Clark v. Board of Education of the Little Rock School District Court Opinion

Public Court Documents

May 13, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Clark v. Board of Education of the Little Rock School District Court Opinion, 1970. 73abb69e-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/11b22fbc-25d7-43e5-ba81-ad950186ed97/clark-v-board-of-education-of-the-little-rock-school-district-court-opinion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

No. 19,795.

Delores Clark, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

The Board of Education of the

Little Rock School District, et al.,

Appellees.

No. 19,810.

Appeals from the

United States Dis-

„ trict Court for the

Eastern District of

Arkansas.

Delores Clark, et al.,

Appellees,

v.

The Board of Education of the

Little Rock School District, et al.,

Appellants.

[May 13, 1970.]

Before V an O o sterh o u t , Chief Judge; M a t t h e s , B l a c k -

m u n , G ibso n , L a y , H e a n e y and B r ig h t , Circuit Judges,

En Banc.*

* Judge Mehaffy took no part in the consideration or decision of

these appeals.

Matthes, Circuit Judge.

This appeal and cross-appeal from the judgment of the

United States District Court for the Eastern District of

Arkansas (the late and lamented Gordon E. Young) causes

us again to consider whether the efforts of the Board of

Education of the Little Rock, Arkansas, School District

(hereinafter referred to as District or Board) to desegre

gate its schools satisfy the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment as interpreted in Brown v. Board

of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) (Brown I) and subse

quent decisions of the Supreme Court which have deline

ated the principles enunciated therein.

The process of desegregation in this District has been

controversial and its long history is recorded in the deci

sions cited in the margin.1 While we focus our attention

on the events from 1966 to the present, it is necessary to

briefly sketch the background against which these events

are set. Up until 1954 and Brown I, the District, pursuant

to state law, operated separate educational facilities for

black and white children. After much turmoil, and the

passage of several years, students were assigned to schools

according to the dictates of the Arkansas pupil placement

statute. When this practice was found to contravene the

Fourteenth Amendment,2 a “ freedom of choice’ ’ plan was

adopted. In Clark v. Board of Education, 369 F.2d 661

1 Aaron v. Cooper, 143 F.Supp. 855 (E.D. Ark. 1956), aff’d 243 F.2d

361 (8th Cir. 1957); Aaron v. Cooper, 2 Race Rel. L. Rep. 934-36, 938-41

(E.D. Ark. 1957), aff’d Thomason v. Cooper, 254 F.2d 808 (8th Cir. 1958);

Aaron v. Cooper, 156 F.Supp. 220 (E.D. Ark. 1957), aff’d sub nom, Faubus

v. United States, 254 F.2d 797 (8th Cir. 1958); Aaron v. Cooper, 163

F.Supp. 13 (E.D. Ark.) rev’d 257 F.2d 33 (8th Cir.), aff’d sub nom.

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) ; Aaron v. Cooper, 26'1 F.2d 97 (8th

Cir. 1958); Aaron v. Cooper, 169 F.Supp. 325 (E.D. Ark. 1959); Aaron

v. McKinley, 173 F.Supp. 944 (E.D. Ark. 1959), aff’d sub nom, Faubus v.

Aaron, 361 U.S. 197 (1959); Aaron v. Tucker, 186 F.Supp. 913 (E.D.

Ark. 1960) rev’d Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F.2d 798 (8th Cir. 1961); Clark

v. Board of Education of Little Rock, 369 F.2d 661 (8th Cir. 1966),

2 Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F.2d 798 (8th Cir. 1961).

(1966), we sanctioned “ freedom of choice” in principle

but found the District’s plan to be deficient in failing to

provide adequate notice to the students and their parents

and to provide a definite plan of staff desegregation. We

remanded and directed the district court to retain juris

diction to insure adoption and operation of a constitutional

plan for the full desegregation of the Little Rock schools.

In August of 1966, four months prior to our decision in

Clark, the Board apparently recognizing the inadequacy

of its existing mode of desegregation, employed a team of

experts from the University of Oregon to make a study

of the system and prepare a master plan of desegregation.

The team submitted its recommendations, the “ Oregon

Report,” in early 1967. In brief, the recommendations

called for abandonment of the neighborhood school con

cept and the development of an educational park system8

through the institution of a capital building program and

the pairing of schools. The cost of implementing the

Oregon plan was estimated to be in excess of ten million

dollars. In the November 1967 school board election at

least one of the incumbent members of the Board who

supported the ‘ ‘ Oregon Report’ ’ was defeated and replaced

by a candidate who opposed the report. The election re

sults were interpreted as a public rejection of the “ Oregon

Report,” and it was subsequently abandoned by the Board.

Still searching for a solution, the Board directed Floyd

W. Parsons, Superintendent of Schools, and his staff to

prepare a comprehensive plan for desegregation of the 3

3 The educational park concept, as applied to the Little Rock District,

called for a single attendance zone coextensive with the school district

boundaries. One high school was to be established drawing students

from the entire District. Similarly, fewer middle schools and elementary

schools would be operated, and those operated would be concentrated

near the center of the District. Some pairing was contemplated at the

elementary level. Obviously, implementation of such a plan would neces

sitate transportation of some students from their homes to the schools.

4

schools. Acting accordingly, this group submitted a pro

posal known as the “ Parsons Plan.” The plan provided

for desegregation of the high schools and two groups of

grade schools. It made no provision for the junior high

schools. The high schools were to be desegregated by

“ strip-zoning” the District geographically, generally from

east to west so as to form three attendance zones for the

high school students. The Horace Mann High School, an

all Negro school, was to abolished and utilized as an

elementary facility, and additions were to be made to two

of the three remaining high schools. The two groups of

elementary schools were to be desegregated by pairing of

schools within each group.4

The cost of implementing the “ Parsons Plan” was esti

mated at five million dollars,5 and a bond issue for that

amount was submitted to the voters in March of 1968.

Despite active campaigning by Superintendent Parsons

and several Board members, the bond issue was decisively

defeated, as were two incumbent members of the Board

who supported the plan. Thus, as of March, 1968, the

District, although recognizing the inadequacies of the exist

ing means of desegregation, had been unable to develop

and implement an acceptable alternative. And, students

were assigned for the 1968-69 school year according to

‘ ‘ f reedom-of-choice. ’ ’

4 The “Parsons Plan” called for the creation of two floating zones—

the Alpha Complex in the northeastern corner of the District and the

Beta Complex in the south central portion of the District. Within these

two complexes there existed a number of elementary schools, some of

which were predominantly black and others predominantly white. Under

Mr. Parsons’ plan these elementary schools would be paired in order to

achieve a “reasonable racial ratio” in each of the schools. Some re

modeling of existing facilities was contemplated in implementing the

two complexes.

5 However, less than 40% of this sum was directly related to achieving

desegregation. The remaining 60% of the cost arose from needs of the

system apart from efforts to desegregate.

On June 25, 1968, plaintiffs moved the district court for

further relief.6 The court responded by setting a hearing

for August 15, 1968, and, by letter of July 18, 1968, sug

gested to the Board that it devise a geographic zoning

plan to correct student segregation. The Board was also

admonished to devise a plan for faulty desegregation so

that the racial division of the faculty in each school would

approximate the racial breakdown of the faculty in the

entire District. At the August 15th hearing the District

presented an “ interim” zoning plan which was admittedly

incomplete and required more study, and requested that

the “ freedom of choice” method of pupil placement be

retained for the 1968-69 school year. After the second day

of testimony, the hearing was recessed to enable the Dis

trict to formulate a final plan for the disestablishment of

racial segregation to become effective at the beginning of

the 1969-70 school year. Before recessing, the court re

affirmed its earlier suggestion concerning faculty desegre

gation and stated unequivocally that “ freedom of choice”

as applied to the Little Rock schools would not satisfy the

constitutional requirements. The Board was directed to

file its plan not later than November 15, 1968.

During the Board’s deliberations two plans were sub

mitted for its consideration and rejected. A group of

Negro citizens offered the “ Walker Plan,” so designated

because John Walker, counsel for plaintiffs, was a moving

force in its formulation. The “ Walker Plan” contem

plated grade restructuring and pairing of schools through

out the District and at all grade levels. Substantial trans

portation of students would have been necessary to

implement the plan. The Board also considered and re-

6 Several parties sought to interevene. A group of Negro children

by their parents, were permitted to intervene as parties plaintiff The

Little Rock Classroom Teachers Association was also permitted to inter

vene.

— 6 —

jected a proposal offered by two of its members calling

for retention of “ freedom of choice” plus the reservation

of space at predominantly white schools for Negro children

desiring to attend them. The Board finally adopted, with

two members dissenting, a plan for pupil assignment based

on geographic attendance zones.

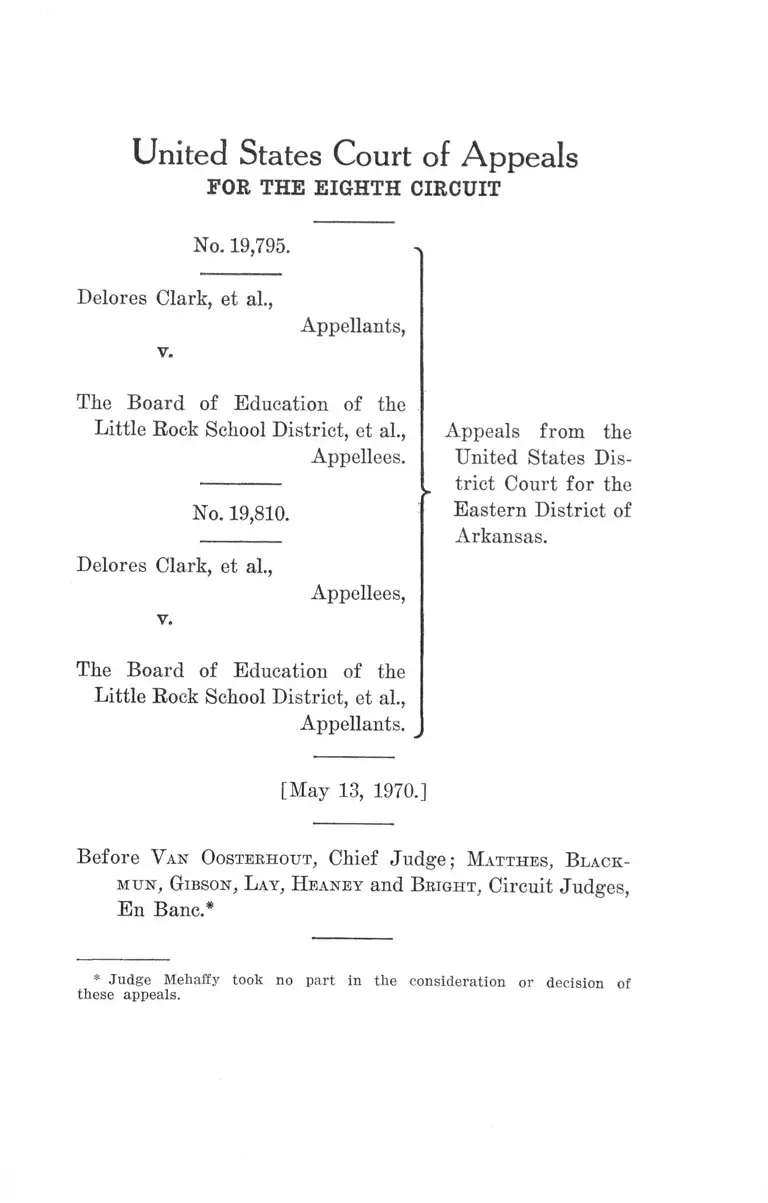

Attached to this opinion is a reduced reproduction of

defendants’ Exhibit 22 depicting the geographic zones pro

posed, and designating the location of elementary, junior

high and high school buildings. The elementary zones are

defined by fine lines and the junior high zones by broad

lines. On the original exhibit the high school zones are

identified by four different colors. Because we were unable

to reproduce the colors, we have highlighted the high

school zone boundaries by a crossed line, and have appro

priately designated the several colors of the original ex

hibit. Except for this alteration, the map is an exact re

production of the original exhibit.

As illustrated by the map, the Little Rock School Dis

trict is an irregular rectangle running from east to west.

Natural boundaries on the north and south and the com

mercial and industrial nature of the eastern portion have

caused the city to expand toward the west. Generally

speaking the eastern one-half of the District is inhabited

predominantly by Negro citizens and the western one-half

predominantly by white citizens.

At the beginning of the 1969-70 school year there were

24,248 students in the system; 15,027 white and 9,221

Negro. They attended five high schools, seven junior high

schools, and thirty-one elementary schools throughout the

District.

Under the District’s plan, all students were to attend

schools serving their grade level in their zone of residence

— 7 —

except: (1) students attending Metropolitan High School,7

(2) students in the 8th, 10th and 11th grades in 1969-70,

who were permitted to choose between the school in their

zone and the school they had previously attended8 9 and (3)

children of teachers in the District, who could attend the

school where their parents were employed. The proposal

for faculty desegregation complied with the suggestion

of Judge Young. It called for the assignment of teachers

so that the percentage of Negro teachers in each school

ranged from a maximum of 45% to a minimum of 15%.

Pursuant to the court’s direction at the conclusion of the

August 16 hearing, the District submitted the plan now

under consideration. On December 19, the hearing was

resumed and additional evidence was introduced. On May

16, 1969, the district court filed its unreported opinion.

While approving the District’s plan in principle, the court

amended it by: (1) redrawing the Hall High School zone

to include approximately 80 additional Negro children;

(2) establishing a “ Beta Complex” ;0 (3) providing for

majority to minority transfer of students.10

Both parties have appealed from the district court’s

judgment.

A brief summary of the contentions urged upon us will

suffice. Plaintiffs submit that the geographical zones as

7 Metropolitan High School is a vocational school which serves the

entire District. No segregation exists as to this facility. ........ .

8 This departure from geographical attendance zones was an effort to

minimize disturbance of the extra-curricular patterns established by

students in these grades.

9 The court adopted in part Mr. Parsons’ concept calling for the pair

ing of certain elementary schools within a floating zone. See note 4 supra.

10 This provision of the court’s modification permitted students at

tending schools in which their race was in the majority to transfer to

schools in which their race rvas in the minority, subject to the availability

of space in the transferee school.

drawn merely serve to perpetuate the previously estab

lished segregated attendance patterns of the students in the

District. Neither the neighborhood school concept nor the

possible necessity of busing, according to plaintiffs, ex

cuses the District’s failure to achieve a unitary system

devoid of racially identifiable schools. Lastly, they argue

that the faculty assignment approved by the district

court continues to preserve the racial identity of certain

schools.11

Conversely, the District is of the firm conviction that

the plan that it submitted to the district court is constitu

tionally faultless. It reasons that the geographical zones

were drawn without regard to race, and that, as such, the

plan established a unitary system within the constitutional

requirements. It is further asserted that the constitution

does not require transportation of children outside the

area of their residence in order to achieve racial balance

in the schools, and indeed the assignment of pupils ac

cording to race would itself be a violation of the Four

teenth Amendment. According to the District, the neigh

borhood school concept is educationally sound, and, in

view of community attitudes, the only feasible means of

operating the Little Rock system.

On cross-appeal the District objects to the district

court’s departure from the geographical zoning scheme it

submitted. It is argued that the gerrymandering of the

Hall zone to include more Negro students and the ma

jority to minority transfer provision are violative of the

Fourteenth Amendment since they require racial distinc

tions to be made. A similar objection is made to the

“ Beta Complex.”

11 Plaintiffs also assert that the district court erred in refusing to

allow them attorney fees.

— 9 —

THE FACULTY

For the 1969-70 school year there were 1053 teachers

employed by the District—29% Negro and 71% white.

Under the plan adopted by the District and approved by

the district court, the percentage of Negro teachers in each

of the schools varies from 14% to 50%.12 Plaintiffs com

plain that even under the approved plan there is a general

pattern throughout the system whereby schools with a

high proportion of Negro students (“ Negro schools” )

have a higher percentage of Negro teachers. They argue

that this pattern tends to reinforce the racial identity of

those schools.

Just as schools may be racially identified by the makeup

of their student body, so may they be identified by the

character of their faculty, and school boards are obligated

to correct any previous patterns of discriminatory teacher

assignment. One means of correcting such patterns is to

assign teachers so that the ratio of Negro teachers to

white teachers in each school approximates the ratio for

the District as a whole. United States v. Montgomery

County Board of Education, 395 U.8. 225 (1969); Yar

brough v. Hulbert— West Memphis School District, 380

F.2d 962 (8th Cir. 1967). However, the ultimate goal is the

assignment of teachers solely on the basis of educationally

significant factors, wherein race in and of itself is irrele

vant.

The plan adopted by the District provides for the non-

discriminatory assignment of teachers and affirmative steps

to correct the existing imbalance. The experts agreed that

the District’s plan was ambitious, and in fact some doubt

12 The district court judge, on the basis of projected figures thought

the percentages would range from 15% to 45%. Because of resignations

attrition, etc. these figures proved slightly incorrect.

— 10

was expressed as to whether it could be carried out. How

ever, to a remarkable degree it has been implemented, and

its implementation has radically changed the complexion

of faculties throughout the district. Where before Negro

teachers were heavily concentrated in those schools long

identified as Negro, they are now distributed throughout

the District so that no school has more than 50% Negro

teachers. Indeed, and particularly at the elementary level,

in most of the schools the percentage of Negro teachers

in any particular facility varies only slightly from the

percentage of Negro teachers in the District as a whole.

Therefore, we affirm the district court’s approval of the

District’s plan with respect to faculty.13 See Kemp v.

Beasley, . . . F.2d . . . (8th Cir. 1970) (Kemp III). The

plan as implemented has corrected the exaggerated racial

imbalance of teachers in the system. Faculty desegrega

tion through teacher assignment is a dynamic process. The

District has committed itself to the non-discriminatory as

signment of teachers and the correction of previous segre

gation, and has for the 1969-70 school year evidenced its

good faith in fulfilling these commitments. We are con

fident that any remaining vestiges of faculty segregation

will be corrected by the District’s continuing efforts.

STUDENTS

After deliberate consideration, we are driven to the con

clusion that the proposal for student desegregation does

not comport with the recent pronouncements of the Su

13 Compare the order of Judge Johnson in Carr v. Montgomery County

Board of Education, 289 F.S'upp. 647 (M.D. Ala. 1968). In a district

where the faculty ratio was 3 to 2, the order required that in the coming

school year only 1 of every 6' members of each school’s faculty be from

the race which was in the minority in that particular faculty." This was

approved in United States v. Montgomery County Board of Education

395 U.S. 225 (1969).

11

preme Court, hence it must he rejected. We hasten to

add, however, that significant progress has been made by

the District. For example, Central High School, the scene

of so much turmoil in 1956, is now desegregated—1,542

white, 512 Negro. So too are several other previously all

black or all-white schools. However, as we recognized in

Kemp 111, supra, the finding of some progress does not

end the inquiry whether the particular District has satis

fied its constitutional obligations.

It is, of course, axiomatic that the operation of separate

schools for black and white children under sanction of

state law is violative of the Fourteenth Amendment. As

the Court observed in Brown I, supra, in the field of educa

tion "separate facilities are inherently unequal.” And in

Brown II, 349 U.S. 294 (1955), school districts which had

previously operated "separate” schools were ordered to

take the necessary action to eradicate this constitutional

violation. The question now before us is whether the

District has fulfilled its constitutional obligation to convert

what admittedly was a segregated school system to a

"unitary system in which racial discrimination would be

eliminated root and branch.” Green v. County School

Board of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430, 438 (1968).

Principal guidance from the Supreme Court as to this

issue is to be found in the trilogy of cases decided in 1968.

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County, supra;

Raney v. Board of Education of Gould School District, 391

U.S. 443 (1968); Monroe v. Board of Commissioners of

City of Jackson, 391 U.S. 450 (1968). Each of the school

districts there involved had adopted "freedom of choice”

plans (or modifications thereof) for pupil assignment. In

general the "freedom of choice” plans under consideration

had not significantly altered attendance patterns which

— 12 —

had been established by pre-Brown I state segregation

laws. “ Negro schools” continued to be attended by Negro

students and “ white schools” by white students. For ex

ample, in Green 85% of the Negro children continued to

attend the all Negro school. Despite the School Board’s

contention in Green that it had “ fully discharged its obli

gation by adopting a plan by which every student, regard

less of race, may ‘ freely’ choose the school he will attend.”

391 U.S. at 437, the Court found that “ freedom of choice”

as applied to these three districts did not meet the com

stitutional requirements.

The thrust of all three opinions is that the manner in

which desegregation is to be achieved is subordinate to

the effectiveness of any particular method or methods of

achieving it. The following language is instructive:

“ The burden on a school board today is to come for

ward with a plan that promises realistically to work,

and promises realistically to work noiv.

The obligation of the district courts, as it always

has been, is to assess the effectiveness of a proposed

plan in achieving desegregation. There is no universal

answer to complex problems of desegregation; there

is obviously no one plan that will do the job in every

case. The matter must be assessed in light of the cir

cumstances present and the options available in each

instance. It is incumbent upon the school board to

establish that its proposed plan promises meaningful

and immediate progress toward disestablishing state-

imposed segregation. It is incumbent upon the district

court to weigh that claim in light of the facts at hand

and in light of any alternatives which may be shown

as feasible and more promising in their effective

ness . . . .

We do not hold that ‘ freedom of choice’ can have

no place in such a plan. We do not hold that a ‘ free

dom of choice’ plan might of itself be unconstitutional,

— 13 —

although that argument has been urged upon us.

Rather all we decide today is that in desegregating a

dual system a plan utilising ‘ freedom of choice’ is not

an end in itself.” 391 U.S. at 439-40. (emphasis in the

second and third paragraphs supplied).

More recent pronouncements by the Court are consistent

with this pragmatic approach. In Alexander v. Holmes

County Board of Education, 396 U.S. 19 (1969), the Court

ordered the “ immediate” termination of dual school sys

tems and the operation of “ unitary school systems within

which no person is to be effectively excluded from any

school because of race or color.” Id. at 20. (emphasis

supplied).

Review of desegregation decisions from this circuit re

veals that we too have tested proposed plans of desegre

gation by their effectiveness. For instance, ten years ago

we held that the Arkansas pupil placement statute, on its

face a non-discriminatory and educationally rational means

of pupil placement, could not be used to assign students,

if it failed to correct the segregated character of the sys

tem. Dove v. Parham, 282 F.2d 256 (8th Cir. I960).14 In

1968, prior to the Green trilogy, we were faced with a

“ freedom of choice” plan. Kemp v. Beasley, 389 F.2d 178

(8th Cir. 1968) (Kemp II). It too was asserted to be edu

cationally sound and devoid of racial considerations. How

ever, we tested “ freedom of choice” as applied in that

particular instance and found it lacking; not by viewing it

in the abstract, but rather by considering whether it ef

fectively advanced the desegregation process. Our analysis

in Kemp II was, of course, approved by the Green

trilogy.15 And, only very recently we again found “ free

dom of choice” to be constitutionally deficient in Kemp III,

14 See also, Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F.2d 798 (8th Cir. 1961).

15 Indeed Kemp II was cited with approval. 391 U.S. at 440.

supra. Although desegregation had been accomplished at

the high school level by pairing and the junior high level

by “ freedom of choice,” application of “ freedom of

choice” to the elementary grades left 5 of the 10 schools

racially identifiable. We ordered the District to take the

necessary steps to correct the segregated character of

those 5 elementary schools.

Thus, as of this date, it is not enough that a scheme for

the correction of state sanctioned school segregation is

non-discriminatory on its face and in theory. It must also

prove effective. As the Court observed in Green-.

“ In the context of the state imposed pattern of long

standing, the fact that in 1965 the Board opened the

doors of the former ‘ white’ school to Negro children

and of the ‘ Negro’ school to white children merely

begins, not ends, our inquiry whether the Board has

taken steps adequate to call for the dismantling of

a well-entrenched dual system.” 391 IJ. S. at 437.

We believe that geographic attendance zones, just as the

Arkansas pupil placement statutes, “ freedom of choice”

or any other means of pupil assignment must be tested by

this same standard.16 In certain instances geographic zon

ing may be a satisfactory means of desegregation. In

others it alone may be deficient. Always, however, it must

be implemented so as to promote desegregation rather

— 14 —

16 The Board’s reliance on language in Green for the proposition that

geographic zoning in and of itself is constitutionally mandated is mis

placed. In two places in the Green opinion the Court did refer to geo

graphic zoning as a possible alternative to “freedom of choice.” How

ever, it is clear when considered in context, that the Court was limiting

its suggestion to the Kent district, a district without residential segre

gation. Indeed footnote 6 quotes with approval a paragraph from the

concurring opinion in Bowman v. County School Board, 382 F.2d 326

(4th Cir. 1967), in which it is stated, “ . . . a geographical formula is

not universally appropriate.” Id. at 332. Any other reading of the

Green decision would be entirely inconsistent with the Court’s declara

tion that the ultimate test is effectiveness and many plans may or may

not prove effective in a particular instance. See also the footnote ap

pearing at 391 U.S. 460.

— 15 —

than to reinforce segregation. See United States v, In-

dianola Municipal Separate School District, 410 F.2d 626

(5th Cir. 1969) • Henry v. Clarlcsdale Municipal Separate

School District, 409 F.2d 682 (5th Cir. 1969); United

States v. Greenwood Municipal Separate School District,

406 F.2d 1086 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 395 U. S. 907 (1969).

When viewed in context of the above principles, the plan

approved by the district court is constitutionally infirm.

For a substantial number of Negro children in the Dis

trict, the assignment method merely serves to perpetuate

the attendance patterns which existed under state man

dated segregation, the pupil placement statute, and “ free

dom of choice” 17—all of which were declared unconstitu

tional as applied to the District. In short the geographical

zones as drawn tend to perpetuate rather than eliminate

segregation.18 Several examples are illustrative. During

the 1968-69 school year, under “ freedom of choice” Mann

High School, located in the eastern portion of Little Rock

and historically an all Negro school, was attended by all

Negroes. In this school year it is attended by 838 Negroes

and 4 whites. Parkview High and Hall High, historically

white schools,19 have 45 Negro and 793 white and 40 Negro

and 1,415 white students, respectively. Prior to this year

both Booker Junior High20 and Dunbar Junior High21

17 Under "freedom of choice” in 1968-69 approximately 75% of the

Negro students attended schools in which their race constituted 90% or

more of the student body. The plan adopted by the district court re

duces this percentage by only 6%.

18 It was agreed by all the experts that zone lines for the District

would have to be drawn from east to west if previously established at

tendance patterns were to be broken.

19 Both of these schools were constructed after 1956.

20 This school, named after a prominent Negro, was constructed in

1963. Only Negro children were assigned to it and it was staffed by

Negro teachers.

21 Prior to 1954, Dunbar was the Negro junior high school for the

District.

— 16

were all Negro. Now they are attended by 733 Negro and

20 white and 685 Negro and 18 white students, respec

tively. Two junior high schools located in the western por

tion of the city are attended by similar proportions of

students with white students predominating. At the ele

mentary level, Carver, Gillam, Granite Mountain, Ish,

Pfeifer, Rightsell, Stephens, and Washington all have 95%

or more Negro students.22 In a number of other elementary

schools the reverse is true. All of the foregoing schools

are racially identifiable.

While it is true that the majority to minority transfer

provision has the potential for alleviating the situation to

an extent, it is in large part an illusory remedy. No trans

portation is provided for those children choosing to take

advantage of it. And, it requires little insight to recognize

that the children who are most likely to desire transfer

are those least able to afford their own transportation.

Moreover, there is no assurance that space will be avail

able in the schools to which most of the transfers would

probably occur.23

Alternative means of pupil assignment which would pro

vide more effective desegregation were and are available

to the District. Indeed, several such means were embodied

in plans submitted to and considered by the Board. We

point this out not as an endorsement of any particular

22 Carver, Granite Mountain, Pfeifer, and Washington were operated

as “Negro schools” under state-imposed segregation. Rightsell was con

verted to a “Negro school” in 1961. Gillam and Ish, named after promi

nent Negroes and located in Negro neighborhoods, were constructed in

1963 and 1965, respectively. They were staffed by Negroes and have

always been attended almost solely by Negro students.

23 Compare the transfer provision adopted in Ellis v. Board of Public

Instruction of Orange County, . . . F.2d . . . (5th Cir. Feb. 17, 1970),

which provided transportation for children choosing to transfer and in

sured that space would be available in the transferee schools.

— 17 —

plan, but merely to emphasize that alternatives are avail

able. Of particular significance is the “ Parsons Plan,”

which was developed by a group of educators closely af

filiated with the District and presumably quite sensitive

to the educational needs and problems of the community.

It was long ranged and comprehensive. If implemented, it

would have cured the isolation of Mann High School as a

Negro facility. The “ Parsons Plan” also would have

erased the racial identity of several elementary schools

which exists under the plan now before us. It enjoyed the

support of the Board and the professional staff of the

system.

Because of community opposition to the plan, as mani

fested in the defeat of a millage increase necessary to

finance its implementation, the “ Parsons Plan” was not

adopted. Similarly, community opposition was a substan

tial factor in rejection of other promising plans. We are

not unmindful of the difficult nature of the Board’s duties

in this District.24 However, it has long been the law of the

land that community opposition to the process of desegre

gation cannot serve to prevent vindication of constitutional

rights. Monroe v. Board of Commissioners of the City of

Jackson, supra; Aaron v. Cooper, 358 U.S. 1 (1958); Jack-

son v. Marvell School District No. 22, 416 F.2d 380 (8th

Cir. 1969). Accordingly, we are not at this time prepared

to hold that the geographical zoning plan adopted by the

lower court is the only “ feasible” means of assigning-

pupils to facilities in the Little Rock School System. Green

v. County Board of Education of New Kent County, 391

U.S. at 439.

24 Aaron v. Cooper, 257 F.2d 33, 39 (1958).

— 18 —

GROSS-APPEAL

By way of cross-appeal defendants challenge those pro

visions of the district court’s order departing from the

geographical zoning plan submitted by the Board. Since

we have found the plan adopted by the district court to be

deficient in the aforementioned particulars thereby requir

ing remand for adoption of an entirely new plan, defend

ants’ objections become somewhat academic. Nevertheless,

we briefly address ourselves to the contention that any

consideration of race in the placement of pupils is a

violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

This argument is not new and has been previously heard

and rejected by this court. Kemp II, 389 F.2d at 187-88.

See also United States v. Jefferson County Board of Edu

cation, 372 F.2d 836, 876-78 (5th Cir. 1966); Wanner v.

County School Board, 357 F.2d 452, 454-55 (4th Cir. 1966);

Fiss, Racial Imbalance in the Public Schools: The Con

stitutional Concepts, 78 Harv. L. Rev. 564, 577-78 (1965).

As the Wanner court observed it would be somewhat

anomolous to prevent correction of previous segregation

under the guise that the remedy impermissibly classifies

by race. Accordingly, we are not persuaded by defendants’

contention that the Fourteenth Amendment prohibits the

drawing of geographic zones to promote desegregation,

the majority to minority transfer plan, or any other con

sideration of race for the purpose of correcting uncon-

stutionally imposed segregated education.

REMEDY

This court has long recognized that it should not en

deavor to devise a plan of desegregation for any school

district. Kemp III, supra; Yarbrough v. Hulbert— West

— 19 —

Memphis School District, supra; Clark v. Board of Educa

tion of Little Bock, supra; Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F.2d 14

(8th Cir. 1965); Aaron v. Cooper, 257 F.2d 33 (8th

Cir. 1958). This task is basically within the province

of the school board under the supervision of the district

court. We continue to adhere to this philosophy. In light

of the size and complexity of the Little Eock School Dis

trict it is additionally important that the Board be af

forded ample opportunity to formulate a comprehensive

plan of desegregation. Nor do we believe it proper to

direct the Board to adopt a particular means of school

desegregation. As was observed in Green v. County Board

of Education of New Kent County, supra, there are a

variety of methods of desegregation, and no particular

method is universally appropriate. Considering the unique

problems facing the District any one of several different

methods, or a combination thereof, may be deemed ap

propriate. We leave this decision to the school board and

the sound discretion of the district court. We do, how

ever, strongly suggest that the Board consider enlisting

the services of the Department of Health, Education and

Welfare in developing an acceptable scheme of deseg

regation.

Consistent with these above views we consider several

questions either implicitly or explicitly raised in the

parties’ briefs and oral arguments.

As in Kemp III, supra, we do not hold that precise

racial balance must be achieved in each of the several

schools in the District in order for there to be a “ unitary

system” within the meaning of the constitution. Nor do

we hold that geographical zoning or the neighborhood

school concept are in and of themselves either constitu

tionally required or forbidden. See Kemp III. We merely

— 20 —

hold that as employed in the plan now before us they do

not satisfy the constitutional obligations of the District.

By so holding we express no opinion as to the relative

merits or demerits of the neighborhood school.

Lastly, we do not rule that busing is either required or

forbidden. As Judge Blackmun stated in Kemp 11I, “ Bus

ing is only one possibe tool in the implementation of uni

tary schools. Busing may or may not be a useful factor in

the required and forthcoming solution of the . . . prob

lem which the District faces.” . . . F.2d . . . . We obeserve

in passing, however, that busing is not an alien practice

in the state of Arkansas or this District. Some busing was

employed by the District in the past to preserve segre

gated schools. Presently the District, through the use of

federal funds, aids some children in eastern Little Bock

who use public transportation to travel to schools, and

some private busing occurs in the western portion of the

city. Of course, busing of school children is a common

practice in many less urban areas of the state and is par

tially subsidized with state funds.

The case is remanded to the district court with direc

tions to require the school district to file in the district

court on or before a date designated by it a plan consistent

with this opinion for the operation of the system “ within

which no person is to be effectively excluded from any

school because of race or color.” Alexander v. Holmes

County Board of Education, 396 TT.S. at 20. The plan shall

be fully implemented and become effective no later than

the beginning of the 1970-71 school year. The district court

shall retain jurisdiction to assure that the plan approved

by it is fully executed.

Because of the urgency of formulating and approving

an appropriate plan, our mandate shall issue forthwith

— 21 —

and will not be stayed pending petitions for rehearing or

certiorari.

Costs are allowed to plaintiffs. On remand the question

of attorney fees may again be presented to the district

court.

V a n O o stebh o u t , Chief Judge, and G ibson , Circuit Judge,

dissenting in part.

Judge Matthes’ carefully prepared majority opinion

fairly sets out the pertinent facts and issues presented by

the appeal and cross-appeal in this case. We are in agree

ment with his determination that the plan should be ap

proved as to the faculty desegregation, and also with his

affirmance on the cross-appeal. Wre likewise agree that

the court properly retained jurisdiction of the case.

With reluctance, we find it necessary to dissent from the

holding of the majority that the plan for student desegre

gation should be rejected. The late Judge Young, a very

able and conscientious judge, heard this case. He advised

the Board that the existing freedom of choice plan, which

was being fairly administered, did not meet standards for

desegregation set by the Supreme Court and he directed

the Board to present a geographical zoning plan. After

much study, the Board presented such a plan. An exten

sive evidentiary hearing was held at which school experts

testified on behalf of each of the parties. The cause was

well tried by able counsel for all parties. In due course,

Judge Young filed a well-considered opinion setting forth

the law, the evidence and his conclusions. Included in his

findings of fact is the following:

“ As shown by Defendants’ Exhibit 22, the Board’s

plan for geographical attendance zones, assuming the

— 22

legality of the neighborhood school concept, seems

fairly and equitably drawn. There is no indication of

gerrymandering. ’ ’

Such finding is not contested by plaintiffs. It is supported

by substantial evidence and is not clearly erroneous.

Judge Young modified the plan in the manner set forth

in the majority opinion. The principal effect of the modifi

cation was to impose upon the geographical zoning a

freedom of choice option which would allow any student

whose race was in the majority in any school to transfer

to a school where his race was in the minority. As stated

by Judge Young, this modification would permit Negro

students who would otherwise be locked into predominantly

Negro schools to transfer to predominantly white schools.

Other modifications made, which Judge Young conceded

were gerrymandering, were designed to further racial bal

ance in the schools. The Board’s plan as modified was

approved. The court in its decree retained jurisdiction

over the case and required the Board to report further

upon the operation of the plan.

For the reasons assigned by Judge Young in his well-

considered opinion, we believe the modified plan as ap

proved meets constitutional standards. Everything has

been done that could be done short of abandonment of the

neighborhood school system to eliminate segregation. Plain

tiffs have pointed to no existing state law that prevents

desegregation or integration and we find no such law. It

can no longer be fairly said that the desegregation process

is impeded by state law.

Geographic attendance zones fairly laid out without

racial discrimination by a unitary system should meet

the constitutional standards set forth in Brown I and sub

— 23

sequent Supreme Court cases commanding a racially non-

discriminatory school system. There is no question here

of dual attendance zones or of a state imposed pattern of

segregation.

The neighborhood school concept, as shown by expert

testimony in the record, is a well-established and accept

able means of providing a proper educational program

in all sections of the country for people of all nationalities

and races. President Nixon in a recent public statement

has said neighborhood schools “ will be deemed the most

appropriate base” for an acceptable school system, and

“ transportation of pupils beyond normal geographical

school zones for the purpose of achieving racial balance

will not be required.” 1

The basic issue presented on this appeal appears to be

whether upon the facts disclosed by the record a fairly

established geographical zoning system for neighborhood

schools must be abolished in order to attain racial balance

and if so, whether such balance in each school must closely

approach the percentage of each race in the district.

It would appear from the record before us that such

racial balance could only be accomplished by pairing white

and Negro districts, a considerable distance from each

other. On this issue, Judge Young states:

l The Gallup poll published in many papers on April 5, 1970, includes

the following conclusions:

“By the lopsided margin of eight to one, parents vote in opposition

to busing, which has been proposed as a means of achieving racial

balance in the nation’s classrooms.

“Opposition to busing arises not from racial animosity but from

the belief that children should attend neighborhood schools and

that busing would mean higher taxes. This is seen from a compari

son of attitudes on busing with those on mixed schools.

* * * * *

“When Negro parents are asked the same series of questions, the

weight of sentiment is found to be against busing.”

24 —

“ [T]he plaintiffs attack the neighborhood school prin

ciple, saying it has no validity and that the geographic

attendance zones should run lengthwise the District.

This, as they admit, would involve compulsory trans

portation of students by bus for distances at least six

to eight miles. This is so because the schools in the

central part of the City, including Central High, are

largely integrated, and the great disparity between

the races exists in the extreme eastern and western

parts. Therefore, transportation of pupils would con

sist largely of transportation from the extreme east-to-

west and vice versa, traversing the crowded traffic

conditions of the middle section, including the down

town district. Thus, high school pupils from Horace

Mann in the east would have to be transported past

Central to Hall High in the west, or vice versa. The

same would be true in a lesser degree with the junior

high and elementary schools.”

The District Courts and the Courts of Appeals are

divided upon the constitutional validity of retaining geo

graphical school zones fairly drawn without discrimina

tion. Such issue can only be authoritatively answered by

the Supreme Court. While broad language in some of the

Court’s opinions could arguably be subject to an inter

pretation that some degree of racial balance is required,

it is our view that the Supreme Court has not decided this

issue. See Chief Justice Burger’s concurring opinion in

Northcross v. Board of Education, . . . H.S. . . . (March 9,

1970).

The exhibits in the record reflect that in northern states

as well as in the south, the Negro population is frequently

concentrated in certain geographical areas and that as a

result in many northern metropolitan areas some neighbor

hood schools serve predominantly only Negro students.

Absent state law forcing segregation, as is the situation

__9,5__ _------ *j O ------

here, we see no racial discrimination or violation of equal

protection. The Constitution should be applied uniformly

in all sections of this country.

The approved plan has been in operation only a short

time. Particularly in light of the freedom of choice option

superimposed upon the geographical zoning, no reliable

prediction can be made as to the effect of the plan on

desegregation.

Moreover, any resident of a geographical school zone is

entitled to attend the school serving his zone regardless

of race. Federal law now prohibits racial discrimination

in the sale of homes. It is quite possible that acquisition

of homes by Negroes in predominantly white zones will

promote racial balance in the schools. The approved

teacher desegregation plan should also produce more racial

balance.

The busing issue is siibsidiary to the neighborhood

school issue. Busing is of course, frequently provided to

transport pupils living at a substantial distance from the

schools, particularly in sparsely settled areas. Here a

neighborhood school is at hand. Judge Young states that

the evidence shows that the annual cost of busing in event

of the proposed pairing of districts is $500,000, which ap

parently is exclusive of required capital expenditure. The

busing issue presents the additional problem of whether

such a substantial outlay could not be better used for

educational purposes.

Absent authoritative guide lines from the Supreme Court

as to the constitutional status of neighborhood schools in

metropolitan districts, the Board upon remand would be

at a loss to know what course to take in devising a desegre-

— 26 —

gation plan. The remand for the proposal and considera

tion of a new plan for desegregation, absent more specific

guide lines, would only create confusion and lack of sta

bility in the Little Rock school system.

We would affirm the order and judgment of the trial

court in its entirety.

A true copy.

Attest:

Clerk, U. S. Court of Appeals, Eighth Circuit.

ANNEXATIONS

DFSCfRPTiCN

OOiS?

©7734

.O Z6203

055

LITTLE ROCK ?URBR.’06t

i..t "Tc ca«.

STREET INDEX AND CITY LIMITS

PREPARED BY THE CHriq nfi >r5

DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT

■ £.*/TZa / f t , ^ / , f t X o j / t r

13 Rou/a/ DL2 fa *

0 LM >? /R rr£#£>4A>ej? Zo/v&

f X / h r * # j f Z w c

.1 /Yirffitf ft,

CAMMACK

VILLAGE

<SKE£f/ B'R&vJV

'BLUE

6RETV

R\*=Y| 0P<?f, TH(y/

s