Lorance v. AT&T Technologies, Inc. Reply Brief for Petitioners

Public Court Documents

February 26, 1988

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Lorance v. AT&T Technologies, Inc. Reply Brief for Petitioners, 1988. 9f9ad8a9-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/17aac5b5-6e6c-409c-bdb4-b2df5da01d61/lorance-v-att-technologies-inc-reply-brief-for-petitioners. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

*w

■

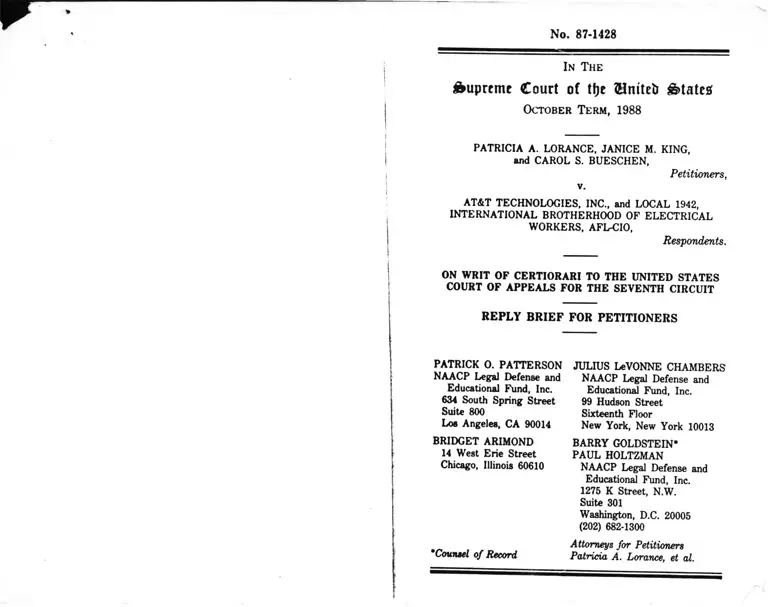

No. 87-1428

In The

Supreme Court of ttje ® m t e & States;

October Term, 1988

PATRICIA A. LORANCE, JANICE M. KING,

and CAROL S. BUESCHEN,

Petitioners,

v.

AT&T TECHNOLOGIES, INC., and LOCAL 1942,

INTERNATIONAL BROTHERHOOD OF ELECTRICAL

WORKERS, AFL-CIO,

Respondents.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SEVENTH CIRCUIT

REPLY BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

PATRICK 0 . PATTERSON

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

634 South Spring Street

Suite 800

Los Angeles, CA 90014

BRIDGET ARIMOND

14 West Erie Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

JULIUS LeVONNE CHAMBERS

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

Sixteenth Floor

New York, New York 10013

BARRY GOLDSTEIN*

PAUL HOLTZMAN

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

1275 K Street, N.W.

Suite 301

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

Attorneys for Petitioners

Counsel of Record Patricia A. Lorance, et al.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Table of Authorities........... iiA

ARGUMENT 1

I- C o n t r a r y to R e s D o n d e n t s '

Mischaracterization of

Petitioners' Argument,

Petitioners Contend that

the Current Operation of

the "Tester" Seniority

System Is Unlawful . . . . 2

II. Respondents' Reliance

Upon Inappropriate and

Inaccurate Factual Arguments

Underscores the Error in

their Position that the

Petitioners Filed Untimely

Discrimination Charges . . 6

III. Respondents Ask the Court

to Adopt an Extreme Posi

tion That Was Rejected by

both Courts Below and that

No Court Has Adopted . . . 21

IV- International Association

of Machinists v, NLRB Does

Not Support Respondents'

P o s i t i o n ................. 25

i

Page

V. The Court's Prior Decisions

Provide that a Seniority

System Designed to Discrimi

nate May Be Challenged by

an Intended Victim when She

Is Harmed by the Operation

of the System............ 35

CONCLUSION.................... 44

Appendix A.

Exhibit 11 to the Deposition

of Petitioner Bueschen,

R.6 8A, exhibit 11.

Appendix B.

Correspondence Regarding

the Use by Respondents

In their Brief of

Cutside-the-Record Facts

and a Privatedly Com

missioned Research

Project ..................

ii

TABLE of authortttc-o

Cases Page

A1?ooaMle Paper Co- v - Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975) 35

A1?“ v - Gardner-Denver Co.,415 U.S. 36 (1974) 23, 34

American Tobacco Co. v. Patterson 456 U.S. 63 (1982) ' 39-41

Bau"?e' V ' Frlday- 476 °-s - 385 36, 38

44

Bishop v. Wood, 426 U.S. 341 (1976) . . 1

California Brewers Ass'n v.

Bryant, 444 U.S. 598 (1980)

renick, 443 U.S. 449 ( 1 9 7 9 9

Dayton Board of Education v

Brinkman, 443 U.S. 526 (1 9 7 9). . 9

Delaware State College v. 449 U.S. 250 (1980) Ricks.

DelCostello v. Teamsters, 1 462 U.S. 151 (1983)/ * * 0 •

v. Home Insurance Co., 553

. Supp. 704 (S.D.N.Y. 1982)

43-44

29-30

6

iii

EEOC v. Westinghouse Electric

Corp., 725 F .2d 211 (3d Cir.

1983), cert. denied, 469 U.S. ^

820 (1984) ....................

Ford Motor Co. v. EEOC, 458 U.S. ^

219 (1982) ....................

Heiar v. Crawford Country, 746

F .2d 1190 (7th Cir. 1984),

cert. denied, 472 U.S. 1027 22-23

(1985) .......................

International Association of

Machinists v. NLRB, 362 U. • 25-29

411 (1960) ..................

Johnson v. General Electric,

840 F .2d 132 (1st Cir. 1988) . •

Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55

(1980) ........................

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises,

390 U.S. 400 (1968) ..........

NLRB v. International Brotherhood

Of Electrical Workers, 827 F.2d

530 (9 th Cir. 1987) ..........

Owens v. Okure, 57 U.S.L.W. 4065

(Jan. 10, 1989) ..............

Personnel Administrator of

Mass. v. Feeney, 442 U.S.

256 (1979) ....................

Potlatch Forests, Inc., 87 NLRB 2 7 _ 29

1193 (1949) ..................

Cases (Continued)

iv

Causes (Continued) Page

Reed v. United Transportation Union, 57 U.S.L.W. 4088 (Can. li, 1989) . . . .

Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977)

Un“ 'dI1Aer Llnes’ Inc- V. Evans. 431 U.S. 553 (1977)

United Parcel Service v

Mitchell, 451 U.S. 56’(1981)

United States v. Bd. of Schools

Commissioners, 573 F.2d 400 (7th Cir.), cert. denied.439 U.S. 824 (1978)

Village of Arlington Heights v.

Metropolitan Housing Development Corp., 429 U.S. 252 (1977)

W?i976?t0n V' DaVis' 426 U -s- 229

Statutes

Labor-Management Reporting and

Disclosure Act, §1 0 1 (a)(2 ), 29 U.S.C. § 411(a)(2)

Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

§§ 2 0 0 0e et seq.

23, 30-

32

9, 16,

35

37-38,

43-44

29-30

42

9, 37

9

30-32

passim

v

Statuses (continued)

Equal Employment Opportunity Act

of 1972, P.L- 92-261, _ _ 33

86 Stat. 103 ..............

National Labor . . . passim§ 10(b ) , 29 U.S.C. § 160(b)

T^qislative__AjathprjLt-ies

118 Cong. Rec. 7167 (1972) • • * ’ 33

nthpr Authorities

r u Northrup, Economics G. Bloom & H. Norxmup, . _ 16oX^abqr_Relatl°ns 237 (1961).

tt Harbison, The__Seniority

F -̂ n ciole inJ J n i o n z m ^ e m ^ - ̂ 16

Bplations 33 (1939) ........

lackson and Matheson, Th§

Cpntin^ng^^Aali°^l^||^ tionand the_Cqnce£t_qf_^^A^i£----

ITT Title VII Suits, 67 Geo. R

-------Z------ / 1 Q 7 Q \ ...........................................L.j. 811 (1979) .............. 6

r . Stern, E. Gressman, S . Shapiro, Supreme__CquTt_Pra£tice (Sixth

ed. 1936) at 564 ..............

Union Contract Clauses (CCH)

<(| 51,428 ................. 17

No. 87-1428

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1988

PATRICIA A. LORANCE, JANICE M. KING,

and CAROL S. BUESCHEN,

Petitioners,

v .

AT&T TECHNOLOGIES, INC., and LOCAL 1942

INTERNATIONAL BROTHERHOOD OF ELECTRICAL

WORKERS, AFL-CIO,

Respondents.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SEVENTH CIRCUIT

REPLY BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

ARGUMENT

Petitioners submit this brief in

reply to respondents' brief. With respect

to most of respondents' arguments, we rest

on our principal brief and on the brief

for the United States and the Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission as

2

amici curiae. Our reply brief addresses

only the following five points.

I. C O N T R A R Y TO R E S P O N D E N T S '

MISCHARACTERIZATION OF PETITIONERS'

ARGUMENT, PETITIONERS CONTEND THAT

THE CURRENT OPERATION OF THE

"TESTER" SENIORITY SYSTEM IS

UNLAWFUL.

The Company and Union consistently

mischaracterize the arguments of the

female workers. Repeatedly, respondents

assert that the "sole" basis for

petitioners' claims is that the seniority

"system was illegally 'adopted' because

AT&T and the Union allegedly acted with a

discriminatory motive" when they changed

the plant seniority system to the "tester

concept." Resp. Br. at 12; see also, Ad.

at 2, 6 , 10, and 17.

To the contrary, petitioners rely

upon the operation and effect of the

discriminatory seniority system. The

petitioners alleged in their Complaint

that AT&T aad the IBEW conspired to change

3

the seniority system » m order to protect

incumbent maie testers and to discourage

" " " , r °'" p r o m o t i n g into the

traditionaily-male tester jobs," and that

" [ t ] he larjose and effect of this

manipulation of seniority rules" were to

advantage male employees over female

employees. Joint App. 2 0 - 22 IEmphasls

added).

in accordance with these allegations,

the petiti o n e r s have argued that

"Whenever the seniority system operated

as intended by AT&T and Local 1942 to deny

J°b opportunities to petitioners because

of their gender, AT&T and Local i942.

commit an unlawful employment practice.

Brief at 2 1 . (Emphasis added| . when the

company and Onion Implement the conspiracy

to discriminate against women, they

violate Title VII -t-uSince the petitioners

filed charges of discrimination within the

4

requisite filing P « i - . Brie£ ** '3'16'

from tha date that the Company and Union

implemented the discriminatory seniori y

4- • i nners to lower-paying system to bump petitioner

jobs while males with less seniority

remained in the higher-paying Job*. the

v._ve filed timely charges, petitioners have r u e

case is whether the The issue in this case

nrt on a motion for summary district court, on

• mnrotjerly dismissed this action -judgment, improperly

i i-tiffs' EEOCon the ground that the plaintif

1 When petitioner Lorance^ " ob

downgraded on ! '^de tester 37.

grade tester prade 36 testers

there were ity than Lorance.with less plant J f ^ 0^ agY downgraded on

When petitioner*%rom a job grade 37

August 23, 1 ' ade tester 36, theretester to a 30 9 testers with lesswere t h i r t y B«de « aJe« ing . When

plant senior was downgraded onpetitioner Bueschenf was ^ 35

November 15, 1 ' 33 position theretester to a job S™.Se * de 36 testers

JTith ̂ ^ f e f ^ - h ^ u e s c h e n ^

B « , c he». attached as

Appendix A).

5

charges were not timely. In this

procedural posture, the Court must accept

the petitioners' "version of the facts,"

i n cluding the allegations in the

complaint . 2 Bishop v. Wood, 426 U.S.

341, 347 (1976). Accordingly,

respondents' repeated references to a

"neutral," " nondiscriminatory" seniority

system, Brief at 14-17, "adopted ... for

good reasons," and protected from

liability by § 703(h), id. at 16, see

also, id at 31-39, are not pertinent to

the issue before the Court. 3

̂ The petitioners never took

discovery in this case because "the Court

accepted the parties' recommendation that

discovery should be held in abeyance

pending resolution of the Company's ...

Motion for Summary Judgment." Joint

Status Report (Feb. 7, 1986), R. 46.

3 Respondents concede that no

legitimate reliance interests are acquired

under a seniority system that explicitly

provides less seniority for the work of

women that it provides for that of men.

Resp. Br. at 31 n.33. Yet they cite no

authority for their contention that the

6

TT R E S P O N D E N T S ' r e l i a n c e u p o n

11 • Inappropriate and inaccurate factual

ARGUMENTS UNDERSCORES THE ™ O R Ijj

THEIR POSITION THAT THE PETITIONERSTl L eV U N T IM E l Y D I S C RIMI N A T I O N

CHARGES.

R e s p o n d e n t s r e p e a t e d l y and

inappropriately (in light of the Court's

review of a grant of summary judgment,

see, section I, supra) use disputed record

rule should be different

which suffers from the same th*tdiscriminate but chooses to achieve *Tv

aoal through the operation of a policy

Shlch is designed to disadvantage woeen

Without establishing expl1 cit gender classifications. Concern for the

"substantial reliance in .̂er®*tQf t̂ e employees and the lost investment of the

company in the "guid £ro guo fox- the

challenged agreement, ** ia su99 VII' override the statutory goal of Title VII.

Id at 36. This Court certainly must

«ject a position which would permit a

Timely challenge to an intentionally

discriminatory policy to be thwarte Y

the interests of the parties to the

unlawful agreement. S_e_e

Home Insurance Cc k , 553 F. S“PP‘ ' The(S.D.N.Y. 1982); Jackson and Matheson,

Continuing_Violation T h ^~~viTnnncept of Jurisdiction in Titl^JOI

Suits, 67 Geo. L.J. 811, 851 (1979).

7

facts in support of their arguments. 4 * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * A

brief review of the record shows that

respondents mischaracterized the evidence

and that, properly viewed, the record

4 In an effort to support their

position, respondents commissioned a

private research project from BNA Plus, a

custom research" division of The Bureau

of National Affairs, Inc. The project was

done pursuant to "specifications" set

forth by AT&T Technologies. The

respondents attached a summary of this

project as an Appendix to their Brief and

referred to the facts produced by thisproject. Brief at 14-15, n.15.

The Court "has consistently

condemned" the practice by counsel'of

a t t a c h i n g to a brief [as have

respondents] some additional or different

evidence that is not part of the certified

record." R. Stern, E. Gressman, S.

Shapiro, Supreme Court Practice (6th ed.

1986) at 564. " [A]ppellate courts have

dealt promptly and severely with such

infractions [by, for example] granting a

motion to strike the 'offending matter.'" Id. at 564-65.

-if loners requested respondents to

remove the references to the outside-the-

record private study; the respondents

refused. Appendix B. The petitioners

have lodged with the Clerk of the Court

the underlying data for the project which

the respondents produced with Mr.

Carpenter's letter dated March 3 , 1989.

8

underscores the error in respondents'

arguments.

1. Respondents state that the

petiti o n e r s ' claim that the 1979

changeover from plant to tester seniority

"rests on statements that a few male

employees allegedly made at the three

union meetings in 1979," that "no facts

are alleged" that the statements

"represented the views of the union

leadership," and that it is not "alleged

that AT&T knew what had been said at the

union meetings" or that anyone from AT&T

negotiated the new seniority system for

other than "legitimate business reasons."

Resp. Br. at 6-7; see also, Brief at 14-

15 (emphasis added).

First, the harsh impact of the

new dual seniority system on female

workers provides objective circumstantial

9

evidence of discriminatory intent. 5 By

depriving women of the use of seniority

accumulated in the "traditionally" female

j o b s w h e n t h e y m o v e d to the

"traditionally" male tester jobs, the 1979

seniority system has an obvious adverse

impact on the job opportunities of female

workers. See, n.l, supra, and R6 8B at 59,

147 and 187. * 24

"Determining whether invidious discriminatory purpose was a motivating

factor demands a sensitive inquiry into

such circumstantial and direct evidence of

intent as may be available." Village of

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing

Development Corp. , 429 U.S. 252, 266

(1977); see also, Personnel Administrator

QL-ffass. y. Feeney. 442 U.S. 256, 279 n.

24 (1979). Such objective evidence

includes the fact "that the law [or

practice] bears more heavily on one race

than another." Washington v. Davis. 426

U.S. 229, 242 (1976). In addition,

"actions [undertaken which have]

foreseeable and anticipated disparate

impact are relevant evidence to prove the

ultimate fact, forbidden purpose."

Columbus Board of Educatlon v. Penlck, 443

U.S. 449, 464 (1979); see also Dayton

Board of Education v. Brinkman, 443 U.S.

526, 536 n.9 (1979); Teamsters v. United

States, 431 U.S. 324, 339 n.20 (1977).

10

Second, union officials admitted

that the purpose of the seniority

changeover was to "protect" those male

workers who were working in the tester

positions when female workers began to

move into those jobs in the 1970's. Mr.

Holly, a union official, R6 8C at 61, told

petitioner King that the Tester Concept

was instituted "to protect people ... who

were already testers." R6 8C at 207-08;

see, R 6 8 C at 71-74. Another union

official, Craig Payne, told petitioner

Lorance that she "was not really wanted m

testing." R6 8B at 42 (Craig Payne was a

Vice President of the Union, R6 8B at 8 6 ) . 6

6 C o m p a n y o f f i c i a l s a n d

suDervisors knew that the incer£ ^ e change the seniority system came from the

^ r t i ’o n s " ^ 1 ^ h e 1 malPer V e ^ e V V nd ’ °t orelieve the "tension" in the plant caused

by the male workers' hostility t° Vj advancement of the female workers R6 8C

at 48-54. In addition, a union official,

Steve Lorenz, told petitioner Lorance th

a member of "upper management, Skelton,

11

Third, the conduct of the 1979

Union meetings d e m o n s t r a t e s the

discriminatory purpose of the seniority

change. The first meeting described in

the record was attended by approximately

twelve men, including the treasurer

(Batterson) and vice president (Payne) of

the Union, and two women (Lorance and

Jones). R6 8B at 84-89. "The men ... were

upset because women were coming in with

seniority and . . . bypassing them for the

upgrades.... They wanted something done 30

the manager of manufacturing, R6 8 C at

exhibit 15d, called the female workers

"Suzys;" that "Suzys belonged out making

the data sets ... didn't belong in testing

and that Suzys were coming in and hurting

the men." R6 8B at 114-16; see also 6 8A at 44-45.

Furthermore, management's hostility

to women moving into the tester positions

was illustrated by the fact that women

were not afforded the same opportunity to

work on new jobs as men, R6 8B at 28 and

30, and R6 8C at 43, and that men received

more assistance and training from

supervisors than women, R6 8B at 28, 35,and 80.

12

about It." R6 8B at 84. "Most" of the men

present "were complaining about women

coming in." R6 8B at 87.7

The Union responded to the

complaints from the men by creating the

Tester Concept. The Tester Concept was

ratified at the June 28 , 1979 union

meeting. Pet. Brief at 9-10. It was "a

very heated" meeting with the men sitting

on one side of the room and the women on

the other side . 8 R6 8 C at 101. Union

members complained, once again, "that

women were coming in with seniority

7 Petitioner Lorance only learned

about this meeting because she overheard

some testers talking about the meeting.

R6 8A at 173. Apparently, the men were

holding several secret meetings to which

no women union members were Invited. R6 8B

at 89; see also, R6 8A at 31-32. These

"secret" meetings would be a focus of the

plaintiffs' discovery if they are able to

pursue their claims.

8 The record Is unclear as to how

well and fairly the meeting was published.

See, R6 8C at 87-88.

13

passing the men up and they were tired of

it." R6 8B at 103.9

Fourth, the hostility of the

male testers to the entry of women into

tester positions extended from the union

meetings to the shop floor. For example,

during the period in 1 9 7 9 when the

seniority change was under consideration,

offensive posters were repeatedly placed

"all over" the workplace. R6 8B at 110; 10

R6 8A at 28-30; R6 8 C at 23-25. Company

supervisors and union officials knew

Petitioner Lorance recalled a single woman, whose husband worked as a

tester, speaking in favor of the seniority

change. She said "she was in favor of

[the seniority change] because of her

husband [and because the women testers

were] taking bread off their table." R6 8B at 104.

In one particularly offensive

posters women were shown "standing

with dresses, like, at their knees, socks

like nylons, okay, with money hanging out

of them." The posters had the caption

"I'm a tester now. I make lots of money.

I have lots of seniority." R6 8B at 109.

14

about the posters. R6 8C at 24-27; R6 8B at

110-14 .

2. Respondents assert that "[t]he

agreement is a classic accommodation of

employer and employee interests," Resp.

Br. at 15; that it is "narrowly

tai l o r e d , " i d . at 6 ; that it is

"rational," id. at 36; and that it is a

"departmental system" like many other

systems, i_d\ at 14-15. Respondents may

attempt to establish th.ese points if

there is a trial on the merits. However,

these arguments are irrelevant to this

issue presented on summary judgment and,

in any event, the present record does not

support respondents' conclusions.

For example, respondents have

not established that the division of the

hourly paid jobs into two seniority units

qualifies as a standard departmental

s e n i o r i t y system rather than, as

15

petitioners maintain, an arbitrary

division designed to advantage male

workers over female workers.^

Furthermore, r e s p o n d e n t s

maintain that the Tester Concept

"addressed traditional employer concerns"

by creating "separate seniority lists for

skilled and unskilled workers." Resp.

Br. at 4 . Respondents rely on several

authorities for the proposition that

employers generally prefer small,

departmental seniority systems separating

skilled and unskilled workers. Resp. Br.

at 15, n.16. However, respondents fail to

acknowledge that these same authorities

also conclude that unions usually prefer

seniority districts "broad enough in scope

to include all employees for whom they are *

Respondents' desperate, improper

and incompetent attempt to rely upon

outside-the-record facts must be rejected.

See, n .4, supra, and Appendix B.

16

the bargaining representatives." Union

entrant Clauses (CCH) 1 51.428 (1954)12

(Emphasis added).

The Union, not the Company,

proposed the Tester Concept. R68B at 104-

OS. Accordingly, when the Union proposed

this seniority change, which split its

bargaining unit, it advocated a position

contrary to the standard and expected

union position. This departure by the

Onion from the general preference of

unions to avoid divisiveness among the

members of a bargaining unit supports the

allegation that this particular decision

was motivated by a discriminatory purpose.

See, Teamsters_v^_United— States , 431 U.S.

at 356.

3 . R e s p o n d e n t s b a s e their

12 S ee a l s o , G. Bloom & »•

Northrup, Ecpnprru^of_^b , ,q q i \. f Harbison, Tne— a. e “ -i ̂ l-M^nl'e in Uni on-Manaqement_Relatipns 33

(1939) .

17

arguments upon the assumption that it was

clear when the agreement incorporating the

Tester Concept was signed in 1979, Joint

App. 50-56, that tester rather than plant

seniority would govern job downgrades.

Resp. Br. at 5, 7. However, as

demonstrated by the Union's own position

statement made in January 1983, it was

not clear whether tester or plant

seniority applied to downgrades until

§ f.t?_r the petitioners were demoted.

Appendix A.

After the petitioners were

downgraded in 1982 they requested that the

Union file a grievance on their behalf.

When Local 1942 filed a grievance beyond

the ten-day period established by the

contract,^ the petitioners complained to

The Company rejected the

grievances filed on behalf of King,

B u e s c h e n and Lorance because the

grievances were filed more than 10 days

after the job downgrade. R68A at exhibit

18

the International. In an explanation of

its actions to the International, Local

1942 stated that there is a disagreement

about the interpretation of the Tester

Concept between the Union and the Company.

The Union's contention

is that there were

three (3) provisions

provided for employees

on roll entering the

testing universe. All

of these were for the

upward movement.

* * * * *

The Company's position

is that they intend to

a p p l y t h e s a m e

p r o c e d u r e on the

downward trend.

Id. (Emphasis added). Consistent with

the Union's contention in 1983, petitioner

King had been told by Union officials that 10

10. The petitioners maintain that the

Union discriminatorily failed to file a

timely grievance because the Union "had

plenty of notice [to file on time

including] a written request from

[Lorance] to file a grievance for [the

three petitioners]." R68B at 176; see,

R68A at 188-89.

19

tester seniority "would ho .y would be used for

upgrades onl y and that plant seniority

would be used for downgrades. R68C at 119

and 123.

M o r e o v e r , the 1983 Union

document Indicates that this issue and,

implicitly, the Union's contention that

tester seniority applied only to upgrades,

"had been discussed at the Union meetings

and the sister had been advised that the

union was in the process of negotiating

the Tester Training Program" and that the

union is "in a negotiation stage and

attempting to resolve these problems with

the company...." Appendix*. Consistent

“1th this 1983 statement that the Union

was still negotiating with the Company,

Petitioner Bueschen was told in 1981 by

the president of the Union that the Union

“as still negotiating about the Tester

Concept. R68A at 78-79.14

Seniority systems and collective

bargaining agreements often are ambiguous

a n d s u b j e c t to c o n f l i c t i n g

interpretations. The meaning of such

agreements is hammered out during their

implementation by employers and by the

resolution of the disputes that arise from

that implementation. To compel workers,

as the respondents' position requires, to

file charges of discrimination before such

agreements are implemented would require

the filing of unnecessary litigation about

the hypothetical application of unclear

collective bargaining agreements and

employment practices. Pet. Br. at 48-

55; United States Amici Curiae Br. at 23-

24 .

The Tester Concept was never

approved by the International and never

included in the master contract between

the Union and the Company. R68C at 214-15; R68B at 122-24.

21

This case is a good example.

Prom 1979 through 1962 it was unclear

whether the new seniority system applied

to downgrades. The Onion maintained that

it did not, and the Company maintained

that it did. If the petitioners filed a

charge before they were harmed by a

downgrade, the district court would have

^ e n p l a c e d in the p o s i t i o n of

interpreting the agreement prior to its

application by the parties - assuming

that the court would rule that the issue

was ripe for decision.

III. RESPONDENTS ASK THE COURT TO ADOPT AM

“ ™ EKcoim°4ITnI0N THAT MAS S jS S S By

has adopted AND THAT "° C0TOT

AT&T and Local 1942 argue that

employees may not make a Title VII

challenge to an ongoing seniority system

"unless that challenge is brought within

180 days of the date of adoption." ReSp.

at 17 28. This extreme position has

22

not been adopted by any court and was

explicitly rejected by both courts below.

As the district court recognized, the

rule advocated by respondents would

"encourage! ] people to bring unripe

claims alleging harms that they may never

experience," and would "only clog the

already overburdened courts with lawsuits

that are not ripe." Pet, App. 29a-30a.1 *®

Such a rule would guarantee needless

c o n f r o n t a t i o n r a t h e r than the

" [ c ] ooperation and voluntary compliance"

sought by Congress "as the preferred

1 ° See also Johnson v. General

Electric, 840 F.2d 132, 136 (1st Cir.

1988) ("It is unwise to encourage lawsuits

before the injuries resulting from the

violations are delineated, or before it is

even certain that injuries will occur at

all") ; NLRB v. International Bhd, of

Elec, Workers, 827 F.2d 530, 534 (9th Cir.

1987); Heiar v, Crawford Ctv. 746 F.2d

1190, 1194 (7th Cir. 1984), cert, denied,

472 U.S. 1027 (1985); EEOC v .

Westinghouse, 725 F.2d 211, 219 (3d Cir.

1983), cert, denied, 469 U.S. 820 (1984).

23

means for achieving [Title VII's] goaJ

415 u.s.

(1974). see also Reed v. Uni .j

57 u.SiL w 4Q88<

4090 (Jan. 1 1 , 1989).16

court of appeals rejected

respondents' proposed rule for the same

reasons: "Reguiring employees to contest

any seniority system that might some day

apply to them would encourage needless

litigation," and "would frustrate the

remedial policies that are the foundation

° f Title VII." pp*. .Pet. App. 8a. Under

respondents' approach, the Seventh Circuit

neted, "any seniority system would be

aaek an inform's? relo'lution*\ deS 1 re to

to comply with the pil“ ?"s' remf3" ” ”' (as did petitlonpw r y requirements

stymied by a for Lorance) would be

courthouse at the outlet m ® rch to theY, Crawford Ctv y h ^ Heiar

( " ^ o T T e - T o ' - i t ^ a n t to f .at 119*employment by suino thoi ° ,begin their

policy that will affect fhmPl°yer °Ver a" if at all.) f ct them years later,

24

immune to challenge [180 or] 300 days

after its adoption," and ” [f]uture

employees would therefore have no recourse

when confronted with an existing seniority

s y s t e m that they believe to be

discriminatory." Id.

The harshness of respondents'

position is chilling. This position would

l a r g e l y I n s u l a t e i n t e n t i o n a l l y

discriminatory employment practices from

challenge 180 (or 300) days after their

adoption even with regard to persons not

employed by the company or represented by

the union at the time of the adoption of

the practice. Accordingly, an employment

test used for promotional decisions and

neutral on its face but instituted with an

intent to discriminate would be immune to

i' Respondents' position would

apply to all discrimination claims

brought under Title VII. Resp. Br. at 17

n. 21.

25

challenge by a worker hired one year after

the adoption of the test. Even though the

newly hired worker was harmed by the test

one week after her employment and even

though she filed a charge the following

day, the respondents' position would

require the rejection of the charge as

untimely filed.

Not surprisingly, no court has ever

embraced the extreme view of Title VII's

f i l i n g r e q u i r e m e n t espoused by

respondents.

IV' I-N T E_R_N A T I 0 K AL A S S O O T A t t o m

_ -̂i__NLRB DOEls N0T~^SUPPORTRESPONDENTS' POSITION.

R e s p o n d e n t s rely heavily on

~-t-gZI1̂ ĵ ^ - ^ g ° g l a t-ion of Machinic^ „

NLRB, 3 6 2 u.s. 4 1 1 ( 1 9 6 0 , ( -Bryan

ManuXactutung'.,, construing the six-month

statute of limitations under § 10(b) of

the National Labor Relations Act, 29

U.s.c. § 1 6 0(b). See, Resp. Br. at 18-

26

23. There are two reasons that Bryan

M a n u f a c t u r i n g does not support

respondents1 position: even if the NLRA

limitations doctrine applied to Title VII,

it does not bar the petitioners- claims;

in any event, the NLRA limitations

doctrine does not apply.

1 . For the reasons set forth in our

principal brief, Bryan^anuf_acturins would

not bar plaintiffs' claims even if that

decision applied in the Title VII context.

In general, petitioners have maintained

that Bryan Manufacturing precludes

untimely challenges to flaws in the

establishment of otherwise lawful labor

policies but does not preclude an action,

such as Lorance, alleging that the

challenged policy is itself illegal. Pet.

Br. at 64-67.

P e t i t i o n e r s ' p o s i t i o n i s

supported by the r e l ia n c e o f the Court in

27

3ryan__Kanufacturinq on the decision of the

National Labor Relations Board in Potlatch

Forests_,__Inc^, 87 NLR3 1193 (1949), as an

example of the correct interpretation of

§ 10(b) of the NLRA. 362 U.S. at 419. In

—?.tlatch the Board held that, by "apDlying

and giving effect to a [discriminatory]

seniority policy" during the limitations

period of §10(b), an employer violated the

NLRA regardless of the date on which the

policy was adopted. 87 NLRB at 1211. 18

Like AT&T and Local 1942 in the present

case, the respondents in Potlatch adopted

illegal policy which did not cause

The challenge in Potlatch was to

a "Return-to-Work Policy" providing "that,

in the event of a lay-off resulting from a

curtailment of operations, employees who

returned to work ... during the course of

the 1947 strike were to possess

preferential retention rights over

[strikers]." 87 NLRB at 1208. As do

respondents, the employer argued that "the

validity of the . . . policy is no longer

open to attack, because it was established

some 16 months before the filing of the

charge." X4- at 1210-11.

28

employees an Injury in the form of layoffs

until a reduction in force was required.

However, with each layoff under the

u n l a w f u l p o l i c y the c o m p a n y

"discriminated" against employees who had

engaged in protected union activity and

thereby committed a fresh violation of the

NLRA. 87 NLRB at 1211.19

19 In rejecting the employer's

statute of limitations defense the Board

emphasized that "[t]he issue in this case

is not whether the Respondent committed an

unfair labor practice by inaugurating the

policy, but whether it violated the law by

c o n t i n u i n g to m a i n t a i n it; more

specifically by applying and giving effect

to it in ___ lay-offs [which] occurred

well within the statutory period limited

by Section 10(b)." Id. at 1211 (emphasis

added).

Because an Independent violation

occurred with each application of the

unlawful policy, the Bryan Manufacturing

Court cited Potlatch as a case where

evidence of the discriminatory motive at

work in the initiation of the policy was

properly "used to illuminate current

conduct claimed in itself to be an unfair

labor practice." 362 U.S. at 419-20. The

fact that, as the Board goes on to say,

that "[e]ven without such consideration

. . . the allegations ... would have been

29

2. Moreover, recent decisions of

this Court strongly suggest that the

restrictive limitations doctrine of Bryan

Manufacturing is properly confined to the

narrow area within the NLRA governing

individual challenges to allegedly unfair

labor pra c t i c e s in b a rgained- for

agreements.

In DelCostello v. Teamsters, 462

U.S. 151 (1983), the Court described the §

10(b) limitations period as specifically

"attuned to ... the proper balance between

the national interests in stable

bargaining relationships and finality of

found amply supported by" proof of facts

within the limitations period, 87 NLRB at

1211, does not alter this principle. That

the challenged policy in Potlatch employed

an overt distinction between strikers and

non-strikers does not vitiate the

principle of the case — for which it is

cited in 3ryan Manufacturing — that the

current conduct constituted by the

application of a policy "claimed in

itself to be" unlawful, 362 U.S. at 420,

is actionable regardless of the date of

its original adoption.

30

private settlements, and an employee's

interest in setting aside what he views as

an unjust settlement under the collective

bargaining system." Id. at 171 (quoting

u n it e ̂ P a r r al service v . Mlthcell» 451

U.S. 56, 70-71 (1981) (Stewart, J.,

concurring)). In refusing to apply §

10(b) to a claimed violation of an

employee's free speech as to union

matters, this Court in Feed v. United

Transportation Union, 57 U.S.L.W. at 4092

concluded both that the federal interest

in repose in collectively bargained

agreements is not central to the goal of §

101(a)(2) of the Labor-Management

Reporting and Disclosure Act (LMRDA), 29

U . S . C . § 4 1 1 ( a ) ( 2 ). and that a

countervailing federal interest in the

protection of free speech informs the

LMRDA.

in particular, the Court relied upon

31

the fundamental individual interests in

free speech modeled on the Bill of Rights

and protected by the LMRDA. 57 U.S.L.W.

at 4090. This different balance of

interests, the Court held, precluded the

application of the narrow § 10(b)

limitation period.

Title VII also does not share the

overriding legislative interest in the

stability of collective bargaining

agreements that led to § 10(b) and to its

restrictive statute of limitations

doctrine for some claims under the NLRA.

Although resolution of disputes is one

objective of Title VII, this statute,

like the LMRDA, "implements a federal

policy . .. that simply had no part in the

design of a statute of limitations for

unfair labor practice charges," Reed, 57

U.S.L.W. at 4092, and that weighs heavily

against the application of a restrictive

32

limitations period.

The Court in Reed emphasized the need

for the limitations period to "accommodate

the practical difficulties faced by

§ 101(a)(2) plaintiffs, which include

identifying the injury, deciding in the

first place to bring suit against and

thereby antagonize union leadership, and

finding an attorney." 57 U.S.L.W. at

4090. See also, Owens v. Okure, 57

U.S.L.W. 4065 (Jan. 10, 1989). Identical

obstacles face Title VII plaintiffs. See,

Pet. Br. at 48-55. Aware of these

obstacles in amending Title VII in 1972,

Congress explicitly approved decisions

having "an inclination to interpret [the

§ 706(e)] time limitation so as to give

•the aggrieved person the maximum benefit

of the law." Section-by-section analysis

of Equal Employment Opportunity Act of

1972, P.L. 92-261, 118 Cong. Rec. 7167

33

(March 6, 1972).20

R e s p o n d e n t s rely on the

legislative history of the 1972 amendments

to Title VII to support the position that

section 706(e) should be interpreted in

light of the § 10(b) limitations period of

the NLRA. Brief at 18 n.22. But that

history indicates that Congress merely

adopted a limitations period "similar" to

that in the labor statute. It in no way

supports the contention that Congress

meant to incorporate its restrictive

limitations doctrine. In fact, it is

clear from the same legislative history

that Congress intended to endorse the

doctrine of continuing violations and

decisions interpreting the statute of

limitations as running "from the last

occurrence of the discrimination and not

from the first occurrence ... and other

interpretations of the courts maximizing

the coverage of the law." Section-by-

section analysis, 118 Cong. Rec. 7167 (March 6, 1972) .

In addition, respondents support

their contention by referring to Ford

Motor Co. v. EEOC. 458 U.S. 219, 226 n.8

(1982), which cites only the patterning of

Title VII's remedial provision, Section

706(g), on the analogous section of the

NLRA. Even in that context, Ford Motor

Co • cautions that "[t ]he principles

developed under the NLRA generally guide,

but do not bind, courts in tailoring

remedies under Title VII." Id.

There is no support for the

proposition that Congress intended to

incorporate in Title VII the restrictive

34

The policy underlying Title VII, of

course, seeks the elimination of

employment discrimination. "Congress

indicated that it considered the policy

against discrimination to be of the

'highest priority.'" Alexander v.

Gardner-Denver Company, 415 U.S. 36, 47

(1974), quoting Newman v. Piqgie Park

Enterprises , 390 U.S. 400, 402 (1968).

The right to be free of employment

discrimination is this Act's equivalent of

the free speech protection of the LMRDA.

Congress specifically Intended to achieve

this important national goal through Title

VII actions brought by private litigants

acting as "private attorneys general."* 21

limitations doctrine of the NLRA.

21 Title VII charges and lawsuits

"provid[e] the 'spur or catalyst which

causes employers and unions to self

examine and to s e 1f-eva1uate their

employment practices and to endeavor to

eliminate, so far as possible, the last

vestiges' of their discriminatory

35

In view of the strong federal interest in

eradicating employment discrimination

through private actions, the balance of

interests underlying § i0(b) of the NLRA

as interpreted in Bryan__Mamifacturing

simply does not apply in the context of

Title VII.

I H L C0URT>S PRI0R DECISIONS provide t ha t a seniority system designed to

DISCRIMINATE MAY BE TIMELY CHALLENGED

BY AN INTENDED VICTIM WHEN SHE IS

HARMED BY THE OPERATION OF THE SYSTEM.

Respondents contend that prior Title

VII decisions of this Court either are

"[irrelevant, " Resp. Br. at 25, or

s u p p o r t r e s p o n d e n t s ' e x t r e m e

interpretation of §706(e). Id. at 23-25,

39-44. Petitioners submit that, to the

contrary, these decisions demonstrate that

an e m p l o y e e m a y c h a l l e n g e an

practices." Teamsters. 431 U.S. at 364

(quoting Albemarle_^aper Co. y. Moody. 422 U.S. 405, 417-18 (1975)).

36

intentionally discriminatory policy

whenever that policy is applied to her

detriment. See, Pet. Br. at 25-44.

In Bazemore v. Friday, 478 U.S. 385

(1986), the Court declared that each

application of a discriminatory pay

practice is "a wrong actionable under

Title VII, regardless of the fact that

this pattern was begun prior to the

effective date of Title VII." Id. at 395-

96. The violation in Bazemore was simply

that the current application of the pay

practice "perpetuated" the discriminatory

effects of a practice established before

Title VII became effective. Id- at 395.

The pay practice was currently applied in

a neutral manner and no intentional

d i s c r i m i n a t i o n , other than the

perpetuation of prior discrimination, was

established.

Similarly, the fact that the

37

intentionally discriminatory seniority

policy in this case was originally adopted

outside the limitations period cannot

protect it from challenge at the time it

is applied to the detriment of female

employees.22

Discussing a seniority system adopted

outside the statute of limitations, the

Court in United Air Lines, Inc, v. Evans,

431 U.S. 553 (1977), endorsed petitioners'

contention that Title VII "does not

foreclose attacks on the current operation

of seniority systems which are subject to

challenge as discriminatory." Id- at

560. Evans' particular claim was barred

because she did not allege any illegality

in the seniority system. As the Court

This conclusion is consistent

with general civil rights doctrine which

permits a challenge to an unconstitutional

policy whenever it is given effect. See

e .g ., Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55

(19 8 0) ; Village of Arlington Heights v.

Metropolitan Housing Corp., supra.

38

explained in Bazemore v. Friday, the

result in Evans would have been different

had plaintiff alleged that "the seniority

system itself was intentionally designed

to discriminate." Such a contention-

identical to that alleged by petitioners

here — would have properly asserted that

defendant was "engaged in discriminatory

practices at the time" the suit was

brought and would therefore have made out

a violation of Title VII. Accordingly, a

"present violation exists" by virtue of

the current operation of an intentionally

discriminatory system regardless of the

remoteness of its original adoption.

Bazemore, 478 U.S. at 396 n.6.

As described in petitioners' main

brief, numerous decisions of the Court

support the position that the statute of

l i m i t a t i o n s for challenges to an

intentionally discriminatory policy runs

39

from the date of its most recent

application to the detriment of a

protected class member. In American

Tobacco Co. v. Patterson, 4 5 6 U.S. 63

(1982), for example, the Court assumed

that a policy alleged to be the result of

intentional discrimination could be

challenged as long as it was in operation.

The Court rejected the EEOC's

advocacy of a distinction for purposes of

§ 703(h) coverage between seniority plans

adopted before and those systems adopted

after the effective date of Title VII. In

so concluding, the Court implicitly

approved challenges to the application of

discriminatory policies adopted outside

the 180-day limitations period. 456 U.S.

at 70. The Court noted that in Patterson

one Title VII challenge (alleging race

discrimination) was filed within the

statute of limitations period after the

40

policy's adoption and a second challenge

(alleging sex discrimination) was filed

beyond that period. 456 U.S. at 70, n. 4 .

The Court expressed no hesitation as to

the timeliness of the latter challenge by

employees to whom the challenged policy

had applied since its adoption and for a

period longer than the limitations

period.23

Patterson supports the conclusion

that a challenge to an intentionally

discriminatory seniority policy is timely

if filed within the statute of limitations

period running from the date of its most

recent application.

Respondents' contention that the

"fa c i a l l y neutral" nature of the

The Court also indicates that

"persons whose employment begins more

than 180 days after an employer adopts a

seniority system" may, contrary to the

extreme position of respondents, see,

Section III, supra. file a timely charge. 456 U.S. at 70.

41

challenged policy is somehow significant

is belied by the case law. The relevant

inquiry is whether "differences in

employment conditions" are "the result of

an intention to discriminate because of

race, color, religion, sex, or national

origin. " See e . q . California Brewers

Association v. Bryant, 444 U.S. 598, 611

(1980). The Court's Title VII cases do

not support the suggestion that a policy

deliberately designed to disadvantage

women is protected against subsequent

challenge if the mechanism chosen does not

involve overt distinctions based on

gender.

Where an employer and union apportion

seniority credits in a manner designed to

discriminate against female workers, the

fact that they implement the scheme

through the "neutral" operation of the

seniority system does not vitiate the

42

discrimination.24 The fact that the

companies and unions attempt to conceal

their intentionally discriminatory

conduct should not shield them from Title

VII liability.25 * 2

For example, it would not be

permissible for a union and employer to

decide that, because a particular division

was predominately female, seniority

credit for service in that division would

be awarded at a rate half that of the rest

of the plant. Such a policy, although

"facially neutral," clearly constitutes an

"unlawful employment practice" under

Section 703(a) of Title VII. Although

lacking an explicit gender distinction,

each operation of this intentionally

discriminatory seniority policy would be

actionable. See, United States Amici Curiae Br. at 16 n.19.

2 5 The respondents compare the

application of their proposed standard to

"facially lawful" with their standard's

application to "facially unlawful"

seniority systems. See e.q., Resp. Br. at

31. This comparison is meaningless; no

company or union is going to broadcast in

collective bargaining agreement its

invidious intent by instituting an overtly

discriminatory seniority system. See,

U n i t e d S t ates v. Bd. of School

Commlssloenrs, 573 F.2d 400, 412 (7th

Cir.), cert. denied. 439 U.S. 824 (1978)

("In adage when it is unfashionable for

state officials to openly express racial

43

Respondents' reliance on Delaware

State College v. Ricks ., 449 U.S. 250

(1980) , is also misplaced. Like the

plaintiff in Evans, the plaintiff in Ricks

challenged a discrete act of alleged

discrimination against him — in his case,

the decision of a college board of

trustees to deny him tenure. Also like

the plaintiff in Evans, the plaintiff in

Ricks failed to file his charge of

discrimination within the statutory period

after this discrete act occurred. He did

not allege or prove that he was harmed by

the c o n t i n u i n g o p e r a t i o n of any

discriminatory system or policy; rather

"the only alleged discrimination occurred

-- and the filing limitations periods

therefore commenced -- at the time the

tenure decision was made and communicated

hostility, direct evidence of overt

bigotry will be impossible to find.")

44

to Ricks." 449 U.S. at 258; see also, 449

U.S. at 258 n .9.

As demonstrated in our principal

brief, the Court in its prior Title VII

seniority cases has repeatedly recognized

the operation of an illegal seniority

system as an unlawful employment practice,

without regard to the date on which the

system was adopted or the date on which

the plaintiff initially became subject to

the system. Pet. Br. at 31-44. Nothing

in Evans, Ricks, Bazemore, or any other

decision of this Court supports a

departure from this well established

principle.

Conclusion

Petitioners respectfully request that

the Court reverse the judgment of the

45

Seventh Circuit.

Respectfully submitted,

JULIUS LeVONNE CHAMBERS

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

Sixteenth Floor

New York, New York 10013

BARRY GOLDSTEIN*

PAUL HOLTZMAN

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

1275 K Street, N.W.

Suite 301

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

PATRICK 0. PATTERSON

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

634 South Spring Street

Suite 800

• Los Angeles, CA 90014

BRIDGET ARIM0ND

14 West Erie Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

Attorneys for Petitioners

Patricia A. Lorance, et al.

♦Counsel of Record

^International Sroflirrliooi' of Llrririral li1orl;rrs

1741 JER ICHO ROAD

AURORA, IL 6050* LOCAL 1942 TELEPHONE 859-2833

January 12, I9g3

James P. Conway

Sixth District vice President

373 Schraale Rd., Suite 201

Carol Stream, Illinois 60187

Dear Sir and 5rother«

Se: Three letters of complali

into°negotlat°onsUwit^the In 1978 *«• ^ . 1 entered

it is the Montgomery Dorics ?e^2r ̂ r a i ^ - p * * t0 Whit ia refor~ d to< originally designedyto further t r a i n n | Program. This program was

well a. to provide a m.ani by whlcî t^e n o n P r e , 0 n t l y toll a,tain the necessary trainino to non-testers on roll could ob-

the contract, in fsSO T l , T t lll W M 'r"de part of1980 bargainina that tha * fi Zt * further agreed during

• copy enclosed?, ‘to^asT S T F iT I L Z S ? ' * 9 p T * boo?1*t

tlate"the ^ t e ^ T r ^ Tr^tlT^TTiTA -Til "*9°-

82 with J.E. McGovern Barcainiio'tJ.!* •, L ting K** held on 12-21

wherein we were unabli to agree on M b s ' 3 Company,Company was advised bv m* ^#4,5,6,47. At that time the

Of *11 t..?e» involved? ,s^r.?[.ch:SCT:erOUldebe ls*ued °n b"hal* uals involved). Attached letters for each of the Individ

nt.

SIXTH DISTRICT, I.B.LW.

Fraternally,

Q.o^fP^-e^

/ /James Cappleman

' President t Business Manager

I.B.E.W, Local 1942

I X H I B I T

Soescmi

J C / i a

Snc.

Sitter P.A. Lorance - EI809857

. i.ft.r dated 11-9-82 whereing the gave me

S & s x & t t s r s i i “

Ihi\r.t“rChi“ b«r:dvtt.̂ th.tithr5,ntontw^lnni^ ££»'<><

negotiating the Tetter Training Program.

The Union*, contention i. that [J";,;;" ^ e l j ^ M U f 0theSe were

for employeei on roil entering tn«

for the upward movement.

»• £ O T e T o nb r ! £ Montgcmeryi»ervicetforUthe*upward

movement.

2). Obtain the .am. amount of ...vie. a. other tetter, in the

universe.

Completion o, «h. <l». <« “ <“ «*“ '

Program.

Tho Comp.ny1. PO*lll“n *f*- lnioraitlo^^P-A* Lot.nc. ini

i;r:ois:.*.:!tr;s; “ s;.” . r ; S n „ . a.o • >■ •— *••»* °n

11/15/82 to a 37 grade teeter.

There are pre.ently tixty-.ev.n ,67, 38 grade te.t.r, with 1... Mont

gomery tervice.

Grievance, were n^^'tlking'the^.itio^thit these griev-

the present time the Company ** ** ^ w. were in a negotia

tion* s tage'^nd"'^ tempting to re.olv. thee, problem, with the Comp.ny,

that our time frame started 12-21-82.

Sitter J.K. King - E#805595

{}:•;“ ............meeting in Columbu., Ohio and w„ unlble to d! io! * 3 Council

the siste^ha^been^dviSe^tha^the'uni th* Union "••ting» and negotiating the Te.t.r TmniJjgSrogr^!0" "*• ln th* prOC*“

11 ■ s y s v ^ s r t s i a i a .

2>' TitS.I*' “ °Unt °f *ervlc* •• o^.r te.t.r. in the

3)' Progr«it̂ 0n °f “ • fiV* (S) modul" in th« T»«t.r Tr.inin,

a u r « r j i s . ” ■ ~ ™ ”

i::«,:r:iS,;:21s.:;js.,s “ SOL” ........ ■«» »......

s ^ i ^ t s s - s j a s * , n s s s . “ ~ ^ s s s j ^ s . .

Sister C.D. Bueschen Ei B092S6

Sister Bueschen sent me a letter dated 11-4-82 wherein she gave me

five (S) days to respond. Subsequently I was attending a EH3 Council

Meeting in Columbus, Ohio and was unable to do so.

This particular issue had been discussed at the Union meetings and

the sister had been advised that the Union was in the process of

negotiating the Tester Training Program.

The Union's contention is that there were three (3) provisions provided

for employees on roll entering the testing universe. All of these were

for the upward movement.

1) . Employees spend five (5) years in a tester universe before

being able to bridge Montgomery service for the upward move

ment.

2) . Obtain the same amount of service as other testers in the

universe.

3) . Completion of the five (5) modules in the Tester Training

Program.

The Company's position is that they intend to apply the same procedure

on the downward trend. The specific information on C.D. Bueschen is;

she has a 2-2-70 Montgomery service date. She entered the testing uni

verse from a 32 grade to a 35 grade on 11-30-80. She has passed one (1)

of the testing modules as to date. She was downgraded from a 35 grade

tester on 11-15-82 to a 33 grade utility operator.

There are presently one hundred four (104) 36 grace testers with less

Montgomery service: thirty-five (35) - 37 grade testers, seventy-nine

(79) - 3E grade testers, and one (1) - 39 grade testing layout operator.

Grievances were issued on her behalf, (copies attached), and still at

the present time the Company is taking the position that these griev

ances are untimely. We still contend since we were in a negotiation

stage and attempting to resolve these problems with the Company, that

our time frame started 12-21-82.

APPENDIX B - Correspondence Regarding the

Use by Respondents in their Brief of

Outside-the Record Facts and a Privately

Commissioned Research Project:

I1. Letter from Barry Goldstein, counsel

for petitioners, to Susan Korn,

senior labor analyst, BNA Plus,March 1, 1989.

2. Letter from Paul Wojcik, general

counsel of BNA, to Barry Goldstein, March 1, 1989.

3. Letter from Barry Goldstein to Rex

Lee and Stephen Feinberg, counsel for

respondents, March 2, 1989.

4. Letter from David Carpenter, counsel

for respondents, to Barry Goldstein, March 3, 1989.

5. Letter from Barry Goldstein to David

Carpenter, March 3, 1989.

6. Letter from David Carpenter to Barry

Goldstein, March 6, 1 9 8 9 .

Suite 301

1275 K Street. NW

Waakiuftou, DC 20005 (202)682-1300 Pm : (202) 682-1312

HAMD-DELIVER

March 1, 1989

TOF NAACP LOCAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL WJND, INC.

Ms. Susan Korn

BNA Plus, Room 215

1231 25th Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20037

Dear Ms. Korn:

As I told you yesterday by telephone, I Just learned that

the Appendix to the Respondents' Brief In Lorance v. AT&T

Technologies, No. 87-1428, entitled "Contracts with Departmental

Seniority,” was prepared by a section of the Bureau of National

Affairs called "BNA Plus." There was no reference In the brief,

which I have sent to BNA, to the source of the data other than BNA.

By telephone yesterday I requested a copy of the "report,"

If any, from which this chart was taken. You told me that this

was a "customized" Job. I requested all the Information about

the chart; for example, there is no indication as to how the so-

called "representative sample," see. Resp. Brief at 15 n.15, was

determined, how “departmental" was defined, or even the dates for

the contracts. You told me that it was contrary to BNA policy to

release the "specifications" for a "customized" Job or even the name of the client.

This BNA work-product, assuming that it has not been altered

in any way, can not be evaluated without BNA providing the

"specifications" for the Job, and the supporting Information

about the sample, the definitions used, etc. Of course, it is

important to evaluate not only the validity of BNA's work

product, but also whether BNA's work product has been properly

There is no reference in the Table of Authorities to

the BNA report. The only reference in the Brief to the source

for the report is "Appendix to this Brief," Resp. Brief at 15

n.15. The Appendix only refers to the "Statistics of Bureau of

National Affairs on Departmental Seniority Systems;" there is

also a copyright 1989 by The Bureau of National Affairs."

Ci i.J ii ■ mm

MMmUfmUS TW NAACP Legal !*<«■« * IA k m m m I feai. lac. (IDF) a met am

a f Ae Nasiamal Aaaoaaaa far Ac Aietmoanemt e f CetaraJ Psafic

(NAACP) alAaagfc LDf m m tmmUai by As NAACP ■

r* ....... LOP Was ka4 far v

•aasl peagTM suff. sff.ee md U4fCt.

Sam MM PtUNlmi

N r e V a iN Y M U(ra)m-mo P»« rmi m-nn

4N S. S fnaf Ssrece

Lee Aageiss. CA W N

(2U)«34-MB

Ns; rsni uejwn

Ms. Susan Korn

March 1, 1989

Page 2

Used by AT&T Technologies and the Union. Obviously, this

evaluation can not even be begun without the supporting

Information, methodology and definitions used to prepare this

chart.

The petitioners reply brief Is due on March 7. I need the

above information Immediately In order to determine whether and.

If so. In what matter a reply should be made to this BNA work-

product .

If a BNA “client" uses, as here, in a Supreme Court Brief a

customized product from BNA without revealing that It is such a

product or setting forth all of the Information necessary for an

evaluation of the BNA product, then BNA should reveal all of the

necessary information in order to assure that neither the Court

is misled nor opposing parties harmed.

I know that it is not BNA who has sought to Introduce facts

from outside of the Record Into the argument before the Supreme

Court. But since, as I have been told, BNA "prepared" these

facts, BNA has a responsibility for the use or misuse of its

product.

As a result of the time requirements for filing a reply

brief, I would appreciate an immediate response.

Very truly yours.

Barryv Goldstein

BG:oet

T H E B U R E A U O F N A T I O N A L A F F A I R S , I N C .

^ General CnwwH. OWeei n eM JtU M U S T W

and Ai&teuni Secretary

March 1 , 1989

Barry C o ld ste ln

NAACP Legal D efease sad

E ducation al Fund, I n c ,

S u ite 301

1275 t S t r e e t , N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

Dear Mr. G o ld ste in :

Tour l e t t e r to Susan Korn has been r e fe r r e d to me fo r a r a p ly .

The Bureau o f N ation a l A f f a i r s . I n c , d o e . not r .y . a l th e id e n t i t y o f i t .

s u b s c r ib e r s , th e p ro d u ct, th ey su b scr ib e t o , or th e nature o f any research

2rl».c°T U h , 5*1 Such lnform * t lo n U f “*rded In order to p r o te c t th .

custom er \^ s t V ° Ur cu*to “ *r * *nd th® p r o p r ie ta r y r ig h ts o f BNA in I t s

„ J°a[ ,lnf,U lr i e * conc*rnln« ch* sou rce and nature o f In form ation used in a

cou rt b r i e f , and th e q u es tio n o f whether such use 1 . proper or Im proper, would

be more p rop er ly d ir e c te d to th ose f i l i n g th e b r i e f .

Tours t r u ly ,

1231 Twcnty-fifth Street. Northwest, Washington, DC 20037 □ Telephone (202) 152-4200 o TELEX 285656 BNA1 WSH

March 2. 1989

Rex E. Lee, Esquire

c/o David W. Carpenter, Esquire

Sldley & Austin

One First National Plaza

Chicago, Illinois 60603

Stephen J. Felnberg, Esquire

Asher, Pavalon, Glttler

6 Greenfield, Ltd.

Two North LaSalle Street

Chicago, Illinois 60602

Re: Lorance v. AT&T Technologies. Inc.

Dear Mr. Lee and Mr. Felnberg:

By this letter I as requesting that you agree to remove the

Appendix and the entire reference to the Appendix, the last

sentence in footnote IS on page IS, from Respondents' brief. The

Appendix contains entirely outside-the-record facts prepared, as

I understand It, expressly for the Respondents. The facts are

unpublished and unavailable. There Is no way for the Petitioners

to verify or evaluate the "facts” contained in the Appendix. The

extra-record material in Improper and should be stricken from the

Respondents' Brief. R. Stern, E. Gressman, S. Shapiro, Supreme

Court Practice (Sixth ed. 1986) at 564-65.

As I set forth in the enclosed letter to Ms. Susan Korn, an

employee of BNA Plus, I have determined that the material

enclosed in the Appendix to Respondents' Brief in Lorance and

referred to on page 15, in the last sentence of footnote 15,

does not come from a published source. Rather, I have been

Informed by BNA that it was a "customized" Job prepared to

certain "specifications" for an unnamed "client."

Other than a general reference to BNA there Is no source

cited for the data and conclusions submitted to the Court in the

Appendix and footnote IS of the Brief. As stated in the letter

to BNA:

This BNA work-product, assuming that it

has not been altered in any way, can not be

evaluated without BNA providing the

"specifications" for the job, and the

supporting Information about the sample, the

definitions used, etc. Of course, it Is

1275 K Street, N.W, Suite 301, Washington, D .C 20005 202/682-1300 Frnc 202/682-1312 Modem: 202/682-1318

Rex E. Lee, Esquire

^ c h V i 9E lnb*Pfl' E,qulr*Page 2

o f " b n a ^ s ‘ w o r k p r o d u c t * £ £ ° f l y v a l i d i t y

w o r k p r o d u c t h a s b e e i i t r i n i t y w h o t h e r » * * ’ •

T e c h n o l o g i e s a n d t h T O n l o n ^ n l “ B e d ** A TfiT

e v a l u a t i o n c a n n o t e v e n * £ ° b v l o u « 1 Y . t h i s

s u p p o r t i n g l n f o r a a t i o i ^ ***?? w l t h o u t t h e

t *• Pr.P̂ rVhl0.d0ctflryt ??„d

It. cl"iA. „ r U. r 0M.Prr0dtU„C*p“ ty.ct,0t r tlOni °r — — of

BNArYd|G O id * t e l n ’ d “ t<Kl M a r c h 1 1 9 8 9 k ’ I T h " , * 1 » N A . t o

a n d P < fC te d t h « P e t i t i o n e r s ' " l n J L l r l L I l e t t , r im * n c * ° « e d ) .

e n d n a t u r e o f i n f o r m a t i o n u s e d T h „ C° n ^ n I n f l t h e a ° u r c e

i i t ••• t o t h o s e f i l i n g t h e b r i e f ■

counsel have done in L « I Z , t0 V brl«* Respondents*

evidence that Is not ..*O M additional or different

Court Pr.eH.. >t 564p „_»b* certified record." Supreme

appellate courts have dealt nrn. t? Supreme Court Prsr-ft—

• offend?°n* [by< for exuple] g r . S 7 ^ ~ " ver«iy with such offending matter. 5 6 4 -6 5 nting a motion to strike the

t r o u b ? . ^ : : * ^ . 1" ^ «;-Pond.nt.' Brief i. particularly

feet that the material r J * ltT d , i ‘”Ce ln th« Brief to ItZ

nuhl’J th,t l* un*v,1l»ble to thedCourt* * commissionedpublic. Nevertheless, the °PP08lng counsel, or the

study .s . "representative ^ Pefer to Private

agreements." I<,P at 1 5 n Js* °f e°“ *ctlv. bargaining

Defendants' Brief Aoao **all?nderrdi-h,*Ct* Presented In the

technique ln bringing to the Court's "o-called BrandsIs brief

facts which bear ^ p o n ^ t h ? * " BS-bll,he<! Mterlal

l0n‘ SuEremeCourt Practice *be./«»«onableness of The Respondents seek to introdn^C~ L V 865 (Raphaels added)

^ M l « h e d material /moreover0* t h f ° ? the SuPr« ' Co? « developed. Irrelevant to the ' f*1® facte are prlvatelv

and subaltted without any foiid?iV>10,M*“* °f *ny legislation

presentation of these fast. d? ? ° n or authentication The

district court since" before S T

the least, it l« inappropriate thit it ^ ® n ••tabllehed; to say

to present to the Supreme C o u r t ^ M ^ Respondents have sought

record ..ferial from somcTunldentiMe<i “C i ? . * h*d '

Rex E. Lee, Require

Stephen J. Felnberg, Esquire

Merch 1. 1969

Page 3

Since the Petitioners' Reply Brief Is due on March 7, 1989,

the Petitioners Bust have a reply by 3:00 p.m. on Friday, March 3

as to whether the Respondents Mill agree to remove the Appendix

and footnote IS from their Brief. If we do not receive such a

commitment, then we will have to respond to the Respondents' use

of this material In our Reply Brief.

I have had this letter sent by fax to David Carpenter (312-

853-7312) , Stephen J. Felnberg (312-263-1320), and Charles C.

Jackson (312-269-8 869) on March 2. A copy was also sent by

Federal Express to each of these attorneys for delivery on March

3. I also sent a copy, hand-delivered, to Robert Weinberg on

March 2.

Very truly yours.

Barry Goldstein

BG:oet

Enclosure

cc: Robert Weinberg, Esquire

Charles C. Jackson, Esquire

Richard J. Lazarus, Esquire

Donna J. Brusoski, Esquire

Si d l e y 8 c A u s t i n

Om e F i b s t N a t io n a l P u u

C h ic a o o , Il l in o is 6 0 6 0 3

TILS p h o n e Olfi: 6 6 3 - 7 0 0 0

Te l e x 8 5 - 4 3 6 4

March 3, 1989

* u w w il u a m t r a m

OMOOM, M 4 I MA. IN O L U ID

Barry Goldstein, Esq.

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

1275 K Street, N.W.

Suite 301

Washington, D.C. 20005

Re: France v. AT&T Technologies

No. 87-1428 (U.S. Supreme Court)

Dear Mr. Goldstein:

This is a reply on behalf of both respondents to your

letter of yesterday, March 2, 1989. We were surprised to learn

both that you decided at this late date to review the BNA

materials discussed in our brief (filed January 23, 1989) and

that BNA denied you access to them. We have therefore telephoned

BNA and consented to the release of any material which cannot be

released without our consent. In addition, we are enclosing

herewith the materials that BNA would not show you and that it

provided us: (1 ) its statement of research methodology and

results, (2) its computer printout of the contracts, and (3) the

table analyzing contracts with departmental seniority. We are

faxing this material to you today and are separately sending it

Federal Express for delivery tomorrow.

tru8t that this fully addresses your concerns on

what should be a noncontroversial point: that departmental

seniority systems are commonplace.

Very truly yours,

'<■£ Cc/.

David W. Carpenter

DWC:dsg

Enclosures

cc: Rex E. Lee (w/o enclosures)

Charles C. Jackson (w/o enclosures)

Stephen J. Feinberg (w/o enclosures)

Robert M. Weinberg (w/o enclosures)

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY A RESULTS

BNA PLUS, the custom research and document retrieval division of The Bureau of

National Affairs, Inc, surveyed collective bargaining agreements in BNA's sample file of 399

contracts to determine the prevalence of departmental seniority provisions in collective

bargaining contracts.

The Bureau of National Affairs, Inc is a private employee-owned publishing company

specializing in labor, business, tax, legal, environment, and economic issues. BNA maintains a

collection of more than 3,000 agreements, which is maintained primarily for the company's

Collective Bargaining Negotiations and Contracts service. The file also is used for research

purposes. The collection is kept up to date with the latest contract renewals or amendments.

Within the collection, a sample of approximately 400 contracts is maintained with regard to a

cross section of industries, unions, number of employees covered, and geographical areas. The

sample is the basis for the CBNC analysis of basic patterns in union contracts, conducted every

three years.

To determine the prevalence of departmental seniority provisions by industry, BNA

PLUS labor analysts researched the contracts in the sample database (a listing of the contracts,

by industry, is attached). One contract has been deleted from the sample and one was unavail

able for examination. Of the 398 contracts examined, 359 (90 percent) contained language

regarding seniority. For the purposes of this research, as agreed. BNA PLUS included as depart

mental seniority those instances where seniority is Based on some subunit of the workforce

(departments, sections, occupational groups, etc) rather than length of service at a plant or with

the company.

The project was coordinated by the BNA PLUS senior labor analyst, who has extensive

experience in the labor area. In addition, the CBNC managing editor was available for consulta

tion. A summary of findings is presented in the attached tabic

1. Mary Dunn

Managing Editor, CBNC

Susan Korn

Senior Labor Analyst, BNA PLUS

Oop̂ IgM © tSSS by Thu Bursau St NaSenst NUn, few.

NAACP LEG AX DEFENSE

AND EDUCATION AX FUND, INC.

Suite 301

1275 K Si. NW

W uhufiou DC 20005 202/6*2-1300 Fax: 202/6*2-1312

March 3, 1989

David W. Carpenter, Esquire

Sidley 6 Austin

One First National Plaza

Chicago, IL 60603

RE: Lorance v. AT4T Technologies

No. 87-1428

Dear Mr. Carpenter:

I have received the letter dated March 3rd, fros both

respondents in response to my letter of March 2nd. The response

does not address the concerns of the Petitioners.

For the reasons set forth in sy letter of March 2, 1989, the

outside-the-record eaterial contained in the Respondents' Brief

should be stricken.

In addition, the documents that you enclosed with the March

3, 1989 latter inadequately describe the private project that

you sponsored. (He will lodge these documents with the Suprene

Court if the saterial is not removed fros the Brief). For

example, the docusents do not describe the seniority provisions

from the contracts. All that is listed is the cospany name,

industry, 'sic' coda, and the expiration data for the contract.

This is particularly important because these documents make

clear that the chart contained in the Appendix to Respondents'

Brief is mislabeled and misleading. The page listed as 'Research

Methodology 4 Results' states as follows:

For the purpose of this research, oa agreed.

BNA Plus included as departmental seniority

those instances where seniority is based on

some subunit of the workforce (departments.

gectiong, occupational groups. *&£*.) rather

than length of service at a plant or with the

company. (Emphasis added)

*■>. us T V NAACP L ay ! P r W A t i r .mss . I F m s i . l t . (LOP) i. — yew

a f A t Mwise .I 4 ■ar m .as Ue + e * dvm r mmmi m lCwkmrmi Peep**

(NAACP) .bfc.eg* LDf w M U -dcW by A* NAACP — ta e es m

ax i s ■■ . . ngbu. LDF k s U i s e v e r 3» y e a n ■ «parsa t

pregraat. Staff, office asd M g n

HmamdOgm

M m MM

f f l M s a M m i

N rw V ert. NY M U

M UMW

Pea. m/XM-TWO

434 S. Spring Sc

La* A ag rin CA *

21VO4-M05

H r . 212/4)64*7*

David W. Carpentar

March 3, 1989

Paga 2

BNA Plus, 'the custom research and documental retrieval

division of The Bureau Of National Affairs, Inc.* apparently

’Agreed* With AT&T Technologies to call departmental any measure

of seniority, 'department[el], section[al], occupational, etc.*

As is clear from the research methodology statement, BNA

agreed to call any seniority system other than plant or company

seniority a departmental seniority system.

On the basis of the research methodology statement, BNA Plus

and the Respondents could as easily have called the less than

plant seniority contracts 'sectional* or "etc.* seniority

contracts.

Moreover, the Record in this case does not indicate whether

or not the seniority system developed in 1979, which counted

seniority earned in non-tester jobs differently than seniority

earned in tester jobs, should properly be classified as

'occupational,* 'departmental,' or 'sectional* seniority. The