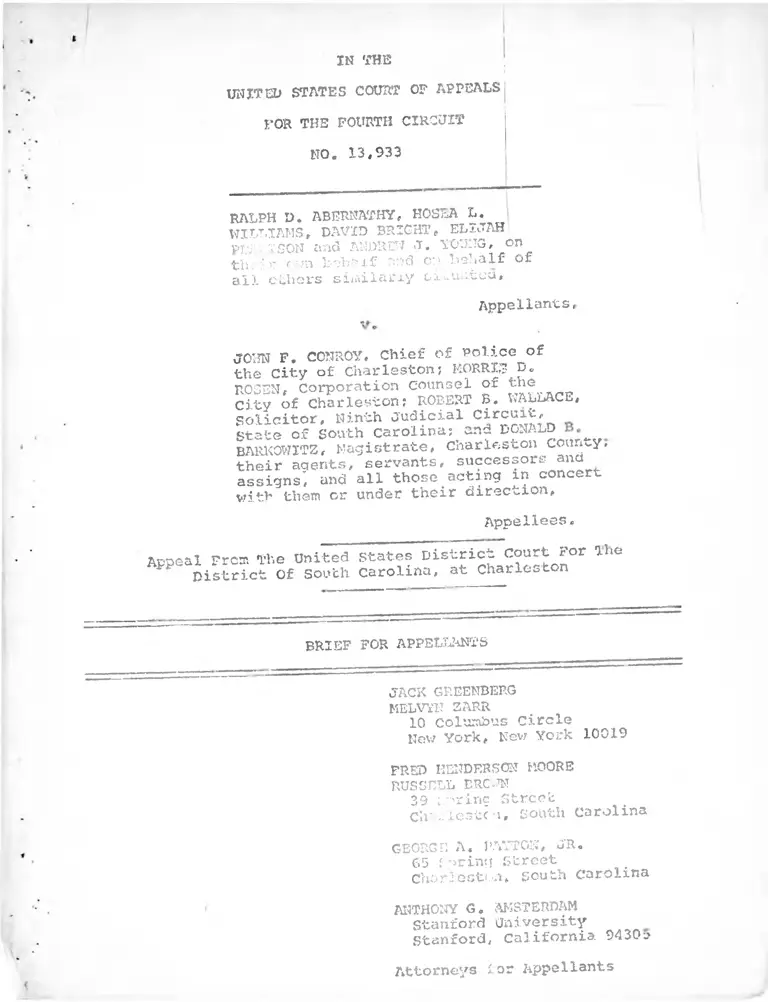

Abernathy v. Conroy Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Abernathy v. Conroy Brief for Appellants, 1970. 71e31aba-ab9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/11f07f63-653e-4780-9682-e563ab56c9fc/abernathy-v-conroy-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IK THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

for the fourth circuit

NO. 13,933

RALPH D. ABERNATHY, KOSi-̂ A L.

WILLIAMS, DAVID BRIGHT, ELIJAH

ppiirrsON and ANDREW J . YOUNG, on

their own behalf and on behalf of

a l l e t h e r s s iu v i la n y exi-U citco,

Appellants,

JOHN F. CONROY„ Chief of Police of

the City of Charleston; MORRIS D*

ROSEN, Corporation counsel of the

City of Charleston? ROBERT B. WALLACE,

Solicitor, Ninth Judicial Circuit,

State of South Carolina; and DONALD BARKOWITZ, Magistrate, Charleston County,

their acter.ts, servants, successors and

assigns", and all those acting in concert

with them or under their direction.

Appellees.

Appeal From The United states District Court For I*1® District Of South Carolina, at Charleston

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

JACK GREENBERG

MELVYN ZARR10 Columbus Circle New York, New York 10019

FRED HENDERSON MOORE

RUSSELL EEC-AT39 Spring Street

Ch' riestc .■ i, South Carolina

GEORGE A. PAYTON, JR*65 S p rin g street

C h a r le s to n , so u th C a ro lin a

ANTHONY G. AMSTERDAM Stanford U n iv e r s i ty

Stanford, California 9430u

Attorneys for Appellants

V

INDEX

Issue Presented .... ..............

Statement of the Case .............................• *

Argument

I, South Carolina's common Law

Definition Of Riot Is vague And

Overbroad And The Court Below Erred in Refusing To So Declare.....*

II. The City Of Charleston's Absolute

Prohibition Of Peaceful Protest

Marches After 8:00 P.M. Violates

Appellants' Rights To Peaceably

Assemble And Petition The Govern

ment For Redress Of Grievances.... . •

Conclusion

1

2

3

18

21

• '

Table of Cases

Ashton v. Kentucky, 2-84 U.S. 195 (1966) ............• •

Baker v. Bindner, 274 F. Supp. 658 (W,D. Ky. 1967)... 13,17

Cameron v. Johnson, 390 U.S. 611 (1968) --- - 13,17

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U.S* 2o6 (1941)..»•••••• 15,17

Cottonreader v. Johnson, 252 F. Supp. 492 (M.D.

Ala. 1966) ..................... ..................*

Cox v. New Hampshire, 312 U.S. 569 (1941) ...*•••••»* 18,20

Davis v. Francois, 395 F.2d 730 (5th Cir. 1968).*. 14,17,19

Dombrowski v» Pfistor, 380 U.S. 4/9 (1965)..*..*.. 11,12,13

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U.S. 229 Q 1Q n 16#17

(1963)... ........

Gregory v. Chicago, 394 U.S. Ill ( 1 9 6 9 ) •

Robinson v. Coopwooil, 292 F. Supp. 926 (N.D.

Miss. 1968) ..... .

Shut11esworth v. Birmingham, 394 U.S. 147 (1969).... 10,19

#

Table of Cases (continued)

State v. Brazil# Kice, 257 (S.C. 3339) “

State v. Cole, 2 McCord 117 (S.C. 1922)

state v. Connolly, 3 Rich. 337 (S.C. .................. 15'^®

state v. Johnson, 43 S.C. 123. 20 S.E. 988 (1895).....

Stromberg v. California. 283 U.S. 359 (1931)........*<j- ”

Strother v. Thompson, 372 F.2d 654 (5th Cir. 1967).... ^

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U.S. 1 (1949) • — — — *••

young v. Davis. 9 Race Rel. L. Rev.

June 9, 1964) .....................

Zwickler v. Koota, 369 U.S. 241 ................." " "

and orainances_invo3jrea

................ 4

28 U.S.C. §1343 .......... 4

28 U.S.C. §2201 •

.............. 5

28 U.S.C. §2281 .... .............r. .......

42 U.S.C. §1983 ......... •*.*’"***,e...... . _

Charleston City Code, §31-195 ........

South Carolina Code, §16-113.1 ..... *......*"**” *

ii

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT.

NO. 13,933

RALPH D. ABERNATHY, H'

WILLIAMS, DAVID BRxGIT

PEMRISON and ANDREW J

tuo.\r own behalf and

all others similarly

9SLA L.

!■„ ELIJAH

„ YOUNG, on behalf

situated,

on

of

Appellants,

v.

JOHN F. CONROY, Chief of Police of

the City of Charleston? MORRIS D.

POSFN. Corporation Counsel of the

City of Charleston? ROBERT B. WALLACE,

Solicitor, Ninth Judicial Circuit,

State of South Carolina? and DONALD B. BAF.KOWITZ, Magistrate, Charleston county?

their agents, servants, successors and

assigns, and all those acting in concert

with them or under their direction,

Appellees.

Appeal From The United States Distr District Of South Carolina, at

let court For The

Charleston

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Issue Presented

Did the district court err in dismissing, without a hearing,

appellants' complaint seeking declaratory and injunctive relief

against South Carolina's cordon law crime of "riot" and the City

of Charleston's ordinance banning all parades

8:00 p.m., on grounds they trench upon rights

peaceable assembly and petition for redress of

in the city after

of free speech,

grievances?

<:4-a-t-cmcnt of the Case

This is an appeal from an order of the United States

District court for the District of South Carolina dismissing,

without a hearing, appellants' complaint seeking declaratory

and injunctive relief against South Carolina's common law crime

of "riot" and the City of charleston's absolute prohibition of

protest marches after 8:00 p.m.

The suit was initiated by officers of the southern Christian

Leadership Conference (SCLC), an organisation dedicated to the

promotion of civil rights through peaceful and nonviolent means

(Appendix 5a). In entering its order of dismissal on the plead

ings, the court below was obliged to consider as true the fol-

lowing well-pleaded facts (App. 6a-7a):

The aforementioned officers of SCLC [Ralph

D Abernathy, Hosea L. Williams ana Andrew J.Young] have been engaged throughout the spring

1969 in conducting peaceful assemblies P C

the government cf the State of Soutn redress of grievances, namely, grievancesing ?he facial and economic discrimination prac

ticed against Negroes in their employment at tnc

South Carolina Medical College and the Charleston County Hospital. These asser^Ues, conformably

to the tradition and discipline °fSCLC,h ^een consistently peaceful and nonviolent. On a numnero? oooasicns.Pthe plaintiffs or persons associated

with tho plaintiffs have applied for and recci

parade permits pursuant to Article X.Charleston City Code for various assemblies

processions.

On June 20, 19S9, about 11:30 p.m., plaintiffsAbernathy. Williams. Bright and Pearison and

approximately 250 members of the classtheyrepresent assembled at the Memorial Baptist Church

rin charleston] and attempted to walk a distance

if a S S flur blocks to a nearby park to conduct

a nraver vigil as a further means of petitioning

for redress of grievances. A H the Petsons in

church had been carefully counseled about fc LC s

unalterable insistence upon nonviolence. Aile-

the group had proceeded approximately two bioc^.,

2

or about halfway to>ts domination, ̂ Defendant^

Conroy directed plaint d t COnroy announced

group, which he did. 5eJ®n| ™ he? because they

that they could Pro^ ^ parade permitdid not have a Parade p - * under the expresshad not been appiied for, bee Jharieston city code,

terms of Section 31-19., 05J h50^ a orocession after none could have been granted for a proce^

8:00 p.m.

Af.er being informed that the 9«»?PJ°“i%lf°nd^

no further, plaintiff p-h%''X^lrlT£d the two blocks

ant Conroy if his group o/si^ly. as not toto the park m small g p Article XIV. Defend—

come within the P ^ lthat°neither he nor any member ant Conroy announced that no . the prayerof his group could proceed to the park tor u I

vigil.

Thereupon, Plaintiff pfayfrTigil

knelt down and conrov ordered them toon the spot. Defendant Co Y' ac-monished him not

desist, but plaintiff ^b®«\ 7 Thereupon, with no

to interrupt the ’’i S m l n seizedfurther warning, three or to - P 50 ards

Abernathy and forcibly car williams, Bright

to a police seized! Prior to thoseand peanson weie similarly peaceful and non-

-rests. * * ? , * ; S r - S ? S h S t 5 S S i ® riot and, at

a % 0J.oZ\*nk each'. An addi-

inltt charge o?fpa;°ai?ng without a permit was

lodged against each.

on June 24, 1969. appellants filed their complaint seeking

nvalidation of the riot law" and Section 31-199 of the

harleston City Code^ and an injunction against their further

1/crime.

Apoellants originally challenged n m ^ J ^ forth Appendixbut also South Carolina ^ 8 ^ 1 1 3 . 1 . . .. ....,t also South Carolina .«= S ^ - maae on the theory

3. 20a. The challenge again. the common law crime — the

that — given th,;,in“ £i ‘y X t ubstantive definition. The dis-

statute might ell-113.1 is merely a penalty statute (App.

HT. °a° r a p p f u a n ^ dfnot challenge that ruling here.

t r o ^ L Sb e f o r r B ^ r ta?m.Uno f ® ™ i S a t e after 9=00 p.m.

3

enforcement•

Appellants challenged the common law crime as (APP- 8a) 1

offensive to the First ana y°“^ | eytat^s°i>ecause

to the constitution o ' cffense of riotof vagueness and h- , < under south

has no specific and ^characterisations

Carolina l £ bey" purport to punish

assertbliesT^notwithstanding^their^lawful^urpose#

^ nnollvflVlcht 33?' (1832) .

Because Of the ^ 0“ a £ notfcS ofw£a?

e J e a v e s tco -ch^iscre-

tion on enforcement to the P o l i = ^ ( 3 ^ guiit;

establish any ascertai rights of free expres-

(4) deters the exercise of “ l^tition for redress sicn, peaceable assenbly a « f t of sweeping and

of Grievances; (5> is su&e^p richts of freeimproper applicaticn trenc^g ^ petition for _

expression, peaceanl * fails to distinguishredress of grievances: which oreatesbetween mere advocacy and a clear and present danger or not.

AS to Section 31-195. appellants claimed it "arbitrarily

suspends at 8:00 p.m. the exercise by citixens of Charleston

of their First and Fourteenth Amendment rights to peaceably

assemble and to petition the government for redress of grievances"

(App. 7a)*

The suit was brought as a class action under 28 U.8.C. §

§1343. 2201. and 42 U.S.C. §1983, with appellants Abernathy,

Williams, Bright and Pearison representing the class of persons

.Who have been or will be subjected to prosecution under (the two

laws" (App. 4a), and appellant Young representing the class of

persons "deterred from engaging in conduct protected by the

Hirst and Fourteenth Amendments to the constitution of the Omtec

States by the existence of these laws ard the prosecutions

described" (App. 4a-Sa> . s l i c e s - ^

4

corporation counsel of the City of charleston, the Solicitor of

the State's Ninth Judicial Circuit ana the Magistrate of

Charleston County who ordered appellants imprisoned in lieu of

$50,000 bond each. The chief of Police is the officer who

placed the appellants (except appellant Young) under arrest; the

corporation counsel is responsible for prosecuting appellants

for parading without a permit; and the Circuit Solicitor is

responsible for prosecuting appellants for “not."

On June 24, I960, appellants presented their motion for

release on recognisance or, in the alternative, for nominal bail

(App. 12-lSa) to Chief Judge J. Robert Martin, Jr. Judge Martin

declined to rule on the motion, deferring to District Judge

Charles E. Simons, Jr., who normally sat in the charleston

Division, but who was absent from the district that week.

On June 30, 1969, following Judge Simons' return to the

district, a hearing was held. By that time, appellants had been

released on bond and their motion was moot (App. 19a). Judge

Simons heard argument on the necessity of convening a three-judge

court pursuant to 28 O.S.C. §2281 and then granted leave to the

parties to submit memoranda on that issue. Appellants filed their

memorandum on July 7, 1969; on July 11. 1969. appellees filed

their memorandum and answer. The answer, in relevant part,

averred (App. l?a)*

Plaintiffs Abernathy, Williams, “ ^ourtPearison have not been convicted m a state court,

n o-tate of South Carolina has had no _

S f way

J

B 5

beyond the normal concern

prosecution, plaintiffs'

declaratory judgment and

premature.

tants of a criminal

application for -

injunctive relief is

On August 11, 1969, without further proceedings, the dis

trict court entered an opinion-order dismissing the complaint

on the pleadings, holding:

1. That a three-judge court was unnecessary because S.C.

Code §16-113.1 is merely a penalty statute (App. 29a);

2. That appellants had made no showing sufficient to justify

injunctive relief (App. 25a-29a);

3. That appellants had made no showing sufficient to

justify declaratory relief as to the common law crime of riot

(App. 29a-31a); and,

4. That Section 31-195 of the Charleston City code was

constitutional (App. 31a).

The denial of injunctive relief was promised upon two bases

(App. 28a) :

1. "pr]he prosecutions arise from acts not within the pro-

tected ambit of First Amendment rights and not supported by any

showing of irreparable injury or impairment of freedom of

expression"; and,

2. "There is no allegation in plaintiffs* complaint, or

any showing before the Court that the common law offense of

rioting and sir,-113.1 of the South Carolina Code are being used

against the plaintiffs in bad faith by the State. County and City

Officials for the purpose of harassing them for exercising their

constitutionally protected right of freedom of expression, with

no intention of pressing the charges, or with no expectation of

6

obtaining c o n a t i o n , a„a -owing that piainti^' — ai«

• -i c-hr'■<=>' s criminal laws."not violate the St«-o s

The denial of declaratory relief as to the common

of riot was apparently premised upon the same two bases (APP-

30a) : ^ .

!. "[Tlhere is no invasion into the area of proteote.

rights for peaceful assembly and petition

»[Tlhere is no reasonable basis for a finding of bad

faith on the part of the State officials concerned."

. at? "a proper exercise by dneSection 31-195 was upheld as a pxopo

City of its inherent police powers" (App. 31a).

appellants' timely notice of appeal to this court was fx e

September 3, 1969.

7

Argument

I.

|

South Carolina's Common Lav; Definition

Of Riot Is Vague And Overbroad And xne

Court Below Erred In Refusing To So

Declare.

in rejecting appellants' attach on South Carolina's common

law definition of riot, the court below began by attempting to

distinguish Mr. Justice Black's concurring opinion in SS232S*

v. Chicago. 334 0.8. 1U. 118-19 (1969). in which he condemned

"moat-ax" statutes "gathering in one comprehensive definition of

an offense a number of words which have a multiplicity of meanings,

some of which would cover activity specifically protected by the

First Amendment."

The court below stated (App. 30a) s

In the case at bar, however, this court

has concluded that the common law crime or

riot and accompanying penalty statute canno^

be deemed to have the effect Ot the meat. ax

statute which sweeps so broadly.

Why? The court below*s only attempt at reasoning is

contained in its next paragraph (App. 30a):

mhe State's legitimate concern with pro-a s g * j S - s j -bad faith on the part of the State ofi-ici

protected^rights fS^peaSeSui^ssembly and petition.

NO one doubts the legitimacy of the State of South Carolina's

concern with prohibiting acts of violence. Bun the i.-sue

is whether or not that legitimate concern 1ms been translated

into a "precise and narrowly drawn" penal law (Edwards v. South

Carolina, 372 U.S. 229, 236 (1963).

# 8

The district court apparently avoided decision of this

issue by stating two propositions (App. 30a):

1. ..[Tjhere is no invasion into the area of protected

rights for peaceful assembly and petition"? ar.c,

2. "[TThere is no reasonable basis for a finding of bad

faith on the part of the state officials concerned." j

Appellants submit that the first proposition is unsupported

and the second irrelevant.

The court below's first proposition is apparently a

repetition of its point earlier made in denying injunctive

relief that "the prosecutions arise from acts not within the

protected ambit of First Amendment rights" (App. 28a).

the court below determined that is a mystery. The only facts

contained in its opinion are those it was obliged

ns true in dismissing the complaint on the pleadings (APP. 22a-

23a) :

Throughout the Spring o f ^ h a v ^ b e e n along with many other sympathize . h lines, engaged in conducting assemblies, p d th Snd demonstrations, and have PrtiiiOTed tte

. ri-p confh Carolina and the Caunty or State of South ̂ alleaed qrievances.Charleston for redres racial'and economic

namely those con^ ® 2 ^ 1 v practiced against Negroes discrimination alleged y P Carolina Medical

Co 1 legerand̂ * the^Charleston County Hospital.

,whii? h T ^ 1s L i n2 r c»8i?ii b ^ si?-?onptm!:

Abernathy? Williams, Bright and Pearison^and

approximately the Memorial Baptistrepresent, assembled t th M -^out four

Church, and then attemp . . prayer vigilblocks to a nearby P f * “ c o n d u . w ^

as a further means of P 4'1 ’ allege that,of their grievances. They fu:"approximately two

after the group had proceede TP Defendantblocks or halfway to its destination, cere

t 9

Conroy alrect?a Plaintiff halt

the group, wni could proceed no furtherannounceo thou they ̂P pemit to parade

because tuu-y a_ ^ that under the

a t t h a t tim e o f / ^ L o n 3 1 - 1 9 5 , supjra, o fexpress terms o permit couldthe Charleston City coue, no P afterhave been obtaxned for a proce f alleges

8*00 p.m. . - * m e croup could

that, after being in* °™^thy inqnlrla of Defend-

proceed no further, could proceed the tv;oant Conroy if his marcher. P s0 as not to

blocks in small groups, or 9 ^ charleston

come within the Pr? ^ ^ ° c o n r o y announced that City code? than Defe* * _ hi0 crrouo couldneither he nor any n.ertbor of nis gro OTa

proceed to the ^ * ^ £ 1 £L?iathy and the. that thereupon pla^nt_r conduct theirothers knelt down and b g n conroy ordered

prayer vigil on the spot, bhat admonished himthem to desist, but Abernarry ̂ ^ that

not to interrupt the p. / were arrested

“ E a t S e subsequently charged with

?ioPand1kraad?ng w ith o u t a permit.

These facts do not depict conduct beyond the -bit of

first Amendment protection. Indeed, the conduct h e r e « v e ry

Similar t o the conduct vouchsafed by th e Supreme Court rn

, . „ ,uora in Edwards, about the sameEdwards v . s o u t n _ c a r o l r n a . s u E t a . » _________ _______________

hurch m Columbia,« here assembled at a cnurcnnumber of persons as here a. tuition

south Carolina and then waited to the State Capitol t P

for redress of racially discriminatory practices rnt -

The City M anager o f Columbia described t h e i r conduct a t th e

.nond 11 and "flamboyant,Capitol Grounds as "boisterous, loud,

. a "religious harangue” by one of the leadersconsisting of a reiigi d

■ • patriotic and religious songs, accompaniedthe loud singing of patriotic

, ino of feet and the clapping of hands (372 U.S. by the stamping and nonviolent.

,33, ThGir conduct, albeit noisy, was peace

' • lea Of breach or the -oace, a common

They w ere arrested and convicted of b .e

10

law crime which, in the words of the South Carolina Supreme

Court, was "not susceptible of exact definition" (372 O.S. at

234). The supreme Court of the United States reversed, hoidxng

that the common law crime was so vague and indefinite (

permit the punishment of conduct protected by the rirst Amendment s

guarantee of free speech, peaceable assembly and petition for

redress of grievances (372 U.S. 237-33).

Tho court below apparently attempted to distinguish Edwards

on the ground that there was violence or threats of violence on

the part of appellants (App. 30a, . That attempt must fail, for

it is completely unsupported on this record. The only

distinction between appellants' conduct and the conduct in

rondu'-t was quiet and at night.Edwards is that appellants concur

But that is a distinction without a difference for present pur

poses. Even assuming arguendo that appellants were in violation

- r_ r,Vlir,a at night without a permit of the parade ordinance by marching au nig

and that the ordinance is constitutional (but see Argument II.

infra), that would not deprive appellants of standing to challenge

___ in nombrowski v» Pfi|lbe£.£the riot law. As the Supreme Court, noted in -----

380 U.S. 479, 486-87 (1965):

[Wle have consistently allowed attacks o making

statutes with no conduct could notthe attach demonstrate eh.it the requisite narrow

be regulated oy a statue ^ this exception to

specificity. . * we . ' . u ■„ because of thethe usual rules governing s t a n d i n g . Qf pijrst Rmend-

..... danger tf -ole-ating^ ^ al statute suscep-

meat freedoms, the exiSi-enc application”. . . Bytible of sweeping and improper II idit of these

permitting determination or t edibility of some

statutes without regard to case8f we have, in

regulation cn the facts freedom of expres-S T M T S T J £2 ttSSSJu*,*!--

1/ T U tecttKat ■- well

— some persons in the crowd 9 of vioienc® imputable to appel-

“ K 373 U.S. 203 (1063).

Obviously there are bound to be limits to who has standing

to challenge such a penal provision. A district court, after

hearing, might conclude free the evidence that the plaintiff

had engaged in such acts of violence that his conduct "would

obviously be prohibited under any construction" of the challenged

law, and that accordingly he should not be allowed to

law in a court of equity. See Dombrpwski. SUES. 380 U.S. at 492.

But a violation of a valid parade permit ordinance, if proved,

could not deprive a federal plaintiff of standing to challenge a

vague and overbroad riot law, for such a violation is simply not

the kind of conduct which would be prohibitable under any con-

struction of the riot law.

The second basis for denying declaratory relief — that

there was no showing of bad faith on the part of appellees

• w ants neither alleged bad faith,is simply beside the point. Appellants neiv

nor were required to do so. The vice of a vague and overbroad law

is precisely that it allows policemen (and prosecutors and gudges

as well) in all good faith to infringe the liberties of the

citisenry. A vague and overbroad law leaves too much discretion

to policemen and prosecutors, tending to implant in them such an

inflated view of their authority over the citizens' liberties

• ,.,,^.1 faith believe they are simply enforcingthat they can in good taitn ceneve *

■•the law." I» a case such as this, the trouble lies in the law.

not in the law enforcement officers, south Carolina's definition

of riot is so vague and indefinite, as we shall show, that appel

lants could not hope to prove that the appellee police chief and

prosecutor charged them with riot "knowing that [theirj conduct

did not violate the State's criminal laws" (APP- 38a). indeed.

12

*$

*

it is precisely because of the vagueness ana inflefiniteness

of the riot law that the far-fetched quality of these prosecutions ^

is not obvious to all - including the appellees.

Two decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States make

this point clear beyond peradventure. in ESskssaSi SiizSaS,

suora. the Court plainly stated (380 U.S. at 489-90) :

free expression, or a.-, appiiea (Eroohasisof discouraging proceeded activities i,

supplied),

And in Cameron v. Johnson, 390 U.S. 611 (1968), the court

applied nembrowski so as to leave no doubt of the disjunctive

nature of these two theories. The court's holding is in two

petes. First, it agreed that the district court's duty was first

to grant a declaratory judgment as to whether or not the chal

. face as abridging free expression lenged statute was void on its race

(390 U.S. at 619); it then proceeded to approve the district

* court's ruling that the statute was constitutional (390 U.S. at

63.5-17). Next, it considered - quite independently of the first

point - whether a case for injunctive relief on a theory of bad

faith enforcement — mentioned hore for the first time had

been proved (390 U.S. at 617-22).

The irrelevancy of bad faith enforcement to the issue of the

aopropriateness of declaratory or injunctive relief against laws

which are attacked on their face as abridging free expression is

, n ( ^ noy ?74 P. Supp. 658 (W.D. Ky.nicely illustrated by Baber v. Bmdner,

oiri+- brorcht by civil rights 1967)(three-judge court). In <* suit or „

i

t 13

» 1

demonstrators to invalidate the three state statutes and three

clty ordinances under which they were prosecuted, the three-judge

court invalidated the laws for vagueness and overbreadth, but

specifically found police good faith (274 P. tupp. at 650,.

we find no unconstitutioMlfUseof ̂ n^therwise

constitutional statute. V 7^- the police

Court are at a _oss to - under the err-

whichfplaintiffs would have

found no fault*

Thus it is apparent that, in the^judgment^of

this court, the plaintiffs, i complaint in

practicality, have no g aii of the

this situation could we freedom ofordinances ana statutes c* constitutional,

expression in this liSd certain ofThis we are unable to do 5 possible sweepingthem vague and overbroad, and of £OSSi£j£.

applieation.

Though, as heretofore stated, fc" f u* ^ _

the defendants herein ordinances in a manner

stitutional statutes a 1 -i-beratelv to suppress

which might be ^ ^ ^ f ^ ^ a i n t i f f s andth^^class^such statutes and ordinances ̂ heing

^?fiS;'beC?trici.GaownSaS unconstitutional.

Any unconstitutional statute, attemptingto regulate First Amendment rights^which^has^^

pS??onno f m u ? e f e5 ”iUinb: J ^ f I « e ? ! ? inSt

? e ^ n ° y ^ s i o n of -^itutional rights.

oilskves^naMe^o invoke the abstention doctrine outbc-ivta defendants. . • •as urged upon us 0/ enc.

Francois. 335 F.2d 730, 732, 737. note 13See also Davis v.

(5th Cir. 1968)* ,

Accordingly, neither basis of the Court's refusal to decide

the issue of the validity vel non of the riot law is supportable.

The district court should have decided the issue and invalioated

South Carolina's common law definition of not, as the S p

court invalidated Connecticut's common law offense of breach of

the peace in centum v. Connecticut, 310 U.S. JOB, 303 (M,D

for

_ variety of conduct under asweeping in ® f i n i t e ebaracterization. andI S l B ^ o H n £

The general ana indefinite characterizations in South

Carolina's riot law can he seen from the following definrtrons

Of common law riot given by its courts in a number of 19th

century decisions. (No Twentieth Century appellate aecrsxons

defining riot have been found):

1022

•A rict is defined to be

three or more persons, who shallt° assist one another agaxn.t^any^ entGrprise

oppose them m the e f and violenceof a private nature, with I°££ifest terror of the

against the peace or to t itself lawful orpeople, whether the act were of lt-elexecute the

unlawful, provided they procee 6 117).

thing intended" (State v. Cole, £

183 ?

“ a riot is defined

turbance of the P®ac®^ own authority, withassembled together, of ^ each other against

the intent mutucill̂ them, and putting theirany one who shall opp terrific and violentdesign into execution in a terriii ^ nQt>

manner, whether the object was

(State v. Connolly;, 3 Rich. J-WJ .

1839

Sami as State v. Con^l^. S£PX| (State v.

Brazil, Rice, 257 (Court of Appeals)).

1093

_ , y..> (ot ate v. John sen,

43 VT. 1 2 3 7 ^ 5 ^ . -it' (Supremehiourt)) .

- 15

From these definitions, one may extract the following

profile of the elements of common law riot:

1. An assemblage of three or more persons;

2. With the intent — whether lawful or not — mutually

to assist one another; and, I

3. A "tumultuous disturbance of the peace conducted in

"terrific and violent manner"; or "force and violence against

the peace or to the manifest terror of the people, whether the

act were of itself lawful or unlawful."

These elements might very well be deemed to cover the

attributes of a performance by the Beatles. More to the point,

they might very well be deemed to cover a "boisterous," loud,

"flamboyant," "religious harangue," with loud singing and the

stamping of feet and the clapping of hanos. See Edwa-d^. v.

south Carolina, supra, 372 U.S. at 233.

We do know that the common law offense has been successfully

applied to everything from storming into a plantation at night,

firing guns, killing the plantation's dogs and beating the

plantation's Negroes (State v. Cole, supra) to running

"foul of" a boat pursuing runaway Negro slaves (State SSSSSliX)

For example, in State v. Brasil, supra, the court noted that "an

indictment was sustained for riotously kicking a foot ball in

the Town of Kingston . . . It was an amusement, but accompanied

with such circumstances of noise and tumult, as wore calcula

to excite terror and alarm among the inhabitants 01 the town

(Rice, 259).

The central vice of the common law crime is that its

,3 t-ho vaaue and overbroad common 3 awdefinition is weaved from fcne g

16 -

/ offense previously invalidated in Edwards v. South Carolina.,

supra. I t must meet the same fate, for it poses the same

danger to those rights of free speech, peaceable assembly and

petition for redress of grievances exercised in Edwards. See also

StrorcbercT v. California, 283 U.S. 359 (1931). Cantwell v.

Connecticut, supjra; Terminiello v. Chi.cago, 337 U.S. 1 (1949);

Ashton v. Kentucky., 384 U.S. 195 (1966) .

As to the district court's denial of injunctive relief, it

was, of course, error for the Court to consider that issue in

advance of the prayer for declaratory relief. Cameron v. Johnson,

supra, 390 U.S. at 615. But in the present posture of the case,

it is not possible to determine whether the issuance of injunctive

relief is or will be necessary. Certainly, injunctive relief

against the enforcement of penal laws invalidated on their face

as abridging free expression cannot be denied for the reasons

given by the district court (see p. 6-7, supra). But it may be

that a declaratory -judgment will suffice to protect appellants'

First Amendment rights. See Zwlckler v. Koota. 339 u-s- 241' 254~

55 (1967) ; Baker v. Bindner, supra; Strother v. ThcmESon, 372 F.2d ‘

654, 657-58 (5th Sir. 1967); Davis v. Francois, 395 F.2d 730, 737

,5th Cir. 1968). Accordingly, the district court should be directed

to retain jurisdiction on that score.

%✓

4/ 3outh Carolina's common law crime of breach of the peace

there d e f i n e d -a violation of public order. •

the public tranquility, by any arc or conduct i . ■ *9 'it includes any violation of any law enacted to pre^e r

peace and gSod order/ It may consist of an set of violence or

act likely to produce violence. . . - (372 U.S. at z3_.)

i

17