Shuttlesworth v Birmingham AL Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1967

113 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Shuttlesworth v Birmingham AL Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1967. 27ce7448-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/23391ff3-edcf-4998-92d2-0cac56e659f9/shuttlesworth-v-birmingham-al-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

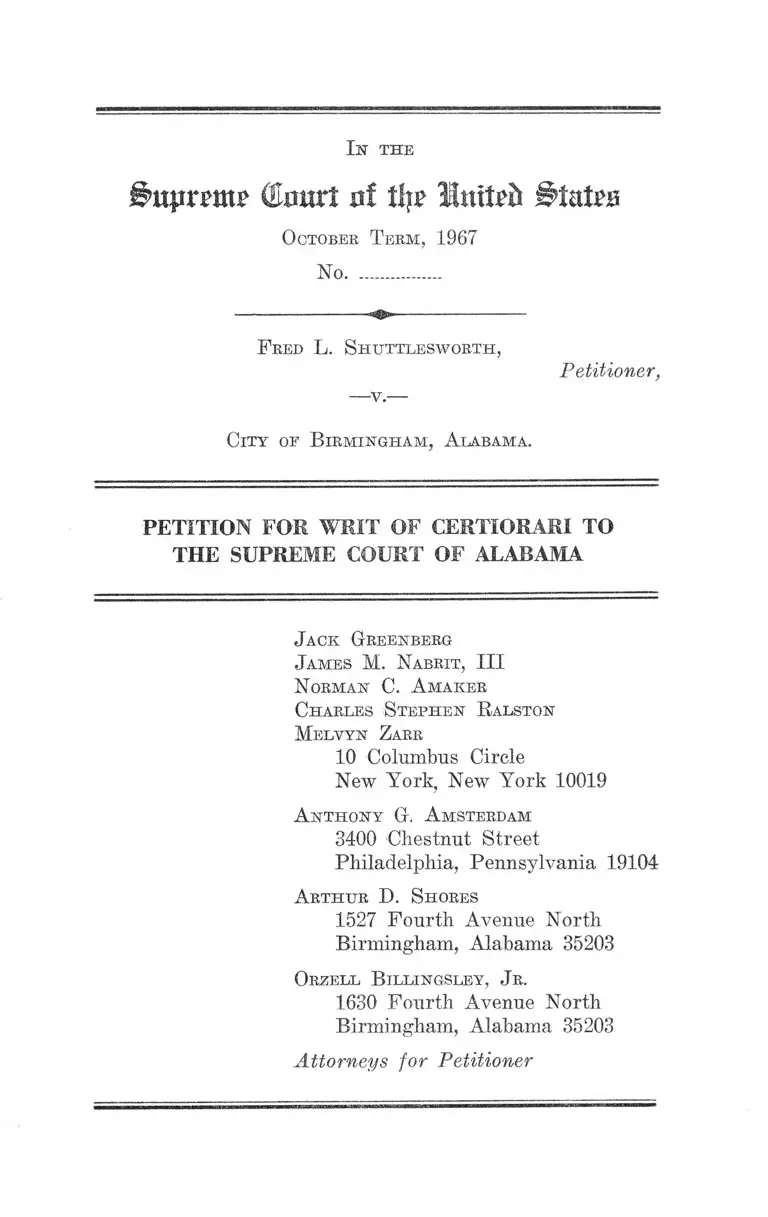

I n the

iB’ujirrmr Court of tljr luttrd 0tatro

O ctober T erm , 1967

No. ...............

------------------ — -------------- _ — ----------------------------------------------------------------

F red L. S h u ttlesw orth ,

Petitioner,

—v.—

City oe B ir m in g h am , A labam a .

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO

THE SUPREME COURT OF ALABAMA

J ack Greenberg

J am es M. N abrit , III

N orman C. A m aker

Charles S tephen R alston

M elvyn Z arr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A n t h o n y G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104

A rth u r D. S hores

1527 Fourth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

O rzell B illin gsley , J r .

1630 Fourth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Attorneys for Petitioner

Opinions Below

Jurisdiction ....

I N D E X

PAGE

1

2

Questions Presented.................................................... 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved.... . 3

Statement of the Case ....................... 4

How the Federal Questions Were Raised and De

cided Below .............................................................. 9

R easons for G ranting th e W rit

I. Certiorari Should Be Granted to Decide Whether

the Court Below Misapplied This Court’s Deci

sions in Walker v. City of Birmingham, 388 IT. S.

307 (1967), and Cox v. New Hampshire, 312

U. S. 569 (1941), so as to Bring Them Into Con

flict With Lovell v. Griffin, 303 U. S. 444 (1938)

and Stauh v. Baxley, 355 U. S. 313 (1958) ......... 11

II. Certiorari Should Be Granted to Decide Whether

the Decision Below Conflicts With Bouie v. Co

lumbia, 378 U. S. 347 (1964), Because Petitioner

Was Given No Fair Warning That He Was Re

quired to Secure a Parade Permit A) Because

Prior Decisions of This Court Taught Peti

tioner That He Need Not Submit to a Permit

Ordinance Patently Unconstitutional on Its Face

11

and B) Because Petitioner Only Participated in

a Peaceful, Orderly and Nonobstructive Walk

Along the Sidewalks of Birmingham................... 21

C onclusion ............... ............................................... ............ 26

A ppendix :

Opinion of the Supreme Court of Alabama....... .... la

Judgment of the Supreme Court of Alabam a....... 15a

Opinion of the Court of Appeals of Alabama....... 17a

T able op Cases

Baker v. Bindner, 274 F. Supp. 658 (W. D. Ivy. 1967) .. 15

Bantam Books, Inc. v. Sullivan, 372 U. S. 58 (1963) ..... 14

Borne v. Columbia, 378 U. S. 347 (1964) ...........21, 22, 24, 25

Cantwell v. Connectcwb, 310 U. S. 296 (1940) ............... 21

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U. S. 536 (1965) ......... 21

Cox v. New Hampshire, 312 TJ. S. 569 (1941) .......9,11,12,

13,14,18,

19, 22, 24, 25

Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U. S. 479 (1965) ....... ....... 14

Ducourneau v. Langan, 149 Ala. 647, 43 So. 187 (1907) 17

Freedman v. Maryland, 380 U. S. 51 (1965) ............... 16,21

Gamble v. City of Dublin, 375 F. 2d 1013 (5th Cir.

1967) ................................................................................. 15

Gober v. City of Birmingham, 373 U. S. 374 (1963) .... 5

Guyot v. Pierce, 372 F. 2d 658 (5th Cir. 1967) ............... 15

PAGE

I l l

PAGE

Hague v. C. I. 0., 307 U. S. 496 (1939) ........................... 21

In re Shuttlesworth, 369 U. S. 35 (1962) ................... 5

James v. United States, 366 IT. S. 213 (1961) ............... 22

Jones v. Opelika, 316 U. S. 584 (1942), dissenting opin

ions per curiam on rehearing, 319 U. S. 103 (1943) .... 21

Keyiskian v. Board of Regents, 385 IT. S. 589 (1967) .... 14

King v. City of Clarksdale, 186 So. 2d 228 (Miss. 1966) 15

Runs v. New York, 340 U. S. 290 (1951) ... ................... 21

Largent v. Texas, 318 IT. S. 418 (1943) ........................... 21

Lassiters. Werneth, 275 Ala. 555,156 So. 2d 647 (1963) 17

Lovell v. Griffin, 303 U. S. 444 (1938) ...................11,12,13,

18, 20, 21, 22

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 IT. S. 501 (1946) ................... 21

NAACP v. Button, 371 U. S. 415 (1963) ....... 14

Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 IT. S. 268 (1951) .............. 21

Primm v. City of Birmingham, 42 Ala. App. 657, 177

So. 2d 326 (Ct. App. Ala. 1964) ........... ....................... 23

Saia v. New York, 334 IT. S. 558 (1948) .......................... 21

Schneider v. State, 308 U. S. 147 (1939) ....................... 21

Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, 373 IT. S. 262

(1963) ............................................................................... 5

Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, 376 U. S. 339

(1964) ...................'..................... ...................................... 5

Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, 382 IT. S. 87

(1965) ......... ................................................ ..... 4, 5, 21, 22, 25

Staub v. Baxley, 355 IT. S. 313 (1958) ...................11,12,13,

18, 20, 21, 22

IV

Teitel Film Corp. v. Cusack, —— U. S. — —, 19 L. ed.

2d 966, January 29, 1968 ........................... -................... 16

Tucker v. Texas, 326 U. S. 517 (1946) .......................... 21

Walker v. City of Birmingham, 388 U. S. 307 (1967) ..5, 9,11,

12,14, 22

Other A uthorities

Code of Ala., Tit. 7, § 1072 .............................................. 16

Kalven, The Concept of the Public Forum. 1965 Su

preme Court Review, 1 ........ ......................................... 18

PAGE

I n the

S u p r e m e Glmtrt n f % U n ited S t a t e s

O ctober T erm , 1967

No..................

F red L. S h u ttlesw orth ,

■V.—

Petitioner,

C ity of B ir m in g h a m , A labam a.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO

THE SUPREME COURT OF ALABAMA

Petitioner Fred L. Shuttlesworth prays that a writ of

certiorari issue to review the judgment of the Supreme

Court of Alabama, entered in the above-entitled cause on

November 9, 1967.

Opinions Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Alabama is re

ported at 206 So. 2d 348. The opinion and judgment of the

Supreme Court of Alabama are set forth, Appendix, pp.

la-16a, infra. The opinions in the Court of Appeals of

Alabama, Sixth Division, are at 43 Ala. App. 68, 180 So.

2d 114 (1965), Appendix, pp. 17a-80a, infra.

2

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of Alabama was

entered November 9, 1967 (R. II, 24).1 On January 27,

1968, Mr. Justice Black extended the time in which to file

this petition for writ of certiorari to and including March

8, 1968.

Jurisdiction of the Court is invoked pursuant to 28

U. S. C. § 1257(3), petitioner having asserted below and

asserting here deprivation of rights, privileges and immuni

ties secured by the Constitution of the United States.

Questions Presented

1. Petitioner was convicted of parading without a per

mit, in violation of the Birmingham parade ordinance.

Petitioner had ignored the permit requirement because its

grant of overbroad discretionary licensing power rendered

it patently offensive to the First and Fourteenth Amend

ments and because there were no Alabama procedures for

effective and timely administrative decision-making and

judicial review. On appeal, after the Alabama Court of

Appeals had declared the ordinance unconstitutional on

its face and reversed petitioner’s conviction, the Supreme

Court of Alabama purported to excise the constitution

ally offensive portions of the ordinance, retroactively

validated it and affirmed petitioner’s conviction. Under

these circumstances, was petitioner denied due process of

law?

1 The record is in two volumes, herein designated as R. I (con

taining- the proceedings in the Court of Appeals of Alabama) and

R. II (containing the proceedings in the Supreme Court of Ala

bama).

3

2. Did the application of the Birmingham parade ordi

nance to petitioner deny him due process of law because

it provided him no fair notice that he was required to

secure a parade permit:

a) Because prior decisions of this Court taught peti

tioner that he need not submit to a permit ordinance

patently offensive to the First and Fourteenth Amend

ments which could not be saved short of repeal; and,

b) Because he had no fair notice that his participa

tion in a peaceful, orderly and nonobstructive walk

along the sidewalks of Birmingham would be held to

constitute a parade?

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

This case involves the First Amendment and Section 1

of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States.

This case also involves the following ordinance of the

City of Birmingham, a municipal corporation of the State

of Alabama:

General Code of C ity of B ir m in g h a m ,

A labama (1944), § 1159

It shall be unlawful to organize or hold, or to assist

in organizing or holding, or to take part or partici

pate in, any parade or procession or other public

demonstration on the streets or other public ways of

the city, unless a permit therefor has been secured

from the commission.

To secure such permit, written application shall be

made to the commission, setting forth the probable

4

number of persons, vehicles and animals which will be

engaged in such parade, procession or other public

demonstration, the purpose for which it is to be held

or had, and the streets or other public ways over,

along or in which it is desired to have or hold such

parade, procession or other public demonstration.

The commission shall grant a written permit for such

parade, procession or other public demonstration,

prescribing the streets or other public ways which may

be used therefor, unless in its judgment the public

welfare, peace, safety, health, decency, good order,

morals or convenience require that it be refused. It

shall be unlawful to use for such purposes any other

streets or public ways than those set out in said per

mit.

The two preceding paragraphs, however, shall not

apply to funeral processions.

Statement of the Case

This case tests the right of citizens of Birmingham,

Alabama to stand on, or walk along, the public sidewalks

of that city in a peaceful, orderly and nonobstructive

manner.2

Petitioner Fred L. Shuttlesworth, a Negro minister, is

a “ ‘notorious’ person in the field of civil rights in Birming

ham.” 3 Toward such a notorious person, “ [t]he attitude

2 Recently, in Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, 382 IJ. S.

87 (1965), the Court struck down petitioner Shuttlesworth’s con

viction under another Birmingham city ordinance which, literally

read, said that “a person ean stand on a public sidewalk in Bir

mingham only at the whim of any police officer of that city” (382

U. S. at 90).

3 Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, 382 U. S. 87, 102 (1965)

(concurring opinion of Fortas, / . ) .

5

of the city administration in general and of its Police

Commissioner in particular are a matter of public record,

of course, and are familiar to this Court from previous

litigation. See Slmttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, 382

U. S. 87 (1965); Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, 376

U. S. 339 (1964); Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham,

373 U. S. 262 (1963); Goher v. City of Birmingham, 373

U. S„ 374 (1963); In re Shuttlesworth, 369 U. S. 35

(1962).” 4

Petitioner Shuttlesworth seeks review of his conviction

for taking part in a peaceful protest demonstration in

Birmingham on Good Friday, April 12, 1963—a time “when

Birmingham was a world symbol of implacable official hos

tility to Negro efforts to gain civil rights, however peace

fully sought.” 5 Trials of approximately 1500 other demon

strators, charged, like petitioner, only under the Biiuning-

ham parade ordinance, are pending the outcome of this

case.

Good Friday was a pivotal day in the historic civil rights

campaign of petitioner Shuttlesworth and others involved

in the movement of that period. At about noon, a crowd

began to gather in a church in the 1400 block of Sixth

Avenue (R. I, 67). Police officers were stationed outside

to watch for signs of a demonstration (R. I, 35, 43, 48).

A large number of photographers (R. I, 53) and onlookers

gathered (R. I, 45).

At about 2 :15 p.m., 52 persons emerged from the church

(R. I, 41, 44-45).. They formed up in pairs on the side

4 Walker v. City of Birmingham, 388 U. S. 307, 325, n. 1 (1967 )

(dissenting opinion of Warren, C.J.).

5 Walker v. City of Birmingham, 388 U. S. 307, 338-39 (1967)

(dissenting opinion of Brennan, J.).

6

walk and began to walk in a peaceful, orderly and non

obstructive way toward City Hall (R. I, 35, 37, 39, 41,

44-46, 62-63, 65, 67).6 They walked about forty inches

apart, carried no signs or placards and observed all traffic

lights (R. I, 37, 39). At times they sang (R. I, 26, 35, 55).

Petitioner was not paired off; he was at times observed

near various points of the column, but at other times he

was not near the column at all (R. I, 25-26, 37, 39-40, 46-

48, 54-55, 61-62, 64-68, 70-71).

The walk proceeded about four blocks—to the 1700 block

of Fifth Avenue—where all the participants were arrested

(R. 25, 38, 45). The whole episode took 15 to 30 minutes

(R. I, 28). Petitioner was arrested some two hours later

at his motel (R. I, 71-72).

There was no evidence that petitioner had applied for a

parade permit. The parade permit book, a clerk in the

city Clerk’s office testified, contained no parade permit

for Good Friday (R. I, 31). The clerk testified that she

had never noticed—or issued a permit for—a “ parade” on

the sidewalks of Birmingham (R, I, 33). For example, it

was not the practice to issue permits for a group of Boy

Scouts forming up to board a bus (R. I, 33). The practice

was to issue permits for parades in the streets, having

bands and vehicles (R. I, 33). The following exchange oc

curred (R. I, 33):

Q. Mrs. Naugher, I believe you said you have been

clerk for seventeen years. A. Yes.

6 One police officer testified the group was 4 to 6 abreast (R. I,

23-24), but, in the context of his and other police officers’ testimony

(R. I, 40-41, 44-46, 56), it is clear that the Alabama Court of

Appeals was correct in concluding that this “bunching up coincided

with the promenaders being blocked by officers parking police cars

athwart the crossing” where they were arrested (R. I, 83).

7

Q. You have seen a number of these parades, haven’t

you? A. Yes.

Q. Have you noticed a parade down the streets or

on the sidewalk? A. In the streets.

Q. All in the street? A. Yes.

Q. And did you notice whether or not these parades

would have bands or vehicles in the procession? A.

Yes.

Q. They would? A. Yes.

Q. And does one get a permit to picket, or just to

parade? A. No.

Q. Does one get a permit to just walk down the

street? A. No.

Q, Do you know whether or not at time when a

group of Boy Scouts or Girl Scouts were going to load

up on the bus, whether or not they would have to get

a permit to get to the bus?

The Court: That would be a legal question and

she wouldn’t be competent.

Mr. Billingsley: The vital question is whether or

not—what she has in the book there.

A. We have not issued any.

The complaint against petitioner charged that he “ did

take part or participate in a parade or procession on the

streets of the City without having secured a permit there

for from the commission, contrary to and in violation of

Section 1159 of the General City Code o f Birmingham”

(E. I, 3).

October 1, 1963, petitioner was tried before a jury in the

Circuit Court of the Tenth Judicial Circuit, convicted and

sentenced to 90 days hard labor and an additional 48 days

8

hard labor for failure to pay the fine of $75.00 and costs

of $28.00 (E. I, 9-10).7

November 2, 1965, the Court of Appeals of Alabama,

Sixth Division, reversed petitioner’s conviction, holding

(E. I, 119-20; App., pp. 09a 70a, infra, 180 So. 2d 114, 140-

41):

(1) §1159 of the 1944 General Code of the City of

Birmingham, certainly as to the use of sidewalks by

pedestrians, is void for vagueness because of over

broad, and consequently meaningless, standards for

the issuance of permits for processions; (2) said § 1159

has been enforced in a pattern without regard to even

the meaning here claimed for by the City to such an

extent as to make it unconstitutional as applied to

pedestrians using the sidewalks; and (3) the City

failed to make a case, under the purported meaning

of § 1159, of there being a need for the appellant in

this case to be covered by a permit to use the sidewalk

in company with others.

November 9, 1967, the Supreme Court of Alabama re

versed the Court of Appeals, rejecting all three bases of

that court’s decision (E. II, 6-23; App., pp. la-14a, infra).

The Supreme Court held that § 1159 was not void on its

face (E. II, 20; App., p. 11a, infra), that §1159 had not

been unconstitutionally applied to petitioner (E. II, 20;

App., p. 11a, infra) and that there was sufficient evidence

7 Earlier, on May 15, 1963, petitioner was tried and convicted

in the Recorder’s Court of the City of Birmingham and sentenced

to 180 days hard labor and a fine of $100.00 (R. I, 2). From this

judgment, petitioner took an appeal to the Circuit Court for trial

de novo.

9

of petitioner’s violation of § 1159 (R. II, 21; App., p. 12a,

infra).

The Court based its holding upon this Court’s decisions

in Walker v. City of Birmingham,388 U. S. 307 (1967)

and Cox v. New Hampshire, 312 IT. S. 569 (1941) (R, II,

19-20; App., pp. lla-14a, infra). The Court held that

Walker and Cox required reversal of the Court of Appeals’

voiding of the Birmingham parade ordinance, notwith

standing this Court had explicitly refused to rule on the

ordinance’s validity (388 U. S. at 316-17). The Court con

ceded that its reliance upon Walker and Cox might be

misplaced,8 but concluded (R. II, 23; App., pp. 13a-14a,

in fra ): “ I f so, we will no doubt be set straight.” 9

How the Federal Questions Were

Raised and Decided Below

In the circuit court, petitioner raised the federal ques

tions presented here by demurrer (R. I, 4-5), by motion

to exclude the testimony and for judgment (R. I, 8, 59-60)

and motion for new trial (R. I, 12-14). All these motions

were overruled (R. I, 18, 60, 11).

The Court of Appeals of Alabama treated petitioner’s

assignment of errors (R. I, 80) as presenting the follow

ing three questions for decision (R. I, 82; App., p. 18a,

infra; 180 So. 2d at 116) ;

8 “Perhaps we have placed too much reliance on Walker v. City

of Birmingham, 388 U. S. 307 and on Cox v. New Hampshire, 312

U. S. 569. We may have misinterpreted the opinions in these

cases” (R. II, 23; App., pp. 13a-14a, infra).

9 On December 4, 1967, the Supreme Court of Alabama entered

a stay pending certiorari (R. II, 29-30).

10

(1) Whether § 1159, supra, denies, on its face, dne

process of law; (2) whether or not the ordinance as

applied violates Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356;

and (3) the sufficiency of the evidence.

These issues were resolved favorably to petitioner (R. I,

81-120; App., pp. 17a-70a, infra; 180 So. 2d 114-41), one

Judge dissenting (R. I, 121-29; App., pp. 70a-80a; 180

So. 2d 141-45).

The Supreme Court of Alabama stated the federal ques

tions presented in the following terms (R. II, 9; App., p. 3a,

infra): 1) Whether “ §1159 is void on its face because

of overbroad and consequently meaningless standards for

the issuance of permits for parades or processions” ; 2)

Whether § 1159 “has been enforced by the City of Birming

ham in such a way as to make it unconstitutional” ; and 3)

Whether “ the evidence adduced by the City of Birmingham

in the trial in the circuit court was insufficient to present

a jury question as to whether Shuttlesworth had, in fact,

been engaged in a parade, procession or other public

demonstration in the streets or other public ways of the

City of Birmingham without first having obtained a per

mit as required by § 1159.”

All these issues were resolved adversely to petitioner

on federal constitutional grounds (R. II, 6-23; App., pp.

la-14a, infra).

1 1

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I.

Certiorari Should Be Granted to Decide Whether the

Court Below Misapplied This Court’s Decisions in Walker

v. City of Birmingham, 388 U. S. 307 (1967), and

Cox x. New Hampshire, 312 U. S. 569 (1 9 4 1 ), so as to

Bring Them Into Conflict With Lovell v. Griffin, 303

U. S. 444 (1 9 3 8 ) and Staub v. Baxley, 355 U. S. 313

(1958).

In rejecting petitioner’s claim that the Birmingham

parade ordinance, § 1159 of the General City Code of

Birmingham, was unconstitutional on its face, the court

below placed great reliance upon this Court’s decision in

Walker v. City of Birmingham, 388 II. S. 307 (1967).10

Quoting a phrase in the Walker opinion to the effect that

“ it could not be assumed [§ 1159] . . . was void on its

face” (388 IT. S. at 317), the Alabama Supreme Court

held that Walker “ seems to us to be in direct conflict with

the conclusion reached in the majority opinion of the Court

of Appeals of Alabama here under review” (R. II, 19-20;

App., p. 11).

But to read Walker as supporting the facial constitu

tionality of a licensing ordinance such as § 1159 is a dan

gerous distortion of this Court’s decision which the Court

should quickly correct before it gains currency in the lower

courts. In Walker, the Court merely refused to disturb

Alabama’s ruling that the validity of the ordinance and

the injunction embodying it could not be tested in a crim

inal contempt proceeding. It was in this context that

10 R. II, 16-23; App., pp. 9a-14a, infra.

1 2

the prevailing opinion said that the ordinance could not

“be assumed” to be void. The Court was thus far from

sustaining the constitutionality of §1159 ; to the contrary,

it noted that the “ generality” of the ordinance’s language

unquestionably raised “ substantial constitutional issues”

(388 U. S. at 316). And the Chief Justice, in a dissenting

opinion which Justices Brennan and Fortas joined, ex

pressed the belief that § 1159 was “patently unconstitu

tional on its face” (388 U. S. at 328).

The effect of the decision below is to convert Walker

and Cox v. New Hampshire, 312 U. S. 569 (1941), into a

two-pronged instrument for the validation and perpetua

tion of unconstitutional licensing regimes. If this device

succeeds, it will effectively destroy the salutary principle

long adhered to by this Court as an indispensable element

of the protection afforded free expression against imper

missible censorship: the principle of cases such as Lovell

v. Griffin, 303 IT. S. 444 (1938), and Staub v. Baxley, 355

U. S. 313 (1958), that a facially unconstitutional licensing

law is wholly void and need not be complied with.

Under § 1159 as written, and as it confronted petitioner

Shuttlesworth in 1963, the Birmingham licensing author

ity is granted power to withhold a parade permit if “ in

its judgment the public welfare, peace, safety, health,

decency, good order, morals or convenience” require it. A

more explicit grant of unconstitutional censorial power

can hardly be imagined.11 If, in supposed reliance upon

11 “When local officials are given totally unfettered discretion to

decide whether a proposed demonstration is consistent with ‘public

welfare, peace, safety, health, decency, good order, morals or con

venience,’ as they were in this case, they are invited to act as censors

over the views that may be presented to the public” ( Walker v. City

of Birmingham, supra, 388 U. S. at 329) (dissenting opinion of

Warren, C.J.). See authorities collected in note 15, infra.

13

Walker, such an ordinance can be retroactively rewritten

so as to save its constitutionality by excising most of its

operative language, there is no licensing legislation that

cannot be similarly sustained. And if, as the court below

interpreted the doctrine of Cox, the post-operative shape

of the legislation warrants imposing criminal liability

upon those who read it as it was written and decline to

comply with a palpably unconstitutional censorship scheme,

the consequence is clear and frightening. Lovell v. Griffin

is dead; Stciub v. Baxley is dead; every licensing regula

tion—however broad the discretionary porver it appears

to confer upon the licensing authorities over the activities

of the persons required to be licensed—must be obeyed.

The resultant damper on constitutionally guaranteed

freedoms of expression is obvious. The States are per

mitted and encouraged to hold out a broad and overhang

ing threat of greater censorship than the Constitution

permits them to exact. So long as the threat is effective

and fear of attendant criminal penalties discourages chal

lenge to it, the censorship exerts its full, unconstitutional

repressive effect. When and if a challenge is mounted,

the state courts (which may or may not be the highest

court of a state) announce that the statutory regulation

does not mean Avhat it plainly says, and—-without remov

ing the overbroad language from the statute books, where

it remains to be invoked by the licenser and to cow laymen

subject to regulation under it—give it some post hoc verbal

construction designed and sufficient to bring it barely back

across the line of constitutional condemnation.

Just this sort of regulation of speech conduct, wherein a

State undertakes to threaten by ostensible prohibition a

broader range of protected activities than it can eonstitu-

14

tionally restrict, has been voided by this Court in numerous

contests other than licensing laws. E.g., Bantam Boohs,

Inc. v. Sullivan, 372 U. S. 58 (1963); N. A. A. C. P. v. But

ton, 371 U. S. 415 (1963); Dombrowshi v. Pftster, 380 U. S.

479 (1965); Keyishian v. Board of Regents, 385 U. S. 589

(1967). Its emergence in the licensing area, under the

aegis of Cox v. New Hampshire and the Walker decision

as construed below, we submit, poses a menace to First

Amendment freedoms that this Court should now review.

In saying this, we do not for a moment question the

soundness of the basic Cox principles: that it is constitu

tionally permissible for a State or a municipality to require

that parades be licensed, under proper standards and pro

cedures; and that persons who parade without the license

required by valid legislation may be criminally punished

consistent with the Constitution. But, as appears from the

decision below, those basically sound principles afford

substantial opportunities for abuse, and therefore require

at least occasional review by this Court of their adminis

tration, so as to assure that they are restricted to their

proper compass. We respectfully suggest that the time is

now ripe for a review of the question of what limitations

must effectively be placed on a municipal licensing scheme

in order to bring it within the validating principles of

Cox, and that the present case presents a peculiarly fit

occasion for that review.

For it is clear that what the Alabama Supreme Court

has done here is retroactively to validate some 1500 crimi

nal charges, plainly impermissible incidents of an uncon

stitutional licensing procedure when made, by wrapping

them about with the mere verbal habiliments of the Cox

opinion. Not only does this have the effect of legalizing

15

the illegal conduct of the Birmingham authorities—and

illegalizing the legal conduct of the 1500 Birmingham civil

rights demonstrators—in 1963; it also leaves Birmingham

Code § 1159 and literally hundreds of cognate statutes

and ordinances12 lying about like so many traps against

future free speech activity. Even in the case of § 1159

itself, which now has been given an authoritative if belated

limiting construction, the danger of irremediable uncon

stitutional application remains intense, both because of the

gap between the limiting construction and what the face

of the ordinance appears to countenance, and because of

the absence in Alabama of any administrative or judicial

machinery serviceable to make the limiting construction

anything more than verbal. And, of course, the danger is

greater still in the case of other, similar but as yet uncon

strued licensing statutes and ordinances, to which the effect

of the decision below is to enforce compliance.

These dangers are apparent upon consideration of the

alternatives open to the citizen wishing to participate in a

“ parade’1 (assuming arguendo that a citizen has fair warn

ing of what constitutes a “ parade,” see II B, infra), under

such a statute or ordinance:

1. The citizen can submit to the issuer’s discretion

and, if his permit application is denied, can attempt

to seek review of this denial; or,

12 Statutes and ordinances creating broadly discretionary licens

ing regimes appear to be ubiquitous, notwithstanding this Court’s

repeated condemnation of them (see note 15, infra). The Jackson

ordinance condemned in Ouyot v. Pierce, 372 F. 2d 658 (5th Cir.

1967), for example, was a portion of the Uniform Traffic Code. See

also, e.g., Baker v. Bindner, 274 F. Supp. 658 (W. D. Ky. 1967) ;

King v. City of Clarksdale, 186 So. 2d 228 (Miss. 1966) ; Gamble

v. City of Dublin, 375 F. 2d 1013 (5th Cir. 1967).

16

2. The citizen can refuse to make application for a

parade permit and attempt to challenge the regime of

the ordinance if he is prosecuted for parading without

a permit.

The second alternative is plainly foreclosed by the de

cision below. As we have pointed out, if Birmingham Code

§ 1159 can be retroactively rewritten and thereby validated

by judicial construction in a criminal prosecution, any

licensing legislation can. All must therefore be obeyed.

But the remaining alternative—to obey and seek a per

mit—is an equally repressive requirement, for several

reasons. In the first place, a system of enforced compli

ance with overbroad licensing laws presents no real means

of challenging their coercive effect because in practice it

preserves wide-open, operative and unchallengeable the

discretion in the issuer of parade permits. Alabama is no

exception. In Alabama, judicial review is theoretically

available by way of mandamus, see Code of Ala., Tit. 7,

§ 1072, but that remedy is largely ineffective because there

is no requirement of dispatch, compare Freedman v. Mary

land, 380 U. S. 51 (1965) and Teitel Film Corp. v. Cusack,

------ U. S. ------ , 19 L. ed. 2d 966, January 29, 1968, and

because the citizen must overcome a nearly impossible

burden of showing that administrative discretion has been

abused:

“ To warrant the issuance of mandamus, not only

must there be a legal right in the relator, but, owing

to the extraordinary and drastic character of man

damus and the caution exercised by courts in award

ing it, it is also important that the right sought to

be enforced be clear and certain, so as not to admit

of any reasonable controversy. The writ does not

/r f t ' ' r , *>/

i, j . i '• r . t / v .r 4% h r i > -r. « /*

€> < ©J) c 44

17

issue in eases where the right in question is doubt- ]

ful. . . . ” Lassiter v. Werneth, 275 Ala. 555, 156 So. 2d

647, 648 (1963); see also Ducourneau v. Lang an, 149

Ala. 647, 43 So. 187 (1907).

The facts that the administrative decision challenged is

not required to be made on a record of regular procedures;

or to be supported by any statement of reasons; and that

there is not even required to be kept any administrative

log or recording of permit grants and denials (R. I, 32),

make virtually insuperable the difficulty of proving a case

of judicially revisable arbitrary or discriminatory enforce

ment. This, together with the prospect of delay involved

in judicial challenge, makes reversal of the denial of a

permit application in any particular case highly unlikely.

And, in any event, no general construction of the overbroad

permit law is assured by this route; while facial challenge

to it is, of course, denied.

But, there is, in the second place, good reason why this

Court has long endorsed the principle that citizens should

be free to refuse to submit to a licensing scheme which

has a coercive effect upon First Amendment rights. These

overbroad laws are numerous and their prior restraints

affect large numbers of people who cannot be supposed to

have the knowledge and resources to combat them by pro

longed administrative and judicial challenge. In this case

alone, 1500 people were subjected to the prior restraints

of the Birmingham parade ordinance.. If they had sought

parade permits under the ordinance, it was and is specula

tive what construction would have been put upon § 1159

by the Birmingham authorities or the Alabama courts, or

how long the demonstrators would have been in court be

fore obtaining any construction. One thing, we think, is

18

clear: there would have been no civil rights Easter

marches in Birmingham in 1963. It was not heedlessly, we

suggest, that Lovell v. Griffin, 303 U. S. 444, 452-53 (1938)

and Staub v. Baxley, 355 U. S. 313, 319 (1958), stated this

Court’s preference for allowing challenges to the whole

regime created by such overbroad licensing laws. The

Court recognized that only by facilitating challenges to the

law itself could its coercive sting be removed.

Third, Birmingham Code § 1159, in its effective opera

tion in 1963 and by its language on the books today, ex

pressly embodies an unconstitutionally broad grant of

censorial licensing power. This was not the case, it should

be noted, of the ordinance challenged in Cox. The Cox

ordinance merely provided that licenses for parades and

certain other gatherings must be obtained. Not surpris

ingly, the New Hampshire Supreme Court held that the

discretion of the issuer of parade permits was governed

by the standard of considerations of time, place and man

ner in order “to prevent confusion by overlapping parades

or processions, to secure convenient use of the streets by

other travelers, and to minimize the risk of disorder.”

Cox v. New Hampshire, 91 N. H. 137, 144, 16 A. 2d 508,

514 (1940), quoted with approval, 312 IT. S. at 576. The

New Hampshire Supreme Court relied on “ the unbeatable

proposition that you cannot have two parades on the same

corner at the same time” 13 and, of course, this Court

agreed.

Thus, the problem not presented in Cox but presented

here is how to remedy a parade permit law which on its

face appears to grant to officials far more discretionary

13 Kalven, The Concept of the Public Forum, 1965 Supreme

Court Review, 1, 25.

19

licensing power than the Constitution allows. The verbal

solution offered by the court below—eliminating the stand

ards of “public welfare,” “peace,” “ safety,” “health,” “ de

cency,” “ good order” and “morals” and keeping only the

standard of “ convenience” (R. II, 16; App., p. 8a, infra)—

is a plainly unsatisfactory remedy, at least as applied in

petitioner’s case. True, the court below took great pains

to chop off the language of the Birmingham parade ordi

nance and to substitute for it the language of this Court

and the New Hampshire Supreme Court in Cox.u But that

disposition— operating post facto on the past and with

speculative and unassured efficacy for the future—hardly

cures the problem. Birmingham’s licensers still have the

unchanged face of the Code to point to in their dealings

with citizens; and if those dealings are abusive, no ade

quate machinery is available to convert the Alabama

Supreme Court opinion below into an effective and en

forceable restraint upon the day-to-day reality of the li

censing system.

The foregoing considerations put into focus the trouble

with the disposition by the court belowr: it punishes the

citizen who, by daring to challenge an overbroad prior

restraint, succeeds in having it limited to proper constitu

tional bounds. This punishment is the reward of that

citizen although, in Alabama, his challenge is the only 14

14 The standards stated in the Alabama Supreme Court’s opinion

are lifted without citation from the New Hampshire Supreme

Court’s opinion, viz., that the discretion must be exercised with

“uniformity of method of treatment upon the facts of each appli

cation, free from improper or inappropriate considerations and

from unfair discrimination. A systematic, consistent and just order

of treatment, with reference to the convenience of public use [of

the highways]” must be followed (91 N. IT. at 143, 16 A. 2d at

513; R. II, 16; App., p. 8a).

20

effective way to curb the coercive effects of an overbroad

prior restraint such as the Birmingham parade ordinance.

We do not see how such a result can be squared with the

principle of this Court’s Griffin and Staub decisions. Per

haps in cases where the machinery of administrative deci

sion-making and judicial review is clearly established, ef

fective and timely to restrict broad prior restraints, the

Griffin-Stcmb right to be wholly free of those restraints

may be abrogated. But that is not the case here. The

Alabama Supreme Court may have adopted the Cox lan

guage; it has not yet adopted procedures adequate to in

sure effective respect for the Cox principle of “uniformity

of method of treatment upon the facts of each applica

tion, free from improper or inappropriate considerations

and from unfair discrimination” (see note 14, supra).

Whether, without such procedures, its ostensible conform

ance to Cox’s constitutional standards satisfies Cox and the

Constitution, presents a question of great moment which

this court should grant certiorari to decide.

21

II.

Certiorari Should Be Granted to Decide Whether the

Decision Below Conflicts With Bouie v. Columbia, 378

U. S. 347 (1964), Because Petitioner Was Given No

Fair Warning That He Was Required to Secure a Parade

Permit A) Because Prior Decisions of This Court

Taught Petitioner That He Need Not Submit to a Permit

Ordinance Patently Unconstitutional on Its Face and

B) Because Petitioner Only Participated in a Peaceful,

Orderly and Nonobstructive Walk Along the Sidewalks

of Birmingham.

A. Five years ago, petitioner was confronted with a

parade ordinance which granted power to Birmingham

officials to withhold a parade permit if “ in [their] . . .

judgment the public welfare, peace, safety, health, decency,

good order, morals or convenience” required it.

Leaving aside the question whether petitioner could fore

see that the ordinance had any application to his activities

(discussed in II B, infra), petitioner had ample authority

in the decisions of this Court15 to be “ [u]nable to believe

15 Cox v. Louisiana, 379 II. S. 536, 553-558; Lovell v. Griffin, 303

U. S. 444, 447, 451; Hague v. C. I. 0., 307 U. S. 496, 516; Schneider

v. State, 308 U. S. 147, 157, 163-164; Cantwell v. Connecticut,

310 U. S. 296, 305-307; Largent v. Texas, 318 U. S. 418, 422; Marsh

v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501, 504; Tucker v. Texas, 326 U. S. 517, 519-

520; Saia v. New York, 334 U. S. 558, 559-560; Kunz v. New York,

340 U. S. 290, 294; Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U. S. 268, 271-272;

Staub v. Baxley, 355 U. S. 313, 322-325; Jones v. Opelika, 316

U. S. 584, 600-603 (Stone, C.J. dissenting), 611, 615 (Murphy, J.

dissenting), dissenting opinions adopted per curiam on rehearing,

319 U. S. 103, cf. Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham, 382 U. S. 87, 90;

Freedman v. Maryland, 380 U. S. 51, 56.

22

that such a blatant and broadly drawn prior restraint

on . . . First Amendment rights could be valid.” 18

Moreover, petitioner had good reason to believe that the

Griffin-Staub principle discussed in Part I, supra, allowed

him to refuse to submit to and then challenge this blatant

and broadly drawn prior restraint on First Amendment

rights. Even if the Alabama Supreme Court’s judicial

repealer of § 1159 is held to meet the Cox standards, and

even if the Griffin-Staub principle is held not to shield from

punishment those citizens who succeed, by challenging

such a blatant prior restraint, in limiting it, at least peti

tioner and the 1500 other Birmingham civil rights demon

strators arrested in the Easter week, 1963 marches should

not be punished for their reliance upon this principle.

Punishment of this sort, for conduct expressly validated

by long-settled and repeated decisions of the highest Court

of the land, would plainly affront the ordinary principles

of mens rea common to the criminal law. Cf. James v.

United States, 366 U. S. 213 (1961). We submit that it

would violate, as well, the rudimentary guarantee of fair

notice imposed on state criminal procedure by the Due

Process Clause, see Bouie v. Columbia, 378 IJ. S. 347 (1964),

and urge that certiorari be granted to so decide.

B. Petitioner was convicted for taking part in a peace

ful protest demonstration consisting of 52 persons walking

two abreast in an orderly and nonobstructive manner on

the public sidewalks of Birmingham, Alabama. His crime

was that he had not obtained a permit from Birmingham

authorities to do so. 16

16 Walker v. City of Birmingham, supra, 388 U. S. at 327 (opin

ion of Warren, C.J.).

23

In the courts below, petitioner maintained that there

was insufficient evidence to sustain the charge that he

participated in “ a parade or procession on the streets of

the city” (Complaint, R. I, 3). Put another way, peti

tioner denied that he required a parade permit to do what

he did.

The Court of Appeals of Alabama agreed, holding (R. I,

116, 118; 180 So. 2d at 139; App., pp. 65a, 67a, infra):

Here, we consider the proof . . . fails to show a

procession which would require, under the terms of

§ 1159, the getting of a permit.

# # # * = *

We emphasize that we have only before us a walk

ing on city sidewalks. In the use of the roadway

probably less stringent standards of construction

would prevail against the prosecutor.

This holding was fully consistent with the history of the

operation and enforcement of § 1159. The permit-issuing

authorities did not issue permits for walking on the side

walk (R. I, 33). The police did not usually arrest persons

for walking on the sidewalks; when they did, the courts

did not sustain such convictions.17

Notwithstanding the prior operation, enforcement and

construction of § 1159, the Supreme Court of Alabama

held that there was sufficient evidence of a “parade” to

constitute a violation of the ordinance (R. II, 21; App.,

17 See Primm v. City of Birmingham, 42 Ala. App. 657, 177 So. 2d

326 (Ct. App. Ala. 1964).

24

p. 12a, infra).18 In doing so, the court below brought itself

into conflict with the doctrine of Bowie v. Columbia, 378

IT. S. 347 (1964).

In Bouie, the Court held violative of the due process

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment convictions under a

statute which had been “unforeseeably and retroactively

expanded by judicial construction” (378 U. S. at 352).

Prior to the Supreme Court of Alabama’s decision in this

case, the term “parade” had a fairly certain meaning in

Birmingham. A “ parade” included bands and vehicles (R.

I, 33); it occurred in the streets, not on the sidewalks

(R. I, 33); it contained, the ordinance assumed, “persons,

vehicles and animals.”

Otherwise, there would be little justification for having

a permit system at all. A permit system is justified by the

fact that a person wishing to hold a “ parade” , in the ac

cepted sense, i.e., with bands and/or vehicles, requires the

exclusive enjoyment of particular streets at a particular

time. A permit system gives “ the public authorities notice

in advance so as to afford opportunity for proper policing”

(Cox v. New Hampshire, supra, 312 II. S. at 576).

That rationale has no application here. It is undisputed

that petitioner’s use of the sidewalks of Birmingham at

approximately 2 :15 p.m. on April 12, 1963, was in no way

inconsistent with the use by other citizens of Birmingham

of those very same sidewalks at that very same time. The

Court of Appeals correctly held (R. I, 117; 180' So. 2d at

139; App., p. 66a, infra) :

18 “We see no occasion to deal at length with the holding . . .

[below] that the evidence was insufficient to show that Shuttles-

worth had engaged in a parade . . . ” (R. II, 21; App., p. 12a, infra).

25

The City failed to show whether or not other pedes

trians were run off the sidewalk, blocked either in

access, process or transit.19

Having reference then to the theory and practice of the

Birmingham parade ordinance, petitioner had no fair warn

ing that his participation in a peaceful, orderly and non-

obstructive walk on the sidewalks of Birmingham required

a parade permit.

Petitioner may now be on notice for the future. It may

now be that football fans on their way to the stadium with

out a parade permit risk prosecution under § 1159, should

city authorities “ choose so vigorously to protect the side

walks of Birmingham.” 20 Whether or not21 that is now the

state of the law, one thing is clear: The court below’s un

foreseeable and retroactive application of the Birmingham

parade ordinance to petitioner appears inconsistent with

Bouie v. Columbia, supra.

19 Cf. Cox v. New Hampshire, supra, 312 U. S. at 573:

The marchers interfered with the normal sidewalk travel, but

no technical breach of the peace occurred.

20 Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham, 382 U. S. 87, 100 (1965) (con

curring opinion of Fortas, / . ) .

21 “ If one were to confine oneself to the surface version of the

facts, a general alarm for the people of Birmingham would be in

order. Their use of the sidewalks would be hazardous beyond

measure.” Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham, 382 U. S. 87, 101 (1965)

(concurring opinion of Fortas, J.).

26

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the petition for writ of

certiorari should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack G reenberg

J am es M. N abrit , I I I

N orman C. A m aker

C harles S tephen R alston

M elvyn Z arr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A n th o n y G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104

A rth u r D. S hores

1527 Fourth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Orzell B illin gsley , J r .

1630 Fourth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Attorneys for Petitioner

A P P E N D I X

la

APPENDIX

Opinion of the Supreme Court of Alabama

THE SUPREME COURT OF ALABAMA

T h e S tate of A labam a— J udicial D epartm ent

O ctober T erm 1967-68

November 9, 1967

6 Div. 291

---------------------------- — —— — --- ----------------------- -- -

Ex parte City of Birmingham

In re F red L. S h u ttlesw orth

—v.—

C ity of B ir m in g h a m .

petition for certiorari to court of appeals

L aw son , Justice.

Fred L. Shuttlesworth was convicted in the Recorder’s

Court of the City of Birmingham of parading without a

permit in violation of §1159 of the General City Code of

Birmingham, hereinafter referred to as §1159, which reads:

“ It shall be unlawful to organize or hold, or to as

sist in organizing or holding, or to take part or par

ticipate in, any parade or procession or other public

2 a

demonstration, on the streets or other public ways of

the city, unless a permit therefor has been secured

from the commission.

“ To secure such permit, written application shall be

made to the commission, setting forth the probable

number of persons, vehicles and animals which will

be engaged in such parade, procession or other public

demonstration, the purpose for which it is to be held

or had, and the streets or other public ways over, along

or in which it is desired to have or hold such parade,

procession or other public demonstration. The com

mission shall grant a written permit for such parade,

procession or other public demonstration, prescribing

the streets or other public ways which may be used

therefor, unless in its judgment the public welfare,

peace, safety, health, decency, good order, morals or

convenience require that it be refused. It shall be un

lawful to use for such purposes any other streets or

public ways than those set out in said permit.

“ The two preceding paragraphs, however, shall not

apply to funeral processions.”

The word “commission” as used in §1159 refers to the

governing body of the City of Birmingham.

Following his conviction in the Recorder’s Court,

Shuttlesworth appealed to the Circuit Court of Jefferson

County, where there was a de novo trial before a jury.

The jury found Shuttlesworth guilty and the trial court,

after rendering a judgment in accordance with the verdict

of the jury, sentenced Shuttlesworth to pay a fine of $75

and to perform ninety days hard labor for the City of

Birmingham.

3a

Shuttlesworth then appealed to the Court of Appeals of

Alabama which court, in a two-to-one decision, reversed

the judgment of the Circuit Court of Jefferson County and

rendered a judgment discharging Shuttlesworth “ sine die.”

Judge Cates wrote the majority opinion, in which Presid

ing Judge Price concurred. Judge Johnson dissented.—

Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, 43 Ala, App. 68, 180

So. 2d 114.

The City of Birmingham fded petition in this court for a

writ of certiorari to review and revise the opinion and

judgment of the Court of Appeals. We granted the writ.

While we are not altogether certain as to the exact rea

sons why the majority of the Court of Appeals concluded

that Shuttlesworth’s conviction should be reversed and that

he should be discharged sine die, we will treat that opinion

as holding that §1159 is void on its face because of over

broad and consequently meaningless standards for the issu

ance of permits for parades or processions; that said sec

tion has been enforced by the City of Birmingham in such

a way as to make it unconstitutional under the holding of

the Supreme Court of the United States in Yick Wo v.

Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356, 6 S. Ct. 1064, 30 L. Ed. 220; that

the evidence adduced by the City o f Birmingham in the

trial in the circuit court was insufficient to present a jury

question as to whether Shuttlesworth had, in fact, been

engaged in a parade, procession or other public demon

stration in the streets or other public ways of the City of

Birmingham without first having obtained a permit as re

quired by §1159.

In view of the fact that there was a dissenting opinion,

we have gone to the original record to determine the facts.

The majority opinion of the Court of Appeals does not

contain a complete statement of the facts. However, the

4a

dissenting opinion of Judge Johnson contains a rather

lengthy recitation of the facts and our examination of the

original record shows that the facts as stated in the dis

senting opinion are fully supported by the record.

The dissenting opinion, unlike the majority opinion of

the Court of Appeals, takes cognizance of the rule so often

stated by the appellate courts of this state, to the effect

that it is the duty of courts not to strike down a city ordi

nance or a statute as unconstitutional, if by reasonable con

struction it can be given a field of operation within con

stitutional limits and that where a statute or ordinance is

susceptible of two constructions, one of which will defeat

the ordinance or statute and the other will uphold it, the

latter construction will be adopted.

With that rule in mind, Judge Johnson proceeds to con

strue §1159, saying:

“ I think it is obvious that this ordinance— Section

1159'—was not designed to suppress in any manner

freedom of speech or assembly, but to reasonably regu

late the use of the streets in the public interest. If

does not seek to control what may be said on the

streets, and is applicable only to organize [sic] for

mations of persons, vehicles, etc., using the streets and

not to individuals or groups not engaged in a parade

or procession. The requirement that the applicant for

a permit state the course to be travelled, the probable

number of persons, vehicles and animals, and the pur

pose of the parade is for the purpose of assisting

municipal authorities in deciding whether or not the

issuance of a permit is consistent with traffic condi

tions. Thus, the required information is related to the

proper regulation of the use of the streets, and the

fact that such information is required indicates that

5a

the power given the licensing authority was not to be

exercised arbitrarily or for some purpose of its own.

The requirement that the applicant state the purpose

of the parade or procession does not indicate an intent

to permit the Commission to act capriciously or arbi

trarily. The purpose may have a bearing on precau

tions which should be taken by municipal authorities

to protect parades or the general public.

“ Section 1159, supra, provides that the Commission

shall issue a permit ‘unless in its judgment the public

welfare, peace, safety, health, decency, good order,

morals or convenience require that it be refused.’ I do

not construe this as vesting in the Commission an un

fettered discretion in granting or denying permits, but,

in view of the purpose of the ordinance, one to be

exercised in connection with the safety, comfort and

convenience in the use of the streets by the general

public. The standard to be applied is obvious from the

purpose of the ordinance. It would be of little or no

value to state that the standard by which the Commis

sion should be guided is safety, comfort and conven

ience of persons using the streets, and, due to varying

traffic conditions and the complex problems presented

in maintaining an orderly flow of traffic over the

streets, it would be practically impossible to formu

late in an ordinance a uniform plan or system relat

ing to every conceivable parade or procession. The

members of the Commission may not act as censors

of what is to be said or displayed in any parade. If

they should act arbitrarily, resort may be had to the

courts. It is reasonable to assume from the facts in

this case that the Commission would have granted ap-

6a

pellant a permit to engage in the parade if such per

mit had been sought. A denial would have been war

ranted only if after a required investigation it was

found that the convenience of the public in the use

of the streets at the time and place set out in the

application would be unduly disturbed” (180 So. 2d,

144).

We agree with and adopt the construction which Judge

Johnson has placed on §1159 and we agree with his obser

vations to the effect that such construction finds support

in the case of State v. Cox, 91 N. H. 137, 16 Atl. 2d 508,

which case was affirmed, in a unanimous decision, by the

United States Supreme Court.— Cox v. State of New

Hampshire, 312 U. S. 569, 61 S. Ct. 762, 85 L. Ed. 1049.

The New Hampshire Supreme Court, as is pointed out

in Judge Johnson’s dissenting opinion, was called upon to

determine the constitutionality of a state statute prohibit

ing, among other things, a parade or procession on the

streets without a permit from local authorities. The New

Hampshire statute did not set out a standard for granting

or refusing the permit. The language of the New Hamp

shire court answering the assertion that the statute under

consideration vested unwarranted control in the licensing

authorities is quoted in Judge Johnson’s opinion and will

not be repeated here.

In the New Hampshire case, the marchers were divided

into four or five groups, each composed of about fifteen

to twenty persons. Each group proceeded to a different

part of the business district of the City of Manchester and

then lined up in a single-file formation and marched along

sidewalks of the city in such a formation. The marchers

carried banners and distributed leaflets announcing a

7a

meeting to be held at a later time where a talk on govern

ment would be given to tbe public free of charge. The

marchers had no permit. Despite the fact that the marchers

were carrying banners and distributing leaflets as well as

marching, their conviction of parading without a permit

was affirmed by the Supreme Court of New Hampshire.—

State v. Cox, supra.

In affirming the judgment of the Supreme Court of New

Hampshire, the Supreme Court of the United States in

Cox v. New Hampshire, supra, said in part as follows:

“ The sole charge against appellants was that they

were ‘ taking part in a parade or procession’ on public

streets without a permit as the statute required. They

were not prosecuted for distributing leaflets, or for

conveying information by placards or otherwise, or

for issuing invitations to a public meeting, or for hold

ing a public meeting, or for maintaining or express

ing religious beliefs. Their right to do any one of

these things apart from engaging in a ‘parade or pro

cession’ upon a public street is not here involved and

the question of the validity of an ordinance addressed

to any other sort of conduct than that complained of

is not before us.

“There appears to be no ground for challenging the

ruling of the state court that appellants were in fact

engaged in a parade or procession upon the public

streets. As the state court observed: ‘It was a march

in formation, and its advertising and informatory pur

pose did not make it otherwise. . . . It is immaterial

that its tactics were few and simple. It is enough that

it proceeded in an ordered and close file as a collective

body of persons on the city streets.’

# # # * #

“ If a municipality has authority to control the use

of its public streets for parades or processions, as it

undoubtedly has, it cannot be denied authority to give

consideration, without unfair discrimination, to time,

place and manner in relation to the other proper uses

of the streets. We find it impossible to say that the

limited authority conferred by the licensing provisions

of the statute in question as thus construed by the

state court contravened any constitutional right” (312

U. S., 573-576).

We would like to point out that we do not construe §1159

as conferring upon the “ commission” of the City of Bir

mingham the right to refuse an application for a permit

to carry on a parade, procession or other public demonstra

tion solely on the ground that such activities might tend

to provoke disorderly conduct. See Edwards v. South Caro

lina, 372 U. S. 229, 83 S. Ct. 680, 9 L. Ed. 2d 697.

We also hold that under §1159 the Commission is with

out authority to act in an arbitrary manner or with un

fettered discretion in regard to the issuance of permits. Its

discretion must be exercised with uniformity of method

of treatment upon the facts of each application, free from

improper or inappropriate considerations and from unfair

discrimination. A systematic, consistent and just order of

treatment -with reference to the convenience of public use

of the streets and sidewalks must be followed. Applica

tions for permits to parade must be granted if, after an

investigation it is found that the convenience of the public

in the use of the streets or sidewalks would not thereby

be unduly disturbed.

Since the Court of Appeals of Alabama rendered its deci

sion and judgment in the case here under review, the Su-

9a

preme Court of the United States rendered a decision in a

case wherein §1159 was involved. See Wyatt Tee Walker

v. City of Birmingham, decided by the Supreme Court of

the United States on June 12, 1967, 388 U. S. 307, 87 S. Ct.

1824,------ L. Ed. 2 d ------- . Application for rehearing was

denied on October 9, 1967. The Walker case, supra, was in

the Supreme Court of the United States on writ of cer

tiorari to review the opinion and judgment of this court

in the case of Walker et al. v. City of Birmingham, 279 Ala.

53, 181 So. 2d 493, wherein we affirmed the conviction of

Walker and several others, including Shuttlesworth, of

criminal contempt for violating a temporary injunction

issued by the Circuit Court of Jefferson County, in Equity,

which enjoined Walker, Shuttlesworth and others from en

gaging in, sponsoring, inciting or encouraging mass street

parades or mass processions or mass demonstrations with

out a permit. The injunction enjoined the respondents

from carrying on other activities which we do not think

necessary to comment on here. In our case of Walker et al.

v. City of Birmingham, 279 Ala. 53, 181 So. 2d 493, we did

not expressly pass on the constitutionality of §1159, al

though the petitioners, that is, Walker, Shuttlesworth and

others, asserted that said §1159 is void because it violates

the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution

of the United States. Based on that premise, the said peti

tioners also argued that the temporary injunction was void

as a prior restraint on the constitutionally protected rights

of freedom of speech and of assembly.

Our affirmance of the criminal contempt convictions was

based on the principle “ that the circuit court had the duty

and authority, in the first instance, to determine the va

lidity of the ordinance, and, until the decision of the circuit

court is reversed for error by orderly review, either by the

10a

circuit court or a higher court, the orders of the circuit

court based ou its decision are to be respected and dis

obedience of them is contempt of its lawful authority, to

be punished. Howat v. State of Kansas, 258 TJ. S. 181, 42

S. Ct. 297, 66 L. Ed. 550.”

As we have heretofore indicated, the Supreme Court of

the United States on June 12, 1967, affirmed our judgment

in Walker et al. v. City of Birmingham,, 279 Ala. 53, 181

So. 2d 483. The Supreme Court of the United States di

vided five to four. It appears from the Court’s opinion,

written by Mr. Justice Stewart, and from, the opinions of

the dissenting Justices, that the petitioners in the Supreme

Court of the United States again asserted that §1159 was

void on its face. The dissenting Justices expressed the

view that §1159 is unconstitutional on its face.

However, the majority of the Court, as then constituted,

did not hold that §1159 is void on its face. The Court’s

opinion contains the following language:

“ The generality of the language contained in the

Birmingham parade ordinance ['§1159] upon which

the injunction was based would unquestionably raise

substantial constitutional issues concerning some of

its provisions. Schneider v. State, 308 U. S. 147, 60

iS. Ct. 146, 84 L. Ed. 155; Saia v. People of State of

New York, 334 U. S. 558, 68 S. Ct. 1148, 92 L. Ed.

1574; Kunz v. People of State of New York, 34 U. S.

290, 71 S. Ct. 312, 95 L. Ed. 280. The petitioners, how

ever, did not even attempt to apply to the Alabama

courts for an authoritative construction of the ordi

nance. Had they done so, those courts might have given

the licensing authority granted in the ordinance a nar

row and precise scope, as did the New Hampshire

Courts in Cox v. New Hampshire [312 U. S. 579, 71

11a

S. Ct. 762, 85 L. Ed. 1049] and Ponlos v. New Hamp

shire [345 U. S. 395, 73 S. Ct. 760, 97 L. Ed. 1105],

both supra. € f. Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham,

382 U. S. 87, 91, 86 S. Ct. 211, 213, 15 L. Ed. 2d 176;

City of Darlington v. Stanley, 239 S. Ct. 139, 122 S. E.

2d 207. Here, just as in Cox and Poulos, it could not

be assumed that the ordinance was void on its face.”

(Emphasis supplied) (87 S. Ct., 1830)

The language which we have just italicized seems to us

to be in direct conflict with the conclusion reached in the

majority opinion of the Court of Appeals of Alabama here

under review.

We are of the opinion that the construction which Judge

Johnson placed on §1159 in his dissenting opinion, which

we have in effect adopted, together with the construction

which we have placed on §1159 in this opinion, requires a

reversal of the judgment of the Court of Appeals here

under review.-—Cox v. New Hampshire, 312 U. S. 569, 61

S. Ct, 762, 85 L. Ed. 1049; Walker et al. v. City of Birming

ham, 388 U. S. 307, 87 S. Ct. 1824, — L. Ed. 2 d ------ .

We hold that §1159 is not void on its face and that under

the construction which we have placed on that section, it

did not deprive Shuttlesworth of any right guaranteed to

him under the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the

Constitution of the United States.

We are also in accord with the conclusion reached by

Judge Johnson in his dissenting opinion to the effect that

there is nothing in the record before us tending to show

that §1159 has been applied in other than a fair and non-

diseriminatory fashion. The record before us shows no

violation of Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356, 6 S. Ct.

1064, 30 L. Ed. 220.

12a

The petitioners in the case of Wyatt Tee Walker et al.

v. City of Birmingham, 388 U. S. 307, 87 S. Ct. 1824,------

L. Ed 2d ------ , decided by the Supreme Court of the

United States on June 12, 1967, asserted that they were

free to disobey the injunction because §1159, on which the

injunction was based, had been administered in an arbi

trary and discriminatory fashion. In support of that con

tention those petitioners had sought to introduce evidence

in the trial court to the effect that a few days before the

injunction issued requests for permits to picket had been

made to a member of the" City Commission and one request

had been rudely refused and that this same official had

later made it clear that he was without power to grant the

permit alone, since the issuance of permits was the re

sponsibility of the entire Commission. The Supreme Court

of the United States, in answering that contention, said as

follows: “Assuming the truth of the proffered evidence,

it does not follow that the parade ordinance is void on its

face.”

We see no occasion to deal at length with the holding or

observation contained in the majority opinion of the Court

of Appeals of Alabama to the effect that the evidence was

insufficient to show that Shuttlesworth had engaged in a

parade on the “ streets or other public ways of the City of

Birmingham without a permit.” The evidence as delineated

in the dissenting opinion of Judge Johnson, in our opinion,

clearly shows that such a violation occurred.

We can see no merit in the position apparently taken in

the majority opinion of the Court of Appeals of Alabama

to the effect that since the marchers paraded on the side

walks of the City of Birmingham rather than in the streets,

there had been no violation of said §1159.

Section 2 of the General City Code of Birmingham of

1944 reads in part:

13a

“ Sec. 2. Definitions and rules of construction.

“ In the construction of this code and of all ordi

nances, the following definitions and rules shall be ob

served, unless the context clearly requires otherwise.

* * * * *

“ Sidewalk: The term ‘sidewalk’ shall mean that por

tion of a street between the curb line and adjacent

property line.”

It is appropriate to note that the statute under con

sideration in the case of State v. Cox, 91 N. H. 137, 16 Atl.

2d 508, prohibited a parade or procession on streets with

out a permit from local authorities. The parade or pro

cession in which Cox was involved occurred on the side

walks of the city of Manchester. Neither the Supreme

Court of New Hampshire nor the Supreme Court of the

United States took the position that the statute involved

did not apply to sidewalks as well as to the portion of the

street generally used by vehicular traffic. Cox’s conviction

of parading without a permit was upheld by the courts.

We are aware of the fact that ordinances somewhat simi

lar to §1159 have been declared unconstitutional in two

recent federal cases. See Gayat v. Pierce (U. iS. Court of

Appeals, 5th Circuit), 372 F. 2d 658; Baker et al. v. Binder,

decided in the United States District Court for the West

ern District of Kentucky at Louisville. That was a three-

judge court, with one judge dissenting. No reference was

made in the opinions delivered in those cases to Walker

et al. v. City of Birmingham, 388 U. S. 307, 87 S. 'Ct. 1S24,

■------ L. Ed. 2d ------ . Perhaps we have placed too much

reliance on Walker et al. v. City of Birmingham, 388 U. S.

307, 87 S. Ct. 1824, —— L. Ed. 2d ------ , and on Cox v.

14a

New Hampshire, 312 U. S. 569, 61 S. Ct. 762, 85 L. Ed.

1049. We may have misinterpreted the opinions in these

cases. If so, we will no doubt be set straight.

In view of the foregoing, the judgment of the Court of

Appeals is reversed and the cause is remanded to that

court.

R eversed and R emanded.

Livingston, C. J., Goodwyn, Merrill, Coleman and Har

wood, JJ., concur.

15a

Judgment of the Supreme Court of Alabama

THE SUPREME COURT OF ALABAM A

T h e S tate of A labam a— J udicial D epartm ent

O ctober T erm 1967-68

November 9, 1967

6th Div. 291

C /A 6th Div. 979

Ex parte: City of Birmingham,

a Municipal Corporation

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO COURT OF APPEALS

(Re: Fred L. Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham)

W hereas, on January 20, 1966, the Writ of Certiorari

to the Court of Appeals was granted, and said cause was

set down for submission on briefs or oral argument;

WHEREUPON,

Comes the petitioner, by its attorney, and the Petition

for Writ of Certiorari to the Court of Appeals being sub

mitted on briefs and duly examined and understood by the

Court, it is considered that in the record and proceedings

of the Court of Appeals there is manifest error.

16a

I t is therefore ordered and adjudged that the judgment

of the Court of Appeals be reversed and annulled and the

cause remanded to said Court for further proceedings

therein.

I t is furth er ordered and adjudged that the costs inci

dent to this proceeding be taxed against the respondent,

Fred L. Shuttlesworth, for which costs let execution issue.

17a

Opinion of the Court of Appeals of Alabama

THE ALABAM A COURT OF APPEALS

T he S tate o f A labama— J udicial D epartment

O ctober T erm , 1965-66

November 2, 1965

6 Div. 979

F red L. S hu ttlesw orth

v.

Cit y op B irm in g h am

APPEAL PROM JEFFERSON CIRCUIT COURT

Cates, Judge:

This appeal was submitted February 27, 1964, and was

originally assigned to J ohnson , J.

Shuttlesworth was convicted by a jury in a circuit court

trial de novo. The City charged him with a breach of its

ordinance against parading without a permit. §1159, Gen

eral City Code of 1944.1

1 “It shall be unlawful to organize or hold, or to assist in organiz

ing or holding, or to take part or participate in, any parade or

procession or other public demonstration on the streets or other

public ways of the city, unless a permit therefor has been secured

from the commission.

“ To secure such permit, written application shall be made to the

commission, setting forth the probable number of persons, vehicles

and animals which will be engaged in such parade, procession or

18a

Pursuant to verdict, the trial judge adjudicated him

guilty, fined him $75.00 and costs, and also sentenced him

to ninety days hard labor for the City.

There are three questions for decision: (1) whether

§1159, supra, denies, on its face, due process of law; (2)

whether or not the ordinance as applied violates Yick Wo

v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356; and (3) the sufficiency of the

evidence.

I.

Pacts

About two o’clock, P. M., Good Friday, April 12, 1963,

some fifty-two persons issued from a church on Sixth Ave

nue, North, in Birmingham. They went easterly on the

sidewalk of Sixth Avenue crossing Fifteenth and Sixteenth

Streets. At Seventeenth Street they turned south, then

at Fifth Avenue east again.

The defendant was one of the first to emerge from the

church. Various city policemen saw him thereafter, some

times walking along with and sometimes alongside the

others, once bounding from front to rear.