Rice v The Gates Rubber Company

Public Court Documents

August 25, 1975

6 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Rice v The Gates Rubber Company, 1975. 4d1f712b-c29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/19557023-cb3d-430e-8637-c088d43b5927/rice-v-the-gates-rubber-company. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

. -AuU «JU

L

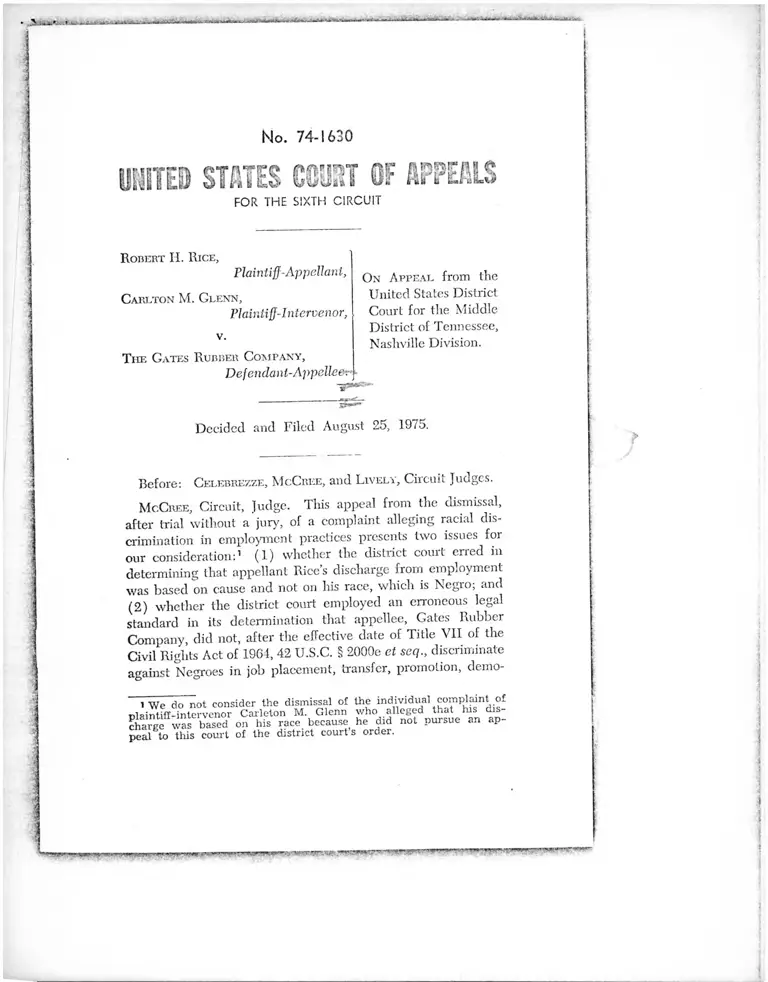

No. 74-1630

■ p c m j w

if* y

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

JW

R obert H. R ice ,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

Careton M. Glenn,

Plaintiff-Intervenor,

v.

T h e Gates Rubber Company,

Defendant-Appellee^

On Appea l from the

United States District

Court for the Middle

District of Tennessee,

Nashville Division.

Decided and Filed August 25, 1975.

Before: Celebrezze, McCree, and L ively, Circuit Judges.

McCree, Circuit, Judge. This appeal from the dismissal,

after trial without a jury, of a complaint alleging racial dis

crimination in employment practices presents two issues for

our consideration:1 (1) whether the district couit erred in

determining that appellant Rice’s discharge from employment

was based on cause and not on his race, which is Negro; and

(2) whether the district court employed an erroneous legal

standard in its determination that appellee, Gates Rubber

Company, did not, after the effective date of Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act of 19C4, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seq., discriminate

against Negroes in job placement, transfer, promotion, demo-

l We do "not consider the dismissal of the individual complaint of

nlaintifl-intervenor Carleton M. Glenn who alleged that his dis

charge wfs based on his race, because he did not pursue an ap-

peal to this court of the district court s order.

•

•

.

...

-.-

t,;.

.,:,

.

, .

,n

-

:..

...

..

..

...

..w

---

---

-

-

....

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

..

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

- -

■*-

CUikMl lu _ ___fettA__ . _ - l i a s - ................... . — . . . . ___ i__ itijtiL „ — u .■

2 Rice, et a l v. The Gates Rubber Company No. 74-1630

tion and discharge.2 We affirm that part of the district court’s

judgment dismissing appellant’s complaint in his own behalf

but hold that it did not apply the correct legal standard in

arriving at its determination in the class aspect of the action

that appellee did not discriminate on the basis of race in its

employment practices.

Robert II. Rice, the appellant, was employed in a classifica

tion described as a banner operator by the Gates Rubber

Company (Gates) on November 9, 1967, and was discharged

on December 15, 1967. Shortly after his discharge, Rice filed a

complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commis

sion and received a “right, to sue” letter on September 17, 1971.

He then filed a timely complaint in federal district court on

October 15, 1971, alleging that lie had been discharged by

Gates because of his race and that the company discriminated

against Negroes as a class in job placement, promotion, trans

fer, demotion and discharge. He sought back pay for himself

and equitable and other appropriate relief on behalf of the

class. 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g), (k).

In support of his personal claim Rice testified that he had

been given inadequate training for the job of banner operator

and that he had been accorded a shorter probationary period in

which to qualify for that classification than that granted to

white employees. The collective bargaining agreement in effect

at the time of Rice’s employment between the Gates Rubbei

Company and the United Rubber, Cork, Linoleum, and Plastic

Workers of America, permited Gates to hire an employee for

a sixty day probationary period before it was required to de

cide whether the employee was satisfactory. If, at the end of

the sixty day period, the employee had qualified, lie was made

2 In a memoriam opinion accompanying its order issued on May

25 1972 the district court determined that [p]lamtifT may only rep

resent black applicants and prospective black applicants who are

subjected to discriminatory practices relating to pronmtions, trans

fers and job placements subsequent to their initial hiring,^and those

employees who are discharged because of their race. Neithei

party challenges the appropriateness of this class.

^ * iinriiYfir t l u r T * »„■ n j________ .... .....-.■ . . . . . . . _

No. 74-1630 Rice, et al. v. The Gales Rubber Company 3

a permanent employee entitled to all the protections of the

collective bargaining agreement. Rice, who was discharged

before the expiration of the probationary period for the stated

reasons that he could not make production and that there was

little hope he would be able to do so at the end of sixty days,

complained that other employees, who were white and who

had also been unable to meet production quotas, had been

afforded the full sixty day period in which to do so.

The district court, which refused to credit Rice’s testimony in

several respects, found that most employees met the produc

tion quota after three weeks of training; that Rice’s trainers had

been capable and experienced persons; that Rice had not com

plained of inadequate supervision until the day of his dis

charge; and that the two white employees who had taken long

er than five weeks to qualify had either been assigned to work

with an equally inexperienced employee on the machines, or

had been assigned to work on a more difficult “one-man” ma

chine. It concluded that P,ice had been discharged not be

cause of his race but because lie was unable to perform satis

factorily. In making this judgment the district court also

considered Rice’s poor employment record both before and

after his brief association with Gates.

After a careful examination of the record, we conclude that

the district court’s determination that Rice was fired for fail in ao

to meet production quotas, and not because of his race, has

ample evidentiary support. The record reflects that Gates Rub

ber Company had adopted a rule that in order to qualify as a

banner operator, a relatively simple task, an employee’s produc

tion had to be “a hundred percent twenty-four out of forty

hours in a given week.” Rice’s production was 38 percent the

first week, 52 percent the second, 54 percent the third, 59

percent the fourth and 74 percent the fifth week or an average

of 55.4 percent during the five week period. In contrast, eleven

other banner operators had achieved production rates of over

one hundred percent during their probationary periods and had

achieved an average of 92.45 percent during that time. Ac-

i

I

i

--- --------

4 Rice, ei al. v. The Gates Rubber Company No. 74-1630

cordingly, we bold that the district court did not err in dis

missing Rice’s personal claim.

In support of the class action aspect of the complaint that

Gates discriminated against Negroes in job placement, transfer,

promotion, demotion and discharge, Rice, relying on the oft-

quoted maxim that “figures speak, and when they do, Courts

listen,” introduced primarily statistical evidence. Brooks v.

Beto, 366 F.2d 1, 9 (5th Cir. 1966), carl, denied, 386 U.S. 975

(1967). This evidence showed that Gates Rubber Company

which had a manufacturing plant in Nashville, Tennessee, a

city having an employable population that is 16 percent Negro,

did not hire a single Negro until 1966. In 1966, however,

Negroes filled 13 of the 467 positions available; in 1967, 11 oiu

of 429; in 1968, 27 out of 552; in 1969, 36 out of 575; in 1970,

30 out’of 55; and in 1971, 36 out of 612. Moreover, until Sep

tember 1968, Negroes were always placed in the lowest paying

job classification within one of the several seniority depart

ments. From 1968 until Rice filed his complaint in this action

in the district court, all Negro employees but one occupied

positions in the lowest job classification within a single depart

ment.

In 1971 the Gates Rubber Company instituted an affirmative

action program. The parties agree that its implementation

has been successful particularly during the years 19(2 and

1973 after Rice had filed his complaint in federal district court.

The district court in arriving at its determination that Gates

did not discriminate against Negroes as a class in job place

ment, promotion, transfer, demotion and discharge focused on

the company’s ultimate performance at the end of the period

from 1967 through 1973.3 On appeal, Gates urges us to

3 1n1wT7omplaint Rice also charged that the departmental seni-

ority system employed by Gates, although facially neutral, had

the effect of perpetuating past discrimination against J^egro em

ployees. Transfer within Gates Rubber Company s iNashville plant

is accomplished by three different procedures. First, Gates reserves

the right to transfer employees by promotion or demotion, beconci,

an employee mav “bid” for a iob in his own depaitment, and

the vacancy is filled on the basis of seniority. Third, if an em-

. . . . . nwi«n l * iini

No. 74-1630 Rice, el a l v. The Gates Rubber Company 5

restrict our examination of tlie charge of class-based disciimina-

tion in a similar fashion. This standard is, however, erroneous.

As the court stated in Parham v. Southwestern Bell Telephone

Co., 433 F.2d 421, 425 (8th Cir. 1970),

[t]he crucial issue in a lawsuit of this kind is whether the

plaintiff establishes . . . . bias at the time of his . . . em

ployment and subsequent complaint to the EEOC, not the

employment practices utilized two years later.

See also United States v. International Brotherhood of Elec

trical 'Workers, Local No. 38, 428 1.2d 144, 149-ol (6th Cir.),

cert, denied, 400 U.S. 943 (1970). The record before us

discloses that the employment practices of Gates were radically

different at the time when Rice was an employee from those

at the time when this case went to trial. Accordingly, the case

must be remanded to permit the district court to determine

whether Rice established a prima facie case that at the time he

was employed by Gates, the company discriminated against

Negroes as a class in job placement, promotion, transfci, de

motion and discharge. If the court should determine that Rice

did establish a prima facie case, it should consider whether

Gates rebutted it. See McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411

792 (1973). The belated actions of Gates Rubber Company,

although commendable, are not sufficient to rebut a prima

facie case of discrimination at an earlier time, if one should be

established. Its affirmative action program may be relevant,

however, in formulating appropriate relief.

plovee desires to transfer to a position in one of the other seniori

ty departments, he applies for a “self-requested” transfer. Because

of Gates’ departmental seniority system, a person hired to work

in the department in which a vacancy occurs and who has only

one day of seniority is able to “outbid” an employee from another

department who has ten years of seniority. Should the district

court, on remand, determine that Gates was guilty of class-based

discrimination, it may wish to consider the effect of the facially

neutral departmental seniority system. See, e.g., Griggs v. IJukc

Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971), Pettway v. American Cast Iron

Pipe Co., 494 F.2d 211 (5th Cir. 1974), Head v. Timken Roller

Hearing Co., 486 F.2d 870 (6th Cir. 1973).

- ------

*m

tX

4A

]-i

m

».i

u

-..

aa

lk

m

M

ti

ti

id

aa

it

fi

■.

■■

^

■

^

^

i

a.

..;

~

---

---

--

.

* •

__ _ _^ ... I « h ii> -n n m H I

"V*T’~ —’-

6 Rice, cl al. v. The Gates Rubber Company No. 74-1630

We affirm that portion of the judgment of the district court

dismissing the personal complaint of Rice but reverse that

part dismissing the class action and remand the case for

further proceedings with respect to it. See Parham

v. Southwestern Bell Telephone Co., supra, United

States v. International Brotherhood of Electrical Work

ers, Local No. 38, supra. Should the court find, employing the

correct legal standard, that Gates Rubber Company did dis

criminate against Negroes before 1970, it may consider the

affirmative action program instituted by Gates in 1971 in de

vising its remedy.4 And, even though Rice has failed to prove

his individual claim, if the court determines that his class

action is well-taken, it may, in its discretion, award an at

torney’s fee. 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(k). See Newman v. Biggie

Park Enterprises, 390 U.S. 400 (1968), Parham v. Southwestern

Bell Telephone Co., supra.jl ivnv wo.j unyyiit-.

Affirmed in part and reversed in part and remanded for

further proceedings consistent with this opinion.

4 After trial but while the case was pending before the district

court, Gates Rubber Company sold its Nashville manufacturing plant.

Because of the court’s determination that Gates had net discriminated

against Negroes, it did not consider what effect this sale should

have on the formulation of appropriate relief on behalf of appel

lant. Should the district court on remand make the contrary de

termination, it should consider the effect of the sale in formulating

appropriate relief.

-r-T-

;