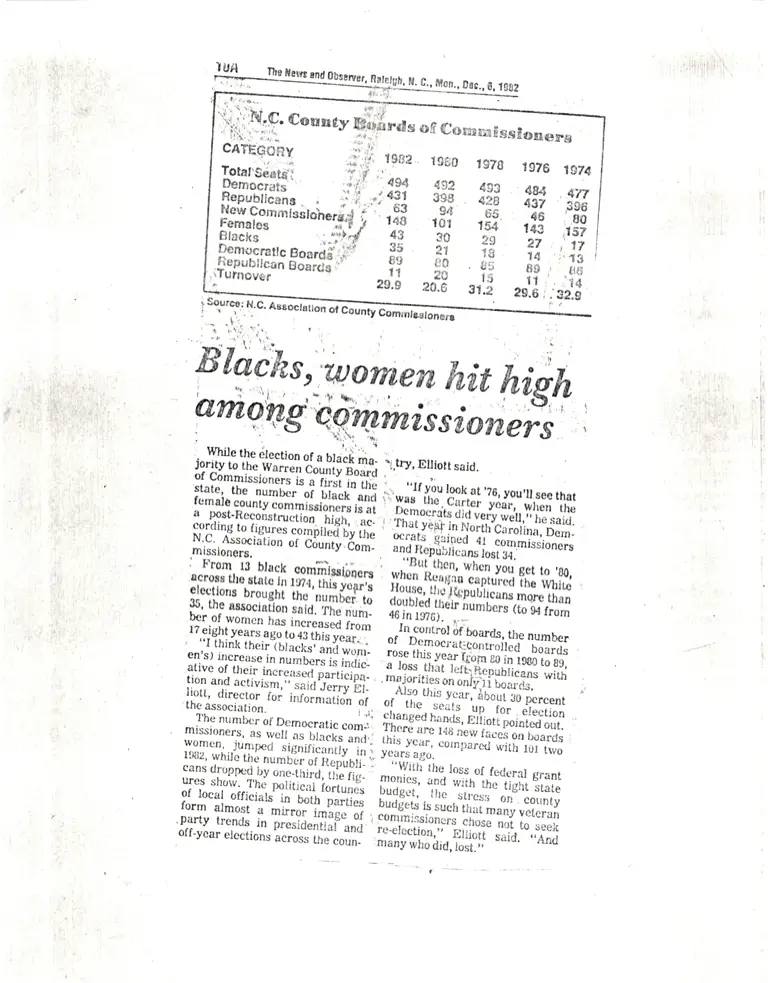

Blacks, Women Hit High Among Commissioners News Clipping

Press

December 6, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Blacks, Women Hit High Among Commissioners News Clipping, 1982. 66b65aa8-e092-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1fb346b1-2782-4ba0-9444-f8261495ce54/blacks-women-hit-high-among-commissioners-news-clipping. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IUA

CATEQOEY rg8z r9g0

i4,

398

g4

1 Clt

30

2't

{j0

20

?,0.a

1S7B

403

428

ri5

154

t, Ll

1S

,85

t5

3t.e

f976 1S74

484 ,L-fl437 39546 .' Bo143 ,,t57

27 itt14 ;'13

80 {t{;

,rll ,.'rr1$

**t$",r-m*l,Ti*,'^ll :. t;l*[,i,.-,ffi;l:ifi x,f"lid

Irg: : E: t"'fl i;;"f"'r til ".'r

ul ii', " ffi'{".H,i#;P :ffi'I?*#*',X;

.missioneri.

s!,vr. ur Urrunty.Corn. and I

. !'rom t3 btack c. ''i. '| ' , "B

rcpu;ltcans lost 34'

fl'.ffiffi 'f'I,ffii:, fi'*fiilq*f*flffi.H#

ifft{laulu*t}*n[ **ffi,:**u

fiff #:i,.:q,;ilTf#;,itil['t-'1]!I",iix1l.'",]i,ri'J#i';S,*",

;Iliffi tt"Jlf

TT,11,1,I.#fi

.,[t,f,rlji,,;#H,{i:*ffi

itii r"l l

=

- i* j t*i,,. i## i, #l r, :'::"'.: ::

-1,'

:,

t

.131_'

dlrprog t v "r"-ii,ri',r:iji'""fl;.

, ,,^Yjl" ltl, t"*. or reduar sranr

f*"ti:;ll.lry,fitiJlffi m*;,jrl":* ., -iff

x,il,;.H$,ft 1*[{"ffi

,

}*ffi1;;}l$r*,plxi