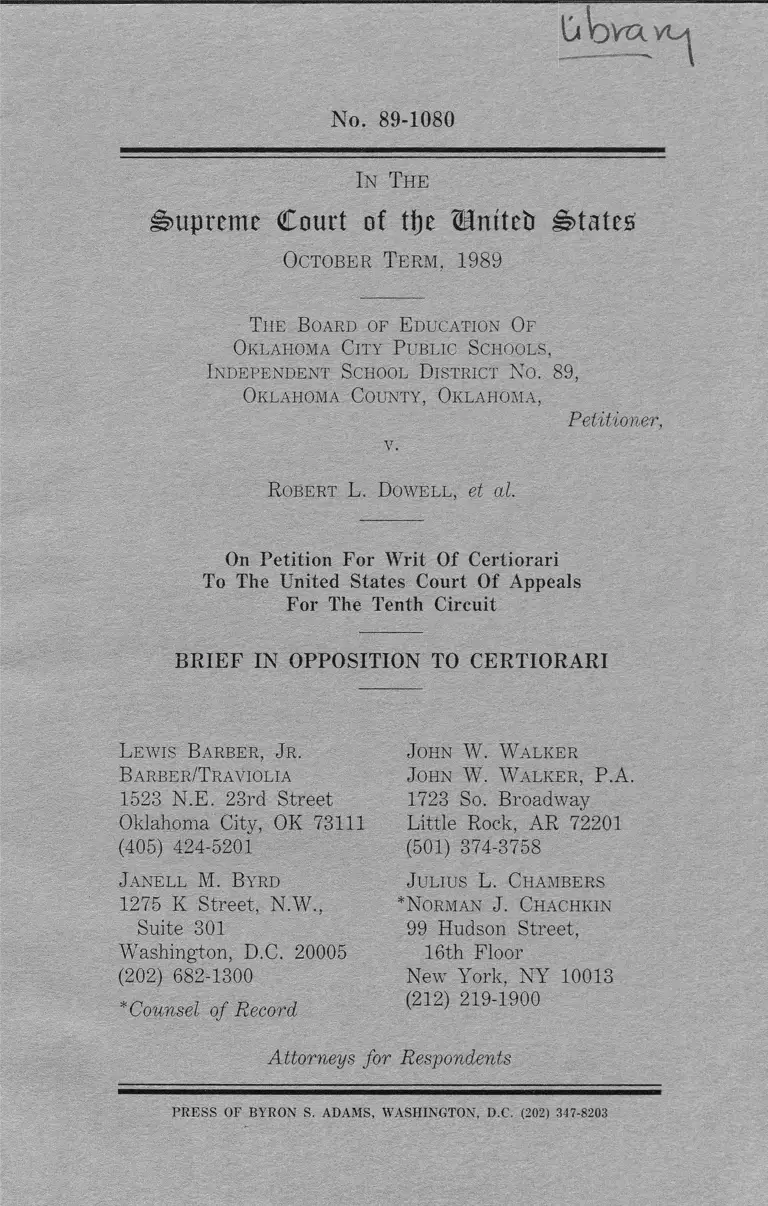

Oklahoma City Public Schools Board of Education v. Dowell Brief in Opposition to Certiorari

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1989

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Oklahoma City Public Schools Board of Education v. Dowell Brief in Opposition to Certiorari, 1989. 61323d39-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/16b89e2a-8be1-48f7-83d9-8fe0475d9abb/oklahoma-city-public-schools-board-of-education-v-dowell-brief-in-opposition-to-certiorari. Accessed March 10, 2026.

Copied!

No, 89-1080

In The

Supreme Court of tt)c Urutet) states

October Term, 1989

The Board of E ducation Of

Oklahoma City P ublic Schools,

Independent School District No. 89,

Oklahoma County, Oklahoma,

Petitioner,

v.

Robert L. Dowell, et al.

On P e tit io n F or W rit O f C ertiorari

To The U n ited S ta te s C ourt O f A p p ea ls

F or The T enth C ircuit

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI

Lewis Barber, J r.

Barber/Traviolia

1523 N.E. 23rd Street

Oklahoma City, OK 73111

(405) 424-5201

J anell M. Byrd

1275 K Street, N.W.,

Suite 301

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

* Counsel of Record

J ohn W. Walker

J ohn W. Walker, P.A.

1723 So. Broadway

Little Rock, AR 72201

(501) 374-3758

J ulius L. Chambers

*Nqrman J. Chachkin

99 Hudson Street,

16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

Attorneys for Respondents

PRESS OF BYRON S. ADAMS, WASHINGTON, D.C. (202) 347-8203

Counter-Statement of

Question Presented for Review

A single question arises on the facts of this case:

May a school district that obeys a federal court

order requiring it to implement a new student assignment

plan to accomplish desegregation be permitted, consistent

with the Fourteenth Amendment, to dismantle that plan,

and thereby to re-create the all-black schools whose

elimination was the purpose of the court order, when the

uncontroverted evidence demonstrates that the conditions

that made the order necessary (racial residential

segregation that the court determined to have resulted

from official state action including action of the school

authorities) yet persist?

- 1 -

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Counter-Statement of Question Presented

for Review .............................................. i

Table of Cases .......................... iii

Opinions Below ........................................... . 1

Statement 2

REASONS FOR DENYING THE WRIT . . . . 13

I. The Apparent Conflict Among the

Circuits Reflects Factual Differences

Limited to a Few Cases and Does

Not Warrant Review By This Court . . . . 13

II. The Court Below Properly Applied

The "Clearly Erroneous" Rule . . . . . . . . 25

III. On the Facts of This Case, the

Judgment Below Must Be Affirmed

Because the Board’s Pupil Assign

ment Plan Perpetuates the Racially

Discriminatory Effects of the

Dual System .......................... 29

Conclusion 40

Appendix (Order of January 18, 1977) la

Page

- ii -

Table of Cases

Page

Anderson v. Bessemer City, 470 U.S. 564

(1985) ___ . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25, 27, 28n

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294

(1955) 30n, 31

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954) 30n, 31

Columbus Board of Education v. Penick, 443

U.S. 449 (1979)...................................... .. 30n

Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman, 443

U.S. 526 (1979) . ...................... .. 28, 34

Dowell v. Board of Education, 396 U.S. 269

(1969) In, 3n

Dowell v. Board of Education, 890 F.2d 1483

(10th Cir. 1989)............ passim

Dowell v. Board of Education, 795 F.2d 1516

(10th Cir.), cert, denied, 479 U.S.

F.2d 1483 (10th Cir. 1989) . . . . . . . . . . passim

Dowell v. Board of Education, 677 F. Supp.

1503 (W.D. Okla. 1987), rev’d, 890

- iii -

Table of Cases (continued)

Page

Dowell v. Board of Education, 606 F. Supp.

1548 (W.D. Okla. 1985), rev’d, 795

F.2d 1516 (10th Cir.), cert, denied,

479 U.S. 938 (1986) --------. . . . . . . . 2n, 4n, 5n

Dowell v. Board of Education, 338 F. Supp.

1256 (W.D. Okla.), affd, 465 F.2d

1012 (10th Cir.), cert, denied, 409

U.S. 1041 (1972)............................... .. 2n, 3n, 3In

Dowell v. Board of Education, 307 F. Supp.

583 (W.D. Okla.), affd, 430 F.2d

865 (10th Cir. 1970) . .......................... ln~2n, 3n

Dowell v. Board of Education, 244 F. Supp.

971 (W.D. Okla. 1965), modified &

affd, 375 F.2d 158 (10th Cir.), cert,

denied, 387 U.S. 931 (1967) . . . . . . . In, 2n, 3n

Dowell v. Board of Education, 219 F. Supp.

427 (W.D. Okla. 1963) . . . . . . . . . . . In, 2n, 31n

Georgia State Conference of Branches of

NAACP v. Georgia, 775 F.2d 1403

(11th Cir. 1985) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20n

Jacksonville Branch, NAACP v. Duval

County School Board, 883 F.2d

945 (11th Cir. 1989)........................ 22n, 23n, 26n

- iv -

Table of Cases (continued)

Page

Keyes v. School District No. 1, 413 U.S.

Keyes v. School District No. 1, Nos. 85-2814

& 87-2364 (10th Cir. January 30,

1990), afPg 670 F. Supp. 1513 (D.

Colo. 1987) and 609 F. Supp. 1491

(D. Colo. 1985) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22n, 23n, 24n

Keyes v. School District No. 1, 670 F. Supp.

1513 (D. Colo. 1987), affd, Nos. 85-

2814 & 87-2634 (10th Cir. January

30, 1990) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . lOn

Lee v. Talladega County Board of Educa

tion, No. 88-7471 (11th Cir., argued

August 9, 1989) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14n

Lemon v. Bossier Parish School Board, 444

F.2d 1400 (5th Cir. 1971) . . . . . ___ _ . 21n

Monteilh v. St. Landry Parish School Board,

845 F.2d 625 (5th Cir. 1988) . . . . . . . . . 19

Morgan v. Nucci, 831 F.2d 313 (1st Cir.

1987) .............................................. 22n, 33n

Pasadena Board of Education v. Spangler,

427 U.S. 424 (1976) .................................. 32-33

- v -

Table of Cases (continued)

Page

Pitts v. Freeman, 755 F.2d 1423 (11th Cir.

Raney v. Board of Education of Gould,

391 U.S. 443 (1968).......................... .. 21n

Riddick v. School Board, 784 F.2d 521 (4th

Cir.), cert, denied, 479 U.S. 938

(1986) . . ................... .................. passim

School Board of Richmond v. Baliles, 829

F.2d 1308 (4th Cir. 1987) . . . . . . . . . . . 20n, 22n

Spangler v. Pasadena City Board of Educa

tion, 611 F.2d 1239 (9th Cir. 1979) ___ 25

Spangler v. Pasadena City Board of Educa

tion, 311 F. Supp. 501 (CD. Cal.

1970) .................................. .. 25n

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of

Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1 9 7 1 )___ 30n, 32, 33-34

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of

Education, Civ. No. 1974 (W.D.N.C.

July 11, 1975) ......................................... lOn

United States v. Henry, 709 F.2d 298 (5th

Cir. 1983) ............................................. 18n

- vi -

Table of Cases (continued)

Page

United States v. Lawrence County School

District, 799 F.2d 1031 (5th Cir.

(1986) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

United States v. Overton, 834 F.2d 1171

(5th Cir. 1987) ....... ............................

United States v. Swift & Company, 286

U.S. 106 (1932) . . . . . . . . . . . 11, 1

United States v. Texas [San Felipe del Rio

Consolidated School District], No.

89-1304 (5th Cir. December 6, 1989) .

United States v. Texas Education Agency,

647 F.2d 504 (5th Cir. 1981), cert,

denied, 454 U.S. 1143 (1982) . . . . . . .

Youngblood v. Board of Public Instruction

of Bay County, 448 F.2d 770 (5th

Cir. 1971) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. 20n, 22n

passim

1, 18, 24, 26

24n

22n

21n

- vn -

In the

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1989

No. 89-1080

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF

OKLAHOMA CITY PUBLIC SCHOOLS,

INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 89,

OKLAHOMA COUNTY, OKLAHOMA,

Petitioner,

v.

ROBERT L. DOWELL et al

ON PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE TENTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI

Opinions Below

The decision of the Court of Appeals, reprinted at

Pet. App. la-113a, is now reported at 890 F.2d 1483

(10th Or. 1989).1

1 Earlier reported opinions in this matter are found at 219 F.

Supp. 427 (W.D. Okla. 1963); 244 F. Supp. 971 (W.D. Okla. 1965),

(continued...)

Statement

The Oklahoma City school district for generations

maintained a racially discriminatory, dual and segregated

school system.1 2 In 1955 the school board eliminated

separate, overlapping attendance boundaries for black

and white students but because of segregated residential

patterns - which the district court in this case found to

have been caused by official action including the actions

of school authorities3 - the school zones which the board

drew perpetuated all-black, segregated schools in the

1 (...continued)

modified and affd, 375 F.2d 158 (10th Cir.), cert, denied, 387 U.S.

931 (1967); 396 U.S. 269 (1969); 307 F. Supp. 583 (W.D. Okla.),

affd, 430 F.2d 865 (10th Cir. 1970); 338 F. Supp. 1256 (W.D.

Okla.), affd, 465 F.2d 1012 (10th Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 1041

(1972); 606 F. Supp. 1548 (W.D. Okla. 1985), rev’d, 795 F.2d 1516

(10th Cir.), cert, denied, 479 U.S. 938 (1986).

2Dowell, 219 F. Supp. 427, 431-34 (W.D. Okla. 1963). [Earlier

reported opinions in this action are cited simply as "Dowell."]

zDoweU, 219 F. Supp. at 433-34; id., 244 F. Supp. 971, 975-76

(W.D. Okla. 1965); see also id , 677 F. Supp. 1503, 1506 (W.D. Okla.

1987), rev’d, 890 F.2d 1483 (10th Cir. 1989), P et App. 5b-6b.

- 2 -

"northeast quadrant" of the city.4 In 1972, after the

board failed to submit an effective plan,5 the district

court ordered the system to implement the "Finger Plan"

utilizing pairing and clustering of school facilities to

desegregate the public schools.6

In 1977 the district court "terminated" its

supervisory jurisdiction but did not vacate its 1972 order,

specifically noting that "the Court does not foresee that

the termination of its jurisdiction will result in the

dismantlement of the [Finger] Plan."7 However, in 1984

ADowell, 244 F. Supp. at 975.

5The trial court repeatedly allowed the school board additional

time to submit an effective desegregation plan. See Dowell, 244 F.

Supp. 971 (W.D. Okla. 1965), modified and ajfid, 375 F.2d 158 (10th

Cir.), cert denied, 387 U.S. 931 (1967); id , 396 U.S. 269

(1969)(reversing delay in implementing secondary plan); id , 307 F.

Supp. 583 (W.D. Okla.), ajfid, 430 F.2d 865 (10th Cir.

1970)(approving secondary plan).

6Dowell, 338 F. Supp. 1256 (W.D. Okla.), ajfid, 465 F.2d 1012

(10th Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 2041 (1972).

7The 1977 order is reprinted infra, Appendix pp. la-4a.

- 3 -

the school board decided to return the system’s

elementary schools to the geographic attendance zoning

system it had devised in 1955. The result was the

creation of ten elementary schools having virtually all

black enrollments (each of which had been virtually all

black prior to the 1972 order and each of which had

been integrated from 1972 to 1984), to which more than

40% of all black elementary students in the Oklahoma

City public schools were assigned.8

Plaintiffs sought to reopen the litigation to

challenge this elementary school resegregation. The

district court denied plaintiffs’ request and held the 1984

elementary attendance plan constitutional,9 but the Court

of Appeals reversed and remanded with instructions that

8See Dowell, 890 F.2d at 1511 n.5 (dissenting opinion). The

eleventh virtually all-black elementary school, North Highland, was

50% black in 1972, PX 12, Tr. [of June 15-24, 1987 hearing] 30, 32.

9Dowell, 606 F. Supp. at 1557.

- 4 -

the trial court should consider whether the 1972

injunction should be modified or dissolved, placing the

burden upon the school board to "present evidence that

changed conditions require modification or that the facts

or law no longer require the enforcement of the order."10

On remand, the school board

assert[ed] that over time the substantial

demographic changes in Oklahoma City rendered

the Finger Plan inequitable and oppressive. The

resulting inequity, the Board contended], was the

primary factor motivating its adoption of the new

student assignment plan at the elementary level.11

The board also claimed that as a result of these changes,

current residential patterns in the district no longer

reflected the impact of the severe, interrelated housing

and school segregation that the Finger Plan was intended

10Dowell, 795 F,2d at 1523.

1 "'Dowell, 606 F. Supp. at 1513, P et App. 19b.

- 5 -

to neutralize.12 These changes, the board contended,

warranted the complete dissolution of injunctive relief.

The district court agreed with these contentions.

It concluded that although the 1984 plan re-instituted the

same attendance zones that had been used prior to the

1972 order,13 and although it re-created the very same

all-black elementary schools in the "northeast quadrant"

of Oklahoma City that had existed prior to that order,

nevertheless there was no re-establishment of the dual

school system. The court reached this judgment by

making two findings. It first "unlink[ed] the Board from

existing residential segregation,"14 holding the

^"Defendants’ expert . . . was satisfied that the residential

pattern that developed in the District since implementation of the

Finger Plan was not a vestige of what had occurred thirty-five or

forty years before," Dowell, 890 F.2d at 1487.

13Dowell, 677 F. Supp. at 1517, Pet. App. 28b.

14Dowell, 890 F.2d at 1488, Pet. App. 9a.

- 6 -

discriminatory acts that it had earlier recognized as the

cause of pre-1972 residential racial separation15 had

become attenuated as a result of the repeal of

discriminatory statutes and ordinances and the passage of

fair housing legislation.16 The court then concluded that

the board’s adoption of the 1984 plan was not motivated

by "discriminatory intent."17

Turning to the question whether the injunction

should be dissolved or modified, the district court held

that the purposes of the 1972 order had been achieved

since

the school district’s continued adherence to the

fundamental tenets of the Finger Plan at all grade

levels through school year 1984-85 further insured

15See supra note 3.

1 &Dowell, 677 F. Supp. at 1511, Pet. App. 15b.

17Dowell, 677 F. Supp. at 1516, PeL App. 25b.

- 7 -

that all vestiges of prior state-imposed segregation

had been completely removed18 19

and since

the Oklahoma City Board o f Education is not

responsible for the present state o f residential

segregation in Oklahoma City}9

The court below again reversed. It held that the

district court "clearly erred in its findings of fact and

consequent legal determinations":

[Although there is evidence to facially support the

district court’s findings, on the entire evidence we

are "left with the definite and firm conviction that

a mistake has been committed." United States v.

United States Gypsum Co., 333 U.S. 364, 395

(1948). Because the court failed to address or

distinguish plaintiffs’ contrary evidence, and

because the court cast the evidence on which it

relied in a form to provide an answer to the single

question of discriminatory intent, we are convinced

18Dowell, 677 F. Supp. at 1522, Pet. App. 38b.

19Dowell, 677 F. Supp. at 1521, Pet. App. 36b [emphasis in

original].

- 8 -

that the basis on which the court fashioned

dissolution of the injunction was flawed.20

The starting point for the Court of Appeals’

analysis was its recognition that, although the district

court used the term ’’unitary" to describe the Oklahoma

City school system in 1977 (at a time when the Finger

Plan was still being fully implemented), it had not at that

time vacated the 1972 injunction but simply terminated

its active jurisdiction over the case.21 In those

20Dowell, 890 F.2d at 1504, P et App. 41a [emphasis in

original]. At the beginning of its opinion (890 F.2d at 1488, Pet

App, lOa-lla), the panel majority enunciated the standard of review’

which it was applying:

[0]ur review focuses on whether the district court abused its

discretion in granting the Board’s motion to dissolve the

injunction and denying plaintiffs’ motion to modify the

relief. On appeal we will not disturb the-district court’s

determination except for an abuse of discretion. Securities

and Exch. Comm’n v. Blinder, Robinson & Co., Inc., 855 F.2d

677 (10th Cir. 1988). The district court’s exercise of

discretion, however, must be tethered to legal principles and

substantial facts in the record. Evans v. Buchanan, 582 F.2d

750, 760 (3d Cir. 1978), cert denied, 446 U.S. 923 (1980).

21 The district court’s action was thus similar to measures

adopted by other courts to provide a greater degree of discretion for

(continued...)

- 9 -

circumstances, as the Court of Appeals had previously

held, the school board was entitled to dissolution of

injunctive relief only upon a showing that "the law or the

?1(...continued)

local school boards while retaining protections for the rights of

plaintiffs. E.g., Keyes v. School District No. 1, 670 F. Supp. 1513,

1515 (D. Colo. 1987)(court "recognized the need for modification of

the existing court orders to relax court control and give the

defendants greater freedom to respond to changing circumstances

and developing needs in the educational system"), tiff’d, Nos. 85-

2814 & 87-2634 (10th Cir. January 30, 1990); Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Board o f Education, Civ. No. 1974 (W.D.N.C. July 11,

1975), slip op. at 2 ("This case contains many orders of continuing

effect, and could be re-opened upon proper showing that those

orders are not being observed. The court does not anticipate any

action by the defendants to justify a re-opening; does not anticipate

any motion by plaintiffs to re-open; and does not intend lightly to

grant any such motion if made. This order intends therefore to

close the file; to leave the constitutional operation of the schools to

the Board, which assumed that burden after the latest election; and

to express again a deep appreciation to the Board members,

community leaders, school administrators, teachers and parents who

have made it possible to end this litigation").

The 1977 order in this case included no finding that all

vestiges of prior discrimination had been completely eliminated. It

stated only that "substantial compliance with the constitutional

requirements has been achieved," adding that the court did not

expea that relinquishing aaive jurisdiaion "will result in the

dismantlement of the Plan or any affirmative aaion by the defendant

to undermine the unitary system so slowly and painfully

accomplished over the 16 years" of the litigation." See infra, pp. la-

4a.

- 10 -

underlying facts have so changed that the dangers

prevented by the injunction ‘have become attenuated to

a shadow.’" Dowell, 890 F.2d at 1489-92 and 795 F.2d at

1521, both citing United States v. Swift & Company, 286

U.S. 106 (1932).

Although there were changed conditions,22 the

court below concluded that they did not warrant

dissolution of all injunctive relief:

The issue then becomes whether the Board’s

action in response to the changed conditions has

the effect of making the District 'toi-unitary" by

reviving the effects of past discrimination. . . .

[T]he evidence indicates the Board’s

implementation of a "racially neutral"

neighborhood student assignment plan has the

effect of reviving those conditions that necessitated

a remedy in the first instance. Under these

circumstances the expedient of finding unitariness

does not erase the record or represent that

substantial change in the law or facts to warrant

overlooking the effect of the Board’s actions.23

22Dowell, 890 F.2d at 1498, Pet. App. 30a.

Dowell, 890 F.2d at 1499, P et App. 31a-32a.

- 11 -

Instead, the case was remanded with instructions to

modify prior decrees in light of the changed

circumstances and of the objectives they were intended

to achieve.24 It is that determination which the board

now asks this Court to review.

2ADowell, 890 F.2d at 1504-06, P et App. 41a-45a.

- 12 -

REASONS FOR DENYING THE WRIT

L THE APPARENT CONFLICT AMONG

THE CIRCUITS REFLECTS FACTUAL

DIFFERENCES LIMITED TO A FEW

CASES AND DOES NOT WARRANT

REVIEW BY THIS COURT

This matter, Riddick v. School Board,25 and United

States v. Overton26 are sui generis, as we explain below.

Since the time in the mid-198Q’s when they were initially

litigated, their unique circumstances have not recurred in

other suits. For this reason, any apparent conflict among

the Courts of Appeals in these decisions does not

warrant review by this Court, especially since there is

broad consensus in the lower courts on the underlying

substantive principles.

25784 F.2d 521 (4th Cir.), cert denied, 479 U.S. 938 (1986).

26834 F.2d 1171 (5th Cir. 1987).

- 13 -

In each of the three enumerated cases, a federal

district court had, at some point in the past, used the

term "unitary" to describe the school district involved.27

In each of the cases, the school system in question

27In Riddick the finding was embodied in a consent decree

dismissing the predecessor school desegregation action "with leave to

any party to reinstate this action for good cause shown.” See 784

F.2d at 525. In Overton the parties entered into a consent decree

providing that after three years, unless there was objection the

school district "shall be declared to be a unitary school system and

this case shall be dismissed." See 834 F.2d at 1171. (There was

such an objection but it was withdrawn pursuant to a further

stipulation, thus triggering dismissal pursuant to the consent decree

when the stipulation was effectuated. Id. at 1173-74.) In Dowell, as

we have noted, the word was used in one sentence of a 1977 order

terminating active jurisdiction but not referring to or vacating prior

injunctive decrees.

In the only other arguably similar case of which

Respondents are aware, Lee v. Talladega County Board o f Education,

No. 88-7471 (11th Cir. argued August 9, 1989), the district court in

1985 endorsed as "Approved" and "Entered" a Joint Stipulation of

Dismissal signed by all parties. The Joint Stipulation incorporated

by explicit reference a resolution of the school board in which it

committed itself to continue to comply with all prior court orders in

the case. On the same date, the district court entered a separate

Judgment and Order dismissing the case "in view o f the Stipulation

and reciting that the district had achieved "unitary status." Neither

the Joint Stipulation nor the Judgment and Order vacated or

dissolved prior orders. The present appeal in that matter turns on

construction of the Order, the Stipulation and the incorporated

resolution.

- 14 -

thereafter dismantled, in its elementary grades, the

desegregation plan that it had previously been ordered to

implement, and that had made it possible even to

consider application of the term "unitary” to its public

schools. The issue presented to the federal courts in the

renewed litigation which followed was whether such

dismantling was consistent with the Fourteenth

Amendment obligations of school authorities that had

originally prompted the issuance of desegregation

injunctions.

The Courts of Appeals reached different results in

the cases. In Overton and Riddick the parties’ consent to

the "unitary" finding was treated as controlling and as the

equivalent of a judgment that all vestiges and effects of

the school authorities’ prior discriminatory conduct had

- 15 -

been completely eliminated.28 In Dowell the Court of

Appeals did not view the "unitary" phrasing of the 1977

order in the same light; although the plaintiffs had not

appealed the entry of the 1977 order and it was

therefore to be given res judicata effect,29 the Court of

Appeals found the failure of the district court to have

explicitly vacated its prior decree in 1977 to be quite

significant.30 Since the 1972 order remained in effect, the

Court held, it could subsequently be dissolved only upon

28In Riddick the consent order recited "that racial

discrimination through official action has been eliminated from the

system, and that the Norfolk School System is now ‘unitary,’" see 784

F.2d at 521. In Overton the consent decree embodied the minimum

three-year period of retained jurisdiction, and the opportunity for

plaintiffs to make objection and present evidence of continued

vestiges of discrimination counter-indicating dismissal, that the Fifth

Circuit had previously established as the proper procedure to be

followed in ending school desegregation suits. See 834 F.2d at 1175

n.12, 1177 n.20 & accompanying text.

29Dowell, 795 F.2d at 1522.

30As noted, the district court had stated in 1977 that it did not

expect its termination of active jurisdiction to result in any

dismantling of the Finger Plan.

- 16 -

a showing, consistent with the traditional equity standards

enunciated in Swift, that the conditions which gave rise to

its entry in 1972 had so changed that its continuance was

no longer necessary to ensure the constitutional rights of

the plaintiffs for whose protection it had issued.

Petitioners advance a conflict among the Circuits

with respect to the significance of a "unitary" finding and

with respect to the applicability of the Swift standard as

matters meriting the attention of this Court. We

respectfully submit, however, that the judgments in the

three cases are not mutually inconsistent, and that there

is now, in fact, wide agreement among the lower federal

courts on the governing legal principles in this area.

Accordingly, discretionary review of the decision below is

unnecessary.

In Riddick and Overton the plaintiffs’ consent (or

withdrawal of objections) to determinations that the

- 17 -

effects of prior discrimination had been eliminated was

held controlling, as previously noted. In Dowell the

Court of Appeals was unable to harmonize the district

court’s incidental use of the term "unitary” with its failure

to dissolve the prior injunctive relief, and for this reason

held that the injunction remained in force and could only

be vacated on the basis of the traditional Swift showing.

While the Overton court, in dictum,31 expressed

disagreement with Dowell, that disagreement turned upon

the Overton panel’s assumption that the 1977 order in the

instant case was "a final declaration that the school

31 The first reason given by the Court of Appeals in Overton for

upholding the district court’s refusal to enforce the prior consent

decree was that the decree "expired by its own terms." 834 F.2d at

1174. Since that was a completely sufficient basis on which to

affirm the district, court’s judgment, the subsequent discussion of

Riddick and Dowell in the opinion was unnecessary and is dictum -

especially since the panel’s interpretation of the consent decree’s

terms avoided the need to decide issues of constitutional magnitude

concerning the scope and duration of the remedy for operating a

dual school system. See United States v. Henry, 709 F.2d 298, 310

(5th Cir. 1983) ("It is well settled . . . that a federal court should not

reach a constitutional question if the case may be disposed of on

statutory or other nonconstitutional grounds").

- 18 -

district [was] unitary."32 On strikingly similar facts,

however, the author of the Overton opinion has

recognized that the mere usage of the word "unitary"

does not always constitute such a "final declaration that

the school district is unitary." See Monteilh v. St. Landry

Parish School Board, 845 F.2d 625, 629 (5th Cir.

1988)(',because our procedures had not been followed

before the court in 1971 declared St. Landry to be

unitary, we find that neither the district court nor the

panel affirming its order intended to declare that the

district was unitary, in the sense of having eliminated all

vestiges of past discrimination").

The same approach, involving fact-bound analysis

of the history of an action rather than the attribution of

talismanic significance to the word "unitary," has been

taken in numerous cases decided by several of the

Z2See 834 F.2d at 1174.

- 19 -

the Eleventh Circuit aptly summarized the situation:

Some confusion has been generated by the failure

to adequately distinguish the definition of a

"unitary" school system from that of a school

district which has achieved "unitaiy status." As

used in this opinion, a unitary school system is one

which has not operated segregated schools as

proscribed by cases such as Swann and Green for

a period of several years. A school system which

has achieved unitary status is one which is not

only unitary but has eliminated the vestiges of its

prior discrimination and has been adjudicated as

such through the proper judicial procedures.33 34

federal judicial Circuits.33 As the Court of Appeals for

33E.g., School Board of Richmond v. Baliles, 829 F.2d 1308,

1311 n .l (4th Cir. 1987)("We recognize that there is dictum in our

1972 opinion stating that this was a unitary system. That issue,

however, was not properly before the appeals court in 1972 and, as

explained by the district court in the instant litigation, the facts in

1972 might not have supported a finding that RPS had achieved

unitary status at that time"); Unued States v. Lawrence County School

District, 799 F.2d 1031, 1037 (5th Cir. 1986)(The use of the word

‘unitaiy in the Alexander opinion, like its repetition in the 1974

order, did not imply a judicial determination that the school system

had finally and fully eliminated all vestiges of de jure segregation");

Pitts v. Freeman, 755 F.2d 1423, 1426 (11th Cir. 1985)("As the

defendants suggest, it is possible that the district court did not

intend its use of the word ‘unitary to be equated with the unitary

status that requires dismissal of the action").

34Georgia State Conference o f Branches o f NAACP v. Georgia,

775 F.2d 1403, 1413 n.12 (11th Cir. 1985). What had always been

(continued...)

- 20 -

Thus, the conflict between Riddick and Overton,

on the one hand, and the instant case, on the other,

turns not upon the consequences of a true determination

of "unitary status" but upon the differing interpretations

given by the Courts of Appeals in each case to the

earlier orders in which the term "unitary1' was used.

No legal issue warranting the grant of certiorari

here is presented by such case-specific differences in

interpretation of lower court orders. Since the Courts of

Appeals’ 1986 and 1987 decisions in the three cases, no

other school systems have sought to dismantle their

desegregation plans. And there is virtual unanimity

^(...continued)

clear was that premature dismissal of cases, before it was clear that

plans had been effective and the vestiges of discrimination had been

eradicated, was improper. Raney v. Board o f Education o f Gould,

391 U.S. 443, 449 (1968); Youngblood v. Board o f Public Instruction

of Bay County, 448 F.2d 770 (5th Cir. 1971); see also Lemon v.

Bossier Parish School Board, 444 F.2d 1400, 1401 (5th Cir. 1970).

- 21 -

among the lower federal courts today35 about the

35See Keyes v. School District No. 1, Nos. 85-2814 & 87-2364

(10th Cir. January 30, 1990), slip op. at 13-14 (’This court has

defined ‘unitary’ as the elimination of invidious discrimination and

the performance of every reasonable effort to eliminate the various

effects of past discrimination"); Jacksonville Branch, NAACP v. Duval

County School Board, 883 F.2d 945, 951-52 (11th Or. 1989)(Supreme

Court "cases make clear that no previously segregated school system

can be declared to have achieved unitary status as long as there is

continued segregation . . . . A declaration of unitary status is also

inappropriate when the evidence shows that school authorities have

not consistently acted in good faith to implement the objectives of

the plan"); School Board o f Richmond v. Bodies, 829 F.2d at 1312

(affirming district court finding of unitary status after considering

evidence on factors "other than those relating to student body

composition or school operations" that parties had urged district

court to consider in addition to the six factors enumerated in

Green); Morgan v. Nucci, 831 F.2d 313, 321 (1st Cir. 1987)("Unitary

status is not simply a mathematical construction. One non-

quantitative factor of particular significance is whether the school

defendants have a sufficiently well-established history of good faith

in both the operation of the educational system in general and the

implementation of the court’s student assignment orders in

particular to indicate that further oversight of assignments is not

needed to forestall an imminent return to the unconstitutional

conditions that led to the court’s intervention"); United States v.

Lawrence County School District, 199 F.2d at 1037 (T h e use of the

word ‘unitary’ in the Alexander opinion, like its repetition in the

1974 order, did not imply a judicial determination that the school

system had finally and fully eliminated all vestiges of de jure

segregation . . . Because the potential consequences of a judicial

declaration that a school system has become unitary are significant,

this court has required district courts to follow certain procedures

before declaring a school system unitary"); United States v. Texas

Education Agency, 647 F.2d 504, 508-09 (5th Cir. 1981), cert denied,

454 U.S. 1143 (1982).

- 22 -

underlying substantive principle: that a school district

which had been made subject to a desegregation order

should be found to have attained "unitary status,"

entitling it to a dismissal, only a careful hearing and

review of all aspects of its operations to insure that all

vestiges of prior discrimination have been extirpated.36

In light of that understanding, and of the collateral

consequences which have, after Riddick, flowed from a

"unitary" finding, the label is no longer lightly applied to

a district, and determinations of "unitariness" are often

contested and are subject to careful scrutiny.37

P etitio n ers do not contest that standard; rather, they contend

that they meet it. The court below overturned the district court’s

finding that the school system was "unitary" after implementation of

the elementary plan adopted in 1984 as "clearly erroneous," a matter

we address infra in Argument II.

37See, e.g., Jacksonville Branch, NAACP v. Duval County School

Board, 883 F.2d at 953 (reversing district court’s "unitariness" finding

as clearly erroneous); Keyes v. School District No. 1, Nos. 85-2814 &

87-2634 (10th Cir. January 30, 199Q)(affirming finding of district court

(continued...)

- 23 -

Nor does any meritorious issue arise from the

articulation, by the court below, of the Swift standard to

govern dissolution of school desegregation decrees.37 38 A

proper finding of "unitary status," signifying that all

vestiges of prior discrimination have been eliminated, by

definition meets the Swift standard because it

encompasses a determination that there are no lingering

effects of the prior violation that might cause its

recurrence if injunctive relief is vacated. The Swift

standard thus does not extend "a federal court’s

37 (...continued)

that district was not "unitary" as to student assignments), ajftg 609 F.

Supp. 1491 (D. Colo. 1985); United States v. Texas [San Felipe del

Rio Consolidated School District], No. 89-1304 (5th Cir. December 6,

1989) [unpublished] (affirming district court finding that school system

had achieved unitary status).

38The Tenth Circuit has approved modification of a decree

based on criteria other than the Swift standard. Keyes v. School

District No. 1, Nos. 85-2814 & 87-2634 (10th Cir. January 30, 1990),

slip op. at 22 (endorsing "interim decree" as "commendable attempt

to give the board more freedom to act within the confines of the

law"), afftg 670 F. Supp. 1513 (D. Colo. 1987).

- 24 -

regulatory control of [public school] systems . . . beyond

the time required to remedy the effects of past

intentional discrimination,'1 Spangler v. Pasadena City

Board o f Education, 611 F.2d 1239, 1245 n.5 (9th Cir.

1979) (Kennedy, J., concurring).39

IL THE COURT BELOW PROPERLY APPLIED

THE "CLEARLY ERRONEOUS" RULE

Petitioners suggest that the decision of the court

below conflicts with the ruling in Anderson v. Bessemer

City, 470 U.S. 564 (1985) and misapplies the "clearly

erroneous" rule. However, the features of the Court of

Appeals’ analysis in Anderson which led this Court to

39In Spangler, "the evidence presented to the district court in

support of the motion for termination of jurisdiction showed that

the effects of the Board’s pre-1970 discrimination have been

eliminated," id at 1243 (Kennedy, J., concurring). Unlike in the

present case, the district court in Spangler had never made a finding

that the school board’s discriminatory student assignment and

transfer practices had contributed to racial residential segregation in

the school district See Spangler, 311 F. Supp. 501, 507-13 (CD.

Cal. 1970).

- 25 -

grant review and to reverse the ruling in that case are

not present in the instant matter.

To begin with, Petitioners are incorrect in their

assertion that the court below "struck down the district

court’s intent finding" (Pet. 25). Rather the court

examined the evidence "to decide if the district court

correctly found the Plan maintained unitariness E4°3 in

student assignments" and "on this basis . . . conclude[d

that] the district court clearly erred in its findings of fact

and consequent legal determinations."* 41 The inquiry

conducted by the court below was consistent with its

application of the Swift standard to the question whether

40nA declaration that a school has achieved unitary status is a

finding of fact subject to review under the clearly erroneous

standard. United States v. Texas Educ. Agency, 647 F.2d 504, 506

(5th Or. Unit A 1981), cert denied, 454 U.S. 1143 (1982); accord

Riddick v. School BcL, 784 F.2d 521, 533 (4th Cir. 1986).”

Jacksonville Branch, NAACP v. Duval County School Board, 883 F.2d

at 952 n.3.

41890 F.2d at 1503-04, Pet. App. 40a-41a.

- 26 -

the injunction should have been dissolved by the district

court in 1987 and focused on the question whether

vestiges of the prior discrimination remained intact.42

Unlike Anderson, where the Court of Appeals

effectively substituted its own credibility determination for

that of the district court in intepreting the testimony of a

witness,43 or drew a different inference than the district

court from the subsidiary facts on which the district court

relied,44 here the panel majority found the district court’s

"unitariness" finding wanting because it was based upon

an incomplete view of the uncontroverted facts established

by the record and because it was substantially shaped by

42See Dowell, 890 F.2d at 1493 n.19 ("the question of continued

unitariness of the District . . . was the key factual controversy in this

case. . . . Whether the District was unitary before circumstances

changed is irrelevant to whether the decree should be amended or

vacated. Indeed, whether the District remains unitary in light of

changed circumstances is a wholly different question").

43Anderson, 470 U.S. at 577-79.

44IdL at 576-77.

- 27 -

the lower court’s view that controlling legal significance

was to be accorded the board’s intent in adopting the

1984 plan.45 This holding by the majority below is

unexceptionable. Dayton Board o f Education v. Brinkman

[Dayton II], 443 U.S. 526, 534-37 (1979).

Petitioners and the dissenting member of the

panel fundamentally mischaracterize the basis of the

ruling below in suggesting that the majority disagreed

with the district court’s choice between "two permissible

views of the evidence."46 That is not what the panel

majority meant by its statement that "there is evidence to

facially support the district court’s findings."47 When that

language is read in the context of the remainder of the

sentence in which it appears, and of the following textual

A5See Dowell, 890 F.2d at 1503-04, P et App. 41a.

P e t it io n at 25, citing Anderson, 470 U.S. at 574.

47Dowell, 890 F.2d at 1504, P et App. 41a [emphasis added].

- 28 -

sentence,48 the meaning is evident: a selective view of the

record evidence, as recited and referenced in the district

court’s opinion was not antithetical to its finding, but

considering the "entire evidence," the finding was clearly

erroneous. No question warranting the grant of certiorari

is raised by the holding of the court below.

HI. ON THE FACTS OF THIS CASE, THE

JUDGMENT BELOW MUST BE AFFIRMED

BECAUSE THE BOARD’S PUPIL

ASSIGNMENT PLAN PERPETUATES

THE RACIALLY DISCRIMINATORY

EFFECTS OF THE DUAL SYSTEM

Even if the legal issues raised by Petitioners

appeared to be more significant than they are, this case

would be an inappropriate vehicle in which to explore

them. The record evidence in this action compels the

conclusion that the school board’s 1984 elementary-grade

48The passage is set out supra at pp. 8-9.

- 29 -

pupil assignment plan, re-imposing pre-1972 geographic

attendance zones, perpetuates the racially discriminatory

effects of the dual school system whose elimination is the

goal of this lawsuit. Under these circumstances, the

district court’s finding of "unitariness" is inconsistent with

this Court’s school desegregation jurisprudence from

Brown49 to Swann,50 Keyes,51 and Columbus52

A. The ten virtually all-black schools reestablished

by the school board’s 1984 plan are the same schools

that were identified by the district court in 1972 as

"substantially disproportionate in their racial composition,"

as not having "lost their racial identity" and as indicating

^Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954); id , 349

U.S. 294 (1955).

^Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board o f Education, 402 U.S.

1 (1971).

5 ̂Keyes v. School District No. 1, 413 U.S. 189 (1973).

52Columbus Board o f Education v. Penick, 443 U.S. 449 (1979).

- 30 -

that "the dual system of the School District remains

unaffected."53 These and other schools for black children

that were operated under the dual system were "centrally

located in the Negro section of Oklahoma City,

comprising generally the central east section of the

city."54 Thus the 1984 plan reestablished the pattern of

de jure segregation in the same place and by the same

method that existed prior to the district court’s 1972

order.55 It is utterly illogical and at war with the

principles of the Brown decision to permit a school

district, that for generations maintained a racially dual

school system, to revert to the same method of operating

53Dowell, 338 F. Supp. at 1260, 1265. [Harmony Elementary

School was renamed King Elementary School in 1974-75.]

54Dowell, 219 F. Supp. at 433-34. See Swann, 402 U.S. at 21.

55The present case is therefore distinguishable from Riddick, in

which the new plan’s "attendance zones were gerrymandered so as to

achieve maximum racial integration," 784 F.2d at 527.

- 31 -

virtually all-black schools built in pursuance of that dual

school system.

It is one thing to say, as this Court did in Swann,

that when a district court has required implementation of

an effective desegregation plan, further modification by

the court should not be necessary "in the absence of a

showing that either the school authorities or some other

agency of the State has deliberately attempted to fix or

alter demographic patterns to affect the racial

composition of the schools."56 It is quite another to read

this language, as do Petitioners, to insulate school boards

completely from any responsibility for resegregation that

accompanies deliberate board action dismantling that

plan. See Pasadena Board o f Education v. Spangler, A ll

^ 402 U.S. at 32.

- 32 -

U.S. 424, 435-36 (1976).57 Indeed, this Court’s decisions

have explicitly charged school boards and district courts

with the responsibility for avoiding resegregative actions:

In Swann, the Court referred to "the classic pattern of

building schools specifically intended for Negro or white

students" as a "factor of great weight"; and cautioned that

in remedying the constitutional violation of official

segregation,

57In Pasadena, this Court said:

There was also no showing in this case that those post-

1971 changes in the racial mix of some Pasadena schools

which were focused upon by the lower courts were in any

manner caused by segregative actions chargeable to the

defendants. . . . [A] quite normal pattern of human

migration resulted in some changes in the demographics of

Pasadena’s residential patterns, with resultant shifts in the

racial makeup of some of the schools. But as these shifts

were not attributed to any segregative actions on the part of

the petitioners, we think this case comes squarely within the

sort of situation foreseen in Swann.

Accord Morgan v. Nucci, 831 F.2d 313 (1st Cir. 1987)(vacating order

under which "school defendants will be required for an indefinite

period to maintain specific racial mixes in the city’s schools, much

like the balances they have been required to achieve during the 12

years in which the district court actively controlled the desegregation

process” by altering assignments each year to attain targeted

enrollment ratios, id. at 317 n.3).

- 33 -

it is the responsibility of local authorities and

district courts to see to it that future school

construction and abandonment are not used and

do not serve to perpetuate or re-establish the dual

system.58

And in Dayton II, the Court repeated that school boards

that previously operated dual school systems had "an

affirmative responsibility to see that pupil assignment

policies and school construction and abandonment

practices ‘are not used and do not serve to perpetuate

or re-establish the dual school system.’"59

The court below faithfully applied the teaching of

this Court’s decisions in refusing to endorse the board’s

resegregative 1984 elementary school plan, and review by

this Court of its determination is unnecessary.

58402 U.S. at 21.

59443 U.S. at 538 (emphasis added and citation omitted).

- 34 -

B. As if recognizing these principles, Petitioners

and the district court60 sought to establish that Oklahoma

City school officials’ past discrimination had "become so

attenuated as to be incapable of supporting a finding of

de jure segregation warranting judicial intervention."61

See Petition at 9. As this Court framed the inquiry in

Keyes, 413 U.S. at 211:

[A] connection between past segregative acts and

present segregation may be present even when not

apparent and . . . close examination is required

before concluding that the connection does not

exist. Intentional school segregation in the past

may have been a factor in creating a natural

environment for the growth of further segregation.

Thus, if respondent School Board cannot disprove

[past] segregative intent, it can rebut the prima

facie case only by showing that its past segregative

acts did not create or contribute to the current

60Except for the addition of footnote 4, Respondents are aware

of no material differences between Petitioners’ Proposed Findings of

Fact and Conclusions of Law submitted to the district court on

September 29, 1987 and the Memorandum Opinion of the trial

court.

^Dowell, 677 F. Supp. at 1513, P et App. 18b, quoting Keyes,

413 U.S. at 211.

- 35 -

segregated condition of the [virtually all-black]

schools.

The district court found that although racially

differentiated residential patterns in Oklahoma City

originally reflected "past governmental barriers," some

blacks had moved into formerly all-white census tracts

after 1960, demonstrating the "removal of past

governmental barriers."62 The court then determined

that the continuing virtually all-black character of the

"northeast quadrant" of the city was attributable to the

exercise of "personal preference" by white families, who

declined to move into the area.63 It concluded on this

basis that the school board had in no way "caused or

contributed to the patterns of the residential segregation

which presently exist in areas of Oklahoma City," and

6ZDowell, 677 F. Supp. at 1506-11, Pet App. 5b-15b.

63Dowell, 677 F. Supp. at 1511-12, P et App. 15b-17b.

- 36 -

that the board’s prior segregative acts had become too

attenuated to hold the board responsible for the virtually

all-black enrollments at ten elementary schools under the

1984 plan.64

The district court’s critical subsidiary fact-finding

about the nature and cause of the current virtually all

black demography of the "northeast quadrant" was based

entirely upon the testimony of one witness called by the

school board, Dr. William Clark.65 However, the court’s

finding is inconsistent with the testimony of Dr. Clark,

who recognized that what he termed "white preference”

did not exist in a vacuum but could be overlaid upon a

pattern of residential demography rooted in

discrimination:

^Dowell, 677 F. Supp. at 1512-13, Pet App. 17b-18b.

65See 677 F. Supp. at 1511-12, Pet App. 15b-17b.

- 37 -

Q. So that we -- is it your opinion that one would

not expect, based on those surveys and your

knowledge and the opinions you have expressed,

that whites would move into the established black

residential areas in Oklahoma City after 1950 or

1960, whatever point we want to take and look at

the areas of concentrations?

A. Generally, that’s correct.

Q. And does it not therefore follow that, to the

extent that past discrimination was a factor in

establishing concentrated minority residential

areas, that those areas are unlikely to change

because of the antipathy of whites to moving in

unless and until their black residents move

somewhere else?

A. I think that you would have to agree with

that, given what I’ve testified. Yes.

Tr. [June 15, 1987] 106.

This evidence from Dr. Clark was uncontradicted,

and it amply portrays the continuing contribution of the

school board’s and other official bodies’ discriminatory

acts to the current residential and elementary school

demography of the northeast quadrant. The court below

- 38 -

was therefore correct in applying the teaching of Swann

to conclude that the 1984 plan "fail[ed] to counteract the

continuing effects of past school segregation resulting

from discriminatory location of school sites or distortion

of school size in order to achieve or maintain an artifical

racial separation."66 Whatever the case may be with

respect to other jurisdictions where no findings of

residential impact were ever made,67 on this record the

continuing responsibility of the school board for the one-

race enrollments of "northeast quadrant" elementary

schools is beyond dispute, and the judgment below is

correct.

66Dowell, 890 F.2d at 1503, Pet. App. 40a, quoting Swann, 402

U.S. at 28.

67See, e.g., supra note 39.

- 39 -

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, Respondents

respectfully pray that the writ be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

LEWIS BARBER, JR.

Barber/Traviolia

1523 N.E. 23rd Street

Oklahoma City, OK 73111

(405) 424-5201

JANELL M. BYRD

1275 K Street, N.W.,

Suite 301

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

* Counsel of Record

JOHN W. WALKER

John W. Walker, P.A.

1723 So. Broadway

Little Rock, AR 72201

(501) 374-3758

JULIUS L CHAMBERS

* NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

99 Hudson Street,

16th floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

Attorneys for Respondents

- 40 -

APPENDIX

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF OKLAHOMA

No. CIV-9452

ROBERT U DOWELL, ETC, et a l,

Plaintiffs,

vs.

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE

OKLAHOMA CITY PUBLIC SCHOOLS, ETC., et al,

Defendants.

[Filed Jan. 18, 1977]

ORDER TERMINATING CASE

There is now pending before the Court a Motion

by the defendant to close the case. A hearing has been

conducted by the Court to receive the evidence of both

plaintiff and defendant concerning the state of

desegregation in the Oklahoma City Public Schools.

- la -

The Court has carefully reviewed this evidence and

all of the reports it has received from the defendant and

the Biracial Committee since the inception February 1,

1972 of "A New Plan of Unification for the Oklahoma

City Public School System," commonly known as the

Finger Plan. The Court has concluded that this was

indeed a Plan that worked and that substantial

compliance with the constitutional requirements has been

achieved. The School Board, under the oversight of the

Court, has operated the Plan properly, and the Court

does not foresee that the termination of its jurisdiction

will result in the dismantlement of the Plan or any

affirmative action by the defendant to undermine the

unitary system so slowly and painfully accomplished over

the 16 years during which the cause has been pending

before the Court.

- 2a -

Constitutional principles so bitterly contested by

former members of the Board have now become a part

of the fabric of the present school administration. The

only standard ever imposed by the Court has been

obedience to the Constitution, The School Board, as now

constituted, has manifested the desire and intent to follow

the law. The Court believes that the present members

and their successors on the Board will now and in the

future continue to follow the constitutional desegregation

requirements.

Now sensitized to the constitutional implications of

its conduct and with a new awareness of its responsibility

to citizens of all races, the Board is entitled to pursue in

good faith its legitimate policies without the continuing

constitutional supervision of this Court. The Court

believes and trusts that never again will the Board

become the instrument and defender of racial discrimina

- 3a -

tion so corrosive of the human spirit and so plainly

forbidden by the Constitution.

ACCORDINGLY, IT IS ORDERED:

1. The Biracial Committee established by the

Court’s Order of December 3, 1971, which has been an

effective and valued agency of the Court in the

implementation of the Plan, is hereby dissolved;

2. Jurisdiction in this case is terminated ipso facto

subject only to final disposition of any case now pending

on appeal.

Dated this 18th day of January, 1977.

/s/ Luther Bohanon

United States District Judge

- 4a -