Brief of Amici Curiae Brennan Center in Support of Appellants

Public Court Documents

1998

37 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Cromartie Hardbacks. Brief of Amici Curiae Brennan Center in Support of Appellants, 1998. a26b646d-d90e-f011-9989-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2833c8df-9e21-4c20-88ad-6e2dd230d634/brief-of-amici-curiae-brennan-center-in-support-of-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

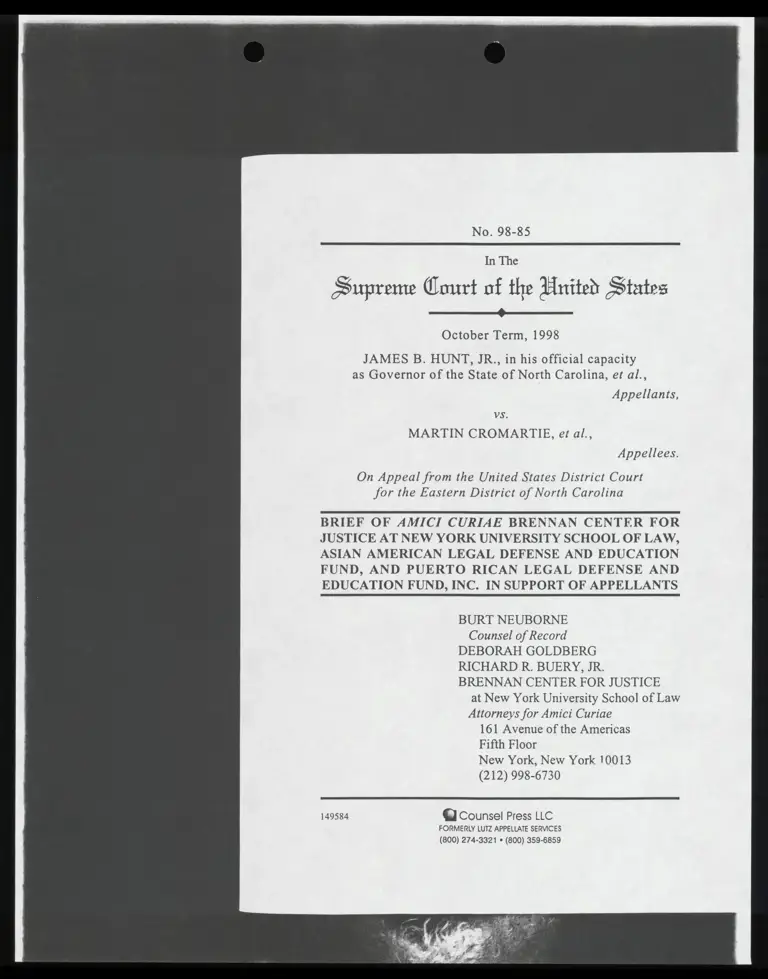

No. 98-85

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

4

October Term, 1998

JAMES B. HUNT, JR., in his official capacity

as Governor of the State of North Carolina, et al.,

Appellants,

VS.

MARTIN CROMARTIE, et al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of North Carolina

BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE BRENNAN CENTER FOR

JUSTICE AT NEW YORK UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW,

ASIAN AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATION

FUND, AND PUERTO RICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATION FUND, INC. IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANTS

BURT NEUBORNE

Counsel of Record

DEBORAH GOLDBERG

RICHARD R. BUERY, JR.

BRENNAN CENTER FOR JUSTICE

at New York University School of Law

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

161 Avenue of the Americas

Fifth Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 998-6730

149584 €J Counsel Press LLC

FORMERLY LUTZ APPELLATE SERVICES

(800) 274-3321 » (800) 359-6859

—

—

—

—

—

—

en.

—

—

—

—

e

e

t

—

r

e

BO.

P

E

N

S

E

8

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

C

p

—

—

ag

—

a

ec

A

e

e

e

~

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Table of Contents”. . .. 0. it. JL alm ine 1

Table of Cited Authorities"... .o. uu i dn 1v

Interests of Amici Curiae fouod 8. 5 said 1

Introduction and Summary of Argument ........... 2

Argument =. ol a RE SSE 5

I. Courts Deciding Shaw Claims Must Recognize

Plaintiffs’ Unusually “Demanding” Evidentiary

Burden. or de Te 5

A. Claims of Unconstitutional Gerrymandering

Under Shaw Require Proof That Race Was

the “Dominant and Controlling”

Consideration in Drawing District Lines.

SERRE aie IT CS eR ERR RE 5

B. Shaw Offers No Guidance to Courts

Deciding Whether Plaintiffs Have Carried

Their Burden. 20a iE 6

C. If the Court Declines to Reconsider Shaw,

the Court Should Provide a Workable

Framework for Shaw Actions That Preserves

Plaintiffs’ Demanding Evidentiary Burden.

i

Contents

The Court Should Impose a Demanding

Production Burden Before Allowing

District Courts to Infer a Predominantly

Racial Purpose From Circumstantial

Bvidence. ..............0 ced

a. Plaintiffs Should Be Required to

Present Compelling Evidence That

a Challenged District Flunks

Functional Test for Geographical

COMPACINESS......ocvscinrenricnivssntssne sire

b. Plaintiffs Should Also Be Required

to Present Compelling Evidence

That a Challenged District Seriously

Distorts the Region’s Racial

DeMOSIaPIICS. .cic.cvviiiiiccinnnsceisdionss

If Plaintiffs Satisfy Their Production

Burden, Defendants Must Produce

Evidence That Race Was Not the

Predominant Motive, with Plaintiffs

Retaining the Ultimate Burden of

Proving Unconstitutionality. .......

When Plaintiffs Cannot Carry Their

Burden of Proof, Courts Should Defer

to the Legislature’s Line-Drawing

Judgments, ... 00 C8. 0 0 Ae us

Page

10

14

Ji!

15

e

d

S

i

ii

Contents

II. The District Court Improperly Relieved Plaintiffs

Of Their Demanding Burden Of Proof. ......

A.

Conclusion

Applying the Appropriate Framework,

Plaintiffs Failed to Meet Their Substantial

Burden of Demonstrating That Race Was

North Carolina’s Predominant Purpose in

Redistriching, & .... .ai vd aini ives

1. Plaintiffs’ Circumstantial Evidence

Failed Even to Raise an Inference of

Discriminatory Purpose. ...........

Defendants Fully Rebutted Any

Inference That Race Was the

Predominant Factor in the Districting

PIOCESS. coh. visions ies sins in

The District Court Relieved Plaintiffs of

Their Difficult Burden of Proof By Relying

on Impact, Rather Than Intent, to Find a

Constitutional Violation. ..............

NE a set SR Re a TE TRY ee VES Wl Ie ee HE A oe el 7 Ct a Ty a ae

Page

16

17

17

19

24

28

Iv

TABLE OF CITED AUTHORITIES

P

Cases: fae

Abrams v. Johnson, 117 S. Ct. 1925 (1997) ...... 2:5.21.23

Agosto v. INS, 436 U.S. 748 (1978)... .. ein iin 27

Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc., 477 U.S. 242 (1986)

I end So Dell, oe, SESS aw EES Se GE 235,26

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Dev. Corp.,

429 11.8. 25203977)... sc sae a ae se 6

Baker vi Carr,369 U.S. 136 (1962) ............ons 16

Bush v. Vera, 517 1U.8.952(1996) .... 2,5,7,13,20,22,23

Celotex Corp. v. Catrett, 477 U.S. 317 (1986) ....... 25

Chen v. City of Houston, 1998 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 9860

(SD. Tex. 1998)... oui us iain vb i diet 10

Colegrove v. Green, 328 U.S. 549 (1946). .......... 16

Crawford-el v. Britton, 118 S. Ct. 1584 (1998) ...... 25,27

Cromartie v. Hunt, No. 4:96-CV-104-BO (3) (E.D.N.C.

April’l4, 1998) ‘Lui, caval als 17, 18,21,22, 23,25

Davis v. Bandemer, 478 U.S. 109 (1986) ........... 15,16

DeWitt v. Wilson, 856 F. Supp. 1409 (E.D. Cal. 1994),

aff dnem., 515 U.S. HI0(1998) ........ van v, 10

2.

ta

n

—

—

L

a

—

E

a

A

Table of Cited Authorities |

Page

Eastman Kodak Co. v. Image Tech. Servs., Inc., 504 U.S.

ASE(1902), iv . teitit errs sr Nk a Se rw nag 26

Gingles v. Edmisten, 590 F. Supp. 345 (E.D.N.C. 1984),

aff'd in part and rev'd in part sub nom., Thornburg v.

Gingles, 478 U.8.30(1986) .........c.csevvsan 22

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960) ....... 6, 16, 24

Holder v. Hall, 3121.8. 874(1994) ....... .convnns 15

Wineis v. Krull, 430 U.S. 340(1987) .. ....c...0u. vi 9

Johnson v. Meltzer, 134 F.3d 1393 (9th Cir. 1998) ... 27

Johnson v. Miller, 922 F. Supp. 1556 (S.D. Ga. 1995)

TE ea Ce ae PO EN SEE ENS 23

King v. State Bd. of Elections, 979 F. Supp. 619 (1997),

aff'd mem., 118 S. Ct. 877 (1998), ............:. 28

Lawyer v. Department of Justice, 117 S. Ct. 2186 (1997)

ee et Sw hone bY A re a ay 2.5,18,23

Miller v. Johnson, 515 U.S. 900 (1995)

i ena a ou lite 3 2.5.6,7,9,14. 15,20, 25,26

Prosser v. Elections Bd., 793 F. Supp. 859 (1992) ... 11,12

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964) ............. 15

Vi

Table of Cited Authorities

Page

Shaw v. Hunt, 517 U.S. 899 (1996) ......... 2.5,6,8,16,20

Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. 630 (1993) ................ passim

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986) .......... 16, 22

United States v. Hays, 515 U.S. 737 (1995). ........ 2

Wesberry v. Sanders, 376 U.S. 1 (1964) ............ 15

White Motor Co. v. United States, 372 U.S. 253 (1963)

Rn rc RE RC Re Se aa SP 27

Wilsonv. Eu, 823P.24d 545(Cal. 1992) ............. 10

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886) ........... 6

Rules:

Ped. R Civ. P.SO(E) ..... 0 dvinriaiienis Shainin 25

Supreme Court RUl€ 37.6 .......... conve icine 1

Other Authorities:

T. Alexander Aleinikoff & Samuel Issacharoff, Race and

Redistricting: Drawing Constitutional Lines after

Shaw v. Reno, 92 Mich. L. Rev. 588 (1993) ...... 12

Michael Barone & Grant Ujifusa, The Almanac of

American Politics 1998(1998) ......cevceuvi.. 21

~

R

e

t

e

RO

c

a

s

e

i

n

oomre

ianer

sls

e

r

—

—

—

—

—

—

Vil

Table of Cited Authorities

Keith J. Bybee, Mistaken Identity: The Supreme Court

and the Politics of Minority Representation (1998)

| BR BR a COT IS Nl SE ER TE Te RT NN SY HE NE A Sh MR Se ve TR i Sa Tl ye ST TR A SR he

Page

15

Bruce Cain, The Reapportionment Puzzle (1984) .. 11, 12,13

Robert G. Dixon, Jr., Fair Criteria and Procedures for

Establishing Legislative Districts, in Representation

and Redistricting Issues (Bernard Grofman et al. eds.,

6000 ORR Se Sr Se le DY

Bernard Grofman, Criteria for Districting: A Social

Science Perspective, 33 U.C.L.A. L. Rev. 77 (1985)

oe oilate wislinoel we eine ein elie nerelets sien elieie ie wie eee 8 erie eee a

Paul A. Jargowsky, Metropolitan Restructuring and

Urban Policy, 8 Stan. L. & Pol’y Rev. 47 (1997)

| Ae, ot Gr NE HE BR OTS SE They BEE UES BRT REY SSE WU ol eG TNE GS TH SAYRE URE SRM Th i A Ra a ger JE I i Ne

Steven A. Light, Too (Color)Blind to See: The Voting

Rights Act of 1965 and the Rehnquist Court, 8 Geo.

Mason U. CiveRis. LJ. 1(1997) ..ccoinnsiiiiniisa

Daniel H. Lowenstein & Jonathan Steinberg, The Quest

for Legislative Districting in the Public Interest:

Elusive or Illusory?, 33 U.C.L.A. L. Rev. 1 (1985)

Cte TOE 4 EY US eT Sy BS SR SR dW GY SF SE AE He eal Wh ACIS JR we JEG RI Sa Re BE SAA eT She Lo Je i

Stephen J. Malone, Recognizing Communities of Interest

in a Legislative Apportionment Plan, 83 Va. L. Rev.

UY RELL YL SRR RR ell Et MORE SR EN

16

13

12

11

13,16

viii

Table of Cited Authorities

Hanna Fenichel Pitkin, The Concept of Representation

G4 YEAR in ER I CE

Richard H. Pildes & Richard G. Niemi, Expressive

Harms, “Bizarre Districts,” and Voting Rights:

Evaluating Election-District Appearances After Shaw

v. Reno, 92 Mich. L. Rev. 483 (1993)

10B Wright, Miller & Kane, Federal Practice &

Procedure: Civil 3d § 2730 (1998) ® os so oo ov es 8 8 es oe wu

Page

15

11

I

S

S

.

.

.

INTERESTS OF AMICI CURIAE

With the consent of the parties, the Brennan Center for

Justice at New York University School of Law; the Asian

American Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc.; and the

Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc. submit

this brief amici curiae in support of Defendants-Appellants.'

Letters of consent are on file with this Court.

The Brennan Center for Justice at New York University

School of Law is a nonpartisan institute dedicated to a vision

of inclusive and effective democracy. The Center unites the

intellectual resources of the academy with the pragmatic

expertise of the bar in an effort to assist both courts and

legislatures in developing practical solutions to difficult

problems in areas of special concern to Justice William

Brennan, Jr. To that end, the Center has created a Democracy

Program, which undertakes projects that promote equal

representation and other core ideals of democratic government.

The Center takes an interest in this case because of its

implications for the effective representation of minority

populations and submits this brief in the hope of providing a

workable framework for deciding Shaw actions.

The Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund

(“AALDEF”), founded in 1974, is a nonprofit organization that

protects the legal rights of Asian Americans. AALDEF has

represented the Asian American community in numerous cases

and administrative proceedings under the Voting Rights Act.

The Court’s decision in Shaw v. Reno has been interpreted in

ways that have limited the rights of Asian Americans to

1. Pursuant to Supreme Court Rule 37.6, amici state that no counsel

for a party authored this brief in whole or in part; and that no person or

entity, other than amici, has contributed monetarily to the preparation

and submission of this brief.

2

participate fully in the political process. The decision below is

another clear example of how the distorting lens of Shaw has

been used to depict the permissive consideration of communities

of interest as the impermissible consideration of race. AALDEF

takes an interest in this case because the continued viability of

electoral participation is threatened by this misapplication of

the Equal Protection Clause.

The Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc.

(“PRLDEF”) is a national civil rights organization that exists

to ensure that every Puerto Rican as well as other Latinos are

guaranteed equal opportunities to succeed. Through litigation,

advocacy, and education, PRLDEF has initiated hundreds of

cases to combat discrimination in significant areas such as

voting, education, housing, and language rights. It is of

paramount importance to PRLDEF that its constituency be

afforded full access to the political process. PRLDEF takes an

interest in this case because the district court’s interpretation

of Shaw v. Reno, if allowed to stand, threatens to deny

PRLDEF’s constituency the opportunity to participate fully and

effectively in the political process by joining with non-Latinos

in common communities of interest.

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Under Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. 630 (1993) (“Shaw I’), and

its progeny,’ efforts to enhance the political power of racial

minorities by using race as the dominant and controlling factor

in creating “majority-minority” legislative districts violate the

Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. While

2. See, e.g., Lawyer v. Department of Justice, 117 S. Ct. 2186

(1997); Abrams v. Johnson, 117 S. Ct. 1925 (1997); Bush v. Vera, 517

U.S. 952 (1996) (plurality opinion); Shaw v. Hunt, 517 U.S. 899 (1996);

Miller v. Johnson, 515 U.S. 900 (1995); United States v. Hays, 515 U.S.

737 (1995).

amici share the Shaw I Court’s aspiration for a nation in which

race does not play a divisive role, amici fear that Shaw Iunfairly

denies minority voters the opportunity to organize themselves

as a community sharing actual interests in the real world of

North Carolina politics.

Whatever the wisdom of Shaw I, however, this case goes

far beyond outlawing race as a permissible community of

interest. This case casts doubt on the ability of North Carolina

to draw district lines that recognize non-racial communities of

interest, such as those linked by political affiliation, inner-city

residence, and proximity to transportation corridors, solely

because in today’s America those communities of interest often

correlate with membership in a racial minority.

The district court below summarily invalidated a non-

majority-minority congressional district, ignoring and

mischaracterizing sworn assertions that its shape and racial

composition were traceable not to an overriding concern with

race but to a desire to recognize political affiliation, inner city

residence, and residence in close proximity to a highway as

legitimate non-racial communities of interest warranting

representation in Congress. If the district court’s decision is

affirmed, minority voters will be doubly harmed. Not only will

Shaw I deprive them of the ability to be linked by an immensely

important community of interest — membership in a minority

race — but, alone among American voters, they will be denied

the ability to be linked by crucial non-racial communities of

interest, merely because those interests often overlap with race.

Surely, the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments were not

intended to create such a second-class political status.

To avoid this unfair and unintended consequence, this Court

should reaffirm that Shaw I imposes an extremely demanding

burden on plaintiffs claiming that a state has segregated voters

4

on the basis of race in violation of the Equal Protection Clause.

Plaintiffs in a Shaw I action cannot rest on evidence that race

was one of several motivating factors in choosing district lines

but instead must prove that race for its own sake was the state’s

“dominant and controlling” rationale in drawing district lines

before strict scrutiny will apply. See Point [.A.

In Point I.B., amici suggest that Shaw I and its progeny do

not provide adequate guidance to courts attempting to apply

this standard and should therefore be reconsidered. But in the

event that the Court adheres to Shaw I, amici propose an

analytical framework that would allow courts to decipher the

legislature’s predominant intent, while preserving Shaw I's

demanding burden of proof. See Point I.C.

Amici demonstrate in Point II that, under this framework,

Plaintiffs could not carry their demanding burden. Plaintiffs’

evidence of District Twelve’s shape and racial composition was

insufficient to establish even a prima facie case of liability.

And even if Plaintiffs had raised an inference of impermissible

racial intent, Defendants fully rebutted that inference with

unchallenged proof that race was not the state’s predominant

consideration. That unrebutted evidence shows that North

Carolina drew district boundaries with the hope of providing

representation for actual communities of interest defined by

voting patterns, inner-city residence, and proximity to Interstate

85. Inexplicably, the district court ignored or mischaracterized

most of this evidence. See Point IL. A.

Finally, as amici demonstrate in Point II.B., the district

court erred in denying Defendants’ motion for summary

judgment and in granting Plaintiffs’ motion for summary

judgment. In so doing, the court effectively shifted the burden

of persuasion to Defendants and transformed Shaw I’s intent

FR

v

—

i

M

e

e

—

e

a

t

=

5

standard into a far less burdensome impact test. The Court should

therefore reverse the decision below, or at the very least vacate

and remand the case for fact-finding on the issue of intent and, if

intent is proven, for application of strict scrutiny.

ARGUMENT

I.

COURTS DECIDING SHAW CLAIMS MUST

RECOGNIZE PLAINTIFFS’ UNUSUALLY

“DEMANDING” EVIDENTIARY BURDEN.

A. Claims of Unconstitutional Gerrymandering Under Shaw

Require Proof That Race Was the “Dominant and

Controlling” Consideration in Drawing District Lines.

Plaintiffs in an action under Shaw I face an extremely

“demanding” evidentiary burden. Miller v. Johnson, 515 U.S. 900,

928 (1995) (O’Connor, J., concurring). They cannot trigger strict

scrutiny merely by showing that a racially discriminatory purpose

was one factor in government decision-making. Rather, plaintiffs

must show that race, standing alone, was the State’s “dominant

and controlling” consideration. Shaw v. Hunt, 517 U.S. 899, 905

(1996) (“Shaw II) (citations omitted); see Miller, 515 U.S. at 916

(plaintiffs must prove “race was the predominant factor . . . [by

showing] that the legislature subordinated traditional race neutral

districting principles, including but not limited to compactness,

contiguity, respect for political subdivisions or communities

defined by actual shared interests’); Bush v. Vera, 517 U.S. 952,

959 (1996) (plurality opinion).

Under this demanding standard, mere evidence of the racial

impact of districting cannot sustain a Shaw I claim.® “In the rare

3. See Lawyer v. Department of Justice, 117 S. Ct. 2186, 2195

(1997) (“[W]e have never suggested that the percentage of black residents

(Cont’d)

6

case,” the effects of governmental action may be so

overwhelming that the racial purpose of the action is clear.

Miller, 515 U.S. at 913 (citing Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S.

339 (1960), and Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886)). But

“[1]n the absence of a pattern as stark as those in Yick Wo or

Gomillion, ‘impact alone is not determinative, and the Court

must look to other evidence of race-based decisionmaking.’ ”

Miller, 515 U.S. at 914 (quoting Arlington Heights v.

Metropolitan Housing Dev. Corp., 429 U.S. 252, 266 (1977)).

That evidence must command the conclusion that the legislature

elevated race above all other considerations in drawing a

challenged district’s lines.*

B. Shaw Offers No Guidance to Courts Deciding Whether

Plaintiffs Have Carried Their Burden.

Legislatures drawing a district’s lines, and courts reviewing

apportionment challenges under Shaw I, need a standard that

clearly specifies when race may be legitimately considered.

Unfortunately, Shaw I and its progeny create an unstable legal

standard in a context that cries out for predictability. On the

one hand, states are permitted to redistrict “with consciousness

(Cont’d)

in a district may not exceed the percentage of black residents in any of

the counties from which the district is created, and have never recognized

similar racial composition of different political districts as being

necessary to avoid an inference of racial gerrymandering ...."”).

4. In this regard, North Carolina’s awareness that its districting

program would place a substantial black minority in District Twelve

does not render the district constitutionally suspect. See Shaw II, 517

U.S. at 905 (“[A] legislature may be conscious of the voters’ races

without using race as a basis for assigning voters to districts.”); Miller,

515 U.S. at 916 (“Redistricting legislatures will . .. almost always be

aware of racial demographics; but it does not follow that race

predominates in the redistricting process.”).

7

of race,” Vera, 517 U.S. at 958 (plurality opinion); Miller, 515

U.S. at 916, and indeed must do so in order to avoid running

afoul of the Voting Rights Act, see Vera, 517 U.S. at 991-92

(O’Connor, J., concurring). On the other hand, race may not be

“the predominant factor motivating the legislature’s decision.”

Miller, 515 U.S. at 916. Legislatures are therefore left with no

practical guidance as to where to draw the line between

permissible and impermissible uses of race.

For that reason alone, the Shaw line of cases should be

reconsidered. The razor-thin distinctions between being aware

of race, being motivated by race, and more importantly, being

predominantly motivated by race, are so ephemeral that

resolution of such questions may well be beyond the

competence not only of legislatures but of courts. See Miller,

515 U.S. at 916 (“The distinction between being aware of racial

considerations and being motivated by them may be difficult

to make.”).

Shaw I, therefore, places both state legislatures and district

courts in a quandary. Without concrete guidance as to how and

when race may be considered, and faced with significant

pressure both to consider race and not to consider race, states

may be forced to cede their redistricting responsibilities to the

unpredictable fact-finding procedures of the federal courts. But

the Shaw cases offer the courts no better idea about how to

distinguish unconstitutional districts. For this reason, amici urge

the Court to reconsider the continued propriety of Shaw I.

C. If the Court Declines to Reconsider Shaw, the Court

Should Provide a Workable Framework for Shaw

Actions That Preserves Plaintiffs’ Demanding

Evidentiary Burden.

Shaw I creates an unmanageable standard of liability,

requiring a quixotic search for a “predominant” legislative

motive that may pose insuperable practical problems for

conscientious fact-finders. If this Court remains committed to

Shaw I, however, the Court must provide district courts with

precise guidance as to how to resolve the difficult factual

question of whether race was the controlling factor in drawing

district lines. Moreover, to ensure that district courts do not

simply presume unconstitutionality when faced with districts

they consider “oddly shaped” or “too black,” the framework

this Court provides must preserve the demanding burden of

proof imposed on Shaw I plaintiffs.

To achieve these ends, the Court might consider the

following framework: In the absence of direct evidence that

the state was predominantly motivated by race, plaintiffs would

be required to provide compelling circumstantial evidence that

the challenged district both flunked a functional compactness

test and seriously distorted racial demographics in order to raise

an inference that race dominated the districting process. If

plaintiffs provided such powerful circumstantial evidence, the

production burden would then shift to defendants to offer

legitimate nondiscriminatory reasons for district boundaries.

Defendants’ production of sworn evidence that non-racial

considerations dominated the districting process would shift

the production burden back to plaintiffs. Whether plaintiffs were

able to establish a prima facie case, or to rebut the state’s

evidence would, therefore, be questions of law for the court,

since they would be questions about satisfaction of the

production burden. At all times, the ultimate and demanding

burden of persuasion on the issue of predominant racial purpose

would remain with plaintiffs. See Abrams v. Johnson, 117 S.

Ct. 1925, 1931 (1997); Shaw II, 517 U.S. at 905.

1. The Court Should Impose a Demanding Producti n

Burden Before Allowing District Courts to Infer a

Predominantly Racial Purpose From Circumstantial

Evidence.

For three reasons, courts should require Shaw I plaintiffs

to meet a demanding production burden before inferring a

predominantly racial purpose from merely circumstantial

evidence. First, this Court has already held that plaintiffs face

a demanding burden of persuasion in Shaw I actions. Plaintiffs

should therefore face a significant burden of production before

an inference of unconstitutionality may be raised. See Miller,

515 U.S. at 916-17 (noting that plaintiffs’ “evidentiary difficulty

... requires courts to exercise extraordinary caution” before

allowing Shaw I claims to go forward). Second, repeated judicial

interference in congressional districting wreaks havoc on state

democratic processes. Judges should demand clear evidence

of a Shaw I violation before allowing a State to be dragged into

court. See id. at 916-17 (“[C]ourts must . . . recognize . . . the

intrusive potential of judicial intervention into the legislative

realm, when assessing . . . the adequacy of a plaintiff’s showing

at the various stages of litigation and determining whether to

permit discovery or trial to proceed.”). Third, “the presumption

of good faith that must be accorded legislative enactments”

weighs in favor of imposing a substantial burden of production.

Id. at 916; see, e.g., Illinois v. Krull, 480 U.S. 340, 351 (1987)

(legislatures are presumed to act in accord with the

Constitution).

In a Shaw I action, plaintiffs would carry their burden of

production, and thereby raise an inference of racial

gerrymandering, only if they satisfied two tests. First, plaintiffs

would have to make a compelling showing that the challenged

district failed a functional test for geographical compactness.

Second, they would have to demonstrate that the racial

10

demographics of the district were seriously distorted by

comparison with those of neighboring districts. The evidence

would constitute a prima facie case under Shaw I if, left

unrebutted, it would permit a reasonable fact-finder to conclude

that the State completely subordinated race-neutral districting

criteria to race. Whether the proffered evidence sufficed would

be a question of law for the court.

a. Plaintiffs Should Be Required to Present

Compelling Evidence That a Challenged

District Flunks a Functional Test for

Geographical Compactness.

As a threshold matter, Shaw I plaintiffs should be required

to present compelling evidence that a challenged district fails

a functional test for geographical compactness. Functional

compactness is best understood as “ ‘the presence or absence

of a sense of community made possible by open lines of access

and communication.” ” DeWitt v. Wilson, 856 F. Supp. 1409,

1413 (E.D. Cal. 1994) (quoting Wilson v. Eu, 823 P.2d 545,

549 (Cal. 1992)), aff'd mem., 515 U.S. 1170 (1995); see Chen

v. City of Houston, 1998 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 9860, *33, *36 (S.D.

Tex. 1998) (same). A functional approach thus measures the

geographical compactness of a district based on such relevant

indicia as actual road travel-time across the district and the

existence of open lines of access and communication — the

things that actually foster communities of interest in a region

and facilitate interaction between representatives and

constituents.

The functional test generally makes more sense in

contemporary times than the traditional aesthetic and physical

measures reflected in tests for “dispersion” and “perimeter”

compactness. Measures of dispersion and perimeter

compactness rest on the notion that the perfect district is

11

aesthetically pleasing and has “a regular, simple shape, usually

a circle,” Richard H. Pildes & Richard G. Niemi, Expressive

Harms, “Bizarre Districts,” and Voting Rights: Evaluating

Election-District Appearances After Shaw v. Reno, 92 Mich.

L. Rev. 483, 554 (1993), and that people who live in close

physical proximity are likely to share interests worthy of

common representation, see id. at 501 (“A principal aim of

territorial districting is to facilitate the representation and

interests of political communities. Compact districting is at best

a proxy for this goal . ...”). When travel and communication

over long distances were difficult, people who lived close to

one another might well have been presumed to share common

interests, and legislatures and courts might reasonably have

assumed that the best way to ensure representation based on

actual interests was to minimize physical distance between

people in a single district. But in the modern world, “there 1s

no necessary logical relation between [dispersion and perimeter]

compactness” and the representation of shared interests. Bruce

Cain, The Reapportionment Puzzle 43 (1984). Nor is there

necessarily an empirical relationship between the two. See id.

at 43-50; Steven A. Light, Too (Color)Blind to See: The Voting

Rights Act of 1965 and the Rehnquist Court, 8 Geo. Mason U.

Civ. Rts. L.J. 1, 34 (1997) (criticizing Miller for presuming

that “physical proximity ... is a legitimate proxy for real

communities of interest”).?

Indeed, strict adherence to physical proximity can be an

impediment to providing representation to genuine communities

5. See also Prosser v. Elections Bd., 793 F. Supp. 859, 863 (1992)

(per curiam) (recognizing imperfect correlation between “geographical

propinquity and community of interests”); Stephen J. Malone,

Recognizing Communities of Interest in a Legislative Apportionment

Plan, 83 Va. L. Rev. 461, 475 (1997) (describing “imperfect nexus

between geographically compact districts and communities of interest”).

12

of interest “because there are real-life situations in which one

does not have to travel very far ... before encountering

[differences in] attitudes.” Cain, supra, at 39; see Prosser v.

Elections Bd., 793 F. Supp. 859, 863 (1992) (per curiam). The

world 1s getting smaller, and communities of interest may

legitimately cross street blocks, neighborhoods, and cities in

ways that would have been unthinkable just decades ago.

[T]he focus on geographic proximity in districting

developed in a time when communities were smaller

and transportation was more difficult. The concept

of geographical coherence may be far less relevant

in defining primary communities of interest in

today’s society. The census demographic data reveal

a highly fluid society in which changes of residence

are far from unexpected, and in which the growth

of “exurbs” — defined by proximity to the highway

networks — have replaced any pre-existing sense

of geographic coherence.

T. Alexander Aleinikoff & Samuel Issacharoff, Race and

Redistricting: Drawing Constitutional Lines after Shaw v.

Reno, 92 Mich. L. Rev. 588, 637 (1993) (internal quotation

marks omitted); Paul A. Jargowsky, Metropolitan Restructuring

and Urban Policy, 8 Stan. L. & Pol’y Rev. 47, 48 (1997)

(discussing decentralization of urban areas facilitated by “high-

speed, high-volume networked communications”).

In addition, the presumed correlation between physical

proximity of district residents and ease of access to legislators,

see Prosser, 793 F. Supp. at 863 (“Compactness and contiguity

. .. reduce travel time and costs, and therefore make it easier

for candidates. . . to campaign. . . and once elected to maintain

close and continuing contact with the people they represent.”),

may have been valid in the past, but there are fewer reasons to

have faith in the connection now.

13

The popular concern for compactness ... is the

legacy of earlier periods in history when

communications and transportation were difficult.

Compactness guaranteed that representatives could

meet with their constituents with relative ease. . . .

This consideration is not as relevant as it once was.

Travel over large and sprawling areas is no longer a

formidable task.

Cain, supra, at 32; see Daniel H. Lowenstein & Jonathan

Steinberg, The Quest for Legislative Districting in the Public

Interest: Elusive or Illusory?,33 U.C.L.A.L. Rev. 1,22 (1985).

In sum, courts deciding whether Shaw I plaintiffs have

produced compelling evidence that a district is not

geographically compact should rely on functional measures

rather than on aesthetic or physical criteria.’ In today’s world,

functional measures do the job that shape was supposed to do

—only they do it better. Plaintiffs therefore should not be able

to raise an inference of purposeful discrimination with nothing

more than evidence of a district’s irregular shape. A prima facie

Shaw I case should require proof that a challenged district fails

a functional test for compactness.’

6. States are not constitutionally required to draw districts that are

aesthetically pleasing. See Vera, 517 U.S. at 962 (plurality opinion);

Shaw 1, 509 U.S. at 645-46.

7. See Bernard Grofman, Criteria for Districting: A Social Science

Perspective, 33 U.C.L.A. L. Rev. 77, 89 (1985) (“[T]he usefulness of

requiring that districts be compact has been vastly overrated.”); Cain,

supra, at 148 (distorted shapes do not necessarily indicate

gerrymandering and “the observer has to look closely to see what the

intent was”).

14

b. Plaintiffs Should Also Be Required to Present

Compelling Evidence That a Challenged

District Seriously Distorts the Region’s Racial

Demographics.

In addition to providing compelling evidence that a district

is not functionally compact, a plaintiff seeking to raise a Shaw

I claim solely on the basis of circumstantial evidence should

be required to prove that a challenged district seriously distorts

the racial demographics of the region. Where, as here, the

challenged district is not majority-minority, that burden should

be all the more difficult to meet. Indeed, the fact that a

congressional district is not majority-minority might well

support a presumption that race did not dominate legislative

decision-making. Plaintiffs who could not overcome such a

presumption would not establish a prima facie case under the

framework proposed here.

2. If Plaintiffs Satisfy Their Production Burden,

Defendants Must Produce Evidence That Race Was

Not the Predominant Motive, with Plaintiffs

Retaining the Ultimate Burden of Proving

Unconstitutionality.

If plaintiffs were able to meet the difficult burden of raising

an inference of Shaw I liability, the state would be required to

proffer race-neutral reasons for the district’s lines. The universe

of legitimate rationales is quite large and includes

“compactness, contiguity, respect for political subdivisions or

communities defined by actual shared interests.” Miller, 515

U.S. at 916. Producing such evidence would be sufficient to

rebut the inference of unconstitutionality established by

plaintiffs’ evidence and shift the production burden back to

plaintiffs. With plaintiffs’ and defendants’ positions so framed,

plaintiffs would then attempt to meet their demanding burden

13

of proving that racial considerations dominated the districting

process.

3. When Plaintiffs Cannot Carry Their Burden of

Proof, Courts Should Defer to the Legislature’s

Line-Drawing Judgments.

If Plaintiffs cannot meet the difficult burden of proving

that race was the predominant legislative motive under the

framework recommended here, the judiciary must defer to North

Carolina’s judgments about how best to structure its democracy.

A state’s ultimate goal in legislative apportionment is to provide

effective political representation of the interests of its citizens.

In doing so, a state necessarily makes difficult and contested

political judgments as to what interests should be represented

in Congress, and how.® For this reason, “[e]lectoral districting

is a most difficult subject for legislatures, and . .. the States

must have discretion to exercise the political judgment

necessary to balance competing interests.” Miller, 515 U.S. at

915; see Davis v. Bandemer, 478 U.S. 109, 147 (1986)

(O’Connor, J., concurring) (“Federal courts will have no

alternative but to attempt to recreate the complex process of

legislative apportionment in the context of adversary litigation

in order to reconcile the competing claims of political, religious,

8. The question of how best to represent the interests of citizens is

the subject of considerable and reasonable debate. See, e.g., Keith J.

Bybee, Mistaken Identity: The Supreme Court and the Politics of

Minority Representation 36-50 (1998); Malone, supra, at 475-92; Hanna

Fenichel Pitkin, The Concept of Representation (1967). Thus, members

of this Court have criticized judicial interference in matters of legislative

apportionment on the ground that it requires courts to make theoretical

judgments concerning the nature of political representation — judgments

that courts are often ill-equipped to make. See, e.g., Holder v. Hall, 512

U.S. 874, 891-903 (1994) (Thomas, J., concurring); Reynolds v. Sims,

377 U.S. 533, 589 (1964) (Harlan, J., dissenting); Wesberry v. Sanders,

376 U.S. 1, 30 (1964) (Harlan, J., dissenting).

16

ethnic, racial, occupational, and socioeconomic groups.”);

Lowenstein & Steinberg, supra, at 26-38, 73-75 (congressional

districting is inherently political and should be free from

excessive judicial interference).’

Moreover, judicial interference seems especially

inappropriate where, as here, the majority “attempt[s] to enable

the minority to participate more effectively in the process of

democratic government,” Shaw II, 517 U.S. at 918 (Stevens,

J., dissenting), rather than to exclude minorities from

democratic participation. In these cases, there is little reason

to believe that democratic processes are being

unconstitutionally subverted and thus no need for courts to enter

the “political thicket” of legislative apportionment. Colegrove

v. Green, 328 U.S. 549, 556 (1946).

IL.

THE DISTRICT COURT IMPROPERLY RELIEVED

PLAINTIFFS OF THEIR DEMANDING BURDEN

OF PROOF.

Within the framework recommended here, Plaintiffs failed

to make even a prima facie showing that race was the

9. Of course, federal law limits the States’ districting authority in

important ways. See, e.g., Davis, 478 U.S. at 113 (holding that claims

of partisan gerrymandering are justiciable); Thornburg v. Gingles, 478

U.S. 30 (1986) (prohibiting vote dilution); Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186

(1962) (requiring equality of district population); Gomillion, 364 U.S.

at 341 (prohibiting redrawing district lines to intentionally deprive

citizens of right to vote on basis of race). But these rules leave the states

with considerable leeway. For example, even after application of the

“one person one vote” principle, hundreds of districting options remain

available to the states. See Robert G. Dixon, Jr., Fair Criteria and

Procedures for Establishing Legislative Districts, in Representation and

Redistricting Issues 7-8 (Bernard Grofman et al. eds., 1982).

17

predominant factor motivating the State’s districting decision.

Moreover, even assuming that their weak evidence raised an

inference of unconstitutionality, North Carolina fully countered

that inference with unchallenged evidence that non-racial

motives dominated the State’s districting process. Given the

unrebutted evidence of dominant non-racial motives, the district

court should have awarded summary judgment to Defendants.

The district court thus clearly erred in granting summary

judgment to Plaintiffs.

A. Applying the Appropriate Framework, Plaintiffs Failed

to Meet Their Substantial Burden of Demonstrating

That Race Was North Carolina’s Predominant Purpose

in Redistricting.

1. Plaintiffs’ Circumstantial Evidence Failed Even to

Raise an Inference of Discriminatory Purpose.

In granting summary judgment to Plaintiffs, the district

court improperly relied on weak circumstantial evidence of

insufficient geographic compactness and distorted

demographics. Looking first to demographics, the court found

that District Twelve, which is composed of parts of six split

counties, received “almost 75 percent” of its population from

“three county parts which are a majority African-American in

population,” while “the other three county parts . . . have narrow

corridors which pick up as many African-Americans as are

needed for the district to reach its ideal size.” Cromartie v.

Hunt, No. 4:96-CV-104-BO (3) (E.D.N.C. April 14, 1998),

Appendix to Jurisdictional Statement (“Appendix”) at 6a-7a.

The court further found that “the four largest cities assigned to

District 12 are split along racial lines.” Id. at 7a. Moving onto

compactness, the district court found that “District 12 has an

irregular shape,” id. at 9a, that the district’s dispersion and

perimeter compactness measures “are much lower than the mean

18

compactness indicators for North Carolina[],” id. at 11a, and

that “it 1s still the most geographically, (sic) scattered of North

Carolina’s congressional districts,” id. at 20a. Also, the count

found that the district was “barely contiguous in parts.” Id. at

9a. Thus the court concluded, on the basis of what it termed

the undisputed evidence, that District Twelve, like its

predecessor, was “unusually shaped . . . wind[ing] its way from

Charlotte to Greensboro along the Interstate-85 corridor,

making detours to pick up heavily African-American parts of

[other] cities.” Id. at 19a.

This evidence was plainly insufficient to raise an inference

that race was the General Assembly’s predominant motivating

factor. First of all, District Twelve is a majority-white district:

just 46.67% of its total population and 43.36% of its voting

age population is black. Surely, if North Carolina was hell-

bent on subordinating all other factors to race, it would not

have drawn district lines that so reduced the probability of

electing a black representative. But even if the Court does not

believe that District Twelve’s majority-white population is

dispositive of the issue of the General Assembly’s predominant

purpose,

the fact that all of North Carolina’s congressional

districts [have a] majority-white [voting-age

population] at the very least makes the plaintiffs’

burden, which is already quite high, even more

onerous.

Id. at 31a (Ervin, J., dissenting); see Lawyer, 117 S. Ct. at 2195.

Second, District Twelve is “not so bizarre or unusual in

shape” as to raise an inference of racial gerrymandering.

Cromartie, Appendix at 25a (Ervin, J., dissenting). District

19

Twelve 1s among the most functionally compact in North

Carolina. It has the third shortest travel time and distance

between its farthest points of any district in North Carolina.

See Affidavit of Dr. Alfred W. Stuart, Appendix at 105a. Also,

Interstate-85 forms a major artery of access and communication

through the district. And although District Twelve does not

score well on tests of dispersion and perimeter compactness, it

is fully contiguous and is significantly more compact based on

these measures than its predecessor. See “An Evaluation of

North Carolina’s 1998 Congressional District” by Professor

Gerald R. Webster (“Webster Report”), Appendix at 127a, 133a.

Thus, Plaintiffs’ circumstantial evidence of racial

demographics and geographical compactness was insufficient

to justify an inference that North Carolina had used race as the

predominant factor in drawing district lines. Moreover, as is

shown below, any inference of impermissible racial

gerrymandering raised by this record was fully rebutted by

Defendants’ evidence.

2. Defendants Fully Rebutted Any Inference That Race

Was the Predominant Factor in the Districting

Process.

Even assuming, arguendo, that Plaintiffs’ circumstantial

evidence was sufficient to raise an inference of

unconstitutionality, Defendants fully rebutted that inference

with unchallenged proof that race was not the predominant

consideration in the drawing of District Twelve’s boundaries.

Inexplicably, the bulk of this evidence was completely ignored

by the district court. The Chairmen of both the State House of

Representatives’ Redistricting Committee and the State

Senate’s Redistricting Committee submitted affidavits

affirming that ensuring a particular racial balance was not the

General Assembly’s primary motivation in drawing District

20

Twelve. See Affidavit of Senator Roy A. Cooper, III (“Cooper

Affidavit”), Appendix at 70a-78a; Affidavit of Representative

W. Edwin McMahan (“McMahan Affidavit”), Appendix at 79a-

84a. Similarly, North Carolina’s submission to the Department

of Justice pursuant to section 5 of the Voting Rights Act

indicated that the “General Assembly’s primary goal in

redrawing the plan was to remedy the constitutional defects of

the former plan,” that is, to ensure that race was not the

predominant factor. See Affidavit of Gary O. Bartlett,

1 97C-27N of the Section 5 Submission Commentary (“Bartlett

Affidavit”), Appendix at 63a. According to its submission, the

General Assembly declined to create a majority-minority

Twelfth District because to do so “would artificially group

together citizens with disparate and diverging economic, social

and cultural interests and needs” and would thereby make “race

... the predominant factor.” Id. at 66a. Plaintiffs offered no

contrary direct evidence of Defendants’ motivations.

In addition, the Defendants offered extensive evidence that

the North Carolina General Assembly created District Twelve

in order to provide representation to communities of actual

shared interests. See Bartlett Affidavit, Appendix at 64a;

Webster Report, Appendix at 1 (noting “desire to include a

requisite number of people with similar social, economic or

political orientations” in a single district). States may

legitimately consider communities of interests when drawing

congressional districts, see Shaw II, 517 U.S. at 907; Miller,

515 U.S. at 919, and North Carolina’s reliance on these criteria

easily explain District Twelve’s shape and demographics.

10. A district providing representation for actual communities of

interest will not necessarily be physically compact. See supra Point

I.C.1.a. In addition, a district’s discernible racial character will often be

caused by the demonstrated correlations between race and actual

communities of interest. See Vera, 517 U.S. at 964 (plurality opinion)

(Cont’d)

21

North Carolina explicitly identified three communities of

interest that readily explain the shape and racial composition

of District Twelve. First, in order to maintain the House

delegation’s six-six partisan balance, the General Assembly

included precincts in District Twelve that had supported

democratic candidates in recent elections. See Bartlett Affidavit,

Appendix at 64a. Maintaining such a balance was necessary to

ensure compromise between the Republican-controlled State

House of Representatives and the Democrat-controlled State

Senate, and this in turn required placing District Twelve’s

Democratic incumbent (as well as the other eleven incumbents)

in “safe” districts. See Cooper Affidavit, Appendix at 71a-75a,

77a; McMahan Affidavit, Appendix at 81a-83a; Affidavit of

David Peterson, Ph.D., Appendix, at 85a-100a. District

Twelve’s large black population is thus the result of the voting

patterns of black North Carolinians, who overwhelming support

Democratic candidates. See Michael Barone & Grant Ujifusa,

The Almanac of American Politics 1998, 1052 (1998).

Though the district court at least acknowledged this

evidence, it failed to credit it, relying instead on anecdotal

evidence that “the legislators excluded many heavily-

Democratic precincts from District 12, even though those

precincts immediately border the District.” Cromartie,

(Cont’d)

(“[R]ace [often] correlates strongly with manifestations of community

of interest ....”); Abrams, 117 S. Ct. at 1947 (Breyer, J., dissenting)

(noting that rural and urban minorities living near one another may share

common interests). In this regard, it is imperative that courts recognize

that when a group of minority citizens organizes itself and lobbies a

state legislature for representation in Congress, the legislature’s assent

to that lobbying is properly ascribed to political, rather than racial,

motivations. It would be a travesty of the Equal Protection Clause (and

the First Amendment) for this Court to prevent racial minorities from

organizing and advocating for themselves in the political arena when

every other self-defined interest group is permitted to do so.

22

Appendix at 20a. From this, the court inferred that politics was

simply a pretext for race. However, as Judge Ervin noted in

dissent:

This evidence does not take into account .. . that

voters often do not vote in accordance with their

registered party affiliation. The State has argued,

and I see no reason to discredit their uncontroverted

assertions, that the district lines were drawn based

on votes for Democratic candidates in actual

elections, rather than the number of registered

voters.

Id. at 33a (Ervin, J., dissenting); Cooper Affidavit, Appendix

at 73a (“election results [from 1990-1996] were the principal

factor”). The decision to rely on voting rather than registration

was perfectly legitimate, see Vera, 517 U.S. at 968 (plurality

opinion), particularly given the documented history of white

registered North Carolina Democrats voting Republican to

avoid electing black candidates. See Gingles v. Edmisten, 590

F. Supp. 345, 367-72 (E.D.N.C. 1984), aff'd in part and rev'd

in part sub nom., Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986).

By rejecting Defendants’ evidence, the district court therefore

improperly substituted its judgment for that of the legislature

as to the appropriate criterion of partisanship.

Second, the district court completely ignored Defendants’

evidence that the General Assembly sought to provide

representation to inner-city residents. District Twelve is “a

functionally compact, highly urban district drawing together

citizens in Charlotte and the cities of the Piedmont Urban

Triad.” Cooper Affidavit, Appendix at 74a; see Cromartie,

Appendix at 36a-37a (Ervin, J., dissenting) (“I do not see how

anyone can argue that the citizens of, for example, the inner-

city of Charlotte do not have more in common with citizens of

23

the inner-cities of Statesville and Winston-Salem than with their

fellow Mecklenburg county citizens who happen to reside in

the suburban or rural areas.”). A State may reasonably seek to

provide effective representation to inner-city urban

communities. See Lawyer, 117 S. Ct. at 2195; Vera, 517 U.S.

at 966 (plurality opinion).

Third, the district court failed to consider evidence that

North Carolina sought to join in one district the very real

community of interests formed by localities abutting Interstate

85, a major line of communication, transportation, and

commerce for the culturally distinct Charlotte/Piedmont triad

region. In North Carolina, as in other states, residence in

proximity to a major transportation artery links people into

natural voting constituencies. See Cromartie, Appendix at 36a

(Ervin, J., dissenting) (“District 12 also was designed to join a

clearly defined ‘community of interest’ that has sprung up

among the inner-cities and along the more urban areas abutting

the interstate highways that are the backbone of the district.”);

Webster Report, Appendix at 124a (recognizing appropriateness

of “focus[ing] . . . upon major transportation corridors such as

freeways”); Vera, 517 U.S. at 966 (plurality opinion) (noting

that “transportation lines . . . implicate traditional districting’

principles”). Furthermore, by focusing the district on Interstate

835, the General Assembly fostered ease of access to legislators.

See Affidavit of Dr. Alfred W. Stuart, Appendix at 105a;

Webster Report, Appendix at 125a.

Indeed, this Court in Abrams, 117 S. Ct. at 1941, aff’g,

Johnson v. Miller, 922 F. Supp. 1556 (S.D. Ga. 1995), approved

the court-drawn Eleventh Congressional District in Georgia,

which the lower court had described as “a relatively compact

grouping of counties which follow a suburban to rural

progression and have Interstate Eighty-Five as a very real

connecting cable.” Johnson, 922 F. Supp. at 1564. Thus, this

24

Court has previously recognized the legitimate role that

Interstate 85 can play in creating communities of interest worthy

of representation. If Interstate 85 forms a legitimate locus for

the 11.79% black Eleventh District in Georgia, then North

Carolina may legitimately determine that the same highway

plays a similar role in North Carolina’s Twelfth District.

Defendants’ non-racial explanations therefore fully rebutted

whatever inference of discrimination may have been raised by

Plaintiffs’ weak circumstantial evidence of District Twelve’s

shape and racial demographics.

B. The District Court Relieved Plaintiffs of Their Difficult

Burden of Proof By Relying on Impact, Rather Than

Intent, to Find a Constitutional Violation.

Given the weakness of Plaintiffs’ circumstantial showing

and the overwhelming strength of Defendants’ rebuttal, the

district court erred in failing to grant summary judgment to

Defendants and in granting summary judgment to Plaintiffs.

The district court effectively erected a conclusive presumption

of purposeful discrimination on the basis of flimsy, completely

rebutted circumstantial evidence. For all practical purposes,

the district court shifted the burden of proof from Plaintiffs to

Defendants and improperly created an impact test for Shaw

cases brought by white voters. But see, e.g., Gomillion, 364

U.S. at 341 (representing the rare case where the effects of

governmental action were so overwhelming that the racial

purpose of the action was clear).

Once the proper burden of proof rules are applied, however,

it 1s clear that the district court erred in failing to grant

Defendants’ motion for summary judgment. Defendants are

entitled to summary judgment as a matter of law where, as here,

plaintiffs make an insufficient showing on an essential element

of their case as to which they bear the burden of proof. See

—

o

k

A

N

N

25

Celotex Corp. v. Catrett, 477 U.S. 317, 322-23 (19

opposing a summary judgment motion, plaintiffs may notes

on the pleadings, but must indicate, by affidavits or otherwise,

“specific facts showing that there is a genuine issue for trial.”

Fed. R. Civ. P. 56(¢); see Celotex, 477 U.S. at 324; Anderson

v. Liberty Lobby, Inc., 477 U.S. 242, 250 (1986). Moreover,

plaintiffs may not simply assert the existence of a factual

dispute. “If the evidence is merely colorable, or is not

significantly probative,” summary judgment is appropriate.

Anderson, 477 U.S. at 249-50 (internal citations omitted).

Furthermore, in considering the sufficiency of plaintiffs’

showing, the court “must view the evidence presented through

the prism of the substantive evidentiary burden.” Id. at 254. To

successfully oppose a summary judgment motion, plaintiffs who

bear a heightened burden of proof at trial must present sufficient

evidence to allow a trier of fact to find in their favor under the

heightened standard. See id. at 252-53; Miller, 515 U.S. at 916

(noting that in Shaw I actions, courts are directed to consider

heightened burden “when assessing ... the adequacy of a

plaintiff’s showing at the various stages of litigation and

determining whether to permit discovery or trial to proceed”)

(citing Celotex, 477 U.S. at 327).

Applying these standards, Defendants were plainly entitled

to a grant of summary judgment. See Cromartie, Appendix at

43a (Ervin, J., dissenting). Plaintiffs failed to offer specific and

significantly probative evidence sufficient to create a genuine

issue of fact as to whether racial considerations dominated the

General Assembly’s districting decisions to the exclusion of

other factors. See Crawford-el v. Britton, 118 S. Ct. 1584, 1598

(1998) (“[P]laintiff may not respond [to defendant’s summary

judgment motion] simply with general attacks upon the

defendant’s credibility, but rather must identify affirmative

evidence from which a jury could find that the plaintiff has

26

carried his or her burden of proving the pertinent motive.”);

10B Wright, Miller & Kane, Federal Practice & Procedure:

Civil 3d § 2730, at 40-42 (1998) (same). Unlike in every

previous case striking down a challenged district under Shaw

I, Plaintiffs offered, and could offer, no direct evidence that

race dominated any legislator’s considerations, much less the

considerations of the General Assembly as a whole. In contrast,

Defendants offered extensive direct evidence that traditional

districting criteria were not subordinated to race. In the face of

Defendants’ unrebutted evidence, Plaintiffs’ circumstantial

evidence simply could not create a genuine issue of fact as to

legislative purpose and therefore could not defeat Defendants’

motion for summary judgment. See Miller, 515 U.S. at 914

(evidence of discriminatory impact usually insufficient to

demonstrate discriminatory purpose, requiring courts to look

to other evidence); 10A Wright, Miller, & Kane, supra, § 2727,

at 470-71, 486-88, 501.

Incredibly, the district court not only failed to award

summary judgment to Defendants, it granted Plaintiffs’

summary judgment motion. This was manifest error for two

reasons. First, the district court applied an improper standard

for considering evidence on a motion for summary judgment.

“The evidence of the non-movant is to be believed, and all

justifiable inferences are to be drawn in his favor.” Anderson,

477 U.S. at 255; accord Eastman Kodak Co. v. Image Tech.

Servs., Inc., 504 U.S. 451, 456 (1992). Although Defendants

offered extensive evidence conclusively demonstrating that race

was not the predominant consideration, the district court ignored

most of that evidence. And what evidence the district court did

consider, it mischaracterized. See supra Point I1.A.2.

Second, the district court improperly granted summary

judgment to the Plaintiffs on the question of North Carolina’s

motivations in drawing its congressional districts. In light of

rt

Ad

-

oe

VE

RE

¢

27

the sworn statements of the Chairmen of the House and Senate

Redistricting Committees that race was simply one of many

factors guiding the drawing of District Twelve, and given that

Plaintiffs offered no direct evidence to the contrary, the court

could not legitimately have determined, as a matter of law, that

Plaintiffs had conclusively demonstrated that the General

Assembly acted with an impermissible purpose. See White

Motor Co. v. United States, 372 U.S. 253, 259 (1963) (court

should be wary of granting summary judgment where

dispositive issue requires assessment of state of mind); Johnson

v. Meltzer, 134 F.3d 1393, 1397-98 (9th Cir. 1998) (same). At

a minimum, this Court should remand the case for fact-finding

as to whether race was, indeed, the legislature’s predominant

concern. See Crawford-el, 118 S. Ct. at 1597 (credibility

assessments are not amenable to resolution on summary

judgment); Agosto v. INS, 436 U.S. 748, 756 (1978) (“[A]

district court generally cannot grant summary judgment based

on its assessment of the credibility of the evidence presented.”).

By awarding summary judgment to Plaintiffs on the basis

of the district’s shape and racial demographics despite extensive

evidence that its shape and demographics could be explained

through North Carolina’s application of traditional, race-neutral

districting factors, the district court effectively held that

Shaw I plaintiffs could raise a conclusive presumption of

predominant racial purpose solely on the basis of circumstantial

evidence. In effect, the district court’s decision, if permitted to

stand, would premise government liability on the basis of

perceived “discriminatory impact,” at least for white plaintiffs

challenging “too black” districts. The court’s ruling was

contrary to long-established principles of constitutional law and

must be reversed.