North Carolina General Assembly State Representative Districts

Working File

January 1, 1977

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Williams. North Carolina General Assembly State Representative Districts, 1977. 001f96b2-da92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2aa51bf6-edf7-445f-add4-a23b74224133/north-carolina-general-assembly-state-representative-districts. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

@9

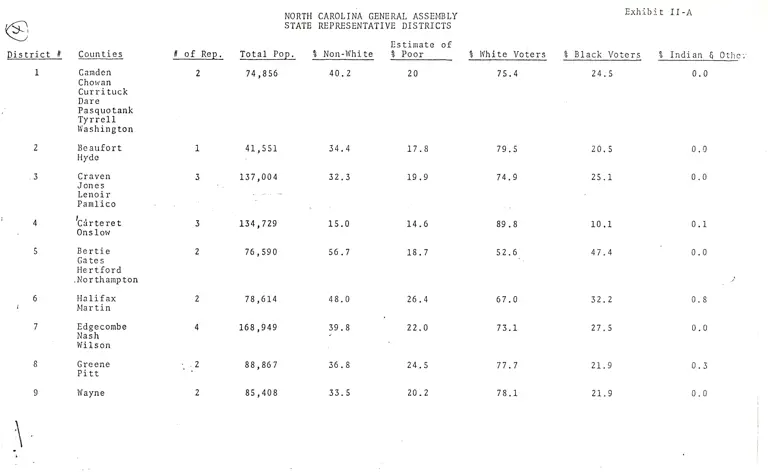

District #

1

Counties

# of Reg.

NORTH CAROLINA GENERAL ASSEMBLY

STATE REPRESENTATIVE DISTRICTS

Estimate of

0

Total Bop. % Non—White 6 Poor % White

Voters

% Black

Exhibit II-A

0

Voters 6 Indian 6 Other

Camden 2

Chowan

Currituck

Dare

Pasquotank

Tyrrell

Washington

Beaufort 1

Hyde

Craven 3

Jones

Lenoir

Pamlico

_%érteret 3

Onslow

Bertie 2

Gates

Hartford

.Northampton

Halifax 2

Martin

Edgecombe 4

Nash

Wilson

Greene -_.2

Pitt '

Wayne 2

74,856 40.2 20 75.

41,551 34.4 17.8 79.

137,004 32.3 19.9 74.

134,729 15.0 14.6 89.

76,590 56.7 18.7 52.

78,614 48.0 26.4 67.

168,949 39.8 ' 22.0 73.

88,867 36.8 24.5 77.

85,408 33.5 20.2 78.

4

24.

20.

25.

10.

47.

32.

27.

21.

21.

5 _0.0

4

1

Page 2 -- North Carolina General Assembly State Representative Districts

I Estimate of ‘

District # Counties # of Rep. Total Pop. % Non-White % Poor % White Voters Black Voters 8 Indian 6 Other

10 .Duplin 1 38,015 34.3 27.5 79.6 20.4 0.0

11 Brunswick 1 42,372 36.4 ‘ 23.5 74.6 25.4 0.0

Pender

12 New Hanover 2 82,996 22.9 14.1 84.1, 15.8 0.1

13 Caswell 3 126,232 44.2 20.5 65.8 33.8 0.4

Granville

Person

Vance

Warren

14 Franklin 2 88,557 27.5 24.8 82.8 17.1 0.1

Johnston _

15 Wake 6 228,453 22.6 10.1 85.9 14.1 0.0

16 Durham 3 132,681 32.9 11.9 76.1 23.7 0.2

17 Chatham 2 87,261 22.4 11.3 83.9 16.1 0.0

Orange t

18 Harnett 2 80,134 ' 24.4 18.0 85.1 14.8 0.1

Lee

19 Bladen 3 118,368 35.2 i 26.6 74.9 23.7 1.4

_Columbus

Sampson

20 Cumberland S 212,042 26.5 a 13.9 78.6 21.4 0.0

21 IHoke .3 128,207 52.9 24.6 V 50.3 25.4 24.3

_Robeson 9'

Scotland

22 Alamance 4 168,764 19.0 10.2 87.6 21.3 0.0

Rockingham

23 Guilford 7 288,590 22.5 8.9 84.4 15.6 0.0

Exhibit II-B

Page 3 -- North Carolina General AsSembly State Representative Districts

District # Counties

24 Randolph

25 Moore

26 Anson

Montgomery

27 Richmond

28 Allegheny

Ashe

Stokes

Surry

Watauga

29 Forsyth

30 ’Davidson

Davie

31 Rowan

32 Stanly

33 .Cabarrus

, Union

34 Caldwell

Wilkes

Yadkin

35 Alexander

Iredell

36 ’Mecklenburg

37 Catawba

38 Gaston

Lincoln

Estimate of

# of Rep. Total Pop. 4 Non-White % Poor % White Voters ' Black Voters Indian 8 Other

2-. 76,358 7.4 9.9 95.6 4.4 0.0

1 39,048 . 25.1 . 19.0 86.1 13.9 0.0

_1 42,755 36.8 22.0 79.0 21.0 0.0

1 39,889 29.7 ' 19.9 74.1 25.8 0.0

3 126,306 4.4 19.4 96.5 3.5 0.0

5 214,348 22.5 10.7 79.9 20.0 0.1

3 114,482 10.3 11.0 91.6 8.3 0.0

2 90,035 16.1 , 10.3 89.9 10.1 0.0

1 42,822 11.0 10.4 93.0 7.0 0.0

3 (129,343 17.4 . 10.4 89.3 10.7 0.0

3’ 130,822 5.7 15.9 95.5 4.5 0.0

' 2 91,663 '15.2 11.4 92.0 8.0 0.0

8 354,656 24.1 g 8.9 , ' 83.9 16.1 0.0

2 90,873 8.9 7.5 93.1 6.9 0.0

4 181,097 11.9 9.7 91.6 8.4 0.0

. . Exhibit II-D

Page 4 -- North Carolina General Assembly State Representative Districts

Estimate of

District # Counties 0 of Rep: 'Total Pop. % Non~White % Poor % White Voters % Black Voters 8 Indian 6 Other

39 Avery 2 86,466 5.3 15.4 96.5 3.5 0.0

'Burke ,

Mitchell

40 Cleveland 3 131,628 16.4 14.8 - 92.6 7.4 0.0

Polk

Rutherford

41 McDowell 1 43,277 4.2 19.6 96.9 3.1 0.0

Yancey

42 Henderson 1 42,804 4.7 21.0 97.1 2.9 0.0

43 Buncombe 4 - 164,769 8.7 13.4 93.7 6.3 0.0

Transylvania

LN

H

44 Haywood 2 87,167 ' 5.1 ’ 21.5 95.7 1.2

Uackson

Madison

Swain

45 Cherokee 1 43,860 2.8 26.3 98.6'- 0.9 0.5

Clay 4 .

Graham

Macon

”—1

,1 'Exhibit II—E

North Carolina General Assembly

State Representative Districts

1970 1977 Est. Present Estimated

Total Pop. Variance From Variance From

District Population Addition 1 Person, 1 Vote 1 Person, 1 Vote

1 74,856 10,273 -11.6. - .48

2 ,. 41,551 3,623 - 1.98 - .78

3 ‘137,004 10,148 + 7.88 +6.78

4 134,729 17,324 + 6 8 +10.38

5 76,590 444 - 9. 8 -16.18

6 78,614 1,678 - 7. 8 -12.68

7 168,949 9,797 - 8 - .88

8 88,867 5,960 + 4. 8 + 3.28

9 85,408 5,429 + .88 + 1.28

10 38,015 2,029 -10. 8 -12.98

11 42,372 11,914 + 1. 8 +18.18

12 82,996 13,923 - 2. 8 +5.48

13 126,232 4,048 - . 8 -5.58

14 88,557 5,503 - + 4.68 +2.68

15 228,453 44,005 -10.18 -1.28

16 132,681 10,463 + 4. 8 +3.88

17 87,261 11,966 +.3. 8 +7.98

18 80,134 8,966 — 5. 8 -3.18

19 118,368 10,551 - 6. 8 -6.58

20 212,042 18,875 + .18 + .48

21 128,207 13,923 + . 8 +3.08

22 168,764 6,045 — . 8 ~5.08

23 288,590 15,643 - 2. 8 -5.58

24 76,358 6,953 - 8. 8 -9.48

25 39,048 4,689 ~ 7. 8 -4.98

26 42,755 489 + .98 -6.08

27 39,889 1,928 - 5. 8 -9.18

28 126,306 15,954 - . 8 +3.28

29 214,348 13,315 + 1. 8 -1.08

30 114,482 9,096 -10. 8 -10.48

31 90,035 2,686 + 6. 8 +.88

32 42,822 2,027 + 1.18 -2.48

33 129,343 13,220 + 1. 8 +3.48

34 130,822 11,594 + 2. 8 +3.38

35 91,663 8,505 + 8. 8 +9.08

36 354,656 22,494 + 4. 8 +2.68

37. 90,873 8,849 + 7.38 +8.58

38 181,097 11,829 + 6. 8 +4.98

39 86,466 5,455 + 2. 8 0.08

40 131,628 10,204 + 3. 8 +2.98

41 43,277 4,863 + 2. 8 +4.78

42 42,804 7,811 + 1. 8 +10.08

43 164,769 8,814 — 2.88 -5.68

44 87,167 8,814 + 2. 8 +4.48

45 43,860 5,000 + 3.6° +6.38