Correspondence from Bradford Reynolds to Leonard

Public Court Documents

October 2, 1984

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Hardbacks, Briefs, and Trial Transcript. Correspondence from Bradford Reynolds to Leonard, 1984. 2083e5c6-d592-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/29f9098f-5915-4b7d-a678-63f1ca775a38/correspondence-from-bradford-reynolds-to-leonard. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

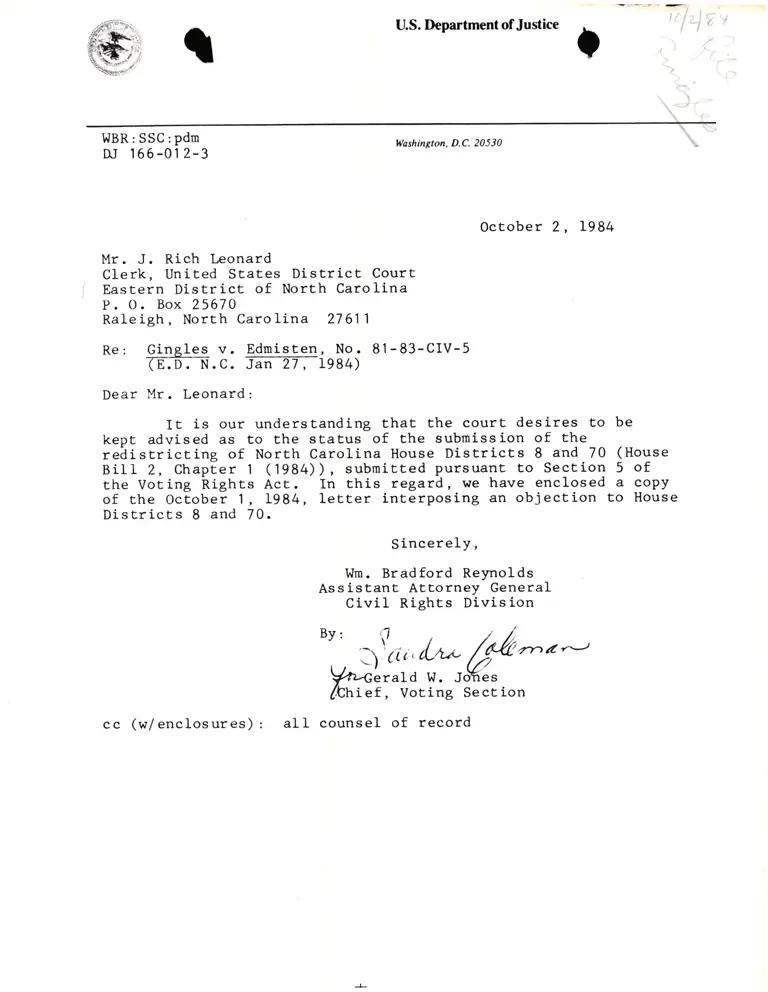

U.S. Department of Justice

WBR: SSC : pdm

ut 166-012-3

htashington, D.C. 20 5 30

Se ct ion

:Wr'r,z,-)

October 2, 1984

I4r. J. Rich Leonard

CIerk, UDited States District Court

Eastern District of North Carolina

P. O. Box 25670

Raleigh, North Carolina 27 61 1

Re: Gingles v. Eduisten, No.81-83-CIV-5

Fn.u; N.c. Jan 27, f984)

Dear Mr. Leonard:

It is our understanding that the court desires to be

kept advised as to the status of the submission of the

redistricting of North Carolina House Districts 8 and 70 (House

BiIl 2, ChapLer 1 (1984)), submitted pursuant to Section 5 of

the Voting nigtrts Act. In this regard, we have enclosed a coPy

of the Oclober 1, 1984, letter interposing an objection to House

Districts 8 and 70.

SincerelY,

Wm. Bradford Reynolds

Assistant Attorney General

Civil Rights Division

Byt .J

' cii,r)

Var*;r"ld w.

khi"t, voting

cc (w/enclosures) : alI counsel of record