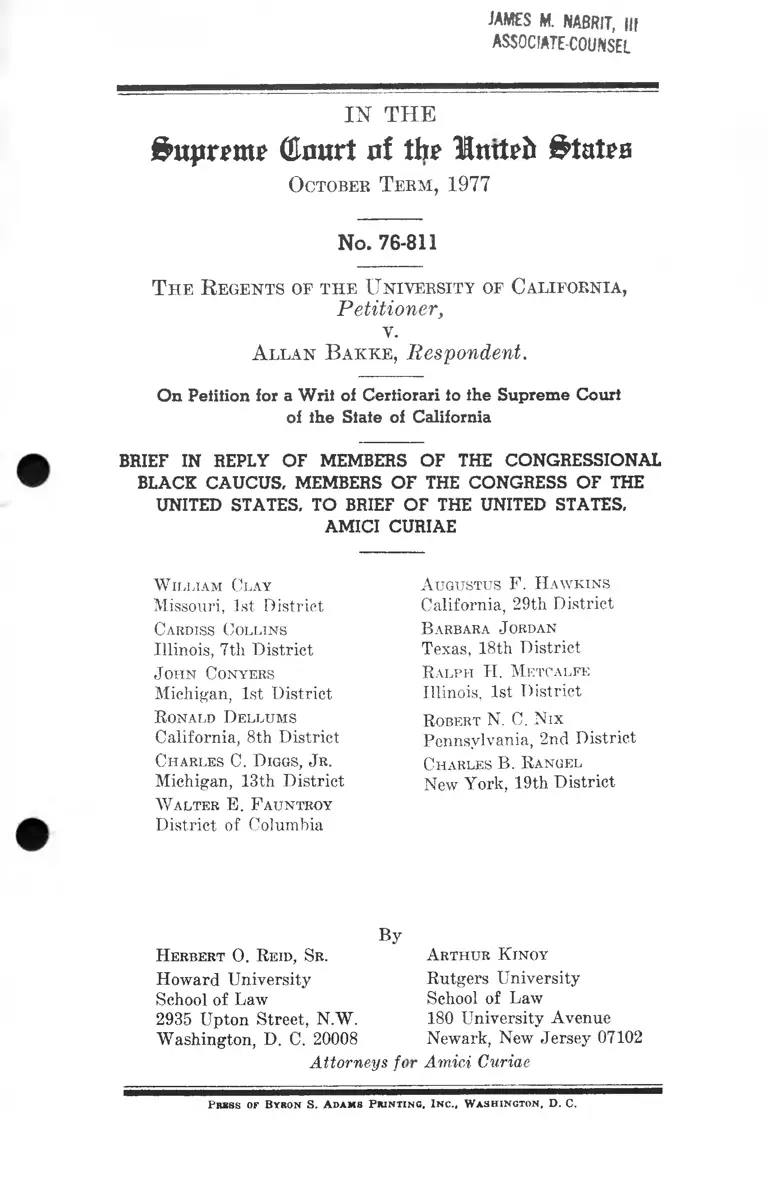

Bakke v. Regents Brief in Reply of Members of the Congressional Black Caucus, Members of the Congress of the United States, to Brief of the United States Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bakke v. Regents Brief in Reply of Members of the Congressional Black Caucus, Members of the Congress of the United States, to Brief of the United States Amici Curiae, 1977. 8b41b341-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1d28a62d-db06-4d9a-bdb1-c2d03a9f79aa/bakke-v-regents-brief-in-reply-of-members-of-the-congressional-black-caucus-members-of-the-congress-of-the-united-states-to-brief-of-the-united-states-amici-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

JAMES M, NABR1T, f|f

associate-counsel

I N T H E

&uprpmp (Unurt of th? llmtefr States

O ctober T e e m , 1977

No. 76-811

T h e R egents of t h e U niversity of C alifof.n ia ,

Petitioner,

v.

A lla n B a k k e , Respondent.

O n Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the Suprem e Court

of the State of California

BRIEF IN REPLY OF MEMBERS OF THE CONGRESSIONAL

BLACK CAUCUS, MEMBERS OF THE CONGRESS OF THE

UNITED STATES, TO BRIEF OF THE UNITED STATES,

AMICI CURIAE

W illiam Clay

Missouri, 1st District

Cardiss Collins

Illinois, 7th District

J ohn Conyers

Michigan, 1st District

Ronald Dellums

California, 8th District

Charles C, D iggs, J r.

Michigan, 13th District

Walter E. F auntroy

District of Columbia

Augustus F. H awkins

California, 29th District

Barbara J ordan

Texas, 18th District

Ralph II. Metcalfe

Illinois, 1st District

Robert N. C. N ix

Pennsylvania, 2nd District

Charles B. Rangel

New York, 19th District

B y

Herbert 0 . Reid, Sr.

Howard University

School of Law

2935 Upton Street, N.W.

Washington, D. C. 20008

Attorneys /<

Arthur K inoy

Rutgers University

School of Law

180 University Avenue

Newark, New Jersey 07102

Amici Curiae

P re s s o r Byhon S . A dams P r in t in g , I n c ., Wa sh in g t o n . D . C.

INDEX

Page

I nterest of th e A m ici Cu r ia e ........... .......................... .. 1

A r g u m e n t ....................... ........................ ........................................ 6

I. The Government’s Argument Fails To Compre

hend the Full Intendment of the Civil War

Amendments .............................................. • • • 6

II. The Government’s Qualifications On the Use of

Race Has No Constitutional, Legal or Rational

Basis ................................................................ 9

III. We Take Issue With the Government’s Conclu

sion That the Case Should Be Remanded . . . . . 12

C onclusion .......................................................................... .. • • • 13

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases :

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, (1954)

349 U.S. 294 (1955) .......................................6,7,9,13

Carter v. Yardley & Co., 319 Mass. 92, 64 N.E. 2d

693 (1946) ........................................................... • 10

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 (1883)........................... 7

Jones v. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968) ................. . 6, 9

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896) . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenhurg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1 (1971) ..................- ................. • .......... 11

United Jewish Organization of Williamsburgh, Inc. v.

Carey, 430 U.S. 144 (1977) ............ .................. .7,11

Constitution :

U.S. Constitution Amendment X I I I ............................ 6, 7

U.S. Constitution Amendment X IY ............................ 6, 7

U.S. Constitution Amendment X V ...........: ................. 6, 7

Oth er A uthority :

Kerner, Report of the National Advisory Commission

on Civil Disorders (1968) ..................................... 7

Woodward, C. Vann, Reunion and Reaction (1951) .. 8

IN THE

( ta r t of % Initri* Stairs

O ctober T e r m , 1977

No. 76-811

T h e R egents of t h e U niversity of C a lifo r n ia ,

Petitioner,

v.

A lla n B a k k e , Respondent.

On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court

of the State of California

BRIEF IN REPLY OF MEMBERS OF THE CONGRESSIONAL

BLACK CAUCUS, MEMBERS OF THE CONGRESS OF THE

UNITED STATES, TO BRIEF OF THE UNITED STATES,

AMICI CURIAE

INTEREST OF THE AMICI CURIAE

The Amici are members of the Congressional Black

Caucus. The Congressional Black Caucus, Inc., a not-

for-profit corporation, was formed on December 10,

1971, to operate exclusively for the promotion of social

welfare of the various peoples of the community who

look to it for guidance and leadership.

The thirteen Black Members of the Congress in

1971 saw the need to formalize their association to be

able to speak with a unified voice for a historically

underrepresented group which still faced the oppres

sion of racial discrimination and economic distress.

By setting forth positions agreed to among themselves

after consultation with persons from the Black com

munities throughout the nation, the Congressional

Black Caucus would articulate the views of a national

constituency in Congress. Stated simply, the Caucus

provides a voice in the U.S. Congress for the concerns

of Black and poor Americans.

The first Annual Dinner of the Caucus, held on June

18, 1971, was extremely successful. In addition to rais

ing funds to sustain the staff operation, the Dinner first

brought the Caucus to national attention as an advo

cate for Black concerns. The national recognition was

solidified when the Caucus met with then-President

Richard Nixon on March 24, 1971, and presented him

with a paper proposing specific recommendations for

governmental action on domestic and foreign policy

issues. The President’s response was not considered

adequate, which strengthened the resolve to build the

Caucus into a national political force to represent the

underrepresented.

Initially, a series of hearings and conferences on

legislative issues were held to gather information

upon which to build a legislative program. The facts

gathered at the conferences wrere assembled to deter

mine priority goals in such areas as Employment,

Health Policy, Minority Enterprise, Education and

Racism in the Military. At the same time, the Caucus

found that many Black citizens were contacting the

Caucus office with individual problems, which was

3

beyond the capacity of a small staff with a legislative

focus to handle.

In 1973, the Caucus delivered a “ True State of the

Union Message” on the House floor in an effort to set

forth the Caucus Members’ view of the nation’s major

issues.

A legislative support network around the legislative

priorities began in 1974. Continuing communication

with Caucus supporters was initiated through a regu

larly published Caucus newsletter, “ For The People,”

and a legislative update of key issues affecting minori

ties and the poor was disseminated. A seven person

staff concentrated on working for the passage of legis

lation on the Legislative Agenda, developing a referral

system for persons seeking assistance, creating a na

tional legislative support network, and strengthening

ties to other Black elected officials.

In 1976 a second legislative agenda was formulated,

concentrating on ten issue areas including Full Em

ployment, Health Care, Urban Revitalization, Civil

and Political Rights and Foreign Affairs.

A staff of eight full time persons provides the legis

lative, research, and information coordination of

Caucus activities. While the staffs of individual Cau

cus Members work on matters concerning their sixteen

congressional districts, the Caucus staff works in sev

eral key areas:

1. Issues of concern to the entire Caucus;

2. Issues which need the collective effort of the

entire Caucus;

3. Issues which have broad impact on Black and

other underrepresented Americans;

4. Issues which members may be better able to

support under the Caucus umbrella than in

their own individual names.

The various members of Congress included in this

Caucus have authored, voted for and encouraged other

members of the Congress to pass legislation sup

portive of the National Government’s policy of af

firmative action using race as a corrective factor. See

Appendix A to the brief for the United States as

amicus curiae.

Because of this special interest as members of the

Black Congressional Caucus and as members of the

Congress of the United States, we wish to reply to the

Brief filed on behalf of the United States as Amicus

Curiae.

The government in its “ Motion To Participate In

Oral Argument” has characterized its arguments in

this case as follows:

“ The brief of the United States in this case pre

sents the issues and arguments in a way that is

significantly different from the approaches taken

by either party. Both of the parties have argued

that the dispositive question is whether race may

be taken into account at all in making admissions

decisions; we have taken the position that it is im

portant how race was used, and for what reasons.

Our brief, unlike the approach of either party, em

phasizes the argument that the use of race is justi

fied in order to redress the lingering effects of so

cietal discrimination. We then argue, again unlike

either party, that the central constitutional ques

tion is whether the program has been tailored to

take race into account in a way consistent with the

requirement of fair treatment of all applicants to

the professional school. We conclude that the judg-

5

ment of the Supreme Court of California should

be reversed in part and vacated in part, so that

the parties may seek to introduce additional evi

dence, consistent with these principles.

Because we have approached the case from a

perspective neither party shares, and because we

have come to conclusions that are different from

those of either party, I believe that an oral pre

sentation of the views of the United States would

be of assistance to the Court.”

As members of the Congressional Black Caucus and

as Members of Congress we wish to reply to the argu

ments of the government as not fully representative

of all of the constitutent branches of government and

in particular not fully representative of our views as

Members of Congress. We welcome certain of the posi

tions advanced in the brief of the United States but

feel that it is necessary to place before the Court sev

eral critical questions raised by certain of the formula

tions and approaches of the brief of the United States.

We take issue with the government’s failure to meet

directly the central question raised in the case: That

the State of California and the University of Califor

nia, Davis Medical School’s use of race in an affirma

tive action program provides an effective remedy to

begin to overcome the past and present discrimination

against and exclusion of minority people from the

profession of medicine, and is constitutional.

We believe that this Court consistent with the man

date of the wartime Amendments to the Constitution

and its own past decisions must forthrightly and with

out reservation support the constitutionality of the af

firmative action remedy of the University of California,

Davis Medical School. The decision of the California

Supreme Court must be reversed and vacated without

any remand which might result in further dilatory

action.

Any vacillation or hesitation by this Court in reaf

firming the fundamental principles at stake in this case

may well sound the deathknell of the progress made

since this Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Edu

cation, 347 TT.S. 483 (1954), in bringing into life the

promises of freedom and equality written into our

fundamental law by the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and

Fifteenth Amendments.

ARGUMENT

I.

The Government's Argument Fails to Comprehend the Full

Intendment of the Civil War Amendments

We are deeply concerned with the government’s fail

ure to understand and articulate before this Court the

full thrust of the Civil W ar Amendments, which im

posed a mandatory obligation on every segment of

American society to utilize effective measures to over

come the incidents of slavery and all of its persisting

badges and indicia. See Jones v. Mayer, 392 U.S. 409

(1968). Surely it is time for the Court to state as di

rectly as it did in Jones that just as the herding of

Black men and women into urban ghettos is a con

tinuing badge and indicia of slavery, so the massive

exclusion of minority people from professions such as

medicine, law, and teaching, and from employment in

industry is also a deeply persisting badge and indicia

of slavery.

7

The Thirteenth Amendment, implemented by the

fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, as this Court

taught in Jones, creates a mandatory duty upon every

section of society to take effective measures to eliminate

these badges and indicia. Affirmative action programs

like the program at issue in this case, are undertaken

to implement this high, historic duty commanded by

the Constitution. They are remedies designed to correct

fundamental constitutional wrongs, which if permitted

to persist threaten the very future existence of the na

tion. See Kerner Report of the National Advisory

Commission On Civil Disorders (1968). This Court

from Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954), 349 U.S. 294 (1955), to United Jewish Orga

nizations of Williamsburgh, Inc. v. Carey, 430 U.S.

144 (March 1, 1977) has recognized that remedies de

signed to eliminate the exclusion of racial minorities

from significant areas of American life are of the high

est constitutional importance. They are not constitu

tionally “ suspect.” They must receive the highest de

gree of protection by this Court or else we will have

embarked on a new period of judicial burial of the 100

years of promises of equality and freedom sadly similar

to the bitter years following the political and judicial

abandonment of the wartime amendments after the

Civil War. Of. the impact of the Civil Rights Cases,

109 U.S. 3 (1883) and Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S.

537 (1896).

The ominous warnings of the first Justice Harlan in

his dissenting opinions which have been so vindicated

by the course of history are once again deeply relevant

to our future. Any weakening of the fundamental im

portance of effective affirmative remedies, as occurred

in the years following the now infamous political be-

8

trayal of 1877, (See generally, C. Vann Woodward, Re

union and Reaction (1951) once again will, as Justice

Harlan so eloquently warned, enflame the fires of a

deeply engrained racism in every level of society and

perpetuate the enforced inferior status of all minority

peoples, endangering the very future of the Nation.

There is not the slightest question that Avithin the

broad sweep of the affirmative power of the wartime

Amendments and the decisions of this Court over the

last decade enforcing that commitment, effective af

firmative action programs, such as the one now before

the Court, are constitutionally mandated and entitled

to the fullest protection of the Court. Contrary to the

suggestion of the government, there is nothing to re

mand for further “ eAudence.” The affirmative action

program here at issue involves the admission of ad

mittedly qualified minority people to meet the admitted

situation of gross exclusion of minority people from

the medical profession. Any suggestion that such a

program may not be constitutional and requires further

“ study” undermines the constitutional goal and com

mand that affirmative measures must be taken to elimi

nate the inferior status of so many of our citizens. In

the record of this case there is not a scintilla of evidence

to suggest that the reservation of 16 places out of 100

for disadvantaged and minority people is in the slight

est degree an unreasonable application of the duty im

posed on the University of California by the Constitu

tion. The “ burden” does not lie on the University to

justify its response to the command of the Constitution.

The burden lies on those who seek to undermine and

destroy the Constitutional mandate to justify their

position. No such burden has been met here and, we

assert the Constitution does not tolerate such an argu-

9

mo,nt. Just as Mr. Justice Black once reminded us in

respect to the F irst Amendment, all balancing was

done when the Thirteen Amendment was enacted. The

Nation then promised to take all necessary measures,

whatever the cost, to carry through the commitment to

enforce the “universal charter of freedom” (cf. the

Civil Rights Cases, supra), which the Amendment

ordained.

I t took almost 75 years for this Court in Brown v.

Board of Education, supra, to begin to undo the judi

cial burial of the Wartime Amendments. I t would be a

national disaster on a most ominous level for this Court

to in any way retreat from the commitment stated in

Brown-said restated so powerfully in Jones v. Mayer,

supra to breathe life into the promises of freedom and

equality embodied in the Wartime Amendments.

II.

The Government's Qualifications on the Use of Race Has No

Constitutional, Legal or Rational Basis

The government agrees that race may be taken into

account to remedy the effects of societal discrimina

tion. The government would qualify the mandate of

the several Civil W ar Amendments, the decisions of

this Court and the present national policy by placing

Limitation on the use of race first conceived here by

the government. The use of race would become a null

ity by the device of the general rule and exceptions

which eventually destroy the effectiveness of the rule.

Judge Lummus of the Supreme Judicial Court of

Massachusetts observed this process in another field

of law:

“The MacPherson case caused the exception to

swallow the asserted general ride of non-liability

10

leaving nothing upon which that rule could op

erate.” Carter v. Yardleiy & Co., 319 Mass. 92, 64

N.E. 2d 693 (1946).

In the government’s view this case presents complex

questions concerning the manner in which race prop

erly may be taken into account. The government’s pro

posed test would raise such questions a s : W hat use may

be made of race? When is its use legitimate? What

constraints exist on the authority of states to make

color-conscious decisions? When has a State over

stepped permissible bounds? The government’s posi

tion poses a balancing test between the individual

rights of the persons denied admission and the rights

of blacks and other minorities as groups. Under the

government’s qualifications race may be a legitimate

tool of decision-making only when race has importance.

The government would justify the use of race to over

come handicaps that may have been caused by race. Any

other use would be impermissible. Race may he used

to make competition more effective, but not to prevent

competition between majority and minority applicants.

These qualifications on the use of race make a mock

ery of the government’s position affirming the use of

race.

Realistically no program could be fashioned and ad

ministered within these restrictions. These programs

would fall into an administrative quagmire. Those

surviving would be subject to endless litigation as to

the proper qualifying conditions on the use of race.

The command of the Constitution and the decisions

of this Court place no such qualifications on the use of

race as the government here suggests. The color-con-

11

scions cases from Swann v. Charolotte-MecMenlmrg

Hoard of Education, 402 U.S. 1 (.1971) to United Jew

ish Organization of Williamsburgk, Inc. v. Carey, 430

U.S. 144 (1977), erect no such qualifications. Race may

be used to remedy the effects of past and present racial

discrimination. This approach has been taken by this

Court to vindicate the rights of the individual members

of the group which have been discriminated against.

These individuals had personal and immediate rights

to vindication until the government in 1955 trans

planted into the field of civil rights jurisprudence the

concept of “ all deliberate speed.” To talk now in terms

of balancing the interest of the individuals of the ma

jority group that may be affected by granting rights to

individual members of excluded groups is legal legerdo-

main. It. appears to give that which it in fact withholds.

The constitutional mandate to overcome the status of

inferiority and exclusion imposed upon minority peo

ples cannot be balanced against the possible impact of

these reasonable measures on random individuals who

are not members of excluded groups. The only permis

sible inquiry is whether the program involved carries

out the constitutional mandate of removing the status

of inferiority and exclusion. This is an objective of the

highest national importance and no considerations of

possible impact upon individuals who are not members

of an excluded group are relevant to the constitutional

permissibility of reasonable measures adopted to meet

the constitutional command. There is no balancing to

be done.

12

III.

We Take Issue With the Government's Conclusion

That the Case Should Be Remanded

The reasons asserted by the government for a remand

are groundless. The government suggests a remand to

establish a record to explore the presence or non-pres

ence of qualifications on the use of race in order to

engage in a balancing process which we have just

pointed out is impermissible under the Constitution.

The government’s contribution of the balancing test

may well be, if adopted, the present day counterpart

of “ separate-but-equal” or “ all deliberate speed.”

That would require a minimum of another generation

to undo the shackles which such a “ balancing test”

would then place on the implementation of the consti

tutional promise of equality and freedom.

Furthermore, the wholly unnecessary delay which

the suggestion of remand would involve, would danger

ously stimulate the dismantling of the many existing

affirmative action programs in the private and public

sectors. I t would, in a manner completely unwarranted

by the Constitution, raise a suggestion of possible in

validity in respect to every existing effective program.

It would encourage the drowning of affirmative action

in an ocean of litigation. The clear mandate of the

Constitution requires a firm and decisive stand by this

Court sustaining for all to hear the constitutionality

of effective, meaningful affirmative action measures.

The Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amend

ments demand no less.

13

CONCLUSION

As Members of the Congress, with a strong commit

ment to the Black constituency, we feel impelled to

urge upon this Court the urgency and the necessity for

a strong forthright statement in support of the na

tional commitment to affirmative action to bring to full

fruition the intendment of the landmark decision of

this Court in Brown v. Board of Education, supra.

The future health and welfare of this nation, both

domestically and internationally dictate that there

must be no judicial retreat on the constitutional man

date that equality and freedom must be meaningful

concepts for all the people of our country.

Respectfully submitted,

H erbert O. R eid, Sr.

Howard University

School of Law

2935 Upton Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20008

A r t h u r K inoy

Rutgers Uni versify

School of Law

180 University Avenue

Newark, New Jersey 07102

Attorneys for the Amici Curiae

Members of the Congressional

Black Caucus, Members of the

Congress of the United. States.