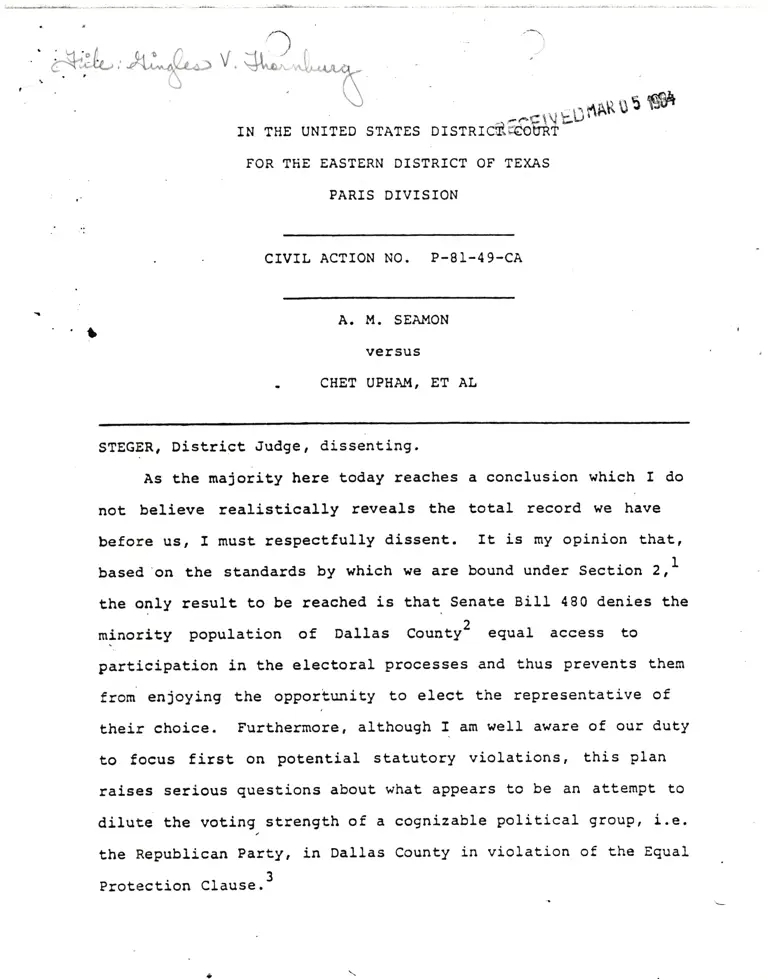

Seamon v. Upham Dissenting Opinion

Public Court Documents

March 5, 1984

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Schnapper. Seamon v. Upham Dissenting Opinion, 1984. 74f88294-e292-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/204ef694-611a-421d-954a-70e478d5cf26/seamon-v-upham-dissenting-opinion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

A;"Li-) V.

L\

.., )

-\

)

i[*: ,',,,\At+-

/t., \\.J

'- -Fr'\\ Lll flAR 10 5

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICBTEOtrRT

FOR TTiE EASTERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS

't

PARIS DIVISION

CIVIL ACTION NO. P-8}-49-CA

A. I{. SEA}ION

versus

CHET UPHA.!{, ET AL

STEGER, District Judge, dissenting.

As the majority here today reaches a conclusj.on which I do

not believe realistically reveals the total record $re have

before usr I must resPectfully dissent. It is my opinion that,

based 'on the standards by which we are bound under Section 2 rL

the only result Eo be reached is that, Senate Bill 480 denies the

minority population of Dallas County2 equal access to

participation in t,he electoral processes and thus prevents them

from enjoying t,he opportunity to elect the rePresentative of

their choice. Furthermore, although I. am well aware of our duty

to focus first on potential statutory violations, this plan

raises seri,ous questions about what aPpears to be an attempt to

dilute the voting, strength of a cognizable political grouP, i.e.

the Republican Part,y, in Dallas County in violation of the Equal

Protection clause.3

)

I.

In regard to the claims concerning Section 2,4 there seems

to be some confusion as to what the National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Republican Party

of Texas (Republicans) seek to accomPlish through this lawsuit.

,From an examination of t,he allegations and assertions in their

pleadings, as well as the evidence and arguments presented at

the November 30 hearing, it seems clear that they are not

lseeking a plan that would guarantee the election of a black,

Hispanic, or Republican congressman from one of the DaIIas

County districtS. Indeed, such a "guarant€€," as they well

recognize, has been held numerous times not, to faII within the

purvlew of either Section 2 or t,he Pourteenth or Fifteenth

Amendments. Nor does it aPPear that either party asserts the

right to proPortional rePresentation.5 As Congress has

specifically expressed in the language of the statute, the right

of a particular racial, ethnic, religious or political grouP to

be represented ln proportion to their.presence in the population

has no statutorY basis.6

It appears that the. sole PurPose of their attack on S.B.

480 is to insure equal opportunities (not only in the primaries,

but, also in thq general elections) to participate in the

political process leading toward the election of the candidate

of their choice and not to be relegated to t,he t'ask of making a

partisan choice b'etween candidates selected by a white majority'

As noted by the majority, the standard by which we must

examine a redistricting plan under Section 2 is.whether, under

a.

the totality of the circumstances, the plan acts to deny the

group in guestion equal access to the political processes

Ieading to the nominat,ion and elect,ion in that its members have

less opporturity than do other residents of the district to

participate' !n the political Process and to elect the

representatlve of their choice.

l Thus, once we cut through. all of the underbrush of this

"political thicket" in which we are entangled, the real issue in

controversy becomes'apparent: Whether the political interests

of a minority grouP are best maximized by a majority in a single

district or a substant,ial proportion of the minority voters in a

number of districts. Despite the position of the majority that

this question remains virtually unsettled, this writer cannot

help but notice that courts haye consistently condemned

redisBricting plans that sought to fragnnent cohesive or

centralized minority populations under the guise of giving the

minorities "influential," or 'swing" power in several districts.

Major v. Treen, Civ. No. 82-119I, SIip Op. (E.D.La. September

23, 1983) . See also Whj.te v. Regester ' 4L2 U.S. 755 (1973) ;

Nevett v. Sides, 571 F.2d 209 (5ttr Cir. 1978) ; Kirksey v. Board

of Supervisors, 554 E.2d 139, I49 (5ttr Cir. L977li Robinson v.+

Commissioner's Court, 505 F.2d 674 (sth Cir. 1974); Carstens V.

Lamn, 543 F.Supp. 58 (D.CoIo. 1982). these courts have

consistently recognized that fragrmentation invariable result,s in

a minimization of minority votlng Power and PoIitical access.

Yet, as will be seen, the fragmentation of the Dallas County

1:i

minority comrnunit,y wrought by S . B. 4 8 0 is sought to be

justified by an argument that it, gives them increased political

strength.

The' majority opinion's express reason for allowing the

fragmentation of the DaIIas County minority population is the

assertion that minority voting strength will be increased, by

giving majorities "swing vote" influence in two congressional

tdistricts, as opposed to influence in only one minority

controlled district. This Court's majorit,y theorizes that S.B.

480's plan tor distii"t" 5 and 24 gives DaIIas County minorities

the ability to elecE two eandidates of their choice instead of

only one candidat'e elected from a "safe" minority district.

However, the two candidates elected by S. B. 480rs configuration

of districts 5 and 24, would be the choice of the minority com-

munity only in an indirect manner. "Choicer" as contemplated by

the majority opinlon, exists only in the sense that the elected

candidate will have supposedly promised "responsiveness" to

minority concerns and viewpoints in exchange for their

supposedly decisive swing vote influence in his or her election.

Even if this swing vote scenario manifests itself as

contemplated in both the district 5 race and the district 24

race, I cannot, agree with the majority that these

representatives would necessarily be the choice of Dallas County

minorities. This is so because their premise does not

differentiate between the ability to nominate, campaign for, and

ultimat,ely elect a chosen Person, ds opposed to..the ability to

only decide between candidates previously selected by the white

majorities of the competing political parties. The latter set

of circumstances are the fact,s faced by Ehe Dallas County

rninority population today, ES amply demonstrated by the record

in this case.

For the t,heory embodied in S. B. 4 80 to f unction, the

minorities in Dallas County must have the leverage of a crucial

twing vote in two congressional races in order to insure that

their views will be- considered by the candidate seeking their

decisive influence on the election. This swing vote is

vlrtually the only asset the minorities have. However, there is

no assurance t,hat this asset will always be of value in a given

election. In order for Dallas Cotrnty minorities to exercise any

influence in congressional elections via a swing vote, those

congressional races must, by definition, be almost even. If

those races are lopsided contests, however, the minority swing

vote advantage may disappear.

To illustrate, the evidence presented was that in partisan

general elections, minority voters in Dallas County vote 90-958

for the Democrat candidate, no mat,ter what. Because minorities

in Dallas County have not shown a tendency to switch their vot,es

to a Republican candidate when the Democrat candidate proves to

be unacceptable, their vote has become almost captively

Democrat. Therefore, if the Democrat candidate is trailing

badly behind his or her Republican opponent among white voters

in the district, the captive minority vote will rarely be enough

,)

I

to make up the difference. On the other hand , Lf t,he Democrat

defeats the Republican candidate among white voters in the

district, then it, follows that the minority vote did not decide

the elect,ion, it only increased the Democratrs margin of

victory. In either situation, t,he minority community's chief

resource, their swing vote, never materialized. About the only

situation where the minority vote could be a decisive factor is

where the Democrat is close enough'behind the Republican in the

white vote to allow the Democrat minority vote to make a

difference. Even in this last circumstance, the minority vote

may not always translate into political influence because their

support is almost automatic for the Democrat candidate. .

Admittedly, the 1978 general elections of Congressman

Hartin Prost and Jim Mattoxr is weLl as Mattoxrs 1980 general

election victory, seem to illustrate situations where the

Democrat minority vote has made a difference. However, if in

future elections the white majority in districts 5 or 24 decide

to overwhelmingly support the Republican candidater oE for that

matter, the Democrat candidate, the minority community's swing

vote influence vanishes as also we}l may the elected candidaters

responsiveness to the mi.nority's interests. More importantly,

even if the general elections in districts 5 and 24 are decided

by the minority vote, the winning Democrat candidate may only

have been viewed by the minority community as the best of the

worst not their true choice for a rePresentative. In aII

probability, the reaL choice of Ehe minority community may

!

arready have been defeated in the Democrat, primary by the

candidate of choice of the white majority. This is doubry

frustrating because the only real voice minority voters have in

Dallas county is in the Democrat primary elections.

rn the Democrat primary elections, as opposed to the

general elections, minority voters do shift their vot,e between

competing Democrat candidates. once again, however, this type

aof swing vote influence only works if the white majority vot,e is

fairly evenly divided between candidates. ff the white Democra!

majority in aistriJts 5 or 24 are soridry in favor of one

Democrat candidate over the others, that candidate wil} win the

primary erection. This is true even if that candidate is

hostile to or simply ignores t,he interests of the minority

community; they will simply not have enough votes to override

the white Democrat majority in the district. when this sane

candidate who won without minority support in t,he primaries

faces a Repubrican candidate in the general elections, that

candidate need not be overly sensitive to minority interests

because he or she knows the minority citizens of Dallas Corurty

wirl most probabry vote'Democrat and not Repubrican. under

these circumstances, although minority voters cast their ballot

in favor of the Democrat candidate, that candidate could not

under any st,retch of the imagination be considered the candidat,e

of choice for the minority community. Many minority voters may

not be interested in making a choice bet,ween two candidates,

neither of which is sympathetic to their goals and interests,

and not vote at aII. Many worthy and Promising minority

ciLizens of Dallas County may believe there is no hope of

success in a dist,rict controlled by white majorities at both the

primary and general election stages and choose not to seek

political office or choose to not even become involved in the

political process in Dallas County. This degree of political

nonparticipation, while not exPected in DaIlas County, is

O

certainly posslble when a comPact, contiguous and highly

concentrated minority community is divided into two seParate

voting units.

Because of the history of official discrimination in voting

right,s in Dallas Countyr the multimember districts that had been

used in Dallas County until struck down in White v. Regester,

4L2 U.S. 753 (1973), the effects of past discrimination in such

areas as education, employment and health, t'he fact that Dallas

County has never elected a black congressman, and most'

r 'li, '

importihflVl because of the existence of racially polarized

voting in DaIIas County, which I find to have been sufficiently

proven by the evidence contained in the record, I believe that

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act would be violated by

fragmenting the Dallas County mlnorities in two congressional

districts. On the other hand, a 55t minority populat'ion in

district 24, as advocated by the Plaintiffs in this case, would

assure Dallas County minorities that they would have a real

opportunity to equally participate in the selection and election

of candidates of their choice.

(--:,

II.

IE nray welL be t.rue, ES the majority states, that "while

the Iegislaturers intent in drafting S.B. 480 is by no means

controlling on the Section 2 issue, iE does constitute relevant

evidence" to consider. Majority Opinion, ry.. However, the

document on which they rely as indicative of the legislaturers

intent evidences the very denial of access of which the

t'-Plaintif f s complain. see APPendix A. thi.s document, in

eliciting support for t,he Passage of s. B. 4 80 , actively

promotes the mainCenance of district lines so as to Protect

incUmbenE white Democrat Congressmen. Such a consideration is,

in pnd of itself, not prohibited by our courts.T However, when

this partisan-based consideration has an impact on the political

opportunlties and participation of the minorities in those

districts, it then becomes a relevant factor in analyzing the

results of a particular plan under section 2. Furthermore,

where this partisan consideration is incorporated into a

redistrlcting plan (such as in s.B. 480) to close the door on

political access to a particular grouP of voters, iE should be

Iooked upon with disfavor. see Karcher, 103 S.Ct. at, 367L-72.

It is apparent from the legislative history of Section 2 chat,

this was one of the very types of practices that congress was

seeking to overturn with its amendments and the addition of

Section 2(b), i.e., t,he use of what, aPPears to be a racially

neutral purpose, which when examined in the context of the

,,totality of the circumstances" surrounding the plan and its

(

formation, acts to deny certain minority grouPs the access

Congress intended to provide through Section 2-

As one can glean from the numerous pages of the legislative

history of the amendments to Section 2, Congress skillfully

recognized the difficulty of proving that a legislat,ure intended

to promote a racially unfair result. Rarely do we find an oPen

land overt raeially discriminatory PurPose or practice set in

place within a state's political Processes. But, as our courts

have become well afiare, the political machines have become

skillful tacticians in maintaining the subtle remnants of

institutional discrimination in an effort to achieve the results

they deslre. While this writer cannot openly accuse our state

legislature of such wrongful motives, iE is obvious that

Congress intended that the courts not focus on the individual

trees of PurPose and intent; but that the court should step

back, perhaps outside the political thicket, and determine

whether the forestr ES a whole, grows truly within the bounds of

Section 2.

Based upon the foregoing, it is my firm belief that, the

evidence presented by the NAACP and the Republican Party of

Texas has Proven t,hat S. B. 480's split of the DaIIas County

minority community into two congressional districts affords

minority citizens of Dallas County less of an opportunity and

incentive to participate in the polit,ical process and to elect

representatives of their choice. Therefore, S.B. 480, aS it

relates to proposed districts 5 and 24, violates section Z of

the Voting Right,s Act, and should not be allowed to stand.

III.

Even assuming that, Senate BilI 480 measures up to the

requirements of Section 2 as to minority access and

participation, I feel it, imperative that the following

observations should be made with regard to the allegations of

I

constitutional violations. In the analysis of the

constitutional validity of this plan, the majority, in wading

through the bogs of this state's attempts at redistricting, has

consistently ignored the outcry of not, only a substantial number

of minority vot,ers but also the minorj.ty political organizat,ion

of this state.

,I

It has long been noted by the Supreme Court that the

guarantees of the Equal Protection Clause against invidious

discrimination extend to voting rights aqd political groups as

well as economic units, racial communities, and other entities.

Karcher v. Daggett, 103 S.Ct. at 2669; Williams v. Rhodes, 393

U.S. 23, 39, (1958) (Douglas, J., concurring). See also Gaffney

v. Cum.rnings, 4L2 U.S. 735, (1973); Abate v. Mundt, 403 U.S. LgZ,

(197I). In fact, the Court has consistently recognized ,,that

rdilutionr of the voting strength of cognizabre politicar as

well as racial groups may be unconstitutional". Karcher, supra

(and the cases cited therein) . As Justice Stevens not,ed in his

concurrence in Karcher:

l.

t*.,.-:ird

t,

(

t

?here is only one Equal Protection Clause.

Since the Clause does not make some grouPs of

citisens more egual than others, see Zobel v.

Hilliams, 45 U.s. 55, 102 s.ct. 2309 , zffi.ea.

ZffiTf (1982) (Brennan, J., concurring) , its

protection against vote dilution cannot be confined

to racial groups. As long as it proscribes

gerr)rmandering against such grouPs, its proscription

must provide comparable protect,ion f or other

cbgnizable groups of voters as welI.

Karcher, I03 S.Ct. at 2669.

Throughout, the examination of the legislative history and

background of Senate Bill 480, I am ever reminded that a finding

of a constitutional'violation requires evidence of intent or

purpose on the part of the legislature to discriminate against a

defined group of voters. In regard to the particular districts

in question, iC appears that the 1983 Legi.slature that enacted

S.B. {80 was strongly concerned with the need to draw the

district lines so as to protect the incumbent white Democrat

Congressmen rather than with whether the plan provided a

neutral, constitut,ionally sound redistricting scheme. See

Appendix !. It may be true that this plea for the support of S.

B. 480 does not necessarily provide direct evidence of intent on

the part of the Democrat:controlled legisLature. However, even

the majority conceded that this evidence "convincingly

demonstrated that political considerat,ions provided t,he critical

stimuli for S.B. 4g0ts adoption." SuPra. Thus, it would aPPear

t,hat such evidence of partisanship may well provide an inference

that a major purpose behind the configuration of the Dallas

Cor:nty districts was to discriminate against !h" minority

political party by creating districts that would protect.

L2

.!*1jj - - : ,r , - :-i;::;,. -. -,+,,, j. .4:--

-

{)t-. '

Democrat congressmen. It would be impractical to promote the

idea that ,a State's redistricting plan could be invalidat,ed

simply because partisan political considerations provided the

basis for some of the line-drawing decisions. See Karcher,

supr? 1t 257L. As noted in Karcher, it would be "unrealistic to

attempt to Proscribe all political considerat,ions in the

essentially political Process of redistricting." Id. ag

t267L-72. However, where the Plan. has 'a significant adverse

impact upon a definite political group, " the Presence of a

discrimlnatory intent on the part of the legislature may well

place the plan outside the boundaries of constitutional

compliance.

The dilution or minirnization of the voting st,rength of

identifiable groups of votels., including political groups, has

been noted by one famous conunentator as occurring in one of two

,r.y".8 A redistricting plan may 'pack" the members of the group

into one or a few "safen districts, giving them control there,

but limiting their impact outside those districts. On the other

hand, a plan may spread out or "fragmentn the group, thus giving

them some impact in several districts, yet preventing them from

securing a substantial majority in any district.9

It is my opinion that the redistricting plan for the DaIIas

area districts under Senate Bill {80 has a significant adverse

impact on the voting strength of the Republican Party in DaIIas

County. , The f ragrmentation and placing of portions o f the

minority communities within the various distriats in DaIIas

I3

County acts to minimize the strength of the Republicans in

CisEricts where they could Potentially hold a majority. Such a

dilution of this party's political Power denies to the

guarantees recognized and afforded under the Equal Protection

CIause.

CONCLUSION

As we come to what many had hoped would be the end of the

tr.*o" Legislaturers quest for a redistricting scheme, t,his Court

has endeavored to hold true to the premise that "reapportionment

is primarily a matter for legislative consideration and

determination." Revnolds v. Simsr.377 U.S. 533, 585 (I954). l{e

have sought to intrude upon sCate policies and preferences only

when necessary to guide the various plans into statutory and

constitutional compliance. It is the opinion of the majority

here today that Senate Bill 480 provides a statutorily and

constitut,ionally sound Plan that has neither a racially

discriminatsOry PurPose nor such an effect. However, as one

rnight gather f rom my comment,s above, it is my opinion that the

p1an, ES currently drawn, not only denies minorities in the

Dal1as County districts equal access and oPPortrrnity in

violation of Section 2, but also reflects a PurPose on the part

of the Legislature to run afoul of the Equal Protection Clause.

Accordingly, I cannot join my learned colleagues in their

endorsement, of S.B. 480.

(-

I4

a\)

FOOTNOTES

r..

42 U.S.C. Sr973

2.

As the maJority has noted, there are apparently only tr.ro

districts still at issue. These are Districts 5 and 24

in Dallas County.

?

l-'' see Karcher v. Pggg.S,

-u.s. -,

ro3 s.ct. 2633,

;-stevens , J. , concurring) .

4.

'.r '. 42 U.S..C. 51973.

See White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755, 765-56 (1973) I

Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. L24, 156-57 (1971).

5.

5.

7.

The proviso contained in {2 U.S.C. 1973 states:

'. ... Provided, that nothing in this section

establishes a right to have members of a protected

class elected in numbers equal to their Pro-

portion in the population.'

Karcher, supra at 2671-72i Gaffney v. Cummings, ALZ U.S.

735, 753-5{ (1973)..

8. L. Tribe, American Consticutional Law 756 (1978).

9. Id. at 756r r!. 2. See also Karcher, 98. at 2672, n. 13.