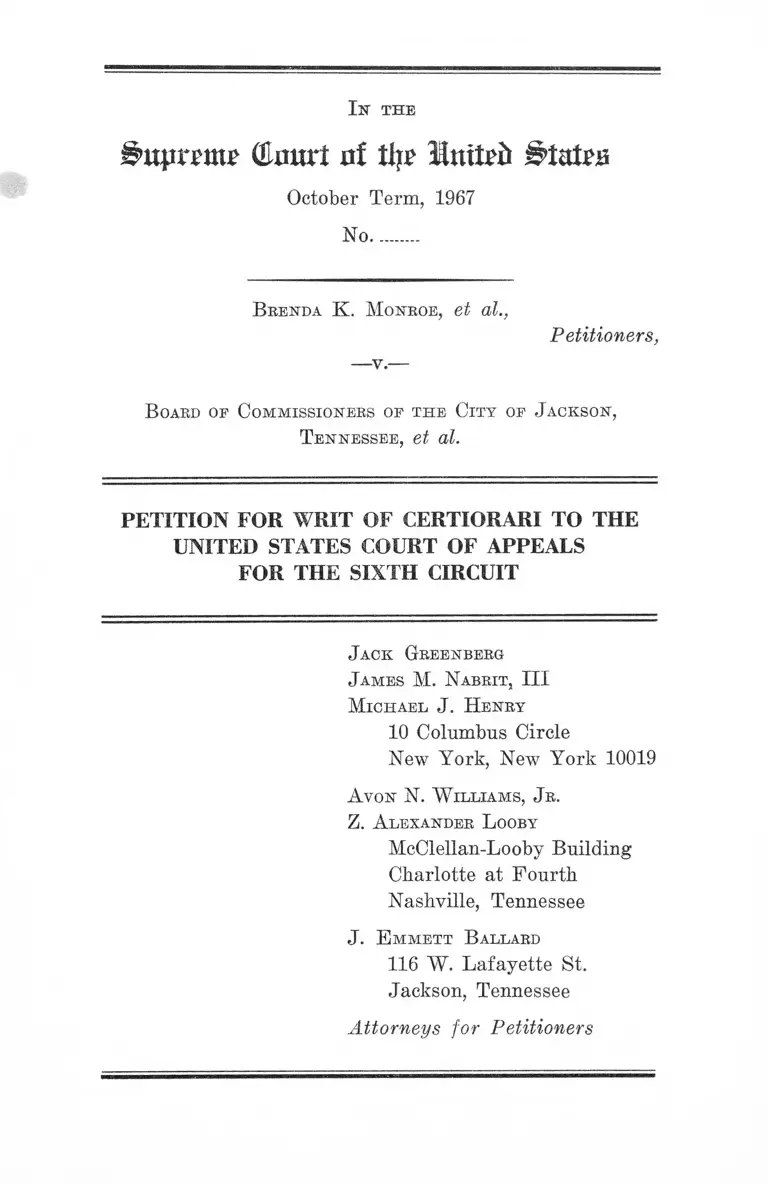

Monroe v. City of Jackson, TN Board of Commissioners Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Monroe v. City of Jackson, TN Board of Commissioners Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, 1967. e8b1c717-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/23ae7ab6-2c6e-42c6-b46c-ef30928238a3/monroe-v-city-of-jackson-tn-board-of-commissioners-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-sixth-circuit. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

Ihtpran? (Enuri at tljT Initpi*

October Term, 1967

No.........

1st th e

Brenda K . Monroe, et al.,

Petitioners,

—v.—

B oard of Commissioners of the City of Jackson,

Tennessee, et al.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Michael J. Henry

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A von N. W illiams, J r.

Z. A lexander L ooby

McClellan-Looby Building

Charlotte at Fourth

Nashville, Tennessee

J. E mmett B allard

116 W. Lafayette St.

Jackson, Tennessee

Attorneys for Petitioners

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Citations to Opinions Below ........................................... 1

Jurisdiction ..................... 2

Question Presented ............................................................ 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved ..... 2

Statement .............................................................................. 2

The Jackson City School System and General

Policies Perpetuating Segregation ......................... 5

The Racial Basis of the Board’s Junior High

School Attendance Policies and the Educational

Expert Panel’s Proposed Non-Racial Plan ........... 8

The Expert Panel’s Analysis of Why the City of

Jackson’s Schools Will Remain Segregated Un

less its Policies are Changed to Disestablish Seg

regation ...................................................................... 13

R easons fob Granting the W rit—

I. Introduction— The Importance of the C ase....... 15

II. The Sixth Circuit Applied an Erroneous Stan

dard in Deciding this Case, Which is Incon

sistent with Decisions of this C ourt.................... 19

III. The Sixth Circuit’s Decision Conflicts with Re

cent Major Decision of the Fifth, Eighth, and

Tenth Circuits on the Question of Whether a

Previously Segregated School System Must

Undertake Affirmative Action to Disestablish

Segregation ............................................................ 24

PAGE

Conclusion

11

A ppendix page

Memorandum Opinion of the United States District

Court for the Western District of Tennessee (filed

July 30, 1965) .................................................................. lb

Order of the United States District Court for the

Western District of Tennessee (filed August 11,

1965) .................................................................................. 26b

Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for the

Sixth Circuit (filed July 21, 1967) ............................... 33b

Order of the United States Court of Appeals for the

Sixth Circuit (filed July 21, 1967) ............................... 46b

Table op Cases

Bell v. School City of Gary, Ind., 324 F.2d 209 (7th

Cir. 1963), cert. den. 377 U.S. 924 ...............................25, 26

Board of Education of Oklahoma City Public Schools

v. Dowell, 375 F.2d 158, cert. den. 387 U.S. 931____28, 29,

30,31

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond, 382

U.S. 103 (1965) .............................................................. 4

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954); 349

U.S. 294 (1955) ........... 4,15,16,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) ...............................22,23

Charles C. Green v. County School Board of New Kent

Co., Va., Supreme Court No. 695, October Term 1967 15

Goss v. Board of Education of City of Knoxville, Tenn.,

373 U.S. 683 (1963).......................................................... 7,21

I l l

Kelley v. Altheimer, Arkansas Public School District

No. 22, 378 F.2d 483 (8th Cir. 1967) ...........................27, 28

Kelley v. Board of Education of City of Nashville,

Tenn., 270 F.2d 209 (6th Cir. 1959), cert. den. 361

U.S. 924 .......................................................................... 20,21

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965) ........... 23

Mapp v. Board of Education of City of Chattanooga,

Tenn., 373 F.2d 75 (1967) .............................................. 21

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896) ......................... 20

Kaney v. The Board of Education of the Gould School

District (8th Cir., No. 18,527, August 9, 1967) ........... 28

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964) ........................... 24

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965) ................................ 4, 23

Schine Chain Theatres v. United States, 334 U.S. 110

(1948) ................................................................................ 23

United States v. Bausch & Lomb Optical Co., 321 U.S.

707 (1943) .......................................................................... 23

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education,

et al., 372 F.2d 836 (5th Cir. 1966), re-affirmed

en banc, 380 F.2d 385 (5th Cir. 1967) ...................5,16, 24,

25, 26, 27

United States v. National Lead Co., 332 U.S. 319 (1947) 23

United States v. Standard Oil Co., 221 U.S. 1 (1910) .... 23

Statute

PAGE

42 U.S.C. § 1983 2

IV

Other A uthorities

PAGE

Southern School Desegregation, 1966-67, a Report of

the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, July, 1967 ....... 16

Desegregation Report, Fall 1966, of Tennessee’s Public

Elementary and Secondary Schools, a Report of the

State of Tennessee, Department of Education, Equal

Educational Opportunities Program ...........................16,17

In t h e

(llimrt nf tfye luitrd States

October Term, 1967

No.........

B renda K. Monroe, et al.,

Petitioners,

— v .—

B oard of Commissioners of the City of J ackson,

T ennessee, et al.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Sixth Circuit entered in the above-entitled case on

July 21, 1967.

Citations to Opinions Below

The district court’s opinion is reported at 244 F. Supp.

353, and is reprinted in the Appendix hereto, infra, pp. lb-

32b. The opinion of the Court of Appeals is unreported and

is printed in the Appendix hereto, infra, pp. 33b-46b. An

earlier district court opinion in this case is reported at 221

F. Supp. 968.

2

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered

July 21, 1967. The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked

under 28 U.S.C. Section 1254 (1).

Question Presented

Whether the courts below should have required the school

board to adopt a desegregation plan which would abolish

the dual school system and eliminate the identifiable Negro

school.

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

This case involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States, and 42 U.S.C.

Section 1983 providing a right of relief in equity for vio

lations of constitutional rights.

Statement1

This class action was filed January 8, 1963 by Negro

students against the Board of Commissioners of the City

of Jackson, Tennessee, which administers the city school

system. The original complaint, asserting rights secured

by the Fourteenth Amendment, sought injunctive relief

against the continued operation of a compulsory segre

gated school system, and an order requiring the city to 1

1 The page citations in this Statement are to the original page numbers

in Volumes I-IV of the typed transcript o f testimony at the district court

hearings of May 28 and June 18, 1965, which have been filed as part of

the certified original record by the Clerk of the Court of Appeals for the

Sixth Circuit.

3

present a plan for reorganization into a unitary non-

racial system. In due course, the Board of Commissioners

came forward with a proposed plan of gradual desegrega

tion which was modified as to timetable and approved

by the district court. See 221 F. Supp. 968 (W.D. Tenn.,

1963).

After the elementary school desegregation plan had

operated for two years, and proposed desegregated junior

high school zones had been announced, plaintiffs filed a

Motion for Further Belief (9/4/64), Specification of Ob

jections to Junior High School Zones (11/30/64), and an

Additional Motion for Further Belief (4/19/65), alleging

generally that the Board’s zoning, transfer, and faculty

assignment policies were designed to perpetuate segrega

tion to the maximum extent possible. The district court

held hearing on these motions and objections on May 28,

1965 and June 18, 1965. The Superintendent of Schools

testified and plaintiffs presented expert testimony of three

educational administrators, Dr. Boger W. Bardwell, Super

intendent of Schools of Elk Grove Township, Illinois;

Merle G. Herman, Assistant Superintendent of Schools of

Villa Park, Illinois; and Dr. Eugene Weinstein, Professor

of Sociology, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee.2

2 Dr. Bardwell’s qualifications included B.S., M.S., and Ph.D. degrees

from the University of Wisconsin in public school administration, fifteen

years’ experience in school administration generally, and substantial ex

perience in school building planning and zoning. The Elk Grove school

district o f which he had been superintendent for five years was of approx

imately the same size as the Jackson city school system (T. 136-138). Mr.

Herman’s educational qualifications included a B.A. from McKendree Col

lege, and an M.A. and completion of most doctoral requirements at Wash

ington University in St. Louis. His experience included three years’

public school teaching, seven years’ public school administration, and ten

years college teaching in the field of education. During the period in

which he was a university faculty member, he participated in many school

surveys in a number of different states, including zoning problems as

part of those surveys. The school system of which he was Assistant Super

4

The district court decided that racial gerrymandering

was so obvious in the case of some elementary zones that

it was required to order some alterations. However, the

court ruled that gerrymandering was not obvious enough

to allow relief in the case of junior high school zones,

in spite of substantial expert testimony to the contrary.

The experts had concluded that a school system which in

tended to desegregate rather than preserve the maximum

amount of segregation, would, in accord with standard edu

cational practice, have adopted an entirely different zoning

system for junior high schools. The district court, in addi

tion to holding that the Board of Commissioners had no

affirmative obligation to re-organize its school system to

disestablish segregation of students, held that the board

had no obligation to re-assign faculty members to elim

inate faculty segregation. See 244 F. Supp. 353 (W.D.

Tenn. 1965), Appendix infra, pp. lb-25b.

On appeal the United States Court of Appeals for the

Sixth Circuit held that while the district court had erred

with regard to faculty segregation, citing Bradley v.

School Board of the City of Richmond, Va., 382 U.S. 103

(1965), and Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965), it had

not erred with regard to students. The Sixth Circuit re

affirmed its traditional view of the nature of the consti

tutional obligation of desegregation that “we read Brown

as prohibiting only enforced segregation” , and expressly

disagreed with and declined to follow the contrary view

intendent was also of approximately the same size as the Jackon city

school system (T. 196-197). Dr. Weinstein’s qualifications included a B.A.

from the University of Chicago, an M.A. from Indiana University, and a

Ph.D. from Northwestern University, all in the areas of sociology and

social psychology. His particular field of specialization was child devel

opment, and he had conducted studies of the impact of school desegrega

tion on the development and educational attitudes of children and their

parents (T. 299-301).

5

adopted by the United States Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit in United States et al. v. Jefferson County

Board of Education et al., 372 F.2d 836 (5th Cir., 1966),

re-affirmed en banc, 380 F.2d 385 (5th Cir., 1967). See

Appendix, infra, pp. 33b-45b. Plaintiffs seek to have re

viewed on certiorari the specific ruling on gerrymandering

of junior high school zones in the Jackson city school sys

tem, which was based on the general legal premise of lack

of an affirmative obligation to disestablish segregation of

students.

The Jackson City School System and General Policies

Perpetuating Segregation

Jackson, Tennessee is a small to medium sized city in

mid-western Tennessee, with a school system of approxi

mately 8,000 students, about 40% Negro and 60% white.

The system has eight elementary schools, three junior

high schools, and two high schools (PL Ex. 26). Up until

the school year 1961-62, eight of the thirteen schools

(5 elementary, 2 junior high, and 1 high school) were

exclusively for whites, and the remaining five (3 elemen

tary, 1 junior high, and 1 high school) were designated

for Negroes ((PI. Ex. 26), 221 F. Supp. 968).

At least as early as 1956, leaders of the Jackson Negro

community began petitioning the Board of Commissioners

to implement this Court’s 1954 decision requiring public

school desegregation (T. 371-372). They met with total

failure for at least five years until the beginning of the

1961-62 school year. Then, pursuant to the Tennessee

Pupil Placement Act, the board began accepting individual

applications for enrollment of Negro children in white

schools. During 1961-62, three Negro students were ad

mitted to white schools under this act, and in the following

year (1962-63), four more, for a total of seven (T. 371-372).

6

In early 1963, this lawsuit was filed. In June, 1963, the

district court granted plaintiffs’ motion for summary judg

ment, and ordered the Board of Commissioners to file a

plan of desegregation. After proposing a gradual time

table for desegregation grade by grade starting from the

lowest grade up, which was modified and then approved

by the district court (221 F. Supp. 968), the board began

implementation of its alleged plan of desegregation in the

elementary schools in 1963.

A new set of zones for the elementary schools was an

nounced which was supposed to be unitary, non-racial,

and drawn according to the accepted educational standards

of compactness and capacity of buildings. Nevertheless,

there were certain departures from these standards. The

district court held after the 1965 hearing that racial gerry

mandering was so obvious in the ease of the boundaries

between the white West Jackson and Negro South Jackson

Schools, the white Parkview and Negro Washington-

Douglass Schools, and the white Alexander and Negro

Lincoln Schools that the boundaries had to be re-drawn

Appendix, pp. 13b-14b.

Plaintiffs’ educational expert Dr. Bardwell testified that

in addition to these situations which the district court cor

rected, the boundaries between other white and Negro

zones were drawn to place Negro children living closer

to white schools in the Negro zones (T. 152). After inspec

tion of a map of all elementary zones superimposed on a

racial residential census of the city, Dr. Bardwell concluded

that the zones “ follow in many areas the racial complex of

the neighborhood, rather than the geography of the situa

tion,” and if geography were the main criterion, seven of

the eight elementary schools “would be integrated to a

much greater degree than they are” (T. 153-155).

7

Having achieved the maximum possible perpetuation of

segregation through school zoning, the defendant school

system then adopted a transfer policy to make it possible

for students who were unavoidably zoned to a school where

their race would be in the minority, to transfer to a school

where their race would be in the majority (App. 7b-8b).

While the original plan of desegregation approved by the

district court in 1963 provided that any transfer policy

could be adopted as long as it did not have as its purpose

the delay of desegregation, the district court found in 1965

that the school system had administered its ostensibly

open transfer policy in the following manner: “ They have

allowed white pupils as a matter of course to attend schools,

outside of their unitary zones, in which white pupils pre

dominate, and have allowed Negro pupils as a matter of

course to attend schools, outside of their unitary zones,

attended only by Negroes but they have denied Negroes

(and specifically intervening plaintiffs) the right to attend

predominantly white schools outside of their unitary zones”

(T. 346-347, App. 8b). In other words, the Board was using

the “minority to majority” transfer policy which had been

condemned by this Court in 1963 in Goss v. Board of Edu

cation, 373 U.S. 683 (1963), App. 8b.3

After the Board of Commissioners began its plan of os

tensible desegregation in 1963, it continued its previous

3 Other aspects o f the system’s transfer policy were also administered

in accordance with the principle of a segregated dual school system. Plain

tiffs’ educational expert Mr. Herman testified that the Jackson city school

system admitted approximately 400 students from surrounding Madison

County (out of approximately 8,000 total students in the city system),

and all white students were assigned to schools which were all or

predominantly white and all Negro students to schools which were all-

Negro, without exception (T. 210-211). Mr. Herman also suggested that

county transferees of the same race as the predominant race in any par

ticular school were apparently given priority in assignment over students

of a minority race who actually resided in the zone of that school (T. 211).

8

practice of assigning Negro teachers only to schools whose

enrollments had been and remained all-Negro, and white

teachers only to the schools which had been previously all-

white and remained predominantly white under the deseg

regation plan in operation (T. 294). As late as the 1964-65

school year, the Board was asserting as the basis of this

policy that “ the integration of the faculty is not related

to nor necessary for the achievement of elimination of com

pulsory segregation” (53a) and that “ the destruction of

the entire City School System is seeded in this request

[for faculty desegregation] in such fashion as to be beyond

the control of defendant officers, not from violence but

from student withdrawal” (42a).

The Racial Basis of the Board’s Junior High School

Attendance Policies and the Educational Expert Panel’s

Proposed Non-Racial Plan

The district court’s approval of the Board of Commis

sioners’ zoning plan for junior high schools, as affirmed by

the Court of Appeals, is specifically at issue here. Jackson

has three junior high schools: Tigrett, heretofore all-white,

is located in the western part of the city; Merry, hereto

fore and still all-Negro, in the center of the city; and

Jackson, heretofore all-white, in the eastern portion (PI.

Ex. 26, App. 14b).

All three junior high schools were constructed in the ten-

year period after 1955 during which the Board of Com

missioners was operating a segregated school system con

trary to this Court’s 1954 and 1955 pronouncements in the

Brown cases (T. 174). The two schools intended for whites

were located in the centers of white residential concentra

tion in the western and eastern sections of the city; the

single school intended for Negroes was located in the center

9

of the Negro residential concentration in the central sec

tion of the city (T. 201-205).

When the Board of Commissioners was finally forced to

announce a plan for the desegregation of the junior high

schools in late 1964 under the district court’s original 1963

order, it proposed a set of irregularly shaped zones in

which the center zone for previously all-Negro Merry

Junior High School was shaped roughly like an hour glass

(PL Ex. 19). In developing these zones, the Superintendent

of Schools apparently did not undertake to find out how

many junior high school students there were in the city

and attempt to match the numbers of students to the

capacities of the respective schools, in spite of affirming

that he used educational considerations such as capacity of

schools in formulating the zones (T. 38-135, 63-65).

After analysis of a racial residential map of the city

showing the locations of the residences, and the race, of all

students in the school system, plaintiffs’ educational expert

Merle G. Herman concluded with regard to the junior high

school zones: “ There seems to be a very distinct tendency

for the lines to follow the residences of Negroes and whites

—in other words, separating the two. Where there is a

large Negro population, there tend to be lines drawn to

maintain segregation in the schools that serve those areas”

(T. 201).

After the new junior high school zones were announced

for the following year in late 1964, and after the school

system had discovered from the 1964-65 enrollment figures

that all-Negro Merry Junior High School, which then ac

commodated all Negro junior high school students in the

city but one, was three pupils over capacity, the Board of

Commissioners decided in the spring of 1965 to construct

four additional classrooms at Merry so as to increase its

10

capacity by 120 (T. 35-36, 99-100). This decision was made

despite the facts that (1) the enrollments of the two pre

viously all-white junior high schools were approximately

300 students under capacity, and (2) the elementary school

enrollment figures indicated that total junior high enroll

ment for the system would remain constant at about 100

students above the present enrollment for at least the next

four years (T. 35-36, 215-216).

When asked whether based on his experience no white

children conld be expected to enroll in Merry Junior High

School and would it not therefore remain all-Negro, the

Superintendent of Schools said, “Judging on the basis of

what has happened up to now, that might be the case. . . .

I imagine it will be predominantly Negro” (T. 101-102). He

also expected that the small number of Negro students

from the other two zones of the heretofore all-white junior

high schools would continue coming to Merry, something

the Board’s transfer policy would encourage (T. 102). The

Superintendent attempted to justify the construction of

an addition to Merry Junior High by pointing out that

all-Negro Merry Senior High School (in the same build

ing), was growing and might need some of the rooms pres

ently used by the junior high school. But he also admitted

that the all-white senior high school (not yet then deseg

regated) was 249 students under capacity (T. 103).

In the course of the district court hearing on the pro

posed junior high zones, plaintiffs’ educational expert Mr.

Herman explained that the standard basis for drawing

junior high school zones was the “ feeder” principle. By this,

junior high school zones are based on elementary school

zones and are composed by clustering several such zones

so that all students from the same elementary school go on

to attend the same junior high school:

11

. . . , the main consideration is to follow ordinarily

the elementary school lines so that when elementary

schools are then taken and six graders graduating go

into junior high schools, then there is an integration

of effort between the elementary schools and the junior

high schools where orientation procedures might be

developed, that is where sixth graders might go into

junior high schools and get acquainted with it. The

principals are able to work together in enabling a suf

ficiently easy transition from the elementary to the

junior high school. Also from a guidance point of

view, it is well that the schools have some associations

that are teacher relationships and administrative re

lationships which should be developed between the

feeder schools and the schools into which the children

are being enrolled (T. 198-199).

He also explained that geography and compactness were

not so important in junior high zoning as in elementary

zoning, since junior high students are “ old and mature

enough to take care of themselves on the streets . . . and,

therefore, you don’t pay too much attention to the or

dinary barriers that you consider at the elementary school

level” (T. 199-200). The Superintendent of Schools ad

mitted the desirability of the “ feeder” principle in devel

oping junior high school zones (T. 104-105).

When asked whether the Board of Commissioners’ junior

high school zoning plan violated the “ feeder” principle,

plaintiffs’ educational expert Mr. Herman stated: “Yes,

it does, because the lines of the elementary schools are

not consistent with the lines which separate the zones of

the junior high schools” (T. 203). Mr. Herman concluded

that since “ it is an accepted fact here, I think, that white

children attend white schools and Negro children attend

12

Negro schools,” that even though a completely free trans

fer system was superimposed on the Board’s junior high

school zones based on race, “ segregation will continue to

exist” (T. 206).

As a further check on whether the Board of Commis

sioners’ proposed junior high school zones were drawn

with the primary goal of preserving the maximum amount

of segregation, rather than according to standard educa

tional practice, plaintiffs’ experts undertook to draw junior

high school zones for the city of Jackson, as they would

for their own school systems. They obtained all of the rele

vant data necessary for drawing such zones, such as de

tailed maps of the city, the locations of the elementary and

junior high schools, the locations of the residences of all

students, the capacities of schools, etc., both from the office

of Superintendent of Schools and by utilizing a research

assistant at Lane College in Jackson (T. 138-139, 142-145,

171-172, 187-190, 368-370).

The expert panel concluded that by using the accepted

“feeder” principle, all of the existing elementary schools

in the city were located so that compactly designed zones

around them could be conveniently clustered into three

zones for the three existing junior high schools in the fol

lowing manner: (1) Parkview (white), Washington-

Douglass (Negro), and Whitehall (white) Elementary

School zones would be the zone for Jackson Junior High

School; (2) Highland Park (white), West Jackson (white),

and South Jackson (Negro) Elementary School zones would

be the zone for Tigrett Junior High School; and (3)

Alexander (white) and Lincoln (Negro) Elementary School

zones would be the zone for Merry Junior High School

(T. 209). Each of these elementary schools is located con

veniently to its proposed feeder junior high school, and

13

the capacities of the elementary schools were matched to

their respective proposed feeder junior high schools (T.

209). The expert panel assumed that the then existing ele

mentary school zones drawn by the Board of Commissioners

would have to be altered to produce greater compactness

and reduce racial gerrymandering, as the district court

eventually required, in part (T. 208-209, App. 13b). The

panel concluded that by drawing the zones in accordance

with the “ feeder” principle, “ the junior high school zones

would be developed objectively, without regard to the

racial character of the neighborhood” and “ from an educa

tional point of view, it would be sound” (T. 209).

The Expert Panel’s Analysis of Why the City of Jackson’s

Schools Will Remain Segregated Unless its Policies are

Changed to Disestablish Segregation

All three of plaintiffs’ educational experts agreed that

the combined effects of the school system’s racial zoning

policy, segregated faculty assignments, and “minority to

majority” and other racially based transfer policies, had

preserved almost total segregation, and had in fact fostered

segregation after the schools had ostensibly been desegre

gated. Dr. Roger W. Bardwell pointed out that where

the Board had zoned all of the schools in such a way that

their enrollments were conspicuously either predominantly

white or almost all-Negro, and thus preserved the racial

identity of the schools as they were under the dual school

system, the availability of the transfer option caused the

racial identification of the schools to become even more

pronounced by permitting the remaining students of the

minority race in each school to transfer out (T. 159-161,183-

184). Dr. Bardwell indicated that where the school sys

tem had conferred racial identities on individual schools,

it would be expected that substantial numbers of students

14

would transfer out of those schools because they were

of the minority race and this was confirmed by the fact of

an abnormally large number of transfers within the sys

tem (T. 159-161, 183-184). Merle G. Herman stated that

the effect of a transfer system predicated on race super

imposed on zones predicated on race would operate “ to

maintain whatever the attitude structure is of the people

who have children in those schools” and where the attitude

toward integration was obviously unfavorable because of

the large number of minority to majority transfers, “ this

would totalize segregation” (T. 200-202). Dr. Eugene Wein

stein pointed out the cumulative effects of faculty segre

gation on the racially gerrymandered zoning and minority

to majority transfer policies: “First, especially in con

junction with a transfer plan, it tends to continue to stig

matize Negro schools or schools that were formerly Negro'

schools as Negro, and to make schools which were newly

desegregated still be regarded as white schools as part

of the generalized conception of the schools themselves”

(T. 302). He concluded that “ faculty segregation tends to

make additional impetus to transfer out of a Negro school,

because it is obvious that it is Negro in all of its educa

tional environs and it tends to stigmatize a school as a

Negro school” (T. 315). Dr. Bardwell and Mr. Herman both

concurred in Dr. Weinstein’s conclusion (T. 160, 201).

15

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I.

Introduction— The Importance of the Case.

This case raises a fundamental issue concerning the

implementation by the lower federal courts of this Court’s

decision in Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483;

349 U.S. 294, requiring desegregation of the public schools

where there has been compulsory legal segregation. The

issue is whether a city school system which utilizes all the

discretion available in locating buildings, and determining-

attendance zoning and student transfer policies, to per

petuate and increase racial segregation in the period fol

lowing the Brown decisions, should be held to have met its

obligations to desegregate simply because it has also

permitted a small number of Negro students to attend

previously all-white schools.

The City of Jackson’s combination zoning and transfer

plan is one of the two common types of desegregation!

plans utilized in the South, especially in city school sys

tems. The other is the “freedom of choice” type plan.

See petition now pending in Green v. County School Board

of New Kent Co., Virginia, No. 695, October Term 1967.

Both types of desegregation plan achieve the common result

of keeping previously all-Negro schools all-Negro; the

only integration which occurs comes from a small propor

tion of Negro students attending predominantly white

schools.

Although the proportion of Negroes in all-Negro schools

has declined since the 1954 decision of this Court in Brown,

more Negro children are now attending such schools than

16

in 1954.4 Indeed, during the 1966-67 school year, a full

12 years after Brown, more than 90% of the almost 3

million Negro pupils in the 11 Southern states still at

tended schools which were over 95% Negro and 83.1%

were in schools which were 100% Negro.5 And, in the case

before the Court, over 85% of the Negro pupils in the sys

tem still attend schools with only Negroes.6 Thus, “ this

June, the vast majority of Negro children in the South

who entered the first grade in 1955, the year after the

Brown decision, were graduated from high school without

ever attending a single class with a single white student.” 7

And, as the Fifth Circuit has had occasion to say, “ for

all but a handful of Negro members of the High School

Class of 1966, this right [to a racially non-discriminatory

public school system] has been of such stuff as dreams are

made on.” 8 It is clear then, that the desegregation process

ordered by the first Brown decision has met with unfore

seen obstacles, and that further consideration of the prob

lem of remedy originally considered in the second Brown

decision is in order.

The issue of this case of a systematic evasion of the con

stitutional obligation to desegregate is raised more partic

ularly by a fact situation in which a board of education

(1) maintained a completely compulsorily segregated sys

4 Southern School Desegregation, 1966-67, a Report of the U.S. Com

mission on Civil Rights, July, 1967 at p. 11.

5 Id. at 165.

6 State of Tennessee, Department of Education, Equal Educational Op

portunities Program, Fall 1966 Desegregation Report on Tennessee’s Pub

lic Elementary and Secondary Schools (compiled from reports to the U.S.

Office of Education).

7 Southern School Desegregation, 1966-67, at p. 147.

8 United States et al. v. Jefferson County Board of Education, et al., 372

F.2d 836, 845 (5th Cir., 1966) re-affirmed en banc, 380 F.2d 385 (5th

Cir., 1967).

17

tem after Brown until this lawsuit was filed in 1963,

(2)undertook the constructon of three compulsorily segre

gated junior high schools during the period after Brown

which were located in the centers of racially segregated

residential concentrations of the city, (3) at the start of

the junior high desegregation plan in 1965 zoned those

schools in such a way as to follow the patterns of racial

residential segregation to the maximum extent possible,

(4) provided a transfer provision by which students of

the minority race (white or Negro) who were unavoidably

zoned to a school in which they would be in a racial minor-,

ity were encouraged to transfer to a school in which they

would be in a racial majority, and (5) upon determining

that the single all-Negro junior high school was not of

sufficient capacity to accommodate all the Negro junior

high students in the city undertook to construct additional

capacity at that school while there was still substantial

excess capacity at the two all-white junior high schools.

The result has been and remains that the previously

all-Negro junior high school remains an all-Negro junioi;

high school, and that there is a very small proportion of

Negro students attending the previously all-white and still

overwhelmingly white junior high schools. (The three

previously all-Negro elementary schools and the previously

all-Negro senior high school—not directly in issue in this

petition—also remain all-Negro under the same policies).9

There is a natural reluctance on the part of an appellate

court to consider the details of administration of a school

system and the complexities of desegregation in any partic

ular district. For this reason, perhaps, this Court has

considered few school cases since 1954, and those all in one

form or another raised the question of the survival of the

9 Tennessee Fall 1966 Desegregation Deport, supra.

18

desegregation process itself. Now tliat the pattern of

resistance has shifted decidedly from absolute defiance to

evasion, the urgent question is whether a board may adopt

a course which perpetuates segregation for the overwhelm

ing majority of Negro students, while paying lip service

to the obligation to desegregate. This question of necessity

requires consideration of the details of a particular sys

tem’s operation, for only in this manner can the principle

of school desegregation become the practice of disestab

lishment of segregation.

This case provides an especially appropriate vehicle

to consider the general problem of evasion of the obliga

tion to desegregate. The record presents a comprehensive

analysis of the issues by a panel of educational admin

istrators who served as expert witnesses. In particular,

the panel conducted an extensive survey of the zoning

problem in the Jackson school system just as they would

have if they were drawing zones for their own systems.

They then proceeded to actually design a model zoning

plan for the Jackson junior high schools based on standard

and accepted educational principles. The fact that this

zoning plan would completely integrate the three junior

high schools in Jackson is the most convincing possible

support for their general conclusion that the zones actually

devised by the Jackson school system were designed to

preserve the maximum possible degree of segregation

rather than according to the asserted non-racial educa

tional considerations.

19

II.

The Sixth Circuit Applied an Erroneous Standard in

Deciding this Case, Which is Inconsistent with Decisions

of this Court.

When confronted with the facts of this case of the racially

oriented process by which the school board created the

junior high zones and the end result of almost completely

segregated junior high schools, the Sixth Circuit in its

opinion under a heading entitled “ Compulsory Integration”

stated that petitioners were apparently asking them to

require school authorities to take “ affirmative” steps to

eradicate the existing pattern of racial segregation in the

schools. While indicating that they recognized that they

were in fact dealing with Tennessee schools which had been

legally and compulsorily segregated prior to Brown and

to which the Brown decisions perforce applied, the Sixth

Circuit held:

We are not persuaded, however, that we should devise

a mathematical rule that will impose a different and

more stringent duty upon states which, prior to Brown,

maintained a de jure biracial school system, than upon

those in which the racial imbalance in its schools has

come about from so-called de facto segregation. Ap

pendix, infra, p. 35b.

In spite of petitioners claim that the City of Jackson’s

school system had not yet been desegregated according to

the requirements of the first Brown decision, and that they

were therefore invoking the equitable obligation of the

second Brown decision to desegregate, the Sixth Circuit

suggested that petitioners were really seeking to impose

a “Bill of Attainder” ( !) on the State of Tennessee:

20

To apply a disparate rule because these early systems

[segregated systems] are now forbidden by Brown

would be in the nature of imposing a judicial Bill of

Attainder. Such proscriptions are forbidden to the

legislatures and the states of the nation—U.S. Const.

Art. I, Section 9, Clause 3 and Section 10, Clause 1.

Appendix, infra, pp. 36b-37b.

By its reference to the fact that biracial school systems

“were once found lawful in Plessy v, Ferguson, 163 U.S.

537 (1896), and such was the law for 58 years thereafter,”

Appendix, infra, p. 36b, the Sixth Circuit indicated rather

clearly that it regards the patterns, practices, and traditions

which were evolved by those biracial school systems as still

having substantial legitimacy, and, in effect, that Plessy v.

Ferguson remains influential in construing the extent of the

obligation to desegregate enunciated by the second Brown

decision.

The Sixth Circuit held that “ We read Brown as prohibit

ing only enforced segregation,” and that no relief was

justified since it was now theoretically possible for individ

ual Negro students to attend previously all-white schools

in Jackson. Appendix, infra, p. 35b. It thus re-affirmed its

limited view of the constitutional obligation of desegrega

tion earlier enunciated in Kelley v. Board of Education of

the City of Nashville, Tenn., 270 F.2d 209 (6th Cir., 1959),

cert. den. 361 U.S. 924 and adhered to consistently since that

time:

It [the Supreme Court] has not decided that the federal

courts are to take over or regulate the public schools

of the states. It has not decided that the states must

mix persons of different races in the schools . . . The

Constitution, in other words, does not require integra

tion. It merely forbids discrimination. 270 F.2d at 226.

21

Based on this view, the Sixth Circuit had held in Kelley

that a “minority to majority” transfer policy which per

mitted any child zoned to a school in which his race was in

the minority to obtain a transfer to a school in which his

race was in the majority, was not in violation of the Four

teenth Amendment since “there is no evidene before ns that

the transfer plan is an evasive scheme for segregation.”

270 F.2d at 229. But see Goss v. Board of Education of the

City of Knoxville, Tenn., 373 TJ.S. 683 (1963) which repudi

ated Kelley and, we submit, the legal philosophy on which

it rested—which persists in this case. See also Mapp v.

Board of Education of the City of Chattanooga, Tennessee,

373 F.2d 75 (6th Cir. 1967).

There is nothing in this Court’s decisions on school de

segregation which supports the Sixth Circuit’s view on the

facts of this case that the constitutional obligation of the

Fourteenth Amendment is satisfied by allowing a few

Negro students to attend formerly all-white schools, while

all of the building location, zoning, and transfer policies of

the school system are manipulated in such a way as to keep

as many Negro students as possible in all-Negro schools.

There is also nothing in this Court’s decisions on school

desegregation which supports the Sixth Circuit’s view of

the legal standard set by the second Brown decision as in

volving no affirmative obligation to re-organize the biracial

school system to eliminate the practice of segregation.

This Court held from the beginning that the constitu

tional ban on segregation in public education required far

reaching affirmative action in completely re-organizing the

entire school system to eliminate the practice. In the second

Brown decision, 349 U.S. 294 (1955), it said:

At stake is the personal interest of plaintiff's in ad

mission to public schools as soon as practicable on a

22

nondiscriminatory basis. To effectuate this interest

may call for elimination of a variety of obstacles in

making the transition to school systems operated in

accordance with the constitutional principles set forth

in our May 17, 1954, decision. 349 U.S. at 300.

This Court indicated the nature of the obstacles to be

overcome in the second Brown decision by its direction

to the courts supervising the re-organization of the school

systems to “consider problems related to administration,

arising from the physical condition of the school plant,

the school transportation system, personnel, revision of

school districts and attendance areas into compact units

to achieve a system of determining admission to the public

schools on a nonracial basis, and revision of local laws

and regulations which may be necessary in solving the

foregoing problems.” 349 U.S. at 300-301. This direction,

combined with the “ deliberate speed” proviso, indicates

that a thorough and complete re-organization of the segre

gated school systems was envisioned.

In Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958), this Court stated

that the Brown decisions imposed an affirmative obligation

on school officials of segregated dual school systems to dis

establish segregation:

State authorities were thus duty bomid to devote every

effort toward initiating desegregation and bringing

about the elimination of racial discrimination in the

public school system. 358 U.S. at 7.

Although Cooper itself was a case of clear and direct

defiance by state officials, this Court looked forward to

a time when attempts to perpetuate segregation in public

education might become more subtle, when it said that

the constitutional rights involved “can neither be nullified

openly and directly by state legislators or state executive

or judicial officers, nor nullified indirectly by them through

evasive schemes for segregation whether attempted ‘in

geniously or ingenuously.’ ” 358 U.S. at 17.

Recently, in Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965), this

Court re-affirmed the completeness of the reorganization

of the segregated school systems suggested by the enu

meration of factors in the second Brown decision. It indi

cated that the provision of transfers for Negro students

who so desired to schools with more extensive curricula

from which they had been excluded, was something sub

stantially less than it envisioned as an adequate general

plan of desegregation.

In the second Brown decision, this Court directed that

“ in fashioning and effectuating the decrees, the courts will

be guided by equitable principles.” 349 U.S. at 300. The

general equity principle is that there is no wrong without

a remedy, and therefore equity courts have broad power

to provide relief and are obligated to do so. The test of

the propriety of measures adopted by such courts is

whether the required remedial action reasonably tends to

dissipate the effects of the the condemned actions and to

prevent their continuance. Louisiana v. United States, 380

U.S. 145 (1965). An example of the application of this

equitable principle is in the antitrust area, where it has

been held to require the complete dissolution of large na

tional business enterprises, when there was no other way

to counteract the previous effects of illegal monopoliza

tion. United States v. Standard Oil Co., 221 U.S. 1 (1910);

United States v. Bausch & Lomb Optical Co., 321 U.S. 707

(1943); United States v. National Lead Co., 332 U.S. 319

(1947); Schine Chain Theatres v. United States, 334 U.S.

110 (1948). Similarly, it has been held to require that fed

24

eral courts conduct the redrawing of state legislative dis

tricts when there was no other way to counteract the effects

of population disparities in existing state legislative dis

tricts. Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964). The Sixth

Circuit has clearly not recognized its obligations as a court

of equity in supervising the district courts as directed by

Brown II to fashion a complete remedy for the unconstitu

tional operation of a compulsory segregated school system,

since by no conceivable standard can the effects of the con

demned action of establishing a pattern and practice of

segregation be said to have been rooted out from the Jack-

son city school system.

III.

The Sixth Circuit’s Decision Conflicts with Recent

Major Decisions of the Fifth, Eighth, and Tenth Circuits

on the Question of Whether a Previously Segregated

School System Must Undertake Affirmative Action to

Disestablish Segregation.

While it may be contended that school desegregation

cases are all unique because they involve the issue of the

extent of equitable relief justified by the facts of the par

ticular case, nevertheless there are general similarities.

The Sixth Circuit recognized this and expressly stated that

its view was in conflict with the rule recently expressed by

the Fifth Circuit on the issue of the extent of the obliga

tion of a previously legally segregated school system to act

affirmatively to disestablish that segregation:

We are asked to follow United States v. Jefferson

County Board of Education, 372 F.2d 836 (5th Cir.,

1966), which seems to hold that pre-Broivn biracial

states must obey a different rule than those which

desegregated earlier or never did segregate. This de

25

cision decrees a dramatic writ calling for mandatory

and immediate integration. In so doing, it distin

guished Bell v. School City of Gary, Indiana, 324 F.2d

209 (7th Cir., 1963), cert, den., 377 U.S. 924, on the

ground that no pre-Brown de jure segregation had

existed in the City of Gary, Indiana. . . .

. . . to the extent that United States v. Jefferson County

Board of Eucation, and the decisions reviewed therein,

are factually analogous and express a rule of law

contrary to our view herein and in Deal, we respect

fully decline to follow them. Appendix, infra, pp. 36b-

37b.

The Fifth Circuit holds contrary to the Sixth Circuit that

affirmative action— such as the rezoning plan offered by

petitioners’ experts here—must be taken to break up the

pattern and practice of segregation which had previously

been established: “ The two Brown decisions . . . compelled

seventeen states, which by law had segregated public

schools, to take affirmative action to reorganize their

schools into a unitary, nonracial system.” 372 F.2d at 847.

The Court wrote:

I f school officials in any district should find that their

district still has segregated faculties and schools or

only token integration, their affirmative duty to take

corrective action requires them to try an alternative

to a freedom of choice plan, such as a geographic at

tendance plan, a combination of the two, the Princeton

plan, or some other acceptable substitute, perhaps

aided by an educational park. 372 F.2d at 895-6.

With reference to the Sixth Circuit’s view that the legal

standard for the extent of the obligation to desegregate

is that the Constitution does not require integration, but

26

merely forbids compulsory segregation, the Fifth Circuit

says that “what is wrong about [this view] is that it drains

out of Brown that decision’s significance as a class action to

secure equal educational opportunities for Negroes by com

pelling the states to reorganize their public school systems.”

372 F.2d at 865. The court said:

Segregation is a group phenomenon. . . . Adequate

redress therefore calls for much more than allowing a

few Negro children to attend formerly white schools ;

it calls for liquidation of the state’s system of de jure

school segregation and the organized undoing of the

effects of past segregation. 372 F.2d at 866.

The Fifth Circuit contradicts the Sixth Circuit’s view

that segregation in the South is now just like segregation

in the rest of the country:

. . . the holding in Brown, unlike the holding in Bell but

like the holdings in this circuit, occurred within the

context of state-coerced segregation. The similarity of

pseudo de facto segregation in the South to actual de

facto segregation in the North is more apparent than

real. Here school boards, utilizing the dual zoning

system, assigned Negro teachers to Negro schools and

selected Negro neighborhoods as suitable areas in

which to locate Negro schools. Of course the concentra

tion of Negroes increased in the neighborhood of the

school. Cause and effect came together. In this circuit,

therefore, the location of Negro schools with Negro

faculties in Negro neighborhoods and white schools

in white neighborhoods cannot be described as an

unfortunate fortuity: It came into existence as state

action and continues to exist as racial gerrymandering,

made possible by the dual system. 372 F.2d at 876.

# # *

27

The central vice in a formerly de jure segregated

public school system is apartheid by dual zoning: in

the past by law, the use of one set of attendance

zones for {white children and another for Negro

children, and the compulsory initial assignment of a

Negro to the Negro school in his zone. Dual zoning

persists in the continuing operation of Negro schools

identified as Negro, historically and because the faculty

and students are Negroes. Acceptance of an indi

vidual’s application for transfer, therefore, may satisfy

that particular individual; it will not satisfy the class.

The class is all Negro children in a school district

attending, by definition, inherently unequal schools

and wearing the badge of slavery separation displays.

Relief to the class requires school boards to desegre

gate the school from which a transferee comes as

well as the school to which he goes. It requires con

version of the dual zones into a single system. Facul

ties, facilities, and activities as well as student bodies

must be integrated. 372 F.2d at 867-868.

Moreover, the Sixth Circuit’s decision necessarily con

flicts with the recent decision of the Court of Appeals for

the Eighth Circuit in Kelley v. The Altheimer, Arkansas

Public School District No. 22, 378 F.2d 483 (8th Cir., 1967),

which specifically rejected the interpretation of the Four

teenth Amendment adhered to by the Sixth Circuit that

“ the Constitution, in other words, does not require inte

gration. It merely forbids discrimination.” 378 F.2d 488.

The Eighth Circuit held that there is an affirmative obliga

to disestablish segregation:

We have made it clear that a Board of Education

does not satisfy its constitutional obligation to deseg

regate by simply opening the doors of a formerly

all-white school to Negroes. 378 F.2d at 488.

It added that this meant that the board of education must

take affirmative steps to change the identities of all-Negro

schools into integrated schools, as well as allowing in

dividual Negro students to transfer to formerly all-white

schools:

The appellee School District will not be fully deseg

regated nor the appellants assured of their rights

under the Constitution so long as the Martin School

clearly remains identifiable as a Negro school. The

requirements of the Fourteenth Amendment are not

satisfied by having one segregated and one desegre

gated school in a District. We are aware that it will

be difficult to desegregate the Martin School. How

ever, while the difficulties are perhaps largely tradi

tional in nature, the Board of Education has taken

no steps since Brown to attempt to change its identity

from a racial to a non-racial school 378 F.2d at 490.10

Finally, the Sixth Circuit’s decision conflicts squarely

with that of the Tenth Circuit in Board of Education of

Oklahoma City Public Schools v. Doivell et al., 375 F.2d 158

(10th Cir., 1967), cert. den. 387 TT.S. 931. The factual pat

tern of this City of Jackson case is virtually identical to

that with which the Tenth Circuit was confronted in the

Oklahoma City case. The one difference was that the

Oklahoma City public schools were somewhat further along

10 A subsequent decision of the Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit,

Raney et al. v. The Board of Education of the Gould School District, 8th

Cir., No. 18,527, August 9, 1967, appears to conflict with Kelley v.

Altheimer since the facts o f the two cases were very similar. However,

there was little discussion of general legal principles of school desegrega

tion in Raney, since the Court held that a general attack on the adequacy

of the desegregation plan had not been properly made in the district

court. Raney also seemed to leave open the possibility of eventually re

quiring a complete re-organization of the school system to disestablish

segregation, but at some indefinite time in the future.

29

in the desegregation process than the City of Jackson. The

Oklahoma City school system had announced a formal de

segregation plan in 1955, whereas the City of Jackson

schools did not take even this initial step until 1961. After

zoning its schools in such a way as to preserve the maxi

mum possible segregation without explicit dual zones

through following the patterns of racial residential segre

gation, the Oklahoma City school system then instituted a

“minority to majority” transfer plan by which students

who were unavoidably zoned to schools where they would

be in a racial minority were encouraged to transfer to

schools where they would be in a racial majority. Thus,

virtually all of the schools in Oklahoma City which had

been designated as “white” or “ Negro” schools under segre

gation, remained identified as “white” or “Negro” schools

because the student bodies were almost or entirely all-white

or all-Negro. The City of Jackson school system did like

wise. The Oklahoma City school system continued to as

sign all-Negro faculties to schools which were all or pre

dominantly Negro in student body, and all-white faculties

to schools which were all or predominantly white in student

body, thereby reinforcing the identifications of various

schools as being intended for Negroes or whites rather than

just for students. The City of Jackson school system acted

similarly. The Oklahoma City school system located new'

schools constructed after 1955 in the centers of homoge

neous racial residential concentrations, so as to facilitate

the perpetuation of segregation through the use of zoning,

transfer, and faculty assignment policies. The City of

Jackson school system did the same. At the time of the

final district court order of relief in the Oklahoma City case

in 1965, about 80% of the Negro students in the system still

attended schools which were all-Negro or over ninety-five

percent Negro in student body. During the last school year

(1966-67) in the City of Jackson, over 85% of the Negro

30

students in the system still attended schools which were

one-hundred percent Negro in student body.11

Based on these facts, the Tenth Circuit in the Oklahoma

City case approved a district court finding that “ the school

children and personnel have in the main from all of the

evidence been completely segregated as much as possible

under the circumstances rather than integrated as much as

possible.” 375 F.2d at 161, fn. 2. The Tenth Circuit stated

that “ inherent in all of the points raised and argued here

by [the school board] is the contention that at the time of

the filing of this case [1961] there was no racial discrimina

tion in the operation of the school system.” 375 F.2d at 164.

It responded that this fact situation did constitute a case

of legal segregation which had not been disestablished, in

spite of the facts that zone lines had been redrawn to elimi

nate obvious duality in 1955, and that there were some

Negro students attending previously all-white schools:

As we have pointed out, complete and compelled

segregation and racial discrimination existed in the

Oklahoma City School system at the time the Brown

decision became the law of the land. It then became

the duty of every school board and school official “to

make a prompt and reasonable start toward full com

pliance” with the first Brown case. It is true the board,

in 1955, issued the policy statement and implemented

it by the drawing of school attendance lines and in

augurated a “minority to majority” pupil transfer

plan. The attendance line boundaries, as pointed out

by the trial judge, had the effect in some instances of

locking the Negro pupils into totally segregated schools.

In other attendance districts which were not totally

segregated the operation of the transfer plan naturally 11

11 Tennessee Fall 1966 Desegregation Report, supra.

31

led to a higher percentage of segregation in those

schools. 375 F.2d at 165.

The Tenth Circuit then held in Oklahoma City that

“ under the factual situation here we have no hesitancy in

sustaining the trial court’s authority to compel the board to

take specific action in compliance with the decree of the

court so long as such compelled action can be said to be

necessary for the elimination of the unconstitutional evils

pointed out in the court’s decree.” 375 F.2d at 166. In

cluded in the action required to eliminate the effects of

previous unconstitutional segregation was an order pairing

six-year secondary schools so that three grades of each

school were consolidated in one school and three grades

in the other school, thereby completely integrating each

school in the pair. This clearly required a school board

to take affirmative action to disestablish the pattern and

practice of segregation preserved through the use of a

zoning plan; it necessarily is in conflict with the Sixth

Circuit’s decision in this City of Jackson case which labels

such affirmative action as “compulsory integration” and a

“ judicial Bill of Attainder.” Judge Lewis concurring in

the Oklahoma City case explained the Tenth Circuit’s view

that since compulsion was used to maintain the system of

segregation, the compulsion inherent in school assignment

policies may properly be used to disestablish segregation:

I have no quarrel with the statement that forced

integration when viewed as an end in itself is not

a compulsion of the Fourteenth Amendment. But any

claimed right to disassociation in the public schools

must fail and fall. I f desegregation of the races is to

be accomplished in the public schools, forced asso

ciation must result, not as the end sought but as the

path to elimination of discrimination. And, to me,

32

the argument that racial discrimination cannot be elim

inated through factors of judicial consideration that

are based upon race itself is completely self-denying.

The problem arose through consideration of race;

it may now be approached through similar but en

lightened consideration.

The correctness of the Sixth Circuit’s differing standard

for reviewing desegregation plans merits the attention of

this Court.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons it is respectfully submitted

that the petition for certiorari should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Michael J. H enry

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A von N. W illiams, Jr.

Z. A lexander L ooby

McClellan-Looby Building-

Charlotte at Fourth

Nashville, Tennessee

J. E mmett B allard

116 W. Lafayette St.

Jackson, Tennessee

Attorneys for Petitioners

A P P E N D I X

APPENDIX

Memorandum Decision of the United States District

Court for the Western District of Tennessee

(filed July 30, 1965)

[Caption Omitted]

Plaintiffs have filed motions for additional relief, which

raise these issues:

1. Whether the assignment and transfer plan and poli

cies as actually carried out by the defendants violate

plaintiffs’ constitutional rights, and if so, to what extent

must the plan or policies be amended;

2. Whether the amended unitary zones for elementary

schools and the proposed unitary zones for junior high

schools are gerrymandered to maximize segregation and

thereby violate plaintiffs’ constitutional rights;

3. Whether the plan for gradual desegregation hereto

fore approved by the court, viewed as of now, meets the

constitutional standard of “ all deliberate speed” ;

4. Whether plaintiffs are entitled, under the Constitu

tion, to an order requiring the desegregation of faculty,

administrative and supporting personnel, and faculty in-

service training programs;

5. Whether plaintiffs are entitled, under the Constitu

tion, to an order prohibiting segregation in curricular and

extra-curricular activities;

6. Whether plaintiffs are entitled to recover attorneys

fees incurred in connection with these motions.

We will dispose of these issues in the order in which

they are set out above.

2b

At the outset it should be noted, as we have indicated,

that plaintiffs are asserting Fourteenth Amendment rights

alone, and are asserting no rights under any Act of

Congress.

In dealing with the multifarious issues that may be

presented in school desegregation cases, there frequently

is difficulty in deciding a particular issue even if the

applicable principle of law has been fairly well crystalized.

This is especially true in this field because, even though

so crystalized, an applicable principle is of necessity a

general principle which must be applied to myriad factual

situations. More difficulty is encountered, however, when

an underlying general principle has not yet become clear.

An example of this is the lack of complete clarity as to

whether the Constitution requires only an abolition of

compulsory segregation based on race or requires some

thing more. This general question must first be answered

before we can deal with the assignment and transfer issue

and the gerrymandering issue.

This court has heretofore considered the question as to

whether the Constitution requires only an abolition of

compulsory segregation based on race. Vick, et al. v.

Board of Education of Obion County, Tennessee, 205 F.

Supp. 436 (W.D. Tenn. 1962); Monroe, et al. v. City of

Jackson, Tennessee, 221 F.Supp. 963 (W.D. Tenn. 1963);

and Monroe, et al. v. Madison County, Tennessee, 229 F.

Supp. 580, (W.D. Tenn. 1964). The latter two opinions

were rendered at earlier stages of the separate proceed

ings in this action. We concluded in these opinions that

abolition of segregatio nbased on race is all that the Con

stitution requires. We based this conclusion not only on

our interpretation of the second Brown opinion (349 U.S.

294 (1954)) and Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958), but

also on the now famous specific statement to that effect

Memorandum Decision

3b

in Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F.Supp. 776 (E.D. S.G. 1955),

which was a per curiam opinion by three-judge court

presided over by Judge Parker of the Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit. However, plaintiffs again earnestly

contend that the Constitution requires an integrated ed

ucation, and so we have taken this occasion again to

review the law.

We find that the following opinions, among others, cite

and approve the statement in Briggs v. Elliott, supra,

to the effect that the Constitution requires only an aboli

tion of compulsory segregation based on race: Kelley v.

Boar dof Education of Nashville, 270 F.2d 209, 226 (6th

Cir. 1959) ; Bell et al. v. School City of Cary, 324 F.2d

209, 213 (7th Cir. 1963); Griffin v. Board of Supervisors

of Prince Edward County, 322 F.2d 332, 336 (4th Cir.

1963); Dillard v. School Board of City of Charlottesville,

308 F.2d 920, dissent at p. 926, (4th Cir. 1962); Boson v.

Rippy, 285 F.2d 43, 48 (5th Cir. 1960); Avery v. Wichita

Falls Independent School Dist., 261 F.2d 230, 233 (5th

Cir. 1957); Armstrong v. Board of Education of Birming

ham, 323 F.2d 333, dissent at p. 346 (5th Cir. 1963);

Taylor v. Board of Education of New Rochelle, 294 F.2d

36, dissent at p. 47 (2nd Cir. 1961). It is interesting to

note that the Fifth Circuit in a very recent case (Single-

ton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dist., —— F.2d

------ , decided June 22, 1965), recognizing that it had more

than once approved the statement in Briggs, said that it

now “ should be laid to rest” and that “ . . . the second

Brown opinion clearly imposes on public school authori

ties the duty to provide an integrated school system.”

There is other authority in support of the view now

taken by the Fifth Circuit, but the clear weight of au

thority in the Courts of Appeal and District Courts sup

Memorandum Decision

4b

ports the view taken in Briggs and, as stated, our Court of

Appeals in the Kelley case, supra, seems to subscribe to

the Briggs view.

This question as to what the Constitution requires

comes into sharper focus in two different contexts: one

is a situation in which “honestly” arrived at unitary zones

result in de facto school segregation because of existing

racial housing patterns; the other is a situation in which

a voluntary assignment and transfer provision, not based

on race, results in the continuance of segregation. In

Northcross et al. v. Board of Education of Memphis, 333

F.2d 661 (6th Cir. 1964) our Court of Appeals recognized

that there is no constitutional obligation to draw zone

lines to maximize integration. See also, to the same effect,

Downs et al. v. Board of Education of Kansas City, 336

F.2d 988 (10th Cir. 1964), cert, denied 380 IT.S. 914 (1965)1

The Supreme Court has not dealt specifically with the first

situation, but it has done so with the second. In Goss, et al.

v. Board of Education of City of Knoxville, 373 U.S. 683

(1963), the Supreme Court struck down transfer provi

sions which allowed pupils who, under the rezoning, would

be required to attend a school in which they would be in

a racial minority to transfer to a school in which they

would be in a racial majority. In so doing, the Court said

at pp. 686-687:

“It is readily apparent that the transfer system pro

posed lends itself to tperpetuation of segregation.

Indeed, the provisions can work only toward that end.

While transfers are available to those who choose to

attend school where their race is in the majority,

there is no provision whereby a student might transfer

upon request to a school in which his race is in a

Memorandum Decision

5b

minority, unless he qualifies for a ‘good cause’ trans

fer. As the Superintendent of Davidson County’s

schools agreed, the effect of the racial transfer plan

was ‘to erpmit a child [or his parents] to choose

segregation outside of his zone but not to choose

segregation outside of his zone.’ Here the right of

transfer, which operates solely on the basis of a racial

classification, is a one-way ticket leading to but one

destination, i.e., the majority race of the transferee

and continued segregation. This Court has decided

that state-imposed separation in public schools is in

herently unequal and results in discrimination in vio

lation of the Fourteenth Amendment. Brown v. Board

of Education, 347 U.S. 483, 98 L.ed 873, 74 S. Ct.

686, 38 ALB 2d 1180 (1954). Our task then is to de

cide whether there transfer provisions are likewise

unconstitutional. In doing so, we note that if the

transfe rprovision were made available to all students

regardless of their race and regardless as well of the

racial composition of the school to which he requested

transfer we would have an entirely different case.

Pupils could then at their option (or that of their

parents) choose, entirely free of any imposed racial

considerations, to remain in the school of their zone

or to transfer to another.

“ Classification based on race for purposes of transfers

between public schools, as here, violate the Equal

Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.”

And the Court further said at pp. 688-689:

“The alleged equality—which we view as only super

ficial— of enabling each race to transfer from a de

Memorandum Decision

6b

segregated to a segregated school does not save the

plans. Liwe arguments were made without success in

Brown, 347 U.S. 483, 98 L.ed. 873, 74 S.Ct. 686, 38

ALB 2d 1180, supra, in support of the separate but

equal educational program. Not only is race the factor

upon which the transfer plans operate, but also the

plans lack a provision whereby a student might with

equal facility transfer from a segregated to a desegre

gated school. The obvious one-way operation of these

two factors in combination underscores the purely

racial character and purpose of the transfer provisions.

We hold that the transfer plans promote discrimina

tion and are therefore invalid.

“This is not to say that appropriate transfer provi

sions, upon the parents’ request, consistent with sound

school administration and not based upon any state-

imposed racial conditions, would fall. Likewise, we

would have a different case here if the transfer

provisions were unrestricted, allowing transfers to or

from any school regardless of the race of the majority

therein. But no official transfer plan or provision of

which racial segregation is the inevitable consequence

may stand under the Fourteenth Amendment.”

It appears that the Court held that these transfer provi

sions could not stand for two separate reasons: first, on

their face they contained an invalid racial classification,

and second, they could operate only to perpetuate segrega

tion. However, the Court expressly recognized that a