Gingles Plaintiffs' Objection to Pugh Plaintiffs' Motion for Class Certification

Public Court Documents

August 16, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Williams. Gingles Plaintiffs' Objection to Pugh Plaintiffs' Motion for Class Certification, 1982. 3a2e8aac-d992-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2743a3e8-a5fa-4b2e-a55c-797256df0e8d/gingles-plaintiffs-objection-to-pugh-plaintiffs-motion-for-class-certification. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

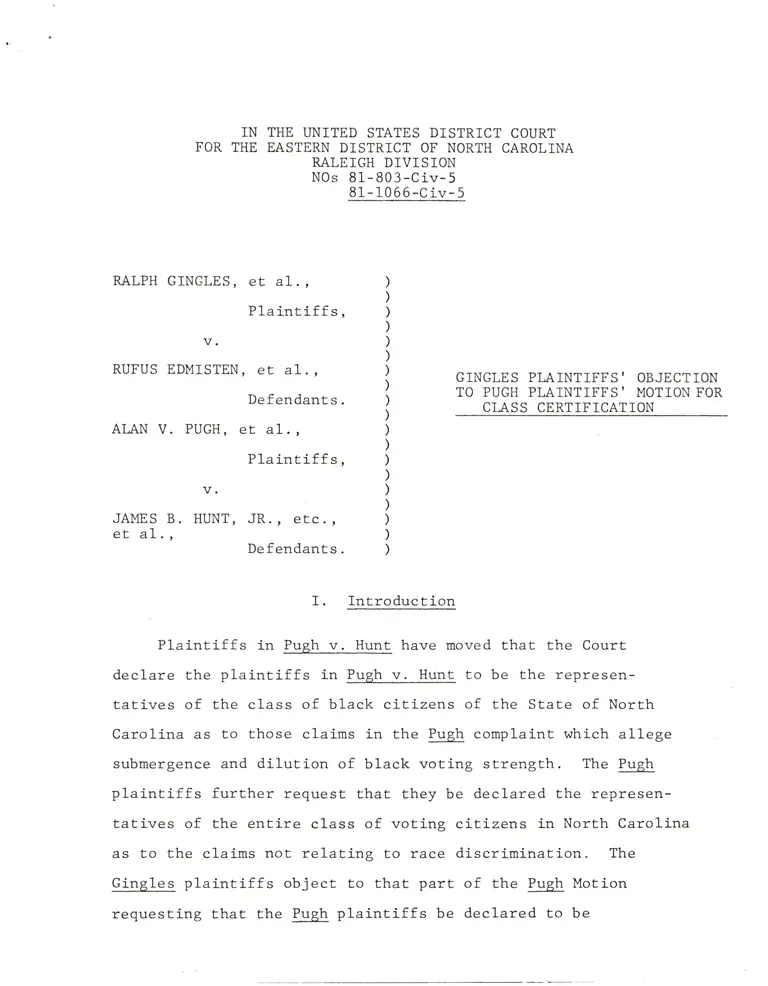

IN

FOR THE

RALPH GINGLES, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

v.

RUFUS EDMISTEN, €t aL.,

Defendants.

ALAN V. PUGH, et aL,,

Plaintiffs,

THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

RALEIGH DIVISION

NOs 81-803-Civ-5

81-1066-Civ-5

GINGLES PLAINTIFFS' OBJECT]ON

TO PUGH PLAINTIFFS, MOTION FOR

CIJ,SS CERTIFICATlON

v.

JAMES B. HUNT,

et al. ,

JR. , etc. ,

Defendants.

I. Introduction

Plaintiffs in Pugh v. Hunt have moved that the Court

declare the plaintiffs in Pugh v. Hunt to be the represen-

tatives of the class of black citizens of the State of North

Carolina as to those claims in the Pugh complaint which allege

submergence and dilution of black voting strength. The Pugh

plaintiffs further request that they be declared the represen-

tatives of the entire cl-ass of voting citizens in North Carolina

as to the claims not relating to race discrimination. The

Gingles plaintiffs object to that part of the Pugh Motion

requesting that the Pugh plaintiffs be declared to be

representatives of the class of black citizens of the

State of North Carolina.

II. Facts Relevant to this Motion

On September L6, 1981, the Gingles plaintiffs filed

a complaint a11eging, in general, that the method of aPpor-

tioning the North Carolina General Assembly and the specific

apportionment enacted in 1981 violate various statutory and

constitutional provisions designed to protect the right of

black citizens to use their votes effectively. This complaint

has been supplemented as the apportionment of the General

Assembly has subsequently been re-enacted or amended.

On or about November 25, 1981, the ljf€E plaintif f s f iled

their complaint alleging a variety of violations concerning

the apportionment of the North Carolina General- Assembly. Some

of these claims duplicated the Gingles claims and some did not.

The defendants in the two actions are substantially the same.

By order dated February 8, L982, the Court indicated that

the two actions should be consolidated. See also order of

JuLy 26 , L982.'

On April 2, Lg82, the Gingles plaintiffs moved to be

allowed to proceed as a class action on behalf of all black

residents of the State of North Carolina who are registered

to vote. The Gingles plaintiffs further agreed that they did

not object to the exclusion of the black named plaintiffs in

Pugh from the class certified in Gingles. Although the motion

and stipulation were served on attorneys for the Pugh plain-

tiffs, the B,rgfr plaintiffs did not request to be excLuded

from the Gingles class.

-2-

On or about April 15,

their class certification

On April 27, L982 the

Gingles as a class action

voters in North Carolina

L982 the Pugh plaintiffs filed

mot ion.

Court entered an Order certifying

on behalf of all registered black

To date the Court has not ruled on the PugE plaintiffs'

motion for class certification.

III. Argument

A fundamental part of our system of jurisprudence is

that the same party may not maintain two separate actions

against the same defendants arising out of the same transaction.

This principle should apply to plaintiff classes as well as

individual plaintiffs .

For example, principles of res judicata and merger of

claims provide LhaL the claim extinguished by a first judgment

"includes all rights of the plaintiff to remedies against the

defendant with respect to all or any part of the transaction,

or series of connected transactions, out of which the action

arose." Restatement Second of Judgments, 1981, S24. See also

Wright &Mi11er, 18 Federal Practice and Procedure S4407 at 55.

The doctrine of res judicata bars not only those claims

which actually have been litigated but also those which should

or might have been. See Wright & Mil1er, 18 Federal Practice

Procedure S4404. This preclusive effect applies to claims

which involve different Lheories of law but which arise out of

the same transaction. Wright & Miller, 18 Federal Practice &

Procedure S441I at 86.

-3-

Finally, for purposes of res judicata, a member of a

class in a Rule 23(b) (2) class action is considered a party by

representation and is bound to the same extent as a named

party. Rule 23(c)(3), F.R.Civ.P.; see also Wright & Miller,

7A Federal Practice and Procedure 51789 at L79.

The Pugh plaintiffs have moved to represent essentially

the same class which has already been certified in Gingles v.

Edmisten. (The Pugh plaintiffs' proposed class includes all

black citizens whereas the Gingles class is limited to black

registered voters. ) The Pugh claims, while some include

different lega1 theories, clearly arise out of the same series

of transacLions as do the claims asserted in Gingles: the

method of apportionment of the North Carolina General Assembly.

By requesting that a second class be certified, the Pugh

plaintiffs are essentially asking the Court to a11ow the same

plaintiff class to maintain a second action against the same

defendants arising out of the same transaction.

I^lhile the doctrines of res judicata do not apply until a

judgment is entered in one case or the other, the principles of

avoiding the splitting of claims apply before a judgment is

entered as well as after. Furthermore, the effect of certifying

a class i4 Pugh would be to put that class in a very dangerous

situation. If for some reason a judgment is entered in one

action before it is entered in the other, or if one of the

actions is settled before the other is terminated, the claims

in the second action could be deemed to have been merged and

the class could be precluded from proceeding in the other

action. See Wright & Mil1er, supra at 54404.

-4-

In addition, the Court has already found that the

Gingles plaintiffs adequately represent the class with regard

to any racial discrimination resulting from the apportionment of the

General Assembly. It is difficult to determine what need there

is for the same people to be represented by a second set of

named plaintiffs.

Finally, the Pugh plaintiffs allege to represent the

class of all North Carolina voters as well as the class of all

black citizens of North Carolina. These two classes, by their

very nature, have divergent interests, and the furtherance of

the interests of the former may conflict with the interests of

the latter. This puts the apporpriateness and adequacy of

representation in question.

The Gingles plaintiffs, of course, do not object to the

exclusion of the named plaintiffs in Pugh from the class

already certified in Gingles. They are not attempting to

prevent the Pugh plaintiffs from proceeding as individuals.

However, allowing the Pugh plaintiffs to represent the same

people that the Gingles plaintiffs already represent will be

cumbersome, confusing, and duplicative and, in the long run,

it may deny the class effective representation.

Therefore, the Gingles plaintiffs request that the

Court:

1. Deny that part of the Pugh motion for class certi-

fication that requests certification of the class of black

citizens;

-5-

2. Limit any other class certified in Pugh to

representation only on claims not involving racial discri-

mination; and

3. All-ow those Pugh plaintif f s who are black the

opportunity to exclude themselves from the Gingles class

if they so desire; or

4. Alternatively, allow the named plaintiffs in

Gingles, as well as any other members of the Gingles class

who so desire; to exclude themselves from Ehe Pugh class.

This /( ary ot (?*t.V,-l- , Lg82.

/l

L/

Chambers, Ferguson, Watt, Wallas,

Adkins & Fuller, P.A.

Suite 730 East Independence Plaza

951 South Independence Boulevard

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

704/375-846r

JACK GREENBERG

NAPOLEON I,IILLIAMS

LANI GUINIER

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiff

LESLIE J. W

-6-