Rodgers v Teitelbaum Writ of Mandamus and/or Writ of Prohibition

Public Court Documents

July 19, 1974

77 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Rodgers v Teitelbaum Writ of Mandamus and/or Writ of Prohibition, 1974. 2b1d7cdb-c29a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/261a7074-ff28-4cce-8e17-291e7b2bdb97/rodgers-v-teitelbaum-writ-of-mandamus-andor-writ-of-prohibition. Accessed March 14, 2026.

Copied!

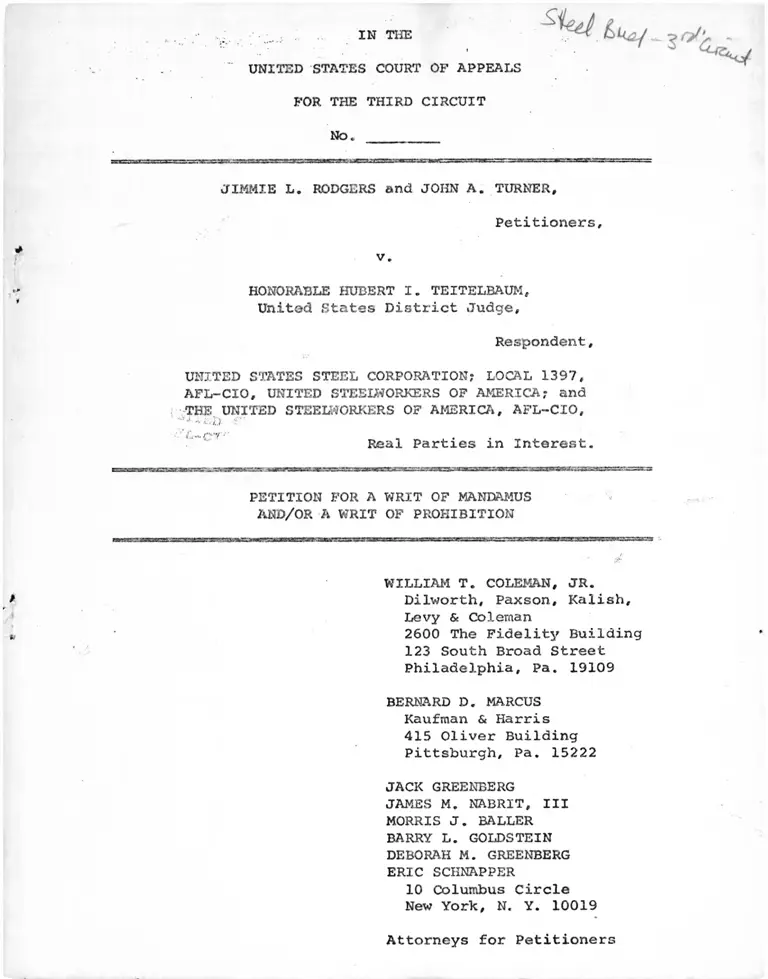

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OP’ APPEALS

FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT

No „

JIMIE L. RODGERS and JOHN A. TURNER,

Petitioners,

v.

HONORABLE HUBERT I. TEITELBAUM,

United States District Judge,

Respondent,

UNITED STATES STEEL CORPORATION? LOCAL 1397,

AFL-CIO, UNITED STEELWORKERS OF AMERICA? and

THE UNITED STEELWORKERS OF AMERICA, AFL--CIO,

T r Real Parties xn Interest.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF MANDAMUS

AND/OR A WRIT OF PROHIBITION

WILLIAM T. COLEMAN, JR.

Dilworth, Paxson, Kalish,

Levy & Coleman

2600 The Fidelity Building

123 South Broad Street

Philadelphia, Pa. 19109

BERNARD D. MARCUS

Kaufman & Harris

415 Oliver Building

Pittsburgh, Pa. 15222

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

MORRIS J. BALLER

BARRY L. GOLDSTEIN

DEBORAH M. GREENBERG

ERIC SCKNAPPER

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

Attorneys for Petitioner

I N D E X

Statement of Facts ............... ....................... 4

Statement of Issues Presented and Relief Sought ......... 21

Reasons for Granting the Writ:

* Introduction ................................... . 24

> I. The Orders Forbidding Plaintiffs' Attorneys

from Meeting with the Homestead, Pennsylvania

Branch of the N.A.A.C.P. Are Unconstitutional . 26

II. Lccal Rule 34(d) Is Unconstitutional on Its

Face and as Applied in This Civil Rights

Case. .............................. 38

III. The Orders of the District Court Restricting

Communications with Individual Class Members

Are Unconstitutional.......................... 52

IV. The Order Staying All Proceedings Violates

Plaintiffs' Rights to Due Process and Their

Rights Under Title VII of the Civil Rights

■ Act of 1964............................... . 57

Conclusion ......................................... 71

*

Table of Cases** — ....—

Q Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Company, 39 L.Ed.2d 147 (1974) 66

Aptheker v. Secretary of State, 378 U.S. 500 (1964) ....... 39

X Bates v. Little Rock, 361 U.S. 516 (1960) ............... 53

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954) .................. 35

~v\ Bridges v. California, 314 U.S. 252 (1941) .............. 32

Brooklyn Savings Bank v. O'Neil, 324 U.S. 647 (1945) .... 66,67

Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen v. Virginia State Bar,

377 U.S. 1 (1964) ......................... 31,32,40,41,

42,45,54

Page

i

Cases (cont'd) Page

2 Chandler v. Fretag, 348 U.S. 3 (1954) .................... 54

Clark v. American Marine Corp., 320 F. Supp. 709

(E.D. La. 1970), aff'd 437 F.2d 959 (5th Cir. 1981) . 45

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 536 (1965) .................... 37

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 559 (1965) .................... 37

V Craig v. Harney, 331 U.S. 252 (1941) ..................... 32

^ DeBeers Consolidated Mines Ltd. v. United States,

325 U.S. 212 (1945) ................................ 25

DiCostanzo v. Chrysler Corp., 15 Fed. R. Serv.2d 1248

(E.D. Pa. 1972) .................................... 48

0 Eisen v. Carlisle and Jacquelin, 42 U.S.L. Week 4804

(May 28, 1974) ..................................... 70

7, Gibson v. Florida Legislative Investigating Committee,

372 U.S. 539 (1963) ................................ 53

^ — Halverson v. Convenient Food Mart, Inc., 458 F.2d 927

(7th Cir. 1972) .................................... 45

0 Hansberry v. Lee, 311 U.S. 32 (1940) .................... 57,60

Huff v. Cass Co., 485 F.2d 710 (5th Cir. 1973) .......... 44

In re Ades, 6 F. Supp. 467 (D. Md. 1934) ................. 44

J in re Sawyer, 360 U.S. 622 (1959) ........................ 32

J investment Properties International, Ltd. v. IOS, Ltd.,

459 F. 2d 705 (2nd Cir. 1972) ....................... 25

J international Products Corp. v. Koons, 325 F.2d 403

(2nd Cir. 1963) .................................... 25

Jenkins v. United Gas Corp., 400 F.2d 28 (5th Cir. 1968) . 45

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, 488 F.2d 714

(5th Cir. 1974) ................................... 43,45

J LaBuy v. Howes Leather Company, Inc., 352 U.S. 249 (1957) 25

)

ii

Lea v. Cone Mills, 438 F.2d 86 (4th Cir. 1971) .......... 43

Local 734 Bakery Drivers Pension Fund Trust v.

Continental Illinois Nat'l Bank and Trust Co.,

57 F.R.D. 1 (N.D. 111. 1972) .......................... 48

Malone v. North American Rockwell Corp., 457 F.2d 779

(9th Cir. 1972) 45

N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama ex rel. Flowers, 377 U.S. 288 (1964) 24

j N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama ex rel. Patterson, 357 U.S. 449

(1958) ............................................. 53

')'■ N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963) .. 6,13,28,30,33,38,39,

40,41,42,44,46,50,54

N.A.A.C.P. v. Patty, 159 F. Supp. 503 (E.D. Va. 1958) .... 44

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400

(1968) ............................................ 43,44

Niemotko v. Maryland. 340 U.S. 268 (1951) ............... 36

/ Organization for a Better Austin v. Keefe, 402 U.S. 415

(1971) .............................................. 27

V Pennekamp v. Florida, 328 U.S. 331 (1946) ............... 32

Petway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 411 F.2d 998

(5th Cir. 1969) ............................. *...... 53

^ Powell v. Alabama, 287 U.S. 45 (1932) ................... 54

/

Rapp v. Van Dusen, 350 F.2d 806 (3rd Cir. 1965)..........

Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791 (4th Cir.),

cert, denied, 404 U.S. 1006 (1971) ................. 43,45

V Sanders v. Russell, 401 F.2d 241 (5th Cir. 1968) ........ 25,45

Schaeffer v. San Diego Yellow Cabs, Inc., 462 F.2d 1002

(9th Cir. 1972) .................................... 43

/

J Schlagenhauf v. Holder, 379 U.S. 104 (1964) ............

Schulte v. Gangi, 328 U.S. 108 (1946) ................... 56

Cases (cont'd) P---3—

iii

^Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479 (1960) .................. 53

V/ Texaco, Inc. v. Borda, 383 F.2d 607 (3rd Cir. 1967) ..... 25

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U.S. 88 (1940) ................ 36

y United Mine Workers v. Illinois State Bar Association,

389 U.S. 217 (1967) ................................ 31,40

United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum Industries, Inc.,

C.A. No. 74-P-339, N.D. Ala......................... 10

United States v. Roble, 389 U.S. 258 (1967) ............. 38,45

/v/\ United States v. United States Steel Corporation,

371 F. Supp. 1045 (N.D. Ala. 1973) ................. 6,36

)(, United Transportation Union v. State Bar of Michigan,

401 U.S. 576 (1971) .......................... 31,32,39,44

v Will v. United States, 389 U.S. 90 (1967) ............... 25

0 Williamson v. Bethlehem Steel Co., 468 F„2d 1201

(2nd Cir. 1972) ................................. 57,60,63

Wood v. Georgia, 370 U.S. 375 (1962) ..................... 28,32

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886) ................. 36

Statutes and Rules

28 U.S.C. § 1292 (b) ...................................... 17

28 U.S.C. § 1651(a) ...................................... 1

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2 (Title VII of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964 as amended) ................................ 5

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-3 (a) .................................. 53

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5 (b) ..... 53

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5 (f) (4) ................................ 69

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(f)(5) ........................... 3,17,23,69

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5 (k) .................................. 7,44

Cases (cont'd) Page

~7

iv

Statutes and Rules (cont'd) Page

Fed. R. App. P., Rule 21 ................................. 1

Fed. R. Civ. P., Rule 23(b)(2) 5

Fed. R. Civ. P., Rule 23(c)(1) ......................... 5,23,70

Fed. R. Civ. P., Rule 23(d) .............................. 47

Local Rule 19B, S.D. Florida ............................ 48

Local Civil Rule 22, N.D. Illinois ...................... 48

Local Rule 20, D. Maryland .............................. 48

Local Rule 34(d), W.D. Pa......................... 2,3,21,38,45,

46,47,49,50

Local Rule 6, S.D. Texas ................................ 48,49

Local Rule C.R. 23(g), W.D. Washington .................. 48

Other Authorities

ABA COMM. ON PROFESSIONAL ETHICS, OPINIONS, No. 148 (1935) 43

ABA C0MI>1. ON PROFESSIONAL ETHICS, INFORMAL OPINIONS,

No. 786 (1964) ..................................... 44

ABA COMM. ON PROFESSIONAL ETHICS, INFORMAL OPINIONS,

No. 888 (1965) ..................................... 43

ABA COMM. ON PROFESSIONAL ETHICS, INFORMAL OPINIONS,

No. 992 (1967) ..................................... 43

D. C. BAR ASSN. COMM. ON LEGAL ETHICS AND GRIEVANCE,

REPORT (January 26, 1971) .......................... 44

Legislative History of the Equal Employment Opportunity

Act of 1972 (H.R. 1746, P.L. 92-261) (Govt. Printing

Office, 1972) ...................................... 53

Manual for Complex Litigation (1973), Suggested Local

Rule No. 7 (§ 1.41 "Preventing Potential Abuse of

Class Actions") ..................................... 48,50

Note, The First Amendment Overbreadth Doctrine, 83

Harv. L. Rev. 844 (1970) ........................... 39

v

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT

No.

JIMMIE L. RODGERS and JOHN A. TURNER,

Petitioners,

v.

HONORABLE HUBERT I. TEITELBAUM,

United States District Judge,

Respondent,

UNITED STATES STEEL CORPORATION; LOCAL 1397,

AFL-CIO, UNITED STEELWORKERS OF AMERICA; and

THE UNITED STEELWORKERS OF AMERICA, AFL-CIO,

Real Parties in Interest.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF MANDAMUS

AND/OR A WRIT OF PROHIBITION

Pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1651(a) and Fed. R. App. P. 21,

petitioners respectfully request that the Court issue its writ

of mandamus commanding the respondent, the Honorable Hubert I.

Teitelbaum, to vacate his several orders and the local rule of

court set forth below and, in addition, or, in the alternative,

it is respectfully requested that the Court prohibit the

respondent from enforcing those orders and the local rule of

court hereinafter listed:

1. An order (App. 189a) issued temporarily June 27, 1974,

and finalized by an order of July 19, 1974 (App. 259a), which

applies Local Rule 34(d) so as to forbid plaintiffs' attorney

Bernard D. Marcus and his associates from accepting an unsolicited

invitation to attend a meeting of the Homestead, Pennsylvania

Branch of the National Association for the Advancement

Colored People (N.A.A.C.P.) for the purpose of discussing racial

discrimination at the Homestead Works of the United States Steel

Corporation, including particularly the effect on said plant of

a nationwide employment discrimination consent decree entered in

a suit brought by the United States in the United States District

Court for the Northern District of Alabama. (The motion of

plaintiffs "to communicate with the NAACP" was stated by the

respondent to be "denied at this time without prejudice to

renewal of that motion at a time which would appear to be more

appropriate to me," but there was no elaboration of the consider

ations governing an "appropriate time" for such a meeting.)

2. Local Rule 34(d) of the United States District Court

for the Western District of Pennsylvania, which provides:

Rule 34. Class Actions.

In any case sought to be maintained as a

class action.

* * *

(d) No communication concerning such action

shall be made in any way by any of the parties

thereto, or by their counsel, with any potential

or actual class member, who is not a formal

2

party to the action, until such time as an

order may be entered by the Court approving

the communication.

3. An order (App. 82a-86a) issued September 29, 1973, and

reaffirmed by order of July 19, 1974 (App. 259a-260a), which

applies Local Rule 34(d) of the United States District Court

for the Western District of Pennsylvania so as to limit plain

tiffs and their attorneys from any communication with members

of the putative class who are not formal parties.

4. An order issued July 19, 1974 (App. 259a-265a), which

applies Local Rule 34(d) so as to forbid plaintiffs' attorneys

from communication with members of the class who on their own

initiative request an opportunity to consult with said attorneys,

unless each individual class member first submits an affidavit

about how they happened to contact counsel.

5. An order issued June 27, 1974 (App. 174a-175a, 188a),

forbidding plaintiffs from conducting any further discovery and

staying all proceedings, including a class action determination,

until at least January 15, 1975, notwithstanding that it is the

statutory duty of respondent "to assign the case for hearing at

the earliest practicable date and to cause the case to be in

every way expedited" (42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(f)(5)).

In order to facilitate presentation and disposition of the

matter, petitioners have filed a notice of appeal from the

orders of June 27, 1974, and July 19, 1974, in the district court,

3

and are filing in this Court, together with the present petition

for prerogative writs, the following motions:

(1) a motion for consolidation of the present

application for prerogative writs with the

appeal, and for consideration of the appli

cation for prerogative writs on the record

filed in the appeal;

(2) a motion for a stay of the challenged orders

and for pendente lite relief during consid

eration of the consolidated proceeding in

this Court, and/or for expedited hearing of

the consolidated proceeding.

The relevant papers in the district court, to which refer

ence is made in this petition are included in an appendix to

this petition filed herewith, and will be identified by

reference to page numbers in the appendix.

The grounds for the petition for writs of mandamus and/or

prohibition are as follows:

I. STATEMENT OF FACTS

1. On August 24, 1971, petitioners (who are plaintiffs

below) filed in the United States District Court for the Western

District of Pennsylvania a complaint for injunctive relief, back

pay and damages which was styled Rodgers and Turner v.._United

4

States Steel Corporation, et al. , Civil Action No. 71-793. The

amended complaint (App. 5a-15a) sought to remedy racial dis

crimination at the Homestead Works of the United States Steel

Corporation. Plaintiffs are black employees of the defendant

corporation and members of the defendant unions. The amended

complaint alleged extensive discriminatory employment practices

in violation of 42 U.S.C. 2000e-2 [Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, as amended]. The action was sought to be main-

♦

tained as a class action pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil

Procedure 23(b)(2) on behalf of a class of more than 1,200 black

workers employed at the Homestead facility during a specified

period of time on jobs represented by defendant local union.

Plaintiffs have sought by repeated motions and briefs to have a

class determination pursuant to Rule 23(c)(1) (App. 35a-41a, 46a-

66a, 97a-117a) but the district court has deferred decision of

the matters (App. 82a-86a, 174a-175a).

2. One of the attorneys for plaintiffs is Bernard D. Marcus

of the Pittsburgh firm of Kaufman & Harris. Associated with him

in the case are several attorneys employed by the N.A.A.C.P. Legal

Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. (the Legal Defense Fund), a

non-profit corporation engaged in furnishing legal assistance in

certain cases involving claims of racial discrimination. The

Legal Defense Fund, which is entirely separate and apart from

the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

5

has been approved(N.A.A.C.P.), but has similar aims and purposes,

by a New York court to function as a legal aid organization.

Since 1940, the Legal Defense Fund has furnished legal assistance

in civil rights matters in state and federal courts throughout

the nation, usually in conjunction with local counsel such as

Mr. Marcus and his firm in this matter. N.A.A.C.P. v. Button,

371 U.S. 415, 421, n. 5 (1963). Various Legal Defense Fund staff

attorneys (including Messrs. Goldstein and Bailer and

Mrs. Greenberg, involved in the present matter) have developed

expertise as counsel in cases involving employment discrimination.

Mr. Goldstein was plaintiffs' trial counsel in a similar matter

which resulted in injunctive relief and back pay awards for

black employees of the United States Steel Corporation facility

at Fairfield, Alabama. United States v. United States Steel

Corporation, 371 F. Supp. 1045 (N.D. Ala. 1973). Accordingly,

Mr. Goldstein has developed specific knowledge and expertise about

problems of racial discrimination in the steel industry and past

and present practices of the defendant company and unions.

3. In undertaking to represent the named plaintiffs,

plaintiffs' attorneys did not accept or expect any compensation

from them, nor do they expect to receive any compensation from

any additional named plaintiffs who may hereafter be added, or

from any member of the plaintiff class. Mr. Marcus and his firm

expect to be compensated in this matter only by such attorneys

6

fees as may eventually be awarded by the court. Any fees awarded

by the court on account of work done by the employees of the

Legal Defense Fund will be paid over to that non-profit corpora

tion and will not be paid to the individual staff lawyers whose

compensation is limited to annual salaries. Plaintiffs' entitle

ment to an award of counsel fees by the court would not in any

event be affected by the number of individuals who are named as

parties plaintiff since the fees are not paid by the clients but,

rather, they are taxed as costs to the defendant. See 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e-5 (k).

4. Plaintiffs' counsel have engaged in extensive and diffi

cult investigative efforts required to prepare and present a

comprehensive employment discrimination case against the defendant

company and unions. The investigation has included extensive

discovery efforts, including examination of records and computer

analysis of relevant records. In response to the court's direc

tive, a certificate by one of plaintiffs' attorneys, Mr. Leete,

on March 21, 1974, estimated that plaintiffs' attorneys and their

research staff had devoted 225 hours reviewing company documents

and planning and coordinating their inspection (App. 87a-92a) and

this estimate did not account for a substantial amount of time

relating to the initial preparation of the case, depositions, con

ferences and computerized discovery, all of which has taken far

in excess of 1,000 hours.

7

5. To date, plaintiffs' attorneys have been forbidden during

their investigation of the case and preparation from communicating

with any members of the plaintiffs' class except for the named

plaintiffs Jimmie L. Rodgers and John A. Turner. The prohibition

on communication results from a local rule of court and a series

of oral orders by the court. The rule of court is Local Rule 34(d)

which is quoted in full above at pp. 2—3. The plaintiffs first

effort to obtain permission to communicate with class members was

by motion filed September 21, 1973. The motion for permission to

communicate (App. 44a-45a) (which accompanied a memorandum in sup

port of plaintiffs' motion for a class determination) (App.

46a-66a) alleged that plaintiffs' ability "effectively to present

the claims of class members, to discover the case, and to define

the scope of the issues with greater specificity depends m sig

nificant part on their having access to class members, to

investigate their complaints, and to supplement the available

defendants' documentary materials by interviewing their employees

(App. 44a-45a). It alleged: "At this stage, such communication

becomes appropriate and even imperative" (App. 45a). Plaintiffs

asked for a general order "allowing proper communications" and

stated that "It would be impractical and unworkable for plaintiffs

to reapply specifically for permission to communicate with particu

lar class members" (App. 45a).

8

6. The ruling of the court on the motion to communicate is

set forth below from the transcript of September 29, 1973:

THE COURT: * * *

As to discussion with individual members of

the class, if you will notify the defendants in

advance whom you intend to contact in the class

and what you intend to ask them, and what you

think you can get from them, then I will permit

you to contact them for the limited purposes that

you have set forth, giving the right to the defend

ant to object to your contacting any particular

member of the class, because it seems to me that

this is absolutely going to be an exercise in

futility when you go to an employee of the United

States Steel Corporation and ask him what testing

means were used in 1962. I can’t conceive of_him

knowing, and I think it would be a waste of time.

(App. 84a-85a)

* * *

THE COURT: The ruling of the Court is that

they can't contact people who art: uoL named as

parties until an order of Court. No person is

to be contacted without my permission. As to the

specific individual concerned after giving notice

to the defendants who the individual is and what

you expect to learn from him, then we can determine

whether this is sufficient reason to change the

general rule.

The transcript of this conference will take

the place of and will be considered the order of

this Court, no written order being necessary by

agreement of all parties. (App. 85a—86a)

7. On April 12, 1974, Honorable Sam C. Pointer, Jr., United

State District Judge for the Northern District of Alabama, signed

two consent decrees (App. 287a-355a), tendered in an employment

discrimination suit filed that day by the United States and the

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission against 9 major steel

9

companies (including U. S. Steel Corporation) and the United

Steelworkers of America, AFL-CIO-CLC (App. 278a-286a). The case

is styled United States v. Allegheny Ludlum Industries, Inc.,

C.A. No. 74-P-339, N.D. Ala. The decrees include an injunction

which purports to remedy systemic racial discrimination and sex dis

crimination in over 200 plants employing more than 65,000

minority and women workers operated by the nine steel companies,

including the Homestead Works of U. S. Steel. Promptly after

learning of the provisions of the consent decrees, plaintiffs

Rodgers and Turner, in company with other black steelworkers in

Alabama, Maryland and Texas plants, moved to intervene in the

Alabama case (App. 373a-387a), and to set aside the consent

decrees on the ground that various provisions of the decrees

were unlawful and unconstitutional (App. 388a-407a). They objected,

among other things, that the decree was unlawful in that it sanc

tioned a procedure by which the defendant companies would tender

back pay to certain minority steelworkers in return for the workers

signing waivers or releases of certain of their rights to remedy

employment discrimination. Intervenors attacked the proposed

waivers as void as against public policy and contrary to Title VII.

On June 7, 1974, Judge Pointer, after hearing arguments and

receiving extensive briefs, entered an opinion and order (App.

356a-364a, 365a-366a) permitting Rodgers and Turner (and the others

in similar cases) to intervene for the limited purpose of seeking

10

\

to stay or vacate the consent decrees, but overruling and denying

their claims that the consent decrees are illegal. The inter-

venors then filed a notice of appeal, and applied to Judge Pointer

for a stay pending appeal. The stay was denied by order and

opinion dated July 17, 1974 (App. 367a-371a, 372a). At this

writing a request for a stay pending appeal is being prepared for

submission to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit. Copies of the consent decrees, the intervenors motions

to set aside the decrees and to intervene, and Judge Pointer's

two opinions and related documents are included in the appendix

(App. 278a-525a).

8. Meanwhile, on April 17, 1974, plaintiffs Rodgers and

Turner moved in the court below for an injunction to restrain the

defendants from communicating with class members at Homestead

Works with respect to the consent decrees, including such matters

as back pay (App. 118a-123a). It was noted that the consent

decrees provided for a series of such communications and notices

by the defendants to class members, including notices of rights

under the injunctive decree respecting seniority and similar

matters, and notices advising workers of their right to obtain

back pay if they would execute releases or waivers in certain cir

cumstances and during a specified 30 day period in which back pay

offers will be tendered. Prior to a hearing on the motion for an

injunction, the parties entered into an agreement which was stated

11

to the court at a hearing on April 24, and plaintiffs withdrew

the request for an injunction (App. 126a-135a). Defense counsel

agreed to show plaintiffs' counsel copie? of any proposed com

munications to the class concerning back pay prior to their

distribution and permit plaintiffs sufficient time to renew their

objections in court and obtain a ruling prior to the communica

tion. ibid. Defendants also promised to review with plaintiffs

counsel the "format" of the explanation to be given to class

members by the Implementation Committees created by the consent

decrees. The Implementation Committees are composed of representa

tives of labor and management.

9, On June 26. 1974. plaintiffs Rodgers and Turner filed a

motion in the court below (W.D. Pa.) asking that the court grant

them permission to communicate with six named individual members

of the class, Messrs. Kermit R. White, Linwood Brosier, Abraham

Lance, Frank Moorfield, Rosse Jackson and Eugene Arrington (App.

143a-153a). The motion explained that plaintiffs' counsel had

been contacted by Mr. White and Mr. Brosier on behalf of themselves

and the other four men "for the purpose of seeking representation

for their claims of employment discrimination at Homestead Works

of United States Steel Corporation" (App. 144a). The motion

pointed out that neither Local Rule 34(d) nor the court's prior

order had specifically dealt with unsolicited requests for repre

sentation, but noted that defense counsel had by letter objected

12

to the communication. A supporting affidavit (App. 140a-142a)

by Mrs. Elizabeth Smith, Assistant Labor Director of the N.A.A.C.P.,

explained how she had been contacted with a request for information

and assistance by Messrs. White and Brosier, and how she in turn

had suggested that they contact the attorneys of the Legal Defense

Fund who she knew were involved in the Alabama litigation and

the Rodgers and Turner case.

The same June 26 motion also asked the court for permission

for plaintiffs' counsel to "Meet with members of the Homestead

Chapter of the N.A.A.C.P. to respond to said chapter's direct

request to discuss the subject of discrimination at the Homestead

Works of United States Steel Corporation" (App. 143a). The

motion pointed out the nature of the N.A.A.C.P. and its purposes,

explained the circumstances of the invitation which included a

request for information about the Alabama consent decrees and the

pending local litigation. The motion alleged specifically that

a denial of the right to communicate would violate constitution

ally protected rights of free speech and association as well as

the right of counsel to practice law. The motion relied on

N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963), and a series of succeed

ing cases (App. 147a).

10. On the same date, June 26, plaintiffs filed a related

motion entitled "Renewed Motion for Permission to Communicate with

Members of the Proposed Class" (App. 166a-170a). The latter

13

motion pointed out that the court had set January 15, 1975, as

the deadline for completion of discovery; that under the prior

orders of court counsel were unable to communicate with class mem

bers for discovery purposes, that plaintiffs had undertaken a

great deal of time consuming and costly computer analysis and

discovery of defendants' records and now needed to talk with mem

bers of the class in order to effectively represent their claims,

to define the issues and complete discovery, and that it was

impractical and unworkable for plaintiffs to apply specifically

for the right to communicate with particular class members. The

motion alleged also that it was inequitable to prohibit communi

cation by plaintiffs while the defendants could communicate with

the class pursuant to the consent decrees to offer them back pay

and seek to persuade employees to execute releases waiving their

rights.

11. On June 26, plaintiffs also filed a renewed motion to

compel answers to certain interrogatories and for production of

documents (App. 154a-165a). This motion, too, asserted plain

tiffs' understanding that the court had set the close of discovery

for January 15, 1975, and sought a ruling with respect to a large

number of interrogatories which defendants had objected to or

answered in a manner deemed inadequate by plaintiffs.

12. At a conference with the court on June 27, 1974, the

court issued a number of rulings on the motions discussed above

14

(App. 171a-189a). First, the court took up the motion to compel

answers to interrogatories and production of documents under

Rule 37. The district judge stated that it was his impression

that at an earlier conference he had said "We were going to

hold everything in limbo until January 15th [1975] to find out

what was going to happen in the South, and then we would see

what were going to do after we found out where we were" (App.

175a). Plaintiffs' counsel stated his different recollection

that January 15, 1975, was the discovery deadline, and, in any

event, strenuously objected to holding the Rodgers case in abey

ance pending developments flowing from the Alabama consent decree.

Plaintiffs' counsel objected that they were not parties to the

consent decree, had no notice of it prior to its entry, and that

they were not bound by the consent decree because they had

"never had their day in court on the determination of discrimina

tion or appropriate relief" (App. 173a). But the court ruled

"It seems to me to go forward in two different areas when it

might be moot as a result of what might happen as a result of a

consent decree is an unusual expenditure of money and a waste of

your time and mine" (App. 175a). And further: "We will talk

about further discovery in January. I want to see what is going

to happen there before we go forward with discovery on the

matter" (App. 175a).

Because of the district judge's position that this was a

15

matter he had previously' ruled on ("That's what I said, and

that's what I meant, and that's what I still mean.") (App. 175a),

there was no full argument about whether either in law or in

fact the consent decree could possibly moot the Rodgers case.

Plaintiffs could quite readily have established important rele

vant facts: First, a number of black steelworkers at Homestead

Works, who were included in the class sought to be represented

in Rodgers, would not even be tendered back pay under the consent

decree which limits back pay to workers whose date of employment

precedes January 1, 1968, and who are still employed or have

retired on pension within the last two years (App. 328a-330a).

The effect is to define a narrower class than that in Rodgers.

The class in Rodgers was defined by stipulation to include black

workers employed at Homestead Works during the period August 24,

1971, and May 1, 1973, in jobs represented by the local union

(App. 42a-43a). Second, there was widespread dissatisfaction

of black steelworkers with the consent decree as reflected by a

statement by the President of the Homestead Branch of the N.A.A.C.P.

in May 1974, asserting that there were "from 400 to 500 Black

employees who have pledged not to sign the release."

13. With respect to the motion to communicate, the court

on June 27 heard arguments and took the matter under advisement

pending considerations of briefs on the constitutional issues.

However, the court did specifically forbid Mr. Marcus from

16

attending an N.A.A.C.P. meeting during the week of July 7 (App.

189a).

14. On July 8, 1974, plaintiffs by motion (App. 190a-193a)

asked the court to enter a written order with respect to its

June 27 rulings and that the court enter an order in the terms

required by 28 U.S.C. § 1292(b) so that plaintiffs might pursue

an interlocutory appeal. Plaintiffs also asked that the court

grant a stay of its orders denying discovery and prohibiting

communication pending an appeal or application for prerogative

writs. Plaintiffs also moved for similar relief, i.e., a stay

and a section 1292(b) order in the event the court rejected

plaintiffs' motion for permission to communicate with the six

named individuals and to meet with the N.A.A.C.P. chapter. The

pleading also directed the court's attention to the statutory

requirement of expeditious handling of Title VII cases. 42 U.S.C

§ 2000e-5 (f) (5) (App. 191a-192a).

15. On July 19, 1974, the court held another conference

and ruled on the pending motions (App. 255a-276a). The court

denied the motions to certify questions to the Court of Appeals

(App. 259a). The court ruled:

As to the motion to communicate with the NAACP,

that is denied at this time without prejudice to

renewal of that motion at a time which would appear

to be more appropriate to me.

Now, as to the motion to communicate with

individuals who have requested that they discuss

i

17

matters with counsel, that motion is granted.

However, the previous order forbidding solici

tation and requiring prior Court approval of

all communications with any other individuals

is left intact. You may talk to those six

individuals, but you may not solicit anybody

else, nor may you make any communications with

anybody else except pursuant to Court approval.

(App. 259a-260a)

Subsequently, in the conference, defense counsel argued that only

two of the six individuals had contacted Mr. Marcus representing

the other four, and that accordingly Mr. Marcus should be limited

to communicating with Mr. White and Mr. Brosier. The court then

prescribed an affidavit procedure by which plaintiffs' counsel

I

may not talk to any class members until after they have obtained

an affidavit from the class members stating how they happened to

contact counsel. The ruling is reflected in the following

colloquy:

THE COURT: How did you get six?

MR. MARCUS: I stated in my motion that the

two individuals that Mr. DeForest has identified

contacted me on their behalf and on behalf of

four other gentlemen who are also listed in the

motion. They had specific authorization from

those gentlemen to so contact me, and they asked

that I represent all of those individuals.

THE COURT: You file an affidavit with the

Court by those two individuals stating that, and

then you may contact the other four.

MR. DeFOREST: Your Honor, I have one problem.

I would like it made clear that because I fear

that we will have repeated situations where cer

tain persons will call and claim they represent

nine, ten, or twenty persons, and then accordingly

18

Mr. Marcus may communicate with them. Is that

right?

THE COURT: No. He may not communicate with

anybody beyond the two plus the four after the

filing of the affidavit.

MR. MARCUS: Unless I seek further approval

of the Court.

THE COURT: We will see what happens.

MR. DeFOREST: Would the Court be amenable

that Mr. Marcus contact the other four if each

called individually and stated —

THE COURT: Or by the filing of an affidavit

stating they want to see him.

MR. DeFOREST: That would be better.

MR. MARCUS: I am a little confused. Do you

want an affidavit of the two individuals stating

■chat they represent the other luui?

THE COURT: And the four individuals stating

that, that is correct.

MR. MARCUS: I can't get an affidavit if I

don't communicate with the other four.

THE COURT: You may communicate to the extent

to ask for such an affidavit. If that is filed,

then you may communicate with them. In other

words, I don't want to set up a system of runners

here.

MR. MARCUS: Neither do I.

THE COURT: So I will limit it to the two plus

the four with those affidavits, but before you talk

to them about the merits, I want you to have the

affidavits and file them. (App. 261a-262a)

16. At the July 19, 1974, conference, the court also took

up the matter of a proposed letter to all class members and an

19

attached outline of the consent decree which had then recently

been approved by Judge Pointer. Defendants had undertaken

before Judge Pointer to submit the notice to judges who had pend

ing local cases. Plaintiffs advised the court that they had

been given no notice or opportunity to be heard by Judge Pointer

on the letter and outline but that they were seeking a hearing

before Judge Pointer to revise the notice. Plaintiffs submitted

their proposed changes to Judge Teitelbaum. Judge Teitelbaum

ruled that he would not pass on objections to the'letter to be

sent at the Homestead Works but would leave the matter entirely

to Judge Pointer (App. 257a-259a). In the course of the proceed

ings Judge Teitelbaum also stated that if Judge Pointer authorized

plaintiffs to communicate with the class he would not object:

THE COURT: If Judge Pointer will authorize you

to send out a letter, I have no objection.

MR. MARCUS: Or to communicate with any member

of this class.

THE COURT: I have no objection if he does it.

I am not going to do it myself. That is what I'm

saying. If Judge Pointer wants to do it, the

case is with him, and he is far more familiar with

the people to explain why the people shouldn't

approve the settlement by solicitation, by letter,

orally or any other way.

MR. SCHNAPPER: That is the problem we will

take up with him.

THE COURT: I don't want to be a side agent

operating at the side affecting something before

another judge. (App. 266a)

20

Subsequently, at a conference with Judge Pointer on July 23,

1974, Judge Pointer ruled orally that he had no objection to

any communication with the class in Homestead Works which might

be permitted by Judge Teitelbaum, nor did he believe that it

would interfere with the consent decree if the Rodgers litigation

proceeded (App. 518a-520a). This was reported to Judge Teitelbaum

in a Report to the Court containing the transcript of the July 23

conference (App. 277aa-277bb).

STATEMENT OF ISSUES PRESENTED AND RELIEF SOUGHT

This petition presents the following issues:

1. Whether the orders of court prohibiting plaintiffs'

counsel from meeting with an N.A.A.C.P. chapter are unconotitu—

tional in violation of the Due Process Clause of the Fifth

Amendment and the First Amendment protections of freedom of speech,

freedom of association, and privacy of association in that:

a. The order overbroadly prohibits constitutionally

protected First Amendment activities.

b. The order is a discriminatory regulation of free

speech which favors the steel company and union and disadvantages

black employees.

2. Whether Local Rule 34(d) of the Western District of

Pennsylvania is unconstitutional on its face and as applied in

violation of the Due Process Clause and the First Amendment

21

protections of freedom of speech, freedom of association and

privacy of association in that the rule overbroadly infringes

on constitutionally protected activities.

3. Whether the orders of court applying Local Rule

34(d) are unconstitutional in violation of the Due Process

Clause and the First Amendment in that:

a. The requirement that there be no communication

by counsel with class members who approach counsel without

first filing an affidavit in court before discussing substan

tive matters (i) violates the First Amendment rights of freedom

of association and privacy of association and free speech as

well as (ii) the right to access to legal counsel and also

(iii) unfairly and discriminatorily disadvantages plaintiffs

in the presentation of their case.

b. The requirement that there be no communication

by plaintiffs' counsel with class members on counsel's initia

tive in investigating the case and gathering facts without first

disclosing the identity of the class members and the expected

nature of the facts to be learned from the class members vio

lates (i) the First Amendment rights of free speech, freedom

of association and privacy of association and also (ii) unfairly

and discriminatorily disadvantages plaintiffs in the presenta

tion of their case.

",22 -

4. Whether the order of court staying all discovery

and delaying all proceedings in this case, including a class

action determination, until at least January 15, 1975, is an

abuse of discretion and contrary to law in that:

a. It is contrary- to the provisions of 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e-5(f) (5) ;

b. It violates the plaintiffs' right to due process

of law by impairing their rights in this pending case and

threatening to defeat their rights on the basis of a consent

decree in another court entered without notice or hearing to

plaintiffs and without their agreement;

c. It is contrary to Rule 23(c)(1), Fed. R. Civ. P.

The relief requested is more fully set forth above at

pages 2-3. Petitioners seek an order vacating or prohibiting

enforcement of the several orders of court and the rule of

court described in detail above.

23

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRITS

Introduction

This is an extraordinary case in several aspects. The

issues of freedom of speech, freedom of association and privacy

of association and right to counsel are raised by orders of the

court below which restrict free speech and association in a

sweeping and unprecedented fashion. The order forbidding, plain

tiffs' counsel from even attending a meeting of a local N.A.A.C.P.

chapter, without regard to the content of their speech, asserts

a right to regulate free association more broad than that ever

claimed since the Supreme Court repudiated Alabama's total

repression of the N.A.A.C.P. by ousting it from the State.

N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama ex rel. Flowers, 377 U.S. 288 (1964). ihe

several orders fashioned below imposing procedural restraints on

communication between counsel and black steelworkers involve

narrower, but no less important issues of free speech and private

communication, as well as substantial claims of unfair discrim

ination. These restrictive orders stem from a local rule of

court which more broadly restricts free speech than any other

federal court rule or order our research has uncovered.

The case is extraordinary, too, because the present issues

arise out of an extraordinary event. That event is the effort of

major steel companies and federal government agencies, respec

tively charged with obeying and enforcing fair employment laws,

24

to compromise the employment discrimination claim of every blc*ck

steelworker in the nation by an agreement negotiated without the

participation of a single black worker's representative. The

consent decree is now used to justify an order below which

stays all proceedings and thus to impair the rights of black

steelworkers to pursue their statutory remedies in a pending

case.

Prerogative writs are appropriate because the district

court's oral orders and rule of court are "a clear abuse of

discretion," LaBuy v. Howes Leather Co., 352 U.S. 249, 257

(1957), and a judicial "usurpation of power," De Beers Consoli

dation Mines Ltd, v. United States, 325 U.S. 212, 217 (1945).

These unprecedented rulings also present an issue of first

impression" proper for the exercise of this Court s supervisory

power over the administration of justice. Schlagenhauf_v_.— Holdg_r

379 U.S. 104, 110-12 (1964). In such circumstances, "the writ

serves a vital corrective and didactic function," Will v. United

States, 389 U.S. 90, 107 (1967); Rapp v. Van Dusen, 350 F.2d 806,

811-12 (3rd Cir. 1965); Texaco, Inc, v. Borda, 383 F.2d 607 (3rd

Cir. 1967). See also, Investment Properties International, Ltd.

v. IQS, Ltd., 459 F.2d 705, 707 (2nd Cir. 1972). Mandamus is

the more fitting remedy when rulings and local rules of court

infringe upon constitutional rights and Civil Rights Act policies

Sanders v. Russell, 401 F.2d 241 (5th Cir. 1968); International

Products Corp. v. Koons, 325 F.2d 403, 408 (2nd Cir. 1963).

25

I.

The Orders Forbidding Plaintiffs' Attorneys From

Meeting with the Homestead, Pennsylvania Branch

of the N.A.A.C.P. Are Unconstitutional.

On June 27, the district court absolutely forbade plaintiffs'

counsel Mr. Marcus and his associates, some of whom are staff

lawyers employed by the N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc., from attending a meeting of the Homestead Branch of

the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

which was scheduled for the week of July 7. Thereafter, on

July 19, the district court reiterated its order and forbade

their attendance at any meeting of the branch "without preju

dice to renewal of that motion at a time which would appear more

appropriate to me." The court was informed that the N.A.A.C.P.

chapter had requested information about the Alabama consent

decrees and the pending local litigation, and had issued an

unsolicited invitation to plaintiffs' attorneys. The court was

also informed that the defendants were then currently engaged in

preparing to distribute letters and related materials to class

members discussing the consent decrees. It was also generally

understood that the Homestead Branch membership included persons

within the putative class in the Rodgers case.

The order of court is an unconstitutional prior restraint

of free speech. Moreover, it flatly and broadly prohibits all

communication and associational activities, however lawful or

26

innocuous, between counsel and the branch. Prior restraints

of free speech grounded upon infinitely more solid showings

that speech would do harm than anything in this record have

repeatedly been held unconstitutional. Organization for a

Better Austin v. Keefe, 402 U.S. 415 (1971). The Supreme Court

said in that case:

Any prior restraint on expression comes to

this Court with a "heavy presumption" against

its constitutional validity. Carroll v.

Princess Anne, 393 U.S. 175, 181 (1968);

Bantam Books, Inc. v. Sullivan, 372 U.S. 58,

70 (1963). Respondent thus carries a heavy

burden of showing a justification for the

imposition of such a restraint. (402 U.S.

at 419)

The district court has put forth no clear justification for

the prior restraint imposed in this case. The ruling may be

examined in light of the parties' contentions below. The

defendant company contended that restraint should be imposed to

prevent plaintiffs' attorneys from making erroneous statements

of law or fact. The brief filed below said:

The potential dangers of such communications

are obvious. Not only might counsel for plain

tiffs misstate, even though unintentionally, the

application of the Consent Decrees to the alleged

Rodgers class, but they might also give erroneous

opinions as to present status and future course

or results in the instant litigation. (App. 216a)

The defendant union made a similar argument that there was an

"everpresent danger that plaintiffs' counsel will misrepresent

the present status of this lawsuit and the effect of the Consent

Decree upon it" (App. 247a).

27

We think it plain that these arguments for prior restraint

are insufficient. Imposition of a prior restraint of speech

to protect class members who seek counsel from the possibility

of obtaining mistaken facts or bad advice is simply beyond

the power of a court under the First Amendment. The suggestion

of the company that members of a civil rights organization must

be protected from even "unintentional" misstatements by an

attorney stretches the claim to a demand for total suppression

of free speech. Only by keeping silent can one avoid an "unin

tentional" error. "__ [T]he Constitution protects expression

and association without regard to -- the truth, popularity

or social utility of the ideas and beliefs which are offered."

N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 U.S. 415, 444-445 (1963); see also,

Wood v. Georgia, 370 U.S. 375, 387 (1962). We submit that the

accuracy of the facts that plaintiffs' attorneys give the

N.A.A.C.P. branch is no more the business of the defendant than

it is plaintiffs' business what facts the company lawyers tell

the executives of the steel company or their shareholders. Nor

is it the proper concern of the court to restrain in advance

citizens, who freely join a civil rights organization, from

freely communicating with lawyers about matters of mutual concern.

The court below did make plain that the prior restraint was

1/

not merely to prevent soliciation of clients. When Mr. Marcus

1/ See infra, n. 3, at pp. 44-45.

28

asked the judge if he and his colleagues could attend the meeting

if they would promise not to represent any of the individuals

there, the judge responded to the effect that his concern was

that they might "sabotage the settlement in Judge Pointer's

court." The colloquy was as follows:

MR. MARCUS: Your Honor, I wonder if we

could suggest an alternative since this is

your main concern in dealing with this problem

of equal time and communicating with respect

to matters that the defendants are being per

mitted to communicate, and that is, if we will

agree not to represent in any action, other

than a class action that may be pending, those

individuals who would like us to discuss the

consent decrees or the pending litigation with

them, would that be satisfactory to do this?

THE COURT: That is exactly what I don't

want. That is ovaoHv what I do not want.

MR. MARCUS: This avoids any solicitation

and barratry where we agree in advance not to

represent them.

THE COURT: That is worse than enabling

people to go to an alleged interested party

and attempt to sabotage the settlement in

Judge Pointer's court, and I don't want that

to happen. (App. 265a-266a)

Thus, Judge Teitelbaum’s concern with communications which

he felt would "sabotage" the settlement has resulted in a prior

restraint which was never even suggested by Judge Pointer who

approved the settlement. Judge Pointer has not seen fit to use

his judicial powers either to persuade any black steelworkers

to accept the settlement or to interfere in any manner with their

29

right to oppose it. We believe that members of the N.A.A.C.P.

and any other black steelworkers have a right to freely organ

ize to oppose the settlement in whole or in part and to seek

guidance from lawyers knowledgeable about the case, free of any

prior restraints on their communications.

i

The activities of the N.A.A.C.P. and Legal Defense Fund

attorneys have been held by the Supreme Court to be within the

sphere of constitutionally protected activity. It is quite

clear then that an order banning lawyers from attending an

N.A.A.C.P. meeting touches on constitutionally protected rights.

The Supreme Court in N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963),

has specifically made clear that restriction of political

2/

2/ Judge Pointer, when asked on July 23, 1974, if plaintiffs

could communicate with the class in Pittsburgh, stated:

THE COURT: It's a very touchy area, as you

can understand, I'm sure, when you present it

in that light.

I think the best thing that I can say is

that I have no objection to that procedure.

I think that particular problem is most

directly a matter for that District Court and

it's [sic] local rules and the way it analyzes

such.

I can see no conflict with the administra

tion of the consent decree if you were to be

given that permission.

And that's about all I can say. (App. 518a)

30

association of the exact kind here at stake is constitutionally

impermissible:

In the context of NAACP objectives, litigation is

not a technique of resolving private differences,

it is a means for achieving the lawful objectives

of equality of treatment by all government, fed

eral, state and local, for the members of the Negro

community in this country. It is thus a form of

political expression.

* * *

The NAA.CP is not a conventional political

party; but the litigation it assists, while serv

ing to vindicate the legal rights of members of

the American Negro community, at the same time

and perhaps more importantly, makes possible the

distinctive contribution of a minority group to

the ideas and beliefs of our society. For such

a group, association for litigation may be the

most effective form of political association.

(371 U.S. at 429, 431.)

The Button decision has spawned a line of cases that ratify this

principle. Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen v. Virginia exrel.

State Bar, 377 U.S. 1 (1964); United Mine Workers v. Illinois

State Bar Association, 389 U.S. 217 (1967); United Transporta

tion Union v. State Bar of Michigan, 401 U.S. 576 (1971). The

common thread running through our decisions in fflACPiv.— Button ,

Trainmen and United Mine Workers is that collective activity

undertaken to obtain meaningful access to the courts is a federal

right within the protection of the First Amendment." United

Transportation Union, supra, 401 U.S. at 585. Judicial injunc

tions of "solicitation" which were far more narrowly tailored

than the prohibition here— and which were issued after, rather

31

than before, a hearing on the fact of solicitation— have

repeatedly been held unconstitutional. E.g., United Transporta

tion Union, supra.

Plaintiffs' counse’l are not stripped of their First Amend

ment rights simply because they are attorneys before the bar of

the court. Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen, supra, 377 U.S.

1, 8. Judicial attempts to curb even broad-scale, mass-media

dissemination of "out-of-court publications pertaining to a

pending case," Bridges v. California, 314 U.S. 252, 268 (1941),

have repeatedly been held unconstitutional in the absence of a

demonstration of "clear and present danger" of "actual inter

ference" with the conduct of the litigation, amounting to "ser

ious ... harm to the administration of law," Wood v. Georgia,

370 U.S. 375, 384, 393 (1962). The unbroken line of cases from

Bridges to Wood, which includes Craig v. Harney, 331 U.S. 252

(1941); Pennekamp v. Florida, 328 U.S. 331 (1946); and In re

Sawyer, 360 U.S. 622 (1959), ought to dispel any notion that

lawyers are without free speech rights to talk about pending

cases. To justify punishment (let alone prior restraint) of

speech there must be "an imminent, not merely a likely, threat

to the administration of justice. The danger must not be remote

or even probable; it must immediately imperil." Craig v. Harney,

supra, 331 U.S. at 376.

The overbroad nature of the restraint on speech is still

32

another reason the district court's order violates the First

Amendment. The Button opinion emphasized the "danger of tolerat

ing, in the area of First Amendment freedoms, the existence of

a penal statute susceptible of sweeping and improper applica

tion." 371 U.S. at 433. "Because First Amendment freedoms

need breathing space to survive, government may regulate in the

area only with narrow specificity." 371 U.S. at 433.

The orders of June 27 and July 19 plainly are overbroad

in banning all meetings by counsel with the branch, irrespective

of what is said. Mr. Marcus would be in jeopardy of contempt

for violation of the order if he attended the meetings without

talking at all, if he attended and spoke only of unrelated sub

jects, if he spoke about the litigation in only the most

restrained and proper manner, or if he limited his communica

tion to distributing copies of public documents on file in the

courts. Thus, the broad sweep of the order plainly prohibits

entirely lawful First Amendment protected conduct. The orders

plainly fail the test of "narrow specificity required of all

regulation in the area of First Amendment freedoms.

In the context of this case, the ban on plaintiffs' counsel

meeting with the N.A.A.C.P. branch is a discriminatory regula

tion of free speech which unfairly disadvantages those black

employees who wish to be informed about the case or to oppose

the consent decreesand seek additional relief not agreed to by

33

the defendants. The court's statement that it wished to pre

vent what it termed "sabotage" of the settlement, establishes

the discriminatory quality of the ban on meeting with the

N.A.A.C.P. We submit that each black worker at Homestead Works

has the right to oppose the settlement, to refuse to sign a

waiver of his rights, and to ask the courts in a proper proceed

ing to grant more relief from the pattern of systematic discrim

ination they have suffered in violation of law. Every black

worker has the right to meet with others to advance his point of

view, to join an organization such as the N.A.A.C.P. which takes

an interest in the matter, and to work collectively to advance

his views. And every black worker at Homestead Works has the

right to choose to hear a speech about the problem of racial

discrimination in the United States Steel Corporation by a law

yer who knows something about it and who is engaged in a lawsuit

to remedy the discrimination. And certainly every black steel

worker at Homestead Works has the right to try to communicate

with lawyers who purport to represent them in a class action

involving their jobs, their salaries, their promotions, their

back pay, and other such matters. And where such lawyers have an

obligation under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure to insure

the fair and adequate representation of such black workers in

court, it is entirely natural that black workers should seek

information from those lawyers. All these rights are infringed

34

by the order of the court below in order to prevent "sabotage"

of the settlement in the Alabama case.

Such a regulation of speech is so one-sided and unfair in

its impact upon the efforts of black workers to oppose the

defendants in the case as to constitute a denial of due process

of law. Due process is violated by a federally imposed discrim

ination which, if imposed by a state, would violate the Equal

Protection Clause. Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954).

The discrimination is all the more evident in the context of

the freedom of communication enjoyed by the defendants. Not

only are the defense counsel entirely free to consult with their

own clients in respect to any matters relevant to the conduct of

the lawsuit, their clients also have virtually limitless oppor

tunity to communicate with black steelworkers in the regular

course of business at the steel plants and in the regular course

of the conduct of union affairs. And beyond all that, the

defendants have judicial sanction to communicate with the black

steelworkers to explain the meaning of the consent decrees and

at a later date to offer them sums of back pay in return for

releases of workers' Title VII claims. Currently "implementa

tion committee" are meeting with workers explaining the consent

decree. We are on the verge of a judicially sanctioned "market

place" by which the defendants propose to buy up Title VII

rights of tens of thousands of black workers. The propriety of

35

such a procedure is at issue in the Fifth Circuit appeal from

the consent decree. But the fact remains that black steel

workers' vital rights are at stake and they have a plain right

to know facts about these developments from sources other than

the defendants who committed violations of the equal employment

laws.

It is of some moment, perhaps, that the defendants in

signing the consent decree still vigorously deny that they ever

practiced discrimination. It ought to be evident that some

black workers have a desire and a right to talk to lawyers who,

in at least one reported case, have proved that the United

States Steel Corporation does have a systemic pattern of discrim

ination. See, e.g., United States v. United States_Steely

Corporation, 371 F. Supp. 1045 (N.D. Ala. 1973).

"The right to equal protection of the laws in the exercise

of those freedoms of speech and religion protected by the First

and Fourteenth Amendments, has a firmer foundation than the

whims or personal opinions of a local governing body," Niemotko

v. Maryland, 340 U.S. 268, 272 (1951); Thornhill v. Alabama, 310

U.S. 88, 97-98 (1940). The danger is always that "public authority

with an evil eye and an unequal hand" will make "unjust and

illegal discriminations between persons in similar circumstances,"

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356, 373-74 (1886). No government

power, as Mr. Justice Black stated in a related free speech area,

can

36

provide by law what matters of public interest

people whom it allows to assemble on its streets

may or may not discuss. This seems to me to be

censorship in a most odious form, unconstitu

tional under the First and Fourteenth Amendments.

And to deny this appellant and his group use of

the streets because of their views against racial

discrimination, while allowing other groups to

use the streets to voice opinions on other sub

jects, also amounts to an invidious discrimination

forbidden by the equal protection clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment.

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 559, 581 (1965) (concurring opinion).

See also, Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. d36, 557 (1965)..

The unconstitutionality of the ban on meeting with the

N.A.A.C.P. is not alleviated by the court's ruling that a meet

ing might be permitted at some unspecified future "appropriate"

time. We think black steelworkers have a right to decide when

they want to learn of the status of a case affecting their rights,

and when they want to begin to organize to oppose the company s

efforts. They cannot be limited in these free speech and free

association choices by any notions of the defendants that it is

not yet necessary for them to know of the consent decree because

the defendants are not yet ready to tender back pay to black

workers.

37

II.

Local Rule 34(d) Is Unconstitutional On Its

Face And As Applied In This Civil Rights Case

At issue is a rule of court requiring that no communication

concerning the class action be made in any way by any party or

counsel with any potential or actual class member, until such

time as the court shall order. We submit that the rule is a

classic instance of a provision that "casts its net across a

broad range of associational activities" and "contains the fatal

defect of overbreadth," United States v. Roble, 389 U.S. 258,

265-66 (1967). The district court should not have relied on it

for this or any case.

The Constitutionally-Required Standard

The Supreme Court has emphatically declared that courts

should show no deference to regulations impinging on First Amend

ment freedoms. It has become axiomatic that, precision of

regulation must be the touchstone in an area so closely touching

our most precious freedoms," N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, supra, 371

U.S. at 438. The need for such an analytical perspective is

obvious:

Our decision today simply recognizes that when

legislative concerns are expressed in a statute

which imposes a substantial burden on protected

38

First Amendment activities, Congress must

achieve its goal by means which have a less

drastic impact on the continued vitality of

First Amendment freedoms. Shelton v. Tucker,

. ..; cf. United States v. Brown, 381 U.S.

437 ... (1965). The Constitution and the

basic position of First Amendment rights in

our democratic fabric demand nothing less.

United States v. Roble, supra, 389 U.S. at

267-78.

See also, e.g., Aptheker v. Secretary of State, 378 U.S. 500,

508 (1964); Note, The First Amendment Overbreadth Doctrine, 83

Harv. L. Rev. 844 (1970).

Moreover, the Supreme Court has largely formulated the

standards courts should apply when scrutinizing overbroad

regulations of "collective activity undertaken to obtain mean

ingful access to the courts" in the line of cases running from

N.A..A.C.P. v. Button through United Transportation Union. See

supra at 30-31. First, "solicitation" is not a talisman that

makes First Amendment freedoms vanish:

We meet at the outset the contention that

"solicitation" is wholly outside the area

of freedoms protected by the First Amendment.

To this contention there are two answers.

The first is that a state cannot foreclose

the exercise of constitutional rights by

mere labels. The second is that abstract

discussion is not the only species of com

munication which the Constitution protects;

the First Amendment also protects vigorous

advocacy, certainly of lawful ends, against

governmental intrusion. Thomas v. Collins,

323 U.S. 516, 537 ...; Herndon v. Lowry, 301

U.S. 242, 259-264 ... Cf. Cantwell v.

Connecticut, 310 U.S. 296 ...; Stromberg v.

California, 283 U.S. 359 ...; Terminiello v.

39

Chicago, 337 U.S. 1 NAACP v. Button,

supra, 371 U.S. at 429.

In short, government "may not, under the guise of prohibiting

professional misconduct, ignore constitutional rights," N.A.A_.C .P_._

v. Button, supra, 371 U.S. at 439. See also, Brotherhood of.

Railroad Trainmen, supra, 377 U.S. at 6. Second, courts must

look to the actual impact of governmental regulation on First

Amendment freedoms notwithstanding that the subject of the

regulation is within the ambit of legislative competence:

The First Amendment would, however, be a

hollow promise if it left government free

to destroy or evade its guarantees by indi

rect restraints so long as no law is passed

that prohibits free speech, press, petition

, . V I . . ^ r- .■. t»t^ V i a v o • H V i o r ' i ^ - F o T f3X U.kJ *-* J *~W w • • • — * —

repeatedly held that laws which actually

effect the exercise of these vital rights

cannot be sustained merely because they

were enacted for the purpose of dealing

with some evil within the state's legisla

tive competence, or even because the laws

do in fact provide helpful means of deal

ing with such an evil. United Mine V7orkers,

supra, 389 U.S. at 222.

Third, there is a presumption in the area of First Amendment

activity that "[b]road prophylactic rules ... are suspect.

See, e.g., Near v. Minnesota, 283 U.S. 697 ...? Shelton v.

Tucker, 364 U.S. 479 ...; Louisiana ex rel. Gremillion v.

National Asso. for Advancement of Colored People, 366 U.S.

293 ... Cf. Schneider v. State, 308 U.S. 147, 162 ..." N . A . A . C . P...

- 40

V . Button, supra. 371 U.S. at 938. Fourth, government must

advance a "substantial regulatory interest, in the form of

substantial evils flowing from petitioner's activities, which

can justify the broad prohibition which it has imposed,"

N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, supra, 371 U.S. at 44. See also, Brother

hood of Railroad. Trainmen, supra, 377 U.S. at 7-8. Fifth, in

the area of First Amendment rights courts will hesitate to

draw lines to save overbroad regulations:

If the line drawn by the decree between the

permitted and prohibited activities of the

NAACP, its members, and lawyers is an

"ambiguous one, we will not presume that

the statute curtails constitutionally pro

tected activity as little as possible.

t i j _________3 _ „ j . r ^ -! V\ 1 « o f a f u f n r t r i r a n n p -1' C/i. o V4l-» —•- — — - - - - - — — J .

ness are strict in the area of free expression.

[References omitted]. N.A.A.C.P. v. Button,

supra, 371 U.S. at 429.

Sixth, vigorous litigation against racial discrimination or in

the public interest generally is subject to a realistic appraisal,

sensitive to its unique character in our jurisprudence:

Resort to the courts to seek vindication of

constitutional rights is a different matter

from the oppressive, malicious, or avaricious

use of the legal process for purely personal

gain. Lawsuits attacking racial discrimination,

at least in Virginia, are neither very profit

able nor very popular. They are not an object

of general competition among Virginia lawyers;

the problem is rather one of an apparent dearth

of lawyers who are willing to undertake such

litigation. ... We realize that an NAACP lawyer

_ 41

must derive personal satisfaction from partici

pation in litigation on behalf of Negro rights,

else he would hardly be inclined to participate

at the risk of financial sacrifice. But this

would not seem to be the kind of interest or

motive which induces criminal conduct. N.A.A.C.P.

v. Button, supra, 371 U.S. at 443-44.

See also, Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen, supra, 377 U.S. at 7.

It is these standards that this Court must apply to the

face of Local Rule 34(d). To do otherwise is to forsake the

special place the Supreme Court has recognized for the exercise

of First Amendment freedoms to advance judicial resolution of

great social controversies and the rule of law.

The Title VII Action Context

One other preliminary matter deserves mention: This

Court cannot but be struck that this overbreadth issue arises

in the specific factual context of a class action suit author

ized by Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. A less

likely setting for the district court to blind itself to First

Amendment command can hardly be conceived of. For to do so

is also to blind oneself to high public policy favoring

vigorous prosecution of employment discrimination actions.

Clearly, fear of ambulance-chasing and kindred concerns are,

at the very least, irrelevant. There has never been the slightest

suggestion that plaintiffs' counsel have solicited any clients

in this case.

42

The American Bar Association has long held that the

ordinary rules against solicitation are to be relaxed when

litigation is "wholesome and beneficial," ABA COMM. ON PROFES

SIONAL ETHICS, OPINIONS, No. 148, at 311 (1935); and the Con

gress of the United States has determined to encourage 1964

Civil Rights Act litigation in general, and Title VII litigation

in particular, by authorizing awards of attorney's fees for

that very purpose. See Newman v. Piggie Parh Enterprises, Inc.,

390 U.S. 400, 401 (1968); Schaeffer v. San Diego Yellow Cabs,

Inc., 462 F. 2d 1002, 1008 (9th Cir. 1972); Robinson v_._

Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791, 804 (4th Cir.), cert, dismissed,

a r\ a r t r* i r\ r\t? /I m i \ . t Kfi 1 1 o /l. T? , R R (I V V J \ / J- / / " rn — «• ---- 1~- r “ *

Cir. 1971); Johnson v. Georgia Highway Egress, 488 F.2d 714

(5th Cir. 1974).

A plaintiff's attorney who handles a class action Title

VII case with no other arrangement for, or prospect of, finan

cial remuneration than court-ordered attorney's fees, would

therefore plainly be permitted to solicit additional named

plaintiffs under the familiar principles of, e.g., ABA COMM. ON

PROFESSIONAL ETHICS, OPINIONS, No. 148 (1935); ABA COMM. ON

PROFESSIONAL ETHICS, INFORMAL OPINIONS, No. 992 (1967) ; ABA

COMM. ON PROFESSIONAL ETHICS, INFORMAL OPINIONS, No. 888 (1965);

43

ABA COMM. ON PROFESSIONAL ETHICS, INFORMAL OPINIONS, No. 786

(1964); see also, D.C. BAR ASSN. COMM. ON LEGAL ETHICS AND

GRIEVANCE, REPORT (January 26, 1971), holding that advertise

ments giving legal advice and offering free legal services

were not improper solicitation; c_f. N.A.A.C.P. v. Patty, 159

F. Supp. 503, 522 (E.D. Va. 1958); In re Ades, 6 F. Supp. 467

(D. Md. 1934), and could not constitutionally be restriiined

from doing so under the line of First Amendment cases running

from N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963), to United

Transportation Union v. State Bar of Michigan, 401 U.S. 576

(1971). This is particularly so inasmuch as it is the court

„ J L * r r J 1 7 ^ J — • - — 1 7 - — •! m a w *V> /*, v * V> * r> s iV v r« 4 * T5 n 4 - ■? 3 1

W l l x t . i l W X X X V - V t u t u u x x j '-*•'— W**s^*. •>•**«* — — —

a fee the attorney should receive at the conclusion of the

litigation, and inasmuch as the amount of that fee would not. 2/oridinarily be affected by the number of named plaintiffs.