Appellants' Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1985

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Hardbacks, Briefs, and Trial Transcript. Appellants' Brief, 1985. 089adb30-d992-ee11-be37-6045bddb811f. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/16980576-1595-490e-9b17-cc2fce6a2e39/appellants-brief. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

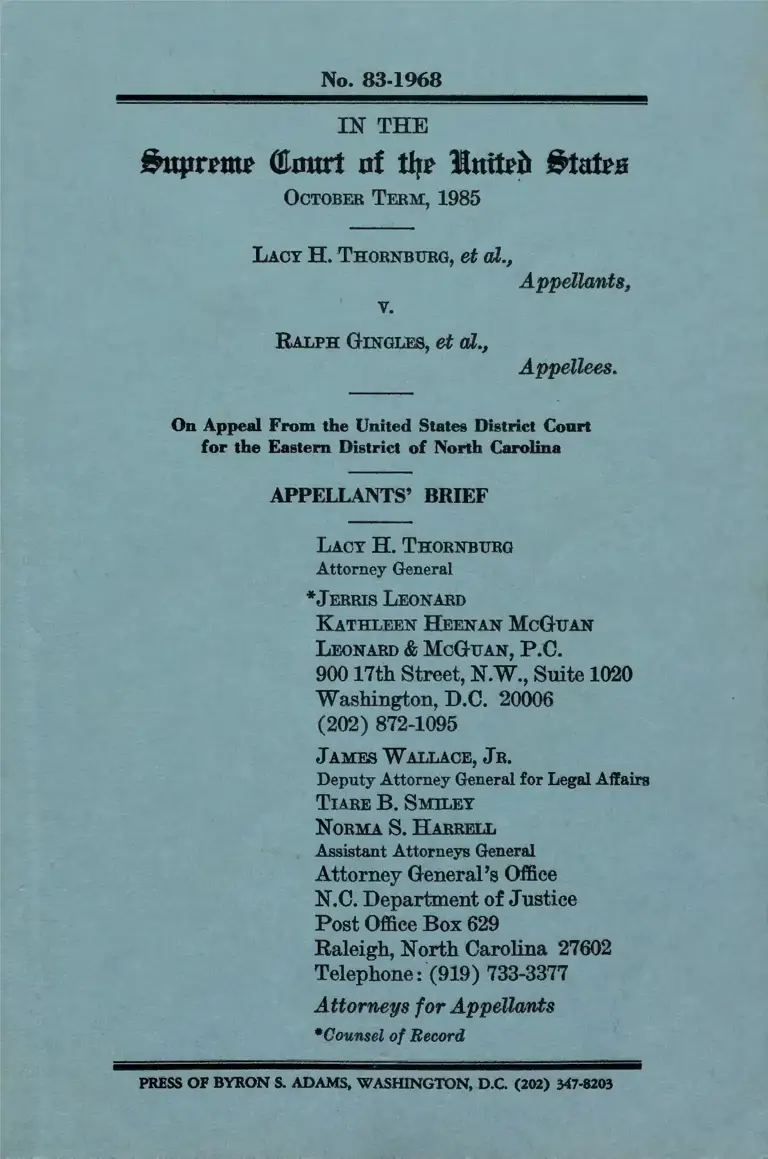

No. 83-1968

IN THE

&uprtmt Qtnurt nf tqt lluittb &lutts

OCTOBER TERM, 1985

LAcY H. THORNBURG, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

RALPH GINGLES, et al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal From the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of North Carolina

APPELLANTS' BRIEF

LACY H. THORNBURG

Attorney General

* J ERRIS LEONARD

KATHLEEN HEENAN McGuAN

LEONARD & McGuAN, P.O.

900 17th Street, N.W., Suite 1020

Washington, D.C. 20006

(202) 872-1095

JAMES WALLACE, JR.

Deputy Attorney General for Legal Affairs

TIARE B. SMILEY

NoRMA S. HARRELL

Assistant Attorneys General

Attorney General's Office

N.C. Department of Justice

Post Office Box 629

Raleigh, North Carolina 27602

Telephone: ·(919) 733-3377

Attorneys for Appellants

•counsel of Record

PRESS OF BYRON S. ADAMS, WASHINGTON, D.C. (202) 347-8203

1

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

I. Whether Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act en

titles protected minorities, in a jurisdiction in

which minorities actively participate in the politi

cal process and in which minority candidates win

elections, to safe electoral districts simply be

cause a minority concentration exists sufficient to

create such a district.

II. Whether racial bloc voting exists as a matter of

law whenever less than 50 percent of the white

voters cast ballots for the black candidate.

ll

PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDING BELOW

The Appellants, defendants in the action below, are

as follows: Lacy H. Thornburg, Attorney General of

North Carolina; Robert B. Jordan, III, Lieutenant

Governor of North Carolina; Liston B. Ramsey,

Speaker of the House; The State Board of Elections

of North Carolina; Robert N. Hunter, Jr., Chair

man, Robert R. Browning, Margaret King, Ruth T.

Semashko, William A. Marsh, Jr., members of the

State Board of Elections; and Thad Eure, Secretary

of State.

Ill

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

QuESTIONs PRESENTED ..... ·. . . . . . . . . . . . • . . . . • . . . . . . . 1

pARTIES TO THE PROCEEDING BELOW . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ll

TABLE OF AuTHORITIES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . • • . . . • . . . • v

OPINIONS BELOW . . . . . • . • . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . • • 1

JURISDICTION ............. ... ............ .. . : . . . . . . 1

CoNsTITUTIONAL PRoVISIONS AND STATUTES . . . . • . . . . • . 2

STATEMENT OF THE CASE • . . . . . • . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . • . . 2

The Genesis of the Challenged Redistricting Plans. 2

The Plaintiffs' Claim . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

Political Participation and Ele:ctoral Success of

Blacks in the Challenged Districts . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

V~oter Registration . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

SuMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

ARGUMENT . . . . • . • . • . . . . . . . . • . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

I. Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act does not entitle

protected minorities, in a jurisdiction in which mi

norities actively participate in the political process

and in which minority candidates win elections, to

safe electoral districts simply b~cause a minority

concentration exists sufficient to create such a dis-

trict ....... , . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

A. History of official discrimination which touched

the right to vote. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

iv

TABLE OF CoNTENTS continued

Page

B. The extent to which voting is racially polarized. 27

C. The majority vote requirement. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

D. The socio-economic effects of discrimination

and polit~cal participation. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

E. Racial appeals in political campaigns. . . . . . . . . 30

F. The extent to which blacks have been elected. . . 32

G. Responsiveness. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

H. Legitimate state policy behind county-based

representation. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

II. Racially polarized voting is not established as a

matter of law whenever less than a majority of

white voters vote for a black candidate. . . . . . . . . . . 35

·CoNCLUSION ....... . ........................ . ........ 45

v

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES: Page

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Develop

ment Corp., 429 U.S. 252 (1977) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

Boykins v. City of Hattiesburg, No. H77-0062(c) (S.D.

Miss. March 7, 1984), at 8 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

City of Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1981) ... ... passim

Collins v. City of Norfolk, No. 83-526·-N (E.D. Va. July

19, 1984) .................................... 39, 43

David v. Garrison, 553 F.2d 923, 927 (5th Cir. 1977) . . 20

Dove v. Moore, 539 .F.2d 1152, 1154 (8th Cir. 1976) . . . 20

Hendrix v. Joseph, 559 F.2d 1265 (5th Cir. 1977) . . . . . 25

Jones v. City of Lubbock, 730 F.2d 233 (5th Cir. 1984)

(reh'g en bane denied) ..................... 39,42-43

Lee County Branch of the NAACP v. City of Opelika,

748 F.2d 1473 (5th Cir. 1973) . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . 43

Major v. Treen, 574 F.Supp. 325, 65 (E.D. La. 1983) . 25

McMillan v. Escambia County, Florida, 688 F.2d 960

(5th Cir. 1982) . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40

NAACP v. Gadsden County School Board, 691 F.2d

978 (11th Cir. 1982) . .. . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . 40

Overton v. City of Austin, No. A-84-CA-189 (N.D. Tex.

March 12, 1985) at 26 ..................... 31, 33, 43

Rogers v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613 (1982) .............. 34, 40

Seamon v. Upham, Civil N·o. P-81-49-CA (E.D. Tex.

Jan. 30, 1984) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

Terrazas v. Clements, 537 F.Supp. 514 (N.D. Tex.

1984) ........................ ; .............. 39, 43

White v. Regester, 412 U.'S. 755 (1973) ............ passim

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976) ........... 15-16

Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir. 1974) . 22, 24

Vl

TABLE OF AuTHORITIES continued

Page

CoNSTITUTIONs:

United States Constitution, Fifteenth Amndment . 2, 15, 16

North Carolina Constitution, Art. II, ~ 3(3) . ......... 2, 3

North Carolina Constitution, Art. II, ~ 5(3) .......... 2, 3

STATUTES:

Voting Rights Act of 1965, as amended . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

Section '2 ( 42 USC ~ 1973) . . ......... . .... . . passim

Section 5 ( 42 USC ~ 1973c) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2, 3, 4, 11

28 u.s.c. ~ 1253 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

MISCELLANEOUS :

128 Cong. Rec. S. 6920 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

128 Cong. Rec. S. 6964 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

128 Cong. Rec. S. 6962 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

IN THE

~uprrmr Qtnurt nf tqr l!tuitrb ~tatrn

OCTOBER TERM, 1985

, No. 83-1968

LACY H. THORNBURG, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

RALPH GINGLES, et al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal From the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of North Carolina

APPELLANTS' BRIEF

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of North Carolina in this

case was rendered on .January 27, 1984. A copy of

the Court's Opinion and Order is set out in the .Juris

dictional Statement at AppendL'\: A.

JURISDICTION

The case below was a class action by black voters

of North Carolina challenging certain districts in the

post-1980 redistricting of the North Carolina General

Assembly. The appellants filed their Notice of Appeal

on February 3, 1984. This Court noted probable juris

diction on April 29, 1985. The jurisdiction of this

Court is invoked under 28 U.S.C. § 1253.

2

CONSTITUTIONAL PROV1SIONS AND STATUTES

The United States Constitution, Fifteenth Amend

ment, and Sections 2 and 5 of the Voting Rights Act

of 1965, as amended, 42 U.S.C. §§ 1973, 1973c are set

forth in the Jurisdictional Statement at 59a. The fol

lowing provisions of the North Carolina Constitution

are not contained in the Jurisdictional Statement:

Art. II,§ 3(3), N.C. Const.

"No county shall be divided in the formation of

a senate district."

Art. II,§ 5(3), N.C. Const.

"No county shall be divided in the formati ::m of

a representative district."

STATEMENT OF TilE CASE

The Genesis of the Challenged Redistricting Plans

In July of 1981, the North Carolina General As

sembly enacted a legislative redistricting plan in order

to conform the State Senate and House of Repre

sentative Districts to the 1980 census. In keeping with

a 300 year old practice in the State, the · plans con

sisted of a combination of single member and multi

member districts and each district was composed of

either a single county, or two or more counties, so that

no county was divided between legislative districts.

The plaintiffs below filed this action on September 16,

1981 in the United States District Court for the East

ern District of North Carolina alleging among other

things, that the multimember districts diluted black

voting strength.

In October 1981, in a special session, the General

Assembly repealed and reworked the House plan to

3

reduce the population deviations. Because forty of

North Carolina's 100 counties are covered by Section

5 of the Voting Rights Act, the revised House plan

and the Senate plan were submitted to the Attorney

General for review.1 The Attorney General interposed

objections to both proposals. He found that the state

policy against dividing counties resulted in the crea

tion of multi-member districts which in turn tended

to submerge black voters in the covered conntiAS.2

1 Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act requires covered jurisdic

tions to either submit any voting change to the Attorney General

of the United States or to file suit in the United States District

Court for the District of Columbia for declaratory judgment.

Section 5 provides in pertinent part:

Whenever a [covered] State or political subdivision ... shall

enact or seek to administer any voting qualification or pre

requisite to voting, or standard, practice, or procedure with

respect to voting different from that in force or effect on

November 1, 1964, such State or subdivision may institute an

action in the United States District Court for the District of

Columbia for a declaratory judgment that such qualification,

prerequisite, standard, practice, or procedure does not. havP.

the purpose and will not have the effect of denying or abridg

ing the right to vote on account of race or color, or in contra

vention of the guarantees set forth in section 4 (f) (2) , and

unless and until the court enters such judgment no person

shall be denied the right to vote for failure to comply with

such qualification, prerequisite, standard, pract ice, or proce

dure: Provided, That such qualification, prerequisite, standard,

practice, or procedure has bt>en submitted by the chief legal

officer or other appropriate official of such State or subdivision

to the Attorney General and the Attorney General has not

interposed an objection within sixty days after such submis

sion . .. 42 U.S.C. § 1973c.

2 In 1968, as part of a general revision of the State Constitution,

a provision prohibiting the division of any county bt>tween State

legislative districts was adopted. Art. II, q 3 ( 3), 5 ( 3) N.C. Con st.

This Constitutional amendment merely codified a practice which had

been consistent and unbroken in North Carolina redistr ict ing since

the institution of legislative districts in the colonial perod.

4

During the early months of 1982, counsel for the

General Assembly worked closely with the Civil Rights

Division of the Department of Justice in order to

remedy those aspects of the plans found objectionable

under Section 5. In February, the General Assembly

enacted new redistricting plans in which some county

lines were broken in order to overcome the Attorney

General's objection in the covered counties of the

State. When these plans were submitted, the Attorney

General found one problematic district in each plan.

These subsequently were redrawn to Justice Depart

ment specifications. On April 30, 1982, the Senate and

House plans received Section 5 preclearance.

The Plaintiffs' Claim

The action below remained pending during the

course of these legislative proceedings, and several

amendments to the complaint were permitted to ac

commodate the successive r evisions of the redistricting

plans. ·The last supplemental complaint included, as a

basis of the plaintiffs' claim of vote dilution, Section

2 of the Voting Rights Act, as amended on June 29,

1982. In its final form, the complaint alleged that in 6

General Assembly districts, the use of multi-member

configurations diluted the voting strength of black citi

zens in violation of Amended Section 2. In addition,

the plaintiffs alleged that a concentration of black

voters was split between 2 single-member Senate dis

tricts resulting in vote dilution. The class was certified

as the class of all black residents of the State,3 and

3 Although the plaintiffs were cer t ified as the class of all black

voters in the state, their position was hardly one based on con

sensus. Four prominent black leaders testified for the State that

5

trial to a three-judge court was held for 8 days com

mencing July 25, 1983.

The plaintiffs attempted to prove that five multi

member House districts and 1 multi-member Senate

district violated Section 2. These districts were:

House District No. 23- Durham County

House District No. 36-Mecklenburg County

Senate District No. 22-Mecklenburg and

Cabarrus Counties

House District No. 39-Forsyth County

House District No. 21- W ake County

House District No. 8- N ash, Wilson, and

Edgecomqe Counties

blacks in the at-large districts had equal access to the process and

three of them specifically stated that single-member legislative

districts would hinder .rather than help blacks politically. It be

came clear during the trial that much of the impetus for the

challenge to the multi-member districting came from plaintiffs '

counsel. Neither the Chairman of the House nor the Senate Re

apportionment Committee had ever been contacted by the plain

tiffs during the legislative process regarding the desire for single

member districts. R. 1065-66, 1975.

The extent of the artifice constructed by the plaintiffs is dem

onstrated by the following vignette. Two days before trial, the

Mecklenburg Black Caucus passed a resolution supporting single

member districts. R. 1477-78. The r esolution was handwritten by

a partner in the firm representing the plaintiffs and delivered by

him to the Caucus Chairman during the Caucus meeting. R. 1489.

The issue was not on the agenda for the meeting and the members

had no notice of the vote. R. 1484. The plaintiffs then called the

Chairman of the Caucus as a witness at trial to introduce the

resolution to support their contention that the black community

was in agreement on the issue of single-member districts .

6

The plaintiffs also tried to show that Senate district

2, a single-member district was statutorily infirm be

cause the district could have been drawn to create a

59% black majority. As drawn by the legislature and

approved by the Attorney General, the district's popu

lation was 55.1% black/

Political Participation and Electoral Success

of Blacks in the Challenged Districts

The record reflects the following· facts :

Durham ·county comprised a 3-member House dis

trict which had a black voting age population of

33.6%. Stip. 59.5 Durham has had at least one black

representative to the House continuously since 1973.

Stip. 148. At the time of trial two of its five county

commissioners, one of whom is Chairman, were black

(Stip. 150), as were two of its four elected district

court judges.6 Stip. 153. The three-member Durham

County Board of Elections had a black member from

1970 until 1981, when he was appointed to the State

Board of Elections. Stip. 154. The chairmanship of

the Durham County Democratic Party was held by a

black from 1969 through 1979 and is held by a black

for the 1983-85 term. Stip. 155. One single-member

4 In order to draw a black majority Senate district in the North

east portion of the State, as the U.S. Attorney General had in

structed, it was necessary to divide many counties. The resulting

Senate District 2 contains portions of Bertie, Chowan, Gates, Hali

fax, Northampton, Hertford, Martin and Washington Counties.

5 The Stipulations of fact are contained in the Pre-trial Order.

Citations are to the number assigned to the Stipulation.

6 The facts here recited are from the record and so naturally re

flect the electoral situation in 1983 at the time of trial.

7

House district with a black population of approxi

mately 70% could be drawn within Durham County.

Stip. 144.

In addition, the evidence shows that the Durham

Committee on the Affairs of Black People is a power

ful political organization which endorses and supports

both black and white candidates for election. No can

didate in Durham can expect to get many black votes

without the endorsement of the Durham Committee.

R. 1295.

The black voting age population of Mecklenburg is

24%. Stip. 59. One of the eight House members elected

from Mecklenburg County in 1982 is black. Stip. 116.

James D. Richardson, who is also black and was run

ning in his first election for public office in 1982, came

in ninth in a race for eight seats, with only 250 votes

less than the eighth successful candidate. Stip_. 116.

This was in a field of 18 candidates. Pl.Ex. 14(d),

R. 86, 112.7 While there is currently no black senator

from the ¥ecklenburg-Cabarrus County Senate Dis

trict, James Polk, a first time candidate for public

office, ran fifth in a race for four seats in the 1982

election. Stip. 118. The Mecklenburg-Ca·barrus County

Senate District did have a black senator for three

terms from 1975 through 1980, until his death before

the 1980 elections. Stip. 117. In addition, it was stipu

lated at the time of trial that one of the five Meck

lenburg County Commissioners, Stip. 119, two of the

nine Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education mem

bers, Stip. 123, and one of the ten Mecklenburg County

'District Court judges, Stip. 122, all of whom are black,

7 Plan tiffs' Exhibits will be identified as Pl. Ex. ; Defendants'

Exhibits as Def.Ex.

8

were elected at-large. In addition, another ·black was

appointed to a vacant district court judgeship in Meck

lenburg County. Stip. 123 .

.At the time of trial a black served as the chair

person of the three member Mecklenburg County

Board of Elections. Stip. 125. The Mecklenburg Board

of Elections also had one black member in the years

1970 to 1974 and 1977 to the present. Stip. 125. The

chair of the Mecklenburg County Democratic Execu

tive committee at the time of trial and his immediate·

predecessor are also black. Stip. 126.

The City of Charlotte, ·located in Mecklenburg

County, has a population which is 31 % black. Stip.

127. Harvey Gantt, who is black, currently serves as

Mayor of that city. J.S. 35a. Charlotte also has two

black city council members elected from majority

black districts. Stip. 128.

It was stipulated at the time of trial that if Meck

lenburg County were subdivided, two single-member

House districts each with a black population of 65%

could be constructed. Stip. 110. If the Mecklenburg

Cabarrus Senate district were dismantled, one single

member Senate district with a black population of

65% could be drawn. Stip. 112.

The five-member House District 39, including most

of Forsyth County, has a 22% black voting age popu

lation. Stip. 54. Two black representatives were elected

in the 1982 elections. Stip. 132. Forsyth County has

previously elected a black representative for the 1975-

76 and 1977-78 General .Assemblies. Stip. 133. Blacks

have also been appointed by the Governor on two

occasions to represent Forsyth County in the North

Carolina House. This occurred in 1977 when a black

representative resigned, Stip. 134, and again in 1979

9

when a white representative resigned. Stip. 135. At

the time of trial one of the five Forsyth County Com

missioners, Stip. 136, and one of the eight Forsyth

County School Board members were black. Stip. 139.

Both the County Commission and the School Board

are elected at-large. In addition, when the case went

to trial the three-member Forsyth County Board of

Elections had one black member, and that Board has

had one black member every year since 1973. Stip. 141.

The City of Winston-Salem, located in Forsyth

County, has a black population of slightly more than

40% and a black voter registration of slightly less

than 32%. Stip. 142. The Winston-Salem City Council

has eight members elected from wards. Stip. 143. At

the time of trial, there were three black members

elected from majority black wards and one black

member elected from a ward with slightly less than

39% black voter registration. Stip. 143. This black

councilman, Larry Womble, defeated a white Demo

cratic incumbent in the primary and a white Republi

can in the general election in 1981. Stip. 143.

If Forsyth County .were divided into single mem

ber House districts, one district with a population over

65% black could be formed. Stip. 129.

The current Wake County six member House dele

gation includes one black member, Dan Blue, who, at

the time of trial, was serving his second term. Stip.

162. In the 1982 election, Blue received the hi~Shest

vote total of the 15 Democrats running in the primary,

Stip 162, and the second highest vote total of the 17

candidates running for the six seats in the general

election. Stip. 162. Slightly more than 20% of Wake

County's voting age population is black. Stip. 59.

10

Although no single-member black Senate district can

be constructed in Wake County, Stip. 160, Wake

elected a black Senator for the 1975-76 and 1977-78

terms. Stip. 163.

In July of 1983, one of the seven Wake County

Commissioners was black, Stip. 164, as were two of

the eight Wake County District Court Judges. Stip.

165. The Sheriff of Wake County, John Baker, is black

and at the time of trial was serving his second term.

Stip. 166. In the 1982 election for his second term,

Baker received 63.5% of the votes in the general elec

tion over a white opponent. Stip. 166. In the· Demo

cratic Primary, Baker received over 63% of the vote,

defeating two white opponents. Stip. 166. Wake Coun

ty Commissioners, District Court Judges, and the

Sheriff are all elected at large. Stip. 165, 166. Wake

County has also had a black member continuously on

its three-member Board of Elections since 1970, Stip.

169, and at the time of trial had a black chairman.

Stip. 169.

The City of Raleigh in Wake County is 27.4%

black. Stip. 171. Raleigh had a black mayor from

1973 to 1975, Stip. 172, and has had one black on

its seven-member city council since 1973. Stip. 173.

Although it is not possible to draw a black majority

single-member Senate district which is wholly within

or includes substantial parts of Wake County, Stip.

161, John W. Winters, who is black, was elected Sen

ator from Wake County for two terms, 1975 through

1978. Stip. 163.

If Wake County were subdivided into single-member

House districts, one district with a population around

65% black could be created. Stip. 158.

11

House District 8 is comprised of three whole coun

ties: Nash, Wilson and Edgecombe, all of which are

covered by Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act. Stip.

174. The Attorney General approved this four-member

at-large district. Stip. 45. Edgecombe County, which

has a voting age population which is 46.7% black,

Stip. 59, has a five-member Board of Commissioners

elected at-large and when the case went to trial, two

of its members were black. Stip. 176.

Senate district 2, a single-member district, is 55.1%

black. Stip. 190. This district which lies in an area

covered by Section 5, Stip. 190, was drawn according

to Justice Department instructions to create a dis

trict having a population that was 55 % black, regard

less of how many county lines had to be crossed.

Stip. 190. Consequently, Senate district 2, as it was

approved by the Attorney General, Stip. 45, encom

passes parts of Bertie, Chowan, Halifax, Hertford,

Martin, N orthhampton and Washington Counties. In

the 2 election years before trial, black candidates had

won 3 seats in the State House from areas within the

borders of Senate district 2. In Gates County where

49 % of the registered voters are black, a: black is cur

rently serving a term as Clerk of Court. Stip. 192.

In Halifax, several blacks have been elected to the

County Commission and the City Council of Roanoke

Rapids. It is possible to draw a black district in the

general area of Senate district 2 which is 59.4% black.

Stip. 188.

The plaintiffs' own witnesses were convincing evi

dence of the openness of the political process in North

Carolina. Their witnesses included Phyllis Lynch, the

Chairperson of the Mecklenburg Board of Elections

and a force in the County Black Caucus. R. 427. Sam

12

Reid, as the head of the Vote Task Force in Mecklen

burg County, is a special Registration Commissioner

appointed by the Mecklenburg County Board of Elec

tions to respond to special requests to register citizens

at civic, community and church gatherings. R. 470.

Frank Ballance, the representative to the General As

sembly from House District 7, is also Chairman of

the Second Congressional District Black Caucus. R.

592. Larry Little is an alderman in the City of

Winston-Salem. He is also Chairman of the City's

Public Works Commission. R. 592. Willie Lovett,

Chairman of the Durham Committee on the Affairs

of Black People, R. 646, testified that the "impact

and responsiveness in the community to the Durham

Committee and its recommendations and programs is

rather massive." R. 670. G. K. Butterfield, an attorney,

organized the Wilson Committee on the Affairs of

Black People and is also a gubernatorial appointee

to the State Inmates Grievance Board. R. 695, 719,

936. Fred Belfield is President of the Nash County

N.A.A.C.P. R. 737, 754. All of these plaintiffs' wit

nesses are black.

Voter Registration

In October of 1982, the State Board of Eler.tions

reported the following voter registration statistics for

the challenged counties: Stip. 58.

% White V AP* % Black V AP

Durham

Forsyth

Mecklenburg

• Voting Age Population

Registered Registered

66.0

69.4

73.0

52.9

64.1

50.8

13

% White V AP* % Black V AP

Wake

Nash

Wilson

Edgecombe

Bertie

Chowan

Gates

Halifax

Hartford

Martin

N orthhampton

Washington

• Voting Age Population

Registered R egistered

72.2

64.2

64.2

62.7

76.6

74.1

83.6

67.3

68.7

71.2

82.1

75.6

49.7

43.0

48.0

53.1

60.0

54.0

82.3

55.3

58.3

53.3

73.9

67.4

Although black registration still lags behind white

registration, the larger gains over the past several

years have been among the black population. Def.Ex.

14, R. 505, 510. In the period 1980 to 1982, statewide

registration among whites dropped by 112,000, while

among blacks it increased by 12,096-as much as 50%

in some counties. R. 585. This increase was largely

due to an effort launched by the State Board of

Elections in 1980 to increase voter registration in

general, and in particular among groups traditionally

underregistered. Since the publication of these regis

tration figures, the General Assembly has passed leg

islation to further facilitate voter registration. R.

1335. Now public libraries offer voter registration

during library hours. R. 1335-36. In addition, many

public high schools now have a permanent voting

registrar. R. 1335-36. The legislation further provides

that branches of the Department of Motor Vehicles

14

offer voter registration so that the opportunity to

register is available to everyone who comes in to

renew or replace a driver's license or to conduct any

other business. R. 1336.

Despite the great strides made by the State in elimi

nating any lingering effects of past electoral discrimi

nation by facilitating and encouraging registration,

and despite the considerable electoral success achieved

by blacks in North Carolina, the district court found

that the challenged districts violated Section 2. The

court reached this untenable conclusion because it

never uncovered the core value, the specific right,

protected by the statute. Section 2 guarantees equal

opportunity to participate in the political process.

The court below, however, struck down the challenged

districts because they did not guarantee electoral

success.8

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act as amended

by Congress in 1982 guarantees equal access to the

political process. The focus of the provision is oppor

tunity, not guaranteed results. Congress incorporated

the analysis and specific language of White v. Reg

ester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973) into the amended statute.

Thus a violation of Section 2 is established when

plaintiffs demonstrate that the political processes lead-

8 Apparently the court adopted this conclusion of the plain tiffs'

expert, Bernard Grofmann :

My fifth general conclusion is as follows: Even though a con

stituency has elected a black candidate in the past, this does

not provide a guarantee that it will do so in the future, espe

cially if the black incumbent who is the present occupant of

that position does not run in the future in subsequent races.

15

ing to nomination and election are not equally open

to participation by the racial minority group.'

The record below shows that blacks in North Caro

lina enjoy active and meaningful participation in

politics. This is evidenced by the fact that out of

11 black candidates who ran for election to the Gen

eral Assembly in 1982, from the districts challenged

by the plaintiffs, 7 were elected.

The district court erred in equating access with·

guaranteed electoral success. This runs counter to the

legislative history of Section 2, and the judicial prece

dents which Congress explicitly invoked.

The district court found that racial bloc voting

exists whenever less than 50 percent of the whites

vote for a black candidate. This is an arbitrary defini

tion which has no relationship to real politics or

electoral outcomes. By virtue of this definition the

court found "severe" racial polarization in elections

in which the black candidate received 40% of the

white vote ·and won the election. Racial bloc voting

has legal significance only when it operates to pre

vent black candidates from being elected to office.

ARGUMENT

Introduction

On .Tune 29, 1982 Congress enacted amendments

to the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Foremost among

the changes adopted was a complete transformation

of Section 2. Prior to this 1982 amendment, Section

2 had been viewed as simply the statutory restate

ment of the Fifteenth Amendment. Oity of 111 obile

v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1981). Consistent with this

Court's rulings in such cases as Washington v. Davis,

16

426 U.S. 229 (1976) and Arling.ton Heights v. 111 etro

politan Housing Development Corp., 429 U.S. 252

(1977), it was necessary to prove both disparate im

pact and discriminatory intent in order to establish

a violation of the Fifteenth Amendment and conse

quently, of Section 2. This was the holding of the

plurality of the Court in City of 111 obile, sup'ra.

Congress amended Section 2 to eliminate the intent

standard imposed by Mobile. Section 2 (a) as amended

provides that no voting law shall be imposed or ap

plied in a manner which results in a denial or abridge

ment of the right to vote on account of color. Sub

section (b) in its entirety reads:

(b) A violation of subsection (a) is established if,

based on the totality of circumstances, it is

shown that the political processes leading to

nomination or election in the state or political

subdivision are not equally open to participa

tion by members of a class of citizens pro

tected by subsection (a) in that its members

have less opportunity than other members of

the electorate to participate in the political

process and to elect representatives of · their

choice. The extent to which members of a pro

tected class have been elected to office in the

state or political subdivision is one ''circum

stance" which may be considered, provided that

nothing in this section establishes a right to

have members of a protected class elected in

numbers equal to their proportion in the popu

lation. 42 U.S.C. § 1973.

The language of Section 2 is clear- the statute is

intended to afford to minority citizens the opportunity

to meaningfully participate in the political process.

It explicitly disavows any guarantee of electoral suc

cess or proportional representation.

17

The legislative history supports a reading of Sec

tion 2 which focuses on equal access. On October 15,

1981, the House of Representatives passed H.R. 3112

which transformed Section 2 into a results test. The

House version read as follows :

No voting qualification or prerequisite to voting,

or standard, practice, or procedure shall be im

posed or applied by any State or political sub

division in a manner which results in a denial or

abridgement of the right of any citizen of the

United States to vote on account of race or color

or in contravention of the guarantees set forth

in Section 4(f) (2). ·The fact that members of a

minority group have not been elected in numbers

equal to the group's proportion of the population

shall not, in and of itself, constitute a violation

of this section.

The Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on the Consti

tution rejected the proposed amendment and recom

mended the retention of the existing statutory lan

guage. Report of the Subcommittee on the Constitution

of the Senate Committee on the Judiciary, 97th Cong.,

2d Sess., Report on S. 1992. Although many members

of the Senate Judiciary Committee supported the

House language, there were not enough votes to re

port the House version to the floor. 128 Cong. Rec. S.

6920 (daily ed. June 17, 1982) (statement of Sen.

Hatch). Senator Dole avoided a stalemate by con

structing a compromise that allowed a majority of the

Judiciary Committee to agree upon a bill. 128 Cong.

Rec. S. 6964 (daily ed. June 17, 1982) (statement of

Sen. Kennedy).

The Dole compromise, the bill ultimately adopted

by Congress, incorporates language from the land-

18

mark vote dilution case, White v. Regester, 412 U.S.

755 (1973). In White the Court WTote:

The plaintiff's burden is to produce evidence to

support findings that the political processes lead

ing to nomination and election were not equally

open to participation by the group in question

that its members had less opportunity than did

other residents in the district to participate in

the political processes and to elect legislators of

their choice. 412 U.S. at 766.

Senator Dole made it clear that, just as in White v.

Regester, the touchstone of the new Section 2 would

be equal access and opportunity. S. Rep. No. 417, 97th

Cong., 2d Sess. at 193. [hereinafter S. Rep.] On the

floor of the Senate, in answer to Senator Thurmond's

question as to whether the focus of the amended stat

ute would be on election results or equal access to the

process, Senator Dole responded, "[t]he focus of Sec

tion 2 is on equal access, as it should be." 128 Cong.

Rec. S. 6962 (daily ed. June 17, 1982) (statement of

Sen. Dole). He also explained in his views included

in the Senate Report that, "[c]itizens of all races are

entitled to have an equal chance of electing candidates

of their choice, but if they are fairly afforded that

opportunity and lose, the law should offer no rem

edies." S. Rep. at 193.

The Senate Report echoes the view of Senator Dole

that the amendment was intended to codify the equal

access standard of White v. Regester, S. Rep. at 22-24.

Indeed the Senate Report explicitly states that the

substitute amendment "codifies the holding in White,

thus making clear the legislative intent to incorporate

that precedent and the extensive case law which de

veloped around it into the application of Section 2."

S. Rep. at 32.

19

The district court erred in failing to apply Section

2 in a manner consistent with the judicial precedents

expressly identified by Congress. Although the court

acknowledged Congress' reliance on White v. Regester,

it did not seriously attempt to integrate the language

of Section 2 with the case law which Congress sought

to codify. Inasmuch as the language of subsection (b)

came directly from this Court's opinion in White, it

is obvious that the statute must be construed in light

of this precedent. Because the district court attempted

to interpret the amended provision without this essen

tial judicial background, it reached several erroneous

conclusions of law. The court's fundamental miscon

ception was that Section 2 .creates an affirmative en

tilement to proportional representation. Building on

this foundation, the court was able to make a finding

of vote dilution even though it was evident that black

residents of the challenged districts had the same op

portunity as whites to participate in the political

process and to elect candidates of their choice.

I. Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act does not entitle protected

minorities, in a jurisdiction in which minorities actively

participate in the political process and in which minority

candidates win elections, to safe electoral districts simply

because a minority concentration exists sufficient to create

such a district.

The district court erred in equating a violation of

Section 2 with the absence of guaranteed proportional

representation. The Court flatly stated:

The essence of racial vote dilution in the White

v. Regester sense is this: that primarily because

of the interaction of substantial and persistent

racial polarization in voting patterns with a chal-

20

lenged electoral mechanism, a racial minority with

distinctive group interests that are capable of aid

or amelioration by government is effectively de

nied the political power to further those interests

that numbers alone would presumptively give it

in a voting constituency not racially polarized in

its voting behavior. (citation omitted) .. J.S. at 14a.

This statement epitomizes the district court's reading

of the amended statute. Although blacks had achieved

considerable success in winning state legislative seats

in the challenged districts, their failure to consistently

attain the number of seats that numbers alone would

presumptively give them, (i.e., in proportion to their

presence in the population) the court found that Sec

tion 2 had been violated. All of the vote dilution cases

following White run counter to this interpretation.

In David v. Garrison, for example, the Fifth Circuit

wrote that "dilution occurs when the minority voters

have no real opportunity to participate in the political

process." 553 F.2d 923, 927 (5th Cir. 1977). And in

Dove v. Moore, the Eighth Circuit in discussing vote

dilution under the pre-Mobile constitutional standard

now codified in Section 2, stated that the "consti tu

tional touchstone is whether the system is open to full

minority participation not whether proportional rep

resentation is in fact, achieved." 539 F.2cl 1152~ 1154

(8th Cir. 1976).

Moreover, the court's understanding of vote dilution

runs contrary to specific instruction in the legislative

history. The Senate Report explained that some op

ponents of the results test had suggested that it would

enable a plaintiff to win a vote dilution suit by show

ing an at-large election scheme, underrepresentation

of minorities, and a mere scintilla of other evidence.

21

This is essentially the same standard enunciated by

the district court, and the Senate Report states that

"this position is simply wrong." S. Rep. at 33.

In addition, the court failed to understand the dis

claimer at the end of subsection (b). The statute states

that "nothing in this section establishes a right to

have members of a protected class elected in num

bers equal to their proportion in the population." 42

U.S.C. § 1973. The district court interpreted this to

mean only that lack of proportional representation in

and of itself does not constitute a violation of Section

2. J.S. at 15a, n.13. Once again, the Senate Report

specifically disavows the interpretation adopted by the

court. The Report states that the House version sim

ply assured that a failure to achieve proportional

representation in and of itself would not constitute a

violation. S. Rep. at n.225. The Senate strengthened

the House language to make it explicit that the

amended section creates no affirmative right to pro

portional representation. S. Rep. at 68.

Subsection (b) of the amended statute states that

a finding of discriminatory results should be based on

the totality of circumstances. The Senate Report elab

orates on this by supplying a list of factors which the

Committee suggested might be indicative of vote dilu

tion. S. Rep. at 28.9 These factors were culled from

9 The Senate Report criteria are as follows :

1. the extent of any history of official discrimination in the

state or political subdivision that touched the right of the

members of the minority group to register, to vote, or other

wise to participate in the democratic process;

2. the extent to which voting in the elections of the state or

political subdivision is racially polarized;

footnote continued on next page

22

the analytical framework in White and also from

Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir. 1974),

a Fifth Circuit case · which followed and applied

White.

The proper application of the analysis suggested

by the Senate Report, and the purpose of Section 2

generally, are best examined in light of White and

City of 1lfobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1981). The

facts of Mobile, the case to which Congr ess adversely

reacted, and those of White, which set the standard

that Congress wished to codify, provide the back

ground necessary t.o apply the amended statute. Com-

3. the extent to which the state or political subdivision has

used unusually large election districts, majority vote require

ments, anti-single shot provisions, or other voting practices or

procedures that may enhance the opportunity for discrimina- .

tion against the minority group.

4. if there is a candidate slating process, whether the members

of the minority group have been denied access to that process ;

5. the extent to which members of the minority group in the

state or political subdivision bear the effects of discrimination

in such areas as education, employment and health , which

hinder their ability to participate effectively in the political

process;

6. whether political campaigns have been characterized by

overt or subtle racial appeals;

7. the extent to which members of the minority group have

been elected to public office in the jurisdiction.

Additional factors that in some cases have had probative value

as part of plaintiffs' evidence to establish a violation are :

whether there is a significant lack of responsiveness on the

part of elected officials to the particularized needs of the mem

bers of the minority group.

whether the policy underlying the state or polit ical subdhri

sion 's use of such voting qualification, prerequisite to voting,

or standard, practice or procedure is tenuous.

23

parisons of the record in this case with the findings

of the district courts in White and Mobile make it

clear that Section 2 was never intended to reach the

circumstances of the case at bar.

In White v. Regester the Court upheld the district

court's order to dismantle multimember districts in

Dallas and Bexar Counties in Texas. While the White

Court recognized that multimember districts might be

used invidiously to minimize the electoral strength of

racial minorities, it also stressed that to sustain such a

claim "it is not enough that the racial group allegedly

discriminated against has not had legislative seats in

proportion to its voting potential." 412 U.S. at 766.

The record in White however, showed that the

counties in which the Plaintiffs challenged the at

large system had the following characteristics : 1) a

history of official racial discrimination, which con

tinued to touch the right of blacks to register, vote

and to participate; 2) a majority vote requirement

jn party primaries; 3) a place rule which reduced

multimember elections to a head-to-head contest for

each position; 4) only 2 blacks elected to the Texas

legislature since Reconstruction; 5) a slating system

which excluded minorities; 6) a white dominated or

ganization which controlled the Democratic party and

which did not need or solicit black support; 7) a con

sistent use of racial campaign appeals by the Demo

cratic party. The district court concluded and the

Supreme Court agreed that the net result of these

factors was to shut racial minorities out of' the elec

toral process.

Likewise in Mobile, the plaintiffs attacked the at

large method of electing the city commissioners, 428

24

F.Supp. 384 (S.D. Ala. 1977). The district court,

applying the test used in Zirwmer v. McKeithen, 485

F.2d 1297 (5th Cir. 1973), found that the eledoral

system there was marked by a majority vote require

ment in both the primary and general elections, num

bered posts, and no residency requirement. In addi

tion, in a city whose population was 35.4% black, no

black person had ever been elected to the Board of

Commissioners because of acute racial polarization in

voting. The Court found further that the city officials

had made no effort to bring blacks into the main

stream of the social and cultural life by appointing

them to city boards and committees in anything more

than token numbers. The plaintiffs ·also marshalled

evidence of police brutality towards blacks, mock

lynchings and failure of elected officials to take ac

tion in matters of vital concern to black people. On

appeal to the Fifth Circuit, the Court noted that

the plaintiffs had prevailed on each and every Zimmer

factor, 571 F.2d 238, 244 (5th Cir. 1978).

The record in the present case differs dramatically

from the pictures drawn in White and Mobile. Multi

member districts in North Carolina simply do not

operate to exclude blacks from the political process

as they did in those cases. The degree of success at

the polls enjoyed by black North Carolinians is suf

ficient in itself to distinguish this case from White

and Mobile and to entirely discredit the plaintiffs'

theory that the present legislative districts deny blacks

equal access to the political process.

The court below reviewed the evidence by discuss

ing essentially the same factors consider ed in White

and Mobile. Contrary to the court's conclusion, how-

25

ever, no matter how one weights and weighs the evi

dence presented, it does not add up to denial of equal

access to the political forum.

A. History of official discrimination which touched the

right to vote.

The plaintiffs introduced evidence, not refuted by

the State, that North Carolina had in the past pre

vented blacks from actively participating in the demo

cratic· process. Stips. 85-94; R. 224-324. This evidence,

however, is relevant only if these past impediments

to political participation have a perceptible impact

on the ability of blacks to involve them,selves effec

tively in the democratic processes of North Carolina

today. See Major v. Treen, 574 F.Supp. 325, 65 (E.D.

La. 1983). In Hendrix v. Joseph, 559 F.2d 1265 (5th

Cir. 1977) the court warned that because no area in

the South was free of past discrimination in voting,

the present effects of such discrimination must be

carefully assessed. ''The factual question is,'' the

court wrote, "whether that discrimination precludes

effective participation in the electoral system by

blacks today in such a way that it can be remedied

by a change in the electoral system." 559 F .2d at

1270. (emphasis added).

The record in this case shows that the drive to en

gage blacks in the electoral process in North Caro

lina began before the passage of the Voting Rights

Act in 1965. R. 1178-79, 1306-07. In Mecklenburg

and Wake Counties, for example, voter registration

drives aimed particularly at increasing black regis

tration began before that date. Id. Over the past

years, the State Board of Elections has redoubled its

26

efforts to reach those groups in the State that are

relatively underregistered, especially blacks. The

Board of Election's most recent campaign included

a comprehensive educational program to encourage

interest in voting, and new legislation designed to

maximize access to registration. Def.Ex. 1-9, 11-15,

R. 500-06, 510. At the close of the books prior to the

1982 General elections, the Board's drive had resulted

in a 17% increase in registration among blacks. Def.

Ex. 14, R. 506, 510. By the adjournment of the 1983

Session, the General Assembly had enacted new legis

lation providing for more registrars, more registra

tion locations and generally easier access to registra

tion. R. 1335. In spite of these facts, the district

court still counted this factor against the defendants

because the percentage of eligible blacks registered is

lower than the percentage of eligible whites registered.

Although total registration among blacks is still

lower than among whites, blacks are registering at a

faster rate today than are whites. It is obvious from

this statistic alone that no barriers or impediments to

registration presently exist. In addition, the mere

fact that in the 7 challenged districts, 7 blacks were

elected to the General Assembly in 1982 demonstrates

that there are no lingering effects of past discrimi

nation.10

The Senate Report does not purport to cast in stone

the definitive inflexible list of relevant factors to be

10 The successful black candidates were Dan Blue (Wake Coun

ty); Annie Kennedy, C. B. Hauser (Forsyth County); Phil Berry

(Mecklenburg County) ; Frank Ballance ("Warren County); Ken

neth Spaulding (Durham County); C. Melvin Creecy (North

hampton Comity) .

27

considered in Section 2 cases. The factors are meant

to be exemplary of the types of evidence which might

be relevant, and the relevance of any given item may

vary from case to case. Boykins v. City of Hatties

burg, No. H77-0062(c) (S.D. Miss. March 7, 1984), at 8.

In this instance, this first factor is not particularly

relevant, largely because the State's effort to over

come the ~:ffects of past electoral discrimination have

been so successful. The mere existence of impediments

to the exercise of the franchise by minorities at some

time in the past should not "in the manner of original

sin" continue to be accounted against the State long

after the barriers have been removed and the residual

consequences ameliorated.

B. The extent to which voting is racially polarized.

Because courts have generally considered this to be

the pivotal factor in Section 2 analysis, this topic is

discussed below in detail. Suffice it to say here that

the court found "severe" racial polarization in every

election in which less than a majority of whites voted

for the black candidate-even where the black won

and white candidates also received less than a ma

jority of the white vote.

C. The majority vote requirement.

North Carolina has a majority vote requirement in

primary elections only. Stip. 88, 89. The district court

found that no black had ever lost a bid for election

to the General Assembly because of the majority vote

requirement.11 J.S. 30a. Nonetheless, the court also

11 Because the one-party nature of the state greatly inflates the

importance of victory in the Democratic primary, there is little

28

found that the majority vote requirement contributed

to the dilution of the black vote. Here again, the

Court mechanistically counted one of the Senate Re

port factors against the State without seriously con

sidering the actual impact on electoral access. If no

black candidacy has ever been impeded by the ma

jority vote requirement, it is absurd to consider the

requirement a circumstance contributing to vote dilu

tion.

D. The socio-economic effects of discrimination and

political participation.

This criterion from the Senate Report must be read

fully and in conjunction with its accompanying foot

note 114. The Report states that a court may examine

"the extent to which members of the minority group

in the state or political subdivision bear the effects

of discrimination in such areas ·as education, employ

ment. and health, which hinder their ability to par

ticipate effectively in the political process." S. Rep.

at 29. (emphasis added). Thus, a plaintiff may prop

erly introduce evidence, for example, of inferior

health care, education, and income among black citi

zens. The relevance of this highly prejudicial evi

dence, however, is contingent upon proof that the level

of participation by blacks in the political process is

depressed.

support for eliminating the majority vote requirement. In fact, a

bill introduced in the General Assembly in 1983 by Rep. Spauld

ing, who is black, would have merely reduced the requirement to

40 percent. Stip. 90. Interestingly, a study superimposin!5 Rep.

Spaulding's proposal on all legislative elections back to 1964 shows

that no additional blacks would have won as a result of this change.

R. 960-64.

29

Note 114 confirms this reading. There, Congress

expressed its intent that a plaintiff need not prove

a causal nexus between disparate socio-economic status

and depressed political activity. However, social and

economic circumstances have no relevancy at all to

the issue of vote dilution if participation by the group

claiming dilution is not in fact depressed. Note 114

does not relieve the plaintiffs of proving depressed

political participation, it merely relieves them of prov

ing the nexus between the two circumstances.

The court seems to have interpreted this factor and

. Note 114 . to say that evidence of inferior economic

and social status is proof of depressed levels of par-

ticipation in the democratic process. The plaintiffs

did indeed offer evidence that blacks fared less well

than whites on several socio-economic measures. Stip.

62-84. A witness offered as an expert in political

sociology then testified that the lower one's economic

status the less likely one is to participate in the

political process. R. 402.

Nothing in the record, however, supports the find

ing that participation by blacks in the electoral

process of North Carolina is depressed. Rather, the

whole record reflects vigorous participation by blacks

in every aspect of political activity. First of all, nearly

every one of the plaintiffs' own witnesses recited a

series of Democratic party offices, elective offices and

appointed political positions in which they had served.

See 11-12 sup1·a. The activities of just this small group

of people cast some doubts on any claim of either de

pressed participation or unequal opportunity. Wit

nesses for the plaintiffs also testified about successful

volunteer efforts by black leaders and civic groups to

30

increase voter registration. R. 463-64, 470. This too is

hardly reflective of a politically inactive black com

munity. Furthermore, the power wielded by such

organizations as the Durham Committee on the Af

fairs of Black People, R. 670, 1295, the Mecklenburg ·

Black Caucus, R. 453-55, the Raleigh-Wake Citizens

Association, R. 1333, the Black Women's Political Cau

cus, R. 1333, and the Wake County Democratic Black

Caucus, R. 1333-34, evidence a vital and sophisticated

black organization. Since the plaintiffs failed to prove

that political participation on the part of blacks in

North Carolina was depressed or in any way hindered,

the evidence of disparate economic and social status

was not particularly relevant to the issue of whether

the challenged legislative districts dilute black voting

strength and the court should have rejected this

evidence.

E. Racial appeals in political campaigns.

The court found that from Reconstruction to the

present racial appeals had been "effectively used by

persons, either candidates or their supporters, as a

means · of influencing voters in North Carolina politi

cal campaigns." J.S. 31a. The court apparently ac

cepted the opinions of plaintiffs' expert, Paul Luebke,

on this topic.'2 The Court lists 6 elections in which

these appeals supposedly were made:

12 Dr. Luebke's testimony was simply not cr edible . For example,

Luebke insisted that campaign slogans such as ''Eddie Knox will

serve all the people of Charlotte," and "Knox can unify this city,"

were racial slurs. R. 345. Most damaging to his credibility, how

ever, was his adamant refusal to admit that what might be a

racial appeal in the mind of one person could never be a fair

31

1950 Campaign for U.S. Senate

1954 Campaign for U.S. Senate

1960 Campaign for Governor

1968 ·Campaign for President

1972 Campaign for U.S. Senate

1984 Campaign for U.S. Senate

Of these 6 campaigns, 4 of them occurred more than

15 years ago. One more dates from more than 10

years ago. Only one of the so-called racial appeals

cited by the court occurred recently and it did not

occur in the context of an election to the General

Assembly in any · one of the challenged districts. Fur

thermore, the court's findings were based on Dr.

Luebke's opinions unsupported by any systematic

analysis or study. The same type of commentary on

racial appeals by a plaintiff's expert has been dis

missed by a district court as "pure sophistry." Over

ton v. City of Austin, No. A-84-CA-189 (N.D. Tex.

March 12, 1985) at 26. The court in Overton found

the methodology totally wanting because the expert

had not interviewed a statistically reliable sample of

voters to determine if they perceived any racial in

ferences in the campaign materials labelled "racial

appeals" by the expert. Id. at 27. Dr. Luebke's re

search consisted of reading the ads and determining

political comment in the mind of another. R. 417.

Dr. Luebke insisted, for example, that the white candidates for

the Durham County Board of Commissioners made racial appeals

throughout their campaign in 1980. R. 350-356. Luebke fou:c.d the

slogan, "Vote for Continued Progress," to be racially offensive.

R. 353-54. Nonetheless, two of the five seats in that election were

won by blacks and the 5 Commissioners then elected one of the

blacks Chairman of the County Board. R. 422-25.

32

whether they contained coded or "telegraphed" racial

messages. He interviewed no one to substantiate his

conclusions. R. 418-19.

F. The extent to which blacks have been elected.

Despite the considerable electoral success of blacks

in the challenged districts, the court found that" [t]he

overall results achieved to date at all levels of elective

o~ce are minimal in relation to the percentage of

blacks in the population." J.S. at 37a.13 This con

clusion is simply inapposite to the issue of whether

blacks enjoy equal political opportunity in the chal

lenged districts. In the 1982 elections, in the districts

in question, 11 black candidates offered for election.

Nine won in the Democratic primaries and seven

went on to win in the general elections. Three of the

four candidates who lost were running for public

office for the first time. The fourth losing candidate,

Howard Clement, testified that he lost because he did

not have the endorsement of the Durham Committee

on the Affairs of Black People, R. 1295, and indeed,

he received only a small percentage of the black vote.

The results of the 1982 legislative elections are hardly

consistent with a finding of "minimal" electoral

success.

G. Responsiveness.

The plaintiffs offered no evidence of unresponsive

ness but on cross-examination their witnesses con

ceded that their legislators were responsive to their

13 From the Court 's recitation of statistics at .J.S. 33a, it is clear

that this conclusion is based on the percentage of blacks elected

statewide, not in the challenged districts.

33

needs.14 R. 450-53. The defendants showed and the

court found that the effort to increase black regis

tration was directly responsive to the needs of the

black community. J.S. 25a. In addition, the court

specifically noted that the State has appointed a sig

nificant number of black citizens to judgeships and

to influential executive positions in state government.

J.S. at 47a. Despite the plethora of evidence offered

by the defendants, the court did not find that legis

lators generally were responsive or unresponsive: and

they did not examine the effect of this factor on

vote dilution. The failure to make such an assessment

reflects the court's underlying assumption that effec

tive representation of the minority community de

mands guaranteed election of minority candidates.

Apparently, the court interpreted "of their choice"

to mean "of their race." But there is simply no right,

constitutional or statutory, to elect representatives of

one's own race. Seamon v. Upham, Civil No. P-81-

49-CA (E.D. Tex. Jan. 30, 1984). See also Overton

v. City of Austin, No. A-84-CA-189 (W.D. Tex. March

12, 1985). Responsiveness is probative of the existence

of access to the political process because a white repre

sentative who responds to his black constituency is just

as effective, vis a vis the black community, as a black

person.

14 In the legislative session immediately preceding the trial, the

General Assembly greatly increased the availability of voter regis ·

tration. R. 1335. In addition, the budget included an allocation

for sickle cell anemia research, a holiday honoring Dr. Martin

Luther King was established, and local legislation changing the

method of election to the Wake County School Board from a dis

trict to an at-large system was passed at the urgmg of black

leaders from Wake County. R. 1333-38.

34

In its discussion of polarized voting in Rogers v.

Lodge, 458 U.S. 613 (1982), the Supreme Court noted

that when a racial majority can win all the seats in

an at-large election without the support of the mi

nority, it is possible for those elected to ignore the

views and needs of the minority with implmity. 458

U.S. at 616. When this occurs, the members of the

minority are essentially excluded from the democratic

process because they have no representative voice.

It is this very potential to shut blacks out of the

process without fear of political consequences which

makes unresponsiveness of elected officials one of the

indicia of a Section 2 violation. In the present case

blacks are not excluded from the process by · unre

sponsive white representatives. White candidates need

black support to win, and many black political organi

zations regularly endorse white candidates. R. 454-55,

464-65, 638, 855, 1234-36. Consequently white office

holders are held accountable by the black community.

Under these circumstances, the responsiveness of the

members of the General Assembly to the black citi

zenry further evidences the effective participation of

blacks in the political processes of North Carolina.

H. Legitimate state policy behind county·hased

representation.

The court found that the use of the whole-counties

as the building blocks of legislative districting was

"well-established historically, bad legitimate func

tional purposes, and was in its origins completely

without racial implications." J.S. at 50a. The court,

however, found this evidence irrelevant on the grounds

that the legislature could have contradicted estab

lished policy to avoid dilution of the black vote.

35

The court's analysis completely contorts the pur

pose for the presence of this factor in the Senate

Report. Evidence of a consistently applied, long

standing non-racial policy weighs against a finding

of vote dilution. As the Senate Report notes, a finding

on behalf of the State on this factor would not alone

negate other strong indications of dilution. N onethe

less, the court's basic finding refutes any suggestion

that the use of whole counties as the basic unit of

districting was racially motivated.

Based on the totality of circumstances, it is difficult

to comprehend how the court concluded that blacks.

in North Carolina have less opportunity than whites

to participate in the political process and to elect

candidates of their choice. The court's opinion seems

to turn upon its belief that although the evidence

proved that blacks could be elected, there vvas no

guarantee that blacks always would be elected from

the districts at issue.

Apparently the court thought that guaranteed ac

cess required guaranteed victory in as many single

member "safe" seats as could be drawn. The decision

removes black voters and candidates from the com

petitive electoral arena and protects them from the

vagaries of political fortune. Certainly Section 2 does

not require this.

II. Racially polarized voting is not established as a matter

of law whenever less than a majority of white voters vote

for a black candidate.

The district court identified racial bloc voting as

the "single most powerful factor in causing racial

vote dilution." J.S. 47a. In light of this emphasis,

36

it was essential to apply the proper legal definition

of racial bloc voting. The court, however, accepted

the opinion of the plaintiffs' expert that racially

polarized voting occurs whenever less than 50% of

the white voters cast a ballot for the black candidate.15

As a result, the court concluded that there was

"severe and persistent" racial bloc voting despite

the following facts:

a) In the 1982 Mecklenburg House primary, Berry

who is black received 50% of the white vote and

Richardson who is also black, received 39%. Berry re

ceived more votes than any other candidate. R. 189.

Both black candidates won the primary. R. 188-89;

Pl.Ex. 14(c), R. 85, 112.

b) In the 1982 House general election for Meck

lenberg County, 42% of the white voters voted for

Berry; 29% of the whites voted for Richardson. Pl.

Ex. 14(d), R. 86, 112. In a field of 18 candidates

for 8 seats, 11 white candidates received fewer white

votes than Berry. I d. In that election B erry finished

second, and Richardson finished ninth, only 250 votes

behind the eighth place winner.

1 5 The plaintiffs' expert, Bernard Grofmann, expressed his defini

tion of racial polarization in several ways. Basically, he opined that

racially polarized voting occurs when white voters and black voters

vote differently from one another . R. 50. Racial polarization is

substantively significant when the outcome would be different if

the election were held among only the black voters as compared to

only the white voters. R. 159. Thus a black candidate who would

be the choice of the black voters would have to get a majo ri ty of

the white vote to win in the hypothetical all-white constituency.

Thus Dr. Grofmann 's definition of substantively significan t racially

polarized voting can be reduced to this : it occurs whenever less

than a majority of the white voters vote for the black candidate.

R. 161.

37

c) In the 1982 House general election for Durham

County, black candidate Spaulding received 47% of

the white vote and won the election. R. 183-84, Pl.Ex.

16(e), R. 85, 112.

d) In the 1982 House primary election for Durham

County, one black candidate, Clement, received 32%

of the black vote and 26% of the white vote. R. 181-

82; Pl.Ex. 16(d), R. 86, 112. The black candidate

Spaulding received 90% of the black vote and 37%

of the white vote. I d. Of the two black candidates,

only Spaulding was successful in the primary. I d.

Had the black voters wanted to elect Clement, they

could have cast doubleshot votes. R. 184;

e) In the 1982 'Senate primary election for Meck

lenburg County, the black candidate, Polk, received

32% of the white vote and was successful in the

primary. Pl.Ex. 13 (j), R. 86, .112.

f) In the 1982 Mecklenburg Senate general elec

tion, Polk, a black candidate received 33% of the

white vote. The leading white candidate received 59 %

of the white vote. Pl.Ex. 13(k), R. 86, 112.

g) In the 1982 Forsyth House primary, the two

black candidates, Hauser and Kennedy, received 25%

and 36%, respectively, of the vote. Pl.Ex. 15 (e) . R.

86, 112. In a field of 11, Kennedy received more white

votes than six of those candidates. Pl.Ex. 15 (e), R. 86,

112. Both black candidates won the primary. I d.

h) In the 1982 House general election for Forsyth

County, Hauser and Kennedy received 42 % and 46%

respectively, of the white vote. R. 175-76; Pl.Ex. 15

(f), R. 86, 112. The successful white candidates re

ceived substantially equal support from black and

38

white voters-all within a range between 43% and

63%. Both black candidates were successful. I d.

i) In the 1982 House primary election for Wake

County, a six-member district, the only black candi

date running, Dan Blue, received more total votes

than any other of the 15 candidates. R. 194-95; Pl.Ex.

17(d), R. 86, 112. Blue received more white votes

than 11 of the other candidates. I d.

j) In the 1982 House general election for Wake

County, Blue ran second out of a field of 17 cancli

dates. R; 195, Pl.Ex. 17(e), R. 86, 112. Blue also

received the second highest number of white votes.

R. 196 ; Pl. Ex. 17 (e), R. 86, 112.

k) Although there have been relatively few black

republican candidates, and they have not been suc

cessful, these candidates have always received a

greater number of white votes than black votes. Pl.

Ex. 16 (f), R. 86, 112.

1) Finally, of the 11 elected black incumbents who

have sought reelection to the General Assembly in

recent years, all 11 have won reelection.16 R. 178.

The court's conclusion that these facts establish

polarized voting simply flies in the face of common

sense. In 1982 legislative elections in Durham, For

syth, Mecklenburg and Wake Counties, all of the

black candidates received between 25 and 50% of the

white vote. Of 8 Black Democratic candidates in these

counties, 5 were elected. These results do not "ap-

16 The court incorrectly found that " some black in cum bents were

reelected ... '' J.S. at 40a. Plaintiffs' own expert testified that all

black incumbents who had offered for reelection had been success

ful. R. 178.

39

proach any realistic legal standard of polarized vot

ing." Jones v. City of Lubbock, 730 F.2d 233 (5th

Cir. 1984) ·(reh'g en bane denied).

In Terrazas v. Clements, 537 F.Supp. 514 (N.D.

Tex. 1984), for example, the Court found that where

35% of the whites voted for the minority candidate,

there was no racial polarization. Similarly, in Collins

v. City of Norfolk, No. 83-526-N (E.D. Va. July 19,