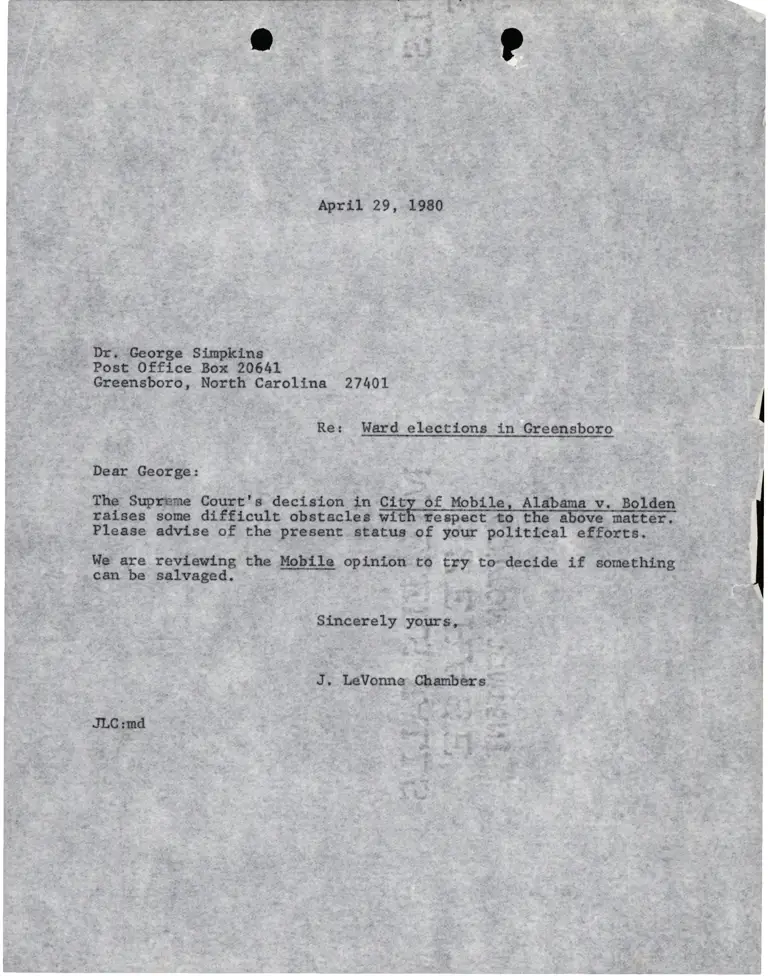

Correspondence from Chambers to Simpkins

Correspondence

April 29, 1980

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Williams. Correspondence from Chambers to Simpkins, 1980. 80b5dae8-d992-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/11c39a58-fead-4d84-893d-ddce69cb2efe/correspondence-from-chambers-to-simpkins. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

:

,+

Aprtl 29, 1980

Ilr, .f,eorgr Strpklne-' Poct Offlce Box 20641

Greensboro, Nortb Carolina 2740L

.!'..U

I:l

,1)

{

",

, !: ,,

The Snprtme Corlrt's declrlon l.n Ctgy.tif !troblIe. Alibaoa v, Bolden

raleee aoloe dlfflcult obataclir

Please advlee of the presanE 3trtur of ybur poltttcal ef.fo:te .

: .\. :

Ifc a5e revlartqg the Holtb oplnLon.to try t-o"'decLde lf eornething

can be salvaged.

-

.:'

Dea( George:

JLC rnd

. ', ':'

Rer Ward electlons ln Greensboro

..

Slncerely

J. treVoruro .Cbrubire

i ,.'