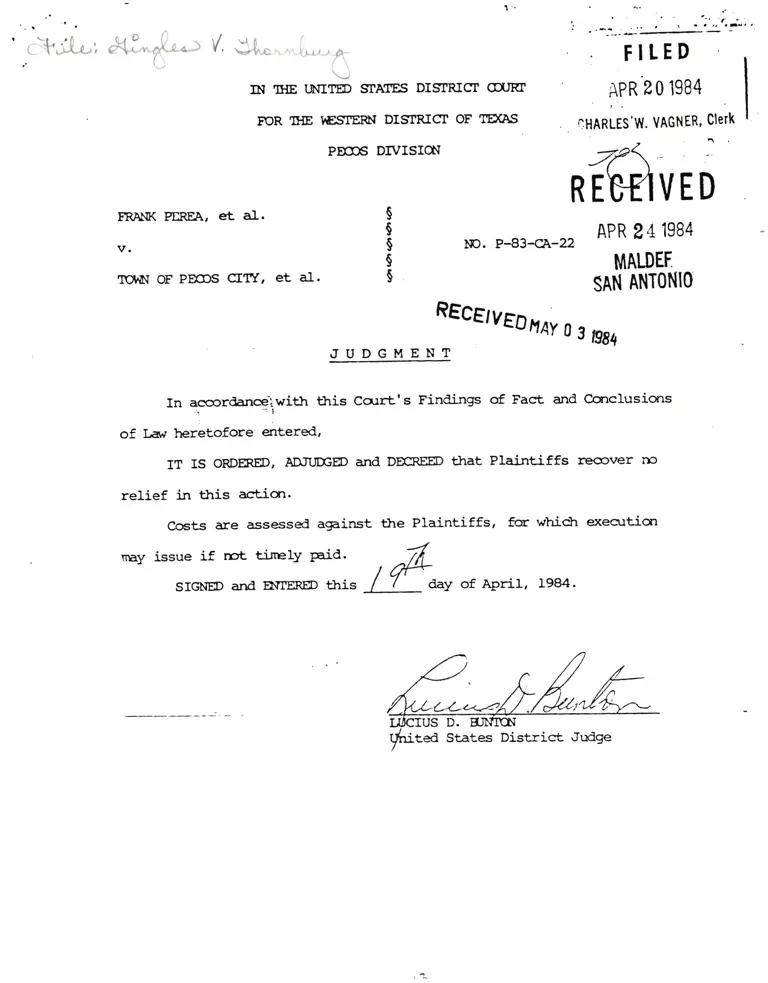

Perea v. Town of Pecos City Judgment; Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law

Public Court Documents

April 19, 1984

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Schnapper. Perea v. Town of Pecos City Judgment; Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law, 1984. 79d89fac-e292-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/11c0bdd1-13b2-47af-ab97-ee3ca5d48273/perea-v-town-of-pecos-city-judgment-findings-of-fact-and-conclusions-of-law. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

\, .t-: t',.-L{-,; .1:, .,{ . s- ': (

FBANK PEREA, Et. A1.

v.

T(ISI OF PECDS q[IY, et aI.

1.

vl i

!'rtrt' ,\r, ,*1

\.v

IN TIIE II{ITED STATES DISTRICT @JRT

FOR I}IE I.GSTERN DISTRICT OF TE(A.S

Pre DTVISICnT

.,.'... - ;",,,;..

r4 IAPR'2019t

.**lirl*. vAGNER, crerr I

$

$

$

$

$

IXC. P-83-CA-22

4\

REBflVED

APR 2 4 1984

MAt.DET

SAN ANTONIO

REcE,yE0ray

0 3 p8{

JUDGI"lENT

In aordance-lwittr t}is Canrt's Findilgs d Fact and Ccnclusions

of Law heretofore entered,

IT IS ORDERD, ANtreED and DECRED that Plaintiffs recover no

relief in tllis actian.

Costs are assessed against tJ.e Plaintiffs, fcr which scectrtior

nray issue if rPc tirrEIY F,id.

, Of,-

Slctlgcl ard ENIERD tS'ris / | day of April, 1984.

ted States District Judge

.]HARLES

IY

a<

--/l \

\-/

s

s

s

s

s

IN THE T'NITED STATES DISTRTCT CTXJM

FOR lHE TTES'TETD{ DISIRICI OF IE(AS

PE@S DIVISIOT.I

RECEIVEDI'IAY

O 3 ST

FRANK PEMA, Et 41.

v.

lOlYlI OF PE@S CIIY, et al.

NO. P-83-CA-22

FINDI}SS OF FACT AND @NCX,USICDIS OF I.AI{

PlAiNtiffS FBAM FEHEA, OrcA OFNELA'S' &Nd thc LEAGUE OF UNITD

'1

LATIN-AIIERICAI,I C:ITIZHNS (LULAC) bring this aetion p-rrsuant to Section

2ofttreVotingRightsAct,42U.S.c.slgT3,corrplainingthatthepre.

sent at-large, no plaee, plurality winner electoral SystsTE instiltuted

by Defendants IOTYN OF PE@S CIIY and PE@S-BAFSTOW-IOYAH INDPBIDE\U

:

scll@L DISfRICf, provide Mexican-Anericans "less qpportunities than

other nember.s of the electorate to participate in the political pro-

a

cess and to elect legislators of their ehoice.'' Id' S(b)' In

essence, a language mlnority grorp, 42 U.S.C. s1973b(f )(2), whicrr

group is in fact an evergr&ing clear rnaiority of ttre pcpulace and

registered voters in the area in question, seeks to establish a single

nrember district electoral systern in ttre TO!{N OF PmS CITY and the

PMS-BAHSIOI{-IOYA}I INDEPENDET'IT SCHML DISTRICT.

Having reviared all of the evidence presented at a bench trial

held on March 14, 1984; the pleadings, briefs, sJtd argunents of coun-

se1; and the controlling legaI authorities, this Court is firmly of

the cpinion that Plaintiffs' claim is neither supported in Iaw, nor in

the facts of ttris @use. Accordingly, p-rrsuant to Fed' R' Civ' P'

.a4.2

FILED

APR 201984

. VAGt{ER, Clerk

-. .? -

- a .. .*t '

52(a), t1.is Ccurt enters the follo*ing findings of Fact arul Canclu-

siqrs of La!^, rrycn whieh a judgnant fc Defendant-s shall te enteiea.

EINDI}ilGS OF TACT

1. According to tJle 1970 federal census, Reerrcs CorrEy, Texas

--tlre situs of t-his acticn-had a total pcpr:latiqr of 16,525 at the

tiJrE of that ensus. Of tJris tortal, 8,804 were Mexican-Arrerican citi-

zens of tlis Ccgnt-.:qz. As slctr, rore tJlan 53t of the total gqr.rlat.icn

was Mexican-Anerican. Of the total te,SZS tr)erscns, 527 ot nore thart

38 of t;.e lrpulaticr was-Blad<. As suctr, rore t}.an 56t of the irrhabi-

tants of Reeves Ccunty, Toas rrcre rur-Anglo in 1970.

2. An examination of the 1980 federal census records reveals

ttrat Reeves Cotrntlzr Te:as had a total pcA,rlaticn d 15,801-a decrease

of nore than 4t frun the I97O federal census. Of t}.is toLal, 9,785

were Mexican-Anerj.can citizens of tJ:is Ccuntry--art increase of IIDre

t]tan llt frsn tle 1970 federal census. As sr.rcltt, 62* of the Ccurrty's

pcpulaticn was Mexican-Anerican. Of ttre I5,8OI persons, 375 or

a5proxinately 33 rrere Blacl<. As suctt, IIDre tJ:an &3 of the jrihabi-

tants of Reeves Cctrntlr, Tocas hrere ron-Anglo in 1980.

3. T,his sanre 1980 federal census reuaa.Ls t}at tf:e I(XAI OF PEES

CfTf, TD(AS had a total p,cpulatiqt of 12,855 Perscns. Of t].is total,

7,939'"ere Mexican-Anerican citizens of t}is Canrrtqr. As s:ctr,

alproxirrately 62? of tJle city's lrpulaticrr was Mexlcan-Anerican. Of

the 12,855 persons, 365 or alpr-oximately 3t of ttre pqxrlation were

Blacl<. As such, atrproxirrately 65t of the intrabitants of the TOhN OF

PEGS Cf,tY, TD(AS rtrere rorrAnglo in 1980-

4. An examination of this sane 1980 federal c.ensus reveals that

-2-

the PE@S-BARSIUFIOY?H INDPEMENI slrcL DISTRICI had a total Pcpu-

I'lexicarAnerican citizens of this Ccurrtr)t. Of t}re 15,591 PerscrE,

atrptoxfurately 3t urere BIad(. As s.rdt, nDre t}ran 641! of the sdrol

district's lqpulation hras ron-Anglo in I98O'

5- ftcrn 19@ r:ntil 1983, rprt. courrLing t]le latest APril, 1984

city electicn whictr r,ras held after t-}.e trial of this cause, 65 Anglos

ran fior a otrrnilnanic positicr in the 1OIAI OF PE@S (XTf , TD(|S ' Of

-these 65,fi:glo,,cnndidatcs; '39 c q>proxinately 6Ot usr electicn. '

Dr:ring tlis safir priod tiJrE, 33 Mexien-Anericans ran fc otrnci]nanic

pcitians. Of ttrese 33 candidates, nile cr aSproxirrately 27t P=.

electisr.

i

I: $. Etcm 1965 r.ntil 1983, not acurreing tl1e latest April, 1984

l

sdl.ol district electiqr w?rictr was held after tl:e trial of t].is cause,

I

66rang1e tan for a positicrr cn t]le PECOS-B{RSXEIIJ-IPAH INDPBIDBTI

SG:rcL DISfRIgf bard o,f Tnrstees. Of these 66 Anglo endidates, 4

or agproxirrately 57t rrsr electicn. D:ring this sare period of tirne,

24 MexicarAnericans ran for sd:ol board seats. Of these 24 Uexican-

Anerican candidates, five'& aSploxi-nately 21t rsr electicn.

-.-- 7:, xn:r.ing ttre latest-April, 1984 city electi.crr, trdc octlrF '

cilnanic peiticrrs, as r.,e11 as the rmyoral peiticrr, trEe q>en and

contested. Of the trrp'clty ouncil Seats, one was filled by a

ltexicarAneri"can oandidate tlrat' &feated Ure ino-unbent Anglo-candidate,

while the ots5er o.rncil seat was reta.ined Qr tlre Anglo incr-urerent. Tfre

rnayoral peiticn was filled W a Mexican-Anerican vfro defeated tlte

L/

Anglo ino:nbent.

-3-

.... .*,.'

8. D:ring ttre salne April, 1984 scjtrol board electj.st, t:*c seats

,.

qr t].e PffiBARSIUT.I IIIDPEDIDENI st{@L DISTRTCT bard Yrere qdi 'and

contested. Of tlle seven candidates v*ro vied for tihe trro q>en seats;

the 6,o !1exicapAnerican candidates utro ran fc tJre trrc trreieicns here

successfrrl. Ttre five Anglos'*ro ran fc a seat qt the sctrol bard

were all defated.

9. A revierr of ttre r,rcter regrisuratiqr data of the 1983 PE@S-

BARSTUFTU]IATI INDPENDELIT ffiML DISTRTCT EIECTiCTT TEVEA1S t}TAt

Mexican-Anericans onprised a;:pr.oxirrately 55t of the registered \rcters

in t].e district. Only 4proximately 43t of thg regi"istered-rcters in

tlre sctrol district were Arrglo. ' '-l '' : j: '1 i.:

IO. A reviav of tlle \Dter regristr:aticn data of the 198O city

electiqr reveals that agproxirrately 51.5t of the registered rc'ters

were MexicapAnerican, rrtrile tJle registered Anglos orprised cnly

approxilately 44.8t of the"tcrtal. -A similar rewiei of tlie data frqn

the 19gl city electiar reveals t).at q>r'oxirrately 5IS of 1}re

regristered \Dters riere Mexlcan-Anerierts, ttrile aSproxirrately 45t

vrere Anglo. A revier of tJle 1982 city electiqr data reveals that

53.3t of t].e regristered rrcrters \iere MexicarArerican, uh.ile qproxi-

nrately 45.5t bere Anglo. . A similar revie*r of the 1983 city e-Iectian

data reveals ttrat qrproxi-nately 54t of t}e reg:istered \rcrLers vEre

MexicarAnerican, vfrrile 4proxirrately 46t were Anglo.

11. Althcugtr are identj.fiable secLion of the TO!$I OF Pffi GTY

is primarily t'bxican-Nrerican, the renairuler o,f the city is integrated

and nc pattern or practice exists as to the segrregatisr of rEi$l-

borhods \r race cr Ey etlrrie cr naticnal crigin.

-4-

i ,.-- .,,..

:

12, No fornal c, infornal systenr exists for tJle slating of en-

didates frcr ary offic.e in eittrer electoral gystern at issue in tf.ip

cause. It is lI,tdisErrted t].at arw lErscn who desires IIBy freely run

for any position.

13. No racial atrpels, r^hetJrer based uPon subt'Ie cr otrert

attenpts to ga.mer \rc,Ees, is seen jn the calrpaigns cf endidates to

an), Fositicn in issue in tf.is cause since it is very c'lear that a can-

didate my rot cbtain office witjlort finding sr:ppcc iJ] bth t].e Anglo

carnJrtity and in t}e Mexican-Arerican onrunity.

tll Sinc€ the Mexican-Anerican residents of brth electoral

systens dre clearly t}e najority jn actual ru-rribers of ppulac"e iana in

registered \ilters, and will corrtinue to be an increasing rajority in

bo,th if established trends ontinue, the irrpact of lnlari-zed toeing

(whether it exists or nc't) has nc detrirrental furpact r4nn the election

of l,lexican-Anerican candidates to either elected body jn i-ssue in tl1is

cause.

15. !0ri1e it i.s lg-s*n that Anglos jn Reeves Ccrrrrty, Te:ras at

one Lirre treated "etfuric and racial mlrority" grcu;= badly, srrch i-s

nort. sriderrt today. Althcugfir tj:e seio'econqnlc orrctilicns of the

MexicapAnericans cf Reeves CcunCy, Te:ras are ncrt. sYnderoncusly equal

to the status of their orrespcrrd.ing Anglo @lnterParts, tlte electcral

systens in issue in tlds cause have rp direct influence qr suctr orr

ditiars. Fac*.ors bryond tJ:e ontnol of ttre TCfiN OF PE@S (fTY and the

pEOS-BABSIcnlFroyli{ r}IDpEmBrr sctlool. DrsfRrcf,-sudr as rationa}

policies-have a far greater i-npact. upcrr tJ:re Lifestyles of arqr

?/

"mirnrity" gtrottp in Reeves Ccurty, Te:as'

' ' " ''""

-5-

t

:

:-t

16. The Pffi-BARSI\*FIOYAH INDPEIIDENI ffimL DISIRICT is

go\Erned by a se\reHlEnber Board of Tnrstees. Tnrstees are elgcted

to staggered terns Irrrsuant to a prre at-large systenr in vihicjh "no

places" or 'pcts" are.eplq;ed.. In t}at at-large qlstan, ro najority

vcte qgsten and nc anti-single shot provisicns are arplqled.

17. Ttre IDt&{ OP PEOS C[nf's gprrerrurent is a cotrrcil form of

governnent onpc5ed of five co.rncil Persons and cne IIBllor. The courr

eil per-sars are elected to staggered terns Srrrsuant to a lure at-large

SyStern in whieh "nO plac-es" Or ";rOStS" are enplq,red. In tlrat at-large

systern, rn najority vote sl/stern and rrc anti-single strct. provisicns are

enplqged. . _. ::

l-

j

Defendarrt-or br any perscn fon that ratter-as to t.tte e:rercise by anv

perscn of their ri*rt of pa*icipating in the electonal qlstens ulrder

sctrtirry in tl.is actiqt.

19. T?re Plairrtiffs sed< pnoportianal "neigttborhod rePrF

sentaticr" in tSis acticn. €uctr h,as revealed ty Oreir om testirroqz.

In esselce, plaintiffs trcpe to esta,blistr prognrans fcr {*re relief of

po\,Erty o'f the local MexlcairAnrerican p:trxrlaticn b/ electing Perscns

rriho agrree witf. suctr cbjectives and who have inaginative neans of

readring sue:r r$le ends. Unfontunately, the cbjects of tltis cause-

t1.e electoral systens of the city and sdrol district-have Little, if

any, causal irlpact tpcn their pligtrt.

@NSJUSTONS OF I3I"T

I. Ttris Ccurt has jurisdiction cnrer this rmtter. 42 u.s.c.

-5-

- . . .-, r

$rgzg; 28 u.s.c. $$r34g, and 220r

i .

2. Nlc perscrr cr. grro.lP of 5=rscrs has arry @natituticnal right

to harre propeticral representatiqr il their elected officials and the

gorrernnental todies t4:cn whie} tlrose elected rrepresentatives and offi-

cials sit. See Nevett v. Sides, 5?L F.2d 2O9 (5th Cir. 1980), celt.

denied, 445 u.s. 95I, silis, White v. Regester, 412 u.s. 755 (1973):

I'naitccmb v. Chavis, 4O3. U.S. L24 (1973); Kirksry v. Bd. of Sul=r-

visors, 5il F.2d I39 (5ttr cir. 1977)(en banc), cert. denied, 4y

u.s. 968.

3. PlaidLiffs reed nc,C strcr arryr discriminatcry inteilt in their

,t:

prera.illng upori a clairn borangtrt under Sectian 2 of t}e Voting Rights

Act, 42 U.S.C. $I973(b). Jsres v. Citv of Lr:bbocJ<,

-r.za(5tfr Cir. March 5. 1984) (not 1,et, reported); Vel?sqtrez v. Citv of

Abilene, 725 F.2d 1017 (5th Cir. 1984). Ho*ever, Plaintiffs & bear

ttre tr:rden of establishilg \r a prepcnderance of tJ:e evidence tJ:at

"the drallenged systern or pr:actice, in tl:e alntext of alf t}1e clr-

cunstarpes in t}re jurisdictisr in question, results in mlnorities

being denied egtral access to tJ:e lnlitical process." S.Rep. No. 417,

97t}1 Ccrrg., 2d Sess., reprinted i:r 1982 U.S. 6de Cqrg. & ful. Ne.rs

L77, 205.

4. Initially this Ccrrrt mrst rrcte ttrat since ttre ctrallenged at-

large electoral qfsters are racially reut::al ulur their f,ace, bo'th

systefils are presr-rred valid. Nevett 1:-.Qi<pg, slJpra, 57I F.2d al 228.

Ttris is better understod as that t).e at-Large qlstents are rpt trEr-se

urnonstitutional. Roqers v. Herrnan Idge, _ U.S.

-,

73 L.Ed.2d

1012 (1e82).

-7-

- . .. .-.4r.

I

:

,

5. In Zirrrer v. !,tcKeitlren, €5 F.2d 1297 (Stl,r Cir. 1973)(en

banc), aff'd. sr:b rsn., East Carzoll Parish Sctrol Boa:rd V. l'larshall,

424 U.S. 636 (1976), t}e United States Cq.rrt of Alp€als fcr the Pifth

Circtrit established rariors factors vrdch a Cctrrt nay arplq1 in

judging the irrEnct qpon a glurp's constitutional ri$rt to In::Licipate

in tf.e e.lectorat process. In judging whettrer ttre qlsters n*r wder

attacl< are dissirninatory, tJlis Ccurt wiII enplqr' these Zirnrer he

torsr as veII as ot1.ers. These factors have been incorpcrated into

the anen&rent of Secticn 3 and. as slcl., reveal the cler legislative

intent of t}e anen&rent

:

: --.,;

(6) Mi:nr.ity Access to ure slatinq of canaidates :

t. ' :

In reviari-ng tl.e eyidence presented in tj.is cause, it j-s

patently elear t).at nc fornal c. inforral process exists for tl1e

srating of candidates in either erectorar s1'ssn' ArL witnesses

. testified that rp person has ever been denied.the ri*tt to rrrn as a

political candidate, nor has arry trErscl ever been advised cr co.rnseled

agai5st runrr'ing fcr lnlitical office. In fact, an examinaticn of the

evidence gxesented reveaIs that the nentrers of tJ:e Ftexican-Aricart

csrrunity have recently rdalized their trrrtential porer whictr has rlrtil

n*r laid dornant frcrn their o{n rsruse'

(b) Respcrrsiveness of Elected Offi.cials to "Ftinoritv" Needs

AF.i-11 it rn:st be stressed that the 'lninority" in this cause is,

-in f,act., a clear na}crity of -tlie-pSxrlace resid.ing in the s1'stere-{t}f-

r:nder attad< and a c.Iear rajority of t):e registered vcters in bth

systerns. Si,:r'rce rrc evidenqe reveals art/ cbstJarctiqr in the 'tninority"

merrbers' exercise cf their ri$et 'to Participate in the electoral PrD-

-8-

iA.

: -- , ,.

.. :

c€sS, any atleged unrestrslsriveness of the electd officiale'it *u

result o,f t].e Mexican-Anerien rajr:rity's failurre to elect ofticials

who will resporrd to Oreir subjective reeds'

An er.aminaticn of tlle record reveals that ttre City arploys a

firre-year plan of develc4rrent ylhich farrcrs ro p::tierlar area of the

city. In t1.e tisrt u,rat the city is fc tJle ncst trnrt irrtegcated, ro

par-ticrrlar grcup reed suffer frqn ttre fair exeqrticrt of that PIan.

The testirrorqr and evidenc€ presented also strers t}at aside frcrn

several isolated oplaint-s ablt tJre respcnsiveness and cnretrerycrl-

siveness of t].e local police, and fsn a single orplaint abo:t cne

particular rpad's onditicrr, rD unrespcruiiveness to ttre 'lninority's"'

needs is shosn. In f,act, t1.e plaintiffs' qrn wit-nesses stated tlrat !|re

Mexica'-Anerican ormlrdty, asi a vihole, uses and fenefits Ancm the

wittr regard to tl1e sc*rol qlstem, it m:st be rD't'ed that'nc

- disqiminaticn r*as strern to be practiced ty it. In fact, the evidence

reveals tf1at an active and aggrreseive mirprity teac$er recmitnerrt

program is in q>eraticrr. F:.crn t}ris drive, 21t of the teactrers ldred

during the last )rear have been Mexican-Anerican. Sudl is a-Iso evi-

denc.ed Ey tf.e fact ttrat t}rr€e of ni.:ne principal:. in the slrstent are

1/

Mexican-Anerican, ctLile b^Io oLhers are Blad<'

No evidence is trresented to sho,rr tJ:at the at-larrge qlstern is

erqplq,'ed Sxrrsuant to a tern-rcus gnliry wtdch irr fact furthers 6 crauses

a disaiminatory iJrpact.. The sridence presented shors that the at-

large q/stern is r:sed to ilsure that all granPs are treated equally'

In fact, if strctr a district plan was irrplenented iI tf.is action, since

1

= ii

t

(c) Tenucr.rs q!4!e_lgl

-9-

A.

t}e onn:nity is fc the nost part integrated' exclgPt for the 'cne

established !'lexican-Anerican rei$rborhod, the rsr-l'texican-erericans

conceivably o.r1d suffer in t}rat ttrq;'rrctrld nost }ilely be t].e victjrlls

of diluted roUing strength in rrario.rs districts, since t}e Mexican-

Anrericans otrld rDt cnly ont-r,ol the district in whictr the single eth-

nic reigfiborhod resides, h:t conceirably also t-l.e cther districts as

well.

(d) Histeical Discriminatiqr's Effect t4>cn Present

Fa-rticipaticrn il Electoral Processes

.fhe shanEfi:I past disairninatory practic.es o,f Reeves Ccurrty are

in nc i,"V ,*i+re to that area. This'inglorictrs trEst is shared ry all

)

areas. Horrever, one generatiqr's igrrorancre strculd rot tn lnssed &.m

to alotJ.er greneraticn in tJ:e form of jnflicted pr:nishlrent. Such

merely destrcys the progress ttrat nen have sl:ared in ttre erergence of

civil rig1ts in tlds Cd:ntqr. It nust be nlted that the Reeves Ccurrby

sc*rols \^Ere integrrated IIBfiy years befce suctr r,ms eitJrer fashicnable

or before it was re$dred [r federal intenrenticrr. No evidence has

been presented ttrat reveals ttrat arDI trErscn i-s deterred frsn Par-

ticilnting in the electoral prlcess because of a Past generation's

ignoranc-e and o,rstcrn. Plaintiffs' w'itnesses stated ttrat nc 1=rscn is

ncrr deterred by anlr disejminatiqr, eitl:er past c present, fircrn par-

ticilnting in tJ1e elestoral Pltcess. Plaintiffs' coplaint goes cnly

to the prcportianal quality of t}at elected represent-ation.

(e) Erhancenent Factors

As set forth pnevicusry in this opinior' bo'th qlstens & nct'

emplq; "arrti/single strcrt" \roting provisions, r:or does eittrer qgstent

erplqg nrajority vorte pr.ovisicns for t}le electiorl of arqr IETscr,I to

"' a" .

- . .. .-ar,

-10-

office. An attempt to lnstaIl a systern based upon "place" candidacles

was plevented W this Court ln 1977. As sttch,'the at-laXge systam

employed ln both systems attacked herein ls the falrest tool of repre-

sentation for tlte systans lnvolved ln this cause.

6. In the legislative hj.story and explanation of the arngndnent

of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, several other factors are

developed besldes the factors established ln Zinrner. See S. Ep. No.

4L7 al 28-D, reprinted at, 1982 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News at 2O7;

H.R. Rep. No. 227 at 3O: White v. kgester, supra, 4l-2 U.S. 7ffi-7o.

These are also of help in iudging thd systenrs :[n is-sue.. ]:

-. , -i :---- - -;:;

=

(a) Racial Camoaien Tactics hesent in Wstenrs

:

A barureter of tllre ethnic tension in the cunrunity, wtrich i-s a

good rEa.sure of ttre degree of discrimination in t}te conmunity, whether

real or i.nugined, is whether candidates employ raeially cn ethnically

biased naterials in thelr-campaigns. A11 parties w'iI1 agree IDne are

present in ttris cause since both ethnic connmnities are rteeded to

obtain victorY.

(b) Voting Polariiation

Another fairly accurate barcnreter or lleasul:e of discrimination

in a connn:nity, &nd Carried over into ttrat conmunif,5r's electoral

-systenrs i-s t}te ertent to which the ettrnic groups polarize the vote.

ThiS ls better understmd as that a "true minority" nEmber cannot

obtaln vietory il an election because of ttre block voting of the

majority group to deny the candidate's victory. As e4plained pr€-

vicpsly w'ithin this Opinion, polarized voting has l1ttle if any role

in ttris cause since the 'tninority" which is seeking the relief is

-11 -

actually a najority of Ore perscns eligr:ible to \Dte and registered to

vc,te. In Ligtrt of the facts that nc irrpeeirrents are established'to in "

arq/ ieq,/ hinder t.}.e "minority's" nenbers fron participating iI tJle

electoral systenrs attacked in this acLion, this f,actor has nc rel*

vance to the acticn.

7. In revierying t}is cause, this cctrrt i-s tJ.crfuled I cne

matter which r.lrfortr:nately is far beyond tJle trn*er tJlis Ccurt

pGsesses. That ratter is also @zond the rreledial sope of arqr

authority exercised by either t].e TCXtr'I OF PmS gIY cr t}e PECDS-

BARSIUFTUy,AII INDEPEI{DB7I SCrmL DI!{RICT. Suctr. is t}re socircc\cncmic

pfi$rt of a pontion of the }lexican-american -tt*rrtity r=siding within

i

Reeves Cq1nqr. In cbjectively o<amining t}e ifacts of this cause, tlr'is

Cctrrt has rpt nealt to be clinically cold to tJ:e plight of the resi-

dents o,f Reeves Ccurrty. Ho,lever, s.re]. I[fe of rrrerrplclznent, crimirn'I

activity, and social disenfr-anctrisenrent is a natter of rstiqral pclicy

a5d econcmy far bqfclal tJle limited authority of tl, is tsial cotrrt andt

ttre local ocrnrunity gorernilg bd,ies disctrssed in this aseion. Thre

Atrpellate Cctrrt vfrdch ptentially sits in revisrr of ttris r-rrique case

nu.rst t€at i ze tf.at greh socio-ecrcncntlc failings of tlrat 'lninority" @[Tr

narnity i-s rnre reflected in its people's atrproactr to denocraql' In

fa*, sude plight has beccrre a prirre.l instigator in roving ttre nasses

to the electicn bottr. Irltr,ile nc't. ire any hay redueirg tlte ctercus b.rr-

den that nErry labor unler, tl:is socio-econcrnic naladlz is acLually

causing those persons to par^ticipate in tJ:e qlstem that guarantees tJle

Iifting of t;.at }::rden fircm their badcs. As suctr, tJ:is Ccurt is nrcst

hesitant to tirker witi tf.e fine nachineqr of denocraq;.

. . .. .4.'.

-12-

- . ,. .-4, .

@NCLUSICt.I

Having forrd that thq l.texican-Anerican orm:nity of Reerais ,

Ccurrty is an evergro*ing na3Ority of that Ccrrnty's trr4r.rlaee and

registered yprters, t;.is Ccurt is npst hesitarrt to irrpose its will t4ut

ttre nembers of t].at onrnrnity so as to insure tllat 'lninority" a better

Iife. In examining t5e evidence presented at trial, tJ1is Cotrrt nctes

that in eramining ttris cBuse irt tJ:e totality of the circunstances, rto

d"issiminatory result a irrpact is seen jn t}e electoral processes in

issue in this (Buse.

Ar. o<aminati61.r o,f Plaintiffs. various c.Iajms for reIief reveals

that pliintiffs istually sed< tJlis canrt to either {gHarantee thent pr}

- .-1 r .,i' ! - trportidaf 'rEprbsi,ntatitrl cn tJ:e-elected bodies--in iissue in this (EUS€,

i..l

or to cder t5e nentrers of t]:e 'lninority" to pa:ticipate in the elee-

toral systens in questicn in this cause. Since a-II Parties rnrst agree

tllat }lttle, if arw, evidence stro'vs any denial of t}e ris1t to par-

ticipate in t5e electoral Prlcesses, this ccurt, having nc lffex or

desire to order 1=cp1e to par-liqate in t).e vorkings of tJ:e'ir

darrcraql, rnrst stter judEnent fcr Defendants. Tlr-is Ccurt is a^rare

that in tfre rnrt-to.d.istarrt fi:trrre, the Anglos of Reeves CctrrrEy cottld

very vpII be in this Cctrrt i:ringing ttre claims for rrelief that

Plaintiffs ns.r present. Ho,r,ever, finding that Plaintiffs enjql the

sanre "c54>ortunities [as] cther llpJrbers of the electorate to par-

ticitrnte in gre lnlitical prccess and to elect legislatons of their

ctroice, " this Co:rt. enters judgrrent f95 Defendants'

SIoTD and EVIERED *i, lq U day of April, 1984.

ted States Dist-riet Judge

?/

rwnrorrEs

L/ h:rsuant to Fed. R. grrid. 2O1, this Ccur^t takes judicial notice

of tle adjudicative facts of the results of the city and sc*rool

board ete&iqrs held iJl April of 1984 afEer tl1e trial of this

cause. Suctr electicn results have been c€frified and tlte

elecLed officials s"orn in to their elected pciticrs.

The historical evidence Presented reveals t}at the Mexican-

Anerican onnunity was previcusly derried tJle berrefits orf society

shared by rrenOers of the Anglo orm:nity thro'rgftrcttt the CcurrEy

of Reevel. These past acts of ollective dissiminatiqr are

seen as tJre derrial orf srjrrming privileges in tJle nunieipal

pols, denial of access to novie theaters, and the tra-r'assing

-a:rests of minority putl.s fu. being in t}e Anglo secticn of

to/n.

Althcr-rgh sueh past acts are inexolsable and universally danned

by ttri; Ccurt, slrell. ignOrant and reprgrnant acts, in the absence

oi prrcf of present dissirninalicrr of tlte "minority's" Par-

ticipaticrr in the electciral Plocess, are irrelerrartt.

This Co.rrt has thono.rghl1r oarnined tJ:e evidence Presented [z

plaintiffs of alleged presentday discrirnination. Sudr evidence

appears to te: (1) tne denial Qr the Cannty RegrisU:ar of deptty

r-.gist =r status to persans other than her in'office detr:ty

r{i.tr"ts scnetjrre in 1970-71; (2) isolated instances of elee

ti&s officials informing all persans roting that thql ould

vote for tro Perssls cn t}e ballot since tro psiticrrs tere q>ert

and ontested; and (3) electicn officials refi:sing to allor tr=r-

scns jnside electian bo'ttrs with roting indivi&rals.

As to the first ratter, this Cctrrt rrcrt'es that sudl lalere i'nnedi-

ately renredied ty t}re Ccunty Regfistrar when she was infcn'ned ty

the sesetary ofl state tJ:at she o.rld legalty a-llor cut-of-

office perscrrs to be deplty regisb:ars. As-to tlne second

rnatter, tl1is Cqrrt finds t}at su<*r jnstructidls liEre isolated

and resulted in nc diseiminatoT irrpact r4:an t}e Mexican-

Anerican onnuxrity. As to the third ratter, t}is Ccurt finds

suetr acticrrs entirely correct.

Accordingly, the past igrroble Hstory of Reeves Ccunty is nerely

that--th; p"=t r.rrfort,:nate history of igrnorance. Horrever, suctr

has nc cau!fli5pact rpcn the 'tninority" gru.rp's right-s_lo Par-

ticipate in preslnt{ay electians. The latest A;rril, 1984 elee

ticrr- is proof of tl:e rodern tristcqr of Reeves ccurrEy' Toas'

Th-is Court &es rrte that it is disturbed ty the drryut r:ates

of all hdividuals fzun the PE@S-BARStOIFTO)BH II{DPB{DENI

SCffmL DlslrR[clr . Such &es rpt bode well for tl:le fi.rture resi-

dents and leaders Of the area. Hosever, no evidence is prg-

sented to stro.r tJrat sucJ. is the result of arry dissiminatian in

3/

-L4-

the sctrcols. In light of the fact that t}re sdrsll qlstern was

integrated long befce t)le Brum Suprenra Ccrrrt decisiqr was

enfoicea in West Te:as, and-Eince suctr qlstenr actlvely see)<s

ninority edr:cators in positions as both class-r@m ed:catcocs and

as adnrinistr-ators, and fur-tlrer tlat the "minority" is able to

elect officials to tJle district's governi:rg hod1z, ttris Ccurt is

in nc positicrr to jnflict its perscnal atrpnoactres to edr:caticn

utrur ttrat s),stern.

Tfr.is Court a&ritisrally des rp't. believe tJrat it shculd beclsrE

enbr.oiled in t}e r:niquely "Texan" dispute as to whee daughters

shcuLd be batcn brirlers in the higfi seJlol band. Such is best

Ief-t to ttree Perso.s r^i:to have tlte q:ercus b-rrden of pidcing

such onnu:nity tan&naidens. Tkris Ccurt &es nct' w'ish to enter

tJre lntentially f,atal, and urquestiarably volatile area of

nr*her{aughter vicaricus achievenent.

-15-