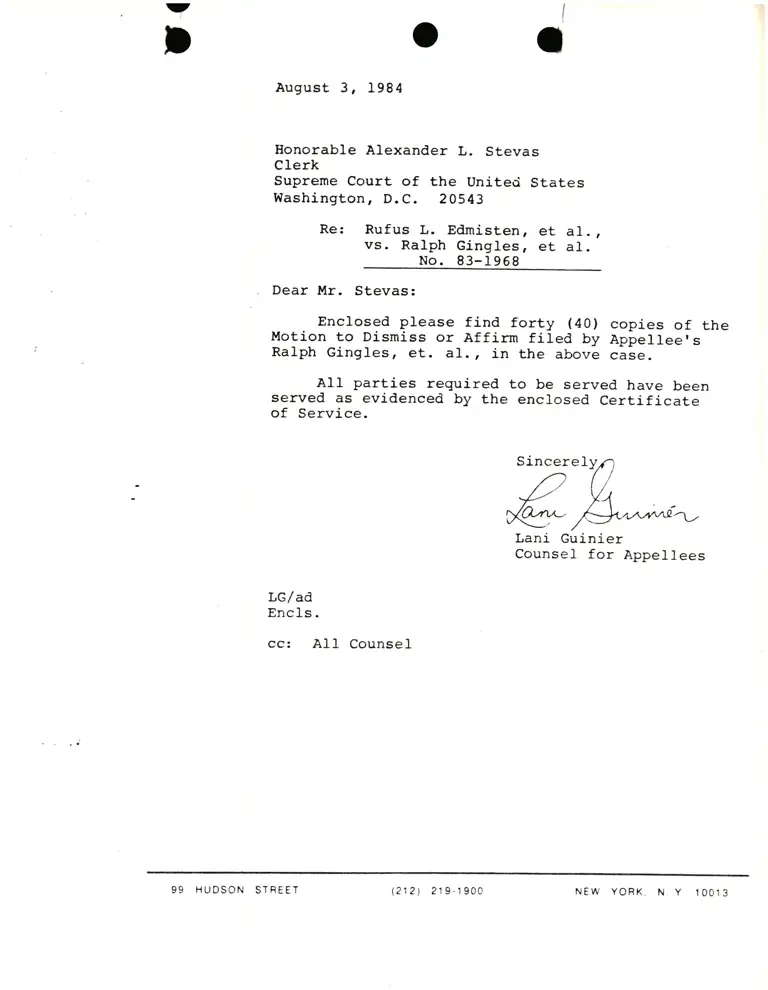

Correspondence from Guinier to Stevas

Public Court Documents

August 3, 1984

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Hardbacks, Briefs, and Trial Transcript. Correspondence from Guinier to Stevas, 1984. 2c6b8f96-d592-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/27863697-5cd9-4ab7-9606-a2e9f923fb6b/correspondence-from-guinier-to-stevas. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Y

)

l

e

August 3, 1984

Ilonorable Alexander L. Stevas

Clerk

Supreme Court of the Uniteci States

Washington, D.C. 20543

Re: Rufus L. Edmisten, et dI.,

vs. Ralph Gingles, €t aI.

No.83-19G8

Dear !1r. Stevas:

Enclosed please find forty (401 copies of theMotion to Dismiss or Affirm filed by Appellee's

Ralph Gingles, €t. d1., in the above clse.

A11 parties reguired to be served have been

served as evidenced by the enclosed Certificate

of Service.

Sincerely.

Lani Guinier

Counsel for Appellees

LGlad

EncIs.

cc: All Counsel

99 HUDSON STREET (212\ 219-1900 NEW YORK, N Y, 10013