NAACP v. Hampton County Election Commission Jurisdictional Statement

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1984

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. NAACP v. Hampton County Election Commission Jurisdictional Statement, 1984. 74fd5134-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/16cd8ddd-aded-4c22-a5e6-ab223bfa9f1a/naacp-v-hampton-county-election-commission-jurisdictional-statement. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

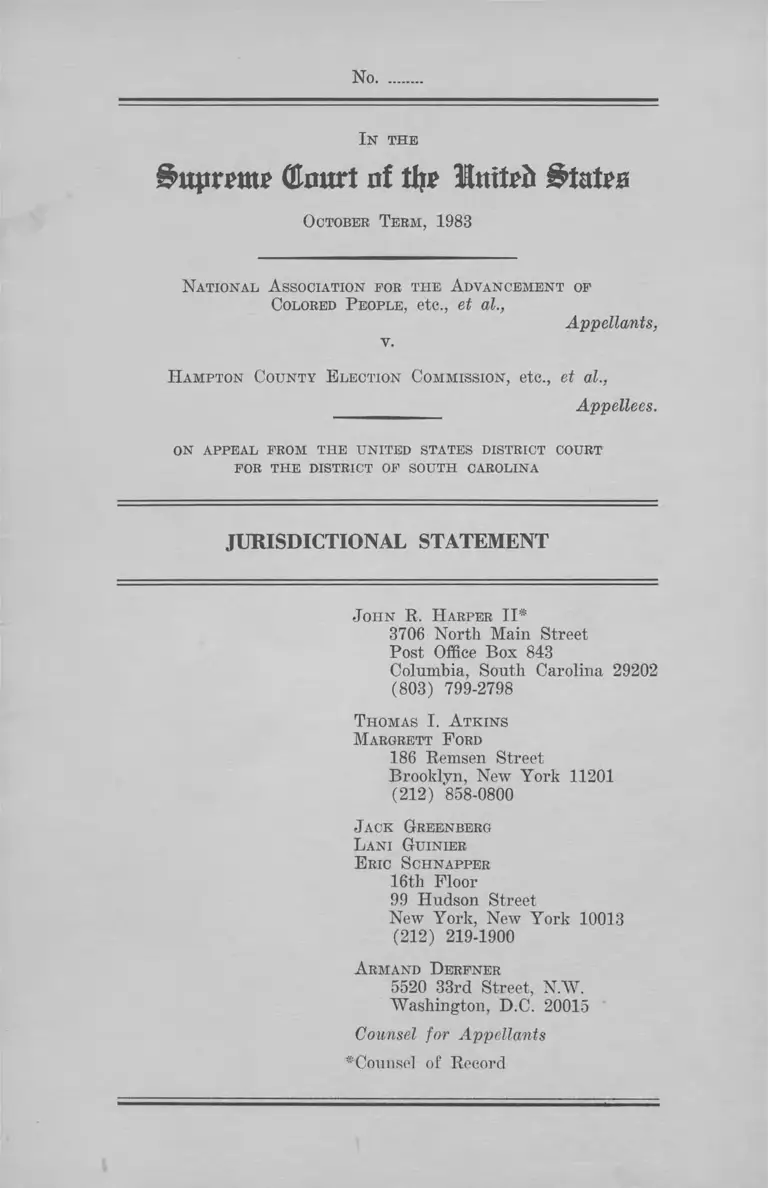

No.

I n the

i>upmttp (Emtrt of tft* l&ate

O ctober T erm , 1983

National A ssociation for th e A dvancement of

Colored P eople, etc., et al.,

Appellants,

v.

H am pton County E lection Comm ission , etc., et al.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM T1IE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

J o hn R. H arper II*

3706 North Main Street

Post Office Box 843

Columbia, South Carolina 29202

(803) 799-2798

T hom as I. A tk in s

M argrett F ord

186 Remsen Street

Brooklyn, New York 11201

(212) 858-0800

J ack Greenberg

L an i G uinier

E ric S chnapper

16th Floor

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

A rm and D erfner

5520 33rd Street, N .W .

Washington, D.C. 20015

Counsel for Appellants

* Counsel of Record

W .m o (ran.

Lani Guinier

June 27, 1984

Julius Chambers

Eric says that we have

a few more weeks to

deliberate on these

issues.

LG/r

Attach

1

Questions Presented

(1) Did the District Court err in holding that, in pre

clearing an election law under section 5 of the Voting

Rights Act, the Attorney General must be deemed to pre

clear as well all future changes in election practices and

procedures which may occur in the implementation of that

law?

(2) Did the District Court err in holding that changes

in election practices and procedures need not he precleared

under section 5 of the Voting Rights Act if those changes

occur in the implementation of a separate election law which

itself had earlier received such preclearance?

(3) Did the District Court err in holding that the im

plementation of a non-precleared change in election pro

cedures cannot be enjoined under section 5 of the Voting

Rights Act unless that change is in fact “ alleged to have

had either racially discriminatory purpose or effect” ?

(4) Did the District Court err in holding that state ac

tion knowingly and illegally implementing a change in

election law to which the Attorney General had objected

under section 5 is never to be invalidated by the federal

courts so long as that change subsequently receives pre

clearance ?

a

Parties

The appellants in this action are the National Associa

tion for the Advancement of Colored People, Inc., the

Hampton County, South Carolina Branch of the National

Association for the Advancement of Colored People, Inc.,

Benjamin Brooks, Jack J. DeLoach, Jessie M. Taylor,

Rev. Ernest McKay, Sr., Soletta Taylor, Jesse Lee Carr,

W.M. Hazel, John Henry Martin, Washington G. Garvin,

Jr., Dora E. Williams, James Fennell, Vernon McQuire,

Bossie Green and Earl Capers.

The appellees in this action are:

(1) The Hampton County Election Commission and its

members, Randolph Murdaugh, III, Richard Sinclair,

James Wooten, and W.H. Smith,

(2) The Hampton County School District No. 1 and its

trustees, Philip Stanley, Lenon Brooker, Rebecca

Badger, Wiley Kessler and Gerald Ulmer,

(3) The Hampton County School District No. 2 and its

trustees, T.M. Dixon, Willie J. Orr, Virgin John

son, Jr., Rufus Gordon, and Lee Manigo,

(4) Willingham Cohen, Sr., Marcia Woods, Louise Hop

kins, Charlie Crews and William Bowers, the mem

bers of the Hampton County Council, and

(5) Wilson P. Tuten, Jr., the Hampton County Trea

surer.

Ill

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Questions Presented ......................................................... i

Parties ................................................................................ ii

Table of Authorities......................................................... iv1

Opinion Below .................................................................. 1

Jurisdiction ........................................................................ 2

Statutes Involved............................................................... 2

Statement of the Case ..................................................... 2

The Questions Are Substantial ...................................... 7

Conclusion .......................................................................... 18

A pp e n d ix—

Order of the District Court, September 9, 1983 .... la

Notice of Appeal ....................................................... 12a

Votings Rights Act of 1965, Section 5 .................. 14a

Act No. 547, South Carolina Laws (1982) . 17a

Act No. 549, South Carolina Laws (1982) . 19a

1Y

T able of A uthorities

Cases: page

Allen v. State Board of Elections, 393 U.S. 544 (1969)

8, 9,11,12,13,14,15-16,17

Berry v. Doles, 438 U.S. 190 (1978) ........................ 8,14,15

Blanding v. Dubose, 454 U .S .------ (1982) .................... 17

Canady v. Lumberton Board of Education, —*— U.S.

------ (1982) .................................................................... 17

City of Rome v. United States, 446 U.S. 156 (1980) ....9,12

Connor v. Waller, 421 U.S. 656 (1975) ........................... 10

Dougherty County v. White, 439 U.S. 32 (1978) ....9,10,16

Georgia v. United States, 411 U.S. 526 (1973) ........... 13

Hadnott v. Amos, 394 U.S. 358 (1969) ........................ 9

Hicks v. Miranda, 422 U.S. 332 (1975) ........................ 17

McCain v. Lybrand, No. 82-282 ........................................ 17

Perkins v. Matthews, 400 U.S. 379 (1971) ...........11,14,16

United States v. Board of Supervisors, 429 U.S. 642

(1977) .............................................................................. 16

United States v. Sheffield Board of Commissioners, 435

U.S. 110 (1978) .............................................................12,13

Whitely v. Williams, 393 U.S. 544 (1969) .................... 9

Statutes and Constitutional Provisions:

28 U.S.C. § 1253 ................................................................ 2

28 U.S.C. § 2101(b) .......................................................... 2

42 U.S.C. § 1973c ..........................................................passim

Y

PAGE

Voting Rights Act of 1965, § 2 ....................................... 6n

Voting Rights Act of 1965, § 5 ................................... passim

Act 547, South Carolina Laws (1982) ........................2, 3, 5

Act 549, South Carolina Laws (1982) ...................... passim

Regulations:

28 C.F.R. § 51.12(g) ......................................................... 9

28 C.F.R. § 51.20 ............................................................... 4

Rules:

Rule 6(a), Federal Rules of Civil Procedure............... 2n

Supreme Court Rule 12.1 ............................................... 2

Supreme Court Rule 29.1 ............................................... 2n

Reports:

S.Rep. No. 97-417 ............................................................. 15

H.R. Rep. No. 97-227 ....................................................... 15

TJ.S. Constitution:

Fourteenth Amendment ................................................ 6n

Fifteenth Amendment ..................................................... 6n

No.

I n the

(to ri of thr llnttrfc Stairs

October T erm, 1983

National A ssociation for the A dvancement of

Colored P eople, etc., et al.,

v .

Appellants,

H ampton County E lection Commission, etc., et al.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

Appellants National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People, etc., et al., appeal from the order of Sep

tember 9, 1983, of the three-judge United States District

Court for the District of South Carolina denying injunc

tive relief and dismissing the complaint in this action in

sofar as it sought relief under section 5 of the Voting

Rights Act of 1965.

Opinion Below

The opinion of the district court of September 9, 1983,

which is not reported, is set out at pp. la -lla of the ap

pendix hereto.

2

Jurisdiction

The order of the three-judge district court, denying in

junctive relief and dismissing the complaint insofar as it

sought relief under section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, was

entered on September 9, 1983. (App. la ). A timely notice

of appeal was filed on October 10, 1983.1 (App. 12a). See

28 U.S.C. § 2101(b). On December 7, 1983, the Chief Jus

tice extended the date for docketing this appeal until

December 16, 1983. The jurisdiction of this Court is in

voked under 28 U.S.C. § 1253.

Statutes Involved

Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, as amended,

42 U.S.C. § 1973c, is set out at pp. 14a-16a of the appendix

hereto. Acts 547 and 549 of the South Carolina Laws of

1982 are set out at pp. 17a-18a and pp. 19a-21a of the

appendix.

Statement of the Case

From prior to 1964 until 1982 the Hampton County pub

lic school system was controlled by the Hampton County

Board of Education. During this period the six members

of the County Board were appointed by the Hampton

County members of the South Carolina legislature. The

school system was in turn divided into two school dis

tricts with separate Boards of Trustees, whose members

were appointed by the County Board. Over 91% of all

white public school students in the county attend the schools

1 The thirtieth day after September 9, 1983, was a Sunday, Octo

ber 9, 1983. Accordingly, the notice of appeal was due on October

10, 1983, the date on which it was filed. Rule 6(a) , Federal Rules

of Civil Procedure; Supreme Court Rule 29.1.

3

in District No. 1, while the student population of the Dis

trict No. 2 schools is 92% black. Each school district has

operated autonomously under the general supervision of

the County Board and of an elected County Superintendent

of Education.

On February 18, 1982, the South Carolina legislature

enacted Act 547, which provided that, beginning January

1, 1983, the six members of the County Board were to be

elected rather than appointed. The Superintendent of

Education, while continuing.to be elected at-large, was to

serve as a seventh voting member of the newly consti

tuted County Board. The first elections for the new County

Board were to be conducted in November, 1982. The pur

pose for electing the County Board members, rather than

appointing them, was apparently to create a County Board

responsive to consolidating School Districts Nos. 1 and 2.

Act 547 was promptly submitted to the United States At

torney General for preclearance under section 5 o f the

Voting Bights Act, and received that preclearance on

April 28, 1982.

The adoption of Act 547, however, provoked substan

tial opposition among the white residents of District No. 1.

According to the complaint, those whites circulated a peti

tion calling for the abolition of both the County Board and

the position of County Superintendent of Education, thus

severing the connection between Districts One and Two.

As a result of that petition, and with the backing of the

Hampton County Council, a white member of the county

legislative delegation introduced legislation to overturn

Act 547. This new measure was enacted on April 9, 1982

as Act 549. Act 549 abolished the Hampton County Board

of Education and the position of Hampton County Super

intendent of Education. It provided that their duties were

to be assumed by the Trustees of School Districts 1 and 2.

Beginning in November, 1982, the Trustees of those school

4

districts were to be elected at-large at the general elec

tion. Act 549 provided that candidates for election to these

newly reconstituted school boards were to file with the

county Election Commission between August 16 and 31,

1982. Implementation of Act 549, however, required ap

proval of a referendum of Hampton County voters to be

conducted in May, 1982.

When Act 549 was adopted there was ample time, a

total of 129 days, to obtain preclearance before the sched

uled filing period was to begin on August 16. But although

Department of Justice regulations expressly authorized

consideration of a preclearance request prior to the hold

ing of any necessary referendum, 28 C.F.R. § 51.20, no

effort was made to submit Act 549 during either April or

May of 1982. Wrhen the necessary referendum approved

Act 549 on May 25, 1982, there remained sufficient time,

83 days, in which to obtain preclearance prior to the com

mencement of the filing period. But state and local officials

delayed still further. Not until June 24, 1982, some 30

days later, was the necessary submission received by the

United States Attorney General; by then the time remain

ing until the statutory filing period was to begin was less

than the 60 days normally required for preclearance under

section 5.

As a result of these delays, the Attorney General had

taken no action on Act 549 when the filing period for

elections under that Act commenced on August 16, 1982.

Despite the fact that section 5 of the Voting Rights Act

forbids any implementation of a new election practice or

procedure which lacks preclearanoe, Hampton County elec

tion officials, who were well aware of the requirements

of federal law, began to accept petitions for candidates

seeking election in the new districts created by Act 549.

On August 23, 1982, the Attorney General objected to Act

549 insofar as it abolished the County Board. Despite this

5

objection, Hampton County officials continued to imple

ment the Act 549 filing period. On September 1, 1982,

after that filing period had ended, county officials sub

mitted to the Attorney General a request for reconsidera

tion of his objection. They also began for the first time to

accept filings for election under Act 547, the only law

which then had the necessary preclearance. On November

2, 1982, having received no response to their request for

reconsideration, county election officials held elections for

the County Board under Act 547. Of the six board mem

bers elected on that date, three were black and three were

white.

On November 19, 1982, the Attorney General withdrew

his objection to Act 549. On November 29, 1982, the chair

man of the Hampton County Election Commission wrote

the South Carolina Attorney General and requested his

opinion on three questions:

(1) Should an election be held to elect Trustees for

Hampton County School Districts 1 and 2?

(2) I f so, when should such an election be held?

(3) Should the filing period for the respective District

Boards of Trustees be “ reopened” ?

The state Attorney General responded on January 4, 1983,

advising the County that it should hold new elections “ [a]s

soon as possible” and that it need not “ reopen” the filing

period. Acting on this advice, the Hampton County Elec

tion Commission conducted elections in Districts 1 and 2

on March 15, 1983. The six individuals elected in Novem

ber, 1982, to the County Board of Education were never

permitted to take office.

The advice given by the state Attorney General and

acted upon by the county had two distinct effects of im

6

portance to this litigation. First, although the express lan

guage of Act 549 authorized election of District Trustees

only during a general election, the Trustees were in fact

chosen at a special off-year election. Second, despite the

fact that Act 549 contemplated that the filing period would

begin several months after the Act went into effect, the

filing period for the 1983 election in fact closed more than

two months before the statute became effective. The only

time at which candidates for District Trustee were per

mitted to file for that office was when the conduct of such

filings was illegal under section 5 of the Voting Rights

Act.

The appellants, two civil rights organizations and sev

eral residents of Hampton County, commenced this action

in the United States District Court for the District of

South Carolina seeking an injunction to forbid the pro

posed elections as illegal under section 5 of the Voting

Rights Act,2 and to place in office the duly elected mem

bers of the County Board of Education. Appellants al

leged that the proposed elections violated section 5 be

cause they were to occur at a time other than that pro

vided for in Act 549, and because the elections were limited

to candidates who had filed for election during the illegal

August 1982 filing period.3 A three judge court was con

_2 The complaint also alleged that the Election Commission, in

violation of section 3 of Act No. 549, had failed to certify to the

South Carolina Code Commissioner the results of the May 1982

referendum. Although we disagree with the district court’s rea

sons for rejecting this claim, our review of the record indicates

that that certification was in fact made. Accordingly, we do not

seek review of the district court’s denial of injunctive relief re

garding the alleged lack of certification.

3 The complaint also alleged that the abolition of the elected

County Board of Education violated section 2 of the Voting Rights

Act and the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. These claims

were not dismissed, and are the subject of continuing litigation

in the district court.

7

vened to hear the case, as required by 42 TJ.S.O. § 1973c.

Appellants unsuccessfully sought to enjoin the March 15,

1983, special election. Subsequently, on September 9, 1983,

the district court denied appellants’ request for injunctive

relief and dismissed their complaint insofar as it sought

to state a claim under section 5 of the Voting Eights Act.

The Questions Presented Are Substantial

This case presents yet another attempt on the part of

a jurisdiction subject to section 5 of the Voting Rights

Act to avoid compliance with the provision’s requirement

that no alteration in any election practice or procedure

be implemented until and unless precleared by the Attorney

General of the United States or the United States District

Court for the District of Columbia. The voting changes

involved in this appeal took place in connection with an

election for school trustees, which was held under new

procedures which either lacked preclearance under the

Voting Rights Act or had in fact been objected to by the

Attorney General. The district court, in denying any in

junctive relief, created no less than four new exceptions

to the requirements of section 5. The decision below, if

upheld by this Court, would substantially impair the scope

and effectiveness of section 5, and seriously interfere with

the ability of the Attorney General to carry out his ad

ministrative responsibilities under the Voting Rights Act.

This case arose, quite simply, because the appellees

ignored section 5 not once but several times in the course

of changing the system of selecting school boards in Hamp

ton County. First, the implementation of the new statute,

Act 549, was begun without the required preclearance, and

continued even after an objection had been entered by the

Attorney General. Following an interlude o f compliance

during which implementation stopped and a scheduled elec

8

tion was canceled, the violations began anew after the

Attorney General withdrew his section 5 objection to Act

549. At that point the appellees proceeded to set a new

election and to adopt election procedures different from

those in the text of Act 549, without any effort to preclear

these new changes. Finally, in conducting the new election

the appellees barred from the ballot all candidates except

•those who had filed under Act 549 at a time when the

conduct of a filing period under Act 549 was clearly illegal

under the Voting Rights Act. One of the would be candi

dates rejected because of a failure to participate in this

illegal filing period was the chairman of the about to be

abolished County Board of Education, who wished to run

for a seat on one of the trustee boards which was to re

place his office.

The first election law change which has never received

preclearance under section 5 is an alteration of the date

for conducting the initial election of the trustees of the

local school boards. Section 1(b) of Act 549, as earlier

approved by the Attorney General, authorized the elec

tion of district trustees only at the “ general election” held

in November of even-numbered years in South Carolina.

A state statute altering the election date from the general

election to March of an off-year would clearly have been

a change in a “ standard, practice or procedure with respect

to voting .... ” 42 U.S.C. § 1973c. This Court has repeatedly

held that Congress intended section 5 “ to reach any state

enactment which altered the election law of a covered State

in even a minor way.” Allen v. State Board of Elections,

393 UjS. 544, 566 (1969). In Berry v. Doles, 438 U.S .190

(1978), this Court held that section 5 applied to a state

statute changing the time at which certain Georgia county

officials were to be elected. Such a change in the timing

of an election has an obvious potential adverse impact on

the number of minority voters participating when, as here,

9

the election is moved from a regular general election to a

special election, since voter turnout at special elections

is predictably lower. In the instant case, for example,

over 6000 Hampton County voters participated in the

November 1982 general election/ while less than half that

number voted in the March 1983 special election.

Second, the procedures adopted by appellees effectively

constituted a change in the candidate filing rules. Act 549,

as approved by the Attorney General, authorized only two

filing periods, the August 16-31 period for a contemplated

November, 1982, school board election, and the usual filing

period for subsequent school board elections. The Act

neither established any filing period for a March 1983

special election, nor sanctioned the use of the August

1982 filings for any election other than that to occur in

November, 1982. This Court has repeatedly held that such

candidate qualification rules are subject to section 5. City

of Rome v. United States, 446 U.S. 156, 160-61 (1980)

(residence requirement); Dougherty County v. White, 43-9

U.S. 32 (1978) (mandatory leave for candidate in govern

ment job ); Hadnott v. Amos, 394 U.S. 358 (1969) (filing

requirements for independent candidates); Whitely v.

Williams, 393 U.S. 544, 570 (1969) (filing requirements

for independent candidates). The Justice Department sec

tion 5 regulations expressly require submission of “ [a]ny

change affecting the eligibility of persons to become can

didates.” 28 C.F.R. § 51.12(g). Submission of changes in

such laws is required because candidate qualification rules

may “undermine the effectiveness of voters who wish to

elect . . . candidates” excluded by those rules. Allen v.

Board of Elections, 393 U.S. at 570.

The filing rule at issue in this case to an extraordinary

degree “burdens entry into elective campaigns and, con- 4

4 Complaint, Exhibit 15-1.

10

comitantly, limits the choices available to voters.” Dou

gherty County v. White, 439 TJ.S. at 40. The standard

adopted in January 1983 for the March 1983 special elec

tion required prospective candidates to have filed no later

than August 31, 1982. By the time that that requirement

was announced, the deadline it imposed was more than

four months past. This unusual ex post facto requirement

had an obvious discriminatory impact. First, the March

special election was open only to candidates who had been

willing to participate in the palpably illegal August 1982

filing, which had been conducted at a time when imple

mentation of the statute involved violated section 5. Pro

spective candidates could only obtain a place on the March

1983 ballot by “ obeying” in August 1982 election rules

to which an objection had been interposed by the Attorney

General and which under the Voting Rights Act were

not and could not then have been “ effective as laws.”

Connor v. Waller, 421 U.S. 656 (1975). Second, since

only one black candidate5 had filed for election as a trustee

of District No. 1 during the illegal August 1982 filing

period, the rule guaranteed white domination of that Dis

trict regardless of the wishes of minority voters, and de

prived those voters of any opportunity to vote for more

than a single black candidate. Thus, had the decision to

require an August, 1982 filing been contained in a state

statute and submitted to the Attorney General, there was

good reason to believe that he would have objected to it.

The district court nonetheless held that these new elec

tion procedures did n’ot require preclearance under sec

tion 5, offering in support of its conclusion several different

theories, each of which is, in our view, incompatible with

the Voting Rights Act.

5 Lenon Brooker. He was among the five candidates elected in

March, 1983.

11

The district court reasoned, first, that once an election

law is precleared, section 5 is simiply inapplicable to any

alterations in election procedures which occur in the im

plementation of that precleared law. Thus the new pro

cedures involved in this case, it asserted, did not

constitute “changes” within the meaning of Section 5.

Each of these acts were not alterations of South

Carolina law, hut rather steps in the implementation

of & new statute. . . . [T]he preclearance requirement

of Section 5 applied to the new statute, Act No. 549,

while the ministerial acts necessary to accomplish the

statute’s purpose were not “ changes” contemplated by

iSeetion 5, and thus did not require preclearance. (App.

8a-9a).

On the district court’s view, once Act 549 was precleared,

Hampton County election officials were free to select any

date for the trustee elections and to adopt any filing re

quirement, regardless of whether, as in fact occurred, the

date and filing requirement were different than those in

the Act submitted to and approved by the Attorney General

of the United States.

Were that the rule, preclearance of any election law

under section 5 would free state and local election officials

to alter at will any other election practice or procedure

that might be involved in the implementation of the pre

cleared law. Such an exemption from the coverage of

section 5, carrying with it an open invitation to evasion

'of the requirements of the Voting Rights Act, is clearly

inconsistent with the intent of Congress “ to give the Act

the broadest possible scope.” Allen v. Board of Elections,

393 U.S. at 567. This Court has consistently refused to

create an exception to section 5 for purportedly “minor”

changes made by local election officials, see e.g. Perldns v.

Matthews, 400 U.S. 379 (1971), and the Attorney General

12

has properly insisted that even those technical changes

in election procedures needed to implement longstanding

election laws must be submitted for preclearance. City of

Rome v. United States, 446 U.S. 156, 183 (1980).

The district court apparently applied this novel excep

tion to section 5 in rejecting appellants’ claim that the

appellees had prematurely abolished the position of Super

intendent of Education. Act 549 did abolish that position

as of June 30, 1985, but plaintiffs complained that by mid-

1983 the Superintendent had been stripped of his prior

responsibility and authority.6 The district court reasoned

that since Act 549 had been precleared under section 5,

“ Section 5 does not reach this aspect of plaintiffs’ corn-

plant” , despite the fact that abolition of that position was

being implemented two years earlier than the particular

date actually authorized by Act 549 and approved by the

Attorney General.

The district court suggested, in the alternative, that

the new election procedures at issue in this case had some

how “been precleared along with the . . . provisions of

Act No. 549.” (App. 9a). In particular the court asserted,

apparently with regard to the illegal August 1982 filing

period, that “ the eventual preclearance of Act 549 ratified

and validated for Section 5 purposes those acts of imple

mentation which had already been accomplished.” (App.

10a). But this Court has repeatedly rejected suggestions

that the Attorney General be deemed to have approved

changes in election procedures where those changes were

not formally submitted to him in full compliance with the

applicable section 5 regulations. City of Rome v. United

States, 446 U.S. at 169 n. 6; United States v. Sheffield

Board of Commissioners, 435 U.S. 110, 136 (1978); Allen

6 Affidavit of John W . Dodge, Hampton County Superintendent

of Education, dated July 13, 1983.

13

v. Board of Elections, 393 UjS. at 571. It is not sufficient

that the Attorney General may have known of a proposed

change; the responsible authorities must “ in some unam

biguous and recordable manner submit any legislation or

regulation in question to the Attorney General with a re

quest for his consideration pursuant to the Act.” Allen

v. Board of Elections, 393 U.S. at 571. “ [T]he purposes

Of the Act would plainly be subverted if the Attorney

General could ever he deemed to have approved a voting

change when the proposal was neither properly submitted

nor in fact evaluated by him.” United States v. Sheffield

Board of Commissioners, 435 U.S. at 136.

In the instant case the Attorney General could not pos

sibly have evaluated or intended to approve the changes

at issue when he withdrew his objection to Act 549, since

that objection was withdrawn in November, 1982, and the

decisions at issue—to hold a special election and to require

candidates to have registered in August, 1982—were made

in January 1983, two months after the Attorney General’s

action. I f a decision by the Attorney General to preclear

a new statute has the sweeping effect attributed to it by

the district court, approving as well both premature imple

menting steps of which the Attorney General may be un

aware, and subsequent implementation actions which he

could not foresee, it would be impossible for the Attorney

General to carry out his responsibilities under section 5

in an informed and conscientious manner. Under the best

of circumstances “ [t]he judgment that the Attorney Gen

eral must make is a difficult and complex one, and no one

would argue that it should be made without adequate in

formation.” Georgia v. United States, 411 UjS. 526, 540

(1973). But if the Attorney General cannot know in ad

vance what implementing steps he is implicitly approving,

it would be manifestly impossible to make the critical

judgment which Congress contemplated.

14

In addition, the district court concluded that the Novem

ber, 1982, preclearance of Act 549 ipso facto removed all

taint of illegality from the August 1982 filing period. Bely

ing on this Court’s decision in Berry v. Doles, 438 TJ.S. 190

(1978), the court below held that “ a retroactive validation

of an election law change under Section 5 could he achieved

by after-the-fact federal approval.” (App. 10a). In Berry,

as in Perkins v. Matthews, 400 U.S. 379 (1971), the issue

before this Court was whether an election held without

the necessary section 5 preclearance must be voided and

conducted anew even though the changes at issue subse

quently received the required preclearance. Neither case

established a per se rule that such relief was never ap

propriate. Perkins held only that “ [i]n certain circum

stances” invalidation of an action taken in violation of

section 5 might not be required, 400 U.S. at 396, and Berry

merely found such circumstances to be present on the par

ticular facts of that case. 438 U.S. at 192. Both cases

recognized the desire o f Congress to prevent the imple

mentation of all election changes which had not received

section 5 preclearance, not just those to which such pre-

clearance would ultimately be denied.

Fourteen years ago, noting that the scope of section 5

raised “complex issues of first impression” , this Court in

dicated a temporary reluctance to overturn elections con

ducted without preclearance. Allen v. Board of Elections,

393 U.S. at 572. In extending section 5 in 1982, however,

Congress made clear its desire that the Voting Bights Act

be strictly complied with. Congress amended the bailout

provisions of the Act to ensure that exemption from

coverage by section 5 not be accorded to jurisdictions

which had violated that provision. The Senate Beport

emphasized:

“ [I] t is the Committee’s intent that compliance with

Section 5 means that even if an objection is ultimately

15

■withdrawn or the judgment of the District Court for

the District of Columbia denying a declaratory judg

ment is vacated on appeal, the jurisdiction is still in

violation if it had tried to implement the change while

the objection or declaratory judgment denial was in

effect.” S.Rep. No. 97-417, p. 48.

Virtually identical language appears in the House Report,

H.R. Rep. No. 97-227, p. 42. Both the House and Senate

Reports include extensive references to the failure of

covered jurisdictions to make the timely submissions re

quired by section 5.

As Justice Brennan noted in his concurring opinion in

Berry, in the absence of any credible threat that actions

violative of section 5 will be invalidated by the federal

courts, “ the political units covered by § 5 may have a posi

tive incentive flagrantly to disregard their clear obliga

tions and not to seek preclearance of proposed voting

changes.” 438 H.S. at 194. That is precisely what oc

curred in the instant case. The defendant election officials

knowingly implemented Act 549 when it lacked section 5

preclearance, in the hope that such preclearance would

eventually be obtained, and in the apparent belief that

subsequent preclearance would immunize from redress that

unlawful implementation. The district court’s decision en

courages precisely the sort of section 5 violation which

concededly occurred in August 1982, and flies in the face

of the clear intent o f Congress.

Finally, the district court held that an allegation of

“ either racially discriminatory purp'ose or effect” was “ es

sential to a Section 5 action.” (App. 8a). This is a thinly

disguised version of a construction of section 5 that has

been repeatedly and unanimously rejected by this Court.

In Allen v. Board of Elections this Court held:

16

A declaratory judgment brought by the State pur

suant to § 5 requires an adjudication that a new

enactment does not have the purpose or effect of racial

discrimination. However, a declaratory judgment ac

tion brought by a private litigant does not require the

Court to reach this difficult substantive issue. The

‘only issue is whether a particular state enactment is

subject to the provisions of the Voting Rights Act,

and therefore must he submitted for approval before

enforcement. 393 U.S. 558-59. (Emphasis in original).

In Perkins v. Matthews, 400 U.S. 410 (1971), the district

court dismissed a section 5 action because it believed that

the election law changes at issue lacked any discrimina

tory purpose or effect. This Court reversed:

The three-judge court misconceived the permissible

scope of its inquiry into [plaintiffs] allegations. . . .

What is foreclosed to such district court is what Con

gress expressly reserved for consideration by the Dis

trict Court for the District of Columbia or the At

torney General—the determination whether a covered

change does or does not have the purpose or effect

“ of denying or abridging the right to vote on account

of race or color.” 400 U.S. at 383-85.

That rule has since been reaffirmed in Dougherty County

v. White, 439 U.S. 32, 42 (1978) and United States v.

Board of Supervisors, 429 U.S. 642, 645-46 (1977). Neither

the evidence adduced in a private action to enforce sec

tion 5, nor the allegations of the complaint in such an

action, are to be tested by standards which Congress has

expressly reserved to a preclearance proceeding in the

District Court for the District of Columbia or before the

Attorney General.

17

The decision of the district court in this case is thus

wholly at odds with both the intent of Congress in enact

ing the Voting Rights Act and the established construc

tion of section 5. That decision is likely to encourage the

problems of noncompliance with section 5 which have con

tinued to engage this Court, See, e.g., Blandmg v. Dubose,

454 U .S .------ (1982); Ccmady v. Lumberton Board of Ed

ucation, ------ U.S. ------ (1982) ; McCain v. Lybrand, No.

82-282. Summary affirmance by this Court would require

federal courts throughout the country to adhere to the ill-

considered standards applied below, until and unless this

Court directed otherwise. Hicks v. Miranda, 422 U.S. 332,

344-45 (1975). Summary affirmance would as a practical

matter overrule, at least in part, virtually every section 5

decision handed down by this Court since Allen v. Board

of Elections, and would wreak havoc in the implementa

tion and administration of section 5. The questions pre

sented by this appeal are as substantial as the decision

of the district court is unsound.

18

CONCLUSION

For the above reasons, this Court should note prob

able jurisdiction of this appeal.

Respectfully submitted,

John R. H arper II*

3706 North Main Street

Post Office Box 843

Columbia, South Carolina 29202

(802) 799-2798

T homas I. A tkins

M argrett F ord

186 Remsen Street

Brooklyn, New York 11201

(212) 858-0800

Jack Greenberg

L ani Guinier

E ric S chnapper

16th Floor

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

A rmand Derener

5520 33rd Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20015

Counsel for Appellants

^Counsel of Record

APPENDIX

la

I n the

DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

F or the D istrict of South Carolina

A iken D ivision

Civil Action 83-612-6

Order of District Court, September 9, 1983

National A ssociation for the A dvancement of

C olored P eople, I nc., etc., et al.,

Plamtiffs,

—versus—

H ampton County E lection Commission,

a public body politic; et al.,

Defendants.

On July 21, 1983, this case came before a three-judge

district court for arguments on whether certain actions

alleged by the plaintiffs constituted changes in election

practice or procedure which had not received preclearance

by the United States Attorney General, pursuant to Sec

tion 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.O.A.

§ 1973(c). It was conceded that if there had been no

“change” within the meaning of Section 5, or if such change

had been properly precleared, the portion of this action

brought under Section 5 should be dismissed, and the three-

judge court dissolved. After consideration of the argu

ments and memoranda of counsel, this court unanimously

concluded that there had been no Section 5 changes ac

complished without preclearance in this matter. For that

2a

reason, the three-judge court dismissed the Section 5 por

tion of this case in an oral Order. The instant Order in

corporates and memoralizes that earlier ruling from the

bench.

The factual background of this action focuses upon the

history of governance of the public school system of Hamp

ton County, South Carolina. Since the provisions of Sec

tion 5 apply to departures from the voting standards, prac

tices, or procedures that existed on November 1, 1964, that

date becomes significant as the baseline against which

Section 5 “ changes” are measured.1 Since well before that

point, the Hampton County Public School System was

controlled by the Hampton County Board of Education

(the “ County Board” ), the Hampton County Superin

tendent of Education (the “ Superintendent” ), and the

Boards of Trustees for School Districts One and Two

(the “ Trustees” ). The six member County Board was

appointed by the Hampton County Legislative Delegation.

In turn, the County Board appointed Hampton County

residents to serve as Trustees of the individual Districts,

each trustee board having six members. A County Super

intendent elected at large by the qualified voters of Hamp

ton County served as an advisor to the teachers and

trustees of each district. Each school district operated

separately under the general supervision of district super

intendents.

On February 18, 1982 the South Carolina General As

sembly passed Act No. 547, Acts and Joint Resolutions,

1 Section 5 requires South Carolina and its political subdivi

sions to obtain federal approval from the United States Attorney

General or the United States District Court for the District of

Columbia before enforcing any “practice or procedure with respect

to voting different from that in force or effect on November 1,

1964.”

Order of District Court, September 9, 1983

3a

1982 (R311), which changed the government body for the

Hampton County public school system. Beginning Jan

uary 1, 1983, the County Board was to be composed of six

at-large members, who were to be elected, rather than ap

pointed. The Superintendent, while continuing to be elected

at-large, was to serve as an ex officio County Board member,

having all rights and privileges of other members includ

ing the right to vote. The purpose for electing the County

Board members, as opposed to appointing them, was to

create a County Board that would be responsive to con

solidating School Districts One and Two. Act No. 547 was

submitted by the South Carolina Attorney General to the

United States Attorney General, who precleared it, pur

suant to Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, on April 28,

1982.

Act No. 547, however, was superseded by another piece

of legislation, Act No. 549, Acts and Joint Resolutions,

1982 (R398). On April 9, 1982, the Governor of South

Carolina signed Act No. 549, which abolished the Hampton

County Board of Education and the Hampton County

Superintendent of Education. Once these offices were

abolished, their respective duties were to be assumed by

the Trustees for School District One and Two.

Beginning with the November 1982 general election, the

District One and Two Trustees were to be elected at-large,

rather than appointed, by a plurality vote of the electors

within each respective district. The number of Trustees

serving on each board was reduced from 6 to 5. Act No.

549 stated that a candidate offering for election in Novem

ber 1982 must file with the Hampton County Election Com

mission during the period August 16-31, 1982. Act No.

549 contains no language giving local election officials the

authority to hold a filing period other than the one specified.

Order of District Court, September 9, 1983

4a

These changes in the school system’s governing body

were contingent upon approval by a majority of the quali

fied electors voting in a referendum in May 1982. Ac

cordingly, the Hampton County Election Commission con

ducted a referendum on May 25, 1982. A majority of the

voters approved Act No. 549. Therefore, by mandate of

the voters of Hampton County, the offices of the County

Board and Superintendent of Education were to cease to

exist on June 30, 1982 and June 30, 1985, respectively.

As required by Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, Act

No. 549 was submitted to the United States Attorney Gen

eral for preclearance on June 16, 1982. The next week,

June 23, the sitting County Board members adopted an

Order of Consolidation that consolidated Districts One and

Two into a unitary school district. The following week,

however, the same County Board voted to rescind its

earlier Order of Consolidation.

Act No. 547 had already been precleared by the United

States Attorney General. Thus, Act No. 549, in order to

supersede Act 547, had to receive preclearance itself.

The situation was further complicated by the fact that

the Attorney General is given 60 days to respond to a

request for preclearance. In addition, the Attorney Gen

eral may request additional information from the sub

mitting authority. Such a request tolls the original 60-

day period so that it does not start to run until the addi

tional information is received. Thus it is possible that the

submitting jurisdiction may have to wait for 120 days be

fore it receives a response on preclearance.

When this fact is taken into account, there existed the

chance that the filing period for candidates for District

One and Two Trustees, August 16-31, would expire be

fore the Attorney General precleared Act No. 549. If Act

Order of District Court, September 9, 1983

5a

No. 549 was precleared, pursuant to state law, it would

supersede Act No. 547. But if preclearance came after

August 31, Trustee elections could not be held as sched

uled, because no candidate would have qualified by filing

during the specified statutory filing period.

To avoid this potential dilemma, the Hampton County

Election Commissioner began accepting Trustee filings on

August 16, 1982. On August 23, 1982, a full 60 days after

Act No. 549 was submitted, the Attorney General objected

to a portion of Act No. 549. The Attorney General found

neither a discriminatory purpose nor effect in the change

of the method of selecting Trustees from appointment to

election, but he was unable to conclude that the proposal

to terminate the County Board was not discriminatory

toward black Hampton County residents. The Attorney

General noted, however, in his objection letter that the

“Procedures for the Administration of Section s (28 C.F.R.

51.44) permit you to request the Attorney General to rê

consider the objection.”

Because the Attorney General’ s objection was received

in the middle of the filing period, the Hampton County

Election Commission continued to accept filings until the

end of August while Hampton County officials determined

whether they would submit a request for reconsideration

of the objection.

Hampton County submitted a request for reconsidera

tion on September 1, 1982. Because there remained the

chance that the request for reconsideration would be de

nied, the Election Commission also began accepting filings

for the election of County Board members under Act No.

547. A candidate who had filed for the office of Trustee

was also permitted to file for the County Board. As of

November 1,1982, the Attorney General had not responded

Order of District Court} September 9, 1983

6a

to the request for reconsideration. Accordingly, the Hamp

ton County Election Commission held elections for County

Board members on November 2, 1982.

Shortly thereafter, the Attorney General withdrew his

objection to Act No. 549. In his letter of November 19,

1982, the Attorney General withdrew his objection to the

abolition of the County Board because “a reappraisal of

South Carolina law establish [ed] that the county board

lacks authority to effect a consolidation and its abolition

. . . will not have the potentially discriminatory impact we

had initially perceived.”

Once the Attorney General precleared Act No. 549, Act

No. 547 became void. Even though the election for County

Board members had been held in November 1982, Act No.

547 became a nullity when the Attorney General precleared

Act No. 549.

Threafter, the Hampton County Election Commission

prepared to hold elections for the Trustees of Districts

One and Two. On November 29,1982, Randolph Murdaugh,

III, Chairman of the Hampton County Election Commis

sion, wrote the South Carolina Attorney General and re

quested an Attorney General’ s opinion on the following

three questions :

(1) Should an election be held to elect Trustees for

Hampton County School Districts Nos. 1 and 2?

(2) I f so, when should such an election be held?

(3) Should the tiling for the respective District Board

of Trustees be reopened?

The South Carolina Attorney General responded to these

questions in a January 4, 1983 opinion. Referring to an

earlier Attorney General opinion that the proposed con-

Order of District Court) September 9, 1983

7a

solidation of Districts One and Two was of no effect, the

South Carolina Attorney General concluded that “ the pro

visions of Act [No. 549] are now in effect and it requires

that an election he held for the school trustees.” In re

sponse to Mr. Murdaugh’s question about the timing of

such an election, the South Carolina Attorney General

responded: “As soon as possible.” Finally, regarding the

question as to whether the filing period should be reopened,

South Carolina’s chief legal officer concluded that “ there

is no reason to reopen filing as only the date of the elec

tion has changed.” Acting upon this legal advice, the

Hampton County Election Commission published a Notice

of Election setting March 15, 1983, as election day.2

From the foregoing chain of events, plaintiffs have

identified five claimed Section 5 changes that they urge

were enforced without proper preclearance by the Hamp

ton County Election Commission. These alleged changes

are as follows:

(1) conducting an election for Trustees without first

certifying the results of the referendum to the

South Carolina. Code Commissioner as required

by Section 3 of Act No. 549 (R398);

(2) accepting of filings for the Trustees’ positions

after the Attorney General objected to Act No.

549;

(3) (a) conducting an election for Trustees without

first seeking authority for a filing period;

Order of District Court, September 9, 1983

2 Five Trustees were elected to the District Two Board on March

15, 1983, all of whom are black. One black person and four white

persons were elected Trustees of District One.

8a

(b) conducting an election for Trustees without

holding a filing period subsequent to withdrawal

of the Attorney General’s objection;

(4) conducting an election for Trustees after the May,

1982, date specified for such elections in Act No,

549; and

(5) the abolition of the office of the Hampton County

Superintendent of Education and the devolution

of his duties on the Trustees of Hampton County

School Districts One and Two.

In this court’s view, plaintiffs’ first contention does not

involve a change in voting practice or procedure within

the meaning of Section 5. Even though Section 3 of Act

No. 549 (R398) required certification of the results of the

referendum by the county election commission to the county

legislative delegation and the South Carolina Code Com

missioner, the failure of the election commissioner to so

certify is purely a state law problem. Moreover, the fail

ure of the election commissioner to certify the referendum,

results to the code commission is not alleged to have had

either racially discriminatory purpose or effect. Such an

allegation is essential to a Section 5 action. Otherwise,

federal courts “would henceforth be thrust into the details,

of virtually every election, tinkering with the state’s elec

tion machinery, reviewing petitions, registration cards,

vote tallies, and certificates of election for all manner of

error and insufficiency under state and federal law.” Powell

v. Power, 436 F.2d 84, 86 (2d Cir. 1970).

Plaintiffs’ second, third and fourth alleged changes also

fail to constitute “ changes” within the meaning of Section

5. Each of these acts were not alterations of South Caro

lina law, but rather were steps in the implementation of a

Order of District Court, September 9, 1983

9a

new statute. It is not questioned that Act No. 549 consti

tuted a Section 5 “ change” that require preclearance, hut

the administrative actions of accepting filings and con

ducting an election for Trustees was not a change in South

Carolina election law, but rather an effort to conform to

it. In this court’s view, the preclearance requirement of

Section 5 applied to the new statute, Act No. 549, requir

ing that it he precleared before becoming effective, while

the ministerial acts necessary to accomplish the statute’ s

purpose were not “ changes” contemplated by Section 5,,

and thus did not require preclearance.

Even if plaintiffs’ second, third and fourth alleged

changes were to be considered as “ changes” under Section

5, this court concludes that they have now been precleared

along with the remaining provisions of Act No. 549. The

fact that the eventual preclearance of Act No. 549 fol

lowed the filing period for the Trustees’ positions is not a

bar under Section 5. In Berry v. Doles, 438 U.S. 190 (1978),

the Supreme Court recognized the necessity of taking a

practical approach toward reducing the disruptive delays

frequently generated by requests for preclearance. The

Court in Berry was confronted with a Section 5 challenge

to a change in a Georgia statute regulating voting proce

dures for the election of the members of the Peach County

Board of Commissioners of Roads and Revenues. The

Berry case was filed four days prior to the contested elec

tion, and the election was held as planned. The three-

judge district court held that the change, which had not

been precleared at the time of the election, violated Sec

tion 5, but refused to set aside the election. On appeal,

the Supreme Court affirmed the finding of a Section 5 vio

lation, but reversed the denial of affirmative relief regard

ing the election. The Supreme Court concluded that the

Order of District Court, September 9, 1983

10a

appropriate remedy was to permit the responsible officials,

to have 30 days within which to apply pursuant to Section

5 for approval of the change in question. Citing Perkins

v. Matthews, 400 U.S. 379 (1971), the Court noted as.

follows:

We indicated in [Perkms] that “ [i]n certain circum

stances . . . it might be appropriate to enter an order

affording local officials an opportunity to seek federal

approval and ordering a new election only if local

officials fail to do so or if the required federal ap

proval is not forthcoming.” 400 TLS., at 396-397. The

circumstances present here make such a course ap

propriate.

In this case, appellees’ undisputed obligation to sub

mit the 1968 voting law change to a forum designated

by Congress has not been discharged. We conclude

that the requirement of federal scrutiny imposed by

§5 should be satisfied by appellees without further

delay. . . . I f approval is obtained, the matter will be

at an end.

438 U.S. at 192-193.

By its decision in Berry, the Supreme Court clearly in

dicated that a retroactive validation of an election law

change under Section 5 could be achieved by after-the-

fact federal approval. Thus, it is the court’s view that

in the case at bar the eventual preclearance of Act No. 549

ratified and validated for Section 5 purposes those acts of

implementation which had already been accomplished.

The fifth and final change asserted by the plaintiffs,

the abolition of the office of Hampton County Superin

tendent of Education and the devolution of his duties on

Order of District Court, September 9, 1983

11a

the Trustees, was provided for by Act No. 549.3 As in

dicated in the preceding discussion of the second, third,

and fourth alleged changes, this action was approved when

the Act itself was precleared by the Attorney General.

Thus, Section 5 does not reach this aspect of plaintiffs’

Complaint.

For the reasons set forth above, the court concludes

that the five instances alleged by the plaintiffs do not

represent changes in election practice or procedure within

the meaning of Section 5 of the Voting Eights Act of 1965

which were instituted without preclearance by the Attorney

General. Further, the alleged changes have in fact been

ratified and approved by the United States Attorney Gen

eral’s eventual preclearance of Act No. 549 in its entirety.

Therefore, the court denies plaintiffs’ request for injunc

tive relief and dismisses those portions of the Complaint

which seek any relief from this three-judge court under

Section 5 of the Voting Eights Act of 1965.

A nd It Is So Ordered.

/ s / E obert F. C hapman

Eobert F. Chapman

United States Circuit Judge

/ s / Charles E. Simons, Jr.

■Charles E. Simons, Jr.

United States District Judge

/ s / F alcon B. H awkins

Falcon B. Hawkins

United States District Judge

Order of District Court, September 9, 1983

3 The Hampton County Superintendent of Education was elected

for a four-year term commencing July 1, 1981 and expiring June

30,1985. Act No. 549 abolishes this position effective June 30, 1985.

10a

appropriate remedy was to permit the responsible officials,

to have 30 days within which to apply pursuant to Section

5 for approval of the change in question. Citing Perkins

v. Matthews, 400 U.S. 379 (1971), the Court noted as.

follows :

We indicated in [Perki/ns\ that “ [i] n certain circum

stances . . . it might be appropriate to enter an order

affording local officials an opportunity to seek federal

approval and ordering a new election only if local

officials fail to do so or if the required federal ap

proval is not forthcoming.” 400 U.S., at 396-397. The

circumstances present here make such a course ap

propriate.

In this case, appellees’ undisputed obligation to sub

mit the 1968 voting law change to a forum designated

by Congress has not been discharged. We conclude

that the requirement of federal scrutiny imposed by

§5 should be satisfied by appellees without further

delay. . . . I f approval is obtained, the matter will be

at an end.

438 U.S. at 192-193.

By its decision in Berry, the Supreme Court clearly in

dicated that a retroactive validation of an election law

change under Section 5 could be achieved by after-the-

fact federal approval. Thus, it is the court’s view that

m the case at bar the eventual preclearance of Act No. 549

ratified and validated for Section 5 purposes those acts of

implementation which had already been accomplished.

The fifth and final change asserted by the plaintiffs,

the abolition of the office of Hampton County Superin

tendent of Education and the devolution of his duties on

Order of District Court, September 9, 1983

11a

the Trustees, was provided for by Act No. 549.3 As in

dicated in the preceding discussion of the second, third,

and fourth alleged changes, this action was approved when

the Act itself was precleared by the Attorney General.

Thus, Section 5 does not reach this aspect of plaintiffs’

Complaint.

For the reasons set forth above, the court concludes

that the five instances alleged by the plaintiffs do not

represent changes in election practice or procedure within

the meaning of Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965

which were instituted without preclearance by the Attorney

General. Further, the alleged changes have in fact been

ratified and approved by the United States Attorney Gen

eral’s eventual preclearance of Act No. 549 in its entirety.

Therefore, the court denies plaintiffs’ request for injunc

tive relief and dismisses those portions of the Complaint

which seek any relief from this three-judge court under

Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

A nd It Is So Ordered.

/ s / R obert F. C hapman

Robert F. Chapman

United States Circuit Judge

/ s / Charles E. Simons, Jr.

Charles E. Simons, Jr.

United States District Judge

/ s / F alcon B. H awkins

Falcon B. Hawkins

United States District Judge

Order of District Court, September 9, 1983

3 The Hampton County Superintendent of Education was elected

for a four-year term commencing July 1, 1981 and expiring June

30,1985. Act No. 549 abolishes this position effective June 30, 1985.

12a

Notice of Appeal

I n the

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F ob the D istrict oe S outh Carolina

A iken D ivision

Filed October 10, 1983

Civil Action No. 83-612-6

National A ssociation fob the A dvancement of

Colored P eople, I nc., etc., et al.,

Plaintiffs,

v.

H ampton County E lection Commission, etc., et al.,

Defendants.

Plaintiffs National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People, Inc., Hampton County, South Carolina,

Branch of the National Association for the Advancement

of Colored People, Inc., Benjamin Brooks, Jack J. Deloach,

Jessie M. Taylor, Rev. Ernest McKay, Sr., Soletta Taylor,

Jesse Lee Carr, W. M. Hazel, John Henry Martin, Wash

ington G. Garvin, Jr., Dora E. Williams, James Fennell,

Vernon McQuire, Bosie Green and Earl Capers, hereby

appeal to the Supreme Court of the United States from

the order of the District Court denying injunctive relief

on the claims based upon 42 U.S.C. Section 1973c entered

in this case on September 9, 1983. This appeal is taken

13a

Notice of Appeal

pursuant to 28 U.S.C. Section 1253 and 42 U.S.C. Section

1973c.

/ s / John R. H arper II

John R. H arper II

3706 North Main Street

Post Office Box 843

Columbia, South Carolina 29202

(803) 799-2798

T homas I. A tkins

Margrett F ord

186 Remsen Street

Brooklyn, New York 11201

(212) 858-0800

Columbia, South Carolina

October 10, 1983.

14a

Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, as amended,

42 U.S.C. § 1973c, provides:

§ 1973c. Alteration of voting qualifications and pro

cedures; action by State or political sub

division for declaratory judgment of no

denial or abridgement of voting rights;

three-judge district court; appeal to Su

preme Court

Whenever a State or political subdivision with re

spect to which the prohibitions set forth in section

1973b(a) of this title based upon determinations made

under the first sentence of section 1973b (b) of this title

are in effect shall enact or seek to administer any

voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, or stan

dard, practice, or procedure with respect to voting

different from that in force or effect on November 1,

1964, or whenever a State or political subdivision with

respect to which the prohibitions set forth in section

1973b(a) of this title based upon determinations made

under the second sentence of section 1973b (b) of this

title are in effect shall enact or seek to administer any

voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, or stan

dard, practice, or procedure with respect to voting

different from that in force or effect on November 1,

1968, or whenever a State or politcal subdivision with

respect to which the prohibitions set forth in section

1973b(a) of this title based upon determinations made

under the third sentence of section 1973b(b) of this

title are in effect shall enact or seek to administer any

voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, or stan

dard, practice, or procedure with respect to voting

Voting Rights Act of 1965, Section 5

15a

different from that in force or effect on November 1,

1972, such State or subdivision may institute an ac

tion in the United States District Court for the Dis

trict of Columbia for a declaratory judgment that

such qualification, prerequisite, standard, practice, or

procedure does not have the purpose and will not

have the effect of denying or abridging the right to

vote on account of race or color, or in contravention

of the guarantees set forth in section 1973b(f)(2) of

this title, and unless and until the court enters such

judgment no person shall be denied the right to vote

for failure to comply with such qualification, prerequi

site, standard, practice, or procedure: Provided, That

such qualification, prerequisite, standard, practice, or

procedure may be enforced without such proceeding

if the qualification, prerequisite, standard, practice,

or procedure has been submitted by the chief legal

officer or other appropriate official of such State or

subdivision to the Attorney General and the Attorney

General has not interposed an objection within sixty

days after such submission, or upon good cause shown,

to facilitate an expedited approval within sixty days

after such submission, the Attorney General has af

firmatively indicated that such objection will not be

made. Neither an affirmative indication by the At

torney General that no objection will be made, nor

the Attorney General’s failure to object, nor a declara

tory judgment entered under this section shall bar

a subsequent action to enjoin enforcement of such

qualification, prerequisite, standard, practice, or pro

cedure. In the event the Attorney General affirma

tively indicates that no objection will be made within

the sixty-day period following receipt of a submis

Voting Rights Act otf 1965, Section 5

16a

sion, the Attorney General may reserve the right to

reexamine the snbmisson if additional information

comes to his attention during the remainder of the

sixty-day period which would otherwise require ob

jection in accordance with this section. Any action

under this section shall be heard and determined by

a court of three judges in accordance with the provi

sions of section 2284 of Title 28 and any appeal shall

lie to the Supreme Court.

Voting Rights Act of 1965, Section 5

17a

Act No. 547, South Carolina Laws 1982, provides:

Composition of Hampton County Board of Education

Section 1. Notwithstanding any other provision of

law, beginning January 1, 1983, the Hampton County

Board of Education shall he constituted and elected

as follows:

A. (1) Six members shall be elected at large from

the county in an election conducted by the county elec

tion commission at the time general elections are held

beginning with the general election of 1982.

(2) To have his name placed on the ballot a person

must file with the election commission, not less than

forty-five days before the election, a petition signed

by not less than fifty qualified electors of the county.

Each signature 'shall be followed by the voter regis

tration number of the petitioner. Petitions must be

approved by the county board of voter registration.

(3) No political party designation shall appear on

the ballot in connection with the names of candidates.

(4) The six candidates receiving the highest vote in

the election shall be declared elected. In the event of

a tie vote, procedures provided in the state election

laws shall apply.

B. Terms of members shall be for four years and

until their successors are elected and qualify except

that in the initial election of 1982 the three members

elected who receive the smallest vote shall serve ini

tial terms of two years only.

C. Vacancies shall be filled in the next general elec

tion for a full term or unexpired term as the case may

Act No. 547, South Carolina Laws (1982)

18a

be except that if a vacancy occurs more than one year

prior to a general election it shall be filled by appoint

ment by the Governor upon recommendation of a ma

jority of the county legislative delegation for a period

until the vacancy can be filled by election.

D. In addition to the elected members, the county

superintendent of education shall serve ex officio as

a member of the board and in such capacity shall have

all rights and privileges of other board members, in

cluding the right to vote.

E. As of December 31, 1982, the terms of all board

members then serving shall expire.

F. Except as provided in this act the poAvers, duties

and procedures of the board as prescribed by laAv shall

continue in full force and effect.

Time effective

Section 2. This act shall take effect upon approval

by the Governor.

Act No. 547, South Carolina Laws (1982)

19a

Act No. 549, South Carolina Laws, provides:

Board of education abolished, trustees elected

Section 1. Contingent upon approval of the total

proposal by a majority of the qualified electors voting

in a referendum to be held in May, 1982, as hereafter

provided for, the following shall occur:

(a) The Hampton County Board of Education shall

be abolished at midnight on June 30, 1982; the office

of the Hampton County Superintendent of Education

shall be abolished at midnight on June 30, 1985; upon

abolition their respective duties shall devolve upon

the trustees for Hampton County School Districts

Nos. 1 and 2; and after June 30, 1982, the Hampton

County Treasurer shall pay any proper claim ap

proved by a majority of the trustees of either School

District No. 1 or School District No. 2, on behalf of

their respective districts, provided sufficient funds are

on deposit in the proper district account.

(b) Beginning with the general election in Novem

ber, 1982, trustees for Hampton County School Dis

tricts Nos. 1 and 2 shall be elected by a plurality vote

of the electors within their respective district qualified

and voting at the general election for representatives.

The number of trustees shall be five for each school

district and their terms of office shall begin January

1, 1983. The three candidates in each district receiv

ing the highest number of votes shall serve for terms

of four years and the remaining two trustees shall

have initial terms of two years, after which all terms

shall be for four years. In each case trustees shall

serve until their successors are elected and qualify

Act No. 549, South Carolina Laws (1982)

20a

and each school board shall elect its chairman annually.

Trustees shall receive no salary but shall be reim

bursed for actual expenses incurred. A candidate for

membership on a school board must reside in the school

district he seeks to represent and all candidates offer

ing for election in November, 1982, must file during

the period August 16-31, 1982.

Beferendum conducted

Section 2. The Hampton County Commissioners of

Election shall conduct a referendum within the respec

tive county school districts during May, 1982, to deter

mine whether the provisions of Section 1 of this act

shall be implemented. The specific date for the ref

erendum shall be determined by the county election

commission. The county election commission shall

thrice publish notice of the referendum in a news

paper of a countywide circulation, the last publica

tion to be not less than one nor more than two weeks

before the referendum. All election laws contained in

Title 7 of the 1976 Code applicable to county refer-

endums shall apply. Ballots shall be prepared and dis

tributed to the various voting precincts of the county

with the following printed thereon:

“ Shall the Hampton County Board of Education be

abolished on June 30, 1982, and its duties placed upon

the trustees for Hampton County School Districts

Nos. 1 and 2; shall the office of the Hampton County

Superintendent of Education be abolished on June 30,

1985, and its duties placed upon the trustees for

Hampton County School Districts Nos. 1 and 2; and

shall the trustees for Hampton County School Dis-

Act No. 549, South Carolina Laws (1982)

21a

tricts Nos. 1 'and 2 (five trustees per district), rather

than being appointed, be elected by plurality vote dur

ing general elections for representatives beginning

with the election in Novembr, 1982, with their terms

to begin January 1, 1983, and with terms of office to

be four years, except that of those initially elected

two from each district shall have initial terms of two

years ?

I agree to the above proposals □ Yes □ No

Place a check or cross mark in the block which ex

presses your answer.”

Results certified

Section 3. The Hampton County Commissioners of

Election shall certify the results of the referendum

directed in Section 2 of this act to the Hampton County

Legislative Delegation and to the South Carolina Code

Commissioner.

Act No. 549, South Carolina Laws (1982)

MEIIEN PMSS INC. — N. Y. C.