Correspondence from Lani Guinier to Robert Pear (New York Times) Re: Major v. Treen

Correspondence

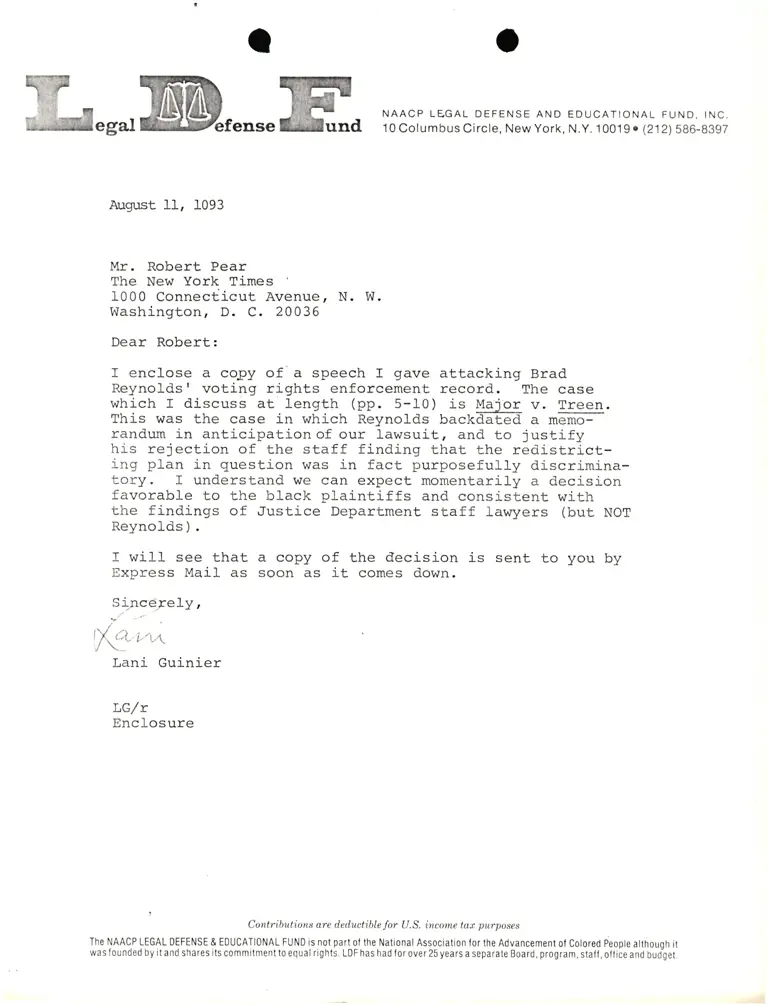

August 11, 1983

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Correspondence from Lani Guinier to Robert Pear (New York Times) Re: Major v. Treen, 1983. 72b94b1d-e592-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1bf41f97-5f65-46b6-b14c-7352b914d4fb/correspondence-from-lani-guinier-to-robert-pear-new-york-times-re-major-v-treen. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

ffiesar@renseH.

Argust 1I, 1093

Mr. Robert Pear

The New York Times

10OO Connecticut Avenue, N. W.

Washington, D. C.20036

Dear Robert:

I enclose a coBy of 'a speech I gave attackj-ng Brad

Reynoldsr voting rights enforcement record. The case

which I discuss at length (pp. 5-10) is Major v. Treen.

This was the case in which Reynolds backdaEed a memo-

randum in anticipation of our lawsuit, and to justify

his rejection of the staff finding that the redistrict-

ing plan j-n question was in fact purposefully discrimina-

tory. I understand we can expect momentarily a decision

favorable to the black plaintiffs and consistent with

the findings of Justice Department staff lawyers (but NOT

Reynolds).

I will see that a copy of the decision is sent to you by

Express MaiI as soon as it. comes down.

Si.ncd;eIy,

LG/r

Enclosure

'

Contributions are decluctible for IJ.S. income tar purposes

The NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE & E0UCATI0NAL FUND is not part ol the National Association for the Advancement ol Colored People although ir

was lounded by it and shares its commilment to equal rights. LDF has had lor over 25 years a separate Board, program, stafl, oflii:e and bud-get.

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND. INC.

10 Columbus Circle, New York, N.Y. 10019o (212) 586-8397

t Y, <l.l_ L,r.+/\

Lani Guinier