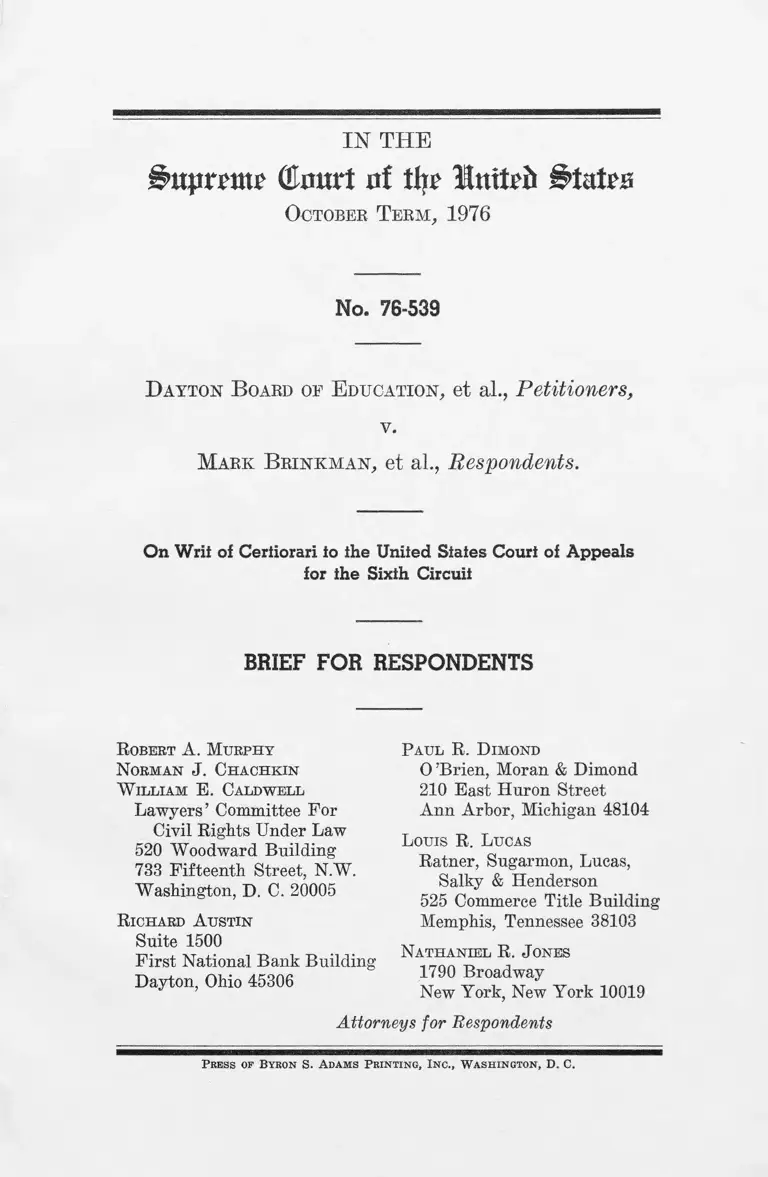

Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman Brief for Respondents

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1976

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman Brief for Respondents, 1976. 48a31b71-af9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2be1e01b-6f53-4a15-8474-382f44f563a4/dayton-board-of-education-v-brinkman-brief-for-respondents. Accessed February 28, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

^uprrmr Court of thr Inttrfc

October Term, 1976

No. 76-539

D ayton B oard of E ducation, et al., Petitioners,

v .

Mark B rinkman, et al., Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals

for the Sixth Circuit

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS

Robert A. Murphy

Norman J. Chachkin

W illiam E. Caldwell

Lawyers’ Committee For

Civil Rights Under Law

520 Woodward Building

733 Fifteenth Street, N.W.

Washington, D. C. 20005

Richard A ustin

Suite 1500

First National Bank Building

Dayton, Ohio 45306

Paul R. D imond

O ’Brien, Moran & Dimond

210 East Huron Street

Ann Arbor, Michigan 48104

Louis R. Lucas

Ratner, Sugarmon, Lucas,

Salky & Henderson

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

Nathaniel R. Jones

1790 Broadway

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Respondents

P ress of Bykon S. A dams P kinting, Inc., W ashington , D. C.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

T able of A u th o rities ............................................................... iii

P r elim in ar y S tatem en t .......................................... 1

C o u nterstatem ent of Q uestions P r e s e n t e d ................. 3

S tatem en t of th e Case ............................................................. 3

A. Prior Proceedings ............................................... 3

B. The Dayton District ........................................... 7

C. The Pre-Brown Dual System............................... 8

D. Continuation of the Dual System After Brown.. 20

1. Faculty and Staff Assignments ..................... 20

2. Optional Zones and Attendance Boundaries 24

3. The Board’s Rescission of Its Affirmative

Duty ........................................................ 30

E. The District Court’s Decision and Supplemental

Order on Remedy ......................................... 35

P. Brinkman I ........................................................ 43

G. Remedial Proceedings ...................................... 45

S u m m a r y of A rg u m en t ............................................................. 55

A rg u m en t .............................................................. 56

I. The Board Operated a Basically Dual School

System at the Time of Brown Which Was Not

Disestablished Prior to Implementation of the

Desegregation Plan Ordered Below ................. 58

A. A Dual System Existed in the Dayton Pub

lic Schools at the Time of Brown I .................. 61

B. The Board Never Complied With Brown II 68

Page

11 Table of Contents Continued

Page

II. Alternatively, Plaintiffs Made Out an Unre-

bntted Prima Facie Case of System-Wide In

tentional Segregation Requiring a Similar

Remedy ............................................................. 72

A. Plaintiffs’ Made Out a Prima Facie Case of

System-Wide De Jure Segregation............... 72

B. The Board Has Failed to Rebut Plaintiffs’

Prima Facie C ase........................................ 79

III. The System-Wide Desegregation Plan Ordered

Below Does Not Impose a Fixed Racial Balance

as a Matter of Substantive Constitutional Right,

and the Plan Contains No Other Impermissible

Features ............................................................. 85

A. The Courts Did Not Order a Fixed Racial

Balance Either for Now or for E v er ......... 87

B. The Board’s Resegregation Argument Is

Wrong .......................................................... 93

IV. Plaintiffs Have Standing to Bring This Case in

Their Own Right and as Representatives of the

Class ................................................................... 95

Conclusion ................................................................................. 101

A ppendix A ................................................................ la

1. School Construction, Closing and Site Selection. . la

2. Grade Structure and Reorganization.................... 4a

3. Pupil Transfers and Transportation.................... 5a

A ppendix B 11a

Table of Authorities iii

Cases: Page

Adams v. Richardson, 480 F.2d 1159 (D.C. Oir. 1973)

(en banc) ......................................................... 31n

Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of Educ., 396 U.S.

19 (1969) .............................................. 90n

Armstrong v. Brennan, 539 F.2d 625 (7th Cir. 1976). . 66n

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249 (1953) ...................... lOOn

Baxter v. Savannah Sugar Refining Co., 495 F.2d 437

(5th Cir.), cert, denied, 419 U.S. 1033 (1974)....... 81n

Berenyi v. District Director, 385 U.S. 630 (1967).......... 81n

Board of Educ. v. State, 45 Ohio St. 555, 16 N.E. 373

(1888) ......................................... .......................... 8

Board of Educ. of School Dist. of City of Dayton v.

State ex rel. Reese, 114 Ohio St. 188, 151 N.E. 39

(1926) ................................................ 11

Board of School Comm’rs v. Jacobs, 420 U.S. 128

(1975) .................................................................... 99

Bradley v. Milliken, 484 F.2d 215 (6th Cir. 1973) (en

banc), aff’d in part & rev’d in part, 418 U.S. 717

(1974) ............................................................. 66n, 75n

Brinkman v. Gilligan, 539 F.2d 1084 (6th Cir. 1976),

cert, granted sub nom., - ---- - U.S. —— (Jan. 17,

1977)............................................................... 2, passim

Brinkman v. Gilligan, 518 F.2d 853 (6th Cir.), cert, de

nied sub nom., 423 U.S. 1000 (1975) ............ 2, passim

Brinkman v. Gilligan, 503 F.2d 684 (6th Cir. 1974) 2, passim

Brown v. Board of Educ., 349 U.S. 294 (1955) .. .3, passim

Brown v. Board of Educ., <347 U.S. 483 (1954) . . 56, passim

Brown v. Weinberger, 417 F.Supp. 1215 (D.D.C. 1976). 31n

Castaneda v. Partida, 45 U.S.L.W. 4302 (U.S. March

23, 1977) ............................................................... 65n

Clemons v. Board of Educ. of Hillsboro, 228 F.2d 853

(6th Cir. 1956) ...................................................... 65n

Cooper v. Allen, 467 F.2d 836 (5th Cir. 1972) ............ 81n

Cooper y. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) ......................... 56, 93

Costello v. United States, 365 U.S. 265 (1961) ........... 81n

Dandridge v. Williams, 397 U.S. 471 (1970) .............. 73n

Davis v Board of School Comm’rs, 402 U.S. 33 (1971)

41, 59n, 69

Day v. Mathews, 530 F.2d 1083 (D.C. Cir. 1976)...... 81n

Drummond v. Acree, 409 U.S. 1228 (1972) ................ 86n

Gonzales v. London, 350 U.S. 920 (1955) .................... 81n

Green v. County School Bd., 391 U.S. 430 (1968)....

58, 70, 71, 72

IV Table of Authorities Continued

Page

Hart v. Community School Bd. of Educ., 512 F.2d 37

(2d Cir. 1975) .................................................. .. . 66n

Higgins v. Board of Educ. of City of Grand Rapids,

508 F.2d 779 (6th Cir. 1974) ............................. 46, 47

Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S. 385 (1969) .............. 78n, 81n

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire <& Rubber Co., 491 F.2d 1364

(5th Cir. 1974) ...................................................... 81n

Kelsey v. Weinberger, 498 F.2d 701 (D.C. Cir. 1974).. 31n

Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, 413 U.S. 189 (1973).. 3, passim

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967) ......................... 81n

McDaniel v. Barresi, 402 U.S. 39 (1971) ............. 59n, 7In

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 254 (1964) .............. 81n

Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1974) .................... 87n

Monroe v. Board of Comm’rs, 391 U.S. 450 (1968) . . . .

56, 58n, 70, 93

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1961) ......................... 68n

Morgan v. Kerrigan, 509 F.2d 580 (1st Cir. 1974), cert.

denied, 421 U.S. 963 (1975) .................................. 66n

New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254 (1964). . 81n

North Carolina State Bd. of Educ. v. Swann, 402 U.S.

43 (1971) ................................................. 59n, 71n, 77n

Nowak v. United States, 356 U.S. 660 (1958) ............. 81.n

Nyquist v. Lee, 402 U.S. 935 (1971), aff’g 318 F.Supp.

710 (W.D. N.Y. 1970) (three-judge court) ......... 77n

Oliver v. Michigan State Bd. of Educ., 508 F.2d 178

(6th Cir. 1974), cert, denied, 421 U.S. 963 (1975)

66n, 84

Pasadena City Bd. of Educ. v. Spangler, 427 U.S. 424

(1976) .................................... 54, 56, 88n, 92, 98, 99 100

Pettivay v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 404 F.2d 211

(5th Cir. 1974) ...................................................... 81n

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896) .................... 68

Potts v. Flax, 313 F.2d 284 (5th Cir. 1963) ................ lOln

Raney v. Board of Educ., 391 U.S. 443 (1968) ........... 58n

Rodrigues v. East Texas Motor Freight, 505 F.2d 40

(5th Cir. 1974), cert, granted, 44 U.S.L.W. 3670

(U.S. May 24, 1976) ..............................................lOOn

Schneiderman v. United States, 320 U.S. 118 (1943)... 81n

Senter v. General Motors Corp., 532 F.2d 511 (6th Cir.

1976) .......................................................................lOOn

Shapiro v. Thompson, 394 U.S. 618 (1969) .............. 84n

Smith v. Board of Educ., 365 F.2d 770 (8t,h Cir. 1966) 95

Sosna v. Iowa, 419 U.S. 393 (1975) ............................. 99

Table of Authorities Continued v

Page

Stanton v. Stanton, 45 U.S.L.W. 3506 (U.S. Jan. 25,

1977) .............. ...................................................... 63n

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402

U.S. 1 (1971) ............................................... 40, passim

Trafficante v. Metropolitan Life Ins. Go., 409 U.S. 205

_ (1972) .............................' ......................................lOOn

United States v. Board of School Comm’rs, 322 F.

_ Supp. 655 (S.D. Ind. 1971) ................................. 12n

United States v. Chesterfield County School Dist., 484

_ F.2d 70 (4th Cir. 1973) ...........'............................. 81n

United States v. Montgomery County Bd. of Educ.,

395 U.S. 225 (1969) ....................'.......................... 23

United States v. New York, N.H. & H.R.R., 355 U.S.

253 (1957) .................. ' ......................................... 78n

United States v. School Dist. of Omaha, 521 F.2d 530

(8th Cir.), cert, denied, 423 U.S. 946 (1975).. 66n, 75n

United States v. Texas Educ. Agency, 467 F.2d 848

(5th Cir. 1972) (en banc) .................................... 75

Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing

Dev. Corp., 45 U.S.L.W. 4073 (U.S. Jan. 11, 1977)

65n,78n

Warth v. Seldin, 422 U.S. 490 (1975) ....................... 98

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976) .................

65n, 71n, 78n, 81n

Whitely v. Wilson City Bd. of Educ., 427 F.2d 179 (4th

Cir. 1970) .............................................................. lOOn

Woodby v. Immigration & Naturalisation Service, 385

U.S. 276 (1966) ..._.............................................. 81 n

Wright v. Council of City of Emporia, 407 U.S. 451

(1972) .............................................. 71n

Statutes and Rules:

20 U.S.C. §§ 1701 et seq. (Equal Educational

Opportunities Act of 1974) ............................. 46, S6n

20 U.S.C. §1702(b) .................................................. 46, 86n

28U.S.C. § 1292(b) ...................................................... 46

42 U.S.C. § 1981 ........................................................... 4

42 U.S.C. §§ 1983-1988 ................................................ 4

42 U.S.C. § 2000d (Title VI of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964) ...................................................... 4, 23, 30, 74

O hio R ev . C ode § 3319.01 ............................................. 34n

85 O hio L aw s 34 . ........................................................................... 8

Rule 23, F ed. R. C iv . P..................................... 96, 99, lOOn

Rule 53, F ed . R. C iv . P. ............................................... 50

Rule 801(d) (2), F ed. R. E vid.......................................... 99

Other Authorities:

C. M cC o rm ick , L aw or E vidence (1954) ....... ........... 81n

M oore ’s F ederal P ractice (2d ed. 1974) ............. 97, lOOn

J. W igmore, E vidence (3d ed. 1940) .................... 78n, 81n

McBain, Burden of Proof: Degrees of Relief, 32 Calie .

L. R ev. 242 (1944) ......................................... 81n, 82n

Note, Reading the Mind of the School Board: Segre

gative Intent and the De Facto/De Jure Distinc

tion, 86 Y ale L.J. 317 (1976) ............................... 65n

Notes of the Advisory Committee on 1966 Amend

ments to Rule 23 ................................................... lOOn

Ohio Attorney General Opinion No. 6810 (July 9,

1956) ....................................................................... 32n

vi Table of Authorities Continued

Page

IN THE

§it*imue (Burnt irl % WnxUb §tnte$

October Term, 1976

No. 76-539

D ayton B oard of E ducation, et al., Petitioners,

Y .

Mark B rinkman, et al., Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals

for the Sixth Circuit

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

At least two good things are happening in Dayton,

Ohio, this school year for the first time ever. Black

and white children are attending public school to

gether in significant numbers, and their attendance in

this fashion is pursuant to a desegregation plan which

is fair and equitable to both races and demeaning to

neither. Second, the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution as appli

cable to public education is receiving substantial vindi

cation in the Dayton school district. These happy re-

2

suits derive from unhappy circumstances; longstand

ing policies and practices of de jure segregation re

quiring federal judicial intervention. This lawsuit has,

to date, produced numerous hearings, opinions and or

ders in the district court, three appeals and one denial

of certiorari. The case appears considerably more com

plex than it actually is, however, primarily because the

district judge grappled most ineffectively with settled

constitutional principles and terminology and most re

luctantly with the facts. But the essential determina

tive facts have been found by the courts below or they

are uncontestable. On the basis of these facts, the

United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

Court has, on three separate occasions, adjudged plain

tiffs’ constitutional right to a system-wide remedial

plan of pupil desegregation based on the nature and

extent of the violation. Brinkman v. Gilligan, 503 F.2d

684 (6th Cir. 1974) [hereinafter, “ Brinkman I ” ] ; 518

U2d 583 (6th Cir.) [“ Brinkman I / ” ], cert, denied stib

nom., 423 U.S. 1000 (1975) ; 539 F.2d 1084 (6th Cir.

1976) [“ Brinkman I I I ” ], cert, granted sub nom.,------

U.S. —- (1977) (the instant case). Following Brink-

man I I the district court appointed a Master and,

upon receipt of his report, ordered into effect a plan

of desegregation which has considerable potential for

uprooting two-thirds of a century of unabated state-

inflicted racial separation in the Dayton public schools.

That plan has been approved in Brinkman I I I as a

fair, sensitive, flexible and otherwise equitable re

sponse to the entrenched constitutional wrong.

In proper perspective, therefore, this case raises the

following:

3

COUNTERSTATEMENT OF QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Did the Dayton Board of Education meet its bur

den of showing that it dismantled the basically dual

school system inherited at the time of Brown v. Board

of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), following which the

system-wide racial segregation extant at the time of

trial adventitiously reappeared'?

2. Did the Dayton Board, under Keyes v. School

District No. 1, 413 U.S. 189 (1973), rebut plaintiffs’

prima facie case of system-wide intentional segrega

tion1?

3. I f the Dayton Board failed to meet either of these

burdens, did the system-wide remedial plan of pupil

desegregation approved below require a fixed racial

balance or otherwise constitute an abuse of equitable

discretion ?

4. Do plaintiffs have standing to bring this action

in their own right and as representatives of the class *?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. Prior Proceedings

Black and white parents and their minor children

attending the Dayton, Ohio public schools, and the

Dayton Branch of the National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People [hereinafter, “ plain

tiffs” ], filed their complaint April 17, 1972 in the

United States District Court for the Southern District

of Ohio. Defendants included the Dayton Board of

Education and its individual members, and the Super

intendent of the Dayton Public Schools [hereinafter

“ petitioners” or “ Dayton Board” or “ Board” ], and

the Governor, Attorney General, State Board of Edu

4

cation and Superintendent of Public Instruction of

Ohio [hereinafter, “ State defendants” ].1 Plaintiffs

alleged that all of these defendants were responsible

for operating a racially segregated public school sys

tem in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment and

federal civil rights statutes, 42 U.S.C. §§1981, 1983-

1988, and 2000d.

Trial limited by the district court to whether the

Dayton public schools are unlawfully segregated by

race pursuant to actions of the Dayton Board began

November 13, 1972 and concluded on December 1. On

February 7, 1973 the district court issued its Findings

of Fact and Memorandum Opinion of Law concluding

that various actions on the part of the Dayton Board

defendants and their predecessors “ are cumulatively

in violation of the Equal Protection Clause.” A .12.2

The Court thereupon ordered the Dayton Board to

1 The State defendants are not parties to this appeal, as no

orders have been entered against them below. The State Superin

tendent and the State Board of Education have, however, filed an

amicus brief with this Court, the principal purpose of which

appears to be to get this Court to prejudge an issue now pending

in the district court: a motion filed by the Dayton Board seeking

an order requiring the State defendants to participate in the

implementation of the desegregation plan ordered below. We cau

tion only that the figures set out in the State Board’s amicus brief

(pp. 2-3) have not been tested in the adversary process, and no

assumptions about them are warranted.

2 “ A . ------ ” references are to the printed two-volume appendix.

With respect to matters not included in the appendix, we cite to

the original record in the same manner employed by petitioners.

See Pet. Br. at 17n.l. “ R .I.” refers to the pages in the con

secutively-paginated twenty-volume transcript of the November-

December, 1972 violation trial; “ R .II.” to the transcript of the

February 1975 remedial hearing; and “ R .III.” to the December

1975 and March 1976 remedial hearing. “ P X ” refers to plain

tiffs’ evidentiary exhibits and “ D X ” to those of defendants.

5

submit a remedial plan of desegregation; the Dayton

Board purported to comply through a submission of

March 29, 1973. A.131-44. By its Supplemental Order

on Remedy filed July 13, 1973 (A.25-31), the district

court, while expressing disappointment at the Board’s

submission, approved the Board’s limited proposal on

a tentative basis. Both plaintiffs and defendants ap

pealed.

On August 20, 1974 the Court of Appeals for the

Sixth Circuit filed its opinion in Brinkman 1, 503 F.2d

684 (A.32-69). The court of appeals affirmed the dis

trict court’s finding that the Dayton school system

was being operated in violation of the Constitution,

but the court of appeals also concluded that the

Board’s proposed cure for that violation was inade

quate in light of the scope of the violation. A.68. Ac

cordingly, the case was remanded to the district court

to formulate a constitutionally adequate desegregation

plan. The Dayton Board did not seek review in this

Court of the judgment in Brinkman I.

On remand the district court, by order of January

7, 1975 (A.70-72), directed the submission of new de

segregation plans, upon which (A.144, 154) a hearing

was held on February 17, 19 and 20, 1975. On March

10, 1975 the district court entered an Order provision

ally adopting another limited plan submitted by the

Board. A.73-84. The plaintiffs immediately appealed

seeking summary reversal on the ground that the plan

and the reasoning adopted by the district court wrnre

plainly inadequate and in direct conflict with the man

date of the court of appeals.

On June 24, 1975 the court of appeals issued its

opinion in Brinkman II, 518 F.2d 853 ( A.89-96). The

court denied plaintiffs’ motion for summary reversal

6

because of the short time remaining before commence

ment of the 1975-76 school year; but the court re

manded the case with directions that the district court

“ adopt a system-wide plan for the 1976-77 school

year that will conform to the previous mandate of

this Court and to the decisions of the Supreme Court

in Keyes and Sivann.” A.96. The court of appeals di

rected that its mandate issue forthwith. The Dayton

Board sought review in this Court, and certiorari was

denied on December 1,1975. 423 U.S. 1000. On remand,

following evidentiary hearings and the appointment

of a Master, the district court entered an order on

March 23 (A .110-13) and a judgment on March 25 (A.

114-16), modified by order of May 14, 1976 (A .117),

essentially adopting the desegregation plan recom

mended by the Master but granting the Board the

option to implement equally effective alternatives.

Defendants’ appeal was heard on an expedited basis,

and the court of appeals issued its decision in Brink-

man I I I on July 26, 1976, 539 F.2d 1084 (A.118-23).

The court rejected the Board’s objections to the plan

of desegregation approved by the district court. The

court of appeals and Circuit Justice Stewart denied

the Board’s applications for stay on August 16 and

August 19, 1976, respectively. The plan thus became

operative at the start of the 1976-77 school year, as

required by Brinkman I I and confirmed by Brinkm.an

III. This Court granted the Dayton Board’s petition

for a writ of certiorari on January 17, 1977.

The various opinions and orders below will be de

scribed in greater detail as they appear chronologically

in the remainder of this Statement. Part B provides a

summary overview of the Dayton school district. Parts

C and D below then describe the facts adduced at the

7

November 1975 violation trial. (The facts relating to

violation issues which have been reserved for decision

by the court of ajjpeals are summarized in Appendix

A, attached hereto.) The remaining parts summarize

the lower courts’ opinions and orders, as well as the

facts adduced at the remedial hearings which are per

tinent to the disposition of the case in this Court.

B. The Dayton District

As reflected in the report (A.157-58) of the Master

appointed by the district court, the city of Dayton,

Ohio, has a population of 245,000 and is located in the

east-central part of Montgomery County in the south

western part of the state o f Ohio, approximately 50

miles due north of Cincinnati. The Dayton school dis

trict is not coterminus with the city ; some parts of the

school district include portions of three surrounding

townships and one village, while some portions of the

city are included in the school districts of three ad

jacent townships. The total population residing within

the Dayton school district boundaries is 268,000; the

school pupil population in 45,000, slightly less than

50% of whom are black. Prior to implementation of

the desegregation plan here at issue, the vast majority

of black and white pupils had separately attended

schools either virtually all-white or all-black in their

pupil racial composition. E.g., A. 49-51, 311-315 (P X

2A-2E), 502-506 (P X 100A-100E), 588-589 (D X C U ).

The Dayton district is bisected on a nortk/south line

by the Great Miami River. Historically, the black

population has been concentrated in the south-central

and southwest parts of the city, primarily on the west

side of the Miami River and south of the east-west

W olf Creek. See A.577-79 (1940, 1950 and 1960 census

8

tract maps). The black population continues to be con

centrated in the southwest quadrant, but there is now

also a substantial black population in the northwest

quadrant across W olf Creek. Extreme northwest Day-

ton and most of the city east of the Miami River are

and have been heavily white in residential racial com

position. See A .580 (1970 census tract map).

Geographically and topographically there are no

major obstacles to complete desegregation of the Day-

ton school district. A .121. The Master determined that

where pupil transportation is necessary, the maximum

travel time would be about twenty minutes. A .162. As

found by the Board’s experts, due to the compact na

ture of the system, “ the relative closeness of the Day-

ton Schools makes long-haul transportation[,] an

issue in many cities[,] moot here.” A.304. Thus, there

is no issue whether the time or distance of transporta

tion is here excessive or otherwise poses any threat

to the health or education of pupils.

C. The Pre-Brown Dual System

In 1887 the state of Ohio repealed its school segre

gation law and attempted to legislate the abolition of

separate schools for white and black children. 85 Ohio

Laws 34. That statute was sustained the following year

by the Supreme Court of Ohio. Board of Education v.

State, 45 Ohio St. 555, 16 N.E. 373 (1888). The laud

able goals of that legislation wrere not attained in Day-

ton until the current school year.

The facts of racial segregation in the Dayton public

schools, as revealed by the record before the Court,

begin in 1912.3 In that year school authorities assigned

3 Many of the facts set forth in this part of the statement were

admitted by all Dayton Board defendants in their responses to

9

Louise Troy, a black teacber, to a class of all-black

pupils just inside the rear door of the Garfield school;

all other classes in this brick building were occupied

by white pupils and white teachers. About five years

later, four black teachers and all of the black pupils

at Garfield were assigned to a four-room frame house

located in the back of the brick Garfield school build

ing with its all-white classes. Shortly thereafter, a two-

room portable was added to the black “ annex” mak

ing six black classrooms and six black teachers located

in the shadow of the white Garfield school. A four-

room “ permanent” structure was later substituted

(about 1921 or 1922), and eight black teachers were

thus assigned to the eight all-black classrooms in the

Garfield annex. A.209-11.4

About 1925 school authorities learned that two black

children, Robert Reese and his sister, had been at

plaintiffs ’ pre-trial Requests for Admissions, served on October 13,

1972. The Superintendent and three Board members filed responses

separate from those of the Board and its four “ majority” mem

bers. These facts were also the subject of extensive and largely

uncontroverted evidence at trial.

4 In 1917 the black classes in the black annex at Garfield con

tained about 50 black children per room. A.210. Thereafter, Mrs.

Ella Lowrey, a black teacher for several decades in the Dayton

system, taught a class of 42 black children when white teachers

inside the brick building had classes of only 20 white pupils.

A.211.

Mrs. Lowrey’s service began in 1916 and continued through

1963, with several years’ interruption at various times. In her

words, “ doing 40 years service in all in Dayton, . . . I never

taught a white child in all that time. I was always in black

schools, black children, with black teachers.” A .215. (At one time

during this early history prior to 1931, one black teacher, Maude

Walker, taught an ungraded class of all-black boys at the Weaver

school. All other black teachers in the system were assigned to the

black annex at Garfield. A. 186.)

10

tending the Central school under a false address, even

though they lived near the Garfield school. They had

accomplished this subterfuge by walking across a

bridge over the Miami River River. A.197.6 The Reese

children were ordered by school authorities to return

to the Garfield school, but their father refused to send

them to the black Garfield annex. Instead, he filed a

lawsuit in state court seeking a writ o f mandamus to

compel Dayton school authorities to admit children

of the Negro race to public schools on equal terms with

white children. A. 198. In a decision entered of record

on December 24, 1925, the Court of Appeals of Ohio

denied a demurrer to the mandamus petition. This de

cision was affirmed by the Ohio Supreme Court and

5 During this time, there apparently were some other black

children also in “ mixed” schools. For example, Mrs. Phyllis

Greer attended “ mixed” classes at Roosevelt high school for three

years prior to 1933. A .182. Bid; even when they were allowed to

attend so-called “ mixed” schools, black children were subjected

to humiliating discriminatory experiences within school. At Roose

velt, for example, black children were not allowed to go into the

swimming pool and blacks had separate showers while Mrs. Greer

was there (A. 183-83); while Robert Reese was at Roosevelt, there

were racially separate locker rooms and blacks were allowed to

use the swimming pool, but not on the same day whites used it

A.198-99. At Steele High School, black children were not allowed

to use the pool at all during this period. A.290-91.

Even in the “ mixed” classrooms black children could not escape

the official determination that they were inferior beings because

of the color of their skin. Mrs. Greer vividly remembers, for ex

ample, “ when I went to an eighth grade social studies class I was

told by a teacher, whose name I still remember, . . . that even

though I was a good student I was not to sit in front of the

class because most of the colored kids sat in the back.” A .183.

And she remembers with equal clarity that, while in the second

grade at Weaver, she “ tried out for a Christmas play and my

teacher wanted me to take the part of an angel and the teacher who

was in charge of the play indicated that I could not be an angel

. . . because there were no colored angels.” R.I.479.

11

Dayton school authorities were specifically reminded

that state law prohibited distinctions in public school

ing on the basis of race. Board of Education of School

District of City of Dayton v. State ex rel. Reese, 114

Ohio St. 188, 151 N.E. 39 (1926).

Following this state court decision Robert Reese

and a few of his black classmates were allowed to at

tend school in the brick Garfield building, but the black

annex and the white brick building were otherwise

maintained. Black children were allowed to attend

classes in the brick building only if they asserted them

selves and specifically so requested. A .212-13. Other

wise, they “ were assigned to the black teachers in the

black annex and the black classes. ’ ’ A.213.6

The black pupil population continued to grow at

Garfield, and another black teacher was hired and as

signed with an all-black class placed at the rear door

of the brick building. A.213. In 1932 or 1933, Mrs.

Lowrey (see note 4, supra), was also placed in the

brick building, again with an all-black class “ in a little

cubbyhole upstairs,” making ten black teachers with

ten black classes at Garfield. A .214. Finally, around

1935-36, after most of the white children had trans

ferred out of Garfield, school authorities transferred

all the remaining white teachers and pupils in the

brick building to other schools and assigned an all

6 During the pendency of the Reese case, the eight black teachers

assigned to the Garfield annex were employed on a day-to-day

basis because school authorities did not know whether the black

teachers were going to be in the Dayton system after the lawsuit.

Black teachers would not be needed if the courts required the

elimination of all-black classes, since the Board deemed black

teachers unfit to teach white children under any circumstances.

A.211-12.

12

black faculty and student body to Garfield. A .186-187,

214-15, 524 (P X 150 I ) ; P X 155 (faculty directories).7

But the black pupil population was growing during

these years, and even the conversion of Garfield into

a blacks-only school was not sufficient to accommodate

the growth. So, with the state court decision in the

Reese case now eight years old, the Dayton Board con

verted the Willard school into a black school. The

conversion process was as degrading and stigmatizing

as had been the creation and maintenance of the Gar

field annex and the ultimate conversion of the brick

Garfield into a black school. In the 1934-35 school year,

six black teachers (who were only allowed to teach

black pupils) and ten white teachers had been assigned

to the Willard school. In September of 1935, all white

teachers and pupils were transferred to other schools,

and Willard became another school for black teachers

and black pupils only. A. 186-87, 524 (P X 150 I ) ; P X

155 (faculty directors).

At about this same time, the new Dunbar school,

with grades 7-9, opened with an all-black staff and an

all-black student body. A.524 (P X 150 I ) .8 The Board

7 Throughout this period and until 1954, black children from a

mixed orphanage, Shawn Acres, were assigned across town to the

black classes in the black G-arfield school, while the white orphan

children were assigned to nearby white classes and white schools.

A .181-82. This practice was terminated following the Brown deci

sion in 1954 at a time when the black community in Dayton was

putting pressure on the school administration to stop mistreating

black children. A.483 (P X 28).

8 Mr. Lloyd Lewis, who was present at its inauguration, testified

that the Dunbar school “ was purposely put there to be all black

the same as the one in Indianapolis [the Crispus Attacks school,

see United States v. Board of School Comm’rs, 332 P. Supp. 655,

665 (S.D. Ind. 1971)] that I had left.” R.I. 1378. Dunbar was

13

resolution opening Dunbar stated that grades 7 and

8 were to be discontinued at Willard and Garfield9 and

“ that attendance at the . . . Dunbar School be optional

for all junior high school students of the 7th, 8th, and

9th grade levels in the city.” A.227, 539 (P X 161 A ).

Of course, this meant only all Hack junior high stu

dents, since Dunbar had an all-black staff who were

not permitted by Board policy to teach white children.

A.186, 228; P X 155 (faculty directors).

Within a very short time, grades ten, eleven and

twelve were added to the black Dunbar school. Then in

1942, just two years after the Dayton school authori

ties had reorganized to a K-8, 9-12 grade structure,

the Board again assigned the seventh grades from the

all-black Willard and Garfield schools to the all-black

Dunbar school. A.227, 520 (P X 161 B ). Black chil

dren from both the far northwest and northeast sec

tions of the school district traveled across town past

many all-white schools to the Dunbar school. A .190;

E.I. 1226-27. Many white children throughout the west

side of Dayton were assigned to Boosevelt high school

past or away from the closer but all-black Dunbar high

school. See P X 47 (overlay of 1957 attendance boun

daries).10 Although some black children were allowed

also excluded from competition in the city athletic league until

the late 1940’s, thereby requiring Dunbar teams to travel long

distances to compete with other black schools, even those located

outside the state. A.183, 205-06; R.I.569-70.

9 These two black elementary schools served grades 7 and 8,

whereas the system prior to 1940 was otherwise generally organized

on a K-6, 7-9, 10-12 grade-structure basis. R.I. 1871.

i° p rior to 1940, no high schools had attendance boundaries.

R.I.1886. The black Dunbar school was located in close proximity

to the Roosevelt high school (see PX 47) which, although it always

had space, apparently had too many black children. Along with

14

to attend Roosevelt, those who became “ behavior

problems” were transferred to Dunbar. A .184. And

other black children from various elementary schools

were either assigned, channeled, or encouraged to at

tend the black Dunbar high school. A.238-39, R.I. 574!1

Even these segregative devices were not sufficient to

contain the growing black pupil population. So be

tween 1943 and 1945, the Board, by way of the same

gross method utilized to convert the Willard school 11

Steele and Stivers, these high schools were located roughly in the

center of the city and served high school students throughout the

city. (In addition, the Parker school had been a city-wide single

grade school which served ninth graders. R.I.1921-22; A.288-89.)

In 1940 attendance boundaries were drawn for the high schools

with the exception of Dunbar and a technical school (whose name

varied), both of which long thereafter remained as city-wide

schools. See note 22, infra, and accompanying text.

Dunbar continued until 1962 as a city-wide all-black high school.

In that year the Dunbar building was converted into an elemen

tary school (renamed McFarlane) with attendance boundaries

drawn to take in most of the students previously attending the

all-black Williard and Garfield schools, which were simultaneously

closed. McFarlane opened with an all-black faculty and all-black

pupil population. At the same time, a newly-constructed Dunbar

high school opened with both asigned faculty and students over

90% black. A.315 (P X 2E), 316 (PX 4), 508 (PX 130C), 248;

PX3.

11 The most effective means of forcing black children to attend

the blacks-only Dunbar, of course, was the psychological one of

branding them unsuited for association with white children. See

note 5, supra. As Mr. Reese testified, he “ chose” Dunbar over

Roosevelt after suffering the humiliation of being assigned to

separate locker rooms, separate showers, and separate swimming

pools at Roosevelt: “ I wanted to be free. I felt more at home at

Dunbar than I did at Roosevelt . . . You couldn’t segregate me

at Dunbar.” A.199. Similarily, Mrs. Greer testified: “ I went to

Dunbar because I felt that if there was going to be— if we were

going to be separated by anything, we might as well be separated

by an entire building as to be separated by practices.” A.183.

15

into a black school, transformed the Wogaman school

into a school officially designated unfit for whites.

White pupils residing in the Wogaman attendance

zone were transferred by bus to other schools, to which

all-white staffs were assigned. By September 1945 the

Board assigned a black principal and an all-black fac

ulty with an all-black student population to the Woga

man school. A.183-84, 200, 524 (P X 1501); P X 155

faculty directories).

Still other official devices were used to keep blacks

segregated in the public schools. One such, device, re

sorted to regularly during the 1940’s and early 1950’s,

was to cooperate with and supplement the discrimina

tory activities of Dayton public housing authorities.

Throughout this period, racially-designated public

housing projects were constructed and expanded in

Dayton. A .178-79, 510 (P X 143 B ). In 1942, the Board

transferred the black students residing in the black

DeSoto Bass public housing project to the Wogaman

school (A.540 (P X 161 X ) ) , and a later overflow to

the all-black Willard school, rather than other schools

that were equally close (A .185), while transferring

white students from the white Parkside public hous

ing project to the McGuffey and Webster schools and

the eighth grades from those schools to the virtually

all-white Kiser school. A.540. Then in the late 1940’s

and early 1950’s, the Board leased space in white and

black public housing projects for classroom purposes,

and assigned students and teachers on a uniracial basis

to the leased space so as to mirror the racial composi

tion of the public housing projects. A.179-80, 513-23

(P X 143 J ).

By the 1951-52 school year (the last year prior to

1964 for which enrollment data by race is available),

16

the Dayton Board was operating what southern edu

cators would immediately recognize as a dual school

system. During that year there were 35,000 pupils en

rolled in the Dayton district, 19% of whom were black.

There were four all-black schools, officially designated

as such: Willard, Wogaman, Garfield and Dunbar.

These schools had all-black faculties and (with one

exception, an assignment made that school), no black

teachers taught in any other schools. P X 3. In addi

tion, there were 22 white schools with all-white facul

ties and all-white student bodies. And there was an

additional set of 23 so-called “ mixed” schools, 7 of

which had less than 10 black pupils and only 11 of

which had black pupil populations greater than 10%

(ranging from 16% to 68%). A.506 (P X 100E).

These latter schools were generally located in the area

surrounding the location of the 4 designated all-black

schools. These few schools with substantial racial mix,

however, were marked by patterns of racially segre-

gatory and discriminatory practices within the school,

and, with the one exception noted above, none had any

black teachers. Eighty-three percent of all white pu

pils attended schools that were 90%, or more white in

their pupil racial composition. Of the 6,628 black pu

pils in the system, 3,602 (or 54%) attended the four

all-black schools with all-black staffs; and another

1,227 (or 19%) of the system’s black pupils were as

signed to the adjacent schools which were about to be

converted into “ black” schools ( see note 12, infra, and

accompanying text). Thus, 73% of all black students

attended schools already or soon to be designated

‘ ‘ black. ’ ’

In December 1952 the Dayton Board confronted its

last pre-Brown opportunity to correct the officially-

imposed school segregation then extant. Instead, the

17

Board acted in a manner that literally cemented in the

dual system and promised racially discriminatory pub

lic schooling for generations to come. What the Board

did is referred to in the record as the West-Side Re

organization, and it involved a series of interlocking

segregative maneuvers.

At this time, the Board was under pressure, as its

record reflect, from “ the resistance of some par

ents to sending their children to school in their dis

trict because it is an all negro [sic] school.” A.499

(P X 75). In response, the Board constructed a nevT

all-black school (Miami Chapel) located near the all-

black Wegaman school and adjacent to the black De-

Soto Bass public housing project; Miami Chapel

opened in 1953 with an all-black student body and an

85% black faculty. A.316 (P X 4). The Board altered

attendance boundaries so that some of the children

in the four blaeks-only schools were reassigned to the

four surrounding schools with the next highest black

pupil populations; and, through either attendance

boundary alterations or the creation of optional zones,

it reassigned white students from these mixed schools

to the next ring of whiter schools. A .257-65, 283-84;

P X 123.12 And the Board began to assign black teach

12 The boundaries of the black Garfield and Wogamon schools

were retracted, thereby assigning substantial numbers of black

children to the immediately adjacent ring of “ mixed” schools

with the highest percentage of black pupils: Jackson (already 36%

black in the 1951-52 school year), Weaver (68% black), Edison

(43% black), and Irving (47% black). A .506 (P X 100E). Jack-

son and Edison were re-zoned to include more black students, and

their outer boundaries were effectively contracted through the

creation of “ optional zones” so that white residential areas be

came attached, for all practical purposes, to the next adjacent

ring of “ whiter” schools. Thus, the Board brought blacks in one

end and allowed whites to escape out the other in these “ transi-

18

ers to these formally mixed schools, thereby confirm

ing their identification as schools for blacks rather

than whites. A.259-60; P X 3.

This latter aspect of state-imposed segregation—

i.e., faculty assignments on a racial basis “ pursuant

to an explicit segregation policy of the Board” (A.56)

—also underwent a slight change in school board pol

icy. Prior to this time, as previously noted, the Board

would not allow black teachers to teach white children

under any circumstances; black teachers were assigned

only to all-black schools, and white teachers were as

signed only to white and “ mixed” schools. Accord

ingly, in the 1951-52 school year, the Board substituted

a new, but equally demeaning, faculty assignment

policy (A.481 (P X 21)) :

The school administration will make every ef

fort to introduce some white teachers in schools

in negro [sic] areas that are now staffed by ne

groes [sic], but it will not attempt to force white

teachers, against their will, into these positions.

The administration will continue to introduce

negro [sic] teachers, gradually, into schools hay

ing mixed or white populations when there is evi

dence that such communities are ready to accept

negro [sic] teachers.

tion” schools. The Board also created optional zones in white

residential areas contained within the boundaries of the original

four schools for blacks only, so that whites could continue to

transfer out of these all-black schools. A.257-65. Prior to 1.952

whites had been freely allowed to transfer to “ whiter” schools,

but such transfers were abolished in 1952. A.262, 482 (P X28).

Optional zones were thus substituted for the prior segregatory

transfer practice. (The optional-zone technique is discussed in

greater detail at pages 24-30, infra.

19

This faculty policy, incredibly, was contained in a

statement of the Superintendent disavowing the ex

istence of segregated schools in the Dayton district.1,1

At the time of this Court’s May 17, 1954 decision in

Brown v. Board of Education, therefore, Dayton

school officials were operating a racially dual system

of public education. This segregation had not been

imposed by state law; indeed, it was operated in open

defiance of state law.

13 In 1954 the Superintendent made a further statement, which

included the following: “ All elementary schools have definite

boundaries and children are obliged to attend the school which

serves the area in which they reside. The policy of transfers from

one school to another was abolished two years ago when the

boundaries of several westside elementary schools were shrunken,

permitting a larger number of Negro children to attend mixed

schools.” A.482 (P X 28). As we have seen (see note 12, supra),

however, the elimination of free transfers was accompanied by a

new device, optional zones, which served the same purpose of

allowing whites to avoid attendance at black or substantially black

schools.

The Superintendent’s 1954 statement also contains the followr-

ing (A.483) :

About two years ago we announced a policy of attempting

to introduce white teachers in our schools having negro [sic]

population. We have not been too successful in this regard

and at the present time have only 8 full or part-time teachers

in these situations. There is a reluctance on the part of white

teachers to accept assignments in westside schools and up to

the present time we have not attempted to use any pressure

to force teachers to accept such assignments. The problem of

introducing white teachers in negro [sic] schools is more dif

ficult than the problem of introducing negro [sic] teachers

into white situations. There are several all-white schools which

in the near future will be ready to receive a negro [sic]

teacher.

As we shall also show (see pages 20-24, infra), this raee-based as

signment of faculty continued for almost twro more decades as a

primary device for earmarking schools as intended for blacks or

whites.

20

D. Continuation of the Dual System After Brown

Consideration of the Board’s segregatory conduct

following this Court’s decision in Brown may he di

vided into six general areas: (1) faculty and staff

assignments, (2) optional zones and attendance boun

daries, (3) Board rescission of a Board-adopted plan

of desegregation, (4) school construction, closing and

site selection, (5) grade structure reorganization, and

(6) pupil transfers and transportation. W e summar

ize seriatim the facts relating to the first three areas.

The facts pertaining to the latter three areas, and

their legal significance, have been contested by the

Board, and the court of appeals has reserved decision

with respect to these practices. Since in our view dis

position of this issue is not essential to affirmance of

the judgment below, we have summarized the facts re

lating to these latter three areas in Appendix A, at

tached hereto.14

1. Faculty and Staff Assignments

The Board continued to make faculty and staff as

signments in accordance with the racially discrimina

tory policy announced in 1951 (see page 18, supra)

14 One of the three areas discussed in this part of the State

ment—faculty and staff assignments—was discussed by the court

of appeals in Brinkman 1 in part IV of its opinion, entitled ‘ 1 Other

Alleged Constitutional Violations,” on which the court reserved

decision. A.56-67. But “ Staff Assignment” (A.56-61) is included

in that part of the opinion only because of plaintiffs’ contention,

implicitly rejected by the district court (see page 37, infra), that

staff assignments at the time of trial continued to be made on a

racially discriminatory basis. It is clear from the court of appeals’

unqualified determination of the pre-1971 facts pertaining to staff

assignments that the appellate court did not consider these prac

tices to be the subject of dispute or of adverse district court find

ings. See note 47, infra.

21

at least through the 1970-71 school year. For example,

in the 1968-69 school year, the Board assigned 633

(85%) of the black teachers in the Dayton system to

schools 90% or more black in their pupil racial com

positions, but only 172 (9% ) of the white teachers to

such schools. The Board assigned only 72 (9% ) of the

black teachers to schools which were 90% or more

white, but 1,299 (70%) of the white teachers were

assigned to such schools. A.320 (P X 5D).

Prior to the 1968-69 school year, the Board main

tained teacher applications on a racially separate

basis. Once teachers were hired, their records were

kept on various racial bases which were used to segre

gate teachers and schools. Substitute teacher files were

color-coded by race and substitutes assigned on a

racially dual basis. And the Board restricted the hir

ing, transfer, and promotion of black teachers pri

marily to black or “ changing” schools while white

assignments or transfers to these schools were dis

couraged. A.191-95, 201, 204-05, 187-91; P X 3; R.I.

673-88, 536-542, 731-35, 742,50, 762-69. Principals, as

sistant principals, counselors, coaches and other cleri

cal and classified personnel were assigned on an even

more strictly segregated basis. A.486 (P X 42), 234,

191-93. Thus, from at least 1912 through 1968 the as

signment of personnel in the Dayton school system

fit perfectly the classical mold of state-imposed segre

gation: such assignments mirrored the racial compo

sition of student bodies at new schools and additions,15

and continued to correspond to the racial identity of

15 The Board assigned faculty members to these new schools and

additions so as to reflect the pupil racial composition at opening,

thereby tailoring them as “ black” or “ white” in accordance with

the Board’s policy. A.316-17 (P X 4), 275; R.I.1860.

22

those schools already all-black or in transition.16 White

teachers similarly were assigned in disproportionate

numbers to the predominantly white schools.17 It was

therefore possible at anytime during this period to

identify a “ black” school or a “ white” school any

where in the Dayton system without reference to the

racial composition of pupils.

In November of 1968 the United States Department

of Health, Education and Welfare [hereinafter,

“ H E W ” ] began an investigation of the Dayton public

schools to determine whether official policies and prac

16 In the 1963-64 school year, for example, the Board assigned

40 of 43 new full-time black teachers to schools more than 80%

black in their racial compositions. A .319 (P X 5A). Although

somewhat less obvious, this practice was equally effective in

identifying the formerly mixed schools as changing or black by

assigning more than token black faculty only to these schools and

thereafter assigning increasing numbers of black teachers only

to these schools. P X 3; A .195-97, 224. As articulated by Mrs.

Greer, a long-time black student, teacher and administrator in

the system (see note 5, supra), the “ assignment of staff to go

along with the neighborhood change was the kind of thing that

gave the impression of the schools being designed to be black,

because black staff increased as black student bodies increased.”

A .191.

17 Thus, for example, in the 1968-69 school year, the Board con

tinued to assign new teachers and transfers according to the fol

lowing segregation practice (A .319 (P X 5 A ) ) :

Schools with

predominantly

white student

enrollment

Schools with

predominantly

Mach student

enrollment

Black Teachers 40 95

White Teachers 223 64

As the Superintendent testified, “ it is obvious in terms of the

new hires and transfers for that year the predominating pattern

was the assignment of black teachers to black schools and white

teachers to white schools.” A.233.

23

tices with respect to race were in compliance with

Title V I of the Civil Eights Act of 1964. By letter of

March 17, 1969, the Acting Director for the Office of

Civil Rights of H EW notified the Dayton Superin

tendent (and the chief state school officer) that “ [a]n

analysis of the data obtained during the [compliance]

review establishes that your district pursues a policy

of racially motivated assignment of teachers and other

professional staff.” A.415 (P X H A ). Following this

determination the Dayton Board agreed with H EW

to desegregate all staff so “ that each school staff

throughout the district will have a racial composition

that reflects the total staff of the district as a whole”

(A.416 (P X 11F)), in accordance with the principles

set forth in this Court’s decision in United States v.

Montgomery County Board of Education, 395 U.S. 225

(1969). At that time, the Dayton professional staff

was approximately 70% white and 30% black; the

Board-HEW agreement required complete staff de

segregation by September 1971. A.417. Nevertheless,

by the time of trial in November 1972, it was still pos

sible to identify many schools as “ black schools” or

“ white schools” solely by the racial pattern of staff

assignments.18

No non-racial explanation for the Board’s long his

tory of assigning faculty and staff on a racial basis is

possible.19 Nor can the impact of this manifestation of

18 The manner in which the Board’s assignment of its profes

sional staff at the high school level, for example, still served to

racially identify schools, athough considerably less dramatically

than prior to the 1971-72 school year, is demonstrated by a table

set out by the court of appeals in Brinkman I. A.57. Moreover,

classified personnel (e.g., secretaries, clerks, custodians and cafe

teria workers) continued to be assigned on a racially segregated

basis. A .234.

19 School officials, of course, had absolute control over the place-

24

state-imposed segregation on student assignment pat

terns by minimized. While that effect is not precisely

measurable, it is so profound that it could not have

been eliminated merely by desegregating faculties and

staffs.20

2. Optional Zones and Attendance Boundaries

W e have already shown how the Dayton Board uti

lized optional zones and attendance boundary manipu

lation as segregative devices in connection with the

1952 West-Side Reorganization (see pages 16-18, su

pra). There are additional examples of both practices

which stand on their own as segregation techniques.

Optional zones are dual or overlapping zones which

allow a child, in theory, a choice of attendance between

two or more schools. A.241. Yet, the criteria stated by

the Board for the creation of both attendance boun

daries and optional zones are precisely the same: they

constitute merely a type of boundary decision and

ment of their employees. Consequently, the Board’s historic race-

oriented assignments of faculty members intentionally earmarked

schools as “ black” or “ white.” A.274.

20 Dr. Robert L. Green, Dean of the Urban College and Pro

fessor of Educational Psychology at Michigan State University,

described how such faculty-assignment practice “ facilitates the

pattern of segregation” (A.197) in these terms (A .195):

When there has been historical practice of placing black

teachers in schools specified as being essentially black schools

and white teachers in schools that are identified or specified

as being essentially white schools, even though faculty de

segregation occurs, be it on a voluntary basis or under court

order, the effect remains that school is yet perceived as being

a black school or white school, especially if at this point in

time the pupil composition of those schools are essentially

uni-racial or predominantly black or predominantly white.

See also A.274-75.

serve no other educational or administrative purpose.

A.238, 279. Optional zones have existed throughout the

Dayton school district and have apparently been cre

ated whenever the Board is under community pressure

which favors attendance at a particular school or dis

favors attendance at a particular school. A.254; R.I.

1818-19. Other than for such purely “ political” rea

sons, there is no rationale which supports the estab

lishment of an optional zone rather than the creation

of an attendance boundary, which is a more predict

able pupil-assignment device (A.280) ; and optional

zones are at odds with the so-called “ neighborhood

school concept.” A.12-13.

In many instances in Dayton optional zones were

created for clear racial reasons, as, for example, in the

West-Side Reorganization, while in other instances

the record reveals no known reason for their existence.

But even in these latter instances some optional zones

have had clear segregative effects. From 1950 to the

time of trial, optional zones existed, at one time or

another, between pairs of schools of substantially dis

proportionate racial compositions in some fifteen in

stances directly effecting segregation at some 30

schools.21 In addition, at the high school level, Dunbar

remained in effect a city-wide optional zone for blacks 23

23 The West Side Reorganization in 1952-53 (see pages 16-18,

supra) involved six optional areas with racial implications: Wil-

lard-Irving, Jackson-Westwood, Willard-Whittier, Miami Chapel-

Whittier, Wogamon-Highview, and Edison-Jefferson. A .252-53,

257-65; see also note 12, supra. Other optional zones with demon

strable racial significance at some time during their existence

include the following: Three optional zones between Roosevelt and

the combination Fairview-White; two optional zones between Resi

dence Park and Adams; and optional zones between Westwood

and Gardenclale, Colonel White and Kiser, Fairview and Roth,

Irving and Emerson, Jefferson and Brown, and Jefferson and

Cornell Heights. A.250, 253-54, 255, 268-69, 279-83; PX 47-51.

26

only through 1962 when it was converted into an all

black elementary school (A.248, 269-71) (see note 10,

supra) ; and Patterson Co-Op remained a city-wide

and, through the 1967 school year, virtually all-white

optional attendance zone.22 In conjunction with the

attendance-area high schools, these two special high

schools operated as city-wide dual overlapping zones

contributing to the pattern of' racially dual schools at

the high school level throughout the district. See R.I.

1518-21, 1483-84.

Actual statistics on the choices made by parents and

children in four optional areas are available. In each

instance the option operated in the past, and in three

instances at the time of trial, to allow whites to trans

fer to a “ whiter” school. For example, in the Roose-

velt-Colonel White optional area, which was carved

out of Roosevelt originally, from the 1959-60 school

year through the 1963-64 school year a cumulative

total o f 1,134 white but only 21 black students at

tended Colonel White. A.464 (P X 15A1). Testimony

from a Dayton school administrator indicates that

from 1957 through 1961, although this optional area

was predominantly white, black students who lived in

the area attended Roosevelt which had become virtu

ally all-black (Colonel White was 1% black). A .221-22.

22 The city-wide Patterson Co-op operated in a more subtle segre

gative fashion than did Dunbar. In 1951-52, Patterson had no

black students and no black teachers (A .507 (P X 130B )); by

1963 its student body and faculty were only 2% black (A .508

(P X 130C)) ; and by 1968 the pupil population rose to 18.3%

black and the faculty to 3.5% black. A .509 (P X 130D). Students

were admitted to Patterson through a special process involving’

coordinators and counselors, none of whom were black prior to

1968. A .286-88. Patterson has over the years served as an escape

school for white students residing in black or “ changing” at

tendance zones, particularly Roth and Roosevelt. R.I. 1483-84.

27

The Roosevelt yearbook for 1962 shows that only three

white seniors from the optional area attended the

black high school. A.462 (P X 15A). As Mrs. Greer

testified, this optional area did “ an excellent job of

siphoning off white students that were at Roosevelt.”

A.190.23

Although many of these still-existing optional zones

had already fulfilled their segregative purpose by the

time of trial, over time they clearly contributed sub

stantially to and facilitated school segregation.

Moreover, even by the time of trial several of these

optional areas continued to permit whites to escape

to “ whiter” schools, thereby further impacting the

black schools and precipitating additional instability

and transition in residential areas.24

23 As another example, the Colonel White-Kiser option acquired

its racial implications after its creation in 1962 with the racial

transition of the Colonel White school, to which the Colonel

White-Roosevelt option contributed in no small measure. At its

inception and for several years thereafter, wThen both schools were

virtually all-white, most children in the White-Kiser option area

chose White. As Colonel White began to acquire more black stu

dents, whites chose Kiser more often until in the 1971-72 school

year, no white children chose the 46% black Colonel White school,

while 20 chose the 6% black Kiser school. A.465 (P X 15B1), 554.

The rebuttal figures provided by the defendants on the Resi

dence Park-Jackson optional area are equally instructive, because

the figures relate to a time when the optional area did not even

exist by reason of the construction of the virtually all-black Carl

son school and its assumption of the old Veterans Administration

optional area as its regular attendance zone. A .586, 587. In any

event, defendants’ exhibit shows that from 1957 through 1963

no children from the former V.A. optional area attended Jackson,

while 32 whites (and 8 blacks) attended Residence Park. In the

1957-58 school year, Residence Park was basically white and Jack-

son was black. A.250-51; R.I. 377. (By 1961, however, Residence

Park had become 80% black. A .508 (P X 130C).)

24 Prom 1968 through 1971, when Roosevelt was a 100% black

Formal attendance boundaries, in conjunction with

optional zones, have also operated in a segregative

fashion; and in some instances firm boundaries were

also drawn along racial lines.* 25 An example is the

boundary separating Roth and Roosevelt which was

drawn in 1959. Roth took almost all the white resi

dential areas on the far west side of Dayton from

Roosevelt. At its opening, Roth had only 662 pupils,

while Roosevelt’s enrollment dropped by 602. Coupled

with the exodus of whites out of Roosevelt through

the Colonel White-Roosevelt optional area, almost all

whites were thereby transferred out of Roosevelt by

school, for example, 375 white children from Roosevelt-Colonel

White optional area attended Colonel White. A.464. Throughout

its life, then, this option has allowed very substantial numbers of

white children to avoid attending Roosevelt. By 1968, however, and

not atypically, the optional area had undergone significant racial

change and substantial numbers of black children were also at

tending Colonel White. A.462-64. Plaintiffs’ expert, Dr. Poster,

explained how optional attendance areas facilitate both educational

and racial segregation:

[T]he short term effect . . . is to allow whites to move out of

a school assignment that is becoming black . . . [A.255],

[(generally where you have an optional zone which has

racial implications, you have an unstable situation that every

one realizes is in a changing environment. So, what it usually

does is simply accelerate whatever process is going on or work

toward the acceleration of the changing situation . . . [T]hese

[optional areas in Dayton] accelerated and precipitated furth

er segregation . . . [A.254-55].

25 In some instances, and in addition to the official optional zones,

attendance boundaries have not been enforced for white children

when assigned to black schools. For example, a pupil locator map

made to assist in developing a middle school plan in the 1970-71

school year showed that many white children assigned by their at

tendance zone to the predominantly black Greene school were ac

tually attending predominantly white schools located on the other

side of W olf Creek. R.1.1210-11. A similar situation existed in the

Carlson area. See note 23, supra.

29

Board action, in short order converting Roosevelt into

a virtually all-black school. A.268-69; P X 48 & 46.

(And, of course, the designation of Roosevelt as a

black school was evidenced, in the traditional way, by

assigning ever-increasing numbers of black teachers

to the school. P X 3.)

At about this same time, Meadowdale high school

also opened, but as a virtually all-white school. A.3T7

(P X 4). Opportunities were available for the place

ment of such high schools and use of the excess capa

city or the redrawing of the boundaries of Roth,

Roosevelt, Stivers, Fairview and Meadowdale in order

to accomplish desegregation. But school authorities

selected the alternatives that continued rather than

alleviated the extreme racial segregation at the high

school level. R.I. 1696-1700; P X 6; A.249, 268-69. This

pattern was capped in 1962 when a new Dunbar high

school opened with a virtually all-black faculty and a

defined attendance zone that produced a virtually all

black student body. At the same time the Board con

verted the old Dunbar high school building into an

elementary school (renamed McFarlane), whose

newly-created attendance zone took in most of the stu

dents in the zones for the all-black Williard and Gar

field schools, which were closed. See note 10, supra.

Finally, the Board also persistently refused to re

draw boundaries between, or pair, contiguous sets of

schools which had been, and were at the time of trial,

substantially disproportionate in their racial compo

sitions. Examples of such contiguous pairs include

Drexel (8% black) and Jane Adams (79% black) ;

McGuffey (42%: black) and Webster (1% black) or

Allen (1 % black) ; Irving (99% black) and Emerson

(9% black); Whittier (99% black) and Patterson

30

(0% black). P X 68, 62. Suck alternatives to segrega

tion—many of which were recommended by subordi

nate school administrators and even the Ohio State

Department of Education (A.204-05, 419-55 (P X 12))

—-were rejected by the Board.

3. The Board’s Recission of Its Affirm,alive Duty

As reflected in the foregoing pages, black citizens

o f Dayton have been thwarted in their attempts to end

state-imposed racial segregation in their public

schools. Even aggressive action, such as that taken by

Robert Reese’s father when he went to court in 1926

to challenge intentional efforts to segregate his chil

dren, was effectively blunted by Dayton school authori

ties committed to separation of the races. See pages

9-12, supra. During another critical period, 1951-52,

the Board imposed the West-Side reorganization and

a new racially discriminatory faculty-assignment pol

icy. See pages 16-19, supra. The black community’s re

peated protests following B-roivn to the continued

segregation also were turned aside. See A.358-59, 456-

57, 459-61. By the late 1960’s, however, those who ob

jected to state-imposed school segregation began to

gain allies, both in the white community in Dayton and

among state and federal agencies. As previously noted

(see pages 22-23, supra), H EW conducted a Title V I

compliance review in 1968 and forced the Board in

1969 to agree to end its racially dual faculty-assign

ment practices. HE W had also noted the “ substantial

duality in terms of race or color with respect to distri

bution of pupils in the various schools . . . ” (A.415),

but the agency did not pursue this concern with simi

larly aggressive action.26

26 As is commonly known, from the frequent judicial declara

tions on the subject, HEW has generally failed to fulfill its Title

31

Also during these years, the Dayton Board, in the

1971 words of the State Department of Education,

“ passed various and sundry resolutions . . . designed

to equalize and to extend educational opportunities,

to reduce racial isolation, and to establish quality

integrated education in the schools.” A.423. But these

were just words and informal ones at that. As the

State Assistant Superintendent for Urban Education

noted at the same time, there was a definite need for

action and not just words. A.422.

On April 29, 1971, the Board requested assistance

from the State Department of Education’s Office of

Equal Educational Opportunities to provide technical

assistance in the development of alternative desegre

gation plans. The Board also authorized its President

to appoint a committee of community representatives

to assist and advise the Board in connection with such

proposed plans. A.354-55.

The State Department of Education responded by

assembling a team of consultants and specialists to

evaluate data and make recommendations. Their re

commendations were submitted to the Dayton Super

intendent on June 7, 1971. A.419-55. The State De

partment advised the Dayton Board of its constitu

tional and other legal obligations (A.435) (emphasis

in original) :

Since the Board, as an agency of state govern

ment, has created the inequality which offends VI

VI obligations with respect to pupil desegregation in both the

North and the South. See, e.g., Adams v. Richardson, 480 F.2d

1159 (D.C.Cir. 1973) (en banc) ; Broivn v. Weinberger, 417 F.

Supp. 1215 (D.D.C. 1976). And it has not been notably aggressive

even with respect to faculty segregation. See Kelsey v. Weinberger,

498 F.2d 701 (D.C.Cir. 1974).

32

the Constitution, the Ohio State Department of

Education must advise that the Dayton Board of

Education clearly has an affirmative duty to com

ply with the Constitution; that is, as the Supreme