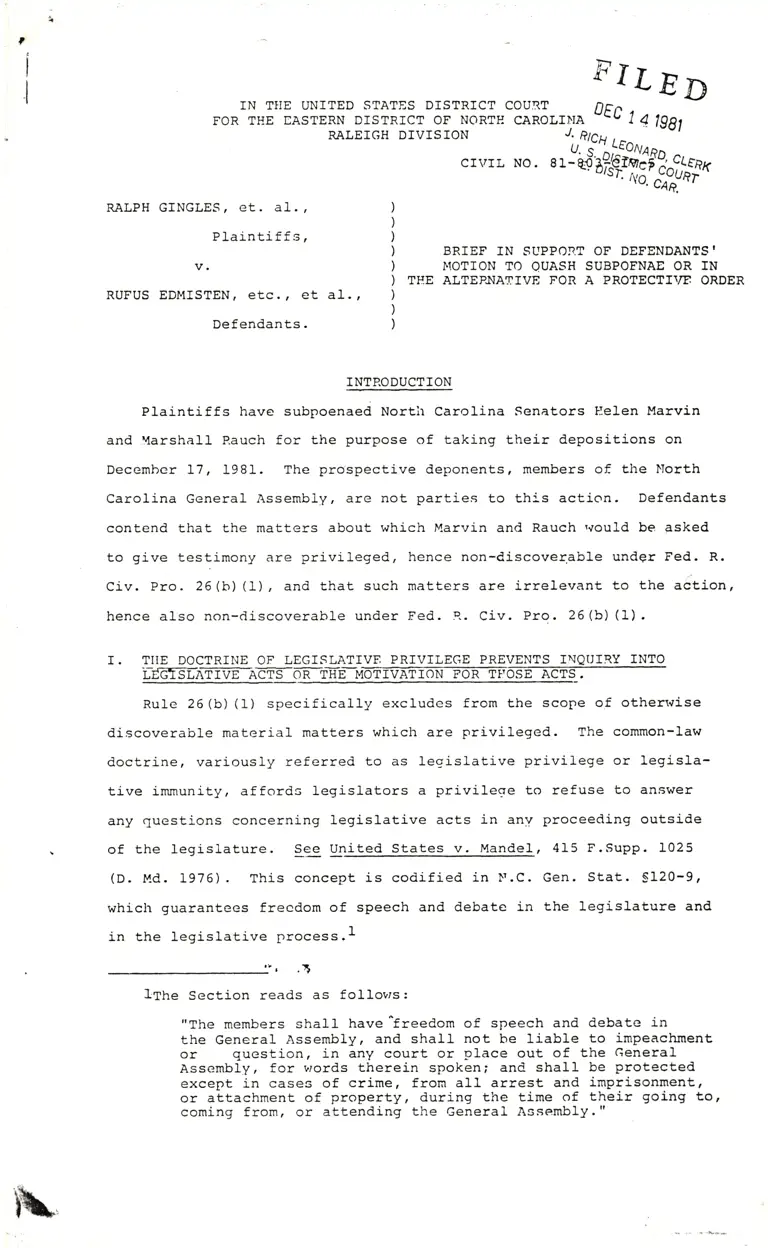

Brief in Support of Defendants' Motion to Quash Subpoenae or in the Alternative for a Protective Order; Motion to Quash Subpoenae or in the Alternative for a Protective Order; Notice of Postponement of Deposition; Plaintiffs' Response to Defendants' Motion to Quash Subpoenae or in the Alternative for a Protective Order; Memorandum from Williams to Gingles Counsel; Orders

Correspondence

December 14, 1981 - January 5, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Williams. Brief in Support of Defendants' Motion to Quash Subpoenae or in the Alternative for a Protective Order; Motion to Quash Subpoenae or in the Alternative for a Protective Order; Notice of Postponement of Deposition; Plaintiffs' Response to Defendants' Motion to Quash Subpoenae or in the Alternative for a Protective Order; Memorandum from Williams to Gingles Counsel; Orders, 1981. adb1dd56-da92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/159452df-b540-4e5d-a319-a75d4911f656/brief-in-support-of-defendants-motion-to-quash-subpoenae-or-in-the-alternative-for-a-protective-order-motion-to-quash-subpoenae-or-in-the-alternative-for-a-protective-order-notice-of-postponement-of-deposition-plaintiffs-response-to-defenda. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

t

i

I

F'Tt ED

IN TIIE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COUIIT f)cn

FoR THE trASTERN DrsrRrcr oF NoRTH cARoLrr.IA -t-t' I 4lggt

RALEIGH DIVISION

"

c r \zr L No ., r -*rftiffia+r-

RALPH GINGLES, €t. a1.,

Plainti ffs ,

v.

RUFUS EDMISTEN, etc., et al.,

BRIEF IN SUPPOP.T OF DEFENDANT.S I

r{oTroN To quAsH SUBPoFNAE oR rN

TI{E ALTEPNATIVE FOR A PROTECTT\TE ORDER

Defendants.

INTP.ODUCTION

Plaintiffs have subpoenaed Nortir Carolina Senators Flelen Marvin

and l,Iarshal1 Pauch for the purpose of taking their d.epositions on

December L7, 1981. The prospecti-ve deponents, members of. the I'Iorth

Carolina General Assembly, are not parties to thls acticrn. Defendants

contend that the matters about which Marvin and Rauch 'vould be asked

to give testimony are privileged, hence non-discover.able under Fed. R.

Civ. Pro. 25(b) (1), and that such matters are irrelevant to the action,

hence also non-discoverable under Fed. F.. Civ. Pro. 25 (b) (1) .

I. TIIE DOCTRINE OP LEGISLATIVE PRTVTLEGE PREVENTS INQIJIRY INTO

L-ffiCfr=r-HE-MbT

RuIe 25 (b) (1) specifically excludes from the scope of otherrvise

discoverable material matters which are privileged. The common-law

doctrine, variously referred to as legislative privilege or legisla-

tj-ve S.mmunity, affords legislators a privilege to refuse to answer

any questions concerning legislative acts in anv proceecling outside

of the legi-slature. q- , ALS F.Supp. 1025

(o. Md. f 976) . This concept is codified in I'.C. Gen. Stat,. 5120-9,

which guarantees freedom of speech and debate in the legislature and

in the legislative proc"=".1

I' .T

lrhe Section reads as follovrs:

"The members shaI1 have treedom of speech and debate in

the General Assembly, and shall not be liable to impeachment

or question, in any court or place out of the General

Assembly, for vrords therej-n spoken; and shal1 be prot'ected

except in cases of crime, frorn all arrest and imprisonment,

or attachment of property, during the time of t.heir going to,

coming from, ot attending the General Assembly. "

/

/

t:

, /

North carolina's statutory provision parallers the speech or

Debate Clause of the Federal Constitut,ion (art. I, 56), as well

as the statutory and constitutional enactments of most other

states. In interpretine the federal constitutional version of

thj-s doctrine the united statesupreme court has written:

The reason for the privilege is cIear. It r.raswell summarj-zed by James Wilson an influential

member of the Committee of Detail which r.ras

responsible for the provision in the Federal

Constitution. "In order to enable and encourage

a representative of the public to discharge hispublic trust vith fj.rmness and success, it is

indispensably necessary, that, he should enjoy

the fullest liberty of speechr drd tl.at he

should be protected from the resentment of every

one, however porverful, to rrhom the exercise of that

liberty may occasion offence. " Tenney v. p,roadhove,

341 u.s. 367 (1951) at 372-7 3 (citaffiomiEEffi-) .

Legislative privilege has a substantive as weLl as evidentiary

aspect, and both are founded in the rat,ionare of legisrative

integrity and independence, enunciated by ttre Framers and propounded

two centuries later by the Supreire Court. The substantive aspec,t

of the doctrine affords legislators immunity from civil anrl criminal

Iiability arising from legislative proceeclinqs. The eviclentiary

aspect. affords legislators a privilege to refuse to testify about

legislative acts in proceedings outside the legislatj-ve halls. United

State v. llandel , supra at L027.

At. issue here.i-s the evidentiary facet of the privilege and,

specifically, whether such a state-afforded evidentiary privilege

should have efficacy in the federal courts. It is clear that the

S;:eech or Debate Clause of the federal constitutj-on vrould preclud.e

the deposition of a member of Congress in an analogous situation.

In Brewster v. United States, 408 U.S. 5Og (1975), the Court stated,

beyond doubt that the Speech or Debate clause protects agaj.nst

the legislative

U.S. at 525.

"rt is

inquiry

Process

into acts that occur i.n

". ,)t

and into the motivation

the regular course of

for those acts." 408

L

-3-

Defendants acknowledge that even the privilege granted federal

legislators is hrounded by countervailj.nq considerationsr particularly

thc need for every man's evidence in federal criminal prosecution.

As Brewster further states, "the privilege is hroad enouqh to insure

the historic independence of the Legislativc Branch . but narrow

enough to guard against the excesses of those who uou16 corrupt the

Process by corrupting j-ts memhers." 4OB U.S. at S2S. Defendants

moti-on attempts, however, to conceal no ,'corruption,,.

I,rith the boundaries of the fe<ieraI legislative privilege in

mj'ndr w€ turn to the question of the scope of parallel state privileges.

Whatever their extent and range of applicability in state court, the

United States Suprerne Court has ruled that state privileges vri1l r Et

tj-mes, yeild to overriding federal interests in federal courts.

q , 100 S.Cr. 1185 (1980). The Court has

recognized only one federal interest of importance sufficj.ent to

merit dispensing with this state-granted privilege: the prosecution

of federal crimes.

The Supreme Court has never sg:arely adcl.ressed ilre issue presented

here: ,whether a state legislator's evidentiary privilege remains

intact in federar civir proceedings. rn Tenney v. Broadhove, supra,

the court ruled that a regislator,s aqbs.lanli-ve irnmunity from suit

withstood the enactment of 42 U.S.C. 51983, ErDd thus state legislators

were not susceptible to.suit for r.rords and acts vrlthin the purvievr

of the legislati-ve process. Although it deals r+ith the substantj.ve

aspect of the privilege, Tenney is instructive, insofar as the Court

there gave great deference to the state's own doctrine. Recently,

in United states v. !.i1rocE, supra, a criminal case invorving the

evidentiary facct of legislative J-mmunity, the Corrrt cited Tenney

for the propositigp thEt a1r federal courts must endeavor to apply

state legislative privilege. fn Gi1Igck, however, the Court ruled

\

-4-

that the Tennessee speech or Debate crause would not exclude

inquiry into the legislative act,s of the defendant-legislator

prosecuted for a federal criminal offense.

Throughout the supreme court's activj-ty in this field no

distj-nction has been drawn betvreen substantive and evidentiary

applications of the privilege for the purpose of determining the

efficacy of legislative privileqe in federal court. Thus, the

Courtrs conclusions in Gillock and Tenney must be read together,

and their comhined effect dictates that the evidentiary privilege

granted a legi.slator by his state remains inviolable except $rhere

it must yield to the enforcement of federal criminal statutes.

See Gi.llocl: at 1193.

Unless federal criminal prosecution demands othenrise, ,,the

rore of the state legislature is entitled to as much judicial

respect as that of Congress The need for a Congress vrhich may

act free of interference by the courts is neither more nor less than

the need for an unimpaired state legislature." Star Distributors, Ltd.

v. Marino, 613 F.2d 4 (1980) at g. On this fundamental point the

Supreme Court has recently said, "To create a System in which the

a

Bill of Rights monitors more closely the conduct of state officials

than it does that of federal officials is to stand the constit,utional

design on its head." Butz v. Economou, 428 (r.s. 479 (1979) at 504.

In the present civil action, brought by private citizens of

Ilorth Carolina, Legislators l(arvin and Rauch arb privileged to refuse

to testify concernins their legislative acts. Principles of comity

and the decided law strongly suggest tha! federal courts honor this

evidentiary privilege in aIl civil actions.

IT. THE I.{ATERIAI SOUGHT TO BE DISCOVERED IS IRRELFVA}IT.

The North Cagolina House, Senate, and

plans challenged in this litigation speak

Congressional reapportionmenr

for themselves. Insofar as

I

I

f,.,

-5-

the intent of the legislature is in question, the legislative histoty,

i'e" the contemporaneous record of dehate anc enactment, reveals the

legislative intent. The remarks of any single legislator, even the

sponsor of the bi11, are not controlling in analyzing legislative

history. , 44L u.s. 2B1 (1929). That

such remarks have any relevance at all precludes that they were made

contemporaneousry and constitute part of the record. see united

state v. Gila River pima-llarlcop. rrdi.., com*unity, 5gG p.2d 2og

(ct. c1- 1978). This proposition i-s adhere<I to even more strongly

by the appellatc courts of North carolina. The North carolina supreme

Court, for example, stated the following in D & I.L fnc. v. Charlotte,

268 N.C. 577, 581, 151 s.E.2d 24t, 244 (1955):

". l.,lore than a hundred years ago this Courtheld that 'no evidence as to the motivei of theLogislature can be heard. to give operation tor orto take it from, thej.r acts. . Drake v.'orike,15 N.C. 110, 117. The meaning of a =Eaffi'intention of the legislature u]'r.icrr pasiea it cannotbe shown by the. testimony of a memhlr of the legisla-ture; it 'must be drarrrn irom the constiuction oi ah;Act j.tself.' goins v. fndian Training School , 169N.C. 736, Z:g,

The testimony of Marvin and Rauch is not

of the $eneral Assembly and can have no other

Thus, their depositions are outside the scope

discovery.

rII. PRESERVATTON OF LEGTSLATIVE- INDEPENNENCE REQqIRES TFIAT, SHOI,ILD

rf the court or<lers the depositions to proceed, it is imperative

that thc transcripts he sealed and opened only upon court order. The

purpose of legisrative privilege is to ,'avoid. intrusion by the

Executive or the Judiciary into the affairs of a co-equar hranch,

and . to protect regislative in<lependence.', Gillock at 1191.

relevant to the intent

discernable relevance.

of permissible

.T

-5-

Legislators must feel free to discuss and, ponder the plethora

of economic, social, and political considerations which enter into

legislative decision-making. Fear of subsequent disclosure of an

individual legislator's intent or rationale rvould chill debate and

destroy independence of thought ancl vote. In this case, sensitive

political considerations might be recklessly exposeci by the Plaintiff's

proposed discovery. To maintain free expression of j.deas vrithin the

General Assembly, as well as to protect those ideas already freely

cxpressed therein, a protective order must issue, if the subpoenae

are not quashedr €ls they should I:e.

Respecrfully submitted, this En" ( day of December, 1981.

Raleigh, I.lorth Carolj.na 27602

Telephone: (919) 733-3377

Norma Harrell

Tiare SmilerT

Assistant A.ttorneys General

John Lassiter

Associate Attorney General

Attorneys for Defendants

Of Counsel:

Jerris Leonard &

900 17th Street,

Suite 1020

Washington, D. C.

(202) 872-L095

Associates, P.C.

N.l^I.

20005

.)}

P.UFUS L.

ATTORNEY

EDI'TSTEN

arJ.aee, ;Ir.

Attorney Gen

Legal Affairs

rney General's Office

. C. Department of Justice

Post Office Box 629

-

if,l

t' rN THE UNITED STATES DTSTRICT COURT

RALPH GINGLES, et d1., )

)

Plaintj-ff s, )

v.

RUFUS EDUfSTEN, etc., et a1.,

FoR rHE EASTERN

3l:I=;$_3lniln*rr

cAnolrro

trq I L E D

crvrl No . 81-8 03-@81 4 Bgl

.,,:,:ti?#df

,i,.,,,".I*

) MOTION TO QUASH SUBPOENAE

OR IN THII

ALTER].IATIVE FOR A PROTECTI\IE ORDER

Defendants. )

Now cotrtE the Defendants, by and through their counsel of record,

and move this Honorable Court for an order guashing the sub5roenae

and notices to take the deposj-tions of North Carolj-na senators Helen

l'larvj-n and Marshall Rauchr or, in the alternative to enter a protective

--- order pursuant to Fed. P.. Civ. Pro. 26(c) (5) and (5), directj-ng that

the depositions be conducted trith no one prcsent except persons des-

ignated kry the court and that the depositions k,e sealed and subsequently

opened only by Court Order.

The Defendants state the follorving grounds in support of their

l,lotion:

1. The legislative acts and words of the prospective deponents

are privileged and thus outside the scope of discovery permitted

by Fed. R. Civ. pro. 26(b) (1). Senators Helen Marvin and tlarshaIl

Rauch are members of the }Iorth Carolina General Assembly. The Speech

or Debate provision of tke North Carolina General Statutes affords

leqislators a privilege to ietuse to ansvrer anv cuestion concerning

legislative acts in any proceeding outside of the legislature.

2- The legislative history speaks for. itself, and inquiry into

the intent of individual legislators is irrelevant and beyond the

scope of discovery as described in F.ed. R. civ. pro. 26(b) (1).

-2- a-

WHEREFORE, by reason of the foregoing, and as more ful1y set

forth in the attached brief in support of this motion, Defendants

pray this Honorable Court for an order guashing th.e above-

described subpoenae, ot t in the alternative, directing that

depositions be yaJ-ed.

A'

Ttris Ehe /(t day of December, 1981.

RT,FUS L. EDI!,ITSTEN

ATTORNEY GENERAL

Ra1eigh, North Carolina 27602

Telephone: (919) 733-3377

Norma Harrell

Tiare Smiley

Assistant Attofneys General

John Lassiter

Associate Attorney General

Attorneys for Defendants

Of Counsel:

Jerris Leonard &

900 17th Street,

Suite 1020

Washington, D. C.

202/872-to9s

Associates, P.C.

N.W.

20 006

y Attorney Ge36ra1

r Leqal Affairs

orney General's Office

. C. Department of Justice

Post Offi.ce Box 629

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I certify that I have served the foregoing document on all

other parties by placing a coPy thereof enclosed ln a Postage

prepaid properly addressed wrapper in a Post office or official

depository under the exclusive care of the U.S Postal Service to:

Senator Marshall Rauch Senator llelen Marvin

LL?L Scotch Drive 119 Ridge Lane

Gastonia, NC 28052 Gastonia, NC 28052

Mr. Jaues M. WaLlace, Jt. Mr. Jerris Leonard

N.C. Attorney General's Office 900 L7th St. NW

Post Office Box 529 Suite L020

Raleigh, NC 27602 Washington, DC 20006

Ttris 17th day of December, 1981.

q

-2-

IN TTIE

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE

EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

RALEIGH DIVISION

81. ,

Plaintiffs,

F XLED

oEC i 8 198t

J. RICH LEONARD, CLERK

U. S. DISTRICT COURT

E. DIST. i\io. CAP.

RAIPH GINGLES, et

NOTICE

OF

OF POSTPONEMENT

DEPOSITIONv.

RUFUS EDMISTEN, et 81.,

Defendants.

T0: Senator Marshall Rauch

Senator HeLen Marvin

James M. Wal1ace, Jr.

Plaintiff in the above captioned action hereby gives notice

that the depositions of Senators Marshall Rauch and Helen

Marvin, scheduled to be taken on December L7, 1981, are postponed

until such time as the Court shall rule on Defendants' Motion

to Q3:ash Srrbpoenae or in the Alternative For a Protective Order.

This 17th day of Deeember, 1981.

U7"^*

6n]ii#=I, r5lgrr"orr, Irlatt, I,Iq,llas,

Adkins & Fuller, P.A.

Suite 730 East Independence PLaza

951 South Independence BouLevard

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

704/ 37s-8461

Attorney for Plaintiff

Office Box 629

lgh, North Carolina

Office

27602

Attorney for Defendant

IN THE

I,NITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE

EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

MLEIGH DIVISION

NO. 81-803-CrV-5

RALPH GINGLES, et €rl. ,

Plaintiffs,

v.

RUFUS EDMISTEN, et al.,

Defendant s .

PI.A.INTITFS' RESPONSE TO

DEFENDANTS' MOTION TO QUASH

SUBPOENAE OR IN THE ALTERNA-

TIVE FOR A PROTECTI\IE ORDER

I. InEroduction

Plaintiffs, black citizens of North Carolina, bring Ehis

acEion to enforce Eheir right to voEe and Eo have equal repre-

sentaEion. They asserE claims under the FourEeenth and Fifteenth

Amendments to the United States Constitution and under SS2 and 5

of the Voting Rights Act of 1955, 4s amended, 42 U.S.C. SS1973

and 1973c ("The VoEing Rights Act"), challenging the apportionmenE

of che North Carolina General Asseurbly and the United SE,ates

Congressional districts in Norch Carolina. Plaintiffs allege thac

Ehe apporEionmencs vrere adopted with che prrrpo"" and, effect of

denying black ciEizens the right Eo use their votes effectively

and chac Ehe General Assembly apportionmenEs violate Ehe "one

person-one voEe" provisions of Ehe equal protecEion clause.

Discovery has corr-enced. 0n December 3, 1981, plaintiffs

noEiced the deposicions of and subpoenaed SenaEor Marshall Rauch,

che Chairoan of che North Carolina SenaEe's Conrruictee on Legis-

lacive RedistricEing and SenaEor Helen Marvin, Ehe Chairman of

che Norch Carolina SenaE,e's Comrittee on Congressional RedisErictring.

The subpoenae requesE EhaE Ehe senaEors bring Eo the deposiEions:

Documencs of any kind which you have in your possession

which relace Eo che adoption of SB 313 I87l during Ehe 1981

Session of Ehe Norch carolina Generar Assembly. This

requesE includes but is noE lioited Eo correspondence,

melooranda or oEher wriEings proposing or objecting Eo

any plan for apporEionnent of North carolina's senate

Icongressional] districts or any criteria therefore.

Defendants move to quash the subpoenae on the grounds that

neiEher Senator can give any relevant testinony and that all testi-

upny of both SenaEors is privileged. Plainriffs oppose this motion.

Defendants' mot,ion to quash is an objection to the entire deposi-

Eions. Plaintiffs have not asked particular questions. If plain-

Eiffs had caken the depositions, the inquiry would have included Ehe

following:

1. The naEure of the Senator.'s role as chairman of a

Redistrict ing CornmiEtee ;

2. The sequence of events which lead to the enactment of

the redistricring legislarlon i

3. Normal procedures for enacEing this t)rpe of legislation;

4. T'he criEeria adopted by che redistricting comnittees;

5. Factors norroally considered importanE in rediscricting;

6. The existence of any substanEive or procedural departures

from normal;

7, The existence of documents, official records, oE unoffi-

cial records which contain Ehe substance of cornrniEEee, subcorrrmittee

or whole Senace debaEe i

8. Their knowledge of the conEemporary statenenEs by mem-

bers of Ehe legislature of che reasons for adopcing or rejecting

proposed apporcionuent plans ;

9 - The exisEence of witnesses tro sEaEemenEs as described in

paragraph 8 above; and

I0. The exisEence of ocher wiEnesses who observed or erere

involved in rhe process EhaE led Eo the enacEment of the challenged

aPPOrEionoenEs.

Because che Senacors were che Chairmen of che rediscricting

cormiEtees which were responsible for reporEing co the full Senace

a recolDmended apporEionuenc for enaccnenE, plainciffs believe each

has knowledge relevant Eo these inquiries.

-2-

One of plainciffs' allegations is thau Ehese apporEionments

discriminaEe against them on Ehe basis of race in violation of

the equal protecEion clause of the Fourteenth Amendnent. rn

order to prevail on this claim, plaintiffs must show that the

plans $rere conceived or maintained wiEh a purpose Eo discriminate.

Cirv of Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980); Village of Arlingron

HeiehEs ". Metropol@ , 429 u.s. z5z (L977) t

Washington v. Davis , 426 U.S. 229 (1976).

In addition, iE is arguable that plaintiffs Etrst show purpose

to dilute black voEe in order Eo prevaiL in their claims under 52

of the voting Rights Act. see Mobile v. Bolden, -g}PE, washinsEon

v. Finlev, _ F.2d _, ( 4rh Cir. , #80 -L277 , November L7 , L981) .

The supreme court in Arlingcon Heights, supra, noted thaE,

"DeE,ermining wheEher invidious discriminatory purpose was a moti-

vating facEor demands a sensiEive iirquiry into such circr.msEantial

anddirecE evidence of intent as may be available." 429 U.S. at 266.

Among Ehe subjecEs of proper inquiry for proving intent lisred by

Che Supreme Court are:

1. The specific sequence of evenEs leading up Eo Ehe chal-

lenged dec.is ion ; r

2. Departu="i fro, normal procedural sequencei

3. Substancive deparEures from factors usually considered

irnportant; and

4. Contemporary stacenenEs by members of the decisionmaking

body, minuEes of its meecings, o! reports.,

-

Arlington Heighrs v. l.lecro Housing corp. , 429 u.s. aE 257-268. see

arso McMillan v. Escambia co., 638 F.2d L239 (5ch cir. 1981);

U.S. v. Cicv of Parma, 494 F.Supp. 1049, 1054 (N.D. 0h. 1980).

SenaEors Rauch and Marvin would be expected Eo give EesEimony

relevanc Eo each of chese inquiries. In addition, the Supreme Court

recognized, "In some exEraordinary inscances the oembers rnight be

called Eo che scand aE crial Eo EesEify concerning the purpose of

official accion, . . . . " Arlington Heighcs, -ggg..

-3-

In addition, defendants have raised as the Fourth Defense

in Eheir Answer EhaE, "The deviations in Ehe 1981 Apportionment

of Ehe General Assembry were unavoidable and are justified by

raEional state policies." This defense relates Eo plaintiffs'

"one Person-one vote" claim. If allowed Eo take Ehe deposition

of SenaEor Rauch, Chairman of the SenaEe Coumittee on Legisla-

Eive Redistricting, plaintiffs would inquire about the rational

staEe policies that caused the populaEion deviations in the

SenaEe plan and would inquire about the existence of other plans

Ehac met these policies buE had lower population deviaEions.

These deposiEions and these lines of inquiry are permiEted

under Rules 26 and 33 of che Federal Rules of Civil procedure and

under Ehe Federal Rules of Evidence,.

II. THE TESTIMONY OF SENATORS RAUCH

AND MARVIN IS NOT. PRIVILEGED.

Rule 501 of the Federal Rules of Evidence provides, in per-

EinenE part:

Except as otherwise required by the ConstituEion of Ehe

United SEates or provided by Act of Congress or in rules

prescribed by Ehe Supreme Court pursuant Eo statutory

auEhority, che privilege of a wiE,ness, person, governmenE,

Stace, oE political subdivision chereof shalI be governed

by che principles of Ehe corrmon law as chey may be inter-

preced by che courts of the United Sraces in the lighr of

reason and experience.

This rule applies Eo discovery as well as Eo Erial. F.R.Ev.,

RuIe 1l0l(c). Thus, in order Eo deteruine if Ehe Eestimony of Senators

Rauch and l,larvin is privileged r.riEhin Ehe meaning of RuIe 26(b) of

che Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, che Court Eust decermine if it

is covered by Rule 501 of the Rules of Evidence. See U.S. v. GiIIock,

445 U. S. 360 , 366 ( 1980 ) .

Defendancs asserE a legislacive privilege parallel Eo che Speech

and Debace Clause of Article I, 55 of che United Scaces Conscicucion.

However, Ehe Speech and Debace Clause applies only Eo members of che

-4-

United scates Congress, noE to staEe legislators. Nor does the

staEe statuEe establishing the privilege in staEe courEs establish

the privilege under Ehe Federal Rules. u.s. v. Gillock, 449 u.s.

at 368, 374. Defendants do noE cite any provision of the United

Staces Constitution, Act of Congress, oE Supreme Court rule which

establishes a privilege which exempEs state legislacors from Ees-

tifying. Ttrus Ehe Court must decermine if Ehe Eestimony is pri-

vileged "by Ehe principles of cormon law as they may be interpreted,

by Ehe courts of Ehe United States in light of reason and experience."

F.R.Ev., Rule 501.

Defendants cite no case in which legislative privilege is

extended Eo Ehe Eestimony of state legislaEors, and plaintiffs know

of none. U.S-r--:r.-_ltandel, 415 F.Supp. 1025 (D.Md. Lg76), which

defendants cite in support of Ehe evidentary privilege, is a case

in which a state governor asserted inrmunicy from criminal prosecu-

tioru and che Court held EhaE there was no immunity for governors

doing legislative acts. The language quoted by defendants is only

dicEa, largely irrerevanE Eo Ehe issue before thaE court.

In order Eo deEermine whether a privilege parallet ro the Speech

and Debate Clause should be created for stace legislacors, it is

helpful Eo analyze Ehe purposes of che Speech and Debare Clause.

rEs hisEory is seE ouE in Kilbourn v. Thompson, 103 u.s. 168, 26

L.Ed. 377 (1881). The clause was paEEerned after an English parlia-

menEary provision which was designed to sEop che crovrn fromimprisoning

llembers of ParliamenE for seditious libel. 26 L.Ed ar 390-391. As

Eran5laced into the American republican form of governmenc, the

clause has Ewo purposes:

t. To protecE che members of Ehe co-equal legislacive

branch of Ehe federal goverunenE from prosecution

by a possibly hosEile execuEive before a possibly

hoscile judiciary, Kilbourn v. Thonpson, EIEE; and

To preserve Ehe independence of che legislacure by

freeing the members from che burden of defending

cheoselves in court and of ulrimace liability.

Donqbrowski v._Lqsgland, 387 U.S. 82 (1957).

2.

-5-

Neither of these reason is applicable to the moEion before

the Court.

Since a scaEe legislature is noE one of Ehe three co-equal

branches of the federal goverrulent, the first reason does not

apply. The Supreme Court reached this conclusion in U.S. v. Gillock,

.supre,, in holding EhaE a state legislator is not immune from

federal prosecution for crimes cormitted in his legislative capacity

and that he had no privilege against the admission into evidence of

his legislative acts. Both would have been precluded if a privilege

similar in scope to Ehe Speech and Debate Clause applied. In

reaching che conclusion the Couru said:

The first raEionale, resting solely on the separation-of-

povrers docUrine, gives no supportr to the granE of a privi-

lege Eo state legislaEors in federal criminal prosecutions.

IE requires no citation of authorities for Ehe proposicion

thac the Federal GovernmenE has limited powers with respect

Eo Ehe sCaEes, unlike the unfectered authority which English

monarchs exercised over Ehe ParliamenE. By Ehe same Eoken,

however, in chose areas where Ehe Constitution granEs the

Federal GovernmenE che power Eo act, Ehe Supremacy Clause

diccates EhaE federal enactrnenEs will prevail over compeEing

sEaEe exercises of power. Thus, under our federal sErucEure,

$re do not have Ehe struggles for power beEween Ehe federal

and scaEe sysEems such as inspired Ehe need for the Speech

or Debace Clause as a resErainE on Ehe Federal Executive Eo

procecE federal legislacors. 445 U.S. aE 370.

Since a sEaEe legislacure is not a co-equal branch with Ehe

federal legislacure which passed Ehe Voting Rights Act or wich Ehe

Federal CourEs, Ehe firsc reason for the Speech and Debace Clause

has no relacion Eo chis acE,lon.

The second purpose for che Speech and Debace Clause is Eo assure

chaE che legislacors can be free co speek ouc wiEhouc fear of liabi-

licy. For chis proposicion defendancs cite Tennev v. Broadhove, 341

-6-

U. S.

F.2d

367 (1951) and Scar DisrribuEors Ltd. v. M4rino, 613

4 (2d Cir. 1980).

However, in boch of Ehose actions Ehe staEe legislaEor was

Ehe defendant. The cases discussed not an evidenEiary privilege but

rarher a con'ron law immuniEy from liability. The purpose of pro-

Eecting legislative independence is fully prorected if legislators

are relieved of the burden of defending Ehemselves. powell v.

McCormack, 395 U.S. 486, 501-506 (1959).

Plaintiffs do noE seek Eo hold eicher SenaEor Rauch or Senator

Marvin liable. Neither is a defendanc. NeiEher is puE in a posi-

Eion of having E.he burden of defending Ehe action. All plaintiffs

seek is to discover what evidence each has that either supports

Ehe clai-rns or defenses.

rn addition, in Tennev, supra, the legislaEor was sued for

money damages. IL is reasonable that possible financial liability

mighc inhibit a legislator from acting his conscience. IE is

noE reasonable EhaE merely having Eo disclose the process or sub-

sEance of legislative accions will prevenE a legislator from

acEing in Ehe inEerests of the people. Plaintiffs herein do nor

seek money damages from anyone, much less Senator Rauch or Senator

i,larvin. FurChermore, in Star Distributors, !gpra., an action to

enjoin a legislacive investigation, Ehe CourE was careful Eo point

ouE chaE che plaintiff had another remedy available; to refuse Eo

comPly wich che legislative subpoena and assert Ehe claim as a

defense in conEempE proceedings. rn this case, plaintiffs uusE

assert Eheir claim in a judicial proceeding or noE aE all. They

have no oEher remedy.

Finally, che ncEion of independence of scaEe legislacures is

anEiEheEical Eo che purpose of che Fourteenth AmencnenE and of

rhe Vocing Righcs Acc, boEh of which have che purpose of limicing Ehe

accions which sEaEes rnay cake. See, c.g., Stace of Souch Carolina

v. Kaczenbach, 383 U.S. 30I (f966).

After rejeccing boch the separaEion of

of legislacive privilege, che Supreme CourE

che doccrine of comicy. The Courc sEaEed:

po$rers and independence

in Gillock also considered

-7-

we conclude, therefore, that although principles of

cooity comnand careful consideraEion, our cases dis-

crose chat where important federal incerests are aE

stake, 3s in the enforcement of federal criminal

staEutes, comity yields.

:

Here we believe EhaL recognition of an evidenciary

privilege for state legislaEors for their legislarive

acEs would impair che legitimate inEerest of the

Federal GovernmenE in enforcing its criminal sEacutes.

with only speculative benefit to Ehe staEe legislative

process. 445 U.S. aE 373.

In Gillock the important federal inEerest was enforcement of

a criminal sEatuEe. However, enforceuent of the United States

ConsEiEution and of the VoEing Righrs Act is of equal importance.

This vra.s recognized by Ehe Court. of Appeals for rhe Fourrh Circuit

in Jordan v. Hucchinson, 323 F.2d Sg7,600-60l (4rh Cir. 1973),

in holding chat plainciffs, black lawyers, could maintain an action

againsE rhe members of an investigatory cornmiEtee of the Virginia

regislaEure seeking Eo enjoin Ehe legislators from engaging in

racially mocivaced harassmenE of plaintiffs and Eheir cliencs.

The Courc staEed, "The concepc of federalism, i.e. federal respecc

for sEaEe inscicurions, will noE be permiEEed to.shield an inva-

sion of citizen's constitucionar righEs." rd at GOl. Thus plain-

ciffs vrere allowed Eo maintain an action with legislaEors as defen-

dancs. The incrusion here is, of course, uuch rDore minor.

In addition, Congress has provided thac a prevailing plainriff

in an accion under che vocing Rights Acr or under 42 u.s.c. s19g3

is Eo be awarded his atEorney's fees. 42 u.s.c. SSt9731(e) and

1988. The reason for che fee award provision is thac Congress

recognized che imporcance of encouraging privace ciEizens, accing

as privace aEEorneys general, Eo enforce che Vocing Righcs Acc and

che Conscicucion. Riddell_lf. Narional Dqmocracic ParEv, 624 F.2d

-8-

53g,543 (5Eh Cir. 1980); 5 U.S. Code Congressional and Adminis-

Erative News 5908, 5910 (1976). The right Eo vore and Eo be fairly

represented are central Eo our democracic government.

DefendanEs' quoEe from BuEz v. Economou, 428 U.S. 478, 504

(1978), to the effecc EhaE Ehe iunrunity of a federal defendant

should not be greaEer Ehan the irmunity of a state defendant, is

inapposite. In Butz the question was whecher federal administra-

Eors should have greater innunity from liability for invading

an individual's consEiEutional rights than do similar scaEe admini-

sEraEors. The question involved comparing the protection of

42 U.S.C. 51983 and the Fourteenth Amendment Eo the proEecEion of

Ehe Fourth and Fifth Amendments Eo the United SEates Consticution.

The Court held Ehat the tto could not be raEionally distinguished.

Thac is a far cry from the situarion here in which Ehe U.S.

Congressional inmunicy, created by an unambiguous constiEutional

provision, is compared to the staEe legislaEor's privilege, a

creaEure of eiEher sEaEe sEaEuEe or unprecedented federal common

Iaw.

Even if Ehere is an evidentiary privilege for scaEe legisla-

Eors, in this case iE musE give way in the inEerest of truth and

juscice. The courEs have recognized chac privileges of government

officials are in derogaEion of Ehe Eruth and unrsE extend only Eo

che exEenE necessary Eo proEecc Ehe independence of Ehe branch in

quesEion. See, €.9., U.S. v. Nixon, 418 U.S. 683, 710 (L974);

U.J. v. Mandel, 415 F. Supp. aE 1030.

However, in this case privilege would be more Ehan in dero-

gaEion of the EruEh; it would prevent plainriffs from being able

Eo Prove an essenE,ial elemenE of Cheir claius. As discussed in

ParE I, above, discriminacory legislacive purpose is a necessary

elemenc of ac leasc one and possibly Ewo of plaintiffs'claims.

To hold one the one hand that evidence of legislative purpose is

necessary and on che ocher chac ic is privileged and inadmissible

is Eo make a mockery of boch rhe Conscicution and Ehe Vocing Righcs

Acc.

-9-

This reasoning vras recognized by the Supreme Court in

In Herbert the Court heldHerbert v. Lando, 44L U.S. 153 (L979).

that a television news editor could noE claim his First Asrenduent

privilege noE to disclose his sources, mocivations, and thought

Processes in a libel suir broughc by a public figure. The Court

recognized it would be grossly unfair co require the plainriff Eo

Prove actual malice or reckless disregard for the Eruth and pre-

clude hiro froo inquiring Eo the defendanEs' knowledge and motiva-

Eion. Id. aE 170.

The Court noced, in addition, Ehac it was particularly

unfair to allow defendanEs to Eestify Eo good faith and preclude

plainciff from inquiring into direct evidence of known or reckless

falsehood.

Thus the Court concluded that an evidentiary privilege,

even one rooted in the Conscicuti.on, ulrst yield, in proper circum-

sEances, -Eo a demonscrated specific need for evidence.

In chis case, BS in Herbert v. Lando, plaintiffs have demon-

strated a specific need for the evidence which SenaEors Rauch and

Marvin have which may establish'discriminatory purpose. This case

is, however, even sEronger chan Herbert v. Lando because, in

Herberg., defendanEs asserEed a ConsEiEuEional privilege. In Ehis

case che privilege, if one exisEs, corDes only from common law or

sEaCe sEaEuEe.

The Supreme CourE in Arlington Heights v. Metropolican Housing

AuEhoriEv, E!pE, recognized chac in some circumsEances a member's

EesEimony about mocivacion could be privileged and ciced CiEizens Eo

Procect Overcon Park v. Volpe, 401 U.S. 402 (1971). 429 U.S. aE 268,

n. t8. In Overcon Park Ehe Supreme Courc considered wheEher Ehe

SecreEary of TransporEaEion could be examined as E,o his reasons

for choosing Eo puE a highway chrough a park. The Courc held thac

under che circumsE,ances in chac case he could be examined. The Courc

reasoned chac alchough iE was generally co be avoided, when Ehere

lras no formal record decailing che reasons for che decision, ic is

permissible Eo examine Ehe menral process of decisionmakers. Id. aE' 420.

-10-

rn Ehis case, 8s in Overton Park, El:pr.l, there is no forrnal

record adequaEe to deEermine Ehe purpose, or even the process, of

the legislaEors. A direcE examination is, Eherefore, permissible.

III. THE TESTIMONY OF SENATORS RAUCH AND MARVIN IS

RELEVANT TO THE SUBJECT MATTER OF THE ACTION.

Rule 25(b) provides in pertinenE part, "ParEies rnay obtain

discovery regarding any Eatter, not privleged, which is relevanE

to Ehe subject matEer in Ehe pending action,... rt is not ground

for objecEion thaE Ehe informaEion sought will be inadmissible at

the trial if Ehe information sought appears reasonably calculared

Eo lead Eo Ehe discovery of adnissible evidence."

Thus, in order Eo be entiEled Eo prevent Ehe entire deposiEion,

defendancs utrst show that the "information sought was wholly

irrelevant and could have no possible bearing on the issue, buE in

view of the broad EesE of relevancy. at the discovery stage such a

motion will ordinarily be denied. " Wright and Mil1er, 8 Federal

Practice and Procedure 52037.

The tesEiiuony of the Ewo senators is relevant Eo the subject

macEer. Each senaEor was Chairman of a Redistricting Corrmitcee.

As discussed in Part. I above, these senaEors are believed Eo have

knowledge of the procedures used for developing Ehe apporEionment,s,

che criteria used by Ehe conurittees, oEher plans which were consi-

dered but rejected, and the docr:,nenEs and sEacemencs which indicate

che reasons EhaE Ehe General Assembly adopced, che proposals which

plaintiffs challenge.

Under the Supreme Court decisions in Cicy of Mob,ile v. Bolden,

supra, and Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing

lorpgratrion, supra, chis information is not simply relevant, it is

cricicar Eo plainciffs' abilicy Eo prove rheir claims.

Defendancs asserE, chac che legislative hiscory and official

records speak for themselves and chat che individual senacors'

EesEimony is, Eherefore, irrelevant. Plainciffs know of no official

records which contain any comi.Ecee proceedings, Ehe conEenEs of any

floor debate, Ehe criteria used by Ehe cornmiEcees, a lisc of pro-

posed aPPortionmenEs available Eo buE rejected by the comoiEEees,

- 11-

or Ehe contemporaneous sEaEemenEs of Ehe members. rf, however,

these records exist, perhaps SenaEors Rauch and Marvin can describe

them so that plaintiffs oay discover rhem.

FinaI1y, defendanEs assert EhaE Ehe tesEimony of legislators

is not relevanE when analyzing legislation. Plaintiffs do not seek

to use Ehe testimony to inEerpreE any ambiguity in the legislation,

asinD&W Inc. v. Charlotte, 268 N.C. 577 (1966), cited by

defendancs. Rather, plainciffs seek the tesEimony to establish

PurPose. See Arlington Heights, supra. To this end, the EesEiuony

is relevant.

IV. CONCLUSION

"Exceptions Eo Ehe demand for every man's evidence

lighcly created nor expansively construed, for they are

are not

in dero-

U.S. at 170.gation of Ehe search for truEh.rr Herbert 11 L4ndo, 44L

"These rules shall be construed Eo secure fairness in adminis-

EraEion, ;. . Eo Ehe end thac the Eruth may be ascertained or pro-

ceedings justly determined. " Rule L02, F.R.Ev.

The search for EruEh requires thac defendants not be allowed

Eo ascerE a privilege which wilk deprive plainEiffs of che proof

of one of Ehe necessary elements of their claims. To require

plaintiffs to prove purpose and Eo refuse Eo allow Ehem Eo inquire

abouc ic is neicher fair nor jusc.

Plainciffs, Eherefore, request that the subpoenae of SenaEors

Rauch and Marvin not be quashed.

This 3O day of December, 1981.

Chambers, Ferguson, WatE, Wallas,

Adkins & Fuller, P.A.

Suite 730 East Indepence PLaza

951 Souch Independence Boulevard

Charlocce, North Carolina 28202

704/ 375-8461

AEEorneys for Plainciffs

v . sb I vrtrrld/z vf&

LESLIE J. WINNER

-L2-

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I certify that I have served Ehe foregoing Plaintiffs' Response

To DefendanEs' Motion To Quash Subpoenae Or In The AlternaEive For

A ProtecEive order on all other parties by placing a copy thereof

enclosed in a postage prepaid properly addressed wrapper in a posE

office or official depository under Ehe exclusive care and custod,y

of the Uniced States PostaL service, addressed Eo:

!,1r. James Wallace, Jr.

NC Attorney General's 0ffice

Post Office Box 629

Raleigh, NC 27602

l,lr. Jerris Leonard

9OO ITEh SE. NI^I- Suite 1020

Washington, DC 20006

1981.This 70 day of December,

-13-

RALPH GINGLES,

v.

RUFUS EDMISTEN,

I

IN THE

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE

E.ASTERN DISTRICT. OF NORTH CAROLINA

RALEIGH DIVISION

NO.81-803-CIV-5

ec al.,

Plainciffs,

eE al.,

Defendancs.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

PIAI}TTIFFS' RESPONSE TO

DEFENDANTS' MOTIoN T0 QUASH

SUBPOENAE OR IN THE ALTERIIA.

TIVE FOR A PROTECTI\TE ORDER

I. Introduccion

Plalntlffs, black ciclzens of Norrh Carollna, bring chis

acElon Eo enforce thetr rlght to voEe and co have equal repre-

senEatton. They asserc claius under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth

Anrendments Eo the Unlted SEates Constlrurlon and under SS2 and 5

of the Voclng Righrs Acc of 1965, as aoended, 42 U.S.C. S$1973

and I973c ("fhe voting Rlghrs AcE"), challenging rhe apportloruqenE

of che Norch Carollna General Asseobly and che UniEed SEaces

Congresslonal dlscrlccs in North Carolina. Plainrlffs a1lege chac

the apporclonnents were adopted sich che purpose and effect of

denying black cLEtzens che rlght Eo use cheir votes effectively

and chac Ehe General Assenbly apporEionnencs violaEe Ehe "one

person-one voce" provislons of che equal protection clause.

Dlscovery has connenced. On Deceober 3, I98I, plaintiffs

noclced the d,eposiclons of and subpoenaed Senacor Marshall Rauch,

che Chairmn of che Norch Carollna Senase's ComiEtee on Legls-

laclve Redlscrtcctng and SenaEor Helen t'tarvln, che Chairuan of

che Norch Carollna Senace's ComiEcee on Congressional Rediscriccing.

The subpoenae request chae Ehe senaEors bri.ng to Ehe depositions:

D,ocusencs of any kind shich you have in your possession

whi.ch relaEe Eo che adopclon of SB 313 t87l during ehe l98l

Session of che Norch Carolina General Assenbly. This

requesC includes but is noE IiEiE,ed Eo correspondence,

oeuoranda or oEher wricings proposlug or objecting to

any plan for apportionuenc of North Carollna's SenaEe

ICongresstonall dlsErtcts or any criceria cherefore.

DefendanEs Eove Eo quash the subpoenae on the grounds that

neither Senator can gtve any relevanE Eestitrc,ny and thac all Eesti-

uony of both senacors ls prlvileged. plainciffs oppose this uotion.

Defendants' @Eion to quash is an objecclon to Ehe enttre deposi-

clons. Plainriffs have noc asked partlcular questions. rf prain-

tiffs had caken che deposiElons, Ehe inquiry would have incruded the

followtng

1. Ihe naEure of che Senator,s role as Chairoan of a

Redistrtctl.ng Comiccee ;

?. The sequence of events whlch lead to the enactnenc of

uhe redtscricclng legislarlon;

3. No::aal procedrrres for enacclng this t1rye of legislati.on;

4. The critarla adopted by che redlscridcing cou@iEtees;

5. Factors uormally consldered ioporcanr in redistrlcting;

5. Ttre exisEence of any substanElve or procedural departures

froo norual;

7. The exiscence of docuaenEs, official records, or r.rnoffi-

cial records whtch conEain Ehe substance of comiEEee, subcomiEcee

or whole SenaEe debate

8. Ttreir knowledge of che conteurporary staceuenEs by oea-

bers of, Ehe legislaEure of che reasons for adopting or rejeccing

proposed apportlonoenE plans ;

9. Th,e exlscence of wtcnesses Eo sEate.encs as descrtbed ln

paragraph 8 above; and

10. Ttre exlscence of ocher pic,nesses who observed or were

involved in che pEocess chas led co che enacEa{lnE of che challenged

aPPorEionllenEs.

Because che Senacors were che chairoen of che rediscriccing

comiEEees which rrere responsible for reporcing co rhe full Senace

a reson'ended apporclonuenc for enaccuenc, plainciffs believe each

has knowledge relevanc Eo Ehese inquiries.

-2-

One of plainciffs' allegations is chat, Ehese apporcionruenEs

discrininate againsc chern on the basis of race in vlolation of

che equal proceciion clause of rhe Fourteenth Amendmenc. In

order to prevall on Ehl.s claiu, plaintiffs uu,sc show EhaE Ehe

plans \rere conceived or n:intained wtth a purpose co discrioinaEe.

cicv of Mobile v. Bolden, 446 u.s. 55 (1990); Illllere of Arlingron

Hefehcs v. ltecropoll , 429 U.S. 252 (1977);

Washingcon v. Davts , 426 U.S. 229 (1976).

In addttlon, iE 1s arguable thaE plaintiffs nusE show purpose

co diluce black voEe in order co prevail in their clatms under 52

of the Voclng Righcs Acc. See ttobile v. Bolden, S.!14, WashinsEon

v. Flnlev, _ F.2d _, (4ch Cir., ,A0-L277, Noveober 17, l9g1).

The Supreoe CourE Ln Arlingcon Helghrs, !gpE, noEed Ehac,

"Deceruining whecher invtdlous discrtoinatory purpose lras a Eocl-

vaclng faccor denands a senstt,ive iirquiry inEo such circuostancial

anddirecc evldence of incenc as ruay be avallable." q29 U.S. ac 25d.

A^oong che subjeccs of proper i.nquiry for provlng incenc lisced by

Ehe Supreue Court are:

1. The speciflc sequence of events leading up Eo the chal-

Lenged declsion;

2. Departr:res froa nomal procedural sequencei

3. Substaucive departures froa factors usually considered

i,nporcanc; and

4. Conteuporary scaceEencs by oeobers of che decisionoaking

body, oi.nuces of ics oeetings, or reports.

Arlingcon Heichts v. l.lecro Housing Corp., 429 V.S. aE 257:268. See

also McMillan v. Escaobia Co., 838 F.Zd, LZ39 (5ch Cir. lggl);

U.S. v. Cltv of Parura , 494 F. Supp. 1049, 1054 (N.D. Oh. 1980) .

Senacors Rauch and Marvin would be expecEed co give EesEltrony

relevanE. !o each of chese inguiries. rn addiclon, che supreue courr

recognized, "In sooe exEraordinary insEances che oeobers oighc be

called co che scand aE criaL to cescify concerning the purpose of

offtcial accion,...." Arlingcon Heighcs, .g.!18,.

-3-

J

rn addicion, defendancs have raised as Ehe Eourth Defense

in their Answer Ehac, "The deviations in the l9g1 ApporclonEent

of che Genera! Asseobry erere unavoidabre and are justified by

rational sEate policies." This defense relates Eo platnciffs'

"one person-one voEe" clala. rf allowed co cake Ehe deposiElon

of senacor Rauch, chairuan of che senaEe cosroictee on Legisla-

tive Redtstrlcting, plainttffs would inquire abouc the rationar

state'pollcles Ehac caused the popuration deviacions in che

senate plan and would inquire about che exiscence of oEher plans

thac uec Ehese policies buc had lower populacion deviaci.ons.

These depositions and chese rines of inguiry .are perui.tced

under Rures 26 and 33 of che Federal Rules of civil procedure and

under the Federal Rules of Evidence.

II. THE TESTIMONY OF SENATORS RAUCH

AND MARVIN IS NO.T. PRIVILEGED.

Rule 501 of che Federal Rules of Evidence provides, in per-

Elnenc parE,:

Excepc as ocherwtse requireit by the Conscj.rucion of che

Unlced St,aces or provided by Act of Congress or in rules

prescrlbed by che Supreoe Court pursuant, Eo sraEuEory

auEhoriEy, che privilege of a wtEness, person, governoenE, .

ScaEe, or policical subdivision chereof shall be governed

by che principles of che conhon law as chey oay be incer-

preced by che courcs of che United Scaces in che tighc of

reason and esperience.

This rule applies co discovery as well as to crial. F.R.Ev.,

RuIe 1I01(c). ftlus, ln order to decernine if rhe cesciuony of Senacors

Rauch and ldarvin ls privileged wirhtn che oeaning of Rule 26(b) of

che Federal Rules of Clvll Procedure, che Cour! rcusE deceroine lf iE

is covered by Rule 501 of che Rules of Evldence. See !|+_9i11g!,

445 U.S. 360, 365 (1980).

Defendancs asserc a legislacive privilege parallel co che Speech

and Debace Clause of Arcicle I, $6 of che United SEaces Consci.cucion.

However, che Speech and Debace Clause applies only co ueobers of che

-4-

uniced states congress, noc Eo stace legisrators. Nor does t,he

scaee sEacuEe escablishing the privllege in stace courEs escablish

the privtlege under the Federal Rules. u.s. v. Gtllock, 44g u.s.

at 368,374. Defendanrs do noc ciEe any provision of che uniEed

scaces consticutlon, AcE, of congress, or supreue court rure which

escabrishes a privilege whtch exeEpcs sEate regislators frou Ees-

tlfying. Ttrus Ehe courc oust deEeraine if Ehe Eesrir0ony is pri-

vlleged "by che prtnciples of cooaon law as chey uray be interpreced

by che courts of che united sEaEes ln lighr of reason and expertence.,,

F.R.Ev., Rule 501.

Defendancs cite no case in.which legislative privilege is

excended co che cesE.iaony of staEe legislators, and plainciffs know

of none. U.S. v. ltandel, 415 F.Supp. 1025 (D.Md. 1975), whlch

defendanEs ctEe in support of che evidentary privilege, i.s a case

ln which a state governor asserted iuounity froo crimlnal prosecu-

tiorl and Ehe courc held rhac chere lras no i@unity for governors

dolng leglslative acEs. The language quoced by defendanrs ls only

dtcta, largely irrelevanc to che lssue before thac Court.

rn order ro determlne whecher a prtvilege pararler co che Speech

and Debace clause should be creaced for scate legislacors, iE is

herpfur co analyze Ehe purposes of che speech and Debace clause.

IEs hlscory is sec ouc i.n Kilbourn v. Ttrompson, tO3 U.S. 169, 2G

L.Ed. 377 (1881). The crause \ras paEEerned afcer an English parlia-

menEary provlsion which was designed co stop che cror.,n from ioprisoning

Ileobers of Parriaroenr for sedicious libel. 2o L.Ed ac 390-391. As

cranslacid inco che Aoerican republican foru of goveEnoen!, che

clause has cwo pqrposes:

l. lo procecc che ueobers of the co-equal legislactve

branch of che federal governoenc from prosecucion

by a possibly hosctle execuE,ive before a possibly

hoscile judi.ciary, Kilbourn v. Ttroupson, SggIll; and

2. fo preserve Ehe independence of rhe legislacure by

freeing che uernbers froo che burden of defending

cheoselves in courE and of ul!im'ce liabilicy.

Doobrowski. v. Easrland, 387 U.S. g2 (f957).

-5-

Neicher of these reason is applicable co Ehe moEion before

Ehe CourE.

Since a staEe legLslacure is noE one of che Ehree co-equal

branches of che federal governnen!, the firsE reason d,oes noc

apply. The supreue courr reached this conclusion in u.s. v. Gillgck,

.rygg, in holding chat, a srate legislacor is nor imune froo

federal prosecution for crtues cormitced in his legislacive capaciEy

and chac he had no prtvirege againsr the admission inco evidence of

his regtslaElve acEs. Boch would have been precluded if a privilege

siailar in scope to Ehe Speech and Debace Clause applied. In

reaching che conclusion che Courc said:

The firsc ratLonale, resctng solely on Ehe separacion-of-

porrers doctrine, gives no suppor! Eo Ehe granE of a prlvi-

lege to sEaEe legislacors in federal criqinal prosecuclons.

IE requlres no ciEation of autrhoriEles for che proposiEion

that che Federal GovernmenE. has liai.ced powers with respect

Eo che scaEes, unlike che unfeccered auEhorlty which English

oonarchs exercised over Ehe parllaoenc. By Ehe same Eoken,

however, in c.hose areas where che ConstiEuElon grancs Ehe

Eederal GovernuenE che power Eo acE, Ehe Supreoacy Clause

dlctaces that federal enacEuencs will prevail over coupecing

sEace exercises of power. Thus, under our federal sErucEure,

we do noE have the sEruggles for poerer bec,ween che federal

and sEate sysEens such as inspired che need for che Speech

or Debace Clause as a resErainE on the Federal Executive co

procec! federal legislarors. 445 U.S. ar 370.

Since a scace legLslacure is noc a co-equal branch wich che

federar legisracure which passed che vocing Rlghts AcE or wich che

Federal CourEs, che firsE reason for che Speech and Debace Clause

has, no relacion co chis acEion.

The second purpose Eor che Speech and Debace Clause is Eo assure

chac che legislacors can be free co speek ouc wichouc fear of liabi-

licy. For chis proposicion defendancs cice Tennev v. Broadhove, 341

4rl

-6-

u. s.

F.2d 4 (2d Cir. 1980).

Ilowever, in boch of chose acEions che sEate legislator was

the defendant. rhe cases discussed noc an evtdentiary privilege but

raEher a cornron 1aw ioounity froo liability. The purpose of pro-

tectlng leglislati.ve independence !s fully prorecred if legislators

are relieved of the burden of defending theoselves. powe1l v.

}{g1!gEE, 395 u.s. 486, 501-50G (19G9).

Platnclffs do not seek co hold eicher senacor Rauch or Senator

Marvin ltabre. Nelther is a defendanc,. Neicher is puc in a posi-

clon of having the burden of defending rhe action.. Alt plainciffs

seek is to discover what evidence each has EhaE, eiEher supporEs

che clai.qs or defenses.

In addicton, tn @ga, -W., che legislalor rras sued for

Eoney daoages. rE i.s reasonable thbr possible financial liabilicy

oighc tnhibic a legtslaror from acting his conscience. It ls

noc reasonable char uerely havtng co dlsclose che process or sub-

scance of legislaEtve acclons wilt prevent a legtslator froo

acclng in the incerests of rhL people. plainclffs herein do nor

seek aoney daoages froo anyone, ouch less Senator Rauch or senaEor

l,larvtn. Furthermore, in Star Dlstributors, g.lg, an actrion Eo

enJoin a legislaclve lnvescLgacion, the Court was careful Co poinC

ouc chac che plaincj.ff had anocher rernedy available; Eo refuse Eo

cooply with che legislacive subpoena and asserc Ehe clatm as a

defense in concempc proceedings. In chis ease, plainriffs EusE

asserc chelr claim ln a judi-ci.al proceeding or nor as all. They

have no ocher renedy.

Finally, Ehe nocion of tndependence of scace leglslacures is

antiEhecical co che purpose of che FourceenEh A.Bencroenc and of

che Vocing Righcs Acc, boch of which have che purpose of tiaicing che

acEions which scaEes nry Eake. see, e.g., stace of souch carolina

v. Kaczenbach, 383 U.S. 30I (1966).

- Afcer rejeccing boch che separacion of powers and independence

of legislaclve privllege. che Supreoe Courc in Gtllock also considered

che doccrine of couricy. The Courc scaged:

357 (1951) and Star Disrriburors, Lrd. v. Marino. 513

-7-

l{e conclude, Eherefore, thac although principles of

couiEy coqurand careful consideracion, our cases dis-

close chac where i.aportant federal inEerests are aE

scake, as in che enforcenenc of federal criuinal

staEuces, comlEy ylelds.

:

llere we believe Ehat, recognicion of an evidenciary

privtlege for scate legislacors for thelr leglslacive

acts would irnpair the legicinaEe inceresc of che

Federal GovernuenE, in enforcing its criminal sEaEutes.

wlth only speculative benefic eo Ehe scate legislacive

process. 445 U.S. ac 373.

rn Glllock Ehe l,porEant federal interest was enforceoenc of

a crioinal scaEute. However, enforceuent of the united sEaces

conscituci.on and of the voctng Rights Act is of equar iuporEance.

This was recognized by the courc qf Appears for rhe Fourch circuir

ln Jordan v. Hucchinson, 323 E.2d 597, Go0-501 (4ch cir. Lg73) ,

tn hordlng chac plainci.f,fs, black lawyers, could moinratn an acEion

agalnsc che meobers of an i.nvestigatory comittee of che Virginia

legislacure seeking co enJoi.n rhe legislacors froo engaging in

raciarly aoclvaced harassnenc. of prainEiffs and cheir criencs.

The.court sEaEed, "The concepr of federalisu, i.e. federal respecE

for scace insclcucions, will noc be peruricced co.shield an invar

sion of clcizen's consciEucional righEs." rd at 501. Thus plain-

ciffs were allowed co oaincain an action with legislaEors as defen-

dancs. The incrusion here is, of course, otrch oore mj,nor.

rn addicton, congress has provided Ehac a prevailing plainciff

in an accion under che Vocing Righcs AcE or under 42 U.S.C. Sf9g3

is co be anarded his acc,orney's fees . qZ U. S.C. S$I973!(e) and

1988- The reason for che fee award provision is chac congress

recognized che ioporcance of encouraging privace cicizens, acrlng

as privaEe aEEorneys generar, Eo enforce che vocing Righcs Acc and

che consciEuEion. Riddelt v. Nacionar Deqocracic parcv, 624 F.zd.

-8-

539, 543 (5ch Cir. 1980); 5 U.S. Code Congressional and Aduinis-

Eracive News 5908, 5910 (L975). The righr Eo vore and Eo be fairly

represented are cencral co our deoocratic govelnuent.

DefendanEs' quoce froa BuEz v. Economou, 4ZB U.S. 478, 504

(1978), Eo Ehe effecc chaE Ehe imunity of a federal defendanc

should noE be greaEer Ehan the imtrnity of a scaEe defendanc, is

inapposlce. rn Bucz che quesEton was whecher federal adoinistra-

cors should have greacer innunity froa liabiliry for invading

an indivlduals conscicucionar rights chan do sioilar scaEe adoini-

straEors. fhe question involved cooparing Ehe proEeccipn of

42 U.S.C. $1983 and che FourreenEh Amendmenc Eo Ehe proEection of

the Fourth and Fifch Aoendments Eo Ehe uniced staEes constiEution.

lhe courc held chac Ehe Erro could not be racionally dlsrtnguished.

Thac is a far cry froa Ehe sicuarion here in which rhe U.S.

Congressional lurmrniEy, creaEed by an unanbiguous consciEuclonal

provisi.on, is compared to che stace legislacor's privileg€, El

creacule of eicher scaEe sEatuce or unprecedented federal cottrlc,n

law.

Even !f Ehere is an bvidenciary privilege for srat,e legisla-

tors, ln chis case iE oust glve way in uhe interest of c:rrch and

justice. ftre courcs have recognized chac privileges of gover:roent

offlcials are in derogacion of the cnrch and m,rsE, extend only co

che excenc necessary Eo proEecE the independence of the branch in

quesEion. See, e.g., U.S. v. Nixon, 418 U.S. 683, 710 (1974);

U.S. v. Mandel, 415 F.Supp. ac 1030.

llowever, ln chis case privtlege would be -^re chan i.n dero-

gaclon of che cruch; it would prevenE plainrlffs froo being able

Eo prove an essenEial eleoenc of cheir claius. As discussed in

ParE I, above, discrioinacory legislaclve purpose is a necessary

eleoenc of ac leasc one and possibly cwo of plaintlffs'c1alos.

To hold one lhe one hand chac evidence of leglslacive purpose is

necessary and on che ocher chac ic is privileged and inadoissible

is co m.ke a oockery of boch che ConsciEution and che Vocing Righcs

Act.

-9-

fhis reasoning was recognized by che Supreue Courc in

Herbert v. Lando, 441 U.S. 153 (rg7g). rn Herberr rhe courc held

EhaE a telerrtsion news ediEor could noE craim his First Aoenduent

privilege not, Eo disclose his sources, ooEivatlons, and, choughc

processes in a libel suic broughc by a public figure. The courc

recognized it would be grossly unfair co require the prainciff co

prove actual roalice or reckless disregard for che Eruch and pre-

clude him froo inquiring Eo che defendants' knowledge and Bociva-

Eion. Id. ac I70.

The Court noced, in addiEion, chac it was parcj.cularly

unfair co allow defendancs co cestify to good faic.h and precrude

plainclff from inquiring into direcc evidence of knorsn or reckless

falsehood.

Ttrus che Courr concluded chat an evidenci.ary pri.vllege,

even one rooEed in che constltucl.ofi, lBust yield, in proper circua-

sEances,-Eo a deuonsErated specific need for evidence.

In chls case, as in Herbert v. Lando, plaintiffs have deuon-

straced a speclflc need for E,he evidence which Senacors Rauch and

Marvi.n have whlch uay escabrish'dlscrtoinatory purpose. This ease

is, however, even scrohger chan Herberc v. Lando because, in

HSg@g, defendancs asserEed a ConsE,icuctonal privrilege. In chis

case Ehe privilege, if one existb, co8es only froo comon law or

sEaEe gEaEuEe.

The suprene courc in Arringcon Heighcs v. MeEroporican Housing

Auchoricv, sl4-E3, recognized Ehac in soue circuoscances a uember's

cescirnony abouc troEivaEion could be prlvileged and ciced cicizens co

Protect Overcon Park v. Volpe, 40I U.S. 402 (1971). 4Zg U.S. ac 25g,

n. 18. rn overton Park che supreoe courE considered whether the

secreEary of TransporEaE,ion could be exaained as co hi.s reasons

for choosing Eo puE a highway chrough a park. The Courc held rhac

under che circuosEances in chac case he could be examined. The courc

reasoned chac alchough ic tas generally co be avoi.ded, when chere

was no forual record decaili.ng Ehe reasons for che decision, ic is

peraissible co examine Ehe oencal process of decisionmakers. rd. ac 420.

-l0-

In chis case, as in Overton park, supra, there is no forual

record adequate Eo deteraine Ehe purpose, or even Ehe process, of

the legislaEors. A direct ex:nination is, Eherefore, peroissible.

III. THE IESTIMONY OF SENATORS RAUCH AND MARVIN IS

SU OF

Rule 26(b) provides in pertinenE parc, "parEles uay obcain

dlscovery regarding any natter, noE privleged, which is relevan!

Eo Ehe subjecc n'Eter in the pendlng action, ... IE i.s not ground

for obJection thar che lnfonnatl.on soughr rrirl be inadoissible ar

che cri.al if che lnforuacion sought appears reasonably carcuraced

to lead Eo Ehe discovery of adoissible evidence."

Thus, ln order co be enticred Eo prevenc the €ncire deposition,

defendanrs ousE sho!, thac che ,'info:mac,ion soughc was wholly

irrelevanc and could have no posslble bearing on Ehe issue, buc in

'riew of che broad tesE of rerevancy. at the dlscovery sEage such a

roocion wlrl ordinarlly be denled. " wrlght and Mirler, g Federal

Praccice and Procedure 92037.

Ttre Eescltrony gf E,he Epo senators ls relevanc co the subject

EriEcer. Each senaEor eras chairnon of a RedtsEricElng comittee.

As discussed ln Part r above, these senacors are believed co have

knowledge of che procedures used for developi.ng che apporcionmencs,

che crlcerla used by che couotEcees, ocher plans which were consl-

dered but rejected, and che docr:menEs and scatenencs which lndicace

Ehe reasons chac Ehe General Assembly adopced che proposals which

plaintiffs challenge.

under che supreoe courE decisions in cicv of Mobile v. Bolde!,

supra, and Vlllage of ArlingCon Heighcs v. MetroDoliCan Housinu

9orporallon, .gels1,, chis infornacion is noc sioply relevanE, iE is

crlclcal co platnci.ffs' abilicy Eo prove cheir clalos.

Defendancs asserE chac che regislacive hiscory and offi.cial

records speak for cheoserves and chac che individual senacors'

cescioony is, Eherefore, irreLevanc. plainciffs know of no official

records which conEain any comiE,Eee proceedings, Ehe conEencs of any

floor debaCe, Che criEeria used by Che sqmiggsg3, a IisE of pro-

posed apporclonuents available co buc rejecced by Ehe con,iEEees,

-ll-

.l

or lhe conEeEporaneous sCaEeEenEs of the lleEbers. If, however,

chese records exist, perhaps senalors Rauch and Marvin can describe

Ehem so char platnciffs oay discover cheu.

Flnally, defendants assert chac Ehe Eesti'ony of legislators

is noc relevant when analyzing legislacion. plaintiffs do noc seek

Eo use Ehe cesriEony to inEerprec any aubiguicy in the legisration,

as in D & W. Inc. v. Charlocre, 268 N.C. 577 (1965), ci.Eed by

defendants. Rather, pratnclffs seek the EesEtmony co escabrish

purpose. See Arlingcon Heighis, .9gg,. To thls end, the tescinony

is relevanc.

IV. CONCLUSION

"ExcepElons co the deoand for every Ean's evidence are noE

lightly crealed nor expansively construed, for they are in dero-

gatton of the search for truth." Herbert v. Lando, 44L u.s. ac 170.

'These rures sha1l be const:rred Eo secure fairaess in adoinis-

tratlon,;.. to Ehe end chac che EruEh oay be ascert,ai.ned or pro-

ceedingi Jusc1y deceroined." RuIe. 102, F.R.Ev.

The search for cruth requlres thac defendancs not be allowed

co ascert a prlvilege which wl1k deprive prainciffs of che proof

of one of the trecessary eleoenEs of cheir claios. To requlre

plainclffs Eo prove purpose and Eo refuse co allow cheo Eo lnquire

abouc lc is neicher fair nor Jusc.

Plainttffs, Eherefore, requesc thac che subpoenae of Senacors

Rauch and Marvin noc be quashed.

Ttris day of December, 1981.

Chaobers, Eerguson, WaEE, Wallas,

Adkins & FuLler,.P.A.

Suice 730 Easc Indepence PLaza

95I Souch Independence Boulevard

Charlotce, Norch Carolina 28202

704/ 375-846L

Actorneys for Plainciffs

?o

-L2-

.t - - )

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

r certLfy that r havc sernred Ehe foregolng plalntlffs, Response

To Defendenls' btlon To Quach subpoenae or rn rtre Alteraatlve For

A Procac,tl,vo orda.r oa all ochcr partles by plactng a copy chereof

enclosad tn a poctagc prepaid properly eddressad lrrspper in a posc

offlce or officl,ar drporltory under Ehc exclusivc carr end cuatody

of chc Uniced Scates Poetal Scrvtee, addrersed Eo:

l{r. Jaoes Illallace , Jr. }.Ir. Jerrts Laonard

NC Attorney General' s Office 900 l7ch SE. NW

Posc Offlce Box 529 Suire 1020

Raletgh, NC 27502 Washingron, DC 20006

Ttrls ?O day of Daceober, 1981.

-13-

(_ r..-i

-

Mernorandum

From:

Re : Dlscovery of Leglslators r Motlves

January 18, L98Z

iTo : Jack Greenberg, Jlm Nabr1tr',st",r" Ralston, LowellJohnston, peter sherwood,, grrr Lann i"", i.frlckPatterson, Ga11 wrlght, Beth L1ef, steve wirrt",and Jln Llebman

Napoleon B. w11l1ams, 0". k0 lt

rn the North carollna reapportlonment case, Glnqlesv. Edmlsten- we lssued subpoenas to """io", fr"il8ffiome lioEh carollna stitl Leglslature. The scopeof_ dlscovery encompassed, vlrtuillt-;il lnformatlonrelatlnF to the enactment o.f the staiu '" """ppo"iiorr-ment. scheme, 1lcIud1ng knowled,ge of trre reasons forenactment of the relevant statutes.

Defendants f1-1ed.- for a protectlve order, clalmlngprlvllege. l'Ie obJected. The dlstrlci court d,ec1ded.1n our favor- Attached, are the supportlng memo"irroa.r am not convlnced that they provtal the dompleteanswer to th1s lssue of uslng leglslators to d,lscoverthe motlves or lntent of the-regrsliiior,. rf youhave any ldeas on how thls problem should be ai_proached and resolved, r welcome your communlcatlonof them.

Thank you.

NBW,/T

Attach

RAIPB GINGLES, eI. a1.,

Plai.ntif,f s,

v'

RTFUS EDl,tISlEN, 6tc., et a1.,

.:rL E n

IN ItrE UNfTED STATES DISTRICT COU.RT fttrn *

FOR THE EASTERN DTSTRTCT OF NORTS CAROLTITA -,-'. 1 4lggl

RArErcE orrrr rolr*r

No . r r:rff.fir"ffi":"r:?,,

BRTEF IN SUPPOIiT OP DETEICDANTS '

MOTION TO QUASH SUBPOENAE OR TN

TEE AITEPNATT"E FOR A PROTECTTVE ORDER

Detendants.

INTP.ODUCTION

Plaintiffs have subpoenaed Nortir Carolina Senators Pelen Marvin

and l{arshall Rauch for the purpose of taking their d,epositions on

December 17, 1981. lhe prospectlve deponents, members of the llorth

Carolina General Assembly, are not parties to thls action. Defendants

contend that the matterE about which llarvin and Rauch 'rou1d be asked

to give tastinony are prlvlleged, hence non-diseoverable ulder Fed. R.

Clv. Pio. 26(b)(1), and that such natters are irrelevant to the action,

hcnce also non-diseoverable under Fed. R. Clv. Pro. 26(b) (1).

I. TIIE DOCTRTNE OF LEGISI.ATWE PRTVTLEGE PREI/ENTS TNQUTR,Y INTO

Rule 26 (b) (1) speclfically excludes from the scope of othervlse

dlscoverabLe naterial natters which are privileged. The conuron-Iaw

doctrine, variously referred to as legislative privilege or legisla-

tive imunity, affords legislators a privilege to refuse to ansrrer

any guestions concerning legislative acts in any proceeding outside

of the legislature. See tnited St?tes v. Mandel. 415 F.Supp. 1025

(D. Ud- 1976). Thl.s c€nccpt ls codified in U.C. cen. Stat. 5120-9,

rhich gruarantee8 freedom of spcech and debato in thc legislaturc and

in ttre leglslativ" pro"."".1

ITb. section rEade as follons:

'Tbe ueo.bers sha11 have f,reedorn of speech and debate in

the General Assenbly, and shall not tre lj.able to inpeachnent

or guest1.on, in any court or place out of the General

Assee.bly, for words therein spoken; and shal1 be protected

except ln caseg of crlme, froro all arrest and imprisonnent,

or attachnent of property, during the time of their going to,

coming frorn, or attending the General Assembly."

North Carolina'E statutory provision para1le1s the Speech or

Debate Clause of the Pederal Constitution (Art- I, 56), as well

as tbe statutot'y and constitutional enactuents of trost other

statq!. In interprcting the federal constitutional versi.on of

thl.s doctrina ttre United Statssupreuc Court has written:

thc reason for the privilege is clear. It rras

rell srrun rized by Ja^trcs wllson an influential

merobcr of the Couolttec of Detail which tras

responslble f,or the provision in the Fedcral

Constitution. "In order to enable and encourage

a rePrese.ntative of the public to discharge his

public trust r.rith firrnness and success, it is

indlspensably necessary, that he should enjoy

the fullest liberty of speech' and t!'at he

should be Protected from the resentment of every

one, hosever porrerful, to vhon the exereise of, that

liberty may'oceasion of,fence." TenneY v. Broadhove,

341 u.3. 3e7 (1951) at 372'73 (cffi

Legi.slative privilege has a substantive as well as evidentj.ary

aspect, and both are founded in the rationale of legislative

integrity and independence, enunciated by the Framers and proporurded

trro cstrturies later by tbe Supreire Coutt. lhe su.bstantive asPect

o! the doctrine affords leglslators immrurity frorn civil and cri:uinal

liability arising fron legislative proceedings. The evidentiary

aspect af,fordg legislators a privilege to refuse to testify about

legislative acte. in proceedings outside the legislative halIs. United

State v. :landel, supra at 1027.

At issue here is tlre evirlentJ.ary facet of the privilege and,

specifically, whether such a state-affordetl evj.dentiary privilege

shou:Ld have eflicacy ln the federal c"oults. It Is clear that the

S1:eech or Debate Clause of the federal constitution would preclude

the depositlon o! a lnGubet of Congress in arl analogous si'tuation.

In @, 408 U.S. 508 (1975), the Coutt stated,

'Mr bcyond doubt that tha Speech or Debate clause Protects against

inguiry lnto acts that occur in the regular course of the legislative

procsas and lnto the motivation lor those acts.n 408 U.S. at 525.

)

L

-3-

Defendants acknowledge that even the privilege granted federaL

Iegi.slators Ls bounded by couatervailing considerations, particularly

the need for every Ean's evidence in lederal cririinal prosecutlon.

As E@ furth€r Etates, "the privilege ia hroad enough eo ingure

the hlstoric lndependence of the Legislative Branch . . . but narrow

enOugh to guard against tlre excegses of those who rould corruPt the

process by.corrupting its meubQrs." 408 u.s. at 525. Defendants

trotion attetrE)tE, however, to conceal no tcorruption".

with the boundaries of the federal legislative privileoe in

mind, te turn to the question of the scoPe of Pala11e1 state Privileges.

!{hatever their exteEt and rango of applj.cabllity i.n state court, the

United States Suprervre Coust has ruled that state privileges v'i11, at

tines, yeil.d to overriding f,ederal interests in federal courts'

united states v. G1110ck, 1oo S.Ct. 1185 (1980). The Court has

recogmized only one federal interest of iurportance sufficient to

mcrit dispensing wittr tlris state-granted pri.vllege: the prosecution

of federal crines.

The Supreoe Coutt has never sg:arely addressed the issue pre8ented

here: whether a state legislator's evid.entlary privilege reoains

intact in federal civil proceedings. rn Tennev v. Broadhove, s!g,

the court ruled that a legislator's su]!g@tE irrur:nity from suit

withEtood the enactnent of, 42 U.S.C. 51983, attd thus state legislators

lrerenotsuscep,tibletosuitforr'rordsandactswithinthepurvievr

of, the legislative Process. Although it deals witlr tlre substantive

aspect of the privilege, Tenney is instructlve, insofar as the -court

there gave great def,erence to ttrc Etate's oun doctrine. Recently,

in united states v. Glllock, 3uP3, a criuinal case involvlng the

evldentiary facet of, leglslatlve lmrurlty, the Colrrt clted Tenney

for thG proposition that all federal courts uust endeavor to aPply

state legislative privilege. In @, howcver, the coutt ruled

.'.:,!,..!,J4--_

-4-

that the Tennessee speech or Debate clause wourd not exclud,e

inquiry i'uto the leglslati.ve acts of the defendant-legislator

prosecuted for a federal criminal off,ense.

Throughout the supreue court's activity in thi.s field no

dlstinction has been drann between substanti.ve and evidentiary

applications of ttre privllege f,or the purpose of determining the

clficacy of legislative privilege in f,ederaL court. Thus, the