Appendices A Through H Inclusive - Volume II

Public Court Documents

1969

86 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Alexander v. Holmes Hardbacks. Appendices A Through H Inclusive - Volume II, 1969. 90bd1d3c-cf67-f011-bec2-6045bdffa665. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1df2315b-aaee-435f-854a-2684147e13e8/appendices-a-through-h-inclusive-volume-ii. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

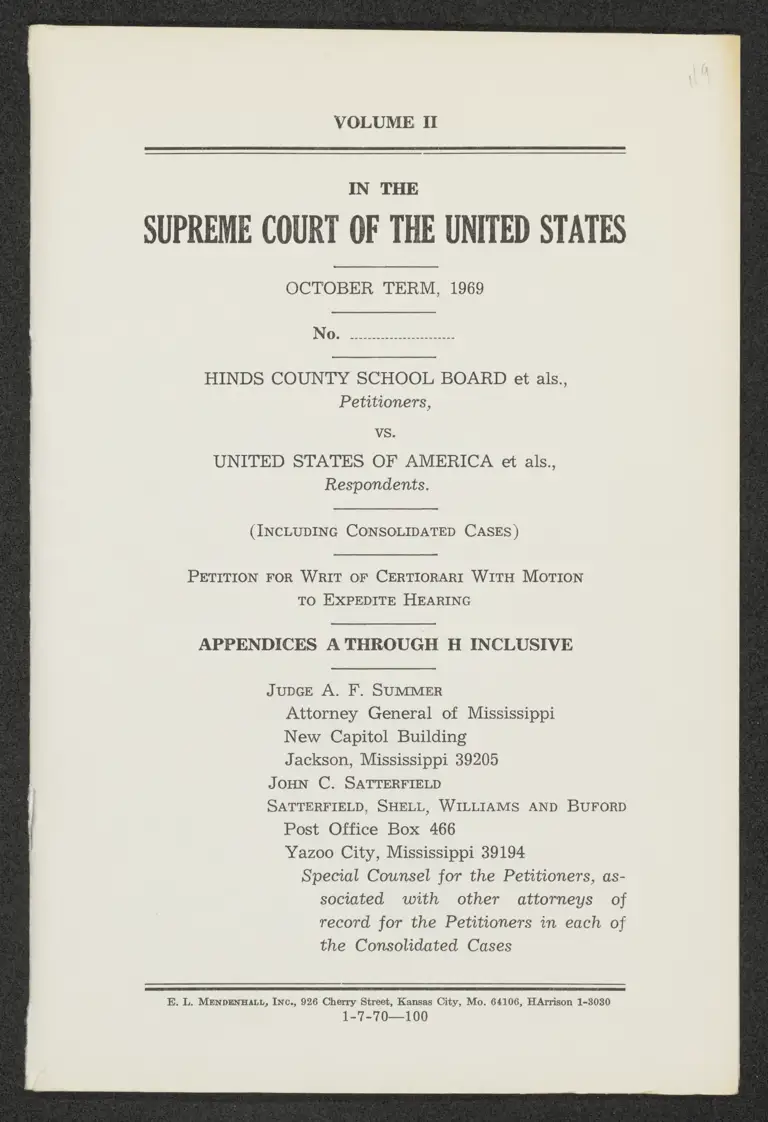

VOLUME II

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1969

HINDS COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD et als,,

Petitioners,

VS.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA et als,

Respondents.

(IncLUDING CONSOLIDATED CASES)

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI WITH MOTION

TO EXPEDITE HEARING

APPENDICES A THROUGH H INCLUSIVE

JUDGE A. F. SUMMER

Attorney General of Mississippi

New Capitol Building

Jackson, Mississippi 39205

JOHN C. SATTERFIELD

SATTERFIELD, SHELL, WILLIAMS AND BUFORD

Post Office Box 466

Yazoo City, Mississippi 39194

Special Counsel for the Petitioners, as-

sociated with other attorneys of

record for the Petitioners in each of

the Consolidated Cases

E. L. MENDENHALL, INC., 926 Cherry Street, Kansas City, Mo. 64106, HArrison 1-3030

1-7-70—100

INDEX

Volume II

Appendix A—

Opinion of the Court of Appeals of July 3, 1969 ........ Al

Modification of Order of the Court of Appeals of July

ER 1 ER ee hE ee Sen Al10

Letter Directive of the Court of Appeals of June 25,

1869 he Al2

Appendix B—

Order of Court of Appeals of November 7, 1969 ........ Al6

Appendix C—

Opinion and Judgment of United States Supreme

Court of October 29, 1988 . ..........coeciessrniricninaneis A23

Appendix D—

Order of Court of Appeals of October 31, 1969 ............ A25

Appendix E—

Order of Court of Appeals of December 1, 1969 ........ A27

Appendix F—

Proceedings of Pre-Order Conference ......................... A46

Appendix G—

Letter of November 4, 1969 re Proposed Order ........ A58

Proposed Oder... eee ee A60

Appendix H—

Opinion of the District Court Approving Freedom of

CHOICE PIONS cs riser cs ciara nies A63

Al

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1969

HINDS COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD et als.

Petitioners,

VS.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA et als.,

Respondents.

(IncLupING CONSOLIDATED CASES)

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI WITH MOTION

TO EXPEDITE HEARING

APPENDIX A

Opinion of the Court of Appeals of July 3, 1969

[Caption omitted]

Before

Brown, Chief Judge,

THORNBERRY and MORGAN, Circuit Judges.

PER CURIAM:

As questions of time present such urgency as we ap-

proach the beginning of the new school year September

A2

1969-70, the court requested in advance of argument that

the parties submit proposed opinion-orders modeled after

some of our recent school desegregation cases. We have

drawn freely upon these proposed opinion-orders.

These are twenty-five school desegregation cases in

a consolidated appeal from an en banc decision of the U. S.

District Court for the Southern District of Mississippi.

These cases present a common issue: whether the District

Court erred in approving the continued use by these school

districts of freedom of choice plans as a method for the

disestablishment of the dual school systems.

The plaintiffs’ position is that the District Court erred

in failing to apply the principles announced in recent deci-

sions of the Supreme Court and of this Court.

These same school districts, along with others, were

before this Court last year in Adams v. Mathews, 403 F.2d

181 (5th Cir., 1968). The cases were there remanded with

instructions that the district courts determine:

(1) whether the school board’s existing plan of de-

segregation is adequate “to convert [the dual system]

to a unitary system in which racial discrimination

would be eliminated root and branch” and (2) whether

the proposed changes will result in a desegregation

plan that “promises realistically to work now.”

403 F.2d at 188. In determining whether freedom of choice

would be acceptable, the following standards were to be

applied:

If in a school district there are still all-Negro

schools or only a small fraction of Negroes enrolled in

white schools, or no substantial integration of facul-

ties and school activities then, as a matter of law, the

existing plan fails to meet constitutional standards as

established in Green.

A3

Ibid.

In all pertinent respects, the facts in these cases are

similar. No white student has ever attended any tradi-

tionally Negro school in any of the school districts. Every

district thus continues to operate and maintain its all-

Negro schools. The record compels the conclusion that to

eliminate the dual character of these schools alternative

methods of desegregation must be employed which would

include such methods as zoning and pairing.

Not only has there been no cross-over of white stu-

dents to Negro schools, but only a small fraction of Negro

students have enrolled in the white schools.! The highest

1. Illustrative are the following tables, corrected to the latest

available data furnished and checked by counsel, in the cases in

which the Government is a party showing the racial character of

the schools in each district and the enrollment by race:

RACIAL CHARACTER

Predom-

Total Number All- All- nantly

District of Schools Negro White White

Amite 1

Canton

Columbia

Covington

Forrest

Franklin

Hinds

Kemper

Lauderdale

Lawrence

Leake

Lincoln

Madison

Marion

Meridian

Natchez-Adams

Neshoba

North Pike

Noxubee

Philadelphia

Sharkey-Issaquena

Anguilla-Line

South Pike

Wilkinson

Ww

W

nN

N

O

W

W

N

DN

DN

pt

BR

-

g

W

U

I

W

w

W

O

BR

N

O

U

I

O

U

I

O

I

J

=

J

U

u

I

U

I

N

W

O

a

u

n

fa

BO

DO

DN

fs

pd

QO

i

bt

oJ

00

bt

1

IN

D

C

O

D

D

=

DN

)

©

=

=

QU)

be

d

[S

S

|

=

r

o

r

o

n

o

pt

pd

DN

C1

bt

pd

pd

CO

B=

=

00

D

N

HD

1

2

1

1

2

3

3

3

2

2

}

Ad

percentage is in the Enterprise Consolidated School Dis-

trict, which has 16 percent of its Negro students enrolled

in white schools—a degree of desegregation held to be in-

adequate in Green v. County School Board, 391 U. S. 430

(1968). The statistics in the remaining districts range

from a high of 10.6 percent in Forrest County to a low of

0.0 percent in Neshoba and Lincoln Counties. For the most

part school activities also continue to be segregated. Al-

though Negroes attending predominantly white schoools do

participate on teams of such schools in athletic contests,

in none of the districts do white and all-Negro schools

compete in athletics.

These facts indicate that these cases fall squarely

within the decisions of the Supreme Court in Green and

ENROLLMENT BY RACE AND PERCENTAGE

OF NEGROES IN WHITE SCHOOLS

1968-1969 Enrollment Negroes in White Schools

District Negro White Number Percentage

Amite 2,649 1,484 63 2.4 9

Canton 3,440 1,352 4 11¢

Columbia 912 1,553 60 6.6 9%

Covington 1,422 1,968 89 5.1:

Forrest 480 3,085 81 16.9 9%

Franklin 1,029 1,124 38 3.7 6,

Hinds 7,409 6,559 481 6.5 %

Kemper 1,896 786 11 .589

Lauderdale 1,872 3,060 26 1.4 9

Lawrence 1,263 1,889 32 2.5 9,

Leake 1,568 1,950 67 4.3 9

Lincoln 941 1,149 5 2 0

Madison 3,198 1,128 41 1.3 o;

Marion 1,082 1,741 34 3.1

Meridian 3,974 5,805 606 15.2 9,

Natchez-Adams 5,509 4,496 541 9.8 9

Neshoba 591 1,875 1 169%

North Pike 632 708 2 319

Noxubee 3,002 829 95 3.2 %

Philadelphia 406 923 11 2.7 9%

Sharkey-Issaquena 1,241 603 104 6.4 9%

Anguilla-Line 769 207 30 3.9 9%

South Pike 1,737 994 46* 2.6

Wilkinson 2,032 689 55 2.7 o;

Note: There is a disagreement over proper accounting for some

special classes which, for these purposes, we consider un-

important.

Ab

its companion cases and the decisions of this Court. See

United States v. Greenwood Municipal Separate School

District, 406 F.2d 1086 (5th Cir. 1969); Henry v. Clorks-

dale Municipal Separate School District, No. 23255 (5th

Cir., March 6, 1969); United States v. Indianola Municipal

Separate School District, No. 25,655 (5th Cir, April 11,

1969); Anthony v. Marshall County Board of Education,

No. 26,432. (5th Cir., April. 15, 1969); Hall v. St. Helena

Parish School Board, No. 26,450 (5th Cir., May 28, 1969);

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile County,

No. 26,886 (5th Cir., June 3, 1969); United States v. Jef-

ferson County Board of Education, No. 27,444 (5th Cir.,

June 26, 1969); United States v. Choctaw County Board of

Education, 5 Cir. 1969, F.2d (No. 27.207, July 1,

1969); United States v. The Board of Education of Baldwin

County, 5 Cir. 1969, 7.24 (No. 27,281, July 1, 1969);

United States v. The Board of Education of the City of

Bessemer, 5 Cir. 1969, F.2d (Nos. 26,582; 26,583;

26,584; July 1, 1969). The proper conclusion to be drawn

from these facts is clear from the mandate of Adams v.

Mathews, supra: ‘as a matter of law, the existing plan

fails to meet constitutional standards as established in

Green.”

We hold that these school districts will no longer be

able to rely on freedom of choice as the method for dises-

tablishing their dual school systems.

This may mean that the tasks for the courts will be-

come more difficult. The District Court itself has stated

that it “does not possess any of the training or skill or ex-

perience or facilities to operate any kind of schools; and

unhesitatingly admits to its utter incompetence to exercise

or exert any helpful power or authority in that area.”

And this Court has observed that judges “are not edu-

Ab

cators or school administrators.” United States v. Jeffer-

son County Board of Education, supra at 855. Accordingly,

we deem it appropriate for the Court to require these

school boards to enlist the assistance of experts in edu-

cation as well as desegregation; and to require the school

boards to cooperate with them in the disestablishment of

their dual school systems.

With respect to faculty desegregation, little progress

has been made.? Although Natchez-Municipal Separate

District has a level of 19.2% and Lawrence County a level

of 10.6%, seven school districts have less than one full-

time teacher per school assigned across racial lines. In the

remaining systems, fewer than 10 percent of the full-time

faculties teach in schools in which their race is in the

minority. Faculties must be integrated. United States

v. Montgomery County Board of Education, No. 798, at 8

2. The latest corrected figures (see Note 1 supra) are:

Full & Part Full time desegre- Part time desegre-

time teachers gating teachers gating teac

District Negro White Negro White Negro

Amite 95 66 0 0 0

Canton 120 21 3 i 1

Columbia 43 71 5 4 0

Covington 64 103 3 3 1

Forrest 43 122 4 S 1]

Franklin Ai 45 3 4 1

Hinds 295 281.9 29 0

Kemper 68 45 0 1 0

Lauderdale 82 131 8 3 0

Lawrence 50 81 10 4 0

Leake 87 90 0 3 0

Lincoln 38 74 0 0 0

Madison 147 66 0 8 0

Marion 438 96 4 6 0

Meridian 180 317 8 17 4

Natchez-Adams 484 0 0 0

Neshoba 35 86 0 3 0

North Pike 26 30 1 2 1

Noxubee 135 61 6 1 0

Philadelphia 25 46 0 0 0

Sharkey-Issaquena 71 31 0 0 0

Anguilla-Line 0 0 0

South Pike 78 52.8 2 3.3 0

Wilkinson 97 39 0 6 0

hers

White

H

N

O

O

O

[

S

W

O

C

N

O

O

N

O

N

N

W

O

O

H

H

O

M

E

H

E

O

W

AT

(Sup.Ct., June 2, 1969). Minimum standards should be

established for making substantial progress toward this

goal in 1969 and finishing the job by 1970. United States

v. Board of Education of the City of Bessemer, 5 Cir.,

1968, 396 F.2d 44; Choctaw County, supra, Baldwin County,

supra.

The Court on the motion to summarily reverse or al-

ternatively to expedite submission of the case filed by the

Government and the private plaintiffs concluded that

fundamental constitutional rights of many persons would

be jeopardized, if not lost, if this Court routinely calen-

dared this case for briefing and argument in the regular

course. Before we could ever hear it, the opening of the

school year September 1969-1970 would have gone by.

With this and the total absence of any new issue even

resembling a constitutional issue in this much litigated field,

we therefore concluded that the appeals should be ex-

pedited. Full arguments were had and representatives

from every District were heard from. In the course of

these arguments, several contentions were made as to

which we make these additional specific comments.

Based upon opinion surveys conducted by presumably

competent sampling experts, testimony of school admin-

istrators, board members, and educational experts, the

School Districts urged, and the District Court found in

effect, that the failure of a single white student to attend

an all-Negro school was due to the provisions of our Jej-

ferson decree which in effect prohibited school authorities

from influencing the exercise of choice by students or

parents. We find this completely unsupported. This

record affords no basis for any expectation of any sub-

stantial change were the provision modified.

Based upon similar testimony, the School Districts

urged a related contention that the uncontradicted statistics

AS

showing only slight integration are not a reliable indicator

of the commands of Green. This argument rests on the

assertion that quite apart from a prior dual race school

system, there would be concentration of Negroes or white

persons from what was described as “polarization.” To

bolster this, they pointed to school statistics in non-southern

communities. Statistics are not, of course, the whole an-

swer, but nothing is as emphatic as zero, and in the face

of slight numbers and low percentages of Negroes attend-

ing white schools, and no whites attending Negro schools,

we find this argument unimpressive.

In the same vein is the contention similarly based on

surveys and opinion testimony of educators that on stated

percentages (e.g., 20%, 30%, 70%, etc.), integration of Ne-

groes (either from influx of Negroes into white schools or

whites into Negro schools), there will be an exodus of

white students up to the point of almost 100% Negro

schools. This, like community response or hostility or

scholastic achievement disparities, is but a repetition of

contentions long since rejected in Cooper v. Aaron, 1958,

2553. U.8.1,........ BC cinsnes fon 1.04. ....... ; Stell v. Savan-

nah-Chatham County Bd. of Ed., 5 Cir., 1964, 333 F.2d 55,

61; and United States v. Jefferson County Bd. of Ed., 5 Cir.

1969, ....... Rod... [No. 27444, June 26, 1969].

The order of the District Court in each case is reversed

and the cases are remanded to the District Court with the

following direction:

1. These cases shall receive the highest priority.

2. The District Court shall forthwith request that edu-

cators from the Office of Education of the United States

Department of Health, Education and Welfare collaborate

with the defendant school boards in the preparation of

plans to disestablish the dual school systems in question.

A9

The disestablishment plans shall be directed to student and

faculty assignment, school bus routes if transportation is

provided, all facilities, all athletic and other school activi-

ties, and all school location and construction activities. The

District Court shall further require the school boards to

make available to the Office of Education or its designees

all requested information relating to the operation of the

school systems.

3. The board, in conjunction with the Office of Edu-

cation, shall develop and present to the District Court

before August 11, 1969, an acceptable plan of desegregation.

4, If the Office of Education and a school board agree

upon a plan of desegregation, it shall be presented to the

District Court on or before August 11, 1969. The court shall

approve such plan for implementation commencing with

the 1969 school year, unless within seven days after sub-

mission to the court any party files any objection or pro-

posed amendment thereto alleging that the plan, or any

part thereof, does not conform to constitutional standards.

5. If no agreement is reached, the Office of Education

shall present its proposal to the District Court on or before

August 11, 1969. The Court shall approve such plan for

implementation commencing with the 1969 school year, un-

less within seven days a party makes proper showing that

the plan or any part thereof does not conform to constitu-

tional standards.

6. For plans to which objections are made or amend-

ments suggested, or which in any event the District Court

will not approve without a hearing, the District Court shall

hold hearings within five days after the time for filing ob-

jections and proposed amendments has expired. In no

event later than August 21, 1969.

7. The plans shall be completed, approved, and

ordered for implementation by the District Court no later

Al0

than August 25, 1969. Such a plan shall be implemented

commencing with the beginning of the 1969-1970 school

year.

8. Because of the urgency of formulating and approv-

ing plans to be implemented for the 1969-70 school term it

is ordered as follows: The mandate of this Court shall

issue immediately and will not be stayed pending petitions

for rehearing or certiorari. This Court will not extend the

time for filing petitions for rehearing or briefs in support

of or in opposition thereto. Any appeals from orders or

decrees of the District Court on remand shall be expedited.

The record on any appeal shall be lodged with this court

and appellants’ brief filed, all within ten days of the date

of the order or decree of the district court from which the

appeal is taken. Appellee’s brief shall be due ten days

thereafter. The court will determine the time and place for

oral argument if allowed. The court will determine the

time for briefing and for oral argument if allowed. No

consideration will be given to the fact of interrupting the

school year in the event further relief is indicated.

REVERSED AND REMANDED WITH DIRECTIONS

Modification of Order of the Court of Appeals

of July 25, 1969

[Caption omitted]

Before

Brown, Chief Judge,

THORNBERRY and MorcAN, Circuit Judges.

Per Curiam:

The opinion published in the above styled cases on

July 3, 1969 is hereby modified by renumbering former

paragraph 8 to be number 7 and striking from such order,

on pages 17 and 18, paragraphs 5, 6 and 7 in their entirety,

All

and inserting in lieu thereof new paragraphs 5 and 6 which

shall read as follows:

9. If no agreement is reached, the Office of Education

shall present its proposal for a plan for the school

district to the district court on or before August 11,

1969. The parties shall have ten (10) days from the

date such a proposed plan is filed with the district

court to file objections or suggested amendments

thereto. The district court shall hold a hearing on

the proposed plan and any objections and suggested

amendments thereto, and shall enter a plan which

conforms to constitutional standards no later than

ten (10) days after the time for filing objections has

expired.

6. A plan for the school district shall be entered for

implementation by the district court no later than

September 1, 1969 and shall be effective for the be-

ginning of the 1969-1970 school year. The district

court shall enter Findings of Fact and Conclusions

of Law regarding the efficacy of any plan which is

approved or ordered to immediately disestablish the

dual school system in question. Jurisdiction shall

be retained, however, under the teaching of Green

v. County School Board of New Kent County, 391

U. S. 430, 439 (1968), and Raney v. Board of Educa-

tion of Gould School District, 391 U.S. 443, 449

(1968), until it is clear that disestablishment has

been achieved.

Al2

Letter Directive of the Court of Appeals

of June 25, 1969

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

Fira CircuIlr

Orrick oF THE CLERK

EpwArD W. WADSWORTH Room 408-400 RovAaL ST.

CLERK NEw ORLEANS, La. 70130

June 25, 1969

To CouNseL LiSTED BELOW

Nos. 28030 and 28042

United States v. Hinds County School Board, et al.

Gentlemen:

I am directed by the Court to forward the following

instructions regarding the 25 consolidated Mississippi

school cases (U.S. v. Hinds County School Board, et al.):

1. The Court will hear oral argument on all of these

cases on the motion for summary reversal and the merits

in all of the cases both private plaintiffs and those of the

United States. The argument will be held in New Orleans

beginning 9:30 A.M., Wednesday, July 2. Counsel should

hold themselves in availability for Thursday, July 3, as

well. The parties will work out amongst themselves a

suitable proposed schedule of orders and probable times.

The Court does not put any specific limitation on time but

of course desires no unnecessary repetition.

2. The United States is to arrange for a court re-

porter, the cost to be charged as costs in the case.

3. The parties are free to file in typewritten form,

with xerox copies or similar reproduction, any additional

Al3

memoranda or briefs and it would be helpful if copies are

simultaneously sent both to the Clerk and to the Judges

at their home stations. Special effort should be made to

have any memoranda, responses, etc. in the Clerk’s office

by Noon, Tuesday, July 1. Responses and rejoinders will

be permitted as desired.

4. The District Clerk is to furnish, and the U. S.

Department of Justice is to procure and have available in

the courtroom for use by the Judges on the bench, with

respect to each school district involved, copies of the latest

statistical report required to be filed with the District

Court under the Jefferson type decree theretofore entered.

Counsel are also directed to supply hopefully in a mutually

agreeable way a consolidated recap which sets out the

statistical data substantially in the format of the Exhibit

“J” attached to the motion of the private plaintiffs-appel-

lants covering each of the Boards of Education. If desired,

these tables may be adapted to show relative percentages

of all pertinent items including those set forth in Exhibits

A through D attached to the response to motion for sum-

mary reversal filed June 20 by Messrs. Bridforth and

Satterfield.

5. The Court takes notice of Judge Cox’s order with

respect to the record but since the appeal is being ex-

pedited on the original record without reproduction re-

quired or permitted, the U. S. Attorney shall make ar-

rangements with the District Clerk to transmit to the

Clerk of the Court of Appeals the entire record of the

District Court including the transcript of the evidence in

all of the cases so that it will be available to the Court

as needed during argument and submission. The Court

contemplates, however, that the record may be returned

in a very short time. If the District Clerk prefers, it would

be quite in order for him, one of his deputies, or the U.S.

Al4

Attorney to transport and deliver the record to the Clerk

of the Court of Appeals.

6. The Court’s general approach will be to accept the

fact findings of the District Court and to determine what,

if any, legal relief is now required best thereon. To the

extent that appellants, private or government, assert that

any one or more specific fact findings (as distinguished

from mixed questions of law and fact) are clearly er-

roneous, the appellants concerned shall xerox copies of

pertinent excerpts of the transcript of the evidence for

use by the Judges (4 copies) which may be made available

during argument.

7. To enable the Court to announce a decision as

quickly as possible after submission, the appellants are re-

quested to file in 15 copies a proposed opinion-order with

definitive time table and provisions on the hypothesis that

the appeal will be sustained. These should be modeled

somewhat on the form used by the Court in its recent opin-

ions in Hall, et al. v. St. Helena Parish School Board, et al.,

No. 26450, May 28, 1969, and Davis, et al. v. Board of School

Commissioners of Mobile County, et al., No. 26886, June 3,

1969. When and as additional opinion-orders of this type

are issued in other school desegregation cases, copies will

be immediately transmitted to all counsel so that the parties

can make appropriate comments during argument with

respect to suggested modifications or changes in their pro-

posed opinion-orders.

The Court hopes that the appellants, private and gov-

ernment, can collaborate and submit a mutually agreeable

proposed opinion-order and it desires from the appellees

contrary proposed orders covering separately (a) on the

hypothesis that the decrees of the District Court will be

affirmed, and (b) on the hypothesis that the appellants’

motion and appeals will be sustained for reversal.

Al5

8. The Court recognizes that this is a huge record in-

volving a large number of parties and matters of great

public interest and importance. Everyone will be heard

but the Court also expects the distinguished counsel who

appear in this case to collaborate in the best traditions of

the bar to the end that waste of time and effort is elim-

inated and repetition avoided as much as possible. The

Clerk will stand ready to be of whatever assistance he can

in meeting this very compressed time schedule.

Very truly yours,

EpwArRD W. WADSWORTH,

Clerk

By /s/ GILBERT F. GANUCHEAU

Gilbert F. Ganucheau

Chief Deputy Clerk

GFG:adg

cc: (See attached list)

Al6

APPENDIX B

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 28,030 and 28,042

(Civil Action No. 4075(J))

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

V.

HINDS COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD, et al,

Defendants-Appellees.

(AND ALL OTHER CONSOLIDATED CASES)

APPEALS FROM THE UNITED STATES DisTRicT COURT FOR THE

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF MISSISSIPPI

Before BELL, THORNBERRY, and MORGAN, Circuit

Judges.

PER CURIAM:

These cases, consolidated for order, are here for dis-

position in light of the decision of the Supreme Court in

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, No. 632,

dated October 29, 1969. They involve 30 school districts

in the Southern District of Mississippi. Suits to disestab-

lish the dual school system were brought against fourteen

of the school districts by private litigants: Anguilla, Can-

ton, Enterprise, Holly Bluff, Holmes, Leake, Madison,

Meridian, North Pike, Quitman, Sharkey-Issaquena, Wil-

kinson, Yazoo City, and Yazoo County. The suits with re-

spect to the other sixteen school districts were government

initiated.

Al7

The scope of the problem of converting from dual to

unitary school systems in these districts may be seen from

the following tables which reflect racial composition.

GROUP 1

System White Students Negro Students

Amite 1461 2582

Anguilla Line 214 906

Canton Municipal 1326 3672

Hinds 6438 7489

Holly Bluff 240 483

Holmes 913 5355

Kemper 793 2060

Madison 1238 3376

Natchez-Adams 4494 5927

Noxubee County 872 3573

Sharkey-Issaquena 630 2002

South Pike 1135 2156

Wilkinson 779 2757

Yazoo County 1071 2495

GROUP II

System White Students Negro Students

Enterprise 405 363

Franklin 1094 1075

Leake 2088 2224

North Pike 697 605

Quitman 1656 1490

Yazoo City 2014 2089

AlS8

CROUP 11

System White Students Negro Students

Columbia City 1538 896

Covington 1998 1629

Forrest 4195 1062

Lauderdale 3063 1858

Lawrence 1942 1277

Lincoln 1671 1018

Marion 2064 1564

Meridian 6418 4405

Neshoba 2045 877

Philadelphia 969 548

It is ordered, adjudged and decreed, effective im-

mediately, that “the school districts here involved may no

longer operate a dual system based on race or color” and

each district is to operate henceforth, pursuant to the

terms hereof, as a unitary school system within which no

person is “effectively excluded from any school because

of race or color.” Alexander v. Holmes County Board of

Education, supra.

To effectuate the conversion of these school systems

to unitary school systems within the context of the order

of the Supreme Court in Alexander v. Holmes County

Board of Education, it is ordered, adjudged, and decreed

that the permanent plans as distinguished from the interim

plans prepared by the Office of Education, Department of

Health, Education and Welfare, attached hereto and

marked as Appendices 1 through 30 shall be immediately

enforced as the plans of the respective systems subject to

the following terms, conditions, and exceptions:

(1) The time between the date hereof and December

31, 1969 shall be utilized in arranging the transfer of faculty,

Al9

transfer of equipment, supplies and libraries where neces-

sary, the reconstitution of school bus routes where indi-

cated, and in solving other logistical problems which may

ensue in effectuating the attached plans. This activity

shall commence immediately. The Office of Education

plans will result in the transfer of thousands of school chil-

dren and hundreds of faculty members to new schools.

Many children will have new teachers after December 31,

1969. It will be necessary for final grades to be entered and

for other records to be completed by faculty members and

school administrators for the students for the partial school

year involved prior to the transfers. The interim period

between the date of this order and December 31, 1969 will

also be utilized for this purpose.

(2) No later than December 31, 1969 the pupil at-

tendance patterns and faculty assignments in each district

shall comply with the respective plans.

(3) As to the South Pike school district (App. 1),

the plan suggested by the Office of Education shall be

fully complied with except as to pupil assignment. The

present pupil assignment and attendance pattern will suf-

fice until the further order of this court. This system has

1135 white students and 2156 Negro students. Each of its

seven schools are presently integrated. We conclude that

a unitary system has been established as to pupil assign-

ment. The Office of Education plan in other respects will

assure a completely unitary system.

(4) As to the Madison County system, the Office of

Education plan (App. 2) is modified as follows: Subsec-

tions 4 through 8 of the Office of Education Recommended

Plan for Student Desegregation 1969-70 are eliminated. In

place of those subsections we substitute the geographic zon-

ing arrangement for East Flora, Flora, Rosa Scott, Madi-

son-Ridgeland, and Ridgeland Elementary set out in sec-

A20

tions A.2. and A.3. (App. 2(b)) of the proposed plan of the

Madison County Board of Education. All other provisions

of the Office of Education plan regarding Madison County

are to become effective pursuant to the terms of this order.

(5) The attendance plan submitted by the Wilkinson

County Board of Education will be considered by the court

as a modification of the Office of Education plan (App. 3)

upon a showing through a pupil locator map of the contem-

plated racial characteristics of the schools for girls.

(6) The attendance plan submitted by the North

Pike County Consolidated School District will be consid-

ered by the court as a modification of the Office of Educa-

tion plan (App. 4) upon a showing through a pupil locator

map of the contemplated racial characteristics of the Jones

and Johnston Elementary schools.

(7) It appearing that the lack of buildings prevents

the immediate implementation of the permanent plan of

the Office of Education suggested for the Quitman Consoli-

dated school district, the pupil attendance interim plan of

the Office of Education for this district is authorized for use

during the remainder of this school term (App. 5). The

permanent plan shall be effectuated commencing in Sep-

tember, 1970. This relief is appropriate in view of the sim-

ilarity between the proposed attendance plan of the school

district and that of the Office of Education.

It is ordered, adjudged and decreed that these respec-

tive plans shall remain in full force and effect until the

further order of this court. They may be modified by the

court through the following procedure. Honorable Dan M.

Russell, Jr., United States District Judge for the Southern

District of Mississippi, is hereby designated to receive sug-

gested modifications to the plans. No suggested modifica-

tion may be submitted to Judge Russell before March 1,

A2l

1970 and any such suggestion or request shall contemplate

an effective date of September, 1970.

Judge Russell is directed to make full findings of fact

with respect to any modification recommended or disap-

proved and these findings are to be referred to this court

for its review. Pursuant to the terms of the order of the

Supreme Court in Alexander v. Holmes County Board of

Education, supra, no amendment or modification to any

plan shall become effective without the order of this court.

This order is entered only after full consideration of

the suggested plans of the Office of Education and those

of the local school boards. It is apparent that in some in-

stances the plans are cursory in nature. They were devised

without pupil locator maps. They do not contain informa-

tion as to geographical area, transportation routes or dis-

tances. Some have not considered zoning. The school

board plans are almost all without statistical data as to

race. It is entirely possible that more effective plans can

be devised on a local level and that these will insure the

simultaneous accomplishment of maximum education and

unitary school systems. To this end, and as an imprimatur

of local consideration, it is suggested the school board spon-

sored requests for changes in plans show either Negro rep-

resentation on school boards or prior consideration by a

bi-racial advisory committee to the school board.

Nothing herein is intended to prevent the respective

school boards and superintendents from seeking the further

counsel and assistance of the Office of Education (HEW),

or the assistance of the Mississippi State Department of

Education, University Schools of Education in or out of Mis-

sissippi, or of others having expertise in the education field.

The motion of counsel in those cases instituted by pri-

vate litigants for attorneys fees is held in abeyance for the

A22

present. The motion of the private litigants to require the

filing of further plans by the Office of Education for use in

the Hinds County, Holmes County and Meridian districts

is denied.

Jurisdiction of these cases is retained in this court, pur-

suant to the aforesaid order of the Supreme Court, to in-

sure prompt and faithful compliance with this order. The

court also retains jurisdiction to modify or amend this or-

der as may be necessary or desirable to the end that unitary

school systems will be operated.

IT IS SO ORDERED.

This 7th day of November, 1969.

/s/. Griifin B, Bell

Griffin B. Bell

United States Circuit Judge

/s/ Homer Thornberry

Homer Thornberry

United States Circuit Judge

/s/ Lewis R. Morgan

Lewis R. Morgan

United States Circuit Judge

A23

APPENDIX C

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

No. 632.—October Term, 1969.

Beatrice Alexander, et al,

Petitioners On Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of

"Appeals for the Fifth Cir-

Holmes County Board of cuit.

Education et al.

Vv.

7

[ October 29, 1969.]

PER CURIAM.

These cases come to the Court on a petition for certi-

orari to the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit. The

petition was granted on October 9, 1969, and the case set

down for early argument. The question presented is one

of paramount importance, involving as it does the denial

of fundamental rights to many thousands of school children,

who are presently attending Mississippi schools under seg-

regated conditions contrary to the applicable decisions of

this Court. Against this background the Court of Appeals

should have denied all motions for additional time because

continued operation of segregated schools under a standard

of allowing “all deliberate speed” for desegregation is no

longer constitutionally permissible. Under explicit hold-

ings of this Court the obligation of every school district is

to terminate dual school systems at once and to operate

now and hereafter only unitary schools. Griffin v. School

Board, 377 U.S. 218, 234 (1964); Green v. County School

Board of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430, 438-439, 442

(1968). Accordingly,

IT IS HEREBY ADJUDGED, ORDERED, AND DE-

CREED:

1. The Court of Appeals’ order of August 28, 1969,

is vacated, and the cases are remanded to that court to

A24

issue its decree and order, effective immediately, declaring

that each of the school districts here involved may no

longer operate a dual school system based on race or color,

and directing that they begin immediately to operate as uni-

tary school systems within which no person is to be ef-

fectively excluded from any school because of race or color.

2. The Court of Appeals may in its discretion direct

the schools here involved to accept all or any part of the

August 11, 1969, recommendations of the Department of

Health, Education, and Welfare, with any modifications

which that court deems proper insofar as those recom-

mendations insure a totally unitary school system for all

eligible pupils without regard to race or color.

The Court of Appeals may make its determination and

enter its order without further arguments or submissions.

3. While each of these school systems is being op-

erated as a unitary system under the order of the Court of

Appeals, the District Court may hear and consider objec-

tions thereto or proposed amendments thereof, provided,

however, that the Court of Appeals’ order shall be com-

plied with in all respects while the District Court con-

siders such objections or amendments, if any are made.

No amendment shall become effective before being passed

upon by the Court of Appeals.

4. The Court of Appeals shall retain jurisdiction to

insure prompt and faithful compliance with its order, and

may modify or amend the same as may be deemed neces-

sary or desirable for the operation of a unitary school

system.

5. The order of the Court of Appeals dated August

28, 1969, having been vacated and the case remanded for

proceedings in conformity with this order, the judgment

shall issue forthwith and the Court of Appeals is requested

to give priority to the execution of this judgment as far

as possible and necessary.

A25

APPENDIX D

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

POR THE HMpPTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 28,030 and 28,042

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Plaintiff-Appellant

V.

HINDS COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD, et al,

Defendants-Appellees

AND OTHER CONSOLIDATED CASES

Judge Griffin B. Bell is hereby designated in the place

and stead of Chief Judge John R. Brown in these cases

and thenceforth the panel shall be composed of Judges

Bell, Thornberry and Morgan.

Order

In order that this Court may effectuate the order of the

Supreme Court of the United States of October 29, 1969,

the mandate in each and every one of the cases covered

by or included in this Court’s order of August 28, 1969,

granting a stay of the Court’s earlier orders of July 3 and

July 25, 1969, are hereby recalled effective immediately.

This panel of the Court hereby assumes direction and con-

trol of each of the cases for the purpose of effectuating the

order of the Supreme Court.

Appellants, appellees and the United States of Amer-

ica as amicus or intervenors shall file with the Clerk of

this Court on or before the fifth day of November, 1969,

A26

their recommended and proposed orders which will prop-

erly effectuate and implement the opinion and decree of

the Supreme Court of the United States rendered on Octo-

ber 29, 1969, in the above named cases.

October 31, 1969.

A27

APPENDIX E

IN THE

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 26285

DEREK JEROME SINGLETON, ET AL,

Appellants,

Versus

JACKSON MUNICIPAL SEPARATE

SCHOOL DISTRICT, ET Al,

Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Southern District of Mississippi

No. 28261

CLARENCE ANTHONY, ET AL,

Appellants,

Versus

MARSHALL COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION,

Appellee.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Northern District of Mississippi

No. 28045

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Appellant,

versus

CHARLES F. MATHEWS, ET AL,

Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Texas

A28

No. 28350

LINDA STOUT, by her father and next friend

BLEVIN STOUT, ET AL,

Plaintiffs- Appellants,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Intervenor,

versus

JEFFERSON COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, ET AL,

Defendants-Appellees,

DORIS ELAINE BROWN, ET AL,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Intervenor,

versus

THE BOARD OF FDUCATION OF THE CITY

OF BESSEMER, ET AL,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Northern District of Alabama

No. 28349

BIRDIE MAE DAVIS, ET AL,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Intervenor,

Versus

BOARD OF SCHOOL COMMISSIONERS OF

MOBILE COUNTY, ET AL,

Defendants-Appellees,

TWILA FRAZIER, ET AL,

Defendants-Intervenor-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Southern District of Alabama

A29

No. 28340

ROBERT CARTER, ET AL,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

versus

WEST FELICTANA PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, ET AL,

Defendants-Appellees,

SHARON LYNNE GEORGE, ET AL,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

versus

C. WALTER DAVIS, PRESIDENT, EAST FELICTIANA

PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, ET AL,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Louisiana

No. 28342

IRMA J. SMITH, ET AL,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

versus

CONCORDIA PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, ET AL,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Western District of Louisiana

No. 28361

HEMON HARRIS, ET AL,

Plaintiffs-Appellants-Cross Appellees,

versus

ST. JOHN THE BAPTIST PARISH SCHOOL BOARD,

ET AL,

Defendants-Appellees-Cross Appellants.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Louisiana

A30

No. 28409

NEELY BENNETT, ET AL,

Appellants,

versus

R. E. EVANS, ET AL,

Appellees,

ALLENE PATRICIA ANN BENNETT, a minor, by

R. B. BENNETT, her father and next friend,

Appellants,

versus

BURKE COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, ET AL,

Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Southern District of Georgia

No. 28407

SHIRLEY BIVINS, ET AL,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

versus

BIBB COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION AND

ORPHANAGE FOR BIBB COUNTY, ET AL,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Middle District of Georgia

No. 28408

OSCAR C. THOMIE, JR., ET Al,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

versus

HOUSTON COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Middle District of Georgia

A3l

No. 27863

JEAN CAROLYN YOUNGBLOOD, ET AL,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Intervenor,

versus

THE BOARD OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION

OF BAY COUNTY, FLORIDA, ET AL,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Northern District of Florida

No. 27983

LAVON WRIGHT, ET AL,

Plaintiffs- Appellants,

versus

THE BOARD OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION OF

ALACHUA COUNTY, FLORIDA, ET AL,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Northern District of Florida

(December 1, 1969)

Before BROWN, Chief Judge, WISDOM, GEWIN, BELL,

THORNBERRY, COLEMAN, GOLDBERG, AINS-

WORTH, GODBOLD, DYER, SIMPSON, MORGAN,

CARSWELL, and CLARK, Circuit Judges, EN BANC. *

PER CURIAM: These appeals, all involving school

desegregation orders, are consolidated for opinion pur-

poses. They involve, in the main, common questions of

¥*Judge Wisdom did not participate in Nos. 26285, 28261, 28045,

28350, 28349 and 28361. Judge Ainsworth did not participate in

No. 28342. Judge Carswell did not participate in Nos. 27863 and

27983. Judge Clark did not participate in No. 26285.

A32

law and fact. They were heard en banc on successive

days.

Following our determination to consider these cases

en banc, the Supreme Court handed down its decision

in Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, 1969,

ie US. .....998Ct. ...... 24 1.22d.2d 19. That decision

supervened all existing authority to the contrary. It sent

the doctrine of deliberate speed to its final resting place.

24 LL.Ed.2d at p. 21.

The rule of the case is to be found in the direction to

this court to issue its order “effective immediately de-

claring that each of the school districts . . . may no longer

operate a dual school system based on race or color, and

directing that they begin immediately to operate as unitary

school systems within which no person is to be effectively

excluded from any school because of race or color.” We

effectuated this rule and order in United States v. Hinds

County School Beard, 5 Cir., 1969, ....... ¥24 ..... , |Nog,

28,030 and 28,042, slip opinion dated Nov. 7, 1969]. It must

likewise be effectuated in these and all other school cases

now being or which are to be considered in this or the

district courts of this circuit.

The tenor of the decision in Alexander v. Holmes

County is to shift the burden from the standpoint of time

for converting to unitary school systems. The shift is

from a status of litigation to one of unitary operation pend-

ing litigation. The new modus operandi is to require im-

mediate operation as unitary systems. Suggested modi-

fications to unitary plans are not to delay implementa-

tion. Hearings on requested changes in unitary operating

plans may be in order but no delay in conversion may

ensue because of the need for modification or hearing.

In Alexander v. Holmes County, the court had unitary

plans available for each of the school districts. In addi-

A33

tion, this court, on remand, gave each district a limited

time within which to offer its own plan. It was apparent

there, as it is here, that converting to a unitary system

involved basically the merger of faculty and staff, students,

transportation, services, athletic and other extra-curricu-

lar school activities. We required that the conversion to

unitary systems in those districts take place not later than

December 31, 1969. It was the earliest feasible date in the

view of the court. United States v. Hinds County, supra.

In three of the systems there (Hinds County, Holmes

County and Meridian), because of particular logistical dif-

ficulties, the Office of Education (HEW) had recom-

mended two step plans. The result was, and the court

ordered, that the first step be implemented not later than

December 31, 1969 and the other beginning with the fall

1970 school term.

I

Because of Alexander v. Holmes County, each of the

cases here, as will be later discussed, must be considered

anew, either in whole or in part, by the district courts.

It happens that there are extant unitary plans for some

of the school districts here, either Office of Education or

school board originated. Some are operating under free-

dom of choice plans. In no one of the districts has a plan

been submitted in light of the precedent of Alexander wv.

Holmes County. That case resolves all questions except

as to mechanics. The school districts here may no longer

operate dual systems and must begin immediately to oper-

ate as unitary systems. The focus of the mechanics ques-

tion is on the accomplishment of the immediacy require-

ment laid down in Alexander v. Holmes County.

Despite the absence of plans, it will be possible to

merge faculties and staff, transportation, services, ath-

letics and other extra-curricular activities during the pres-

A34

ent school term. It will be difficult to arrange the merger

of student bodies into unitary systems prior to the fall

1970 term in the absence of merger plans. The court has

concluded that two-step plans are to be implemented. One

step must be accomplished not later than February 1, 1970

and it will include all steps necessary to conversion to a

unitary system save the merger of student bodies into

unitary systems. The student body merger will constitute

the second step and must be accomplished not later than

the beginning of the fall term 1970." The district courts,

in the respective cases here, are directed to so order and

to give first priority to effectuating this requirement.

To this end, the district courts are directed to require

the respective school districts, appellees herein, to request

the Office of Education (HEW) to prepare plans for the

merger of the student bodies into unitary systems. These

plans shall be filed with the district courts not later than

January 6, 1970 together with such additional plan or mod-

ification of the Office of Education plan as the school dis-

trict may wish to offer. The district court shall enter its

final order not later than February 1, 1970 requiring and

setting out the details of a plan designed to accomplish a

unitary system of pupil attendance with the start of the

fall 1970 school term. Such order may include a plan de-

signed by the district court in the absence of the submis-

sion of an otherwise satisfactory plan. A copy of such plan

1. Many faculty and staff members will be transferred under

step one. It will be necessary for final grades to be entered and

for other records to be completed, prior to the transfers, by the

transferring faculty members and administrators for the partial

school year involved. The interim period prior to February 1, 1970

is allowed for this purpose.

The interim period prior to the start of the fall 1970 school

term is allowed for arranging the student transfers. Many stu-

dents must transfer. Buildings will be put to new use. In some

instances it may be necessary to transfer equipment, supplies or

libraries. School bus routes must be reconstituted. The period

allowed is at least adequate for the orderly accomplishment of

the task.

A35

as is approved shall be filed by the clerk of the district

court with the clerk of this court.?

The following provisions are being required as step one

in the conversion process. The district courts are directed

to make them a part of the orders to be entered and to

also give first priority to implementation.

The respective school districts, appellees herein,

must take the following action not later than February

1, 1970;

DESEGREGATION OF FACULTY AND

OTHER STAFF

The School Board shall announce and implement

the following policies:

1. Effective not later than February 1, 1970, the

principals, teachers, teacher-aides and other staff who

work directly with children at a school shall be so as-

signed that in no case will the racial composition of a

staff indicate that a school is intended for Negro stu-

dents or white students. For the remainder of the 1969-

70 school year the district shall assign the staff de-

scribed above so that the ratio of Negro to white teach-

ers in each school, and the ratio of other staff in each,

are substantially the same as each such ratio is to

the teachers and other staff, respectively, in the en-

tire school system.

The school district shall, to the extent necessary

to carry out this desegregation plan, direct members of

2. In formulating plans, nothing herein is intended to prevent

the respective school districts or the district court from seeking

the counsel and assistance of state departments of education, uni-

versity schools of education or of others having expertise in the

field of education.

It is also to be noted that many problems of a local nature

are likely to arise in converting to and maintaining unitary sys-

tems. These problems may best be resolved on the community

level. The district courts should suggest the advisability of bi-

racial advisory committees to school boards in those districts

having no Negro school board members.

A36

its staff as a condition of continued employment to ac-

cept new assignments.

2. Staff members who work directly with children,

and professional staff who work on the administrative

level will be hired, assigned, promoted, paid, demoted,

dismissed, and otherwise treated without regard to

race, color, or national origin.

3. If there is to be a reduction in the number of prin-

cipals, teachers, teacher-aides, or other professional

staff employed by the school district which will re-

sult in a dismissal or demotion of any such staff mem-

bers, the staff member to be dismissed or demoted

must be selected on the basis of objective and reason-

able non-discriminatory standards from among all the

staff of the school district. In addition if there is any

such dismissal or demotion, no staff vacancy may be

filled through recruitment of a person of a race, color,

or national origin different from that of the individual

dismissed or demoted, until each displaced staff mem-

ber who is qualified has had an opportunity to fill the

vacancy and has failed to accept an offer to do so.

Prior to such a reduction, the school board will de-

velop or require the development of non-racial objec-

tive criteria to be used in selecting the staff member

who is to be dismissed or demoted. These criteria shall

be available for public inspection and shall be retained

by the school district. The school district also shall

record and preserve the evaluation of staff members

under the criteria. Such evaluation shall be made

available upon request to the dismissed or demoted

employee.

“Demotion” as used above includes any reassign-

ment (1) under which the staff member receives less

pay or has less responsibility than under the assign-

ment he held previously, (2) which requires a lesser

degree of skill than did the assignment he held previ-

ously, or (3) under which the staff member is asked

A317

to teach a subject or grade other than one for which

he is certified or for which he has had substantial ex-

perience within a reasonably current period. In gen-

eral and depending upon the subject matter involved,

five years is such a reasonable period.

MAJORITY TO MINORITY

TRANSFER POLICY

The school district shall permit a student attend-

ing a school in which his race is in the majority to

choose to attend another school, where space is avail-

able, and where his race is in the minority.

TRANSPORTATION

The transportation system, in those school dis-

tricts having transportation systems, shall be com-

pletely re-examined regularly by the superintendent,

his staff, and the school board. Bus routes and the as-

signment of students to buses will be designed to insure

the transportation of all eligible pupils on a non-segre-

gated and otherwise non-discriminatory basis.

SCHOOL CONSTRUCTION AND

SITE SELECTION

All school construction, school consolidation, and

site selection (including the location of any temporary

classrooms) in the system shall be done in a manner

which will prevent the recurrence of the dual school

structure once this desegregation plan is implemented.

ATTENDANCE OUTSIDE SYSTEM

OF RESIDENCE

If the school district grants transfers to students

living in the district for their attendance at public

schools outside the district, or if it permits transfers

into the district of students who live outside the dis-

trict, it shall do so on a non-discriminatory basis, ex-

cept that it shall not consent to transfers where the

cumulative effect will reduce desegregation in either

district or reinforce the dual school system.

A38

See United States v. Hinds County, supra, decided Novem-

ber 6, 1969. The orders there embrace these same require-

ments.

II

In addition to the foregoing requirements of general

applicability, the order of the court which is peculiar to

each of the specific cases being considered is as follows:

NO. 26285—JACKSON, MISSISSIPPI

This is a freedom of choice system. The issue pre-

sented has to do with school building construction. We en-

joined the proposed construction pending appeal.

A federal appellate court is bound to consider any

change, either in fact or in law, which has supervened since

the judgment was entered. Bell v. State of Maryland, 378

U.S. 226, 84 S.Ct. 1814, 12 L.Ed.2d 822 (1964). We there-

fore reverse and remand for compliance with the require-

ments of Alexander v. Holmes County and the other pro-

visions and conditions of this order. Our order enjoining

the proposed construction pending appeal is continued in

effect until such time as the district court has approved a

plan for conversion to a unitary school system.

NO. 28261—MARSHALL COUNTY AND HOLLY

SPRINGS, MISSISSIPPI

This suit seeks to desegregate two school districts,

Marshall County and Holly Springs, Mississippi. The dis-

trict court approved plans which would assign students to

schools on the basis of achievement test scores. We pre-

termit a discussion of the validity per se of a plan based

on testing except to hold that testing cannot be employed

in any event until unitary school systems have been es-

tablished.

A39

We reverse and remand for compliance with the re-

quirements of Alexander v. Holmes County and the other

provisions and conditions of this order.

NO. 28045—UNITED STATES V. MATTHEWS

(LONGVIEW, TEXAS)

This system is operating under a plan approved by the

district court which appears to be realistic and workable

except that it is to be implemented over a period of five

years. This is inadequate.

We reverse and remand for compliance with the re-

quirements of Alexander v. Holmes County and the

other provisions and conditions of this order.

NO. 28350—JEFFERSON COUNTY AND

BESSEMER, ALABAMA

These consolidated cases involve the school boards

of Jefferson County and the City of Bessemer, Alabama.

Prior plans for desegregation of the two systems were

disapproved by this court on June 26, 1969, United States

of America v. Jefferson County Board of Education, et al.,

iiRhe F.2d ....... (5th Cir. 1969) [No. 27444, June 26, 1969],

at which time we reversed and remanded the case with

specific directions. The record does not reflect any sub-

stantial change in the two systems since this earlier opin-

ion, and it is therefore unnecessary to restate the facts.

The plans approved by the district court and now under

review in this court do not comply with the standards re-

quired in Alexander v. Holmes County.

We reverse and remand for compliance with the re-

quirements of Alexander v. Holmes County and the

other provisions and conditions of this order.

A40

NO. 28349—MOBILE COUNTY, ALABAMA

On June 3, 1969, we held that the attendance zone and

freedom of choice method of student assignment used by

the Mobile School Commissioners was constitutionally un-

acceptable. Pursuant to our mandate the district court re-

quested the Office of Education (HEW) to collaborate

with the board in the preparation of a plan to fully desegre-

gate all public schools in Mobile County. Having failed to

reach agreement with the board, the Office of Education

filed its plan which the district court on August 1, 1969,

adopted with slight modification (but which did not reduce

the amount of desegregation which will result). The

court’s order directs the board for the 1969-1970 school

year to close two rural schools, establish attendance zones

for the 25 other rural schools, make assignments based on

those zones, restructure the Hillsdale School, assign all stu-

dents in the western portion of the metropolitan area ac-

cording to geographic attendance zones designed to deseg-

regate all the schools in that part of the system, and re-

assign approximately 1,000 teachers and staff. Thus the

district court’s order of August 1, now before us on appeal

by the plaintiffs, will fully desegregate all of Mobile County

schools except the schools in the eastern portion of metro-

politan Mobile where it was proposed by the plan to trans-

port students to the western part of the city. The district

court was not satisfied with this latter provision and re-

quired the board after further study and collaboration with

HEW officials, to submit by December 1, 1969, a plan for

the desegregation of the schools in the eastern part of the

metropolitan area.

The school board urges reversal of the district court’s

order dealing with the grade organization of the Hills-

dale School and the faculty provisions.

We affirm the order of the district court with direc-

tions to desegregate the eastern part of the metropolitan

A41

area of the Mobile County School System and to otherwise

create a unitary system in compliance with the require-

ments of Holmes County and in accordance with the other

provisions and conditions of this order.

NO. 28340—EAST AND WEST FELICIANA

PARISHES, LOUISIANA

East Feliciana is operating under a plan which closed

one rural Negro elementary school and zoned the four re-

maining rural elementary schools. All elementary stu-

dents not encompassed in the rural zones, and all high

school students, continue to have free choice. Majority to

minority transfer is allowed on a space-available basis

prior to beginning of the school year.

The plan has not produced a unitary system. We re-

verse and remand for compliance with the requirements

of Alexander v. Holmes County and the other provisions

and conditions of this order.

West Feliciana is operating under a plan approved

for 1969-70 which zones the two rural elementary schools.

These schools enroll approximately 15 per cent of the stu-

dents of the district. The plan retains “open enrollment”

(a euphemism for free choice) for the other schools. The

plan asserts that race should not be a criterion for employ-

ment or assignment of personnel. However, the board

promises to seek voluntary transfers and if substantial

compliance cannot be obtained by this method it proposes

to adopt other means to accomplish substantial results.

This plan has not produced a unitary system. We

reverse and remand for compliance with the requirements

of Alexander v. Holmes County and the other provisions

and conditions of this order.

A42

NO. 28342—CONCORDIA PARISH, LOUISIANA

The plan in effect for desegregating this school dis-

trict has not produced a unitary system. It involves

zoning, pairing, freedom of choice and some separation by

sex. We pretermit the question posed as to sex separation

since it may not arise under such plan as may be approved

for a unitary system.

This plan has not produced a unitary system. We

reverse and remand for compliance with the requirements

of Alexander v. Holmes County and the other provisions

and conditions of this order.

NO. 28361—ST. JOHN THE BAPTIST

PARISH, LOUISIANA

This school district has been operating under a free-

dom of choice plan. The parish is divided into two sec-

tions by the Mississippi River and no bridge is located

in the parish. The schools are situated near the east and

west banks of the river.

A realistic start has been made in converting the

east bank schools to a unitary system. It, however, is

less than adequate. As to the west bank schools, the

present enrollment is 1626 Negro and 156 whites. The

whites, under freedom of choice, all attend the same

school, one of five schools on the west bank. The 156

whites are in a school with 406 Negroes. We affirm

as to this part of the plan. We do not believe it necessary

to divide this small number of whites, already in a deseg-

regated minority position, amongst the five schools.

We reverse and remand for compliance with the re-

quirements of Alexander v. Holmes County and the other

provisions and conditions of this order.

A43

NO. 28409—BURKE COUNTY, GEORGIA

The interim plan in operation here, developed by the

Office of Education (HEW), has not produced a unitary

system. The district court ordered preparation of a final

plan for use in 1970-71. This delay is no longer permissible.

We reverse and remand for compliance with the re-

quirements of Alexander v. Holmes County and the other

provisions and conditions of this order.

NO. 28407—BIBB COUNTY, GEORGIA

This is a freedom of choice system on which a special

course transfer provision has been superimposed. Special

courses offered in all-Negro schools are being attended by

whites in substantial numbers. This has resulted in some

attendance on a part time basis by whites in every all-Negro

school. Some three hundred whites are on the waiting list

for one of the special courses, remedial reading. The racial

cross-over by faculty in the system is 27 per cent.

The order appealed from continues the existing plan

with certain modifications. It continues and expands the

elective course programs in all-Negro schools in an effort

to encourage voluntary integration. The plan calls for a

limitation of freedom of choice with respect to four schools

about to become resegregated. Under the present plan the

school board is empowered to limit Negro enrollment to

40 per cent at these schools to avoid resegregation. Earlier

a panel of this court affirmed the district court’s denial of

an injunction against the quota provision of this plan pend-

ing hearing en banc. The prayer for injunction against

continuation of the quota provision is now denied and the

provision may be retained by the district court pending

further consideration as a part of carrying out the re-

quirements of this order.

A44

It is sufficient to say that the district court here has

employed bold and imaginative innovations in its plan

which have already resulted in substantial desegregation

which approaches a unitary system. We reverse and re-

mand for compliance with the requirements of Alexander

v. Holmes County and the other provisions and conditions

of this order.

NO. 28408—HOUSTON COUNTY, GEORGIA

This system is operating under a freedom of choice

plan. Appellants seek zoning and pairing. There is also

an issue as to restricting transfers by Negroes to formerly

all-white schools. Cf. No. 28407—Bibb County, supra. In

addition, appellants object to the conversion of an all-

Negro school into an integrated adult education center.

As in the Bibb County case, these are all questions for

consideration on remand within the scope of such uni-

tary plan as may be approved.

We reverse and remand for compliance with the re-

quirements of Alexander v. Holmes County and the other

provisions and conditions of this order.

NO. 27863—BAY COUNTY, FLORIDA

This system is operating on a freedom of choice plan.

The plan has produced impressive results but they fall

short of establishing a unitary school system.

We reverse and remand for compliance with the re-

quirements of Alexander v. Holmes County and the other

provisions and conditions of this order.

NO. 27983—ALACHUA COUNTY, FLORIDA

This is another Florida school district where impres-

sive progress has been made under a freedom of choice

plan. The plan has been implemented by zoning in the

A45

elementary schools in Gainesville (the principal city in

the system) for the current school year. The results to

date and the building plan in progress should facilitate

the conversion to a unitary system.

We reverse and remand for compliance with the re-

quirements of Alexander v. Holmes County and the other

provision and conditions of this order.

III

In the event of an appeal or appeals to this court

from an order entered as aforesaid in the district courts,

such appeal shall be on the original record and the parties

are encouraged to appeal on an agreed statement as is pro-

vided for in Rule 10(d), Federal Rules of Appellate Pro-

cedure (FRAP). Pursuant to Rule 2, FRAP, the provisions

of Rule 4(a) as to the time for filing notice of appeal are

suspended and it is ordered that any notice of appeal be

filed within fifteen days of the date of entry of the order

appealed from and notices of cross-appeal within five

days thereafter. The provisions of Rule 11 are suspended

and it is ordered that the record be transmitted to this

court within fifteen days after filing of the notice of ap-

peal. The provisions of Rule 31 are suspended to the ex-

tent that the brief of the appellant shall be filed within

fifteen days after the date on which the record is filed and

the brief of the appellee shall be filed within ten days

after the date on which the brief of appellant is filed.

No reply brief shall be filed except upon order of the court.

The times set herein may be enlarged by the court up-

on good cause shown.

The mandate in each of the within matters shall issue

forthwith. No stay will be granted pending petition for

rehearing or application for certiorari.

A46

REVERSED as to all save Mobile and St. John The

Baptist Parish; AFFIRMED as to Mobile with direction;

AFFIRMED in part and REVERSED in part as to St.

John The Baptist Parish; REMANDED to the district

courts for further proceedings consistent herewith

APPENDIX F

Proceedings

JUDGE BELL:

Ladies and gentlemen, we have called this Pre-order

conference today for the purpose of making some an-

nouncements and also to exchange views. After we make

some statements, we want everyone to feel free to ask

questions. We don’t intend to have any legal arguments,

as such, but we do think it would be well for anyone that

has questions, that you feel free to make such inquiries as

you may have.

My name is Judge Bell. I happen to be from Georgia.

On my right is Judge Thornberry from Texas, and on my

left is Judge Morgan from Georgia. We are the panel of the

Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals that has been assigned to

hear this case, or these cases. There are really twenty-

five cases and thirty school districts involved.

I came to these cases within the last few days. Judge

Morgan and Judge Thornberry have heard arguments dur-

ing the past summer in the cases. But since last Friday

we have all been engaged in studying the plans.

We first studied all the HEW plans because they were

all the ones that we had on hand. Since then we have

taken the time and had the occasion to study all of the

Mississippi plans.

Now, there is one district, Covington, Mississippi, that

has not submitted a plan, but we have had plans from every