United States v. Caldwell Brief Amius Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United States v. Caldwell Brief Amius Curiae, 1971. 126f5c51-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/26c37d74-c0ac-4baf-84ca-a4eb4f31a303/united-states-v-caldwell-brief-amius-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

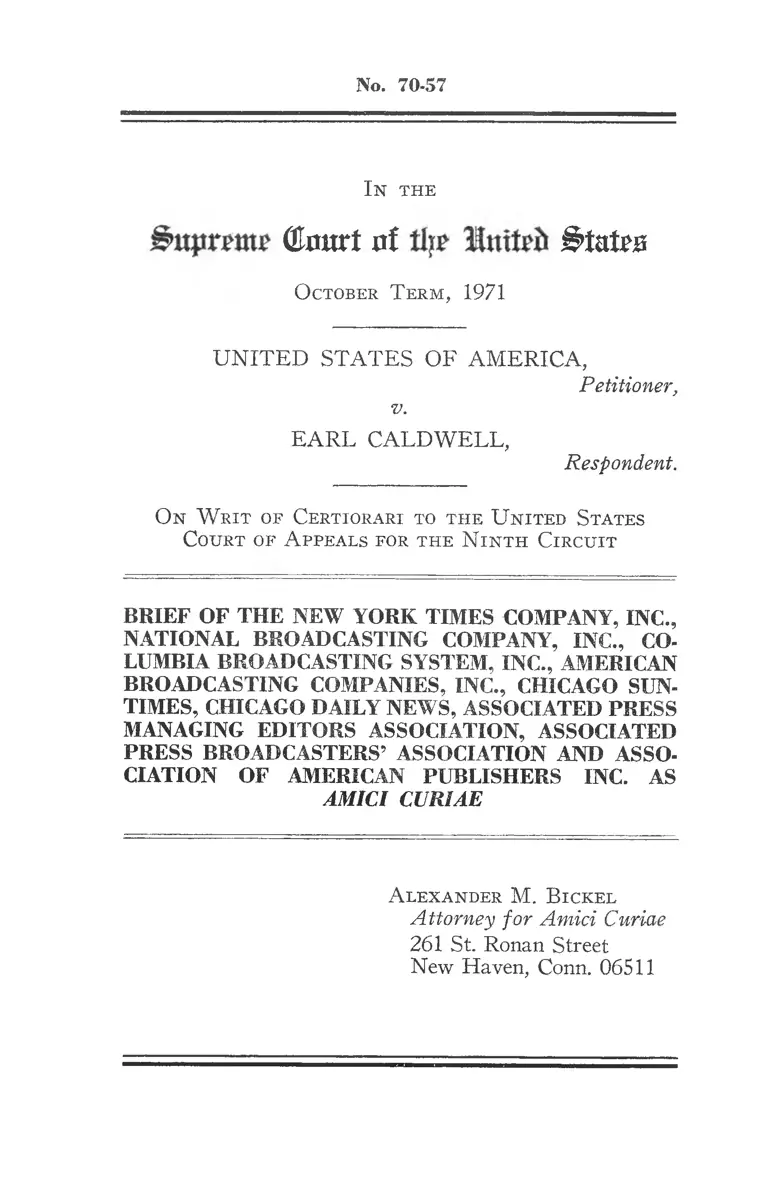

No. 70-57

I n th e

(Bxtmt of §>UUb

O ctober T erm , 1971

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Petitioner,

V.

EARL CALDWELL,

Respondent.

O n W r it of Certiorari to t h e U nited States

Court of A ppeals for t h e N in t h C ir c u it

BRIEF OF THE NEW YORK TIMES COMPANY, INC,,

NATIONAL BROADCASTING COMPANY, INC., CO-

LTOIBIA BROADCASTING SYSTEM, INC., AMERICAN

BROADCASTING COMPANIES, INC., CHICAGO SUN-

TIMES, CHICAGO DAILY NEWS, ASSOCIATED PRESS

MANAGING EDITORS ASSOCIATION, ASSOCIATED

PRESS BROADCASTERS’ ASSOCIATION AND ASSO

CIATION OF AMERICAN PUBLISHERS INC. AS

AMICI CURIAE

A lexander M. B ickel

Attorney for Amici Curiae

261 St. Ronan Street

New Haven, Conn. 06511

Of Counsel:

J a m es C. G oodale

Vice President and General

Counsel

The New York Times

Company, Inc.

229 West 43rd Street

New York, N. Y. 10036

George P . F e l l e m a n

229 West 43rd Street

New York, N. Y. 10036

Attorneys for The New York

Times Company, Inc.

A la n J . H r u sk a

R obert S. R if k in d

A n t h o n y A . D ea n

Cr a v a th , S w a in e & M oore

One Chase Manhattan Plaza

New York, N. Y. 10005

R a l p h E. G oldberg

51 West 52nd Street

New York, N. Y. 10019

Attorneys for Columbia

Broadcasting System, Inc.

L a w r en c e J. McKay

F loyd A bram s

D a n ie l S h e e h a n

Ca h il l , G ordon, S o n n e t t ,

R e in d e l & O h l

80 Pine Street

New York, N. Y. 10005

CoRYDON B. D u n h a m

Vice President and General Counsel

National Broadcasting Company, Inc.

30 Rockefeller Plaza

New York, N. Y. 10020

Attorneys for National

Broadcasting Company, Inc.

C larence J . F ried

P h il ip R . F orlenza

H a w k in s , D ela field & W ood

67 Wall Street

New York, N. Y. 10005

Attorneys for American

Broadcasting Companies, Inc.

E dward C. W allace

A r t h u r F. A b elm a n

W e il , G o tsh a l & M anges

767 Fifth Avenue

New York, N. Y. 10022

Attorneys for Association

of American Publishers

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Opinions Below.............................................................. 1

Jurisdiction .................................................................... 2

Consent of the P a rtie s ..................................... ............ 2

Question Presented......................................... 2

Constitutional Provisions.............................. 2

Interest of the A m ic i .................................................... 2

Statement........................................................................ 5

Summary of A rgum ent..................... ............................... 7

Argument ...................................................................... 9

I. Introduction ..................................................... 9

II. The right of readers and viewers freely to be

informed by print or electronic news media is

abridged, in violation of the First and Four

teenth Amendments, if State or Federal gov

ernments can commonly compel reporters for

such media to identify confidential sources or to

divulge information obtained in confidence . . . 13

A. The Constitutional foundation of the

r ig h t .......................................................... 13

B. The factual foundation of the right . . . . 16

C. The perimeters of the r ig h t .................... 23

III. A reporter cannot, consistently with the Con

stitution be forced to divulge sources to a gov

ernmental investigative body unless three mini

mal tests have been met. Of these, the first

two are procedural, requiring the establishment

of probable cause that a crime has been com

mitted of which the reporter has knowledge

and a showing of the government’s inability to

obtain the information sought by the reporter

by alternative means. Application for the two

procedural rules is sufficient to dispose of the

cases before the C o u rt...................................... 29

11

PAGE

A. The three tests ........................................ 29

B. Limits of the power to compel testimony. . 30

C. Procedure, the overbreadth doctrine, and

the rule of the compelling in terest........... 34

D. Decisions, statutes, administrative actions

and scholarly articles bearing directly on

the asserted reporters’ privilege.............. 42

E. Application of the asserted privilege to

the facts of No. 70-57 and companion

cases ........................................................ 50

F. Questions left open .................................. 51

IV. Before a compelling and overriding national

or state interest calling for disclosure of a

reporter’s confidence can ever be said to exist,

the government must show, at a minimum that

the violation of law which has probably occurred

of which the reporter has specifically relevant

knowledge is a major crim e.............................. 55

V. Where a reporter is properly protected by court

order for disclosure of any confidential informa

tion, and there is no showing that his appearance

before a grand jury would nevertheless serve a

compelling purpose, he need not appear............ 64

Conclusion...................................................................... 69

Ill

TABLE OF CASES

PAGE

A Quantity of Books v. Kansas, 378 U. S. 205 (1964) 40

Adams v. Associated Press, 46 F. R. D. 439 (S. D.

Tex. 1969) ........................................... S3

Adams v. Tanner, 244 U. S. 590 (1 9 1 7 ).................... 17

Aguilar v. Texas, 378 U. S. 108 (1 9 6 4 )................ .. . 32

Air Transport Association v. Professional Air Traffic

Controllers Organisation, D. C. E. D. N. Y. Nos.

70-C-400-410, April 6, 1970 ...................................... 43

Alderman v. United States, 394 U. S. 165 (1969) . . 55

Alioto V. Cowles Communications, Inc., N. D. Cal.,

C. A. 52150, December 4, 1969 ................................ 43

Application of Certain Chinese Family B. & D. Ass’ns,

19 F. R. D. 97 (N. D. Cal. 1956) ........................ 67

Aptheker v. Secretary of State, 378 U. S. 500

(1964) .......................................................................15,36

Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U. S. 360 (1964) .................. 36

Baker v. United States, 430 F. 2d 499 (D. C. Cir.

1970) , cert, denied, 400 U. S. 965 (1970) ......... 55

Bantam Books, Inc. v. Sullivan, 372 U. S. 58 (1963) .39, 40

Barenblatt v. United States, 360 U. S. 109 (1959) . .35, 36

Barr v. Matteo, 360 U. S. 564 (1959) ......................31, 40

Barrows v. lackwn, 346 U. S. 249 (1953) .............. 15

Bates V. Little Rock, 361 U. S. 516 (1960) .................30, 36,

37, 38, 62

Blackmer v. United States, 284 U. S. 421 (1932) . . . . 30

Blair V. United States, 250 U. S. 273 (1919) ..........30, 33

BlauY. United States, ZAO \J. S. 159 (1 9 5 0 ).............. 31

Blount V. Rissi, 400 U. S. 410 (1971) ............................... 40

Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U. S. 444 (1969) ........... 61

Bransburg v. Hayes, 461 S. W. 2d 345 (Ky. 1970) . . 1 , 6

Bransburg v. Meigs, # W-29-71 (unreported) (Ky.

1971) ......................................................................... 6

Bratton v. United States, 73 F. 2d 795 (10th Cir.

19341 58

IV

PAGE

Bryant v. Zimmerman, 278 U. S. 63 (1928) .............. 30

Burdick v. United States, 236 U. S. 79 (1915) ........ 11

Burns Baking Co. v. Bryan, 264 U. S. 504 (1924) . . . 17

Carl Zeiss Stiftung v. V. E. B. Carl Zeiss, Jena, 40

F. R. D. 318 (Dist. Cal. 1966), ajf’d sub. nom.

V. E. B. Carl Zeiss, Jena v. Clark, 384 F. 2d 979

(D. C. Cir. 1967) .................................................... 67

Cramp v. Board of Public Instruction, 368 U. S. 278

(1961) .................................................................... 27,36

Cur do V. United States, 354 U. S.118 (1 9 5 7 ).......... 31

Curtin V. United States,236\J. S. 96 (1 9 1 5 ).............. 11

Data Processing Service v. Camp, 397 U. S. 1 SO (1970) 1S

DeGregory v. New Hampshire Attorney General 383

U. S. 825 (1966) ............................................36,37,38

DeJonge v. Oregon, 299 U. S. 353 (1 9 3 7 ).................. 38

Dennis v. United States, 341 U. S. 494 (1951) . . . .61, 62

Dorfman v. Meissner, 430 F. 2d 558 (7th Cir. 1970) . . 33

Elfbrandt v. Russell, 384 U. S. 11 (1966) ..............27, 36

Estes V. Texas, 381 U. S. 532 (1965) ................30, 33, 36

Blast V. Cohen, 392 U. S. 83 (1 9 6 8 )............................ 15

Freedman v. Maryland, 380 U. S. 51 (1 9 6 5 ).............. 40

F. T. C. V. American Tobacco Co., 264 U. S. 298

(1924) ....................................................................67,68

Garland v. Torre, 259 F. 2d 545 (2d Cir. 1958), cert.

denied, 358 U. S. 910 (1958) .................. .23, 46,47, 51

Garner V. Louisiana, . S. 157 (1 9 6 1 )................ 41

Garrison v. Louisiana, 379 U. S. 64 (1964) ............14, 15

Gibson v. Florida Legislative Investigation Committee

372 U. S. 539 (1963) ................) ...................36,37,38

Giordano v. United States, 394 U. S. 310 (1969) . . . . 55

Greene v. McElroy, 360 U. S. 474 (1959) ................ 35

Griswold Y. Connecticut, 381 U. S. 479 (1965) ........ 15

Grosjean v. American Press Co., 297 U. S. 233 (1936) 24

Halpern v. United States, 258 F. 2d 36 (2d Cir. 1958) 55

Hawkins v. United States, 358 U. S. 74 (1 9 5 8 )........ 31

V

PAGE

Hennessy v. Wright [1888] 24 Q. B. D. 445 (C. A.) 49

Hickman v. Taylor, 329 U. S. 495 (1947) ................ 31

Illinois V. Tomashevsky, Cook County Court, Criminal

Division, Indictment No. 69-3358-59, April 7, 1970 43

In Re Goodfaders Appeal, 45 Hawaii 317, 367 P. 2d

472 (1961) .......... ................................................... 44

In Re Grand Jury, Petition of John Doe, 315 F. Supp.

681 (E. D. Md. 1970) .............................................. 43

Jn Re Grand Jury Investigation, 317 F. Supp. 792

(E. D. Pa. 1970) ...................................................... 57

In Re Grand Jury Witnesses, 322 F. Supp. 573 (N. D.

Calif. 1970) .............................................................. 53

In Re Taylor, 412 P. 32, 193 A. 2d 181 (1963) . . . . 44, 48

In Re Zuckert, 28 F. R. D. 29 (D. C. 1961), aff’d in

part sub nom. Machin v. Zuchert, 316 F. 2d 336

(D. C. Cir. 1963). cert, denied 375 U. S. 896 ........ 67

In the Matter of Paul Pappas, 266 NE 2d 297 (Mass.

1970) .................................................................... 1,6,45

lenness v. Forison, 403 U. S. 431 (1971) .................. 52

Keiffe v. LaSalle Realty Co., 163 La. 824, 112 So. 799

(1927) ...................................................................... 67

Kent V. Dulles, 357 U. S. 116 (1 9 5 8 ) ................................ 15, 16

Keyishian v. Board of Regents, 385 U. S. 589 (1967) 36

Lament v. Postmaster General, 381 U. S. 301 (1965) 39

Law Students Civil Rights Research Coimcil v.

„ TVadmond, 401 U. S. 154 (1971) ............................ 27

Levin v. Marshall, 317 F. Supp. 169 (D. Md. 1970) . . 50

Levinson v. Attorney General, 321 F. Supp. 984 (E. D.

Pa. 1970) ........■........................................................ 31

Licata v. United States, 429 F. 2d 1177 (9th Cir.

1970) .......................................................................... 57

Los Angeles Free Press, Inc. v. Los Angeles, 9 Cal.

App. 3d 448 (1970) ................................................ 52

Lyndv. Rusk, 389 F. 2d 940 (D. C. Cir. 1 967 )........ 15

Machin v. Zuchert, 316 F. 2d 336 (D. C. Cir. 1963),

cert, denied, 375 U. S. 896 (1963) ......................... 55

Maddox v. Wright, 103 F. Supp. 400 (D. C. 1952) . . 67

VI

PAGE

Mallory v. United States, 354 U. S. 449 (1957) . . . . 41

Malloy V. Hogan, 378 U. S. 1 (1 9 6 4 )........................ 3.1

Marcus w. Search Warrant, 367 U. S. 717 (1961) . . . 40

Martin Y. Struthers, 319 U. S. 141 (1943) .............. 63

McCray v. Illinois, 386 U. S. 300 (1967) .................. 32

McGuiness v. Attorney General, 63 Commw. L. R. 37

(Austl. 1940) ............................................................ 49

McNabh V. United States, 318 U. S. 332 (1943) ! . 41

Mills V. Alabama, 384 U. S. 214 (1 9 6 6 )...................... 60

Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U. S. 436 (1 9 6 6 )................ 41

Monitor Patriot Co. v. Roy, 401 U. S. 265 (1971) . . . 30

N. A. A. C. P. V. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 (1958)

30, 36, 37, 38, 46, 63

N. A. A. C. P. V. Button, 371 U. S. 415 (1963) . . . .36, 63

Near v. Minnesota, 283 U. S. 697 (1931) .................. 37

New York Times v. Sullivan, 376 U. S. 254 (1964)

15, 28, 30,31,41,43, 52

Overly v. Hall-Neil Furnace Co., 12 F. R. D. 112

(N. D. Ohio 1951).................................................... 67

Palermo v. United States, 360 U. S. 343 (1959) . . . . 55

Peoplê V. Dohrn, Cook County, Circuit Court, Criminal

Division, Indictment No. 69-3808, Decision on

Motion to Quash Subpoenas, May 20, 1970 ............ 43

People V. Rios, Calif. Super. Ct. No. 75129, July 15,

1970 ............................................................................ 43

Piccirillo V. New York, 400 U. S. 548 (1 9 7 1 )............ 57

Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U. S. 510 (1925 )___ IS

Quinn v. United States, 349 U. S. 155 (1 9 5 5 ).......... 31

Red Lion Broadcasting Co. v. F. C. C., 395 U. S. 367

(1969) 14^15

Rideau v. Louisiana, 373 U. S. 723 (1963) .............. 30

Rosenbloom v. Metromedia, Inc., 403 U. S. 29 (1971) 28

Roviaro v. United States, 353 U. S. 53 (1 9 5 7 )___32,67

Schneider v. State, 308 U. S. 147 (1938) ..........30, 62, 63

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U. S. 479 (1 9 6 0 )..................27, 33

V ll

PAGE

Sheppard v. Maxwell, 384 U. S. 333 (1 9 6 6 )............30, 33

Sherbert Y. Verner, 374 U. S. 398 (1 9 6 3 ).................. 36

Silverthorne Lumber Co. v. United States, 251 U. S.

385 (1920) ................................................................ 31

Smith V. Illinois, 390 U. S. 129 (1 9 6 8 )...................... 32

State V. Buchanan, 250 Ore. 244, 436 P. 2d 729 (1968) 44

State V. Knops, 183 N. W. 2d 93 (Sup. Ct. Wis.

1971).........................................................................44,63

Szueesv v. New Hampshire, 354 U. S. 234 (1957) . . . 27,

38,41,45

Taglianetti v. United States, 394 U. S. 316 (1969) . . 55

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516 (1 9 4 5 ).................... 36

Truax v. Raich, 239 U. S. 33 (1 9 1 5 ).......................... 15

United States v. Clay, 430 F. 2d 165 (5th Cir. 1970),

rev’d on other grounds, sub. nom. Clay v. United

States, 403 U. S‘ 698 (1 9 7 1 )...................... 55

United States v. Harris, 403 U. S. 573 (1 9 7 1 ).......... 32

United States v. Jackson, 384 F. 2d 825 (3rd Cir.

1967) .......................................................................... 55

United States v. Persico, 349 F. 2d 6 (2d Cir. 1965) 55

United States v. Reynolds, 345 U. S. 1 (1 953 )..........32, 67

United States v. Robel, 389 U. S. 258 (1 9 6 7 )............ 36

United States v. Rumely, 345 U. S. 41 (1953) . . . 34, 35, 38

United States v. Schine, 126 F. Supp. 464 (W. D. N. Y.

1954) ......................................................................... 67

United States v. Schipani, 362 F. 2d 825 (2d Cir.

1966), cert, denied, 385 U. S. 934 (1 9 6 6 )................... 55

United States v. Thirty-Seven Photographs, 402 U. S.

363 (1971) ..........■'.................................. ' ................ 40

United States Y. Ventresca, 380 U. S. 102 (1965) . . . . 32

Watkins v. United States, 354 U. S. 178 (1957) . . . . 35, 41

Wellford V. Hardin, 315 F. Supp. 175 (D. Md. 1970) . 55

Westinghouse Corp. v. City of Burlington, 351 F. 2d

762 (D. C. Cir. 1965)......................' ........................ 67

Whitehill V. Elkins, 389 U. S. 54 (1967)...................... 36

Whitney v. California, 274 U. S. 357 (1 9 2 7 ).............. 61

Williams v. Rhodes, 393 U. S. 23 (1968) .................. 52

Zemel v. Rusk, 381 U. S. 1 (1965) ............................ 15

vm

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS AND

UNITED STATES STATUTES

PAGE

United States Constitution, First Amendment ..2 , 23 24,

26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 34, 35, 38, 42,

44, 46,48,49, 55, 57, 58,61,63, 64,67

United States Constitution, Fourth Amendment . . . 31

United States Constitution, Fifth Amendment........31, 57

United States Constitution, Fourteenth Amendment . .2,

29,39

18 U. S. C. § 2514 ......................................................54, 57

28 U. S. C. § 1254(1) ................................................ 2

Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, Rule 17(c), 28

United States Code .................................................. 65

STATE STATUTES

Ala. Code Recompiled Tit. 7, § 370 (1 9 6 0 ).................. 47

Alaska Stat. § 09.25.150 (1967, 1970 Cum. Supp.) . . 47

Ariz. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 12-2237 (1969 S u p p .) .......... 47

Ark. Stat. Ann. §43-917 (1964) ................................ 47

Cal. Evid. Code Ann. § 1070 (West 1966).................. 47

Ind. Ann. Stat. § 2-1733 (1 9 6 8 ).................................. 47

Ky. Rev. Stat. § 421.100 (1 9 6 9 ).................................. 47

La. Rev. Stat. § 45:1451-54 (1970 Cum. Supp.) . . . . 47

Md. Ann. Code Art. 35, § 2 (1 9 7 1 )............................ 47

Mich. Stat. Ann. § 28.945(1) (1954) ........................ 47

Mont. Rev. Codes Ann. Tit. 93, ch. 601-2 (1964) . . . 47

Nev. Rev. Stat. § 48.087 (1 9 6 9 ).................................. 47

N. J. Stat. Ann. Tit. 2A, ch. 84A, § 21, 29 (Supp.

1969) .......................................................................... 47

N. J. Stat. Ann. Tit. 2A, ch. 9 7 -2 ................................ 58

N. M. Stat. Ann. § 20-1-12.1 (1953, 1967 Rev.) . . . . 47

N. Y. Civ. Rights Law § 79-h (McKinney 1970) . . . . 47

Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 2739.12 (1 9 5 3 )...................... 47

Pa. Stat. Ann. Tit. 28, § 330 (1958, 1970 Cum. Supp.) 47

IX

FOREIGN STATUTES

PAGE

Austria

Civil Law Statute of Austria, Article 321, Code 5 49

Federal Law of Austria of 1922, Paragraph 45 . . 49

Finland

Oikendenkaymiskaari, Chapter 17, Article XXIV. . 48

France

Decret du 7 Decembre 1960, Article 5 .................... 49

Germany

Baden - Wurttenberg - Landespressegesetz - 1952

(Bundesgesetzbl. I. S. 177) § 66 Abs. 2 des Ge-

setzes uber Ordnungswidrigkeiten...................... 49

Rundfunk §§ 4 bis 6, 11, 21 Nr. 1 § 22 Abs. 1 Nr.

3 und Abs. 2 bis ^ § § 22 und 24 fur Horfunk

und Fernsehen entrsprechend.............................. 49

Strassbare-Verletzung des Pressegesetzes, § 15 Abs.

1 [Beschl. des B Verrs G vom. 4. 6. 1957, BGBL.

I. S. 1253] ............................................................ 49

Verwaltungsgerichtsordnung, Article 98 (German

Administrative Courts Procedure) .................... 49

Zeugnisverweigerungsrecht — §§22, 23 eingefiigt

durch Ges. vom. 22.2 1966 [GVBL. S. 31] . . . . 49

Zivilprozessordnung, para. 383 and 384 (code of

German Civil Procedure) .................................... 49

Philippines

Republic of the Philippines Act (1 9 4 6 ).................. 49

Sweden

Freedom of the Press Act of April 15, 1949 ........ 48

X

LAW REVIEWS

PAGE

Beaver, The Newsman’s Code, The Claim of Privilege

and Everyman’s Right to Evidence, 47 Ore. L. R ev.

243 (1968) ................................................................ 44

Brennan, The Supreme Court and the Meiklejohn In

terpretation of the First Amendment, 79 H a r v . L.

Rev. 1 (1965) ............................................................... 14

Carter, The Journalist, His Informant and Testi

monial Privilege, 35 N. Y. U. L. R ev. 1111 (1960) 44

D’Alemberte, Journalists Under the Axe: Protection

of Confidential Sources of Information, 6 H arv. T-

Legis. 307 (1969) .................................................. .'. 44

Guest & Stanzler, The Constitutional Argument for

Newsmen Concealing Their Sources, 64 NW U.

L. R ev. 18 (1969) .................................................. 44

Hall and Jones, Pappas and Caldwell, The Newsmen’s

Privilege— Two Judicial Views, 56 Mass. L. Q.

155 (1971) .............................................................. 43

Kadish, Methodology and Criteria in Due Process Ad

judication— A Survey and Criticism, 66 Y ale I., J.

319 (1957) ...................................................................20

Karst, Legislative Facts in Constitutional Litigation,

1960 Su p . Ct . R ev. 75 ...........................................17,61

Meiklejohn, The First Amendment Is an Absolute,

1961 S u p . Ct . R ev. 245 ......................................14, 16

Nelson, The Newsmen’s Prwilege Against Disclosure

of Confidential Soiirces and Information, 24 Vand.

L. R ev. 667 (1971) .................................................. 43

Nutting, Freedom of Silence: Constitutional Protec

tion Against Governmental Intrusion in Political

Affairs, 47 M ic h . L. R ev. 181 (1 9 4 8 ).................... 32

Semeta, Journalist’s Testimonial Privilege, 9 Cleve.-

Mar. L. Rev. 311 (1960) ........................................... 44

XI

PAGE

Comment, Constitutional Protection for the Newsman’s

Work Product, 6 H arv. Civ . R ights-Civ . L ib . L.

Rev. 119 (1970) ........................................................ 43,52

Comment, The Newsman’s Privilege: Government In

vestigations, Criminal Prosecutions and Private Liti

gation, 58 Ca lif . L. Rev. 1198 (1970) ............... 43, 53

Comment, The Newsman’s Privilege: Protection of

Confidential Sources of Information Against Gov

ernment Subpoenas, 15 St. L ouis U niv . L. J. 181

(1970) ....................................... 43

Comment, The Newsmans Privilege: Protection of

Confidential Associations and Private Communica

tions, 4 J. L. R eform 85 (1971) .............................. 43

Comment, 46 Ore. L. R ev. 99 (1966) ........................ 44

Comment, 11 Stan . L. R ev. 541 (1959) ...................... 44

Note, Reporters and Their Sources: The Constitu

tional Right To a Confidential Relationship, 80

Ya l e L. j . 317 ( 1 9 7 0 ) .............................................. 43,53

Note, The First Amendment Overbreadth Doctrine, 83

H arv. L. Rev. 844 (1970) ......................................... 36

Note, The Grand lury as an Investigatory Body, 74

H arv. L. Rev. 590 (1961) ......................................... 54

Note, 71 CoLUM. L. Rev. 838 (1971) ....................... 43

Note, 46 N. Y. U. L. Rev. 617 ( 1 9 7 1 ) ...................... 43

Note, 32 T em p . L. Q. 432 (1959) .............................. 44

Note, 35 N eb. L. Rev. 562 (1956) ............................ 44

Note, 36 V a . L. R ev. 61 (1950) .................................. 44

Note, 49 H arv. L. R ev. 631 (1936) .......................... 17

Note, 45 Y ale L. J. 357 (1935) .................................. 44

Recent Case, 82 H arv. L. Rev. 1384 ( 1 9 6 9 ) ............... 44

Recent Decision, 61 M ic h . L. Rev. 184 ( 1 9 6 2 ) ......... 44

Recent Decision. 8 Buffalo L. Rev. 294 (1959) . . . . 44

OTHER PERIODICALS

New York Tribune, December 31, 1913...................... 11

New York Times, May 2, 1971, at 6 6 .......................... 11

Goldstein, Newsmen and Their Confidential Sources,

N e w R e p u b l i c , March 21, 1970, at 13 ..........22, 23, 27

Xll

BOOKS

PAGE

F. A llen , T h e Borderland of Cr im in a l J ustice

(1964) .............................................................................. 58, 59

D. Cater, T h e F ourth B ranch of Government

(1959) ................................................................................. 21

Z. Ch a fe e , T hree H u m an R igh ts in th e Co n sti

tu tio n OF 1787 (1956) ................................................ 16

F. S. C ha lm ers, A Gen tlem a n of t h e P ress : T h e

B iography of Colonel J o h n Bay ne M acL ean

( 1 9 6 9 ) ................................................................................... 20

F. F ran kfu rter , M r. J ustice H olmes and t h e

S u prem e Court (2nd ed., 1961) ................................ 13

P. F reund , O n U nderstanding T h e S uprem e

Court ( 1 9 5 1 ) ..................................................................... 17

H. K lurfeld , Be h in d t h e L in e s : T h e W orld of

D rew P earson ( 1 9 6 8 ) ................................................... 20

A. K rock, T h e N ew spaper— I ts M a k in g and I ts

M e a n in g ( 1 9 4 5 ) .............................................................. 20

A. K rock, M e m o ir s : S ix ty Y ears on t h e F ir in g

L in e ( 1 9 6 8 ) ........................................................................ 20

C. M acD ougall, N ewsroom P roblems and P olicies

( 1 9 6 4 ) ................................................................................... 21

J. M adison , T h e F ederalist N o. 51 ( Cooke ed. 1961) 28

N. M orris and G. H a w k in s , T h e H onest P o l it i

c ia n ’s Gu id e to Cr im e C ontrol ( 1 9 6 9 ) ................ 59

R. O ttley , T h e L onely W arrior— T h e L if e and

T im es of R obert S. A bbott (1955) .......................... 20

H. P acker , T h e L im it s of t h e Cr im in a l Sanction

( 1 9 6 8 ) ........................... 59

R. P ound, Cr im in a l J ustice in A merica (1930) . . 58

xm

PAGE

U. S chw artz, P ress L aw for O ur T im es (Inter

national Press Institute ed, 1966) ......................... 49

G. Seldes, N ever T ire of P rotesting ( 1 9 6 8 ) ......... 20

H. S herwood, T h e J ournalistic I nterview (1969) 21

L. S nyder and R. M orris, A T reasury of Great

R eporting (1962) .................................................. 20

2 J. St epfie n , H istory of t h e Cr im in a l L aw of

E ngland (1883) ...................................................... 58

C. L. S ulzberger, A L ong R ow of Candles, M e m

oirs and D ia ries , 1934-54 (1969) ....................... 21

MISCEIXANEOUS

Guidelines of the Attorney General on Press Sub

poenas, 39 U. S. L. W. 2111 (August 10, 1970)

12, 13, 23, 46,49, 50, 53

Committee o'n Rules of Practice and Procedure of the

Judicial Conference of the United States, Revised

Draft of Proposed Rules of Evidence for the United

States Courts and Magistrates, Rules 503, 504, 506,

507, 510(c)(3) (1971) ....................................31,32, 55

117 Cong R ec 6639 (daily ed. July 13, 1971) .......... 27

S. 3552, 91st Cong., 2d Sess. (1 9 7 0 ).......................... 48

H. R. 16328, 91st Cong., 2d Sess. (1 9 7 0 ).................. 48

H. R. 16704, 91st Cong., 2d Sess. (1 9 7 0 ).................. 48

I n the

(Burnt of ^tate

O ctober T erm , 1971

No. 70-57

U n ited States of A m erica ,

V.

E arl Caldwell,

Petitioner,

Respondent.

O n W rit of Certiorari to th e U nited S tates

Court of A ppeals for th e N in t h C ir c u it

BRIEF OF THE NEW YORK TIMES COMPANY, INC.,

NATIONAL BROADCASTING COMPANY, INC., CO

LUMBIA BROADCASTING SYSTEM, INC., AMERICAN

BROADCASTING COMPANIES, INC., CHICAGO SUN-

TIMES, CHICAGO DAILY NEWS, ASSOCIATED PRESS

MANAGING EDITORS ASSOCIATION, ASSOCIATED

PRESS BROADCASTERS’ ASSOCIATION AND ASSO

CIATION OF AMERICAN PUBLISHERS INC. AS

AMICI CURIAE

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the Court of Appeals (A. 114-130) is

reported at 434 F. 2d 1081. The opinion of the District

Court (A. 91-93) is reported at 311 F. Supp. 358. Opinions

of the highest courts of Massachusetts and Kentucicy in the

companion cases. No. 70-85, Branshurg v. Hayes, and No.

70-94, In the Matter of Paul Pappas, may be found respec

tively at 461 S. W. 2d 345, and 266 N. E. 2d 297.

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the Court of Appeals (A. 131) was

entered on November 16, 1970. The petition of the United

States for a writ of certiorari was filed on December 16,

1970, and granted on May 3, 1971 (A. 132). The juris

diction of this Court rests on 28 U.S.C. 1254 (1).

CONSENT OF THE PARTIES

Both the United States and Earl Caldwell, by their

attorneys, have given their consent to the filing of this

brief, and their letters of consent are on file with the Clerk

of this Court.

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether a reporter for a news medium who is properly

protected by a court order from disclosing unpublished in

formation obtained in confidence from a news source should

be required to appear before a grand jury investigating

that news source.

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS

The First Amendment to the United States Constitu

tion provides in pertinent part:

“Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the free

dom of speech, or of the press. . . .”

The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Con

stitution provides in pertinent part:

“ . . . nor shall any State deprive any person of life,

liberty, or property without due process of law___”

INTEREST OF THE AMICI

The New York Times Company, Inc. publishes The

New York Times (“The Times”) and employs Earl Cald-

well, the respondent, and others as reporters. As a pub

lisher of news and as a servant of the public’s First Amend

ment right to freedom of the press, The Times stands ready

to defend the integrity of its news stories. At the same

time, it is in the interest of The Times, as Mr. Caldwell’s

employer, and as the employer of other reporters, that its

reporters be able freely to gather news—that they be free

from governmental interference or inhibition tending to de

stroy their ability to pursue their news gathering and news

reporting activities.

National Broadcasting Company, Inc. (“NBC” ), Co

lumbia Broadcasting System, Inc. ( “CBS”) and American

Broadcasting Companies, Inc. (“ABC”) are each inti

mately involved in the news gathering process. Each owns

and operates television and radio stations. The news divi

sion of each employs a large number of professional jour

nalists to gather, report and analyze news relating to issues

of public interest and concern. Each also produces and

broadcasts in depth news programs which probe the public

issues of the day. In recent years, the amici have them

selves been served with numerous subpoenas (see Appen

dix). The reversal of the decision below in this action and

the affirmance of the decisions in the accompanying actions

would, the networks believe, perilously endanger their

sources of information and thus diminish their capacity

to present the news and, far more importantly, the right of

the public to see and hear it.

The Chicago Sun-Times and Chicago Daily News are

published in a metropolitan urban area. They endeavor to

make available maximum information to the public so that

the political and social process may function effectively.

In order to provide this information, it is essential to main

tain the confidence of all kinds of groups involved in urban

social change. These newspapers are responsible before

the law for what they print; but if their confidences are to

be disclosed, their abilities to gather and publish news would

be gravely impaired.

The Associated Press Managing Editors’ Association

is an association of the managing editors of newspapers

throughout the United States, large and small, which are

members of The Associated Press; and The Associated

Press Broadcasters’ Association is an association of repre

sentatives of the many radio and television stations which

are members of The Associated Press. Both Associations

and their members are deeply concerned at the threat to a

free press posed by the issuance of subpoenas to newsmen

on their various staffs. They are convinced that if freedom

of the press is to survive in its present form, this Court

must assure the newsmen constitutionally guaranteed pro

tection from such threats, and, to that end, have determined

to join in the filing of this brief.

The Association of American Publishers, Inc., is a

trade association organized under the laws of New York

and composed of publishers of general books, textbooks

and other educational materials. It is estimated that its 262

individual member companies, which include many univer

sity presses and publishers of religious books, publish

approximately 85% of all such books and materials pro

duced in the United States. The members of the Association

publish substantial quantities of material written and pre

pared by reporters and other authors who must guarantee

the confidentiality of their sources. Accordingly, the As

sociation is interested in the scope of protection afforded by

the First Amendment to the United States Constitution

for material which is obtained in confidence and in the

freedom from government interference with the processes

of publishing.

STATEMENT

The facts and lower-court proceedings are detailed in

the briefs of the parties, and we restrict ourselves here to

a summary statement.

Respondent Caldwell is a reporter employed by The

Times. He is stationed in San Francisco, and has written

a number of articles on the Black Panther Party and its

leadership. Among other things, he has reported the views

of Panther Party leaders, including statements made to

him. After an earlier subpoena duces tecum, ordering pro

duction of materials concerning aims, purposes and activi

ties of the Black Panther Party, had been withdrawn, the

Government on March 16, 1970 served a subpoena ad testi

ficandum on Caldwell, calling on him to appear before a

grand jury in San Francisco. 311 F. Supp. at 359. On mo

tion of Caldwell and The Times to quash the subpoena or,

alternatively, to issue a protective order, the District Court

issued such an order, but denied the motion to quash. The

District Court’s order protected Caldwell against being re

quired to “answer questions concerning statements made to

him or information given to him by members of the Black

Panther Party unless such statements or information were

given to him for publication or public disclosure. . . .” Id.

at 361. Caldwell was also protected from having to reveal

confidential associations or sources, but the court stated

that the order was open to modification should the govern

ment show “a compelling and overriding national interest

in requiring Mr. Caldwell’s testimony which cannot be

served by any alternative means. . . .” Id. at 362.

Ultimately, after further proceedings made necessary

by the expiration of the term of one grand jury and the

impanelling of a new one, Caldwell was held in civil con

tempt for refusing to appear. On appeal by Caldwell, the

Government having taken no appeal from the protective

order, the Court of Appeals reversed the judgment of con

tempt. 434 F. 2nd at 1090.

In No. 70-85, Bransburg v. Hayes^ a companion case,

the reporter, Branzburg, is employed by the Louisville,

Kentucky, Courier-Journal. After much investigation in

Louisville and elsewhere in Kentucky, Branzburg wrote

and had published articles telling of a hashish-production

enterprise conducted by two young residents of Louisville,

and of traffic in marijuana and use of this and other drugs

in Franklin County, Kentucky. Summoned by two sepa

rate state grand juries, Branzburg refused to disclose the

identities of his confidential informants. In two separate

proceedings, Branzburg was ordered to appear. In one

{Hayes), in which a Kentucky statute protecting reporters

from having to disclose sources of information was held

inapplicable, he was ordered also to answer. In the other

(Meigs), in which a protective order was issued pursuant

to the statute, he was merely ordered to appear. The Ken

tucky Court of Appeals affirmed both rulings, 461 S. W.

2d 345 [Hayes] and 9^W-29-7l (unreported) [Meigs],

On January 26, 1971, Mr. Justice Stewart issued a stay.

In No. 70-94, In the Matter of Paul Pappas, another

companion case, Pappas, a reporter-photographer for

W TEV Television, an ABC affiliate in New Bedford,

Massachusetts, was given permission by members of the

Black Panther Party to spend the night in a building in New

Bedford occupied by them, on condition that he report an

expected police raid, but keep anything else he might see

or hear during his sojourn in confidence. No police raid

materialized and Pappas broadcast no report. Nearly two

months later, having been called before the Bristol County

grand jury, Pappas appeared, but refused to answer ques

tions about what he had seen or heard during his night in

the Black Panther building, although he did answer other

questions. 266 N. E. 2d at 298. The Superior Court ordered

him to answer, and the Supreme Judicial Court affirmed.

Id. at 297. On February 4, 1971, Mr. Justice Brennan

issued a stay.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Narrowly stated, the question in No. 70-57, the Cald

well case, concerns the need for the appearance before a

grand jury of a reporter protected by court order from

revealing information obtained in confidence. But in decid

ing this question, this Court, like the Court of Appeals for

the Ninth Circuit, can scarcely avoid passing also on the

considerations which led to the issuance of the protective

order in the Caldwell case, since the question is not an

abstract one, but rather whether a reporter so protected,

and properly so protected, must appear. The underlying

issue of the protection required against compelled disclosure

of a reporter’s confidential sources and information is in

any event presented also by the companion cases.

The right of the public to be informed by print and

electronic media, which is deeply rooted in the First Amend

ment, coincides with a reporter’s right of access to news

sources unimpeded by government. That right is abridged,

in violation of the First and Fourteenth Amendments, if

state or federal governments can commonly compel re

porters to identify confidential sources, or divulge other

information obtained in confidence. It is a plain fact that

if a reporter must disclose confidences to government

investigators, his access to news, and therefore the public’s,

will be severely constricted, and in many circumstances shut

off. The First Amendment demands, therefore, that the

reporter be protected. The standard of protection can be

defined by objective criteria, and made self-limiting in

practice.

A reporter cannot, consistently with the Constitution,

be made to divulge confidences to a governmental investi

gative body unless three minimal tests have all been met:

A. The government must clearly show that there is probable

cause to believe that the reporter possesses information

which is specifically relevant to a specific probable violation

of law. B. The government must clearly show that the

8

information it seeks cannot be obtained by alternative

means, which is to say, from sources other than the

reporter. C. The government must clearly demonstrate a

compelling and overriding interest in the information.

The duty to give evidence or appear before a grand jury

is not absolute. It yields in many contexts, and must yield

here to the First Amendment, just as equally significant,

though not compelling, governmental interests yield to the

First Amendment in analogous circumstances. The nearest

analogies are legislative investigation cases in which special

procedural requirements were laid down, cases resting on

the overbreadth doctrine, and decisions requiring the show

ing of a compelling governmental interest when measures

are taken impinging on the First Amendment.

In no case now before this Court—not in No. 70-57,

and not in the Branzbiirg or Pappas cases—has the govern

ment met both of the first two tests set out above. It is not

necessary for purposes of the decision of these cases, there

fore, to determine the exact manner in which the third of

our proposed tests is to be applied. That third test should

receive recognition, however. Hence it should be posited

at a minimum that with respect to a category of crimes

that cannot be deemed “major,” as for example crimes

variously characterized as “victimless,” “regulatory,” and

“sumptuary,” it is not enough for the government to have

satisfied the first two of our proposed tests. With respect

to such crimes at least, a reporter should have the right not

to disclose to a governmental investigative body informa

tion obtained in confidence from a news source, or the

identity of that source.

Where, by application of the three tests we propose, or

under other applicable law, a reporter is protected from

having to disclose confidential information, he should not

be forced to go through the “barren performance,” as the

Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit called it in No.

70-57, 434 F. 2d at 1089, of appearing before a grand

jury anyway.

ARGUMENT

I

INTRODUCTION

Strictly speaking, District Judge Zirpoli’s protective

order is not directly at issue in this Court, since the Gov

ernment did not appeal from it. For the purposes of its

own review, however, the Court of Appeals for the Ninth

Circuit stated:

“While the United States has not appealed from

the grant of privilege by the District Court (which

it opposed below) and the propriety of that grant

is thus not directly involved here, appellant’s con

tentions here rest upon the same First Amendment

foundation as did the protective order granted be

low. Thus, before we can decide whether the First

Amendment requires more than a protective order

delimiting the scope of interrogation, we must iirst

decide whether it requires any privilege at all.” 434

F. 2d at 1083.

The same is true in the present posture of the case.

The precise holding of the Court of Appeals was as

follows:

“Appellant asserted in affidavit that there is noth

ing to which he could testify (be}mnd that which

he has already made public and for which, there

fore, his appearance is unneccessary) that is not pro

tected by the District Court’s order. If this is true

—and the Government apparently has not believed

it necessary to dispute it—appellant’s response to

the subpoena would be a barren performance—one

of no benefit to the Grand Jury. To destrov appel

lant’s capacity as newsgatherer for such a return

hardly makes sense. Since the cost to the public of

10

excusing his attendance is so slight, it may be said

that there is here no public interest of real substance

in competition with the First Amendment freedoms

that are jeopardized.

“If any competing public interest is ever to arise

in a case such as this (where First Amendment

liberties are threatened by mere appearance at a

Grand Jury investigation) it will be on an occasion

in which the witness, armed with his privilege, can

still serve a useful purpose before the Grand Jury.

Considering the scope of the privilege embodied in

the protective order, these occasions would seem to

be unusual. It is not asking too much of the Gov

ernment to show that such an occasion is presented

here.

“In light of these considerations we hold that

where it has been shown that the public’s First

Amendment right to be informed would be jeopar

dized by requiring a journalist to submit to secret

Grand Jury interrogation, the Government must re

spond by demonstrating a compelling need for the

witness’s presence before judicial process properly

can issue to require attendance.” 434 F. 2d at 1089,

The question presented in this Court is the correctness

of the holding of the Court of Appeals. It is whether a

reporter who is properly protected from disclosing confi

dential information should be required to attend before a

Grand Jury. District Judge Zirpoli’s protective order and

the considerations on which it was based are relevant, there

fore, and we shall discuss them. The question of the neces

sity of such a protective order is squarely presented by No.

70-85, Bransburg v. Hayes, and No. 70-94, In the Matter

of Paul Pappas.

The issue of a reporter’s right to withhold from govern

ment investigations information obtained in confidence is

11

not altogether a novel one in our law, although it has long

lain relatively dormant, and is an issue of first impression

in this Court/ It has acquired urgency in the last few years,

and drawn a great deal of public and official attention. Its

seriousness has been acknowledged by the President of the

United States and by the Attorney General. Both have ex

pressed the opinion that a reporter’s confidences ought

generally to be respected.

Answering, at a press conference on May 1, 1971, a

question that ranged beyond the issue of a reporter’s con

fidences, the President nevertheless addressed himself

specifically to an aspect of this issue. The President used

the example of “subpoenaing the notes of reporters,” and

said that ‘ when you go to the question of Government

action which requires the revealing of sources, then I take

a very jaundiced view of that kind of action. Unless,

unless it is strictly-—and this would be a very narrow area—

strictly in the area where there was a major crime had

been committed and where the subpoenaing of the notes

had to do with information dealing directly with that

crime.” See New York Times, May 2, 1971, at 66.

'^Biirdick V. United States, 236 U. ,S. 79 (1915), and Curtin v.

United States, 236 U. S. 96 (1915), concerned a front-page story in

the New York Tribune of December 31, 1913, reporting that Lucius

N. Littauer, a wealthy former Congressman, and Mrs. W. Ellis Corey,

wife of a former president of the U. S. Steel Corporation, were being

mvestigated on charges of having smuggled jewelry into the country.

Burdick, the city editor of the Tribune, and Curtin, its ship-news

reporter, were summoned before a grand jury investigating customs

irauds and asked to divulge the source of their information. Both

refused to answer, invoking their rights under the Fifth Amendment

not to be required to incriminate themselves. Thereupon the President

issued pardons to both men for any offenses they might have com

mitted in connection with the Littauer-Corey story, thus in effect

attempting to irnmunize them. Both men refused the pardons and

persisted in declining to answer on Fifth Amendment grounds. They

were held in contempt,^ but this Court reversed the contempt judg

ments, holding that unlike an immunity statute, a pardon carried an

imputation of guilt, and could not be valid unless accepted. Prosecu-

tions against Mr. Littauer and Mrs. Corey were, incidentally, suc

cessfully concluded.

12

Nine months before the President spoke, on August

10, 1970, the Attorney General had issued Guidelines, 39

U. S. L. W. 2111 (1970), see Brief for the United States,

No. 70-57, App. A., pp. 49-51, which are characterized in

the petition for certiorari filed by the United States in the

Caldwell case as indicating that “the Department of Justice,

as a matter of policy, does not seek confidential information

in the absence of an overriding need.” (p. 6) The brief

of the United States on the micrits in Caldwell, however,

states that the Guidelines establish internal procedures to

be followed within the Department of Justice, and “are not

intended to create any litigable rights in and of themselves.”

(n. 42, p. 47)

Neither the President’s remarks nor the Guidelines have

the force of law even within the federal system, let alone

throughout the country. Yet they evince most authorita

tively a developing consensus of what the law should be,

as does, we shall show, the scholarly literature. A growing

number of statutes point in a like direction. But the need

for positive, national law in the premises is great and ur

gent. The issue of a reporter’s right to withhold confidences

from government investigation is no longer dormant—-far

from it. Conditions have changed. The past experience of

the press, while the issue lay dormant, is a wholly inade

quate basis for predicting, as the amicus brief for the

United States in Nos. 70-85 and 70-94 complacently does,

that no great harm is more impending.

The volume of subpoenas served on reporters and news

media has risen tremendously in the last few years, as is

demonstrated by the Appendix to this brief. This Appendix

consists of a list of subpoenas served on two television net

works (NBC and CBS) and their wholly-owned stations

in the period from 1969 through July, 1971. The list indi

cates the nature of the investigations or cases that gave rise

to the subpoenas. We do not contend that if the Court

should decide the instant cases as we shall urge, every

13

subpoena of the kind of those listed in this Appendix

would or should be quashed. The list is intended to show

the magnitude of what reporters and the media have re

cently been faced with and may expect to continue to be

faced with. It shows also the miscellany of instances in

which subpoenas are now issued, as a first resort, to report

ers and to the news media which employ them. The typical

subpoena does not fall in the “very narrow area” of major

crimes of which, as we understand his remarks, the Presi

dent spoke. See supra, p. 11. It does not proceed from

any urgent sense that the occasion is a special one, of

overriding importance and need. Rather it has become

a matter almost of routine. There is an alarming and novel

tendency abroad, in the disapproving words of the Attorney

General’s Guidelines, supra, to use the nevcspaper or radio

and TV reporter as a “spring board for investigations,” and

to turn him into “an investigative arm of the government.”

The pressure is enormous, and grave and pervasive conse

quences will follow if the decision of the instant cases does

not ease it.

II.

THE RIGHT OF READERS AND VIEWERS FREELY TO

BE INFORMED BY PRINT OR ELECTRONIC NEWS MEDIA

IS ABRIDGED, IN VIOLATION OF THE FIRST AND FOUR

TEENTH AMENDMENTS, IF STATE OR FEDERAL GOVERN

MENTS CAN COMMONLY COMPEL REPORTERS FOR SUCH

MEDIA TO IDENTIFY CONFIDENTIAL SOURCES OR TO

DIVULGE INFORMATION OBTAINED IN CONFIDENCE.

A. The Constitutional Foundation of the Right

If within the firstness of the First Amendment,^ there

is a firstness also among the interests fostered by the Free

dom of Speech and of the Press Clause, then it is the

^See e.g., F. F rankfurter, Mr. J u stic e H olm es a n d t h e

Supreme Court, 74-76 (2nd ed., 1961).

14

interest in the flow of politically relevant information to

the public, and consequently in the freedom and efficacy of

the process of news gathering- by print or electronic media.

We deal here with nothing less than “the First Amendment

goal of producing an informed public capable of conducting

its own affairs. . . .” Red Lion Broadcasting Co. v. F. C. C.,

395 U. S. 367, 592 (1969). Above all else, the First

Amendment “protects the freedom of those activities of

thought and communication by which ŵe ‘govern.’ It is

concerned, not with a private right, but with a public power,

a governmental responsibility.® As this Court said, again

in Red Lion Broadcasting Co. v. F. C. C., 395 U. S. at

390 “ [T]he people as a whole retain their interest in

free speech by radio [and, of course, in free speech by tele

vision or by printed medium] and their collective right to

have the medium function consistently v/ith the ends and

purposes of the First Amendment. It is the right of the

viewers and listeners, not the right of the broadcasters,

which is paramount. . . . ‘[SJpeech concerning public affairs

is more than self-expression; it is the essence of self-

government.’ Garrison v. Louisiana, 379 U. S. 64, 74-75

(1964). See Brennan, The Supreme Court and the Meikle-

john Interpretation of the First Amendment, 79 Harv. L.

Rev. 1 (1965). It is the right of the public to receive

suitable access to social, political, esthetic, moral, and other

ideas and experiences which is crucial here. That right

may not constitutionally be abridged either by Congress or

®Meiklejohn, The First Amendment Is an Absolute, 1961 Su

p r em e Court R ev iew 245, 255. The passage goes on; ‘Tn the spe

cific language of the Constitution, the governing activities of the

people appear only in terms of casting a ballot. But in the deeper

meaning of the Constitution, voting is merely the external expression

of a wide and diverse number of activities by means of which citizens

attempt to meet the responsibilities of making judgments, which that

freedom to govern lays upon them.”

15

by the F. C. C.” Or by the executive, or by a state, or by a

grand jury, or by a court.*

As the Court’s quotation from Garrison v. Louisiana,

379 U. S. at 76-77, indicates, the conception of the First

Amendment manifested in Red Lion Broadcasting Co. v.

F. C. C., supra, also informed New York Times Co. v.

Sullivan, 376 U. S. 254 (1964), and has informed its

progeny. The “profound national commitment to the prin

ciple that debate on public issues should be uninhibited,

robust, and wide-open,” New York Times Co. v. Sullivan,

376 U. S. at 270, and a profound national commitment

to the free flow of information to news media and through

them to the public—these two commitments are twins, or

ganically joined and unseverable.

The same vital public interest in wide-open, informed

debate was at the basis of the Court’s statement in Kent

V. Dulles, 357 U. S. 116 (1958), and its holding in Aptheker

V. Secretary of State, 378 U. S. 500 (1964), that the Fifth

Amendment protects a right to travel.® The Court in Kent

V. Dulles plainly had in mind the people’s need and right

to be informed, so that “those activities of thought and

^No problem of standing arises here, any more than it did in

Red Lion Broadcasting Co. v. P. C. C., supra. The right asserted

is conceptually that of the public, and not of Caldwell, the respondent

reporter in No. 70-57, or of Branzburg or Pappas, the reporters in

Nos. 70-85 and 70-94. But it is beyond question that “the challenged

action has caused [Caldwell, Pappas and Branzburg] injury in fact,”

Data Processing Service v. Camp, 397 U. S. 150, 152 (1970), and

hence that Article III jurisdiction exists. Cf. Flast v. Cohen, 392

U. S. 83 (1968). The right of the public is “likely to be diluted or

adversely affected”, Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U. S. 479, 481

(1965), unless it is considered in such a suit as this, involving those

who exercise the right in the public’s behalf. Cf. N. A. A. C. P. v.

Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 (1958) ; Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249

(1953) ; Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U. .S. 510 (1925) ; Trua.v v.

Raich, 239 U. S. 33 (1915).

®See also Lynd v. Rusk, 389 F. 2d 940 (D. C. Cir. 1967) ; cf.

Zemel v. Rusk, 381 U. S. 1 (1965).

16

communication by which we ‘govern’ might be fostered

and enhanced. Supporting its premise, which had been

conceded by the Solicitor General, that the Fifth Amend

ment protects a right to travel, the Court quoted, at 357

U. S. 126-27, from Z. Ch a fe e , T hree H um a n R ig h ts in

THE Co n stitu tio n of 1787, 195-196 (1956): “Foreign

correspondents and lecturers on public affairs need first

hand information. Scientists and scholars gain greatly

from consultations with colleagues in other countries. Stu

dents equip themselves for more fruitful careers in the

United States by instruction in foreign universities. . . . In

many different ways direct contact with other countries

contributes to sounder decisions at home.”

The people’s right to be informed by print and elec

tronic news media is thus the central concern of the First

Amendment’s Freedom of Speech and of the Press Clause.

Our submission is that if an obligation is imposed by law

on a reporter of news to disclose the indentity of confidential

sources or divulge other confidences that come to him in

the process of news gathering, the reporter’s access to news,

and therefore the public’s access, will be severely constricted

and in some circumstances shut off. The reporter’s access

is the public’s access. He has, as a citizen, his own First

Amendment rights to self-expression, to speech and to

associational activity, but they are not in question here.

The issue here is the public’s right to know. That right is

the reporter’s by virtue of the proxy which the Freedom

of the Press Clause of the First Amendment gives to the

press on behalf of the public.

B. T h e Factual Foundation of the Right

Whether the proxy covers a case such as this, or in

other words, whether the reporter’s access to information

®Meiklejohn, The First Amendment Is an Absolute, supra, n. 3.

17

is, in the circumstances, the public’s access, and whether an

obligation imposed by law on the reporter to disclose the

identity of confidential sources and to divulge other confi

dences will constrict or shut ofif his and the public access to

news—these are questions of fact, both “adjudicative fact,” ̂

and “constitutional fact.”®

Early in his career, when he was trying to persuade his

colleagues that wise constitutional judgments must rest on

carefully and realistically built factual foundations, Justice

Brandeis wrote: “The judgment should be based upon a

consideration of relevant facts, actual or possible—E x

facto jus oritur. That ancient rule must prevail in order

that we may have a system of living law.”® A few years

later, he added: “Sometimes, if we would guide by the

light of reason, we must let our minds be bold. But, in this

case, we have merely to acquaint ourselves with the art of

bread making and the usages of the trade. . . In this

case, the Court has merely to acquaint itself with the art

of newsgathering and the usages of the trade.

The adjudicative facts were found by District Judge

Zirpoli in No. 70-57. His specific findings, which follow.

’̂ See Karst, Legislative Facts in Constitutional Litigation, 1960

S u p . Ct . R ev . 75, 77.

sSee Note, 49 H arv. L. R ev . 631, 632 (1936).

^Adams v. Tanner, 244 U. S. 590, 597, 600 (1917) (Brandeis, J.,

dissenting).

^<>Burns Baking Co. v. Bryan, 264 U. S. 504, 517, 520 (1924)

(Brandeis, J., dissenting). Justice Brandeis’ “sense of the controlling

vitality of facts . . . produced the so-called Brandeis brief at the bar

and its counterpart in his richly documented opinions on the bench.

. . . In his opinions the technique of the Brandeis brief was gener

ally employed to sustain the legislative judgment. But on occasion

the same technique, reflecting the same insatiable passion to know,

was employed to suggest that what had once been constitutional

might be questionable in the light of facts that had markedly

changed.” P. F r eu n d , On U n d ersta n d in g t h e S u pr em e Court

51 (1951).

18

were adopted by the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Cir

cuit :

“ (3) That confidential relationships of this sort are

commonly developed and maintained by professional

journalists, and are indispensable to their work of gath

ering, analyzing and publishing the news.

“ (4) That compelled disclosure of information re

ceived by a journalist within the scope of such confi

dential relationships jeopardizes those relationships and

thereby impairs the journalist’s ability to gather, ana

lyze and publish the news;

“ (5) Specifically, that in the absence of a protec

tive order by this Court delimiting the scope of in

terrogation of Earl Caldwell by the grand jury, his

appearance and examination before the jury will severely

impair and damage his confidential relationship with

members of the Black Panther Party and other mili

tants, and thereby severely impair and damage his

ability to gather, analyze and publish news concerning

them; and that it will also damage and impair the abili

ties of other reporters for The New York Times Com

pany and others to gather, analyze and publish news

concerning them. . . .” 311 F. Supp. at 361-62.

These findings are solidly grounded in affidavits from

working reporters, who testified of their own vivid knowl

edge to the crucial role played in their profession by con

fidential sources and confidential information, and to the

effect that the imposition by law of an obligation to disclose

and divulge would have. As telling as any is the affidavit

of Walter Cronkite;

“3. In doing my work, I (and those who assist me)

depend constantly on information, ideas, leads and

opinions received in confidence. Such material is es-

19

sential in digging out newsworthy facts and, equally

important, in assessing the importance and analyzing

the significance of public events. Without such ma

terials, I would be able to do little more than broadcast

press releases and public statements.

“4. The material that I obtain in privacy and on a

confidential basis is given to me on that basis because my

news sources have learned to trust me and can confide

in me without fear of exposure. In nearly every case,

their position, perhaps their very job or career, would

be in jeopardy if this were not the case.. . .” (A. 52-

53)“

Neither the “adjudicative” nor the more far-ranging

“constitutional” facts can be proved with mathematical

certainty. Constitutional adjudication is not an exact sci

ence. But the “constitutional” as well as the “adjudicative”

facts can be established to a moral if not a mathematical

certainty. It is no novelty that “lacking the possibilities

of controlled experimentation,” courts resort “to the only

^^The government in its brief here (p. 16) chooses to read the

Cronkite affidavit as showing that “ [a]s a general matter, it is not

that which is communicated to the reporter that is intended to be

withheld from publication, but only the identity of the communi

cant.” This reading is achieved by italicizing the phrase, “without fear

of exposure,” at the end of the next to last sentence quoted above.

(Brief for the United States, p. 17). Mr. Cronkite, the government

handsomely concedes, makes his point “with customary precision,”

iDUt he made it in this instance without the unintended precision

imputed to him by the italics, as the government, of course, acknowl

edges. This and other affidavits, as District Judge Zirpoli found

and as the government itself allows later on in its brief (pp. 18

et seq.), emphasize the necessity for respecting both the confidential

identity of a news source, “and other information of a confidential

nature.” (p. 19) This can be emphasized in the Cronkite affidavit

by italicizing, not the vrords the government chose to underline, but

the words with which that same next to last sentence begins: ‘‘The

material that I obtain in privacy and on a confidential basis is given

to me on that basis. . . The uses of such material are pointed out

by Mr. Cronkite ( “leads,” “opinions” ), and are discussed infra at

pp. 23 et seq.

20

empiric ground of study available~the actual conduct of

men in society ,reasonable men, whose expectations and

conduct may be taken as general, see infra pp. 24-25. The

professional literature of journalism bears ample witness

to the pervasiveness of confidential relationships between

reporters and their sources, to their importance and the

importance of safeguarding their integrity, and to the

sheer volume of news that is derived from them.

Arthur Krock, for example, has written that:

“Another attribute is peculiarly necessary for

this work: a Washington correspondent must keep

more rigidly the confidence of news sources, for it is

in confidence that much important news is acquired

which othervcise would be withheld from the public

that has a right to know it. One breach of such

faith, and that news source is closed.” (A. K rock,

T h e N ew spaper— I ts M a k in g and I ts M e a n in g

45 (1945).

The point recurs elsewhere, particularly in memoirs of

journalists, with varying illustrations. See, e.g., F. Ch a l

mers, A Gen tlem a n of t h e P r ess: T h e B iography

OF Colonel J o h n Bayne M acClean 74-75 (1969); H.

K lurfeld , Be h in d t h e L in e s : T h e W orld of D rew

P earson 50, 52-55, 142 (1968); A. K rock, M e m o ir s :

S ix ty Y ears on t h e F ir in g L in e 181, 184-85 (1968);

E. L arsen , F irst W it h T h e T r u th 22-23, 94-95 (1968) ;

R. O ttley , T h e L onely W arrior— T h e L if e and

T im es of R obert S. A bbott 143-45 (1955); G. Seldes,

N ever T ire of P rotesting 83-84 (1968); L. S nyder and

R. M orris, A T reasury of Great R eporting 180

(1962) (“The New York Times Exposes Boss Tweed”);

i^Kadish, Methodology and Criteria in Due Process Adjudica

tion—A Survey and Criticism, 66 Y a le L. J. 319, 354 (1957).

21

C. L. Sulzberger, A L ong R ow of Candles, M em

oirs AND D ia ries , 1934-54 xvi, 24, 241, 249 (1969). Books

addressed to the profession rather than emanating from it

are equally clear in emphasizing the necessity of preserv

ing the confidential relationship between reporters and their

informants. Typical of the teachings in these works is the

admonition of C. MacDougall that:

“The reporter who didn’t live up to this code [of

non-disclosure of confidential material] would find

himself without ‘pipelines,’ and his effectiveness

would be reduced greatly. Experience proves that

the person with whom the reporter ‘plays ball’ on

one occasion is likely to supply the tip which leads

to a better story on another.” (C. M acD ougall,

N ewsroom P roblems and P olicies 301 (1964).)

Or, as Hugh C. Sherwood has written:

“This brings up the one rule that can be flatly

and unequivocally stated in regard to off-the-record

interviews. Once you have agreed to interview some

one on this basis, keep your word—you will probably

never get another interview from the person if you

don’t.” (H. S herwood, T h e J ournalistic I nter

view 89 (1969)).

See, also D. Cater, T h e F ourth Branch of Govern

m en t 124-25 (1959).

The sum of it all, as the amicus brief for the Columbia

Broadcasting System in the Supreme Judicial Court of

Massachusetts in No. 70-94 pointed out, is that reporters

are able to get much indispensable information only on the

understanding that confidence may be reposed in them

because they can and will keep confidences. Such indis

pensable information comes in confidence from office

22

holders fearful of superiors, from businessmen fearful of

competitors, from informers operating at the edge of the

law who are in danger of reprisal from criminal associates,

from people afraid of the law and of the government, some

times rightly afraid, but as often from an excess of caution,

and from men in all fields anxious not to incur censure for

unorthodox or unpopular views, whether their views would

be considered unorthodox and be unpopular in the commu

nity at large, or merely in their own group or subculture.

The assurance of confidentiality elicits valuable background

information in important diplomatic and labor negotiations

and in many similar situations where disclosure would ad

versely affect the informant’s bargaining position. Public

figures of all sorts, including government officials, political

candidates, corporate officers, labor leaders, movie stars and

baseball heros, who will speak in public only in carefully

guarded words, achieve a more informative candor in pri

vate communications.

Claims to a right to withhold confidential information

“are far more credible for newsmen than they are

for the other professionals. Most disclosures are

made to an attorney because the client wants the

best possible advice and because he realizes that he

will be the loser if he withholds the raw materials

on which such advice should be predicated. The

patient tells all to his physician because he wants

to be diagnosed and treated properly. . . . The per

sons who make such communications probably know

very little about the degree to which their confi

dences may be disclosed in the future; but if they

did, the immediate interest in getting good advice

would probably prevail, the communication would

be made, and the professional relationships would

remain viable.

23

“In the case of a journalist . . . the informant

does not risk his health or liberty or fortune or soul

by withholding information. He is likely to be

moved by baser motives—spite or financial reward

—or, on occasion, by a laudable desire to serve the

public welfare if it can be done without too much

jeopardy. His communication, more than the others,

is probably the result of a calculation and more

likely to be affected by the risk of exposure. In this

instance, compelling the disclosure of a confidential

source in one highly publicized case really is likely

to restrict the flow of information to the news media.

And by doing so, it may well interfere with the

freedom of press guaranteed by the First Amend

ment.” Goldstein, Newsmen and their Confidential

Sources, N ew R e pu b l ic , March 21, 1970, pp. 13,

14.

In Garland v. Torre, 259 F. 2d 545 (2d Cir. 1958),

cert, denied, 358 U. S. 910 (1958), which we will discuss

further at a later point in this brief, Judge (now Mr. Jus

tice) Stewart, sitting by designation in the Second Circuit,

began his opinion by accepting “the hypothesis that com

pulsory disclosure of a journalist’s confidential sources of

information may entail an abridgement of press freedom by

imposing some limitation upon the availability of news.”

259 F. 2d at 548. And the Attorney General’s Guidelines

issued on August 11, 1970, supra, stated: “The Department

of Justice recognizes that compulsory process in some cir

cumstances may have a limiting effect on the exercise of

First Amendment rights.” 39 U. S. L. W. at 2111.

C. The Perimeters of the Right

Conceivably one may argue that “a limiting effect on the

exercise of First Amendment rights” is in the circumstances

24

acceptable. We do not believe it can be accepted in light

of applicable precedents, nor, on the whole, as we read his

Guidelines, does the Attorney General. But in any event,

the fact is indisputable that compulsory process to force

newsmen to identify confidential sources or divulge confi

dential information does have “a limiting effect on the

exercise of First Amendment rights.” Of course, groups

and individuals who wish to communicate with the public

through the news media, and particularly groups and in

dividuals who wish to propagandize the public through the

media, will continue to do so, regardless. They will continue

to bring themselves and their views to public attention at

times and in ways of their choice. As Judge Merrill wrote

in the opinion of the Court of Appeals in No. 70-57, how

ever, that is not the point. First Amendment interests are

not adequately safeguarded “as long as potential news

makers do not cease using the media as vehicles for their

communication with the public.” The First Amendment

“means more than that. It exists to preserve an ‘untram

meled press as a vital source of public information,’

Grosjean v. American Press Co., 297 U. S. 233, 250

(1936). . . . It is not enough that the public’s knowledge

of groups such as the Black Panthers should be confined

to their deliberate public pronouncements or distant news

accounts of their occasional dramatic forays into the public

view.” 434 F. 2d at 1084. The public’s right to know is

not satisfied by news media which act as conveyor belts for

handouts and releases, and as stationary eye-witnesses. It

is satisfied only if reporters can undertake independent, ob

jective investigations.

There is not even a surface paradox in the proposition,

as it might somewhat mischievously be put, that in order

to safeguard a public right to receive information it is

necessary to secure to reporters a right to withhold infor-

25

mation. Clearly the purpose of protecting the reporter from

disclosing the identity of a news source is to enable him to

obtain and publish information which would not otherwise

be forthcoming. So the reporter should be given a right to

withhold some information^—the identity of the source—

because in the circumstances, that right is the necessary

condition of his obtaining and publishing any information

at all. Information other than the identity of the source