Chance v. Board of Examiners Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1972

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Chance v. Board of Examiners Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellees, 1972. 73d62631-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2f24b75b-8eb7-4219-bce5-3f0a25faa57e/chance-v-board-of-examiners-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

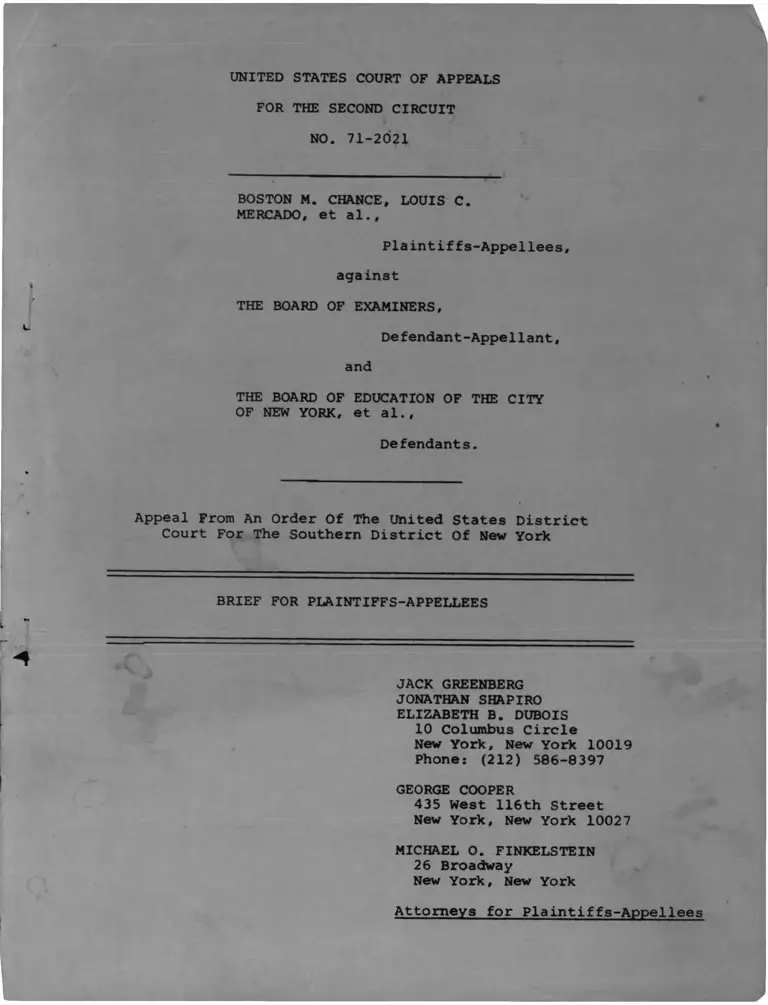

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

NO. 71-2021

BOSTON M. CHANCE, LOUIS C.

MERCADO, et al..

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

against

THE BOARD OF EXAMINERS,

Defendant-Appellant,

and

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY

OF NEW YORK, et al..

Defendants.

Appeal From An Order Of The United States District

Court For The Southern District Of New York

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES

JACK GREENBERG

JONATHAN SHAPIRO

ELIZABETH B. DUBOIS

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Phone: (212) 586-8397

GEORGE COOPER

435 West 116th Street

New York, New York 10027

MICHAEL O. FINKELSTEIN

26 Broadway

New York, New York

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellees

TABLE OF CONTENTS

*1

Statement of The Issues Presented for Review

Statement of The Case ................

(1) The Proceedings Below ..............

(2) The District Court's Decision .....

(3) The Preliminary Injunction .........

(4) Subsequent Developments ............

ARGUMENT:

PAGES

1

2

2

12

17

18

Introduction .......................

Point I. The District Court's Finding That

Defendants' Examination System Had A

Significant And Substantial Discrimi

natory Impact Was Clearly Supported By The Record ..........................

Point II. The Court Below Correctly Ruled That A

Public Employer Violates The Equal

Protection Clause In Conducting A Pro

motional Examination System Which

Systematically And Significantly Dis

criminates Against Ethnic Minority Groups

Where That Examination System Cannot Be

Shown To Have Any Relation To Job Performance ........

A. A Prima Facie case Of Discrimination Is

Made Out Where Examinations Significantly

And Systematically Exclude Members Of

An Ethnic Minority Group Regardless Of

Whether Any Subjective Intent To Discriminate is Shown ..........

B. Where Employment Tests Are Shown To Have

A Significant And Substantial Discrimi

natory impact On Ethnic Minority Groups

They Violate The Equal Protection Clause

If They Cannot Be Shown To Be Job-Rela-

(1) The Court Applied The Proper

Standard In Determining That An

Adequate Case Of Discriminatory Impact Had Been Made Out .......

i

PAGE

POINT III.

(2) The Court Properly Determined That

Examinations Which Have Such A Discrimi

natory Impact Violate The Equal Pro

tection Clause If They Cannot Be Shown

To Be Job-Related ................ a.4

The Court's Finding That Defendants'

Examinations Had Not Been Shown To Be

4 And Apparently Were Not Job-Related Was

Clearly Supported By The Record ............ 52

v POINT IV. The Grant Of Preliminary Relief, Based

Upon The Court's Findings With Regard

To irreparable Injury And The Likeli

hood Of Success On The Merits, Must Be

Upheld As A Proper Exercise Of Dis

cretion ..................... 50

Conclusion ...

Appendix A ...

Appendix B ...

4

1 1

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Page

Armstead v. Starkville Mun. Sep. School Dist.,

325 F. Supp. 560 (N.D. Miss. 1971)...... 23,37,44,49,57

^Arrington v. Massachusetts Bay Transportation

Authority, 306 F. Supp. 1355 (D. Mass.

1969) ....................................... 36,45,49, 57

Baker v. Columbus Municipal Separate School

District, 329 F. Supp. 706 (N.D. Miss. 1971) .. 37,44,45,

49,57

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954) ................ 47

Brown v. Allen, 344 U.S. 443 (1953) ................... 47

Carmichael v. Craven, No. 26,236, 9th Cir.,

Nov. 4, 1971 ....................................... 35

Carter v. Gallagher, 3 CCH E.P.D. 18205 (D. Minn.

1971), aff’d in pertinent part. 3 CCH E.P.D.

18335 (1971), aff'd in pertinent part en banc.

No. 71-1181 (8th Cir., Jan. 7, 1972) ...........36,39,41,

48,57,60

^Castro v. Beecher, 4 CCH E.P.D. 17569, clarified.

4 CCH E.P.D. 17570, -judgment modified. 4 CCH

E.P.D. 17589 (D. Mass. 1971) .................. 36,40,46

Chaney v. State Bar of California, 386 F.2d 962

(9th Cir. 1967) ................................... 44

Checker Motors Corp. v. Chrysler Corp., 405 F.2d 319

(2d Cir.), cert, denied. 394 U.S. 999 (1969) .... 59

Council of Supervisory Associations v. Board of

Education, 23 N.Y.2d 458, 297 N.Y.S.2d 547,

245 N.E. 2d 204 (1969) ................. ...... 22 62

Dandridge v. Williams, 397 U.S. 471 (1970) ............ 48

Dino de Laurentiis Cinematografica, S.P.A. v. D-150,

366 F . 2d 373 (2d Cir. 1966) .................. [___ 59

Gaston County v. United States, 395 U.S. 285 (1969)

iii

35

Goodwin v. Wyman, 330 F. Supp. 1038 (S.D. N.Y. 1971) .. 48

Page

Graham v. Richardson, 403 U.S. 365 (1971) ............. 47

Gregory v. Litton System, 316 F. Supp, 401 (Cent.

D. Cal. 1970) ...................................... 40

Briggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971),

reversing, 420 F.2d 1225 (4th Cir. 1970) 34,37,38,39,42,

47,48,49,57

Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections, 383 U.S.

663 (1966) ..................... ................... 47

Hawkins v. Town of Shaw, 437 F.2d 1286 (5th Cir. 1971) 35,48

Hicks v. Crown Zellerbach Corp., 319 F. Supp. 314

(E.D. La. 1970) ................................ 37,57,60

Hobson v. Hansen, 269 F. Supp. 401 (D. D.C. 1967),

aff'd sub nom. Smuck v. Hobson, 408 F.2d 175

(D.C. Cir. 1969) ............................... 35,42,48

Jackson v. Godwin, 400 F.2d 529 (5th Cir. 1968) ...... 35,48

Jackson v. Wheatley School District, 430 F.2d 1359

(8th Cir. 1970) .................................... 23

Johnson v. New York State Education Department,

449 F. 2d 871 (2d Cir. 1971) ...................... 48

Johnson v. Pike Corp., 4 CCH E.P.D. J7517 (Cent.

D. Cal. 1971) 37,40

Jones v. Georgia, 389 U.S. 24 (1967) .................. 41,47

Kennedy Park Homes Ass'n v. Lackawanna, 436 F.2d

108 (2d Cir. 1970) ................................ 35,47

Kirkpatrick v. Preisler, 394 U.S. 526 (1969) .......... 41

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944) ...... 47

Kramer v. Union Free School District, 395 U.S. 621

(1969) 46

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967) ................. 47

IV

Page

McLaughlin v. Florida, 369 U.S. 184 (1964) ............ 46,47

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587 (1935) ................ 46

North Carolina Board of Education v. Swann,

402 U.S. 43 (1971) ................................ 35

Packard Instrument Company v. Ans. Inc., 416 F.2d

943 (2d Cir. 1969) ................................ 59

Patton v. Mississippi, 332 U.S. 463 (1947) ............ 47

Penn v. Stumpf, 308 F. Supp. 1238 (N.D. Cal. 1970) ___ 36,39

Pickens v. Okalona Mun. Sep. Sch. Dist., No.

EC6956-K (N.D. Miss., Aug. 11, 1971) (mimeo.

OP-) ............................................... 46,49

^orcelli v. Titus, 431 F.2d 1254 (3d Cir. 1970),

aff1 g, 302 F. Supp. 726 (D. N.J. 1969) ........... 22,23

Powell v. Power, 436 F.2d 84 (2d Cir. 1970) ........... 35

Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791 (4th Cir.

1971) ........................................ 37,45,46, 50

Schware v. Board of Bar Examiners, 353 U.S. 232 (1957) 44

Shapiro v. Thompson, 394 U.S. 618 (1969) ............... 47

Sims v. Georgia, 389 U.S. 404 (1967) ................... 41

Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128 (1940) .................... 35

Societe Comptoir v. Alexander's Dept. Stores, 299 F.2d

33 (2d Cir. 1962) .................................. 59

Southern Alameda Spanish Speaking Org. v. Union City,

424 F . 2d 291 (9t.h Cir. 1970) ....................... 35

Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346 (1970) ................. 41

United States v. Bethlehem Steel, 446 F.2d 652

(2d Cir. 1971) ..................................... 46,50

United States v. Jacksonville Terminal Co., 3 CCH

E.P.D. f8324 (5th Cir. 1971) .................. 45, 50,57

v

United States v. W. T. Grant Co., 345 U.S. 629 (1953) . 59

United States ex rel. Chestnut v. Criminal Court of

City of New York, 442 F.2d 611 (2d Cir. 1971) ___ 41

Wells v. Rockefeller, 394 U.S. 542 (1969) ............. 41

W e s t e r n Addition Community Organization v. Alioto,

330 F. Supp. 536 (N.D. Cal. 1971) ........... .. 36,40,46

Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545 (1967) ................. 41

̂ Statutes and Regulations

California Fair Employment Practices. CCH E.P. Guide

120,861 ............................................ 43

Colorado Civil Rights Commission Policy Statement on

the Use of Psychological Tests. CCH E.P. Guide

121,060 ............................................ 43

EE0C Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures.

29 CFR §1607, 35 Fed. Reg. 12333 (Aug. 1, 1970) 43,57,60

N.Y. State CONST. Art. V §6 ............................ 44

N.Y. State Educ. Law §2569(1) (1967) .................. 44

' OFCC Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures.

35 Fed. Reg. 19307 (Oct. 2, 1971) ................ 43

V

Pennsylvania Guidelines on Employee Selection Proce-

dures, CCH E.P. Guide 15194 ....................... 43

42 U.S.C. §1981 ......................................... 2

42 U.S.C. §1983 ..................................... 2

42 U.S.C. §2000-e .................... „

Page

vi

Ot h e r A u t h o r 1 t i e s

ANASTASI, PRINCIPLES OF PSYCHOLOGICAL TESTING (3d

Ed. 1968) ......................................... 56, 57

Center for Field Research and School Services, New

York University, A Report of Recommendations in

the Recruitment. Selection, Appointment and

Promotion of Teachers in the New York City

Public Schools (1966) ............................ 24

COLEMAN, EQUALITY AND EDUCATIONAL OPPORTUNITY (1966) . 42

Cooper and Sobol, Seniority and Testing under Fair

Employment Laws. 82 HARV. L. REV. 1598 (1969) ... 42

CRONBACH, ESSENTIALS OF PSYCHOLOGICAL TESTING

(3d Ed. 1970)...................................... 54

Commission on Human Rights for the City of N. Y.,

Egual Employment Opportunity and the New York

City Public Schools, An Analysis and Recommenda

tions Based on Public Hearings Held January 25-29.

M ........................... .................. 25

CRESAP, McCORMICK and PAGET, Summary Report of

Assignments Conducted for the New York City

Board of Education (1962) ........................ 24

FISS, A Theory of Fair Employment Laws. 38 U. CHI.

L. REV. 235 (1971) ................................ 24

GHISELLI, THE VALIDITY OF OCCUPATIONAL APTITUDE

TESTS (1966) ...................................... 42

GRIFFITH REPORT, Teacher Mobility in New York City:

A Study of Recruitment. Selection, Appointment.

and Promotion of Teachers in the New York City

Public Schools (1963) ............................ 24

KIRKPATRICK, et al., TESTING AND FAIR EMPLOYMENT (1968) 42

Mayor's Advisory Panel on Decentralization of the

New York City Schools, Reconnection for

Learning (1967) [BUNDY REPORT]..................... 24

Mayor's Committee on Management Survey, Administra

tive Management of the School System of New York

City (1951) ["STRAYER AND YAVNER REPORT"J.... 24

Page

vii

Page

Note, Discriminatory Merit Systems; A Case Study of

the Supervisory Examinations Administered by the

New York Board of Examiners, 6 COLUM. J. L. &

SOCIAL PROBS. 374 (1970) ......................... 5,22

ROGERS, 110 LIVINGSTON STREET (1968) ................. 24

SCHINNERER, A Report to the New York City Education

Department (1961) 24

STAHL, Public Personnel Administration (5th ed. 1962) 56

THORNDIKE, PERSONNEL SELECTION (1949) 54,56

THORNDIKE and HAGEN, MEASUREMENT AND EVALUATION IN

PSYCHOLOGY AND EDUCATION (1969) ................. 56

viii

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

NO. 71-2021

BOSTON M. CHANCE, LOUIS C.

MERCADO, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

-against-

THE BOARD OF EXAMINERS,

Defendant-Appellant,

and

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE

CITY OF NEW YORK, et al..

Defendants.

Appeal From An Order Of The United States District

Court For The Southern District Of New York

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES

Statement of the Issues Presented for Review

1. Whether the district court's finding that the supervisory

examination system administered by defendants had a significant

and substantial discriminatory impact upon blacks and Puerto Ricans

must be upheld as not clearly erroneous?

2. Whether the district court was correct in ruling that

examinations which have such a discriminatory impact violate the

Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment if they

cannot be shown to be job-related?

3. Whether the district court's findings that the supervisory

examinations administered by defendants had not been shown to

be and apparently were not job-related must be upheld as not

clearly erroneous?

4. Whether the district court's grant of preliminary relief

must be upheld as not constituting an abuse of discretion in light

of its findings with respect to irreparable injury, the balance

of hardships and the probability of plaintiffs’ success on the

merits?

Statement of the Case

(1) The Proceedings Below

J JPlaintiffs brought this class action in September, 1970,

pursuant to 42 U.S.C. §§1981 and 1983, challenging the examinations

used to select principals and other supervisors in the City School

System. Plaintiffs charged that these examinations operated in

violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

in that they discriminated against blacks and Puerto Ricans and

could not be justified as job-related. Named as defendants were

the Chancellor, Dr. Harvey B. Scribner, the Board of Education

and the Board of Examiners. Plaintiffs moved simultaneously for

--/ The named plaintiffs included numerous blacks and Puerto Ricans

who had failed previous supervisory examinations, who possessed all

the educational and experience qualifications established for various

different supervisory positions they sought, but who could not receive

regular appointments because they lacked the requisite license

(App. 139a, 143-45a).

2

a preliminary injunction preventing defendants from administering

the Elementary School Principals' Examination scheduled for

November 3, 1970 and from giving other supervisory examinations

in the future until they had been validated.

Plaintiffs documented their claim of discrimination with

undisputed evidence that blacks and Puerto Ricans were grossly

underrepresented in the supervisory ranks and on supervisory lists

as compared to the student population (App. 147-49a). in addition,

comparative statistics were introduced from other city school

systems not subject to New York's unique examination procedures,

including Rochester's, where candidates must satisfy New York

State certification requirements. These showed New York City to

have by far the lowest percentage of black and Puerto Rican

supervisors, and the lowest ratio of minority group supervisors

2 /

to minority group students (App. 197-98a). And finally the

statistics showed there was a much higher percentage of blacks

and Puerto Ricans in acting supervisory positions, where ability

to perform is the sole criterion of selection, than in licensed

positions (19% of acting principals as against 1% of licensed

principals). Plaintiffs also documented the culturally biased

nature of the examinations themselves, submitting expert evidence,

based on an analysis of the most important examinations given

_2y Thus Rochester has a black student population comparable to

New York's (30% as compared to 34%) but 11 times as many black principals.

3

by defendants in recent years, that they were likely to discrimi

nate unfairly against blacks and Puerto Ricans (App. 35-39a;

see also App. 149-50a).

Evidence was also introduced indicating that defendants'

supervisory examination procedures could not be justified as

job-related. Thus plaintiffs showed that defendants had never

performed a job analysis - concededly the first and essential step

in developing a job—related examination — for any supervisory

position. indeed the first step of the first job analysis plan

in the history of the New York School System had just been

undertaken in the form of a research proposal to discover the

qualities needed by an Elementary School Principal, the very

examination scheduled for November 3, 1970, which plaintiffs

. . . !/sought to enjoin. Plaintiffs also charged that the persons

responsible for developing and administering defendants'

examinations had no background or training in the testing field,

were selected on an ad hoc basis from the teaching and supervisory

ranks without having to satisfy any special qualifications or

selection procedures, or being provided any special training in

test construction and administration and, in addition, that they

were overwhelmingly of the white race. Finally plaintiffs showed

that no validity studies had ever been conducted indicating

-17 APP- Ex- 19; DuBois Affidavit, Ind. Doc. No. 44, paras.

7 and 8 . Documents not included in the Appendix or Appendix

Exhibit Volume will be referred to by their number on the Index to the Record on Appeal.

4

that defendants' examinations were in any way related to job

_4J

performance.

Plaintiffs also submitted evidence that authorities responsible

for selecting supervisory personnel had found no correlation between

possession of a license and ability to perform the job at issue,

that many licensed candidates had been found unqualified to serve

in the position for which they were licensed, and that in order to

select the most qualified candidates it had often been necessary to

appoint persons without the requisite licenses on an acting basis

(App. ll-34a).

After obtaining numerous extensions of time defendants finally

filed reply papers October 27, 1970, one week prior to the

scheduled November 3 Elementary School Principals' Examination.

On the basis of oral argument October 27 and 29, the court

decided it had not had sufficient opportunity to consider the

merits of the case before it and therefore refused to enjoin

the administration of the November 3 and other future examinations.

However, to maintain the status quo pending consideration of

plaintiffs' motion, the court granted a temporary restraining

order preventing the promulgation of new eligibility lists based

on such examinations (App. 101a).

4/ App. 15a, 12a, 28-29a, 150a, 37-39a. See generally Note, Dis

criminatory Merit System: A Case Study of the Supervisory Examinations

Administered by the New York Board of Examiners, 6 Colum. J. Law and

Social Problems 374, 377-88 (1970), Exhibit 13 to DuBois Affidavit,

Ind. Doc. No. 44.

5

The Board of Education took the position at this time that

the complaint raised issues of fact which should be determined at

trial, and that it would leave to the Board of Examiners the task

of defending their examination procedures (App. 99-100a). The City

School System's chief administrator, Chancellor Scribner, had

previously indicated that he would "prefer not to defend" against

the action since "[t]o do so would require that I both violate

my own professional beliefs and defend a system of personnel

selection and promotion which I no longer believe to be workable,"

a system inconsistent with the selection of "the most talented

supervisors; the most able principals and other administrators who

possess the highest level of leadership qualities possible. . . . "

(App. Ex. 18, p. 4). Neither the Board of Education nor the

Chancellor has actively participated in the defense of this action

to date.

The Examiners argued in their reply papers that plaintiffs

had not made out a case of discriminatory impact because they

had not submitted "the only meaningful statistic" — to-wit,

"̂ .comparison of the pass-fail ratio of black and Puerto Rican

applicants." They argued further that

"[i]f such an evaluation were undertaken,

it would demonstrate clearly that eligible

black or Puerto Rican applicants have per

formed comparably with white applicants on examinations." 5 /

_5_/ (Affidavit of defendant Examiner Jay E. Greene App. 87-88a)

(emphasis added). in addition, Mr. Greene cited a few examples of

a few examinations in which "It is believed that" blacks and Puerto

Ricans performed comparable with whites (App. 88-90a).

6

The Examiners defended the validity of their examinations

at this time on the basis of a number of alleged research and

validity studies which they did not submit. Thus defendant

Examiner Rockowitz claimed there were numerous research studies

which were designed "to determine the validity" and which "confirmed

the validity" of the examinations (App. 63a); that there had been

at least three "empirical validity" studies, and that their

results "indicate substantial positive correlations between the

purposes of the examinations involved and the results obtained. . .

(ftPP• Ex. 10, pp. 3—4) (emphasis added). Specifically, he relied

on the results of an alleged predictive validity study of

elementary school principals' examinations as showing that

principals identified as the best performers on the job "score

higher on the . . . examinations than do a random selected group

of principals" (App. Ex. 10, p. 4). And finally he alleged that

the Examiners had conducted 22 "validity studies" and had

published three volumes relating to research (App. Ex. 10, p. 5).

The Examiners also relied on the opinions of four experts whose

opinions were based on statements made to them by Board representa

tives describing examination procedures and on the research

studies cited by Dr. Rockowitz, together with other documents

submitted to them. These experts claimed only that on the basis

of what they had seen and been told the Board appeared to have

made certain efforts to design content-valid examinations.

term

_6_/ The/predictive validity, used by the court below, is some

times referred to as "empirical" or "criterion related" validity.

A brief discussion of the meaning of predictive and content validity,

and significance in showing job-relatedness, appears atpp • Orr j o ; m r r a .

- 7 -

1

In response plaintiffs submitted extensive additional

evidence that defendants' examinations could not be shown

to be job-related. Recognized experts, including Dr. Enneis,

staff psychologist in the Office of Research of the U. S.

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, concluded

that the documents entitled "Duties of the Position," which

were the only job descriptions used by the Examiners in con

structing examinations, did not constitute job analyses and

were an inadequate basis for developing a job-related selection

system (App. 108-09a, 117a). They also concluded that the

Examiners' experts had not conducted the kind of analysis and

investigation essential to support a claim of content validity

(App. 112-114a); and that in any event predictive validity

studies were both feasible and, indeed, were essential to

establish job-relatedness for the type of examinations administered

by defendants (App. lll-12a, 114a, 116a). Plaintiffs intro

duced additional evidence documenting previous charges that no

job analysis had ever been conducted, and that the assistant

examiners who designed and administered examinations had no

special background or training (App. 129a, 131-32a, App. Ex.

14) .

At a hearing November 19, 1970, the court indicated that

comparative statistics as to actual pass rates of different

ethnic groups were essential to assess the discriminatory impact

of defendants' examinations. Since plaintiffs had no access

to such information and since defendants claimed they had no

8

racial records, the court ordered the parties to develop a

survey procedure to determine comparative pass rates on a

significant sample of examinations.

Plaintiffs asked that defendants be ordered to produce

statistics on the pool of eligibles, as well as on applicants,

so as to document the charge that defendants' discriminatory

examination system had a chilling effect, discouraging blacks

and Puerto Ricans from even applying. Defendants had claimed

that no such statistics were available, and the court refused

to order them produced on the grounds that the essential issue

in determining discriminatory impact was the effect of the

examinations upon actual applicants (Ind. Doc. No. 25, TR 10-13, 16).

Elaborate survey procedures were worked out by the parties

and the court and incorporated in four different court orders.

The survey covered the most important supervisory examinations

given in the past seven years and all supervisory examinations

given in the past three years. Over 6000 applicants were in

volved. The survey was conducted by the Board of Examiners and

the Board of Education with the assistance of the National Opinion

Research Center, and took several months to complete. Following

the submission by both sides of expert affidavits (Ind. Doc. Nos.

61-63, 66) and briefs (Ind. Doc. Nos. 60, 64) directed to the

relevance of the statistical tabulations, an evidentiary hearing

was held May 21, 1971 (Ind. Doc. No. 26), to clarify apparent

conflict between the parties' experts. At this hearing plaintiffs

presented essentially uncontradicted expert evidence that the

7/ App. 189a, 231a n. 14; Ind. Doc. Nos. 11, 15, 23.

9

statistics revealed that defendants' examinations had a significant

and substantial discriminatory impact upon blacks and Puerto Ricans.

At the conclusion of the hearing the court afforded both

sides an opportunity to provide further evidence by affidavit

or oral proof respecting the issue of job-relatedness (TR 110,

Ind. Doc. No. 26).

Plaintiffs submitted all the Examiners' alleged research

and validity studies which were obtained upon court order pursuant

to a discovery request, Ind. Doc. No. 17. Plaintiffs also submitted

an extensive expert analysis of these studies in the form of an

affidavit submitted by Dr. Richard Barrett (App. 155-64a, App.

Ex. No. 15), a recognized authority on employment testing and

discrimination (App. 35-36a). Dr. Barrett stated that he had

examined all the alleged research and validity studies relied

upon by Dr. Rockowitz in his original affidavit for his claim

that the examinations were job-related. Dr. Barrett concluded

that no study supported a claim of predictive validity and no

study related to a claim of content validity. He stated further

that the only study even relating to validity, entitled Analysis

of Examination for Principal of Elementary Schools (Exhibit 1 to

Barrett Affidavit, Ind. Doc. No. 68), indicated that there was in

fact no relationship between the examinations in question and

job performance (App. 159-61a). The remaining research studies

consisted solely of studies dealing with the internal structure

of tests, the research proposal for the development of a job

analysis for the Elementary School Principal position referred

10

to supra, p. 4, descriptions of teacher selection procedures

in various school systems in the United States, and a report on

a conference held by the Board of Examiners, also involving

_SJteacher selection procedures (App. 161-62a).

In addition, Dr. Barrett stated that he had examined all

the documents relied on by the Examiners' four testing experts

as the basis for their opinions concerning the Examiners' pro-

cedures. Dr. Barrett concluded that mere examination of these

documents could not support a claim for content validity (App.

l62-63a), and that such a claim could be justified only by the

kind of study which it was clear from their affidavits the

Examiners' experts did not conduct — that is, a thorough

analysis of the various supervisory jobs at issue, establishment

of success criteria and determination of whether the tests at

issue adequately represented the most important aspects of the

related jobs (App. 157-58a) (see also 112-14a). Indeed Dr.

Barrett noted that the Examiners' experts had not even claimed

that the examinations were in fact content valid but only that

it -appeared that the Examiners attempted to design content valid

examinations (App. 157a).

8 / Each of these documents are described in the appendix to

Dr. Barrett's affidavit which appears at App. Ex. 15. The

documents themselves were filed as Exhibits 2-8 to Barrett

affidavit, Ind. Doc. No. 68.

9_/ (App. 158a) (See supra p. 7 ). These documents were also

filed as Exhibits to the Barrett affidavit , Ind. Doc. No. 68.

In response the Examiners, who had previously declined

the court s offer of an opportunity to submit additional evidence

by affidavit or oral testimony (Ind. Doc. No. 26, TR 105, 109, 110),

chose to submit only another affidavit from defendant Examiner

Rockowitz which added nothing to his previous claims (App. 165-77a).

(2) The District Court's Decision

On the basis of a voluminous record, briefly summarized 10/

above, Judge Walter R. Mansfield, who had presided over every

aspect of the case from its initiation, issued his opinion July 14,

1971 (App. 179-235a), finding that the Board's examinations had the

"effect of discriminating significantly and substantially against

qualified black and Puerto Rican applicants." (App. 201a; see also

190-91a, 221a).

The court's analysis of the comparative pass rates revealed

by the court-ordered examination Survey was based on the affidavits

submitted by statisticians for both sides and the evidentiary

11/hearing held May 21, 1971 (App. 190-201a). The court found that

analysis of the aggregate data for the entire series of examinations

showed whites passing at almost one and one—half times the rate of

blacks and Puerto Ricans (App. 190a, 194-96a). The court noted

fur"ther that whites had passed the examination for Assistant Principal,

_10/ The court noted that in reaching its decision it had had the

benefit of "a plethora of lengthy affidavits and exhibits, a hearing

at.which oral testimony was taken, a series of arguments, and extensive

briefing of the law and facts by the parties," as well as briefs bythree amicus parties (App. 183a).

11/ To the extent that the parties' statisticians differed, the court

noted that it was more persuaded by the testimony of plaintiffs'

statistician after "reviewing their testimony and appraising them as witnesses" (App. 194a).

12

Junior High School at almost double the rate of blacks and

Puerto Ricans and had passed the examination for Assistant

Principal, Day Elementary School at a rate one-third greater than

blacks and Puerto Ricans, and that these examinations were of

particular significance both because of their size and "because

the assistant principalship has traditionally been the route to and

prerequisite for the most important supervisory position, Principal"

12/(App. 191-92a). Finally, the court concluded, on the basis of

the expert evidence, that the fact that whites passed at a higher

rate than blacks and Puerto Ricans in 25 of the 32 examinations

subject to comparison, was proof of the discriminatory impact

13/

of the entire series (App. 193-94a).

However, the court did not rely solely on the statistical

disparities revealed by the Survey since it was clear from the

evidence that they represented a gross underestimate of the dis

criminatory impact of defendants' supervisory examination system.

12/ The court noted that of the 50 examinations covered by the

survey some were taken by very few people and because of the smallness

of the samples the results of each, analyzed individually, could not

be accorded much significance. Thus 41 of the 50 examinations were

taken by only 83 (or 10.1%) of the total number of black and Puerto

Rican candidates (App. 196-97a). On all nine examinations taken by

10 or more black and Puerto Rican candidates, whites passed at a

substantially higher rate (App. 197a).

13/ The results of Dr. Cohen's statistical analysis are summarized

at App. Ex. 26.

It is worth noting that there was no significant conflict

between the two statisticians at the evidentiary hearing below.

Dr. Jaspen, the Examiners' statistician, conceded that Dr. Cohen's

analysis of the aggregate data was correct (Ind. Doc. No. 26,

TR 66-67); that it was proper to subject the aggregate data to

13

Thus the court found that:

"The fact that the process involves a series

of examinations and that to reach the top

one must pass several examinations at different

times in his or her career serves to magnify

the statistical differences between the white

and non-white pass-fail rates." (App. 192a)

Thus, for example, if any given examination screened blacks and

Puerto Ricans out at approximately twice the rate of whites, two

successive examinations would screen them out at four times the

rate of whites (App. 192-93a).

On the issue of whether examinations with such an impact could

be justified the court held:

"The Constitution does not require that minority

group candidates be licensed as supervisors in

the same proportion as white candidates. The

goal of the examination procedures should be to

provide the best qualified supervisors, regard

less of their race, and if the examinations appear

reasonably constructive to measure knowledge,

skills and abilities essential to a particular

position, they should not be nullified because

of a de facto discriminatory impact."

[Emphasis added] (App. 201a)

The court concluded, however, that the Examiners' procedures could

not be justified as being reasonably related to job performance.

On the basis of extensive evidence and exhaustive briefs discussing

the law and authorities on employment testing,the court found that

for a test to be considered job-related on the basis of its

13/ (Continued)

analysis to determine the overall impact of the supervisory

examinations on candidates (id. at TR 68-6 9) ; and that it was

proper to compare the number of examinations whites passed at a

higher rate with the number of examinations blacks and Puerto

Ricans passed at a higher rate, by the "binomial" or "sign" test,

in assessing the impact of the series of examinations (id. at

TR 69-71) (apart from the problem of overlap discussed Toy the court

at App. 195-96a).

14

“.£2nt.?nt validity," it was essential to first perform an

adequate job analysis:

"Such an analysis requires a study to be made

of the duties of the job, of the performance

by those already occupying it, and of the

elements, aspects and characteristics that

make for successful performance. Questions

are then formulated, selective procedures

established, and criteria prepared for

examiners that should elicit information

enabling them to measure these characteristics,

skills and proficiency in a candidate and

determine his capacity to do the job satisfactorily. (App. 206a)

The court noted that the Examiners' own expert, Dr. Thorndike,

had stated that "predictive validity,'1 which depends upon a

showing of a correlation between test scores and job performance,

was "most desirable. . . . to show that the test is in fact

effective in discriminating between those who are and those who

are not successful in a particular job," and that anything

short of that must be recognized as a "stop-gap" (App. 206a).

Although plaintiffs had contended that the Board's examinations

could not be considered job-related without a showing of

p redictive; validity, the court did not have to reach this issue.

It found that even accepting the Examiners' position that use

of procedures designed to ensure content validity was sufficient

(App. 212-13a), the Board had not "achieved the goals of con

structing examination procedures that are truly job-related"

since:

Despite its professed aims the Board has not

m practice taken sufficient steps to insure

that its examinations will be valid as to

content, much less to predictiveness."

(App. 213a)

15

claim that they relied on outside experts and lay persons in

determining success criteria was not supported by the evidence

(App. 213-14a), that the Chancellor had found the examinations a

barrier to selection of the most qualified supervisors (App. 214-15a),

and that the Examiners' position was not supported by the research

reports they had relied on ". . .as demonstrating the content

validity of . . . supervisory examinations." (App. 215-16a).

The court found that the only report even relating to validity was

a pilot predictive validity study which "showed that there was

little or no correlation between success on the tests and job

success." (App. 216a). The court concluded that the Board had

failed to achieve the goal of content validity, noting that this

conclusion, "which is based upon our appraisal of affidavits of

experts furnished by the parties, is confirmed by our own study

14/

of some of the examinations. . . . "

The court concluded that preliminary relief should be

granted since there was "a strong likelihood that plaintiffs

will prevail on the merits at trial,""the balance of hardships

tips decidedly in favor of plaintiffs, and, pending final determi

nation of the merits, the effect of preliminary relief would be

to preserve the status quo until the issues are resolved," and

preliminary relief would not harm the public (App. 223-25a).

In support of this finding the court noted that the Examiners'

14/ App. 217a. The court noted that defendants' examinations

typically contained both short-answer, multiple-choice tests and

essay tests, both of which appeared "aimed at testing the candidate's

ability to memorize rather than the qualities normally associated

with a school administrator" (App. 217a), and that a leading

training manual for such examinations emphasized the use of mnemonic

devices (App. 217-19a). See 232-25a, n. 23-24 for examples.

16

(3) The Preliminary Injunction

At defendants’ request and over plaintiffs’ vigorous

objection, the court delayed entry of the preliminary injunction

because counsel for defendants had alleged they were unable to

consult with their clients during the summer.^

The Examiners took advantage of this time to develop

partial statistics and prepare new affidavits relating to the

November 3, 1970 Elementary School Principals' Examination and

xn September, 1971, urged the court to consider this new evi

dence and to permit licenses to be issued and regular appoint

ments made on the basis of that examination. Despite the fact

that the motion for a preliminary injunction and the court's

July 14 opinion were focused largely on that very examination, and

the record was closed, the court nonetheless carefully considered

the Examiners' papers, rejecting their relevance for reasons

set out in detail in the memorandum opinion supporting its

preliminary injunction (Ag£. 251-55a). After considering a

variety of proposed injunctive orders submitted by the parties,

together with supporting affidavits, memoranda and other papers,

the court entered its preliminary injunction on September 20,

1971 (A££. 2 57-59a), one year after suit was filed, incorporating

certain of plaintiffs' suggestions, but permitting any party to

apply for a modification of the order to permit the institution

of new examination procedures (App. 259a).

.15/ The court meanwhile entered an interim inj

defendants from conducting further examinations

eligibility lists, and using outstanding lists

appointments (App. 237a).

unction restraining

, publishing new

to make permanent

17

(4) Subsequent Developments

At the time the court entered its injunction the Chancellor

had submitted a resolution proposing the institution of an

interim system for the selection of acting supervisors to

operate pending final determination of the instant action

(App. Ex. 27), which the court below noted as bolstering its

previous determination that the relief endorsed would in no

way harm the public or the administration of New York City

schools (App. 255a). A slightly modified version of this pro

posal was adopted by the Board of Education on October 6, 1971,

and is presently being implemented. It contains provisions

for the development of "written procedures governing the

selection and assignment of acting supervisory personnel,"

"the description . . . of clear performance objectives for the

position to be filled," the development of "performance criteria,"

the "periodic evaluation of on-the-job performance of acting

supervisory personnel," and an "Advisory Council on the

Selection of Acting Supervisory Personnel" to ensure that

aPpointments are made in consonance with merit and fitness.

The resolution also established new eligibility requirements

for acting supervisory positions. 16/

On November 9, 1971, the Examiners submitted to plaintiffs

a proposal for a new supervisory examination system (attached

hereto as App. A, pp. 2-13a infra). This proposal was sub

mitted as the basis for an application to the court for modi

fication of the preliminary injunction (pp. l-2a, infra).

15/ A * •Acting supervisors must meet eligibility requirements for

2 ; ro ^ a ? r ; ? ^ p^ - j r rvisory exa” ination -

18

Designed to improve the "compatibility" of the examinations

with a decentralized system (p. 3a, infra), this proposal

makes clear in describing the steps that would be taken in

developing job analyses, job-related examinations and

validation procedures that previous procedures were inadequate

to ensure job-relatedness. Thus for example, the proposal

states that the Board will obtain

" . . . in addition to statements of duties of

the position, appropriate skills, qualities and

behaviors, in other words, specific job analyses

for each position for which it is required to con

duct examinations." (p. 4a, infra)

The proposal describes the manner in which job related examinations

will be developed, noting that

"[t]he language mastery element in written tests

will be deemphasized to take its place alongside

such data as are obtained through other tests

which reveal essential elements of administrative

ability, supervisory ability, attitude toward the

learning process for the varying student popu

lations of the city, human relations skills as

the candidate may offer, e.g., knowledge of spoken

Spanish, knowledge of Afro-American and Hispanic

culture, etc." (p. 5a, infra)

The proposal suggests that instead of eliminating candidates

by rigid cut-off scores, as in the past, the Examiners would

instead provide an "assessment profile" for each candidate,

thus enabling such community school board to evaluate the

various candidates in the light of its own particular needs;

only those candidates who could not satisfy a level of mini

mum competence would be disqualified by the Board's examinations

(pp. 6-8a, infra). Finally, the proposal provides for the

predictive validation of the new examination system (pp.ll-12a,

infra).

19

Subsequently, the Educational Testing Service of Princeton,

New Jersey (E.T.S.), submitted to plaintiffs and the Examiners

a draft proposal for the development by E.T.S. of a truly non-

discriminatory and job-related examination system. This pro

posal (attached hereto as App. B, pp. 14-24a,infra) reveals

beyond any doubt that the Examiners' previous procedures were

wholly inconsistent with professional test development standards

and incapable of producing job-related examinations. The pro

posal also makes clear that a job-related examination system

can be developed, describing in some detail the steps that

should be taken to develop job analyses, success criteria, and

test specifications. Finally, the E.T.S. proposal shows that

empirical validation, which rests on a demonstrated correlation

between test scores and job performance, is not only feasible

but accepted by professionals in test technology as a neces

sary preliminary to use of an examination (pp. 19a, 22-23a,

infra). It is also significant that E.T.S. starts with the

assumption that a job-related and non-discriminatory examination

would not reject members of different ethnic groups out of

proportion to their numbers in the applicant group (p. 16a,

infra).

20

ARGUMENT

Introduction

In reviewing the decision below it is important to realize

that the trial judge who presided over every phase of the case

during the entire 12 months of proceedings, acted on the basis

of an exhaustive factual record, which included literally

dozens of affidavits, hundreds of pages of exhibits, and an

evidentiary hearing. The court also relied upon numerous

briefs, submitted at various stages of the case by the parties

and three amici curiae, and several oral arguments. Through

out the proceedings the court proceeded with extreme caution,

providing only such interim relief as seemed essential, and

refusing to make any assumptions as to the discriminatory

impact of defendants’ examination system in the absence of a

comprehensive summary of examination results. At every stage

the court offered the parties full opportunity to present

evidence and argument. While the Examiners now object to

certain of the court's factual conclusions they could not

and did not object at any time that the court prevented them

from presenting their case in whatever form they chose.

It is also important to realize the context in which the

legal issues involved in this case appear. There has been

increasing recognition in recent years that New York City's

schools are in a state of crisis, that ghetto schools in par

ticular are failing to educate their students, and that black

21

and Puerto Rican children not only do badly as compared to

whites but do worse the longer they stay in these schools.-^

It is in large part out of this recognition that the movement

for decentralization grew, in the hope that schools would

thereby become more responsive to the needs of their com

munities and more able to serve their particular student

bodies. It is particularly ironic in this context that

defendants should maintain an examination system which is

not job-related and which in no way accounts for the fact

that different qualifications might be required for positions

in different schools and communities - a system which locks

out of the supervisory ranks many persons who are particularly

qualified to serve the students in the ghetto schools which

are at present failing their educational task.-̂ "^

17/ „See Note, supra n. 4, at 387-88 and n. 115; Council of

Supervisory Associations v. Board of Education, 23 N.Y.2d 458,

463, 297 N.Y.S.2d 547, 551, 245 N.E.2d 204, 207 (1969).

18/ Two recent cases have upheld administrative decisions to

by-pass normal civil service lists for school supervisory

positions, largely in recognition of the fact that traditional

civil service procedures have failed to select the very people

most needed to relate to ghetto communities and thereby serve

the schools which are most in need of improvement. In Council

of Supervisory Associations v. Board of Education, 23 N.Y.2d

458, 297 N.Y.S.2d 547, 245 N.E.2d 204 (1969), the New York

Court of Appeals upheld the Board of Education's decision to

create the new position of Demonstration Elementary School

Principal, and to make acting appointments to said position

pending development of a relevant examination, thereby by

passing the Examiners' Elementary School Principal list.

The court's decision was premised in part on its recognition,

in light of New York's educational crisis, of the importance

of selecting principals who could relate to their communities

and its finding that the traditional examination system had

failed to select such principals. See also Porcelli v. Titus,

302 F. Supp. 726 (D. N.J. 1969), aff'd 431 F. 2d 1254 (3d Cir.. 1970). -----

22

The evidence below revealed the gross disparity between

the numbers of blacks and Puerto Ricans on the supervisory

staff and in the student body (Ap£. 187-88a). Thus blacks

and Puerto Ricans constituted over half of the student body

but only one per cent of the principals. Whatever factors

may have contributed to this in the past it is clear that, with

decentralization and with revised eligibility requirements,

the Examiners' procedures had become the ma]or barrier to the

employment of minority supervisors.— ^ The evidence below

12/ Even if the examinations themselves did not disqualify

blacks and Puerto Ricans at such significantly disproportionate

rates, they would nonetheless, given the exclusionary effect

of the system as a whole, constitute unconstitutional barriers

to defendants' affirmative obligation to license and appoint

qualified black and Puerto Rican supervisors. The Survey

illustrated the manner in which defendants' system operated

as a whole to effectively prevent the appointment of any sig

nificant numbers of blacks and Puerto Ricans to the super

visory ranks, because of the combination of such factors as

low pass rates, eligibility requirements and exhaustion of

lists. See Plaintiffs' Memorandum on Relevance of Statistical

Tabulations, Ind. Doc. No. 60, pp. 10-12. A system of selection

which operates to perpetuate the gross underrepresentation of

blacks and Puerto Ricans on that staff and to prevent the

appointment of blacks and Puerto Ricans who might be qualified,

violates the Equal Protection Clause of the Federal Constitution.

See generally Porcelli v. Titus. 431 F.2d 1254, 1257-58 (3d

Cxr. 1970), affirming 302 F. Supp. 726 (D. N.J. 1969), holding

that where there was a gross disparity between the percen

tage of blacks in the student population and their percen

tage on the supervisory staff, the school board had an affir

mative obligation under the Federal Constitution to correct

that disparity. See also Jackson v. Wheatley School District.

430 F.2d 1359, 63 (8th Cir. 1970); Armstead v. Starkville

Municipal Separate School District. 325 F. Supp. 560, 569

(N.D. Miss. 1971), where the courts found disparities between

the percentage of black students and the percentage of black

faculty members evidence of racial discrimination. In North

Carolina Board of Education v. Swann, 402 U.S. 43 (1971), the

Supreme Court made it clear that any law, regulation or of

ficial policy which prevented boards of education from taking

23

further revealed that the Examiners' procedures were blocking

the appointment of minority and other candidates not on the

basis of "merit and fitness" but, rather, on the basis of

their inability to answer such questions as "[W]ho killed

Cock Robin?" (App. 232a, n. 23).

The Board's procedures have for decades been subjected

to severe criticism by every body which has investigated it

because, far from fulfilling their purported goal of selecting

the best qualified supervisors, they were in fact locking such

persons out and perpetuating a sterile, bureaucratic, insider

system.20/ But despite this criticism and series of recom

mendations for reform, no significant change in the Board's

procedures took place. It is only as a result of the decision

19/ (Cont'd)

affirmative action to correct the kind of gross racial under

representation exhibited in the instant case must be declared

unconstitutional. See generally Fiss, A Theory of Fair Employ

ment Laws, 38 U. CHI. L. REV. 235, 270 n. 42 (1971).

20/ See Mayor's Committee on Management Survey, Administrative

Management of the School System of New York City (1951) (the

"Strayer and Yavner Report"); Schinnerer, A Report to the New

York City Education Department (New York, 1961); Cresap,

McCormick and Paget, Summary Report of Assignments Conducted

for the New York City Board of Education (1962); GRIFFITH REPORT,

TEACHER MOBILITY IN NEW YORK CITY: A STUDY OF RECRUITMENT,

SELECTION, APPOINTMENT, AND PROMOTION OF TEACHERS IN THE NEW

YORK CITY PUBLIC SCHOOLS 162-230 (1963); Center for Field

Research and School Services, New York University, A Report

of Recommendations in the Recruitment, Selection, Appointment

and Promotion of Teachers in the New York City Public Schools

(1966); BUNDY REPORT, MAYOR'S ADVISORY PANEL ON DECENTRALI

ZATION OF THE NEW YORK CITY SCHOOLS, RECONNECTION FOR LEARNING

110, n. 28 (1967); Rogers, 110 LIVINGSTON STREET 285-97 (1968).

In addition, Boards of Education have, in recent years, urged

the legislature to abolish the Board of Examiners. And most

recently the New York City Commission on Human Rights issued a

24

of the court below that there now appears to be some hope for

the development of a selection system which will truly allow

for the appointment of those supervisors best qualified to

serve the schools and children of this City (see pp. 18-20, supra).

POINT I

THE DISTRICT COURT'S FINDING THAT

DEFENDANTS' EXAMINATION SYSTEM HAD

A SIGNIFICANT AND SUBSTANTIAL DIS

CRIMINATORY IMPACT WAS CLEARLY

SUPPORTED BY THE RECORD

Throughout their brief the Examiners claim that the court

below based its decision on statistical rather than legal

analysis, and found a prima facie case of discrimination made

out on the basis of findings of mere "statistical significance"

and departures from "perfect equality" in the treatment of

20/ (Cont'd)

thorough report on the schools' selection system, based on

public hearings held Jan. 25-29, 1971 and extensive documen

tation, recommending that the Board of Examiners be dis

continued on the grounds that its present examination system

locked out qualified minority and other candidates, and was

apparently not job-related. The Commission recommended further

that New York City rely on state certification for initial

screening (as does virtually every city school district in

the country) and on community school boards for actual

selection based on "criteria and procedures geared to the

need of individual boards." Equal Employment Opportunity and

the New York City Public Schools, An Analysis and Recommen

dations Based on Public Hearings Held January 25-29, 1971 by

the City Commission on Human Rights, (pp. xv-xvi). The Com

mission specifically found that the lists of job duties used

to prepare examinations were "inadequate bases for sound

test construction" (p. xx) and that the Board of Examiners’

resources were inadequate to the task of designing and adminis

tering tests and assessing their validity (p. xxi).

25

members of different ethnic groups. (See Brief pp. 10, 15-17,

21-24) This is simply not true. The court's decision was

clearly based not on a test of mere statistical significance

but, rather, on findings that defendants' examinations had a

significant and substantial discriminatory impact, resulting

in "gross" differences in the treatment of different ethnic

groups (App. 201a, 191a, 221a; see also 190a).

The court's finding of discriminatory impact was based

essentially on two factors. The court relied first on the

results of the survey, which showed that the entire series

of examinations had a significant and substantial discrimi

natory impact on black and Puerto Rican applicants and also

showed gross disparities in pass rates on the biggest and

most important examinations (pp. 12-13, supra; App. 189-94a*

App. Ex. 26). But secondly, the court concluded that the

disparities revealed by the survey constituted a gross under

estimate of the discriminatory impact of the examination

system because, as the evidence revealed and the court found,

during the period covered by the survey the promotional process

involved a series of examinations and "to reach the top one

must pass several examinations" (App. 192a). The court found

21/ Indeed, the reason the court apparently felt called upon

to discuss the statistical analysis of the data in such detail

is because the Examiners had rested their case largely on an

attempt to attack the statistical significance of the survey

results. See Dr. Jaspen's affidavit, Ind. Doc. No. 66 and

May 21 hearing TR, Ind. Doc. No. 26.

26

that the net effect of this system was to screen minority

candidates out at rates far in excess of those indicated by

the survey results (App. 192-93a). ii/

22/

The Examiners miss the point in their brief (pp. 18-19)

since they assume erroneously that the example the court gives

to illustrate the manner in which this multiplier effect

worked was intended as some kind of factual future prediction.

The Examiners introduce in their brief at p. 19 partial

and misleading pass-fail data on the results of the November

1970 Elementary School Principals' Examination. These data,

produced after the court's decision, when plaintiffs had no*

opportunity to present evidence, were rejected below in the

court s memorandum opinion supporting the preliminary injunction

(Ap£. 251-55a), on the grounds that they were too incomplete

to be meaningful (covering only 60% of the candidates), that

they revealed that the pass rates for the identified candidates

could not be assumed to be typical of the pass rates for those

not identified, that plaintiffs had had no opportunity for

cross-examination, and that plaintiffs were entitled to

discovery to determine all relevant facts relating to this examination (App. 253-54a).

The fact that the Board of Education has recently re

vised certain eligibility requirements is irrelevant since

during the period of the survey the previous requirements

were in effect. Moreover, despite the revisions most candi

dates must still pass through a succession of tests starting

with the teacher's examination. Finally and most important,

to the extent that the Board of Education does reduce the

number of examinations through which candidates must pass as

they climb the promotional ladder, it is likely that the dis

criminatory impact of each particular examination (assuming

that their nature remains unchanged) will increase. This is

because candidates who have survived screening by prior tests

are relatively homogeneous in test-taking ability and un

screened groups are likely to show greater differences between

different ethnic groups (Dr. Cohen's affidavit, ver. 5/6/71,Ind. Doc. No. 62, para. 7).

It is worth noting in this connection that the survey

results grossly underestimate the discriminatory impact of

defendants examination system in an even more significant

way, not taken into account by the court below. Virtually

all candidates covered by the survey had been pre-screened

27

In addition, the court relied on the fact that cities

which did not use an examination system like New York1s had much

higher percentages of blacks and Puerto Ricans on their super

visory staffs (App. 197-98a; 222a; see also p. 3. supra)

The Examiners also quarrel with the court's analysis of

the survey results in numerous respects. In considering their

arguments it is important to realize that the survey procedure

was developed by the parties and the court as the best method

of assessing the impact of defendants' examinations; that the

parties' statisticians differed on no significant issues (see

n. 13 , supra); that defendants had ample opportunity to present

any evidence they considered relevant below; and that the

court made its findings on the basis of exhaustive evidence

and briefing.

22/ (Cont'd)

by the Board's teacher examinations and it is likely that it

was at this stage, where the applicant group was unscreened

by any previous test, that the discriminatory impact was

greatest. what is extraordinary is that the Board has managed

to design examinations which discriminate even against blacks

and Puerto Ricans who have proven themselves to be good test

t.c l.K 6 ITS •

23/

, fvTh! Examiners claim that these disparities are explained

bT th^-faCt that New York city's education and experience eligibiiity requirements were higher than those in "many other cities (Brief pp. 20-21), but there is no evidence in the

record that this is true with respect to any specific city named by the court. J

28

The Examiners contend now, for the first time, that the

comparative pass rates revealed by the survey are irrelevant,

on the grounds that the minority applicant group allegedly

constitutes a disproportionately large percentage of the pool

of eligibles and is allegedly less qualified than the white

applicant group (Brief pp. 11-15). This argument depends on

a number of wholly unsupported and unwarranted assumptions:

first, that the teacher population approximates the pool of

eligibles; second, that the ethnic groups within this popu

lation are equivalent in ability; and third, that among those

®^icfihle it is the most qualified who apply for promotional

examinations.

Presentation of this issue now is, however, untimely

since it was not raised below where there would have been

ample opportunity to develop and present relevant evidence.

Instead the Examiners insisted below, and the court conceded,

that the best evidence of the examinations' discriminatory

impact would be comparative pass rates of actual applicants.

(PP-4, 9, supra) Thus the Examiners took the position below

that "the only meaningful statistic would be a comparison of

the pass-fail ratio of black and Puerto Rican applicants"

(ftPP- 88a). At no point in the proceedings below did they

indicate that these were not the most relevant data. Before

the survey their claim was that blacks and Puerto Ricans

passed at the same rate as whites. After the survey their

claim was that there was no significant difference in the

pass rates revealed. it is only now that the court below has

29

found that the differences are in fact significant and sub

stantial that the Examiners claim that the entire survey and

all the proceedings below related to it were an exercise in

futility because the focus should have been on the pool of

eligibles rather than the applicants. a e Examiners can_

not now attempt to justify the disparities in pass rates

revealed by the survey on the basis of assumptions - for

which there is no support in the record - that the minority

applicants were less qualified than the white applicants.^

Moreover, there is no reason to credit the Examiners'

unsupported assumptions that the minority applicants were less

qualified. First there is no reason to assume that the teacher

24/

bSl?W P o n t i f f s attempted to obtain statis-ics on the pool of eligibles defendants refused to provide them. See p. 9 , supra. ^

25/

*£deed below there was uncontradicted expert testimony

he analysis of the survey results was relevant "for the

population at issue, not merely the sample under study."

(Hearing May 21, Ind. Doc. No. 26, TR 13).

30

population approximates the pool of eligibles.^ Secondly

different ethnic groups in the teacher population are not

necessarily equally qualified. Since only highly motivated

minority persons are likely to try to break into a system

that has traditionally been closed to them, the minority group

may be particularly well-qualified. Finally, there is no

reason to assume that in this school system promotional

examinations will attract the most qualified candidates

from every ethnic group. The most talented teachers may well

decide to leave the school system after a few years. This

would likely be particularly true of whites who have more

opportunities open to them. The less talented and more

system-oriented whites, on the other hand, might well tend to

seek supervisory positions. Disproportionate numbers of highly

qualified blacks and Puerto Ricans might, however,

apply for promotional examinations because it is only in recent

26/

Substitute teaching and acting supervisory experience is

often an alternative to licensed experience and blacks and

Puerto Ricans represent a much larger percentage of substitute

teachers and acting supervisors. Similarly, experience as a

teacher anywhere in the United States under a valid license

satisfies the requirement of previous teaching experience.

And since the qualifications for each position are different,

there is simply no way of estimating the pool of eligibles

for the various examinations. See generally Exhibits 1-9 of

ver- 1-0/19/71. fid. DOC. No. 44. for examplesof qualifications. r

31

years that opportunities for appointment have begun to open

up and, therefore, that these examinations represent a real

opportunity for advancement. By contrast, the white applicant

group more likely includes large numbers of persons who were

previously and failed previous examinations.

While one could speculate endlessly as to the comparative

qualifications of the different ethnic applicant groups the

point is that the evidence below showed that the examinations

had a substantial discriminatory impact on black and Puerto

Rican applicants. The Examiners failed to provide any evi

dence justifying that impact, although they had ample oppor

tunity to document their hypothesis that the black and Puerto

Rican applicant group was less qualified than the white. in

the absence of evidence, such an hypothesis cannot be accepted

by this court, particularly since there is every reason to

believe that the black and Puerto Rican applicants constituted

a highly motivated and qualified group who persisted within a

system traditionally closed to them.

The Examiners' other objections to the court's analysis,

also raised here for the first time, are equally frivolous.

Thus they claim that the survey results cannot be used to

assess the discriminatory impact of defendants' examinations

in general, because examinations for different supervisory

positions were involved (Brief pp. 17-18). However, this

issue was-thoroughly explored at the evidentiary hearing

below and the court concluded, on the basis of testimony

by both statisticians, who evidenced no disagreement on this

32

issue, that valid conclusions as to the discriminatory nature

°f the examinations could be drawn even though discrete

examinations for different positions were involved. More

over the purpose of the survey designed by the parties and the

court was to assess the impact of the examinations as a whole ,

and the Examiners' only argument at that stage of the pro

ceedings was that fewer examinations should be included. The

Examiners also claim that the court erred in relying on com

parative pass rates for the entire group of applicants. They

contend that it should have considered as failing only those

who completed the entire examination process and not those

who failed because they withdrew at some earlier stage, either

before or after the written examination. But the court's use

of comparative pass rates was clearly reasonable and supported

by the expert evidence below. Moreover, both statisticians

testified that it made no difference whether the survey results

were analyzed by including or excluding the group of candidates

iZ/ See Hearing May 21, 1971, Ind. Doc. No. 26. Thus Dr. Cohentestified:

Q. Is analysis of aggregate test results relevant

to the sort of questions we have discussed when

there are different tests involved for different

kinds of supervisory positions and when the tests

involve different numbers of candidates?

A. Yes, they are quite adequate. (TR 9-10)

Q. Is it correct to use the binomial test where

you have a series of different examinations

for different positions?

A. Absolutely. . . . (TR 18)

See generally Dr. Cohen's testimony at TR 9-10, 13,14,18, 19-20,

22 and Dr. Jaspen's testimony at TR 68,70,71,81-82, 89.

In addition testimony by both statisticians completely ex

ploded the Examiners' argument below, repeated in its brief at

p. 17, that there was any relevance to the failure to find

statistically significant differences in pass rates in various

examinations with extremely small samples. See generally TR 22-32, 71-78.

33

who failed to complete the examination process.— '

POINT II

THE COURT BELOW CORRECTLY RULED THAT A PUBLIC

EMPLOYER VIOLATES THE EQUAL PROTECTION CLAUSE IN

CONDUCTING A PROMOTIONAL EXAMINATION SYSTEM WHICH

SYSTEMATICALLY AND SIGNIFICANTLY DISCRIMINATES

AGAINST ETHNIC MINORITY GROUPS WHERE THAT EXAMI

NATION SYSTEM CANNOT BE SHOWN TO HAVE ANY RELATION TO JOB PERFORMANCE

A ' A Prima Facie Case of Discrimination is Made Out

Where—Examinations Significantly and Systematically

Exclude Members of an Ethnic Minority Group

Regardless of Whether Any Subjective Intent to

Discriminate is ShownT

The E <aminers argue in their brief at pp. 21-26 that even

where there is evidence of grossly disparate treatment of racial

groups, additional evidence of purposeful discrimination is

essential to establish a claim under the Equal Protection Clause.

The danger of their argument, if accepted, is that it would

leave courts powerless to deal with the kinds of discrimination

problems that ethnic minorities will face increasingly as overt29/

forms of bias are outlawed. Moreover the interests of those

28/ see Hearing May 21, Ind. Doc. No. 26, TR pp. 10-11, 55. Thus

Dr. Jaspen, defendants' statistician, testified:

We analyzed this with pass versus fail plus did

not appear, plus withdrawn, and also just pass

versus fail, and we obtained completely consistent

results. . . . (TR 55)

.29/ Thus an Griggs v . Duke Power Co.. 420 F.2d 1225 (4th Cir. 1970),

rev_d, 401 U.S. 424 (1971), Judge Sobeloff noted in dissent:

The case presents the broad question of the use of

allegedly objective employment criteria resulting in the

denial to Negroes of jobs for which they are potentially

qualified. . . . On this issue hangs the vitality of

the employment provisions (Title VII) of the 1964 Civil

Rights Act: whether the Act shall remain a potent tool

for equalization of employment opportunity or shall be

reduced to mellifluous but hollow rhetoric.

34

discriminated against are essentially the same and deserve the

same degree of protection whether employment opportunities are

denied explicitly and intentionally or inadvertently. it is

for such reasons that this and other courts have made it clear that

where there is evidence of a racial impact or classification, no

30

evidence of an overt or covert intent to discriminate is necessary — ' * S

29/ (Continued)

The pattern of racial discrimination in employment

parallels that which we have witnessed in other areas.

Overt bias, when prohibited, has ofttimes been supplanted

by more cunning devices designed to impart the appearance

of neutrality, but to operate with the same invidious

effect as before. . . . (420 F.2d at 1237-38)

See also the Supreme Court’s opinion, 401 U.S. at 431.

S®e ' 2̂3.*' Norwalk CORE v. Norwalk Redevelopment Authority.

395 F.2d 920, 931 (2d Cir. 1968) (finding irrelevant the fact that

discriminatory effect of an urban renewal housing plan is "accidental "

since Equal Protection Clause prohibits thoughtlessness and not -just

governmental design to discriminate, citing Hobson v. Hansen, infra)-

T~,n.nedT^^vrk Homgs Ass’n- v. Lackawanna, 436 F.2d 108, 114 (2d Cir 1970) (holding with regard to the City's provision of facilities

that even if the discriminatory effect resulted from "thoughtlessness

rather than a purposeful scheme, the City may not escape responsibility

for placing its black citizens under a severe disadvantage which it

cannot justify"; Southern Alameda Spanish Speaking Org. v. Union

Ci^, 424 F . 2d 291, 295 (9th Cir. 1970) (if result of zoning bv

referendum is discriminatory a substantial Constitutional question

^presented without regard to racial motive); Hobson v. Hansen.

Ini p •,?"??: j01' 497‘ <D -D -C - 1967). aff'd sub nom Snmck v. Hobson.408 F.2d 175 (D.c. Cir. 1969) {". . . the arbitrary quality of

thoughtlessness can be as disastrous and unfair to private rights and

the public interest as the perversity of a willful scheme"; Hawkins

v^ Town of Shaw, 437 F.2d 1286, 1291-92 (5th Cir. 1971) (pendTHS----

decision after rehearing en banc) (finding a prima facie case of

discrimination made out on the basis of statistical disparities in

the provision of municipal services to different racial groups although

the record showed no "bad faith, ill will or . . . evil motive")-

Cgrmical v. Cravep,9th Cir. No. 26, 236, Nov. 4, 1971 (holding that

where test disqualified disproportionate number of veniremen

from jury service, the fact that the system was not designed with

discriminatory intent was irrelevant); Jackson v. Godwin, 400 F.2d

529 (5th Cir. 1968). Cf. Powell v. Power. 436 F.2d 84, 88 n. 7