Wise v. Lipscomb Brief as Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

March 28, 1978

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Wise v. Lipscomb Brief as Amicus Curiae, 1978. aa3b4360-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/12b46062-8c86-4d96-bf9a-e8906df9035f/wise-v-lipscomb-brief-as-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

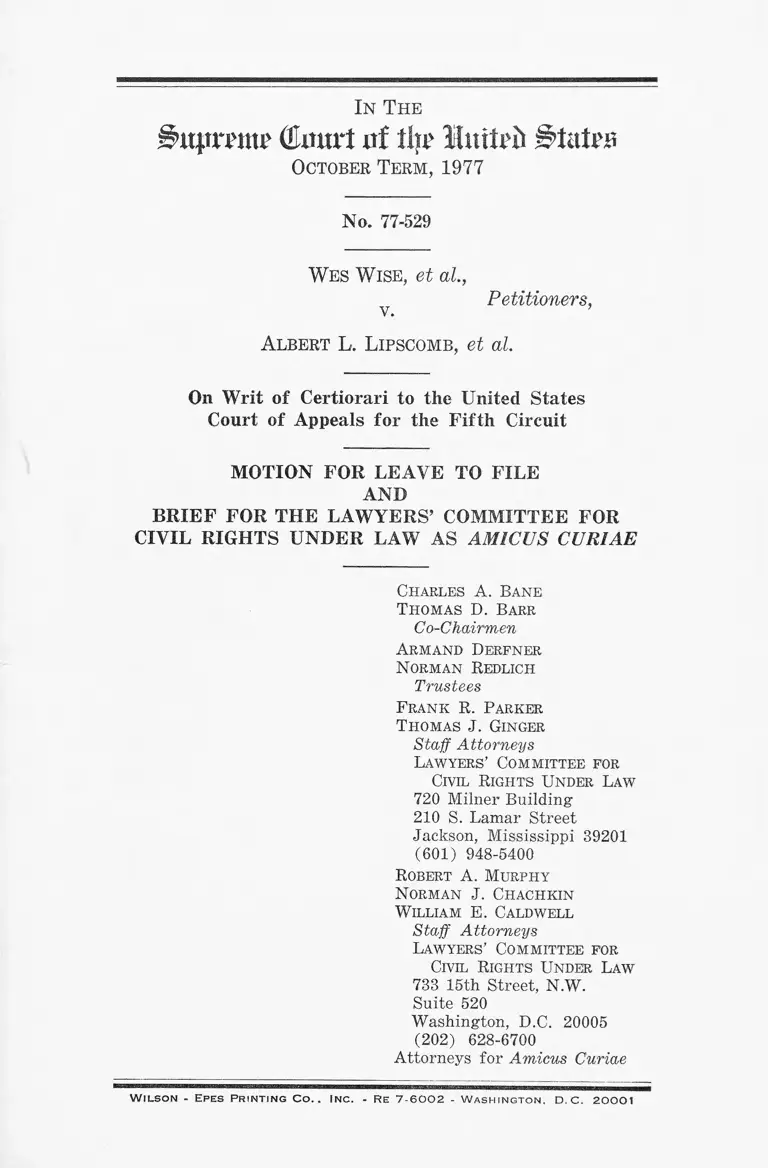

J&tprott? ( to r t af % MxuUh States

October Term , 1977

In The

No. 77-529

W es W ise, et al.,

Petitioners,v.

A lbert L. L ipscomb, et al.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE

AND

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR

CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW AS AMICUS CURIAE

Charles A. Bane

T homas D. Barr

Co-Chairmen

A rmand Dbrfner

N orman Redlich

Trustees

F rank R. Parker

T homas J. Ginger

Staff Attorneys

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

720 Milner Building

210 S. Lamar Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39201

(601) 948-5400

Robert A. Murphy

N orman J. Chachkin

W illiam E. Caldwell

Staff Attorneys

Lawyers ' Committee for

Civil Rights Undfr Law

733 15th Street, N.W.

Suite 520

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 628-6700

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

W il so n - Epes Print in g C o . . In c . - Re 7 - 6 0 0 2 - W a s h i n g t o n . D .C . 2 0 0 0 1

i>u|TX*i>uu> (Einirl itf lift' Inttrii BtnUx

October Term, 1977

In The

No. 77-529

Wes W ise, et al.,

v. Petitioners,

Albert L. Lipscomb, et al.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law,

proposed amicus curiae herein, respectfully seeks leave

of this Court to file the attached brief in order to assist

the Court in resolving the remedial questions presented

in this voting rights case.

As set forth in the attached brief, the Lawyers’ Com

mittee has been intimately involved for a number of years

in voting rights litigation on behalf of minority-race

voters, and we have participated, both as amicus curiae

and as the representative of parties, in many of this

Court’s important voting rights cases. The instant case

is of particular concern to us, as it will have a bearing

on the appropriate remedies to be applied in many of our

cases which, like this case, involve the effect of at-large

voting schemes on the participation o f minority voters in

the electoral process. We believe that we bring to this

case a fam iliarity with, and understanding of, the appli

cable decisions of this Court. We also bring to this case

considerable experience with the practical implementation

of those decisions, which may not be presented by the

parties. In addition, the attached brief presents an alter

native argument in support of the judgment below, based

upon established principles o f equitable remedies, which

we do not believe will be presented by any party.

Both sets of respondents have consented to the filing

o f this brief, but petitioners have refused consent.

W H EREFORE, the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil

Rights Under Law respectfully moves that its brief amicus

curiae be filed in this case.

March 28, 1978

Respectfully submitted,

Charles A. Bane

Thomas D. Barr

Co-Chairmen

A rmand Derfner

Norman Rkdlich

Trustees

Frank R. Parker

T homas J. Ginger

Staff Attorneys

Lawyers ’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

720 Milner Building-

210 S. Lamar Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39201

(601) 948-5400

Robert A. Murphy

Norman J. Chachkin

W illiam E. Caldwell

Staff Attorneys

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

733 15th Street, N.W.

Suite 520

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 628-6700

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Table of Authorities------ -----............-...........—................ - 11

Interest of Am icus Curiae...... ........-.......— .........-......— 1

Statement of the Case----------------- ----------- ----- ----------- 4

Summary of Argument--------- ---------------------------------- 9

Argument .... ........— ........................................... ................ 12

I. On The Facts Of This Case, At-Large Municipal

Elections For Members Of The Dallas City

Council Are Unconstitutional For Dilution Of

Black Voting Strength---- ---------- -------------------- 12

II. The Fifth Circuit Correctly Held That The

Remedy Ordered By The District Court Failed

To Meet The Requirements Applicable To Court-

Order Redistricting Plans -- ------- ------------------- 16

A. The eight/three plan ordered into effect by

the District Court was a court-ordered plan.. 16

B. There is no distinction between “ court-

ordered” plans and “ court-approved” plans

applicable here that would permit the city’s

eight/three plan to avoid the principles gov

erning court-ordered plans------------------------ 20

C. Neither the impact of the Mexican-American

vote nor the city’s interest in citywide rep

resentation justify a departure, in this court-

ordered redistricting plan, from the prefer

ence for single-member districts----------------- 23

1. The Mexican-American vo te ----------------- 26

2. The citywide viewpoint-------- ----- --------- 28

III. Alternatively, The Mixed Eight/Three Plan Or

dered Into Effect By The District Court— By

Retaining Three At-Large Seats— Is Constitu

tionally Inadequate As A Remedy For Unconsti

tutional At-Large Elections --------- ---- ------------- 32

Conclusion ......... ............................................... ................... 34

II

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Albermarle Paper Co. V. Moody, 422 U.S. 405

(1975) ________________ 32

Allen V. State Board of Elections, 393 U.S. 544

(1969) -------------- 12,17,22

Blacks United for Lasting Leadership, Inc. V. City

of Shreveport, La., 71 F.R.D. 623 (W.D. La,

1976) , appeal pending, No. 76-3619 (5th Cir.)__ 16

Bolden V. City of Mobile, 423 F. Supp. 384 (S.D.

Ala. 1976), appeal pending, No. 76-4210 (5th

Cir.) ------------------------------------------------------------- 16

Briscoe V. Bell, 432 U.S. 404 (1977) ______________ 17

Burns V. Richardson, 384 U.S. 73 (1966)________ 12, 30

Chapman V. Meier, 421 U.S. 1 (1975)_________ 23, 24, 30

Connor V. Finch, 431 U.S. 407 (1976) ....22, 24, 25, 28, 29

Connor v. Johnson, 402 U.S. 690 (1971), on re

mand, 330 F. Supp. 521 (S.D. Miss. 1971), fur

ther relief denied, 402 U.S. 928 (1971) ......9, 22, 24, 25

Connor v. Waller, 421 U.S. 656 (1975)____ ______ 17, 20

Connor v. Waller, 396 F. Supp. 1308 (S.D. Miss.

1975), rev’d, 421 U.S. 656 (1975)_____________ 21

Connor v. Williams, 404 U.S. 549 (1972)________ 18

Dallas County v. Reese, 421 U.S. 477 (1975)_____ 12

East Carroll Parish School Board V. Marshall, 424

U.S. 636 (1976)---------- ----- .......18,19, 20, 21, 23, 24, 27

Fairley V. Patterson, 393 U.S. 544 (1969) _______ 12

Fortson V. Dorsey, 379 U.S. 433 (1965) _____ ____ 12

Graves V. Barnes, 343 F. Supp. 704 (W. D. Tex.

1972), aff’d in part, rev’d in part sub nom.

White V. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973)_______ 13

Kirksey V. Board of Supervisors of Hinds County,

554 F.2d 139 (5th Cir. 1977) (en banc), cert,

denied, ------ U.S. —— (No. 77-499, Nov. 28,

1977) ---------------- ------------------------------------------- 20n, 33

Lipscomb v. Jonsson, 459 F.2d 335 (5th Cir.

1972) _______ ______________________ __ ______ 4

Louisiana V. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965) _. 33

Mahan V. Howell, 410 U.S. 315 (1973)__________ 25,27

n t

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

Paige V. Gray, 399 F. Supp. 459 (M.D. Ga. 1975),

vac’d and remanded, 538 F.2d 1108 (5th Cir.

1976) , on remand, 437 F. Supp. 137 (M.D. Ga.

1977) _______________ _________________________ 16

Parnell V. Rapides Parish School Bd., 563 F.2d

180 (5th Cir. 1977)______________ ________ _ 15, 28

Perkins v. Matthews, 400 U.S. 379 (1971) ......... 17

Perry v. City of Opelousas, 515 F.2d 639 (5th Cir.

1975) _________________________________ ______ 15

Reynolds V. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964) ___________ 10, 30

Stewart V. Waller, 404 F. Snpp. 206 (N.D. Miss.

1975) _________ 13n

Turner v. McKeithen, 490 F.2d 191 (5th Cir.

1973) ________________________________________ 16

United States V. Board of Comm’rs of Sheffield,

Ala., No. 76-1662 (decided March 6, 1978) _____ 17

Wallace V. House, 425 U.S. 947 (1976)........18,19, 21, 24

Wallace V. House, 515 F.2d 619 (5th Cir. 1975),

vac’d and remanded, 425 U.S. 947 (1976), on

remand, 538 F.2d 1138 (5th Cir. 1976), cert.

denied, 431 U.S. 965 (1977) _______ 15,19, 28-29, 29-32

Whitcomb V. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124 (1971)_______ 12

White V. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973)_______ 9,12, 13,

14,15, 27

Wise V. Lipscomb, No. A-149 (August 30, 1977) .. 9,20

Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir.

1973) (en banc), aff’d on other grounds sub nom.

East Carroll Parish School Board V. Marshall,

424 U.S. 636 (1976)____ ____________ 15-16, 18,19, 27

Statutes:

§ 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C.

§ 1973c (Supp. V 1975)___________________ __ 2, 7,17

Other Authorities:

Banzhaf, Multi-Member Electoral Districts—Do

They Violate the “ One Man, One Vote” Princi

ple?, 75 Y ale L.J. 1309 (1966)_______________ 13n

IV

Page

Bonapfel, Minority Challenges to At-Large Elec

tions: The Dilution Problem, 10 Ga. L. Rev. 353

(1976) __ ._____________ __ ____ ______ _________ 16

Comment, Section 5: Growth or Demise of Statu

tory Voting Rights?, 48 Miss. L.J. 818 (1977)....

Carpeneti, Legislative Apportionment: Multi-

Member Districts and Fair Representation, 120

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

U.Pa.L. Rev. 666 (1972)____________________ _ 13n

Sloane, “ Good Government” wnd the Politics of

Race, 17 Social Problems 156 (1969)_________ 13n

United States Commission on Civil Rights,

Political Participation (1968)______________ 13n

W ashington Research Project, The Shameful

Blight: The Survival of Racial Discrimina

tion in Voting in the South (1972) ________ 13n

In The

B u p m m (£ m tr t v t t t y H tt ftr ii

October Term, 1977

No. 77-529

Wes W ise, et a l .

v.

Petitioners,

Albert L. Lipscomb, et al.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR

CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW AS AMICUS CURIAE

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

was organized in 1963 at the request of the President of

the United States to involve private attorneys throughout

the country in the national effort to assure civil rights to

all Americans. The Committee’s membership today in

cludes two former Attorneys General, ten past Presidents

of the American Bar Association, two former Solicitors

General, a number of law school deans, and many of the

2

Nation’s leading lawyers. Through its national office in

Washington, D.C., and offices in Jackson, Mississippi, and

eight other cities, the Lawyers’ Committee over the past

fifteen years has enlisted the services of over a thousand

members of the private bar in addressing the legal prob

lems of minorities and the poor in voting, employment,

education, housing, municipal services, the administration

of justice, and law enforcement.

In the past, the Lawyers’ Committee has filed briefs

amicus curiae by consent of the parties or by leave of

this Court in a number of important civil rights cases.

The interest of the Lawyers’ Committee in this case

arises from its dedication to and interest in the full and

effective enforcement and administration of the Nation’s

constitutional and statutory provisions securing the voting

rights of minorities. As a result of providing legal repre

sentation to litigants in voting rights cases for the past

thirteen years, the Committee has gained considerable

experience and expertise in problems of racial discrimi

nation relating to the voting rights of minority citizens,

and in the requirements and guarantees of the Fourteenth

and Fifteenth Amendments and the Voting Rights Act

of 1965. Attorneys associated with the Lawyers’ Com

mittee represented the minority plaintiffs in two of the

first four cases to reach this Court on the scope of the

requirements of § 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965,

Fairley v. Patterson and Bunion v. Patterson, decided

sub nom. Allen v. State Board of Elections, 393 U.S. 544

(1969), and have provided continuing representation since

1970 to the plaintiff voters in the Mississippi state legis

lative reapportionment case, in which this Court has ren

dered five decisions in this decade, the latest of which

was Connor v. Finch, 431 U.S. 407 (1977). The Commit

tee also represented the minority voters in City of Rich

mond v. United States, 422 U.S. 358 (1975); and, we

filed amicus briefs in East Carroll Parish School Bd. v.

3

Marshall, 424 U.S. 636 (1976), and Georgia v. United

States, 411 U.S. 526 (1973).

In this case the Committee is interested in (1) the

continued viability of the principles announced by this

Court in White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973), that

at-large elections unconstitutionally dilute minority voting-

strength when maintained after an extensive past history

of racial discrimination affecting the voting process and

when at-large voting denies to minorities equal access to

the election process; (2) the proper scope and interpreta

tion of the principle first announced in a Lawyers’ Com

mittee case, Connor v. Johnson, 402 U.S. 690 (1971),

that in District Court-ordered reapportionment plans

single-member districts are preferred absent unusual cir

cumstances; and (3) the proper remedies in a case in

which at-large voting has been held unconstitutional for

dilution of minority voting strength. In addition, attor

neys associated with the Jackson, Mississippi office of the

Lawyers’ Committee currently have pending eight cases

challenging at-large municipal elections and voting dis

tricts for city council members, and the decision of the

Court in this case on the scope of a proper remedy is

likely to have a direct impact on the decisions in those

cases.

Because of our extensive and intimate involvement in

voting rights cases involving state legislatures, counties,

and municipalities, and our extensive knowledge of the

case law in the area, we believe that we can present a

perspective on this case which has not been presented by

the petitioners, and which may not be presented by the

respondents. First, we wish to direct the attention of the

Court to, and state our understanding of, the specific

cases in which the Court has defined what constitutes a

“ court-ordered” redistricting plan. Second, wTe desire to

show that this Court has indicated that any exceptions to

the general principle favoring single-member districts in

4

court-ordered plans must be narrowly construed, and are

applicable only in instances in which single-member dis

tricts threaten the enjoyment of secured constitutional

rights or in which there are insurmountable difficulties

to the creation of single-member districts. Third, and

we do not believe that this contention will be advanced

by the petitioners or respondents, we submit that the

proper remedy in this case must be determined by the

scope of the violation, and that the nature of the viola

tion dictates single-member districts as the only remedy

which provides full and complete relief for the constitu

tional violation.

The Lawyers’ Committee therefore files this brief as

friend of the Court urging affirmance of the judgment

below.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

_ Plaintiffs, black voters of Dallas, Texas, filed this ac

tion in 1971 challenging the at-large, citywide election of

members of the Dallas City Council for unconstitutional

dilution of black voting strength. The District Court on

its own motion at a hearing on a motion for preliminary

injunction to enjoin the 1971 city council elections dis

missed the complaint, and the Court of Appeals reversed

and remanded for a trial, Lipscomb v. Jonsson, 459 F.2d

335 (5th Cir. 1972). On remand, the District Court

certified the plaintiff class to consist of “ all blacks resid

ing within the corporate limits of the City of Dallas”

(399 F. Supp. 782, 783-84), but denied a motion to in

tervene filed on behalf of Mexican-American voters while

reserving to the Mexiean-Americans the right to partici

pate in the post-trial hearing on the question of relief

(id. at 784).

_ According to the 1970 Census, Dallas has a popula

tion of 844,401 persons, of whom 65 percent are white

(Anglo), 25 percent are black, and 10 percent are Mexi

5

can-American. Black citizens are highly segregated resi-

dentially, and are primarily concentrated in approximately

40 black-majority Census tracts in the Dallas inner city

area (399 F. Supp. at 785). Mexican-Americans consti

tute a majority in four Census tracts, and are otherwise

dispersed throughout Dallas (399 F. Supp. at 792-93).

Under the plan challenged by the plaintiffs, eleven city

council members were elected at-large to a term of two

years. Eight council members were required to run from

eight residential districts under a “place” requirement,

although elected in citywide voting, and the remaining

three— including the Mayor— were required to qualify by

“ place” but with no district residency requirement (399

F. Supp. at 785). A majority vote was required for elec

tion (id.). At least since 1959, city council elections have

been controlled largely by the white-dominated Citizens

Charter Association (CCA), a nonpartisan slating group

whose endorsed candidates have won 82 percent of the

elections (id. at 786).

Since 1907, only two blacks have been elected to the

Dallas City Council under the at-large system (id. at

7871.1 This, the District Court found, was a result of

“ the existence of past discrimination” (id. at 790) and

“ a customary lesser degree of access to the process of

slating candidates than enjoyed by the white community”

(id.). Both of the blacks elected to the city council were

elected as a result of endorsement by the CCA and ran

only against other black candidates (id. at 787). In addi

tion, the District Court found that black residents had

a “ lesser degree of opportunity . . . to meaningfully par

ticipate in the election process” under the at-large system

because of racially polarized voting under which “ the

white community, the non-minority voter tends not to

1 At the time of trial, the Dallas City Council was composed of

two blacks, one Mexican-American, and eight whites (Anglos)

(399 F. Supp. at 787, n.5).

6

vote for the black candidates” (id. at 790). The District

Court’s analysis of five races since 1959 in which blacks

ran for city council seats showed that black voters gen

erally voted overwhelmingly for black candidates, and

that white voters generally voted overwhelmingly for

white candidates, in white-on-black contests (id. at 785-

86). This current pattern of racial bloc voting, and also

the high degree of residential housing segregation, the

District Court found were present “ lingering effects” of

“past official race discrimination” (id. at 790). The evi

dence also showed that Dallas blacks living in the major

ity black Census tracts in the inner city area— 93 percent

of all blacks in Dallas— suffered deprivations and in

equalities in the areas of housing, education, employment,

and income (id. at 785).

The District Court found that in the past, the Dallas

City Council had enacted ordinances requiring segrega

tion of the races and the city council had acknowledged

racial discrimination in law enforcement (id. at 787),

but the Court held that the evidence showed that the city

council was presently responsive to the interests of the

minority communities (id. at 790-91). “ This present re

sponsiveness, however,” the District Court held, “ is not

enough to justify the present exclusive at-large voting

plan when weighed against the other factors which I

have found” (id. at 791).

Finding that blacks in Dallas had been subjected to

official past discrimination “which precludes effective

participation in the electoral system” and that “ black

voters of Dallas do have less opportunity than do the

white voters to elect councilmen of their choice” (id. at

790), the District Court held the all at-large system un

constitutional for dilution of black voting strength, and

this holding was not challenged on appeal, Lipscomb v.

Wise, 551 F.2d 1043, 1045 (5th Cir. 1977), nor is it

challenged in this Court.

7

After striking down the all at-large scheme, the Dis

trict Court afforded the parties an opportunity to present

redistricting plans. The city proposed as a remedy that

eight city council members be elected from, districts—

corresponding to the eight districts previously estab

lished for the residency requirement under the at-large

system— and that three city council members, including

the Mayor, continue to be elected at large (the “ eight/

three plan” ) (399 F.Supp. at 791). The city’s proposal

to the District Court was not submitted for Federal pre

clearance under § 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965,

42 U.S.C. § 1973c. The plaintiffs offered two plans, one

providing ten single-member districts and a Mayor elect

ed at-large (the “ ten/one plan” ), and a second alterna

tive plan providing for the election of all eleven mem

bers of the City Council from single-member districts,

with the Mayor elected by the City Council itself (the

“ eleven./zero plan” ) (id.).

After a hearing on the remedy, the District Court

ordered into effect for the April, 1975 city council elec

tions (id. at 798) the eight,/three plan proposed by the

city council. Under the city’s plan blacks comprised a

majority of the population in only two districts (District

6, 73.60% black; District 8, 87.30% black) and Mexican-

Americans lacked a majority in any district and at best

constituted only 20 percent of the population in one (id.

at 795). The District Court’s preference for the city’s

plan was based on (1) “ a consideration of the impact

that any plan would have on the Mexican-American citi

zens of Dallas” and (2) “ the legitimate governmental

interest to be served by having a city-wide viewpoint on

the City Council” (id. at 792). As to the first, the

District Court reasoned that Mexican-Americans “benefit

to a significant extent from at-large voting” as a result

of their “ swing vote” position (id. at 793), and thus

the eight/three plan would “ enhance the opportunity of

the Mexican-American citizens of Dallas to utilize their

voting potential in a significant new way, while not un

dermining the degree of participation they have enjoyed

under the exclusive at large voting plan” {id. at 794).

As to the second, the District Court found on testimony

of defendants’ witnesses that the election of some coun

cil members at-large would be “ desireable” [sic] {id. at

794), that “ there is a legitimate governmental interest

to be served by having some at-large representation on

the Dallas City Council; [and] that this governmental

interest is the need for a city-wide view on those matters

which concern the city as a whole, e.g., zoning, budgets,

and city planning . . {id. at 795).

After the 1975 city council elections in which a Mexi-

can-American candidate was defeated for one of the at-

large positions, counsel for the Mexican-Americans sought

further modification of the court-ordered plan and pro

posed to show that far from enhancing their position, the

eight/three plan “ dilutes the vote of the Mexican-

American citizen and makes it impossible for a Mexican-

American to participate in the election process” (551

F.2d at 1048).

On appeal, the Fifth Circuit held that the remedy

ordered into effect by the District Court was inadequate

and the Court reversed the judgment of the District

Court and remanded for a new single-member districting

plan with the city having the option of electing the

Mayor at-large (the ten/one plan) or by election of the

city council (the eleven/zero plan). 551 F.2d 1043, 1049.

The appeals court considered that the relief adopted and

ordered into effect by the District Court must be judged

by the standards governing court-ordered plans (551

F.2d at 1046-47), and that the particular situation of the

Mexican-American citizens in Dallas did not constitute a

“ special circumstance” justifying a departure from the

preference for single-member districts in court-ordered

plans {id. at 1048) :

9

We conclude that (1) as far as this record is con

cerned, chicano “ access” to the political processes of

Dallas need not be improved since it is ex hypothesi

the same “ access” as that of white persons; and (2)

the district court’s opinion was based on a theory of

electoral politics that applies as well if not better to

single-member districts than to at-large elections.

Thus, the situation of the Mexican-American voters

does not constitute a special circumstance within

the contemplation of the cases which require that

absent such special circumstances, the city’s legis

lative body be elected from single member districts.

On August 30, 1977, Mr. Justice Powell granted a

stay of the judgment of the Court- of Appeals pending

disposition of the defendants’ petition for certiorari,

Wise v. Lipscomb, No. A-149, and on November 2, 1977

the Court denied an application for an injunction against

filling one of the three at-large seats by special election,

No. A-396. Defendants’ petition for a writ of certiorari

was granted on January 9, 1978.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

This case is important because the arguments of peti

tioners, if accepted, would erode and undo the major

holdings of this Court in White V. Regester, 412 U.S. 755

(1973), and Connor v. Johnson, 402 U.S. 690 (1971),

and their progeny which were designed to end the century-

long voting discrimination against minority citizens and

to make the newly-gained franchise secured by the Voting

Rights Act of 1965 a reality. Beginning with the earliest

reapportionment cases, this Court recognized that at-large

voting for public officials has a dangerous potential for

minimizing and cancelling out the vote of minority citi

zens. In White-— articulating criteria which petitioners

concede are directly applicable here— the Court held that

the Fourteenth Amendment prohibits at-large voting

where it denies blacks and Mexican-Americans equal ac

10

cess to the political process, and in Connor and its pro

geny the Court held that because at-large voting sub

merges electoral minorities, single-member districts are

preferred in court-ordered plans, absent unusual circum

stances. The principles developed in these cases are di

rectly applicable here both to protect against dilution

of minority voting strength and to secure the goal of

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 565-66 (1964), of “ fair

and effective representation for all citizens.”

This case presents the unusual and seemingly para

doxical question of whether some at-large voting is

proper as a remedy for an all at-large voting scheme

conceded to be unconstitutional for dilution of black

voting strength. If the Court accepts petitioners’ hy

pothesis, it will sanction a remedy which incorporates

part of the constitutional violation!

Because the city’s eight/three plan was submitted to

the District Court pursuant to court order as a remedy,

because the District Court ordered the eight/three plan

into effect for city council elections, and because when the

plan was submitted the city lacked the authority under

its own Charter legislatively to enact such a plan, the

Court of Appeals was correct in rejecting the city’s plan

as a remedy because it clearly fails to comply with the

rule that in court-ordered plans single-member districts

are preferred absent unusual circumstances. Under the

circumstances present here, this Court has never recog

nized any distinction between the standards controlling

“ court-ordered” plans and those governing “ court-ap

proved” plans. Such a distinction would allow petition

ers to circumvent both the principles governing court-

ordered plans and the Federal preclearance requirements

of § 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, both of which

were designed to prevent new forms of racial discrimina

tion in voting. Indeed, such a radical departure from

11

the prior decisions of this Court would severely under

mine and as a practical matter completely destroy the

guarantees against racial discrimination in voting so

laboriously developed in the most important voting rights

decisions of this Court.

Nor are the findings of the District Court sufficient

in this case to sustain an exception to the rule of prefer

ence for single-member districts in court-ordered plans.

The District Court’s findings regarding the Mexiean-

American vote are contradictory and at best ambiguous,

and this Court in prior decisions has rejected the con

tention that the city’s expressed interest for citywide

representation is an “unusual circumstance” sufficient to

overcome the preference for single-member districts.

Alternatively, even if the Court rejects our contention

that this is a court-ordered plan governed by the single

member district rule, the city’s plan must fall under the

equitable principles of securing “ complete justice” and

adjusting remedies to grant “ necessary relief.” The city’s

plan must fail as a remedy because it includes elements

of the constitutional violation. If the election of eleven

city council members at-large unconstitutionally dilutes

black voting strength, then the election of three city

council members at-large also minimizes and cancels out

black voting strength. Further, to the extent that any

fairly drawn single-member district plan would include

three majority black districts (as opposed to two in the

city’s plan), and would include districts in which the

percentage of Mexican-Americans would be higher than

their citywide percentage, the eight/three plan fails to

place either minority group in the position they would

have held but for the constitutional violation, and in fact

perpetuates, rather than eradicates, the discrimination of

the past.

12

ARGUMENT

I. ON THE FACTS OF THIS CASE, AT-LARGE

MUNICIPAL ELECTIONS FOR MEMBERS OF THE

DALLAS CITY COUNCIL ARE UNCONSTITU

TIONAL FOR DILUTION OF BLACK VOTING

STRENGTH.2

While at-large elections are “not per se illegal under

the Equal Protection Clause,” Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403

U.S. 124, 142 (1971), the Court has repeatedly held that

at-large voting is unconstitutional when “ designedly or

otherwise, a multi-member constituency apportionment

scheme, under the circumstances of a particular case,

would operate to minimize or cancel out the voting

strength of racial or political elements of the voting popu

lation.” Burns v. Richardson, 384 U.S. 73, 88 (1966) ;

Fortson v. Dorsey, 379 U.S. 433, 439 (1965); accord,

Dallas County v. Reese, 421 U.S. 477, 480 (1975) ; White

v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755, 765 (1973); Whitcomb v.

Chavis, supra, 403 U.S. at 143. In Fairley v. Patterson,

decided sub nom. Allen v. State Board of Elections, 393

U.S. 544, 569 (1969), the Court in considering whether

a switch to at-large elections was subject to Federal

preclearance under § 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965

held:

The right to vote can be affected by a dilution of

voting power as well as by an absolute prohibition on

casting a ballot. See Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533,

555. Voters who are members of a racial minority

might well be in the majority in one district, but

in a decided minority in the county as a whole. This

type of change could therefore nullify their ability

to elect the candidate of their choice just as would

prohibiting some of them from voting.

2 Although the city has acquiesced in the District Court’s finding

of unconstitutional dilution, we deem it important to address this

issue to emphasize the nature of the violation as it affects the scope

of the necessary remedy.

13

In many parts of the South— and possibly elsewhere—

at-large elections “ designedly or otherwise” are the last

vestige of racial segregation in voting.3 Although blacks

and other minorities in the South are now permitted

to register and vote in large numbers— primarily as a

result of the Voting Rights Act of 1965— at-large elec

tions which dilute minority voting strength “nullify their

ability to elect the candidate of their choice just as

would prohibiting some of them from voting.”

In White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755, 766 (1973), aff’g

in relevant part, Graves v. Barnes, 343 F. Supp. 704

(W.D. Tex. 1972) (three-judge court), the Court held

that at-large elections unconstitutionally dilute minority

voting strength when plaintiffs have produced

evidence to support findings that the political proc

esses leading to nomination and election were not

equally open to participation by the group in ques

tion— that its members had less opportunity than

3 W ashington Research Project, The Shameful Blight : T he

Survival of Racial Discrimination in V oting in the South 109-26

(1972); United States Commission on Civil Rights, Political

Participation 21-25 (1968); see also Carpeneti, Legislative Appor

tionment: Multi-Member Districts and Fair Representation, 120

U. Pa .L. Rev. 666 (1972) ; Banzhaf, Multi-Member Electoral Dis

tricts— Do they Violate the “ One Man, One Vote” Principle, 75

Y ale L.J. 1309 (1966). There can be no doubt that in some in

stances at-large municipal elections have been instituted for pur

poses of discrimination, e.g., Stewart V. Waller, 404 F. Supp. 206

(N.D. Miss. 1975) (three-judge court) (1962 Mississippi statute

requiring switch to at-large municipal voting held unconstitutional

as racially motivated). In other instances, the justification advanced

is to eliminate ward politics and to promote governmental reform,

but the effect on minority participation is equally discriminatory:

In a fundamental sense, the Black American has fallen

victim of governmental reform. In their zeal for efficiency,

democratic government, and the elimination of corruption, the

reformers have led us to new political systems which operate

to the detriment of minority groups.

Sloane, “ Good Government” and the Politics of Race, 17 Social

Problems 156, 174 (1969).

14

did other residents in the district to participate in

the political processes and to elect legislators of

their choice.

The Court in White held at-large voting for the Texas

Legislature in Dallas County unconstitutional on a show

ing of (1) “ the history of official racial discrimination in

Texas, which at times touched the right of Negroes to

register and vote and to participate in the democratic

processes” ; (2) Texas law “ requiring a majority vote

as a prerequisite to nomination in a primary election” ;

(3) the “ so-called ‘place’ rule limiting candidacy for

legislative office from a multimember district to a speci

fied ‘place’ on the ticket” ; (4) since Reconstruction, only

two black candidates from Dallas County has been elected

to the House of Representatives, and these were the only

two blacks ever slated by the white-controlled Dallas

Committee for Responsible Government (DCRG) ; and

(5) the DCRG did not require the support of black

voters, and “ did not therefore exhibit good-faith concern

for the political and other needs and aspirations of the

Negro community.” 412 U.S. at 766-67.

The Court made similar findings with respect to Mexi-

can-Ameriean voters in Texas. The Court found that

the Mexican-American community of Bexar County (San

Antonio) was effectively removed from the political

processes on proof that it “had long suffered from, and

continues to suffer from, the results and effects of invidi

ous discrimination and treatment in the fields of educa

tion, employment, economics, health, politics and others” ;

that the state poll tax and restrictive voter registration

procedures had foreclosed effective political participation;

and that “ the Bexar County legislative delegation in the

House -was insufficiently responsive to Mexican-American

interests.” Id. at 767-69. Single-member legislative dis

tricts were required “ to remedy ‘the effects of past and

present discrimination against Mexican-Amerieans’ . . .

15

and to bring the community into the full stream of politi

cal life of the county and State by encouraging their

further registration, voting, and other political activities.”

Id. at 769.4

White is the first case in which this Court struck down

at-large voting— there in multi-member legislative dis

tricts— for unconstitutional dilution of minority voting

strength, and the lower courts have applied the White

standards to invalidate at-large elections at the county,

parish, and municipal levels where the proof shows that

at-large voting denies minorities equal access to the po

litical process. E.g., Parnell v. Rapides Pamsh School

Bd., 563 F.2d 180 (5th Cir. 1977); Wallace v. House, 515

F.2d 619 (5th Cir. 1975), vacated and remanded on re

lief, 425 U.S. 947 (1976), on remand, 538 F.2d 1138 (5th

Cir. 1976), cert, denied, 431 U.S. 965 (1977); Perry v.

City of Opelousas, 515 F.2d 639 (5th Cir. 1975) ; Zimmer

v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir. 1973) (en banc),

aff’d on other grounds sub nom. East Carroll Parish

i The District Court’s judgment affirmed by this Court also

rested on evidence of racial bloc voting, 343 F. Supp. at 731, 732:

The population of the West Side of San Antonio tends to

vote overwhelmingly for Mexiean-American candidates when

running against Anglo-Americans in party primary or special

elections, to split when Mexican-Americans run against each

other, and to support the Democratic Party nominee regardless

of ethnic background in the general elections. The record

shows that the Anglo-Americans tend to vote overwhelmingly

against Mexican-American candidates except in a general elec

tion when they tend to vote for the Democratic Party nominee

whoever he may be although in a somewhat smaller proportion

than they vote for Anglo-American candidates, * * * It is not

suggested that minorities have a constitutional right to elect

candidates of their own race, but elections in which minority

candidates have run often provide the best evidence to deter

mine whether votes are cast on racial lines. All these factors

confirm the fact that race is still an important issue in Bexar

County and that because of it, Mexican-Americans are frozen

into permanent political minorities destined for constant de

feat at the hands of the controlling political majorities.

16

School Bd. v. Marshall, 424 U.S. 636 (1976) ; Turner v.

McKeithen, 490 F.2d 191 (5th Cir. 1973); Paige v. Gray,

399 F. Supp. 459 (M.D. Ga. 1975), vacated and re

manded, 538 F.2d 1108 (5th Cir. 1976), on remand, 437

F. Supp. 137 (M.D. Ga. 1977) ; Bolden v. City of Mobile,

423 F. Supp. 384 (S.D. Ala. 1976), a,ppeal pending, No.

76-4210 (5th Cir.) ; Blacks United for Lasting Leader

ship, Inc. v. City of Shreveport, Louisiana, 71 F.R.D. 623

(W.D. La. 1976), appeal pending, No. 76-3619 (5th

Cir.). See Bonapfel, Minority Challenges to At-Large

Elections: The Dilution Problem, 10 Ga . L. Rev. 353

(1976).

Here it is clear that the District Court properly ap

plied the White v. Regester standards to strike down at-

large municipal voting which minimized and cancelled

out black voting strength. On the findings of fact made

by the District Court, all of the elements which led this

Court to hold unconstitutional at-large voting for the Dal

las County delegation to the Texas Legislature equally

were present to deny Dallas blacks equal access to the

municipal voting process. Hence the District Court prop

erly concluded that at-large municipal elections violated

plaintiffs’ Fourteenth Amendment rights.

II. THE FIFTH CIRCUIT CORRECTLY HELD THAT

THE REMEDY ORDERED BY THE DISTRICT

COURT FAILED TO MEET THE REQUIREMENTS

APPLICABLE TO COURT-ORDERED REDISTRICT

ING PLANS.

A. The Eight/Three Plan Ordered Into Effect by the

District Court Was a Court-Ordered Plan.

The mixed eight/three plan was adopted by the District

Court as a remedy for at-large, citywide municipal elec

tions in this case and ordered into effect for the April,

1975 municipal elections (399 F. Supp. at 798). When

it submitted the plan to the District Court, the Dallas

17

City Council lacked the legislative authority to change

on its own the council voting system and to provide for

the election of eight council members by districts {id.

at 800) :

Changes to the voting system necessarily are changes

to the Charter and absent a judicial determination

of unconstitutionality, such changes can only be ef

fected by a Charter Amendment adopted by the

voters.5

Further, any effort by the Dallas City Council legisla

tively to “ enact or seek to administer” such a change

without Federal preclearance was barred by § 5 of the

Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C. § 1973c. United

States v. Board of Comm’rs of Sheffield, No. 76-1662

(decided March 6, 1978) ; Briscoe v. Bell, 432 U.S. 404

(1977); Connor v. Waller, 421 U.S. 656 (1975) ; Perkins

v. Matthews, 400 U.S. 379 (1971); Allen v. State Bd. of

Elections, supra.6 No such Federal preclearance of the

switch to the eightythree plan has been sought or ob

tained.

In the redistricting cases, this Court has developed

certain principles governing court-ordered redistricting

plans. The cases articulating these principles and apply

5 Subsequently, the City in April, 1976 did submit its eight/three

plan ordered into effect by the District Court to a Charter Amend

ment vote and the amendment was adopted. However, it still was

not submitted for Federal preclearance under § 5. This tactic does

not alter the fact that the plan was first adopted by the District

Court and ordered into effect for the April, 1975 city council elec

tions. The adoption of the court-ordered plan by the City by Charter

Amendment indicates only compliance with the District Court’s

order.

6 The State of Texas, and consequently all local jurisdictions,

United States v. Board of Election Comm’rs of Sheffield, supra,

were brought within the coverage o f § 5 of the Voting Rights Act

of 1965 by the 1975 amendments to the Act. See Briscoe v. Bell,

supra. As amended, § 5 covers all changes in Dallas election laws

enacted after November 1, 1972. 42 U.S.C. § 1973c (Supp. V 1975).

18

ing them make no distinction whether the plan adopted

or approved by the court and ordered into effect as a

remedy for a constitutional violation is a plan that has

been formulated by the District Court, Connor v. Wil

liams, 404 U.S. 549 (1972), or formulated by the local

legislative body itself, Wallace v. House, 425 U.S. 947

(1976) ; East Carroll Parish School Bd. v. Marshall, 424

U.S. 636 (1976).

The salient facts of East Carroll Parish are similar to

those presented here. In 1968, the District Court struck

down for malapportionment the wards established for

election of members of the East Carroll Parish police

jury and school board, and the police jury proposed as

a remedy that all members of the policy jury and school

board be elected at-large, which the District Court adopted

and ordered into effect (424 U.S. at 637). In 1971, the

District Court instructed the police jury and school board

to file new plans based on 1970 Census data, and the

police jury and school board once against submitted their

at-large plan. “ Following a hearing the District Court

again approved the multi-member arrangement” {id. at

637-38), holding that there was no dilution of black vot

ing strength because the parish was majority black in

population (Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297, 1301

(5th Cir. 1973) (en banc)). The Fifth Circuit vacated

and remanded, not because the plan failed to comply with

the principles governing court-ordered plans, but because

at-large voting unconstitutionally diluted black voting

strength under the White v. Regester criteria, Zimmer

v. McKeithen, swpra.

On certiorari, the black voter intervenors contended

that the District Court’s plan failed to meet the require

ments governing court-ordered plans, while the Solicitor

General filed an amicus brief arguing that because the

plan was “ submitted to [the District Court] on behalf of

a local legislative body” (424 U.S. at 638 n.6) it should

19

be treated as local legislation subject to the requirements

of § 5 of the Voting Rights Act. But this Court rejected

the Government’s contention and declined to depart from

the rule “ that court-ordered plans resulting from equi

table jurisdiction over adversary proceedings are not con

trolled by § 5” (id .).

The Court held that the at-large plan in East Carroll

Parish was a court-ordered plan subject to the general

principles governing such plans— and not local legislation

subject to § 5— because “ the reapportionment scheme was

submitted and adopted pursuant to court order” (id.) and

because the police jury lacked the authority under state

law (because of a § 5 objection to the 1968 state author

izing legislation) to reapportion itself by adopting at-

large elections “ on its own authority.” Accordingly, when

Courts of Appeals have held that the principles governing

court-ordered plans are not applicable to plans proposed

by local legislative bodies and adopted by District Courts

as a remedy for unconstitutional districts, Zimmer v. Mc-

Keithen, 485 F.2d 1297, 1302 (5th Cir. 1978), aff’d on

other grounds sub nom. East Carroll Parish School Bd. v.

Marshall, supra; Wallace v. House, 515 F.2d 619, 635-36

(5th Cir. 1974), vacated and remanded, 426 U.S. 947

(1976), this Court has granted certiorari either to cor

rect the ground for decision, East Carroll Parish School

Bd. v. Marshall, supra, or to vacate the judgment and

remand for further consideration, Wallace v. House,

supra.

All of the elements of the definition of a court-ordered

plan present in East Carroll Parish are present here. The

city council’s plan was submitted to the District Court

pursuant to court order (399 F. Supp. at 784) ; the plan

was “ ordered” into effect by the District Court (id. at

798) ; and, the city council lacked the authority to enact

and implement the eight/three plan on its own both by

the City Charter (id. at 800) and by the Federal pre

20

clearance provisions of § 5 of the Voting Rights Act of

1965.7

B. There Is No Distinction Between “ Court-Ordered”

Plans and “ Court-Approved” Plans A pplicable H ere

That Would Permit the City’s E igh t/T h ree Plan

To Avoid the Principles Governing Court-Ordered

Plans.

Contrary to the opinion of Mr. Justice Powell in grant

ing the stay of the Fifth Circuit’s judgment, Wise v. Lips

comb, No. A-149 (August 30, 1977), slip op., p. 3, n. 2,

this Court in considering whether the principles governing

court-ordered plans apply has never recognized a distinc

tion between a “ court-ordered plan” and a “ court-approved

plan.” Indeed, in East Carroll Parish, which Mr. Justice

Powell cites as an example of a court-ordered plan {id.),

the Court interchangeably referred to the multi-member

plan “ approved” (424 U.S. at 638) and “ adopted” {id. at

638 n.6) by the District Court, and described the action

of the District Court as “ approving” {id. at 638 n.4),

“ adopting” {id. at 639), and “ endorsing” {id.) the at-

large plan.

Both East Carroll Parish and Connor v. Waller, 421

U.S. 656 (1975), indicate that— at least in jurisdictions

covered by the Federal preclearance requirements of § 5

of the Voting Rights Act of 1965— there is no third

category of “ court-approved” plans which circumvent both

the principles governing court-ordered plans and the Fed

eral preclearance requirements of § 5 governing legisla

7 While discussed in East Carroll Parish, the legal authority of

the local governing body is not crucial to the definition. A local

governing body may have full authority to redistrict itself, but if

its plan is submitted to the District Court and implemented pur

suant to court order, then it still is a court-ordered plan. Cf. Kirksey

v. Board of Supervisors of Hinds County, 554 F.2d 139 (5th Cir.

1977) (en banc), cert, denied, ------ U.S. ------ (No. 77-499, No

vember 28, 1977).

21

tively-enacted plans. In Connor v. Waller, supra, the

District Court purported to approve an uncleared state

legislative reapportionment plan enacted by the Missis

sippi Legislature to supplant a reapportionment scheme

previously struck down by the District Court as uncon

stitutional, 396 F. Supp. 1308 (S.D. Miss. 1975) (three-

judge court). On appeal, this Court reversed, holding

that the District Court lacked jurisdiction to approve the

plan in the absence of § 5 preclearance (421 U.S. at 656) :

Those Acts are not now and will not be effective

as laws until and unless cleared pursuant to § 5.

The District Court accordingly also erred in deciding

the constitutional challenges to the Acts based upon

claims of racial discrimination.

The facts of Connor v. Waller show why the plan at

issue here is a court-ordered, and not a legislatively-

enacted, plan. Contrary to the city’s action here, in

Connor v. Waller the plan was not submitted to the Dis

trict Court pursuant to court order as a proposed remedy,

but rather was enacted by a legislature on its own with

full authority to promulgate such a plan (396 F. Supp.

at 1311). Further, contrary to the District Court’s order

here, the District Court did not purport to order the

legislature’s plan into effect, but merely sustained it

against constitutional challenge (396 F. Supp. at 1332).

The cases cited above— East Carroll Parish and Wal

lace V. House— firmly establish that the principles gov

erning court-ordered plans apply -whether the plan has

been proposed by a legislative body to the District Court

or formulated by the District Court itself, and this firmly

established rule of law is salutary and should be followed

in this case. First, in enacting and reenacting the Voting

Rights Act Congress was aware that states and political

subdivisions covered by the suspension-of-voting-tests pro

vision might enact changes in their election laws which

would nullify or dilute the newly secured franchise of

22

minorities, Allen v. State Board of Elections, supra, 393

U.S. at 548, and therefore strict scrutiny of election law

changes through Federal preclearance as provided by § 5

was required. The rule first enunciated in Connor v.

Johnson, 402 U.S. 690, 691 (1971), that “ [a] decree of

the United States District Court is not within reach of

Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act” is compatible and

not inconsistent with this concern because the Court has

developed strict standards governing excepted court-or

dered plans to insure against dilution of minority voting

strength through at-large elections, Connor v. Johnson,

supra, 402 U.S. at 692, or through gerrymandering of

district lines, Connor v. Finch, 431 U.S. 407, 421-26

(1976) . See Comment, Section 5 : Growth or Demise of

Statutory Voting Rights?, 48 Miss. L.J. 818, 834-36 n.125

(1977) .

Any new rule which would allow a redistricting plan

submitted to a District Court by a state or political sub

division covered by § 5 to escape both § 5 preclearance

and the standards governing court-ordered plans would

be entirely inconsistent with the intent of Congress in

enacting the Voting Rights Act and would invite abuse

and circumvention by suspect jurisdictions of the neces

sarily stringent standards applicable to § 5 review or al

ternatively to court-ordered plans.

Second, very few court-ordered redistricting plans or

dered into effect as a remedy for a constitutional violation

are formulated by the District Court itself, particularly

in cases involving counties and municipalities. In the

typical case, the District Court directs the parties to

submit proposed plans, and then selects among the pro

posed plans for the most efficacious remedy.8 We cannot

believe that this Court, in formulating the special rules

governing court-ordered plans and announcing them as

general principles governing all “ court-ordered plans,”

8 See cases cited on pp. 15-16, supra.

23

Chapman v. Meier, 420 U.S. 1, 18 (1975), intended to

restrict their applicability to the narrow class of cases in

which the District Judges themselves actually draw the

new district lines. Indeed, such a narrow limitation of

the general principles governing court-ordered plans would

undermine, weaken, and unduly restrict the broadly bene

ficial purposes such rules are designed to serve, Chapman

v. Meier, supra, 420 U.S. at 15-18.

The Court of Appeals here was correct in treating the

eight/three plan proposed by the city council and adopted

by the District Court as a court-ordered plan to which the

general principles governing court-ordered plans apply.

C. Neither the Impact of the Mexican-American Vote

Nor the City’s Interest in City wide Representation

Justify a Departure, in This Court-Ordered Redis

tricting Plan, From the Preference for Single-

Member Districts.

As the Court held in East Carroll Parish School Bd.

v. Marshall, supra, 424 U.S. at 639:

We have frequently reaffirmed the rule that when

United States district courts are put to the task of

fashioning reapportionment plans to supplant eon-

cededly invalid state legislation, single-member dis

tricts are to be preferred absent unusual circum

stances, Chapman v. Meier, 420 U.S. 1, 17-19

(1975) ; Mahan v. Howell, 410 U.S. 315, 333 (1973);

Connor v. Williams, 404 U.S. 549, 551 (1972) ; Con

nor v. Johnson [402 U.S. 690] at 692.

In court-ordered plans, multi-member districts and at-

large voting are to be avoided because of the “practical

weaknesses inherent in such schemes,” Chapman v. Meier,

supra, 420 U.S. at 15-16:

First, as the number of legislative seats within

the district increases, the difficulty for the voter

in making intelligent choices among candidates also

24

increases. * * * Ballots tend to become unwieldy,

confusing, and too lengthy to allow thoughtful con

sideration. Second, when candidates are elected at

large, residents of particular areas within the dis

trict may feel that they have no representative

specially responsible to them. * * * Third, it is

possible that bloc voting by delegates from a multi

member district may result in undue representation

of residents of these districts relative to voters in

singlemember districts. * * * Criticism of multimem

ber districts has been frequent and widespread.

Last Term in Connor v. Finch, 431 U.S. 407, 415 (1977),

the Court reiterated:

Because the practice of multimember districting can

contribute to voter confusion, make legislative rep

resentatives more remote from their constituents,

and tend to submerge electoral minorities and over

represent electoral majorities, this Court has con

cluded that single-member districts are to be pre

ferred in court-ordered legislative reapportionment

plans unless the court can articulate a ‘singular

combination of unique factors’ that justifies a dif

ferent result. Mahan v. Howell, 410 U.S. 315, 333;

Chapman v. Meier, supra, at 21; East Carroll Parish

School Board v. Marshall, 424 U.S. 636, 639.

Although this principle, sometimes called the Connor rule,

was first developed in a state legislative reapportionment

case, Connor v. Johnson, supra, 402 U.S. at 692, the Court

subsequently applied it to cases involving redistricting of

a parish, East Carroll Parish School Bd. v. Marshall,

supra, and a municipality, Wallace v. House, supra. The

rule is not confined to large multi-member districts, but

applies to small ones as well, Chapman v. Meier, supra

(applied to multi-member districts electing between two

and five legislators); East Carroll Parish School Bd. v.

Marshall, supra (parish of 12,884 population), and ap

plies regardless of how long a state policy favoring at-

25

large voting has been in effect, Connor v. Finch, 431 U.S.

407, 415 (1977) (historic policy in effect throughout

Mississippi history). The rule also is applicable regard

less of whether at-large voting is otherwise unconstitu

tional for dilution of minority voting strength, Chapman

v. Meier, supra, 420 U.S. at 19. Moreover, these cases

show that inclusion in a remedial plan of some or even

a significant number of single-member districts makes

the at-large or multi-member features no less unaccepta

ble in the “ court-ordered” context.

The Connor rule governing court-ordered plans yields

beneficial results and a more effective exercise of the

franchise, and therefore only a narrow range of excep

tions have been— and should be— allowed. In Comior v.

Johnson, supra, this Court directed the District Court to

devise a single-member districting plan “ absent insur

mountable difficulties,” 402 U.S. at 692. On remand, the

District Court found that it was too close to the regularly

scheduled elections and the Census data were insufficiently

complete to allow creation of single-member districts, 330

F. Supp. 521 (S.D. Miss. 1971) (three-judge court), and

this Court refused further relief, 403 U.S. 928 (1971).

Then in Mahan v. Howell, 410 U.S. 315 (1973), this

Court allowed the creation of only one multi-member dis

trict in a statewide legislative reapportionment plan as

an “ interim remedy” because of a “ singular combination

of unique factors” (410 U.S. at 333)— the fact that

single-member districts, beceause of problems with the

Census data, created underrepresentation of military per

sonnel in violation of their constitutional rights {id. at

331-332). In no other case has this Court countenanced

at-large voting in a court-ordered redistricting plan.

No such factors are present here, and the considerations

relied upon by the District Court and advanced by the

defendants to justify three at-large seats have previously

26

been rejected by this Court as insufficient to sustain a

departure from the single-member district rule.

(1) The Mexican-American Vote.

The District Court held that the mixed eight/three plan

would “ enhance” political participation opportunities for

Mexican-Americans without “undermining” the limited

degree of participation they had gained under the all at-

large system (399 F. Supp. at 794). However, the Dis-

tirct Court’s findings in this regard are contradictory on

their face and quite speculative. The District Court noted

testimony at the remedy hearing that under the at-large

system there had been past discrimination against Mexi

can-Americans and that Mexican-Americans are denied

equal access to the political process, and specifically found

“ that Mexican-American citizens of Dallas have suffered

some restrictions of access to the political processes with

in the city but that this restriction does not amount to

present dilution” (id. at 793), and that the “ restriction

of access which is present for the Mexican-Americans is

of a similar nature to that this Court has found to exist

for the black voters of. Dallas . . . .” {id.). Further, the

District Court found, “ At-large voting may operate in

part as a restriction of access for Mexican-Americans as

it has been for blacks” (id. at 794).

Nevertheless, in the absence of any specific supporting

findings of fact, the District Court concluded that an ex

clusive single-member district plan “ would do nothing”

to increase Mexican-American political participation, and

“might tend to decrease it” (id. at 793) (emphasis

added). Here the conclusions of the District Court are

difficult to understand. The District Court failed to

articulate how the position of the Mexican-Americans in

Dallas was any different from the position of Mexican-

Americans in San Antonio, where this Court found in

1973 that single-member districts were necessary to bring

27

the Mexican-American community “ into the full stream

of political life,” White v. Regester, supra, 412 U.S. at

769. Further, if as the District Court found, Mexican-

Americans were able to make political gains under the

at-large system as a result of their “ swing vote” posi

tion and through coalition politics in a community in

which they comprise only eight to ten percent of the

population, why wouldn’t their “ swing vote” position

be stronger in single-member districts in which they

would inevitably constitute a larger percentage of the

voters in several individual districts than they would

city wide?

Further, in reaching his conclusions, the District

Judge applied erroneous legal standards. First, for the

Mexican-American concern to fall under the “ singular

combination of unique factors” standard of Mahan, as

the District Court thought it did (id. at 794), the trial

court would have had to find either that single-member

districts would result in numerically malapportioned dis

tricts causing underrepresentation for the Mexican-

Americans, or that single-member districts would deny

Mexican-Americans their constitutional rights (cf. Ma

han, supra, 410 U.S. at 331-32). The District Court

made neither of these findings. Second, the District Court

thought the “ enhancing” standard justified retaining

three at-large seats (id. at 794) because of the Fifth

Circuit’s apparent holding in Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485

F.2d 1297, 1308 (5th Cir. 1973), that multi-member

districts are unconstitutional unless “ a district court de

termines that multi-member districts afford minorities a

greater opportunity for participation in the political

processes than do single-member districts.” However, this

Court has never sanctioned that notion, and in Zimmer

granted certiorari and affirmed “ but without approval of

the constitutional views expressed by the Court of Ap

peals” (East Carroll Parish, supra, 424 U.S. at 638).

28

Certainly the effect of any court-ordered redistricting

plan on minority groups not specifically represented by

the plaintiffs is a valid concern. But the District Court

here— because it failed to apply the correct legal stand

ard, and because its findings with regard to the Mexiean-

Amerieans are contradictory, speculative, and without

adequate support— failed to demonstrate that the position

of the Mexican-Americans justified an exception to the

Connor rule. Further, the Mexican-American community

in whose interest the three at-large seats ostensibly were

retained, have repudiated the notion that at-large voting

enhances their political participation, and have repre

sented that the experience of the 1975 municipal election

shows that the three at-large seats actually minimize and

cancel out their voting strength (551 F.2d at 1048).

(2) The Citywide Viewpoint.

The District Court did not find that at-large, citywide

representation on the city council constituted an “ un

usual circumstance” under the Connor rule, was neces

sary to efficient city administration, or that single-member

districts violated the defendant city officials’ constitu

tional rights, but only that three at-large seats were

“ desireable” [sic], a “ legitimate governmental interest,”

and a “benefit” (399 F. Supp. at 794-95). Here again,

the findings of the District Court are not sufficient to

sustain an exception to the Connor rule.

There is nothing “ singular,” “ unique,” “ unusual,” or

even “ special” about the city’s desire in this regard. In

most cases in which at-large voting has been struck down,

the officials of the state, county, or city submit plans to

the District Court which provide for the at-large elec

tion of all or some members of the governing body. See,

e.g., Connor v. Finch, supra (state legislature) ; Parnell

v. Rapides Parish Police Jury, 563 F.2d 180 (5th Cir.

1977) (parish governing body) ; Wallace v. House, 515

29

F.2d 619 (5th Cir. 1975), vacated ami remanded, 425

U.S. 947 (1976) (municipality). If the Court allows

an exception to the Connor rule on this ground, then it

would be tantamount to abolishing the rule entirely.

This Court has refused to allow an exception to the

Connor rule for this kind of argument. Last Term in

Connor v. Finch, supra, the Mississippi officials argued

that multi-member legislative districts should be pre

served in a court-ordered plan because of Mississippi’s

historic policy and because legislators need to represent

countywide interests, and single-member districts would

inevitably fracture county lines. This Court rejected that

contention, holding (431 U.S. at 415) :

The defendants’ unalloyed reliance on Mississippi’s

historic policy against fragmenting counties is in

sufficient to overcome the strong preference for

single-member districting that this Court originally

announced in this very case.

In Wallace v. House, 377 F. Supp. 1192 (W.D. La.

1974) , aff’d in part, rev’d in part, 515 F.2d 619 (5th Cir.

1975) , vacated and remanded, 425 U.S. 947 (1976), the

District Court struck down at-large elections for the

Board of Aldermen of the Town of Ferriday, Louisiana,

for dilution of black voting strength, and the town pro

posed two remedial plans, one providing for four aider-

men elected from districts and one at-large (the four/one

plan), and the second providing for the election of all

five aldermen from single-member districts (the five./zero

plan) (377 F. Supp. at 1199.) The District Court re

jected the four/one plan for the reasons (1) that if the

election of five aldermen at-large dilutes black voting

strength, then the election of one alderman at-large also

unconstitutionally abridges the right to vote (377 F.

Supp. at 1199-1200), and (2) any fairly drawn single

member district plan would create three majority black

districts and two majority white districts, while the four,/

30

one plan would deprive black voters of an additional seat

on the Board and give the Board a three-to-two white

majority (id. at 1200).

On appeal, the Fifth Circuit affirmed the District

Court’s findings of unconstitutional dilution, but reversed

as to remedy. Citing Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533

(1964), Burns v. Richardson, 384 U.S. 73 (1966), and

Chapman v. Meier, supra, to the effect that reapportion

ment is primarily a legislative responsibility (515 F.2d

at 634-36), the Fifth Circuit held that the District Court

failed to give heed to the “ rule of deference to state or

local legislative policies which are not unconstitutional”

{id. at 635).

All of the reasons given by the District Court here

in support of the eight/three plan were given by the

Court of Appeals in Wallace in support of the town’s

preferred four/one plan. First, the Fifth Circuit noted

that the “ reason usually given in support of at-large elec

tions for municipal offices is that at-large representa

tives will be free from possible ward parochialism and

will keep the interests of the entire city in mind as they

discharge their duties,” and while this has not always

served the interests of Ferriday’s black citizens, “we can

not say that the rationale is so tenuous that it can be

disregarded” (id. at 633.) Second, the Court of Appeals

found that the four/one plan was not unconstitutional,

and would in fact enhance black voting strength, be

cause while blacks were excluded from the Board under

the all at-large plan they would be able to elect two black

aldermen under the four/one plan, and therefore “ the

Board’s mixed plan is a great improvement” (id. at 632).

Third, the Fifth Circuit noted that at-large voting in

aldermanic elections had been the state policy of Louisi

ana since 1898, and was not rooted in racial discrimina

tion (id. at 633). Accordingly, the Fifth Circuit held

(id. at 636) :

31

We conclude that the trial court should have adopted

the mixed plan in deference to the Board of Aider-

men’s considered preference for a plan incorporat

ing one at-large place into the aldermanic election

scheme.

On petition for writ of certiorari, this Court granted

the writ, vacated the Fifth Circuit’s judgment, and re

manded to the Court of Appeals “ for further considera

tion in light of East Carroll Parish School Board v.

Marshall, 424 U.S. 636 (1976) . . 425 U.S. 947 (1976).

The clear implication of this Court’s order is that the

Fifth Circuit erred in failing to follow the Connor rule,

and that the reasons given by the appeals court for

deferring to the Board of aldermen’s preference— in

cluding their desire for citywide representation— were

insufficient to justify a departure from the preference

for single-member districts. On remand, the Fifth Cir

cuit found that no special circumstances existed which

would allow a departure from the principle expressed in

East Carroll Parish, 538 F.2d 1138 (5th Cir. 1976), and

this Court subsequently denied defendants’ petition for a

writ of certiorari, 431 U.S. 965 (1977).

The reasons given by the District Court in the case at

bar in favor of its eight,/three plan and the arguments

advanced by defendants in seeking reversal of the Fifth

Circuit’s judgment are virtually identical to those relied

upon by the Fifth Circuit in its first Wallace opinion,

which were rejected by this Court in vacating the Fifth

Circuit’s judgment and subsequently rejected by the Fifth

Circuit on remand. There are no findings by the District

Court or arguments advanced by defendants which would

justify a departure from the action taken by this Court

and subsequently by the Fifth Circuit in Wallace.

Moreover, there are good reasons why no departure

should be permitted here. First, as the Fifth Circuit

said on remand, “ The term, ‘special circumstances,’ en

32

compasses only the rare, the exceptional, not the usual

and diurnal,” 538 F.2d at 1144. The arguments made by

the city here are the usual arguments typically made in

these cases. Second, the District Court in this case found

— and these findings are not contested— that the at-large

representation which the city argues is necessary to pro

vide a citywide viewpoint on the city council is exactly

the same system which unconstitutionally denied the black

citizens of Dallas equal access to the political process and

operated to their detriment. Third, the overwhelming

benefits of single-member districts and their advancement

of an effective franchise so cogently outlined by the Court

in Chapman and Connor v. Finch are more than sufficient

to outweigh the city’s claimed interest in citywide repre

sentation.

III. ALTERNATIVELY, THE MIXED EIGHT/THREE

PLAN ORDERED INTO EFFECT BY THE DIS

TRICT COURT—BY RETAINING THREE AT-

LARGE SEATS—IS CONSTITUTIONALLY INADE

QUATE AS A REMEDY FOR UNCONSTITUTIONAL

AT-LARGE ELECTIONS.

Even if the Court determines that the remedial plan

at issue here is not a court-ordered plan governed by the

Connor rule, nevertheless the plan proposed by the Dallas

City Council is inadequate as a matter of law to cure the

constitutional violation conceded to exist. As this Court

noted in Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405,

418 (1975) :

[I] t is the historic purpose of equity to “ securfe]

complete justice,” Brown v. Swann, 10 Pet. 593

(1836) ; see also Porter v. Warner Holding Co., 328

U.S. 395, 397-98 (1946). “ [Wjhere federally pro

tected rights have been invaded, it has been the rule

from the beginning that courts will be alert to ad

just their remedies so as to grant the necessary

relief.” Bell v. Hood, 327 U.S. 678, 684 (1946).

33

Equity does complete justice and not by halves. Conse

quently, in cases involving racial discrimination affecting

the right to vote, this Court has held that

the court has not merely the power but the duty

to render a decree which will so far as possible

eliminate the discriminatory effects of the past as

well as bar like discrimination in the future.

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145, 154 (1965).