Belk v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education Final Form Brief of Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

May 20, 2000

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Belk v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education Final Form Brief of Plaintiffs-Appellants, 2000. 5a9e1597-c69a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/10c3b763-ec5c-4538-9f79-9c1c2a211242/belk-v-charlotte-mecklenburg-board-of-education-final-form-brief-of-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Copied!

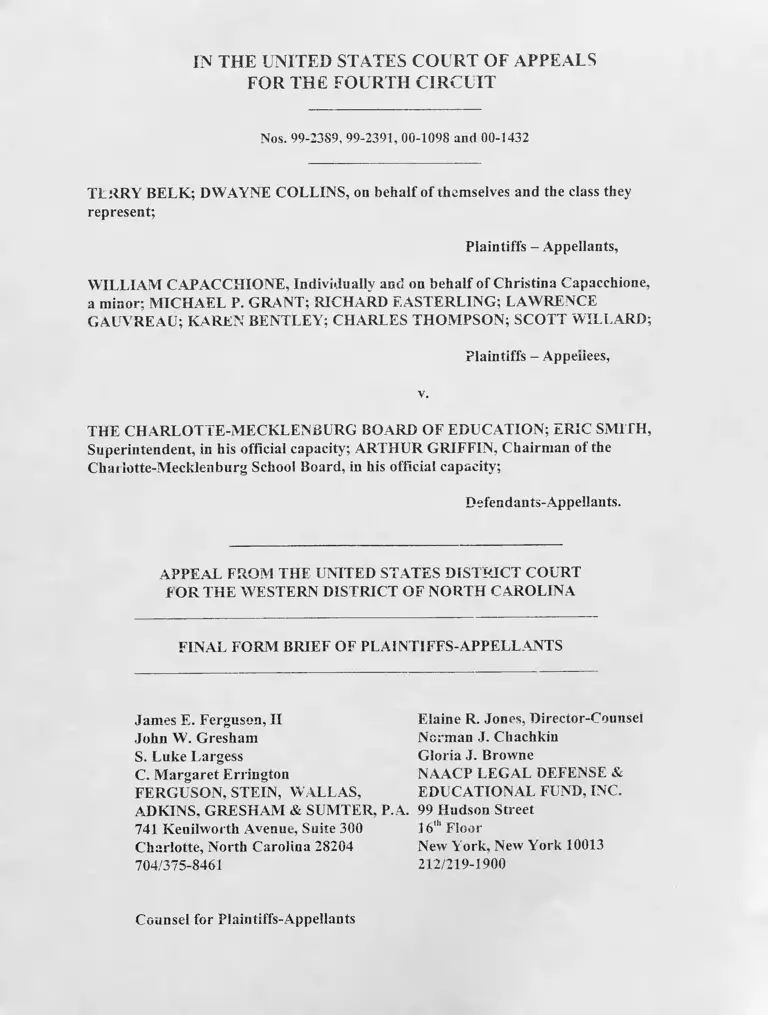

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 99-2389, 99-2391, 00-1098 and 00-1432

TERRY BELK; DWAYNE COLLINS, on behalf of themselves and the class they

represent;

Plaintiffs - Appellants,

WILLIAM CAPACCHIONE, individually and on behalf of Christina Capacehione,

a minor; MICHAEL P. GRANT; RICHARD EASTERLING; LAWRENCE

(»ALA REAL; KAREN BENTLEY; CHARLES THOMPSON; SCOTT WILLARD;

Plaintiffs - Appellees,

v.

THE CHARLOTTE-MECKLENBURG BOARD OF EDUCATION; ERIC SMITH,

Superintendent, in his official capacity; ARTHUR GRIFFIN, Chairman of the

Charlotte-Meckienburg School Board, in his official capacity;

Defendants-Appellants.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

FINAL FORM BRIEF OF PLAIN ! !FFS-APPELLANTS

James E. Ferguson, II

John W. Gresham

S. Luke Largess

C. Margaret Errington

FERGUSON, STEIN, WALLAS,

ADKINS, GRESHAM & SUMTER, P.

741 Kenilworth Avenue, Suite 300

Charlotte, North Carolina 28204

704/375-8461

Elaine R. Jones, Director-Counsel

Norman J, Chachkin

Gloria J. Browne

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE &

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

A. 99 Hudson Street

J 6th Floor

New York, New York 10013

212/219-1900

Counsel for Plaintiffs-Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

TABLE OF CASES AND AUTHORITIES ..............................................................1V

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT ............................................................. 1

ISSUES PRESENTED ............................ 2

STATEMENT OF THE C A SE....................................................................... 3

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS .....................................................

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .......................................................

ARGUMENT .....................................................................................

I STANDARD OF REVIEW .............................................................

H THE DISTRICT COURT MADE NUMEROUS SIGNIFICANT

ERRORS OF LAW IN FINDING UNITARY STATUS .............

A CMS HAS NOT ELIMINATED THE VESTIGES OF

DISCRIMINATION IN STUDENT ASSIGNMENT......

1. The Martin Trial Involved Unitary Status ................

2. Overcrowding Was A Constitutional Concern ........

3. Consideration of White Flight In Siting

Decisions Was Unlawful.............................................

4. Transportation Is A Constitutional C oncern.............

5. The Trial Court Wrongfully Minimized The Burden

Of Proof And Made Clearly Erroneous Factual

Findings As To Siting .................................................

i

B.

C.

D.

6. The Evidence At Trial On The Four Martin

Requirements Demonstrates That CMS Has Not

Remedied Continuing Effects Of The Prior

De Jure Segregation ..............................................................26

a. School Siting And Transportation........................... 26

b. Location Of Earliest Primary Grades...................... 28

c. Monitoring Transfers...............................................28

7. The Failure To Properly And Adequately Address

Martin Fatally Impacts The Court’s Analysis Of

Student Assignment .............................................................. 31

a. Level Of Compliance ...............................................31

b. Demographics .......................................................... 32

8. The Court Erred By Failing To Evaluate The

Efficacy Of The Board’s Desegregation

Strategies................................................................................36

THE COURT’S CONCLUSION THAT CMS HAD

ATTAINED UNITARY STATUS AS TO RESOURCES

AND FACILITIES IS CLEARLY ERRONEOUS......... ..............38

1. Burden of P roof.....................................................................39

2. The Prior Orders .................................................. 40

3. Present Disparities Are Clearly Vestiges Of

Segregation ........................................................................... 41

4. Partial Unitary Status ........................................................... 42

5. The Court’s Finding That Facilities And Resources

Are Equal Is Clearly Erroneous ..........................................43

THE COURT’S CONCLUSION THAT CMS HAD

ATTAINED UNITARY STATUS AS TO FACULTY IS

CLEARLY ERRONEOUS .............................................................. 45

INEQUITIES IN THE QUALITY OF EDUCATION

PREVENT A UNITARY STATUS FINDING .............................48

3

ni. ................ ........................................THE MAGNET PROGRAM

IV ..............THE INJUNCTION WAS UNAUTHORIZED BY LAW AND

J Z ' Z Z .........................................................UNSUPPORTED BY FACT

CONCLUSION.............................................................................................. 53

48

49

4

TABLE OF CASES AND AUTHORITIES

Page

Cases

Adarand Constructors, Inc. v. Pena, 515 U.S. 200 (1995).................................................. 52

Board o f Education v. Dowell, 498U.S. 237 (1991)............................................... 18, 19, 36

Capacchione v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board o f Education, 57 F.Supp.2d 228

(W.D.N.C. 1999).......................................................................................................... passim

Coalition to Save Our Children v. State Bd. ofEduc., a ff’d,

90 F.3d 752 (3rd Cir. 1996)..........................................................................................39, 40

Coalition to Save Our Children v. State Bd. ofEduc., 901 F.Supp 784 (D. Del. 1995),.. 32

Columbus Bd. ofEduc. v. Penick, 443 U.S. 449, n,13 (1979)............................................ 33

Cuthbertson v. Charlotte Mecklenburg Bd. ofEduc., No. 1974, Slip Op. (1973), 535 F.2d

1249 (4th Cir. 1976); cert, denied., 429 U.S. 831 (1976)................................................5

Dayton Bd. ofEduc. v. Brinkman, 443 U.S. 526 (1979)............................................... . 33

Freeman v. Pitts, 503 U.S. 467 (1992)..........................................................................passim

Green v. New Kent County Board o f Education, 391 U.S. 430 (1968)..................... passim

In re Brice, 188 F.3d 576, 577 (4th Cir. 1999 .................................................................... 18

Jenkins v. Missouri, 122 F.3d. 588 (8th Cir. 1997)...............................................................40

Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, Denver, 413 US 189, 201 (1973)...........................................22

Manning v. School Board, 24 F.Supp.2d 1277 (M.D.Fla. 1998)........................................32

Martin v. Charlotte Mecklenburg Bd. OfEduc., 475 F.Supp. 1318 (1979)..............passim

Martin v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. ofEduc., 626 F.2d 1165 (4* Cir. 1980), cert.

denied, 450 U.S. 1041 (1981)..............................................................................................5

Miller v. Johnson, 515 U.S. 900 (1995)................................................................................ 52

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. ofEduc., No. 1974 Slip Op.,

April 17, 1980............................................................. .................................................. 5, 10

5

Raso v. Lago, 135 F.3rd 1+1 (1st Cir. 1998)........................................................................... 52

Riddick v. School Bd. o f Norfolk, 784 F.2d 521, 528-29 (4lh Cir. 1986)...................... 23, 35

School Bd. v. Baliles, 829 F.2d. 1308 (4th Cir. 1987).................................................... 39, 42

Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. 630 (1993)....................................................................................... 52

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. ofEduc., 243 F.Supp. 667 (W.D.N.C. 1965).... 3, 6

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. ofEduc.,

300 F.Supp. 1358. (W.D.N.C. 1969)........................................................................passim

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. ofEduc.,

306 F. Supp. 1291 (W.D.N.C.1969)............................................................................ 7, 46

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. ofEduc., 306 F. Supp. 1299 (W.D.N.C. 1969)...... 3

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. ofEduc., 311 F.Supp. 265 (W.D.N.C. 1970)......4, 7

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. ofEduc., 318 F.Supp. 786 (W.D.N.C. 1970)..........4

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. ofEduc.,

328 F. Supp. 1346 (W.D.N.C.1971)......................................... ............................... 10, 24

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. ofEduc.,

334 F.Supp. 623 (W.D.N.C. 1971)..............................................................................4, 24

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. ofEduc.,

362 F.Supp. 1223 (W.D.N.C. 1973)..........................................................................passim

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. ofEduc., 369 F.2d 29 (4th Cir. 1966)...................... 3

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. ofEduc.,

379 F.Supp. 1102 (W.D.N.C. 1974)........................................................................ 4, 8,28

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. ofEduc., 402 U.S. 1 (W.D.N.C.1971)..passim

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. ofEduc., 453 F.2d 1377 (4th Cir. 1972)......... 4

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. ofEduc., 66 F.R.D. 483 (W.D.N.C. 1975)... 41

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. ofEduc., 67 F.R.D. 648 (W.D.N.C. 1975)..........4, 9

6

Swann v. Charlotte-Meckienburg Bd. ofEduc., , No. 1974,

Slip Op., (April 3, 1974)........................................................................................................... 4

Tuttle v. Arlington County Schools, 195 F.3d 698 (4th Cir. 1999)................................ 51

U.S. v. City o f Yonkers, 181 F.3d. 301 (2nd Cir. 1999).........................................................42

United States v. Board o f Public Instr. o f St. Lucie County,

977 F.Supp. 1202 (S.D. Fla. 1997)................................................................................... 37

United States v. City o f Yonkers, 833 F.Supp. 214, n.3 (S.D.N.Y. 1993).......................... 40

United States v. Scotland Neck Bd. ofEduc., 407 U.S. 484 (1972)................................... 24

United States v. State o f Georgia, Troup County,

171 F.3d. 1344 (11th Cir. 1999).... ......................................................................... 6, 37, 43

United Stated v. Unified School Dist. No. 500, Kansas Citv,

974 F.Supp. 1367 (D. Kan. 1977)..................................' .................................................42

Vaughns v. Board o f Education o f Prince Georges County,

758 F.2d 983 (4th Cir. 1985)....................................................................................... 18, 48

Statutes

28 U.S.C. § 1291...................................... 1

28 U.S.C. § 1294...................................................................................................................... 1

28 U.S.C. § 1331......................................................................................................................... 1

28 U.S.C. § 1343.........................................................................................................................1

7

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

The district court obtained jurisdiction over this action, which seeks to redress

deprivations of rights secured by the Constitution and statutes of the United States,

pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1331 and 1343. This appeal is from a final order and judgment

entered on September 9, 1999. The appeal was filed on October 7, 1999. This court has

jurisdiction to determine the appeal pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1291 and 1294.

8

ISSUES PRESENTED

DID THE DISTRICT COURT COMMIT ERRORS OF LAW AND

FACT IN DETERMINING THAT CMS HAD OBTAINED UNITARY

STATUS AND IN DISSOLVING THE PRIOR INJUNCTIVE ORDER

OF THE COURT1?

DID THE DISTRICT COURT ERR IN DETERMINING THAT THE

CMS MAGNET SCHOOL ADMISSIONS PROCESS VIOLATED THE

RIGHTS OF THE INTERVENORS?

DID THE DISTRICT COURT ERR. IN ENJOINING CMS FROM

ASSIGNING CHILDREN TO SCHOOLS OR ALLOCATING

EDUCATIONAL OPPORTUNITIES AND BENEFITS BASED ON

ANY FACTOR WHICH TAKES RACE INTO ACCOUNT?

9

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This historic case originated with a lawsuit filed in 1965 by black parents1 seeking

an end to the long-standing operation of racially segregated schools by the Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Schools (“CMS” or “the Board”). The tnal court found that CMS had no

affirmative legal duty to draw attendance zones that would desegregate schools, but that

its policy on teacher assignment was inadequate. Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. o f

Educ., 243 F.Supp. 667 (W.D.N.C. 1965).2 This court affirmed. 369 F.2d 29 (4th Cir.

1966).

In 1968, the Swann Plaintiffs sought further relief pursuant to the Supreme

Court’s decision in Green v. New Kent County Board o f Education, 391 U.S. 430 (1968).

The district court found the schools unlawfully segregated and ordered CMS to devise

plans to desegregate students and faculty. 300 F.Supp. 1358. (1969). In August 1969,

the court approved “with great reluctance,” for one year only, a plan closing seven black

schools and busing the students to outlying white schools. 306 F. Supp. 1291 (1969). On

November 7 and December 1, 1969, the court ordered CMS to devise a constitutional

plan for implementation beginning in 1970. 306 F. Supp. 1299 (1969).

1 The original plaintiffs have been known historically as the “Swann

Plaintiffs.” This appellation is used even though Terry Belk and Dwayne Collins have

joined this litigation as representative plaintiffs.

2 The citations to the many decisions in Swann from 1965 to 1975 carried

the same case caption. The Swann Plaintiffs do not repeat the case name, or the

“W.D.N.C.” reference in the citation, and cite those cases with the publication reference

and year.

10

In February, 1970, finding CMS in default of its obligations, the court ordered

implementation of a plan for elementary schools and accepted the system’s secondary

school plan with some modifications. 311 F.Supp. 265 (1970). On remand from this

Court, 431 F.2d 138 (4th Cir. 1970), the district court found that the plan was reasonable.

318 F.Supp. 786 (1970). The Supreme Court affirmed. 402 U.S. 1 (1971).

CMS immediately submitted a plan which the district court rejected. It then

submitted another plan which the court accepted with certain modifications. 328 F. Supp.

1346 at 1349-50 (1971). This Court again affirmed. 453 F.2d 1377 (4th Cir. 1972).

The Swann Plaintiffs moved for relief alleging that CMS’s actions were restoring

segregation. A group of white families moved to intervene, alleging that CMS had

exempted wealthier whites in southeast Charlotte from the plan. The court found merit in

both positions, but declined court intervention “for now, at least.” 334 F.Supp. 623, 626

(1971).

The Swann Plaintiffs sought further relief in 1973. The court found that CMS still

had not met the requirements of equal protection and ordered it to devise a new plan. 362

F. Supp. 1223 (1973). In April, 1974, the court disapproved the proposed plan and

directed CMS to develop a plan in cooperation with a volunteer Citizens Advisory Group

(“CAG”). {Swann, No. 1974, Slip Opinion at p. 3) (April 3, 1974). The court approved

the guidelines developed by CMS and CAG on “the express assumption and condition

that the board of education will constructively implement and follow” them. 379 F.Supp.

1102, 1103 (1974).

In July, 1975, noting that “continuing problems remained,” the court placed the

case on inactive status, emphasizing the “continuing effect” of its many orders. 67 F.R.D.

11

648, 649 (1975). The court also dismissed a lawsuit filed in 1973 by a group ot white

families challenging the continued use of race in student assignment. Cuthbertson v.

Charlotte Mecklenburg Bd. ofEduc., No. 1974, Slip Op. (1973). (See, Martin v.

Charlotte Mecklenburg Bd. OfEduc., 475 F.Supp. 1318, 1321 (1979) discussing

Cuthbertson.) This Court affirmed per curiam. 535 F.2d 1249 (4th Cir.), cert, denied,

429 U.S. 831 (1976).

In 1978, another group of white parents again challenged the Board’s assignment

plan as unconstitutional, Martin, supra. The Swann Plaintiffs intervened. The court

concluded that CMS had failed to abide by the order in: (1) siting of new schools;

(2) placing primary grades in black communities; (3) monitoring transfers; and

(4) placing unequal burdens on black students. Id., at 1328-40. The court also held that,

independent of its orders, CMS had the discretion to consider race when assigning

students to maintain desegregated schools. Id., at M45. This Court affirmed. 626 F.2d

1165 (4th Cir. 1980), cert, denied, 450 U.S. 1041 (1981).

In 1980 the court modified the Swann orders to permit operation of elementary

schools that were 50% or more black, but not more then 15% above the system average.

(No. 1974 slip op., April 17, 1980.)

In September 1997, William Capacchione, a white parent, filed suit challenging

the use of race in magnet school admissions. JA'I/69. The Swann Plaintiffs moved to

reopen Swann on the ground that CMS was not in compliance with the court orders, and

moved to consolidate the proceedings. JA/I/77. In March 1998, the court denied a Board

motion to dismiss Capacchione, reactivated Swann and consolidated the two cases,

finding that unitary status was the common question between them. JA/I/87. In April,

12

1998, another group of white parents intervened as plaintiffs in the consolidated action.

JA/I/125.

After a two month trial, the court issued judgment on September 9, 1999,

declaring the school system unitary in all respects, finding that the magnet school

admissions process was unconstitutional, and enjoining the Board, beginning in the

2000-01 school year, from “assigning children to schools or allocating educational

opportunities or benefits through race-based lotteries, preferences, set-asides or other

means that deny students an equal footing based on race.” 57 F.Supp.2d 228, 294

(W.D.N.C. 1999). JA/II/850.

Both the Swann Plaintiffs and CMS appealed. JA/III/968, 1272. The trial court

denied their stay requests. This Court granted both motions for a stay.

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS3

Before 1965, CMS operated a racially segregated school system. The original

1965 Swann action challenged an assignment plan that established racially segregated

neighborhood school zones and freedom of choice transfers. The district court upheld the

plan. 243 F.Supp. 667 (1965).

After the lawsuit CMS closed sixteen all-black or predominantly black schools.

. By 1968, when the Swann Plaintiffs filed a motion for further relief,

approximately two-thirds of the system's black students still attended all-black schools,

3 The facts are too lengthy to be set forth here in full detail. Additional facts

appear in the Argument section. References are made to the more detailed Proposed

Findings of Fact submitted by the Swann Plaintiffs and CMS. Important historical

findings are included in orders entered from 1969 through 1980.

13

staffed almost exclusively by black teachers. One-fourth of the white students attended

all-white schools and another third attended schools with negligible black enrollment.

300 F.Supp. 1358, 1360 (1969). The court found that CMS was operating an

unconstitutionally segregated school system. Id. at 1366.

The court ordered that CMS submit a plan for the effective desegregation of the

schools. Despite the closure of seven more black schools, the court accepted a

preliminary plan of desegregation to be completed by the fall of 1970. The court noted

the tremendous impact of segregation on the quality of education for children:

[Segregation in Mecklenburg County has produced its inevitable results in the

retarded educational achievement and capacity of segregated school children. It

cannot be explained solely in terms of cultural, racial or family background

without honestly facing the impact of segregation....... It is painfully apparent

that ‘quality education’ cannot live in a segregated school; segregation itself is the

greatest barrier to quality education.

306 F.Supp. 1291, 1296-1297 (emphasis in original). The court gave CMS wide

discretion to choose its methods, but cautioned that the plan should not “put the burden of

desegregation primarily upon one race.” Id.

In a series of orders over the next twelve months, the court became increasingly

critical of the Board’s failure to adopt an acceptable plan. See, Swann, 300 F.Supp. 1358,

1381 (W.D.N.C. 1969) (Board denies any duty to desegregate); and 306 F.Supp. 1291

(1969) (Board’s plan showed no likelihood or promise of integrating schools).

On February 5, 1970, the court found CMS again in default and approved a plan

developed largely by a court-appointed consultant. 311 F.Supp. 265 (1970). The court’s

plan provided that each school would have roughly the same ratio of black and white

faculty and students. The court further provided that the competence and experience of

14

teachers in formerly black schools should not be inferior to those in formerly white

schools; that CMS should prevent any school from becoming racially identifiable; that

transfers should be monitored to avoid segregation; and that CMS should have a

continuing program to maintain “each school and each faculty in a condition of

desegregation.” The court’s order met with much resistance by CMS and the white

community. Id. at 268-69.

The Supreme Court affirmed the district court. 402 U.S. 1 (1971). On the

“central” issue of student assignment, the court found racial ratios an appropriate starting

point, that one race schools should be closely scrutinized, that courts have authority to

draw remedial attendance zones, and courts could order transportation as a remedy. It

found age the most significant factor in that regard. Id. at 25-31.

Two years later, the trial court found that CMS policies and actions, such as the

use of mobile classrooms to expand enrollment in white areas and the failure to monitor

transfers, were causing resegregation. Schools with large black populations were labeled

inferior and became unstable without court intervention, and the affluent white

community was largely exempt from the desegregation orders. 362 F.Supp. 1223, 1237

(1973).

The court then approved the system’s plan in July 1974, but only upon condition

that it implement guidelines and policies developed in collaboration with a Citizens

Advisory Group. 379 F.Supp. 1102 at 1103-1104 (1974). The mandatory guidelines in

the 1974 plan included a student assignment proposal that made every school in the

system at least 20% black. (The district population was then approaching 35% black. SX

80, JA/XXII/10628). The guidelines required CMS to: adopt transfer policies that would

15

maintain and stabilize an integrated system; appropriately integrate its optional (now

magnet) schools; equitably distribute the burdens of busing; place primary' grades and

kindergartens in black communities; monitor trends in the racial composition of schools;

and plan school “location, construction and closing so as to simplify, rather than

complicate, desegregation.” 379 F.Supp., at 1103-04. Cognizant that continuing

problems remained”, the court expected that CMS would implement these guidelines and

placed the case on inactive status in July, 1975. 67 F.R.D. 648, 649.

In 1979, the court found in the Martin case that CMS had failed to implement the

1974 guidelines and policies in four specific areas: (1) location of new schools; (2)

placement of kindergarten and primary grades in black communities; (3) monitoring

transfer policies; and (4) alleviating the unequal burdens placed on black students. The

court found each of these areas “interrelated with and not separable from” student

assignment. Martin, supra at 1328-35.

The Board’s failure to comply has continued throughout the 1980’s and 1990’s,

CMS sought to implement some new policies in 1992 to remedy these failures. These

changes actually exacerbated these defects, leaving a gaping hole in the Board’s plan of

desegregation and preventing CMS from achieving a stable and fair program of student

assignment.

Racial Imbalance in CMS

The Board’s failure to implement the 1974 guidelines has been a major factor in

the increase in racially identifiable schools. The standard set by the court in 1980 for

identifying racially identifiable schools is the system-wide black ratio plus 15% points for

elementary schools, Swann, No. 1974, Slip Op. W.D.N.C. April 17, 1980), and greater

16

than 50% for secondary schools. 328 F.Supp. at 349. The original Swann court

expressed concern about identifiably white schools. At trial the Swann Plaintiffs urged

the court to adopt a minus 15% lower limit which was consistent with the 1974 plan.

Using the original guidelines for identifying black schools and a minus 15%

standard for identifying white schools, the number of racially identifiable regular schools

in CMS has risen from four in 1978-79, to thirty in 1991-92 and forty-two in 1998-99.

DX 47, JA/XXVII/13095; DX 291, JA/XXXI/15431 .

Under this standard, CMS operated approximately one-third of its regular schools,

attended by over 33,000 students in 1998-99, as racially ldentiiiable. Several nominally

“balanced” schools in fact contain two or more independent programs, which, when

considered separately, are racially identifiable. Stevens Report, pp. 9, 11, JA/XX/9577 -

79. When students in the racially identifiable regular schools, special schools and schools

comprised of segregated programs are totaled, over 39,000 students attended racially

identifiable schools or programs in the 1998-99 school y ear-approximately 40% o f the

district’s students. D X47, JA/XXVII/13095 - 13099; Foster Report, D X 5 at Att. C, pp.

43-47, JA/XXIII/11570 - 75; Defendants ’ Findings 81, p. 22, JA/II/529. The number

of black children attending a racially identifiable black school or a racially identifiable

segregated program exceeded 14,000 in 1998-99, representing over one-third of the black

students in CMS. Defendants’ Findings, 1fy_7 p. 22, JA/n/529. Thus, in 1998-99, there

are virtually the same number of black students attending racially identifiable black

schools as in 1969. See Swann, 300 F.Supp. 1358 at 1360 (1969).

School Siting.

The total enrollment of black students in CMS increased over twenty years at a

17

marginally greater rate overall than that of whites. Nonetheless, CMS continued to build

schools in white neighborhoods and transport black students to those schools, placing an

ever-increasing burden of transportation upon black students. Twenty-eight schools have

been built in the district since 1980. Becoates, T. 5/21, JA/XII/5838; DX 253, 266,

JA/XXXI/15404, 15415. Twenty five of these schools are located in predominantly

white areas; two are located in integrated areas; and only one, a magnet, is located in a

predominantly black area. Becoates, 5/21, JA/XII/5838; Foster, T. 6/9, JA/XV/7418.

Approximately two-thirds of these new schools either were desegregated by using

black satellites (12 of 27) (Foster, 6/9, JA/XV/7422, or opened as racially identifiable

schools (9 of 27), Id..,. 7419. McAlpine and McKee Road Elementary Schools, for

example, were built in white residential areas in Southeast Charlotte, placing a huge

transportation burden on the black children who were “satellited"’ to those schools (i.e.

bused from non-contiguous attendance zones). When satellites were discontinued

following implementation of the magnet program in the 1990’s, those schools became

95% white. D X 47, JA/XXVII/13096. Newer schools at Elizabeth Lane and Hawks

Ridge Elementary Schools are also more than 95% white. As a result of these

construction and siting practices, there are 7,000 more elementary students than available

seats in the black central city. Becoates 5/20, JA/XII/5816.

Not only did CMS fail to follow the court’s siting guidelines; it failed to follow its

own policy. In 1992, CMS adopted a resolution that schools should not be located in

census areas with less than a 10% black population. DX 66, JA/XXVII/13249; Wallace,

5/18, JA/XI/5332 - 33; Griffin 6/18 at 119, JA/XVIII/8982. That policy has not been

followed by CMS. DX 110, JA/XXVIII/13719; Wallace, 5/18, JA/XI/5332 - 33; DX

18

188, JA/XXIX/14498; Becomes, 5/20, JA/XII/5811 - 14.

These decisions also influenced racial residential development patterns in the

county, encouraging growth in the predominantly white southern area o f the county and

the predominantly white far northern area of the county. DX 99, JA/XXVII/13503;

Trent, 5/27, JA/XIII/6902; S. Smith, 5/17, JA/XI/5121 (building permits after McKee

announcement); Norman, 5/17, JA/X/4971 - 73 (residential development after McAlpine

announcement).

Transportation Burden.

The Board’s siting decisions and the de-painng of schools under the magnet

expansion increased the transportation burden which has continued to fall heaviest upon

black students.

At the time of the Martin decision, there were few if any kindergarten and

primary grades in predominantly black areas, so the youngest black students were bused

out of their neighborhoods to distant white neighborhoods. Throughout the 1980’s and

90’s, CMS continued to locate K-3 schools in white communities and build new schools

in predominantly white suburbs. The system’s desegregation strategies moved from

pairings to satellite attendance zones, increasing the transportation burden on black

children, particularly the youngest. Stevenson, 5/12, JA/IX/4410; Houk, 5/14,

JA/X/4776; Schiller, 5/3, JA/VIII/3867; Armor, 4/29, JA/VIII/3586 - 87. By the 1998-

99 school year, one-race satellites had become the predominant desegregation tool.

Ninety-one percent of the satellite areas (63 of 69) and ninety-one percent of the students

assigned to satellites (14,957 of 16,409) were from predominantly black neighborhoods.

JA/XXIII/11512 - 11516 (Table 7). For many black students, this meant satelliting for

19

their entire school career.

The burden borne by black children was widely known and sometimes openly

discussed. Mr. Calvin Wallace, a Regional Assistant Superintendent, acknowledged that

senior staff and Board members commented that younger black students could be bused

for a longer period than their white counterparts in the suburbs because the black children

were more “street-wise.” Wallace, 5/18, JA/XI/5283 - 85.

Absence of Kindergarten and Primary Grades in Black Communities.

The 1974 guidelines called for the immediate placement of kindergarten and

primary grades in black communities. Yet no kindergarten-or primary grade outside of

the magnet program has been placed in inner city black communities since the Martin

order.

CMS’s strategies of de-pairing and satelliting while locating schools in outlying

white areas disregarded the clear requirement of the 1974 order that kindergarten and

primary grades be placed in black communities. Even though there was an increase in the

black school age population in the predominantly black communities, CMS responded to

that growth by creating satellite attendance zones in the inner city and transporting

students from these zones to the white schools in outlying areas. These policies and

practices must be contrasted with the manner in which CMS responded to growth in

white areas. CMS has used mobile classrooms extensively at the nearly all-white McKee

Road Elementary School and South Charlotte Middle Schools, DX-265, JA/XXXI/15414,

to expand capacity rather than assign these students to nearby underutilized integrated

schools.

20

Failure To Monitor Transfers.

CMS failed to monitor the racial composition of students transferring out of

predominantly black non-magnet schools to magnet programs. This failure has led to an

increased segregation in the sending schools. See, e.g., Stevens Report, discussing

segregative effects o f transfers on non-magnets, JA/XX/9584 - 88. The number of

students in segregated schools increased about 50% system-wide and 200% at the high

school level from 1991-92 to 1998-99. Stevens Report, p. 21. Id., at 9589. The racial

pattern in the transfers is stark: the “blacker” the school, the higher the number of whites

transferring out to magnets. See, Swann Plaintiffs ’ Proposed Findings, %282 with Table

showing percentage o f whites leaving each Middle and High School. JA/I/435.

This failure of CMS to monitor transfers, primarily in the magnet program, was

not limited to a negative impact on the racial balance of the schools where whites

transferred out. It had the addi tional impact of depriving those schools of student leaders

and active parents. This resulted in schools having inferior academic programs with

fewer course offerings, lower test scores and much higher teacher turnover. In short, not

only did the racial makeup of the schools suffer, the academic program of the schools

suffered as well.

Demographics

The dramatic increase in the number of racially identifiable schools cannot be

attributed to demographics alone. Growth trends in the county have been fairly consistent

from the 1960’s through the present. Lord 6/11 at 7 - 9, 127-128, JA/XVI/7765 - 67,

7785 - 7787. The central area of the city has been predominantly black throughout this

period, although its population density has declined over time. Lord 6/11, JAlid., 7788,

21

7888 - 89. The county’s other areas have remained predominantly white. Lord 6/11,

JAlid., 7780 - 82, 7786. The percentage of black residents in Mecklenburg County has

stayed almost constant, increasing only two percent from 24% to 26% from 1976 to 1996.

Lord Report, p. 2. JA/XXV/12108. The percentage of black students in CMS has

changed only slightly, from 38% to 42% since the late 1970’s. Since 1970, Mecklenburg

County has become more residentially integrated. The dissimilarity index, which

measures the degree of racial segregation, dropped from .75 in 1970 to .59 in 1990, the

last census date for which the index could be computed. Expert demographers for both

the Plaintiff Intervenors and the defendants each testified that the reduction in the level of

residential segregation in Mecklenburg County should make the schools easier to

desegregate. Clark 4/19, JA/IV/1585; Lord 6/11, JA/XVI/7786; 7789 - 90; 7888.

Demographics simply cannot account for the dramatic increase in racially identifiable

schools at a time when residential patterns have become more desegregated.

After all is said and done, practices and policies of CMS have been a significant

contributing factor in creating a school system which continues to be defined by race.

22

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I. The judgment below declaring the Charlotte-Mecklenburg School System

unitary is legally and factually flawed. The evidence shows that over the past twenty

five years CMS has failed to comply with four explicit directives in the desegregation

orders in this case which the original trial court found were interrelated with and

inseparable from the constitutional process of student assignment. The court below

makes four distinct legal errors in finding that CMS had complied with these outstanding

orders, including an erroneous depiction of the nature and import of the 1979 proceedings

in Martin, two misreadings of prior orders about the overcrowding of predominately

white schools and the burdens of transportation, and an invalid presumption that CMS

properly took white flight into account in its assignment plans.

These initial legal errors led the court into two additional errors of law. The court

failed to analyze the contributing impact upon increasing segregation in pupil assignment

of the system’s noncompliance, attributing all of those ills to demographic change. That

error led the court to abrogate its duty in a unitary status case to consider the

practicability of other desegregation methods available to remedy persistent vestiges of

segregation in student assignment. This combination of legal errors requires reversal of

the court’s judgment as to student assignment.

The court also errs in its analysis of resources and facilities, shifting of the burden

of proof away from the party seeking unitary status, and requiring the Swann Plaintiffs to

prove that present intentional discrimination caused current disparities in resources. This

legal error stems from a misreading of the prior Swann orders and of the law governing

the allocation of the burden of proof in school desegregation cases. Under a proper

23

analysis, there was substantial evidence at trial about persistent vestiges of segregation in

this area.

As to faculty assignment, the court erred both in the standard it selected for

assessing faculty balance and in omitting any discussion of the evidence on faculty

assignments for 1998-99. The data omitted from the opinion shows that one-third of

CMS schools had racially identifiable faculty, and that predominately black schools had

more than twice as many probationary and first-year teachers as did predominately white

schools.

II. The court below ignored the law of this case in concluding that the

constitutional infirmity of the system’s use of race in assigning pupils to its magnet

school programs was the violation of the white Intervenors’ rights.

III. This error as to the constitutionality of the magnet program led the court to

impose an unlawful, wide-ranging injunction prohibiting CMS from taking race into

account in any fashion in the future operation of the schools, when that issue was not

litigated at trial, was not ripe for determination, and was contrary' to the law of this case

and of this circuit.

ARGUMENT

I. STANDARD OF REVIEW.

The order under review presents the threshold issue of whether CMS has obtained

“unitary status,” a determination reached by assessing various aspects of school

operations first identified in Green v. County School Board o f New Kent County, 391

U.S. 430 (1968). Ordinarily unitary status is a fact driven inquiry where the “clearly

erroneous” standard applies. Vaughns v. Bd. OfEduc. O f Prince George’s Co., 758 F.2d

983 (4th Cir. 1985). However, the factual determinations in the opinion below turn on

critical legal suppositions that present questions c f law for this Court to review de novo.

In re Brice, 188 F.3d 576, 577 (4th Cir. 1999). The legal issues include: (1) interpreting

the prior orders of the case, (2) allocating the burden of proof and (3) determining what

conditions constitute vestiges of segregation.

The fundamental inquiry in a unitary status hearing is whether a school system

has complied with the prior orders of the court. Board o f Education v. Dowell, 498 U.S.

237 (1991); Freeman v. Pitts, 503 U.S. 467 (1992). Any factual determination of

compliance with prior orders is also a question of law which depends on a correct legal

interpretation of those orders. The allocation of the burden of proof is also a legal

question. The trial court correctly noted that the Intervenors have the burden of proof on

the unitary ̂status issue as the party moving to dissolve the Swann orders. 57 F.Supp.2d

at 243. The court reduced the Intervenor’s burden, however, and on the Green factor of

resources and facilities, shifted it to the Board and Swann Plaintiffs. This lowering and

shifting of the burden of proof are legal issues on review. Finally, a court in a unitary

status hearing must consider whether a school system has eliminated the vestiges of

25

segregation to the extent practicable. Dowell, Freeman. Thus, these three legal issues are

reviewed de novo. To the extent that the Swann plaintiffs challenge discrete factual

findings below, these challenges are reviewed under the clearly erroneous standard.

The remaining issues, whether the court erred in finding that CMS had violated

the constitutional rights o f the Intervenors, and whether the court had the authority to

enter its sweeping injunction, are issues of law subject to de novo review. Brice, supra.

II. THE DISTRICT COURT MADE NUMEROUS SIGNIFICANT ERRORS

OF LAW IN FINDING UNITARY STATUS.

A school desegregation decree seeks to convert a segregated school system into a

“unitary system in which racial discrimination (is) eliminated root and branch.” Green,

391 U.S. at 437-38. To determine whether a school system has attained “unitary'” status,

a court looks at various facets o f its operation to determine whether the school district has

complied fully with the prior orders of the court, eliminated the vestiges of segregation to

the extent practicable, and shown to the group previously discriminated against its

commitment to following the constitution. Freeman v. Pitts, 503 U.S. at 492 (1992). 4

4 In its discussion regarding the confidence of black citizens in future actions of

the School Board, absent court supervision, the trial court concluded that there “has been

no evidence of racial animus or discriminatory intent in any School Board actions during

the thirty years that CMS has been under court order.” 57 F.Supp. 228, 283. This is a

clearly erroneous finding given the repeated findings by the original Swann court of

unconstitutional and continuing discrimination from 1969 through 1979. In light of this

carte-blanche absolution of the Board’s previously determined unconstitutional conduct,

this Court should scrutinize the decision below with extreme care.

26

This trial court’s consideration of the Green factors is factually and legally

erroneous. The court makes distinct, fundamental errors o f law interpreting prior orders

and case authority that infect its whole analysis of student assignment. The court engages

in unprecedented burden shifting in the review of resources and facilities and in effect

assumes that CMS had attained unitary status on this factor thirty years ago. Finally, in

assessing faculty assignment and the ancillary issue of student achievement, the court

ignores critical evidence.

A. CMS HAS NOT ELIMINATED THE VESTIGES OF

DISCRIMINATION IN STUDENT ASSIGNMENT.

Assessing compliance with the prior student assignment orders in the case, the

court erroneously focused on the levels of racial balance in the schools without

addressing the express finding of the trial court in 1979 - a time when its schools were

nearly 100% balanced racially - that CMS was not in compliance with the prior Swann

orders or the constitution regarding assignment of black students.

The 1979 Martin order sets out four specific student assignment compliance areas

that CMS had to remedy to become unitary: (1) siting school facilities in locations that

facilitated desegregation; (2) immediately placing early primary grades in black

neighborhoods; (3) monitoring transfers to prevent resegregation; and (4) equitably

distributing the burdens of transportation. 475 F.Supp. 129-140. The Martin court found

these four areas interrelated with and inseparable from the process of student assignment.

Any assessment of compliance with prior desegregation orders must take into account

M artin’s express findings of non-compliance. The number of schools in balance is

neither the sole nor dispositive issue.

27

The court minimized the Martin order by stating that it must be read “in context,”

a “context” mistakenly premised on four unsupportable statements of law, 57 F.Supp.2d

at 250. The court declared first that Martin is not significant because it is not about

unitary status. Then, in finding that CMS has complied with Martin, the court twice

misread prior Swann orders - concluding that they never found equal protection concerns

in the overcrowding of white schools or the inequitable burdens of transportation.

Finally, the court erroneously determined that while CMS was under court order to

desegregate, it properly considered white flight when planning school siting and student

assignment. This last assertion, while containing a correct finding of fact as to the

unlawful dynamic that has led to increased segregation in CMS, concluded with an

egregious misstatement of the law regarding white flight. These four legal errors led to

further errors in the court’s analysis of demographics, where the court failed to recognize

that the policies flowing from the Board’s non-compliance with Martin have contributed

significantly to the present imbalances in the schools. The court’s mistakes regarding

Martin also led it to err as a matter of law in refusing to consider the practicability of

other desegregation methods to address persistent and growing vestiges of segregation in

student assignment.

1. The Martin Trial Involved Unitary Status.

The court downplayed M artin’s relevance by asserting that it “was not a unitary

status hearing.” Id. While making this assertion, the court ignored the following:

(a) the Martin plaintiffs alleged specifically in their complaint that CMS had been

“unitary” since adopting the 1974 plan and that the Board could no longer consider race

28

in assigning students; (b) the Swann Plaintiffs intervened in the case and presented

“exhibits and lengthy testimony” that CMS was not unitary because it had not complied

with prior orders; and (c) the Swann judge heard the evidence, “re-examined and

considered hundreds of pages of findings of facts and orders” from his original Swann

orders and concluded that CMS had yet to comply. 475 F.Supp. 1321-22.

While Martin may not technically have been designated a “unitary status

hearing,” the evidence in that case focused on unitary status. The Swann plaintiffs

argued, and the court concluded, that CMS had not complied with Swann ’s orders. The

court then set out the specific steps CMS had to take on student assignment to comply

with Swann and obtain unitary status. The court’s assertion that Martin is inapposite

because it did not involve unitary status is erroneous; Martin provides the very

framework for the unitary status determination.

2. Overcrowding Was A Constitutional Concern.

The court made two legal errors in asserting that CMS has complied with any

requirements of Martin regarding selection of school sites. First, the court misread the

prior orders in finding that the overcrowding of white schools was never a constitutional

concern in Swann. The court declared, for example, that using mobile classrooms to

over-enroll predominately white schools like McKee and South Charlotte was considered

a practical problem under the prior orders, not a constitutional issue. To support the

assertion, the court cited an October 1970 memorandum order appended to a 1971 Swann

decision. 57 F.Supp. 2d at 252, citing 334 F.Supp at 631. However, the actual 1971 order

expressly held that the court would “scrutinize” under the constitution the use of mobile

classrooms to expand enrollment at white schools, and declare the policy unlawful if it

29

“causes or restores segregation.” 334 F.Supp at 626-27. The court’s next Swann order

declared just that: the use of mobile classrooms to increase accommodations at white

schools was unlawfully discriminatory and a basis for requiring the Board to present a

new student assignment plan for 1974. 363 F.Supp. at 1233.

Not only did the court below misread Swann, but it also failed to recognize that

the Supreme Court in 1973 affirmed a similar finding about mobile classrooms in Keyes

v. School Dist. No. 1, Denver, 413 US 189, 201 (1973). Clearly this practice had

constitutional dimensions. The trial court’s failure to explicate the prior Swann orders

and a Supreme Court decision on point presents clear legal error in its analysis.

3. Consideration of White Flight In Siting Decisions Was

Unlawful.

The court made a second error in finding that the Board had complied with Martin

in siting schools. Touching one of the core dynamics in this litigation, the court found

correctly that CMS had weighed concerns about white flight in planning where to site its

schools, a practice the court deemed proper and lawful. 55 F.Supp.2d at 253. While

factually accurate, the legal analysis is fundamentally wrong.

The court cited Riddick v. School Bd. o f Norfolk, 784 F.2d 521, 528-29 (4th Cir.

1986), an important case in unitary status jurisprudence, for the proposition that a school

system under a desegregation order may consider white flight. However, Riddick holds

just the opposite: a school board under court order cannot consider white flight in

meeting the court’s orders.

The Riddick decision examined a finding that white flight had been considered in

the Norfolk, Virginia school system. The issue arose in a trial heard some nine years

30

a fter the declaration of unitary status. Approving the consideration of white flight in that

case, this Court explained the important difference between a system under court order

and one that already had been declared unitary. When a school system is under a

desegregation order, as is CMS, “white flight cannot be used as a reason for failing” to

comply with a desegregation order. Id. at 528 (quoting, United States v. Scotland Neck

Bd. o f Educ., 407 U.S. 484 (1972))(emphasis added). A school system not under court

order, on the other hand, may consider white flight. Id. at 529.

The trial court’s finding that CMS could consider white flight to justify its lack of

compliance with Martin and the Swann orders was a fundamental legal error. That error

cannot be a basis for finding compliance on student assignment. Rather, the finding that

CMS considered white flight establishes a failure to comply with its court ordered

obligations.

4. Transportation Is A Constitutional Concern.

The court made a fourth error of law in its effort to reconcile its view of M artin’s

requirement to balance transportation burdens with the enormous transportation burden

now placed on black students. As with the overcrowding issue, the court inappropriately

cites early Swann orders that suggested transportation burdens were a practical problem

and not an equal protection concern. 57 F.Supp.2d at 253, citing 328 F.Supp. at 1349

(1971) and 334 F.Supp. at 626 (1971). The court ignored later Swann orders that found

the transportation burdens on black children, particularly the youngest, to be “continuing

discrimination” by CMS that violated black students’ rights to equal protection. 362

F.Supp. at 1232. It disregarded the 1974 order that no child be satellited for all twelve

years of school (a practice now occurring) and that “[o]ut-busing assignments are to be

31

distributed as equally as possible and practical.” 379 F.Supp., at 1106. The court also

failed to note the finding in 1979 that the unequal transportation burdens had not yet been

addressed, in violation of the prior orders and the federal constitution. 475 F.Supp. 1338-

40. Finally, it did not acknowledge that a number of black children are satellited for all

thirteen years of their education, and that 91% of the satellites are in black

neighborhoods, Foster Report, JA/XXIII/11512 - 11516 (“Table 7”). Ignoring these

relevant facts, it concluded that “the current situation may be about the best CMS can

do.” 57 F.Supp.2d at 253.

5. The Trial Court Wrongfully Minimized The Burden Of Proof

And Made Clearly Erroneous Factual Findings As To Siting.

In addition to its explicit legal errors, the court reduced the Intervenors’ burden of

proof, finding that Martin must be viewed “in a new light” because of the passage of

time. 57 F.Supp.2d at 250. The court set out a series of “facts” that ameliorate the

Board’s siting decisions, though these facts have limited value in proving compliance

with the specific orders under which CMS was required to operate.

The court determined that the Board has considered diversity in selecting sites,

since most of the schools it has built have been integrated. Id., at 251-52. This assertion

begs the question. These new schools have been integrated by one-way busing of black

students to schools in white areas - a practice specifically condemned in prior orders.

While the court also found that the Board adopted a rule in the early 1990’s to site new

schools only in areas that are at least 10% black, it recognizes that this resolution was

never followed. Id. The court found that 22 stand-alone schools have been “created.” Id.

Only one of these schools (Hornet’s Nest) has been built since 1980, however, and nine

32

of the first ten supposedly “stand-alone” schools actually had satellites assigned to them.

SX21, JA/XXI/10069. The court further found that satelliting white students into black

areas would be impractical because of rush hour traffic, while ignoring the fact that

thousands of white magnet students travel daily in this traffic pattern.

Finally, the court erroneously faulted the Swann Plaintiffs for not intervening in

these siting decisions, claiming they “were the subject of public hearings, televised

meetings, and ballot referenda.” 57 F.Supp.2d at 253. In fact, the decisions to purchase

real estate for school construction are the most guarded and secret decisions that the

Board makes, partly to protect itself in negotiations for sites. All of the meeting minutes

about land-purchase decisions are from closed sessions, not the public sessions imagined

by the court.

6. The Evidence At Trial On The Four Martin Requirements

Demonstrates That CMS Has Not Remedied Continuing

Effects Of The Prior De Jure Segregation,

The Intervenors failed to offer evidence that the Board met the four requirements

addressed in Martin. The Swann Plaintiffs and CMS tendered evidence showing that the

four areas which were a necessary component of the student assignment issue had not

been remedied.

a. School Siting and Transportation. The evidence shows that after Swann

and Martin, the siting of schools continued to impede integration and put heavier burdens

on black students. From 1980 to 1998, black student enrollment grew by 12,000, white

enrollment by some 8,000. The Board responded to this growth by building almost all of

its new schools in white neighborhoods, and then transporting black students to those

schools. See, e.g. Lassiter, 4/20, JA/IV/1963 — 65. The Board built only one school (a

33

magnet) in a black census area out of 28 schools built after 1980. D X 266,

JA/XXXI/15415. As a result of these siting decisions and the de-pairing o f schools, the

transportation burden continues to fall heavily upon black students.

The magnet expansion as implemented by the Board worsened the transportation

problem that the CMS magnet consultant had identified in 1992 and sought to remedy

with his plan. D X 108, JA/XXVIII/13599. The number of black neighborhoods

satellited one-way to schools in white areas rose dramatically in the 1990’s with the de

pairing of schools under the magnet expansion. Though magnets finally brought some

primary grades to the black community, a far greater number of black students, not

accepted into the available magnet seats, went into mandatory assignments areas, or

satellites, and were bused to the formerly paired white schools. D X 262-64,

JA/XXXI/15411 - 13. These black students attended a satellite school until completion

of the terminal grade there, a far more unbalanced burden than existed previously. By the

1998-99 school year, one-way satellites had become the predominant desegregation tool:

91% of the satellite areas and 91% of the students assigned to satellites'' were from

predominantly black neighborhoods. Foster Report, Table 7, JA/XXIII/11512 - 11516.

DX. 262-264. JA/XXXI/15411 - 13. Of the 3,317 non-black students satellited to school

in 1998-99, only 1,199 lived in the six majority white satellite areas. Thus, almost two-

thirds of the non-black students bused mandatorily are transported because they live in a

5 Calculated from Foster’s table 7 by dividing the total number of students in

predominantly black satellite areas by the total number of students in all satellites. The

numbers have increased from 1994-95, when 87% of the satellite areas, and 88.5% of the

satellited students, were in black neighborhoods.

predominantly black neighborhood. This pattern is occurring in a system that has been

under court direction to balance the transportation burden for over twenty years. For

many black students, it means a satellite education for their entire school career, a

practice the 1974 order expressly prohibited. 379 F.Supp. at 1106, Guideline VI.

b. Location of Earliest Primary Grades. The Intervenors did not contest

that the Board has not located regular (non-magnet) early primary grades in a black area

since Martin, another failure to comply with the 1974 order. 379 F.Supp. at 1106

(Guideline VII); 475 F.Supp. at 1339. This failure has placed the burden of

transportation on the very youngest black students in CMS, a violation of the prior orders

and a concern of the Supreme Court in its Swann decision. 402 U.S. 1,31 (no

consideration more important than age of students); 362 F.Supp. at 1232 (“virtually all of

thq youngest black children” bused out of their neighborhoods); 475 F.Supp. 1338-40.

In contrast to extensive one-way satellites from black areas, CMS has used mobile

classrooms to significantly expand the capacity of the nearly all-white McKee

Elementary and South Charlotte Middle School, though seats are empty in reasonably

proximate schools with significant black populations.6 D X 265, JA/XXXI/15414.

Suggestions to reassign some of these students to under-utilized schools have been

abandoned, not because they are impractical, but because they are politically unfeasible

because of white parent objection.

6 The driving time from some parts of these assignment zones to the other schools

with empty seats is not significantly longer than the travel time to McKee or South

Charlotte. Beacoates, 5/21, JA/XII/5851.

35

c. Monitoring Transfers. Finally, the evidence at trial showed that the

Board has not monitored magnet program transfers to avoid resegregation. Transfers

from black non-magnet schools to the magnet has systematically increased segregation in

those sending schools. See, e.g., Stevens Report, JA/XX/9584 - 88; Swann Findings

^282, JA/I/435. Overall, the number of students in segregated schools increased 50%

system-wide, and 200% in the high schools from 1991-92 to 1998-99. Stevens Report, p.

21. 1 JA/XX/9589 The racial pattern in the transfers is obvious. D X 57,

JA/XXVII/13165 - 93; Swann Plaintiffs 'Proposed Findings, 11282 with Table. JA/I/435.

At the middle school level in 1998-99, over 30% of the assigned white students

transferred to magnets from majority black middle schools. Id. Since the expansion of

magnets in 1992-93, the percentage of black students at Ranson Middle School has risen

from 44% to 65%. D X 47, JA/XXVII/13098. That change can be attributed to the

transfer to magnets in 1998-99 by some 59% of the non-black students assigned to

Ranson (443 students). D X 5 7, J A/XXVII/13188. Similarly, 40% of the non-black

students at Wilson Middle School transferred to magnets in 1998-99. Id., at 13189. Like

Ranson, its black population has risen 20% in the six years of the magnet expansion, from

7 The court clearly misunderstood testimony about segregation within the magnet

programs, confusing it with the arguments of other witnesses about tracking. See, 57

F.Supp.2d at 247 (“Stevens attacked the practice o f ability grouping.”) Stevens analyzed

not tracking, but the phenomenon that a magnet school site might appear racially

balanced, though it actually contains two or more independent segregated magnet

programs. Such schools are not balanced racially, but are separate, racially imbalanced

schools at one site. Stevens included students enrolled in the racially imbalanced magnet

programs with those attending racially imbalanced schools to calculate properly a

percentage of students in a segregated setting. See, Stevens Report, JA/XX/9576 - 77, -

79. That data did not consider tracking within school programs.

36

51% to 71%. D X 47, JA/XXVII/13099; Swann Plaintiffs ' Proposed Findings, JA/I/425,

222 .

At the four high schools that are at least 50% black, over one-fourth of the

assigned non-black students transferred out to magnets in 1998-99, with 43% transferring

from West Charlotte. Black enrollment at West Charlotte has risen 20% in five years to

68% in 1998-99. D X 47, JA/XXVII/13099. In contrast, the rate of transfer at the

remaining eight high schools with smaller black student populations was markedly lower,

from 6% to 9% at six schools, and from 10% to 12% at the two others. Swann Plaintiffs ’

Proposed Findings, *^282(Table), JA/I/435.

This exodus of white students has had a debilitating impact on identifiably black

schools, drawing away high achieving students and active parents with financial

resources and leaving these schools academically inferior, with fewer course offerings,

meager PTA resources, lower standardized test scores, and dramatically higher teacher

turnover. Cockerham, 5/26, JA/XIII/6460 - 6469; McMillan, 5/17, JA/XI/5164 - 51S6.

Steven Smith Report, Appendix C, SACS Reports, JA/XX/9653 - 9662. Because of its

impact on these “losing” schools, the Board’s failure to monitor transfers into magnets

also violates the 1973 order holding that practices and policies that produce or restore

segregation, or have the effect of labeling a school as “inferior,” are discriminatory and

must be corrected. 362 F.Supp. 1237. The practices of CMS do both and have yet to be

corrected.

The trial court summarily found that transfers from magnets had not “wrecked

havoc” or resulted in “significant jeopardy” to the court ordered desegregation plan.

This assertion is clearly erroneous, for its only support is an unsubstantiated speculation

37

in a single CMS document that more schools may have become segregated in the absence

of the magnet plan. Likewise, the court’s only support for the finding that CMS had

monitored transfers was the testimony of a CMS expert that a now retired CMS

employee had told him she “kept an eye on [magnet transfers] so there wouldn’t be a run

on the bank so to speak from any one school.” 57 F.Supp. 2d at 249, n. 23. The record

shows that the expert was not relying on this assertion but expressing incredulity at this

claim in the face of the statistical evidence on the segregative impact of magnet transfers.

Foster, June 9, JA/XV/7438. While the court found that this single hearsay statement

satisfied the Interveners' burden of proving compliance with the order to monitor

transfers, the court dismissed as “anecdotal” and legally insufficient the testimony from

numerous witnesses about the racial disparities in school resources and facilities within

CMS. 57 F.Supp.2d at 263.

7. The Failure To Properly And Adequately Address Martin Fatally

Impacts The Court’s Analysis Of Student Assignment.

a. Level of Compliance. The court set a +/- 15% standard which it found

that CMS had met in most of its schools over time, despite recent declines. It ultimately

concluded that the system’s level of compliance compared favorably with other districts

that had been declared unitar}'.

Mere calculations of compliance with a +/- 15% racial balance to decide unitary

status is misplaced. In the late 1970’s, CMS schools were nearly 100% statistically

compliant with the court’s orders, more so by far than today. Yet, the Swann court found

in 1979 that CMS was not in compliance with its orders or the constitution. It is thus the

“law of the case” that CMS had not complied with the court’s orders in 1979.

Nonetheless, the court below considered the number of schools within its less stringent

standard to be “remarkable.” 57 F.Supp.2d at 248. The court did not explain how it turns

present resegregation into compliance or how it can ignore the prior findings of non-

compliance by the judge who entered the substantive orders in Swann.

Other shortcomings in the court’s emphasis on statistics include its comparison of

CMS’s “racial imbalance index” with other school districts in the county. 57 F.Supp.2d at

248 {citing Armor report, p. 7 Table 1, JA/XXXIII/16173). The court’s reliance on the

Armor table is an insufficient basis for unitary status. The table does not disclose the

origin of the data, state which of the systems are under court order, or disclose residential

imbalance indices or other facts specific to those communities. Further, there is no

national standard for unitary status based on a comparison of this racial imbalance index.

The Armor comparisons thus have little or no value for determining unitary' status.

Moreover, comparisons on another data set do not support the court’s conclusion.

For example, Dr. Armor’s Chart 3 is a graph of unitary school systems. Only one school

system on Chart 3 had a majority white population like CMS when it was declared

unitary. Armor Report, Chart 3, JA7XXXIII/16193. This school system, New Castle

County, Delaware, had 95% of its schools within +/- 10% of the system average when it

was declared unitary, a far higher level of compliance than found in CMS, where only

70% of the schools are within a +/- 15% range. Coalition to Save Our Children v. State

Bd. ofEduc ., 901 F.Supp 784, 797 (D. Del. 1995), a ff’d, 90 F.3d 752 (3rd Cir. 1996).

A more accurate comparison would be Hillsborough County, Florida, which

according to Dr. Clark, has statistics of compliance and demographic patterns very

39

similar to those in CMS. Clark, 4/19, p. 185. That system was declared not to be unitary

with regard to student assignment. Manning v. School Board, 24 F.Supp.2d 1277

(M.D.Fla. 1998).

b. Demographics. The errors regarding compliance with Martin also

create further errors of law in the court’s analysis of demographics. CMS was operating

under a desegregation order which it must comply with by eliminating the “roots” of

discrimination and eradicating its effects. Green, 391 U.S. at 437-38; Dayton Bd. o f

Educ. v. Brinbnan, 443 U.S. 526, 537 (1979); Swann, 402 U.S at 26. A school system

cannot be relieved of its legal obligations when its policies are “a contributing cause” of

the racial identifiability of its schools. Columbus Bd. o f Educ. v. Penick, 443 U.S. 449,

465, n.13 (1979); Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, Denver, 413 U.S. 189, 211 and n. 17

(1973); cited in, Freeman v. Pitts, 503 U.S. at 512, (Blackmun, concurring). The court

below found that demographic change was the primary cause of the increasing number of

imbalanced schools, and thus the school system was not legally responsible for the

growing imbalances. 57 F.Supp.2d 249-50. Had the court properly analyzed the orders

in Martin, it would have recognized that CMS’s non-compliance with Martin is a

significant “contributing cause” of the imbalances.

The role of CMS policies is plainly demonstrated by the 50% increase over a five

year period in the number of black students in segregated schools under the 1992 policy

of student assignment, and the exodus of white students from black schools under the

magnet program. Demographic change is not the sole or even the primary explanation

for these trends. The Board’s decision to de-pair schools and move to magnets is the

major cause of this increased imbalance.

40

The court also overstated the extent of racial demographic change. Charlotte has

grown, but its racial composition has remained almost constant, with a material decrease

in the overall level of residential segregation. The court points to the difficulty of

desegregating the most extreme suburbs, whose census areas are 95% white, without

noting that in 1973 the school population in the entire southeastern half o f the county,

containing far more census areas, was over 91% white. 362 F.Supp. at 1232, 1239 (map).

Schools located in center-city areas where no racial change occurred are now

imbalanced only as a result of changes in board policy. Druid Hills Elementary is in a

neighborhood that has remained more than 95% black since the 1969 court orders. Clark

Report, Table 5, JA/XXXIII/16253. The court’s assertion that it would be all black

without a magnet is simply wrong; it was a racially balanced school until 1993-94, D X

47, JA/XXV11/13095 the year before the current magnet program was implemented.

Comparison of Charlotte’s demographic changes with those described as

“overwhelming” and “fundamental” in Freeman demonstrates Charlotte’s stability. See,

Freeman, 503 US at 475, 76. Black enrollment in DeKalb climbed from 5% to near 50%

in some twelve years, due to migration of black families into the southern half of the

county, Id. at 475, leading to a polar residential segregation in the county and

challenging desegregation efforts in the schools. Id. In contrast, black school enrollment

in Charlotte Mecklenburg has increased only 4% in 19 years. (1980-1998). DX47,

JAy XXVII/'13095 - 99. As noted by all three demographers, the major trend in CMS

residential demographics has not been the polarization seen in DeKalb, but integration of

the increased black population into the suburbs. Clark, JA/XXXIII/16232, -38, -51;

Shelley, JA/XX/ 9680-81, -85, -86; Lord Reports, JA/XXV/12105, 12112 - 12115, 12120

41

-2 1 , 12144. This has caused the residential index of racial dissimilarity in CMS to

decline from .75 in 1970 to .59 in 1990. Dr. Clark, the Intervenors demographer,

admitted that a system like CMS with a declining dissimilarity index would be easier, not

more difficult, to desegregate overtime. Clark, 4/19, JA/IV/1672 - 73. In all pertinent

aspects, the demographic pattern in Charlotte is the opposite of that described in

Freeman.

The court also ignored evidence of the Board’s contribution to residential growth

patterns. The courts have long cautioned about the impact of school siting decisions on

housing patterns. Swann, 402 U.S. at 20-21. The record shows that the Board’s siting

decisions have spurred development in the very areas the court identifies as 95% white.

Immediately after the Board voted to build a school at what is now McAlpine

Elementary, three major affluent developments were announced in the previously

undeveloped area. T. Norman, 5/17, JA/X/4971 - 73. The school is 4% black. D X 47,

JA/XXVII/13096. Similarly, when the Board voted, over the objections of black board

members, to build McKee Elementary, 141 housing permit applications were filed for the

then undeveloped area within a month. Stephen Smith, 5/17, JA/XI/5121. The school is

now 2% black and overcrowded with mobile classrooms.

Finally, the court ignored its own finding about considerations of “white flight.”

A very real reason the Board is operating overwhelmingly white schools in suburban

areas is the political pressure put on the Board to keep poorer black students out of those

schools. See, Eric Smith, 6/8, JA/XV/7164 - 66; Eric Becoates, 5/21, JA/XII/5892 - 99;

Pam Mange, 5/17, JA/X/4992 - 4997. As noted above, the court erroneously approved

the consideration of white flight in the planning process contrary to this court’s holding in

42

Riddick v. School Bd. o f Norfolk, supra.

The court’s failure to apply the law of the case and the law of this circuit results in

another error of law. Demography simply is not the sole or primary cause of racial

imbalances and related problems in CMS. The court erred both in ignoring the

“contributing cause” of Board policies in the increasing segregation in student assignment

and in absolving the Board from legal responsibility for its violations of the desegregation

orders.

8. The Court Erred By Failing To Evaluate The Efficacy of the

Board’s Desegregation Strategies.

In a unitary status analysis, a court should determine whether a school system has

eliminated the vestiges of segregation to the extent “practicable.” See, Freeman, 503

U.S. at 479-501. The court below declined to make this analysis on the ground that it

had no authority to order further remedies in the case. This refusal to consider the

practical effort of alternative desegregation strategies emanates from the court’s

misinterpretation of Martin and from its flawed analysis of the Board’s contribution to

the present imbalances in student assignment.

The court reasoned that it could not remedy the growing imbalances within CMS

because, though still under court order, CMS had broken the link with de jure segregation

and had no further obligation to fix racial imbalances in its schools. 57 F.Supp.2d 255.

The court did not pinpoint the point in time when CMS broke this link and fulfilled its

legal objective, because it cannot. Plainly, CMS has not fulfilled the requirement of

Swann and Martin to adopt equitable methods of balancing its schools. Instead of

recognizing this noncompliance and considering practicable alternatives for compliance,

43

the court erroneously adopted a variant of the Intervenors’ legal theory that CMS was de

facto unitary. The court thus held that CMS had no further obligation to follow the

court’s previous orders above before CMS has been released from these orders. This is

contrary to Dowell, which made clear that legal obligations remain until there is a

declaration of unitary status. 498 U.S. 237, 246. See, also, United States v. State o f

Georgia, Troup County, 171 F.3d. 1344 (11th Cir. 1999). That declaration comes only

after a court has examined all of the Green factors, and any other factors the court

chooses to consider. Troup County, Id., at 1347.

This reasoning turns the unitary status analysis inside out. The court claimed

inability to consider a required element in assessing unitary status because it determined

that CMS has fulfilled its legal obligations and is already unitary. Yet CMS cannot be

declared unitary until the court has determined it has desegregated student assignment to