Order

Public Court Documents

November 19, 1981

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Williams. Order, 1981. 28f6af13-da92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2023b6b7-fcbe-4b25-911a-458dadab006d/order. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

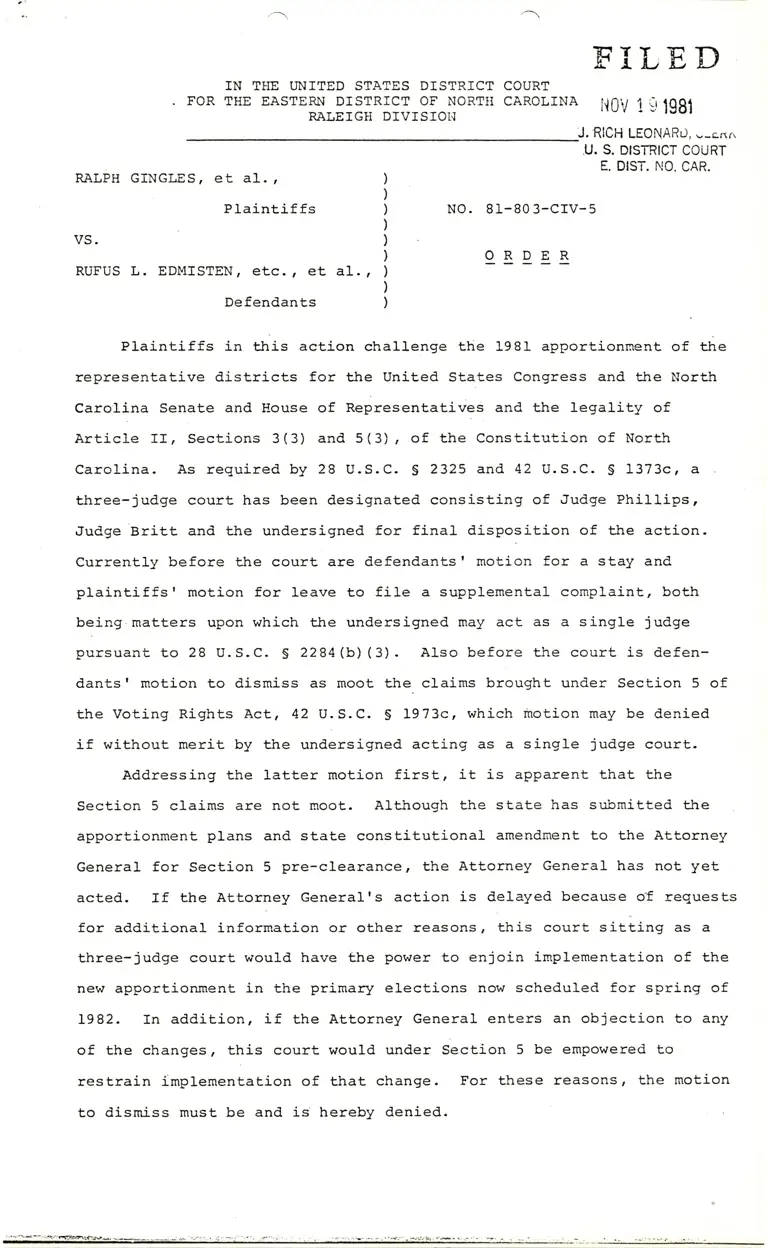

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTII

RALEIG}I DIVISIOI.]

RALPH G]NGLES, et al.,

Plainti.f fs

vs.

RUFUS L. EDMISTEN, etc., et al.

U. S. DISTRICT COURT

E. DIST. NO. CAR.

NO. 8I-803-CrV-5

qE9EE

)

)

)

)

)

)

,)

)

)Defendants

Plaintiffs in this action challenge the 1981 apportionment of the

representative districts for the United States Congress and tlre North

Carolina Senate and House of Representatives and the legality of

Article II, Sections 3(3) and 5(3), of the Constitution of North

Carolina. As required by 28 U.S.C. S 2325 and 42 U.S.C. S 1373c, a

three-judge court has been designated consisting of Judge PhiIlips,

Jud.ge Britt and the undersigned for final disposition of the action.

Currently before the court are defend,ants' motion for a stay and,

plaintiffs' motion for leave to file a supplemental complaint, both

being matters upon which the undersigned, may act as a single jud,ge

pursuant to 28 U.S.C- S 2284(b)(3). Also before the court is defen-

dants I motion to dismiss as moot the. claims brought under Section 5 of

the Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. S 1973c, which motion may be denied

if without merit by the undersigned acting as a single judge court.

Addressing the latter motj-on first, it is aPparent that the

Section 5 claj-ms are not moot. Although the state has submitted. tl.e

apportionment plans and state constitutional amendment to the Attorney

General for Section 5 pre-clearance, the Attorney General has not yet

acted. Lf the Attorney Generalrs action is delayed because of requests

for ad.ditional inforrnation or other reasons, this court sitting as a

three-judge court would have the power to enjoin implementation of the

new apportionment in the primary elections now scheduled for spring of

L982. In addition, if the Attorney General enters an objection to any

of the changes, this court would under Section 5 be empowered to

restrain implementation of that change. For these reasons, the motion

to disrnlss must be and is hereby denied

F'iLE D

COURT

CARoLTNA NOV 1

._.r lggl

J. RICH LEONARD, v-c.rlr\

Arguing for a stay of the proceedings pending the Attorney

General's'action, defendants accurately contend that this court. should

not adjudicate the constitutional questions raised before the Attorney

General acts . E. g. , l,lcDaniel v. Sanchez , U. S. , I01 S.Ct.

2224, 2236-37 (7981). Nevertheless, the imminence of the spring

primaries requires that the action be heard on the merits as expe-

ditiously as possible after the Attorney Genera]'s action. A dis-

covery deadline of February 19, 1982 has been established. $Ihile the

court will not address the merits of the action prior to the At'torney

Generalrs action, the stay must be denied in order to permit full

preparation of the case for expeditious ad.judication.

Subsequent to the filing of the complaint on September 16, 1981,

the North Carolini General Assembly met in special session and repealed

the Ju1y, 1981 apportionment las.r for the North Carolina House of

Representatives, adopting yet another apportionment plan for that

body. plaintiffs have moved to file a supplement to the complaint,

setting forth allegations which refer to the new apportionment adopted

on October 30, 198I. This motion is al-}owed. F. R. Civ. P. 15 (d) .

Defendants are directed to file responsive pleadings to the original

complaint and supplemental cor.rplaint within twenty d.ays of this date.

SO ORDERED.

JR.

DISTRICT JUDGE

November 19, 1981.

r certify th3 f",...lo^liJ: ff;ilji:",n I ccriect coPY ol

"' i ni.n Leonard' clerx -

'.ffi ;ir* District cor-rrt

Eastern District of Nonn Carolina

,r-:o*5#;gi;;;

F. T. DUPREE,

I'NITED STATES

Page 2