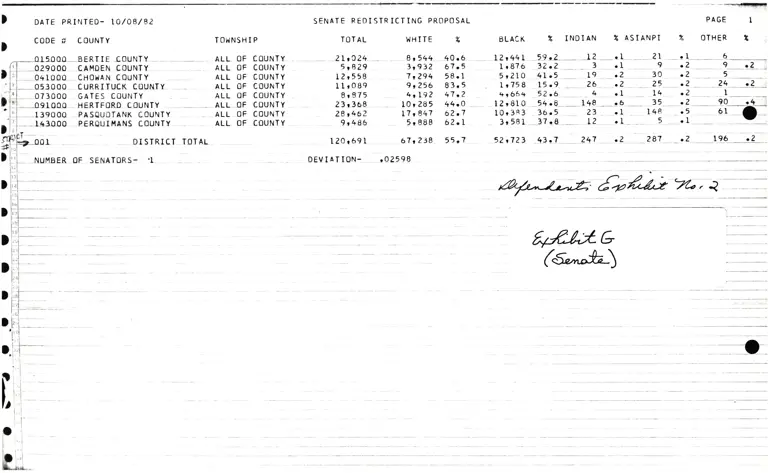

Senate Redistricting Proposal Population Statistics

Working File

October 8, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Senate Redistricting Proposal Population Statistics, 1982. accd3016-e292-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1e39def8-0dc1-4694-b0c2-5f4523fb1669/senate-redistricting-proposal-population-statistics. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

)

)

DATE PRINTED. LO/08/82

CODE i: C OUNTY

SENATE REOISTR

TOT AL

.2LtC24

5 1829

L? t558

Ilr0B9

8r875

23r368

28 t462

9r486

IZ0r691

ICTING PROPOSAL

WH ITE Z

8t544 40.6

11932 61.5

1 t 294 58.I

9t256 83.5

4r l9 ? 41.?

l0r 285 44.4

t7 r 847 62cl

5 r 888 62.1

67 | 2)A 55.1

_* _--irtlE

PAGE I

Z OTHER tBLACK

l?r44L 59 t2.

I r 876 32.?

5r2lO 4L.5

1r758 L5.9

4t664 52.6

lZrBl0 - 54.8-

l0r3A3 36.5

3r581 37rB

INDIAN Z

-- -l? - --cl

- 3 .1

19 ..2

26 .2

TOI{NSH I P

ALL

ALL

ALL

ALL

ALL

ALL

ALL

ALL

COUNTY

COI'NTY

COUNTY

COUNTY

COUNTY

COUNTY

COUNTY

COUNT Y

AS I ANPI

-" zr_,__ol50oo - BERIIE CoUNTY

- lr t _ 029000 cAMDEN CoUNTY, i-i 04rooo cHot.tAN couNTY^[,i- o53ooo cuRRITucK couNTY

^ i'l oz3ooo GATEs couNTY

? i:i- -oerooo HERTFoRD couNTY

,,"j I3e00o PASQUoTANK couNTY

rili; . l41oo0 PERQUTMANS couNTY

ff]p-oor Dr sTRrcr rorAl

)llil,. Nur'lBER oF sENAToRs- 'I

OF

OF

OF

OF

OF

OF

OF

OF

4 .l 14 .2 I

15 - . .?..-.-.*

148 .5

5 ,, .I -

90 tt+.tl.)l

52t7?3 43 1 ?41 ..2 .28'l -.2 - - 196

-

o2

DEVIATION- I02598

l; ,1-

l,'l-: -:rii -

t"D'-- o

It

lil ''lr'-

a

OATE PRINTEO- IOIOSl82 SENATE REOISTRICTING PROPOS L

COOE * COUNTY TOT.INSHIP TOTAL XHITE : BLACK t INOIAN I ASIANPI

PAGE

OTHER

?? .l.1... _or3Q!0 BEtuEaEI-J0ultJL--A!!-_qF goqNly -_ *_J9r355_ 21.2!J 6-__!g.r_t_- ra! 8_o_9__1r.!.7 L_6 3!

ri-._oE a0s_--0ALEl-qqu!- * __* _-^!L QF cQuNry _ _ __!31371___..-.-. -!?1968_-_?3r?-.- 82?_ 5.? 1_8 .l rr,0

Ll rr?oo0 -!l!lJl!{ Eo-UI{!Y--

-

Al.L 0F COUNTY

--?5.e+8.--,

_!4r33ar_ 55,.2,___11.r555 _-49.5__ 2

lF_rsoo* p^riico-courrvll]-l -.-l-[- or- coJrrry _.: _ t0r3e8_ irl00 _ 68.3_--_-.3,238 3l.l 35,l r ?7000___IIR-R!Lt.lquNTL ALL_oi.c!ullrf,_ 3te1?__LL4 r i.-__69. e_. !r55o le.O 3ll . 187ooO --!a5HIt{CI9ll. LoUl{-LY- --,-----.- ALL -OE*CouhT.Y. _-_,_ __,_-- 11 r 8.0_l_. __.._. 9 r.3 46 .5614 _ _- €.r +!0 . ..11.r 3______ q *_

DISTRICT TOTAL LL4t7 27 . 15t9L9 66tZ 381476 ?).5 0O -_ al _ __

OF .SENATORS- -..I. DEV I AT I 0N:. -. --r Q241 ?:

.2

.1

.1

.l

.1

l5

.3

.1

.l

.2

34

10

24

.3

.l

24

23

r 1-- lQe-

OATE PRINTED. LO/O8/82 SENATE REDISTRICTING PROPOSAL

CODE i' C OUNTY TOhJNSH I P TOTAL WH IT E Z

PAGE 3

X OTHER Z

0o - CARTERET--C0uNTY .-- ALL. oF couNTy 4Lte9? 36r 87 t B9.z

)ll [

_o.ce00o__ caAVEN couNrY ALL 0F C0UNTY 7lr043 501408 Tl.0

'l;l--oof _ DI STRICT r0TAL tt2rl35 BT rzts 77 .B

)-;';F-f t{ttilgEn *oF--5ENAToRS-:.- l- .. -.__ DEVIAT IgN: _ _ te4675-

BLACK

-3r859

L9 t287

23 t L46

Z INOIAN Z

9 t4 --- I?5 _-.--.3

27 o? t8+-- '3

7Qt6 - 309 -o3

ASIANPI

-- -- 142 -*:4----. 95----12--

. _-184 .7 --- 5-80 --. L.0

_ o_zo __.o __175_

--lil-_-

o

l;i

li

l, rl

DATE PRINTED- LO/OI/82

COOE T COUNTY

SENATE REDTSTRICTING PROPOSAL

TO}INSHI P TOTAL I{HITE Z BLACK INO I AN Z ASIANPI

rfT-oNqr FLr cnuNrY ALL oF CoUNfY 112.784 - 85149.8 75?8 _ ?/t715 ?O.

-o03-'_--.-0IsT8Ic.I_IQI^L--_-_-,--.-._.'_-.'-_,,__--1,!2rIQ4--*-9!r19c_1,'-'.!:_-'.?.;.?-7'-?ffi

.-*-NrUBE&-QF- -SENA.TQB S: -. l.' A E Y LA I- I-Ol,l :-- - gQ (! ?(:

PAGE

OTHER

4

2.2

-

OAIE PRINTED- IO/08/82

'r cooE g couNTY TOI{NSH I P

SENATE REOISTRICTING PROPOSAL

TOTAL HHITE Z BLAC K INOIAN T ASIANPI

PAGE

OTHER

Ihl cor.rttTY ALLIIL CotrNrY - 40 *952.--- 261 835--..65.$--.---_L{r,001-*1*rZ-lL.--r-l- I.9---r l-

IOOO*.JOI{ES -CIIrllrT.Y. --

-ALL..lrF

COUNTY..,---,-., -- 9r7o5..--- 5r462-.. r5.3,-.- 1t212 --41.4, *lO----. a-.0-_' r_ l'-i

TOOO--LEN0IR f OUltTY-.-

-,--_-

ALL ,OF-C0UI{TY 5er0l9 361911 61.5 22.?95 la.t 56 .I e2 -2 6536r3ll -61r5 -. ...-. 22t795 --38.1 56 .1 92 .2

_ uaYt{LCoufl.T-Y ----IUOIAI{ SPRINGS-IOHttS-- 3r55? -.-_ 2t77?_ 18t0_- _ __ -- 15? -__ ?Lz1*__.._4__. I 9 .3 I

E8, -OF--.SEiII,TORS: -l *--= OE IIA U ON:---r o 3 0 66-_-

DATE PRINTEO- IO/OA/82

SENAIE REOISTRICTING PROPOSAL

PAGE

::::,: ::::::"

rolrNsHrp roral r{HrrE r sLAcK r rNoraN I AsrANpr r orHER

#ii8_f338:3lSE CSUI+I__*_ rouNsHrp_2,_r.oxER co_ r,t!?__._ 875 _1ei __._8zr_50.4*xi! !*iiilii iiilii _

IBItiXIt i: !il;i^,,

_ilr__ _ liiji:i - _ ii6_iiir_ _:=j_,,!qor040 EoGEcoHsE couNry . _"_. roiriiiii; ii il,liie,* r;iii _ - 331 3]:l _ -_- 5es__62;d__:_-:..-=:!__._'

_ff;gl8 ,EBSEEBIBE:Bylly iori,,i;Hi; i;6ii;iiR iiair_._ . t,iii-.Zii 554 3o.i-es?gri:;o;;;;i;i;ffiii__ _ ISXX;[il ii: lllfil-' :;:ii i;;i;-;;:" r,iio ii]j._-'.--_ooroii _EdaEaoi,;i;;;ilii

rnur(u,o ,, .^..-..r___1,?a!_ - _- zir si.s -,;id ;i:; , i - ,. _ _ 4_ ..r_ __

g!io7o.-. eoeeco{BE .couNTy Towt{sHIP 13r GoKEY - tt267 - - - eii Zi.a 3s5 !0.4

-91:99oGReetecourrTi.T0}lsHlPl4rUPPERr--riial----..r'oiiii]al59l3.4l.7oon orr" .d,,r,rv aLL oF couNTy toirrz___ "_ -;:;;; ;;:;r47o0o -urlrour{Ty ;ii 6i ;ililii ro'r17 8'78t 54.5 z,zge --;i.jl -z-=-: :.- i .r----zj_.-.Lr ei _(,eq!rr y , _. ,901146 ._,!9r?04-, ol.t _ ._3g,3i,a 3iii -

"i -r 2,^ , ..^^

_.__J3 o 7 _.-_- __ _B_g_ _Lr____32Q_ .4 .2'--_ _-,q _ _ir_ rzg .t__ l_9OoISIEICT rot^r

I -lIE-SEl{r.TOt S: --l _.- -_.-_- - . - oEvIATron- -o i zen_ UEYIaTION_ ... .012a8

i;

oZ

_t:_r:IIj:

SENATE REDISTRICTING PROPOSAL/82

OUNTY

OUNTY

OUNT Y

OUNTY

OUNTY

OUNIY

NTY

C OUNT Y

I STRICT TOTAL

I

DATE PRINTED- LO/08

CODE i' COUNTY

r1-._ 065005 EDGECOMBE C

l'l 065020 EDGECoMBE C

l'l 065025 EOGECOMEE C

l'i_ - 065030 EDGECOMBE C

i: i 065035 EDGEcor,!BE c

l:l 065060 E0GECOHBE C

;:l 083OOO HALTFAx C0rJ

l:t 13looo N0RTHAr.ipToN

l:i . ooz D

[' I - -Nur,rBER oF sENAToRS-

ltil,,r

1,.,it-:

i' 'i

ttl-t-

';i-_-;,Il---

..,1t----

-.1

:l

,rl

t.

I

PAGE 1

Z OTHER

.l . 7

z

----.c.I-- -,-

TOHNSHI P

TO!ITISHIP 1r TARBORO

TOhINSHI P 4I DEEP CRE

TOI"JNSHIP 5t L0HER FI

T0tiNSHIP 6r UPPER FI

T0ir{NSHIP 7t SlilIFT CR

T0l{NSHIP L2t ROCKY tt

ALL OF COUNTY

ALL OF COUNTY

t,H ITE U

9 r 086 60.5

383 38.8

769 53.3

55? 3 1.0

9lg ?9.2

8t?75 39.9

27 t559 49.9

I tOZ4 39. I

56t166 16c6

.02836

Z INOIAN Z ASIANPIBLACK

5rBB5

602' 61?

Lt22O

2t?22

1?r398

26t05)

13 r 709

62t761

TOTAL

t5r0I0

986

L t443

lrTBI

3r 147

?0 t7 )4

55 t2Bb

22 t5 84

120r971

z8

2 .l

? .I

g5 .2 371 .7

9B

39 o?

6l.l

46.6

68.5

70 .6

59 .8

47 .L

50 .7

4

I

7

5

L2

l2r7

34

.l

.4

.2

-.,.I

2.2

a?

51.9 I2S0 1.1 _I49 rl 11,5 -_-a3

DEVIATION-

I

!

I

.l

I

I

l.

i

i;

t:

i

L

'!

!,

!,:

t:

I

DATE PRINTED. LO/O|/82

CODE # COUNTY

SENATE REDISTRICTING PROPOSAL

TOTAL WH ITE Z BLACK Z INDIAN

fi]lJ'Il".-..iiif:-:fljnxll---__**?H.91:r+9.1---1!.30r.-__4o.,r__3s.......".1r 43 ir_?q 4s! -routrrY.

-.-*-allor -couuir.:llliii- tsra -o' L-- rr ':11--r-9-,r-38--=.-"-rr {i-ql-?:

o _-urs,BENlouuii_*-*__1."lr-L oF couNry ,^-,r: __*l:]t? --ig.l___:i,94s _:z.s__-'.si__, i_*rre-._,,?_!,

_9.---?3 -_-. t----eQ

113r440r4-4o.--__--601 209 60r2--- --.. 44'043 - io-..a*_- rai-.7 --? r5__.e _---l

EB-OF-- -SEflAT-0R5.:..- -l -. - -__ _ o-r[r I i fory:* ___.Oa5.6 6_

TOI{NSHI P

PAGE

T ASIANPI Z OTHER

t,

*

;i-+,

*frii,f "

'W' 'q'

:# +,.

,*.'

.'#,r'-j.'

.iilr

i,r:r. $*S

|S;t ':

... *'ttr.{liHtiiE[of g:&iiitEE'

rr

4i

. ,' .,i.t

I

OATE PRINTED- IO/08/82

CODE S COUNTY

SENATE REOISTRICTING PROPOSAL

TOI{N SH I P TOTAL I{HITE I BLACK Z INDIAN Z ASIANPI

fffii[,flYll3ltfE-'fHlf;ln.- - -.l*:333--ff:li]-13:3---ti:tti-..D-t--{l..."-1--e}-.1--.?-?r..rlrE_LuuN ry-- ___BRocoEN TorNsHtp.. __-.r8r005 ._.. ttrs?{ o:.r-.-.. - Jioii_:a---l_fi.._.i-*+*i-i.--i4xrYL.coutrTy--____---.--_-_...BUct<-s]lAr{p.Toul{sHrp,;ioi r.7r6 Ar-a r.. i!i r.^y E coumy- ---_:Foii:i;iGii;"--'-- - ;:;;; - *;:;;; ;;:: "- ';-3li-..11.1----"---;,-----.?---.1

----FoRK-rormnre.

_ _. ;:i;; __

'__. iliii_ E6lI_ __i;ii!:-!ili_i,_;__:ri_:i-:-*i____ :gl3:p?lo.I9:l!:Tlp_ _22',7!9 .. -_ rl,?!1_ !+.0 ,_ - r+,ors..- si.i._'ia-.-,r,__ sq_ .3 7r .rrozo-rAylE-courrv

-- 1;i;-{;;;;i;;i,rii'. rt .-- ,il)ii-'*-'.' !':::-::'7- '--.f ':z:: -:l r!--zc-rl--2!-r 3---:. 5-----r

PAGE

Z OTHER Z

-.-,rErrev2_ .- _ -LLtalj Q?oI . 6rQ63____33r? -._. _3-0--__eZ qg-_._

-...ZrlOE 11716 01./r. ..-.,388_-tB._4_- 3

25----rAyr{E-r^r{rr-- *- iilri,;i_-roiiis,iit . -'iiiii__' 'liliii__iili___jlliii_il.:l--.l:ji__j=j}l-+

*-HltF lt!l$I_ _-____,glgll_!r!ry iorninri_-iizrs._ *. iis _i+.i-: -'- 3or-- ?+.s 3 .zEroari nii,rr rouiiii ".__ _iiiii,iri"iiii,,iilil,l:::1.iliil-.--;,i-il:2iiZ: i,iil:-illi-- i--ii--.r::-=--l;=

rrru>, . *AyNts rEUNry ... sAuLsroN Tolr{srtp -.2,afi..=____irori lii.a.-.- ooa,-jz..j ___* r_ ---.;=j-j_Irer'IrAo --r^YrE ' couNrY - - -- -srot{Y iieei ioliiiup - _l-,gz+ -.---- iii.ii-,..ri.i-----rr2!i-1f .8 r0_r! tr_ru.-ar_ .,l95oo0 llILSot{ couNTY aLL oF cout{rY . -.or,raz ..-:iiiii. .il,i -- -,ae,sar- - a6-r +---3-?-...L--?-q-..a ?3 .l

IIUIIBER OF SEflATOF S.

. ol,l.z -.. ,39t94t .03'o3 __-. -,??r90l_ - l6_rt__f-Z*_. L-_f_e--:

DtsTRlcr toral ?zttl3! - - 118.016- es.s -- _ Czrf:r li.e :-Oo .I--- 5dL-;_5_gg-_._3_ _5_,58

oEv IAT ION- oo34l6-

\l4r'!i.i

--'ilG;

-&+*{: *\.-

,;4iF,:i).i.r

10

.213

NG PROPOSAL

HITE Z

,926* 80.2

539 55.L

r 450 6? c5

556 75.9

r 30 I 55.2

943 5[ '0369 54c7

293 60.'l

654 52.9

980 75.O

r I6.1 69 .2

r 966 66. I

r831 62.I

t 517 82.9

rg6I 64.1

r407 68.6

SENATE REDISTR ICT I

TOhNSHTP TOTAL I{

BETHEL TOHNSHIP -.31650 _-2

CENTRAL TOHNSHIP 978

COLLY TOI{NSHIP 2Tl_2O 1

. CYPRESS CREEK TOI.,INSH 733

ELI ZABETHTOI,{N TOI{NSH 5 ]978 3

HOLLO|{ TOWNSHIP Ir848- _.

LAKE CREEK TOWNSHIP 675

. ._ TURNBULL TOI.INSHIP 4A3 -

HHITE OAK TOWNSHIP Lt?37

BEAVER DAr't T0WNSHIP Ir30?

CEDAR CREEK TOI{NSHIP 81910 6

EASTOYER TOI{NSHIP 7 I5I5 4

GRAYS CREEK TOWNSHIP ?t948 I

ROCKFISH TOWNSHIP 26tO42 ZL

ALL 0F C0UNTY +91687 3l

T TOTAL ll4r3tl 78

DEVIAT ION- .02826

o/o8/82

COUNTY .

C OUNT Y

C OUNT Y

C OUNT Y

C OUNT Y

C OUNI Y ..

C OUNTY

C OUNT Y

C OUNT Y

AND COUNTY

AND COUNTY

AND COUNTY

ANO COUNTY

AND COUNTY

COUNTY

OI STRI C

ORS- }

TED- I

OUNTY

LAOEN

LAOEN

LAOEN

LAOEN

LADEN

LAOEN

LADEN

LAOEN

LADEN

UMBER L

UII'IBERL

UMBERI

UMBER L

UMBERL

A HPSON

SENAi

PAGE

OTHER

RIN

c

-_-B

B

B

-B

B

.B

B

B

B

c

c

c

c

-c

s

OF

DATE P

CODE :I

-/ottototlA or?o30

.:L _ \01?035

[.'.J (orzo.'o

l..l lorzo+s

l:l-l-orzoss'!) /- o l?o6o

l'|{ --orzoos

;-l- \01?070

i'1- -{orroot

;' I rP5ro2o

irl_ p5r030

l''l ,Os rors

r:i- -(g5ro50,'li l63ooo

!, - rl''l--.--

i''l lro

t-F-.-

l,."I -_ NUI,IBER

lr ,l

t--F---.----- -

r"! _ _ _

llrr l ----" 'ii_

I i. ,i

L.l

---*

l,l

)1,,1--

l,'

lr,i,

'.i

L-- r I-

4 - .ri-

3 .l

INDIAN Z ASIANPI

ll --- .3 L-=---tl ---

L4 .2

BLAC K

-,. 70 9

+15

840

I75

2t641

Be3

30I

I90

582

126

2t414

2t)ZL

Ir050

3r171

16r735

32rBl5

z

- -1.9 r4

41 o5

3o.?

?3 t9

44.2

48r3

44.6

39r3

47 oL

?4.9

27 .1

30.g

36.0

L2.2

33.1

?8 t7

I

?98

?08

4I

694

888

.l

3r3

?.8

1.4

2.7

I.8

1

l0

?

335

34

-rl.I

I.3

.I

.5

Io

I4

_ - -__10

L4

?65 --

169

110

.3

?L91 r.g 19e .4 493

)'

I

).,-t,

ti

l,{)Li*-

DATE PRINTED- IO/O8/82 SENATE REDISTRICTING PROPOSAL

CODE # COUNTY TO!.JNSH I p TOTAL wH ITE Z

ot7o05 _aLA0EN_COUNTY ABBOTTS TO!{NSHIP _,__-

BLACK Z INDIAN X ASIANPT Z OTHER

PAGE 1 1

.DTTOTA BLADEN COUNTY

Ir031 - --.- - 153--.?1.0l -ul,rula trLAutsN LUUNI y BLADENBORo T0HNSHIP 4tg47 3rg76 g0.4

:i +l]919 !LA9INcouNTy BRowNMARsHToHNsHTp ztozl rr238 5r.r

_ ;xH;I-!^[il,,l'luiili[ i:3;3 1,1,r? i]:l 770 39.0 ._.5 .3 ...-. . IO .5 5 .3

11457- 72.9 _ ?0O 10-.0 l___r*1.452 47.9 4 .4 8 .9

LAKVEK> LKbEK I UWIISH I 1999 341 _ lZ. t

FRENCHS CREEK Tot{^lSH 947 _ 479 50.8

._l__ <rvr r v(t .. DLAutrt\ LUUN I Y

I j-- /olzo25 BLADEN couNTy _

!l ( olzo5o BLAoEN couNTy:l ( 017050 BLAoEN C0UNTY:: \otzozs Rr^nEN rn,rrrv:J-. \OI7O75 BLAOEN COUNTY --hIHITET.CREEK TOI{NsHI - I 1641 ,rt \".t OI9OOO BR.uNSL/If K f nllNTv Ar r r.E rnr rr,?v'.1 0t90o0 BRUNST'IICK couNTy ALL 0F couNTy 35 t777 zt t z|t 26.3li orzooo coLulrBus couNTy , . ---aLL oF couNTy - 5 r r0-i7 34t4o6 67.4]l l29ooo NEH HANovER couNTy ALL oF couNTy l03r47l 801353 77.7'i l4looo PENDER couNTy ALL oF rnrNTv ))^)1q 11 car tAI rlrruuu !,ENUEB LouNTy ALL 0F _COUNTY _ 22t2L5 - L3r 531 60rg

:l

';. luraER oF SENATORS- ?*i ---- 'rErrr''' unr- c DEV IAT I0N- .Q*327=

48? 29 04 lrll5 -68r0

----44

_2.7

8t287 23 c?

L5 t394 -. 30.2

22t37 I 21.6

.--lt3-..3 -- 60 .?

--1175 --2.3 -,.,--, 36 --,rl260 .3 3II -.3

36 .l

-__J

176 - :?8t6?3 38rB . - ?1____tl. ____ l9_____?I_ _ 18 a

59 r7O7 _ ?6. U.

.**,8?5

_. : --z?3 .l

OATE PRII,ITED- IOIOS/82 SENATE REDI STR ICTING PROPOSAL PAGE 12cooE # c out{TY rowNsHtP TOTAL }.HITE T BLACK i INOIAN Z ASIANPI Z OTHER Zqq 0ra.rt uHEERLAND c ouNr y. _4s..s.f - r.uFaE(LnNu ,I.uuNt y . . . _._ BLACK RTVER TOI{NSHIp_ _.?tZle -*__ lr i45 58.1

ffilH)iliiEiiiiliiililil

,

fllii:i,iii:r,iruur riiiii- - ri;;ii iits- ,r:iii-ii,i-lii ,:i ::i-_,:i _,:i-:iv,ruzz <cUMBERL^N0 couNTy cnoss iniei"io{Ni;ie ;;;jii j;;#; iili ailil! iB:3,_, }ll- :i .:ilil.:if;;ifIF.. )1f )vt

*:llig f:IIpS*5+Ip ggyllI _ iirrixelrrn ror.lNSHrp 37,5zo

$ilffi;-\XliEli^l3,i?v'T, , - i:ytfly=rriir iiiriri* or,9i1 - _ ;i;;;; il:; r2,o78.32,5 __oso _r.o

-,li; ,ii ;j:l_-:$simrr nan,iiii iduriii iiiitti.fffii[,I8,*' ::iii z::gz i3:i 'i::i; i;ii _.,:i ,'i; _,_ii:i:J '?3!:ilf085030 HARNETT couNry DU(E roxNsHrp- " :;ii; - ;;;.; ;6:; 468 8.5 6r r.r z ..--0!.t04 l. jrRNETr cour.rry lonrsorrvrlfi.Tor,NsHI zfit4 i;;;; ;;:i .. Ez8 3z.z -_ L6 .5 _r7 i 8 _ .3 _ _005060 HARNETT couNry srerrrnrs-iiiei-iri,riii z,soi i:o;i ;;:; rr?32 60.5 ro5 3.? 3 .r!.65o65-.xABNEIIcoUNTY.__.UPPEB.r.rriir-crved.-i,.4l6+4.l,rsr.lz.+_.Lta4)?2$.--6.l2

*leiiN;ffiElllffi ;SUilll- - ;E$:ii;-llki,'?#:ll :::z:i

ll]":" ". ..,,._^^-ortl"t..

rorl z2s.ea5 r*r,eoe 62.8 7z,zoz zz.o Jotz_ r.r_ jrss i.z :loa_z,rl_-. -uunEEfl._oF.. sEua ToRs- 2

l, ol

l,,l(ll

lr 6l

t -i

irrl

ti(

H

[,ll

I.^l

t1

OATE PRINTED- LOIOS/8z SEN TE REOISTRICTING PROPOSAL

PAGE

COOE # COUNTY TOUIISHIP TOTAL IIHITE T BLAC( I INOIAN I ASIANPI T OTHER

t3

oaso I oaiARNFrf-C-out{tY- --- !yE!AS8OR[ rruttsttrl-. r 1.r! 25- e t24t-"7or4__-_-1r66]_2rr9_-J59__-]d__-__l! .2

ffiiilitilEii_33Ufi#___:---e1aei-nrvendil,,iHr;- ris-ii--_-i,i;i_;;:;--,_- e1r-le.?*__.r__.2.__.4_rr--ormrr-Sfii,iiii :;;ljii _ - "____py:I:01*..I9.,l,rslrrp . , rrto3_ * ::_;;6_ ;i:; r5E rj.2 4 -,.fiitfiJiiflEI++8ilHL-: ---crovL iorrriiiri":r -;;iE-_ - __+;trii_illi, _--- i!i__i3:i- ,l-:+- irii --oi:oio(iliilEiij;Iiiii--- -- Iifl?ff,:l'SLlor.tst- r.zoi'-- _-lirii - ;;:;-. - 3,0 -r8r2-- r .s--

.{AKF {truNru .l--- -

_-

_- ili.;i :ffi,ii'Ill:1-.1:i:L--_-rril 3ll i2.3

919 --1e '6 ?4----po 2-- -;-i

80 5 _.. 18 . l-.'- ,2O__ ! 5_ r s-. j

"6"unl{tt nNErI-fouxTY

-LILLrf{crsH

roHr{iiri_.. _i,oii - _2iiii Zii'- rru rE.z s -.3_--.-_. __

-+l!.955.

)IARNE TT..couNTY .-.. __NErrLs cr r'er

-iijiiii

n r 4.456 1-r72 a,,, t- --- I'::9 -?q.a-?1--._:ft;iii-c*'EeiTfii[ifrr-i:H:---i:Iil-li:9----r,ezo -rs,a_]l1 .e z,

_=;_ _-__- ____ _

-]:

* *-"..-- -.--ur.rrzr-.- -_zf r!551 __75.9 _.- _..h5ti5.2 ff.a lff---ra _il;i6 ;;--__X

Tl=--.-----orsr:f,r-'o'1l -.:_ ,.- -l-_i 33'.35r- 26?123,--.76r?--13rrLr_-zl.,e-::z-l.i-ji_or_-,r__-rrq

DATE PRINTEO- LO/OE/82

SENATE REOISTRICTING PROPOSAL

P^6E

::::": ::::rl^ .-

rorNsHrp ror^L xHrTE r BLA.K r rNDr^r{ I ^sraNpr r orHER

Hffi ryil.'--:i^tifif; Uilfl --,_-.f,T,Ho:fili:L=il;', j:EL*-;{t+i;:--i-;i--*-,?Z

l/i

I

o3

OATE PRINTED- IO/O8/82

SEI{ATE REO!STRICTtl{G PROPOS^L

COOE

'

COUI{TY PAGETOI{I{SHI P TOTAL IHrrE I aLAC( ? rN^rrrr

l5

t

J__l4 o-z q Z__?_Ql.-----rl- __?J *.-2:ro

Yt

l

)

)

ri

t"

---

,- r.,tr_!.!:r:

+,, ., .'r{i*r."l

. e. , .-ir*.

-r.u":f*",,fi#it

r*'

L*"-_

OATE PRINTEO- IO|OATA2 SENATE REOISTRICTING PROPOSAL

COOE

'

COUNTY TOTNSHIP

PAGE

^1i^^- ,.-.-.-.. -

rurN)nrP TorAL t{HrrE l BLAC( r INoraN r asIANpr r orHERffi trtrffi iljHif"ffi fl t#f ilH,*-;iHii+F---e:#.:+--c-..!r

m[;iry,ffi itr--=ff iil:ft i$Fi:=li$=iii-[F,* jil_ii,*E#

::l_^__l_--_-_:

-frt5i2-

85!72i---t.t,s-- . ia*o: zrJ irs-.i-- zzo_Jz_

i-

16

z

I

l;;---

qi.=- --

ffi[:-

ry.-:,*

OATE PRINTEO- IO/O8/A2 SENATE REOTSTRICTING PROPOS^L P^GE 17c00E f couNTY rolNsHtP TorAL THITE t BLA.( r r*olAr{ i AsIlNpI t orH€R z

iliiffi.3r#Il__jit_lE f,ourrr .___-'Je,ri_re__.rerzz)_a9ra. _ __r?rr j

-c^s*ELL .o,Nrv . tl,.gv.en r-onnii1r _f.i'Iiii -,_-._rr757 6eoe- ,.3-]3:*-..1-:l t og-.i?-r2? .r

;nrp- -i ]6ii--- --- ^' +i{ 31:ZA SLIFI I l. nl lNTv

="nii+iiftiifi;irii--:--ilfiUiiiffE-I3il#i,-i:3li_ ._l;li_lii:_ -_r.iiii;il_I===t_:_-F+

*1-. --= --fll*rcifri&:- -..=

-*"-'

--- --uz'ari --- sr.is6-ja.r--.-j+',r+*a;-,'{:-ir.---uf-iz- - rio-ji-' rrrrRFe-nF aFlrrnnl:_l_,.. .. ___IIEyIALI0L_- _.!a220: __*_-

.SBELL-couNry,-

--- ioCuii iir.i-i_tii;,i;;,tp--__ii6ii- _ -___ "iil iii7 .. ,,li:" zz:i - -r J,__i _;-t_=:==AsxELt._cour,rry perHrc.Tor[sHri -- .. -;:;;i

._

....2t46r _7).e _ .._. o62 25.e ^

_ ---r_:r_

l:l ii:IXXII __ _ :l3l:_glFFlriifu:llr __ii;ii _.__,,?ei 67.e _._ ar: rz.o____ .,-- i--=-

DATE PRINTED- LO/08/82

CODE i' COUNTY

SENATE REDISTRICTING PROPOSAL

BLACK Z INDIAN

PAGE

Z ASIANPI Z OTHER

I

.l

TOt{NSHI P

18

tTOTAL I{HITE :

oo CHATHAtr-IQIIIIJ_ t!! gE ro. uxry 33.+15 2413_16_?219_

BB-*f EREl5lll_w-r_: _ il_t :F r. :,r,f * :firt _B__ ? e, le! *,,.,_ _ _ BSB I -*il# -Zi-jr" i . Hs_.tteqtE-ra!!,rrr.:_:=it_orisiilri______ioi;,6i--:5jilii_,i",its_::l8illi.:.ft_t:i:il_'.:r_ii-f-ii

'a".,..3.1

.F i+Ilrt;f-,

.4 '*. gar.i- .+.!-.;-::lF s4|;a

7 * **-:rS

, i OriE PRII{TEo- Lo/oB/aZ ----- .

"ll1 SENATE REDTSTRICTTNG pRoposaL

';' CoDE ! couitTy ToflNsHIp PAGE 19

9,'"ooroon

^r(.rr .6,,r,?,

Toral rHrrE t ELAcx t INorat{ r Asrarrrpl ? orHFe ,i

'i,iii :ri:---J-:-:+i

{tniF*r,rhitili=iiiinliit_ -

ii ifri -: iii [t- iiii- :,i i lf iiil+1i==F',,-fi__ . r-.--'"'--L' *_ ^,rilcoumy__ _-ro,ra'r_rfi;i;i__;;:; - -.iiiii__ii:i_rlj:i_:l3i!_,sl

:j"-:-=IsdEI-ioui:-':'...._._*'i+q.zac--]*ia'z'r:c.tt,.t--..-.se.{,s._!i..-_.;;;:-.riuraer.or.seruU$:'.2'__--']-....].'1n4t55a74l1*_.-ss,lts_l.i.c--1a%

_,__ . ___ l)EVrArroli__-_-ororr

-

._--

- " l- .-- I

DATE PRTNTED- LO/O8/82

CODE i' COUNTY

SENATE REDISTRICTING PROPOSAL

TOTAL WHITE Z Z INDIAN 96 ASIANPI

PAGE

Z OTHER

-_ _I

20

tTOI.INSHI P

ERUCE TOI{NSHJP a t E7 h

- -.---9 t 664 _ _9, c ?__ _-. .-- 4 2-o--_-=r0-_---r2-.--5--r 1.---_2

...-._ 6.2 . _ _ 10 -, _. t 41 .5 19

23.\

CENTER GROVE TOt{NSHI

0EEP RIVER TowNSHIP

FRIENDSHIP TOWNSHTP

JEFFERSON TOWNSHIP

MADI SON .TOI{NSHI P

HONROE TOWNSHIP

- I.IOREHEAD TOWNSHIP

OAK RIDGE TOHNSHJP

RCCK CREEK TOWNSHIP

hASHINGTON TOWNSHIP

ALL OF CQIJNTY

8r?78

4t114

11r647

10r295

3r308

7 t35+

I02r082

3r843

5r365 -I rq44

81 t4Zb

7t697 93r0

3r890 93.9

LOt574 90.9

7r8ll 75.9

3t 431 89.4

4t238 79.0

L r734 89.2

-65r995 79.I

BLACK

. I95

51t

239

912

2t379

2t129 70.4 967

6r059 82.5 1r258 17.I I I .2 .l ll

84t89?- _83.2 .. L5t726 I 5 .4 ____ . 610 .6 541 .5 - '30?

381 9.9 14 .4 . -_7 .2

OOO --.ROCKI I{GHAH C OUNTY_ 17r186. -20!6 *-----68 . I _ *_-*4_9__.__ .. l.- __ _128 .2

__.UIII{BER OF .SENATORS- 2

51 t4 23

lJ6

SENATE REOISTRICTING PROPOSAL

COOE # COUNTY

TONNSHT P PAGE 2LTOTAL THIrE I OI 'A-

;l,lii.-.l,iii,if*-- l=ii-*----=; *j:--:iII

pryffiIfril=trffi{fr*i *'l# +t-' :*ii{=*==i=J-=ffi-- - -- - - ..- orsrnrcr rorer- , -- --*' ''',z4-- -Q5tt'2--'e)'2-- -:J:r --i'i-:;,i-li--tji:-ji--ii3-:]

OATE PRINTEO- LO/O8/82

COOE # COUNTY

SENATE REDISTRICTING PROPOSAL

TOTAL I{H I TE ELAC K Z INDIAN U ASIANPI

Ylll-l,OllNLY-___ aLL oE_ courIIJ__ _241t681 r a z r 642 Z5.rO.

-gP_-!-3-_?!1:11fi-{1=::--:-'--- - - -- ._:qii-oar---l- i-st,6+r *-rj.o *- ir,1o-3-2a-;----.gra- .. !---i-oo--Ti-s:

TO}INSH I P

PAGE

OTHER

22

t

I----l--

l.---

F--_-

ii3,?_ _'_--

,'trr ip:i,.,

R OTTE

r*t

CODE, :,

PRINTED- IO/O8/82

g COUNTY TOI{NSH T P

SENATE REDISTRICTING PROPOSAL

TOTAL. I{HITE T

PAGE

BLACK Z INDIAN TASIANPI Z OTHER

23

z

ilr{F

i

i.

ry

DATE PRINTEO- IO/OA/ 82

SEIiIATE RFI!r<To r

. TOI{ilsHIP ,n?.r PAGE

o5?non nrvrn<n^r .^,,r,rv

Total tHtrE I orlcr t ,!^r.^.

z1

t

o

l-'. --

l-_.

0^TE pR TNTEO_ ro/o8/82 __==-__ -_-l__l

cooE

'

couNTy sEN^rE REOTSTRTCTING pRopos^L

T0I{NSHIP rorlL xHrrE l BLA.

PAGE 2

K I IT{OIAIiI I ASIANPI T OTHER Iflilfl..'i'fff}.,1*': -ffi*"; .fooilili_ _, *.3*:ii---;*Hr- 9 J.f _, 1!,rer_r{iz__,r, - 2, ao

--:::;;,.cr;irrl:-l_'lll,1_.

-

-'-.0*lr1o_: -

arr.+,.ir_--,iiii* tff:58i*:!=iirr::.F..lfl___:_*^+...-

6;"I=I=:i:i:]t --'-------:-,- .--,rco,-ror- - -rr+,zar. *.. -l ,,"-,^r-+;:jl':--et--28-or - at-fIeii;F5::=i$] =--n;""1'ErrT,l-t---::ir";."ila=i:1+"-=;;=ffiHE

, 0ArE PRIi{TED- tolos/82

SEN^TE REOISTRICTING PROPOS^L

PAGE 26coDE g coua{TY ro}lNsHlp TorAL rHtrE t BLAC|( r rNnr^ir_ BLAC( I Iiiollt{ : ASIANPI t OTHER I .;ffiffi ih@i=Jiii-,#Ii:.I:iiffi :Tii.*,tr=i,i-+=,==ii+#S

'%

I DATE PRINTED- LO/08/82

COOE iI C OUNTY

SENATE REDISTRICTING PROPOSALo

*9fggo cLEvELANo. couNr-Y.-_orlooo._ cAsroN couiliv-'' -

TOWNSHI P

.ALL .OF COUNTY

ALL OF COUNTY

rOTAL

TOTAL

.- Blr435

l62r56B

-2+6r003

DEV I A I.tON-_ _-__..0 45 62

WHITE Z

65r803 -_ 78.9l4lr827 A7.z

2O7 t610 84.1

l7r40O -_20r9re;d;; ;;:; ??i _

- :i

37 t Z6E I 5.2 -

3?r -___. r

ELACK Z INOIAN U ASIANPI

PAGE

Z OTHER

l9l -- rL---- 6e---::j9 .Z ,O-

4+O - ,Z _ *tr+l :_,

o-

.),lt*

.*lt

*-* "ieir .,;;;,1fi6!

"r- .+,sg+#(,

rru

t

o

OATE PRINTEO- IO/O8/82

cooE , coutry SEN^TE REDISTRICTING pRoposAL

TOlt{sHIP rot^r PAGEoosoo^ r, TOrAL xHtrE , -..-.-

+O

(3

9

:io

o

o "..&ri

t

o

D^TE PRINTEO- IO/OA/ 62

SENATE REOtSTRICTING PROPOS^L

PAGE

::::": :::l::nFr .nrffrv ]:*::,:

roral rHrTE I 8L^cK I rror^r{ I AsIr pr I orHER'o ffiiiiiEIilii"=-#iii-ii#iiiii:---,l.fi3.f{,:::i3=,?I

-__._.95 _ .l

--r

2-..-9Q ^r,.roQo_-surxinFoaq-i0uni;-._-lii

-EI- iEUiliI _ -__- il:itl _ -: 2i:13; - ?i:I:-- ;:;!i6t55O

*

12.2- - .o <t--

--.-.{7-r

!-0 ? - 87 .6

_-_-_ -,: _

_- -

1: :

-

__1.' : _. _:.r,

aa.r*rr r.-__ ?3e.*_.,c -r---1s+___, 1::=!_

-DEYIATION: -*.OO?76-. -uEytAt IUN: -* .00?76_

a

a

.-_.1

I

DATE PRINTED- LO/O8/82

CODE S COUNTY TOI{NSHI P

SENATE REDISTRICTING PROPOSAL

TOTAL I{HITE Z BLACK U INOIAN U ASIANPI

PAGE

OTHER

'30

z

ALL OF_COUNTY l5or9l4 14q..99O I,QrL 13.99_7__At? ?99 ..2. t llooo TCOOXELI*-COUI{II-,-----------ILL-IIF COU f Y ,-- -- ,-15d-35 illr tl5-15.1 I t149 -,L c.+ 3! .f--??-,-j? -,-,-, t

_. J.ta Qr soN_. IouN.T Y -_ -lLL- OF.-C.OUNTY.-- ---1,6.r 12?----15 r 64Q- -9-8r 9

--.

..- j.?.5---lE-17-c2 -8,-: I

oo l,lrTcl{ELL c0uNlI_ at-IltFJouNI y____ t 4r(28 14r 351_j9r5____l8 .r 21 .2 23 .2 l2

NCELC0UIIIIY.,, -.--.'--.-.-- -. ILL-0F--GOUUf Y-..-.--.-I4t91a r*r.10 L-- 98 r,4.*-19.?- 1.3 2I .1 9 r=l 6

DI.iI8'LC1..-IOIAL--- *. *----? 4? r?58'.-..-*225 &91 9?.2

---.

l-2rB9a---4.0

-t!l -!?

441 --rZ

406

-. ..l)EVLATLON: --- r02970

.2

--{)

DATE PRINIEO- LO/OA/Az SENATE REDTSTRICTING PROPOSAL PAGE 3I

c.DE t'} c.uNTY ToxNsHIP TorAL ,HITE ? BLA.K E IN'IAN t AsrANpr u orHER r

:3:::3 _il:Ig:llo};Lgy3ry ._ 11! of couNry . 5 8 r 580 _56t 22b e6. o

::::l:(.ll:I:gM:1lI crHaoa ronrinri-""- 4:z5 424 ee.B r ,,?!91:\_lrcrsoN couNTy cANEy FoRK rotrNsHrp

1.-) .t(.t y,to6 I .Z605 598 98.8 I -2 c -a

.2

lsr-

lb

__ 099020 \JAcKS0N C0UNTY

-- O99O2S Itark(nN rnnrrYv---.099025 IIACKSON TOUNTY -.-.CULLOI.IHEE TOHNSHIP . 5,;;io99o3o /,lacKsoN couNTy Drrrs,Frnen rn'rNeuro r nz^

)ao yoou - I oZ 5 _cg _ __929 99.6

. - jt6o6

-- 94 t? -zsg

-h

cB *- z? c4 26 -

-

- ---

-- i -- ift-- cAsHrERs ronrviiii-' iIi ;;; ;;:: .1 . .z - 5 ,B -- 1--.A--

-.099035 -Hac KsoN cou*Ty -. .. ...GREENS cREEK ToriNsHL58. _ -.ia: gg.e ... .. I .z,-.099040JAcKsoNc0UNTYHABURGToHNsHlPIr023r,oilsi.z1!I7.7._-_.

-*:_*:: l1!5:gl! lggNII nouNrAr N ror{NsHrp 23, - 2a4 ee -A234 99.6__099055 /JACKSON COUNTY lly!1. I9x!!!1rf aoo . -- ;;d ;;:; 6 .g --- -r --, ., --.- -,--.--- l--*{::I1! /JAlKsoN couNry SAVANNAH ror{NsHrp 908 882 97.1 ?o )-) a I099065 / JACKSON COUNTY SCOTT CREEK TOl.lNSHIP I r476 -e0- 0es065 / .trcxsor.r courry scorr CREEK rowNsHrp y1;Z- - ,,i: ;;:; ,o ,.,

_. _ ,1 Zil -* _._ r-- ...r _,_-r_!r_

--i;iifiqi:r:8i:Bxri i!ir,i;iri*i;;1

' r:a# r!;r: :ji: ,,: 3.? - t-.e --r .z,--c-;,-

I 7(^^^ rD rr,.vr

.1. _. )+ .a - 26 _--rl ___

-

O3I ,. OISTRICT TOrAL . ll6,e6e .. ..lrr,3ro e5.z s,otz - i.t" _z7s

_

,i_- jas- .j rir__.r=.-.

--_03r

-iVIATI0N: ..00r56_

:l

:l

l

'l

lr

l-r

Iii

DATE PRINTEO- LO/O8/82 SENATE REOISTRICTING PROPOsAL PAGE 32

::::": :::::l__ ,

roxNs*rp ror^L HH,TE I

'L^cK r rNDraN r

^sr^Npr r .THER rffiffiiffii LiffiH

ffi ffiiffi itllrF=*:ii=jtlqi[5--j,5ffii,1tsffi frsryst==iHr-f 8uH,._ j3r};=,_=;+i!jl:!-__13;=#"#=ia=;=

_--..:=;:i_ll1l]l__.---_-_-.'.1,,'u'E----._lQ6rl19.gs.i---ri6a?

--'---- DE-v-IAf LQN:- --.rQ347a-

DATE PRINTED. LO/08/82

COOE iI COUNTY TO[{NSHI P

SENATE REOISTRICTING PROPOSAL

TOTAL I{H ITE IND IAN Z ASIANPI

PAGE t3

OTHER tBLACK

,

,

i'

t

D]

'lfl

Fr nFr<EirrnQs- to -

- -----if;i;- iorels. iii.roa- -r'*sa,oral:.a' i,i r ra,Tir1-ze-i;1oiaiill'-zir aa .+ rr

I8ICT.S*IN. ER80R=-*-

TRICf -JIUH8€RS=---

)

a

)