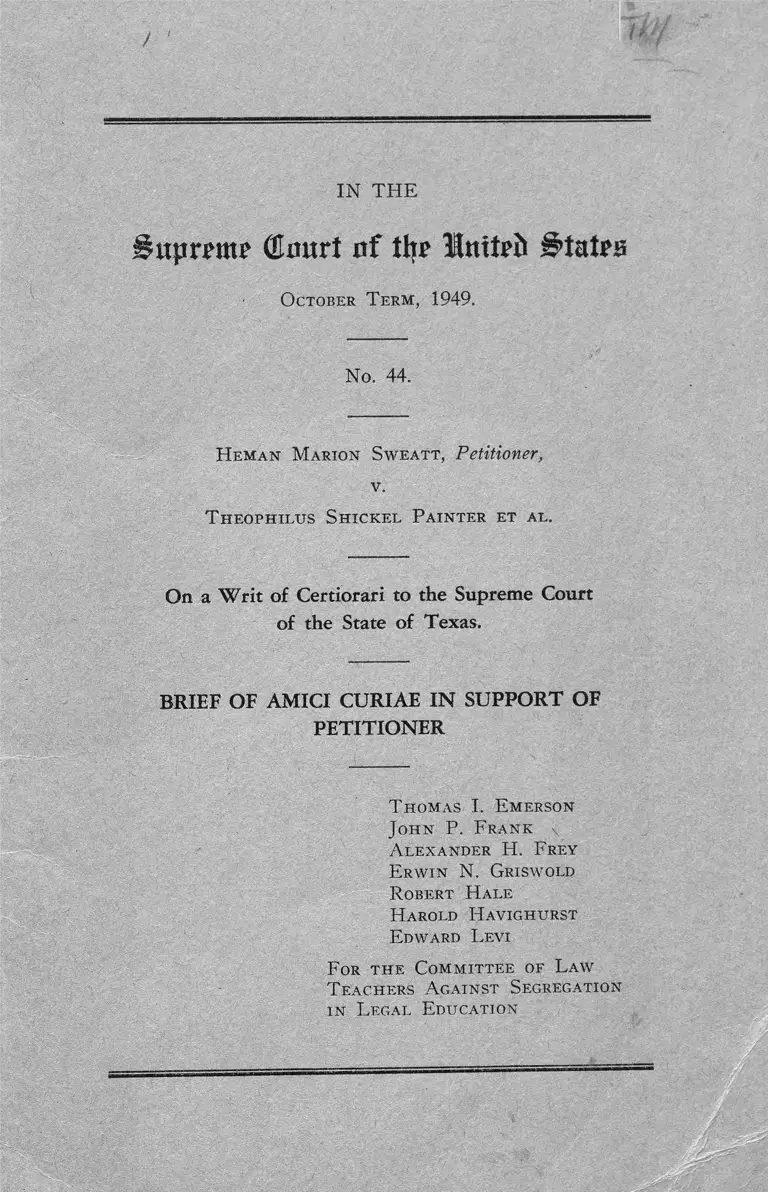

Sweatt v. Painter Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Petitioner

Public Court Documents

January 31, 1950

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Sweatt v. Painter Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Petitioner, 1950. 3b8fbfb5-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/159acebe-711e-4b44-9b95-1f6c3adc4465/sweatt-v-painter-brief-amici-curiae-in-support-of-petitioner. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Copied!

I

IN TH E

upmtt? (Eourt nf tl|p Umtpfc States

O ctober T erm , 1949.

No. 44.

H em an M arion Sw e a tt , Petitioner,

v.

T heophilu s S h ick el P ain ter et a l .

On a W rit of Certiorari to the Supreme Court

of the State of Texas.

BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF

PETITIONER

T homas I. E merson

John P. F ran k v

A lexander H. F rey

E rw in N. Griswold

R obert H ale

H arold H avighurst

E dward L evi

F or t h e Comm ittee of L aw

T eachers A gainst Segregation

in L egal E ducation

IN DEX

Statement ............................ ....................................-............................ 1

Summary of Argument........................................................................ 3

Argument

I. The Equal Protection Clause Was Intended to Outlaw

Segregation ............— .............................. ...................... ...... 4

1. The original meaning of equal protection is incom

patible with segregated education...................... -........ 5

3. Contemporary rejection of “ separate but equal” in

Congress, immediately before and after the Four

teenth Amendment, represents a judgment incom

patible with segregated education...................... ......... 11

3. In Railroad Co. v. Brown, this Court early decided

that “ separate” could not be “ equal” .................... ......... 18

4. Plessy v. Ferguson, which undid the Brown case and

the legislative history of equal protection, should be

overruled ................:............................................. - .......... 30

II. The Basic Policies Underlying the Court’s Approval of

Segregation in Plessy v. Ferguson Have, in the Years

Intervening Since That Decision, Proved to Be Not

Only Wholly Erroneous But Seriously Destructive of

the Democratic Process in the United States.................. 33

1. The judgment of the Court in Plessy v. Ferguson

that direct governmental action to eliminate segre

gation is ineffective to overcome the prevailing cus

toms of the community has proved to be without

foundation .............................................................. -........ 33

3. Patterns of segregation have not tended to produce

harmonious relations between races, as the Court

assumed in Plessy v. Ferguson, but have increased

tensions and become progressively destructive of the

democratic process in the United States................ ...... 39

3. This Court has ultimate responsibility, under the

Constitution, to review the factual and policy judg

ment of the Texas legislature in this situation.......... 33

III. Segregation Should Not Be Extended to Education.......... 34

1. The precedents do not uphold segregated education 34

3. Under the rule of reason created by the precedents,

segregation is unreasonable........................................... 35

IV. Equal Facilities for Legal Education Have Not in Fact

Been Offered to Sweatt and, Indeed, Segregated Legal

Education Cannot Under Any Circumstances Afford

Equal Facilities. Hence Petitioner Has Been Denied

Equal Protection Even Within the Broadest Application

of Plessy v. Ferguson......................................................... 38

Conclusion ........................ 47

Appendix A ........................ .....................................-............................. 49

Page

Index Continuedii

CITATIONS

Page

Cases :

Baylies v. Curry, 128 111. 287, 21 N. E. 595 (1889).................... 19

Berea College v. Kentucky, 211 U. S. 45 (1908).—.............. .— 34

Buchanan v. Worley, 245 U. S. 60 (1917)........ .......................... 34

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 542 (1883).......................... ........... 4

Cumming v. Richmond County Bd., 175 U. S. 528 (1899)... 34, 35

Ex parte Garland, 4 Wall. 333 (1867)........................................... 14

Ex parte McCardle, 7 Wall. 506 (1869)............................ .......... 14

Fisher v. Hurst, 333 U. S. 147 (1948)...................................... 35, 39

Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U. S. 78 (1927)...... ........................... .34, 35

Henderson v. United States, (No. 25, Oct. Term, United States

Supreme Court).................. ......................._................................ 31

Jones v. Kehrlein, 47 Cal. App. 646, 194 P. 55 (1920).............. 19

McCabe v. Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe, 235 U. S. 151 (1914) 40

McPherson v. Blacker, 146 U. S. 1 (1892).................................. 16

Missouri ex rel, Gaiines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 (1938) 35, 39, 40

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373 (1946)........:.......................... 25

New York Trust Co. v. Eisner, 256 U. S. 345 (1921)................ 23

Perez v. Sharpe, 32 Cal. 2d 711, 198 P. 2d 17 (1948)................ 40

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 (1896)................3, 4, 14, 20-4,

25, 29-30, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 38, 39

Railroad Co. v. Broim, 17 Wall. 445 (1873).... ........... 3, 18-20, 22

Roberts v. City of Boston, 5 Cush. (Mass.) 198 (1849)... 5, 14, 15

Sipuel v. Bd. of Regents, 332 U. S. 631, sub nom. Fisher v.

Hurst, 333 U. S. 147 (1948)...................................................35, 39

Slaughter-House Cases, 16 Wall. 36 (1873)............................. . 14

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649 (1944).................................... 24

State v. McCann, 21 Ohio St. 198 (1872).............. .................... 15

United States v. Carotene Products, 304 U. S. 144 (1938)...... 33

United States v. Harris, 106 U. S. 629 (1883)............................ 4

West Virginia State Bd. v. Barnett, 319 U.S. 624 (1943)....... 33

Statutes :

Civil Rights Act of 1866, 14 Stat. 27 (1866)............................. 8

Civil Rights Act of 1875, 1.8 Stat. 335 (1875)............................. 14

12 Stat. 805 (1863)....................................................................... 11, 18

13 Stat. 537 (1865)......................................................................... 11

16 Stat. 3 (1869)................... .......................................................... 13

Mass. Acts 1845, c. 214............. .......................... ........................... 5

Mass. Acts 1855, c. 256.................................. .................................. 7

Rule 1, Texas Rules of Civil Procedure (Vernon 1942).......... 46

Rules of State Bar of Texas, Art. 3, § 1, 1 Tex. Stat. 696

(Vernon 1947)............................ ........................................ ....... 46

Index Continued iii

M iscellaneous :

Page

Exec. Order 9981, Fed. Reg. 4313 (1948).................................. 27

103 A. L. R. 713............................... .....- ......................................... 40

American Civil Liberties Union, 29th Annual Rep., In The

Shadow of Fear (1949)............................... ............................. 29

American Freeman, The (1866)........................ ......................... 13

Association of American Law Schools, Teachers’ Directory

(1949-50) .............................. ..........................-........................... 41

Cong. Globe, 38th Cong., 1st Sess. (1864).......................... 7, 11, 12

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. (1865-6)............7, 8, 9, 10, 11

Cong. Globe, 40th Cong., 2d Sess. (1867).................................. 13

Cong. Globe, 41st Cong., 2d Sess. (1870).................................. 13

Cong. Globe, 41st Cong., 3d Sess. (1871)................................ 14, 15

Cong. Globe, 42d Cong., 1st Sess. (1871).................................. 15

Cong. Globe, 42d Cong., 2d Sess. (1871-2)..................... 14, 15, 17

2 Cong. Rec., 43d Cong., 1st Sess. (1874)....................... 15, 16, 22

3 Cong. Rec., 43d Cong., 2d Sess. (1875).................................. 17

Garrison, Address, 8 Am. Law School Rev. 592 (1936)............ 45

Letter of Salmon Chase to Charles Sumner, dated Dec. 14,

1949 ......................................... ..... ....... ......................................... 6

Letter of Senator Morrill to Charles Sumner, undated (prob.

Oct. or Nov. 1865)..................................................................... 8

Letter to Thaddeus Stevens, dated Nov. 1, 1865........................ 7

Massachusetts Const. Art. I l l (1780)........................................... 9

Maine Const. Art. I, § 3 (1819)........................... ........................ 9

New Hampshire Const. Art. V I (1792)....................................... 9

New York State Comm’n Against Discrimination, 1948 Report

of Progress...................................................................................... 28

President’s Commission of Higher Education, Higher Educa

tion for American Democracy (1947)..................................... 37

Report of President’s Committee on Civil Rights, To Secure

These Rights (1947)........................ ...........................25, 26, 27, 35

Resolution of Providence, R. I., Union League Club (1865) 7

Sen. Rep. No. 131, 40th Cong., 2d Sess. (1868)............. ........... 19

Special Report, Commissioner of Education on Condition and

Improvement of Public Schools, Dist. Col., H. R. Exec.

Doc. No. 315, 41st Cong., 2d Sess. (1870)... ....................... . 12

United States Fair Employment Practice Committee, Final

Report (1946)........ 27

University of Texas, Law School, Catalogue (Aug. 1, 1948) 42

University of Texas for Negroes, School of Law, Bulletin

(1949-50) ....................................................................... 2, 41, 42, 44

T reatises ani> A rticles:

Abrams, Race Bias in Housing (1947)......................................... 26

Abrams, The Segregation Threat in Housing, 7 Commentary

123 (1949)..... .......................... ...................... ........... .................. 26

IV Index Continued

American Council on Education, Thus Be Their Destiny

(1941) ............................... 31

American Council on Education, Color, Class and Personality

(1942) ............................................................................................ 31

American Management Association, The Negro Worker

(1942) .................................................................. 28

Article, U T Institutes Placement Service, 12 Texas Bar Jour

nal 208 (1949).......................................................................................................... 43

Beard, The Rise of American Civilization (1935).................... 10

Bellson, Labor Gains on the Coast, 17 Opportunity 9 (1939) 29

Benedict, Transmitting Our Democratic Heritage in the

Schools, 48 Am. Jour. Sociol. 722 (1943)............................ 36, 37

Boutwell, Reminiscences of Sixty Years (1902)........................ 10

Boyd, Some Phases of Educational History in the South Since

1865, Studies in So. Hist. 259 (1914)..................................... 13

Boyer, The Smaller Law Schools, 9 Am. Law School Rev.

1469 (1942)........................ 42

Bowen, Divine White Right (1934)............................................... 31

Brubacher, Modern Philosophies of Education (1939)............ 37

Comment, 56 Yale L. J. 837 (1947)............................................. 28

Commission on Discrimination in Employment, New York

State War Council, Breaking Down the Color Line, 32 Man

agement Rev. 174 (1943)........................................................... 28

Curry, Brief Sketch of George Peabody (1898)........................ 17

Curti, The Social Ideas of American Educators (1935)........36, 37

Dewey, Democracy and Education (1916).................................. 37

Flack, The Fourteenth Amendment (1908)................................ 10

Fleming, Documentary History of Reconstruction (1906) 7, 12, 17

Frasier and Armentrout, An Introduction to Education (3d

ed. 1933)................................................................................. 37

Gifford, The Placement of Law Students and Law Graduates,

9 Am. Law School Rev. 1063 (1941).......................................... 43

Gillmor, Can the Negro Hold His Job?, National Association

for Advancement of Colored People Bull. (Sept. 1944)..... 28-9

Grosvenor, 24 New Englander 268 (1865)................................ 7

Horne and Robinson, Adult Educational Programs in Housing

Projects with Negro Tenants, 14 J. Negro Educ. 353 (1945) 26

Jackson, The Product of Our Present-Day Law Schools, 9

Am Law School Rev. 370 (1939).......................................... 41, 46

James, The Framing of the Fourteenth Amendment (1939)... 7

Kallen, The Education of Free Men (1949)............................ 37, 38

Key, Southern Politics (1949)....................................................... 24

Kilpatrick (E d.), The Educational Frontier (1933).................. 37

Knight, The Influence of Reconstruction on Education in the

South (1913).................................................................................. 12

Lewin, Resolving Social Conflicts (1948).................................. 37

Maclver, The More Perfect Union (1948).............................. 32, 38

McPherson, Handbook of Politics for 1868 (1868).................. 7

Page

Index Continued v

Page

Manning and Phillips, Negroes as Neighbors, 13 Common

Sense 134 (1944)...... .......................-............. ....-...........-........... 26

Mayo, The Human Problems of an Industrial Civilization

(1933) ................ ...........................- .................- .......— .............. 37

Merriam, The Making of Citizens (1931)......._ -............... 36

Miller, Thaddeus Stevens (1939) ............................. ~~.............. 10

Morrison and Commager, The Growth of the American Re

public (1942).................... ........................- ..........- ....—............... 10

Moylan, Selected List of Books for the Small Law School

Library, 9 Am. Law School Rev. 469 (1939)................ ........ 42

Murray (E d.), The Negro Handbook (1949)............. .............. 25

Myers and Williams, Education in a Democracy (1942).............. 36

Myrdal, An American Dilemma (1944)........................ -............. 31

Nason, Life of Henry Wilson (1876)......................................... 5

Newlon, Education for Democracy in Our Time (1939).......... 38

Newman, An Experiment in Industrial Democracy, 22 Oppor

tunity 52 (1944)._................................... -.................................... 28

Northrup, Proving Ground for Fair Employment, 4 Commen

tary 552 (1947)..........................................................-................ 28

Note, 49 Col. L. Rev. 629 (1949)....................... - ....................... 31

Note, 56 Yale L. J. 1059 (1947)...............................................30, 31

Note, 58 Yale L. J. 472 (1949)........................ - .......................... 31

Ottley, The Good-Neighbor Policy— At Home, 2 Common

Ground 51 (1942)........................................................................ 26

Patterson, The Legal Aid Clinic, 21 Tex. L. Rev. 423 (1943) 44

Pound, Social Control Through Law (1942).............................. 46

Ross, They Did It in St. Louis, 4 Commentary 9 (1947)....... 29

Ross, Tolerance by Law, 195 Harper’s Mag. 458 (1947).......... 28

Rostow, Liberal Education and the L aw : Preparing Lawyers

for Their W ork in Our Society, 35 A. B. A. Jour. 626

(1949) ........................ ..................-................................................4:4-5

Simon, Causes and Cure of Discrimination, N. Y . Times, May

29, 1949, § 6, p. 10.................... .............................. .................... 28

Sumner, Works (1874).................................. .............. ......- .......... 6, 8

Sweetland, The CIO and Negro American, 20 Opportunity 292

(1942) .........................-...................... - ................ ............. ........r 29

Taylor, Negro Teachers in White Colleges, 65 Sch’l and Soci

ety 369 (1947)......................... ...................................................... 26

Warren, The Supreme Court in U. S. History (1926)------- ........ 21

Westermann, Between Slavery and Freedom, 50 Am. Hist.

Rev. 213 (1945)------------- ----------- ------------ ------------ ------------ - ----------- 4

Williams, The Louisiana Unification Movement in 1873, 2 J.

So. Hist. 349 (1945).................................................................. 12

Wirth, Segregation, 13 Encyc. Soc. Sci. 643 (1934)................ 31

IN TH E

i^uprme (Enurt af tl|? Imtpb States

O ctober T erm , 1949.

No. 44.

H em an M arion Sw e att , Petitioner,

v.

T heophilu s S h ick el P ainter et a l .

On a W rit of Certiorari to the Supreme Court

of the State of Texas.

BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF

PETITIONER

STATEMENT

This is a brief o f amici curiae in support of petitioner on a

writ of certiorari to review the judgment of the Texas Court of

Civil Appeals (R . 465) affirming a judgment of the District

Court of Travis County denying petitioner’s request for a writ

of mandamus (R . 438-41). Review was denied by the Texas

Supreme Court (R . 466). Certiorari was granted by this Court

on Nov. 7, 1949. The jurisdictional details are contained in

petitioner’s brief, and the procedural history of the case appears

at R. 438-72.

This brief is filed, with the consent of the parties, on behalf

of the Committee of Law Teachers Against Segregation in Legal

2

Education, an organization identified more fully in Appendix A

to this brief.

The essential facts are as follows:

The courts below have denied petitioner’s application for a

writ of mandamus to compel the appropriate officials o f the Uni

versity of Texas to admit him to its law school in Austin, Texas.

He is concededly in all respects qualified for admission to that

school except for the disqualification of race, for Texas bars

Negroes from this University (R . 425, 445). The courts below

have rejected petitioner’s contention that this exclusion and peti

tioner’s consequent relegation to a state “ colored law school” vio

late his rights under the Fourteenth Amendment.

At the time the record below was made, the colored school was

located in Austin, Texas. It has since been moved to Houston

(see R. 51-2; Bulletin of the Texas State University for Negroes,

School of Law 5 (1949-50)). Petitioner contends that, for the

decision of the issues on which he petitions, the location is im

material except in one important respect: The use of the Univer

sity o f Texas (white) faculty members was contemplated while

the school was in Austin (R . 454), but a separate faculty is to

be recruited for Houston (R . 28-9; see Bulletin, supra, at p. 4 ).

The Texas law school (colored) was set up in response to the

order of the district court at an earlier stage of this same litiga

tion (R . 424-33), and it does not appear in the record that there

have ever actually been any students in it (though doubtless

there are some), either in Austin or in Houston. Sweatt was the

first Negro to apply for admission to the Texas law school (white)

(R . 451), and in any case Texas concedes that the colored school

will have very few students (R . 77).

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The basic position of this brief is that segregated legal educa

tion in the state institutions of Texas violates the equal protection

clause o f the Fourteenth Amendment. That position is ap

proached by three different paths.

3

First, analysis of the origins of “ equal protection” in American

law shows that, in the form of “ equality before the law,” it was

transferred to this country from the French by Charles Sumner as

part of his attack on segregated education in Massachusetts a decade

before the Civil War, and linked by him with the Declaration of

Independence. Popularized by Sumner, it or like phrases became

the slogan of the abolitionists, and it passed into the Constitution

as an important part of the abolitionists’ share o f the Civil War

victory. Congress, contemporaneously with the adoption of the

Fourteenth Amendment, clearly understood that segregation was

incompatible with equality, a judgment reflected by this Court in

Railroad Co. v. Brown, 17 Wall. 445 (1873).

In Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896), this Court aban

doned the original conception of equal protection, adopting instead

the legal fiction that segregation (in that case, in transportation)

is not discriminatory. This was a product, in part at least, of a

policy judgment that the judiciary was incapable of enforcing the

Amendment as it was written, and that the underlying social evil

must be left to the correction of time. The Court erred on both

counts: the judiciary is not so powerless as it supposed, and the

results o f its abdication have been disastrous. The dissenting

views of Mr. Justice Harlan in the Plessy case were correct, and

should be adopted now.

Second, we challenge the applicability to education of the

“ separate but equal” refinement of the equal protection clause.

While we grant the existence of troublesome dicta, there is neither

a holding nor even carefully considered dicta by this Court declar

ing that segregation may be enforced in any phase of education.

In Plessy v. Ferguson the Court did not say that segregation was

valid in every context in which men could devise ways o f separat-

ting themselves by color. On the contrary, it made careful dis

tinction between reasonable and unreasonable segregation. We

contend that segregation in education is for this purpose unrea

sonable.

Third, even within the broadest application of Plessy v. Fer

guson, petitioner is entitled to absolute equality in education.

4

For reasons set forth in detail in the body of the brief, it is im

possible for petitioner to receive at the improvised colored law

school a legal education equal to that offered at the well-known

University of Texas law school (white). Nor, indeed, can segre

gated legal education ever afford equal facilities.

ARGUMENT

I.

THE EQUAL PROTECTION CLAUSE W A S IN

TENDED TO O U TLAW SEGREGATION.

The Court below held (a ) that segregated legal education can

meet the constitutional standard, and (b ) that Texas (colored)

in fact did so. W e challenge at the outset the entire basis of

any decision which assumes that segregation can meet the stand

ard of the Constitution. The Negro for whom the first section of

the Fourteenth Amendment was primarily adopted was largely

read out o f that Amendment by nineteenth century decisions.1

The time has come to reconsider the frustration of so much of

section one of the Amendment as relates to the equal protection

of the laws.

Society in the past has known intermediate stages of bondage

between the free and the slave. In antiquity, “ between men of

these extremes of status stood social classes which lived outside

the boundary of slavery but not yet within the circle of those

who might rightly be called free.” 2 The Thirteenth Amendment

took the Negroes out of the class of slaves. Section one of the

1While decisions outside the area of segregation are not directly

involved in this case, the leading segregation decision of Plessy v.

Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896), can be understood only as part of

a group of decisions in the latter part of the nineteenth century

narrowly construing the capacity of the Fourteenth Amendment to

protect Negro rights. Other decisions include the Civil Rights Cases,

109 U.S. 542 (1883), and United States v. Harris, 106 U.S. 629

(1883).

2Westermann, Between Slavery and Freedom, 50 Am. Hist. Rev.

213, 214 (1945).

5

Fourteenth Amendment was intended to insure that they not be

dropped at some half-way house on the road to freedom. It sought

to bring the ex-slaves within the circle of the truly free by obliter

ating legal distinctions based on race.

The evidence of intent to eliminate race distinctions in trans

portation and education, relationships which must be considered

together in the history of equal protection, is particularly clear.

Equal protection first entered American law in a controversy over

segregated education.

I. The original meaning of equal protection is incompatible

with segregated education.

It was one thing, and a very important one, to declare as a

political abstraction that “ all men are created equal,” and quite

another to attach concrete rights to this state of equality. The

Declaration o f Independence did the former. The latter was

Charles Sumner’s outstanding contribution to American law.

The great abstraction of the Declaration o f Independence was

the central rallying point for the anti-slavery movement. When

slavery was the evil to be attacked, no more was needed. But

as some of the New England States became progressively more

committed to abolition, the focus o f interest shifted from slavery

itself to the status and rights of the free Negro. In the Massa

chusetts legislature in the 1840’s, Henry Wilson, wealthy manu

facturer, abolitionist, and later United States Senator and Vice

President, led the fight against discrimination, with “ equality”

as his rallying cry.3 One Wilson measure gave the right to recover

damages to any person “ unlawfully excluded” from the Massa

chusetts public schools.4

Boston thereupon established a segregated school for Negro

children the legality of which was challenged in Roberts v. City

of Boston, 5 Cush. (Mass.) 198 (1849). Counsel for Roberts

8For an account of Wilson’s struggles against anti-miscegenation

laws, against separate transportation for Negroes, and for Negro

education, see Nason, Life of Henry Wilson, 48 et seq. (1876).

4Mass. Acts 1845, c. 214.

6

was Charles Sumner, scholar and lawyer, whose resultant oral

argument was widely distributed among abolitionists as a pamph

let.5 Sumner contended that separate schools violated the Massa

chusetts state constitutional provision that “ All men are created

free and equal.” 6 He conceded that this phrase, like its counter

part in the Declaration of Independence, did not by itself amount

to a legal formula which could decide concrete cases. Nonethe

less it was a time-honored phrase for a time-honored idea and, in

a broad historical argument, he traced the theory of equality from

Herodotus, Seneca and Milton to Diderot and Rousseau, philos

ophers of eighteenth century France.

A t this point Sumner made his m ajor contribution to the theory

of equality. He noted that the French Revolutionary Constitu

tion of 1791 had passed beyond Diderot and Rousseau to a new

phrase: “ Men are born and continue free and equal in their

rights.” Using a popular French phrase in English for the first

time, Sumner referred to “ egalite devant la loi,” or equality before

the law. The conception of equality before the law, or equality

“ in their rights,” was a vast step forward, for this was the first

occasion on which equality of rights had been made a legal con

sequence of “ created equal.”

Equality before the law, or equality of rights, Sumner insisted,

was the basic meaning of the Massachusetts constitutional pro

vision. Before it “ all . . . distinctions disappear.” Man,

equal before the law, “ is not poor, weak, humble, or black; nor

is he Caucasian, Jew, Indian, or Ethiopian; nor is he French,

German, English, or Irish; he is a M A N , the equal of all his

fellow men.” 7 Separate schools were unconstitutional because

they made a distinction where there could be no distinction, at

the point of race, and therefore separate schools violated the prin

ciple of equality before the law.

5Among those active in distributing the pamphlet was Salmon P.

Chase of Ohio. Diary and Correspondence of Salmon P. Chase,

Chase to Sumner, Dec. 14, 1849, in 2 Ann. Rep. Am. Hist. Ass’n.

188 (1902).

6The following summary of argument is taken from the complete

argument reprinted in 2 Sumner, Works 327 et seq. (1874).

7Ibid.

7

The Massachusetts court, unpersuaded, rejected Sumner’s argu

ment, and was in turn reversed by the state legislature.8 But the

argument outlasted the case, and from it the phrase “ equality

before the law,” or its briefer counterpart, “ equal rights,” became

the measuring stick for all proposals concerning freedmen.

Prior to the Civil War, the controversy over equality for the

freedmen was primarily a dispute within the States, but national

emancipation brought the issue to Congress where Sumner kept

“ equality” in the forefront of Congressional attention.9 Shortly

before the first meeting of the 39th Congress in December, 1865,

the new Black Codes in the Southern States had shocked the

North into widespread recognition of the need to secure equality.10

Sumner’s popularization of his equality theory had been so suc

cessful that its echo returned from Radicals everywhere.11 Rep

resentative Bingham of Ohio offered a proposed Fourteenth

Amendment in which the key phrase was a guarantee to the people

of “ equal protection in their rights, life, liberty, and property.” 12

Senator Morrill of Vermont, shortly to be a member of the

Joint Committee on Reconstruction, sent a note to Sumner sug

gesting that the best “ jural phrase” for an amendment would

be a guarantee that citizens are “ equal in their civil rights, im

munities and privileges and equally entitled to protection in life,

8Mass Acts 1855, c. 356.

9See, e.g., his discussion in the Senate of the possible wisdom of

including “ equality” in the Thirteenth Amendment. Cong. Globe,

38th Cong., 1st Sess. 1483 (1864).

10Handy compilations of these Codes are McPherson, Handbook of

Politics for 1868, 39-44 (1868) ; 1 Fleming, Documentary History of

Reconstruction c. 4 (1906).

“ “ Equality before the law” was the general cry. A Pennsylvania

State Equal Rights League signed its correspondence “ Yours for

justice and equality before the law.” Letter to Stevens of Nov. 1,

1865, Stevens Mss. (1865), Lib. Cong. And see resolution of Provi

dence, R. I., Union League Club, ibid, asking “ our members in

Congress” to secure “ equal rights of all men before the law.” “ Ab

solute equality before the law” was demanded in Grosvenor, 34 New

Englander 368 (1865). See also James, The Framing of the Four

teenth Amendment 39 et seq. (1939), an unpublished Ph.D. thesis

in the library of the University of Illinois. On the relative amount

of attention given the first, as compared to the other sections of the

Amendment, see note 33 infra.

12Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 14 (1865).

8

liberty and property.” 13 Sumner himself introduced a reconstruc

tion plan, an important part o f which included “ equal protection

and equal rights.” 14

The first relevant measure actually to be considered by Con

gress was the bill which became the Civil Rights Act of 1866.

This bill was originally introduced by Senator W ilson of Massa

chusetts, the same W ilson who had been so active earlier in the

equality struggles in that state,15 and we may assume that the

proposal represented the joint policies o f W ilson and Sumner.16

The W ilson proposal invalidated all laws “ whereby or wherein

any inequality o f civil rights and immunities” existed because of

“ distinctions or differences of color, race or descent.” This meas

ure, as it passed the Senate, contained a clause forbidding any

“ distinction of color or race” in the enforcement of certain laws,

and assured “ full and equal benefit of all laws” relating to person

and property. Senator Howard, a member o f the Joint Com

mittee on Reconstruction, said of the Act, “ In respect to all civil

rights, there is to be hereafter no distinction between the white

race and the black race.” 17

The Civil Rights bill was enacted, but over the protest o f one

extreme radical in the House. Representative Bingham o f Ohio

opposed the measure on the ground that the Thirteenth Amend

ment gave it an inadequate base. He preferred to wait until

13Morrill to Sumner, undated, prob. Oct. or Nov., 1865, in Sumner

Mss., quoted in James, supra note 11 at 31.

1410 Sumner, Works 22 (1874).

15Though the measure was introduced by Wilson, actual leadership

on the proposal passed from him to Senator Trumbull of Illinois,

chairman of the Judiciary Committee. The proposal originated with

S.9 in the 39th Cong., introduced by Wilson, from which the text

quotations are taken. A few days later, after floor discussion which

revealed that Trumbull was willing to take the lead on the measure,

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 43 (1865), Wilson introduced a

new bill, S. 55, which retained and enlarged the language of S. 9.

This bill was referred to by Trumbull’s name but retained Wilson’s

proposals. S. 61 became the Civil Rights Act of 1866. 14 Stat. 27

(1866).

16Wilson hinted as much. Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 39

(1865).

17/d. at 504.

9

a new Amendment might pass which would eliminate all “ dis

crimination between citizens on account of race or color.” 18 As

a member of the Joint Committee on Reconstruction, Bingham

was then working on just such an Amendment. With fellow

Committee members such as those extreme equalitarians Stevens,

Howard, and Morrill, there was no serious obstacle in Committee.

Bingham drafted for the Committee the essential language of

section one o f the Fourteenth Amendment. In the vital equality

clause he combined the language of his own earlier proposed

amendment, “ equal protection in their rights” and the Civil Rights

bill language, “ equal benefit of all laws” into the concise “ equal

protection of the laws.” 19 20 The prompt adoption o f the Amend

ment carried the abolitionist theory of racial equality into our

basic document.29 As Senator Howard, floor leader for the

Amendment in the Senate, said of the clause, it “ abolishes all class

legislation in the States and does away with the injustice of sub

jecting one caste of persons to a code not applicable to another.”

The core o f the clause he reduced to Sumner’s meaning: “ It

establishes equality before the law . . . .” 21

18Id. at 1290, 1293.

19The greatest contribution of the Bingham draft of the clause

was not in the words he used, but in those he omitted. Previous

proposals had sometimes carried words of qualification as to the par

ticular types of laws as to which equal protection was to be afforded.

The Civil Rights bill in the Senate had referred to “ equal benefits

of all laws and proceedings for the security of person and estate,” and

had referred to “ discrimination in civil rights and immunities.”

Bingham saw hopeless confusion in these refinements, see remarks

cited, supra note 18, and omitted them. He thus brought the language

squarely into accord with the broad “ equality before the law.”

20W e do not, in tracing this history o f the phrase “ equal protec

tion,” overlook sporadic earlier uses of similar language. See, e.g.,

Mass. Const. Art. I l l (1780); N. H. Const. Art. V I (1792); and

Me. Const. Art. I, § 3 (1819). The context of those Articles, deal

ing with freedom of religion, are so alien to the subject at hand that

they were never referred to in connection with the Fourteenth Amend

ment.

21Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 2766 (1866). Some o f the

broad expressions contemporaneously used, as in the text above, must

be read in the light of the fact that it was racial distinctions which

were being discussed. Howard, for example, meant not that the

Amendment obliterated all classifications in the law, but that it

obliterated race as a basis of classification.

10

Because the primary concern of those who enacted the Four

teenth Amendment was with sections two and three of the Amend

ment, rather than section one which includes equal protection,

we do not have complete evidence o f the views of all the respon

sible men of the time on the meaning o f equal protection.22 W e

do know that the clause found its way into the Constitution

through Sumner, through Wilson, through Trumbull and through

the twelve majority members of the Joint Committee on Recon

struction. Of those fifteen at least eight— Sumner, Wilson, Bing

ham, Howard, Stevens, Conkling, Boutwell, and Morrill— thought

the clause precluded any distinctions based on color.23 Three—

Trumbull, Fessenden, and Grimes— had some mental reservations,

particularly as to miscegenation, although they agreed generally

22Much of the murkiness in the history of “ privileges and im

munities,” “person,” and “ due process,” as well as equal protection,

is produced by the fact that what has become the only significant part

of the Amendment was then the least significant part. The Repub

lican Party represented a coalescence of certain economic and political

interests, along with the abolitionists. Standard references on the

subject are 2 Beard, The Rise of American Civilisation c. 23 (1935),

and 2 Morrison and Commager, The Growth of the American Re

public c. 1 (1942). The best telling of the manner in which these

factions sought to solve their problems by the Fourteenth Amend

ment is Flack, The Fourteenth Amendment (1908). The short of

it is that the politicians and the economic interests they represented

got the middle sections of the Amendment, while section one was the

abolitionists’ share of the victory.

23The views of Sumner, Wilson, and Howard are apparent from

various quotations throughout this brief. Stevens was, if anything,

a more extreme equalitarian than the other two. See Miller, Thad-

deus Stevens 9-13, 404, 405 (1939) ; and see Cong. Globe, 39th Cong.,

1st Sess. 1063, 1064 (1866). The views of Conkling, Morrill, and

Boutwell are apparent from their consistent support of the Sumner

civil rights bill, discussed in detail, infra. The case as to Bingham

is less dear, since his pre-occupation in the Amendment was largely

with the privileges and immunities clause, his special contribution.

Cf. 2 Boutwell, Reminiscences of Sixty Years 41 (1902). However,

his view was apparently in accord with the others of this group, as

evidenced at least by some phrases. See, e.g., Cong. Globe, 39th

Cong., 1st Sess. 1293 (1866).

11

with the others.24 The positions of the remainder we do not know,

though some, at least, doubtless agreed with Sumner.25 It was

thus the dominant opinion of the Committee that the clause

eliminated distinctions of color in civil rights.

2. Contemporary rejection of "separate but equal” in Con

gress, immediately before and after the Fourteenth

Amendment, represents a judgment incompatible with

segregated education.

Congress repeatedly considered “ separate but equal” in the Re

construction decade, particularly in connection with transporta

tion. Railroad and street car companies in the District of Colum

bia early began to separate white and colored passengers, put

ting them in separate cars or in separate parts of the same car,

with quick Congressional response. As early as 1863, Congress

amended the charter of the Alexandria and Washington Railroad

to provide that “ No person shall be excluded from the cars on

account of color.” 26 When, in 1864, the Washington and George

town street car company attempted to handle its colored passen

gers by putting them in separate cars, Sumner denounced the

practice in the Senate and set forth on a crusade to eliminate

street car segregation in the District.27 After a series o f skir

mishes, he finally carried to passage a law applicable to all District

carriers that “ no person shall be excluded from any car on account

of color.” 28

24Fessenden and Trumbull believed that the Civil Rights Act and

the Amendment did not affect anti-miscegenation legislation. Cong.

Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 505 (1866) (Fessenden) ; id. at 323

(Trumbull). In 1864 Grimes thought segregated transportation was

equal. Cong. Globe, 38th Cong., 1st Sess. 3133 (1864), with Trumbull

apparently contra on that issue, id. at 3132. Whether the views of

Grimes changed is not known.

25These four members, Harris, Williams, Blow, and Washburne,

were conventional radicals and Harris, Blow, and Washburne had

very strong anti-slavery backgrounds. It is therefore highly probable

that at least some of them shared the views of Sumner and Stevens,

but we have no direct evidence.

2612 Stat. 805 (1863).

27Cong. Globe, 38th Cong., 1st Sess. 553, 817 (1864).

2813 Stat. 537 (1865).

12

The discussion of the street car bills, all shortly prior to the

Fourteenth Amendment, canvassed the whole issue of segregation

in transportation. Those who supported the measures did so on

grounds o f equality. Senator Wilson denounced the “ Jim Crow

car,” declaring it to be “ in defiance of decency.” 29 * Sumner per

suaded his brethren to accept the Massachusetts view, saying that

there “ the rights of every colored person are placed on an equality

with those of white persons. They have the same right with white

persons to ride in every public conveyance in the common

wealth.” 80 Thus when Congress in 1866 wrote equality into the

Constitution, it did so against a background of repeated judgment

that separate transportation was unequal.31

The history of equal protection and separate schools, though

less clear, suggests a similar interpretation. The close of the War

found public education almost non-existent in the South,32 and

Negro school status in the North ranged from total exclusion from

schools to complete and unsegregated equality.33 Four Southern

Reconstruction constitutions provided for mixed schools, and the

Northern educational aid societies offered unsegregated education

in the South.34 Although these efforts to achieve unsegregated

education were o f little practical effect, they indicate the intel

lectual atmosphere from which equal protection emerged. The

abolitionists were absolutely confident that the races both could

29Cong. Globe, 38th Cong., 1st Sess. 3132, 3133 (1864).

S0Id. at 1158.

31This was clear even from the conservative viewpoint. See re

marks of Senator Reverdy Johnson, id. at 1156.

32One of the many works on the subject is Knight, The Influence

of Reconstruction cm Education in the South (1913).

33An extensive account contemporary with Reconstruction, much

broader in scope than the title indicates, is Spec. Rep., Commissioner

of Education on Condition and Improvement of Public Schools, Dist.

Col., H.R. Exec. Doc. No. 315, 41st Cong., 2d Sess. (1870).

34Materials are collected in 2 Fleming, supra note 10 at 171-212.

Even conservative Southerners, when they sought to give full com

pliance to the Fourteenth Amendment, conceded that equality required

unsegregated education. See Williams, The Louisiana Unification

Movement in 1873, 2 J. South. Hist. 349 (1945), describing the con

cession of mixed schools by a political group headed by Gen. P. T.

Beauregard.

13

and should, under the principle of equality, mingle in the school

rooms.35

The primary responsibility of Congress for education was in

the District of Columbia, where a segregated system was a going

operation prior to the end of the Civil War. Securing a place

on the District of Columbia Committee, Sumner proceeded to

attack discriminations in the District one at a time.36 * Since he

chose first to eliminate restrictions on Negro office-holding and

jury service, he did not reach the school question on his own

agenda until 1870.87 He then twice carried proposals through

the Committee to eliminate the segregation,38 and urged his

proposal on the floor of the Senate on the grounds of equality:

“ Every child, white or black, has a right to be placed under pre

cisely the same influences, with the same teachers, in the same

school room, without any discrimination founded on color.” 39

35The Amendment must be read in the light of this psychology of

optimism. Immediately after the War the abolitionist societies under

took educational work in the South on a large scale, fully recorded in

such of their journals as The American Freeman and the Freeman’s

Journal. The Constitution of the Freeman’s and Union Commission

provided that “ No schools or supply depots shall be maintained from

the benefits of which any person shall be excluded because of color.”

The Am. Freeman 18 (1866). Lyman Abbott, General Secretary of

the Commission, published a statement explaining that the policy had

been fully considered: “ It is inherently right. To exclude a child

from a free school, because he is either white or black, is inherently

wrong . . . . [W e must] lead public sentiment toward its final

goal, equal justice and equal rights . . . . The adoption of the

reverse principle would really lend our influence against the progress

of liberty, equality, and fraternity, henceforth to be the motto of the

republic.” Id. at 6. The fact is that few whites attended these schools.

Boyd, Some Phases of Educational History in the South since 1865,

Studies in Southern History 259 (1914).

36Sumner expounded this seriatim policy in Cong. Globe, 40th

Cong., 2nd Sess. 39 (1867).

S7The jury and office law was twice pocket-vetoed by President

Johnson, and Sumner, therefore, had to secure its passage three times

before it became effective in President Grant’s administration. 16 Stat.

3 (1869).

38S. 361, Cong. Globe, 41st Cong, 2nd Sess. 3273 (1870), and

S. 1244, id, at 1053 et seq.

"Id. at 1055.

14

The most important new voice heard in the District of Colum

bia school debate on Sumner’s proposal was that of Senator Matt

Carpenter of Wisconsin, a leading constitutional lawyer of his

time and prevailing counsel in E x parte Garland, 4 Wall. 333

(1867), E x parte McCardle, 7 Wall. 506 (1869), and the

Slaughter-House Cases, 16 Wall. 36 (1873). Carpenter said:

“ Mr. President, we have said by our constitution, we

have said by our statutes, we have said by our party plat

forms, we have said through the political press, we have

said from every stump in the land, that from this time hence

forth forever, where the American flag floats, there shall be

no distinction o f race or color or on account of previous

condition of servitude, but that all men, without regard to

these distinctions, shall be equal, undistinguished before the

law. Now, Mr. President, that principle covers this whole

case.” 40

Filibuster, not votes, stalled the District of Columbia school

measure.41 Sumner thereupon terminated his efforts to clear up

discriminations one at a time and determined to make one supreme

effort along the entire civil rights front. He put his whole energy

behind a general Civil Rights bill, which forbade segregation

throughout the Union, in the District of Columbia and outside

it, in conveyances, theaters, inns, and schools.42 The consideration

by the Senate of this measure, which in modified form became

the Civil Rights Act of 1875, represents an overwhelming con

temporary judgment that “ separate but equal” schools, wherever

located, violate the equal protection clause.

In the debates on this new civil rights bill, the leading cases

on which this Court relied in Plessy v. Ferguson were pressed

upon the Senate and rejected as unsound. Roberts v. City of

40Cong. Globe, 41st Cong., 3rd Sess. 1056 (1811).

41By 1812, the filibuster had come into frequent use in the defense

against radical legislation. By a vote of 35 to 20 Sumner defeated

those who sought to keep his District school measure off the floor

entirely, Cong. Globe, 42nd Cong., 2d Sess. 3124 (1812), but his time

was used up before he could bring the matter to final vote.

42The measure was proposed by Sumner both as a bill and as an

amendment to other bills over a period of years. Its final presenta

tion was in the 43rd Cong., S. 1.

15

Boston, supra, was quoted without avail.43 A contemporary

Ohio decision, State v. McCann, 21 Ohio St. 198 (1872), w'hich

held that separate schools were adequate, was rejected by name

before these men who knew the Fourteenth Amendment best.44

They made the point over and over again that the Amendment

forbade distinctions because of race. As Senator Edmunds of

Vermont, later chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, put

it when he rejected separate schools : “ This is a matter of inherent

right, unless you adopt the slave doctrine that color and race are

reasons for distinction among citizens.” 45 Sumner himself de

nounced “ separate but equal” in the Senate as he had denounced

it in his oral argument in Roberts v. City of Boston years before:

“ Then comes the other excuse, which finds Equality in

separation. Separate hotels, separate conveyances, separate

theaters, separate schools, separate institutions of learning

and science, separate churches, and separate cemeteries—

these are the artificial substitutes for Equality; and this is

the contrivance by which a transcendent right, involving a

transcendent duty, is evaded.

. . . Assuming what is most absurd to assume, and

what is contradicted by all experience, that a substitute can

be an equivalent, it is so in form only and not in reality.

Every such attempt is an indignity to the colored race, in

stinct with the spirit of slavery, and this decides its char

acter. It is Slavery in its last appearance.” 4e

The bill started its final road to passage in the 43rd Congress.

As Sumner had died, Senator Frelinghuysen o f New Jersey led

the debate for the bill, beginning on April 29, 1874, with an ex

tensive argument that segregation was incompatible with the

Fourteenth Amendment. The bill, he said, sought “ freedom from

all discrimination before the law on account of race, as one of the

43Cong. Globe, 42nd Cong., 2d Sess. 3261 (1872).

44Senator Ferry, opposing the bill, relied on the McCann case. Id. at

3257. At the time of its final consideration, Senator Frelinghuysen,

in charge of the bill in the Senate, explained why he thought the

McCann case should not control. 2 Cong. Rec. 3452, 43rd Cong., 1st

Sess. (1874).

45Cong. Globe, 42nd Cong., 2d Sess. 3260 (1872).

48Cong. Globe, 42nd Cong., 2d Sess. 382, 383 (1871) (emphasis

added).

16

fundamental rights of United States citizenship.” 47 For this he

found full warrant in the equal protection clause. Segregation

in the schools, he said, could only be voluntary, for “ the object of

the bill is to destroy, not to recognize, the distinctions of race.” 48

There were in the Senate three distinct views on the problem

of segregated schools. A minority thought that “ separate but

equal” schools should be permitted. On May 22, 1874, an amend

ment to that effect offered by Senator Sargent o f California was

rejected, 26 to 21. Those 26 included Morrill, Conkling and

Boutwell, who had been on the Committee which had drafted the

Amendment. By voting to reject the “ separate but equal” school

clause, they necessarily indicated a judgment that Congress had

power to legislate against segregated schools under the equal pro

tection clause. This contemporary affirmative and deliberate

interpretation o f the Constitution is entitled to great weight here.

McPherson v. Blacker, 146 U.S. 1, 27 (1892).

The 26 were not themselves of one mind. Senator Boutwell

represented a small minority view that separate schools neces

sarily bred intolerance and therefore should not be allowed to exist

even if both races desired it.49 However, the dominant Senate

opinion was that separate schools should be forbidden by law, as

the Amendment and this bill forbade them; but that if the entire

population were content in particular instances to accept separate

schools, it might do so. Senator Pratt of Indiana, one of the

most vigorous supporters of the bill, noted that Congress was con

tinuing separate schools in the District of Columbia because both

races were content with them; and at the same time he pointed

out that where there were very few colored students, they would

have to be intermingled.50 Senator Howe put it most concretely

when he observed that if, by law, schools were permitted to be

472 Cong. Rec. 3452, 43rd Cong.. 1st Sess. (1874).

48Ibid.

49“ If it were possible, as in the large cities it is possible, to establish

separate schools for black children and for white children, it is in the

highest degree inexpedient to either establish or tolerate such

schools.” From speech of Senator Boutwell, id. at 4116.

50Id. at 4081, 4082.

17

separate, they would never in fact be equal. He believed in pro

hibiting separate schools and then letting people do as they chose:

“ Let the individuals and not the superintendent of schools judge

of the comparative merits of the schools.” 51

The bill passed the Senate, but in the House the result was

different. The bill passed, but with the school clause deleted.

This deletion was the product of many factors. The House

had previously voted to require mixed schools,52 but on this occa

sion it was confronted with the firm opposition of the George

Peabody Fund. Peabody, an American merchant who founded

what became J. P. Morgan & Co., established a fund of $3,000,000

to aid education in the South. As abolitionist education aid

societies ran out o f money and collapsed, the Peabody Fund

became the only major outside agency aiding Southern education.

The Fund opposed mixed schools, withdrawing its aid where they

were required.53 It claimed credit for inducing President Grant

to instruct his House floor leader to abandon the school provi

sion.54 Coupled with this pressure were threats from Southern

representatives that they would end their newly founded public

school systems if the Senate measure passed.55 In addition, some

Representatives felt that the courts would protect the Negroes on

the school issue, and thus as a matter of legislative discretion

waived the right to legislative aid.56 For whatever combination

51Id. at 4151.

52H.R. 1647, Cong. Globe, 42nd Cong., 2d Sess. 2074 (1872),

(House refused, 73 to 99, to lay bill on table) ; id. at 2270, 2271 (en

grossed and read three times, 100 to 78) ; no final action taken.

532 Fleming, supra note 10 at 194. During this period the Fund

was under the direction of Dr. Barnas Sears, later succeeded by J. L.

Curry. Curry, in a volume on the work of the Fund, introduces

the topic of mixed schools with the words, “ Some persons, not to ‘the

manner born’, took the lead in organizing a crusade for the co-educa

tion of the races.” Curry, Brief Sketch of George Peabody 60

(1898).

5iId. at 64, 65.

55See, e.g., discussion of this point by Representative Roberts, who

stated that he preferred to prohibit segregated schools but would vote

to omit the clause for fear the South would abolish all schools.

3 Cong. Rec. 981, 43rd Cong., 2d Sess. (1875).

56See remarks of Representative Monroe, id. at 997, 998.

18

of reasons, a leading Negro Representative from South Carolina

consented to eliminate the school clause in return for assurance

that the rest of the bill would pass.57 58 The House result, clearly,

thus represented a political rather than a constitutional judgment.

In summary, equal protection as a legal conception originated

before the Civil War in Sumner’s attack on segregated schools.

It became the abolitionist rallying cry and was brought into the

Constitution by the abolitionist wing of the Republican Party.

Before the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted, “ equal rights”

was thoroughly understood to mean identical, and not separate

rights, particularly in transportation. That was the view of the

dominant group among those who actually phrased the Fourteenth

Amendment. Throughout the debate on the Amendment its sup

porters acknowledged no doctrine of equal but separate as an

exception to the fundamental concept of equal rights. Contem

porary legislative action confirms this basic position.

3. In Railroad Co. v. Brown, this Court early decided that

"separate” could not be "equal” .

In the leading case o f Railroad Co. v. Brown, 17 Wall. 445

(1873), this Court early decided that separate accommodations,

no matter how identical they might otherwise be, were not equal.

On February 8, 1868, Catherine Brown, colored, attempted to

board a railroad car on a line from Alexandria to Washington.

That road had a “ Sumner amendment” in its charter which pro

vided that “ no person shall be excluded from the cars on account

o f color.” 68 The railroad maintained two identical cars, one next

to the other on the train, using one for white and the other for

colored passengers. When Mrs. Brown attempted to sit in the

“ white” car, she was ejected with great violence.

The pertinent legal issue in Mrs. Brown’s case was whether

segregation amounted to the same thing as “ exclusion from the

cars.” The episode attracted immediate attention because Mrs.

57See remarks id. at 981, 982.

5812 Stat. 805 (1863).

19

Brown was in charge of the ladies’ rest room at the Senate.

A Senate investigating committee concluded that the Company

had violated its charter, and recommended that the charter be

repealed if Mrs. Brown were not fully compensated by civil

damages.59

A t the trial, the Company unsuccessfully asked for a charge

to the jury that separate but equal cars complied with the statute,

and in the Supreme Court it argued that “ making and enforcing

the separation of races in its cars” was “ reasonable and legal.” 60

The Supreme Court unanimously rejected the “ separate but

equal” argument as “ an ingenious attempt to evade a compliance

with the obvious meaning of the requirement.” 61 The object of

the Sumner amendment, said the Court, was not merely to let the

Negroes buy transportation, but to let them do so without “ dis

crimination” :

“ Congress, in the belief that this discrimination was unjust,

acted. It told the company, in substance, that it could

extend its road into the District as desired, but that this

discrimination must cease, and the colored and white race,

in the use of the cars, be placed on an equality. This con

dition it had the right to impose, and in the temper of

Congress at the time, it is manifest the grant could not have

been made without it.” 62

Thus in its first review of “ separate but equal,” this Court held

that segregation was “ discrimination” and not “ equality.” W e

ask the Court to apply that same principle in the instant case.

59Sen. Rep. No. 131, 40th Cong, 2d Sess. (1868).

60The quotation is taken from the brief on file in the Supreme Court

library.

8117 Wall. 445, 452. The same approach as that of the Brown case

is taken whenever a statute which requires “ equal” treatment is held

to forbid segregation. See, e.g., Baylies v. Curry, 128 111. 287, 21

N.E. 595 (1889) (restricting Negroes to particular theater seats held

violation of statute) ; Jones v. Kehrlein, 47 Cal. App. 646, 194 P. 55

(1920) (same).

6217 Wall. 445 at 452, 453 (emphasis added).

20

4. Plessy v. Ferguson, which undid the Brown case and the

legislative history of equal protection, should be over

ruled.

Twenty years after Railroad Co. v. Brown, this Court took

a wholly different view o f segregation.

The exact issue in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896),

was whether a Louisiana requirement of separate railroad ac

commodations denied equal protection. Mr. Justice Brown for

the majority held that this segregation did not stamp “ the colored

race with a badge o f inferiority.” If it did so, said he, “ it is

not by reason of anything found in the act, but solely because

the colored race chooses to put that construction upon it.” 63

Mr. Justice Harlan, dissenting, states our case:

“ It was said in argument that the statute of Louisiana

does not discriminate against either race, but prescribes a

rule applicable alike to white and colored citizens. But this

argument does not meet the difficulty. Everyone knows that

the statute in question had its origin in the purpose, not

so much to exclude white persons from railroad cars occu

pied by blacks, as to exclude colored people from coaches

occupied by or assigned to white persons . . . .

“ The white race deems itself to be the dominant race in

this country. And so it is, in prestige, in achievements, in

education, in wealth and in power. So, I doubt not, it will

continue to be for all time, if it remains true to its great

heritage and holds fast to the principles of constitutional

liberty. But in view of the Constitution, in the eye of the

law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling

class o f citizens. There is no caste here. Our Constitution

is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among

citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal

before the law. The humblest is the peer of the most power

ful. The law regards man as man, and takes no account

of his surroundings or of his color when his civil rights as

guaranteed by the supreme law of the land are involved. It

is, therefore, to be regretted that this high tribunal, the final

expositor o f the fundamental law of the land, has reached

63Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537, 551 (1896).

21

the conclusion that it is competent for a State to regulate

the enjoyment by citizens of their civil rights solely upon

the basis of race.

“ In my opinion, the judgment this day rendered will, in

time, prove to be quite as pernicious as the decision made by

the tribunal in the Dred Scott case.” (163 U.S. at 556-9).

The core o f Mr. Justice Brown’s argument is in his assump

tion that segregation is not a white judgment of colored inferior

ity. This would be so palpably preposterous as a statement of

fact that we must assume Justice Brown intended it as a legal

fiction. The device of holding a despised people separate, whether

by confinement of the Jew to the ghetto, by exclusion o f the

lowest castes in India from the temples, or by the slightly more

refined separate schoolroom, is clearly expression of a judgment

of inferiority.

The real question, therefore, is why should the Court have

adopted this legal fiction? W hy should the Court have thought

it necessary to make a pretense that segregation is anything other

than discrimination?

The Court chose to overthrow the Fourteenth Amendment, not

for caprice, but for reasons of policy.64 The specific policy judg

ments made by the Court are analyzed in the next section of this

brief. Suffice it to point out here that Plessy v. Ferguson was

part of the process by which the Court in the latter part of the

nineteenth century failed to preserve for the Negro many of the

major gains o f abolition.

W e submit that the Court should return to the original meaning

of the Fourteenth Amendment. W e grant, as Plessy implies, that

termination of segregation is a break with tradition. But we

contend that there is nothing in the tradition of Negro slavery

64For discussion of the policy bases of the reconstruction decisions,

see 2 Warren, The Supreme Court in United States History 608

(1926). He lists three factors: the desire to eliminate “ the Negro

question” from national politics; the desire to relegate the Negroes

to state authority; and the desire to restore confidence in the Court

in the South. Our central position is that the Amendment should not

have been sacrificed for any or all of these considerations.

22

that is worth preserving. The Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fif

teenth Amendments committed the country to the great experi

ment of making a complete break with that tradition. When

Charles Sumner gave the abolitionists the formula of equality

before the law, he did not mean equality with reservations, equal

ity with segregation. Decisions such as Plessy v. Ferguson turn

the Fourteenth Amendment into a phantom or a grotesque mis

take. As Senator Frelinghuysen said in presenting the anti-segre

gation Civil Rights Bill of 1875 to the Senate:

“ If, sir, we have not the Constitutional right thus to legis

late, then the people o f this country have perpetrated a

blunder amounting to a grim burlesque over which the world

might laugh were it not that it is a blunder -over which

humanity would have occasion to mourn. Sir, we have the

right, in the language of the Constitution, to give ‘to all

persons within the jurisdiction of the United States the equal

protection of the laws’.” 65

This Court should return to the original purpose of the equal

protection clause, to forbid distinctions because o f race. State-

enforced segregation is unconstitutional because it makes such a

distinction. As Senator Edmunds put it, it is “ slave doctrine”

to make color and race reasons for distinctions among citizens.

Segregation is discrimination. Railroad Co. v. Brown, supra.

II.

THE BASIC POLICIES UNDERLYING THE COURT’S

A PPR O V A L OF SEGREGATION IN PLESSY V. FER

GU SON H AVE, IN THE YEARS INTERVENING SINCE

T H A T DECISION, PROVED T O BE NOT ONLY

W H O L L Y ERRONEOUS BUT SERIOUSLY DESTRUC

TIVE OF THE DEMOCRATIC PROCESS IN THE

UNITED STATES.

If the meaning of equal protection, whether considered in terms

o f historic intent or of the ordinary meaning of words, is clearly

incompatible with segregation, as we say it is, then the further

task confronts us o f assessing the underlying bases of Plessy v.

652 Cong. Rec. 3451, 43rd Cong., 1st Sess. (1874).

23

Ferguson. Concededly “ a page o f history is worth a volume of

logic.” New York Trust Co. v. Eisner, 256 U.S. 345, 349

(1921). This Court must deal with the same practical consider

ation that faced the Court in the nineteenth century. Petitioner,

if he would persuade you to reconsider Piessy, must persuade you

that Harlan’s dissent had more than a theoretical validity.

Two fundamental judgments of fact and policy underlay the

decision of the majority in Piessy v. Ferguson. One was the

Court’s acceptance of the premise that, since “ [legislation is pow

erless to eradicate racial instincts or to abolish distinctions based

upon physical differences,” it is impossible to eliminate segrega

tion founded in the “usages, customs and traditions” of the com

munity, and hence the Constitution must bow to the inevitable.

The other was the Court’s assumption that the wiser policy was

to let events take their course and that governmental intervention

“ can only result in accentuating the difficulties of the present situ

ation.” 163 U.S. at 550-2.

Over half a century has passed since the Court decided Piessy

v. Ferguson. In these years much that was obscure about the

practice of segregation has become clarified. As events have

unfolded, as trends have become more distinct, as additional

knowledge has been gained, the impact of segregation upon Amer

ican life has emerged more clearly. In the light o f these inter

vening developments, the basic judgments made by the Court in

Piessy v. Ferguson have proved to be erroneous. Indeed, far

from solving or even alleviating the problem of racial segregation

the decision of the Court has tended to intensify it and to create

conditions that threaten to undermine the very structure o f Amer

ican democratic society.

1. The judgment of the Court in Piessy v. Ferguson that

direct governmental intervention to eliminate segrega

tion is ineffective to overcome the prevailing customs of

the community has proved to be without foundation.

There are severe limitations, of course, upon the effectiveness

of direct legal compulsion to wipe out the gap that exists between

24

American theory and certain American practices in race relations.

But the fact is that the ideal of racial equality is a deeprooted

moral and political conviction o f the American people. Decisions

of this Court upholding that conviction, therefore, cannot fail to

have a profound and far reaching effect upon the constant strug

gle being waged between ideal and practice. And, conversely,

a decision that fails to give support to that conviction must neces

sarily have important depressing and retarding consequences.

Experience has shown that this Court is not as impotent in the

field of race relations as the majority in Plessy v. Ferguson

assumed. On the contrary every decision of this Court against

racial discrimination has made a significant contribution toward

the achievement of racial equality.

Concrete evidence is available, for instance, that the decisions

of this Court in the white primary cases have not only eliminated

the institution of white primaries but have resulted in a substan

tial increase in Negro voting. V . O. Key, in his careful study

entitled Southern Politics, reports that except in four states of

the Deep South the decision in Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649

(1944), was accepted “ more or less as a matter of course.” 66

Pointing out that the effect o f the decision was not felt until the

1946 primaries, he notes that “ Florida experienced a sharp in

crease in Negro registration after 1944” ; that “ [i]n 1946 the

voting status of Georgia Negroes changed radically,” the number

of Negro registrants rising to an estimated 110,000; and that in

Texas, “ with a few scattered local exceptions, Negroes voted

without hindrance in the 1946 Democratic primaries.” 67 Key

reports that four states— South Carolina, Alabama, Mississippi

and Georgia— made strenuous efforts to avoid the effect of the

Allwright case, but that these efforts were quickly nullified by the

courts in both South Carolina and Alabama. With respect to

South Carolina he observes:

“ Negroes have encountered stubborn opposition to even

a gradual admission to Democratic primaries in South Caro

66Key, Southern Politics 625 (1949).

67Id. at 625, 519-521.

25

lina. The last vestige of the white primary was stricken

down by court action in that state in 1948. Prior to that

time virtually no Negroes voted in the primaries. About

35,000 are reported to have cast ballots in the 1948 prim

ary.” 68

Thus it is clear that judicial decisions have been a powerful

influence in assisting the Negro to obtain the right o f franchise.

The decision of this Court in Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U.S. 373

(1946), has made an important contribution to racial equality in

the field of transportation.69 And evidence was offered in the

instant case showing that where segregation in the University

of Maryland Law School was ended by judicial compulsion the

subsequent experience was wholly satisfactory.70

That the majority in Plessy v. Ferguson greatly over-estimated

the practical difficulties of eliminating segregation through gov

ernmental action is likewise apparent from the accumulation of

evidence in recent years that discriminatory practices, long rooted

in the “ usages, customs and traditions” of the community, can

be successfully eradicated. The President’s Committee on Civil

Rights, in one of the most significant findings of its well-docu

mented report, concludes:

“ If reason and history were not enough to substantiate

the argument against segregation, recent experiences further

strengthen it. For these experiences demonstrate that segre

gation is an obstacle to establishing harmonious relationships

among groups. They prove that where the artificial barriers

that divide people and groups from one another are broken,

tension and conflict begin to be replaced by cooperative effort

and an environment in which civil rights can thrive.” 71

68Id. at 522. For a full account of Negro voting and the white

primary litigation, see id. at 517-22, 619-43. See also Murray (E d.),

The Negro Handbook 48-53 (1949). It has been estimated that the

number of Negroes registered to vote in the South increased from

211,000 in 1940 to over 1,000,000 in 1948. Id. at 53.

69See, e.g., id. at 64.

70R. 290. This evidence was excluded by the trial court.

71Report o f President’s Committee on Civil Rights, To Secure

These Rights 82-3 (1947).

26

Specifically in the field of education I. E. Taylor, after noting

the increase of N egro teachers in white colleges, observes:

“ Reports are coming in that Negro scholars are giving

a good account of themselves, that their students are enthu

siastic and open-minded, and that alumni and parents are

taking the situation calmly.” 72 73 * *

The elimination of segregation in public housing raises issues

perhaps more difficult than those involved in its elimination from

higher education. Yet Charles Abrams, one o f the country’s fore

most authorities on housing, w rites:

“ W here Negroes are integrated with whites into self-

contained communities without segregation, reach daily con

tact with their co-tenants, are given the same privileges and

share the same responsibilities, initial latent tensions tend

to subside, differences become reconciled, cooperation en

sues and an environment is created in which interracial

harmony will be effected.