Nixon v. Condon Court Opinion

Public Court Documents

May 2, 1932

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Nixon v. Condon Court Opinion, 1932. 08d6b2a1-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2a055b28-fe5d-478b-b853-90e16c1b45a2/nixon-v-condon-court-opinion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

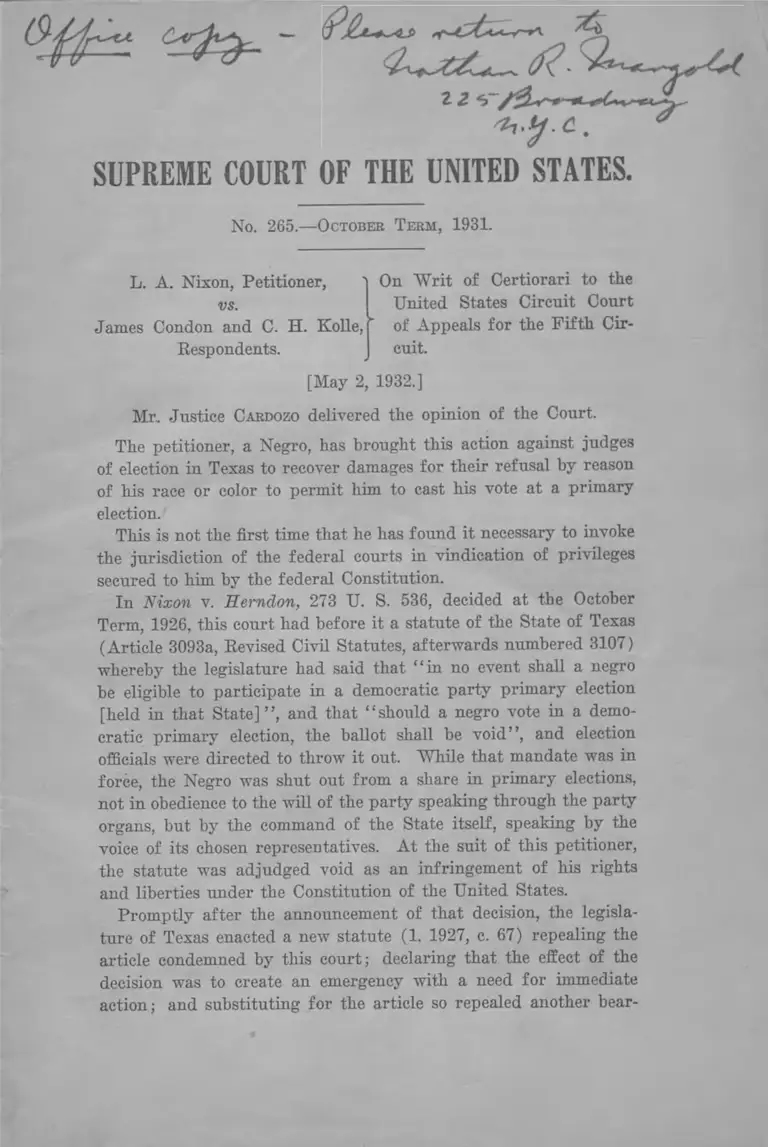

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES.

No. 265.— October Term, 1931.

L. A. Nixon, Petitioner,

vs.

James Condon and C. H. Kolle, "

Respondents.

On "Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Circuit Court

of Appeals for the Fifth Cir

cuit.

[May 2, 1932.]

Mr, Justice Cardozo delivered the opinion of the Court.

The petitioner, a Negro, has brought this action against judges

of election in Texas to recover damages for their refusal by reason

of his race or color to permit him to cast his vote at a primary

election.

This is not the first time that he has found it necessary to invoke

the jurisdiction of the federal courts in vindication of privileges

secured to him by the federal Constitution.

In Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536, decided at the October

Term, 1926, this court had before it a statute of the State of Texas

(Article 3093a, Revised Civil Statutes, afterwards numbered 3107)

whereby the legislature had said that “ in no event shall a negro

be eligible to participate in a democratic party primary election

[held in that State]” , and that “ should a negro vote in a demo

cratic primary election, the ballot shall be void” , and election

officials were directed to throw it out. While that mandate was in

force, the Negro was shut out from a share in primary elections,

not in obedience to the will of the party speaking through the party

organs, but by the command of the State itself, speaking by the

voice of its chosen representatives. At the suit of this petitioner,

the statute was adjudged void as an infringement of his rights

and liberties under the Constitution of the United States.

Promptly after the announcement of that decision, the legisla

ture of Texas enacted a new statute (1. 1927, c. 67) repealing the

article condemned by this court; declaring that the effect of the

decision was to create an emergency with a need for immediate

action; and substituting for the article so repealed another bear

2 Nixon ys. Condon et al.

ing the same number. By the article thus substituted, “ every

political party in this State through its State Executive Com

mittee shall have the power to prescribe the qualifications of its

own members and shall in its own way determine who shall he

qualified to vote or otherwise participate in such political party;

provided that no person shall ever he denied the right to parti

cipate in a primary in this State because of former political views

or affiliations or because of membership or non-membership in or

ganizations other than the political party.”

Acting under the new statute, the State Executive Committee

of the Democratic party adopted a resolution “ that all white

democrats who are qualified under the constitution and laws of

Texas and who subscribe to the statutory pledge provided in Ar

ticle 3110, Revised Civil Statutes of Texas, and none other, be

allowed to participate in the primary elections to be held July 28,

1928, and August 25, 1928” , and the chairman and secretary were

directed to forward copies of the resolution to the committees in

the several counties.

On July 28, 1928, the petitioner, a citizen of the United States,

and qualified to vote unless disqualified by the foregoing resolu

tion, presented himself at the polls and requested that he be

furnished with a ballot. The respondents, the judges of election,

declined to furnish the ballot or to permit the vote on the ground

that the petitioner was a Negro and that by force of the resolu

tion of the Executive Committee only white Democrats were al

lowed to be voters at the Democratic primary. The refusal was

followed by this action for damages. In the District Court there

was a judgment of dismissal (34 P. (2d) 464), which was af

firmed by the Circuit Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, 49

P. (2d) 1012. A writ of certiorari brings the cause here.

Barred from voting at a primary the petitioner has been, and

this for the soIq reason that his color is not white. The result

for him is no different from what it was when his cause was here

before. The argument for the respondents is, however, that iden

tity of result has been attained through essential diversity of

method. We are reminded that the Fourteenth Amendment is a

restraint upon the States and not upon private persons uncon

nected with a State. United States v. CruikshanTc, 92 U. S. 542;

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303; Ex parte Virginia,

Nixon vs. Condon et al. 3

100 U. S. 339, 346; James v. Bowman, 190 U. S. 127, 136. This

line of demarcation drawn, we are told that a political party is

merely a voluntary association; that it has inherent power like

voluntary associations generally to determine its own membership;

that the new article of the statute, adopted in place of the man

datory article of exclusion condemned by this court, has no other

effect than to restore to the members of the party the power

that would have been theirs if the lawmakers had been silent; and

that qualifications thus established are as far aloof from the im

pact of constitutional restraint as those for membership in a golf

club or for admission to a Masonic lodge.

Whether a political party in Texas has inherent power today

without restraint by any law to determine its own membership,

we are not required at this time either to affirm or to deny. The

argument for the petitioner is that quite apart from the article

in controversy, there are other provisions of the Election Law

whereby the privilege of unfettered choice has been withdrawn or

abridged (citing, e. g., Articles 2955, 2975, 3100, 3104, 3105, 3110,

3121, Revised Civil Laws); that nomination at a primary is in

many circumstances required by the statute if nomination is to be

made at all (Article 3101); that parties and their representatives

have become the custodians of official power (Article 3105); and

that if heed is to be given to the realities of political life, they are

now agencies of the State, the instruments by which government

becomes a living thing. In that view, so runs the argument, a

party is still free to define for itself the political tenets of its

members, but to those who profess its tenets there may be no

denial of its privileges.

A narrower base will serve for our judgment in the cause at

hand. Whether the effect of Texas legislation has been to work so

complete a transformation of the concept of a political party as a

voluntary association, we do not now decide. Nothing in this

opinion is to be taken as carrying with it an intimation that the

court is ready or unready to follow the petitioner so far. As to

that, decision must be postponed until decision becomes necessary.

Whatever our conclusion might be if the statute had remitted to

the party the untrammeled power to prescribe the qualifications of

its members, nothing of the kind was done. Instead, the statute

lodged the power in a committee, which excluded the petitioner

4 Nixon vs. Condon et al.

and others of his race, not by virtue of any authority delegated

by the party, hut by virtue of an authority originating or sup

posed to originate in the mandate of the law.

We recall at this point the wording of the statute invoked by

the respondents. “ Every political party in this State through

its State Executive Committee shall have the power to prescribe

the qualifications of its own members and shall in its own way

determine who shall be qualified to vote or otherwise participate

in such political party.” Whatever inherent power a State polit

ical party has to determine the content of its membership resides

in the State convention. Bryce, Modern Democracies, Vol. 2, p. 40.

There platforms of principles are announced and the tests of party

allegiance made known to the world. What is true in that regard

of parties generally, is true more particularly in Texas, where the

statute is explicit in committing to the State convention the for

mulation of the party faith (Article 3139). The State Executive

Committee, if it is the sovereign organ of the party, is not such

by virtue of any powers inherent in its being. It is, as its name

imports, a committee and nothing more, a committee to be chosen

by the convention and to consist of a chairman and thirty-one

members, one from each senatorial district of the State (Article

3139). To this committee the statute here in controversy has at

tempted to confide authority to determine of its own motion the

requisites of party membership and in so doing to speak for the

party as a whole. Never has the State convention made declara

tion of a will to bar Negroes of the State from admission to the

party ranks. Counsel for the respondents so conceded upon the

hearing in this court. Whatever power of exclusion has been

exercised by the members of the committee has come to them,

therefore, not as the delegates of the party, but as the delegates

of the State. Indeed, adherence to the statute leads to the con

clusion that a resolution once adopted by the committee must con

tinue to be binding upon the judges of election though the party

in convention may have sought to override it, unless the com

mittee, yielding to the moral force of numbers, shall revoke its

earlier action and obey the party will. Power so intrenched is

statutory, not inherent. If the State had not conferred it, there

would be hardly color of right to give a basis for its exercise.

Our conclusion in that regard is not affected by what was ruled

by the Supreme Court of Texas in Love v. Wilcox, 28 S. W. (2d)

Nixon vs. Condon et al. 5

515, or by the Court of Civil Appeals in White v. Lubbock, 30 S. W.

(2d) 722. The ruling in the first case was directed to the validity

of the provision whereby neither the party nor the committee is to

be permitted to make former political affiliations the test of party

regularity. There were general observations in the opinion as to

the functions of parties and committees. They do not constitute

the decision. The decision was merely this, that “ the committee

whether viewed as an agency of the State or as a mere agency of

the party is not authorized to take any action which is forbidden

by an express and valid statute.” The ruling in the second case,

which does not come from the highest court of the State, upholds

the constitutionality of section 3107 as amended in 1927, and

speaks of the exercise of the inherent powers of the party by the

act of its proper officers. There is nothing to show, however, that

the mind of the court was directed to the point that the members

of a committee would not have been the proper officers to exercise

the inherent powers of the party if the statute had not attempted to

clothe them with that quality. The management of the affairs of

a group already associated together as members of a party is ob

viously a very different function from that of determining who

the members of the group shall be. If another view were to be

accepted, a committee might rule out of the party a faction dis

tasteful to itself, and exclude the very men who had helped to

bring it into existence. In any event, the Supreme Court of Texas

has not yet spoken on the subject with clearness or finality, and

nothing in its pronouncements brings us to the belief that in the

absence of a statute or other express grant it would recognize a

mere committee as invested with all the powers of the party as

sembled in convention. Indeed its latest decision dealing with any

aspect of the statute here in controversy, a decision handed down

on April 21, 1932 (Love v. Buckner, Supreme Court of Texas), de

scribes the statute as constituting “ a grant of power” to the State

Executive Committee to determine who shall participate in the

primary elections.* What was questioned in that case was the

validity of a pledge exacted from the voters that it was their bona

*“ We are bound to give effect to a grant of power to the State Executive

Committee of a party to determine who shall participate in the acts o f the

party otherwise than by voting in a primary, when the Legislature grants

the power in language too plain to admit of controversy, and when the deter-

6 Nixon vs. Condon et al.

fide purpose to support the party nominees. The court in up

holding the exaction found a basis for its ruling in another article

of the Civil Statutes (Art. 3167), in an article of the Penal Code

(Art. 340), and in the inherent power of the committee to adopt

regulations reasonably designed to give effect to the obligation

assumed by an elector in the very act of voting. To clinch the

argument the court then added that if all these sources of author

ity were inadequate, the legislature had made in Article 3107 an

express “ grant of power” to determine qualifications generally.

There is no suggestion in the opinion that the inherent power of

the committee was broad enough (apart from legislation) to per

mit it to prescribe the extent of party membership, to say to a

group of voters, ready as was the petitioner to take the statutory

pledge, that one class should be eligible and another not. On the

contrary, the whole opinion is instinct with the concession that

pretensions so extraordinary must find their warrant in a statute.

The most that can be said for the respondents is that the inherent

powers of the Committee are still unsettled in the local courts.

Nothing in the state of the decisions requires us to hold that they

have been settled in a manner that would be subversive of the

fundamental postulates of party organization. The suggestion is

offered that in default of inherent power or of statutory grant the

committee may have been armed with the requisite authority by

vote of the convention. Neither at our bar nor on the trial was

the case presented on that theory. At every stage of the case the

assumption has been made that authority, if there was any, was

either the product of the statute or was inherent in the committee

under the law of its creation.

We discover no significance, and surely no significance favor

able to the respondents, in earlier acts of legislation whereby the

power to prescribe additional qualifications was conferred on local

committees in the several counties of the State. L. 1903, c. 103,

sec. 94. The very fact that such legislation was thought necessary

is a token that the committees were without inherent power. We

do not impugn the competence of the legislature to designate the

mination o f the Committee conflicts wi+h no other statutory requirement or

prohibition, especially when the Committee’s determination makes effectual

the public policy o f the State as revealed in its statutes. ’ ’ Love v. Buckner,

supra.

Nixon vs. Condon et al. I

agencies whereby the party faith shall be declared and the party

discipline enforced. The pith of the matter is simply this, that

when those agencies are invested with an authority independent

of the will of the association in whose name they undertake to

speak, they become to that extent the organs of the State itself,

the repositories of official power. They are then the governmental

instruments whereby parties are organized and regulated to the

end that government itself may be established or continued. What

they do in that relation, they must do in submission to the man

dates of equality and liberty that bind officials everywhere. They

are not acting in matters of merely private concern like the di

rectors or agents of business corporations. They are acting in

matters of high public interest, matters intimately connected with

the capacity of government to exercise its functions unbrokenly

and smoothly. Whether in given circumstances parties or their

committees are agencies of government within the Fourteenth or

the Fifteenth Amendment is a question which this court will de

termine for itself. It is not concluded upon such an inquiry by

decisions rendered elsewhere. The test is not whether the members

of the Executive Committee are the representatives of the State in

the strict sense in which an agent is the representative of his prin

cipal. The test is whether they are to be classified as representa

tives of the State to such an extent and in such a sense that the

great restraints of the Constitution set limits to their action.

With the problem thus laid bare and its essentials exposed to

view, the case is seen to be ruled by Nixon v. Herndon, supra.

Delegates of the State’s power have discharged their official func

tions in such a way as to discriminate invidiously between white

citizens and black. Ex parte Virginia, supra; Buchanan v. Warley,

245 IT. S. 60, 77. The Fourteenth Amendment, adopted as it was

with special solicitude for the equal protection of members of

the Negro race, lays a duty upon the court to level by its judg

ment these barriers of color.

The judgment below is reversed and the cause remanded for

further proceedings in conformity with this opinion.

A true copy.

Test:

Clerk, Supreme Court, TJ. S.

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

No. 265.— October Term, 1931.

L. A. Nixon, Petitioner, 1 On Writ of Certiorari to

the United States Cir-

vs' ' cuit Court of Appeals

Janies Condon and C. H. Kolle. for the Fifth Circuit.

[May 2, 1932.]

Separate opinion of Mr. Justice McReynolds.

March 15, 1929, petitioner here brought suit for damages in the

United States District Court, Western Division of Texas, against

Condon and Kolle, theretofore judges in a Democratic primary

election. He claims they wrongfully deprived him of rights guar

anteed hy the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, Federal

Constitution, by denying him the privilege of voting therein. Upon

motion the trial court dismissed the petition, holding that it failed

to state a cause of action; the Circuit Court of Appeals sustained

this ruling. The matter is here by certiorari.

The original petition, or declaration, alleges—

L. A. Nixon, a negro citizen of the United States and of Texas

duly registered and qualified to vote in Precinct No. 9, El Paso

County at the general election and a member of the Democratic

party, was entitled to participate in the primary election held

by that party July 28, 1928, for nominating candidates for State

and other offices. He duly presented himself and sought to cast

his ballot. Defendants, the judges, refused his request by reason

of the following resolution theretofore adopted by the State Demo

cratic Executive Committee—

‘ ‘ Resolved: That all white Democrats who are qualified

and under the Constitution and laws of Texas and who sub

scribe to the statutory pledge provided in Article 3110, Re

vised Civil Statutes of Texas, and none other, be allowed to

participate in the primary elections to be held July 28, 1928,

2 Nixon vs. Condon et al.

and August 25, 1928, and further, that the Chairman and

secretary of the State Democratic Executive Committee be

directed to forward to each Democratic County Chairman in

Texas a copy of this resolution for observance.”

That, the quoted resolution “ was adopted by the State Demo

cratic Executive Committee of Texas under authority of the Act

of the Legislature” — Chap. 67, approved June 7, 1927. Chapter

67 undertook to repeal former Article 3107,* * Chap. 13, Rev. Civil

Stat. 1925, which had been adopted in 1923, Ch. 32, Sec. 1 (Article

3093a) and in lieu thereof to enact the following:

“ Article 3107 (Ch. 67 Acts 1927). Every political party in

this State through its State Executive Committee shall have

the power to prescribe the qualifications of its own members

and shall in its own way determine who shall be qualified to

vote or otherwise participate in such political party; pro

vided that no person shall ever be denied the right to par

ticipate in a primary in this State because of former political

views or affiliations or because of membership or non-mem

bership in organizations other than the political party.”

That, in 1923, prior to enactment of Chap. 67, the Legislature

adopted Article 3093a,t Revised Civil Statutes, declaring that no

negro should be eligible to participate in a Democratic party pri

mary election. This was held invalid state action by Nixon v.

Herndon, 273 U. S. 536.

That, when Chap. 67 was adopted only the Democratic party

held primary elections in Texas and the legislative purpose was

tArticle 3093a from Acts 1923. “ All qualified voters under the laws and

constitution o f the State of Texas who are bona fide members of the Demo

cratic party, shall be eligible to participate in any Democratic party primary

election, provided such voter complies with all laws and rules governing

party primary elections; however, in no event shall a negro be eligible to

participate in a Democratic party primary election held in the State of Texas,

and should a negro vote in a Democratic primary election, such ballot shall

be void and election officials are herein directed to throw out such ballot and

not count the same.’ ’

*Original Art. 3107— Rev. Civ. Stats. 1925: “ In no event shall a negro be

eligible to participate in a Democratic party primary election held in the

State o f Texas, and should a negro vote in a Democratic primary election,

such ballot shall be void and election officials are herein directed to throw out

such ballot and not count the same. ’ ’

thereby to prevent Nixon and other negroes from participating in

such primaries.

That, Chap. 67 and the above quoted resolution of the Execu

tive Committee are inoperative, null and void in so far as they

exclude negroes from primaries. They conflict with the Four

teenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Federal Constitution

and laws of the United States.

That, there are many thousand negro Democratic voters in

Texas. The State is normally overwhelmingly Democratic and

nomination by the primaries of that party is equivalent to an

election. Practically there is no contest for State offices except

amongst candidates for such nominations.

That, the defendants’ action in denying petitioner the right

to vote was unlawful, deprived him of valuable political rights,

and damaged him five thousand dollars. And for this sum he

asks judgment.

The trial court declared—

“ The Court here holds that the State Democratic Executive

Committee of the State of Texas, at time of the passage of the

resolution here complained of, was not a body corporate to which

the Legislature of the State of Texas could delegate authority to

legislate, and that the members of said Committee were not of

ficials of the State of Texas, holding position as officers of the

State of Texas, under oath, or drawing compensation from the

State, and not acting as a State governmental agency, within the

meaning of the law, but only as private individuals holding such

position as members of said State Executive Committee by virtue

of action taken upon the part of members of their respective po

litical party; and this is also true as to defendants, they acting

only, as representatives of such political party, v iz: the Democratic

party, in connection with the holding of a Democratic primary

election for the nomination of candidates on the ticket of the Demo

cratic party to be voted on at the general election, and in refusing

to permit plaintiff to vote at such Democratic primary election

defendants were not acting for the State of Texas, or as a gov

ernmental agency of said State.”

Also, “ that the members of a voluntary association, such as a

political organization, members of the Democratic party in Texas,

possess inherent power to prescribe qualifications regulating mem

Nixon vs. Condon et al. 3

4 Nixon vs. Condon et al.

bership of such organizations, or political party. That this is, and

was, true without reference to the passage by the Legislature of

the State of Texas of said Art. 3107, and is not affected by the

passage of said act, and such inherent power remains and exists

just as if said act had never been passed.”

The Circuit Court of Appeals said—

“ The distinction between appellant’s cases, the one under the

1923 statute and the other under the 1927 statute, is that he was

denied permission to vote in the former by State statute, and in the

latter by resolution of the State Democratic Executive Committee.

It is argued on behalf of appellant that this is a distinction without

a difference, and that the State through its legislature attempted

by the 1927 act to do indirectly what the Supreme Court had held

it was powerless to accomplish directly by the 1923 act.

“ We are of opinion, however, that there is a vast difference be

tween the two statutes. The Fourteenth Amendment is expressly

directed against prohibitions and restraints imposed by the States,

and the Fifteenth protects the right to vote against denial or

abridgment by aUy State or by the United States; neither operates

against private individuals or voluntary associations. United

States v. Cruikshank, 92 U. S. 542; Virginia v. Bives, 100 U. S.

313; James v. Bowman, 190 U. S. 127.

“ A political party is a voluntary association, and as such has

the inherent power to prescribe the qualifications of its members.

The act of 1927 was not needed to confer such power; it merely

recognized a power that already existed. Waples v. Marrast, 108

Tex. 5; White v. Lubbock, 30 (Tex.) S. W. 722; Grigsby v. Harris,

27 F. (2d) 942. It did not attempt as did the 1923 act to exclude

any voter from membership in any political party. Precinct

judges of election are appointed by party executive committees

and are paid for their services out of funds that are raised by

assessments upon candidates. Revised Civil Statutes of Texas,

Secs. 3104, 3108.”

I think the judgment below is right and should be affirmed.

The argument for reversal is this—

The statute— Chap. 67, present Article 3107—declares that every

political party through its State Executive Committee “ shall have

the power to prescribe the qualifications of its own members and

Nixon vs. Condon et al. 5

shall in its own way determine who shall he qualified to vote or

otherwise participate in such political party.” The result, it is

said, is to constitute the Executive Committee an instrumentality of

the State with power to take action, legislative in nature, concern

ing membership in the party. Accordingly, the attempt of the

Democratic Committee to restrict voting in primaries to white

people amounted to State action to that effect within the intend

ment of the Federal Constitution and was void under Nixon v.

Herndon, supra.

This reasoning rests upon an erroneous view of the meaning

and effect of the statute.

In Nixon v. Herndon the Legislature in terms forbade all negroes

from participating in Democratic primaries. The exclusion was

the direct result of the statute and this was declared invalid be

cause in conflict with the Fourteenth Amendment.

The act now challenged withholds nothing from any negro; it

makes no discrimination. It recognizes power in every political

party, acting through its Executive Committee, to prescribe quali

fications for membership, provided only that none shall be ex

cluded on account of former political views or affiliations, or mem

bership or non-membership in any non-political organization. The

difference between the two pronouncements is not difficult to dis

cover.

Nixon’s present complaint rests upon the asserted invalidity of

the resolution of the Executive Committee and, in order to prevail,

he must demonstrate that it amounted to direct action by the State.

The plaintiff’s petition does not attempt to show what powers the

Democratic party had entrusted to its State Executive Committee.

It says nothing of the duties of the Committee as a party organ;

no allegation denies that under approved rules and resolutions,

it may determine and announce qualifications for party member

ship. We cannot lightly suppose that it undertook to act without

authority from the party. Ordinarily, between conventions party

executive committees have general authority to speak and act in

respect of party matters. There is no allegation that the ques

tioned resolution failed to express the party will. For present

purposes the Committee’s resolution must be accepted as the voice

of the party.

6 Nixon vs. Condon et al.

Petitioner insists that the Committee’s resolution was author

ized by the State; the statute only recognizes party action and he

may not now deny that the party had spoken. The exclusion re

sulted from party action and on that footing the cause must he

dealt with. Petitioner has planted himself there. Whether the

cause would be more substantial if differently stated, we need not

inquire.

As early as 1895-—Ch. 35, Acts 1895—the Texas Legislature

undertook through penal statutes to prevent illegal voting in

political primaries, also false returns, bribery, etc. And later,

many, if not all, of the general safeguards designed to secure

orderly conduct of regular elections were extended to party pri

maries.

By Acts of 1903 and 1905, and subsequent amendments, the

Legislature directed that only official ballots should he used in

all general elections. These are prepared, printed and distributed

by public officials at public expense.

With adoption of the official ballot it became necessary to pre

scribe the methods for designating the candidates whose names

might appear on such ballot. Three, or more, have been author

ized. A party whose last candidate for governor received 100,000

votes must select its candidate through a primary election. Where

a party candidate has received less than 100,000, and more than

10,000, votes it may designate candidates through convention or

primary, as its Executive Committee may determine. A written

petition by a specified number of voters may be used in behalf

of an independent or nonpartisan candidate.

Some of the States have undertaken to convert the direct primary

into a legally regulated election. In others, Texas included, the

primary is conducted largely under party rules. Expenses are

borne by the party; they are met chiefly from funds obtained by

assessments upon candidates. A number of States (eleven per

haps) leave the determination of one’s right to participate in a

primary to the party, with or without certain minimum require

ments stated by statute. In “ Texas the party is free to impose

and enforce the qualifications it sees fit,” subject to some definite

restrictions. See Primary Elections, Merriam and Overaeker, pp.

66, 72, 73.

Nixon vs. Condon et al. 7

A “ primary election” within the meaning of the chapter of

the Texas Rev. Civil Stat. relating to nominations “ means an

election held by the members of an organized political party for

the purpose of nominating the candidates of such party to be

voted for at a general or special election, or to nominate the county

executive officers of a party.” Article 3100; General Laws 1905,

(1st C. S.) Ch. 11, Sec. 102. The statutes of the State do not

and never have undertaken to define membership—who shall be

regarded as a member—in a political party. They have said that

membership shall not be denied to certain specified persons; other

wise, the matter has been left with the party organization.

Since 1903 (Acts 1903, Ch. Cl., Sec. 94,* p. 150, 28th Leg.;

Acts 1905, Ch. 11, Sec. 103, p. 543, 29th Leg.) the statutes of

Texas have recognized the power of party executive committees to

define the qualifications for membership. The Act of 1923, Ch.

32, Sec. 1, (Art. 3093a) and the Act of 1927, Ch. 67, Sec. 1, (Art.

3107) recognize the authority of the party through the Executive

Committee, or otherwise, to specify such qualifications throughout

the State. See Love v. Wilcox, 28 S. W. Rep. (2d) 515, 523.

These Acts, and amendments, also recognize the right of State

and County Executive Committees generally to speak and act for

the party concerning primaries. These committees appoint the

necessary officials, provide supplies, canvass the votes, collect as

sessments, certify the successful candidates, pay expenses and

do whatever is required for the orderly conduct of the primaries.

Their members are not State officials; they are chosen by those

who compose the party; they receive nothing from the State.

By the amendment of 1923 the Legislature undertook to declare

that “ all qualified voters under the laws and constitution of the

State of Texas who are bona fide members of the Democratic party,

shall he eligible to participate in any Democratic party primary

election, provided such voter complies with all laws and rules

governing party primary elections; however, in no event shall a

negro he eligible to participate in a Democratic party primary elec

tion held in the State of Texas.” Love v. Wilcox, supra, p. 523.

*Aets 1903, Ch. Cl. “ Sec. 94. . . . provided, that the county execu

tive committee of the party holding any primary election may prescribe ad

ditional qualifications necessary to participate therein.”

8 Nixon vs. Condon et al.

This enactment, held inoperative by Nixon v. Herndon, supra,

(1927) was promptly repealed.

The courts of Texas have spoken concerning the nature of po

litical primary elections and their relationship to the State. And

as our present concern is with parties and legislation of that State,

we turn to them for enlightenment rather than to general obser

vations by popular writers on public affairs.

In Waples v. Marrast, 108 Texas 5, 11, 12, decided in 1916, the

Supreme Court declared—

“ A political party is nothing more or less than a body of men

associated for the purpose of furnishing and maintaining the

prevalence of certain political principles or beliefs in the public

policies of the government. As rivals for popular favor they

strive at the general elections for the control of the agencies of

the government as the means of providing a course for the gov

ernment in accord with their political principles and the adminis

tration of those agencies by their own adherents. According to

the soundness of their principles and the wisdom of their policies

they serve a great purpose in the life of a government. But the

fact remains that the objects of political organizations are inti

mate to those who compose them. They do not concern the gen

eral public. They directly interest, both in their conduct and in

their success, only so much of the public as are comprised in their

membership, and then only as members of the particular organi

zation. They perform no governmental function. They consti

tute no governmental agency. The purpose of their primary elec

tions is merely to enable them to furnish their nominees as can

didates for the popular suffrage. In the interest of fair methods

and a fair expression by their members of their preference in the

selection of their nominees, the State may regulate such elections

by proper laws, as it has done in our general primary law, and as

it was competent for the Legislature to do by a proper act of the

character of the one here under review. But the payment of the

expenses of purely party elections is a different matter. On prin

ciple, such expenses can not be differentiated from any other

character of expense incurred in carrying out a party object, since

the attainment of a party purpose— the election of its nominees

at the general elections through the unified vote of the party mem

bership, is necessarily the prime object of a party primary.

Nixon vs. Condon et al. 9

“ To provide nominees of political parties for the people to vote

upon in the general elections, is not the business of the State. It

is not the business of the State because in the conduct of the gov

ernment the State knows no parties and can know none. If it is

not the business of the State to see that such nominations are

made, as it clearly is not, the public revenues can not be em

ployed in that connection. To furnish their nominees as claimants

for the popular favor in the general elections is a matter which

concerns alone those parties that desire to make such nominations.

It is alone their concern because they alone are interested in the

success of their nominees. The State, as a government, can not

afford to concern itself in the success of the nominees of any po

litical party, or in the elective offices of the people being filled only

by those who are the nominees of some political party. Political

parties are political instrumentalities. They are in no sense gov

ernmental instrumentalities. The responsible duties of the State

to all the people are to be performed and its high objects effected

without reference to parties, and they have no part or place in the

exercise by the State of its great province in governing the people. ’ ’

Koy v. Schneider, 110 Texas, 369, 376 (April 21, 1920)—“ The

Act of the Legislature deals only with suffrage within the party

primary or convention, which is but an instrumentality of a group

of individuals for the accomplishment of party ends.” And see

id. pp. 394 et seq.

Cunningham v. McDermett, 277 S. W. Rep. 218, (Court of Civil

Appeals, Oct. 22, 1925)—“ Appellant contends that the Legis

lature by prescribing how party primaries must be conducted,

turned the party into a governmental agency, and that a candi

date of a primary, being the candidate of the governmental agency,

should be protected from the machinations of evilly disposed

persons.

“ With this proposition we cannot agree, but consider them as

they were held to be by our Supreme Court in the case of Waples

v. Marrast, 108 Tex. 5, 184 S. W. 180, L. R. A. 1917A, 253, in which

Chief Justice Phillips said: ‘ Political parties are political instru

mentalities. They are in no sense governmental instrumen

talities.’ ”

Briscoe v. Boyle, 286 S. W. 275, 276 (Court Civil Appeals, July

2, 1926)— This case was decided by an inferior court while the

10 Nixon vs. Condon et al.

Act of 1923, Ch. 32, See. 1, amending Art. 3093, was thought to be

in force—before Nixon v. Herndon, supra, ruled otherwise. It

must be read with that fact in mind. Among other things, the

Court said—“ In fine, the Legislature has in minute detail laid

out the process by which political parties shall operate the statute-

made machinery for making party nominations, and has so hedged

this machinery with statutory regulations and restrictions as to

deprive the parties and their managers of all discretion in the

manipulation of that machinery.”

Love v. Wilcox, supra, 522 (Sup. Ct., May 17, 1930)—“ We are

not called upon to determine whether a political party has power,

beyond statutory control, to prescribe what persons shall partici

pate as voters or candidates in its conventions or primaries. We

have no such state of facts before us. The respondents claim that

the State Committee has this power by virtue of its general au

thority to manage the affairs of the party. The statute, article

3107, Complete Tex. St. 1928 (Vernon’s Ann. Civ. St. art. 3107),

recognizes this general authority of the State Committee, but places

a limitation on the discretionary power which may be conferred

on that committee by the party by declaring that, though the party

through its State Executive Committee, shall have the power to

prescribe the qualifications of its own members, and to determine

who shall be qualified to vote and otherwise participate, yet the

committee shall not exclude anyone from participation in the

party primaries because of former political views or affiliations, or

because of membership or non-membership in organizations other

than the political party. The committee’s discretionary power is

further restricted by the statute directing that a single, uniform

pledge be required of the primary participants. The effect of

the statutes is to decline to give recognition to the lodgment of

power in a State Executive Committee, to be exercised at its dis

cretion. The statutes have recognized the right of the party to

create an Executive Committee as an agency of the party, and

have recognized the right of the party to confer upon that com

mittee certain discretionary powers, but have declined to recog

nize the right to confer upon the committee the discretionary

power to exclude from participation in the party’s affairs any

one because of former political views or affiliations, or because of

refusal to take any other than the statutory pledge. It is obvious,

Nixon vs. Condon et al. 11

we think, that the party itself never intended to confer upon its

Executive Committee any such discretionary power. The party

when it selected its State Committee did so with full knowledge of

the statutory limitations on that committee’s authority, and must

be held to have selected the committee with the intent that it would

act within the powers conferred, and within the limitations de

clared by the statute. Hence, the committee, whether viewed as

an agency of the state or as a mere agency of the party, is not

authorized to take any action which is forbidden by an express

and valid statute.”

Thomas B. Love, Appellant v. Buchner and Wakefield, Appellees,

Texas Supreme Court, April 21, 1932.

The Court of Civil Appeals certified to the Supreme Court for

determination the question—“ Whether the Democratic State Ex

ecutive Committee had lawful authority to require otherwise law

fully qualified and eligible Democratic voters to take the pledge

specified in the resolution adopted by the Committee at its meet

ing in March,” 1932.

The resolution directed that no person should be permitted to

participate in any precinct or county Democratic convention held

for the purpose of selecting delegates to the State convention at

which delegates to the National Democratic Convention are selected

unless such person shall take a written pledge to support the

nominees for President and Vice-President.

“ The Court answers that the Executive Committee was author

ized to require the voters to take the specified pledge.”

It said—

“ The Committee’s power to require a pledge is contested on the

ground that the Committee possesses no authority over the conven

tions of its party not granted by statute, and that the statutes of

Texas do not grant, but negative, the Committee’s power to exact

such a pledge.

“ We do not think it consistent with the history and usages of

parties in this State nor with the course of our legislation to re

gard the respective parties or the state executive committees as

denied all power over the party membership, conventions, and pri

maries save where such power may be found to have been expressly

delegated by statute. On the contrary, the statutes recognize party

12 Nixon vs. Condon et ad.

organizations including the state committees, as the repositories of

party power, which the Legislature has sought to control or regu

late only so far as was deemed necessary for important govern

mental ends, such as purity of the ballot and integrity in the as

certainment and fulfillment of the party will as declared by its

membership.

“ Without either statutory sanction or prohibition, the party

must have the right to adopt reasonable regulations for the en

forcement of such obligations to the party from its members as

necessarily arise from the nature and purpose of party govern

ment. . . .

“ We are forced to conclude that it would not be beyond the

power of the party through a customary agency such as its state

executive committee to adopt regulations designed merely to en

force an obligation arising from the very act of a voter in par

ticipating in party control and party action, though the statutes

were silent on the subject. . . .

“ The decision in Love v. Wilcox, 119 Tex. 256, gave effect to

the legislative intent by vacating action of the State Committee

violative of express and valid statutes. Our answer to the cer

tified question likewise gives effect to the legislative intent in up

holding action of the State Committee in entire accord with the

governing statutes as well as with party custom.”

The reasoning advanced by the court to support its conclusion

indicates some inadvertence or possibly confusion. The difference

between statutes which recognize and those which confer power is

not always remarked, e. g., “ With regard to the state com

mittee’s power to exact this pledge the statutes are by no means

silent. The statutes do not deny the power but plainly recognize

and confer same.” But the decision itself is a clear affirmation

of the general powers of the State Executive Committee under

party custom to speak for the party and especially to prescribe

the prerequisites for membership and for “ voters of said political

party” in the absence of statutory inhibition. The point actually

ruled is inconsistent with the notion that the Executive Committee

does not speak for the organization; also inconsistent with the

view that the Committee’s powers derive from State statutes.

Nixon vs. Condon et al. 13

If statutory recognition of the authority of a political party

through its Executive Committee to determine who shall par

ticipate therein gives to the resolves of such party or committee

the character and effect of action by the State, of course the same

rule must apply when party conventions are so treated; and it

would he difficult logically to deny like effect to the rules and by

laws of social or business clubs, corporations, and religious asso

ciations, etc., organized under charters or general enactments.

The State acts through duly qualified officers and not through the

representatives of mere voluntary associations.

Such authority as the State of Texas has to legislate concern

ing party primaries is derived in part from her duty to secure

order, prevent fraud, etc., and in part from obligation to pre

scribe appropriate methods for selecting candidates whose names

shall appear upon the official ballots used at regular elections.

Political parties are fruits of voluntary action. Where there

is no unlawful purpose, citizens may create them at will and limit

their membership as seems wise. The State may not interfere.

White men may organize; blacks may do likewise. A woman’s

party may exclude males. This much is essential to free govern

ment.

I f any political party as such desires to avail itself of the privi

lege of designating candidates whose names shall be placed on

official ballots by the State it must yield to reasonable conditions

precedent laid down by the statutes. But its general powers are

not derived from the State and proper restrictions or recognition

of powers cannot become grants.

It must be inferred from the provisions in her statutes and

from the opinions of her courts that the State of Texas has in

tended to leave political parties free to determine who shall be

admitted to membership and privileges, provided that none shall

be excluded for reasons which are definitely stated and that the

prescribed rules in respect of primaries shall be observed in order

to secure official recognition of nominees therein for entry upon

the ballots intended for use at general elections.

By the enactment now questioned the Legislature refrained from

interference with the essential liberty of party associations and

recognized their general power to define membership therein.

The words of the statute disclose such purpose and the circum-

14 Nixon vs. Condon et al.

stances attending its passage add emphasis. The act of 1923 had

forbidden negroes to participate in Democratic primaries. Nixon

v. Herndon (March, 1927) supra, held the inhibition invalid.

Shortly thereafter (June, 1927) the Legislature repealed it and

adopted the Article now numbered 3107 (Rev. Stats. 1928) and

here under consideration. The fair conclusion is, that accepting

our ruling as conclusive the lawmakers intended expressly to re

scind action adjudged beyond their powers and then clearly to

announce recognition of the general right of political parties to

prescribe qualifications for membership. The contrary view dis

regards the words, that “ every political party . . . shall in

its own way determine who shall be qualified to vote or otherwise

participate in such political party” ; and really imputes to the

Legislature an attempt indirectly to circumvent the judgment of

this Court. We should repel this gratuitous imputation; it is

vindicated by no significant fact.

The notion that the statute converts the Executive Committee

into an agency of the State also lacks support. The language

employed clearly imports that the political party, not the State,

may act through the Committee. As shown above since the Act

of 1903 the Texas laws have recognized the authority of Execu

tive Committees to announce the party will touching membership.

And if to the considerations already stated there be added the

rule announced over and over again that when possible statutes

must he so construed as to avoid unconstitutionality, there can re

main no substantial reason for upsetting the Legislature’s laudable

effort to retreat from an untenable position by repealing the earlier

act, and then declare the existence of party control over member

ship therein to the end that there might he orderly conduct of

party affairs including primary elections.

The resolution of the Executive Committee was the voice of the

party and took from appellant no right guaranteed by the Federal

Constitution or laws. It was incumbent upon the judges of the

primary to obey valid orders from the Executive Committee. They

inflicted no wrong upon Nixon.

A judgment of affirmance should he entered.

I am authorized to say that Mr. Justice V an Devanter, Mr.

Justice Sutherland and Mr. Justice Butler concur in this opinion.