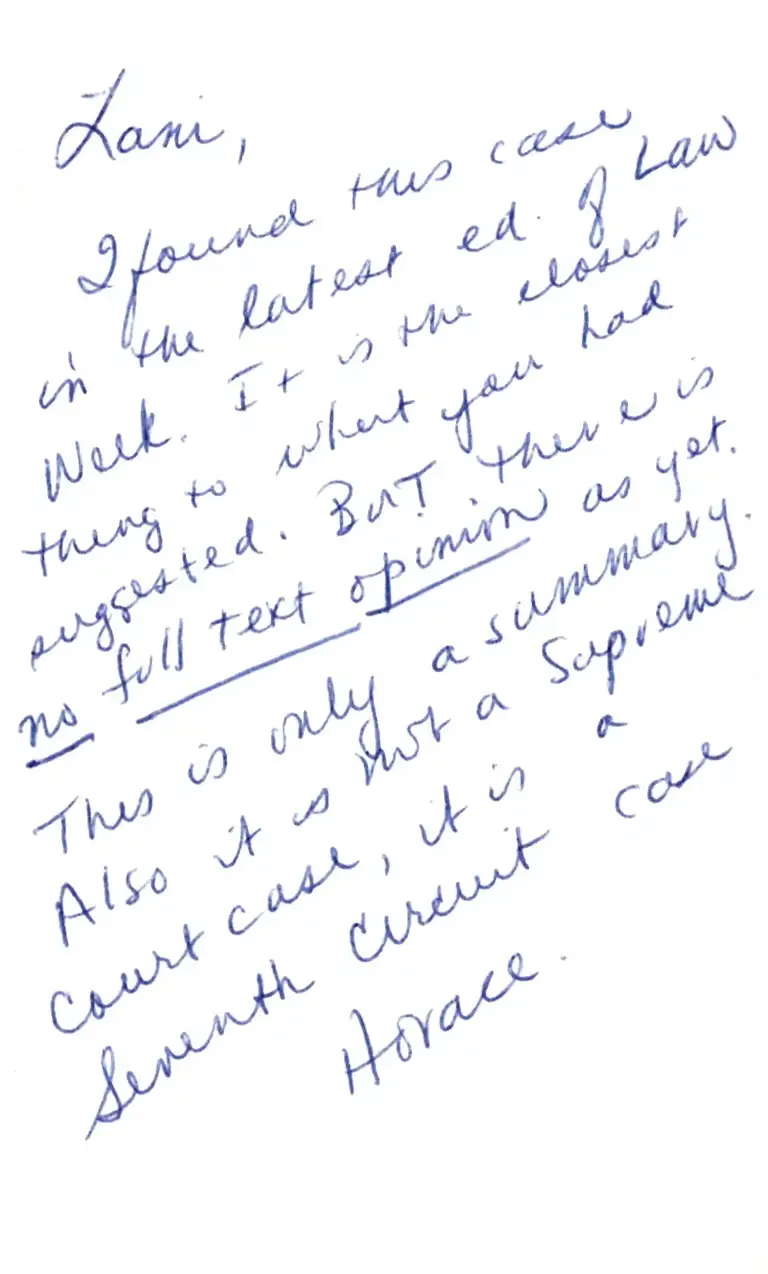

Note from Hutson to Guinier; Legal Research on Employment Discrimination

Correspondence

July 17, 1984

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Note from Hutson to Guinier; Legal Research on Employment Discrimination, 1984. 49d058e6-e192-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1b71b31c-ad36-4f43-84ee-9a1991785f60/note-from-hutson-to-guinier-legal-research-on-employment-discrimination. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

/rrr*t ^ r4ua,D

T,rn{jW

fi* t'^1u_fr*"i,r

wfw#

**T4i^^t1 ^)y4W .p '/

Fiuo,',ffin*

"{^l* Yq^tWY

-1

s3 tw 2028 The United States LAW WEEK 7-t7-84

lic opinion polls, is opposed by most citizcns.

tt liired thc position of hundreds of candi'

datcs on a single political issue, without

howcver cxprcssly advocating the election or

dcfeat of any particular candidate or bclit-

tling the importance of other election issues.

Thc tabloids in question also were not

cxpcnditurcs prohibited by $aalb bccause

they were "news story, commcntary or eol-

torial distributcd thrbugh the facilities of

any t t' pcriodical publication" and hence

cximpted irom the dcfinition of expenditu-re

bv th; l9?4 amendments to the FECA. The

dmpilation of voting records and question-

nairi rcsponses was news, probably not

availablc elsewhcre; and the call to vote pro

lifc was editorial.

Moreover, the special clection editions

wcrc "pcriodical pirblications" within the

meaning of the stitutory exemption' First,

they wJre similar in newsprint, sheet form,

size, and format to the newsletters that the

MCFL published relatively. regularly for

five veari before l9?8. Special election edi-

tioni were published Prior to all elections

since 1974,'thrice bcfore 1978' Secondly'

the legislative history of the newspapgr :x-

cmpti;n shows that Congress intended that

it be a broad exemption, coextensive with

thc First Amendment.

If $441b were intended by Co-ngress. to

orohi6it MCFL's expenditures of printing

ind distributing the newsletters in question,

it would be unconstitutional under the First

Amendment as applied to MCFL because

violative of MCFL freedoms of speech,

Dress. and association. This court's opinion

is based upon three distinctive features of

the expenditures at issue. They were: (l)

independent of any candidate or party; (2)

by a-nonprofitmaking corporation formed-to

aiuance an ideological cause; and (3) for

the purpose of publishing direct political

spccch.' This court concludes that the costs of the

publications in question are more accurately

characterized as speaking than spending

and that in placing the Federal Corrupt

Practices Act in FECA as new $441b Con'

gress did not intend to proscribe the t-ype of

-xpenditure made by the MCFL in 1978.-

Garrity, J.

-USDC Mass; Federal Election Com-

mission v. Massachusetts Citizens for Life,

Inc., No. 82{09-G, 6129184.

thc Age Discrimination in Employmenl Act

(ADEA). The state argucs that agc 50 is a

bona fide occuPational qualification

(BFOQ) for statc police officcrs, and thus

that mindatory retirement at that age is

permissible.

Under the gcnerally accepted stry-dry-d

for evaluating- the adequacy of a BFOQ

defense, as sCt forth in Usery v. Tamiami

Tours, Inc.. 531 F2d 224 (CAs 1976)' and

Orzel v. City of Wauwatosa Fire Dept.' 697

F2d 143 (CA? 1983), an emPloYer must

show that the age qualification is "reason'

ably related to the'cssential operation' of its

business, and must demonstrate, either lhat

there is a factual basis for believing that all

or substantially all persons above the age

limit would be'unable to effectively perform

the duties of thc job, ot that it is impossible

or imDracticable to determine job fitness on

an individualized basis." (Emphasis in

original).

The district court focused its attention on

the meaning of "duties of the job," and'

following thl approach of the Eighth Cir-

cuit in EEOC v. City of St. Paul' 6'll F2d

1162,50 LW 2553 (1982)' rather than that

of the Seventh Circuit in EEOC v' City of

Janesville, 630 F2d 1254 (1980)' decided

that "the policies of the ADEA are best

effected by evaluating the [state's] BFOQ

defense against the requirements of the job

that Ithelergeant] has actually performed

in thi past

"id

it likely to perform-in the

future,; rather than the duties performed

by uniformed state police officers generally'

The district court was fully conscious of

the Droblems posed by its frne-tuning ap

oroath. lt noted that there is no correlation

Ltt*""n rank and strenuous activityi offi-

cers in each rank may or may not be re-

quired to perform such activity. It recog-

nized that "the possibility of inconsistent

treatment of officers of the same rank may

be expccted to cause some difficulties," and

that both officers approaching 50 and those

in charge of duty assignments would have

difficulty making assignment decisions. The

court aiso acknowledged that the kind of

Darticularistic case-by+ase analysis it had

undertaken "might inte rfere with the

smooth opcration of the state pension sys'

tem." This approach may also tempt some

to seek a "safe harbor" assignment, penal-

ize the dutiful, discourage promotion. en-

courage litigation, and necessitate judicial

determinations that turn on quality judg-

ments. such as how sedentary is the assign-

ment, and probability- judgments, such as

how long is ihe assignment likel) to last and

how likell is emerS,enc)- duty.

The ADEA does not mandate this aP

proach. The BFOQ statutor)- exceprion afL

plies "where age is a bona fide o{cupational

quali6cation reasonabll' necessar! to the/-

;;;;i-;;'"iion or il. particuiar busi/

ness." Thi word giving rise ro the differing

internretation of the Seventh and Eighth

Circuits is "occupational " ln Janesville. the

Seventh Circuit held that a chief of police'

being within "the generic class of law cn-

forcement personnel." was subjcct to the

age retirement requirementl it dcemed the

term "particular business" to bc thc critical

one, making irrelevant the fact that a par-

ticular occupation may bc included within

it. In St. Paul, the Eighth Circuit hcld that

"occupations" within a "busincss" should

be eximined and that a firc chief, being

completely able to fulfill his duties, was not

subjlct to the age retirement requirement.

It was concerned with the hazard of apply-

ing a BFOQ to any generic class as deter-

mined by a state.

This court takes a position between these

two decisions. Unlike the Seventh Circuit,

this court can ascribe a meaning to "occu'

pational qualification" that is separate from

:'particulir business." For example. an air-

lihe is a "particular business," but within

that business there are specific occupations

with their own separate training, career pro

gression, and age limitations, such as cap

[ain and first officer (retirement age 60)

and flight engineer (retirement age 70).

When, however, a Person signs uP in a

oaramilitary uniformed force, where one is

iubject to generally unrestricted reassign-

ment and performance of the most strenu-

ous duties 1n an emergency, and undergoes

the military training required of all recruits,

with the expectation of receiving special

pcnsion and disability bcnefits, this court

would be loath to equate particular "assign-

ments," even if of long duration, to

"occupations."

The Eighth Circuit case is susceptible of

two interpretations. lt dealt with the posi-

tion of fire chief; arguably this position was

sufficiently distinct to be considered an oc-

cupation ieparate from that of the rest of

the department. But the court went on to

say, "we cannot believe that the ADEA was

iniended to allow a city to retire a police

dispatcher because that person is too old to-

serve on a SWAT team." If this nicety of

distinction were to govern, this court would

have to say that an age limit geared to those

oerforming at critical times the most stren-

Lous funct-ion of a unit could not be applied

to those performing somewhat less strenu-

ous functions. If such were the law' state

troopers engaged in tracking down and ap

prehending car thieves and drug runners

tould be subjected to an age 50 retirement

requirement, but those who merely had to

chise speeders, to attend truck weighing

stations; and to apprehend drivers under the

influence of alcohol or without proper li-

censes would not be so subjected. This

would atomize the general concept of "oc-

cupation."-Coffin. J.

-CA l: Mahonev v. Trabucco. No' 83-

I

nC,e

Employment Discrimination

AGE DISCRIMINATION_

Messrchusetts' mandetor-v retiremeni ege

of 50 for uniformed state police officers is

bnne 6de occuprtionrl qualifrcetion exempt

from strictures of Age Discrimination in

farphyment Act,

A vctcran police sergeant claims that a

Massachusetts law requiring the retirement

of ell uniformcd officers at age 50 violates

t862.',7 12184

PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE-

Employer's relicnce on stete egency order

remedl'ing discrimination egainst certain

I

i -_:I

I

0l 48-8 l 3el84/$0+.s0

* 7-17-94 The United States LAW WEEK 53 LW 2029

,

employees under stete frir enrployment law

thrt is not inconsistcnt ?ith Title VII of

. 1964 Civil Righrs Aci rbsolutely bers fellon

I employees' lrwsuit cleiming thrt remediel

rction ttken pursurnt to strte order violtt€s

Title VII.

This is a case of first impression rcgard-

ing the relationship bcrween federaI en-

forccment of Title VII of thc 1964 Civil

Rights Act and statc enforccment of state

fair employment laws. The district court

concludcd that a city police dcpartment vio

lated the Title VII rights of reccntly pre

moted male detectivcs whcn it complied

with an order by the Wisconsin fair employ-

fnent agency rcquiring the city to raise the

palaries of female detcctivcs to the level

paid to more scnior male detectives.

The issue of first imprcssion is whether

the city's reliance on a state agcncy order

can be a defense to a Title VII claim. Citing

Williams v. Gencral Foods Corp., 492 F2d

399 (CA7 1974), the district court ruled

that reliance on a state law can never be a

defense to a claim of sex discrimination.

However, a more thorough analysis of the

rclationship bctween state enforcement of

state fair employment laws and federal cn-

forcement of Title VII is rcquired.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 conrains

two provisions regarding the effect o[ the

new federal law on state laws. Section 708

of Title VII provides: "Nothing in this sub-

chapter shall be deemed to exempt or re-

lieve any person from any liability, duty,

penalty, or punishment provided by any

present or future law of any state or politi-

cal subdivision of a state, other than any

such law which purports to require or per-

mit the doing of any act which would be an

unlawful employment practice under this

subchapter." Similarly, gl104 of Title IX

provides: "Nothing contained in any title of

this Act shall bc construed as indicating an

int€nt on the part of Congress to occupy the

6eld in which any such title operates 1o the

cxclusion of state laws on the same subject

matter. nor shall any provision of this Act

be construed as invalidating any provision

of state law unless such provision ls incon-

sistent with any of the purposes of this Act,

or any provisions thereof."

The legislative history, case law, and

structure of the enforcement provisions of

Title VII make clear that Congress intend-

ed that the states play an active role in

ending discrimination and that the "sav-

ings" provisions should not bc construed to

undermine state efforts. Enforcement of Ti-

tle VII is premised on the belief thar states

should be given the first opportunity to deal

with discrimination. Section 706 of Title

Vll requires that when the state has a lan,

prohibiting the unlawful employment prac-

tice and an agenc), authorized to enforce

that la*, then the complainant musl pursue

state remedies bcfore 6ling charges under

Title VII with the EEOC.

Congress clearly intended to encourage

state protection of civil rights in the area of

cmployment discrimination, without aban-

doning the power to usc fedcral cnforcc-

menl mcchanisms when state remedies

prove ineffective. Sections 708 and ll04

were designed to accomplish this goat by'

saving state laws that were consistent with

the goals of Title VII while invalidating

those that hindered protection of civil

rights.

The district court read $708 and the Wil-

liams dccision as eliminating reliance on

any statc law as a defense in a Titlc VII

action. But $708 does not preempt all state

laws, only those that are inconsistent with

the goals of Title VII. Williams is consistent

with this proposition. In that case, the em-

ployer relied on the Illinois Female Employ-

ment. Act to justify discrimination agiinit

female cmployees. This court rejecte-d this

defense lccquge "protective" legislation

such as the lllinois law, which prohibited

women from working more than 48 hours

per week or nine hours per day, acts to

perpetuate scx discrimination in direct con_

travention of the policy behind Title VII

and therefore is not saved by 99708 or I 104.

Williams, however, does not stand for the

proposition that all state laws regarding sex

discrimination are to be discarded. This

would totally undermine the dual enforce-

ment system envisioned by Congress.

The district court's analysis was too sim-

plistic in accepting a pcr se approach to

invalidating state employment laws. Proper

analysis requires that the state law be ex-

amined to determine whether it is the type

of law Congress expected to act as the fiist

line of offense against employment discrimi-

nation or whether it itself is a cause of

discrimination.

The city promoted female detectives to

detective supervisors after unsuccessfully

challenging charges of discrimination from

the state department of human rights pur-

suant to the Wisconsin Fair Employment

Act. That acr is nearly identical to Title

VII; one difference is the date cach began to

prohibit sex discrimination against munici-

pal employees. The state act proscribed this

conduct in 1961, while Title VII did not do

so until 1972. h would be ironic indeed to

hold that Congress, which never indicated

any intention of requiring that state fair

employment laws be identical to Title VII.

intended to invalidate state laws that extend

their protection into more work places than

does Title VII.

The only rational resolution of the issue

here is to hold that reliance on a state

agency's order enforcing the right of a pre

tccted group to be free from emplovmenr

discrimination is an absolute bar ro a suil b\

fellou employees claiming thar the acrion

required bl the remedial order constitutes a

violation of Title VII.-Pell. J.

-CA 7: Grann v. Cirl of Madison, No.

82-2887.612s/84.

Health Care

MENTAL HEALTH_

Court order withdrewing meotrl patient

fr-oq nsVcbotropic medicrtiorq for purpose

of d-etermining wbether remission of pr-

tienl's mentel illness is sufficient to renier

him not subjeci to court-ordered bospitrlizr-

tion or is merely induced by such medica-

tion, violetes due process end Ohio's stetu-

tory rigbt to t estment unless it is based on

medicrl judgment recommending such

rithdrewel.

The patient allegedly shot and killed a

waitress because she failed to give him the

proper amount of a milkshake or short-

changed him. He was indicted for murder

but was found incompetent to stand trial; he

was placed on psychotropic medication at

the state hospital in order to subdue his

antisocial behavior. At a commitment hear-

ing, counsel argued that the patient's men-

tal illness was in remission and he was

therefore not subjecr to hospitalization. The

court, however, found him to be mentally ill

and a threat to society. Unable to determine

the cause of remission, the court further

ordered that all medication be withheld in

order to allow physicians to examine him

while not under the influence of medication.

Under the statute, a person subject to

hospitalization must represent a substantial

risk of physical harm to himself or other

members of society at the time of the com-

mitmcnt hearing. Present mental state is

evaluated upon current or rec€nt behavior

and prior dangerous propensities. The trial

court has broad discretion to rcview the

person's past history. In order to guide that

discretion, this court hereby adopts a "total-

ity of the circumstances" test, which bal-

ances the individual's right against involun-

tary confinement and deprivation of liberty,

and the state's interest in committing the

emotionally disturbed.

Among the factors to be considered at a

commitment hearing are: (l) whether the

person currently rcpresents a substantial

risk of physical harm to himself or society;

(2) psychiatric and medical testimony as io

present condition; (3) whether the person

has insight into its condition so that he will

continue prescribed treatment or seek pro

fessional assistance; (4) grounds for com-

mitment; (5) past history relevanr to estab-

lish the person's degree of conformity to

laws and values of society; (6) the medi6ally

suggested cause and degree of remission, if

any, and the probability remission will con-

tinue should he be released. An individual

whose mental illness is in a state of remis-

sion is subject to hospitalization pursuant to

the statute if there is a substantial likeli-

hood that his freedom will result in physical

harm to himself or society. A nondangerous

individual capable of sun,iving safCly by

himself or with family or friends is noi

subject to confinement.

Civil commitment constirutes a signifi-

cant deprivation of liberty requiring due

o

0t 48-8 I 39/i 84//$0+.50