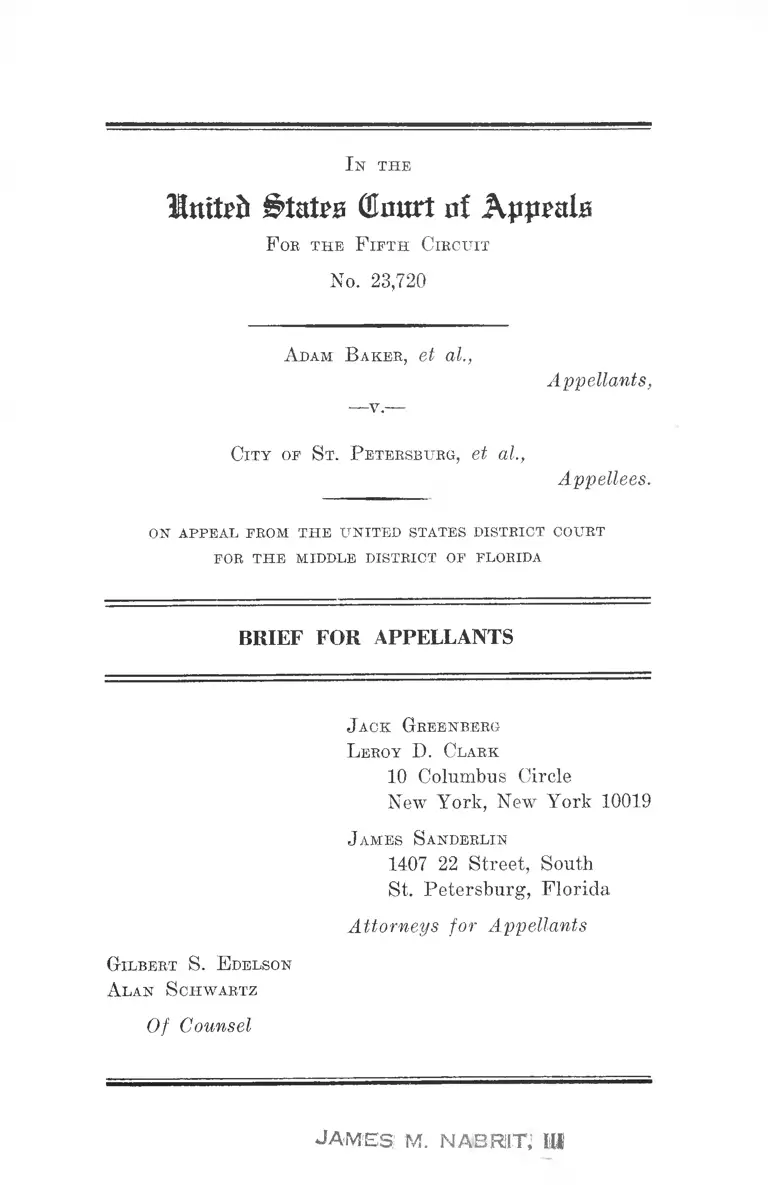

Baker v. City of St. Petersburg Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Baker v. City of St. Petersburg Brief for Appellants, 1966. 287a1e9e-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/214bda85-ee2d-4968-b4a9-5f0f441a3058/baker-v-city-of-st-petersburg-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

United States Cilnurt n! Appeals

F ob t h e F if t h C ibcu it

No. 23,720

A dam B aker , et al.,

Appellants,

—■v.—

City of S t . P etersburg , et al.,

Appellees.

on a p pe a l fro m t h e u n it e d sta tes d ist r ic t court

FOB THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF FLORIDA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

J ack Greenberg

L eroy D. Clark

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

J ames S anderlin

1407 22 Street, South

St. Petersburg, Florida

Attorneys for Appellants

G ilbert S . E delson

A lan S chw artz

Of Counsel

JA M E S M. N A BEIT , M

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement of the Case .................................................... 1

A. The Pleadings ...................................................... 1

B. The Facts Adduced at the T ria l..................... 3*

X. Present Organization of the Police Depart

ment .............................................................. ^

2. The Zone System and Zone 13 ...... .......... 4

3. Negroes in the Police Department....... ...... 5

4. The City’s Defense ........................................ 10

C. The Decision of the District Court................. 12

Specification of Errors ................................................... 13

I, The District Court Erred in Holding That No

Discrimination Was Practiced by the Defen

dants. The Uncontroverted Facts Show That the

Acts of the Police Department Were Discrim

inatory as a Matter of Law ....................... ........ 13

II, Assuming Arguendo That Discriminatory Prac

tices May Be Justified by Police Efficiency, the

District Court Erred in Requiring Plaintiffs to

Show That Defendants’ Actions Were Arbitrary

and Capricious. Under a Correct Standard of

Proof, Defendants Failed to Establish Justifica

tion for Their Practices ................................... 24

A. Assuming Arguendo That Discriminatory

Practices May Be Justified by Police Effi

ciency, the District Court Erred in Requiring

Plaintiffs to Show That Defendants’ Actions

Were Arbitrary and Capricious ................. 24

11

PAGE

B. Defendants Failed to Meet the Burden of

Justifying Their Racially Discriminatory

Practice ........................... 29

C onclusion ......................................................................................... 33

T able of C ases

Armstrong v. Board of Education of the City of Bir

mingham, 333 F.2d 47 (5th Cir. 1964) ..................... 18

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954) ........................ 27

Boson v. Rippy, 285 F.2d 43 (5th Cir. 1960) ............... 18

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond, 382

U.S. 103 (1965) ........................................................ 18,19

Brooks v. School District of City of Moherly, 267 F.2d

733 (8th Cir. 1959) ..................................................... 24

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)

16,19, 20

Chambers v. Hendersonville City Board of Education,

245 F. Supp. 759 (W.D. N.C. 1965) .... ...................

Clemons v. Board of Education of Hillsboro, 228 F.2d

853 (6th Cir. 1956) ....................................................

Davis v. County School Board, 103 F. Supp. 337 (E.D.

Va. 1952) ................................................................... 20

Franklin v. County Board of Giles County, 360 F.2d

325 (4th Cir. 1966) ........ ............................................ 19

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960) .............. 20

Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U.S. 683 (1963) .....17,18

Green v. School Board of the City of Roanoke, 304

F.2d 118 (4th Cir. 1962) ....................

24

22

Ill

PAGE

Hamm v. Virginia State Board of Elections, 230

F. Supp. 156 (E.D. Va. 1964) ................................. 16

Holland v. Board of Public Instruction of Palm Beach

County, Florida, 258 F.2d 730 (5th Cir. 1958) .......... 20

Jackson v. School Board of the City of Lynchberg,

321 F.2d 230 (4th Cir. 1963) ................................... 18

Jones v. School Board of the City of Alexandria,

278 F.2d 72 (4th Cir. 1960) ........................ .......... 18

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184 (1964) .... ............ 27

Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966) .................... 22

Oyama v. California, 332 U.S. 633 (1948) ........ -........ 26

Singleton v. Board of Commissioners of State Insti

tutions, 356 F.2d 771 (5th Cir. 1966) .................... 16

Stell v. Savannah County Board of Education, 333

F.2d 55 (5th Cir. 1964) .......................................... 18

Taylor v. Board of Education of the City School Dis

trict, 191 F. Supp. 181 (S.D.N.Y. 1961), aff’d, 294

F.2d 36 (2d Cir. 1961) .......................................... 19,21

Watson v. Memphis, 373 U.S. 526 (1963) . . . . ........... 21

S t a t u t e s

28 United States Code §1343(3), (4) ........................ 2

42 United States Code §1981 ...................................... 2

42 United States Code §1983 ..... ....................— ....... 2

42 United States Code §2000 et seq............................. 2

I n t h e

Im te ft §>tal?0 (Emtrt of Apppalu

F ob t h e F if t h C ir c u it

No. 23,720

A dam B a ker , et al.,

—v.-

Appellants,

City of S t . P etersburg , et al.,

Appellees.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

This is an appeal from a judgment of the United States

District Court for the Middle District of Florida, entered

on March 31, 1966, dismissing plaintiffs’ prayer for in

junctive relief and dismissing plaintiffs’ action on the

merits. The notice of appeal was filed on April 26, 1966.

Statem ent o f the Case

This action, brought by 12 of the 14 Negro policemen

in the St. Petersburg, Florida Police Department, seeks to

desegregate that department and to provide equal op

portunity to Negro policemen. The record in this case

conclusively shows that the department, and particularly

its Uniform Division, is, and for many years has been,

operated on a segregated basis.

A. The Pleadings

Plaintiffs brought this class action under Rule 23(a)(3)

of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure on behalf of

2

themselves and others similarly situated. Jurisdiction was

invoked pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §§1343(3) and (4). This

suit in equity is authorized by and instituted pursuant to

42 U.S.C. §1983 and Titles II and III of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 (42 U.S.C. §2000 et seq.). Plaintiffs seek to

secure protection of their civil rights and to redress a

deprivation of their rights, privileges and immunities

secured by the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitu

tion of the United States, Section 1, 42 U.S.C. §1981 and

the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The plaintiffs, as noted above, are police officers in the

Police Department of St. Petersburg. The defendants are

the City of St. Petersburg, Lynn Andrews (hereafter

“Andrews”), its City Manager and Harold Smith (here

after “Smith”), Chief of Police of the City (R. 8).

The complaint alleges in material part that Negro police

officers in St. Petersburg are assigned work as patrol

officers in a zone so drawn as to cover the Negro in

habitants; that they are so assigned solely on the basis

of race and are systematically excluded from patrol and

investigative duties in all other patrol zones solely on

the basis of race; and that the Police Department main

tains a dressing room in a segregated and discriminatory

manner in that all Negro officers are assigned to lockers

in one corner of the dressing or locker room (R. 9-10).

The answer admits that St. Petersburg is a Florida

municipal corporation; that Andrews is City Manager,

and as such governs and controls several departments

and agencies of the City; and that Smith is Chief of Police

and has the authority to administer and regulate the

affairs of the Police Department (R. 8). The answer denies

that Negro police officers are assigned to work in a zone

so drawn as to cover all Negro inhabitants of St. Peters-

3

burg but admits that Negro police officers are assigned

primarily to patrol one zone that is composed of both

Negro and white inhabitants and that their assignments

are the result of the administrative decision of the Chief

of Police that they can render the most effective service

within that zone (R. 15). The defendants admit that

Negro police officers have been assigned lockers together

in a certain area of the locker room but allege that such

assignments were made at the request of the Negro officers

in the Department when lockers were first provided (R. 17).

B. The Facts Adduced at the Trial

1. Present Organization o f the Police Departm ent

The Chief of Police of the St. Petersburg Police De

partment is appointed by the City Manager and is re

sponsible to him (R. 213). Under the Chief of Police are

three divisions, the Uniform Division, the Detective Divi

sion and the Service Division, each headed by a Captain

(R. 37, Def. Ex. 7). The Chief and the three division

commanders sit as a policy making body for the Police

Department (R. 38).

The Uniform Division comprises a Traffic Bureau and

a Patrol Section (R. 37, Def. Ex. 7). For purposes of

non-traffic patrol, both on foot and by car, the City is

currently divided into 16 zones, numbered from 1 to 16

(PI. Ex. 1). There are three shifts in the Patrol Section,

with four sergeants on each shift (R. 76). One sergeant

is at headquarters in charge of the desk, one is a relief

sergeant and two sergeants, known as the S-l and S-2

sergeants, are outside patrol sergeants (R. 76, 78). The

S-l sergeant is in charge of the zones on the North Side

of the City; the S-2 sergeant is in charge of the zones

on the South Side of the City.

4

2. The Zone System and Zone 13

In or about 1959, the Police Department adopted a zone

system for purposes of patrol under which the City was

divided into 6 zones (R. 66). In or about 1962, the 6-zone

system was changed to a 13-zone system and, in or about

1964, the present 16-zone system was adopted (R. 54, 55).

Zone 13 is unlike all other zones on the Police Depart

ment map. It is superimposed on and overlaps four other

zones (R. 55). As described by Chief Smith:

“Zone 12 and Zone 13 cover approximately the same

general area. Now, Zone 11 on one side overlaps 13

a little bit. And I think another one on the other side

overlaps it slightly. Zone 1 overlaps from the other

side, it overlaps it partially. So you might say in all

the predominantly negro districts there are two zones,

two cars that can patrol them and still remain in their

own beat.”

As indicated by Chief Smith, Zone 13 comprises the heavily,

densely populated Negro section of the City (R. 59). In|

describing how Zone 13 was established, Chief Smith, on

examination by counsel for defendants, testified:

“Q. Was there any effort to establish the zone sys

tem so you could single out Zone 13 as the negro dis

trict! A. No.” (R. 101)

Later, however, on examination by counsel for plaintiffs,

Chief Smith testified:

“Q. Chief Smith, wouldn’t you say that race is the

basis for this drawing of zone lines, Zone 13? A. If

you say race, I would say yes, probably it would be.

Because I feel that the Negro officers can do work

more efficiently in there. They can get information

5

easier than the white officer can. They are mistreated

less.

“Q. Could you answer my question, please? A. Yes.

I would have to say that.” (R. 107)

Again, in Chief Smith’s testimony:

“Q. Now, when these zones were designed, I notice

that Zone 13 is irregularly shaped—they were designed

at that time to encompass all of the Negro neighbor

hood; is that correct? A. The majority of the Negro

neighborhood, yes.” (R. 191)

The overlapping area comprising zones 12 and 13 is, in

Chief Smith’s language, “ . . . a heavy work load area.

We have more calls in that area—twice as many calls in

that area as from any other equal area in the City” (R.

96-97). The police in Zone 13 deal mostly, in the words of

a policeman assigned to the area, “with vicious type

crimes”, such as “shootings, cuttings, potash throwing” (R.

141). The aforementioned officer, Freddie L. Crawford,

one of the plaintiffs, testified that on one occasion he had

had three shirts torn off his back in one night and that on

other occasions he had been stabbed in the course of per

forming his duties (R. 139).. He testified that on one occa

sion in the course of making an arrest for disorderly con

duct, a riot started in the course of which he was assaulted

with bottles and rescued from the crowd by the timely

arrival of another police car. His own cruiser was de

stroyed by the mob (R. 144).

3. Negroes in the Police Departm ent

a. Past History

There were no Negro officers in the Police Department

until in or about 1950 (R. 39-40). At that time, four

Negroes were hired and assigned to patrol the Negro dis-

6

trict of the City—what is now Zone 13 (R. 41). The un

written policy at that time was that the Negro officers

could not arrest a white person (R. 44). That policy, ac

cording to Chief Smith, has since “gradually rotated away”

(R. 40). Neither that policy, nor its erosion were expressed

in writing; they were one of a number of unwritten policies,

customs and habits followed by the Department (R. 40, 44).

Another “custom or habit” followed by the Department

was the “colored car” (R. 65). In or about 1959, when the

Police Department adopted a zone system, the Negro officers

were not assigned to any zone. A “colored car”, manned

by Negro officers, was given calls in the Negro areas or

from Negroes (R. 66). The policeman receiving a call from

a complaining person could and still does ascertain whether

the caller was a Negro either by the tone of his voice or

by the area from which the call came (R. 63). In sum,

until in or about 1962, all Negroes were assigned solely to

the Negro area. That policy, based upon the custom and

habit of the Police Department has continued, with a num

ber of refinements and minor exceptions, to the present.

In or about 1962, the 6-zone arrangement previously

described was changed to a 13-zone arrangement. At that

time, the Negro patrol officers, who, unlike the white officers,

had had no official zone assignment, were for the first time

“officially” assigned to a zone—Zone 13, which was then

created to encompass the territory previously patrolled

solely by Negro policemen.

b. Present Assignments

The Police Department has continued its custom and

habit of assigning Negro patrol officers* solely to Zone 13,

the Negro area of the City. As Chief Smith testified:

0 There were at the time of trial 14 Negro policemen in the St. Peters

burg Police Department which numbered 252 men. Of, those 14, 10 were

assigned to the Uniform Division and all 10 were also assigned to Zone 13

7

“Q. Is there any reason, in your opinion, why Zone

13 would have to be designed this way and why the

irregular portions could not have been left in other

zones! A. The only reason would be that it has al

ways been partially—this was brought down by cus

tom. They have always been assigned in that area.

“Q. What custom are you speaking of? A. The

customs from the past years.

“Q. What custom, in particular? A. The custom of

assigning the Negro officers to work in the Negro

areas. This was part of the custom wre carried on,

as allowing Methodist Town [a Negro section] to be

part of Zone 13. . . . ” (R. 193-194)

All Negro officers, upon graduation from the Police

Academy are assigned directly to Zone 13 (R. 111). No

Negro officer has ever been assigned to a patrol zone other

than Zone 13; no white officer is assigned to Zone 13, ex

cept insofar as the zone to which he is assigned may over

lap Zone 13 (R. I ll, 114, 115). These assignments are

based solely on race. Again, Chief Smith testified:

“Q. Now, is it your position that at the beginning

of their tour of duty, they are assigned to the negro

area, not having worked any other area, and this is

because they are negroes? A. Because they can get

along better in that particular area than the white

officers, can, yes.

“Q. And this is based on the fact that they are

negroes? A. Yes, it is.” (R. 116)

A separate chain of command exists for the Negro of

ficers. They are under the command of Sergeant Samuel

(R. 56). Two Negro officers, one of whom requires light duty and whose

assignment is temporary, are assigned to the Service Division (R. 56,

R. 114). Two Negro officers are assigned to the Detective Division where

they handle, mainly complaints from Negroes (R. 196).

8

Jones who is not a plaintiff in this action. Sergeant Jones

is the sole Negro sergeant in the Police Department and

has the designation—not given to any of the other 16

sergeants in the Uniform Division—of S-3. As noted above,

the S-l and S-2 sergeants are those sergeants who, on a

particular shift, are assigned supervision over the North

Side and South Side zones respectively. Sergeant Jones’

primary duty is to supervise the Negro members of the

Uniform Division. This is not indicated in Chief Smith’s

testimony. On the matter of Sergeant Jones’ duties, he

testified as follows:

“A. Sergeant Jones is the liaison man between myself

and the majority of the negro community. He works

—more or less sets his own hours. He works part of

the time in the day and part of the time in the evening,

and has the-—well, as I say, he is the liaison man be

tween myself and the leaders in most of the negro

community. He keeps me informed as to .what is

going on and what to expect to happen in the future,

and things like that. Besides, he does have supervision

over the officers in the field when he is working and

out there.

“Q. In other words, he is not always assigned to the

field! A. Well, he is in the field just about all the

time.”

# * * # *

“Q. Is he regularly assigned white officers I A. Ac

tually, he is not regularly assigned officers. He is in

charge of any that are working in the area where he

is at, if he happens to be the supervisor that is called

to that particular spot.”

• . • • * #

“Q. Then would he be assigned to Zone 13! A. He

doesn’t have a zone assignment. He is free to go

9

wherever he pleases, or wherever they happen to have

a need for him. He doesn’t—he isn’t restricted to any

zone, no.” (R. 73, 80, 81)

Sergeant Jones’ understanding of his duties differed

from that of Chief Smith, as his testimony shows:

“Q. . . . Would your command—well what is your

command, who is under you? A. Oh. I have the

Negro officers under my command.” (R. 240)

# # # # *

“Q. Your primary responsibility, as you know it,

is to supervise the Negro officers under your command?

A. That’s right.

“Q. Has it ever been mentioned to you that you are

also a liaison officer of the Department? A. Well, I

don’t quite understand what you mean along that line

there.

“Q. Do you know what a liaison officer is? A. A go-

between, I would say.

“Q. Would you describe your duties as this? A.

Nothing no other sergeant wouldn’t have to do. Just

anything that comes up in the community, he is to

report to his supervisor. That is about the only thing

that I know of.

“Q. I didn’t quite get your answer. Would you re

peat it? A. To report, you know, the happenings in

the community that should be brought to the Chief’s

attention and reported to your supervisor.

“Q. Is this what every sergeant—is this the normal

sergeant’s assignment? A. All persons that are work

ing in the Police Department is supposed to report

things that need to be brought to the Chief’s attention.

All personnel.

“Q. So are your duties in this respect any different

from any other sergeant’s? A. No.

10

“Q. Are any white officers assigned to yon! A. No.”

(R. 243-244)

In furtherance of the continuing discrimination and seg

regation by the Police Department, the Negro officers’

lockers are placed separately on one side of the back

corner of the locker room (R. 90). Chief Smith testified

that the assignment of lockers, like the assignment of

patrol zones, is also the result of custom and habit.

In 1959, when locker assignments were made, the four

Negro officers then in the Police Department were consulted,

through Sergeant Jones, about the location of their lock

ers. They then indicated that they would like to be together

(R. 89). As additional Negro officers joined the force, they

were assigned in the same area (R. 89). In the course of

a subsequent meeting with Negro officers, dissatisfaction

with the locker arrangement was indicated to Chief Smith.

But because there was no specific and individual request

for a change, no change was made (R. 87). Chied Smith

testified that while he would “consider” requests for change

in locker assignments from individual officers “when space

was available”, he would not receive grievances on a group

basis (R. 106-107).

4. The City’s D efense

There has been established in the St. Petersburg Police

Department, particularly the Uniform Division, a separate

Negro enclave, where Negro policemen are assigned on the

basis of their race to a patrol zone carved out on a racial

basis, under a Negro chain of command, and where locker

assignments are made on a racial basis.

The City denied, however, that the Police Department

has engaged in discriminatory practices, and claimed that

assignments to Zone 13 were dictated not by race, but by

11

efficiency. No expert testimony was produced to show that

Chief Smith’s method of zoning and assignment was on the

facts here presented, sound police practice. No studies

were made to show that each Negro assigned to Zone 13

was more efficient or effective in that zone than any other

officer in the Department. The sole justification for Chief

Smith’s action was Chief Smith’s opinion. As Chief Smith

put i t :

“I say because they are more efficient there. Regardless,

if they were Italian and it was an Italian community,

we would assign Italians to that community, because

they could get along with the people there better.”

(R. 115)

One aspect of Chief Smith’s testimony is particularly

enlightening. One of the zones over which Zone 13 is

superimposed is Zone 12. Both zones encompass basically

the same, predominantly Negro area. Yet no white officers

are assigned to Zone 13 and no Negro officers are assigned

to Zone 12. Chief Smith was questioned about this matter:

“Q. . . . I asked you why Negroes haven’t been

assigned to Zone 12, especially since it overlaps 13.

A. Our policy, as I stated before, is to assign Negro

officers to 13.

“Q. But 12 and 13 take in basically the same terri

tory. One runs from 9th to 34th, the other one runs

from—. A. Basically, the same area, yes. They are

predominantly colored areas, yes.

“Q. Then what is the rationale, what is the reason

that they aren’t assigned to 12. A. I said there was

no basic reason.

“Q. This is the result of custom, too! A. Not neces

sarily. It is just not done. I can’t tell you why be

cause I don’t know why.

12

“Q. You never thought of it? A. I never have—

I have never even considered it.” (R. 206)

C. The Decision of the District Court

The opinion of the District Court is set out at pp. 279-

285 of the Record. The Court found that the City had been

divided into 16 zones for the purpose of effective police

patrol throughout the City and that Zone 13 had not been

zoned for the purpose of discrimination. The Court found

that Negro officers were assigned to Zone 13 because “in

the opinion of the Chief of Police, they are better able to

cope with the inhabitants of that zone” (R. 281). The

Court also found that the assignment of Negro officers to

Zone 13 “was not done for purposes of discrimination but

for the purpose of effective administration” (R. 281).

Finally, the Court found that there was no discrimination

in the assignment of lockers (R. 283). The Court concluded

that the actions of the City, through the City Manager and

the Chief of Police in the assignments of Negro policemen

to a predominantly Negro community and in the assign

ment of lockers, were not made in an unreasonable, arbi

trary or capricious manner and declared:

“That the Court will not substitute its judgment for

that of the defendants in the performance of those

matters within their jurisdiction unless there exists

sufficient factual basis that the defendants’ actions were

unreasonable, arbitrary, capricious or unlawful with

respect to the patrolmen. Brooks v. School District

of Moberly, Mo., 267 F.2d 733 (1959); Chambers v.

Hendersonville City Board of Education, 245 F. Supp.

759 (1965).” (R. 283-284)

13

Specification o f Errors

The District Court erred in the following respects.

1. The district court erred in holding that the defen

dants’ conceded racial classification could be justified on

grounds of police efficiency.

2. The district court erred in requiring plaintiffs to

show that defendants’ actions were arbitrary and capri

cious.

3. The district court erred in failing to find, as a matter

of law, that under a correct standard of proof, defendants

did not justify their admitted racial classifications.

I.

T he D istrict Court Erred in H olding That No D is

crim ination Was Practiced by the D efendants. The

U ncontroverted Facts Show That the Acts o f the P olice

D epartm ent W ere D iscrim inatory as a Matter o f Law.

We set out, preliminarily, what this case is about, and

what it is not about; what .plaintiffs claim, and what they

do not claim.

This is not a case where, in response to a court order

or to expressed community sentiment, Negro policemen

were assigned to an area as part of an integration pro

gram. Nor is this a case where assignments were made

on the basis of studies of the individual capacities and

capabilities of each policeman assigned and the suitability

of each individual policeman for that assignment. There

is no showing, for example, that it was decided, after a

study, that not a single white policeman in the St. Peters-

14

burg Police Department could function as efficiently or

effectively in Zone 13 as the Negro officers assigned there.

Nor is this a case where a Negro was assigned to a par

ticular position because no white policeman could possibly

perform the task—as where a Negro detective is assigned

to work underground in an individual situation where

acceptance by a suspect or suspect group requires that he

be Negro.

What is involved here is a continuing and long-standing

pattern and custom of segregation of and discrimination

against Negro policemen. What is involved here is the

delineation of a special zone, carved out on a racial basis

and superimposed on other zones. To this zone Negro

policemen and only Negro policemen are assigned solely

because of their race. Wbiat is involved is a group judg

ment; a judgment that because of their race, and for no

other reason, Negro policemen are suitable only for one

zone and no other—not even Zone 12, another predomi

nantly Negro zone. What is involved is a group judgment

that no white policemen, even those suitable for another

predominantly Negro zone, are as suitable as any Negro

for assignment to the specially carved out zone.

On these facts, the plaintiffs have been deprived of their

constitutional rights. And neither police efficiency or any

other purported efficiency can justify this.

The essential facts are clear and undisputed on the

record. These are the essential facts:

1. St. Petersburg has a long history of maintaining a

policy of separating policemen by race. When Negro police-:

men were first hired in or about 1950 their sole duties

were to patrol the Negro area. A specially designated

“colored car” was used by them. When the zone system was

first adopted in 1959, the Negro policemen were not as-

15

signed to a zone as were the white policemen but con

tinued to patrol the Negro area. When the zone system

was revised in 1962, the former area patrolled by the

Negro policemen was designated as “Zone 13” and was

superimposed over other zones. The boundary lines of

Zone 13 were drawn on the basis of race and in furtherance

of established customs of segregation.

2. Negroes and only Negroes are assigned to patrol

Zone 13. No Negro has ever been assigned to patrol

another zone, not even Zone 12, another predominantly

Negro zone. No white officer is assigned to patrol Zone 13

except insofar as the zone to which he is regularly as

signed may overlap Zone 13. The basis for these assign

ments is solely racial. Although Chief Smith claimed that

the assignments to Zone 13 were made on the basis of

alleged police efficiency, that efficiency turns solely on

racial factors.

3. The only Negro sergeant in the Police Department

is in charge of the Negro policemen patrolling Zone 13.

4. Locker assignments were originally made on a racial

basis although, according to defendants, with the consent

of the four Negro officers then on the force. Subsequent

assignments, however, were also made on a racial basis

and the Chief of Police has refused and still refuses to

reassign lockers in the Negro section of the police locker

room.

Applying the law to these essential and uncontroverted

facts, only one conclusion is possible—that where police

assignments are made by defendants solely on the basis

of race to a zone whose boundaries are drawn by defen

dants on the basis of race, the acts of the defendants are

discriminatory and violate the Fourteenth Amendment.

16

In Singleton v. Board of Commissioners of State Insti

tutions, 356 F.2d 771 (5th Cir. 1966), this Court said (at

p. 772) :

“Twelve years ago, in Brown v. Board of Educa

tion of Topeka, 1954, 347 U.S. 483, 74 S. Ct. 686, 98

L. Ed. 873, the Supreme Court effectively foreclosed

the question of whether a State may maintain racially

segregated schools. The principle extends to all in

stitutions controlled or operated by the State. ‘ [I]t is

no longer open to question that a State may not con

stitutionally require segregation of public facilities’.

Johnson v. Virginia, 1963, 373 U.S. 61, 62, 83 S. Ct.

1053, 1054, 10 L. Ed. 2d 195.”

The principle enunciated by this Court in Singleton

goes beyond statutes requiring segregation. In Hamm v.

Virginia State Board of Elections, 230 F. Supp. 156 (E.D.

Va. 1964), aff’d without opinion, 379 U.S. 19 (1964), Judge

Bryan, of the Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit,

writing for a three-judge court stated (230 F. Supp. at

p. 157):

“The ‘separate but equal’ racial doctrine was con

demned a decade ago in Brown v. Board of Educa

tion, 347 U.S. 483,74 S. Ct: 686, 98 L. Ed. 873 (1954).

Subsequent decisional law has made it axiomatic that

no State can directly dictate or casually promote a

distinction in the treatment of persons solely on the

basis of their color. To be within the condemnation,

the governmental action need not effectuate segrega

tion of facilities directly [citing]. The result of the

statute or policy must not tend to separate individuals

by reason of difference in race or color. No form of

State discrimination, no matter how subtle, is per

missible under the guarantees of the Fourteenth

amendment freedoms.” [Emphasis supplied.]

17

The courts have uniformly held that assignments of

pupils or public officials based solely on their race, or

the drawing of administrative boundaries on a racial

basis by public authorities violates the Fourteenth Amend

ment of the Constitution of the United States. The princi

ple has been clearly enunciated by the courts in a series

of school cases, in which assignments to schools were at

tempted on the basis of race.

In Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U.S. 683 (1963) the

Supreme Court struck down a provision in a school desegre

gation plan which would permit transfers on the basis of

race. The Court said (at pp. 687-688):

“Classifications based on race for purposes of trans

fers between public schools, as here, violate the Equal

Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. As

the Court said in Steele v. Louisville & Nashville R.

Co., 323 U.S. 192, 203 (1944), racial classifications

are ‘obviously irrelevant and invidious.’ The cases

of this Court reflect a variety of instances in which

racial classifications have been held to be invalid,

e.g., public parks and playgrounds, Watson v. City

of Memphis, ante, p. 526 (1963); trespass convictions,

where local segregation ordinances preempt private

choice, Peterson v. City of Greenville, ante, p. 244

(1963); seating in courtrooms, Johnson v. Virginia,

ante, p. 61 (1963); restaurants in public buildings,

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.S.

715 (1961); bus terminals, Boynton v. Virginia, 364

U.S. 454 (1960); public schools, Brown v. Board of

Education, supra; railroad dining-car facilities, Hen

derson v. United States, 339 U.S. 816 (1950); state

enforcement of restrictive covenants based on race,

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948); labor unions

acting as statutory representatives of a craft, Steele

18

v. Louisville & Nashville R. Co., supra; voting, Smith

v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649 (1944); and juries, Strauder

v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1879). The recogni

tion of race as an absolute criterion for granting

transfers which operate only in the direction of schools

in which the transferee’s race is in the majority is

no less unconstitutional than its use for original ad

mission or subsequent assignment to public schools.

See Boson v. Rippy, 285 F.2d 43 (C.A. 5th Cir.).”

Even prior to Goss, this Court and other Circuit Courts

took the position there enunciated. The Court in Goss

cited with approval this Court’s decision in Boson v. Rippy,

285 F.2d 43 (5th Cir. 1960). And, in Stell v. Savannah

County Board of Education, 333 F.2d 55 (5th Cir. 1964),

cert, denied, 379 U.S. 933 (1964), this Court, dealing with

pupil assignments said (at p. 61) :

“In this connection, it goes without saying that

there is no constitutional prohibition against an as

signment of individual students to particular schools

on a basis of intelligence, achievement or other apti

tudes upon a uniformly administered program but

race must not be a factor in making the assignments.”

See also: Armstrong v. Board of Education of the City

of Birmingham, 333 F.2d 47 (5th Cir. 1964); Jackson v.

School Board of the City of Lynchberg, 321 F.2d 230

(4th Cir. 1963); Green v. School Board of the City of

Roanoke, 304 F.2d 118 (4th Cir. 1962); Jones v. School

Board of City of Alexandria, 278 F.2d 72 (4th Cir. 1960).

In Bradley v. School Board of City of Richmond, 382

U.S. 103 (1965), the Supreme Court reversed a decision

of the Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit approving

a school desegregation plan without holding full eviden-

19

tiary hearings on the question of whether faculty alloca

tion on a racial basis rendered the plans inadequate under

the principle of Brown v. Board of Education. And in

Franklin v. County Board of Giles County, 360 F.2d 325

(4th Cir. 1966), the Court of Appeals for the Fourth Cir

cuit, following Bradley, held that the Fourteenth Amend

ment forbids discrimination on account of race with respect

to the employment of teachers.

But the St. Petersburg Police Department has gone be

yond using race as the sole basis for assigning Negro

policemen to patrol a certain area; it has zoned the area

to which those policemen are assigned on a racial basis.

When the City was first zoned for police patrol purposes

in 1959, the Negro policemen were assigned to no zone

but continued to patrol the Negro area previously pa

trolled by them. That system continues today, except that

the area originally set aside for patrol solely by Negro

officers has been given the official designation of Zone 13.

Logic would dictate that where a City is zoned for any

purpose, there be created a series of adjoining zones. In

this case, however, Zone 13 is specially designed to over

lap four other zones, mainly Zone 12. When asked why

the area encompassing Zone 13 was not broken up and

a series of smaller, adjoining zones created, Chief Smith

replied that “ . . . this was a matter of custom. They

[the Negro officers] have always been assigned i" that

area” (R. 193).

Such zoning, on a racial basis for the purpose of as

signment on a racial basis, is unconstitutional under the

Fourteenth Amendment. Thus, in Taylor v. Board of Ed

ucation of City School District, 191 F. Supp. 181 (S.D.N.Y.

1961), aff’d, 294 F.2d 36 (2d Cir. 1961), the court held

that school districting with the purpose and effect of pro

ducing a substantially segregated school system clearly

20

violates the Fourteenth Amendment. See also, Holland v.

Board of Public Instruction of Palm Beach County, Fla.,

258 F.2d 730 (5th Cir. 1958). Cf. Gomillion v. Lightfoot,

364 IT.S. 339 (1960).

In summary, the defendants on uncontroverted facts

have as a matter of law maintained a policy of racial

discrimination violative of the constitutional rights of the

plaintiffs.

Throughout the trial, defendants maintained that their

long-standing policy and custom of assigning Negro patrol

policemen solely to a single patrol area carefully zone to

include the predominantly Negro section of the City was

justified. Their argument, adopted by the District Court,

was that they were charged with the duty of operating the

Police Department in the most effective and efficient man

ner and that the assignments and zoning were made in the

interests of effectiveness and efficiency because, in their

view, Negroes police Negroes best. But, the cases, hold that

neither police efficiency nor savings to the taxpayer are

justification for the deprivation of constitutional rights.

In civil rights cases, the courts have uniformly placed

Fourteenth Amendment rights ahead of claims akin to

those of inefficiency, inconvenience and taxpayer expense.

Brown v. Board of Education, supra, decided four cases

on appeal, one of which was Davis v. County School Board,

103 F. Supp. 337 (E.D. Ya. 1952). In that case the dis

trict court held that the maintenance of segregated school

systems was justified on grounds, among others, that it

had provided greater opportunities for Negroes and that *

abolition of segregated schools would severely lessen the

interest of the people of the State in the public schools,

lessen the financial support, and so injure both races.

Placing constitutional rights ahead of these considerations,

the Supreme Court reversed.

21

Likewise, in Watson v. Memphis, 373 U.S. 526 (1963),

defendants argued that desegregation of a public park

system should be delayed and that gradual desegregation

was necessary in order to prevent interracial disturbances,

violence and community confusion and riots. The Supreme

Court rejected this argument stating (at p. 535):

“ . . . The compelling answer to this contention is that

constitutional rights may not he denied simply be

cause of hostility to their assertion or exercise. See

Wright v. Georgia, ante, p. 284; Brown v. Board of

Education, 349 U.S. 294, 300. Cf. Taylor v. Louisiana,

370 U.S. 154. As declared in Cooper v. Aaron, 358

U.S. 1, 16, ‘law and order are not . . . to be preserved

by depriving the Negro children of their constitutional

rights.’ This is really no more than an application

of a principle enunciated much earlier in Buchanan v.

Warley, 245 U.S. 60, a case dealing with a somewhat

different form of state-ordained segregation—enforced

separation of Negroes and whites by neighborhood.

A unanimous Court, in striking down the officially

imposed pattern of racial segregation there in ques

tion, declared almost a half century ago:

‘It is urged that this proposed segregation will

promote the public peace by preventing race con

flicts. Desirable as this is, and important as is the

preservation of the public peace, this aim cannot be

accomplished by laws or ordinances which deny

rights created or protected by the Federal Constitu

tion.’ 245 U.S., at 81.”

In Taylor v. Board of Education of City School District,

supra, where schools zones were gerrymandered, as Zone

13 is here gerrymandered, for racial purposes, the defen

dants argued in support of their refusal to eliminate the

22

racially drawn zones that there would be demonstrated

difficulties and that substantial costs to the taxpayers

would be involved. Those arguments were rejected by the

court. Likewise, in Clemons v. Board of Education of Hills

boro, 228 F.2d 853 (6th Cir. 1956), defendant’s contention

that such racially drawn and gerrymandered school zones

were necessary to avoid overcrowding in the schools was

rejected by the court.

Defendants here stand no better than defendants in the

above cited cases. Alleged police efficiency and savings to

the taxpayer cannot justify the deprivation of the plain

tiffs’ constitutional rights to equality and human dignity.

If police efficiency were a justification for the depriva

tion of constitutional rights, the police would be free to

coerce confessions from defendants, to conduct unlawful

searches and seizures and to deny to suspects the right to

consult counsel. But the courts have balanced these claimed

“efficiencies” against constitutional rights and have held

that where such a conflict exists, and a clear constitutional

right is violated, police efficiency- must give way. Most

recently, the Supreme Court dealt at length with the prob

lem of custodial police interrogation in Miranda v. Arizona,

384 U.S. 436 (1966). There, the court balanced a claim of

police efficiency in apprehending criminals against the

constitutional rights provided by the Fifth Amendment.

Speaking for the Court, Mr. Chief Justice Warren rvrote

(384 U.S. at p. 479):

“A recurrent argument made in these cases is that

society’s need for interrogation outweighs the privi

lege. This argument is not unfamiliar to this Court.

See, e.g., Chambers v. Florida, 309 U.S. 227, 240-241

(1940). The whole thrust of our foregoing discussion

demonstrates that the Constitution has prescribed the

23

rights of the individual when confronted with the

power of government when it provided in the Fifth

Amendment that an individual cannot be compelled

to be a witness against himself. That right cannot

be abridged. As Mr. Justice Brandeis once observed:

‘Decency, security and liberty alike demand that

government officials shall be subjected to the same

rules of conduct that are commands to the citizen.

In a government of laws, existence of the govern

ment will be imperilled if it fails to observe the law

scrupulously. Our Government is the potent, the

omnipresent teacher. For good or for ill, it teaches

the whole people by its example. Crime is con

tagious. If the Government becomes a lawbreaker,

it breeds contempt for law; it invites every man to

become a law unto himself; it invites anarchy. To

declare that in the administration of the criminal

law the end justifies the means . . . would bring

terrible retribution. Against that pernicious doctrine

this Court should resolutely set its face.’ Olmstead

v. United States, 277 U.S. 438, 485 (1928) (dissenting

opinion).”

The words of Mr. Chief Justice Warren and Mr. Justice

Brandeis have application here. As the Government teaches

the whole people by its example, so no Government or

Government agency should practice discrimination. If dis

criminatory practices, which deny to men their right to

equal opportunity, are to be ended, the Government must

lead. A free society is anchored in the concept of equality

before the law. To place police efficiency ahead of equality

is to destroy that concept and to destroy the fundamental

right of human dignity.

24

II.

A ssum ing Arguendo That D iscrim inatory Practices

May B e Justified by P o lice Efficiency, the D istrict Court

Erred in R equiring Plaintiffs to Show That D efendants’

A ctions W ere Arbitrary and Capricious. U nder a Cor

rect Standard o f P roof, D efendants Failed to Establish

Justification fo r T heir Practices.

A. Assuming Arguendo That Discrim inatory Practices May Be

Justified by Police Efficiency, the District Court Erred

in Requiring Plaintiffs to Show That Defendants’ Actions

W ere A rbitrary and Capricious.

Assuming arguendo, and contrary to law, that police

efficiency may constitutionally be used to justify defendants

discriminatory practices, the judgment of the district court

should still be reversed. In passing on the alleged justifi

cation, the District Court imposed an erroneous standard

of proof upon plaintiffs argument.

In its opinion, the district court held that the defendants,

in their assignment of Negro officers, had not acted in an

arbitrary or capricious manner and unless the plaintiffs

showed factually that defendants’ actions were arbitrary

or capricious, the court would not substitute its judgment

for theirs. In support of this view, the District Court

purported to rely upon two cases involving teacher assign

ments, Brooks v. School District of City of Moberly, 267

F.2d 733 (8th Cir. 1959) and Chambers v. Hendersonville

City Board of Education, 245 F. Supp. 759 (W.D. N.C.

1965). Not only are those cases clearly distinguishable on

their facts, but they support plaintiffs’ position.

Both cases are actions by Negro schoolteachers alleging

that they had been denied re-employment after their school

systems had been desegregated. In each case, the court

first examined the facts surrounding the refusal to re-

25

employ the Negro teachers and found that race played no

part in the decision not to re-employ them. In Brooks,

for example, the court stated (263 F.2d at p. 740):

“We find no positive evidence that the Board was influ

enced by racial considerations in the matter of em

ploying its teachers. Additionally, there are a number

of factors tending to negative any racial prejudice on

the part of the Board.”

Having found that race played no part in the decisions of

the defendants in those cases, the courts stated that they

would not substitute their judgment for that of the re

sponsible officials unless those officials acted in an arbi

trary or capricious manner. Thus, the courts in those cases

reached the question of whether arbitrary or capricious

actions were taken by public officials only after they had

determined that those actions were not taken on a racially

discriminatory basis.

In the case at bar, however, the court held that racially

discriminatory practices were justified and placed upon

plaintiffs the burden of showing that the alleged justifica

tion was not arbitrary or capricious. Under the rationale

of the District Court’s opinion, where a State agency or

State officials engage in discriminatory practices, and at

tempt to justify those practices on the grounds that they

are more efficient, the burden shifts to one who attacks

those practices to show that the alleged justification is not

arbitrary or capricious, to show that no reasonable man

could refuse to believe defendants’ evidence.

Under the rationale of the District Court’s opinion, a

burden is imposed upon plaintiffs suing to vindicate their

civil rights, rights which are the essence of citizenship,

more difficult than that imposed upon a plaintiff seeking

26

to establish a violation of the most unimportant contract.

The plaintiff in the contract case must prove the alleged

violation by a preponderance of the evidence; the plain

tiffs seeking to vindicate their constitutional rights against

discriminatory State action must show affirmatively that

the State and its officials acted arbitrarily and capriciously.

The result is anomalous and its implications ominous;

property rights are more easily vindicated than basic con

stitutional rights; the reach and effectiveness of the Four

teenth Amendment is substantially minimized.

Under the rationale of the District Court, the defendants

are permitted to justify their discriminatory practices on

what is virtually a bootstrap basis. So long as the dis

criminatory practices are, in the opinion of the Chief of

Police—who maintained the practices—justified as a mat

ter of efficiency, the practice is lawful.

But the rationale of the District Court is directly con

trary to rulings of the Supreme Court which hold that

where racial classifications, made by a State, State Agency

or State officials, are attempted to be justified on the

grounds that they promote the accomplishment of a per

missible State policy, the State bears tire burden of justi

fication. And, in order to sustain that burden, the State

must affirmatively show not merely that the classifications

are rationally related to the accomplishment of the per

missible policy, but that the policy cannot otherwise be

accomplished.

In Oyama v. California, 332 U.S. 633 (1948), the Court

held that a California statute, as applied, deprived peti

tioner of his rights under the Fourteenth Amendment by

discriminating against him, on the basis of his race, in the

right to hold land. The Supreme Court did not require

petitioner to show that the State’s action was arbitrary

27

and capricious as the district court did here. Instead, the

Court held (332 U.S. at p. 640):

“In our view of the case, the state had discriminated

against Fred Oyama; the discrimination is based

solely on his parents’ country of origin; and there is

absent the compelling justification which would be

needed to sustain discrimination of that nature.”

In Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954), the Supreme

Court declared public school segregation in the District

of Columbia to be unconstitutional, stating (347 U.S. at

p. 499):

“Classification based solely upon race must be scruti

nized with particular care, since they are contrary

to our traditions and hence constitutionally suspect.”

v Most recently, in McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184

(1964) the Court declared unconstitutional under the Four

teenth Amendment a Florida statute prohibiting unmar

ried mixed couples from living together under the same

roof habitually. Justice White, writing for the Court,

stated:

“Normally, the widest'discretion is allowed the legis

lative judgment in determining whether to attack some

rather than all, of the manifestations of the evil aimed

at; and normally that judgment is given the benefit

of every conceivable circumstance which might suffice

to characterize the classification as reasonable rather

than arbitrary and invidious, [citations] But we deal

here with a classification based upon the race of the

participants, which must be viewed in light of the

historical fact that the central purpose of the Four

teenth Amendment was to eliminate racial discrimina-

28

tion emanating from official sources in the States. This

strong policy renders racial classifications ‘constitu

tionally suspect’; Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497, 499;

and subject to the ‘most rigid scrutiny’, Korematsu

v. United States, 323 U.S. 214, 216; and ‘in most cir

cumstances irrelevant’ to any constitutionally accept

able legislative purpose, Hirabayashi v. United States,

320 U.S. 81, 100. Thus, it is that racial classifications

have been held invalid in a variety of contexts, [cita

tions]” 379 U.S. at p. 192.

* # # # #

“That a general evil will be partially corrected may,

at times, and without more, serve to justify the limited

application of a criminal law; but legislative discre

tion to employ the piecemeal approach stops short

of permitting a State to narrow statutory coverage

to focus on a racial group. Such classifications bear

a far heavier burden of justification.” Id. at p. 194.

# # * # #

“There is involved here an exercise of the state police

power which trenches upon the constitutionally pro

tected freedom from invidious official discrimination

based on race. Such a law, even though enacted pur

suant to a valid state interest, bears a heavy burden

of justification, as we have said, and will be upheld

only if it is necessary, and not merely rationally

related, to the accomplishment of a permissible state

policy.” Id. at p. 196.

The District Court in the case at bar did not require

the defendants to prove that their classification and as

signment of Negro officers was essential to the accomplish

ment of a valid state policy. Instead, it required plain

tiffs to show that the defendants did not act arbitrarily

29

and capriciously. For this reason alone, this court should

reverse.

B. Defendants Failed to Meet the Burden of Justifying Their

Racially Discriminatory Practice.

On the facts of this record, defendants have failed to

sustain their burden of showing that the racially discrimi

natory practices employed by them were essential to

police efficiency. No impartial expert testimony was ad

duced to show that any Negro policeman on the basis of

his race is better and more efficient in police work in a

Negro area than any white policeman. The defendants,

hoisting themselves by their own bootstraps, relied solely

upon the testimony of Chief Smith, the man who had con

tinued the longstanding customs complained of here. Chief

Smith testified that in his opinion these customs were

now justified because they promote efficiency. This opinion,

accepted on its face by the District Court, and unsup

ported by any further impartial evidence, is insufficient

to sustain defendants’ burden. Indeed, Chief Smith’s testi

mony shows conclusively that the racial classifications and

assignments made by the defendants are not essential to

efficient policing of the City.

For example, as we have indicated above, the logical

method of zoning the City would be to divide it into

separate adjoining areas. Zone 13, however, is superim

posed over four other zones, mainly Zone 12. Chief Smith

failed to explain why this method of zoning, which neces

sarily involves racial classifications, was the only way in

which to police the City efficiently. Indeed his principle

explanation for the special design of Zone 13 was:

“The only reason would be that it has always been

partially—this was brought down by custom” (R. 193).

30

On the question of the alleged superior efficiency of

Negro officers over any white officers in Zone 13, Chief

Smith testified that a white officer was as efficient as a

Negro officer in investigating or handling such things as

common accidents (R. 98). He was then asked by his

counsel:

“Q. What types of complaints could a colored officer

cope with much better than a white officer, in your

experience as a police officer? A. Well, primarily

where our biggest trouble has been, where you have

disorderly groups, drinking involved, you get large

crowds gathering, and the white officers will take much

more abuse from the bystanders than the negro officers

do. They get enough abuse from the citizens—” (R.

98).

Officer Crawford, on the other hand, who is assigned to

Zone 13, testified on cross-examination that Negro officers

have more difficulties in crowd situations in his area than

do the white officers:

“Q. Isn’t it true that the frequency that these

troubles occur happens to white police officers in that

Zone as it happens to you; isn’t it the same thing!

A. Yes, sir, it happens to both of us.

“Q. And as a matter of fact, doesn’t it happen more

to the white police officers than it does to the colored

police officers! A. No, sir, I wouldn’t say so.

“Q. You wouldn’t know, or you don’t say so! A.

I would say it happens more so to the negro officers -

than it does to the white officers.” (R. 156)

On the matter of locker assignments, the sole justifica

tion for segregation of the Negro lockers was that some

years ago, when there were four Negro policemen in the

31

Police Department, they agreed that they be assigned

adjoining lockers. No explanation was given, no justifica

tion was attempted for the subsequent assignment of lock

ers. Chief Smith testified that he would not hear a group

complaint on the matter but that he would “consider”

individual requests for a change “when space was avail

able”. Plainly, there is no justification in terms of effi

ciency for the assignment of lockers on a racial basis.

Nor is there a justification in terms of morale where most

of the Negroes, as shown by their institution of legal

action to change the procedure, do not wish assignments

to be made on a racial basis. Indeed, Chief Smith’s atti

tude in refusing to grant to plaintiffs their constitutional

rights, in his adamant refusal to desegregate even a por

tion of the Negro enclave in his Police Department, reflects

the attitude of defendants and shows the true motivation

for their discriminatory practices.

Finally, even if it be assumed, as Chief Smith did, that

all Negro officers were more efficient in policing Negro

areas than all white officers, the question remains as to

why Negro officers were assigned only to Zone 13 and why

no Negro officers have ever been assigned to Zone 12, which

is also a predominantly Negro area. Chief Smith was un

able to make any explanation in terms of efficiency. His

sole explanation, which also casts considerable light on the

motives of the defendants in making racial classifications,

was that he did not know why Negroes had never been as

signed to Zone 12 and that he had never even considered it

(E. 206).

As we have stated above, the record in this case shows

that there has been established in the St. Petersburg Police

Department, and particularly its Uniform Division, a sep

arate, segregated Negro enclave. This enclave has been

maintained, over the protests of the Negro officers in the

32

department, for many years. The present practices are

based upon a custom of segregation followed by the Police

Department since Negroes were first employed. Defendants

now contend that they do not engage in racial discrimina

tion but are motivated solely by a desire for efficiency.

But as the record shows, the practices challenged by this

action are not essential to police efficiency. The defendants

have not met their burden of showing that the City can

not be policed efficiently by methods other than those

racially discriminatory practices which they have adopted.

Finally, it should be kept clearly in mind that the justi

fication here offered by defendants^—police efficiency—is

being used to rationalize discriminations which arose out

of custom and habit. Negroes were originally sent to

patrol the Negro neighborhood, and were prohibited from

taking white persons to the station house (R. 44, 155), not

because it was more efficient to do things this way, but

because St. Petersburg practiced a policy of segregation

of which the organization of the Police Department was

simply a manifestation. We are now told, after the recent

Supreme Court decisions and the passage of the Civil

Rights Act, that, fortuitously, the old practices were really

the best ones; and we are told this principally by a Police

Chief who received his training in an admittedly segregated

Police Department under officials who instituted that ra

cially discriminatory policy, and who has introduced no

important changes in it. Under these circumstances, we

submit, it is impossible to conclude that St. Petersburg

has carried the burden of proving that the same old dis

criminations, practiced in. the same old way, are necessary

to efficient police enforcement.

33

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated above, the judgment of the dis

trict court should be reversed and the District Court

ordered to grant the relief prayed for by plaintiffs.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack G reenberg

L eroy D. Clark

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

J am es S a nderlin

1407 22 Street, South

St. Petersburg, Florida

Attorneys for Appellants

G ilbert S . E delson

A l a n S chw artz

Of Counsel

MEIIEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. 219