United States v. Mississippi Reply Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

March 4, 1986

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United States v. Mississippi Reply Brief for Appellants, 1986. 48971f88-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/272c625c-c365-452b-aa0a-2aafb0301477/united-states-v-mississippi-reply-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

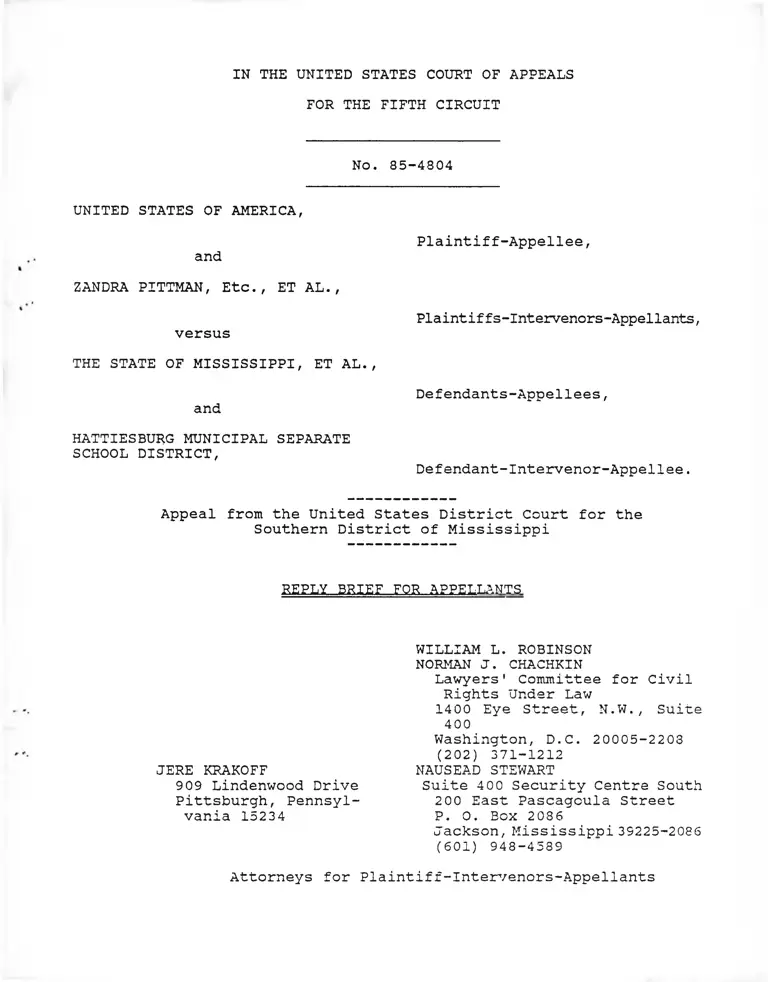

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 85-4804

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

and

ZANDRA PITTMAN, Etc., ET AL.,

versus

THE STATE OF MISSISSIPPI, ET AL.,

and

HATTIESBURG MUNICIPAL SEPARATE

SCHOOL DISTRICT,

Plaintiff-Appellee,

Plaintiffs-Intervenors-Appellants,

Defendants-Appellees,

Defendant-Intervenor-Appellee.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Southern District of Mississippi

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

JERE KRAKOFF

909 Lindenwood Drive

Pittsburgh, Pennsyl

vania 15234

WILLIAM L. ROBINSON

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

Lawyers' Committee for Civil

Rights Under Law

1400 Eye Street, N.W. , Suite

400

Washington, D.C. 20005-2203

(202) 371-1212

NAUSEAD STEWART

Suite 400 Security Centre South

200 East Pascagoula Street

P. 0. Box 2086

Jackson, Mississipoi 39225-2086

(601) 948-4589

Attorneys for Plaintiff-Inteir/enors-Appellants

Table of Authorities

Cases:

Page

Adams v. Richardson, 356 F. Supp. 92 (D.D.C.)/

aff'd en banc, 480 F.2d 1159 (D.C. Cir.

1973) ........................................... 4n

Brunson v. Board of Trustees, 429 F.2d 820 (4th

Cir. 1 9 7 0 ) ...................................... 18n

Calhoun v. Cook, 522 F.2d 717 (5th Cir. 1975) . . 17n

Carr v. Montgomery County Bd. of Educ., 377 F. Supp.

1123 (M.D. Ala. 1974), aff'd, 511 F.2d 1374

(5th Cir.), cert, denied, 423 U.S. 986 (1975) 15-16

Cisneros v. Corpus Christi Indep. School Dist.,

467 F.2d 142 (5th Cir. 1972)(en banc), cert.

denied, 413 U.S. 920 (1973) .................. 3a

Clark V. Board of Educ. of Little Rock, 705 F.2d

265 (8th Cir. 1983) ........................... 18

Davis V. East Baton Rouge Parish School Bd.,

721 F.2d 1425 (5th Cir. 1983) ................

Davis V. East Baton Rouge Parish School Bd.,

514 F. Supp. 869 (E.D. La. 1981) .............

Ellis V. Board of Pub. Instruction of Orange Coun

ty, 465 F.2d 878 (5th Cir. 1972), cert, de

nied, 410 U.S. 966 (1973) ....................

Ellis V. Board of Pub. Instruction of Orange Coun

ty, 423 F.2d 203 (5th Cir. 1970) .............

Higgins v. Board of Educ. of Grand Rapids, 508

F.2d 779 (6th Cir. 1 9 7 4 ) ...................... 14

Hightower v. West, 430 F.2d 552 (5th Cir. 1970) . . 16

Johnson v.Board of Educ. of Chicago, 604 F.2d

504 (7th Cir. 1979), vacated, 449 U.S. 915

(1980), on appeal following remand, 664 F.2d

1069 (7th Cir. 1981), vacated, 457 U.S. 52

( 1 9 8 2 ).......................................... 14

Kelley v. Metropolitan County Bd. of Educ., 463

F.2d 732 (6th Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U.S.

1001 (1972) 3a

Kelley v. Metropolitan County Bd. of Educ., 492 F.

Supp. 167 (M.D. Tenn. 1980), rev'd, 687 F.2d

814 (6th Cir. 1982), cert, denied, 459 U.S.

1183 (1983) 3a

Lee V. Anniston City School Sys., 737 F.2d 952 (5th

Cir. 1 9 8 4 ) ...................................... 17n

15, 16n, 17

6n, 7n

16n

16n

Page

Cases (continued):

Liddell v. Missouri, 731 F.2d 1294 (8th Cir.),

cert, denied, 83 L. Ed. 2d 30 ( 1 9 8 4 )......... 14-15

Mannings v. Board of Pub. Instruction of Hillsbor

ough County, Civ. No. 3554-T (M.D. Fla. May

11, 1971) ...................................... 2a

Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1974) ......... 3n

Monroe v. Board of Comm'rs of Jackson, 391 U.S.

450 ( 1 9 6 8 )...................................... 12, 13

Parent Ass'n of Andrew Jackson High School v. Ainbach,

598 F.2d 705, 719-20 (2d Cir. 1979) 14, 15n

Pate V. Dade County School Bd., 434 F.2d 1151

(5th Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 402 U.S.

953 ( 1 9 7 1 )...................................... 19

Riddick V. School Bd. of Norfolk, No. 84-1815 (4th

Cir. February 6, 1986) , petition for rehearing

p e n d i n g ........................................ 18

Ross V. Houston Independent School Dist., 699 F.2d

218 (5th Cir. 1983) ........................... 17

Seattle School Dist. No. 1 v. Washington, 458 U.S.

457 ( 1 9 8 2 ) ........................................ 4a

Seattle School Dist. No. 1 v. Washington, 473 F.

Supp. 996 (W.D. Wash. 1979), aff'd, 633 F.2d

1338 (9th Cir. 1980), aff'd, 458 U.S. 457 (1982) 4a

Stout V. Jefferson County Bd. of Educ., 537 F.2d

800 (5th Cir. 1976) ........................... 6n, 13n,

15, 16n

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ.,

402 U.S. 1 (1971) 16n, la

Tasby V. Wright, 713 F.2d 90 (5th Cir. 1983) . . . 16

United States v. Scotland Neck City Bd. of Educ.,

407 U.S. 484 (1972) 12, 13

United States v. Texas Educ. Agency (Port Arthur

ISD) , 679 F.2d 1104 (5th Cir. 1982) ......... 18n

Valley v. Rapides Parish School Bd., 702 F.2d 1221

(5th Cir.), cert, denied, 464 U.S. 914 (1983) 6n, 16-17,

Wright v. Council of City of Emporia, 407 U.S. 451

( 1 9 7 2 )............................................ 13n

- 11 -

Page

Other Authorities;

Hawley & Rossell, Policy Alternatives for Minimi

zing VThite Flight, 4 Educ. Evaluation & Pol'y

Analysis 205 (1982) ......................... 8n

C. Rossell, A School Desegregation Plan for East

Baton Rouge Parish (submitted to the U.S.

Department of Justice, Washington, D.C., Febru

ary, 1 9 8 3 ) ...................................... 6n, 7n

School Desegregation, Hearings Before the Subcomm.

on Civil & Constitutional Rights of the House

Comm, on the Judiciary, 97th Cong., 1st Sess.

( 1 9 8 1 ).......................................... 8n

U.S. Comm'n on Civil Rights, Fulfilling the Letter

and Spirit of the Law, Desegregation of the

Nation's Public Schools (1976) ................ 2a

U.S. Comm'n on Civil Rights, Reviewing a Decade of

School Desegregation 1966-1975 (1977) . . . . lln

U.S. Department of Education/Office For Civil

Rights, Survey Data Summary of Public Elemen

tary and Secondary Schools in Selected Districts:

School Year 1982-1983 (n.d.) .................. la-4a

U.S. Department of Education/Office for Civil

Rights, Directory of Elementary and Secondary

School Districts, and Schools in Selected School

Districts: School Year 1978-1979 (1980) . . . la-4a

U.S. Department: of Health, Education and Welfare/Of-

fice for Civil Rights, Directory of Elementary

and Secondary School Districts, and Schools in

Selected School Districts: School Year 1976-

1977 (1979) .................................... la-4a

U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare/Of-

fice for Civil Rights, Directory of Public

Elementary and Secondary Schools in Selected

Districts, Enrollment and Staff by Racial/Ethnic

Group, Fall, 1972 (OCR-74-5) (1974) ......... la-4a

U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare/Of-

fice for Civil Rights, Directory of Public

Elementary and Secondary Schools in Selected

Districts, Enrollment and Staff by Racial/Ethnic

Group, Fall, 1970 (OCR-72-5) (1972) ......... la-4a

- Ill -

Page

Other Authorities (continued):

U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare/Of-

fice for Civil Rights, Directory of Public

Elementary and Secondary Schools in Selected

Districts, Enrollment and Staff by Racial/Ethnic

Group, Fall, 1968 (OCR-101-70) (1970) . . . . la-4a

- IV -

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 85-4804

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

and

ZANDRA PITTMAN, Etc., ET AL.,

versus

THE STATE OF MISSISSIPPI, ET AL.,

and

HATTIESBURG MUNICIPAL SEPARATE

SCHOOL DISTRICT,

Plaintiff-Appellee,

Plaintiffs -Int ervenor s -Appel 1 ants,

Defendants-Appellees,

Defendant-Intervenor-Appellee,

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Southern District of Mississippi

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

I.

Before turning to the legal arguments advanced by the Hatties

burg school district and the United States, there are a few factual

matters which warrant careful consideration by the Court because

they are critical to an accurate evaluation of the desegregation

plans between which the district court chose. Appellees slide

too easily over the distinctions in outcomes which would be pro

duced by the "Consent Decree" and Stolee plans.

A.

The school district misrepresents the proof and the district

court's conclusions when it asserts that:

The undisputed evidence at the hearing was

that within two years, more than 30% of the

black children in the elementary grades would

be attending schools of 80% or more black

enrollment under the Stolee Plan, whereas

under the Consent Decree Plan only 26% of

the black children would be attending schools

of 80% or more black enrollment.

(Brief for Appellee HMSSD at 12 [emphasis supplied]; see also, id.

at 14, 17, 25.) The distict court in fact recited that

According to [Dr.] Rossell's projections of

enrollment two years after implementation,

30.69% of the students would be enrolled in

schools serving student bodies which are ap

proximately 80% of one race under the Stolee

Plan, and, under the Consent Decree Plan,

26.72% of the HMSSD students would be in such

schools.

(R. 714, R.Exc. 74 [Mem. Op. 12 n.28].) The two sentences quoted

do not mean the same thing.

The proportions calculated by the district court represent

the percentage of all students. Black and white, whom Dr. Rossell

projected would be attending schools "approximately 80% of one

race" two years after implementation. See R. 626, 629, R.Exc. 170,

173 [G-X 2, pp. 28, 31]. This raw statistic is not particularly

illuminating; indeed, it is somewhat misleading since it does

not distinguish between schools "approximately 80% of one race"

and schools which are virtually all-Black.

Taking Dr. Rossell's figures at face value, under the Consent

Decree plan, 732 (or 39.9%) of all the Black elementary-grade

students will be attending two formerly all-Black schools: Eureka,

- 2 -

which will be 95.8% Black, and Bethune, which will be 86.7% Black

(R. 626, R.Exc. 170 [G-X 2, p. 28]). Eighty white students will

be attending these facilities f id. ̂ . In contrast, under the Stolee

plan, no school will be as much as 85% Black. According to Dr.

Rossell's figures, under the Stolee plan Bethune will be 79.7%

Black, Eureka will be 79.0% Black, and Jones will be 78.3% Black

(R. 629, R.Exc. 173 [GX-2, p. 31]). (These are the three schools

whose enrollments were combined by the district court in note 28

of its opinion.) A total of 607 (or 35.5%) of all Black elementary

students will attend these schools. One hundred fifty-eight white

students will be enrolled in these facilities f i d . .

B.

Given these results, we think it is quite wrong to say, as

does the United States (Brief, at 32) that "the two plans the

court considered promised comparable overall results." The only

conceivable basis for such a statement assumes that the focus is

on schools that are "approximately 80% Black." But this masks the

extent to which the Consent Decree plan fails to dismantle the

dual system because it provides for the continuation, as severely

racially isolated schools, of two facilities that have always

been maintained as Black schools by the HMSSD.

The government's fixation on the "80%" figure for a school

system in which more than 60% of all elementary students are Black

is particularly difficult to understand.^

^See Milliken v. Bradley. 418 U.S. 717, 737-41 & n.l9 (1974)

(existence of predominantly minority schools, without significant

disparities in racial composition among schools, even in system

which practiced unconstitutional segregation, does not establish

- 3 -

Moreover, as we indicated in our opening brief, Dr. Rossell's

enrollment projections for the Consent Decree plan include kinder

garten students, while the projections for Dr. Stolee's plans do

not fcompare R. Exc. 170, 173). Because of the change in state

law, those students should be excluded from the projections for

the Consent Decree plan. See Brief for Appellants at 11 n.26;

Brief for the United States, at 26 n.17.̂ when this is done,

Bethune is projected to be 99.2% Black and Eureka 95.1% Black;

and thus, 36.6% of all Black elementary students would remain in

virtually all-Black schools under the Consent Decree plan.^

The realistic comparison in this case is between the plan

approved below, which leaves two virtually all-Black schools en

rolling more than a third of all Black elementary students, and

inadequacy of remedy which justifies interdistrict relief); Adams

V. Richardson. 356 F. Supp. 92, 96-97 (D.D.C.), aff'd en banc.

480 F.2d 1159 (D.C. Cir. 1973)(federal agency enforcing Title VI

must require formerly segregated school districts to provide non-

discriminatory explanation for existence of schools which deviate

20 or more percentage points from system-wide minority enroll

ment .)

^Despite the trial testimony about kindergartens, the school

district continues to refer to Dr. Rossell’s projections including

them (see Brief for Appellee HMSSD, at 8, 2a) , as does the govern

ment (see Brief for the United States, at 11 text at n.lO). This

is doubly misleading. First, Dr. Rossell's projections include

white kindergarten students at Bethune as the only source of any

significant white enrollment at that school. Second, they also

omit kindergarten enrollments at other schools — which are now

likely to occur on a "neighborhood" basis (Tr. 115, 175) and which

therefore would reinforce the traditional racial identiflability

of those schools.

^We agree with the government that it is "possible" that

some white parents will enroll their children in Bethune's extended

day program (Brief for the United States, at 2 6 n.l7) but we adhere

to our insistence that this possibility is quite remote under

the circumstances of this case (see Brief for Appellants, at 30-

32) .

- 4 -

a system of student assignments (the Stolee plan) under which no

school would be more than 20 percentage points above or below

the system-wide proportion of Black students in the elementary

grades.^

C.

Both the school district (Brief for Appellee HMSSD, at 8,

14) and the government (Brief for the United States, at 12, 20)

rely upon Dr. Rossell's prediction that if the Stolee plan were

implemented, 36.2% of the district's current white elementary

enrollment would withdraw from the system within two years —

while under the Consent Decree plan only 8.6% of these white stu

dents would be lost. Dr. Rossell's testimony and report, however,

are an inadequate legal justification for the district court's

decision to leave two historically Black schools segregated in a

system as small and logistically manageable as Hattiesburg. As

we said in our opening brief:

White flight resulting from hostility to the

dismantling of the dual system will obviously

be greater under a plan which assigns white

students in substantial numbers to all of

the formerly Black schools than under a plan

which leaves two of five all-Black schools

unchanged. Dr. Rossell's first proposition

[greater white flight under the Stolee plan]

simply disregards the law of Monroe. Scotland

Neck, and their progeny in this Circuit.

(Brief for Appellants, at 42.)

'^Even that comparison does not represent a fully accurate

portrayal, because Dr. Rossell's "white flight" calculations were

done for each of two years following implementation of the Stolee

plan but only once for the Consent Decree plan (see Brief for

Appellants, at 22, 45 n.86). Since Dr. Rossell could not remember

the basis for this procedure and did not know what the effect of

altering it would be (id. at 22 n.56), the actual outcome under

the Consent Decree plan — even if Dr. Rossell's "white flight"

formulas are correct — is not precisely known.

- 5 -

In addition, for the reasons summarized below, the apparent

precision of Dr. Rossell's figures is deceptive and they are an

insufficient basis upon which to uphold the district court's judg

ment: First, the figures represent predictions about future events

in Hattiesburg based upon Dr. Rossell's analysis of past experience

in two quite different systems. Baton Rouge and Los Angeles (Tr.

560-61).^ The formulas purporting to quantify the extent to

which white students would fail to report to the schools to which

they were assigned, dependent upon the projected racial composition

of those schools (see R. 605, R.Exc. 148 [G-X 2, p. 17]) were

devised by averacinc the experience at many schools in these two

districts (Tr. 561), each of which is considerably larger than

Hattiesburg. Whether the much smaller number of schools in Hat

tiesburg would have the same experience as this average is not

at all clear.®

^Compare Valiev v. Rapides Parish School Bd., 702 F.2d 1221,

1226 (5th Cir.) (withdrawal of whites assigned in past to same

school), cert, denied. 464 U.S. 914 (1983); Stout v. Jefferson

County Bd. of Educ.. 537 F.2d 800, 802 (5th Cir. 1976)(same).

®There was, in fact, substantial variation from school to

school in Baton Rouge. For example, the court-ordered plan paired

Wildwood Elementary School, 19% Black, and University Terrace,

78% Black, for an overall enrollment projection of approximately

31% Black in each facility. Davis v. East Baton Rouge Parish

School Bd. . 514 F. Supp. 869, 879, 884 (E.D. La. 1981) . According

to Dr. Rossell's formulas. University Terrace might have been

anticipated to lose close to 25% of the white students reassigned

to it (R. 605, R.Exc. 148 [GX-2, p. 7]). However, in Baton Rouge' s

actual experience. University Terrace enrolled 132% more whites

than projected in the first year after implementation. C. Rossell,

A School Desegregation Plan for East Baton Rouge Parish (submitted

to the U.S. Department of Justice, Washington, D.C., February,

1983), Table 7.

Many other schools simply did not fit the "averages" which

Dr. Rossell computed. Goodwood Elementary, for instance, was a

98%-white school prior to implementation of the court decree which

- 6 -

Second, in both Los Angeles and Baton Rouge the desegregation

orders were imposed upon school systems and communities which

had had no prior experience with effective desegregation plans.

Here, to the contrary, the Hattiesburg secondary schools have

been operated on a fully desegregated basis since implementation

of the pairing and grade restructuring plan in 1971.

placed it in a cluster expected to be 41% Black. 514 F. Supp. at

879, 884. The Rossell formula would project a loss of 10% of

its white students upon implementation; instead, the white enroll

ment dropped by only 0.6%. C. Rossell, supra.

Extrapolating from this experience to Hattiesburg seems to

us to be a venture fraught with uncertainty.

"^The government refers to Dr. Rossell's testimony that the

HMSSD lost 30% of its white enrollment at the secondary level

following implementation of this plan (Brief for the United States,

at 13, 24). However, it does not note Dr. Rossell's admission,

on cross-examination, that the figures on the historical experience

of the HMSSD which were contained in her report failed to deduct

"normal white enrollment decline" (see Tr. 606) experienced by

nearly every urban school system (Tr. 573). As Dr. Rossell has

explained.

Most recently the term "white flight" has

erroneously been used to describe the decline

in central city white public school enroll

ment. Most of this decline is a function of

the secular suburbanization trend and the

declining birthrate. . . . There has been an

annual white enrollment decline of almost 1

percent in all schools since 1968. It is

now almost 3 percent. . . . Because they bene

fit from northern migration to the South,

some southern countvwide school districts

have stable or increasing whits enrollment

in spite of the national decline in birth

rate . . . . The normal change in the white

percentage of school enrollment in northern

central city school districts should be a

decline of 2 percentage points annually.

This should also be true for the South. . . .

Determining the decline in white public school

enrollment resulting from school desegregation

requires isolating the impact of policy from

these long-term demographic trends.

[footnote continued on next page]

- 7 -

Third, as we previously observed (supra note 4) , Dr. Rossell's

calculations of expected ’’white flight” from Hattiesburg departed

from the methodology outlined in her own report. For example,

her Baton Rouge and Los Angeles studies apparently indicated that

white enrollment projections at formerly white schools should be

reduced in each of the first two years after implementation (R.

605, R.Exc. 148 [GX-2, p. 7]; but see Tr. 629-33). For Hatties

burg, however. Dr. Rossell ’’collapsed” the calculations because

of uncertainties about the extent of flight which would occur.

She was unable to provide any credible explanation for this ap

proach:

Q . . . So is it not true that the formerly

white schools which have reassigned blacks

to them should have two adjustments made,

one for first-year white flight and one for

second-year white flight?

A Yes. I would think that’s true.

Q And was that done on this table? . . .

A . . . Let me explain [w]hat I did on this

table. Since I don’t know what first-year

effects are going to be in terms of— It wasn’t

clear to me what the first-year effects were

going to be. I collapsed that into the second

year. Now, what difference is this going to

make I don’t know.

Hawley & Rossell, Policy Alternatives for Minimizing White Flight,

4 Educ. Evaluation & Pol’y Analysis 205, 206-07 (1982)(emphasis

supplied); accord. School Desegregation, Hearings Before the Sub-

comm. on Civil & Constitutional Rights of the House Comm, on the

Judiciary. 97th Cong., 1st Sess. 217, 219-20 (1981)(testimony of

Christine Rossell).

The limited excerpts from Dr. Rossell’s testimony that are

attached to the government’s brief are incomplete and we urge

the Court to read the entire portion of the transcript devoted

to her examination, Tr. 542-648.

- 8 -

Q Well, I don't want to ask you to calculate

what difference it makes. In your analysis

of the Stolee plan, did you— Let me ask you

to turn— Did you apply two years of white

flight or one year of white flight?

A Two years.

Q So it's really difficult to compare the

adequacy of the two analyses. You didn't

apply exactly the same factors to each.

A Let me tell you the difference. These

are M-to-M transfers as opposed to reassign

ments, and M-to-M transfers produce less white

flight, but we don't know how much less. I

think I just didn't do it the first year be

cause I assumed by adding 15 percent the second

year that would take care of whatever differ

ential white flight there might be from these

M-to-M transfers.

Q Directing your attention to Grace Christian

school, under what column do you show 60 black

students?

A I show them in rezoning.

Q And on the chart that's on the easel there,

if you look at it, I think in the right-hand

column you'll agree it shows 60 blacks from

Jones. And the testimony was that that is a

portion of the students from Jones who will

be reassigned mandatorily because only 72

places will be reserved for former Jones stu

dents when it's made into a magnet school.

So those are not M-to-M transfers. Is that

correct? They're mandatory reassignments?

A That's correct.

Q So we really have two slightly different

sets of computations applied to the District

Alternative Plan and the Stolee plan.

A I'm trying to remember the rationale here.

I simply can't.

(Tr. 640-42)(emphasis supplied.)®

^Similar problems attended all of Dr. Rossell's calculations.

[footnote continued on next page]

- 9 -

Appellants' expert witness, Dr. Stolee, declined to engage

in a guessing game about the extent of "white flight" that might

follow implementation of a pairing and clustering plan. But it

is hardly correct to characterize his testimony by saying that

"he would not dispute the projections of Dr. Christine Rossell"

(Brief for Appellee HMSSD, at 14). What Dr. Stolee said was (Tr.

723)(emphasis supplied):

A No. I've never said I disagree with that,

because the evidence does show that some whites

leave no matter what you do. I mean, if you

desegregate just a little bit, like your [the

Consent Decree] plan, she said there was going

to be some white loss. If you [de]segregate

thoroughly, like the plan we presented, there's

going to be some white loss.

Q I'm asking about yours, though.

A Oh, I can't argue against her findings

that there will be some white loss. There

would be. The magnitude could be, you know,

the same or more or less than what she says.

The social sciences are not that exact a sci

ence.

The extent of "white flight" in reaction to desegregation

decrees varies widely among individual school systems. We attach,

as an Appendix to this brief, an analysis of publicly available

data which shows this considerable variation in rates of white

enrollment loss. From these data, as well as the Baton Rouge

experience (see supra note 6) it is extremely difficult to discern

any regular pattern of white withdrawal in relation to desegrega-

See, e.g.. Tr. 634-35 ("I arbitrarily picked five students from

the magnet school. . . . That may be part of one of the problems

I had with this data, which is that numbers didn't add up. So

in some cases I had the choice of adjusting their totals, or I

had the choice of adjusting their reassignments. . . . I just

assumed that half of them would be white")(emphasis supplied).

- 10 -

tion steps, such as Dr. Rossell attempted to extrapolate from

Baton Rouge and Los Angeles.^ We respectfully submit that, in

spite of the scientific patina sought to be affixed to them. Dr.

Rossell's testimony and report provide no sounder basis for refus

ing to order complete desegregation than did the fervent predic-

^The deficiency of the plan approved below can, however, be

analyzed statistically;

The Standardized Measure of Segregation (Rbw)

is that used in previous studies and is a

function of the measure of interracial school

contact and the proportion of white children

in the school district. If the same proportion

of white children were in each school, then

Sbw, the measure of interracial school contact

defined above, would be equal to Pw, the pro

portion white. If the black and white children

were each in schools by themselves, then Sbw

would be zero. Thus, the measure of segrega

tion may be constructed to indicate how far

Sbw is from Pw, or the degree to which segre

gation among schools within a district is

responsible for the value of Sbw. Hence,

Rbw is defined as:

Rbw = Pw - Sbw

Pw

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Reviewing a Decade of School

Desegregation 1966-1975 125-26 (1977)(emphasis supplied).

When these calculations are performed for the Consent Decree

plan and the Stolee plan, even accepting Dr. Rossell's '*white

flight” pronections (R. 626, 629, R.Exc. 170, 173 [G-X 2, pp. 28,

31]), the results are striking:

Plan

Consent Decree

Stolee

Second Year After Implementation

% White Sbw Rbw

39.6

31.3

33.0

29.8

16.7

4 .8

In other words, the Consent Decree plan results in more than three

times as much segregation as the Stolee plan — and that in the

form of two virtually all-Black schools (see supra p. 4).

- 11 -

tions of school authorities in Monroe and similar cases, described

in our opening brief.

II.

The briefs of the appellees present a curious approach to

the law governing this case. On the one hand, they seek to avoid

controlling Supreme Court precedent by mischaracterizing it. On

the other, they gather together virtually every decision of a

federal court which either allowed a one-race school to exist or

which stated that "white flight” could be considered in fashioning

a remedy — and with little recognition of the salient facts or

the legal reasoning employed, simply advance these rulings as a

blanket justification for what occurred below. Neither effort

is persuasive.

A.

The fundamental legal principle applicable to this appeal

is that feared, predicted, or fancied "white flight" may not "be

accepted as a reason for achieving anything less than complete

uprooting of the dual system. See Monroe v. Board of Commission

ers . 391 U.S. 450, 459." United States v. Scotland Neck City

Board of Education. 407 U.S. 484, 491 (1972). Appellees each

seek to deflect the force of Scotland Neck by suggesting that in

that case, "the school district [was] arguing that nothing should

be done because of the likelihood of white flight," Brief for

Appellee HMSSD, at 31 (emphasis in original), or that there "the

local school board had relied on fear of white flight as a basis

- 12 -

for taking no action to desegregate,” Brief for the United States,

at 39 (emphasis in original).

To the contrary, the Scotland Neck school district officials

were willing to operate a single school complex for all of its

students, as well as students who wished to transfer from the

Halifax County system (407 U.S. at 487) . This Scotland Neck system

would have been 57% white and 43% Black fid.) — quite a change

from the previous circumstances, when all white students attended

traditionally all-white schools and 97% of the Black students

were in all-Black schools (id. at 486). Despite this limited

improvement, the Supreme Court held the plan was unacceptable

(id. at 489-91) and, citing Monroe, specifically rejected the

"white flight" thesis even though advised that integration of

the county school system together with Scotland Neck had been

accompanied by a substantial drop in the proportion of white stu

dents (id. at 491 & n.5).^^ Scotland Neck is controlling here.

^*^The government argues that this Court so described Scotland

Neck in Stout v. Jefferson County Bd. of Educ. , 537 F.2d 800,

802 n.2 (5th Cir. 1976). That is not quite right, either. What

Judge Gee's opinion in Stout said was that the school authorities

in the Scotland Neck case "advanced fear of white flight as a

reason for refusing to attempt to dismantle an existing dual sys

tem." As we indicate in text, infra, the scheme which the Supreme

Court rejected in Scotland Neck involved limited desegregation

which was, however, inadequate to eliminate the vestiges of the

dual system — as in this case — and not a total refusal to act.

^^Similarly, in the companion case, Wright v. Council of

City of Emporia. 407 U.S. 451 (1972) , prior to creation of a separ

ate city district, no whites attended Black schools and only 98

of 2,510 Black students were in formerly white facilities (id.

at 455) . The City of Emporia "proposed to operate its own schools

on a unitary basis, with all children enrolled in any particular

grade attending the same school" (id. at 457-58) ; only 48% of

Emporia's school population was white (id. at 457). The Supreme

Court approved the district court's refusal to permit the carve-

out. "The District Court, with its responsibility to provide an

- 13 -

B.

Appellees seek to rely upon a wholly inapposite group of

cases approving limitations on purely voluntary desegregation

initiatives, adopted in part out of concern about "white flight."

Whatever the correctness of those decisions as applied to the

circumstances to which they are addressed they have no bearing

on the issues here, as the courts involved recognized. See Higgins

V. Board of Education of Grand Rapids. 508 F.2d 779, 793-94 (6th

Cir. 1 9 7 4 ) Parent Association of Andrew Jackson High School

V. Ambach. 598 F.2d 705, 719-20 (2d Cir. 1979) Johnson v. Board

of Education of Chicago. 604 F.2d 504, 516-17 (7th Cir. 1979),

vacated. 449 U.S. 915 (1980), on appeal following remand. 664

F.2d 1069 (7th Cir. 1981), vacated. 457 U.S. 52 (1982) Liddell

effective remedy for segregation in the entire city-county system,

could not properly allow the city to make its part of that system

more attractive where such a result would be accomplished at the

expense of the children remaining in the county" (id. at 4 68) .

Cf. Tr. 259 (50% cap on enrollment of Black students in magnet

schools intended "to make those magnet schools more attractive

to the white community").

^^The court in Higgins suggested that the "authority of school

officials to formulate plans for achieving an improved racial

balance should not be as restrictive in the case of a school system

which has not been found to have engaged in purposeful segregation

as for a system which has practiced de jure segregation," 508

F.2d at 793.

^^The Ambach opinion contrasts what "the Constitution com

mands" of a formerly segregated system with "the limited circum

stances of purely voluntary action," 598 F.2d at 720.

^^The Seventh Circuit's original opinion expressly distin

guished between constitutionally mandated and voluntary plans

and relied on Higgins and Ambach. But since its judgment was

vacated by the Supreme Court, the opinion in any event has no

precedential weight.

- 14 -

V. Missouri. 731 F.2d 1294, 1313-14 (8th Cir.)/ cert, denied. 83

L. Ed. 2d 30 (1984).

C.

Appellees have also collected an assortment of decisions

allowing the continued operation of all-Black or heavily Black

schools in districts still in the process of satisfying their

constitutional obligations, or sanctioning consideration of “white

flight" in fashioning a remedy. In each of these cases, the reas

oning of the courts which decided them supports our claims here.

Some of the cases involved much larger school districts within

which the overwhelming majority of schools were fully desegregated;

allowing a truly "small number of one-race schools" to continue

under those circumstances — especially where practical and logis

tical problems made their desegregation difficult to achieve —

these courts held, did not make the districts "non-unitary."

See Davis v. East Baton Rouge Parish School Board. 721 F.2d 1425,

1433 (5th Cir. 1983);^® Stout v. Jefferson County Board of Educa

tion. 537 F.2d 800, 802-03 (5th Cir. 1976) Carr V. Montgomery

^^The Liddell court noted, in approving a consent decree set

tling an interdistrict action prior to a finding of liability, that

a "secondary remedial objective" of educational improvements re

quired by the decree was to increase the attractiveness of city

schools and lessen "white flight," and, citing Higgins and Ambach,

held this to be permissible in the context of a voluntary plan.

^®The district court in Davis "found itself constrained by

the facts of geography and by difficulties of transportation to

allow eleven essentially one-race elementary schools to remain,"

721 F.2d at 1433. As we emphasized in our opening brief, this

Court's reasoning in Davis strongly supports our position in this

case. The school district's half-hearted effort to distinguish

Davis (see Brief for Appellee HMSSD, at 30-31) is unavailing.

17"The unfortunate presence of these three one-race schools,

- 15 -

County Board of Education. 377 F. Supp. 1123, 1135 (M.D. Ala.

1974) , a f f d . 511 F.2d 1374 (5th Cir.) , cert, denied. 423 U.S. 986

(1975);^® Hightower v. West. 430 F.2d 552, 555 (5th Cir. 1970).

Other decisions dealt with districts which, unlike Hattiesburg,

had taken vigorous and meaningful action to integrate their systems

in the past, but in which the courts found that post-imolementa-

tion^® demographic changes had made further efforts impracticable.

See Tasbv v. Wright. 713 F.2d 90, 99 (5th Cir. 1983) ,*21 Valley

serving just over 1100 total pupils, in a desegregated system

serving many thousands, is to be deplored. But they are the result

of demography; the system as a whole is desegregated and the over

whelming majority of all students attend such facilities . . . ,"

537 F.2d at 803.

18iiThis Court desires to emphasize that the remaining predom

inantly black schools in this school system under the board's

plan cannot be effectively desegregated in a practicable and work

able manner," 377 F. Supp. at 1135.

^®In Hightower the Court concluded that contiguous pairing

of the few remaining virtually all-Black schools in southern Fulton

County, Georgia would still produce schools having racially dispro

portionate enrollments, and noted that most of the school system

was fully desegregated. Of course, Hightower was decided prior

to Swann. and this Court did not consider the use of non-contiguous

zoning or clustering in that case. Indeed, Hightower relied on

Ellis V. Board of Pub. Instruction of Orange County. 423 F.2d

203 (5th Cir. 1970), but see. e .g.. id., 465 F.2d 878 (5th Cir.

1972), cert, denied. 410 U.S. 966 (1973).

^^Compare Davis v. East Baton Rouge Parish School Bd., 721

F.2d at 1435-36 and cases cited.

"Like the courts in Atlanta and Houston, [the district

court] was confronted with a school system in which the traditional

desegregation tools could not be used to eliminate the continued

existence of one-race schools, and thus it concluded that it should

do whatever time and distance factors allowed," 713 F.2d at 99.

Appellees' reliance on Tasbv is surprising. All that the panel

announced in that case was that a one-year delay in achieving a

reduction of less than one point in the white student enrollment

percentage at a high school would not have been impermissible

even if part of the justification were to limit adverse reaction

by white parents to school reasignments. That is a far cry from

the situation here. Moreover, in Tasbv the Court specifically

- 16 -

V. Rapides Parish School Board. 702 F.2d 1221, 1226 (5th Cir.),

cert, denied. 464 U.S. 914 ( 1 9 8 3 ) Ross v. Houston Independent

School District. 699 F.2d 218, 228 (5th Cir. 1983).^3 There is

nothing in these decisions which conflicts with the principles

upon which we rely, and which were so aptly summarized by this

Court in Baton Rouge, see Brief for Appellants, at 26-28.^4

upheld the district court's refusal to allow a resegregation plan

prompted by the desires of some Black parents in Dallas to have

"neighborhood schools," 713 F.2d at 97.

22"Various plans approved by the district court over the

long history of this litigation did not realize one of their pri

mary goals: desegregation of the Cheneyville schools," 702 F.2d

at 1226. Again, appellees' reliance cn Valiev is quixotic, since

the Court there sanctioned, on the school board's appeal, consid

eration of the possibility of "white flight" which led the district

court to select an alternative plan which integrated all schools

remaining open in the area, at all grade levels, see 702 F.2d at

1226-28.

23This Court in Ross noted that "HISD is a singular district,

with unusual, perhaps unique, problems" and relied upon "the undis

puted fact that HISD is unitary in every aspect but the existence

of a homogeneous student population; the intensive efforts that

have been made to eliminate one-race schools; and the district

court's conclusion that further measures would be both impractical

and detrimental to education . . . ," 699 F.2d at 228. Cf. Calhoun

V. Cook. 522 F.2d 717, 719 (5th Cir. 1975) (" . . . in Atlanta,

the unique features of this district distinguish every prior school

case pronouncement").

24t w o further comments are appropriate.

(1) Lee V. Anniston City School Svs. . 737 F.2d 952 (11th

Cir. 1984) , cited by appellees, has nothing to do with the issues

here. It was a challenge to a school board decision to close a

junior high school in a Black neighborhood and replace it with a

middle school on a neutral site. Plaintiffs challenged the deci

sion not to build the new school on the same site as "racially

motivated and based on an impermissible fear of 'white flight'

from the system," 737 F.2d at 955. The district court found no

racial motive and the Court of Appeals affirmed, id. at 956-57.

These conclusions were unaffected by the district court's obser

vation that when the new school opened — on a fully integrated

basis — there would be "greater promise for future desegregation

by attracting more white students from the surrounding area,"

id. at 957. Since no facility was to remain segregated (the opin-

- 17 -

Finally, appellees cite two decisions of other Circuits which

permitted school systems that had implemented extensive desegre

gation plans to engage in the deliberate resegregation of some

schools, purportedly to keep others integrated, Riddick v. School

Board of Norfolk. No. 84-1815 (4th Cir. February 6, 1986), petition

for rehearing pending; Clark v. Board of Education of Little Rock.

705 F.2d 265 (8th Cir. 1983) . These rulings are of dubious valid

ity and the cases are in any event easily distinguishable from

this one.25

ion refers only to some unspecified level of adverse impact on

the "racial mix" of an elementary school, id.), the relevance of

this decision to Hattiesburg is slight.

(2) United States v. Texas Educ. Agency (Port Arthur ISP).

679 F.2d 1104 (5th Cir. 1982), cited by the government, surely

did not enunciate any rule about the constitutional validity of

a phase-in period for magnet schools. The Court there merely

approved a stipulation withdrawing the appeal on the basis of a

settlement between the United States and the school district, in

a case in which there were no private parties and the issue was

apparently not raised.

25secause Hattiesburg has never implemented an effective

elementary-level desegregation plan, we do not think Riddick and

Clark have any application to this case. Indeed, the Riddick

panel explicitly limited its holding to "school systems which

have succeeded in eradicating all vestiges of de jure segregation,"

slip op. at 59; compare Brief for Appellants, at 7 n.l7. But we

are also firmly convinced that these two rulings, taken on their

own merits, are incorrect and ought not be followed. The consti

tutional requirement of desegregation "is not founded upon the

concept that white children are a precious resource which should

be fairly apportioned." Brunson v. Board of Trustees. 429 F.2d

820, 826 (4th Cir. 1970)(Sobeloff, J., concurring).

- 18 -

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, and for those set forth in our

opening brief, appellants respectfully pray that the judgment

below be reversed and the case remanded with instructions to order

the implementation, in the 1986-87 school year, of the Stolee

plan — or of an equally effective mandatory student reassignment

plan, see. e.g., Pate v. Dade County School Board. 434 F.2d 1151,

1158 (5th Cir. 1970), cert, denied. 402 U.S. 953 (1971).

Respectfully submitted.

JERE KRAKOFF

909 Lindenwood Drive

Pittsburgh, Pennsyl

vania 15234

WILLIAM L. ROBINSON

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

Lawyers' Committee for Civil

Rights Under Law

1400 Eye Street, N.W., Suite

400

Washington, D.C. 20005-2208

(202) 371-1212

NAUSEAD STEWART

Suite 400 Security Centre South

200 East Pascagoula Street

P. 0. Box 2086

Jackson, Mississippi 39225-2086

(601) 948-4589

Attorneys for Plaintiff-Intervenors-Appellants

- 19 -

A P P E N D I X

APPENDIX

Loss of White Students in Other School Districts

In Charlotte, North Carolina, meaningful desegregation began

in the early 1970's.26 charlotte's experience, while not atypical

of court-ordered districts, appears to be quite different from

Baton Rouge and Los Angeles; the immediate post-implementation

years appear to indicate reduced, rather than increased, loss of

white students. An analysis of publicly available statistics'^

shows the following:

^^See Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenbura Board of Education, 402

U.S. 1 (1971).

27Sources of data: U.S. Department of Health, Education,

and Welfare/Office for Civil Rights, Directory of Public Elementary

and Secondary Schools in Selected Districts. Enrollment and Staff

by Racial/Ethnic Group, Fall, 1968 (OCR-101-70)[hereinafter cited

as 1968 OCR Data! 1057 (1970); U.S. Department of Health, Educa

tion, and Welfare/Office for Civil Rights, Directory of Public

Elementary and Secondary Schools in Selected Districts, Enrollment

and Staff by Racial/Ethnic Group, Fall. 1970 (OCR-72-5) [hereinafter

cited as 1970 OCR Data! 2037 (1972); U.S. Department of Health,

Education, and Welfare/Office for Civil Rights, Directory of Public

Elementary and Secondary Schools in Selected Districts, Enrollment

and Staff by Racial/Ethnic Group, Fall, 1972 (OCR-74-5) [hereinafter

cited as 1972 OCR Datal 1002 (1974) ; II U.S. Department of Health,

Education, and Welfare/Office for Civil Rights, Directory of Ele

mentary and Secondary School Districts, and Schools in Selected

School Districts; School Year 1976-1977 [hereinafter cited as 1976

OCR Data! 1321 (1979); II U.S. Department of Education/Office

for Civil Rights, Directory of Elementary and Secondary School

Districts, and Schools in Selected School Districts; School Year

1978-1979 [hereinafter cited as 1978 OCR Datal 1014 (1980); II

U.S. Department of Education/Office for Civil Rights,Survey Data

Summary of Public Elementary and Secondary Schools in Selected

Districts; School Year 1982-1983 [hereinafter cited as OCR 1982

Datal 664 (n.d.).

- la -

Charlotte;

Year

# VThite

Pupils

% White

Pupils

Loss

(Gain)

Of White

Pupils

Annualized

% Loss % Loss

(Gain) (Gain)

Of White Of White

Pupils Pupils

1968 58,623 70.5

1970 56,819 68.9 1,804 3.1/2 yr. 1.6

1972 53,629 67.2 3,190 5.6/2 yr. 2.8

1976 50,656 64 2,973 5.5/4 yr. 1.4

1978 47,831 62 2,825 5.6/2 yr. 2.8

1982 42,473 58 5,358 11.2/4 yr. 2.8

Similarly, Tampa, Florida, which desegregated completely in

1971,28 indicates considerable stability:29

Tampa:

Annualized

Year

# White

Pupils

% White

Pupils

Loss

(Gain)

Of White

Pupils

% Loss

(Gain)

Of White

Pupils

% Loss

(Gain)

Of White

Pupils

1968 74,629 73.9

1970 77,794 73.8 (3,165) (4.2)/2 yr . (2.1)

1972 80,136 74.5 (2,342) (3.0)/2 yr . (1.5)

1976 86,686 76 (6,550) (8.2)/4 yr . (2.1)

1978 83,100 74 3,586 4.2/2 yr. 2.1

1982 81,793 74 1,307 1.6/4 yr. 0.4

Other school districts subject to mandatory desegregation

orders appear to have had more white loss initially but their

experience is inconsistent with Dr. Rossell's prediction that

white flight continues at high levels for many years after imple-

28see Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction of Hillsborough

County. Civ. No. 3554-T (M.D. Fla. May 11, 1971); U.S. Commission

on Civil Rights, Fulfilling the Letter and Spirit of the Law,

Desegregation of the Nation's Public Schools 54-55 (1976).

29sources: 1968 OCR Data, at 245; 1970 OCR Data, at 253 ;

1972 OCR Data, at 240; I 1976 OCR Data, at 308; I 1978 OCR Data,

at 265; I 1982 OCR Data, at 193.

- 2a -

mentation. Two examples, for which data are given b e l o w , a r e

Corpus Christi^^ and Nashville.

Corpus Christi;

Year

# White

Pupils

% White

Pupils

Loss

(Gain)

Of White

Pupils

Annualized

% Loss % Loss

(Gain) (Gain)

Of White Of White

Pupils Pupils

1968 22,097 47.9

1970 20,901 45.2 1,196 5.4/2 yr. 2.7

1972 18,798 41.3 2,103 10.1/2 yr. 5.1

1976 13,952 34 4,846 25.8/4 yr. 6.5

1978 11,994 31 1,958 14.0/2 yr. 7.0

1982 10,224 27 1,770 14.8/4 yr. 3.7

Nashville;

Year

# White

Pupils

% White

Pupils

Annualized

Loss % Loss % Loss

(Gain) (Gain) (Gain)

Of White Of White Of White

Pupils Pupils Pupils

1968 71, 039 75.8

1970 71, 603 75.1 (564) (0.8)/2 yr. —

1972 61, 402 71.9 10,201 14.2/2 yr. 7.1

1976 53, 665 69 7,737 12.6/4 yr. 3.2

1978 50, 021 68 3,644 6.8/2 yr. 3.4

1982 42, 538 65 7,483 15.0/4 yr. 3.8

^^Sources: 1968; OCR Data . at 1385. 1479; 1970 OCR Data, at

1346, 1377; 1972 OCR Data. at 1301, 1329; II 1976 OCR Data, at

1673, 1710; II 1978 OCR Data, at 1320. 1363: II 1982 'OCR Data,

at 837, 872 •

2 ̂ See Cisneros V . Corpus Christi Indep. School Dist.. 467

F.2d 142 (5th Cir. 1972^ fen banc) . cert. denied, 413 U.S. 920

(1973) .

^^See Kelley v. Metropolitan County Bd. of Educ., 463 F.2d

732 (6th Cir.), cert, denied. 409 U.S. 1001 (1972). Subsequent

to this ruling, the district court approved an incomplete and

inadequate plan for further desegregation in part because of his

concern about "white flight," but this decision was reversed by

the Court of Appeals. See Kelley v. Metropolitan County Bd. of

Educ. . 492 F. Supp. 167, 189-92 (M.D. Tenn. 1980), rev'd , 687

F.2d 814, 823 n.l2 & accompanying text (6th Cir. 1982), cert, de

nied. 459 U.S. 1183 (1983).

- 3a -

Seattle, Washington did not implement any mandatory desegrega

tion until 1972-73, when it began a middle school program;^^ man

datory reassignments at other levels did not take place until

the 1978-79 school year.^'^ Its rate of white enrollment decline

has been significantly higher than Dr. Rossell's "normal decline"

figure, both before and after desegregation:^^

Seattle;

Year

# White

Puoils

% White

Puoils

Loss

(Gain)

Of White

Puoils

Annualized

% Loss % Loss

(Gain) (Gain)

Of White Of White

Puoils Puoils

1968 77,293 82.2

1970 66,905 79.7 10,388 13.4/2 yr. 6.7 %

1972 58,024 77.1 8,881 13.3/2 yr. 6.7

1976 41,767 68.0 16,257 28.0/4 yr. 7.0

1978 34,091 62 7,676 18.4/2 yr. 9.2

1982 21,994 52 12,097 35.5/4 yr. 8.9

Finally, we present statistics for Newark, New Jersey, a

school system which to our knowledge has never been the subject

of a desegregation order from a court or administrative agency.

Like Seattle, the available data^^ show declines in the proportion

^^See Seattle School Dist. No. 1 v. Washington. 473 F. Supp.

996, 1005-06 (W.D. Wash. 1979), aff»d. 633 F.2d 1338 (9th Cir.

1980), aff'd. 458 U.S. 457 (1982).

34See 458 U.S. at 461; 473 F. Supp. at 1007.

25sources: 1968 OCR Data, at 1563; 1970 OCR Data, at 1524;

1972 OCR Data, at 1457; II 1976 OCR Data, at 1913; II 1978 OCR

Data, at 1542; II 1982 OCR Data, at 1001.

^^Sources; 1968 OCR Data, at 869; 1970 OCR Data, at 887;

1972 OCR Data, at 854; II 197 6 OCR Data, at 1175; II 1978 OCR

Data, at 886; II 1982 OCR Data, at 577.

- 4a -

of white enrollment which exceed the "normal” declines about which

Dr. Rossell has written and testified:

Newark:

Year

# White

Puoils

% White

Pupils

Loss

(Gain)

Of White

Pupils

Annualized

% Loss % Loss

(Gain) (Gain)

Of White Of White

Pupils Pupils

1968 13,716 18.1

1970 11,188 14.3 2,528 18.4/2 yr. 9.2

1972 9,638 12.3 1,550 13.9/2 yr. 7.0

1976 7,109 10 2,529 26.2/4 yr. 6.5

1978 6,096 9 1,013 14.2/2 yr. 7.1

1982 4,993 9 1,103 18.1/4 yr. 4.5

- oa -

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 85-4804

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff-Appellee,

and

ZANDRA PITTMAN, Etc., ET AL., Plaintiffs-Intervenors-Appellants,

versus

THE STATE OF MISSISSIPPI, ET AL., Defendants-Appellees,

and

HATTIESBURG MUNICIPAL SEPARATE

SCHOOL DISTRICT, Defendant-Intervenor-Appellee.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Southern District of Mississippi

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on this 4th day of March, 198 6, I served

two copies of the Reply Brief for Appellants in the above-cap

tioned matter upon counsel for the appellees by depositing the

same in the United States mail, first-class postage prepaid, ad

dressed as follows:

Moran M. Pope, Jr., Esq.

100 Professional Building

210 West Front Street

Hattiesburg, Mississippi 39401

Hon. Sara E. DeLoach

Assistant Attorney General

5th fl.. Justice Building

450 High Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39205

Mark L. Gross, Esq.

Appellate Section, Civil Rights Division

U.S. Department of Justice

Room 5718 Main Justice Building

10th and Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20530

Norman J. Chachkin