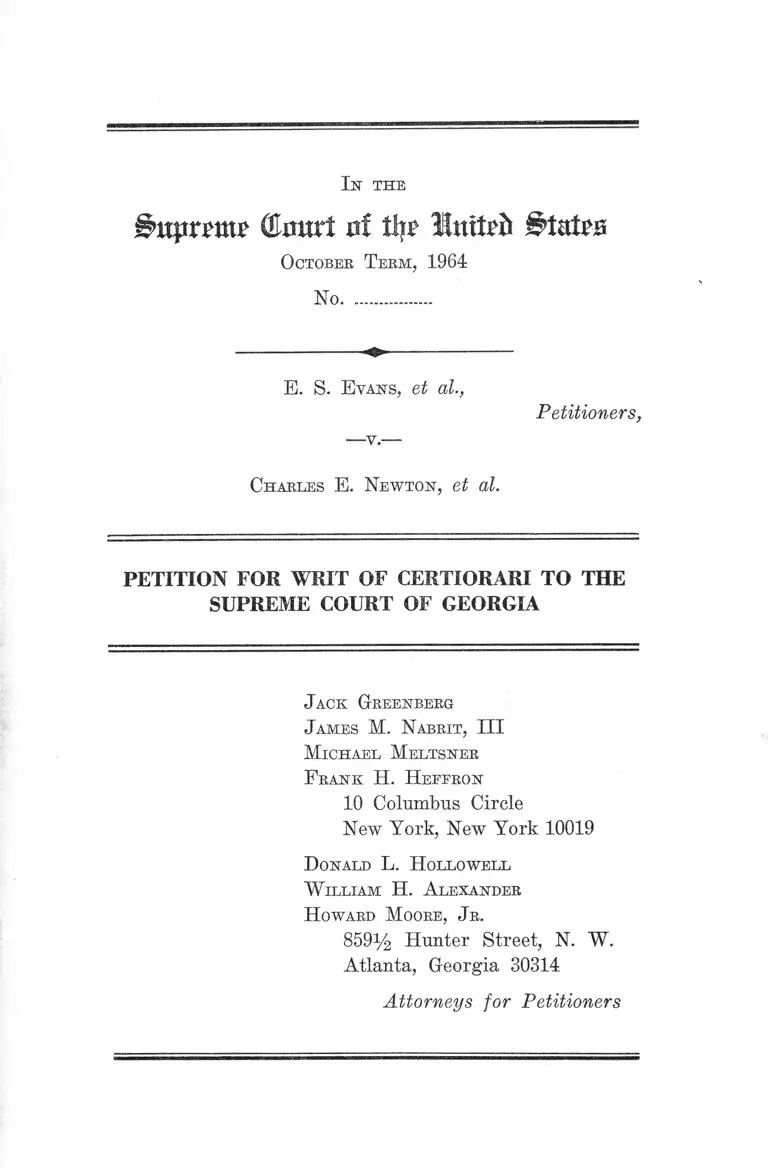

Evans v. Newton Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Georgia

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Evans v. Newton Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Georgia, 1964. 08a81542-b19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/17024885-b66f-4b8e-9ddd-2ab0918dc151/evans-v-newton-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-supreme-court-of-georgia. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

j^ttprem? ©Hurt of % Itttteft States

October Term, 1964

No..................

E. S. E vans, et al,

Petitioners,

—v.—

Charles E. Newton, et al.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Michael Meltsner

F rank H. IIeferqn

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

D onald L. H ollowell

W illiam H. A lexander

H oward Moore, Jr.

859% Hunter Street, N. W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30314

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

Opinion Below ......................... .......................................... 1

Jurisdiction ............ .............. ......... ..................................... 2

Questions Presented ..................................... ................... . 2

Statutory and Constitutional Provisions Involved____ 3

Statement ..... ..... ..... ....................... ......... .......... .............. 5

How the Federal Questions Were Raised and Decided

Below ............... ..................... .............. ..... ....... ....... ...... 9

Reasons for Granting the Writ .......... ..................... ...... 12

I. This Case Involves Enforcement by the State

of Racial Discrimination in Violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment ..... ............ .......... ....... 12

II. The State of Georgia and the City of Macon

Are So Involved in the Operation of Bacons-

field as to Invalidate Under the Fourteenth

Amendment Any Enforcement of the Racially

Discriminatory Terms of Senator Bacon’s

Will ..... .......................................... ................... . 17

Conclusion..................... .......... ............. ....... ..................... 25

A ppendix....... ............ ..... ......... ................ .......... ......... ..... . la

Opinion of Supreme Court of Georgia _______ __ la

Judgment of Supreme Court of Georgia ........... 10a

Order of Supreme Court of Georgia Denying

Rehearing ........................ .......... ................... .......... 10a

PAGE

n

Letter Opinion of Superior Court of Bibb County .. 11a

Order of Superior Court of Bibb County............... 13a

PAGE

Table of Cases

Adams v. Bass, 18 Ga. 130 (1855) ..... ...... .......... ........... 19

American Colonization Society v. Gartrell, 23 Ga. 448

(1858) ............................................................................... 19

Beckwith v. Rector, etc., of St. Philip’s Parish, 69 Ga.

564 (1882) ................................ ...... .................................. 21

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S.

715 ........................................................................ 17,20

Charlotte Park and Recreation Comm’n v. Barringer,

242 N. C. 311, 88 S. E. 2d 114 (1955), cert, denied,

350 IT. S. 983 ......................... .............. ................. ......... . 14

Cox v. De Jarnette, 104 Ga. App. 664, 123 S. E. 2d 16

(1961) ................................. 22

Creech v. Scottish Rite Hosp. for Crippled Children,

211 Ga. 195, 84 S. E. 2d 563 (1954) .............................. 16

Eaton v. Grubbs, 329 F. 2d 710 (4th Cir. 1964) ....... 21, 24

Emory University v. Nash, 218 Ga. 317, 127 S. E. 2d

798 (1962) ................. .............. ................ ..................... . 21

Estate of Stephen Girard, 391 Pa. 434, 138 A. 2d 844

(1958) .............. ..11,15

Goree v. Georgia Industrial Home, 187 Ga. 368, 200

S. E. 684 (1938) ............. ................... ......... ................... 21

Guillory v. Administrators of Tulane University, 212

F. Supp. 674 (E. D. La. 1962) .................. .................... 16

Holmes v. City of Atlanta, 350 U. S. 879 12

Ill

Jones v. City of Atlanta, 35 App. 376, 133 S. E. 521

(Ga. Ct. App. 1926) .............. .......... ............... ............. 23

Leeper v. Charlotte Park and Recreation Comm’n, 2

Race Rel. L. Rep. 411 (Super. Ct. Mecklenburg

County 1957) ......... .... ....... ........ ......... ................. ..... . 14

Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U. S. 267 .......................15,16,17

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501 .................... ...... ....... 24

Morehouse College v. Russell, 219 Ga. 717, 135 S. E. 2d

432 (1964) ____________ ____________ ______ __________ 22

Morehouse College v. Russell, 109 Ga, App. 301, 136

S. E. 2d 179 (1964) .......................... ........ ........... .......... 22

Morton v. Savannah Hospital, 148 Ga. 438, 96 S. E.

887 (1918) ................................ ...................................... 22

Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical Ass’n, 347 U. S.

971 ..................................................................................... 12

Murphy v. Johnston, 190 Ga. 23, 8 S. E. 2d 23 (1940) ... 23

Pace v. Dukes, 205 Ga. 835, 55 S. E. 2d 367 (1949) 23

Pennsylvania v. Board of Directors of City Trusts

of the City of Philadelphia, 353 U. S. 230 ......... 11,12,13,

14,15,17

Pennsylvania v. Board of Directors of City Trusts

of the City of Philadelphia, 357 U. S. 570 ..... ......... 11,15

Peterson v. City of Greenville, 373 U. S. 244 .....15,16,17,

19, 20

Regents of University System v. Trust Company of

Georgia, 186 Ga. 498, 198 S. E. 345 (1938) ......... 23

Rice University v. Carr, 9 Race Rel. L. Rep. 613 (D. C.

Harris County, Tex. 1964), appeal dismissed, No.

14,472, Tex. Ct. Civ. App., February 4, 1965 ........... 16

Robinson v. Florida, 378 U. S. 153...... ............. ...11, 16,17,19

PAGE

IV

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 ...................................... 14,15

Simians v. Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital, 323

F. 2d 929 (4th Cir. 1963), cert, denied, 376 U. S.

938 ........................................ ...... ........ ............... .. .......... 24

Simpson v. Anderson, 220 Ga. 155, 137 S. E. 2d 638

(1964) ................................ .......... .......... ..... ............ . 21

Smith v. Allright, 321 U. S. 649 ........... ......................... . 24

Stubbs v. City of Macon, 78 Ga. App. 237, 50 S. E. 2d

866 (1948) ........................... 22

Terry v. Adams, 345 U. S. 461..... .............. .............. ....... 24

Turner v. City of Memphis, 369 IT. S. 350 ....................... 17

Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 IT. S. 562 ................. 12

Statutes

28 IT. S. C. §1257(3) ..................................... ............... . 2

Const. Ga. 1877, art. 7, sec. 2, par. 1, Ga. Code Ann.

§2-5002 ................ 20

Const. Ga. 1945, art. 7, sec. 1, par. 4, Ga. Code Ann.

§2-5404 ......... ......................... ............... .......... .................. 3, 21

Ga. Code Ann. §69-301 ................. ....... ..... ........ ....... . 22

Ga. Code Ann. §69-504 .............. ....................... 5, 9,10,11,14,

18,19, 21, 23

Ga. Code Ann. §69-505 ................................................ ..... 20

Ga. Code Ann. §§69-601 through 69-616.......................... 24

Ga. Code Ann. §85-707 .................................. ............ ....... 23

Ga. Code Ann. §92-201 ..................................................... 4, 21

Ga. Code Ann. §108-201 ............................................... 21

PAGE

V

Ga. Code Ann. §108-202 _______ __ ____________......10,16, 22

Ga. Code Ann. §108-203 ...................................................... 21

Ga. Code Ann. §108-204 .......................................... ........... 22

Ga. Code Ann. §§108-206 through 108-209 ................ 22

Ga. Code Ann. §108-212 (1963 Supp.) .......................... 22

Pa. Stat. Ann., tit. 18, §4654 .............................. ..... ......... 15

PAGE

Other A uthorities

American Bar Association, Canons of Professional

Ethics, No. 10 ....................................................... ..... . 16

Clark, Charitable Trusts, the Fourteenth Amendment,

and the Will of Stephen Girard, 66 Yale L. J. 979

(1957) ..................... ............................ ................. ........... 24

Woodward, The Strange Career of Jim Crow, Ch. II

(1957) ........ ........... ........................................................... 19

In t h e

(Eflurt of % Imtpf* States

October Term, 1964

No..................

E. S. E vans, et al.,

Petitioners,

Charles E. Newton, et al.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to re

view the judgment of the Supreme Court of Georgia in

the case of E. S. Evans, et al. v. Charles E. Newton, et al.,*

entered on September 28, 1964. Rehearing was denied on

October 8,1964. Mr. Justice Stewart, on December 22, 1964,

granted an order extending the time for filing this petition

for writ of certiorari to and including March 5, 1965.

Opinion Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Georgia (R. 132) is

reported at 138 S. E. 2d 573 and is set forth in the appendix

infra, p. la.

* Petitioners are E. S. Evans, Louis H. Wynn, J. L. Key, Booker

W. Chambers, William Randall, and Van J. Malone. The respon

dents are all parties who were defendants in error in the Supreme

Court of Georgia. See note 5 infra.

2

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of Georgia in this

case was entered on September 28, 1964 (R. 147). Rehear

ing was denied October 8, 1964 (R. 153). On December 22,

1964, Mr. Justice Stewart extended the time for filing the

petition for writ of certiorari to and including March 5,

1965.

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to

Title 28, U. S. C. §1257(3), petitioners having asserted

below and asserting here deprivation of rights, privileges

and immunities secured by the Constitution of the United

States.

Questions Presented

1. Land was left in trust to the City of Macon, Georgia,

for use as a public park for the exclusive use of white

women and children; the city administered the park on a

discriminatory basis through an appointed board of man

agers; after Negroes were allowed to use the park, the city

and the board of managers petitioned a court of equity to

appoint new trustees so that Negroes might be excluded

from the park; the court appointed new trustees for that

purpose. Is the state thereby enforcing racial discrimina

tion contrary to the Fourteenth Amendment?

2. In the above circumstances a state statute authorized

gifts of land in trust for the establishment of parks

limited to white women and children; the state granted

tax exemption to such trusts only if use of such parks were

limited according to race; the state by law encouraged the

establishment of charitable trusts to fulfill a public function

of providing public recreational facilities; the state granted

3

limited liability in tort eases to such charitable institutions;

the state granted them perpetual existence, unlike non-

charitable trusts; and the City of Macon administered the

park for years on a discriminatory basis. Has the state

become involved in the operation of the park to such an

extent as to require the applicability of the equal protection

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment?

Statutory and Constitutional Provisions Involved

This case involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.

This case also involves the following constitutional and

statutory provisions of the State of Georgia:

Const. Ga. 1945, art. 7, sec. 1, par. 4, Ga. Code Ann.

§2-5404:

Exemptions from taxation.—The General Assembly

may, by law, exempt from taxation all public property;

places of religious worship or burial and all property

owned by religious groups used only for residential

purposes and from which no income is derived; all

institutions of purely public charity; all intangible per

sonal property owned by or irrevocably held in trust

for the exclusive benefit of, religious, educational and

charitable institutions, no part of the net profit from

the operation of which can inure to the benefit of any

private person; all buildings erected for and used as a

college, incorporated academy or other seminary of

learning, and also all funds or property held or used

as endowment by such colleges, incorporated academies

or seminaries of learning, provided the same is not in

vested in real estate; and provided, further, that said

exemptions shall only apply to such colleges, incorpo

4

rated academies or other seminaries of learning as are

open to the general public; provided further, that all

endowments to institutions established for white peo

ple, shall be limited to white people, and all endow

ments to institutions established for colored people,

shall be limited to colored people; . , .

Gu. Code Ann. §92-201:

Property exempt from taxation.—The following de

scribed property shall be exempt from taxation, to w it:

All public property; places of religious worship or

burial, and all property owned by religious groups used

only for single family residences and from which no

income is derived; all institutions of purely public char

ity ; hospitals not operated for the purpose of private or

corporate profit and income; all intangible personal

property owned by or irrevocably held in trust for the

exclusive benefit of, religious, educational and chari

table institutions, no part of the net profit from the

operation of which can inure to the benefit of any pri

vate person; all buildings erected for and used as a

college, nonprofit hospital, incorporated academy or

other seminary of learning, and also all funds or prop

erty held or used as endowment by such colleges; non

profit hospitals, incorporated academies or seminaries

of learning, providing the same is not invested in real

estate; and provided, further, that said exemptions

shall only apply to such colleges, nonprofit hospitals,

incorporated academies or other seminaries of learn

ing as are open to the general public: Provided, fur

ther, that all endowments to institutions established

for white people, shall be limited to white people, and

all endowments to institutions established for colored

people, shall be limited to colored people; . . .

5

Ga. Code Ann. §69-504:

Gifts for public parks or pleasure grounds.—Any

person may, by appropriate conveyance, devise, give, or

grant to any municipal corporation of this State, in

fee simple or in trust, or to other persons as trustees,

lands by said conveyance dedicated in perpetuity to the

public use as a park, pleasure ground, or for other

public purpose, and in said conveyance, by appropriate

limitations and conditions, provide that the use of said

park, pleasure ground, or other property so conveyed

to said municipality shall be limited to the white race

only, or to white women and children only, or to the

colored race only, or to colored women and children

only, or to any other race, or to the women and children

of any other race only, that may be designated by said

divisor or grantor; and any person may also, by such

conveyance, devise, give, or grant in perpetuity to such

corporations or persons other property, real or per

sonal, for the development, improvement, and mainte

nance of said property.

Statement

This suit was commenced by some of the respondents to

effect the banishment of Negroes from a public park estab

lished in Macon, Georgia under the will of Augustus Oc

tavius Bacon, a United States senator from Georgia. The

will of Senator Bacon (R. 19), executed on March 28, 1911,1

provided in Item 9th for a gift of real property to the City

of Macon as owner and trustee for the maintenance of a

park for the white women and children2 of the City of

1A codicil was added September 6, 1913 (R. 43).

2 The Board of Managers was given discretion to open the park

to white men and white non-residents of Macon (R. 31). This

power was exercised (R. 15).

6

Macon, under the supervision of a Board of Managers ap

pointed by the Mayor and Council (R. 27). The will set

aside a separate fund in trust to defray expenses of ad

ministering the park (R. 34). The park, named Baconsfield,

was operated in accordance with the racial limitation in

Bacon’s will until a short time before this suit was insti

tuted, when Negroes were allowed to use the park (R. 15).

On May 4, 1963, Charles E. Newton and other members

of the Board of Managers of Baconsfield3 filed a petition

in the Superior Court of Bibb County, Georgia, requesting

the removal of the City of Macon as trustee, the appoint

ment of new trustees, and the transfer of title in Bacons

field to newly appointed trustees. Named as defendants

were the City of Macon and the trustees of certain residu

ary legatees of Bacon’s estate, the Curry heirs.4 This relief

was sought explicitly for the purpose of enforcing the ra

cially discriminatory terms of Bacon’s will (R. 12-17).

The City of Macon filed its answer (R. 47) admitting

most allegations of the petition, but stating that it had

“ no authority to enforce racially discriminatory restric

tions with regard to property held in fee simple or as trus

tees for a private or public trust and, as a matter of law,

is prohibited from enforcing such racially discriminatory

restrictions” (R. 48). The defendant trustees for the Curry

heirs filed their answer admitting all allegations of the

petition and joining in “ each and every prayer of said

petition” (R. 51); they were represented by the same coun

sel as the plaintiff members of the Board of Managers (R.

3 The Board of Managers did not sue as an entity. Each member

sued, through private counsel, in his capacity as member of the

Board (R. 12).

4 The trustees for the Curry heirs were Guyton G. Abney,

J. D. Crump, T. I. Denmark and Dr. W. G. Lee (R. 12).

7

17, 51). Plaintiffs filed a motion for summary judgment

(E. 54).

On May 29, 1963, a diversity of interest appeared in this

lawsuit for the first time when Rev. E. S. Evans and five

other Negro citizens of the City of Macon, petitioners here,

moved for leave to file a petition in intervention (R. 56).

In their intervention petition of June 18, 1963, the Negro

intervenors alleged that the appointment of new trustees

of the park in order to comply with the racial limitation in

Bacon’s will would violate the Fourteenth Amendment (R.

61). The intervenors requested that the Superior Court

“ effectuate the general charitable purpose of the testator

to establish and endow a public park within the City of

Macon by refusing to appoint private persons as trustees”

of the park (R. 62-63). Their petition also challenged the

plaintiffs’ standing to sue (R. 63).

On January 8, 1964, the plaintiff members of the Board

of Managers filed an amendment to their original petition

requesting that all Negroes be enjoined from using the

park (R. 65). The amendment requested the addition as

plaintiffs of four previously unrepresented residuary lega

tees under Bacon’s will, the Sparks heirs (R. 66); a request

was also made that the trustees of the Curry heirs, origi

nally joined as defendants, be permitted to assert the in

terests of the Curry heirs as plaintiffs (R. 67). Simul

taneously, the Sparks heirs intervened, asking that all

relief requested by the original plaintiffs be granted (R.

69). Also at the same time, the trustees for the Curry

heirs asked to be allowed to assert their interests as plain

tiffs, and joined in all of the plaintiffs’ prayers for relief

(R. 72). In addition, the Sparks heirs and the trustees for

the Curry heirs, all of whom were represented by counsel

for the plaintiff Board members, asked for reversion of

the trust property into Bacon’s estate in the event that

other relief were denied (R. 70, 74).

8

On February 5, 1964, the City of Macon, the only defen

dant making any pretense of defending the suit, amended

its answer stating that the City had resigned as trustee of

Baconsfield (R. 94) pursuant to resolution of the Mayor

and Council on February 4, 1964 (R. 79), and requesting

the court’s acceptance of its resignation and the appoint

ment of substitute trustees (R. 76).

On May 5, 1964, the Negro intervenors amended their

petition, alleging that the Fourteenth Amendment would

be violated if the relief sought by the other parties were

granted (R. 95).

No evidentiary hearing was held. The Superior Court

issued its decree on March 10, 1964, allowing intervention

by all who had requested it, accepting the resignation of

the City of Macon as trustee of Baconsfield, appointing

three private individuals as new trustees, and retaining

jurisdiction of the case (R. 99). No ruling was made on

the requests that Negroes be enjoined from using the park.

The conditional prayers for reversion of the trust property

were deemed moot (R. 100).

Appeal was taken to the Supreme Court of Georgia by

petitioners, the Negro intervenors.5 On September 28, 1964,

the Supreme Court of Georgia affirmed the judgment of

5 The defendants in error on the appeal were the City of Maeon,

the four Sparks heirs, the four trustees for the Curry heirs, and

the three newly appointed trustees of the park. By amendment to

the bill of exceptions, ̂the original plaintiffs, the members of the

Board of Managers of Baconsfield, were added as defendants in

error on the appeal (R. 105, 110, 130). Subsequent to the decree

of the Superior Court, all seven members of the Board of Man

agers of Baconsfield submitted their resignations to the three newly

appointed trustees of the park (R. 115). The trustees then re

appointed three of the members of the Board of Managers and

substituted four new members of the Board (R. 116). All members

of the Board of Managers, whether original appointees or new

appointees, "were made parties to the appeal (R. 131).

9

the Superior Court of Bibb County. A motion for rehear

ing was denied on October 8, 1964 (R. 153).

How the Federal Questions Were Raised

and Decided Below

The federal constitutional issues, on which this case

turned, were raised at the outset by the Negro intervenors,

petitioners here, in their intervention petition (R. 59).

There it was alleged that enforcement of the racial limita

tion in Bacon’s will by a court of the State of Georgia “ is

violative of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United

States Constitution” (R. 61). It was also alleged that “dis

crimination based solely upon race is no longer a permis

sible object of state action whether such action is that of

an administrative agency, the state executive officers and

employees, the state legislature, or the state courts” (R.

62). The intervenors requested that the Superior Court

“ effectuate the general charitable purpose of the testator”

by refusing to appoint private trustees (R. 62-63).

Following the intervention of Bacon’s heirs and the res

ignation of the City of Macon, the Negro intervenors

amended their petition, alleging: 1) that the “ equal pro

tection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United

States Constitution prohibits this Court from enjoining

Negroes from use of the park” , 2) that “ the equal protec

tion clause of the Fourteenth Amendment” prohibits ac

ceptance of the City’s resignation and the appointment of

new trustees “ for the purpose of enjoining [sic] [enforc

ing] the racially discriminatory provision in the will of

A. 0. Bacon,” 3) that §69-504 of the Georgia Code6 “pre

scribes racial discrimination and is therefore violative of

6 Section 69-504 of the Georgia Code authorized gifts of prop

erty to municipalities for the operation of parks “for white women

and children” and other racially designated classes, supra, p. 5.

10

the equal protection clause to the Fourteenth Amendment” ,

and 4) that §108-202 of the Georgia Code (the cy pres

provision) “ properly construed, requires that the racially

discriminatory provision in A. 0. Bacon’s will be declared

null and void” (R. 95-96).

The order of the Superior Court of Bibb County rejected

the constitutional claims of the Negro intervenors by im

plication (R. 99). Upon issuing its order and decree, Judge

Long of the Superior Court wrote a letter to counsel for

all parties stating that the “ racial limitation in Senator

A. O. Bacon’s will is not unlawful for any reason as con

tended by the intervenors, Reverend E. S. Evans, et al.”

The letter also said that the appointment of new trustees

was proper since the City of Macon, acting as trustee,

could not “ apply constitutionally the racial criterion pre

scribed by the testator.” The doctrine of cy pres was held

to be inapplicable to this trust. Appendix, infra, p. 11a.

On appeal the Supreme Court of Georgia affirmed the

ruling of the Superior Court (R. 147), deciding all issues

adversely to petitioners. In its opinion the Supreme Court

of Georgia stated: “ Counsel for the plaintiffs in error

(the Negro intervenors) assert that the decree of the

judge of the superior court was ‘patent enforcement of

racial discrimination contrary to the equal protection

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment’ to the Federal Con

stitution” (R. 141). The court rejected this contention. It

also held that Ga. Code Ann. §69-504 did not require that

Senator Bacon’s gift to the City include a racial limitation

and held that such a racial limitation was not invalid (R.

142-143). The Supreme Court of Georgia rejected peti

tioners’ contention that the racial limitation should be

stricken under the cy pres doctrine (R. 143-144). Finally,

it held that the action of the Superior Court in accepting

the City’s resignation as trustee and appointing private

11

trustees was consistent with this Court’s ruling in Penn

sylvania v. Board of Directors of City Trusts of the City

of Philadelphia, 353 U. S. 230, pointing out that the Su

preme Court of Pennsylvania subsequently approved the

appointment of private trustees for Girard College and

this Court dismissed the appeal and denied certiorari,

Estate of Stephen Girard, 391 Pa. 434,138 A. 2d 844 (1958);

Pennsylvania v. Board of Directors of City Trusts of the

City of Philadelphia, 357 U. S. 570 (R. 144-146).

Petitioners moved for a rehearing, contending that Ga.

Code Ann. §69-504, providing for gifts of real property to

municipalities for the benefit of white persons or for the

benefit of Negro persons, brought this case within the hold

ing of this Court in Robinson v. Florida, 378 U. S. 153,

which held that a state regulation requiring desegregated

restaurants to provide racially separate rest-room facilities

constituted state encouragement of segregation in violation

of the Fourteenth Amendment (R. 149). The Supreme

Court of Georgia denied rehearing without opinion (R.

153).

12

Reasons for Granting the Writ

The decision below conflicts with applicable decisions

of this Court on important constitutional issues.

I.

This Case Involves Enforcement by the State of

Racial Discrimination in Violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

This is a classic case of state enforcement of racial dis

crimination by every branch of government, legislative,

executive, administrative, and judicial. The responsibility

of each branch is no less than in the many cases prohibiting

discrimination in public recreational facilities, e.g., Wat

son, v. City of Memphis, 373 U. S. 562; Holmes v. City of

Atlanta, 350 U. S. 879; Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical

Ass’n, 347 U. S. 971.

The suit began when the members of the Board of Man

agers of Baconsfield, who had been enforcing racial dis

crimination for generations, sued for relief that would

enable them to resume the practice. Under Bacon’s will,

the Board members were appointees of the Mayor and

Council of Macon' with the sole function of administering

the park owned in trust by the City (R. 31). They must be

regarded as part of the administration of the City of

Macon. See Pennsylvania v. Board of Directors of City

Trusts, 353 U. S. 230.

Significantly, the Board of Managers did not sue as a

collective entity, but each member sued individually in his

capacity as a member of the Board. Presumably, if the 7

7 All seven appointees must be white, at least four must be women

and one should be a descendant of Senator Bacon, if possible (r !

13

Board had sued as a body, it would have been entitled, as

a municipal agency, to representation by the City Attor

ney. Since the principal defendant was the City of Macon,

the nonadversary, sham nature of the suit would have been

exposed from the beginning if this had occurred. In any

event, the Board members suing individually were treated

as competent parties.

The involvement of the executive and legislative branches

of City government is evident also. In the first instance,

the City failed to exercise its control over its own litigation

by preventing the suit altogether. As defendant, the City

put up the weakest kind of defense. It did not even sug

gest to the Superior Court that the Board members, suing

individually, lacked the capacity to represent an agency of

the City (R. 47). At no time did the City raise any objec

tions, constitutional or otherwise, to the transfer of its

public park to other trustees (R. 49). Eventually, the City,

acting through its Mayor and Council, caved in completely,

voluntarily submitting its resignation (R. 94), and joining

in the plaintiffs’ request that the new trustees be appointed

so that Negroes could be excluded again from Baconsfield

(R. 76).

Undoubtedly the City could have prevented the result

brought about by this suit. Several municipalities have

received gifts from private donors mandating racial dis

crimination in the use of the property transferred. Faced

with the conflict between the terms of the gift and the re

quirements of the Constitution, they have continued to use

donated resources and ignored governmentally unenforce

able limitations rather than devise schemes for private dis

criminatory operation.8 In the Girard College Case, where

8 The City of Charlotte purchased the reversionary interest from

the heirs of a testator who required racial discrimination, so that

the City could continue to provide recreational facilities for its

14

the Board of Directors of City Trusts was a statutory body

with independent power to sue, the City of Philadelphia

and the State of Pennsylvania entered the suit through

their official counsel, respectively, on the side of the Four

teenth Amendment, 353 U. S. 230. By contrast, the Mayor

and the Council of the City of Macon bear direct, if

not primary, responsibility for the racial discrimination

brought about by this suit.

The responsibility of Georgia’s judiciary is apparent on

the surface. Two of Georgia’s courts held that the dis

criminatory terms of a private instrument must be given

effect, despite the Fourteenth Amendment, to insure the

exclusion of Negroes from a place of public accommodation.

It is submitted that this result was foreclosed by Shelley

v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1.

In many ways, state involvement was less clear in

Shelley than here. In Shelley, the instrument containing

the discriminatory clause was an agreement between pri

vate parties, in which the state had no part. The lawsuit in

Shelley represented a genuine controversy between private

parties—Negroes who wanted to maintain their home and

other home owners who wanted to secure the exclusion of

Negroes from the neighborhood, a putative right obtained

in the bargaining process. Finally, the subject of the law

suit in Shelley was a private home, rather than a place of

public accommodation.

In this case, the racial limitation was encouraged by,

imposed upon, and accepted by the state. Section 69-504

of the Georgia Code invited Senator Bacon to restrict use

citizens, Leeper v. Charlotte Park and Recreation Comm’n, 2 Race

Eel. L. Rep. 411 (Super. Ct. Mecklenburg County 1957), even

though the racial limitation had been held valid, Charlotte Park

and Recreation Comm’n v. Barringer, 242 N. C. 311, 88 S. E. 2d

114 (1955), cert, denied, 350 U. S. 983.

15

of the park to the women and children of one race.” The

limitation was accepted and enforced by the City and its

agents for many years, including several years following

this Court’s decision in the Girard College Case. In the

spring of 1963, a turning point for civil rights in this coun

try, Negroes were allowed to use the recreational facilities

of Baconsfield because the City recognized that overt en

forcement of discrimination by the state would no longer be

tolerated. But City officials promptly went to court and

asked that private trustees be substituted so that discrim

ination could be reintroduced under private supervision.

Whether the original proponents be viewed as City

agents or the City itself, it was an instrumentality of the

state that sought judicial enforcement of discrimination

in this case. Cf. Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U. S. 267,

where an official policy of segregation in restaurants was

held to invalidate trespass convictions of Negroes who

challenged that policy. It is of minor importance that the

racial limitation on use of Baconsfield can be traced to an

individual owner of private property. That was true in

the first Girard College Case, 353 IT. S. 230, where it was

held that the policy could not be enforced by a state

agency.9 10 It was also true in Shelley v. Kraemer. More

over, this Court held in Peterson v. City of Greenville, 373

9 See pp. 18-20, infra.

10 In the second Girard College Case, the Supreme Court of

Pennsylvania approved the appointment of private trustees to con

tinue discriminatory operation. Estate of Stephen Girard, 391

Pa. 434, 138 A. 2d 844 (1958), appeal dismissed and cert, denied,

357 U. S. 570. Petitioners challenge the correctness of the ruling

of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania. This Court’s refusal to

review may be read in the light of the possible availability of relief

for the Negro plaintiffs in the courts of Pennsylvania under Pa.

Stat. Ann., tit. 18, §4654, forbidding racial discrimination in “pri

mary and secondary schools, high schools, academies, colleges and

universities, extension courses and all educational institutions un

der the supervision of this Commonwealth. . . . ”

1 6

U. S. 244, that there are times when the private role in

originating officially enforced policies of discrimination

will not be considered. See also Lombard v. Louisiana, 373

U. S. 267 and Robinsonv. Florida, 378 U. S. 153.

Nor is it important that the private heirs of Senator

Bacon joined with the members of the Board of Managers

in the request for enforcement of the restriction in Bacon’s

will. They did so only as an afterthought, and they were

represented by the same attorneys as the Board members.

Thus their interests must have been identical with those

of the Board members. See American Bar Association,

Canons of Professional Ethics, No. 10.

Finally, it should be noted that the courts of Georgia

refused to apply the doctrine of cy pres. Under this doc

trine, which is firmly established in Georgia as a means

of effectuating a testator’s charitable intent, see Ga. Code

Ann. §108-202; Creech v. Scottish Rite Hosp. for Crippled

Children, 211 Ga. 195, 84 S. E. 2d 563 (1954), the Superior

Court could have ensured the maintenance of a public park,

permitted white persons to continue using it, and retained

City administration by refusing to appoint new trustees.

Instead it chose the course which would permit racial dis

crimination. Compare Guillory v. Administrators of Tulane

University, 212 F. Supp. 674, 687 (E. D. La. 1962) (admin

istrators under discriminatory will allowed to desegre

gate) ; Rice University v. Carr, 9 Race Rel. L. Rep. 613

(D, C. Harris County, Tex. 1964), appeal dismissed, No.

14,472, Tex. Ct. Civ. App., February 4, 1965 (same).

17

II.

The State o f Georgia and the City o f Macon Are So

Involved in the Operation o f Baconsfield as to Invali

date Under the Fourteenth Amendment Any Enforce

ment o f the Racially Discriminatory Terms o f Senator

Bacon’ s Will.

As this Court held in Burton v. Wilmington Parking Au

thority, 365 U. S. 715, 722, discrimination by private entities

is invalid under the Fourteenth Amendment if “ to some

significant extent the State in any of its manifestations has

been found to have become involved in it.” In Burton and

in Turner v. City of Memphis, 369 U. S. 350, this reasoning

was held to justify injunctive relief against the institutions

practicing discrimination. In Peterson v. City of Green

ville, 373 U. S. 244, the same reasoning was applied to in

validate criminal trespass convictions, where a local or

dinance required discrimination by private restaurateurs.

See also Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U. S. 267; Robinson v.

Florida, 378 U. S. 153. It is submitted that the involvement

of the State of Georgia and the City of Macon in the opera

tion of Baconsfield invalidates the result reached in this

case.

One factor meriting serious consideration under this

heading is the fact that racial discrimination has been en

forced by each department of government, as pointed out in

the previous argument. Another factor of significance is the

continuous ownership and operation of Baconsfield on a

discriminatory basis for a substantial length of time. It is

settled under the first Girard College Case that continued

operation by municipal authorities would make further ex

clusion of Negroes impossible. The question now presented

is whether it is possible to wipe away the effects of city

administration merely by appointing new trustees.

18

According to Bacon’s will, the Board of Managers was

given “ complete and unrestricted control and management

of the said property with power to make all needful regu

lations for the preservation and improvement of the

same . . . ” (R. 31). Bacon provided funds for

the management, improvement and preservation of said

property, including when possible drives and walks,

casinos and parlors for women, playgrounds for girls

and boys and pleasure devices and conveniences and

grounds for children, flower yards and other orna

mental arrangements . . . (R. 32).

He expressed the hope that the Board of Managers would

preserve his two houses (R, 33) and “ the present woods

and trees” on the property (R. 34). In the years of their

administration the City and the Board of Managers have

exercised the discretion granted them. They have decided

what types of facilities to provide, what buildings to pre

serve and for what purposes, and whether to alter the land

scape. The City was in control during the years when

Baconsfield took shape as an institution open to the public.

The effects of its administration remain.

A fact of critical importance in this case is the State of

Georgia’s responsibility for the original restriction of

Baconsfield to a distinct racial group. Section 69-504 of

the Georgia Code, enacted in 1905, well before Bacon pub

lished his carefully drafted will, provides:

Any person may, by appropriate conveyance, devise,

give, or grant to any municipal corporation of this

State, in fee simple or in trust, or to other persons as

trustees, lands by said conveyance dedicated in per

petuity to the public use as a park, pleasure ground,

or for other public purpose, and in said conveyance, by

appropriate limitations and conditions, provide that the

19

use of said park, pleasure ground, or other property

so conveyed to said municipality shall be limited to the

white race only, or to white women and children only,

or to the colored race only, or to colored women and

children only, or to any other race, or to the women

and children of any other race only, that may be desig

nated by said devisor or grantor; and any person may

also, by such conveyance, devise, give, or grant in per

petuity to such corporations or persons other property,

real or personal, for the development, improvement,

and maintenance of said property.

Many choices were offered to donors. Lands could be dedi

cated to the exclusive use of the white race, the colored

race, or any other race, or the women and children of the

white race, the colored race, or any other race. But no

choice was offered for those who might have preferred to

endow an integrated park.

The Supreme Court of Georgia held in this case that

§69-504 did not require that gifts be limited racially (R.

142), but no such construction was in existence to guide

testators and their attorneys in 1911 when Bacon wrote

his will. Men are careful to conform to the letter of the

law when preparing their wills. This statute was passed

during the time when segregation laws were sweeping the

South, see Woodward, The Strange Career of Jim Crow,

Ch. II (1957), and its words revealed a separatist intent.

The unhappy fate of pre-Civil War testamentary trusts for

the emancipation or resettlement of slaves stood as a warn

ing to any who might depart from the explicit directions of

the statute. See Adams v. Bass, 18 Ga. 130 (1855); Amer

ican Colonization Society v. Gartrell, 23 Ga, 448 (1858).

The rule of Peterson v. City of Greenville, 373 IT. S. 244

and Robinson v. Florida, 378 U. S. 153 applies. The State

2 0

of Georgia suggested that Senator Bacon limit his gift to

one of several racial classes, and he did so, following the

words of the statute very closely (R. 30). In these circum

stances, Senator Bacon’s personal motives—explicitly set

forth at some length in his will (R. 32-33)—are of no conse

quence; “ a palpable violation of the Fourteenth Amendment

cannot be saved by attempting to separate the mental urges

of the discriminators.” Peterson v. City of Greenville, 373

IT. S. 244, 248. Georgia expressly authorized racial restric

tions in §69-504 and, in a companion statute, §69-505, offered

enforcement of them through the police power.11 See Burton

v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S. 715, 726

(Stewart, J., concurring).

Reinforcing these statutes, the law of Georgia has for

many years conditioned tax exemption on the existence of

segregation. At least since 1877, the Constitution has au

thorized exemption from taxation for “all institutions of

purely public charity.” Ga. Const. 1877, art. 7, sec. 2, par. 1,

Ga. Code Ann. §2-5002. In 1918 an amendment to the Con

stitution included a proviso that “ all endowments to insti

tutions established for white people, shall be limited to

white people, and all endowments to institutions established

for colored people, shall be limited to colored people; . . . ”

Editorial note, Ga. Const. 1877, art. 7, sec. 2, par. 1, Ga.

11 Ga. Code Ann. §69-505 provides:

Municipality authorized to accept.—Any municipal corpora

tion, or other persons natural or artificial, as trustees, to whom

such devise, gift, or grant is made, may accept the same in

behalf of and for the benefit of the class of persons named in

the conveyance, and for their exclusive use and enjoyment;

with the right to the municipality or trustees to improve,

embellish, and ornament the land so granted as a public park,

or for other public use as herein specified, and every municipal

corporation to which such conveyance shall be made shall

have power, by appropriate police provision, to protect the

class of persons for whose benefit the devise or grant is made,

in the exclusive used and enjoyment thereof.

21

Code Ann. §2-5002. This exemption and proviso were car

ried over into the statute setting forth tax exemptions, (la.

Code Ann. §92-201, and readopted in the Georgia Constitu

tion of 1945, art. 7, sec. 1, par. 4, Ga. Code Ann. §2-5404.12

Tax exemption is always a valuable subsidy, and “may

attain significance when viewed in combination with other

attendant state involvements.” Eaton v. Grubb.s, 329 F. 2d

710 (4th Cir. 1964). Senator Bacon was eager to obtain tax

exemption for Baconsfield, providing in his will that a

special statute should be sought if tax exemption should

be denied (R. 32). In Georgia tax exemption is dependent

upon the erection of racial barriers.

The Baconsfield trust, created pursuant to Ga. Code Ann.

§69-504, is but one of several types of charitable trusts to

which the State extends support in numerous ways in addi

tion to tax exemption. See Ga. Code Ann. §108-203. The

courts of Georgia have often remarked that charitable

trusts are looked upon with special favor. See, e.g., Simp

son v. Anderson, 220 Ga. 155, 137 S. E. 2d 638 (1964);

Goree v. Georgia Industrial Home, 187 Ga. 368, 200 S. E.

684 (1938) and cases cited; Beckwith v. Rector, etc., of

St. Philip’s Parish, 69 Ga. 564 (1882). The statutes of

Georgia reflect this solicitude, providing for the enforce

ment of charitable trusts in equity, Ga. Code Ann. §108-201,

the effectuation of the testator’s intent under the cy pres

12 In Emory University v. Nash, 218 Ga. 317, 127 S. E. 2d 798

(1962), the Supreme Court of Georgia held that the proviso on

racial limitation could not be applied to deprive a desegregated

university of its tax exemption because the racial proviso was incon

sistent with another proviso stipulating that tax exemption should

only apply to “such colleges, incorporated academies or other

seminaries of learning as are open to the general public,” Ga. Code

Ann. §92-201. However, because there is no conflicting statute

requiring that tax exempt parks be open to the general public,

Georgia’s law continues to condition tax exemption of parks on

the maintenance of racial limitations.

22

doctrine, §108-202, and continuous supervision by equity

courts, §108-204. Particular favoritism is extended to chari

table trusts in §§108-206 through 108-209, which lay down

rules of procedure and construction directed toward up

holding the validity of attempted charitable trusts. Chari

table, or public, trusts are enforced in the courts by the

Attorney General or the solicitor general of the circuit

in which the trust corpus lies. Ga. Code Ann. §108-212

(1963 Supp.).

One of the many ways the State of Georgia supports

charitable trusts is by extending them immunity from suit

in certain tort situations. Under the present rule, an in

stitution’s charitable assets cannot be recovered by a per

son claiming negligence of the institution’s employees.

Morehouse College v. Bussell, 219 Ga. 717, 135 S. E. 2d

432 (1964); id., 109 Ga. App. 301, 136 S. E. 2d 179 (1964);

Cox v. De Jarnette, 104 Ga. App. 664,123 S. E. 2d 16 (1961);

Morton v. Savannah Hospital, 148 Ga. 438, 96 S. E. 887

(1918). Noncharitable assets, such as money received for

services or a liability insurance policy, can be recovered

by one suing under respondeat superior, and all assets are

subject to recovery for administrative negligence, or the

torts of the institution as opposed to its employees. Ibid.

Nonetheless, Georgia continues to offer charitable enter

prises a substantial degree of immunity from suit, with

very little doctrinal change having occurred in the last fifty

years. See Morton v. Savannah Hospital, supra.

Georgia has a comparable doctrine of immunity from

suit for municipalities where a governmental function is

being performed. Ga. Code Ann. §69-301. It has been held

that maintaining a park is a governmental function, so that

the municipality is immune from liability for the acts of

its officers or employees in connection with the park. Stubbs

v. City of Macon, 78 Ga. App. 237, 50 S. E. 2d 866 (1948);

23

Another incident of charitable trusts in Georgia, illus

trating the support offered them by the state and their simi

larity to governmentally owned and operated institutions,

is perpetual existence. Georgia retains in its law of pri

vate, or noncharitable, trusts, the traditional rule against

perpetuities limiting their duration to “ lives in being . . . ,

and 21 years, and the usual period of gestation added there

after.” Ga. Code Ann. §85-707. However, the rule against

perpetuities does not apply to charitable trusts. Regents

of University System v. Trust Company of Georgia, 186

Ga. 498, 512, 198 S. E. 345 (1938); Murphy v. Johnston,

190 Ga. 23 (7), 8 S. E. 2d 23 (1940); Pace v. Dukes, 205

Ga. 835, 55 S. E. 2d 367 (1949). In the case of Baconsfield,

perpetual existence is guaranteed by §69-504.

This element of perpetual existence is a factor of major

significance. It is axiomatic that a man has a right to exer

cise his prejudices in the use of his private property during

his life, and to dispose of his property by will, making irra

tional choices about its recipients and uses. But no man

has the right to control his property through eternity. The

law sets temporal limits on testamentary encumbrances,

and in the exceptional situation of the charitable trust it

exercises close supervision. In this case Georgia has not

only given Bacon’s trust perpetual existence, but has exer

cised its broad powers to assure the maintenance of segre

gation to the end of time.

It has been shown that charitable trusts—whether the

trustees be public or private—are carefully nurtured by

the State of Georgia, as by other states. The reason the

state fosters these institutions to such a degree lies in the

fact that charitable trusts perform many functions often

Jones v. City of Atlanta, 35 App. 376, 133 S. E. 521 (Ga.

Ct. App. 1926).

24

performed by the state. See Clark, Charitable Trusts, the

Fourteenth Amendment, and the Will of Stephen Girard,

66 Yale L. J. 979, 1010 (1957). As an example, Baconsfield,

established under a charitable trust, serves as a public rec

reational facility for some of the citizens of Macon. The

provision of recreational facilities is a public function un

der the laws of Georgia. Ga. Code Ann. §§69-601 through

69-616 authorizes municipalities to set aside existing public

property or acquire new property for use as parks, play

ground and recreation centers.

Thus Baconsfield was set up under one of several gov-

ernmentally developed methods of providing public parks.

The Constitution forbids racial restrictions in public facil

ities established by government ; it would be anomalous if

public parks set up under other, equally effective, govern-

mentally fostered plans could be so restricted. In analogous

situations, the Fourth Circuit has held that medical facilities

operated by private groups under comprehensive state plans

to provide health facilities for all citizens are subject to the

nondiscrimination requirements of the Fourteenth Amend

ment. Simkins v. Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital, 323

F. 2d 929 (4th Cir. 1963), cert, denied, 376 U. S. 938; Eaton

v. Grubbs, 329 F. 2d 710 (4th Cir. 1964). Cf. Smith v. All-

wright, 321 U. S. 649, Terry v. Adams, 345 U. S. 461.

Indeed, this Court’s decision in Marsh v. Alabama, 326

U. S. 501 requires the desegregation of Baconsfield. Since

the company town in Marsh was like any other town in all

respects except ownership, the commands of the Fourteenth

Amendment were held to be applicable. Apart from its

previous ownership, Baconsfield is no different from, any

other public park.

25

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons the petition for writ of

certiorari should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Michael Meltsner

F rank H. Heeeron

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Donald L. H ollowell

W illiam H. A lexander

H oward Moore, Jr.

859^ Hunter Street, N. W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30314

Attorneys for Petitioners

A P P E N D I X

APPENDIX

In the Supreme Court oe Georgia

22534

Decided Sept. 28, 1964

209

Evans e t a l. v. Newton e t a l.

The record does not support the contentions of the plain

tiffs in error, and the judge could not properly have gone

beyond the judgment rendered. The judgment is not shown

to be erroneous for any of the reasons urged by counsel

for the plaintiffs in error.

Opinion o f Supreme Court o f Georgia

The will of A. 0. Bacon (which was probated in solemn

form) in Item Nine gave in trust described property, to be

known as “Baconsfield” , to named trustees for the benefit

of his wife and two named daughters for their joint use,

benefit, and enjoyment during the term of their natural

lives. It was provided that upon the death of the last sur

vivor, the property, including all remainders and rever

sions, “ shall thereupon vest in and belong to the Mayor

and Council of the City of Macon, and to their successors

forever, in trust for the sole, perpetual and unending, use,

benefit and enjoyment of the white women, white girls, white

boys and white children of the City of Macon to be by

them forever used and enjoyed as a park and pleasure

ground, subject to the restrictions, government, manage

ment, rules and control” of a board of managers consist

ing of seven persons, not less than four to be white women

and all seven to be white persons. In order to provide for

the maintenance of the park, income from described real

property and bonds was to be expended by the board of

managers.

2a

Charles E. Newton and others, as members of the Board

of Managers of Baconsfield, brought an equitable petition

against the City of Macon (in its capacity as trustee under

Item Nine of the will of A. 0. Bacon), and Guyton G.

Abney and others, as successor trustees under the will

holding assets for the benefit of certain residuary bene

ficiaries. It was alleged: The city as trustee holds the

legal title to a tract of land in Macon, Bibb County, known

as Baconsfield, under Item Nine of the will of A. 0. Bacon.

As directed in the will, the board through the years has

confined the exclusive use of Baconsfield to those persons

designated in the will. The city is now failing and refusing

to enforce the provisions of the will with respect to the

exclusive use of Baconsfield. Such conduct on the part of

the city constitutes such a violation of trust as to require

its removal as trustee. It was prayed that: the city be

removed as a trustee under the will; the court enter a de

cree appointing one or more freeholders, residents of the

city, to serve as trustee or trustees under the will; legal

title to Baconsfield and any other assets held by the city

as trustee be decreed to be in the trustee or trustees so

appointed for the uses originally declared by the testator;

and for further relief.

The City of Macon filed its ansiver asserting that it can

not legally enforce racial segregation of the property known

as Baconsfield, and therefore it is unable to comply with

the specific intention of the testator with regard to main

taining the property for the exclusive use, benefit, and en

joyment of the white women, white girls, white boys, and

white children of the city. The city prayed that the court

construe the will and enter a decree setting forth the duties

and obligations of the city in the premises. The other de

fendants admitted the allegations of the petition and

Opinion of Supreme Court of Georgia

3a

prayed that the city be removed as a trustee. The peti

tioners thereafter filed a motion for summary judgment.

Reverend E. S. Evans and others, alleging themselves

to be Negro residents of the City of Macon, on behalf of

themselves and other Negroes similarly situated, filed an

intervention in the cause and asserted: The restriction and

limitation reserving the use and enjoyment of Baconsfield

Park to “white women, white girls, white boys and white

children of the City of Macon,” is violative of the public

policy of the United States of America and violative of the

Constitution and laws of the State of Georgia. The court

as an agency of the State of Georgia cannot, consistently

with the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment of the Constitution of the United States and the

equivalent provision of the Constitution of the State of

Georgia, enter an order appointing private citizens as trus

tees for the manifest purpose of operating, managing, and

regulating public property (which passed to the City of

Macon under a charitable trust created by will) in a racially

discriminatory manner. Although the charitable devise at

the time of its creation was capable of being executed in

the exact manner provided by the will, by operation of law

it is no longer capable of further execution in the exact

manner provided for by the testator. The court should

effectuate the general charitable purpose of the testator to

establish and endow a public park by refusing to appoint

private persons as trustees.

By amendment to the petition it was alleged: By the

will of A. 0. Bacon a trust was established for his heirs.

The trust has been executed as to four of his seven heirs

now living, A. 0. B. Sparks, Willis B. Sparks, Jr., Virginia

Lamar Sparks, and M. Garten Sparks. The interests of

three remaining heirs, Louise Curry Williams, Shirley

Opinion of Supreme Court of Georgia

4a

Curry Cheatham, and Manley Lamar Curry, are still held

under an executed trust by four trustees holding under

the authority of the will, these trustees being Guyton Ab

ney, J. D. Crump, T. I. Denmark, and Dr. W. G. Lee. These

seven persons have an interest in the litigation since, if

the trust purpose expressed in the will with respect to the

designation of persons who may use Baconsfield should

fail, the property comprising Baconsfield, together with

the property providing the upkeep of Baconsfield, will re

vert to the estate of A. 0. Bacon and be distributed to

these heirs. The amendment prayed that the Sparks heirs

be allowed to intervene and that the trustees be allowed to

assert the interests of the other heirs. It was also prayed

that the Negro intervenors and other members of the Negro

race resident in Macon be permanently enjoined from en

tering and using the facilities of Baconsfield. The Sparks

heirs and the trustees of the other heirs of A. 0. Bacon

filed an intervention praying that the relief sought by the

original petitioners be granted, but that if such relief not

be granted, the property revert to them.

The City of Macon filed an amendment to its answer,

alleging that pursuant to resolution adopted by the Mayor

and Council of the city at its regular meeting on February

4, 1964, the city has resigned as trustee under the will of

A. 0. Bacon. It prayed that the resignation be accepted

by the court.

The Negro intervenors filed an amendment to their inter

vention in which they asserted: The equal protection clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Con

stitution prohibits the court from enjoining Negroes from

the use of the park, and from accepting the resignation of

the City of Macon as trustee and apointing new trustees

for the purpose of enjoining (enforcing!) the racially dis

Opinion of Supreme Court of Georgia

5a

criminatory provision in the will of A. 0. Bacon. Code

§ 69-504 prescribes racial discrimination and is therefore

violative of the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the United States Constitution. Since the

racially discriminatory provision in the will was dictated

by that unconstitutional statute, enforement of the racially

discriminatory provision is constitutionally prohibited.

Code § 108-202, properly construed, requires that the ra

cially discriminatory provision in the will be declared null

and void. The interveners prayed that the court withhold

approval of the attempted resignation of the city as trus

tee under the will, direct the city to continue to administer

the park on a racially nondiscriminatory basis, and deny

the injunction sought by the petitioners to exclude Negroes

from the use of the park.

On March 10, 1964, the judge of the superior court en

tered an order and decree in the case which adjudged as

follows: (1) The intervenors named are proper parties in

the case and are proper representatives of the class which

their intervention states that they represent, the Negro

citizens of Bibb County and the City of Macon. (2) The

defendants, Gluyton G. Abney, J. D. Crump, T. I. Denmark,

and Dr. W. G-. Lee, as successor trustees under the will

of A. O. Bacon, and intervenors A. 0. B. Sparks, Willis

B. Sparks, Jr., Virginia Lamar Sparks and M. Garten

Sparks are also proper parties. (3) The City of Macon

having submitted its resignation as the trustee of the prop

erty known as Baconsfield, the resignation is accepted by

the court. (4) Hugh M. Comer, Lawton Miller, and B. L.

Bagister are appointed as trustees to serve in lieu of the

City of Macon. (5) The court retains jurisdiction for the

purpose of appointing other trustees that may be neces

sary in the future. (6) It is unnecessary to pass upon the

Opinion of Supreme Court of Georgia

6a

secondary contention of the intervenors Guyton G. Abney

and others.

Reverend E. S. Evans and others in their writ of error

to this court assign error on this order of the trial judge.

Their contentions will appear from the opinion.

Opinion of Supreme Court of Georgia

A lmand, Justice. Counsel for the plaintiffs in error (the

Negro intervenors) assert that the decree of the judge of

the superior court was “ patent enforcement of racial dis

crimination contrary to the equal protection clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment” to the Federal Constitution. The

decree did not enforce, or purport to enforce, any judgment,

ruling, or decree as related to the intervenors. After deter

mining that all parties were properly before the court, the

decree did two things: (1) Accepted the resignation of the

City of Macon as trustee of Baeonsfield, and (2) appointed

new trustees.

“The law of charities is fully adopted in Georgia . . . ”

Jones v. Habersham, 107 U. S. 174(5). Under the law of

this State any person may, by will, grant, gift, deed, or

other instrument, give or devise property for any charitable

purpose. Ga. L. 1937, p. 593 (Code Ann. 108-207). Any

public convenience might be a proper subject for a chari

table trust. Code 108-203. A charity once established is

always subject to supervision and direction by a court of

equity to render effectual its purpose. Code 108-204. It

is the rule that a charitable trust shall never fail for the

want of a trustee. Code 108-302.

Whether the will of A. O. Bacon, establishing a trust for

the operation of Baeonsfield, contemplated by the language

“to the Mayor and Council of the City of Macon and to

their successors [italics ours]” that the named trustee

might resign, need not be determined. The City of Macon

did resign, and the judge of the superior court was con

7a

fronted with the commandment of Code 108-302 that a trust

shall never fail for the want of a trustee. Being empowered

to appoint trustees when a vacancy occurs for any cause

(Thompson v. Hale, 123 Ga. 305, 51 S E 383; Harris v.

Brown, 124 Ga. 310(2), 52 S E 610; Woodbery v. Atlas

Realty Co., 148 Ga. 712, 98 S E 472; Sparks v. Ridley, 150

Ga. 210(3), 103 S E 425), the judge exercised such power

and appointed successor trustees.

The contention by counsel for the plaintiffs in error that

Code 69-504 required A. O. Bacon to limit the use of Bacons-

field to the members of one race cannot be sustained. Code

69-504, in providing for gifts limited to members of a race,

simply states that any person may “ devise, give, etc.” The

law of Georgia does not by Code 69-504, nor by any other

statutory provision, require that any testator shall limit

his beneficence to any particular race, class, color, or creed.

Such limitation, however, standing alone, is not invalid, and

this Court has sustained a testamentary charity naming

trustees for establishing and maintaining “ a home for

indigent colored people 60 years of age or older residing

in Augusta, Georgia.” Strother v. Kennedy, 218 Ga. 180

(127 SE2d 19). A. O. Bacon had the absolute right to give

and bequeath property to a limited class.

Counsel for the plaintiffs in error assert that: “As the

City was unable to comply with the racially discriminatory

direction of the trust, three alternatives were open to the

lower court: (1) declare the racially discriminatory pro

vision null and void; (2) remove the trustee (or accept its

resignation) and appoint a non-governmental trustee; (3)

declare failure of the trust.” They insist that the judge

should have chosen the first alternative.

Counsel for plaintiffs in error assert that the court

should have applied the provisions of Code 108-202 that

Opinion of Supreme Court of Georgia

8a

when a valid charitable bequest is incapable for some rea

son of exact execution in the exact manner provided by the

testator a court of equity will carry it into effect in such

way as nearly as possible to effectuate his intention. The

answer to this contention is : the application of the cy pres

rule, as provided in this code section, was not invoked by

the primary parties to this case, and even if it be conceded

(which we do not concede, see Smith v. Manning, 153 Gfa.

209, 116 S E 813 and Fountain v. Bryan, 176 Ga. 31, 166

S E 766) that the intervenors could raise such issue, the

facts before the trial judge were wholly insufficient to

invoke a ruling that the charitable bequest was or was not

incapable for some reason of exact execution in the exact

manner provided by the testator. There is no testimony in

the record of any nature or character that the board of

managers provided by the will cannot operate the park

pursuant to the terms and conditions of the will.

Counsel for the plaintiffs in error cite Pennsylvania v.

Board of Directors of City Trust of the City of Philadel

phia, 353 IT. S. 230. In the Pennsylvania case the United

States Supreme Court pointed out that the board which

operated Girard College was an agency of the State of

Pennsylvania by legislative act, and that the refusal to

admit Negroes to Girard College was therefore discrimina

tion by the State. Upon the return of the case to the Su

preme Court of Pennsylvania for further proceedings not

inconsistent with the opinion, that court remanded the case

to the Orphans’ Court for further proceedings not incon

sistent with the opinion of the Supreme Court of the United

States. The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, on the sec

ond appearance of the case (see Girard College Trustee

ship, 391 Pa. 434), stated that the Orphans’ Court con

strued the United States Supreme Court’s opinion to mean

Opinion of Supreme Court of Georgia

9a

that the Board of City Trusts was constitutionally incap

able of administering Girard College in accordance with the

testamentary requirements of the founder, and the Orphans’

Court entered a decree removing the Board as trustee of

Girard College and substituting therefor thirteen private

citizens, none of whom held any public office or otherwise

exercised any governmental power under the Common

wealth of Pennsylvania. The Supreme Court of Pennsyl

vania affirmed this action on review, and again sustained

action denying admission to Girard College by the Negro

applicants. Counsel for the defendants in error cite Girard

College Trusteeship, 391 Pa. 434, and strongly rely on this

Pennsylvania case. (On review by the United States Su

preme Court the motion to dismiss was granted, and treat

ing the record as a petition for certiorari, certiorari was

denied. Pennsylvania v. Board of Directors of City Trust

of Pennsylvania, 357 U. S. 570. A motion for rehearing was

denied. 358 U. S. 858.) In so far as the Girard College

Trusteeship case is applicable on its facts to the present

case, it supports the rulings we have made.

The record does not sustain the contentions of the plain

tiffs in error, and the judge could not properly have gone

beyond the judgment rendered. This judgment is not shown

to be erroneous for any of the reasons urged by counsel

for the plaintiffs in error.

Judgment affirmed. All the Justices concur.

Opinion of Supreme Court of Georgia

10a

Supreme Court of Georgia

Atlanta, September 28,1964

The Honorable Supreme Court met pursuant to adjourn

ment. The following judgment was rendered:

E. S. Evans et al. v. Charles E. Newton et al.

This case came before this court upon a writ of error

from the Superior Court of Bibb County; and, after argu

ment had, it is considered and adjudged that the judgment

of the court below be affirmed. All the Justices concur.

Judgment o f Supreme Court o f Georgia

Order of Supreme Court of Georgia Denying Rehearing

Supreme Court of Georgia

Atlanta, October 8,1964

The Honorable Supreme Court met pursuant to adjourn

ment. The following order was passed:

E. S. Evans et al. v. Charles E. Newton et al.

Upon consideration of the motion for a rehearing filed

in this case, it is ordered that it be hereby denied.

11a

STATE OF GEORGIA

Superior Courts of the Macon J udicial Circuit

Macon, Georgia

Chambers of:

Oscar L. L ong

H al B ell

W. D. A ultman

Judges

Mr. A. 0. B. Sparks, Jr.

J ones, Sparks, Benton & Cork

Attorneys at Law

Persons Building

Macon, Georgia

Mr. T rammell F. Shi

Attorney at Law

Southern United Building

Macon, Georgia

Mr. Donald L. H ollo well

Attorney at Law

859% Hunter Street, N. W.

Atlanta, Georgia

R e : Charles E. Newton, et al. v.

The City of Macon, et al.,

No. 25864, Bibb Superior Court.

Gentlemen:

After careful consideration of the Motion for Summary

Judgment in the above stated case, I have reached the

following conclusions.

Letter Opinion o f Superior Court o f Bibb County

Bibb, Crawford

Peach and Houston

March 10, 1964 Counties

12a

The racial limitation in Senator A. 0. Bacon’s will is

not unlawful for any reason as contended by the inter

veners, Reverend E. S. Evans, et al.

The inability of the City of Macon, as Trustee, to apply

constitutionally the racial criterion prescribed by the testa

tor for use of the property as a park for white women and

white children affected the trustee and not the trust, and

the City having tendered its resignation as trustee, it is

proper that the Court accept the resignation and appoint

private trustees who can carry out the purpose and intent

of the testator as set forth in the will.

It is my opinion that the doctrine of Cy Pres cannot be

applied to Baconsfield. There is no general charitable pur

pose expressed in the will. It is clear that the testator

sought to benefit a certain group of people, i.e., “ the white

women, white girls, white boys and white children of the

City of Macon” , and it is clear that he sought to benefit

them only in a certain way, i.e., by providing them with a

park or playground. Senator Bacon could not have used

language more clearly indicating his intent that the bene

fits of Baconsfield should be extended to white persons only,

or more clearly indicating that this limitation was an es

sential and indispensable part of his plan for Baconsfield.

The Court has, therefore, this day signed and filed with

the Clerk of this Court an order and decree, a copy of which

is herewith enclosed.

Yours truly,

/ s / 0. L. Long

OLL:ese

CC: Mr. Romas Ed Raley, Clerk

Bibb Superior Court

Macon, Georgia

Letter Opinion of Superior Court of Bibb Comity

13a

Order o f Superior Court o f Bibb County

No. 25864

B ibb Superior Court

B ill in E quity

Charles E. Newton, et al.

v.

City of Macon, et al.

Order and Decree

The Motion for Summary Judgment filed in behalf of

petitioners in the above captioned matter having come on

regularly to be heard, and the Court having duly considered

all pleadings filed in behalf of all parties to said cause and

the briefs filed in behalf of petitioners and the intervenors

Rev. E. S. Evans, Louis H. Wynne, Rev. J. L. Key, Rev.

Booker W. Chambers, William Randall, and Rev. Van J.

Malone, it is

Considered, ordered and adjudged as follows:

(1) The intervenors named above are proper parties to

this case and are proper representatives of the class which