliminary hear

ing and upon the trial:

When school opened in September 1954, elementary

school pupils registered in the schools of their choice and

were assigned seats in regular classrooms (66a). As a

result of this freedom of choice, Lincoln School was under

enrolled and Webster and Washington schools had certain

classrooms which were overcrowded (22a). Despite the

overcrowded situation at Webster and Washington, which

had existed for several years, appellees did not seek to

remedy this school capacity problem by reassigning pupils

on a normal geographical basis to Lincoln. Appellees de

cided to remedy this by continuing Lincoln as a Negro school

until the expansion of Webster and Washington is com

pleted (21a). Therefore, instead of establishing school

zones on a normal geographical basis which would have

remedied the overcrowding in Webster and Washington and

the under-enrollment in Lincoln, and at the same time would

have resulted in making Lincoln a racially integrated school

(119a-120a), appellees established school zones which were

based solely on the race and color of the pupils to be assigned

to Lincoln (21a-22a, 117a-118a). These so-called elementary

7

school zones were determined in the following manner:

Certain streets were designated for inclusion in Webster,

Washington and Lincoln zones (48a-49a). The streets in

cluded in the Lincoln zone are those streets in Hillsboro on

which only Negro families, including the appellants, live

(21a, 96a, 99a, 108a, 118a). As a result, the Lincoln zone

is composed of two non-contiguous land areas about nine

blocks apart, in neither of which the Lincoln School is

located (118a). The Lincoln School, as the map indicates,

is in the Washington School zone (Plaintiffs’ Exhibits 1

and 5). On September 17, 1954 each of the infant plaintiffs

and about forty other Negro pupils were given Pupil As

signment forms assigning them to the Lincoln School (33a-

42a).

Although white children have not been assigned to the

Lincoln School where two rooms are available as regular

classrooms, because the appellee Superintendent of Schools

believes that “ the spirit of our community would not be

happy about that” (47a, 55a, 105a, 106a 109a), four Negro-

pupils were permitted to remain in the Webster School

and eight in the Washington School, after the school zones

were established. These children live on streets on which

wrhite families live (107a-108a).

The earliest date on which the present school construc

tion program shall be completed is approximately June

1957 (46a).

While the Washington School building is under renova

tion in the future, all children there attending will be tem

porarily housed in the new constructed Webster School

Building placing approximately 900 students in the latter-

school, although Lincoln is still under-enrolled (46a).

School attendance zones can be established in Hillsboro

by the appellee Board of Education which will not result

in Lincoln being an all-Negro school, taking into considera

tion those factors which are generally taken into eonsidera-

8

tion by school administrators in establishing elementary

school zones (119a-120a).

Following the trial, the court below filed its opinion on

January 18, 1955 in which it set forth its reasons for deny

ing the permanent injunction (139a), followed by its order

on February 16, 1955 denying the permanent injunction

(145a). From this order appellants appeal.

Appellants assign as error the district court’s refusal

to grant a permanent injunction and the reasons relied on

by it for its refusal.

ARGUM ENT

I. Did the court below abuse its discretion in refus

ing to grant a permanent injunction enjoining appellees

from enforcing a policy of racial segregation in the ele

mentary schools and from requiring infant appellants

to withdraw from Washington and Webster Schools

and enroll in Lincoln School, solely because of their

race and color?

Court below refused a permanent injunction for the

reasons set forth in its opinion.

Appellants contend that the answer to the above

question should be in the affirmative.

The court below abused its discretion in refusing to

grant a permanent injunction for the following reasons: 1

1. Equity is bound by the law. Because equity is

bound to follow the law, it cannot refuse to enjoin

the acts of public officials which are unauthor

ized by law and which are violative of constitu

tional rights.

The court below regarded the action of the United States

Supreme Court in setting down the School Segregation

Cases, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U. S.

9

483 (1954), for reargument as to the kind of decrees it shall

issue in those cases as dispositive of the right of appellants

to an injunction in this case (56a-58a). Its refusal to grant

the permanent injunction appears to be based, although not

expressed in its opinion, on the erroneous assumption that

the United States Supreme Court has already ruled, as

a matter of law, that all local school authorities having

segregated elementary schools are entitled to time in which

to cease segregation (58a, 102a, 123a) ; and that by the

cessation of segregation is meant simply provision for the

integration of Negro children into white schools and not

the drawing of normal geographical school zones or the

integration of white children into Negro schools (57a-58a).

Appellants contend that, contrary to the assumption of

the District Court (57a), the circumstances of this case are

not identical with the circumstances of the School Segrega

tion Cases and the Court’s action with regard to final

decrees in those cases and even the Court’s ultimate decrees

in those cases are not determinative of the rights of appel

lants here.

a. In the School Segregation Cases, supra, racial segre

gation on the part of the school authorities was either man

datory by the law of the state,1 permitted by the law of the

state,1 2 or, at the very least, recognized by legislative appro

priation statutes.3 Suit was therefore brought in the federal

district courts involved to enjoin the enforcement of stat

utes of state-wide application, the constitutionality of which

had been upheld by many state courts of last resort and had

been involved in several cases before the United States

Supreme Court itself, without rejection, prior to its deci

sion in those cases. In other words, the school authorities

1 Briggs v. Elliot; Davis v. County School Board; Gebhart v.

Belton, 347 U. S. 483 (1954).

2 Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U. S. 483 (1954).

3 Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 (1954).

10

ill those cases did not come into court devoid of legislative

authorization and the Negro pupils in those cases, prior to

bringing suit, had never been admitted to schools of their

choice.

The United States Supreme Court in those cases, there

fore, declared unconstitutional for the first time the legisla

tive enactments pursuant to which the school authorities in

those cases had operated their schools for more than half

a century. In giving consideration to the question of con

stitutionality at the time of reargument of those cases in

December 1953, the Court has announced that it did not

have the opportunity to discuss fully with counsel for the

parties the kind of decrees it should issue. For this reason,

and because of the great variety of local conditions in those

cases, and the complex problems which formulation of

decrees presents in those particular cases, the Court set

down those cases for reargument on the question of decrees

alone, the law having been settled. In this case, the court

below had ample opportunity to discuss with counsel the

decree to be issued.

Thus, the legal and equitable status of the pupils in the

School Segregation Cases was fundamentally different at the

time of instituting suit and at the end of the case from the

legal and equitable status of infant appellants here.

In this case, racial segregation by the local school

authorities before the court is neither required nor per

mitted by the laws of the State of Ohio and its existence

is not recognized by the legislature. In short, the segre

gation here complained of is without legislative authority

therefor and is, in fact, contrary to state law, having been

barred by the state legislature since 1887.4 State ex rel.

Gibson v. Board of Education, 2 Ohio Cir. Ct. Rep. 557

(1887). Therefore, unlike the school authorities in the

School Segregation Cases, the school authorities here are

4 Ohio Laws 1887, p. 34.

11

not acting pursuant to a state statute which the district

court was asked to declare unconstitutional. Appellees’

action in segregating here is illegal under the law of the

state and might have been enjoined in a state court, under

state law, by state officials pledged to uphold the law of the

State of Ohio. Nevertheless, under these circumstances,

even prior to the decision in the School Segregation Cases,

supra, appellants were and are entitled to invoke the juris

diction of a federal court of equity to protect rights guar

anteed them by the Fourteenth Amendment. Westminister

School District v. Mencles, 161 F. (2d) 744 (C. A. 9, 1947),

cf. Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 (1886).

In other words, when infant appellants registered in the

Washington and Webster schools in September 1954 and.

were assigned seats in regular classrooms, they were law

fully admitted under the law of the state, State ex rel.

Gibson v. Board of Education, supra; cf. Jones v. Newion,

81 Colo. 25, 253 Pac. 386 (1927); Clark v. Board of Direc

tors, 24 Iowa 266 (1868); Pearson v. Murray, 169 Md. 478,

182 Atl. 590 (1936); People ex rel. Workman v. Board of

Education, 18 Mich. 400 (1869) ; Jones v. Board of Educa

tion, 90 Okla. 233, 217 Pac. 400 (1923), and under the law

of the state acquired the lawful status of duly enrolled

elementary school pupils, which a court of equity was bound

to protect against illegal action on the part of appellees.

Steiner, et al. v. Simmons, et al., I l l Atl. (2d) 574 (Del.

1955), rev’g. 108 Atl. 2d 173; cf. Allard v. Board of Educa

tion, 101 0. S. 469, 129 N. E. 718 (1920); Weir v. Day, 35

O. S. 143 (1873). A federal court of equity was bound to

protect appellants since the illegal action of appellees

under the law of the state deprived appellants of constitu

tional rights. Westminister School District v. Mendez,

supra, cf. Yick Wo v. Hopkins, supra.

b. When the United States Supreme Court announced

its decision in May 1954 in the School Segregation Cases,

supra, every American elementary school pupil acquired a

12

federal right against all state authority, legislative, judi

cial, and administrative, not to be segregated, solely because

of race, in the public schools. In view of this decision, no

school authority could thereafter, in determining school

attendance zones make new determinations regarding school

attendance which are based solely on race and color, such

as were purposely and intentionally made by appellees here

on September 13, 1954 after infant appellants had been en

rolled in the Washington and Webster schools. The effect

of the Supreme Court’s decision is to deny to the states

power to segregate thereafter. This decision all courts

must follow as the supreme law of the land, although an

entirely distinct and separate question arises in the five

cases before the Supreme Court as to how an adjustment

to a non-segregated system is to be made from an existing

segregated system under the circumstances peculiar to each

of those cases. Therefore, since the United States Supreme

Court has declared the law, the court below should have

followed it with respect to the school attendance zones

established by appellees in this case in September 1954 which

were intended to be, and which in fact are, a new stratagem

for achieving racial segregation in the public schools.

Appellants contend that the court below, in the exer

cise of its equity powers, was bound by the law of the state

and the federal law as of the time of the decree. Cf. Youngs

town Sheet and Tube Co., v. Sawyer, 343 U. S. 579 (1952);

Federal Power Commission v. Panhandle E. P. L. Co., 337

U. S. 498 (1949); Hedges v. Dixon County, 150 U. S. 182

(1893) ; Maguire et al. v. Thomson, 15 How. (U. S.) 281

(1853); Hill v. Darger, 8 F. Supp. 189, 191 (S. D. Cal. 1934),

aff’d 76 F. (2d) 198 (C. A. 9th 1935). It was bound to

exercise its discretion in accordance with the law and enjoin

illegal acts of public officials which deny constitutional

rights. Cf. Youngstown Sheet & Tube v. Sawyer, supra.

Therefore, when it denied a permanent injunction although

appellants were clearly entitled to it as a matter of law, it

13

abused its discretion. Ex Parte Farmers’ Loan d Trust

Co., 129 U. S. 206, 215 (1889); Beck v. Wings Field, Inc.,

122 F. (2d) 114, 116 (C. A. 3 1941); National Ben. Life Ins.

Co. v. S'haw-Walker Co., I l l F. 2d 497, 507 (C. A. D. C.

1940); Pedersen v. Pedersen, 107 F. (2d) 227, 234 (C. A,

D. C. 1939); cf. West Edmond Hunton Line Unit v. Stano-

lind Oil d Gas Co., 193 F. 2d 818 (C. A. 10th 1952).

In Beck v. Wings Field Inc., supra, the Court said at

page 116:

“ Abuse of discretion in law means that the court’s

action was in error as a matter of law. And where

such abuse exists, reversal will be ordered.”

In the Supreme Court case of Hecht Co. v. Bowles, 321

U. S. 321 (1944), cited by the court belo w as containing

language which is controlling here, the only question decided

by the Court was whether under the Emergency Price Con

trol Act of 1942 issuance of an injunction for violation of

the Act was mandatory or within the discretion of the

court. The Court ruled only that Congress intended issu

ance of injunction to be discretionary with the court in

accordance with the historic requirements of equity prac

tice. The Court expressly did not pass on the question

whether the District Court in refusing to issue the injunc

tion in that case abused its discretion but remanded the

case to the Court of Appeals for that determination (at

p. 331).

Here appellants do not challenge the conclusion that

applications for issuance of injunctions are addressed to

the sound discretion of equity courts. Appellants say that

the exercise of discretion is controlled by law and that the

District Court’s discretion is subject to review for compli

ance with the law. When abuse of discretion is found, as

is here charged, a court of appeals must reverse. Ex Parte

Farmers’ Loan d Trust Co., supra; cf. Harris Stanley Coal

& Land Co. v. Chesapeake O. By. Co., 154 F. 2d 450 (C. A. 6

1946), cert. den. 329 U. S. 761.

14

2. The considerations which form the basis for

application of the equitable doctrine of balance

of convenience are not present in cases involving

illegal or unconstitutional action on the part of

public officials coupled with irreparable injury.

The court below in its opinion ruled that injunction

should not be granted in this case because to order the

infant appellants reinstated in the Washington and Web

ster schools at this time would seriously disrupt the orderly

procedures and administration of those schools to the detri

ment of all students affected by the order (139a). In other

words, the issuance of an injunction would seriously incon

venience appellees and the other students. Thus the court

below balanced the conveniences and concluded that the-

necessity for continuing the orderly procedures and admin

istration of the Washington and Webster schools out

weighed the injury to appellants in this case.

The equitable doctrine of balancing the equities, or the

balance of the relative convenience, injury, or hardships of

the parties, developed with respect to, and has been limited

in its application to, cases involving injunction against

nuisance, interference with easements, and to restrain pollu

tion or diversion of water courses. 28 Am. Jur. Injunctions,

§ 58. It is limited to consideration on applications for tem

porary, interlocutory, or preliminary injunctions in such

cases. 28 Am. Jur. Injunction, §58; Youngstown Sheet &

Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 103 F. Supp. 569, 576-577 (1952); Bus-

caglia v. District Court of San Juan, 145 F. (2d) 274 (C. A.

1, 1944), cert. den. 323 U. 8. 793 (1945); Rowland v. New

York Stable Manure Co., 88 N. J. Eq. 168, 101 Ati. 521

(1917).

In cases in which the doctrine is applicable, its applica

tion is clearly not made in favor of defendants in cases

where the defendants’ acts were unlawful, see, Youngstown

Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, at 576, affirmed, 343 U. S. 579

(1952); Welton v. 40 East Oak St. Bldg., 70 F. (2d) 377, 383

15

(C. A. 7th 1934), cert, den., Chicago Title £ Trust Co. v.

Welton, 293 IT. S. 590 ; American Smelting & Refining Co.

v. Godfrey, 158 Fed. 225 (C. A. 8, 1907), cert. den. 207

U. S. 597; State Board of Tax Com’rs. v. Belt B,. £ Stock

Yard Co., 191 Ind. 282, 30 N. E. 641; Buscaglia v. District

Ct. of San Juan, supra, or where the injury to the plaintiff

is irreparable. Youngstown Sheet £ Tube Co. v. Sawyer,

343 U. S. 579 (1952); see, Harrison v. Dickey Clay Mfg. Co..

289 U. S. 334, 338 (1933); Harris Stanley Coal £ Land v!

Chesapeake £ 0. By. Co., 154 F. 2d 450 (C. A. 6 1946), cert,

den. 329 IT. S. 761; Pomeroy, Equity Jurisprudence, § 1966;

28 Am. Jur. Injunctions, §§ 54, 55.

Clearly the doctrine is not applied in favor of defend

ants when defendants are public officials whose illegal acts

deprive plaintiffs of constitutional rights and subject plain

tiffs to irreparable injury. Youngstown Sheet £ Tube Co.

v. Sawyer, 103 F. Supp. 569, 576-577, aff’d 343 U. S. 579

(1952).

In the School Segregation Cases, supra, the United

States Supreme Court has said, in language too plain to be

misunderstood by anyone, that the injury which results to

the Negro child who is forced to attend a racially segre

gated school is irreparable. The Court said at page 494:

<<# * * rpQ sep.arate them from others of similar

age and qualifications solely because of their race

generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status

in the community that may affect their hearts and

minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone. The effect

of this separation on their educational opportunities

was well stated by a finding in the Kansas case * * * :

‘ Segregation of white and colored children in

public schools has a detrimental effect upon the

colored children. The impact is greater when it

has the sanction of the law; for the policy of sepa

rating the races is usually interpreted as denot

16

ing the inferiority of the Negro group. A sense

of inferiority affects the motivation of a child to

learn. Segregation with the sanction of law,

therefore, has a tendency to retard the educa

tional and mental development of Negro children

and to deprive them of some of the benefits they

would receive in a racially integrated school sys

tem.’ ”

Despite the fact that the appellees here were acting ille

gally, and despite the fact that that illegal action deprives

infant appellants of their right to the equal protection of

the laws, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, supra,

and despite the fact that appellees’ illegal action subjects

infant appellants to irreparable injury, the court below

denied an injunction on the ground that appellants’ right

thereto is outweighed by the inconvenience to appellees and

the other students if the injunction is granted.

But assuming, at this point, that the doctrine of the bal

ance of convenience applies here, what are the relative injur

ies involved as a practical matter! In addition to the fact

that infant appellants will suffer psychological injury which

is irreparable, infant appellants will suffer the deprivation

of at least two years of an elementary school education

which is equal to that received by students permitted to

attend Washington and Webster schools. Appellees on the

other hand, if the injunction is issued, will suffer the incon

venience of choosing between continuing to operate the

Washington and Webster schools as they have in the past,

with certain classrooms overcrowded, or drawing normal

school attendance zones based on geographical considera

tions and other considerations relative to such matters, such

as, traffic hazards and school capacity. The other students,

if the injunction is issued, would continue to attend schools

which are slightly overcrowded in certain classrooms, or

approximately sixty of them will suffer the inconvenience of

17

having to attend the school nearest their home, i. e., the

Lincoln School.

Thus, appellants contend that, even assuming the doc

trine of balancing the equities is applicable here, the equities

are clearly on the side of infant appellants in this case.

Therefore, the doctrine of balancing the conveniences, if

applicable here, was erroneously applied because based on

an erroneous evaluation of the equities, conveniences or in-

juris involved. Harris Stanley Coal ■<& Land v. Chesapeake

<& Ohio Ry. Co., 154 F. (2d) 450' (C. A. 6, 1946), cert, den.,

329 U. S. 761.

3. The court below gave consideration and weight

to matters beyond judicial cognizance and

refused to give consideration and weight to

matters properly before the court.

Over the objection of appellants, the court below intro

duced into the record testimony concerning an alleged burn

ing of the Lincoln School in the summer of 1954 by an

alleged burglar and arsonist for the express purpose of

influencing the decision of this court and/or the United

States Supreme Court upon appeal (112a-114a). The court

below was of the opinion that the record should contain evi

dence concerning the action of an alleged criminal despite

the fact that, it was the appellees themselves who made it

clear to the court that this alleged criminal had no connec

tion with these appellants (53a-54a). The court below was

of the opinion, unsupported by anything in the record, that

the fire incident represented “ an air and an atmosphere in

Hillsboro that the Board should have some right to take

into account” (113a), which air and atmosphere the court

below felt should be in the record for the “ benefit of the

Court of Appeals, for the Supreme Court if necessary”

(113a).

In other words, the court below was of the opinion that

despite the fact that it is settled law in Ohio since 1887 that

18

racial segregation in the schools is prohibited, and despite

the fact that appellees introduced nothing into the record

concerning community attitudes of a hostile nature, except

the apprehensions of the Superintendent which proved to

be baseless (105a), appellees nevertheless have a right, in

the exercise of their discretion, to operate the schools of

Hillsboro on a racially segregated basis for an indefinite

period in the future to avoid development of apprehended

community hostility against the lawful operation of the

public schools.

In short, the court below was of the view that community

hostility to minority groups takes precedence over require

ments of law and that consideration and weight must he

given to anti-Negro bias in the operation of schools by school

authorities as well as the courts. Appellants contend that

this view is clearly contrary to law. Tick Wo v. Hopkins,

118 U. 8. 356, 373 (1886); Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60,

74-75, 80-81 (1917); Ex parte Endo, 323 U. S. 283, 302

(1944); Morgan v. Commonwealth of Virginia, 328 U. S.

373, 380 (1946); City of Birmingham v. Monk, 185 F. 2d 859,

861 (0. A. 5, 1951), cert, den. 341 U. 8. 940 (1951); Dawson

v. Mayor of City of Baltimore and Lonesome v. Maxwell,

------ F. 2d ——— (C. A. 4, March 14, 1955); Steiner v. Sim

mons, 111 A. 2d 574 (Del. 1955), rev’g 108 A. 2d 173.

Introduction of this evidence into the record was

especially prejudicial to appellants because it was intro

duced to convey the impression that the Lincoln School was

burned by a person opposed to ending racial segregation in

the public schools, whereas, although the record does not

disclose the motive for burning the school, it is common

knowledge that the school was burned by one who allegedly

did so in order to hasten the end of segregation.5

5 See report of incident in the newspaper, Cleveland Plain Dealer

Sunday, August 15, 1954.

19

Therefore, appellants contend that introduction of this

testimony was clearly prejudicial to appellants, constitutes

error and an abuse of discretion on the part of the court

below.

On the other hand, the court below gave no considera

tion or weight to the fact that the Lincoln School was under

enrolled and could readily absorb students of both races who

were causing the overcrowding in certain classrooms in the

Washington and Webster schools (67a). It gave no con

sideration or weight to the fact that normal school attend

ance zones could be established by appellees, taking into

consideration those factors normally taken into considera

tion by school administrators in establishing school zone

lines, which would relieve both the overcrowding in Wash

ington and Webster and end the segregation at Lincoln

(119a-120). It gave no consideration or weight to the fact

that the alleged community hostility was not shown to exist

in fact but was merely speculation on the part of the super

intendent (47a, 55a, 105a, 106a, 109a). It gave no consid

eration or weight to the fact that the high school and the

junior high school had been integrated without incident

(105a).

4. The District Court’s conclusion that appellees are

acting in good faith is not supported by the

record.

The court below concluded that the good faith and sin

cerity of the appellees “ in their endeavor to overcome what

they concede as temporary segregation, is amply supported,

by the record” (142a).

Appellants contend that only bad faith is exhibited by

the following facts appearing in the record:

1) Appellees reinstituted the policy of assigning all

Negro students to Lincoln School with full knowledge that

such a policy is prohibited by the law of the state as well as

by the supreme law of the land (55a).

20

2) Appellees alleged in their Answer “ that attendance

in the elementary schools * # * is determined by the place

of residence of the pupils concerned and not by race, color,

or national origin” (62a).

3) Appellee Superintendent testified that the problem

here was one of space (103a), yet the stipulated facts indi

cate that there are two rooms in the Lincoln School which

are available as regular classrooms and that in the other

two rooms only seventeen Negro children are enrolled

(67a).

4) While the Washington building is under renovation

in the future, all children there attending will double up in

the Webster building placing approximately 900 students

in the Webster building (46a), clearly indicating that appel

lees have no fears arising from overcrowding children in

one building.

5) The school zone lines adopted by appellees were a

“ subterfuge” for continuing racial segregation in Lincoln

(140a) rather than a frank admission of the so-called policy

of “ temporary segregation” (100a).

6) School zone lines can be established by appellees

which not only relieve certain overcrowded classrooms in

Washington and Webster but which would also end the seg

regation policy at Lincoln, thus providing Hillsboro with

three racially integrated schools now rather than two

racially integrated schools two and a half years from now

(120a).

7) Throughout the trial the appellee Superintendent in

sisted that the school zone lines adopted by the Board were

determined by residence rather than by race (34a, 38a, 40a,

41a, 99a, 106a, 107a, 108a). Appellee Chairman of the

Board of Education likewise insisted that residence was

the basis of the lines rather than race (25a, 28a, 29a, 30a).

As a matter of fact, the appellee Chairman of the Board

testified that white children were not assigned to Lincoln

because there is not room for them there (28a-29a).

21

8) Appellees have not passed a resolution to the effect

that Lincoln School will be abandoned. The Superintend

ent conceded that abandonment of the Lincoln School is

“ just talk” (47a).

9) Appellees integrated the junior high school only a

few years ago without incident (105a).

10) No racial incidents have occurred as a result of per

mitting eleven Negro children to remain in the Washington

and Webster schools.

11) Appellees cite no concrete evidence of present com

munity hostility to operating the Hillsboro schools in accord

ance with the law of the state and the federal constitutional

mandate of equal protection and cite no inability on the

part of law enforcement officers to effectively deal with

any racial incidents which may occur.

Relief

Appellants respectfully urge that the judgment of the

court below be reversed, and the court below directed to

enter an injunction enjoining appellees from continuing

to enforce the racial segregation policy through enforce

ment of the present so-called school zone lines and enjoin

ing appellees from requiring infant appellants to withdraw

from the Washington and Webster schools and attend Lin

coln or any other racially segregated schools in Hillsboro.

Respectfully submitted,

R u ssell L. C ar te r ,

J am e s H. M cG h e e ,

949 Knott Building,

Dayton 2, Ohio.

C on stan ce B a k e r M o tle y ,

T hurgood M a r s h a l l ,

107 West 43rd Street,

New York 36, N. Y.,

Counsel for Appellants.