Wichita Falls Independent School District v. Avery Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

April 6, 1957

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Wichita Falls Independent School District v. Avery Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1957. b3460c17-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1378c146-4d90-43f5-974c-c8f03e866488/wichita-falls-independent-school-district-v-avery-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

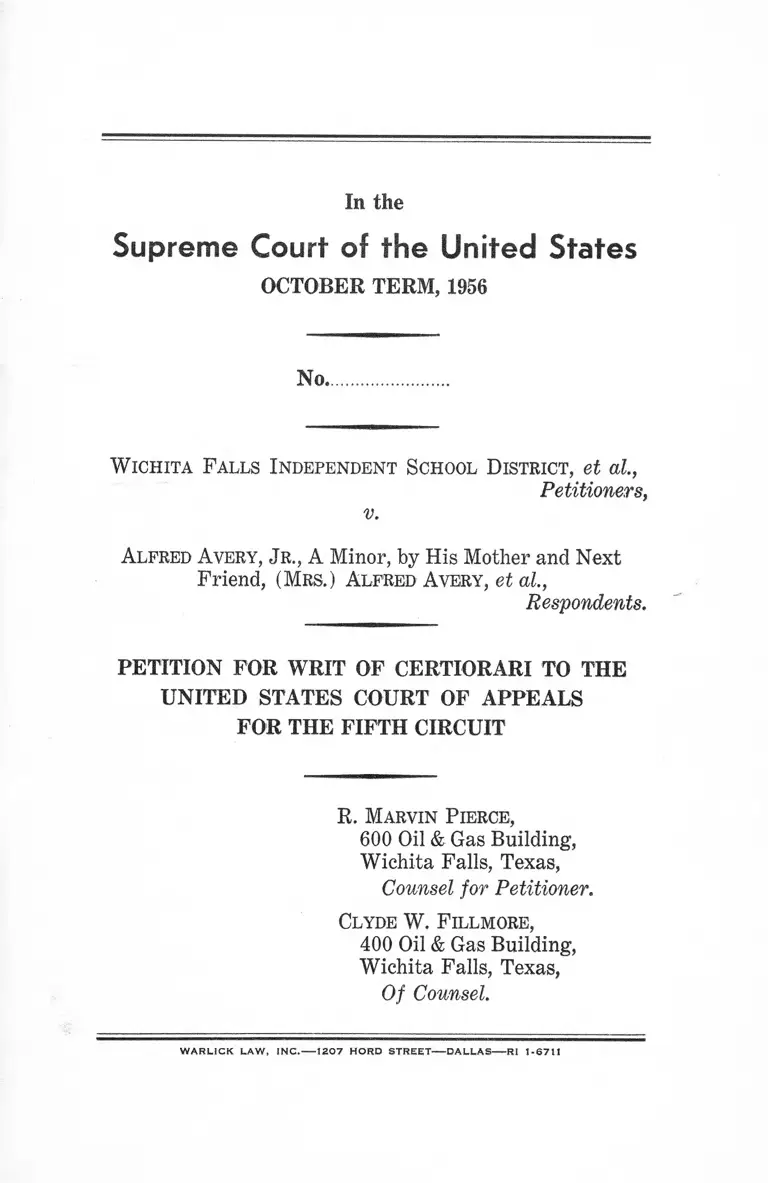

In the

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1956

No.

W ichita Falls Independent School District, et al,

Petitioners,

v.

Alfred Avery, Jr., A Minor, by His Mother and Next

Friend, (Mrs.) Alfred Avery, et al,

Respondents,

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

R. Marvin Pierce,

600 Oil & Gas Building,

Wichita Falls, Texas,

Counsel for Petitioner.

Clyde W. Fillmore,

400 Oil & Gas Building,

Wichita Falls, Texas,

Of Counsel.

W A R L 1 C K L A W , IN C .-----1 2 0 7 H O R D S T R E E T — -D A L L A S ----- R I 1 -6 7 1 1

I N D E X

Page

Opinions Below .............................................................. 1

Jurisdiction .............................................................. 2

Questions Presented ...................................................... 2

Statement......................................................................... 3

Reasons for Granting the Writ............................ 10

Conclusion ....................................................................... 15

Appendix ......................................................... 17-60

Opinion of Court of Appeals (R. 106-115)........... 17

Dissent of Justice Cameron (R. 117-143)............. 27

Affidavit of Joe B. McNiel— Appellees Exhibit

in Court of Appeals............................... 55

1 1 CITATIONS

Page

Cases

Brown, et al. v. Board of Education of Topeka,

349 U. S. 294; 99 L. Ed. 1083........................... 2, 3, 9,11

Brown, et al. v. Rippy, et al., 233 F. 2d 796.......... 13

Brownlow v. Schwartz, 261 U. S. 216....................... 9

Carson, et al. v. McDowell County, 227 P. 2d 789.... 12

Carson v. Warlick, 238 F. 2d 724............................... 12

Far East Conference v. United States,

342 U. S. 570.............................................................. 12

General American Tank Car Corp. v. El Dorado

Terminal Co., 308 U. S. 422-433............................... 12

Hecht Co. v. Bowles, 321 U. S. 321.............................13,14

Hood, et al. v. Sumter County, 232 F. 2d 636,

352 U. S. 870................................................................ 12

Jackson, et al. v. Rawdon, 235 F. 2d 93....................... 13

Martinez v. Maverick Co. Water Control Imp.

Dist., et al., 219 F. 2d 666........................................ 15

McKinney v. Blankenship, 282 S. W. 2d 691............... 5

Porter v. Warner Holding Co., 328 U. S. 395........... 13

Railroad Commission v. Pullman Co.,

312 U. S. 496................................................................ 12

Thomas v. The Pick Hotels Corp.,

224 F. 2d 664-666...................................................... 11

United States v. Moore, 340 U. S. 616........................... 13

United States v. Western Pacific Railroad Co.,

25 L. W. 4028............................................................ 12

United States v. W. T. Grant Co., 345 U. S. 633 9

Whitmore, et al. v. Stilwell, et al., 227 F. 2d 187 ... 13

Page

Miscellaneous

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure:

Rule 23(a) ................................................................... 15

Rule 54(c) .................................................................. 11

Rule 57 .............................................................. 3

CITATIONS— (Continued) iii

In the

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1956

No.

W ichita Falls Independent School District, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

Alfred Avery, Jr., A Minor, by His Mother and Next

Friend, (Mrs.) Alfred Avery, et al,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

Petitioner prays that a Writ of Certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fifth Circuit entered in the above cause on January

9, 1957.

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the District Court for the Northern Dis

trict of Texas (R. 94-96) is not reported, but appears in

the Transcript of the printed record on appeal at pages

2

94-96. The opinion (R. 101-115) and dissent (R. 117-143)

in the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit is not yet

reported, but is reprinted in the Appendix hereto at pages

17 and 27, respectively.

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit was entered on January 9, 1957 (R. 106-115), and

is reprinted in the Appendix at pages 17-26. The jurisdic

tion of this Court is invoked under 28 U. S. C. 1254(1).

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether, after a school board has in good faith taken

positive steps to comply with the Brown decision of this

Court and the Negro plaintiffs sought no tangible relief

that had not previously been granted them by the board

itself, the District Court may be required nonetheless to

retain the case on its docket indefinitely so that any future

complaints which these or other Negro school children or

their parents may have about the board’s conduct of school

administration may be heard in this suit?

2. Whether the District Court may be compelled to retain

jurisdiction of a controversy that has become moot for the

sole purpose of acting as a super school board in overseeing

the day-to-day administrative action of the duly elected

board in the conduct of the public school system.

3

STATEMENT

This suit was brought by the families of several colored

children early in December of 1955 (R. 15), who had

applied for admission to the Barwise School operated by

Petitioners, and were refused admittance on or about Sep

tember 7, 1955 (R. 18, 25 & 36). The complaint sought a

declaratory judgment and injunctive relief, temporary and

permanent. It asked that Defendants (Petitioners here) be

restrained from discriminating against all Negro minors

of public school age in depriving them their right to

register, enroll and receive instruction in the free public

elementary school in their community and nearest their

respective homes1 without any distinctions being made as

to them on the basis of their race and color, etc. (R. 11).

Petitioners here admitted the applicability of Brown v.

Board of Education of Topeka, 3b9 U. S. 29b, to their

school district (R. 16-17). They had chosen to comply (R.

20); had made a start (R. 21) ; and had definite plans to

effect desegregation of all schools operated by them within

a matter of months (R. 21) ; and they admitted the author

ity of the court to grant any injunctive relief to which

plaintiffs might prove themselves entitled.

Defendants (Petitioners here) denied the right of plain

tiffs to declaratory judgment under Rule 57 (R. 16)1 2;

defendants also denied that the named plaintiffs might

1 (Emphasis added.) See R. 11.

Petitioner contended and contends that all Plaintiff’s propositions

were already determined by the school segregation cases which are stare

decisis thereto.

4

properly represent all other Negro minors categorized “as

all other colored children” 3 (R. 17-18).

The basic facts which are not in dispute are as follows:

The schools operated by the Wichita Falls Independent

School District opened on September 7, A. D. 1955 (R. 5).

Complainants, or presumably some of them, were among

the families of several colored children who applied for

admission to Barwise School that day and were referred to

Booker T. Washington School (R. 18, 25 & 36). They were

told why they could not be admitted to Barwise until the

completion of the Sunnyside Heights School (named Lamar

School) (R. 18, 25, 36 & 37).

Of the schools operated by the Wichita Falls Independent

School District, only the Sheppard Air Force Base School

was opened on a non-segregated basis (R. 5, 21, 43, 54, 55,

61, 62, 65, 67, 72 & 76) and was attended by both colored

and white students (R. 43). This was pursuant to the

action of the School Board on July 11, 1955, rescinding its

former action of January 21, 1955, and electing to operate

Sheppard Air Force Base Elementary School on a non-

segregated basis for the school year of 1955-56. The Board

gave as its reasons for doing so this Court’s decree on

segregation together with the pronouncement of the State

Board of Education of Austin, Texas, as to the eligibility

of integrated schools to receive state funds (R. 46, 55, 63

& 64).

3Petitioner contended and contends that no legal rights or relations of

the actual parties in controversy existed because individual Plaintiffs,

as well as all the actual class they might conceivably have represented,

had already been admitted in the school to which they sought admission.

5

Sunnyside Heights Addition is a new addition situated

a considerable distance south of the Barwise School, but in

the old Barwise School District (R. 20). A new elementary

school called Lamar School was under construction in such

addition (R. 80). During the summer of 1955, the bound

ary lines had been re-drawn dividing old Barwise District

in anticipation of the opening of Lamar School in Septem

ber (R. 81). The old Barwise School had been re-named

A. E. Holland School at the recommendation of a commit

tee of Negro citizens. This was prior to the notification by

the State Board of Education that the payment of State

School aid might be applied to integrated schools (R. 63 ).4

Due to rains and shortage of materials, the completion of

the Sunnyside Heights Addition Elementary School (Lamar

School) was delayed and all white students in the old Bar-

wise District (including the new Sunnyside Addition) had

to attend Barwise School temporarily (R, 80 & 81). It was

very crowded (R. 76).

Lamar School was completed December 29, 1955, and on

January 4, 1956, all students then attending the old Bar-

wise School were transferred to Lamar School to attend

classes while the Barwise School building was re-condi-

tioned to receive students beginning January 23, 1956 (R.

20 & 27).

Complainants filed this suit in December of 1955 (R. 15)

and Defendants answered on January 6, 1956.

4The case of McKinney v. Blankenship, 282 S. W. 2d 691, declaring

unconstitutional certain sections of the state laws and constitutions re

quiring segregated schools was not entered until October 12, 1955.

6

On January 23, 1956, all qualified applicants, colored or

white, who applied for admission to Barwise School, re

named A. E. Holland School, were admitted (R. 28 & 35)

and it was opened on a desegregated basis (R. 28, 50, 74

& 76). No white children registered in the school (R. 65).

On or about March 22, 1956, Petitioners here, as Defend

ants in such cause, filed a Motion to Dismiss Complaint or

for Summary Judgment in the alternate with affidavits

attached (R. 22, 28 & 29) to which on or about the 26th day

of March, 1956, Complainants responded with a Motion to

Strike Defendants’ Motion to Dismiss or for Summary

Judgment (R. 29-31).

At the time of the hearing in the United States District

Court on April 3, 1956, there were known to be white

families living in the A. E. Holland District (R. 64 & 75),

but there were no white children going to A. E. Holland

(Barwise) School (R. 64-65). It was not known whether

the white families had any children of school age (R. 50 &

65), but if they did, such children could have attended

Holland School (R. 43 & 65). Although there is a liberal

transfer policy (R. 64 & 71-72), in January, 1956, no white

children had come to the superintendent and asked to be

transferred out of the A. E. Holland (Barwise) District

(R. 75). They might have transferred automatically to

Lamar School (in the Sunnyside District) earlier in Janu

ary to permit renovation of the Barwise building, and failed

thereafter to return to A. E. Holland (R. 27, 43 & 65).5

5It is noted per Appendix page 59 that in September of 1956 when all

schools were opened on a desegregated basis only one white student re

quested and was granted transfer from A. E. Holland District while six

colored students requested and were granted transfers therefrom.

7

The District Court, on April 3, 1956, overruled Com

plainants’ Motion to Strike Defendants’ Motion to Dismiss

or for Summary Judgment (R. 32), but, nevertheless, did

not perfunctorily grant Defendants’ Motion to Dismiss or

for Summary Judgment. Rather, the Court allowed Com

plainants to introduce their evidence in support of their

case (R. 33). After hearing the pleadings, the testimony of

witnesses, and argument of counsel, the Court requested of

counsel for the Complainants (Respondents here), “What

relief do you contend your case seeks in behalf of these

individual Plaintiffs?” (R. 82). Thence, followed a colloquy

between the Court and Counsel (R. 83-93) wherein Counsel

for Complainants insisted on a declaration and restatement

of the law (R. 83); injunctive relief (R. 83 & 87) in sub

stantial accordance with their prayer (R. 84 & 87) ; that

“ this is not a suit for a ruling as to how one Barwise

School shall be administered; it is a suit for the determi

nation of how all the schools in this district shall be

administered” (R. 85) ; that it was his opinion that as far

as the law is concerned, they (complainants) would be in

a much better position if they had been excluded (from

A. E. Holland School on January 23, 1956). Throughout

this colloquy the Court repeated his efforts to determine

what specific relief Complainants sought in behalf of them

selves, and apparently, in behalf of other colored students

in the A. E. Holland District (old Barwise School) (R. 83,

84, 86, 89, 92 & 93).

The District Court concluded (R. 94) that the School

Boards have the primary responsibility for compliance and

8

that while he felt the Courts “ have a responsibility and if

it becomes necessary that the Courts intervene with all the

sanctions and coercions at law, that will have to take

place,” but that he thought it would be premature for the

Court to interfere at this time (R. 94 & 95). He felt that

progress had already been made (R. 96) and that the

schools had a declared purpose and policy to carry out

desegregation in the schools of the district during the next

school term, and that the specific grievance alleged by the

Plaintiffs from being denied entrance to Rarwise School

had now become moot (R. 96). This was followed by Plain

tiffs’ (Respondents herein) Motion to Amend Judgment

and enter specific findings of fact and conclusions of law

on April 6, 1956, and the Court’s Order of April 19, 1956,

denying such motion.

On appeal, the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit,

with benefit of the full record of proceedings below (R.

103), made the following observations and conclusions:

That Defendants (Petitioners herein) administering

schools enrolling more than 13,000 pupils, had not com

pletely desegregated such schools at the time of the trial

in the District Court (R. 109) ; that Plaintiffs may main

tain a class action (R. 110); that the District Court had

not abused its discretion in declining to enter a decree

declaring the rights of the parties or enjoining against

discrimination (R. 112) ; that the School Board had the

primary responsibility and the District Court, the discre

tion, to withhold action when convinced that the Board had

9

made a prompt and reasonable start and was proceeding

toward good faith compliance (R. 113); that at the time

of the judgment in the District Court, the case had not

become moot and that it was error to dismiss the action

(R. 113); that the voluntary cessation of illegal conduct6

does not make a case moot unless the Court also finds that

there is no reasonable probability of return of illegal con

duct, etc.,7 and that it can not be claimed that appeal has

become moot through compliance with the proper decree

(R. 114); although it is true that as far as the law is

concerned, no question is presented on appeal which has not

already been settled by the school segregation cases (R.

114) ; that the facts may be subject to more than one inter

pretation, and that Appellants (Respondents herein) have

questioned whether the desegregation existing in most

schools is in fact voluntary8 (R. 114) ; that at the time of

trial in the District Court, what the school board had done

were steps, but no more than steps toward compliance (R.

114); that this Court in Brown v. Topeka, 31±9 U. S. 29i,

had directed that during the transition period the District

Court should retain jurisdiction (R. 114).

eThe Court apparently presumes that Petitioners’ conduct up until

the time that all its schools became desegregated was illegal. Petitioners

question this where school boards acknowledged their obligation to de

segregate and are acting in good faith with all deliberate speed (em

phasis added).

7The Circuit Court cited United States v. W. T. Grant Co., 3U5 U. S.

633, and Brownlow v. Schwartz, 261 U. S. 216, in support of its stated

version of the holdings of such cases. Petitioners note that such version

is inverted and not only presumes illegality of the administrative actions

of the school board, but bad faith and the probability of the return to

such illegal conduct (emphasis added).

Petitioners find no reference to the word “voluntary” in the Brown v.

Topeka case. Presumably, its use was intended to have some bearing on

good faith or the cessation of illegal conduct pending appeal. In either

event, it hardly seems a proper measure for the discretionary responsi

bilities of public administrative bodies.

10

Thence, the Judgment of the District Court was reversed

with directions that “ the District Court should retain

jurisdiction for the entry of all judgments and orders

necessary to ascertain, or else to require, good faith com

pliance.”

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

The decision below should be reviewed because a divided

Court of Appeals in the circuit most immediately concerned

with the problems of segregation in public schools has,

although upholding the District Court’s lawful discretion

to determine the need for application of equitable remedies,

nevertheless, remanded the cause to such District Court

to be retained on the docket indefinitely. It was not re

manded in such a manner as to afford Complainants relief

beyond that which had already been granted them by

administrative action of the School Board. It was remanded

in such a manner as to afford a forum for Negro people

to seek constant judicial review of daily acts of the school

administrators. The District Judge had found the cause

moot as to the individual Complainants9 and premature in

its prayer for judicial intervention in school affairs in

behalf of other colored students. He now finds this cause

9Although the Court used the term moot, the complaint was obviously

dismissed because the Court was unable to find any practical equitable

relief to grant the individual complaints or even the actual class (other

colored students eligible to attend Barwise). See colloquy, Page 8, supra

(R. 88-93). (Emphasis added.)

11

on his docket for inquisitorial10 determinations that can

result only in his judicial supervision of the discretions of

the administrative agency created by the laws of the State

of Texas to conduct public schools.

1. The decision of the Court of Appeals erroneously inter

prets the holding of this Court in the case of Brown, et al.

v. Board of Education of Topeka, et al., 3J+9 U. S. 291* so

as to disrupt the orderly administration of the schools by

the School Boards that are lawfully and necessarily charged

with the responsibility for their management. By such

interpretation, the case at bar has ceased to be concerned

with the particular wrongs involved in the specific facts

alleged and presented in the District Court,11 and has been

transformed into an open forum to which may be directed

all present and future complaints by, presumably, any col

ored pupil in the Wichita Falls public schools. In this case,

the Defendants (Petitioners herein) have taken all lawful

steps available to them12 to effect desegregation of the

schools operated by them. The District Court, with no

guidance whatsoever from the Court of Appeals, is now

obligated to make future determinations and exercise fu

ture discretions in its retained jurisdiction (R. 114) over

“ This term was referred to by Justice Ben F. Cameron in his Dissent

in this cause, filed January 25, 1957 (R. 123). The Court’s own words

would seem to imply that the District Court should order some type

hearing and investigation for the purpose of ascertaining whether Peti

tioners have in good faith complied with this Court’s mandate in the

segregation cases (R. 115). (Emphasis added.)

11 Rule 54(c) F. R. C. P. enlarges the relief which may be granted

beyond the askings of prayer for relief; but it does not permit relief to

be granted beyond that justified by the facts pleaded and proved. Thomas

v. The Pick Hotels Corporation, 10 Cir., 1955, 224 F. 2d 664, 666.

“ Other than to attempt to require mandatory attendance by colored

children into schools in districts in which they reside despite their written

requests for transfer. (App. 60.)

12

matters not covered by the pleadings, proof, affidavits, or

exhibits, and which by their very nature must be based on

future rights of persons within an alleged and undesig

nated class seeking relief. Inevitably, this must include

matters which properly should be considered by the School

Board in exercising its discretions and performing its ad

ministrative function in the operation of the public

schools.18

The net effect of the opinion of the Court of Appeals in

these respects is clearly in conflict with the holdings of this

Court in the cases of Railroad Commission v. Pullman Co.,

312 U. S. 196, and more recently, United States v. Western

Pacific Railroad Co., 25 L. W. 1028, and cases cited there

in,13 14 as well as with segregation cases decided by the Court

o f Appeals for the Fourth Circuit.15 The Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit makes no mention of the Federal

Court’s obligations not to intervene in administrative af

fairs unless and until bad faith is shown, or available

administrative remedies have been exhausted. Rather, bad

faith appears to be presumed, in school segregation cases,

for purposes of such intervention. This matter was graph

ically pointed out by Justice Ben F. Cameron in his Dis

13Apparently the District Court must hear complaints of whatever

nature, e.g., note court’s reference to “voluntary” (R. 114) per footnote

8, supra. It can be reasonably anticipated that Plaintiffs’ attorney will

attempt to use the pending case as a place in which to lodge complaints

which properly should be made to the school board. Note questions and

testimony in connection with teachers’ salaries (R. 59).

14See e.g., General American Tank Car Corp. v. El Dorado Terminal

Co., 308 U. S. 422, 433, and Far East Conference v. United States, 342

U. S. 570.

15See e.g., Carson, et al. v. McDowell County (N. C.), 4 Cir., 1955,

227 F. 2d 789; and Hood, et al. v. Sumter County (S. C.), 4 Cir., 1956,

232 F. 2d 636, cert. den. 352 U. S. 870; and Carson v. Warlick, 238 F.

2d 724, cert. den. Mar. 25,1957.

13

sent (R. 117 & 143), who also comments that such con

flict exists not only in the case at bar but in all other

recent Fifth Circuit opinions pertaining to segregation

matters.16

2. The Court of Appeals, as its authority for requiring that

the District Court retain jurisdiction, cited this Court’s

opinion in Brown, et al. v. Board of Education of Topeka,

et al., 31*9 U. S. 291* (quoting the last sentence of Headnote

10 of the 99 L. Edition 1083 citation thereof). To assume

that this Court intended thereby to require mandatory

retained jurisdiction in such a situation as that ordered

by the Court of Appeals in the case at bar would appear

to presume some type illegality during the transitional

period as well as to ignore the good faith of Petitioners

in commencing and carrying forward the program of

desegregation and in declaring their intention to desegre

gate all schools in good faith and with deliberate speed

(R. 94, 95 & 96).

The Supreme Court, in the Brown case, supra, cited

Hecht Co. v. Bowles, 321 U. S. 321, as a guide for determi

nation of traditional equitable principles. In such case, this

Court considered whether the legislature, by the use of the

term “other order,” 17 had directed that the District Court

lfiSee e.g., Whitmore, et al. v. Stilwell, et a l (Texarkana), 1955, 227

F 2d 187; Brown, et al. v. Rippy, et al. (Dallas), 1956, 233 F. 2d 796;

and Jackson, et al. v. Rawdon, et al. (Mansfield), 1956, 235 F. 2d 93—

all with certiorari denied.

^Section 205(a) of the Emergency Price Control Act of 1942 provided

that “ a permanent or temporary injunction, restraining order, or other

order” be granted. Even the subsequent cases of Porter v. Warner

Holding Co., 328 U. S. 395 and United States v. Moore, 3A0 U. S. 616,

in defining additional equitable remedies contemplated by Congress as

“ other orders” did not appear to contemplate retained or continuing juris-

ictioyi as one of the remedies. (Emphasis added.)

14

should have issued an order “ retaining jurisdiction.” But

this Court appeared to feel that the utilization of retained

jurisdiction would have been a matter for the discretion

of the District Court,18 whether authorized by such statute

or not, and was a coercive remedy in itself. Even assuming

that this Court in the case of Brown v. Board of Education

of Topeka, et al., 349 U. S. 294 intended to confer the

“ retained or continuing jurisdiction” remedy as an addi

tional discretionary equitable remedy (by citing Hecht Co,

v. Bowles, 321 TJ. S. 321) on the one hand, it is unlikely

that it intended to direct its use mandatorially until com

plete integration is achieved on the other (emphasis added)

except in the specific circumstances therein set out.

3. These are questions of grave and national concern and

the jurisdictional and procedural problems raised by this

petition are not merely interesting legal questions. They

involve the very essence of the manner and means of deseg

regation of the public schools pursuant to the principles

promulgated in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka,

34,9 U. S. 294. The opinion of the Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit has modified or hypothecated accepted and

established legal and equitable principles in relation to

isit is noted in the case at bar that the District Court was not unmind

ful of the versatility of the remedies available to him for after referring

to the Brown v. Topeka cases, the Court stated (R. 94-95), “ The Courts,

of course, have a responsibility and if it becomes necessary that the

Courts intervene with all the sanctions and coercions of the law, that

will have to take place.” Note also the indication of future use in the

event of specific complaints after a reasonable period. (Emphasis

added.)

15

mootness19 and class actions20 in such a manner that they are

apparently inapplicable to school segregation actions. The

need for maintaining a proper relationship between the

federal courts and public school authorities has been disre

garded and discretions of the school board have been made

servient to equitable coercions. Even the federal district

courts are apparently no longer the determiners of the

facts in segregation matters whenever equitable interfer

ence in school board administration is involved, although

the law may be settled (R. 114).

CONCLUSION

In efforts to effectuate and/or protect newly declared

rights of a minority, appellate courts must not, through

inadvertence, or for expediency, disregard or materially

alter and extend accepted jurisdictional and equitable prin

ciples and court procedural practices. In efforts to protect

the equality of a minority class, we must not create, in the

Fifth Circuit, a special class not bound by conventional

principles which require maintenance of a proper and re

spectful relationship between courts and administrative

agencies. These matters are of such far-reaching import

ance that they deserve serious consideration by this court.

For these reasons, it is respectfully submitted that this

Petition for a Writ of Certiorari should be granted, that

the opinion of the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

19See Footnote 7, Page 10, supra.

20Martinez v. Maverick County Water Control Imp. Dist., 219 F. 2d

666. Rule 23(a) F. R. C. P.

16

should be in these respects reversed and that the opinion

of the District Court for the Northern District of Texas

should be affirmed.

R. Marvin Pierce,

600 Oil & Gas Building,

Wichita Falls, Texas,

Counsel for Petitioner.

17

APPENDIX

[R-106] In the

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 16,148

Alfred Avery, Jr., A Minor, by his Mother and Next

Friend, (Mrs.) Alfred Avery, et al,

Appellants,

v.

W ichita Falls Independent School District, et al,

Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Northern District of Texas

(January 9, 1957.)

Before RIVES, TUTTLE and CAMERON, Circuit. Judges.

RIVES, Circuit Judge: This action was brought by

twenty negro children of public school age, residents of

the Wichita Falls Independent School District, as a class

action, the complaint averring,

“4. Minor plaintiffs bring this action by their next

friends in their own behalf, and on behalf of [R-107] all

other Negro minors who are similarly situated because

18

of race or color within the defendant Wichita Falls In

dependent School District. They allege that they are

members of a general class of persons who are segre

gated and discriminated against by order of the de

fendant board of trustees of the defendant Wichita

Falls Independent School District because of their race

and color; that the members of the class are so numer

ous as to make it impracticable to bring all of them

before this Court; that they, as members of the class,

can and will fairly represent all of the members of the

class; that the character of the right sought to be

enforced and protected for the class is several and that

there is a common question of fact and law affecting

the several rights of all and a common relief is sought,

and that they bring this action by their next friends

as a class action pursuant to Rule 23(a) (3), of the

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.”

The prayer was for a declaratory judgment as to the

rights and privileges of the class, and that the defendants

be enjoined from denying to the minor plaintiffs and the

members of the class of persons they represent the right

and privilege of attending the public elementary school

nearest their respective homes “ under the same conditions

and circumstances and without any distinctions being made

as to them on the basis of their race or color.”

The defendants moved to dismiss the complaint and in

the alternative for a summary judgment, and the court dis

missed the complaint stating in its order of dismissal that:

“ taking into consideration all of the proof, the declared

purpose and policy of the defendants to [R-108] carry

out desegregation in the schools of the District during

the next school term, the progress already made and

the definite prospect that such voluntary adjustment

will be accomplished within a matter of months, it

19

appears to the Court that judicial intervention under

the equity powers at this time would be premature or

inadvisable, and the Court is also of the opinion that

the specific grievance alleged by the plaintiffs, from

being denied entrance at the Barwise School, has now

become moot,”

The negro population in the Wichita Falls Independent

School District lived largely in one single concentrated

area. At the time the action was filed, some fourteen to

sixteen negro children along with 680 white children at

tended the Sheppard Air Force Base Elementary School

which was operated on a non-segregated basis,3 and nearly

all other negro pupils in the Wichita District, slightly over

a thousand, attended the Booker T. Washington School, a

school operated for negroes only. The answer admitted that,

“ Present statistics indicate that there are approxi

mately 140 colored students who should be admitted

to Barwise school if the district comprises a compact

unit situated within its natural access boundaries.”

In addition there were still other negro children of school

age, about seventeen in number, residing within the areas

served by various other schools in the Wichita District, but

who were “automatically” transferred to the [R-109]

Booker T. Washington School. Altogether more than 13,000

pupils were enrolled in the schools of the Wichita Falls

Independent School District. No negro child was going to

any school other than the Booker T. Washington School

and Sheppard Air Force Base School.

ilt had been desegregated at the request of the United States Depart

ment of Health, Education and Welfare.

20

The plaintiffs lived in the area served by the Barwise

School. At the opening of the school term in September,

1955, they applied for admission to that school and it is

admitted that they were refused on racial grounds. The

Barwise School was then being attended by white children

only, but a new school was under construction in Sunny-

side Heights, a white section of the town, to which it was

planned to transfer the white pupils. The new school had

been scheduled for completion by September, 1955, but was

not actually completed until January, 1956, after the

present suit had been filed. The white pupils were then

transferred from Barwise to the new school; Barwise was

renamed the A. E. Holland School after a former negro

principal of the Booker T. Washington School, and was

opened on a nominally desegregated basis though only

negro pupils, including the minor plaintiffs, registered.

The Superintendent of Schools testified that a start had

been made toward desegregating the schools because the

Sheppard Air Force Base School had been desegregated

and was attended by white children and by some fourteen

to sixteen negro children, and because the A. E. Holland

School was legally desegregated though actually attended

by negro children only, and, further, that it was the inten

tion of the Board to completely desegregate [R-110] the

entire district “ at the earliest feasible moment,” that “by

the beginning in September of this, of 1956, we will have

a very good beginning; and by midterm of 1957 it’s alto

21

gether possible that the entire school system could be

desegregated.”

Clearly plaintiffs seeking judicial relief from racial dis

crimination applied against the members of a numerous

class may maintain a class action.2

At the time the district court dismissed the complaint,

a part of the plaintiffs’ prayer had been met, that is they

were attending the public school nearest their homes, but

it is by no means certain that they had the same free

privilege of transfer to or attendance on any school of their

choice as was accorded the white children. Admittedly

desegregation of the schools of the district had not then

been completed, though the defendants professed such a

purpose, and the court thought that it would be accom

plished “within a matter of months.”

Upon this appeal, the appellees have attached as an

exhibit to their brief an affidavit of the‘Superintendent of

Schools to the effect that the 1956 summer session of

the Wichita Falls Senior High School was non-segregated

and was actually attended by 411 white and 15 negro

children; that, on September 5, 1956, all pupils were ad-

[R - l l l ] mitted to the schools to which they applied for

admission without any discrimination because of their

2Rule 23, F. R. C. P.; The School Segregation Cases, 347 U. S. 483,

495; Beal v. Holcombe, 5th Cir., 193 F. 2d 384; Frasier v. Board of

Trustees of University of North Carolina, 134 F. Supp. 589, 593, affirmed

per curiam 350 U. S. 979; Holmes v. City of Atlanta, N. D. Ga., 124 F.

Supp. 290, 293, affirmed 5th Cir., 223 F. 2d 93, modified and remanded

350 U. S. 879; Kansas City, Mo. v. Williams, 8th Cir., 205 F. 2d 47, 51,

52; Wilson v. Board of Supervisors, E. D. La., 92 F. S. 986, a ff’d per

curiam, 340 U. S. 909.

22

color, though no negro children applied for admission to

any school except Sheppard Air Force Base School, Booker

T. Washington School and A. E. Holland School. The appel

lees urge upon us that, if not moot at the time the district

court dismissed the complaint, the cause has now become

moot and that the appeal should be dismissed or that the

judgment of the district court should be affirmed.

The appellants, on their part, deny that the public schools

within the Wichita Falls Independent School District have

actually and in good faith been desegregated, and insist

that, it being undisputed that when the complaint was filed

the defendants had denied to the plaintiffs solely on ac

count of their race the right to attend the school of their

choice, a claimed cessation of such unlawful conduct would

not render the action moot nor justify its dismissal.3

The Constitution as construed in the School Segregation

Cases, Broivn v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, 349

U. S. 294, and Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497, forbids

any state action requiring segregation of children in public

schools solely on account of race; it does not, however,

require actual integration of the races. As was well said

in Briggs v. Elliott, E. D. So. Carolina, 132 F. Supp. 776,

777:

“ * * * it is important that we point out exactly what

the Supreme Court has decided and what it [R-112]

3For this position, the appellants cite and rely on the following cases:

United States v. Freight Ass’n., 166 U. S. 290; United States v. U. S.

Steel Corp., 251 U. S. 417; Trade Comm’n v. Goodyear Co., 304 U. S.

257; Walling v. Helmerich & Payne, 323 U. S. 37; United States v.

Oregon Med. Soc., 343 U. S. 326; United States v. W. T. Grant Co., 345

U. S. 629.

23

has not decided in this case. It has not decided that the

federal courts are to take over or regulate the public

schools of the states. It has not decided that the states

must mix persons of different races in the schools or

must require them to attend schools or must deprive

them of the right of choosing the schools they attend.

What it has decided, and all that it has decided, is that

a state may not deny to any person on account of race

the right to attend any school that it maintains. This,

under the decision of the Supreme Court, the state may

not do directly or indirectly; but if the schools which

it maintains are open to children of all races, no viola

tion of the Constitution is involved even though the

children of different races voluntarily attend different

schools, as they attend different churches. Nothing

in the Constitution or in the decision of the Supreme

Court takes away from the people freedom to choose

the schools they attend. The Constitution, in other

words, does not require integration. It merely forbids

discrimination. It does not forbid such segregation as

occurs as the result of voluntary action. It merely for

bids the use of governmental power to enforce segrega

tion. The Fourteenth Amendment is a limitation upon

the exercise of power by the state or state agencies,

not a limitation upon the freedom of individuals.”

Keeping that principle in mind, we cannot say that the

district court abused its discretion in declining to enter

a decree declaring the rights of the parties or enjoining

against discrimination. The primary responsibility rested

upon the Board, and the district court had the dis- [R-113]

cretion to withhold action when convinced that the Board

had made “a prompt and reasonable start” and was pro

ceeding to a “good faith compliance at the earliest prac

ticable date.” 4 Such start and continuation were steps, but

4Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294, 300.

24

no more than steps, toward compliance, and, until that goal

was reached, the plaintiffs and the class represented by

them would be denied their constitutional right to be free

from state imposed discrimination because of their race or

color. In the Brown Case, supra, it appeared that,

“ The presentations * demonstrated that substantial

steps to eliminate racial discrimination in public

schools have already been taken, not only in some of

the communities in which these cases arose, but in

some of the states appearing as amici curiae, and in

other states as well. Substantial progress has been

made in the District of Columbia and in the communi

ties in Kansas and Delaware involved in this litiga

tion.” 349 U. S. at p. 299.

The Court nevertheless directed that, “ During this period

of transition, the courts will retain jurisdiction of these

cases.” 349 U. S. at p. 301. See also, Brown v. Rippy, 5th

Cir., 233 F. 2d 796.

We are of the clear opinion that, at the time of the ren

dition of judgment by the district court, the case had not

become moot and that it was error to dismiss the action.

The cases relied on by appellants establish the propo

sition that voluntary cessation of illegal conduct does

[R-114] not make the case moot. If, however, in addition,

the court finds that there is no reasonable probability of a

return to the illegal conduct, and that no disputed ques

tion of law or fact remains to be determined, that no

controversy remains to be settled, then it should not ad-

25

judieate a cause which no longer exists. United States v.

W. T. Grant Co., supra, 345 U. S. at 633; Brotvnlow v.

Schwartz, 261 U. S. 216. It cannot be claimed that the

appeal has become moot through compliance with a proper

decree. Instead, the claim is that the entire case has be

come moot through cessation of the unlawful conduct. Ordi

narily, such a claim should be considered by the trial

court in the first instance. It is said, however, that in

so far as the law is concerned no question is now pre

sented which has not already been settled by the School

Segregation Cases, supra, and that is true. The facts, on

the other hand, may be subject to more than one inter

pretation. The appellants question whether the actual

segregation existing in most of the schools is, in fact,

voluntary. Events which have occurred since the judg

ment of dismissal, or which may occur in the future may

constitute “good faith compliance,” but, in the present cir

cumstances, that question should not be determined by

this Court on the basis of ex parte affidavits; such an

issue depending largely on the good faith of the defend

ants can be better decided by the district court after a

full and fair hearing. “ Because of their proximity to local

conditions and the possible need for further hearings, the

courts which originally heard these cases can best perform

this judicial appraisal.” Brown v. Board of Education,

supra at p. 299. The district court should retain jurisdic

tion for the entry of all judgments and orders [R-115]

26

necessary to ascertain, or else to require, “good faith

compliance.”

The judgment is, therefore, reversed and the cause

remanded.

REVERSED AND REMANDED.

JUDGE CAMERON DISSENTS.

A True Copy:

Teste:

JOHN A. FEEHAN, JR., Clerk

By / s / Clara R. James

Clerk of the United States Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.

27

APPENDIX

[117] In the

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 16,148

Alfred Avery, Jr., A Minor, by his Mother and Next

Friend, (Mrs.) Alfred Avery, et al,

Appellants,

v.

W ichita Falls Independent School District, et al,

Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Northern District of Texas

(January 25, 1957.)

Before RIVES, TUTTLE and CAMERON, Circuit Judges.

CAMERON, Circuit Judge, Dissenting:

I concur in much which is said in the majority opinion

and think its reasoning ought to lead to an affirmance of

the act of the Court below in dismissing the complaint

following its decision on the merits by summary judg-

28

[R-118] ment. But I cannot go along with the majority’s

action in remanding the case with instructions that it re

main on the docket. The inevitable result of such a course

is to thrust back into the field of controversy a problem

which can, in my opinion, move towards real solution only

in an atmosphere of repose and harmony. I am constrained

to set down some of the reasons for my dissent because

they are based upon fundamental disagreement with the

thinking of my colleagues as to the mission and true com

petence, in segregation cases, of federal courts generally

and of this Court in particular.

Historical principles of equity combine with recent

Supreme Court decisions to establish these basic tenets:

(a) that school boards and local officials, as administrative

agencies, should be given full primary responsibility and

authority with the unfettered and unembarrassed oppor

tunity to work out problems in the light of local conditions;

(b) that federal district courts should intervene only after

the exhaustion of the administrative remedy; and should

grant injunctions only in those cases where it is demon

strated that the general good of the public, including the

litigants, will be served; and (c) that this Court should set

aside judgment based upon the superior knowledge by dis

trict judges of local conditions only in rare instances where

it is clear that they have misconceived or misapplied the

law or have been guilty of plain abuse of discretion. This

decision, and others like it recently rendered by this Court

do not, in my judgment apply these fundamental and defi

nitely established principles.

29

[R-119] I.

(a) It cannot, in my judgment, be doubted that the main

hope of solving the difficult problems before us rests with

local school boards. The Supreme Court recognized this1

and gave expression to this postulate in the second Brown

decision: “ Full implementation of these constitutional prin

ciples may require solution of varied local school problems.

School authorities have the primary responsibility for

elucidating, assessing and solving these problems * *

[Emphasis added.]

It is our duty, under authorities which will be discussed,

to assume that school boards are constituted of men of

wisdom, judgment and dedication; and to view their actions

in a spirit of trust and tolerance, not tinctured with sus

picion. Dean Griswold, of the Harvard Law School has

said:2 “ The courts do not have the sole responsibility for

the proper conduct of our government.” And Mr. Justice

Stone expressed the same idea:3 “ Courts are not the only

agency of government that must be assumed to have capac

ity to govern.” So much of the business of the country is

conducted by administrative bodies that courts commit, in

my opinion, egregious error when they do not credit their

actions as the product of an equal co-ordinate branch of

government equally devoted to the public service. The Su

preme Court has said of the rela- [R-120] tionship between

1The Segregation Cases, as morally referred to by the Supreme Court,

are Brown, et al. v. Board of Education of Topeka, et al., May 17, 1954,

347 U. S. 483 (known as first decision); and same case, May 31, 1955,

349 U. S. 294 (known as second decision).

2The Fifth Amendment Today, p. 40.

3297 U. S., p. 87.

30

the courts and administrative bodies4 that “neither can

rightly be regarded by the other as an alien intruder, to be

tolerated if must be, but never to be encouraged or aided

by the other in the attainment of the common aim.”

(b) The findings of administrative bodies have uniform

ly been held by the courts in great respect and considered

presumptively correct.5 This Court has heretofore been dis

posed to adhere strictly to the proposition that school and

similar boards should be invested with full and unshackled

power to act and that courts should not intervene until

exhaustion of their administrative functions.6

(c) In dealing with administrative action by State Offi

cers it is helpful to keep in view constantly the much-quoted

language of the Supreme Court in Railroad Commission

v. Pullman Co., 1941, 312 U. S. 496, 500-501:

“ The history of equity jurisdiction is the history

of regard for public consequence in employing the

extraordinary remedy of injunction. * * *. Few public

interests have a higher claim upon the discretion of

a federal chancellor than the avoidance of needless

friction with state policies. * * *.These cases reflect

a doctrine of ab- [R-121] stention appropriate to our

federal system whereby the federal courts, ‘exercising

4Hecht Co. v. Bowles, irifra, p. 330.

5Consider, e.g., Aircraft etc. Corp. v. Hirsch, 1947, 331 U. S. 752, 767;

Myers v. Bethlehem Ship Building Corp., 1938, 303 U. S. 41, 50-51, and

United States v. Western Pacific R. R. Co., Dec., 1956, .....U. S ........, 25

L. W. 4028, 4029.

eCook v. Davis, 5 Cir., 1949, 178 P. 2d 595, cert. den. 340 U. S. 811;

Bates v. Batte, 1951, 187 F. 2d 142; Peay v. Cox, 5 Cir., 1951, 190 F. 2d

123, cert. den. 342 U. S. 896.

This phase of the question is discussed more fully infra, part V (c)

and (d).

31

a wise discretion’ restrain their authority because of

‘scrupulous regard for the rightful independence of

the state governments’ and for the smooth working

of the federal judiciary.” [Emphasis added.]

II.

It is important, also, to refresh our minds as to the duty

here imposed upon United States District Courts and the

character and ingredients of their discretion.

(a) There can be no doubt that the Supreme Court

recognized that the responsibility for legal action in these

cases should be vested in the judges of the District Courts

who had intimate knowledge of local conditions. “ * * * be

cause of the great variety of local conditions, the for

mulation of degrees in these cases presents problems of

considerable complexity.” 7 In the second Brown opinion the

Court said: “ Because of their proximity to local conditions

and the possible need for further hearings, the Courts

which originally heard these cases can best perform this

judicial appraisal * * [Emphasis supplied.] And in the

series of Segregation Cases pending at the time of the

second Brown decision8 orders were entered sending the

cases back to District Courts for consideration in the light

of “ conditions that now prevail.”

(b) In acknowledging the fact of District Court dis

cretion and spelling out the factors which govern that

[R-122] discretion, under our constitutional system, the

Supreme Court stressed not only the local character of the

7First Brown opinion, p. 495.

sCf. Board of Supervisors v. Trueaud and allied cases, 347 U. S. 971.

32

problem, but the inherently public nature of it. In the first

Brown decision (p. 347), it noted that, at the time the

Fourteenth Amendment was adopted, “ In the South, the

movement toward free common schools, supported by gen

eral taxation, had not yet taken hold. * * * Education of

Negroes was almost non-existent, and practically all of the

race were illiterate.” It then proceeded to discuss some of

the cases in which efforts had been made to eliminate the

disparity existing between schools in the South and those in

the North. Fundamental differences were frankly recog

nized while adverting, at the same time, to the fact that the

South had not been alone in practicing the discrimination

at which the current decisions were aimed. The important

sentences9 in which it pointed out some of the distinguish

ing characteristics of the discretion admittedly residing in

District Courts read thus:

“ In fashioning and effectuating the decrees, the Courts

will be guided by equitable principles. Traditionally, equity

has been characterized by a practical flexibility in shaping

its remedies and by a facility for adjusting and reconcil

ing public and private needs.'” The most important aspect

of the principle enunciated in this quotation, and the one

which my colleagues seem to leave out of consideration, is

the case10 cited as authority for it and as setting up the

standard by which District Courts should be governed in

making this adjustment and reconciliation between “public

and private needs.”

9Second Brown decision, 349 U. S. 300.

10Hecht Co. v. Bowles, 1944, 321 U. S. 321, 329-330.

33

[R-123] (c) Since Hecht is the decision cited by the

Supreme Court as illustrating the principles by which Dis

trict Courts are governed in the exercise of discretion, it

ought to be examined in some detail. It began as an injunc

tion proceeding under the Emergency Price Control Act.

Government operatives had spot-checked seven out of more

than one hundred departments in the large store of the

Hecht Company, and had found in excess of 4,500 violations

of price regulations.11 Nevertheless, the District Court12

thought that Hecht has manifested good faith and was not

likely to commit, in the future, anything more than inad-

verted violations, and it felt that the public interests

would be served better by refusing an injunction than by

granting one: “ If in such circumstances an injunction is

asked the Court is not deprived of its inherent powers, by

calling it a statutory injunction. The Court in such case

retains its implied powers, exercised in a sound discretion.

* * * As generally understood judicial discretion includes

the propriety of granting appropriate relief. All rules in

equity must necessarily be sufficiently elastic to do justice

in the case under consideration. Courts of equity are not

inquisitorial but remedial.

“ * * * each case must be determined upon its facts and

on equitable principles. In a case such as this an injunction

should not issue unless thereby better compliance with law

may be enforced. Such consideration is addressed to the

sound discretion of the Court. * * * It is elementary that

11 See 137 F 2d 689.

1249 F. Supp. 528, 532.

34

the purpose of an injunction is to deter rather than to

punish. * * * The attitude of the defendant company is

not antagonistic but cooperative, and in my judgment an

injunction would not be in the public interest. * * * I con-

[R-124] elude that a just result requires a dismissal of

plaintiff’s complaint * * [Emphasis supplied.] The

Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia13 felt that

the District Court had misconceived the purposes of the

statute and had given too wide a sweep to traditional equity

powers, and it set aside the order of the District Court

which had refused the injunction. The Supreme Court

granted certiorari14 and reversed,15 approving the action of

the District Court in basing its denial of injunction on the

balancing of public interest versus private needs. Here is

its language:

“We are dealing here with the requirements of

equity practice with a background of several hun

dred years of history. * * *. The historic injunctive

process was designed to deter, not to punish. The

essence of equity jurisdiction has been the power of

the chancellor to do equity and to mold each decree

to the necessities of the particular case. Flexibility

rather than rigidity has distinguished it. The qualities

of mercy and practicality have made equity the instru

ment for nice adjustment and reconciliation between

the public interest and private needs as well as be

tween competing private claims. (P. 329.)

13Brown v. Hecht Co., 1943, 137 F. 2d 689.

“ 320 U. S. 727.

“ Hecht Co. v. Bowles, 1944, 321 U. S. 321.

35

“ * * * We repeat what we stated in United States

y. Morgan,16 supra, respecting judicial review of ad

ministrative action:

“ ‘* * * court and agency are not to be regarded

as wholly independent and unrelated instrumentalities

of justice, each acting in the perform- [R-125] ance of

its prescribed statutory duty without regard to the

appropriate function of the other in securing the

plainly indicated objects of the statute. Court and

agency are the means adopted to attain the prescribed

end, and so far as their duties are defined by the

words of the statute, those words should be construed

so as to attain that end through coordinated action.

Neither body should repeat in this day the mistakes

made by the courts of law when equity was struggling

for recognition as an ameliorating system of justice;

neither can rightly he regarded by the other as an alien

intruder, to be tolerated if must be, but never to be

encouraged or aided by the other in the attainment of

the common aim.’ The administrator does not carry

the sole burden of the war against inflation. The courts

also have been entrusted with a share of that responsi

bility. * * * For the standards of the public interests,

not the requirements of private litigation, measure

the propriety and need for injunctive relief in these

cases” [pp. 330-331; emphasis added.]17

(d) Here, then, is the blueprint suggested by the Supreme

Court for the guidance of District Courts in passing upon

applications for injunctive relief and in deciding whether

the best interest of the public and the private litigant will

«307 U. S. 183, 191.

if The same idea was expressed in Virginia Ey. Co. v. System Federa

tion etc., 1937, 300 U. S. 515, 552: “ More is involved that the settlement

of a private controversy without appreciable consequences to the public.

The peaceable settlement of labor controversies, * * * is a matter of

public concern. * * * Courts of equity may, and frequently do, go much

farther both to give and withhold relief in furtherance of the public

interest than they are accustomed to go when only private interests are

involved. [Emphasis added.]

36

be served by prolongation of litigation. There can be no

doubt that the Supreme Court rec- [R-126] ognized the

paramount public nature of this problem and the duty of

the District Courts to decide questions of policy as well as

questions of law.

Ordinarily discretion is lodged in a trial judge because he

is present and obtains the “ feel” of the trial. This includes

the attitudes of the parties and their counsel as revealed in

the give and take of the courtroom encounter, the advan

tage of observing the witnesses as they testify and of

appraising from their looks and demeanor the weight and

probative value of the words they speak.

But the discretion committed to the trial judge in segre

gation cases has the added ingredient arising from his

proximity to and knowledge of local conditions. His judg

ment is based upon what he knows from his experience as

well as what he hears from the witness stand. The broad

and comprehensive terms used in the discussed cases are

bound to embrace the manifold intangibles and imponder

ables which necessarily play such an important part in

assessing what is the public good and in balancing public

interest against private needs.

III.

(a) This Court has always aligned itself with the uni

versal rule that findings of the trial court must stand

unless clearly erroneous, and that exercised discretion

should not be disturbed unless plainly illegal or unsupport

87

ed by the evidence.18 This same disposition to lean [R-127]

heavily upon the district court was manifested in the first

decision of this Court applying the Segregation Cases:

“ A large measure of discretion, coupled with recognition of

judicial knowledge, must be vested in the district judge.” 19

But in more recent cases, this Court has apparently been

unwilling to accept the findings and approve the discretion

of the district courts in such cases.20

(b) This apparent change of attitude reflects, in my

opinion, a definite departure from the established rules of

law recognized as controlling by the Supreme Court in the

Segregation Cases as amplified by its decision in the Hecht

case. I think it is a mistake for us to attempt to sit in too

close chaperonage upon what the district judges do. Unless

we are to be given some peculiar powers of divination, we

cannot possibly approach the insight which is theirs by

reason of their intimate contact with the conditions con

fronting them.21

18E.g\ Mutual Life v. Ellison, 1955, 223 F. 2d 686; Indiana Mutual

Ins. Co. v. Jones, 1956, 230 F. 2d 500; United States v. Stewart, 1953,

201 F. 2d 135; Bruce v. McClure, 1955, 220 F. 2d 330; and United States

v. Smith, 1955, 220 F. 2d 548. And see United States v. W. T. Grant Co.,

1953, 345 U. S. 629, 633, where the Supreme Court said a chancellor’s

“ discretion is necessarily broad and a strong showing of abuse must be

made to reverse it.”

19Concurring opinion of Judge Rives in Board of Superintendents v.

Trueaud, 5 Cir., 1955, 225 F. 2d 434, 446-447, adopted by the Court en

banc in the same case, 1956, 228 F. 2d 895, 896.

20E.g. Whitmore, et al. v. Stilwell, et al. (Texarkana), 1955, 227 F. 2d

187; Brown, et al. v. Rippy, et al. (Dallas), 1956, 233 F. 2d 796; and

Jackson, et al. v. Rawdon, et al. (Mansfield), 1956, 235 F. 2d 93.

®For example, the action of the District Judge in the Mansfield

School case was based, in my opinion, on a clear comprehension of the

many-sided problem with which he was dealing and he exercised wisdom

and discretion in fashioning the decree to accomplish what was best for

the public as well as the litigants. Three Negro boys had applied for ad-

(Footnote Continued on Next Page)

38

[R-128] (c) The Court below in this case, alive to local

conditions, acquainted with local needs and with the human

beings bearing primary responsibility with respect to them;

and observing the demeanor, as witnesses, of the public

servants entrusted with the operation of a public school

system for the good of all of the people, felt that more

would be accomplished if the cudgels of conflict should be

dropped, and men of good will should be encouraged to

discuss and compose their differences in an atmosphere

(Footnote Continued from Preceding Page)

mission to the Mansfield High School a month after classes had been

begun. The District Judge, acting in obedience to the teachings of the

Supreme Court in the Hecht case, denied the injunction because he felt

that more good could be acomplished by so doing than by granting in

junction. Here, in part, are the reasons assigned by him for denying the

injunction:

“ In finding the equities between the parties I see on the one hand,

the situation of this rural school board composed primarily of farmers,

agents of the State of Texas * * * opening their meeting with prayer

for solution; studying articles in magazines and papers; holding numer

ous meetings, passing resolutions and appointing a committee to work

on a plan for integration—making the start towards obeying the law

which their abilities dictate. Further, the trustees now assure the Court

that they are continuing their efforts and will work out desegregation.

Their committee conferred with these plaintiffs in the presence of plain

tiff ’s parents, and accepted and fulfilled the requests made by plaintiffs

with their attorney in August, 1955 for certain administrative steps as

a solution for this period of transition, * * *. After the accomplishment

of these administrative steps taken at the request of plaintiffs and after

school had been in session more than a month, this action was filed.

“ After the accomplishment of the above mentioned administrative

processes at plaintiffs’ request, and after school had begun, it appears

to the Court that the issuance of an injunction to effect entrance into

Mansfield High School at this time would be unjust to the school trustees

and the students alike. * * *,

“ It is impossible, however, simply to shut your eyes to the instant need

for care and justice in effectuating integration. The directions of the

United States Supreme Court allowed time for achieving this end. While

this does not mean that a long or unreasonable time shall expire before

a plan is developed and put into use, it does not necessitate the heedless

and hasty use of injunction which once issued must be enforced by the

officers of this Court regardless of consequences to the students, the

school authorities and the public. This school board has shown that it

is making a good faith effort towards integration, and should have a

reasonable length of time to solve its problems and . end segregation in

the Mansfield Independent School District.” [Emphasis added.]

39

permeated as little as might be by animosities. He [R-129]

concluded apparently that an ounce of cultivated mag

nanimity and forebearance might be worth more than a

pound of coercion.

IV.

Projected against this background of legal principles,

this case seems to me quite simple and easy of solution. I

think the Court below handled it well, decided it correctly,

and that we should uphold its wise action in all respects.

(a) A group of Negro children desired to enter Barwise

School and, at the beginning of the school year, presumably

went there to matriculate. They were told that they would

be permitted to enter this school as soon as the pupils then

attending it could be moved to Sunnyside Heights School,

then in course of construction. It was estimated that this

shift could take place in about six weeks.22 Announcement

of the completion was made on Christmas Day and all of

plaintiffs were admitted to the Barwise School (its name

having been changed to Holland) upon convening of the

second term in January.

(b) Meantime, about two weeks before the announce

ment was made, this civil action was begun. It was pre

dicated solely upon the fact alleged in the complaint that

Barwise was the school nearest plaintiffs’ homes. Alfred

Avery, the only plaintiff concerning whom proof was made,

22Shortage of steel resulting from the steel strike, together with heavy-

rains and two floods, brought about a delay in the completion of the new

school.

40

lived about six blocks from the school. Plain- [R-130] tiffs

and their attorney knew when the action was begun that

all of the relief sought would be given administratively

without litigation long before the case could possibly be

brought on for hearing.

This action was begun solely because plaintiffs’ attorney

did not trust the school board, and did not think it was pro

ceeding in good faith. Appellants’ brief and oral argument

abundantly demonstrate this, and the frequent colloquies

between their attorney and the Court bring it into bold

relief.23

Barwise was a small school with ten classrooms and a

capacity of less than three hundred pupils. There were one

hundred forty Negroes whose residences would entitle them

to claim admittance to Barwise. All of them could not be

accommodated and the school board could not practice dis

crimination in favor of plaintiffs and against the residue,

or against the pupils already enrolled therein.

(c) The Trial Judge considered the affidavits and had

the benefit of the testimony of one of plaintiffs’ parents

and of members of the school board. He found that it was

not unreasonable to defer the applications of plaintiffs for

a few weeks until the physical plants of the school could

be altered to meet the new demands; and felt, too, that the

school board had wrestled with its vexing problems in a

23At one point the Court said to plaintiffs’ attorney: “ You have mis

givings, I am sure, from what has been said * * * *[but] personally I have

strong faith in the good intentions and good faith of the school board.

* % ❖ »

41

spirit of fairness and good faith and that an injunction or

the continued pendency of the suit [R-131] would serve no

good purpose, but would do harm. The following quotation

from the Judge’s opinion sets forth what was behind his

judgment:

“ The Supreme Court * * * has recognized very

clearly the practical reality that the primary responsi

bility in this progress of desegregation rests on the

local school boards, those nearest to its problems in its

local aspects, and that’s where it should be properly,

so long as local officials demonstrate the attitude to

solve the transition * * * with reasonable dispatch.

It is of supreme importance that the work should pro

ceed peaceably in this undertaking * * *.

“ But the impression I have from what has been

presented during the hearing today is that the Board

and officials of this School District seem to be men of

good will and have set their policy toward the inte

gration of this new educational policy and with that

attitude in mind I think it would be premature for

courts to interfere. Impatience and precipitancy of

spirit are not, I am convinced, nearly so reliable a

course as that of depending upon these authorities,

once you have substantial evidence that they are acting

in good faith and with a real and honest purpose to go

ahead and without dragging the plans by any unneces

sary or vexatious breaks along the way.

“ I have the faith in this School Board that they

will measure up to the responsibilities and the plans

that have been declared in their behalf here today

through their Superintendent and Secretary of the

Board and the recorded minutes and by the words of

their counsel. * * * I believe it would be a disservice

to step in at this time and [R-132] undertake to com

pel and direct the business of these men under the

power of the Court.”

42

The judge who spoke these words had seen the witnesses

as they testified, had acquired the “ feel” of the case as it

unfolded before him; and he demonstrated in his grasp of

the problem a wisdom, a patience and a tolerance which

invest his words with commanding convictive force. More

than that, he was born and had spent his days in close

proximity to the locale of this controversy and had an inti

mate acquaintance with the conditions with which he was

dealing. We, who assume to pass upon the wisdom of his

discretion, have lived our lives hundreds of miles away

from that locale. The trial judge, following the holdings of

Brown and Hecht, felt that more would be accomplished by

denying the injunction and removing the case as a constant

irritant than by granting the injunction or retaining the

case. When we substitute our judgment for his, a lack of

perspective is demonstrated along with a definite disson

ance with the teachings of the Supreme Court.

y .

It remains, therefore, but to examine the majority opin

ion to test the reasons upon which the reversal is predicated.

(a) While conceding that the Court below did not err

in refusing declaratory and injunctive relief, the opinion

intimates that the school board was guilty of some illegal

action.24 In fact, what is said concerning mootness [R-133]

is predicted necessarily on the assumption of illegal action

and on doubt concerning the good faith of the school

24Such phrases occur in the opinion as “voluntary cessation of illegal

conduct,” and “ no reasonable probability of a return to the illegal con

duct.”

43

authorities. The opinion does not point to any facts which

would furnish the basis for a charge of illegal conduct.

Every plaintiff who applied for admission to the Barwise

School had gained that admission by administrative action

before the trial and there never had been any doubt about

the purpose of the school board to comply with the re

quested admission as soon as physical properties could be

changed to meet the new conditions. The timing and other

details of the transfers were matters committed to admin

istrative action and the Court was without jurisdiction to

intervene in any event unless and until bad faith was

shown. United States v. Western Pac. R. Co., supra.

(b) The opinion takes note of the suspicions voiced by

plaintiffs’ counsel that the school board did not intend to

do in the future what they solemnly swore they were going