Hardback 7 Inventory Jul 1983 - Dec 1983

Working File

July 19, 1983

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Hardbacks, Briefs, and Trial Transcript. Hardback 7 Inventory Jul 1983 - Dec 1983, 1983. e4c30a45-d492-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1dc97e7e-c1a6-4913-87f9-791080cdd164/hardback-7-inventory-jul-1983-dec-1983. Accessed March 02, 2026.

Copied!

7 /te/83

7 /te/83

7 /2L/83

8/2/8s

8/ 4/ 83

8/30/83

e/2/8s

7 /23/83

7 /22/83

7 /26/83

L0/7 /83

t0/7 /83

to / 24/ 83

L0 /24/83

e /23/83

't 7/21/83

L0/24/83

tz ls 83

rt/t2/ 83

t2/7 / 83

I I

oo

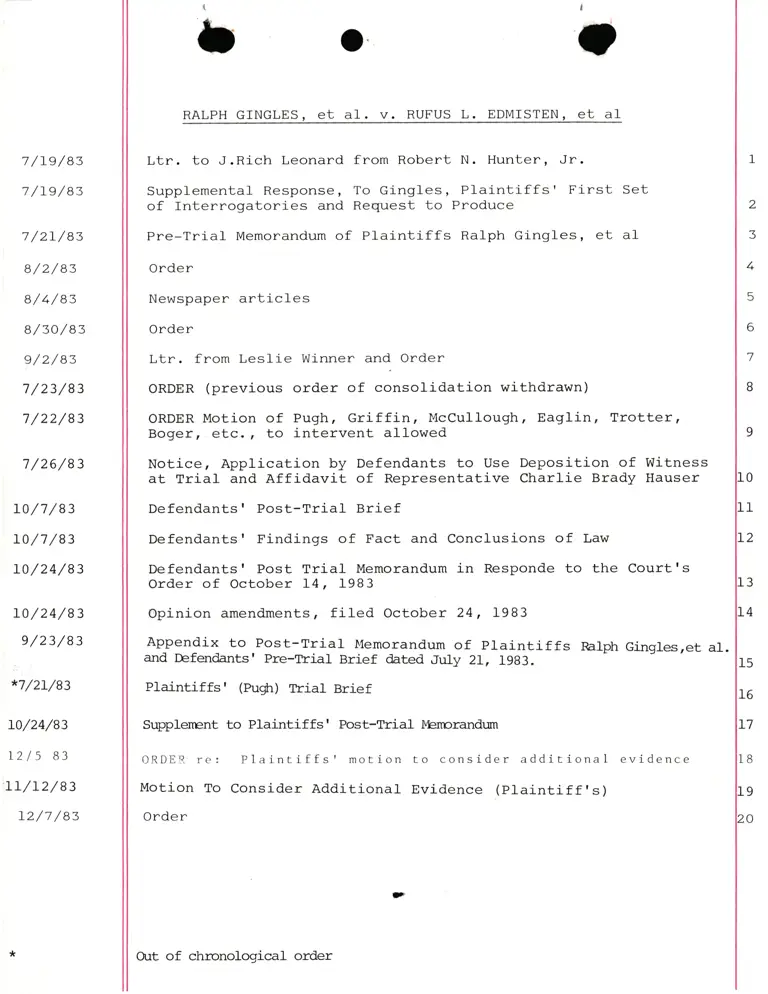

RALPH GINGLES, et aI v. RUFUS L. EDMISTEN, €t al

Ltr. to J.Rich Leonard from Robert N. Hunter, Jr.

Supplemental Response, To Gingles, Plaintiffs' First Set

of Interrogatories and Request to Produce

Pre-Trj-aI Memorandum of Plaintiffs Ra1ph Gingles, €t aI

Order

Newspaper articles

Order

Ltr. from LesIie Winner and. Order

ORDER (previous order of consolidation withdrawn)

ORDER Motion of Pugh, Griffin, McCullough, Eaglin, Trotter,

Bogerr €tc., to intervent allowed

Notice, Application by Defendants to Use Deposition of Witness

at Trial and Affidavit of Representative Charlj-e Brady Hauser

Defendantsr Post-Trial Brief

Defendants' Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law

Defendants' Post Trial Memorandum in Responde to the Courtrs

Order of October 14, 1983

Opinion amendments, filed October 24, 1983

Appendix to Post-Trial l4emorandum of Plaintiffs Ralph Ginglesret a1.

and Defendantsr Pre-Ilrial Brief dated July 21, 1983.

Plaintj-ffsr (zugLrl Itial Brief

Supplenent

OllDE!. re:

Motion To

Order

to Plaintiffs' Post-Trial l,bnprandun

Plaintiffst motion to consider additional evidence

Consider Additional Evidence (plaintiff 's)

O:t of chronological order

1

2

J

4

5

6

7

I

9

t0

t1

L2

I3

L4

15

16

t7

18

I9

20