Correspondence from Winner to Phillips; from Winner to Leonard; Supplemental Memorandum in Support of Motion for Further Relief

Public Court Documents

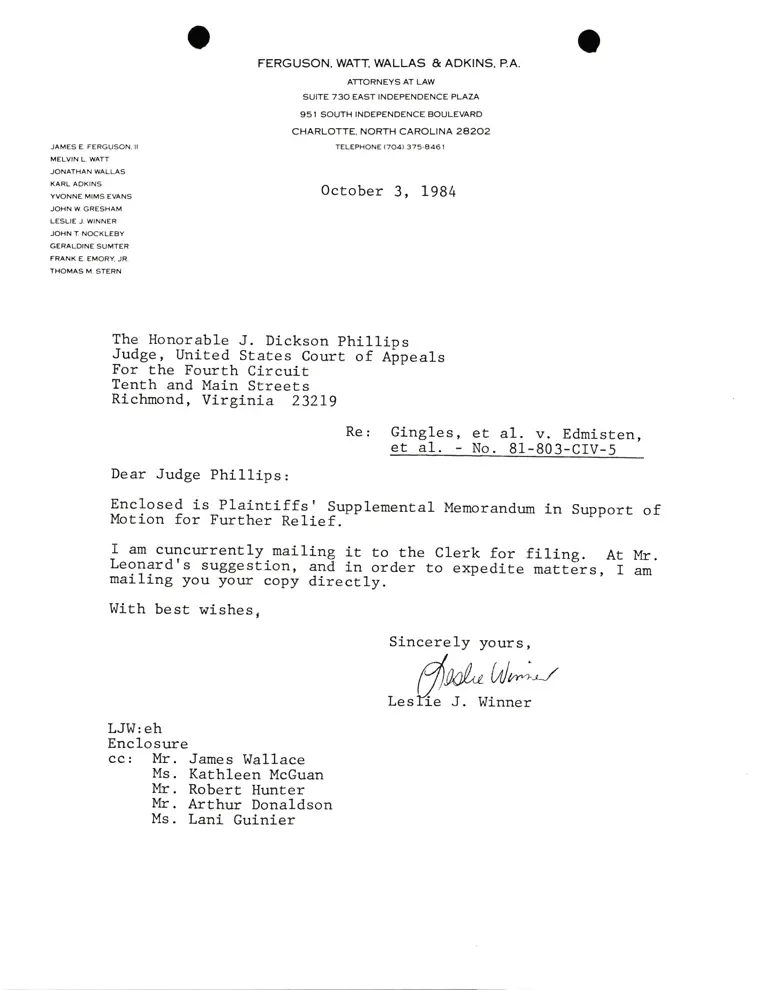

October 3, 1984

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Hardbacks, Briefs, and Trial Transcript. Correspondence from Winner to Phillips; from Winner to Leonard; Supplemental Memorandum in Support of Motion for Further Relief, 1984. a0760dcd-d592-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/19d9204f-349a-457e-a232-d831b5266035/correspondence-from-winner-to-phillips-from-winner-to-leonard-supplemental-memorandum-in-support-of-motion-for-further-relief. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

FERGUSON, WATT, WALLAS & ADKINS, P.A.

SUITE 73O EAST INOEPENDENCE PLAZA

95I SOUTH INDEPENDENCE BOULEVARO

CHARLOTTE, NORTH CAROLINA 242c2

TELEPHONE (704) 375,846 r

October 3, 1984

JAMES E, FERGUSON. II

MELVIN L, WATT

JONATHAN WALLAS

KARL AOKINS

YVONNE MIMS EVANS

JOHN W, GRESHAM

LESLIE J, WINNER

JOHN I NOCKLEBY

GERALOINE SUMTER

FRANK E, EMORY JR,

THOMAS M, STERN

The Honorable J. Dickson phillios

Judge_, United States Court of Aipeals

For the Fourth Circuit

Tenth and Main Streets

Richmond, Virginia 23219

Re: Gingles, €t a1. v. Edmisten,

et a1. - No. 81-803-CIV-5

Dear Judge Phillips:

Enclosed is Plainti_ffs' grpplemental Memorandum in support ofMotion for Further Relief.--

r am cuncurrently.mailing it to the clerk for filing. At Mr.Leonard's suggestion, and in order to expedite *"ttErs, r ammarlj-ng you your copy directly.

With best wishes,

Sincerely yours,

dwUilt'*"-'t

+{.Lesll_e J. Winner

LJI,I: eh

Enclosure

cc: Mr. James Wallace

Ms. Kathleen McGuan

Mr. Robert Hunter

I.{r. Arthur Donaldson

Ms. Lani Guinier

FERGUSON, WATI WALLAS & ADKINS, P.A.

ATTORNEYS AT LAW

SUITE 730 EAST INDEPENOENCE PLAZA

95I SOUTH INOEPENDENCE BOULEVARD

CHARLOTTE. NORTH CAROLINA 24202

TELEPHONE (704) 375-446 IJAMES E, FERGUSON, II

MELVIN L, WATT

JONATHAN WALLAS

KARL AOKINS

YVONNE MIMS EVANS

JOHN W GRESHAM

LESLIE J, WINNER

JOHN T NOCKLEBY

GERALDINE SUMTER

FRANK E, EMORY JR,

THOMAS M, STERN

October 3, 1984

Honorable J. Rich Leonard, Clerk

United States District Court

Eastern District of North Carolina

United States Post Office and Courthouse Building

310 New Bern Avenue

Raleigh, North Carolina 27611

Re: Gingles, et al. v. Edmisten,

et al. - No. 81-803-CIV-5

Dear Mr. Leonard:

Enclosed please find for filing Plaintiffs' Supplemental

Memorandum in Support of Motion for Further Relief. Ln

accordance with our conversation, I am enclosing four (4)

copies: one to be fi1ed, one for Judge Dupree, one for

Judge Britt, and one to return to me (in the enclosed

envelope) . I have sent Judge Phillips' copy to him in

Richmond by Express Mai1.

Thank you for your assistance.

Sincerely

.frk

yours,

l/,L-*^/

Winner

LJW: eh

Enclosure s

cc: Mr. James Wallace (by Express Mail)

Ms. Kathleen McGuan

Mr. Robert Hunter

l,Ir. Arthur Donaldson

Ms. Lani Guinier

t?

/4'

IN THE I]NITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

MLEIGH DIVISION

MLPH GINGLES, et a1.,

Plaintiffs,

v.

RUFUS L. EDMISTEN, €r al.,

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

CIVIL ACTION

NO. 81-803-Crv-5

De fendant s .

SIJPPLEMENTAL MEMOMNDIIM IN SI]PPORT

OF MOTION FOR FURTHER RELIEF

On September 21, L984, plaintiffs moved that the Court order

defendants to conduct election for representatives to the North

Carolina House of Representatives (',the House") from Wilson,

Edgecomb and Nash counties pursuant to a court-ordered single

member district plan. on october 1, 1984, the Attorney General of

the United States, acting through the Assistant Attorney General

for civil Rights, entered an objection, pursuant to s5 of the

voting Rights Act, 42 u.s.c. S1973c, to the House Districts which

defendants had proposed for those counties. A copy of this letter

is attached as Plaintiffs' Exhibit 100. The plan objected to by

the Attorney General cannot be used for an election. In order to

have elections for representatives from this area prior to the

time the General Assembly convenes on February 1, 19g5, this court

must require the use of a Court-ordered pIan. This Court should

exercise its jurisdiction to require that elections be held

promptly and 1egal1y.

Under The Circumstances This Court Should

Require Elections To Be Held.

Defendants' position is that the Court should delay elections

until 1986 so that defendants can have another chance to propose

a remedy to the sectLon 2 violatio.r.U see De.fendants' Response

to Plaintiffs' Motion filed september 27, 1984 ar 3-4. The ef-

fect of this proposal would be to allow the four white incumbents,

who were elected from an election district which the Court has

determined violates 52 and whose terms of office will have expired,

to remain in office for another session of the General Assembly.

For two more years, the black citizens of that District would be

denied the opportunity to elect representatives of their choice.

Although it is understandable that the incumbents would like to

remain in office without standing for reelection, rto interpretation

of the Voting Rights Act and no equitable doctrine supports this

outlandish result.

wise v. Lipscomb, 437 u.s. 535 (L976) may require rhar a

jursidiction be given an opportunity to fashion a remedy to a

violation, but it does not require that the jurisdiction be given

multiple opPortunities. Indeed, the Court specifically notes that

the District Court has ample jurisdiction to devise and implement

I.

L/ oefendants propose alternatively that elections be held in"1"!9 Epring 1985.i' Given that the Lelislature does not conveneuntil February_ 1985,_ ED enacted plan w6uld have to be precleared,

and it takes Lbout three months to conduct an election, it is un-1ikely that new representatives could be elected before the legis-Iatgre-adjourns, 3s is_its custom, in Jrly, 1985. There cert"i"fy

would be no incentive for the incumbent li:gislators to speed the

process.

-2-

its own plan to avoid frustration of the election process. Id. at

542. This sentiment is echoed by the Supreme Court in McDaniel v.

Sanchez, 452 u.s. 130, n.35 (1981), in noting that District courts

have Power to fashion interim remedies to avoid dilatory tactics

of incumbents who would otherwise continue to represent illegal

districts d.uring the $5 review proce

"".2/

Furthermore, it is the intent of Congress that the District

courts use their equitable powers to remedy violations of 52. As

stated in the senate Report, "The court should exercise its

traditional equitable powers to fashion the relief so that it

completely remedies the prior dilution of minority voting strength

and fully provides equal opportunity for minority citizens to

participate and to elect candidates of their choice.', senate

Report No. 97-471, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. (L982) ("S. Rep.") ar 31.

See also the remarks of the principal sponsors of the Voting Rights

Amendments of 1982 ar 128 Cong. Rec. H3g41 (daily ed. 6/23193)

(remarks of Rep. Sensenbrenner) and IZB Cong. Rec. 56969 (dai1y

ed. 6/17 /82) (remarks of Sen. Kennedy).

Allowing i1lega1ly elected incumbents to remain in office

after their terms have expired does not provide a remedy. Ac-

cording to the timetable proposed by the Director of the State

Board of Elections, Defendants' Exhibit 84, it will take

, Z/ oefendants cite in support of their proposition the unpub-lished 5th circuir case of cook v. Luckerr isti-, cir. 19g4). b.:fendantsdidlotS.upp1yacffib1ishedopinionbutit

i" pleiltiffs' information that Cook was a one person one vote casein which the District Court gave-EEE defendant iro opportunity toremedy ]ts_violation and in fashioning interim refibi totaffy ie-yi:99,.1" legislarive plgr i-nstead of"making just rhose chanles-needed to remedy- the violation. The case iI not controlling"sincedefendants here- have had an opportunity to propose a remedyf

-3-

approximately three months from the time districts are known to

conduct an election. The only way for defendants' viol-ation of

52 to be remedied is for this Court to order an election. Defen-

dants have had their opportunity to propose a remedial p1an. The

Attorney General objected to that proposal because he could not

conclude that it was not adopted without a discriminatory purpose.

Plaintiffs are no\^r entitled to a remedy to allow them, for the

first time, to have an opportunity to elect representatives of

their choice.

II. Plaintiffs' Proposed Plan Does Not Require

S5 Preclearance.

Plaintiffs have proposed that the court adopt as a remedy

H400N54 (plaintiffs' Exhibit 93) , as modified in paragraph 11 of

Plaintiffs' Motion for Further Relief. Defendants assert that

the court cannot adopt plaintiffs' proposed plan unless it is

precleared. This proposition is inconsistent with the purpose of

55 of the voting Rights Act, has no legal precedent, and would

lead to a ludicrous result.

Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act applies "Whenever a

state or political subdivision [which is covered by $5] sha11

enact or seek to administer any voting qualification or prerequi-

site to voting, or standard, practice, or procedure . " 42

U.S.C. S1973c. It seems clear that if the State holds an election

pursuant to a plan proposed by plaintiffs and as required by Court

order, it has neither enacted nor sought to administer the plan.

The purpose of 55 is "to insure that old devices for dis-

franchisement would not simply be replaced by new ones." s. Rep.

at 5. Congress extended 55 in L982 because it was concerned that

-4-

jurisdictions would act to eliminate the fragile gains which had

been achieved in voting rights. s. Rep. at 10. This danger exists

only if the jurisdiction has initiated the proposal. There is no

danger that black plaintiffs will act to eliminate their own gains

in voting rights, and there is no reason to believe that Congress

intended to protect black voters from themselves.

The Court in McDaniel v. Sanchez, supra, addressed the cir-

cumstances under which Court-ordered remedies must be precleared.

The question addressed was "whether a reapportionment plan sub-

mitted to a District court by a legislative bodv of a covered

jurisdiction requires preclearance." 452 U.S. 132 (emphasis

added). The Court reviewed the purpose of 55 and reasoned that

"the essential characteristic of a legislative plan is the exer-

cise of legislative judgment." rd. at 152. The Supreme court

concluded that whenever a jurisdiction submits a proposal that

reflects its choices, whether or not a court has required that

submission, S5 is applicable. Id. at L52.

Because the purpose of 55 is to prevent jurisdictions from

backsliding, the supreme court in McDonald v. sanchez, supra,

determined that the distinction between a legislative plan and a

court ordered plan was whether or not it was proposed by a

legislature. Because plaintiffs are neither a legislative body

nor a covered jurisdiction, their proposal is not a legislative

p1an. Plaintiffs know of no case 1aw that supports the proposi-

tion that plaintiffs' proposed plan must be precleared.

Finally, the requirement of preclearance of plaintiffs'

proposal would lead to an absurd result. i.Ihen a voting change

is submitted to the Attorney General, the burden of proof is on

-5-

the covered jurisdiction to demonstrate that the plan has neither

discriminatory purpose nor discriminatory effect. Georgia v.

united stares, 411 u.s. 526, 536-539 (1973). rf a courr orders

use of a plan proposed by plaintiffs, the defendant jurisdiction

would have no incentive to meet this burden of proof and every

incentive to delay the process to avoid implementation of the

Court's remedy. By this method, the incurnbents could stay in of-

fice forever. congress could not have intended this result.

III. The

of

Court Should Not

The Court-Ordered

Defendants' proposed remedial districts consist of House

District ("HD") 1170, a single member district which is 697" black

in population, and HD ll8, a three-member district. The Attorney

General objected to both HD #70 and HD #9. The basis of objection

to HD 1170, the majority black single member district, was the

contention that the particular configuration of HD llTO was adopted

for the purpose of preventing defendants from being required to

subdivide the remaining three-member district into single member

districts, one of which would have a substantial minority voting

influence. The contention was that the House rejected H400N62,

its original 3-1 plan, when it discerned that a single member

disLrict configuration with a district with significant black

influence would result should the Court require the State to sub-

divide H400N62's three-member district into single member districts.

See Plaintiffs' Exhibit 100. Instead the State enacted H400Ngg

which had a single member majority black district configured so

that if the remaining three-member district were subdivided, none

Use HD #70 As The BasisDistricts.

-6-

of the resulting single member districts would have significant

black inf luenc u.2l

Because the Attorney General objeeted to the configuration of

HD 1170, the court may not use it as part of its remedy. unitq4

states v. Bord of supervisors of warren co., 429 u.s. 642 (L971)

(per curiam)

IV. The Court Should

Held On November

Require The Election To Be

6, 1994.

Defendants have responded to plaintiffs' request that elections

be held on November 6, 1984, with a proposal that the elections be

held on November 20,1984, a mere two weeks after the general

election and on the heels of Thanksgiving weekend. The affidavits

of Messrs. Fitch, Butterfield, Willingham and Walker demonstrate

the likelihood that voter turnout will be very 1ow if voters are

expected to vote for the sixth time in L984. In order to have an

el-ection in which voters can actually exercise their franchise and

in order to avoid the possibility of the winners being determined,

primarily, by the flukes of disparate turnout, plaintiffs propose

the following modification to Defendants' Exhibit g4 for the

Court's adoption:

October 10, 1984: Legal Publication and Notice of

Primary Election

Filing period opens at L2:00 Noon

Eiling period closes at 72:00 Noon

October 15, 1984;

October 22, 1984:

3/tti. is true because the current HD #70 causes thes-eparation of the black community _in Northein wasfr -ornty fromthe black community in Norrhern [:ag."o*u county. - s;; plaintiffs'Exhibit 8A.

-7-

October 24

October 31, 1984:

November 6, 1984

December 18, 1984:

January 15, 1985:

Absentee voting

First Primary

Second Primary (if required)

General Election

V. Conclusion.

This Court found that House District llg, as enacted by defen_

dants in L982, violates $2 of the Voting Rights Act and gave defen-

dants an opportunity to remedy the violation. The Attorney General

of the united states objected to defendants' proposed remedy because

he could not conclude it was adopted without a discriminatory

purpose. Plaintiffs and, ind.eed, all citizens of wilson, Edgecomb

and Nash counties, are entitled to have an election before the

General Assembly convenes. That is possibre only if the court

exercises its equitable powers to require the election to be held..

This the 3rd day of Ocrober , Lgg4.

.1

a)iu^ I L;,,r,, rii.-,'

ferguson, Watt, I^Iallas & Adkins, p.A.

Suite 730 East Independence plaza

951 Sourh Independence gouleviiJ-

Charl-otte, Uorth Carolina 2g202Telephone: 704/375-9461

J. LeVONNE CHAMBERS

LANI GUINIER

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, New york 10013

Telephone : 272/ 219_1900

Attorneys for plaintiffs

-8-

CERTIFICATF OF SERVICE

r certify that r have served the foregoing supplemental

Memorandum in support of Motion for Further Relief on aIr

other parties by placing a copy thereof in the post office or

Official Depository in the care and custody of the United States

Postal Service addressed to:

Mr. James l,Iallace, Jr.

(Express Mail ) Deputy_Attorney General for Legal AffairsNorth Carolina Department of JlsticeRaleigh, Norrh Carolina 27602

Mr. Arthur Donaldson

!gfk", Donaldson, Holshouser & Kenerly

309 N. Main Street

Salisbury, North Carolina 28154

Ms. Kathleen Heenan McGuanJerris Leonard & Associates, p.A.

900 17th Street, N.\nI. , Suite 1020

Lrlashington, D. C. 20006

Mr. Robert N. Hunter, Jr.

201 West Market Street

Post Office Box 3245

Greensboro, North Carolina 27402

This the 3rd day of Ocrober , tg}4.

Attorne! Plaintiffs