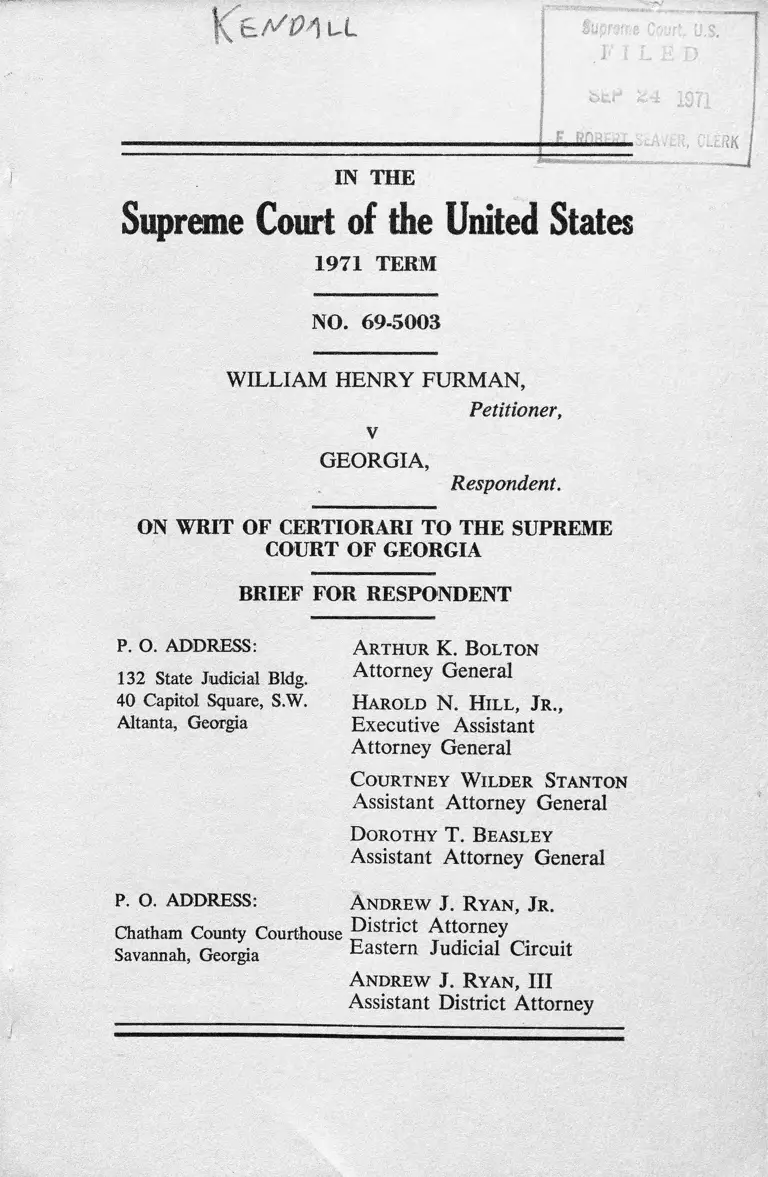

Furman v. Georgia Brief for Respondent

Public Court Documents

September 24, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Furman v. Georgia Brief for Respondent, 1971. 4ceaff90-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1201defb-3cac-4f98-aad7-ec98e565c0c9/furman-v-georgia-brief-for-respondent. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Kt/^uL

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

1971 TERM

NO. 69-5003

WILLIAM HENRY FURMAN,

v

Petitioner,

GEORGIA,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME

COURT OF GEORGIA

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT

P. O. ADDRESS:

132 State Judicial Bldg.

40 Capitol Square, S.W.

Altanta, Georgia

Arthur K. Bolton

Attorney General

Harold N. Hill, Jr.,

Executive Assistant

Attorney General

Courtney W ilder Stanton

Assistant Attorney General

Dorothy T. Beasley

Assistant Attorney General

P. O. ADDRESS: ANDREW J. RYAN, J r .

Chatham County Courthouse Districrt Attorney

Savannah, Georgia Eastern Judicial Circuit

Andrew J. Ryan, III

Assistant District Attorney

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PRO

VISIONS INVOLVED ...............

QUESTION PRESENTED . . . . . . .

STATEMENT OF THE CASE . . . . . .

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT . . . . . . .

Page

1

2

2

2

ARGUMENT:

I. The death penalty for

murder is not per se cruel

and unusual, in the con

stitutional sense, and is

therefore not a depriva

tion by the State of Peti

tioner Furman's life with

out due process of law . . . . 20

II. The "Indicators" of un

acceptability of death

as a penalty are not

reliable yardsticks,

are not relevant or ap

propriate yardsticks, and

do not provide accurate

measures for determining

that standard of decency

beyond which states may

not go in fixing pun

ishment 45

11.

III. Capital punishment is an

appropriate maximum pen

alty for murder in our

society today and its

use is not forbidden to

the states as cruel, and

unusual punishment in

contravention of the Eighth

and Fourteenth Amend

ments ...................... 84

IV. There is no issue in this

case concerning Petition

er's mental condition at

the time the sentence was

imposed because (1 ) no

question was raised at

any stage of the proceed

ings below, either at

trial or subsequently, and

(2) there are no facts

which cast any real doubt

on Petitioner's mental com

petency at the time of sen

tencing; rather the record

plainly shows otherwise. . . 88

V. Georgia law safeguards an

insane man from execution. . 92

CONCLUSION 95

1X1 .

APPENDICES:

APPENDIX A:

Statutory Provisions and

Rules Involved........... la

APPENDIX B:

Crimes Under the Criminal Code

of Georgia Punishable by Death . lb

APPENDIX C:

Persons Currently under Death

Penalty in Georgia, Sept. 20,

1 9 7 1 ............................ le

IV

TABLE OF CASES

Aikens v. California ................ 20

Barbour v. Georgia, 249 U.S. 454

(1919) . . . . . . . . . . . . . 90

Bartholomey v. State, 260 Md. 504,

273 A.2d 164 ( 1 9 7 1 ) .............. 82

Brady v. United States, 397 U.S.

742 (1970) ...................... . 86

Brown v. State. 215 Ga. 784 (1960). . 94

Butler v. State. 285 Ala. 387,

232 S.2d 631 (1970) . . . . . . . 82

Duzier v. State. 441 S.W.2d 688

(1969) . . . . . ................... 82

Edelman v. California, 344 U.S. 357

(1957) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 89

Ex parte Kennmler, 136 U.S. 436

(1890) ........... . . . . . . . . 22,

23, 35, 36,

38, 85

Howard v. Fleming, 191 U.S. 126

(1903) . . . . . ................... 36,

37, 69

Jackson v. Georgia, No. 69-5030 . . 17

V.

Louisiana ex rel. Francis v.

Resweber, 329 U.S. 459 (1947). . . 23,

24, 25, 35,

38-39, 44, 58

McGaut’ha v. California, 402 U.S.

183 (1971) ............. . . . . . 34,

39,

69, 79, 83,

84

Manor v. State, 223 Ga. 594

(1967) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

Massey v. State, 222 Ga. 143

(1966) ................. 82

O'Neil v. Vermont. 144 U.S. 323 (1892)

.............. 36,

37, 85

Parker v. North Carolina, 397 U.S.

790 (1970) .......................... 86

People v. Walcher. 42 111.2d 159

246 NE2d 256 (1969). . .............. 82

Powell v. Texas, .392 U.S. 514,

530 (1968).................. 53

Rivers v. State. 226 S.2d 337

(Fla. 1969) .................... 82

Robinson v. California. 370 U.S. 660,

682, 683 ( 1 9 6 2 ) ................. 29,

43, 53

VI .

Schmid v. State. 226 Ga. 70(1970) . . 15

Sims v. Balkcom. 220 Ga. 7 (1964) . . 82

Solesbee v. Balkcom. 339 U.S.

9 (1950) ........................... 25,

26, 48, 53,

94, 95

State v. Calhoun, 460 S.W.2d

719 (Mo. 1970) . . . . . . . . . . 82

State v. Cerny, 480 P.2d 199

(Wash. 1971) ...................... 82

State v. Crook, 253 La. 961,

221 S.2d 473 (1969) . . . . . . . 82

State v. Davis, 158 Ct. 341,

260 A.2d 587 ( 1 9 6 9 ) ............. 82

State v, Kelback, 23 Utah 2d 231,

461 P . 2d 297 ( 1 9 6 9 ) ............. 82

State v. Rogers, 275 N.C. 411,

168 S . E . 2d 345 ( 1 9 6 9 ) ........... 82

Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86,

89, 100 (1958)............... 27,

29, 33, 39,

40, 42, 46,

52, 53, 85

vxx.

Weems v.United States.

370-371, 384 (1910).

217 U.S. 349,

28

29, 31- 32,

33, 37, 38

48, 53, 85

Whitus v. Georgia,

545 (1967) . .

385 U.S.

79

Wilkerson v. Utah. 99 U.S. 130(1879). 35

Williams v„ State, 222 Ga. 208(1966). 12

Wilson v. State. 225 S.2d 321

(Fla. 1969) . . . . ......... 82

Witherspoon v. Illinois. 391 U.S.

519 (1968) ...................

61, 63, 78

79

VXXX.

Annals of Congress, Vol. II,

Appendix pp. 2274, 2281 . . 86

Bedau, H., The Death Penalty

in America, (Rev. ed 1967)

p. 120. .................... 51

City of Atlanta, Department

of Police, 91st Annual

Report, Dec. 31, 1970 . . . 80

Cohen, B . Law Without Order

OTHER AUTHORITIES

(1970)...................... 51

Ershine, 34 Pub Op Q (1970-

7 1 ) ................... .. - 60

Farrand, The Records of the

Federal Convention of 1787,

Vol. I, Yale University

Press 1934 .............. .85

Georgia House Study Commit

tee Report, 1968 House

Journal, p. 3451........... 59

Georgia Senate Study Commit

tee Report, 1966 House

Journal, p. 2669. . . . . . 59

X X .

Good Housekeeping, November

1969, vol. 169, p. 24 . . . 61

Hearings before the Subcom

mittee on Criminal Laws and

Procedures of the Committee

of the Judiciary, United

States Senate on S. 1760,

March 20, 21, and July 2,

1968... . . . . . . . . . . 58

Mutchmor J. R. "Limita

tion of Death Penalty in

Canada" Christian Century,

January 24, 1968, Vol. 85,

P- 120......................49

Nation's Business, November

1970, vol. 58, p. 28. . . . 60

Newsweek, January 11, 1971,

pp. 23, 24, 27............. 58

Pennington, John, "The Death

Penalty: Have We Walked the

Last Mile?", Atlanta Journal

and Constitution, Aug. 30

and Sept. 6, 1970 . . . . . 75

OTHER AUTHORITIES— continued

X.

Perry and Cooper, Sources of

Our Liberties, American Bar

Foundation, 1959. . . . . . 85

Rutland, The Birth of the

Bill of Rights7^776^1791,

University of North Carolina

Press, 1955 ................ 75

Time, April 15, 1966, vol. 87,

p. 40. .................... . 50

United Nations, Department of

Economic and Social Affairs,

Capital Punishment (ST/SOA/

SD/9-10) (1968) .47

United States Department of

Justice, National Prisoner

statistics Number 44, August

1969, Table 15, p. 30. . . . 32,

56, 62

OTHER AUTHORITIES--continued

XX .

STATUTORY AND CONSTITUTIONAL

PROVISIONS

G a. code Ann. § 6-805(f) (Ga.

Laws 1965, pp. 18, 24) 10

Ga. code Ann. § 24-3005 (G a .

Laws 1889, p. 156; 1950, p.

427, 428) 94

Ga. code Ann. § 26-1001 (1969) 12

G a. code Ann. § 26-1003 (1969) 13

Ga. code Ann. § 26-1004 (1969) 12

Ga. code Ann. § 26-1101 (1969) 12

G a. code Ann. § 26-1901 and -1902

(1969) 55

G a. code Ann. § 26-3301 (Ga. Laws

1969, p . 741) 31

G a. code Ann. § 27-1502 (1933) 89

G a. code Ann. § 27-405 i(Ga. Laws

1962, p . 453, 454) 6

G a. code Ann. § 27-2514 (G a . Laws

1924, p . 195) 67, 76

G a. Code Ann. § 27-2515 (G a . Laws

1924, p . 196) 76

XIX .

Ga. Code Ann. § 27-2602-2604 (Ga.

Laws 1960, pp. 988, 989, Ga.

Laws 1874, p. 30) 92

Ga. code Ann. § 38-415 (Ga. Laws

1962, pp. 133-135) 6

Ga. Code Ann. 77-309(c)(d) (Ga.

Laws 1956, pp. 161, 171 as a-

mended) 66

Ga. Code Ann. 77-310(d)(Ga. Laws

1956, pp. 161, 173, as amended) 93

N. M. Stat. Ann. (1969 Cum.

Pocket Part) 40A-29-2.1 57

Official Compilation of the Rules

and Regulations of the State of

Georgia, Rules of the State

Board of Corrections, Sec. 125-

1-2-.05 75

Rules of the United States Supreme

Court, Rule 23(l)(f) 90

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

1971 Term

No. 69-5003

WILLIAM HENRY FURMAN,

Petitioner,

GEORGIA,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA

BRIEF OF RESPONDENT

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

In addition to the provisions recited

by Petitioner, this case involves also

certain Georgia statutes and published

Rules of the State of Georgia Board of

Corrections, each of which is set forth

2

as Appendix A to this Brief [herein

after cited as "App. A, pp. _____ ] at

App. A, pp. la - 16a infra.

QUESTION PRESENTED

"Does the imposition and car

rying out of the death penalty

in this case constitute cruel

and unusual punishment in vio

lation of the Eighth and Four

teenth Amendments?"

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

William Joseph Micke, Jr., age 29,

died on August 11, 1967, at his home

in Savannah, Georgia, as the result of

a bullet being shot through his lung and

producing severe hemorrhaging (A. 17,

18, 32). The unprovoked shooting oc

curred as follows: Micke and his wife

retired to bed sometime after midnight,

when he returned from his initial night

of work at a second job taken to supple

ment the family income. Mr. Micke's

primary employment was with the United

States Coast Guard (A. 18). The young

family included five children, ranging

in age from one year to fifteen years

(A. 17). Between 2:00 and 2:30 a.m.,

before falling asleep, the Mickes heard

noises and, thinking it was 11-year-old

Jimmie sleepwalking, Mr. Micke went to

get Jimmie back to bed (A. 18, 19).

3

Mrs. Mi eke, listening, heard her husband's

footsteps quicken. Then she heard a loud

sound and her husband's scream (A. 19).

Believing then that someone was in the

house because of Mr. Mieke's cry, and

fearful that someone else was also in the

house, and afraid that her children might

be harmed, Mrs. Micke ran to the bedrooms

for the children and gathered them into

her bedroom in an effort to protect them

(A. 19, 21, 22). She and the children

then screamed for their neighbor, she

realizing that she had no gun or other

means to defend against an intruder (A.

19, 22). She called the police as soon as

she saw Mr. Dozier, the neighbor, come out

of his house (A. 19), but her hysteria

prevented the police from learning what

the disturbance was (A. 24). Sergeant

Spivey, who was just one or two blocks

away from the Micke home when the call

came at about 2:23 a.m., went immediately

there and was met by Mr. Dozier out front

(A. 24, 26). They thought an intruder was

still in the house, so Sergeant Spivey

checked the front door and, finding it

locked, went around to the back door.

The back of the house was dark, and

when the officer tried the back door, it

opened (A. 24-25). Shining his flash

light into the house, he saw Mr. Micke’s

body lying on the floor with a large

puddle of blood around the head and

shoulder (A. 25). Still thinking there

4

was an intruder in the house, the officer

crawled through the rooms and found no one

other than Mrs. Micke and the children

locked in a front bedroom (A. 25). Upon

doubly checking Mr. Micke's vital signs.

Sergeant Spivey concluded that he was dead.

Other policemen arrived, an ambulance was

called, and an investigation begun (A. 26).

Officers Hall and Goode and others

immediately scanned the area in a search

for the assailant (A. 37, 41). Hall sta

tioned himself at the far end of a wood

ed area next to the Micke house, in his

patrol car with the lights off and motor

running (A. 38). Petitioner came out of

the woods and when he saw the patrol car,

he walked faster and then started to run

(A. 38-39). Hall and other officers pur

sued, finally on foot, and traced Peti

tioner 's tracks to the nearby home of his

uncle (A. 39). After obtaining the uncle's

permission to search the area, the officers

located Petitioner hiding under the house

and pulled him out by the hand (A. 39, 40,

41). A search was made of Petitioner

and a .22 caliber pistol, which was later

identified as having discharged the bullet

which killed Mr. Micke, was taken from his

right front pocket (A. 40-43, 49, 50;

R. Transcript 67-71). No other civilian

was seen out in the area during the course

of the search (A. 40).

5

Detective Smith testified (after a

voluntariness hearing before the court in

the absence of the jury and after the

court concluded that the statements were

not inadmissible on that account [A. 44,

46]), that on the same day and following

an explanation of Petitioner's rights to

him 1/ and his indication that he did not

then want a lawyer# the detective said he

had one question# which was: " . . . did

he get inside of the house" (A. 47).

Petitioner's reply# he said, was:

"A. He state yes, that he was

in the kitchen; the man come in

the kitchen, saw him in there

and attempted to grab him as he

went out the door; said the man

hit the door, instead of catching

him, he hit the door, the door

slammed between them, he turned

around and fired one shot and

ran." (A. 47).

The investigation at the Micke home,

commenced while Officers Hall and Goode

and others were searching for the assail

ant (A. 26, 29, 33, 37, 41) yielded

latent fingerprints on a washing machine

on the back porch which were later deter-

Officer Goode testified that his

constitutional rights were also read

to him upon arrest (A. 42).

1/

6

mined to have been made by Petitioner

(A. 28, 33, 37). The inch-thick ply

wood door which lead from the small

porch to the kitchen where Mr. Micke's

body was found, contained a bullet hole

(A. 27, 29), the appearance of which

indicated that the bullet came into the

house (A. 27, 30). Mrs. Micke testified

that the door had been locked (A. 20).

It appeared that the washing machine had

been pulled away from a window, a fan

moved, and the door unlocked on the inside

by slipping a hand through the window

(A. 20, 21, 27, 28, 31).

After the State presented its

case, Petitioner's counsel (who has been

counsel throughout the proceedings and up

to the present time) asked that the jury

be excused and that the defendant be

called to determine, on the record, whe

ther he then wished "to make a sworn or

unsworn statement or no statement at

all." (A. 50). This was done (A. 50) .2J

2/ Georgia law gives a criminal defendant

these three options. Ga. Laws 1962,p.453

Ga. Code Ann. § 27-405, App. A, p.

6 a. See also Ga. Laws 1962, pp.

133-135, Ga. Code Ann. § 38-415 and

-416.

7

Petitioner verified that his attorney

had discussed these three alternatives

with him and advised him in this regard,

and that it was his decision not to make

a statement (A. 51). After further ex

planation by the court and his attorney,

in which it was emphasized that he could

make either a sworn or an unsworn state

ment, the court asked: "Do you want to

tell this jury anything?" The defendant

then said, "Yes". (A. 52, 53). He reit

erated this desire before the jury, and

after his attorney instructed him to

"Give your name, your age and everything

else about you," the following transpired:

"The Defendant: William Henry Furman.

"Mr. Mayfield: Speak a little louder,

please.

"The Defendant: William Henry Fur

man. I am twenty-six. I work at

Superior Upholstery.

"Unidentified: Where?

"The Defendant: Superior Upholstery.

"Mr. Mayfield: Speak loud enough now

for everyone to hear you and hear

you clearly.

"The Defendant: They got me charged

with murder and I admit, I admit

8

going to these folks1 home and they

did caught me in there and I was com

ing back out, backing up and there

was a wire down there on the floor.

I was coming out backwards and fell

back and I didn't intend to kill no

body. I didn't know they was behind

the door. The gun went off and I

didn't know nothing about no murder

until they arrested me, and when the

gun went off I was down on the floor

and I got up and ran. That's all to

it.

"Mr. Mayfield: Now, do you have

anything else you want to tell this

jury about this case?

"The Defendant: Yes, sir, one other

thing; they didn't — questioned me

down there, down there at the police

station, they didn't told me nothing

about a lawyer and I told them who I

wanted as an attorney and they still

asked me questions and I wouldn't an

swer none. That's — that's all I've

got to say.

"Mr. Mayfield: Anything else you want

to say now?

"The Defendant" That's all.

"Mr. Mayfield: You may come down.

9

Note: (The defendant withdrew

from the witness stand.)" (A.

54-55).

Before the trial commenced, a motion

to suppress evidence was heard and denied,

a motion challenging the array of the jury

venire was submitted upon stipulation of

transcript from another case, and other

defense motions were made and denied (R.

8-15, Re Transcript 2, 2-a, 11A through

11 BE; A. 11, 12).

In obtaining a panel of forty-eight

qualified jurors, only one person was dis

qualified, and thus required replacement,

for answering that he would refuse to im

pose capital punishment in a case regard

less of the evidence (A. 12-15).

The trial was held on September 20,

1968 (A. 10), the homicide having occur

red on August 11, 1967 (A. 17). The

lapse of time was occasioned by defen

dant 1s attorney having moved for psychi

atric examination and evaluation at an

institution designated by the court and

at State expense so that the jury could

have the information in determining guilt

or innocence and proper punishment (A. 6 ).

On October 24, 1967, the court granted the

motion inadvertently referring to it as a

special plea of insanity, and ordered

defendant sent to Milledgeville (Central)

State Hospital for examination (A. 8 ).

10

By the terms of the order, the findings

were to be sent to the court, the solici

tor general, and defendant's counsel.

Defendant was returned to the court in

April, 1968, as being competent to stand

trial, it having been determined that he

was not psychotic, knew right from wrong,

and was able to cooperate with his coun

sel in preparing his defense (Petitioner's

Brief, Appendix B, p. 3b).

No further reference was made to any

insanity, either in terms of a defense or

in terms of being competent to stand trial.

Despite all of the pre-trial and post

trial activity which marks the course of

this case, the subject did not arise un

til after this Court granted certiorari

and preparations for the appendix began

(Petitioner's Brief, App. B, p. lb).

Contrary to the assertion putting the blame

for omission of the "reports" on the

trial court clerk, the law clearly im

poses this duty of perfecting the record

on the party contending the record is

incomplete, in this case,the Petitioner.

Ga. Laws 1965, pp. 18,24; Ga. Code Ann.

§ 6-805(f), App. A. p. la.

Respondent knows of no requirement that

the clerk include in the record more than

is recorded in his office.

The merits of the new assertions

regarding Petitioner's mental condition

are palpably suspect since, although

11

trial counsel pressed an appeal before

the Georgia Supreme Court and was thus

responsible for drawing up the enumera

tion of errors and supporting brief

based on the record, the absence of the

letters was not even noticed or thought

important enough to be made a part of

the record at that stage, as may be done

in accordance with appellate practice.

Ga. Laws 1964, pp. 18, 24, supra.

Petitioner, in his Statement of the

Case, refers to the characterization of

the crime given in the opinion of the

Georgia Supreme Court (Petitioner's

Brief, p. 6). That Court, in section

6 of its opinion (A. 67, 68), ruled that

the general grounds of the motion for

new trial 3/were not meritorious.

2/ That is, contentions that the

verdict was contrary to evidence and

without evidence to support it; that

the verdict was decidedly and

strongly against the weight of the

evidence; and that the verdict was

contrary to law and the principles

of justice and equity. See R. 20.

12

The reason was that the evidence was suf

ficient to show either implied malice 4/

or at least the death occurring in the

commission of a felony. .5/

Contrary to Petitioner's comment,

Georgia law at the time of his convic

tion, and still now, divides crimes of

homicide into three categories: murder

4 /

V

Ga. Code Ann. § 26-1004: "Implied

Malice. Malice shall be implied

where no considerable provocation

appears and where all the circum

stances of the killing show an

abandoned and malignant heart. Cobb,

783." This now comprises § 26-1101 (a)

of the Code of Georgia, effective

July 1, 1969. (Petitioner's Brief,

App. A, p. 4a)

Illustrated, as the Court notes, by

Williams v. State, 222 Ga. 208 (1966)

and Manor v. State, 223 Ga. 594(1967)

This type of murder is now defined in

the Criminal Code of Georgia, § 26-

1101(b). (Petitioner's Brief, App. A,

p. 4a).

Formerly Ga. Code Ann. § 26-1002,

now Criminal Code of Georgia §

26-1101. (Petitioner's Brief, App.

A, p. la, 4a).

y

13

voluntary manslaughter , and invol

untary manslaughter -§/. The Committee

Notes which accompany the new Criminal

Code of Georgia effective July 1, 1969,

discusses the decision not to divide the

offense of murder into degrees:

"An examination of murder legisla

tion in operation in 30 States

discloses that six jurisdictions

(Illinois, Louisiana, Mississippi,

Oklahoma, South Carolina, and

Texas) follow the Georgia pattern

of dividing homicide into murder,

voluntary, and involuntary man

slaughter, with separate defini

tions of these offenses. The

remaining 24 States, approximately

80 % of the jurisdictions studied,

in addition to having statutes deal

ing manslaughter, divide murder

into degrees for purposes of pro

secution and punishment. . . .

* * *

7 /

Formerly Ga. Code Ann. § 26-1002,

now in Criminal Code of Georgia,

§ 26-1101.(Petitioner 1s Brief,

8/ APP* PP* la, 4a).

Formerly Ga. Code Ann. § 26-1009,

now in Criminal Code of Georgia,

§ 26-1103. (Petitioner1s Brief,

App. A, pp. 2a, 4a).

14

"While more than three-fourths of

the States divide the offense of

murder into degrees, primarily to

facilitate punishment, Georgia has

always followed the common-law

view of a single definition.

Illinois and Louisiana, which have

recently enacted criminal Code

legislation, have adopted the de

finitional classification of homi

cide similar to the method presently

employed in Georgia. The Model

Penal Code Proposed Official Draft

approves and utilizes the single

definition (Section 201.2)."

Committee Notes, Criminal Code of

Georgia, 1970 Revision, p. 84.

Thus, Georgia submits to the jury

trying the case the discretion to fix the

punishment at death in a murder case, and

does not limit its consideration by classi

fications of degree. The value of any

life ended by murder is thus given the

same weight insofar as the maximum penalty

imposeable is concerned. The myriad of

variables attendant to each case is left

to consideration of the jury, represent

ing the community, as to which murder

cases appropriately call for the death

penalty.

Petitioner states, as a footnote,

his Amended Motion for New Trial chal

lenged a certain jury instruction re

15

garding felony murder (Petitioner's Brief

p. 7, fn. 4). He did not object to the

instruction when given (A. 64).

He states that he incorporated the

challenge by reference into the Enumera

tion of Errors which formed the basis of

appeal to the Georgia Supreme Court, but

it appears there only thusly:

"7. That the Court erred in one

and all of the respects set out in

the amended Motion for New Trial and

for the reasons set forth thereon."

Enumeration of Errors dated March 27,

1969, p. 2 (Not paginated in origi

nal record in this Court and not

included in printed Appendix.).

The Supreme Court of Georgia does not con

sider enumerations not briefed or argued.

Schmid v.State, 226 Ga. 70 (1970). And

it is abundantly evident that Petitioner

did not assert the matter below at all,

as at the conclusion of the Georgia

Supreme Court's opinion, it is stated:

"7. Having considered every

enumeration of error argued by

counsel in his brief and find

ing no reversible error, the

judgment is Affirmed.11 (A. 68).

Consequently, Petitioner can raise no

inference or implication that any issue

in this regard was properly raised.

16

Petitioner refers to "additional

facts" concerning him which the jury did

not know but which "appear in the record"

(Petitioner's Brief, pp. 8-9). That

these "facts" are not a part of the record

and were not a part of the record before

the court below has already been pointed

out. It is further noted that the

"facts" alluded to, i.e., results of

psychiatric examination, were fully

available for disclosure to the jury,

had Petitioner's counsel deemed it favor

able to the defendant to make such a

revelation. The letters are dated

February 28, 1968, and April 15, 1968

(Petitioner's Brief, App. B, pp. 2b and

3b), long before the trial on September

20, 1968, and it is obvious from their

content that defense counsel would not

have chosen to make the jury aware of

their substance. There is no basis what

soever for Petitioner's bald statement

that the two letters "indicate that

Petitioner Furman is both mentally

deficient and mentally ill."

(Petitioner's Brief, p. 9). The lately

contrived "issue" of insanity is further

dealt with in this Argument, infra, p. 88 et

The facts concerning the same are simply

recited here, in refutation of Petitioner's

erroneous Statement of the Case in this

regard.

Contrary to Petitioner's statement,

he was not "committed" to Central State

Hospital upon a special plea of insanity.

17

There was no such special plea of insan

ity, which would have ultimately required

a jury determination of competency to

stand trial, such as occurred in Jackson's

case. See Jackson v. Georgia, No.

69-5030, A. 12, 13, 17, 18, 21, 33.

Instead, counsel simply moved for psy

chiatric examination, at State expense,

to be used for purposes of defense and

possibly for sentencing (A. 6). As

indicated heretofore, the court in

granting the motion inadvertently

referred to it as a plea of insanity,

but none was ever filed nor did counsel

ever make any issue of competency to

stand trial.

Petitioner also asserts an erroneous

conclusion regarding the meaning of the

second letter: the Hospital did not re

port on April 15, 1968, that he was THEN

diagnosed identically as he had been diag

nosed on February 28. Instead, the letter

merely repeated the earlier diagnosis as

having at one time been made, and it then

goes on to say that the present condition

is different. There is no basis for con

cluding, as Petitioner inferredly attempts

to, that the Hospital deliberately sent

back for trial a man who had some mental

condition which should have legally avoid

ed trial and sentencing.

18

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

THE IMPOSITION AND CARRYING OUT

OF THE DEATH PENALTY IN THIS

CASE DOES NOT CONSTITUTE CRUEL

AND UNUSUAL PUNISHMENT IN VIOLA

TION OF THE EIGHTH AND FOURTEENTH

AMENDMENTS.

The Fourteenth Amendment, by virtue

of which cruel and unusual punishment for

bidden by the Eighth Amendment is a pro

hibition against the states, provides

that the states may not deprive any per

son of life without due process of law.

Conversely, the states may deprive a

person of life so long as the mandates of

due process of law are observed. The

Eighth Amendment, adopted as part of a

declaration of rights to confine the

federal government, may not effect a

curtailment of a right of the states

recognized by the states-restricting

Fourteenth Amendment.

The Eighth Amendment does not pro

hibit the penalty of death for crime,

in that such a penalty was historically

acceptable in the context of the period

in which the Amendment was adopted,

has thereafter traditionally been a

part of the penal system in this country,

and is widely accepted today as a rea

sonable, rational, and appropriate

19

instrument in the control of crime. it

is not a punishment that is prohibited as

constitutionally "cruel and unusual."

The function of State legislatures to

define crimes and fix punishments is

therefore not restricted against providing

such a punishment.

This case is devoid of any issue

concerning the sanity of Petitioner.

There is no constitutional barrier

to the imposition and carrying out of

the death penalty in the case at bar.

20

ARGUMENT

I

THE DEATH PENALTY FOR MURDER

IS NOT PER SE CRUEL AND UN

USUAL, IN THE CONSTITUTIONAL

SENSE, AND IS THEREFORE NOT A

DEPRIVATION BY THE STATE OF

PETITIONER FURMAN'S LIFE WITH

OUT DUE PROCESS OF LAW.

The Court has framed the question for

examination to be, whether the imposition

and carrying out of the death penalty in

Furman's case constitutes cruel and un

usual punishment in violation of the

Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments. Peti

tioner contends that his sentence is a

rare, random, and arbitrary infliction

and for that reason is prohibited by

the Eighth Amendment principles briefed

in Aikens v. California, No. 68-5027.

He states therein that the Due Process

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment is

"involved" 2/, but he makes little or

no reference to it thereafter, travel

ing instead on the assumption that the

Eighth Amendment is incorporated into

the Due Process Claiise and so it need

9/ Aikens Brief, p. 2.

21

only be examined in terms of the former.

However, since the Eighth Amendment is

not, alone, applicable to the States

and was not applicable to them in any

sense before the adoption of the Four

teenth Amendment in 1868, the question

at issue must be reviewed in the context

of the latter's requirements. The

Eighth Amendment imposes no restrictions

on the States, but the Fourteenth Amend

ment does. The Due Process requirements

will therefore be developed as the appro

priate arena in which to focus on the

cruel and unusual punishment question.

The Fourteenth Amendment Due Pro

cess Clause guarantees:

"(N)or shall any State deprive

any person of life, liberty or

property without due process of

law; . . . " (Emphasis added).

It does not prohibit a State from

depriving a person of life, but rather

the prohibition is that it shall not be

done without due process of law. Thus,

the Nation saw fit, one hundred years ago,

to give constitutiqnal permanence to the

right of every person to demand due pro

cess before his life could be forfeited

by the State. The mandates of this

clause, in terms of cruel and unusual

punishment, has been stated variously:

2 2

In Ex parte Kemmler, 136 U.S. 436 (1890)

the Court explained:

"[I]n the Fourteenth Amendment,

the same words [due process of

law] refer to that law of the

land in each State, which derives

its authority from the inherent

and reserved powers of the State,

exerted within the limits of

those fundamental principles of

liberty and justice which lie

at the base of all our civil and

political institutions. Undoubt

edly the Amendment forbids any

arbitrary deprivation of life,

liberty or property, and secures

equal protection to all under like

circumstances in the enjoyment of

their rights; and in the adminis

tration of criminal justice re

quires that no different or higher

punishment shall be imposed upon

one than is imposed upon all for

like offenses. But it [the Four

teenth Amendment] was not designed

to interfere with the power of

the State to protect the lives,

liberties and property of its

citizens, and to promote their

health, peace, morals, education

and good order." I_d. at 448.

Kemmler complained that the form of

the death penalty, electrocution, was

23

cruel and unusual and therefore a depri

vation of life without due process of

law. The Court concluded that in order

to reverse the New York highest court,

it would " . . . be compelled to hold

that it had committed an error so gross

as to amount in law to a denial by the

State of due process of law to one ac

cused of crime." id. at 448. Peti

tioner's complaint faces the same test

because in order to prevail, it, too,

must evidence a denial of substantive

due process: whereas Kemmler challenged

the form of infliction, i.e ., electro

cution itself, rather than the procedure

for inflicting it, Petitioner chal

lenges the punishment, i.e., the death

penalty, itself, rather than the proce

dure by which it was imposed on him.

In Louisiana ex rel. Francis v.

Resweber, 329 U.S. 459 (1947), the

circumstances of execution were com

plained of as cruel and unusual punish

ment. Thus, procedural due process was

the frame. Mr. Justice Frankfurter

developed the concept of the due pro

cess safeguard in a concurring opinion

and said it is part of "the conceptions

of justice and freedom by a progressive

society." Id., at 467.

"The Fourteenth Amendment,” he

wrote, "did mean to withdraw

from the States the right to

24

act in ways that are offensive to

a decent respect for the dignity

of man, and heedless of his free-

dom. " Id,, at 468.

"In short," he continued, "the

Due Process Clause of the Four

teenth Amendment did not withdraw

the freedom of a State to enforce

its own notions of fairness in the

administration of criminal justice

unless, as it was put for the Court

by Mr. Justice Cardozo, 'in so doing

it offends some principle of justice

so rooted in the traditions and con

science of our people as to be ranked

as fundamental.'" I_d. at 469.

This context, then, is the proper

one in which the Court is to review

State penal laws, with respect to whether

they are cruel and unusual. The question

of the moment is whether the death penalty

offends some principle of justice so

rooted in the traditions and conscience

of our people as to be ranked as funda

mental. This test looks to the solid past

as well a constitutional inquiry should,

rather than simply to the shifting pre

sent, which Petitioner presses with his

emphasis on a test of "evolving standards.

Measured by this due process test,

it is indisputable that the death penalty

for crimes which immediately endanger or

25

take life does not offend a rooted prin

ciple of justice. The existence and

application of the death penalty itself

has been an integral part of our penal

systems since at least Colonial days,

although, as Justice Burton pointed out

in dissent in the Louisiana case, tor

turous means and forms of inflicting

death is prohibited as shocking funda

mental instincts of civilized man.

Id. at 473.

Since due process standards are very

broadly conceived, Mr. Justice Frank

furter cautioned, "great tolerance toward

a State's conduct is demanded of this

Court." _Id. at 470. The State does not

assert that its position in this case

cannot be maintained without a great

tolerance being shown by the Court, but

rather points up this concept to illus

trate the foreshortened framework of

Petitioner's premise.

Although Solesbee v. Balkcom, 339

U.S. 9 (1950) is not a punishment case,

it involves an application of the Due

Process Clause. The question was whether

the method applied by Georgia to deter

mine the sanity of a convicted defendant

offended due process. The Court held

that the statute as applied did not do so.

Mr. Justice Frankfurter, who dissented,

again exhaustively reviewed the meaning of

the Due Process Clause. The rule against

26

executing an insane person is "protected

by substantive aspects of due process,"

he noted. (Id. at 24). This conclusion

followed from an application of the sub

stantive aspect of due process, which

was phrased thusly:

"It is now the settled doc

trine of this Court that the

Due Process Clause embodies a

system of rights based on moral

principles so deeply embedded in

the traditions and feelings of

our people as to be deemed funda

mental to a civilized society

as conceived by our whole history."

Id. at 16.

* * *

"In applying such a large, un-

technical concept as 'due pro

cess,' the Court enforces those

permanent and pervasive feelings

of our society as to which there

is compelling evidence of the

kind relevant to judgments on

social institutions." Id. at 16.

The distinction between substan

tive and procedural due process which

was there made was that substantive

due process prohibited killing an in

sane man, whereas procedural due pro

cess required that where a question of

27

sanity arises, the prisoner must be

given the opportunity to show that he is

otherwise. This distinction illustrates

that Petitioner's argument, as embodied

in the Aikens Brief, must be construed

to be that the death penalty violates

substantive due process, because the

theory is that any execution actually

inflicted in our contemporary society

would be unconstitutional.

Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86 (1958)

is strictly an Eighth Amendment case

because of its federal character. Due

process considerations did not enter

in. Therefore, Petitioner's lifting

of the test suggested in that case and

his primary reliance thereon distorts the

question in this case. Its adaptability

to the present situation must be circum

scribed by the superimposition of the

broad limits in which due process allows

the States to operate.

Petitioner, moreover, makes the Trop

test unworkable in a judicial setting by

construing it narrowly. The evolving

standards of decency, he says, are ones

which are current and can be measured by

contemporary statistics and public

opinion indicators and world-wide

"trends". Such a close-to-pocket con

struction of the Trop language not only

fails to take into account the changes

of tomorrow but refuses to acknowledge

28

the judicial setting in which it must

be applied. Petitioner's brief is

replete with partial statistics, as

sertions of unconfrontable "experts",

and all types of "objective indicators"

which allow not of cross-examination

and which are not subject to the rules

of evidence. It is submitted that the

standards intended by the statement that

"the [Eighth] Amendment must draw its

meaning from the evolving standards of

decency that mark the progress of a

maturing society" -i2/ are standards of

fundamental significance and capable

of demonstration to a judicial body that

is confined to the evidence in the record

of a case and is not equipped with the

facilities for factual investigation and

the gathering of conflicting evidence

which a legislative body would have. The

scope and magnitude of the "evidence"

proffered by Petitioner itself bespeaks

an attempt that would more fittingly be

directed to a legislature. The Court,

as a matter of fact, has on more than

one occasion with respect to penalties,

pointed this out: see dissent of Mr.

Justice White, concurred in by Mr.

Justice Holmes, in Weems v. United

States, 217 U.S. 349, 384 (1910); dis-

10/ 356 U.S. at 101.

29

sent of Mr. Justice Clark in Robins on

v. California, 370 U.S. 660, 682, 683

(1962); dissent of Mr. Justice White in

Robinson v. California, supra, 370 U.S.

at 689. At the least, the Court has

taken cognizance of the comprehensive

task involved in reaching the conclusion

that a legislatively defined crime or

legislatively fixed punishment is uncon

stitutional :

"And for the proper exercise of

such power [judicial power to judge

the exercise of legislative power]

there must be a comprehension of

all that the legislature did or

could take into account, -- that

is, a consideration of the mischief

and the remedy." Weems v. United

States, supra, 217 U.S. at 379.

The standard, then, is the much broader

one implicit in "the dignity of man"; it

requires only that the power to punish "be

exercised within the limits of civilized

standards". Trop v. Dulles, supra, 356

U.S. at 100. The overriding applicability of

the Fourteenth Amendment due process con

cept, which was absent in the Trop and

Weems tests, is present in Robinson v.

California, supra, 370 U.S. 660 (1962).

There the Court concluded that it was

"doubtless" that a law which made a crim

inal offense of a disease would universal

ly be thought to be cruel and unusual

30

punishment in violation of the Eighth

and Fourteenth Amendments, -ii/ The

fundamental character of the condemna

tion is therefore the gauge.

The narrow construction which Peti

tioner puts on "contemporary human know

ledge", "public opinion enlightened by

humane justice", and "evolving standards

of decency that mark the progress of a

maturing society", also falls prey to one

of his own arguments. The United States

Constitution is, to be sure, a vital

organ which must be interpreted with

deference to its elastic nature. This

does not mean, however, that it may be

construed solely to fit today's needs,

desires and best judgment. That is

employment more appropriate to laws,

which can be made today and changed, modi

fied, altered, amended, or repealed

tomorrow. Laws can be experimented

with. But the Constitution remains as it

stands, subject only to infrequent and

difficult-to-achieve amendment. If the

Court were to construe the foundation

document in terms of current world or

national opinion, and assuming for the

sake of argument that Petitioner has

demonstrated total contemporary rejection

11/ 370 U.S. at 666.

31

of the death penalty, the constitutional

invalidation of capital punishment would

remove it foreover as a penal sanction in

this country, absent constitutional

amendment.

Such finality should not be imposed

when it has not been shown that the death

penalty serves no legitimate purpose and,

even more importantly, when no one can

yet imagine the types or magnitudes of

crimes that will surely evolve in future

generations. Who, for example, envi

sioned twenty years ago that our society

plagued with gun-point airplane high

jacking, would find it necessary to define

a new crime, commonly referred to as

"skyjacking", and provide as a maximum

the death penalty? A2/ Who today can

imagine the new and more broadly sweeping

crimes that can evolve in the increasingly

complex, mobile, speeding, technological,

interdependent society in which we live?

It is all too well known that the flip of

a switch can destroy millions. As the

Court succinctly stated in Weems v. United

States, 217 U.S. 349 (1910):

12/ See Ga. Laws 1969, p. 741; Criminal

Code of Georgia § 26-3301. (App. A,

p. 5) .

32

"The future is their (constitution's)

care, and provision for events of

good and bad tendencies of which no

prophecy can be made. In the appli

cation of a constitution, therefore,

our contemplation cannot be only of

what has been, but of what may be."

Id. at 373.

Note also that this statement immedi

ately succeeds the Court's observation

that the death penalty was not meant to

be excluded by the Eighth Amendment pro

hibition.

The penalty here sought to be out

lawed should be abolished by the law

makers, if such a penalty is currently

unacceptable as Petitioner says. Then,

if ever again thought useful or necessary,

it could likewise be reinstated. Ex

perience would then provide a knowledge

able guideline by a number of states

which at one time elected to abolish the

penalty. -=-=/ But to ban it as a matter

of constitutional imperative is not only

unjustified in terms of its present posture

but is also dangerous in terms of its

future use. As it was pointed out on pre-

13/ United States Department of Justice,

National Prisoner Statistics Bulletin,

Number 45# August, 1969, Table 15, p.

30 [hereinafter cited as NPS] .

33

vious occasions, the power of the

legislature to define crimes and their

punishment must yield only to a consti

tutional prohibition;

"The function of the legislature

is primary, its exercise fortified

by presumptions of right and legal

ity, and is not to be interferred

with lightly, nor by any judicial

conception of its wisdom or propriety.

They have no limitation, we repeat,

but constitutional ones, and what

those are the judiciary must judge.

We have expressed these elementary

truths to avoid the misapprehension

that we do not recognize to the ful

lest the wide range of power that

the legislature possesses to adapt

its penal laws to conditions as they

may exist, and punish the crimes of

men according to their forms and fre

quency." Weems v. United States,

supra, 217 U.S. at 379.

The sane principle is reiterated in

Trop v. Dulles, supra, 356 U.S. at 103:

"Courts must not consider the

wisdom of statutes but neither

can they sanction as being merely

unwise that which the Constitution

forbids."

34

And more recently in McGautha v. California,

402 U.S. 183 (1971):

"Our function is not to impose on

the States, ex cathedra, what might

seem to us a better system for deal

ing with capital cases. Rather it

is to decide whether the Federal Con

stitution proscribes the present pro

cedures of these two States in such

cases." Id. at 195 .

In the instant case, the antagonist

to the traditional penalty has not only

failed to show that it is constitutionally

forbidden but even that it is unwise.

Fundamental requirements of fairness and

decency are ^hat the Due Process Clause

embodies, — and it is that bedrock

standard which Petitioner must show

capital punishment contravenes. It is

abundantly evident that he has not proved

his case.

Emphasis has been given to the due

process setting in which the claim of

cruel and unusual punishment must be

viewed. This is not to deny that judi

cial measurements of Eighth Amendment cruel

and unusual punishment are not to be

applied. Indeed they are, as is illus-

14/ McGautha v. California, supra

402 U.S. at 215.

35

trated by at least as early a case as

Louisiana ex rel. Francis v. Resweber,

supra, 329 U.S. at 463 (1947)-

The test of whether punishment is

cruel and unusual in the constitutional

sense has been variously stated in dif

fering circumstances. In attempting to

ascertain the meaning of the Eighth

Amendment clause in the federal case of

Wilkerson v. Utah, 99 U.S. 130 (1879),

the Court in part measured the mode of

execution by the proposition that the

Constitution forbids punishments of

torture and all others in the same line

of unnecessary cruelty. In that regard,

death by electrocution does not fail the

test. Ex Parte Kemmler, supra. Even

Petitioner concedes as much. .15/

"Punishments are cruel", the Court

said in Kemmler, "when they involve tor

ture or a lingering death; . . . some

thing inhuman and barbarous . . . "

Ex parte Kemmler, supra, 136 U.S. at 447.

15/ Aikens Brief, App. I, p. 9i:

"Under correct application," elec

trocution "insures a death that is

both instantaneous and painless."

36

The meaning of cruel and unusual

punishment was subsequently expanded and

liberalized to cover a broader spectrum.

Mr. Justice Field, in dissent in 0 1 Neil

v. Vermont, 144 U.S. 323 (1892), pre

cursed the concept that the inhibition

is directed not only against punishments

of a torturous character, "but against

all punishments which by their excessive

length or severity are greatly dispro-

portioned to the offenses charged."

Id. at 340. The punishment imposed in

that case was, in Field's opinion, "a

punishment at the severity of which, con

sidering the offenses, it is hard to

believe that any man of right feeling

and heart can refrain from shuddering."

Id. at 340. So measured, the punishment

which has over the past several years

been imposed by juries to at least most,

if not all, of the approximately 660 per

sons now under death penalty in this

country, cannot be said to be excessive

in terms of the right feeling and heart

of any man.

The Court in Howard v. Fleming,

191 U.S. 126 (1903) declined to set out

a rule for determining what punishment

is cruel and unusual or under what cir

cumstances the Court would interfere

with the decision of a state court in

respect thereto. Reference was made

instead to Ex parte Kemmler, supra.

37

The Court did say, however, that "Undue

leniency in one case does not transform

a reasonable punishment in another case

to a cruel one." Howard v. Fleming, supra,

191 U.S. at 136. By that measurement,

the penalty in the cases sub judice will

stand.

The excessiveness concept outlined

by Mr. Justice Field in O'Neil., supra,

was applied in Weems v. United States,

217 U.S. 349 (1910). After reviewing

the history of the cruel and unusual

punishment clause and the judicial pro

nouncements concerning it, the Court

concluded that the punishment provided

by statute in Weems was cruel in its

excess and unusual in its character.

Thus, because of its degree and because

of its kind, it was deemed invalid.

Petitioner here, too, challenges the

statutory punishment itself, rather than

merely its application in his case. He

says in effect that it is per' se cruel

and unusual. He assumes that it is

"cruel" and directs his attention to an

attempt at showing that it is also

"unusual."

But is the death penalty excessive,

that is, cruel, per se for murder and

other crimes that take, or clearly and

presently endanger, innocent life?

It is inconceivable that in our system

of justice the victim should be compelled

38

to suffer more than the attacker. The

death penalty has always been regarded

by this Court as constitutionally al

lowable as a punishment:

"Punishments are cruel when they

involve torture or a lingering

death; but the punishment of death

is not cruel within the meaning of

that word as used in the Constitu

tion. It implies there something

inhuman and barbarous, and some

thing more than the mere extin

guishment of life." Ex parte

Kemmler, supra, 136 U.S. at 447.

Lest there be any doubt as to the

meaning of that statement, the Court in

Weems, supra, 217 U.S. at 370-371, ex

plained:

"It was not meant in the language

we have quoted to give a comprehen

sive definition of cruel and un

usual punishment, but only to ex

plain the application of the pro

vision to the punishment of death.

In other words, to describe what

might make the punishment of death

cruel and unusual, though of itself

it is not so."

Mr. Justice Burton repeated this pre

cept with approval in his dissent in

Louisiana ex rel. Francis v. Resweber,

39

supra, 329 U.S. at 463, footnote 4.

More recently it was said:

"At the outset, let us put to

one side the death penalty as an

index of the constitutional limit

on punishment. Whatever the argu

ments may be against capital

punishment, both on moral grounds

and in terms of accomplishing the

purposes of punishment— and they

are forceful— -the death penalty

has been employed throughout

history, and, in a day when it

is still widely accepted, it can

not be said to violate the consti

tutional concept of cruelty." Trop

v. Dulles, supra, 356 U.S. at 99.

Mr. Justice Black' s concurring opinion in

McGautha v. California, supra, makes it

plain:

"The Eighth Amendment forbids

'cruel and unusual punishments.'

In my view, these words cannot

be read to outlaw capital punish

ment because that penalty was in

common use and authorized by law

here and in the countries from

which our ancestors came at the time

the Amendment was adopted. It is

inconceivable to me that the

Framers intended to end capital

punishment by the Amendment. Al

though some people have urged that

40

this Court should amend the Consti

tution by interpretation to keep it

abreast of modern ideas, I have

never believed that lifetime judges

in our system have any such legis

lative power. See Harper v.

Virginia Board of Elections, 383

U.S. 663, 670 (1966) (Black, J.,

dissenting)." Id. at 226.

It is not pretended that previous

pronouncements foreclose the question.

However, the consistent views expressed

over the years by this Court on this

subject illustrate that the death penalty

is not an unacceptable punishment. It

cannot be said that these views do not

give expression to that common standard

of decency required of punishment in our

society by humane justice, or that they

must be abandoned because contemporary

human knowledge has rendered the death

penalty constitutionally "unusual".

Returning to the meaning of the

cruel and unusual punishment clause and

its previous construction by this Court,

which serves to instruct as to its

appropriate application in this case,

the Weems definition was reiterated in

the later federal case of Trop v. Dulles,

supra, 356 U.S. at 100. The Eighth

Amendment merely circumscribes the power

to punish so that it does not exceed

"the limits of civilized standards."

41

Id. at 100. The punishment of dena

tionalization for even a minor deser

tion in wartime was found to exceed

these limits because it destroyed the

political existence of the individual

and his right to have rights. It was

found to be excessive, contrary to "the

dignity of man." The death penalty,

when so measured, withstands the test.

Execution is a traditional penalty which

may be imposed depending on the enormity

of the crime, the Court in Trop noted.

Id. at 100. It is submitted that the

Petitioner has failed to carry his

burden of showing that the death penalty

is no longer clothed with validity.

His primary assertion is that capital

punishment has now become unusual in a

constitutional sense because of the

rarity of actual execution, and that

that rarity proves its unacceptability

in terms of "evolving standards of

decency." The failure of his proofs to

substantiate his claim is demonstrated

subsequently.

"Unusual”, that aspect of the clause

to which Petitioner directs the weight

of his argument, was given particular

attention in footnote 32 of the Trop

decision. Without concluding whether the

word "unusual" should be given an inde

pendent meaning, it was observed that

the Court:

42

" . . . simply examines the

particular punishment involved

in light of the basic prohibi

tion against inhuman treatment,

without regard to any subtle

ties of meaning that might be

latent in the word 'unusual.'"

Going on, the Court suggested that:

"If the word 'unusual' is to

have any meaning apart from

the word 'cruel', however, the

meaning should be the ordinary

one, signifying something dif

ferent from that which is gen

erally done."

And why did the Court regard denational

ization as "unusual" in this sense? Be

cause:

"[i]t was never explicity sanc

tioned by this Government until

1940 and never tested against the

Constitution until this day."

Trop v. Dulles, supra, 356 U.S.

at 100, fn. 32.

The death penalty on the other hand,

has always been sanctioned in this country

and is still sanctioned by the vast major

ity of jurisdictions here. It was such

an integral part of the penal system

when the Amendment was adopted that there

43

was not even a question so far as

Respondent can find, in Congress or in

any of the State legislatures to which

it was sent for ratification, as to

whether that Amendment conceivably ex

cluded the death penalty. And as to its

testing against the Constitution, it

would appear that the question would have

come up prior to this almost 200th year

of our national history, if it had been

regarded as debatable.

The "contemporary human knowledge"

test which Petitioner extracts from

Robinson v. California, supra, must be

examined in its context in order to be

a reliable guide in the present action.

The Court said:

"It is unlikely that any State

at this moment in history would

attempt to make it a criminal

offense for a person to be men

tally ill, or a leper, or to be

afflicted with a venereal dis

ease. A State might determine

that the general health and wel

fare require that the victims of

these and other human afflic

tions be dealt with by compul

sory treatment, involving

quarantine, confinement, or

sequestration. But, in the

44

light of contemporary human

knowledge, a law which made a

criminal offense of such a dis

ease would doubtless be univer

sally thought to be an infliction

of cruel and unusual punishment

in violation of the Eighth and

Fourteenth Amendments. See

Louisiana ex rel. Francis v.

Resweber, 329 U.S. 459, . .

Id. at 566.

Thus, the Court considered the penalty

to be so grossly antagonistic to contem

porary human knowledge that universal

thought would "doubtless" regard it as

violative of the Eighth and Fourteenth

Amendments. The same degree of attitude

or opinion is not present in terms of

capital punishment. Even Petitioner's

statistics show that there is no "univer

sal thought" in this country on its

validity in the constitutional sense, or

that such thought is "doubtless" a

condemnatory one.

II

45

THE "INDICATORS" OF UNACCEP

TABILITY OF DEATH AS A PENALTY

ARE NOT RELIABLE YARDSTICKS,

ARE NOT RELEVANT OR APPROPRIATE

YARDSTICKS, AND DO NOT PROVIDE

ACCURATE MEASURES FOR DETER

MINING THAT STANDARD OF DECENCY

BEYOND WHICH STATES MAY NOT GO

IN FIXING PUNISHMENT.

It has been demonstrated that the

antagonist has failed to take into

account the due process aspect of the

question before the court, and the

perimeters of that aspect have been

explained. it has also been pointed

out that the interpretation by the

antagonist, of the tests heretofore

enunciated and applied by this Court

in construing the "cruel and unusual

punishment" prohibition, has been too

narrow and has sought to restrict the

Court to a simplq present pulse-taking.

A proper perspective of the question

would sustain the punishment imposed,

when history, experience, and purpose

are scrutinized within the light of

present knowledge. Leave that for

the moment, however, and turn to the

"proof" which Petitioner offers. it

fails even the tests which he has

proposed; that is, it fails to show

that the standard which he has out

lined is not being met by the State.

46

The premise which Petitioner

attempts to prove, and whigh he says

spells the doom of capital' punish

ment, is that the death penalty has

a fatal characteristic, i.e., "extreme

contemporary rarity resulting from a

demonstrable historical movement which

can only be interpreted fairly as a

mounting and today virtually universal

repudiation." 23—/ The following

objective indicia, he asserts, all

point to unacceptability by contem

porary standards:

(1) The suggestion is made that

there is a world-wide trend towards

disuse for civilian crime, a de_ facto

abolition.

Firstly, by excluding military

crimes from discussion, Petitioner

attempts to artificially limit the

scope of the Eighth Amendment which,

as exemplified by its application to

wartime desertion in the case of Trop

v. Dulles, supra, admits of no such

restriction. What this distortion

does is allow the argument to be made

that the death penalty has been

"abolished" in many countries. Peti

tioner has failed to point out that

13/ Aikens Brief, p. 12.

47

it has been almost universally

retained for war-time crimes or

treason. 12— / The legislative

restrictions on the use of the

death penalty in this and other

countries certainly do not

constitute "abolition". It

presents rather a matter of degree.

Thus the moral and legal absolutes

presented in Petitioner's Brief

are hedged, he having excluded at

the outset an entire class of crimes

the inclusion of which would weaken

his argument. Petitioner has tacitly

admitted by this exclusion that the

death penalty has not been outlawed

but has at the most been restricted.

It is highly questionable,

secondly, whether the international

picture is an appropriate measure

of whether a State has contravened

our Federal Constitution. Although

the court in Trop took cognizance

of the non-acceptability by civilized

iZ/ United Nations, Department of

Economic and Social Affairs,

Capital Punishment (ST/SOA/

SD/9-10) (1968).

48

nations of the world of statelessness

as a punishment for crime, the penalty

of denationalization in that case was

of a peculiarly international character

and involved the international political

status of the person. Thus, the law of

other nations was uniquely pertinent.

It is not so with the penalty of death,

which does not involve an individual's

citizenship relationship with his

country or others. The same Trop

opinion, moreover, comments on the death

penalty in terms of "our", meaning our

Nation's, history.

It was to the States that Mr.

Justice Frankfurter looked in Solesbee

v. Balkcom, 339 U.S. 9 (1950). In the

dissent he tested the due process

problem:

"The manner in which the States

have dealt with this problem

furnishes a fair reflex, for

purposes of the Due Process

Clause, of the underlying feel

ings of our society about the

treatment of persons who

become insane while under

sentence of death." id. at 21.

in Weems v. United States, supra,

217 U.S. at 380-381, the Court compared

the Philippine punishment, for Eighth

Amendment purposes, only with the law of

49

the United States and with other punish

ments in the Philippines.

Further, Petitioner cites no

authority for the proposition that

the Framers intended the test of

"cruel and unusual punishment" to be

a poll-taking of other countries1 use

of a particular punishment. It is un

likely that such a concept was envi

sioned.

And it cannot be said that the

reports cited by Petitioner 23/ indi

cate a world-wide repudiation of such

certainty that the death penalty contra

venes the very dignity of man. Great

Britain only abolished it after a trial

period which indicates its own hesitancy,

and Canada is still undergoing a five-

year experiment that will expire unless

affirmatively acted on by its Parlia

ment. 23/ Such built-in vacillation

23/ Aikens Brief, p. 27, fn. 46.

23/ See report of the "Limitation of

Death Penalty in Canada" by J. R.

Mutchmor, Christian Century, Janu

ary 24, 1968, Vol. 85, page 120.

Just prior to the enactment of the

experimental abolition in Canada,

the death penalty was retained by

(continued on next page)

50

by the two countries whose underlying

philosophies are most closely allied

with our own refutes the implication

that our country alone remains barbaric

In addition, the circumstances of

other countries may indeed permit them

to abolish the death penalty; their

crime rates and penal facilities, their

systems of criminal law and their under

lying concepts of crime, themselves un

doubtedly each affected the decision to

abolish. Thus, the mere number of such

foreign countries have no effect on the

constitutionality of what, in most of

these United States, is regarded as a

legitimate and needed penalty for crime

(2) The Petitioner alleges that

the countries have abandoned capital

punishment because of their concern

with fundamental human decency, which

he says is illustrated by an intense

concern of religious groups, a crusade

fervor with which the forces against

the death penalty have moved, and anti

a vote of 143 to 112 despite

the fact that Prime Minister

Lester Pearson and the leaders of

all other major parties favored

abolishing it. "Time", April 15,

1966, Volume 87, page 40.

51

capital punishment opinions of highly

respected persons. Bedau lists

examples of literature stating the

case for capital punishment. 25/

The "objective indicator" which

is thus put forth is merely contrived

as a bald conclusion. Without a

careful study of the circumstances

under which a foreign country designed

to discontinue use of the death penalty,

it cannot be surmised that its reason

was that which Petitioner wishes it to

be. A conclusion, especially of the mag

nitude made by Petitioner in this regard,

cannot reliably be drawn from a small

and carefully selected set of illustra

tions, especially ones that do not even

accurately portray what they portend to.

For example, the fervor of crusade

alluded to is indicative of most,

if not all, attempts to reverse time-

honored and traditional concepts and

practices. It does not "show" that

the reason for abolition is basically a

concern with fundamental human decency.

It goes without saying that forces

55/ Bedau, The Death Penalty in Ameri

ca (Rev. ed 1967), p. 120. See

also, Bernard Lande Cohen, Law With

out Order (1970).

52

destructive of society are also often

imbued with the fervor of a crusade.

(3) Petitioner condemns what he

regards as the mainstay of support

for the death penalty. This "indicator

of unacceptability" is the belief in

retribution, atonement, or vengeance.

The implication is that such is not a

legitimate purpose.

In the first place, punishment for

its own sake is not regarded in law as

unconstitutional. The Court in Trop

referred to this in finding that the

purpose of denationalization was simply

to punish the deserter: "There is no

other legitimate purpose that the sta

tute could serve," the court concluded.

"Here the purpose [of the law] is

punishment, and therefore the statute

is a penal law." Trop v. Dulles, supra,

356 U.S. at 97. Mr. Justice Brennan,

in his concurring opinion in Trop,

indicated that if the sole purpose of

punishment was retribution, the punish

ment was not a valid one. Not inci

dentally, in discussing the purposes

of the penal law, he noted that the

thought of death as a penalty would

serve the legitimate purpose of deter

rence. Trop v. Dulles, supra, 356 U.S.

at 112 .

53

It is patent that the death penalty

serves a number of legitimate ends of

punishment, contrary to Petitioner's

contention. Such recognized purposes

are deterrence of the wrongful act by

threat of punishment (Trop, supra,

concurring opinion of Mr. Justice

Brennan, 256 U.S. at 111-112; Robinson,

supra, dissent of Mr. Justice Clark,

370 U.S. at 68; Powell v. Texas, 392

U.S. 514, 530 [1968]); the protection

of society itself and of its members

(Solesbee v. Balkcom, supra, 339 U.S.

at 13; Robinson, supra, concurring

opinion of Mr. Justice Douglas, 370 U.S. at

677; Trop, supra, Mr. Justice Brennan concurring

opinion, 256 U.S. at 111-112; included

as a purpose of the penal law is the

insulation of society from a dangerous

individual by imprisonment "or execu

tion") ; the repression of crime and

prevention of repetition (Weems v .

United States, supra, 217 U.S. at 381).

How can it possibly be said that

the death penalty does not act to

deter would-be crime perpetrators

from carrying out their schemes? In

Powell, supra, 392 U.S. at 531, the

Court presumed that the very existence

of criminal sanctions serves to reinforce

condemnation of murder, rape and other

anti-social conduct. it cannot, on

54

the other hand, be presumed that the

threat of death has not stayed the

hand and saved the life,simply because

the penalty has failed to deter those

who commit capital felonies. Statis

tics could never be gathered to prove

how many capital crimes were averted

by the existence of the death penalty,

for no census gatherer or poll-taker

could persuade even one person to admit

that he would have committed a murder,

or rape, or an armed robbery, or a

kidnapping, but for the knowledge

that he could have received the death

penalty! It is in the very nature of

man to recoil the most strenuously from

forfeiture of his life. Although this

deterrent effect cannot for lack of

knowledge be measured in terms of the

numbers of capital crimes NOT committed,

other indications of the prevailing

belief in the superior deterrent effect

of the death penalty are recitable:

a) Six of the states which have

partially abolished the death penalty

have retained it for certain crimes.

New York, Vermont, North Dakota, and

Rhode Island are particularly notable

for retaining it for murders committed

by certain prisoners, and New York and

Vermont retain it also for murder of ap i /police officer or certain persons in ■—

21/ NPS, p. 30.

55