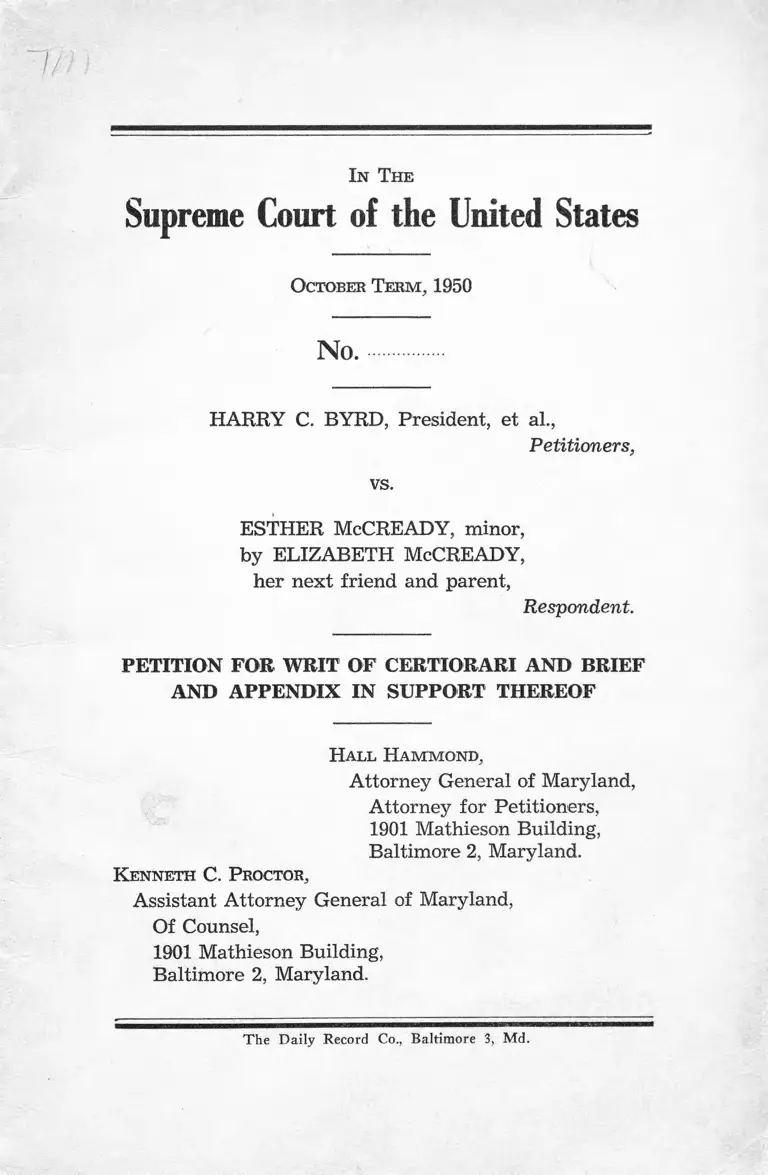

Byrd v McCready Petition for Writ of Certiorari and Brief and Appendix in Support of Brief

Public Court Documents

October 31, 1950

43 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Byrd v McCready Petition for Writ of Certiorari and Brief and Appendix in Support of Brief, 1950. 38c51343-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2de94b7d-cd0a-4f4c-8647-99d12397351a/byrd-v-mccready-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-and-brief-and-appendix-in-support-of-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n T h e

Supreme Court of the United States

O ctober T e r m , 1950

No.

HARRY C. BYRD, President, et al.,

Petitioners,

vs.

ESTHER McCREADY, minor,

by ELIZABETH McCREADY,

her next friend and parent,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI AND BRIEF

AND APPENDIX IN SUPPORT THEREOF

Hall Ham m ond ,

Attorney General of Maryland,

Attorney for Petitioners,

1901 Mathieson Building,

Baltimore 2, Maryland.

K e n n e t h C. P ro cto r ,

Assistant Attorney General of Maryland,

Of Counsel,

1901 Mathieson Building,

Baltimore 2, Maryland.

The Daily Record Co., Baltimore 3, Md.

I N D E X

(Petition for Writ of Certiorari)

Table of Contents

PAGE

I. Su m m a ry Statement of the Matter Involved 2

II. Jurisdictional Statement ................................. 4

III. Question Presented ...................................... 6

IV. Reasons for Granting the W rit........... 6

V. Transcript of Record and Supporting Brief 7

Table of Citations

Cases

Hinderlider v. LaPlata River & Cherry Creek Ditch

Co., 304 U. S. 92, 106, 82 L. Ed. 1202, 1210.......... 5, 6

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337, 83 L.

Ed. 208 ................................................................... 5,7

Poole v. Fleeger, 11 Pet. 185, 9 L. Ed. 680, 690 5

Sipuel v. Board of Regents of the University of Okla

homa, 332 U. S. 631, 92 L. Ed. 247......................... 5

University of Maryland v. Murray, 169 Md. 478 5

Virginia v. Tennessee, 148 U. S. 502, 517-519, 37 L. Ed.

537, 542-543 ........................................................ 5, 6

Wharton v. Wise, 153 U. S. 155, 171-173, 38 L. Ed.

669, 676 6

Statutes

Constitution of the United States, Fourteenth Amend

ment ...................................................................... 5,6

Laws of 1949, (Maryland) Chapter 282 2, 7

United States Code, Revised Title 28, Section 1257 (3) 4

11

I N D E X

(Brief)

Table of Contents

pa g e

Opinion in the Court Below ............................................ 9

Jurisdiction ............................................................................ 10

Jurisdictional Statement .............................................. 10

Statement of Facts ........................................................... 11

Errors Below Relied on He r e .......................................... 17

A rgument :

Did the Offer to Provide Nursing Education for

Miss McCready at Meharry Medical College,

Nashville, Tennessee, Under the Regional Com

pact, Afford to Her the Equal Protection of the

Laws Guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States? 17

Conclusion .............................................................................. 28

Table of Citations

Cases

Hinderlider v. LaPlata River & Cherry Creek Ditch

Co., 304 U. S. 92, 106, 82 L. Ed. 1202, 1210 11, 24-25

Maryland v. Murray, 169 Md. 478................................ 11, 29

McCready, minor, by Elizabeth McCready, etc. v.

Harry C. Byrd, President, et al, Court of Ap

peals of Maryland, October Term 1949, No. 139,

73 A. (2) 8 ............................................................. 9

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, No. 34, Octo

ber Term, 1949 ...................................................... 18

Ill

PAGE

Missouri, ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337, 83

L. Ed. 208 ........................................... 10, 11, 18, 26, 28, 29

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537, 41 L. Ed. 256 18

Poole v. Fleeger, 11 Pet. 185, 9 L. Ed. 680, 690 11, 24

Sipuel v. Board of Regents of the University of Okla

homa, 332 U. S. 631, 92 L. Ed. 247..............10-11, 26, 29

Sweatt v. Painter, et al, No. 44, October Term, 1949 18

Virginia v. Tennessee, 148 U. S. 502, 517-519, 37 L. Ed.

537, 542-543 .................................................. 11,21-23,24

Wharton v. Wise, 153 U. S. 155, 171-173, 38 L. Ed.

669, 676 ................................................................. 11,23

Statutes

Constitution of the United States:

Article I, Section 10, Clause 3............................ 19

Fourteenth Amendment ..................................... 10,17

Laws of 1949, (Maryland) Chapter 282 .................... 13, 18

United States Code, Revised Title 28, Section 1257 (3) 10

Miscellaneous

Congressional Record, Volume 95, No. 77, page 5588,

Tuesday, May 3, 1949 ........................................... 20

Conference Proceedings, 1949, page 69, National Asso

ciation of Attorneys General................................ 19

Report of Interstate Compact Committee—Penna.

Bar Assn., June, 1950........................................... 24

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1950

No.

HARRY C. BYRD, President, et al.,

Petitioners,

vs.

ESTHER MeCREADY, minor,

by ELIZABETH MeCREADY,

her next friend and parent,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE COURT

OF APPEALS OF MARYLAND

To the Honorable, the Justices of the Supreme Court

of the United States:

The Petitioners, Harry C. Byrd, President of the Uni

versity of Maryland, Edgar F. Long, Director of Admissions,

Florence Meda Gipe, Director of the School of Nursing, and

William P. Cole, Jr., et al, constituting the Board of Regents

of the University of Maryland, respectfully pray that a writ

of certiorari may issue to review the final decision of the

Court of Appeals of Maryland in this matter:

2

I .

SUMMARY STATEMENT OF THE MATTER INVOLVED

On February 8, 1948, the Governor of the State of

Maryland entered into a Compact, known as “The Regional

Compact” with the Governors of the States of Florida,

Georgia, Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee, Ark

ansas, North Carolina, South Carolina, Texas, Oklahoma,

West Virginia and the Commonwealth of Virginia. The

General Assembly of Maryland, by Chapter 282 of the Laws

of 1949 (Appendix to Brief, pp. 31-38), approved, con

firmed and ratified the Compact. As of October 10, 1949,

the date on which this case was tried below, the Compact

had been ratified and approved by the Legislatures of all

the signatory States with the exception of Texas, Virginia

and West Virginia and was in full force and effect (R. 18*).

The Regional Compact provides for education in the

professional, technological, scientific, literary and other

fields for all citizens of the several signatory States, re

gardless of race or creed, at regional educational institutions

in the Southern States. Under the Compact, the Board of

Control for Southern Regional Education and the Univer

sity of Maryland (hereinafter referred to as Maryland) en

tered into a contract for Training in Nursing Education,

dated July 19, 1949 (R. 14-17).

On February 2, 1949, the application of Esther McCready

for admission as a first year student in the School of

Nursing was received by the University of Maryland.

Miss McCready is a Negress, a citizen and resident of the

* The term “ Record” and the symbol “ R ” will be used to refer to

the printed portions of the record filed by the Petitioners with this

Court.

3

State of Maryland and of the United States of America.

At the time of filing said application, she was eighteen

years of age. Miss McCready’s educational and moral

qualifications were conceded to be at least equal to the

educational and moral qualifications of at least some of the

white students who were admitted to the Nursing School

class to which she had applied for admission. She was

concededly ready, able and willing to pay all fees and

expenses for her first year course of study and to conform

to all lawful rules and regulations governing first year

students at said School (R. 17). Not having been advised by

Maryland of any action on her application, on July 27,

1949, Miss McCready filed the Petition for Mandamus in

this case.

On August 13, 1949, Dr. Long, Director of Admissions

at Maryland, wrote Miss McCready concerning her appli

cation. She was advised of the existence and effect of The

Regional Compact. She was further advised that arrange

ments would be made so that she could attend the School

of Nursing at Meharry Medical College, Nashville, Tennes

see (hereinafter referred to as Meharry), the school at

which nursing education was to be provided under the

contract dated July 19, 1949, referred to above; that her

total expenses incident to attending Meharry, including

necessary travel and room and board, would not exceed

what it would cost her to attend Maryland; that she would

receive the same quality and kind of work at Meharry as

she would receive at Maryland. Miss McCready was further

advised that she should contact Dr. Long, who would in

form her of the procedure to be followed in applying for

admission to Meharry (R. 10-11).

It was stipulated at the trial of the case that the total

overall cost to Miss McCready, including living and travel- *

*

4

ing expenses incident to her attendance at Meharry, would

not exceed what it would cost her to attend Maryland

(R. 18). Evidence offered by Petitioners at the trial below

showed clearly that the educational facilities for nursing

education afforded at Meharry were at least equal to, if not

in fact superior to, the facilities offered at Maryland (R.

39-46; 53-55; 57-59). This evidence was not disputed or

contradicted in any way whatsoever by Miss McCready.

Miss McCready’s application for admission to Maryland

was not accepted solely because of the fact that she is a

member of the Negro race (R. 17).

II.

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

Petitioners bring this Petition pursuant to Section

1257(3) of Revised Title 28 of the United States Code.

A writ of certiorari is sought to review the final decision

entered on April 14, 1950, by the Court of Appeals of

Maryland, which is the highest Court of the State of Mary

land, in the case in the October Term, 1949, entitled No.

139, Esther McCready, minor, by Elizabeth McCready, her

next friend and parent v. Harry C. Byrd, President, et al

(R. 67-72).

The facts of the case and the rulings below which bring

the case within the jurisdictional requirement of Section

1257(3) are these:

The Petitioners, relying upon The Regional Compact

and the evidence adduced in the trial below, contended

that provision for Miss McCready’s nursing education at

Meharry would afford separate but equal facilities for

such education; that such provision did not in any way

deprive Miss McCready of the equal protection of the laws

and, therefore, did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment

<

of the Constitution of the United States. Miss McCready

contended that sending her to Meharry would deprive her

of the equal protection of the laws and, therefore, abridged

her constitutional rights.

The Court of Appeals of Maryland sustained the position

of Miss McCready by its decision filed on April 14, 1950.

Its decision was based solely upon the construction it placed

upon the decisions of this Court in the cases of Missouri,

ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337, 83 L. Ed. 208, and

Sipuel v. Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma,

332 U. S. 631, 92 L. Ed. 247. As a matter of fact, the decision

of the Court of Appeals of Maryland, except for a recital of

the facts and for a passing reference to the case of Univer-

sity of Maryland v. Murray, 169 Md. 478, consists entirely of

quotations from the decision of this Court in Missouri, ex

rel. Gaines v. Canada, supra.

The decision of the Court of Appeals of Maryland was

based upon dictum in Missouri, ex rel. Gaines v. Canada,

supra, indicating that separate but equal facilities must be

afforded within the jurisdiction of which the person seeking

such facilities is a citizen. The Court of Appeals of Mary

land incorrectly assumed that such dictum is an absolute

rule of law applicable in every case; that The Regional

Compact cannot, within the limits of the Constitution of

the United States, afford a means of providing “separate

but equal” educational facilities for members of the Negro

race. This decision was made in the face of declarations of

this Court to the effect that Compacts between the States

are binding upon all the citizens of such States. Virginia

v. Tennessee, 148 U. S. 502, 517-519, 37 L. Ed. 537, 542-543;

Poole v. Fleeger, 11 Pet. 185, 9 L. Ed. 680, 690; Hinderlider

v. La Plata River & Cherry Creek Ditch Company, 304

U. S. 92, 106, 82 L. Ed. 1202, 1210. This is the type of

5

6

Compact between the States which does not require the con

sent of Congress before it can be effective and binding.

Virginia v. Tennessee, supra, Wharton v. Wise, 153 U. S.

155, 171-173, 38 L. Ed. 669, 676.

III.

QUESTION PRESENTED

The question for review upon certiorari is:

Did the Offer to Provide Nursing Education for Miss

McCready at Meharry Medical College, Nashville, Tennes

see, Under The Regional Compact, Afford to Her the Equal

Protection of the Laws Guaranteed by the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States?

The Court of Appeals of Maryland, in reversing the

judgment of the Baltimore City Court answered this ques

tion in the negative. In this finding and conclusion, it is

submitted, there is error.

IV.

REASON FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

The reason relied on for the allowance of a writ of

certiorari in this case is summarized as follows:

The Court of Appeals of Maryland decided a Federal

question of substance not theretofore determined by this

Court. It was that in offering to provide nursing education

for Miss McCready at Meharry under The Regional Com

pact the University of Maryland was denying her the equal

protection of the laws; that a group of States cannot com

bine in a Compact for the purpose of providing regional

education and under such Compact effect segregation of

the races; that the latter statement is true even though

admittedly, as in this case, the facilities afforded at the

7

out-of-State institution are at least equal to the facilities

provided in the home State. It is true that this Court has

indicated by dictum in Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada,

supra, that to effectuate segregation of the races for

the purpose of education the equal facilities should be

provided in the jurisdiction of which the person seeking

an education is a citizen. However, it is equally true that

this Court has, on a number of occasions, held that such

segregation may be effected if equal facilities are pro

vided for the education of both races. Likewise, this Court

has held on a number of occasions that Compacts between

the States, if valid, are binding upon all of the citizens

of the several signatory States. This was held even though

such Compact was in derogation of the private rights of

such citizens. There is a pressing need for an adjudication

by this Court of the conflicting claims of the State of Mary

land and the Respondent as to the effect of The Regional

Compact and the offer of the University of Maryland to

afford nursing education for the Respondent at Meharry.

V.

TRANSCRIPT OF RECORD AND SUPPORTING BRIEF

Petitioners have already submitted to this Court a certi

fied copy of those portions of the record which were printed

for the use of the Court of Appeals of Maryland and of

the record of proceedings of said Court. Petitioners submit

herewith a brief in support of this Petition, and as an

appendix to said brief, for the convenience of this Court,

Chapter 282 of the Laws of 1949 of the State of Maryland.

W herefore, your Petitioners respectfully pray that a

writ of certiorari be issued out of and under the seal of

this Honorable Court, directed to the Court of Appeals of

Maryland, commanding that Court to certify and to send

to this Court for its review and determination, on a day

8

certain to be therein named, a full and complete transcript

of the record and all proceedings in the case numbered

and entitled on its docket as No. 139, October Term, 1949,

Esther McCready, minor, by Elizabeth McCready, her next

friend and parent v. Harry C. Byrd, President, et al; and

that the said judgment of the Court of Appeals of Mary

land may be reversed by this Honorable Court and that

your Petitioners may have such other and further relief

in the premises as to this Honorable Court may seem meet

and just.

And your Petitioners will ever pray.

Hall Ham mond ,

Attorney General of Maryland,

Attorney for Petitioners,

1901 Mathieson Building,

Baltimore 2, Maryland.

K enneth C. Proctor,

Assistant Attorney General of Maryland,

Of Counsel,

1901 Mathieson Building,

Baltimore 2, Maryland.

9

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1950

No.

HARRY C. BYRD, President, et al.,

Petitioners,

vs.

ESTHER McCREADY, minor,

by ELIZABETH McCREADY,

her next friend and parent,

Respondent.

BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF PETITION FOR WRIT

OF CERTIORARI

OPINION IN THE COURT BELOW

The Opinion of the Court of Appeals of Maryland has not

as yet been reported officially. It appears at 73 A (2d) 8

and at pages 67-72 of the Record.* The Opinion of the

Baltimore City Court was an oral one and appears at pages

27-34 of the Record.

* The term “ Record” and the symbol “ R ” will be used to refer to

the printed portions of the record filed by the Petitioners with this

Court.

10

JURISDICTION

The statutory provision is Section 1257(3), Revised Title

28, United States Code.

The final decision of the Court of Appeals of Maryland

reversing the judgment of the Baltimore City Court was

entered on April 14, 1950. The Court of Appeals of Mary

land is the Court of last resort for the State of Maryland

and, as such, meets the test of Section 1257(3), Revised

Title 28, United States Code and Rule 38 of this Court.

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

The nature of the case and the rulings below which bring

the case within the jurisdictional requirement of Section

1257(3) appear from the following:

The Petitioners, relying upon The Regional Compact

and the evidence adduced in the trial below, contended that

provision for Miss McCready’s nursing education at Me-

harry would afford separate but equal facilities for such

education; that such provision did not in any way deprive

Miss McCready of the equal protection of the laws and,

therefore, was not in violation of the Fourteenth Amend

ment of the Constitution of the United States. Miss Mc

Cready contended that such provision would deprive her

of the equal protection of the laws and would, therefore,

abridge her rights under that Amendment.

The Court of Appeals of Maryland sustained the position

of Miss McCready by its decision filed on April 14, 1950.

Its decision was based solely upon the construction placed

by it upon the decisions of this Court in the cases of

Missouri, ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U, S. 337, 83 L. Ed.

208, and Sipuel v. Board of Regents of the University of

11

Oklahoma, 332 U. S. 631, 92 L. Ed. 247. As a matter of fact,

the decision of the Court of Appeals of Maryland, except

for the recital of the facts involved and for a passing refer

ence to the case of University of Maryland v. Murray, 169

Md. 478, consists entirely of quotations from the decision

of this Court in Missouri, ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, supra.

The decision of the Court of Appeals of Maryland was

based upon dictum in Missouri, ex rel. Gaines v. Canada,

supra, indicating that separate but equal facilities must

be afforded within the jurisdiction where the person seek

ing such facilities is a citizen. The Court of Appeals of

Maryland incorrectly assumed that such dictum is an abso

lute rule of law applicable in every case; that The Regional

Compact cannot, within the limits of the Constitution of

the United States, afford a means of providing “separate

but equal” educational facilities for members of the Negro

race. This decision was made in the face of declarations

of this Court to the effect that Compacts between the

States are binding upon all the citizens of such States.

Virginia v. Tennessee, 148 U. S. 502, 517-519, 37 L. Ed. 537,

542-543; Poole v. Fleeger, 11 Pet. 185, 9 L. Ed. 680, 690;

Hinderlider v. La Plata River & Cherry Creek Ditch Com

pany, 304 U. S. 92, 106, 82 L. Ed. 1202, 1210. This is

the type of Compact between the States which does not re

quire the consent of Congress before it can be effective and

binding. Virginia v. Tennessee, supra; Wharton v. Wise,

153 U. S. 155, 171-173; 38 L. Ed. 669, 676.

STATEMENT OF FACTS

The facts in this case are either admitted or uncontra

dicted. They may be summarized as follows:

Esther McCready (herein referred to as “Respondent” ),

a Negress, eighteen years of age, a citizen and resident of

the State of Maryland and of the United States of America,

12

duly filed her application, dated February 1, 1949, for ad

mission as a first year student in the School of Nursing of

the University of Maryland (herein referred to as “Mary

land” ) for the academic year beginning August 8, 1949.

That application was received by the proper authorities of

the University of Maryland on February 2, 1949. This

School is the only public institution offering a nursing edu

cation in the State of Maryland (R. 17-18). Two courses of

study are open to students admitted to the School. One is a

three year course leading to a certificate. The other re

quires the prior successful completion of two years of

college and leads to a B. S. degree. Three years study is re

quired in each course (R. 8).

The educational and moral qualifications of Respondent

are equal to, if not superior to, the educational and moral

qualifications of at least some of the white students who

were admitted to the first year class at Maryland for the

academic year beginning August 8, 1949, and whose appli

cations were received by the proper authorities of the

University of Maryland after the receipt of Respondent’s

application. Respondent was ready, able and willing to

pay all fees and expenses for her first year course of study

and to conform to all lawful rules and regulations gov

erning first year students at Maryland (R. 17-18). Respon

dent filed the Petition for Mandamus in this case on July

27, 1949.

On August 13, 1949, Dr. Edgar F. Long, Director of Ad

missions of the University of Maryland (one of the Peti

tioners), wrote to Respondent concerning her application

(R. 10-11). In this letter, Respondent was advised of the

policy of the State of Maryland that members of the white

and Negro races should be segregated in public educa

tional institutions. She also was advised that, in further

13

ance of said policy, the Governor of the State of Mary

land had entered into a Compact dated February 8, 1948,

known as “The Regional Compact”, with the Governors of

the States of Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Alabama, Missis

sippi, Tennessee, Arkansas, North Carolina, South Caro

lina, Texas, Oklahoma, West Virginia and the Common

wealth of Virginia; that the General Assembly of Mary

land, by Chapter 282 of the Laws of 1949, approved, con

firmed and ratified said Compact, the Act of approval be

ing effective June 1, 1949; that said Compact had been ap

proved by proper legislative action by more than six of the

aforesaid States and was in full force and effect; that The

Regional Compact makes provision for education in the

professional, technological, scientific, literary and other

fields of all citizens of the several signatory States, regard

less of race or creed, at regional educational institutions in

the Southern States; that arrangements had been made

whereby the Meharry Medical College, Nashville, Tennes

see, had become a Compact Institution to which the signa

tory States will send students for medical, dental and

nursing education. Respondent was further advised that

arrangements would be made so that she could attend the

School of Nursing at Meharry Medical College (herein re

ferred to as “Meharry” ) ; that her total expenses incident to

attending Meharry, including necessary travel and room

and board, would not exceed what it would cost her to at

tend Maryland; that she would receive the same kind and

quality of work at Meharry as she would receive at Mary

land. Respondent was advised to contact Dr. Long either

at College Park or at Baltimore so that he could advise her

the procedure to be employed for her admission to Meharry;

that it was necessary that her application be certified to

Meharry by the Director of Admissions of the University

of Maryland.

14

It was stipulated by Respondent’s counsel that the total

overall cost to her, including living and traveling expenses,

incident to her attendance at Meharry would not exceed

what it would cost her to attend Maryland (R. 18). It was

further stipulated that as of October 10, 1949, the date on

which this case was tried below, The Regional Compact

had been ratified and approved by the Legislatures of all

the signatory States with the exception of Texas, Virginia

and West Virginia and that the Compact was in full force

and effect; also that each of the signatory States has segre

gated schools (R. 18).

It was stipulated that Respondent’s application for ad

mission to Maryland was not accepted solely because of

the fact that she is a member of the Negro race (R. 17).

There was offered in evidence the Contract for Training

in Nursing Education, dated July 19, 1949, between the

Board of Control for Southern Regional Education and the

University of Maryland (R. 14-17). Under this contract,

the Board covenants and agrees, among other things, to pro

vide the State of Maryland with a quota of three places

in Meharry Medical College, School of Nursing, Nashville,

Tennessee, for first year students to be selected from ap

plicants certified by the State of Maryland, that said quota

should continue through each succeeding college class until

it applies to all years of instruction desired by the State of

Maryland (R. 15). The State of Maryland, among other

things, agrees to make certain payments to the Board for

each student accepted under the Contract (R. 16). The

term of the contract is for two calendar years from July 1,

1949, automatically renewable for an additional term of

two years and so on unless either party gives the other

party notice, in writing, of its intention to terminate the

Contract at least two calendar years prior to the date of

termination (R. 16).

15

At the trial of this case, Petitioners offered evidence,

which was not disputed or contradicted in any way what

soever by Respondent, showing clearly that the educational

facilities for nursing education afforded at Meharry were

at least substantially equal to, if not in fact somewhat

superior to, the facilities offered at Maryland. Dr. Maurice

C. Pincoffs, who for a period of sixteen months prior to the

trial of this case had been in policy charge of the School

of Nursing of the University of Maryland, testified in detail

regarding the comparison of the facilities of the two Schools

(R. 39-46). His conclusion, based upon a comparison of

available funds, character of the student body, character

of the faculty, physical facilities (class rooms, laboratories,

equipment), curriculum and living conditions, was that

“if the objective of the candidate is education in nursing,

Meharry Medical College offers at least equivalent, and in

my opinion, somewhat better organized instruction in nurs

ing” (R. 46).

Petitioners also produced the testimony of Mrs. Verne

Allen Nesbitt, a graduate of Vanderbilt University and

the University of Nashville, Tennessee, and a registered

nurse. She is a white woman, well educated, whose hus

band is a medical doctor presently associated writh the

Johns Hopkins Hospital. At the time of the trial, Mrs.

Nesbitt was instructor in obstetrics in the School of Nurs

ing at Sinai Hospital, Baltimore, Maryland. Mrs. Nesbitt

taught at Meharry, for one term in the year 1947 (R. 52-53).

She testified that “Meharry students are a higher caliber

student than you would see in a hospital school of nursing

for the reason that they are better prepared, and are young

people who are seeking a higher course in nursing than the

three year course” (R. 53-54); that the physical facilities

offered at Meharry (the nurses’ home and the hospital

16

facilities) compared favorably with the facilities at Vander

bilt or Sinai (R. 54-55). She further testified that she was

much impressed with the library of the School, which was

shared with medical and dental students; also with the op

portunity for social life afforded the students (R. 55).

Petitioners further produced testimony showing that

Meharry was accredited by the National League of Nurs

ing Education, which, in itself, shows that it is a first class

nursing institution (R. 58). Although accreditation by the

League is conditioned upon application by the School of

Nursing seeking a rating, Maryland had not, up to the time

of trial, sought such accreditation for the reason that its

officials did not believe that it could meet the rigid standards

of the League (R. 58, 61).

In taking Tennessee State Board of Nursing examina

tions, graduates of Meharry compared most favorably with

graduates of other schools. Out of seven or eight subjects,

Meharry graduates’ average examination grades were

higher than the average examination grades of graduates

of approximately fourteen other schools of nursing in

Tennessee (R. 45). On the other hand, the record of

graduates of Maryland on examinations conducted by the

Maryland State Board of Examiners of Nurses’ does not

compare too favorably with the record of the graduates of

other schools of nursing (R. 64-66).

Up to the time of trial, only one graduate of Meharry had

applied for registration in the State of Maryland. She is

Mrs. Miriam Austin Wilkens, at present Assistant Director

of the School of Nursing at Provident Hospital, Baltimore,

Maryland. She was registered by the Maryland Board on

the basis of her Tennessee registration (R. 57-58).

17

ERRORS BELOW RELIED ON HERE

Petitioners rely on the following point:

The Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States does not prevent the State of Maryland from

effecting segregation of the white and Negro races for the

purpose of education, provided the facilities offered are

substantially equal; that the offer by the University of

Maryland under The Regional Compact to provide nursing

education for Respondent at Meharry Medical College,

School of Nursing, Nashville, Tennessee, would afford equal

facilities for the education of Respondent; that, therefore,

there has been no abridgement of the Respondent’s consti

tutional guarantee of equal protection of the laws. This

point was decided by the Baltimore City Court in favor of

the Petitioners and was decided by the Court of Appeals

of Maryland erroneously in favor of the Respondent.

ARGUMENT

DID THE OFFER TO PROVIDE NURSING EDUCATION FOR MISS

McCREADY AT MEHARRY MEDICAL COLLEGE, NASHVILLE,

TENNESSEE, UNDER THE REGIONAL COMPACT, AFFORD TO HER

THE EQUAL PROTECTION OF THE LAWS GUARANTEED BY THE

FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT TO THE CONSTITUTION OF THE

UNITED STATES?

Under the particular facts presented by this case, the

only question presented is as follows: Did the State of Mary

land, by virtue of the fact that it is a party to The Regional

Compact, discharge its duties and obligations to Respondent

under the Constitution of the United States when it ar

ranged for her nursing education at Meharry Medical Col

lege, School of Nursing, Nashville, Tennessee? This issue

is partly a question of fact and partly a question of law;

viz: (a) Are the facilities for nursing education offered by

Meharry substantially equal to the facilities offered at

18

Maryland? (b) Is provision for the education of a Maryland

citizen at a Compact institution legal segregation of the

races for educational purposes within the purview of the

Constitution of the United States and the decisions of this

Court?

1.

The policy of segregation of the two races for educational

purposes is generally accepted throughout the States which

are parties to The Regional Compact and has been ap

proved by this Court in the case of Plessy v. Ferguson, 163

U. S. 537, 41 L. Ed. 256. This approval of segregation was

again recognized in the case of Missouri, ex rel. Gaines v.

Canada, 305 U. S. 337, 344, 83 L. Ed. 208, 211. Finally, by

the very recent decisions of this Court in the cases of

Sweatt v. Painter, et al., No. 44, October Term, 1949, and

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, No. 34, October

Term, 1949, this Court refused to reexamine the “separate

but equal” doctrine enunciated in Plessy v. Ferguson, supra,

although requested to do so by the Solicitor General of

the United States.

2.

The Regional Compact (Laws of 1949, Ch. 282), which

was approved by the State of Maryland, effective June 1,

1949, was executed by the signatory States for the purpose

of the development and maintenance of education of the

citizens of such States on a regional basis. It is intended

to afford greater educational opportunities for such citizens

than could be provided by the several States separately.

It applies to all citizens of the States by its express pro

visions. The operations under the Compact, up to this

point, have, in fact, benefited all citizens regardless of

race or creed. For example, the State of Maryland, under

19

The Regional Compact, has sent several white students of

veterinary medicine to the University of Georgia and two

Negro students of medicine to Meharry.

In his remarks before the 1949 Conference of the National

Association of Attorneys General, (Conference Proceedings,

1949, p. 69) Solicitor General William F, Barry, of Tennes

see, made the following remarks on this point:

“Under these arrangements 207 white students and

180 Negro students will receive training in 1949-50.

These services are being paid for by a budget of approx

imately one and one-half million dollars. The Central

Control Office operations (located in Atlanta) carry

an annual budget of approximately $85,000.

“The program officially began in September, 1948.

In less than a year, therefore, regional planning in

graduate and professional education grew from a pro

posal to a program. The Board of Control has begun

to serve as an agency through which the states and in

stitutions of the compact area can broaden the base

of planning and support so that the opportunities for

training leadership in the South can match or exceed

opportunities anywhere in the nation.”

The Regional Compact is not, either expressly or by

necessary implication, aimed at segregation of the races.

However, it is available as a means of effecting such segre

gation when such means are not available within the con

fines of the several States. The Compact, as of the present

time, has been ratified by appropriate legislative action

of the signatory States, with the exception of Texas, Vir

ginia and West Virginia.

3.

The Regional Compact is the type of agreement which,

under Article I, Section 10, Clause 3 of the Constitution of

the United States, does not require approval by Congress

before it can become effective. When the Federal Aid to

20

Education Bill was being debated in the Senate, Senator

Morse of Oregon, in his remarks concerning a proposed

amendment to said Bill, discussed the fact that he had

opposed ratification of The Regional Compact by the

Senate. His remarks set forth in the Congressional Record,

Vol. 95, No. 77, page 5588, Tuesday, May 3, 1949, show the

following reasons for his opposition:

“First, is this the type of compact which the Con

stitution requires the Congress to ratify? I shall not

repeat my argument of last year at any length, other

than to point out that I am satisfied now, as I was then,

that the interstate compact offered by the 16 Southern

States was not the type of interstate compact that the

Congress of the United States, under the Constitution,

is required—and I underline the word ‘required’—to

ratify.

“So when the interstate compact was before us we

had to decide this question, ‘Is this the type of compact

which requires ratification by the Congress of the

United States?’ Of course the answer to that question

was clearly no; and the answer was ‘no’ because of

the second question which we must consider in such

a situation. The second question is: What Federal

jurisdiction is in any way encroached upon by the

proposed contract? It will be recalled that during the

course of the debate not a single southern Senator

could point out a single Federal power which was

encroached upon by the proposed compact. Until they

could show wherein that southern compact in some

way transgressed a delegated Federal power under

the Constitution of the United States, they were clearly

out of court, so to speak, so far as the Congress was

concerned. They failed to advance any sound argu

ment showing that as a matter of constitutional duty

under the interstate compact clause we would have to

approve the compact before it could be put into effect

by the States.”

21

That this Compact is not the type which requires Con

gressional approval is further supported by the case of

Virginia v. Tennessee, 148 U. S. 502, 517-519, 37 L. Ed.

537, 542-543. The applicable rule is stated by the Supreme

Court to be as follows:

“The Constitution provides that ‘no state shall, with

out the consent of Congress, lay any duty of tonnage,

keep troops or ships of war in time of peace, enter into

any agreement or compact with another state, or with

a foreign power, or engage in war, unless actually

invaded, or in such immediate danger as will not ad

mit of delay’.

“Is the agreement made without the consent of Con

gress, between Virginia and Tennessee, to appoint

commissioners to run and mark the boundary line

between them, within the prohibition of this clause?

The terms ‘agreement’ or ‘compact’ taken by them

selves are sufficiently comprehensive to embrace all

forms of stipulation, written or verbal, and relating

to all kinds of subjects; to those to which the United

States can have no possible objection or have any

interest in interfering with, as well as to those which

may tend to increase and build up the political influ

ence of the contracting states, so as to encroach upon

or impair the supremacy of the United States or inter

fere with their rightful management of particular

subjects placed under their entire control.

“There are many matters upon which different states

may agree that can in no respect concern the United

States. If, for instance, Virginia should come into

possession and ownership of a small parcel of land in

New York ivhich the latter state might desire to ac

quire as a site for a public building, it would hardly

be deemed essential for the latter state to obtain the

consent of Congress before it could make a valid agree

ment with Virginia for the purchase of the land. If

Massachusetts, in forwarding its exhibits to the World’s

Fair at Chicago, should desire to transport them a

part of the distance over the Erie Canal, it would

22

hardly be deemed essential for that state to obtain

the consent of Congress before it could contract with

New York for the transportation of the exhibit through

that State in that way. If the bordering line of two

states should cross some malarious and disease pro

ducing district, there could be no possible reason, on

any conceivable public grounds, to obtain the consent

of Congress for the bordering states to agree to unite

in draining the district, and thus remove the cause of

disease. So in the case of threatened invasion of

cholera, plague, or other causes of sickness and death,

it would be the height of absurdity to hold that the

threatened states could not unite in providing means

to prevent and repel the invasion of the pestilence

without obtaining the consent of Congress, which might

not be at the time in session. If, then, the terms ‘com

pact’ or ‘agreement’ in the Constitution do not apply

to every possible compact or agreement between one

state and another, for the validity of which the con

sent of Congress must be obtained, to what compacts

or agreements does the Constitution apply?

“Looking at the clause in which the terms ‘compact’

or ‘agreement’ appear, it is evident that the prohibition

is directed to the formation of any combination tend

ing to the increase of political power in the states,

which may encroach upon or interfere with the just

supremacy of the United States. Story, in his Com

mentaries (§1403) referring to a previous part of the

same section of the Constitution in which the clause in

question appears, observes that its language ‘may be

more plausibly interpreted from the terms used,

“ treaty, alliance, or confederation,” and upon the

ground that the sense of each is best known by its

association (noscitur a sociis) to apply to treaties of

a political character; such as treaties of alliance for

purposes of peace and war; and treaties of confedera

tion, in which the parties are leagued for mutual

government, political co-operation, and the exercise

of political sovereignty, and treaties of cession of

23

sovereignty, or conferring internal political jurisdic

tion, or external political dependence, or general com

mercial privileges’ ; and that ‘the latter clause, “com

pacts and agreements,” might then very properly ap

ply to such as regarded what might be deemed mere

private rights of sovereignty; such as questions of

boundary; interests in land situate in the territory

of each other; and other internal regulations for the

mutual comfort and convenience of states bordering

on each other.’ And he adds: ‘In such cases the con

sent of Congress may be properly required, in order

to check any infringement of the rights of the national

government; and, at the same time, a total prohibition

to enter into any compact or agreement might be at

tended with permanent inconvenience or public mis

chief.’ ” (Italics supplied).

See also:

Wharton v. Wise, 153 U. S. 155, 171-173; 38 L. Ed.

669, 676.

It is obvious that The Regional Compact in no way tends

“to increase and build up the political influence of the con

tracting State, so as to encroach upon or impair the su

premacy of the United States or interfere with their

rightful management of particular subjects placed under

their entire control” .

Certainly, interstate problems concerned with health

(e.g., infectious or contagious diseases, whether of humans

or of animals), institutional care (e.g., women’s prisons,

mental hospitals, homes for aged) conservation of natural

resources (e.g., oyster and fish conservation problems of

Maryland and Virginia) and motor vehicles (e.g,. recogni

tion of license tags of a foreign State) can be and have

been handled by Compacts between the States without the

requirement that they receive the approval of the Con

gress of the United States.

24

The Report of the Interstate Compact Committee of the

Pennsylvania Bar Association in June, 1950, states as

follows:

“There is now under consideration in eleven western

States a proposal to establish a regional institution

for care of mentally deficient juvenile delinquents.

There has been recommended also creation of regional

schools for the deaf and blind on a four-state basis

(Utah, Idaho, Wyoming and Nevada). It is not known

at the present time whether the States sponsoring

these institutional facilities intend to request the con

sent of the Congress to such plans.

“On the basis of precedents indicating that it is con

sidered unnecessary to secure approval of the Congress

with respect to agreements between States when those

agreements do not tend to increase political power of

the States or encroach on Federal supremacy under

the United States Constitution, States are beginning to

utilize the compact method for providing services as

to which the Federal government has not heretofore

asserted authority. Until recently the best known in

stances have been the arrangements between Virginia

and West Virginia for the use of an educational insti

tution in Richmond and between Vermont and New

Hampshire for a joint state penitentiary to serve both

States.”

It is submitted that this is equally true of interstate com

pacts which are concerned with higher education for citi

zens of the several States.

4.

The Regional Compact is binding upon each of the signa

tory States and upon all of the citizens of such States.

Virginia v. Tennessee, (L. Ed. p. 545), supra; Poole v.

Fleeger, 11 Pet. 185, 9 Ed. 680, 690; Hinderlider v. La Plata

River & Cherry Creek Ditch Company, 304 U. S. 92, 106,

25

82 L. Ed. 1202, 1210. In the last case cited, the Supreme

Court of the United States, in discussing the effect of inter

state compacts upon the citizens of the signatory States,

said as follows:

“Whether the apportionment of the water of an in

terstate stream be made by compact between the upper

and lower States with the consent of Congress or by

a decree of this Court, the apportionment is binding

upon the citizens of each State and all water claimants,

even where the State had granted the water rights

before it entered into the compact. That the private

rights of grantees of a State are determined by the

adjustment by compact of a disputed boundary was

settled a century ago in Poole v. Fleeger, 11 Pet. 185,

209, 9 L. ed. 680, 690, where the Court said:

‘It cannot be doubted, that it is a part of the general

right of sovereignty, belonging to independent nations,

to establish and fix the disputed boundaries between

their respective territories; and the boundaries so

established and fixed by compact between nations,

become conclusive upon all the subjects and citizens

thereof, and bind their rights; and are to be treated,

to all intents and purposes, as the true and real bound

aries. This is a doctrine universally recognized in the

law and practice of nations. It is a right equally be

longing to the states of this Union; unless it has been

surrendered under the Constitution of the United

States. So far from there being any pretense of such a

general surrender of the right, that it is expressly

recognized by the Constitution and guarded in its ex

ercise by a single limitation or restriction, requiring

the consent of Congress.’ ”

5.

The Regional Compact does not deprive the Respondent

of any rights guaranteed to her by the Constitution of the

United States.

26

Considering this point, it must be borne in mind that

up to this time none of the decisions of this Court have

dealt with the exact problem here under consideration.

In the case of Missouri, ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, supra,

the Petitioner was an applicant for admission to the Law

School. This was likewise true in the case of Sipuel v.

Oklahoma, 332 U. S. 631, 92 L. Ed. 247 (333 U. S. 147, 92 L.

Ed. 605). In the Gaines case supra, (L. ed. p. 213) in con

tending that the Writ should be issued, the Petitioners

relied particularly upon the special advantages incident

to attending a Law School in the State of which one is a

citizen and in which one intends to practice. The opinion

in the Sipuel case was per curiam and makes no reference

whatsoever to Petitioner’s contentions therein, the decision

being based upon the rule laid down in the Gaines case.

Petitioners admit that there are certain advantages incident

to attending a local Law School over attendance at one

outside of the State where one proposes to practice. In

a local school, the emphasis is upon local rules of practice

and procedure and substantive law peculiar to that State.

There is also the opportunity of observing the local courts

in action. However, no such advantages accrue to a student

of nursing. There are no rules regarding nursing which are

peculiar to any given State nor is there any practice in the

nursing profession peculiar to any given State.

An additional factor in the present case is that the

operations under The Regional Compact are such that the

cost to Respondent at Meharry will be no greater than

her expenses would be if she attended Maryland. That this

is true is conceded by Respondent (R. 18).

Under The Regional Compact, contracts have been en

tered into between various States, which wish to send

students out of their own boundaries for educational pur-

27

poses, with the Regional Board and by the Board with

Colleges and Universities in the various States, It is sub

mitted that, so far as citizens of Maryland are concerned,

the effect of these contracts executed under The Regional

Compact is identically the same as if the educational facil

ities were furnished within the State of Maryland. For

example, if the Maryland State College, at Princess Anne,

(a division of the University of Maryland) afforded facil

ities for nursing education substantially equal to such

facilities provided by the University of Maryland, in Balti

more, Appellees could provide such education for Respond

ent at the former institution. No question could be raised ' N o

under such circumstances that Respondent’s constitutional

rights had been violated. If, in lieu of having facilities for

nursing education of Negroes at Princess Anne, Somerset

County, the University of Maryland owned a tract of land

over the State line in Accomac County, Virginia, and there

established facilities for nursing education of Negroes sub

stantially equal to such facilities at the University of Mary

land, the same rule would unquestionably apply. Under

such circumstances, equal educational opportunities would

be afforded to Negro students by the University of Mary

land at a division of the University of Maryland. It is in

conceivable that the mere fact that the physical facilities

were located just outside the boundaries of the State of

Maryland would affect the rule. Instead of adopting what

would prove to be a most expensive and burdensome pro

cedure, viz. outright purchase of educational facilities so

that they would be an integral part of the University of

Maryland, the State has adopted the alternative procedure

of contracting for education of Maryland citizens in institu

tions located outside of the State. Maryland citizens are

protected by the provisions of The Regional Compact and

of the various contracts executed thereunder. There cer-

28

tainly is no substantial difference between such a con

tractual arrangement for, and actual ownership of, the

educational facilities. By this method, the State of Mary

land can maintain its policy of segregation, and, at the

same time, provide educational opportunities for Negroes

which are equal to those afforded to members of the white

race at no additional cost whatsoever to the members of

the Negro race.

That the facilities for nursing education offered at Me-

harry are substantially equal to those offered at Maryland

is obvious, and in fact uncontradicted, in the present

case so that in that respect this case meets the require

ments of all the decisions on this subject. It is clear from

a consideration of the careful analysis by Dr. Pincoffs

of the two Schools, the testimony of Mrs. Nesbitt and

the other evidence offered by Petitioners that a student

at Meharry receives an education in nursing certainly equal

to that afforded at Maryland. In fact, the conclusion that

Meharry, considering all factors, offers better educational

facilities can reasonably be drawn from the evidence.

6.

The Regional Compact has introduced a new decisive

factor into the law. The new factor is that the States

which have ratified the Compact have, for educational

purposes, eliminated State lines. It is an attempt through

voluntary agreement and cooperation to provide citizens

of all the signatory States with unlimited educational

opportunities. The opportunities proposed by The Regional

Compact have been assured by the execution of contracts

thereunder. The operations under The Regional Compact

are distinctly different from those under the out-of-State

scholarship plans in vogue in a number of States prior

to the decision in the Gaines case, supra. The scholarship

29

plans provided only for tuition. The fact that the student

would incur additional expense, such as travel, was not

taken into consideration. This, of course, resulted in

inequality. This is no longer true under The Regional

Compact plan.

7.

The Court’s attention is directed to the fact that a few

of the Western-Rocky Mountain States are presently oper

ating under informal agreements which involve incarcera

tion of female prisoners and treatment of mental patients

and the aged and indigent. In addition to this, those States

are presently drafting a Regional Compact covering medi

cal and dental education similar to that involved in this

case. From the foregoing, it will appear that there is a

trend toward interstate cooperation in problems of this

kind. This, of course, is dictated by a desire to provide

adequate and proper care, treatment and education for the s’ Q

citizens of the several States in a single location. Such a

solution is socially and economically sound. Most as

suredly, it does not in any way deprive the citizens of

the several States of the equal protection of the laws.

CONCLUSION

It is respectfully submitted that the Gaines, Sipuel and

Murray cases, supra, are not in point and are not con

trolling in this case; that The Regional Compact is valid

and binding upon the signatory States and the citizens of

such States; that the administration under the Compact,

so far as Respondent is concerned, does not in any way

abridge any of her constitutional rights; that Respondent

is afforded facilities for nursing education which are cer

tainly equal to and possibly better than she could obtain

at the University of Maryland; that, therefore, the judg-

30

ment of the Court of Appeals of Maryland should be re

versed.

Respectfully submitted,

Hall Ham m ond ,

Attorney General of Maryland,

Attorney for Petitioners,

1901 Mathieson Building,

Baltimore 2, Maryland.

K enneth C. Proctor,

Assistant Attorney General of Maryland,

Of Counsel,

1901 Mathieson Building,

Baltimore 2, Maryland.

31

APPENDIX TO BRIEF

LAWS OF 1949

CHAPTER 282

(Senate Bill 432)

A n A ct to approve, confirm and ratify a certain Compact

entered into by the State of Maryland and other Southern

States by and through their respective Governors on Feb

ruary 8, 1948, as amended, relating to the development and

maintenance of regional educational services and schools in

the Southern States in the professional, technological,

scientific, literary and other fields, so as to provide greater

educational advantages and facilities for the citizens in the

several States here recited in such region, and to declare

that the State of Maryland is a party to said Compact, as

amended, and that the agreements, covenants and obliga

tions therein are binding upon said State.

W hereas, on the 8th day of February, in the Year of Our

Lord One Thousand Nine Hundred and Forty-eight, the

State of Maryland, and the States of Florida, Georgia,

Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee, Arkansas, Vir

ginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Texas, Oklahoma

and West Virginia through and by their respective Gov

ernors, entered into a written Compact relative to the

development and maintenance of regional educational

services and schools in the Southern States in the profes

sional, technological, scientific, literary, and other fields, so

as to provide greater educational advantages and facilities

for the citizens of the several States who reside within

such region; and

W hereas, the said Compact has been amended in certain

respects, a copy of which Compact as amended is as follows:

THE REGIONAL COMPACT

(As Amended)

W hereas, The States who are parties hereto have during

the past several years conducted careful investigation look-

32

ing toward the establishment and maintenance of jointly

owned and operated regional educational institutions in

the Southern States in the professional, technological,

scientific, literary and other fields, so as to provide greater

educational advantages and facilities for the citizens of

the several States who reside within such region; and

W hereas, Meharry Medical College of Nashville, Ten

nessee, has proposed that its lands, buildings, equipment,

and the net income from its endowment be turned over to

the Southern States, or to an agency acting in their behalf,

to be operated as a regional institution for medical, dental

and nursing education upon terms and conditions to be

hereafter agreed upon between the Southern States and

Meharry Medical College, which proposal, because of the

present financial condition of the institution, has been ap

proved by the said States who are parties hereto; and

W hereas, The said States desire to enter into a compact

with each other providing for the planning and establish

ment of regional educational facilities;

Now, Therefore, in consideration of the mutual agree

ments, covenants and obligations assumed by the respective

States who are parties hereto (hereinafter referred to as

“States” ), the said several States do hereby form a geo

graphical district or region consisting of the areas lying

within the boundaries of the contracting States which, for

the purposes of this compact, shall constitute an area for

regional education supported by public funds derived from

taxation by the constituent States and derived from other

sources for the establishment, acquisition, operation and

maintenance of regional educational schools and institu

tions for the benefit of citizens of the respective States re

siding within the region so established as may be deter

mined from time to time in accordance with the terms and

provisions of this compact.

The States do further hereby establish and create a joint

agency which shall be known as the Board of Control for

Southern Regional Education (hereinafter referred to as

the “Board” ), the members of which Board shall consist

33

of the Governor of each State, ex officio, and three addi

tional citizens of each State to be appointed by the Gov

ernor thereof, at least one of whom shall be selected from

the field of education. The Governor shall continue as a

member of the Board during his tenure of office as Gov

ernor of the State, but the members of the Board appointed

by the Governor shall hold office for a period of four years

except that in the original appointments one Board member

so appointed by the Governor shall be designated at the

time of his appointment to serve an initial term of two

years, one Board member to serve an initial term of three

years, and the remaining Board member to serve the full

term of four years, but thereafter the successor of each

appointed Board member shall serve the full term of four

years. Vacancies on the Board caused by death, resigna

tion, refusal or inability to serve, shall be filled by appoint

ment by the Governor for the unexpired portion of the

term. The officers of the Board shall be a Chairman, a

Vice-Chairman, a Secretary, a Treasurer, and such addi

tional officers as may be created by the Board from time

to time. The Board shall meet annually and officers shall

be elected to hold office until the next annual meeting.

The Board shall have the right to formulate and establish

by-laws not inconsistent with the provisions of this com

pact to govern its own actions in the performance of the

duties delegated to it including the right to create and ap

point an Executive Committee and a Finance Committee

with such powers and authority as the Board may delegate

to them from time to time. The Board may, within its

discretion, elect as its Chairman a person who is not a

member of the Board, provided such person resides within

a signatory State, and upon such election such person shall

become a member of the Board with all the rights and

privileges of such membership.

It shall be the duty of the Board to submit plans and

recommendations to the States from time to time for

their approval and adoption by appropriate legislative ac

tion for the development, establishment, acquisition, opera

tion and maintenance of educational schools and institu-

34

tions within the geographical limits of the regional area

of the States, of such character and type and for such

educational purposes, professional, technological, scientific,

literary, or otherwise, as they may deem and determine to

be proper, necessary or advisable. Title to all such educa

tional institutions when so established by appropriate legis

lative actions of the States and to all properties and facili

ties used in connection therewith shall be vested in said

Board as the agency of and for the use and benefit of the

said States and the citizens thereof, and all such educa

tional institutions shall be operated, maintained and

financed in the manner herein set out, subject to any pro

visions or limitations which may be contained in the legis

lative acts of the States authorizing the creation, establish

ment and operation of such educational institutions.

In addition to the power and authority heretofore grant

ed, the Board shall have the power to enter into such

agreements or arrangements with any of the States and

with educational institutions or agencies, as may be re

quired in the judgment of the Board, to provide adequate

services and facilities for the graduate, professional, and

technical education for the benefit of the citizens of the

respective States residing within the region, and such

additional and general power and authority as may be

vested in the Board from time to time by legislative enact

ment of the said States.

Any two or more States who are parties of this compact

shall have the right to enter into supplemental agreements

providing for the establishment, financing and operation

of regional educational institutions for the benefit of citi

zens residing within an area which constitutes a portion of

the general region herein created, such institutions to be

financed exclusively by such States and to be controlled

exclusively by the members of the Board representing such

States provided such agreement is submitted to and ap

proved by the Board prior to the establishment of such

institutions.

35

Each State agrees that, when authorized by the Legis

lature, it will from time to time make available and pay

over to said Board such funds as may be required for the

establishment, acquisition, operation and maintenance of

such regional educational institutions as may be authorized

by the States under the terms of this compact, the contri

bution of each State at all times to be in the proportion that

its population bears to the total combined population of the

States who are parties hereto as shown from time to time

by the most recent official published report of the Bureau

of the Census of the United States of America; or upon

such other basis as may be agreed upon.

This compact shall not take effect or be binding upon

any State unless and until it shall be approved by proper

legislative action of as many as six or more of the States

whose Governors have subscribed hereto within a period

of eighteen months from the date hereof. When and if six

or more States shall have given legislative approval to

this compact within said eighteen months period, it shall

be and become binding upon such six or more States 60

days after the date of legislative approval by the Sixth

State and the Governors of such six or more States shall

forthwith name the members of the Board from their

States as hereinabove set out, and the Board shall then

meet on call of the Governor of any State approving this

compact, at which time the Board shall elect officers, adopt

by-laws, appoint committees and otherwise fully organize.

Other States whose names are subscribed hereto shall

thereafter become parties hereto upon approval of this

compact by legislative action within two years from the

date hereof, upon such conditions as may be agreed upon

at the time. Provided, however, that with respect to any

State whose constitution may require amendment in order

to permit legislative approval of the Compact, such State

or States shall become parties hereto upon approval of this

Compact by legislative action within seven years from the

date hereof, upon such conditions as may be agreed upon

at the time.

36

After becoming effective this compact shall thereafter

continue without limitation of time; provided, however,

that it may be terminated at any time by unanimous action

of the States and provided further that any State may

withdraw from this compact if such withdrawal is ap

proved by its Legislature, such withdrawal to become ef

fective two years after written notice thereof to the Board

accompanied by a certified copy of the requisite legislative

action, but such withdrawal shall not relieve the withdraw

ing State from its obligations hereunder accruing up to

the effective date of such withdrawal. Any State so with

drawing shall ipso facto cease to have any claim to or

ownership of any of the property held or vested in the

Board or to any of the funds of the Board held under the

terms of this compact.

If any State shall at any time become in default in the

performance of any of its obligations assumed herein or

with respect to any obligation imposed upon said State

as authorized by and in compliance with the terms and pro

visions of this compact, all rights, privileges and benefits

of such defaulting State, its members on the Board and its

citizens shall ipso facto be and become suspended from

and after the date of such default. Unless such default

shall be remedied and made good within a period of one

year immediately following the date of such default this

compact may be terminated with respect to such default

ing State by an affirmative vote of three-fourths of the

members of the Board (exclusive of the members repre

senting the State in default), from and after which time

such State shall cease to be a party to this compact and

shall have no further claim to or ownership of any of the

property held by or vested in the Board or to any of the

funds of the Board held under the terms of this compact, but

such termination sha.ll in no manner release such default

ing State from any accrued obligation or otherwise affect

this compact or the rights, duties, privileges or obligations

of the remaining States thereunder.

In W itness W hereof this Compact has been approved

and signed by Governors of the several States, subject to

37

the approval of their respective Legislatures in the manner

hereinabove set out, as of the 8th day of February, 1948.

STATE OF FLORIDA

By M illard F. Caldwell

Governor

STATE OF MARYLAND

By W m . Preston Lane, Jr.

Governor

STATE OF GEORGIA

By M. E. Thompson

Governor

STATE OF LOUISIANA

By J. H. Davis

Governor

STATE OF ALABAMA

By James E. Folsom

Governor

STATE OF MISSISSIPPI

By F. L. W right

Governor

STATE OF TENNESSEE

By Jim M cCord

Governor

STATE OF ARKANSAS

By Ben L aney

Governor

COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA

By W m . M. Tuck

Governor

STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA

By R. Gregg Cherry

Governor

STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA

By J. Strom Thurmond

Governor

38

STATE OF TEXAS

By Beauford H. Jester

Governor

STATE OF OKLAHOMA

By Roy J. Turner

Governor

STATE OF WEST VIRGINIA

By Clarence W. M eadows

Governor

now, therefore,

Section 1. Be it enacted by the General Assembly of

Maryland, That the said Compact is hereby approved, con

firmed and ratified, and that as soon as the said Compact

shall be approved, confirmed and ratified by the Legisla

tures of at least six of the States signatory hereto in ac

cordance with the provisions of the Compact, thereupon

and immediately thereafter, every paragraph, clause, pro

vision, matter and thing in the said Compact contained

shall be obligatory on this State and the citizens thereof,

and shall be forever faithfully and inviolably observed and

kept by the government of this State and all of its citizens

according t9 the true intent and meaning and provisions

of the said Compact.

Sec. 2. And be it further enacted, That, upon the ap

proval of this Compact by the minimum requisite number

of States, as provided in said Compact, the Governor is

hereby authorized and directed to sign an engrossed copy

of the Compact and sufficient copies thereof, so as to pro

vide that each and every State approving the Compact

shall have an engrossed copy thereof.

Sec. 3. And be it further enacted, That this Act shall

take effect on June 1, 1949.

Approved April 22, 1949.